1.4 AFRICAN AMERICAN ART AND ARTISTS

THE GREAT MIGRATION AND THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE

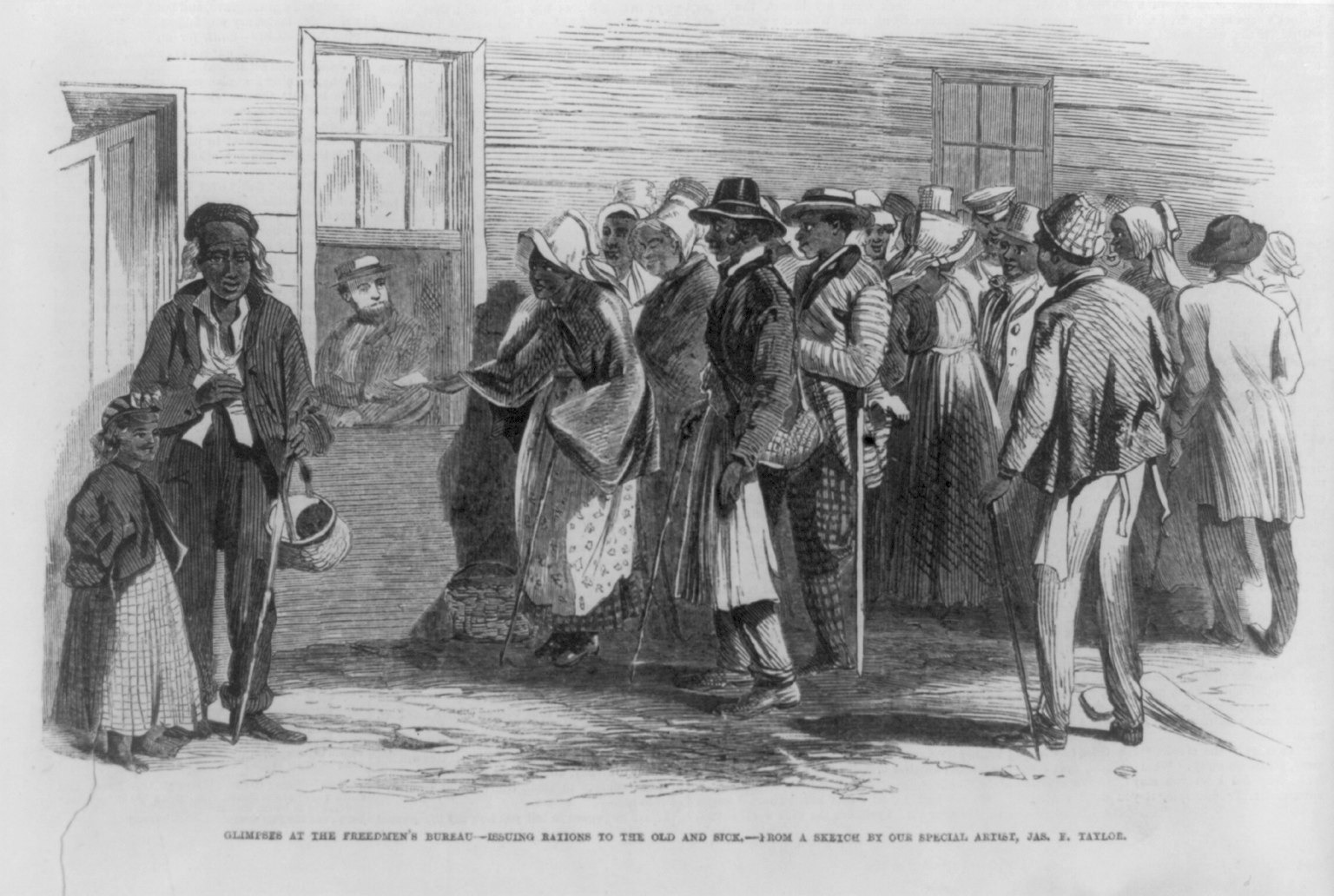

“For African Americans in the South, life after slavery was a world transformed. Gone were the brutalities and indignities of slave life, the whippings and sexual assaults, the selling and forcible relocation of family members, the denial of education, wages, legal marriage, homeownership, and more. African Americans celebrated their newfound freedom both privately and in public jubilees. But life in the years after slavery also proved to be difficult. Although slavery was over, the brutalities of white race prejudice persisted. After slavery, state governments across the South instituted laws known as Black Codes. These laws granted certain legal rights to blacks, including the right to marry, own property, and sue in court, but the Codes also made it illegal for blacks to serve on juries, testify against whites, or serve in state militias. The Black Codes also required black sharecroppers and tenant farmers to sign annual labor contracts with white landowners. If they refused they could be arrested and hired out for work.

