1.2 NIGERIA, BENIN AND TOGO, THE BINI AND THE YORUBA

The Bini

The Bini, as the people of Benin were called, were Kwa speakers. They had well developed metallurgy and a powerful ruler. A dignified and law-abiding people, the Bini paid obeisance to their king or oba who ruled through a hierarchy of counselors and local leaders. The capital city, also called Benin, was one of the most important commercial and cultural centers of western Africa. They had no written language, so the only detailed descriptions of life are from the journals of early explorers. Much of our understanding of their culture comes from the elaborate bronze plaques which were commissioned by the oba to adorn the exterior of his palace. The oba could have anything he wished, but his time was taken up by many ceremonies and his harem of a hundred or more wives. His counselors conducted the business of state in his name. He was considered god-like and his word was law. Religion revolved around a belief in a supreme god who was not worshipped because he was benevolent. Instead they worshipped many lesser gods who intervened for them. Human sacrifices were made to the devil, whom the Bini blamed for their misfortunes. Hunting was a prestigious profession reserved for the most exceptional young men. A difficult apprenticeship included tracking game, survival for long periods of time in the forest, and memorization of secret rituals which accompanied the mystique of the profession.

The Bini, were also a nation of competent traders. They exchanged ironwork, weapons, farm tools, wood carvings and foodstuffs using a currency of cowry shells or metal rings called manillas. European traders seeking an easy mark were disappointed to find the Bini to be shrewd businessmen. War was a constant way of life in Benin as the oba sought to expand territory and acquire booty and slaves. After the Europeans arrived the slave trade mushroomed. Farming and commerce were slighted and the economy inevitably started to collapse. The oba, believing his bad fortune was the work of the devil, ordered more and more human sacrifices to turn the tide. But by 1897 the disintegration was complete; that year a British force found the city of Benin all but deserted and littered with the bodies of sacrificial victims. Watch this video from Khan Academy about the Benin plaques: Benin Art The British removed most of the art from the court of the oba, took it back to Europe and auctioned it to the highest bidder. Today there is a movement to repatriate the Benin plaques back to Nigeria from Britain and other countries that hold them. Read this article to learn about a new museum being built in Nigeria and the effort to repatriate the art. Repatriating the Art of Benin

The Dogon

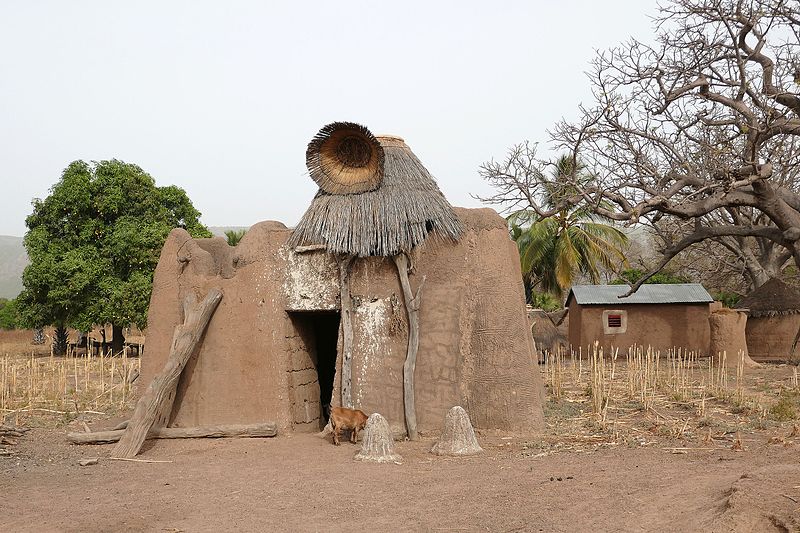

The Dogon live inland in West Africa near the great bend of the river Niger. They settled in cliffs between the 10th and 13th centuries while in flight from Moslem invaders. According to their oral history, they came from the ancient kingdom of Mande, in what was Mali, and were probably freed serfs. They built their villages in the Bandiagara Cliffs which are 100 miles long, crescent shaped, russet colored, and run parallel to the Niger. They build their houses in the cliffs so as not to waste land that could be used for planting crops.

