3.2 ROMANTIC PAINTING

- Emphasis on personal feelings and their expression

- Emphasis on emotion rather than intellect

- The identity of reality is rooted in the self, not in the external, man-made world

- Love of the fantastic and the exotic

- Mystical attachment to the world of nature

Francisco Goya (1746-1828)

Francisco Goya did not found a school or teach students. He acknowledged that he took inspiration from Rembrandt, Velazquez and “nature”. Goya was born into a middle class family in the Aragon region of Spain and attended a poor Spanish school where he barely learned to read and write. His spelling, penmanship and verbal expression remained coarse throughout his life. He attended a “college” where he learned the principles of draftsmanship, principally by the traditional methods of copying etchings and engravings. At the age of seventeen he went to Madrid, the center of artistic patronage in Spain. There he became a painter to the court and the aristocracy. He was a man of many talents: he did etching, lithography, painted cartoons for tapestries, painted portraits, and worked in fresco. He was married to Josefa Bayeau, the sister of a prominent painter with whom he served as an assistant. They were married for 39 years and had a series of pregnancies and miscarriages. Only one child lived to adulthood.

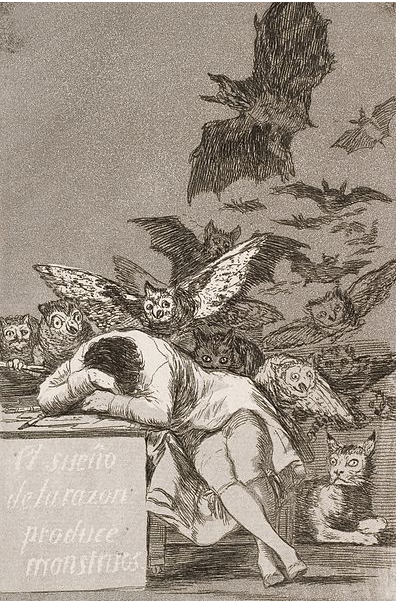

Much of Goya’s work was dark and pessimistic, and some might say that these thoughts came from the difficulties in his own life. In 1793 Goya had some type of illness which left him deaf. From a series of prints called “The Caprices” we see The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. Its title is written on the desk below the student who sleeps with his head on his books. The theme was, “When man allows reason to sleep, the creatures of the irrational world control his life; only with the awakening of reason will these hobgoblins finally disappear. In this series Goya is exploring Spanish nobility and the inept way they rule the people. With this series he took etching and social comment to new heights.

As a painter in the Spanish court, one of his duties was to paint portraits of the royal family. In 1801 he painted the “Family of Charles IV”. It was probably inspired by Velazquez’s work “Las Meninas”. Note the self portrait of the painter at the left in the shadow. Goya sketched some of the members of the family individually and a few group poses, and finished it within a year. Their clothes glitter with the wealth and ostentation of their rank. Goya presents, with a straight face, a menagerie of human grotesques, who critics believe probably didn’t know they were being ridiculed. “The superb revelation of stupidity, pomposity, and vulgarity, led a later critic to summarize the subject as the ‘grocer and his family who have just won the big lottery prize.”2

The queen was probably quite as ugly as she appears, but that is not what makes this work interesting. It is Goya’s interpretation of her ugliness and his disgust with it that makes this work Romantic. The queen often made light of her ugliness, perhaps so people would disagree with her. Her double chin, thick neck, and vulgar smile are not hidden. Goya did not cheat and make her look beautiful. In this family, the queen made the major decisions, and she is the focal point of the painting, while the king stands by her side, as he did in life. Beside her a princess stands almost angelic, reflecting Goya’s affinity for children. The haughty man in blue is the king’s eldest son, to become Ferdinand VII. Beside him, with her face turned away is his bride-to-be, who had not yet been officially affianced.

In 1807 Napoleon brought his armies into Spain, and Goya watched those events as they unfolded. In response to a rebellion in Madrid, Napoleon ordered his troops to round up a suitable number of random people from the city and shoot them. The Third of May, 1809 is Goya’s telling of that execution. Notice some of the symbolism: the lantern that was supposed to represent the Enlightenment, the Christian symbols of the tonsured monk, the outlined church in the darkness on the skyline, and the figure looking much like Christ with his outstretched arms and stigmata on his hand. Remember that this is the Romantic period and we are seeing the artists’ emotions about the event, rather than a real image of the event. Watch the analysis of this painting by at Smart History for more information about it. The Third of May 1809.

Goya also seemed to focus much of his work on pain, suffering, mental illness and the ill fate of others. The Madhouse, painted in 1812-19 is another example of this tendency. During the Enlightenment people with mental illness were not treated well. Often they were handcuffed, left in large rooms with little to eat, no medical treatment, and nothing to do. It was popular amusement for the gentry to visit asylums and enjoy the peculiar behavior of the inmates. There are many paintings and drawings of the subject by various artists. Goya had experienced mental illness in his family and nearly became mentally ill during his own bouts with poor health, so he was aware of the problems. These unfortunates are being kept in a dark room with only a tiny barred window for light as they act out their fantasies and day by day.

