4.3 NEW IDEAS IN PAINTING

The late 19th century could be called the time of the isms. There were so many different movements in the arts, that it became difficult to keep track of them and to qualify them. Much of the new type of art had its start in France, perhaps driven by the political changes surrounding the many different governments that came and went. Just as politicians, emperors, kings, and presidents came and went, so did new ideas in the arts.

Édouard Manet (1832-1883)

Édouard Manet was born in Paris to an affluent and important family. His father wanted him to become a lawyer, but his uncle supported his desire to become an artist. For several years he took art classes, copied the old masters at the Louvre and studied art in the Netherlands, Italy and Spain. From the beginning of his career he did not faithfully follow what he saw in the paintings of the masters. One of his first, most important works is Luncheon on the Grass, painted in 1863.

There were five thousand works submitted to the Salon of 1863, and of those 2783 were rejected. This was one of the rejected works. The rejected of so many works prompted the creation of a new exhibition; the Salon des Refuses which was intended to give more artists the ability to show their work. Some art historians classify this work as Impressionism, while others see it as a precursor to the Impressionism that was soon to become popular.

Manet’s work is a tribute to an earlier work by Titian, Pastoral Concert, painted in 1510, which was owned by the Louvre and would have been known to Manet. The depiction of a nude woman with fully clothed men was not the problem. Titian’s women could have been interpreted as muses or goddesses. But Manet’s woman looks out directly at the viewer. She is depicted not as a muse, but was more likely a prostitute whose identity was known. The nude woman looked suspiciously like a combination of his wife and Suzanne Leenhoff, a female model and likely a lady of the night. So in its time this work was considered pornographic. But in addition to that, Manet did not blend his brushstrokes or provide any shading or blending on the edges of the figures. It is not even possible to tell where the grass ends and the water begins. So his work was considered pornographic and unfinished. It caused a scandal.

Luncheon on the Grass by Manet 6:14

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/manet-le-d-jeuner-sur-l-herbe-luncheon-on-the-grass-1863

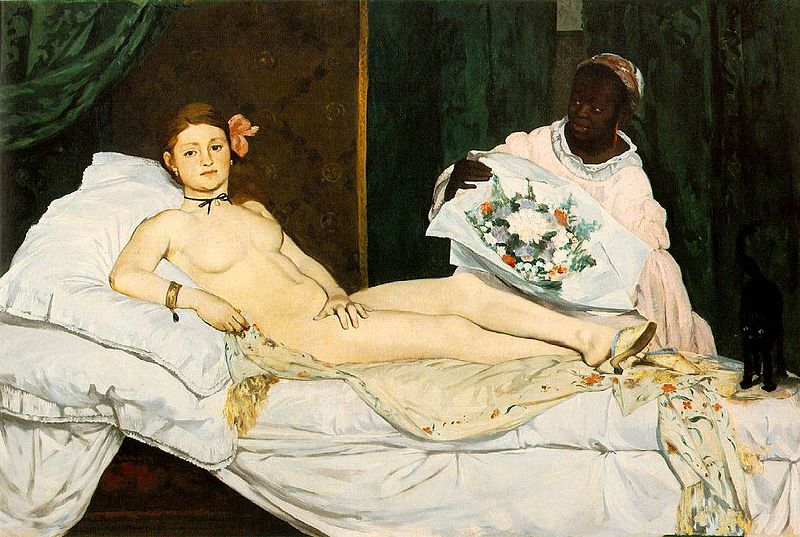

Olympia, painted by Manet in 1863 was also based on a work by Titian, The Venus of Urbino. Titian’s model is a goddess, who is nude, while Manet’s Olympia is a modern woman, confronting the viewer with her direct stare, promiscuous, and unconforming.

Olympia, by Manet 8:03

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/manet-olympia-1863-exhibited-1865

The dog at the foot of Venus is a symbol of marital fidelity while the cat at Olympia’s feet is the symbol of promiscuity, perversity and eroticism. The rose symbolizes purity while the orchid is an aphrodisiac. One servant arranges clothing in the cassone, a marital hope chest commissioned for a wedding, while the other servant presents flowers which may have come from the stranger standing in our space, the person the Olympia is looking at so intently. Manet applies his colors freely and does not blend the brushstrokes.

