4.6 AFTER IMPRESSIONISM

The Impressionists created a stir in the art world, but that was just the beginning. From this point forward artists were not willing to color within the lines or live by the rules of the Salon. Each new “ism” brought new ideas and then ventured into new, uncharted territory. Art would never be the same. Several artists took their cue from the work the Impressionists were doing, but they were not satisfied with following the Impressionist’s rules. Within the same circle were friends and acquaintances that took an idea here and a process there, and then went down their own path. We will look at Paul Cezanne, Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gaugin, and George Seurat as examples of the new art that grew at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century.

Paul Cezanne

Paul Cezanne (1836-1906) was a life-long admirer of the great colorist, Delacroix. As you look at his work, pay attention to his use of color to create objects rather than his use of drawing to create shapes. He linked himself with the Impressionists and he especially liked their theories of color and their reliance on subjects chosen from everyday life. However, he was not satisfied with their lack of form and structure. “I wanted to make of Impressionism something solid and lasting like the art in the museums.”

He used these Impressionist ideas in his art:

- Pure, bright colors and a light palette.

- Short, vivid strokes that broke the color into small sections.

- Multiplicity of color and light which led to a blurring of outlines or no outlines at all.

- Form was achieved by color as well as line.

- All sections of the picture advance at the same time.

But Cezanne went beyond Impressionism.

Here are some of the ideas that were new:

- He used uniform, rectangular brushstrokes arranged in diagonals, creating a carpet like surface.

- His volumes were weightier.

- He attempted to build forms, not dissolve them.

- He disliked linear and aerial perspective.

- He depicted equality of intense light.

- Since cold colors recede and warm colors advance, he modeled with color. He used color to give depth and distance, shape and solidity.

- His methods enabled flatness and depth to be apparent at the same time.

- He treated natural forms in their simplest and broadest dimensions, rather than having replaced them with geometric constructions.

