2.3 ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE

ARCHITECTURE

The French Revolution brought major changes to Paris in the early 19th century. As was discussed earlier, the archeological discoveries and the writings of Winckelmann sparked interest in ancient cultures, especially Rome. Rome became the symbol of the new social order. Napoleon Bonaparte patterned his reign after the rule of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar. He rose through the ranks by personal merit rather than inheritance. One of his greatest contributions was to beautify the city of Paris with new architecture and art, and to bring the ancient forms back and make Paris the new Rome.

Napoleon planned to widen streets, add colonnades and create new, spacious public squares. An important form in Rome was the triumphal arch, such as the Arch of Septimus Severus or the Art of Constantine which are both still in existence in Rome. Napoleon’s version was the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, which was built in 1806 by Charles Percier and Pierre-Francois-Leonard Fontaine. It was created to memorialize the victory of Napoleon’s French Imperial Army in Austerlitz. It is sixty five feet high and the bas-relief carvings show Napoleon entering Vienna, the Battle of Austerlitz, the Tilsit Conference, and the surrender of Ulm. It includes statues of soldiers who served with Napoleon. The horses atop it were originally the quadriga, or four bronze horses taken from St. Mark’s cathedral in Venice. However, those horses were later returned to Venice and a copy was made. That copy still sits on top of the arch in Paris.

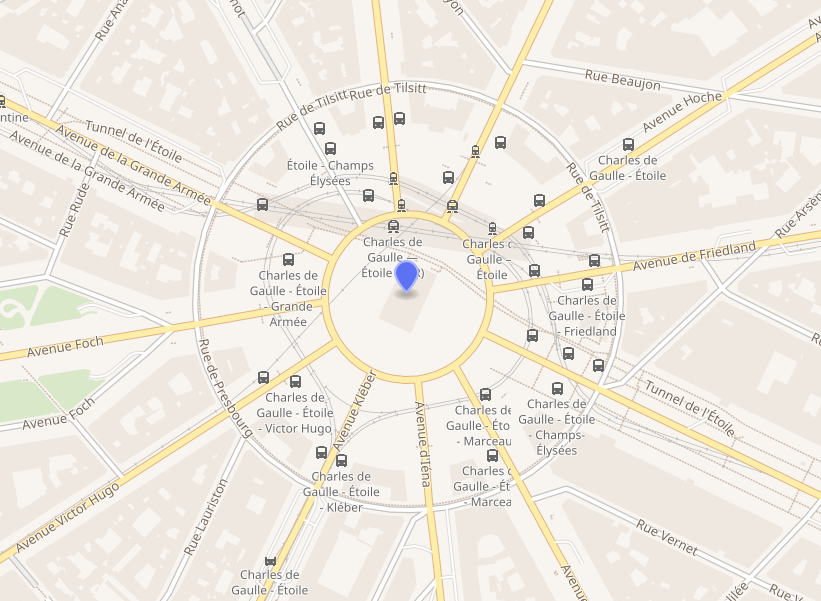

Jean-Francis Chalgrin built what we know as the Arc de Triomphe de l’Etoile beginning in 1806 but it was not inaugurated until 1836 by King Louis Philippe to honor the armies of the Revolution and the Empire. An unknown soldier was buried at its base in 1921, at the end of World War I. It sits in the Place de l’Etoile (place of the Star) at the intersection of twelve avenues.

In 1838 huge reliefs were added by Corot and Rude. These followed the Hellenistic style much like the Altar of Pergamon. “The pedestals were decorated with four allegorical high-reliefs: two facing the Tuileries, ‘The Triumph of Napoleon’ by Cortot and the extraordinary ‘Departure of the Volunteers in 1792’ by Rude; and two Neuilly, works by Etex symbolizing the Resistance and Peace of 1814. Above these reliefs but below the entablature are ‘Marceau’s funeral’, ‘The Battle of Aboukir’, ‘Crossing of the Arcole bridge’ and ‘The Capture of Alexandria’.’4 The large figure charging forward while beckoning those behind her symbolizes the revolution. Her face is contorted in a cry to rally forward to battle.

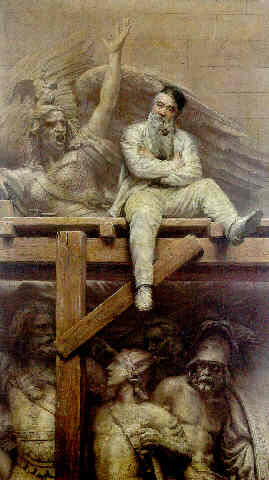

In 1893 Joseph-Noel Sylvestre imagined what Rude would have looked like sitting on the scaffolding while working on the huge work.