Most southern black Americans, though free, lived in desperate rural poverty. Having been denied education and wages under slavery, ex-slaves were often forced by the necessity of their economic circumstances to rent land from former white slave owners. These sharecroppers paid rent on the land by giving a portion of their crop to the landowner. In a few places in the South, former slaves seized land from former slave owners in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. But federal troops quickly restored the land to the white landowners. A movement among Republicans in Congress to provide land to former slaves was unsuccessful. Former slaves were never compensated for their enslavement.”1

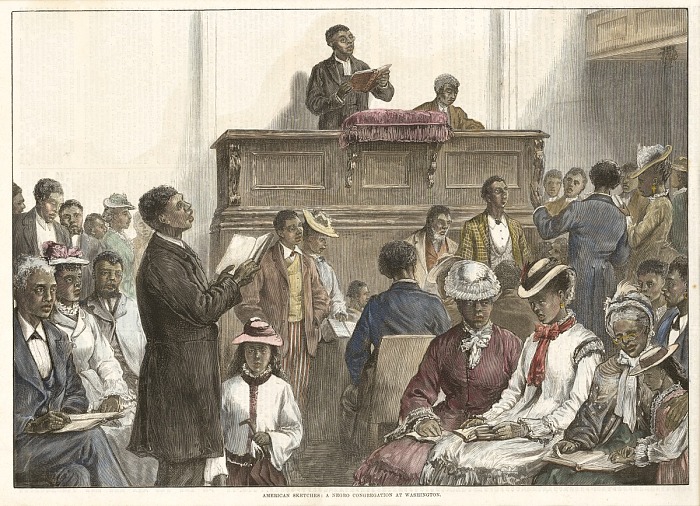

The Great Migration is a term given to the biggest population shift in American history. It is thought that six million people moved away from southern cities to the north. “With booming economies across the North and Midwest offering industrial jobs for workers of every race, many African Americans realized their hopes for a better standard of living—and a more racially tolerant environment—lay outside the South. By the turn of the 20th century, the Great Migration was underway as hundreds of thousands of African Americans relocated to cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, Detroit, Philadelphia, and New York. The Harlem section of Manhattan, which covers just three square miles, drew nearly 175,000 African Americans, giving the neighborhood the largest concentration of black people in the world. Harlem became a destination for African Americans of all backgrounds. From unskilled laborers to an educated middle-class, they shared common experiences of slavery, emancipation, and racial oppression, as well as a determination to forge a new identity as free people.”3

During the 1920s and 30s African Americans moving into large cities sought not only economic opportunity, but sought creative expression in literature, music and the arts. Many of them lived in Harlem, New York. Whites in the north complained about the influx of workers and the subsequent lowering of wages but This was a time for African Americans to celebrate the end of centuries of slavery and to enjoy pride in their culture. Writers like Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, and Zora Neale Hurston wrote about black life and culture. Actors like Paul Robeson played to audiences in the United States and Europe. He graduated valedictorian from Rutgers University despite racism and bigotry, and spent his life in support of working people and African American civil rights.

“At the height of the movement, Harlem was the epicenter of American culture. The neighborhood bustled with African American-owned and run publishing houses and newspapers, music companies, playhouses, nightclubs, and cabarets. The literature, music, and fashion they created defined culture and “cool” for blacks and white alike, in America and around the world. The Harlem Renaissance’s impact on America was indelible. The movement brought notice to the great works of African American art, and inspired and influenced future generations of African American artists and intellectuals. The self-portrait of African American life, identity, and culture that emerged from Harlem was transmitted to the world at large, challenging the racist and disparaging stereotypes of the Jim Crow South. In doing so, it radically redefined how people of other races viewed African Americans and understood the African American experience.”5

One of the most important contributions to the arts that came out of the Harlem Renaissance was Jazz. Jazz music laughed in the face of established musical traditions. The regular pattern of strong and weak beats transformed to syncopated rhythms. Musicians learned the art of improvisation that caused their music to be unique and indeed it was different each time it was performed. It became extremely popular and drew large audiences of black as well as white spectators. Black performers like Duke Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong and Billie Holiday filled the night air with music that had never before been heard. Unfortunately the stock market crash of October 29th, 1929 brought an end to the heyday of artistic flowering in Harlem, and the Great Depression settled in to wreak havoc.