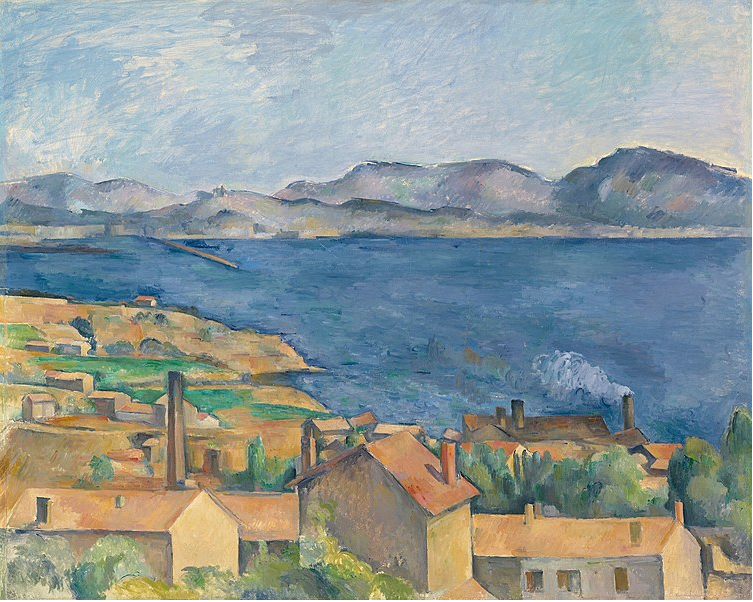

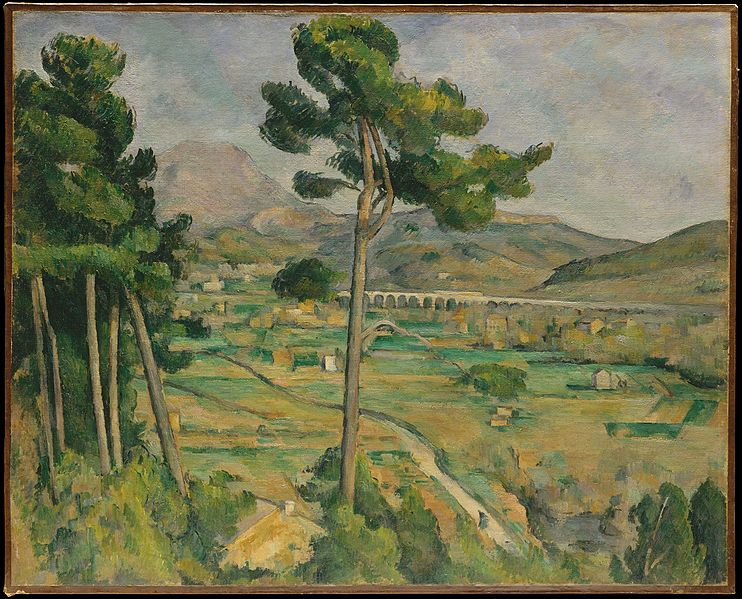

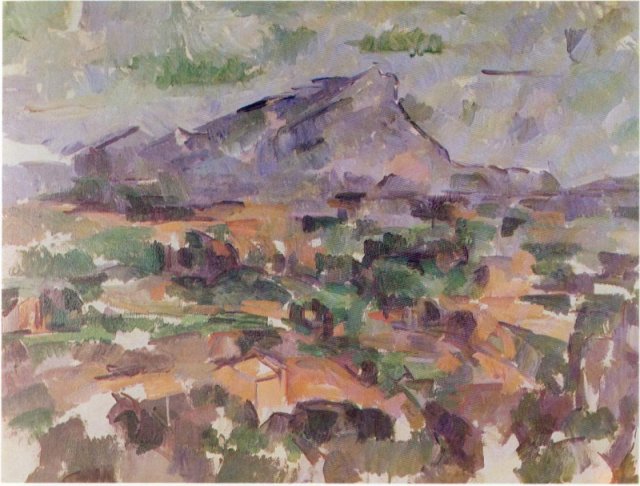

Cezanne’s earlier works experimented with these methods. Note how the Bay of Marseille seems to stand on its end, a flat surface of water reaching upward to the sky on the same plane with the houses and the mountains behind it. The tiled roofs are not divided by individual tiles, but are a patchwork of mixed colors. Each object has its own colorful outline or shadow. Cezanne was not interested in historical subjects. His work focused on the landscapes and objects and people he saw around him. Mont Sainte-Victoire was near his home in Provence, France, and he often painted it.

Look at the two views of the same mountain that were painted a little over twenty years apart. Notice how he intersects patches of color to create the scene. In the earlier work it is possible to see the gently rising valley, a road with local peasants traveling toward the mountain and the arches of the aqueduct along the base of the foothills. But in the later version there are only a few clues to help us understand what we are seeing. The colored patches have become mathematical shapes and are no longer recognizable as buildings of roads or trees.

Many of the works of Cezanne were what we typically call still life. He wanted the viewer to enjoy the formality of a still life without using formal perspective or chiaroscuro, but his viewpoint is ambiguous.

We are looking straight at several pieces of fruit at the same time that we look down at others. We look down on the table, but straight at the bottle. This is sometimes called simultaneous perspective. Overlapping gives us the impression of depth, but we are left confused. Dark outlines are used to lessen the effect of perspective. He wants us to see flat fruit even when the colors are used vividly and seem to model the spherical shapes. There is an equality in the intensity of light, no single light source is important. He uses a full, warm palette, but the floating color of the Impressionists has become interlocking planes of color. The sharp edges make each plane seem sculptured. This could be called “architecture of color”. The brushstrokes are short, even, and not well blended. They are applied in a uniform, organized size and shape.

The Still Life with Onions was also painted in 1895. Cezanne was attracted by the poetry of simple, everyday forms and he painted them on the same, scalloped table as the Still Life with Peppermint Bottle above. Some of the ideas are taken from earlier works, such as placing a knife diagonally the way Chardin did to create space. The drapery stands out just as the bottle does, against a totally empty, neutral background. The drapery on the right extends downward balancing the upward thrust of the bottle on the left. The objects are seen from several different viewpoints at a time, a technique which will influence the cubists of the next generation. He painted objects chiefly in one hue, using the intensity of the color rather than the traditional method of modeling in light and dark.