They have no central government but live in patrilineal villages led by a senior male descendant of their common ancestor. The Dogon celebrate a special ceremony every 60 years when the white dwarf star Sirius appears between two mountain peaks. They also believed that the cosmos is “two disks forming the sky and earth connected by a tree. The supporting figures represent the four pairs of nommo twins in their descent from sky to earth. These spiritual beings were involved in the creation of man and culture. The zigzag patterns suggest the path of their descent and flowing water and refer to the symbol of Lébé, the first human and priest who was transformed into a serpent after his death. The dots of red, white and black pigment on the backs of the figures and on the center post are unusual. While Dogon masks have painted designs, figures and stools generally have encrusted or eroded surfaces indicative of ritual use.” 6

The Dogon are mainly an agricultural community. They collect water in a calabash from a well and carry it over long distances. The hoe is their main farming implement. All men and women work the land except for the cobblers and the blacksmiths. They sow millet, rice, and onions and they barter onions for sheep, dried fish, sugar, salt, butter, and red peppers.

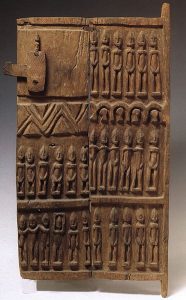

The Dogon village represents human beings. The smithy is at the head of the village like a hearth is the center of a house. The family houses are in the center of the village and the millstones and village altar represent the sexes. The men’s house is near the forge and is called the toguna, where men meet to discuss village affairs. The posts of the toguna and the granary doors and shutters are the only architectural manifestations of the Dogon. The decoration of toguna posts are often women, couples, and birds, which are all linked to fertility. Often there are animals carved on the shutters, posts, and doors of the toguna and the granary that depict the animal that is the symbol of their clan.8 Women are excluded from public life and are considered property of the husband’s family. However, a woman cannot be forced into marriage and may leave if her husband mistreats her. Women have some financial independence, whatever they grow or make on their own they can sell and keep the money. The Dogon are a very close knit society. Every person has a place and a strong sense of belonging. A detailed set of rules governs all aspects of daily life. Land belongs to the community and cannot be sold or given away. Murder is not considered productive for the society as a whole, so it is not a problem. The men and women have separate houses.

Dogon masks, such as these are “worn primarily at dama, a collective funerary rite for Dogon men. The ritual’s goal is to ensure the safe passage of the spirits of the deceased to the world of the ancestors. The ceremony is organized by members of Awa, a male initiation society with ritual and political rolls within Dogon society. These wooden masks depict the face as a rectangular box with deeply hollowed channels for the eyes. The superstructure above the face identifies this mask as a kanaga: a double-barred cross with short vertical elements projecting from the ends of the horizontal bars. This abstract form has been interpreted on two levels: literally, as a representation of a bird, and, on a more esoteric level, as a symbol of the creative force of god and the arrangement of the universe. In the latter interpretation, the upper crossbar represents the sky and the lower one, the earth.”12