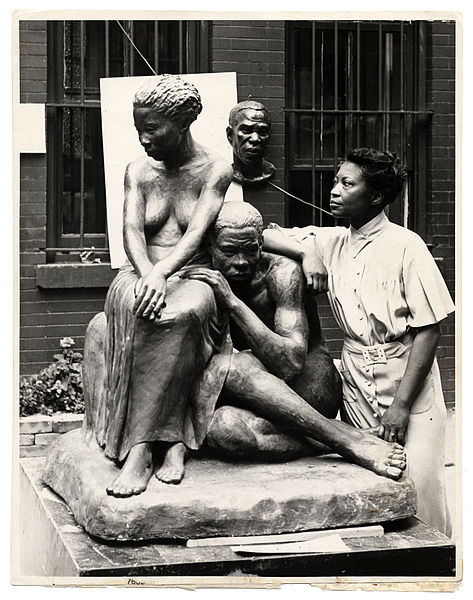

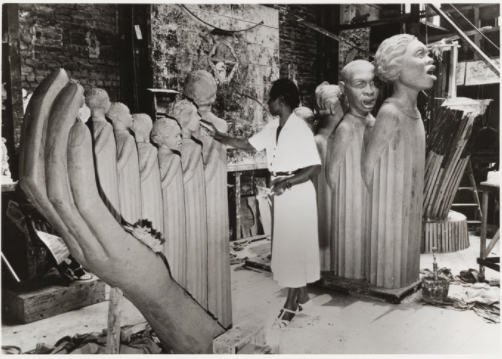

Augusta Savage

Augusta Savage, one of the most important sculptors of the time, was born in Florida in 1892. Her father strongly discouraged her work in the art world, but she persisted, although there were several years during her youth that she was not able to pursue her dreams. Eventually, in the 1920s, she left her small daughter with her family in Florida and moved to New York City. She rented a small apartment and worked as a portrait sculptor where she made portraits busts of important people. Her work was shown in the Grand Palais and the Salon d’Automne in Paris. Eventually she became a teacher in Harlem and became the first African American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors.6

“In 1937 Savage’s career took a pivotal turn. She was appointed the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center and was commissioned by the New York World’s Fair of 1939 to create a sculpture symbolizing the musical contributions of African Americans. Negro spirituals and hymns were the forms Savage decided to symbolize in The Harp. Inspired by the lyrics of James Weldon Johnson’s poem Lift Every Voice and Sing, The Harp was Savage’s largest work and her last major commission. She took a leave of absence from her position at the Harlem Community Art Center and spent almost two years completing the sixteen-foot sculpture. Cast in plaster and finished to resemble black basalt, The Harp was exhibited in the court of the Contemporary Arts building where it received much acclaim. The sculpture depicted a group of twelve stylized black singers in graduated heights that symbolized the strings of the harp. The sounding board was formed by the hand and arm of God, and a kneeling man holding music represented the foot pedal. No funds were available to cast The Harp, nor were there any facilities to store it. After the fair closed it was demolished as was all the art.”8

Jacob Lawrence

Another important artist that was influenced by the Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance was Jacob Lawrence. Lawrence was born in 1917 in Atlantic City, New Jersey and moved with his mother to Harlem when he was twelve. He worked with the CCC, Civilian Conservation Corps, during the depression and then returned to Harlem where he came to know Augusta Savage in the Harlem Community Art Center.

As the Depression continued, circumstances remained financially difficult for Lawrence and his family. Through the persistence of Augusta Savage, Lawrence was assigned to an easel project with the W.P.A., and still under the influence of Seifert, Lawrence became interested in the life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the black revolutionary and founder of the Republic of Haiti. Lawrence felt that a single painting would not depict L’Ouverture’s numerous achievements, and decided to produce a series of paintings on the general’s life. Lawrence is known primarily for his series of panels on the lives of important African Americans in history and scenes of African American life. His series of paintings include: The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, 1937, (forty one panels), The Life of Frederick Douglass, 1938, (forty panels), The Life of Harriet Tubman, 1939, (thirty one panels), The Migration of the Negro,1940–41, (sixty panels), The Life of John Brown, 1941, (twenty two panels), Harlem, 1942, (thirty panels), War, 1946-47, (fourteen panels), The South, 1947, (ten panels), Hospital, 1949–50, (eleven panels), Struggle/History of the American People, 1953–55, (thirty panels completed, sixty projected).