Cezanne was not interested in portraying psychological aspects of his sitter. Mademoiselle Cezanne in Yellow is a portrait of his wife, who was shy and humble, and would not upset his irritable nature. Cezanne asked absolute stillness, the stillness of inanimate objects like the vegetables and fruit. “Do apples move?” he crossly asked a sitter exhausted from holding a pose for a long time. He used vivid color to paint his wife, and that made her look huge. She does not seem to exist in the same space as the chair. He has treated her shape as a flat plane, and the back of the chair looms above her. The geometric area of the color plane pushes forward and we are aware of the egg-shaped head and the disproportionately long left arm. This is disturbing to us because we know what a human body should look like and it bothers us that she is distorted. Other objects in nature can be distorted without making us uncomfortable, but not the human form. Remember the Impressionist idea to deemphasize the subject matter: this is an example of that idea.

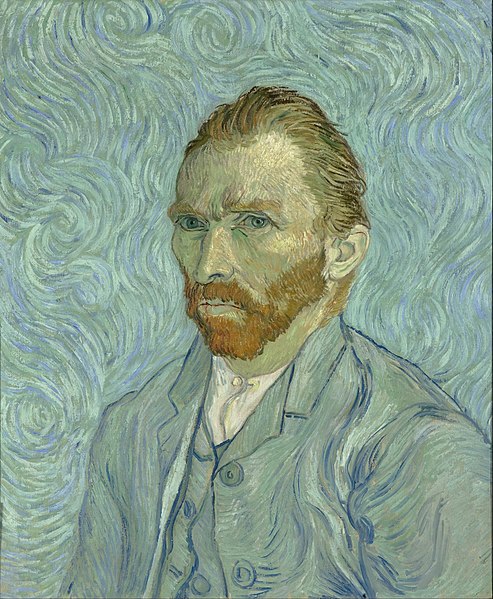

Vincent Van Gogh

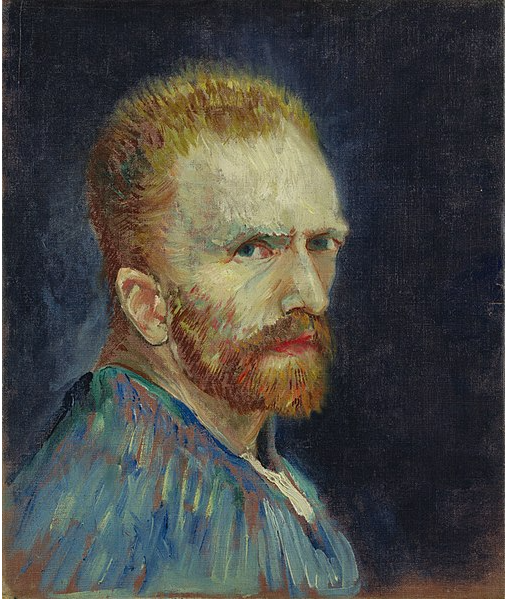

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) was the son of a Protestant minister and a Hollander by birth. He believed he had a religious calling and did missionary work in the slums of London and in the mining districts of Belgium. However, he failed his examinations for the ministry because he was not able to pass the Latin and Greek test. His repeated failures cost him his health and brought him to the edge of despair. He often returned to his family home to restore his health and catch up financially. Van Gogh was a very intense man who looked at painting as a religious experience. We have a rich source of his thoughts and feelings in the letters he wrote to his brother Theo, to whom he was very close.

Van Gogh’s work has very recognizable characteristics:

- He transformed reality into imagination

- His expressive line created intense emotional expression

- He drew directly on the canvas with his paintbrush and used an impressionistic palette

- His use of color included the juxtaposition of unusual colors

- He believed that color would create an expressive picture of an individual and their feelings and emotions and yellow was his favorite color.

- His brushstrokes were cross hatching, dots and dashes. The thickness, shape, and direction of his brushstrokes created a tactile counterpart to his intense color schemes.

In his later years he especially liked heavy impasto, swirling brushstrokes, and dynamic compositions.

Van Gogh often painted the poor working class people around him. His painting Noon – Rest from Work, is reminiscent of works by Jean-Francois Millet such as The Angelus. A comparison of the two works shows how different van Gogh’s technique is from the more classical work of Millet. His use of color and his brushstrokes are very different.