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/manet-mile-zola-1868

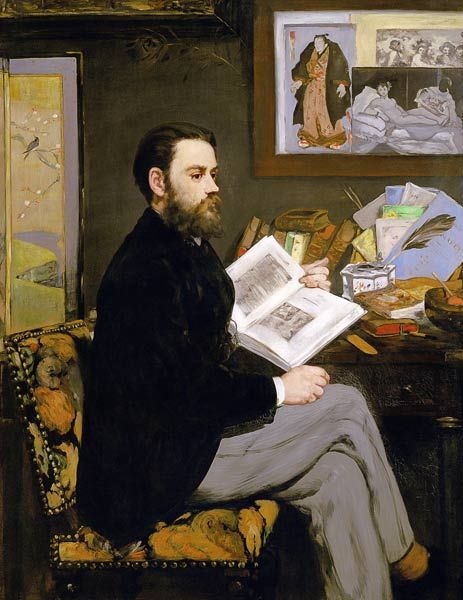

Emile Zola was an art critic who lived and worked in Paris. He saw Manet’s work and wrote positively about it in 1867. Manet was grateful, so he painted this portrait. Notice a print of Manet’s Olympia on the back wall, as well as a Japanese block print, a Japanese screen and copies of some of Zola’s pamphlets.

People depicted in Manet’s The Balcony are his friends, Berthe Morisot, Manet’s sister-in-law, the painter Antoine Guillemet, and Fanny Claus, a violinist. Although they were friends and were obviously sharing a social moment together, they seem to ignore each other and look out into the distance at something different. The painting was shown in the Paris Salon in 1869 but was not well received. The individuals in the painting do not seem alive and seem more to be pasty sculptures, stiff and like the objects in a still life.

The Balcony by Manet 4:02

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/manet-the-balcony-1868-69

A bar at the Folies-Bergère 5:38

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/manet-a-bar-at-the-folies-bergre

By 1881 Manet’s style became even more “impressionistic.” The brushstrokes are loose and unblended. We see the woman who looks out as us, but we also see her back and the man she is talking to. He seems to be in our space. Behind us the huge room is a crowd of people celebrating and enjoying the follies, including an acrobat whose green shod feet we see hanging in the upper left corner. The artificial lights glare everywhere, enlightening the modernity of the events occurring.

Camille Pissaro (1830-1903)

Camille Pissaro was spoken of as the father of the Impressionists. His paintings contained most of the ideas of the Impressionistic school, but with more structure and more solidity in his composition. He was friends with Monet, Sisley, Cezanne and was older than most of them. He was initially influenced by Corot and his style changed with the company he kept. He had six children and sometimes had to take odd jobs, such as fan painting, to support them. He never sold a single painting during his lifetime. He was solidly a socialist. He painted country landscapes and cityscapes which were simple and firmly constructed. All of the areas of his paintings are clearly defined, so a road is clearly a road receding into the distance, and a river or a valley is easy to understand. Pissaro did not live long enough to see his style of painting recognized and gain acclaim. He abandoned Impressionism in 1884.

These are his ideas about painting:

- Do not be too specific about defining an object

- Cover the canvas as completely as possible at the first sitting

- Paint the feeling of an object, not just its external outlines

- Paint the essential character of an object

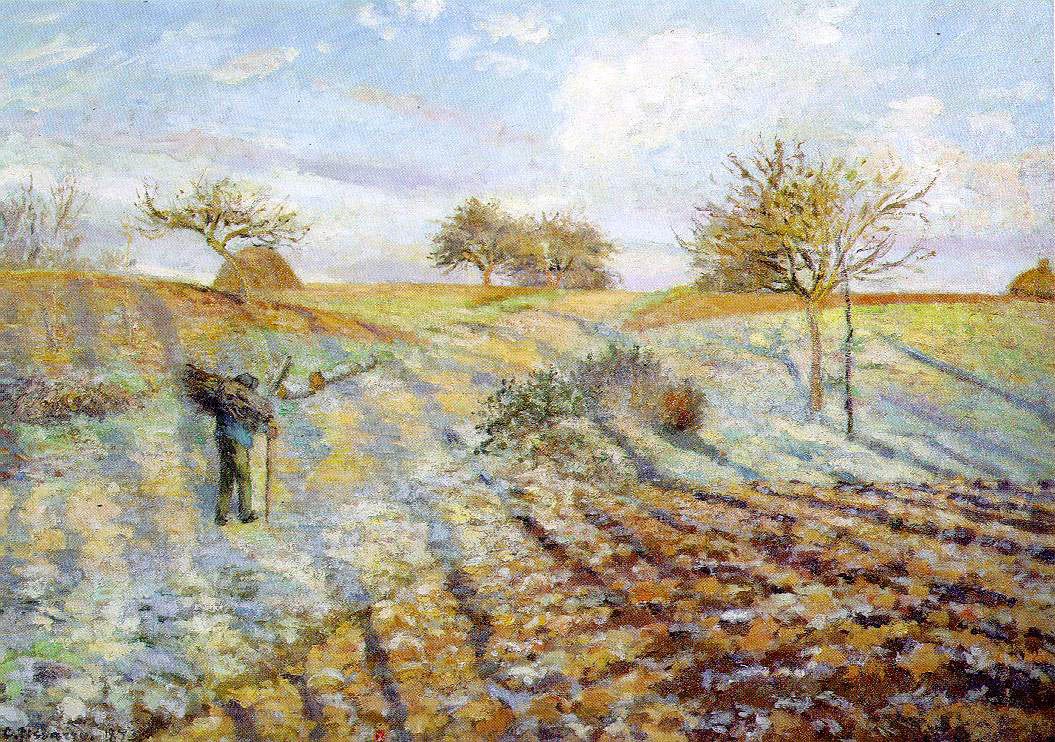

Pissaro’s Hoarfrost follows these rules. Here a farmer, laden with sticks to keep his home warm, trudges through the cold winter landscape. The winter sun is low on the horizon and casts long shadows. Notice that Pissaro does not try to define the furrows of the field exactly. Instead he lays dabs of paint next to each other in small strokes. These dabs do not necessarily depict the actual colors that a viewer might see, but instead are intended to convey cold. So the colors include frosty blues and grays mixed with the colors of the earth. He wanted to convey a cold moment in time rather than the exact colors he saw. Also notice that he is less concerned with the specifics of the road and the furrows, and more intent on conveying the feeling of cold. Critics in the Independent Salon said this work looked like the scrapings of a dirty palette.8

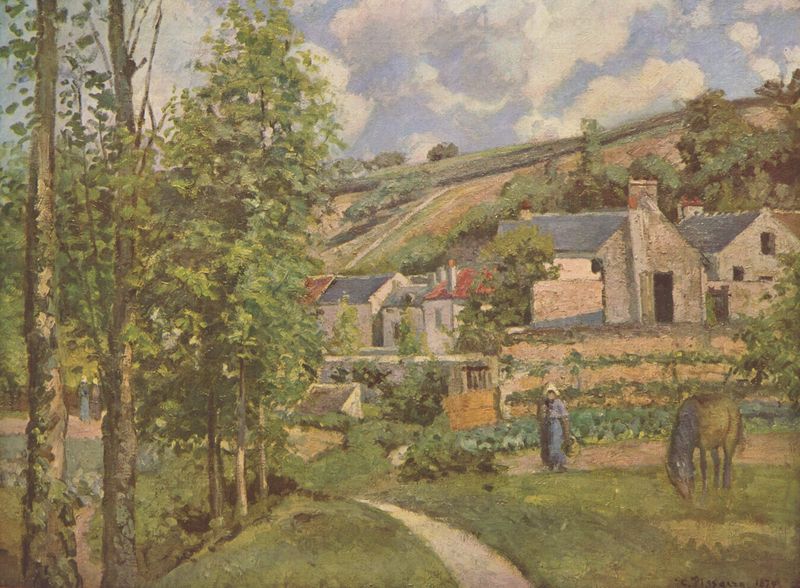

The Landscape of Pontoise depicts a town where Pissaro live for twelve years. This work has a much stronger use of linear perspective than Hoarfrost. He uses unusual colors in the shadows of the wall. The focus is the small group of houses rather than a person or an event. It is a genre scene, a moment in time. It is clear but unfocused, and conveys the feeling of a fresh spring day.