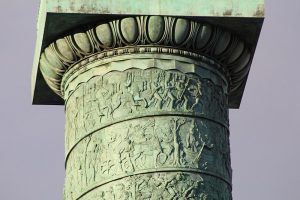

Napoleon also engaged his artists to copy the ancient Roman column of Trajan built to honor the victory of Trajan over the Dacian people. Napoleon’s column is called the Vendome column since it sits in the Place Vendome and was specifically built to be a replica of the one in Rome. It was 138 feet tall and was made of a series of 425 bronze plaques fixed to the stones with pins. The bas-relief, “designed from drawings by Bergeret, winds round the column depicting the major events of the campaign – from the camp in Boulogne to the return of the Emperor and his guard in 1806. A team of sculptors (including Boizot, Bosio, Bartolini, Ramey, Rude, Corbet, Clodion and Ruxthiel) was commissioned to execute the frieze.”8 The bronze came from the guns and cannons captured from the defeated Prussian and Austrian armies, which were melted down and reused. The column was pulled down by an angry mob in 1871 and then rebuilt and erected again in 1874.

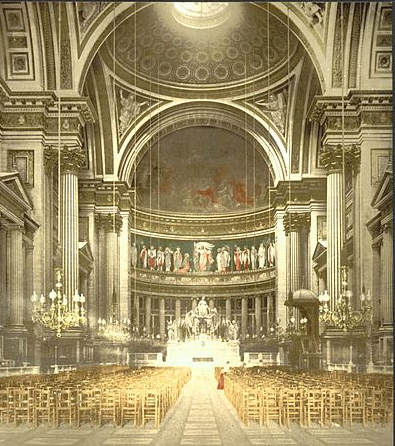

While he was fighting in Poland, Napoleon signed the decree for his temple of glory, La Madeleine. The building was not supposed to look like a church, but was to resemble an ancient classical temple. It was to be presented to the troops with the inscription “From the Emperor to the soldiers of the Great Army.” He chose the architectural plan of Pierre Alexandre Vignon, which was a Greco-Roman Corinthian design. It stands on a podium 23 feet high and is approached by a wide flight of stairs in the front. Running all the way around the building is a Corinthian colonnade 63 feet high, with eighteen columns on each side and eight on each end. An additional row is in the front to support the cornice. Napoleon never had a plan for the interior of the church. It was left dark and empty in the plans. The architect Vignon decided to fill it with a style completely different from the pagan exterior. He converted it to a church before he finished it. The interior is a three domed aisieless nave divided into three long bays. It seems to follow Byzantine ideas with its pendentives and domes. The nave ends in a semicircular apse that is roofed by a semi dome. Chapels are located in the recesses created by the buttresses.

Neo Classical Sculpture

The first Neo-Classical sculptor we will study is Antonio Canova (1757-1822), an Italian sculptor who enjoyed a reputation second to none. He was considered the greatest sculptor of his time. He was born in Italy to a family of stonecutters and began to study sculpture early in his life. He spent much time touring museums and art collections in Italy and was very familiar with the Baroque works that filled them. His early works included funeral monuments, portraits of popes and mythological subjects. He worked for a time at the Vatican and was also summoned from Rome to Paris by Napoleon to create sculptures of the emperor and his family. Even with all of the political upheaval, he was able to continue to work and became very famous. He had a large studio in Rome, which was even visited by tourists who wanted to see him at work. When he died there were memorial services held in his home town of Possagno and in Rome and Venice. “His body was interred in Possagno, his hand preserved in the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, and his heart was placed in a tomb built by neoclassical sculptors based on his design in Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari.”13

Canova’s portrait of Pauline Borghese as Venus was made in 1808. It is a good example of Canova’s skills as a classical sculptor. The body, the drapery, the pose, and the form were all taken from classical sculpture. The galleries Canova visited were filled with examples that he could copy. The head was an idealized portrait. The couch and its drapery, which were copied from a couch that had recently been excavated from the ruins in Pompeii, are portrayed more realistically than the body, which is idealized. Some art historians suggest that Canova was an expert at portraying the art of other sculptors rather than depicting life. He copied other ancient sculpture so faithfully that he lost track of reality.

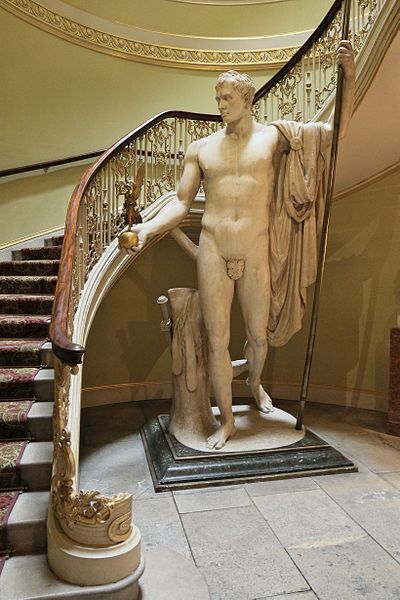

His sculpture of Napoleon shows the emperor in the heroic altogether. Napoleon is reported to have balked at the idea, but Canova insisted. Napoleon has a toga draped over his shoulder and a carefully placed fig leaf, but otherwise he stands like the Apollo Belvedere, which was housed in the Vatican Museums and would have been familiar to Canova. It is known that Canova used chemicals to smooth the surface of his marbles, which some people thought was cheating. It is one reason the surfaces of his work are smooth and shiny.