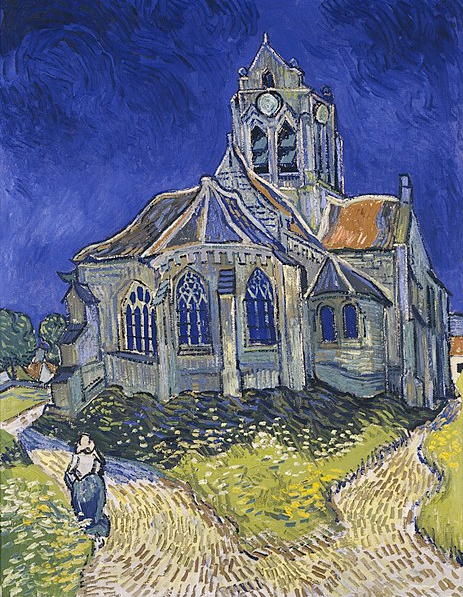

The Church at Auvers sur Oise painted in 1876, was not intended to look like a photographic image, but was instead an expressive image of the church near his home. Neither the colors used nor the lines of the building are realistic. Notice how the path goes toward the church, but the church seems to forbid entry and no door welcomes parishioners. Could this be an expression of his feelings about “the church” and his failed attempts to become a minister? There is some perspective indicated in the trails that recede and the diminished size of the trees on the left, but this is not correct linear perspective. The lines are expressive, the modeling is not uniform, and this does not seem to be a real building. The entire church seems to be in shadow and the light is directly above. He uses broken brush strokes applied in directional patterns, almost as if he feels unable to approach the church, but is instead swept around it by the current of paint in the pathway. He uses blue and orange, which are complimentary colors, and they therefore create tension. This is a method taken from Japanese prints. Shadows are created with color rather than black, and most of his colors are cool rather than warm.

The Bedroom at Arles and van Gogh’s Chair also use color and perspective expressively. He uses bright blue, yellow, and orange. This is not a real room as the occupant would have painted it. The perspective is not correct and is emphasized by the treatment of the floor boards and the tile. It is not possible to tell if the window opens into the room or out to the neighborhood. Outlining flattens the furniture, not allowing the eye to go past the edges or to imagine a curve. Does the furniture seem to sit flatly on the floor or would it slide toward the viewer? The bedroom was painted during a lonely period in his life. Even though he lived alone there are two chairs, two pillows on the bed, and two portraits on the wall.

In Starry Night, van Gogh does not see the sky as we see it, but he feels the violence of the universe, filled with whirling and exploding stars and galaxies of stars, beneath which the earth and men cower, anticipating a cosmic disaster. He does not see the harmony of nature, but the violence and mystery of the heavens. Men live in tiny homes in the town below, trembling in fear. He uses bright blue and yellow swirling brushstrokes, and makes no attempt to blend the colors.

Starry Night 5:08

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://smarthistory.org/van-gogh-the-starry-night/

Van Gogh Irises 7:42

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7x6tubojjY8

Van Gogh’s art was not well liked by the public or art critics during his lifetime. Although he often painted several paintings a day, he rarely sold them and few art critics or members of the public saw his vision. He is known to have frequented taverns and painted the walls with landscapes and flowers for meals. He often visited the workshop of Julien Tanguy, who he called Pere (father) Tanguy. Many of van Gogh’s works were given away or sold for pennies to bartenders, shop owners or prostitutes so he could survive and continue painting. It is likely that much of his work is lost due to this.

It was in Tanguy’s shop in Paris that Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cezanne met one day, as both frequented his art studio. The two artists began discussing their different ideas about art and van Gogh showed Cezanne some of his portraits and landscapes. Emile Bernard says this about the meeting:

Vincent van Gogh lived a very difficult life and it was many years before his work was appreciated. He suffered from bouts of mental illness, drank heavily, ate poorly, and never had a stable home life. He spent some time in the mental hospital at Saint-Remy and died in July 1890, never knowing how valuable his paintings eventually became.