In 1884 Pissaro moved to Eragny on the Epte River and met Seurat and Signac. At Eragny he saw the experiments of divisionism and pointillism, which we will look at in our next chapter. After the revolutions in France, the government realized how difficult it was to keep order in the old, narrow, medieval streets. Think about the barricades of the battles in Paris and how difficult it was to control the revolutionaries. City planners, such as Baron George-Eugene Haussmann, known as the Demolisher, carved new, wider streets in various places, and this was one of them. They also added clean water, modern sewers, gas lanterns, parks, schools, asylums, prisons and administrative buildings. Wider streets also enabled more commerce and provided access for the commoners, not just the military troops.

In 1897 Pissaro turned his efforts back to cityscapes. He was bothered by an eye infection which made it difficult to continue to paint plein aire, or outdoors. Inspired by Monet’s series paintings, he took an apartment above the newly renovated Boulevard Montmartre in the Hotel de Russie on the corner of the Boulevard des Italiens and the Rue Drouot, and painted the increasing population of Paris and its change from horse drawn carriages to automobiles. There are fourteen paintings in his Montmartre series. This is still an Impressionist painting, even though it is late in his life. Notice how he uses color to depict the street in the distance rather than using strong lines. This depicts a fleeting moment in a busy city full of people living their daily lives. It is not a portrait, but a feeling of a moment. He used his short brushstrokes and painted everything quickly to show his idea of a world in motion.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

Renoir was one of the greatest colorists of all time. When he was fifteen he was no longer in school, but got a job in a china painting factory. In the evenings he attended free classes in drawing and he soon began to paint copies of the masters in the Louvre. When factory-stamped china began to take over the market, Renoir moved out of the industry and entered the studio of Charles Gleyre. There he met Monet, Sisley and Bazille. He and his friends were impressed with the work of Courbet and the outdoor landscapes of the Fontainebleau School which included Corot, Daubigny, and Diaz. The young painters began to paint outdoors using the subjects they saw on the spot. They lightened their palettes and began to discover that by breaking their brushstrokes up into little streaks and dabs they could come closer to the effects of nature, its hues, moods, and vibrancy. This was the beginning of the Impressionist movement. In 1864 Gleyre closed his studio and the artists were out in the street. During this period the artists were in very poor straits and Renoir learned to be frugal. They stuck together, shared rooms, bought each other’s paintings and traded paintings for sacks of beans. Eventually many of Renoir’s paintings were brought to the United States where he was more popular. The American buyers kept him afloat. It was not until 1874 that the first Impressionist show was organized. During this time Renoir traveled to Italy to see the work of Raphael and other Renaissance artists and became dissatisfied with his own work. He changed his style, used a drier palette and concentrated more on line and drawing than on color. The public began to appreciate his work. The last twenty years of his life he suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and his hands became like claws. He continued to paint, and even painted from a wheelchair. His last painting was done on the day he died.

Renoir was considered a figure painter. He never abandoned the human figure like Monet did. He enjoyed the human form and his work was thought of as gutsy and earthy. Some thought of him as a womanizer. He loved painting women and thought of them as symbols of life. In his paintings they radiate warmth and charm. Many of his paintings show light moving through the trees and onto skin. His work The Swing shows a young woman and her companions outdoors on a sunny day. The sunlight filters through the leaves of the tree overhead and becomes muted on the clothing and skin of the people below. It is a serene, relaxed moment with no struggle and no painful search for meaning. The brushstrokes are loose and the surface of the paint is broken. This is not a planned setting, but is a casual moment of daily life. Renoir uses more black paint than some other Impressionists.