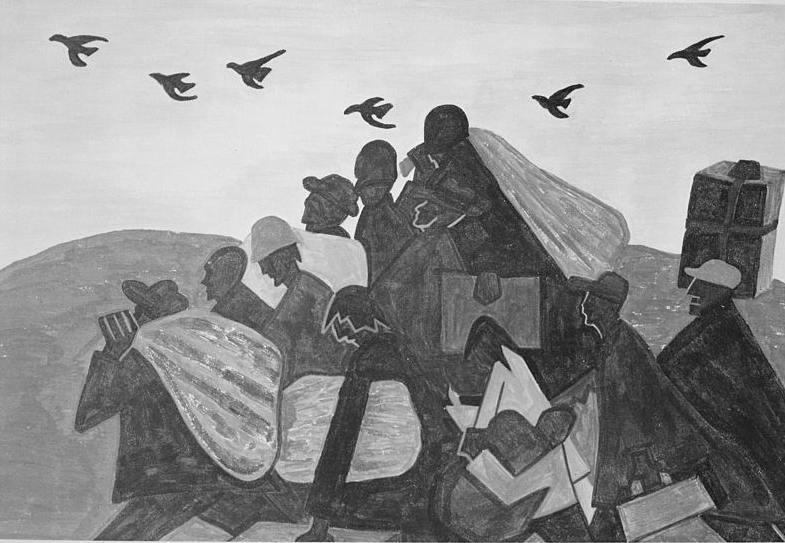

Lawrence’s best known series is The Migration of the Negro, executed in 1940 and 1941. The panels portray the migration of over a million African Americans from the South to industrial cities in the North between 1910 and 1940. These panels, as well as others by Lawrence, are linked together by descriptive phrases, color, and design. In November 1941 Lawrence’s Migration series was exhibited at the prestigious Downtown Gallery in New York.11 The series of sixty paintings was split between two museums: the even numbers are at the Museum of Modern art in New York and the odd numbers are at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. The National Archives and Records Administration has a full set of the images in black and white only. This is one of them. To see the images in color, click the link below.

Please take the time to watch the Smart History video about Jacob Lawrence’s The Migration Series: 11:24

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://smarthistory.org/jacob-lawrence-the-migration-series/

Jacob Lawrence, Migration and Movement, 2 minute interview with the artist in 1998 in San Francisco.

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/_assets/www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/audio_file/audio_file/5478/515e.mp3

The Library above may be a scene from Lawrence’s childhood at the 135th Street Library, “now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture—where the country’s first significant collection of African American literature, history, and prints opened in 1925. Everybody appears absorbed in their books, and the standing figure in the front looking at African art may represent the artist as a young man, delving deeper into his heritage.”14

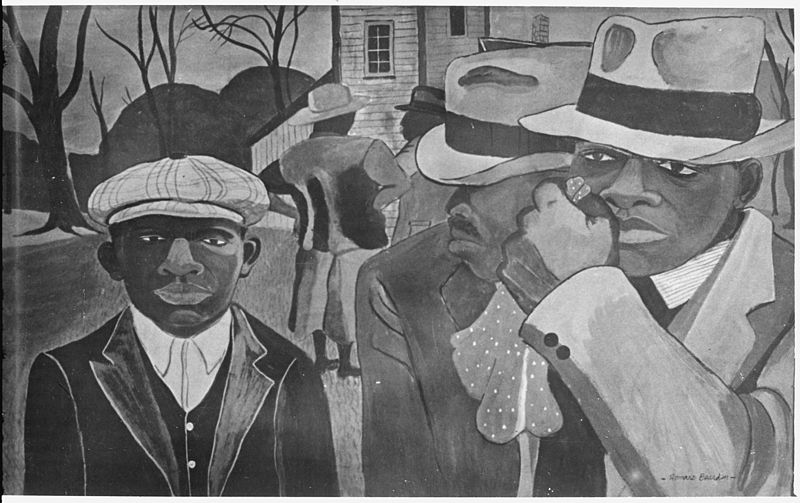

Romere Bearden (1912-1988)

Romere Bearden worked several decades as a painter and then he began working in collage during the tumultuous years of the 1960s. His success is attributed to his use of collage and photomontage to celebrate the ritual and myths of his community. Influences on his work include the Duccio and Giotto of the Italian Renaissance, de Hooch from the 17th century Dutch school, the Cubism of Picasso, as well as sculpture, masks and textiles from African art. He was a contemporary of the Abstract Expressionists. An aficionado of literature and music, he knew well several African American authors and musicians in New York where he graduated with a B.S. in math from NYU. Bearden’s family was active in the cultural and political life of Harlem. During the 1930s and 40s Bearden made a living as a social worker and worked on his art at the end of his day. In the 1940s he began to be recognized for his artistic endeavors and his art was exhibited in shows. In 1954 he married Nanette Rohan whose ancestors were from St. Martin and in later years his work reflected the tropical landscapes there.16

Bearden created his art from fragments of cut paper, snippets from newspapers and magazines, cloth, photographs, and other everyday objects. His works to some extent resemble mosaics with recurring motifs such as trains, baptism and African-American “conjure women” with magical powers.”17 He was instrumental in the formation of a group called The Spiral, which intended to understand and promote the civil rights movement and how the art community was responsible to improve rights.

For more information on Romere Bearden’s works, watch these two videos:

Romere Bearden, Factory Workers 5:47

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/american-art-to-wwii/social-realism/v/work-war-and-racism-beardens-factory-workers

Romere Bearden, Three Folk Musicians 4:05

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/post-war-american-art/postwar-figurative-art/v/romare-bearden-three-folk-musicians

1.44 Sargent Romare Bearden shown discussing Cotton Workers with Private Charles H. Alston, his first art teacher and cousin, 1944, National Archives at College Park.19