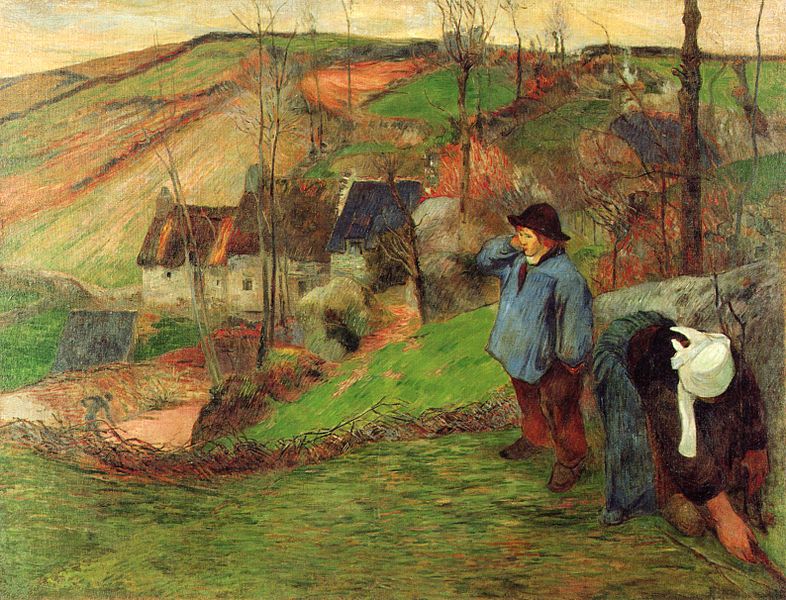

Paul Gauguin

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) was born in Paris in 1848, the year of much revolutionary disturbance. His father wrote for a newspaper that was suppressed by the French government and they were forced to flee. Paul spent some time in Peru and lived a privileged life until his extended family fell from power and he traveled with his mother back to France where she worked in a dressmakers shop. Paul attended school and joined the French navy for a time. He then went to work and became a successful stockbroker, pursuing his painting as a side venture. In 1882 the Paris stock market fell and Paul decided to paint full time. He married Mette-Sophie and they had five children, but he was not happy living in Copenhagen and did not speak Danish. His early works depicted small towns in Brittany, but he soon left Europe to find himself in Martinique and then settled in Tahiti. He continued to write to his wife, even while living on the beach in Tahiti with his mistress Tehoura, but his separation from his wife and children eventually became permanent and they were divorced in 1894. He left his family behind to fend for themselves and Paul buried himself in the outskirts of the city of Papeete. He made a few trips back to Paris from Tahiti, but his heart was in the islands.

Vision after the Sermon or Jacob Wrestling with the Angel 3:38

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y5lhKvKvWPg

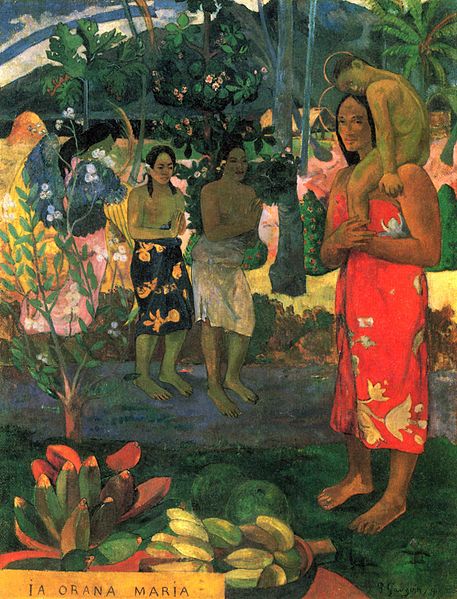

In Tahiti and the Marquises where he spent the last ten years of his life, he expressed his love of primitive life and brilliant color. The design is often based on native motifs, and his pink, lilac, and lemon colors are taken from the tropical flora of the islands. He represents a new rebelliousness against artistic tradition and the whole of European civilization. He believed that civilization made you sick and his new inspiration came from Japan, the Pacific Islands, and much of the non-European world. He used an unprimed canvas which allowed the oil to be absorbed into the fibers. He was a follower of the idea of synthetism which meant he created unreality, simplified forms and color, used expressive line, depicted the anti-scientific, the anti-rational and escaped science and the rational world.