Renoir: The Swing 4:32

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=69zJ3UDh5Tw

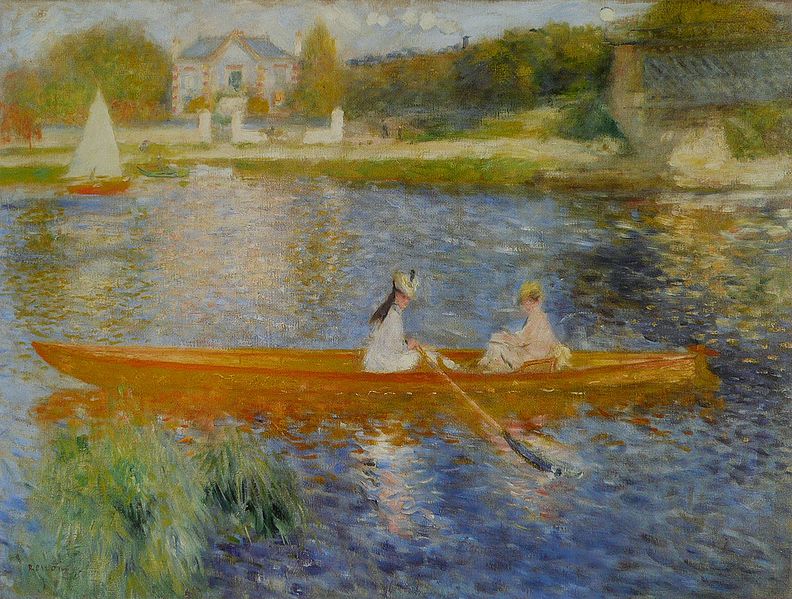

Another early work that recalls the work of Monet is The Skiff. It was painted somewhere west of Paris, although the exact location is not known. In this work Renoir juxtaposes the blue of the water and the orange of the boat, which are complementary colors. Placing complementary colors next to each other intensifies them. Here is brushwork is also loose and choppy.

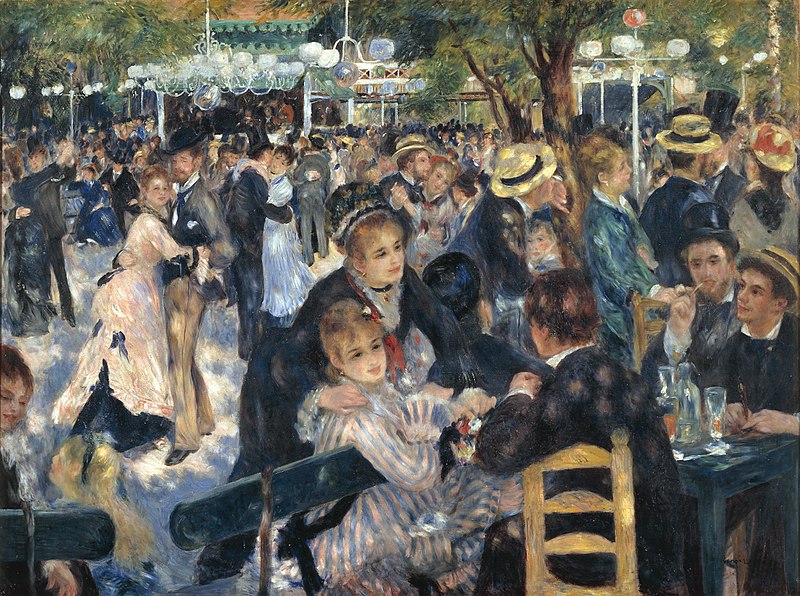

The Moulin de la Galette was also painted in 1876. It is a genre scene and is a painting of a popular Paris restaurant and dance pavilion for the working class. It is a page of history showing the happy, uncomplicated and even joyful young people of Paris. They crowd around their tables laughing and talking while others dance energetically. Note that some of the figures are partially cropped, suggesting that the reality of the event continues beyond the edge of the page. We are not observing a performance on a stage set, but we are part of the action. These people are not aware of our presence, but go about their happy business. Renoir catches nature unaware in a moment that will never occur exactly this way again. The dappled light on their clothes is blurred into the figures themselves. He uses linear perspective, placing those folks who are in the background higher up on the picture plane, and he uses size variation and overlapping to create deeper space. So even though he uses the normal tricks to create depth, it is a momentary and passing event.

Moulin de la Galette 4:56

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6amlRsb1n4

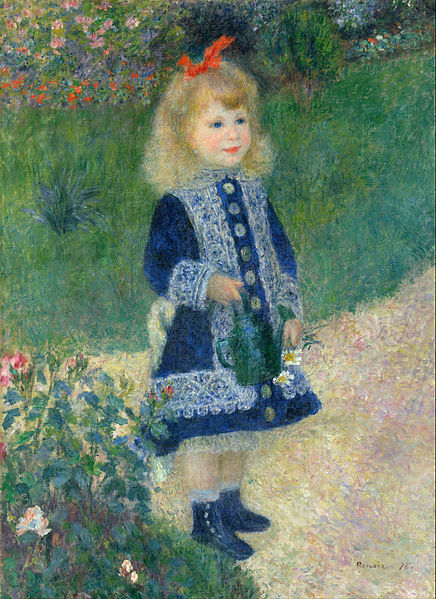

Girl with a Watering Can uses an oblique angle in the grass and the path behind her. Notice how many colors he uses in the gravel path under her feet. The surface is broken and you can still see his small brushstrokes. It is an unimportant, happy moment that is unplanned and happens outdoors.