The Yoruba

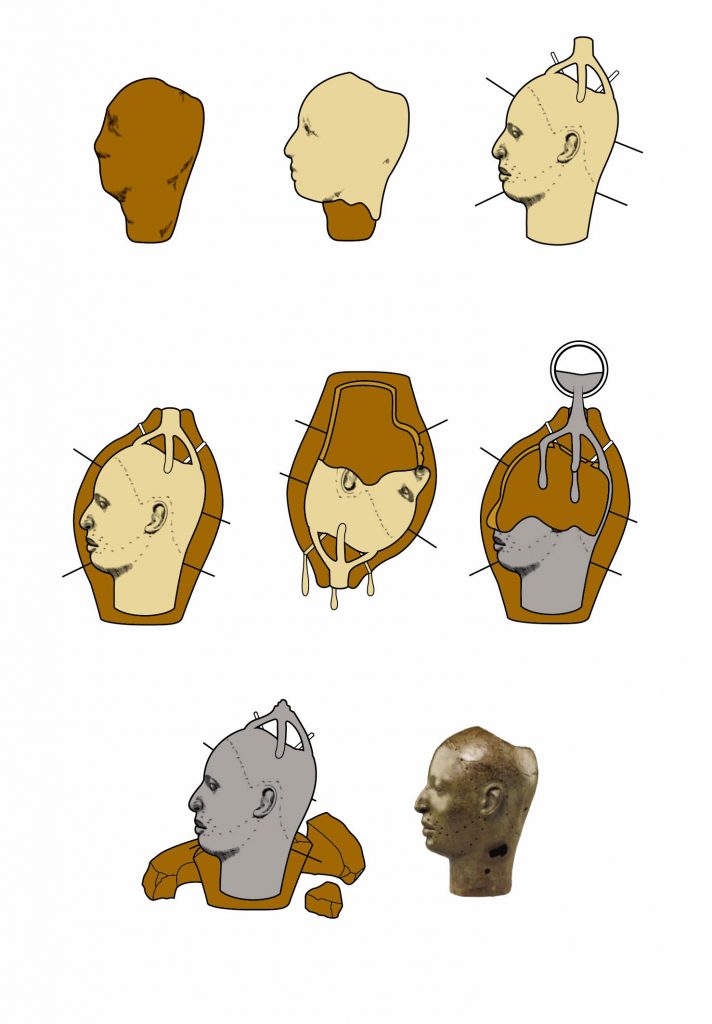

Another of the ethnic groups still living in Nigeria are the Yoruba people. Some lived in Benin and northern Togo. Most Yoruba men are farmers, growing yams, corn (maize), and millet as staples and plantains, peanuts (groundnuts), beans, and peas as subsidiary crops; cocoa is a major cash crop. Others are traders or craftsmen. Women do little farm work but control much of the complex market system—their status depends more on their own position in the marketplace than on their husbands’ status. The Yoruba have traditionally been among the most skilled and productive craftsmen of Africa. They worked at such trades as blacksmithing, weaving, leatherworking, glassmaking, and ivory and wood carving. Yoruba women engage in cotton spinning, basketry, and dyeing. In the 13th and 14th centuries Yoruba bronze casting using the lost-wax (cire perdue) method reached a peak of technical excellence never subsequently equaled in western Africa. This is an explanation of the lost-wax method that was used to create their sculpture.

The Yoruba also carved wood sculpture and masks as did their neighbors. One interesting type of sculpture was their focus on twins. “The Yoruba are known to have one of the highest rates of twins in the world, 45 to 50 per 1,000 births. Twins are revered among the Yoruba and come into this world with the protection of the orisha (deity) Shango who is evoked at the baby’s naming ceremony when he or she is a few months old. Due to the low birth weight of twins and the high infant mortality rates in Nigeria, many twin babies do not live long. If a baby dies during childbirth, or in the months leading up to the naming ceremony, the parents will seek consultation with an Ifá diviner, a Babalawo. If the Babalawo ascertains a spiritual cause, he will help the parents find a carver to create an Ere ibeji figure. An Ere ibeji is a wooden carving of a male or female figure once used by the Yoruba. The figure is thought to be a focal point for the spiritual energy of the deceased twin who, according to Yoruba traditional thought, resides in the supernatural realm where he/she is cared for by a spiritual mother.”14 There are many examples of Ere ibeji sculptures. Today mothers might rely on purchased dolls to accomplish the same thing. Sometimes a small cloth case or sack was made to carry the sculpture from place to place.