It was through the Tahitian women who were his successive mistresses that the artist encountered melancholy in the Polynesian people he associated with. Notice the broad, space denying bands of color that link the two women in the foreground. He uses bold colors and accentuates their squat bodies to make them seem even fatter. To him this accentuated their primitive nature. Although the bodies retain their volume, the background is reduced to superimposed planes that seem to move upward into space rather than to recede back to ocean, waves, and perhaps a distant island.

In his work Arearea, the Red Dog, Gaugin concentrates on a single hue, red. The dog is symbolic and the lines are curved and sensuous. The foreground looms forward and the horizon is high in the background. He believed that a person was entitled to paint using his own thoughts, ideas and dreams. This could be accomplished by the use of arbitrary line and arbitrary color. The shape of an object was not important, reality was not important. True creativity lies in the ability to convey our feeling of otherworldliness, by being drawn in an unreal, snakelike fashion. He used Cloisonnism to describe these dream like feelings and to simplify the shapes, colors, and lines. Cloisonnism refers to the technique of breaking colors into planes much like the cloisonné jewelry which is divided into planes of pure color. Tints and tones are ok, but there are few areas of mixed colors.

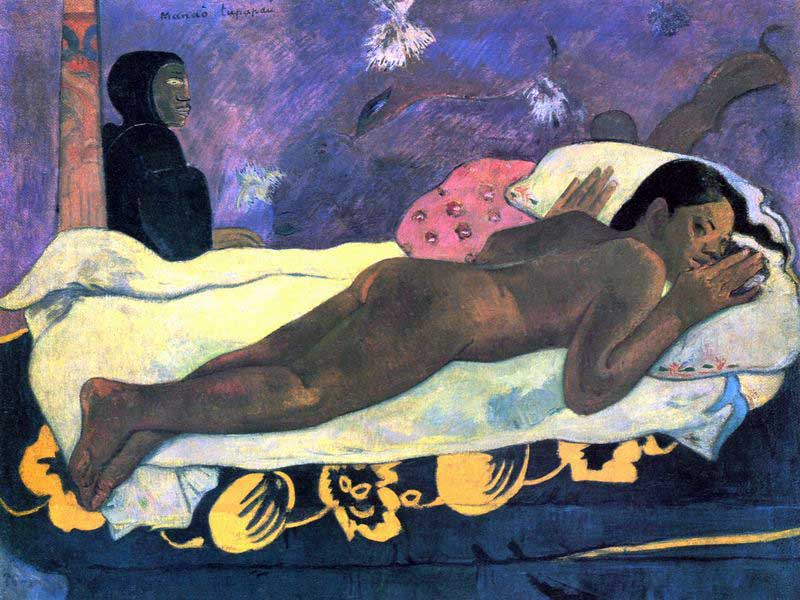

Gauguin’s Self Portrait of 1893-94 was completed after his first return to Paris from Tahiti. In the background are paintings of his for which he had particular affection. Also notice the swaths of color on the wall behind his head and the colors he used in his own face. Notice a version of “The Spirit of the Dead Watching” painted in 1892. We can see a larger version of the painting in figure 4.102. Gauguin used dark purples on the wall behind his teen aged girlfriend and painted a tiki like figure in black standing watch behind her. Or, is the figure in black a figment of the girl’s imagination? Gauguin was not forthcoming about its meaning.

Paul Gaugin, Self-Portrait with Portrait of Emile Bernard 5:31

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxiQ_EZNTrc

George Seurat

George Seurat (1859-1891) was born to a comfortable family. He spent two years in the studio of Henri Lehmann and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, but left for a year’s military service in Brittany. He only painted for nine years after he returned from military duty. He was said to have been handsome, robust, and relatively tall for his time. In his maturity he produced 66 oil paintings on canvas, 170 works of oil on wood panels, and 230 completed drawings. He began his studies in mathematics, logic, and organization and his math background probably led him to impose scientific discipline on Impressionistic ideas. He never married but had a son by his working class mistress. He died at the age of thirty two of diphtheria, and two weeks later his infant son also died.