The Luncheon of the Boating Party 6:16

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://smarthistory.org/renoir-luncheon-of-the-boating-party/

His most frequent model was his family, and Gabrielle and Jean is one of those. It is an intimate moment between a mother and child playing with toys. It is indoors rather than a painting of nature, but he painted flowers on the wall in the background, almost as if he wanted it to seem as though they were outdoors.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

Edgar Degas was born into a wealthy family. He had a private education and studied in Rome. Here are some thoughts from his notebook:

Drawing is not the act of photographic recall, but the ability to see an object in the mind’s eye and by means of certain inequalities, to reveal an aptitude, will, and form that are entirely personal. So it is the personal power to transpose and recreate.

- Study a figure or an object from every view point

- Do portraits of things that do not move and instead move the painter to catch the views

- Make portraits of people in familiar and typical positions and give their faces the same choice of expression one gives their body.

- Unlike Renoir who emphasized the positive, Degas simply painted what he saw, stressing neither bad nor good. His psychological approach distinguished him from the other Impressionists.

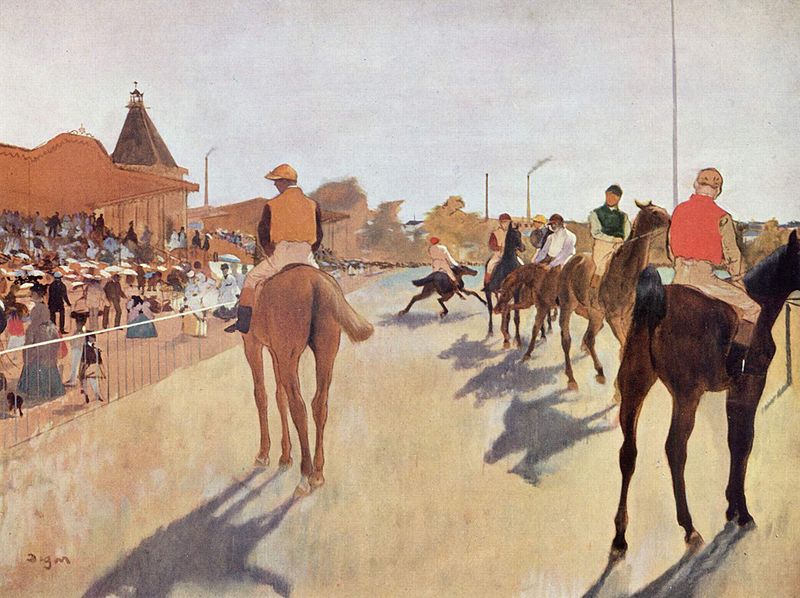

Degas was not really interested in landscapes except for what could be seen at the horse races. This was his effort to focus on the contemporary life he saw around him. He captures light in a unique and flat way. The people and the horses are in mid movement. This is the impressionist way to catch a moment in time, a fleeting event. This is a good example of the Japanese influences picked up by Degas. The horses are in mid stride. He looked at the horses as they moved and noticed that they seem tilted. He depicted the horse in the back in an unusual foreshortened view. The foreground looms toward us and is out of proportion. He uses broad diagonals, radical cropping, and asymmetrical placement of the figures.

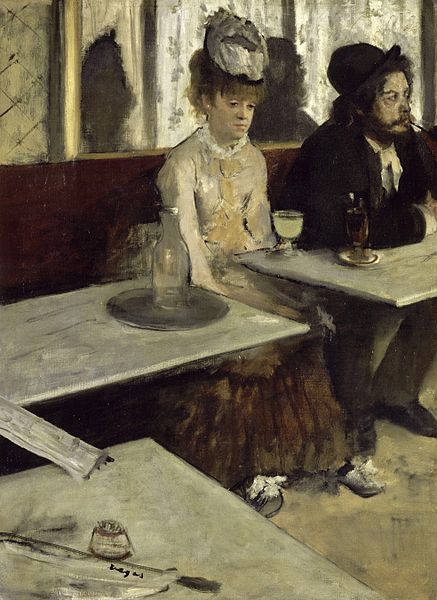

The Absinthe Drinkers, painted in 1876 is very asymmetrical. It was inspired by photography, but is only one segment of the whole scene. The point of linear perspective is out of view. This is a typical modern environment showing two lower class people in a bar, drinking an opium based drink, absinthe. They sit slumped over their drinks, staring into the distance. They have natural gestures which create a psychologically probing moment in their life. We feel their pain more than they do.