One of the main cities controlled by the Yoruba people is the sacred city of Ile-Ife. It is on the crossroads of major trade routes and is considered the seat of the birth of the Yoruba people. Their creation myth tells the story of the birth of humankind in this area. Their gods are in human form and, just like the gods of the Greeks; they were imperfect and experienced human emotions such as love, fear and anger. This is one telling of the Yoruba creation myth:

Characters

Olorun: Ruler of the sky; creator of the sun.

Olokun: Ruler of the sea.

Obatala: Creator of humans and land on Earth (Olorun’s “favorite”).

Orunmila: Prophet God; oldest son of Olorun.

Eshu: Messenger God.

Summary

In the beginning, the universe consisted only of the sky, the water, and the wild marshlands. The God Obatala believe that the world needed more–so he goes to Olorun, ruler of the sky and creator of the sun, asking for permission to create mountains, valleys, forests, and fields. Olorun grants Obatala permission to create solid land on Earth.

Obatala goes to Orunmila, the God of Prophecy. Orunmila tells Obatala that he will need a gold chain to reach from the sky to the waters below. Obatala goes to the goldsmith, who agrees to build the chain, if Obatala brings him the gold. Obatala goes to every god, asking for gold. When the chain in complete, Obatala descends onto Earth, carrying a snail shell filled with sand, a white hen, a black cat, and a palm nut. When Obatala climbs down, he realizes that the chain is not long enough. Orunmila calls out to Obatala, and tells him to dump the sand onto the Earth and drop the hen. The hen scratches at the sand, spreading it around and forming the first solid land on Earth.

Obatala lets go of the chain and falls to earth, naming the place where he landed “Ife.” He plants the palm nut, which immediately sprouts into a palm tree. Obatala keeps the cat for company. Although Obatala keeps the cat, he still becomes lonely. He begins to make clay figures in the likeness of himself. Obatala grows tired while assembling the clay figures, and decides that he needs some wine to drink. He makes wine from the juice of the palm tree, and he becomes drunk. He continues to make clay figures in his drunkenness, and the figures become deformed. Olorun breathes life into Obatala’s figures, and they become human beings. Obatala realizes that his drunkenness has resulted in deformity, and he vows to be the protector of all who are born deformed. The humans created by Obatala come together to form the first Yoruba Village in Ife. Obatala returns to the sky–thereafter, he splits his time between Ife and his home in the sky.

Obatala’s kingdom of Ife was created without Olokun’s permission. As such, Olokun becomes very angry. She sends a great flood to destroy Obatala’s kingdom. The flood destroys most of Obatala’s kingdom. The remaining people send Eshu, the messenger god, to Olorun and Obatala, asking for help. Orunmila goes to Earth, causing the waters to retreat.

Olokun challenges Olorun to a weaving contest. Knowing that he cannot beat Olokun, Olorun devises a plan to accept the challenge, without actually participating. He sends a chameleon to judge Olokun’s skill; every time Olokun weaves a new cloth, the chameleon mimics the fabric. Olokun accepts her defeat.

Interpretation

“The Creation of the Universe and Ife” is an example of a creation myth; as it provides an explanation for the origins of land and life on earth. The myth offers an explanation for humanity’s imperfections: Obatala becomes drunk while he is creating humanity. As such, Obatala’s shortcomings become humanity’s shortcomings. The story also displays characteristics of a flood myth. Olokun sends a great flood that destroys almost all of humanity. The myth’s events are set in motion following the delivery of a prophecy.16

The sculpted head in figure 1.26, found at Wunmonije Compound, Ife, was taken out of the country and given/sold to the British Museum in 1939. When it was first discovered Europeans did not want to believe that African cultures had developed metal works and such a sophisticated artistic tradition. Early experts who wrote about this sculpture suggested that the work was cast by a colony of ancient Greeks or belonged to the lost city of Atlantis. This work and others like it eventually changed the way Europeans thought of the people of Africa.