Seurat read the latest scientific treatises to discover how they might be applied to art. He read “Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors” by the Frenchman Michel E. Chevreui,26 “Phenomena of Vision” by David Sutter, from Switzerland, and “Modern Chromatics” by the American O. N. Rood,27 a Columbia University Professor. So he was interested in scientific theories of color and the laws of optics. He knew that color achieves maximum intensity when placed next to its complementary. Colors are toned down or intensified by adjacent colors. He relied on the optical mixture of pure color on the retina. Color is not intuitively applied, but is scientifically applied. Each color must be dry before the next may be applied so there will be no blending.

There were two main theories put forward by Seurat. The first was pointillism. This placed dots of pure color next to each other leaving bits of the white canvas showing between the dots. In this case the white remains partially exposed and hence it is visually functional. He did not like the term pointillism, and was offended if his work was called by this term. The other term is Divisionism, a system of painted small dots that stand in relation to each other. Both were difficult procedures which required discipline and painstaking effort. His work also included a kind of gaiety created by luminous, warm color, and lines above the horizon moving upward. He also created sadness using dark cold colors and lines moving downward. Therefore he believed he could create calmness by using equal portions of light and dark, warm and cold, and a horizontal line that veered neither up or down. He used dots to deny the artist’s personality in the brushstroke and to avoid accidents of the brush.

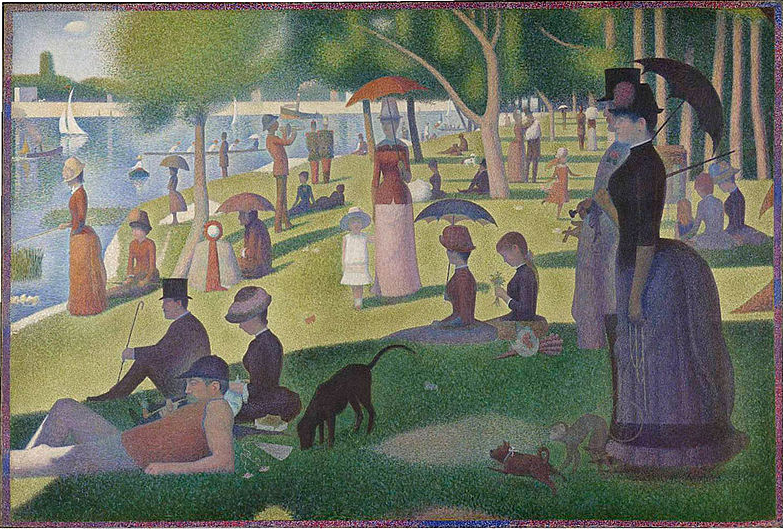

One of his best known works is A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. This painting took over three years to complete and was preceded by more than thirty oil sketches. Seurat believed that optical mixing of colors produced more luminous and vibrant colors. In fact the colors seem more muted, partly because the paints he used had a tendency to fade and partly because human vision does not respond precisely as the scientist of the day thought it should. In this painting the reds and blues are preserved, but the Veronese green is now olive-green and the orange tones which represented light are only holes. Seurat would lay down an area of approximate color, such as green, in a patch of grass, and then proceed to superimpose many tiny strokes to correspond to the influence of the colors of nearby objects. With other strokes he indicated direct light and with others he indicated reflected light.

Seurat – A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte 6:42

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://smarthistory.org/georges-seurat-a-sunday-on-la-grande-jatte-1884/

Seurat – Bathers at Asnieres 6:26

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://smarthistory.org/georges-seurat-bathers-at-asnieres/

He was also concerned with the placement of the figures to create the balance, calm, and dignity of the Italian Renaissance painters such as Piero della Francesca. His figures are almost always frontal, back or profile view, and are so logically and precisely placed that they seem immovable. The space is like a stage, set formally with geometric forms. The brushstrokes produce a surface pattern, which denies depth and perspective. The pattern here is based on the verticals of the figures and the trees, the horizontals in the shadows and the distant embankment, and the diagonals in the shadows in the shoreline. The picture is filled with sunshine, but not broken into patches of light or color. This is severe intellectual art and is not meant to be emotionally understood. It is more like machine made art. For Seurat color is the reality and spaces and solids are merely building blocks. His work may be seen as the forerunner of the 20th century techniques of photoengraving and reproduction.