Most people know Degas for his many paintings and drawings of dancers, especially ballet dancers. He was a master of movement and speed. He was able to capture the new artificial light of the stage.

Note the unusual angle of the Swaying Dancer. It is as though he was viewing them from a balcony. The artificial light is directional and dramatic, almost like a theatrical illusion. His brushstrokes are loose and un-blended. His dancers are not in beautiful movement, but in awkward, angular poses. Often his main figure is off center and some figures are cropped and you are not able to see them. He uses strong diagonal lines and splashes of bright colors and nearly a quarter of the painting is just the floor.

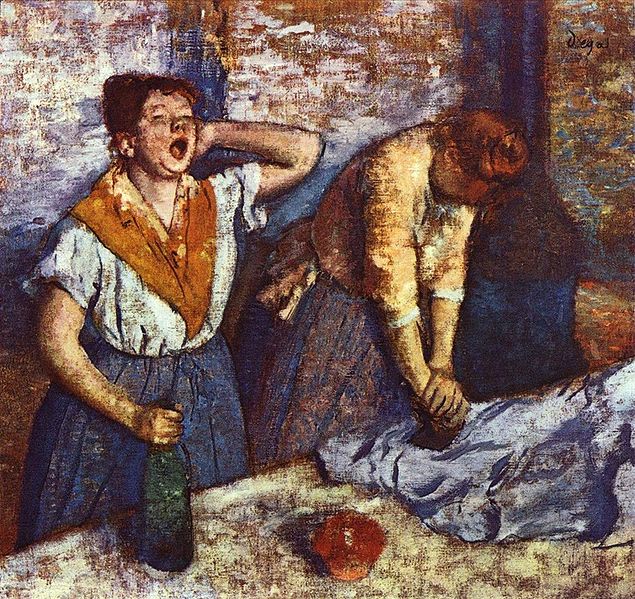

Degas is also known for painting many pictures of women at work, especially women washing or ironing clothes. The women in the version below seem barely able to stay focused on the job and indeed one of them can hardly stay awake.

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)

Not many women were able to join and then maintain their association with the Impressionist movement. Mary Cassatt was one of them. She was the daughter of a wealthy Pittsburgh banker, and had wanted to be a painter from an early age. It was not appropriate for a woman to be a painter at this time and her family made fun of her. Disappointed by the quality of instruction available in the United States, she moved to France where she had spent some of her childhood with her family. She traveled all over Europe and copied the works of the old masters as part of her studies. In 1874 Mary entered one of her works in the Salon of 1874 where Degas saw it and was struck by her work. Three years later he went to her studio and invited her to take part in the Impressionist exhibition of 1879. She was very close to Degas and was one of the only women who could stand his abrasive personality. Degas is said to have stated that it was impossible for a woman to draw well, but she seems to have proved him wrong and became his friend. She never married, but there is no feeling that her paintings of women and children, which dominated her work, were created out of frustration. Instead she seems to have lived a rich and fulfilled life. Mary encouraged American collectors and artists to purchase the Impressionistic works of her friends in Paris. It is because of her influence that Impressionism spread to other parts of the world and became internationally known.

Mary painted murals for the October 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition which exemplified the changes that were occurring in the way women perceived themselves and their art. The central panel, “Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge or Science,” has been said to allude to “women’s recently acquired access to college education.”24 Cassatt said the center panels of this mural also refer to a flying figure who “personifies fame,” a very different image from the prim, coy woman who was idealized in many of the popular publications of the day. “In Cassatt’s view, girls who sought renown could, through education, fulfill their dreams. Such achievements are the subject of the right-hand panel, where three self-confident and adjured women in modern dress represent the artist, musician and dancer. Rather than being the creative muses of men, they are accomplished persons in their own right.”25 This work is no longer in existence and we only know it from the black and white photographs published to inform readers about the Columbian Exposition.