Jean Antoine Houdin

Jean Antoine Houdin (1741-1829) was the leading sculptor in France in 1784 when the Virginia legislature voted to honor its favorite son, George Washington with a life-sized memorial. Thomas Jefferson suggested that they engage Houdin to do the work especially since he was a man with strong libertarian leanings. In 1785 Houdin and three assistants came to observe Washington in the flesh. Houdin did a life mask and a terra cotta bust before returning to Paris, where he finished the work. The statue was installed in the state capital in Virginia in 1796. The head is one of the finest portraits of Washington, but some think the body is rather stiff.

Notice that Washington is surrounded by a fasces, the symbol of revolution, as well as a cane, a plow, and a sword. At the time of the commission of this work, Washington was not yet president of the United States which would happen in 1789. At least twenty copies have been made of the original marble sculpture, sometimes from casts made of the original. These copies are now installed in cities all over the world. Interestingly, one of the copies of this work is in Trafalgar Square in London, and someone posted the title of the work as “George Washington, sculpture of a traitor”.

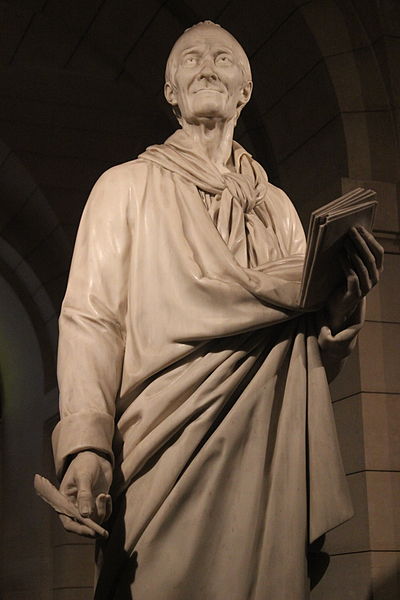

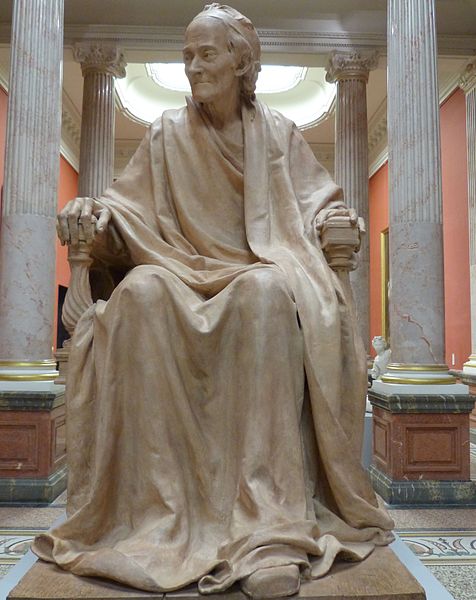

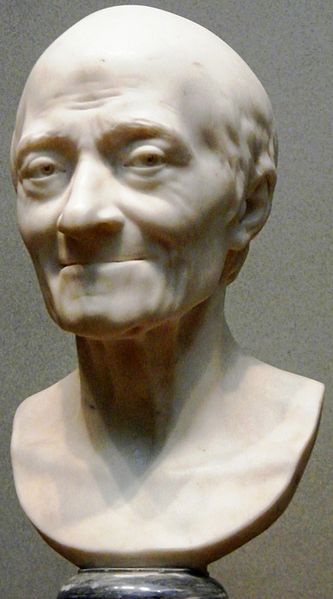

One of the other famous people Houdon memorialized in sculpture was Francois-Marie Arouet, known to us as Voltaire (1694-1778). Voltaire was a prolific playwright, poet, and novelist. He was also a very outspoken critic of the Catholic Church and an advocate of freedom of speech. He wrote novels, plays, histories and thousands of letters and pamphlets. He seems to have made friends and enemies wherever he went. His unhappy relationship with the church caused him to be forever moving from country to country. By 1778 he was eighty-four and had been living in exile in Switzerland. He had returned to Paris to watch an opening performance of his tragedy Irene. Voltaire and Houdon met and Houdon did many drawings and preliminary sketches of the very elderly gentleman. It was these drawings and sketches that Houdon and others in his workshop used to create many versions of Voltaire. Figures 2.33-2.35 are some of the many examples of those works. Even across the years it is easy to see the humorous gleam in Voltaire’s eye.