The work Satan Devouring his Son was painted by Goya between 1819 and 1823 as a fresco on the walls of his home on the outskirts of Madrid during a dark period of his life. It is from a series called the Black Paintings in which he used dark themes and vivid colors. These are creatures of his imagination, creatures from his nightmares. They were not commissioned by a patron, but were painted by him just because he wanted to. They were not intended to be seen outside of the “House of the Deaf Man” as he called his home. They expose his intense awareness if the dark forces of panic, fear, and hysteria. In 1874 an admirer saw them and, wanting to preserve them, had the frescos transferred from the walls of Goya’s house to canvas.

Watch Smart History – Goya Devouring His Son 3:25

If you cannot view the video above, use this link https://smarthistory.org/goya-saturn-devouring-one-of-his-sons/

Baron Antoine Jean Gros (1771-1835)

Another Romantic painter contemporary to Goya was Baron Antoine Jean Gros (1771-1835). He was a pupil of David and the official painter to Napoleon. Gros is most known for his paintings of Napoleon’s military campaigns, and since they occurred in faraway lands, they would of course lend themselves to exotic scenes. Bonaparte, not yet emperor and at the end of the disastrous Egyptian campaign, has retreated up the coast of Palestine. His army is stricken with the bubonic plague, and he is shown visiting his sick and dying men at the hospital in the ancient city of Jaffa. Behind him is the flag of the revolution waving proudly. It is set in an arcade of Moorish arches, with the exotic landscape in the background and the turbaned Moslem physician and his assistants accompanying him on his visit. Even though Gros depicts him as a near heroic figure, Napoleon was known to kill the troops he could not feed and poison those dying of the plague when he left Jaffa. Gros uses the familiar Romantic themes: the heroism of Napoleon, the lure of distant places, patriotism, and yet he also gives the viewer the ugliness and even the stench of the plague. This is a piece of propaganda intended to make Napoleon look good by using Christian iconography.

Another Napoleonic military work by Gros is Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau painted in 1808. This was a bloody battle with terrible loss of life, almost 50,000 casualties. After the battle there was a competition announced in the newspapers to choose the artist who would paint the picture exactly as requested. There were detailed lists of what the background was to look like, how many figures were to be shown, what they were to be wearing, and all details of the event. Gros submitted a sketch along with twenty six other artists, and he was chosen to do the painting. The work shows Napoleon on a dark snowy battlefield with frozen corpses littering the battlefield. This was truly a work of propaganda, intended to show the people of France how their leader was loved and respected, even by the enemies he had conquered. Surrounded by his officers, Napoleon sits astride his prancing horse with the ravaged army under his feet and the burning countryside behind him.

Theodore Gericault (1791-1824)

Theodore Gericault was born in Rouen, France to wealthy property owners. His father did not want him to study art, but his mother and his uncle secretly arranged for him to enter the studio of Carle Vernet. It was here that Gericault learned to love the military and its horses. He watched the rise and fall of Napoleon and the tumultuous events of the time. Even though he purchased a substitute to go into the military for him he eventually joined the Paris National Guard. As the political events swirled around him, Gericault alternately hid and resurfaced, depending on who was in control.

In 1819 Gericault produced a huge painting based on the story of the sinking of the naval ship Medusa, a scandal that had been discussed in the papers in the last few years. The Medusa had been on its way to Senegal with government officials to take possession of the colony and to support the illegal slave trade that was still happening there. When the ship foundered off the coast of Africa the high ranking officials were put into six life boats and the rest of the lower classes were put on a raft 65×23 feet, which was lashed to the boats. Eventually the raft was cut loose and left to drift. Of the 150 unfortunates on the raft, only 15 were rescued and only ten of them survived to tell the story of cannibalism and mayhem. Gericault interviewed the survivors, read the accounts of the event, studied a small replica of the raft given to him by the ship’s carpenter who had built it, and drew the events of the story. When he finally began working on the canvas, Gericault chose the most dramatic moment when the survivors see the sails of the distant ship which eventually rescued them. He relied upon his past studies of Renaissance sculpture by Michelangelo and the paintings of Rubens for some of the figures. Notice the pyramidal shape of the mass of survivors, with a single man at the apex waving at the distant ship. This is a powerful use of light and dark, much like Michelangelo’s Last Judgment on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Gericault also used shock tactics to portray a contemporary event on a large canvas. This is the Romantic instinct for the sublime and the terrible. It was an attempt to stun the viewer’s sensibilities. Like a reporter he was out to show the facts, but also to touch on the macabre. His humans are powerless against the forces of nature. This work deals less with heroism and more with the simple will to survive.

The Charging Chasseur, otherwise called The Mounted Officer of the Imperial Guard was painted in 1812 and is the Romantic epitome of fierce power. This was still the era of the Napoleonic wars with its thunder and canon and cavalry. Here Gericault depicts the military themes of war: splendor, glamour, pomp, valor and terror. Paintings of the time celebrated war’s excitement rather than its horror. Gericault makes the officer seem to be part of the horse. Together the beast and the man are placed in exaggerated, violent pose which creates the illusion of explosive action. Notice the use of the diagonal line in the posture of the horse, the man, and even the clouds above. His use of color and the open nature of the work recall the paintings of Rubens.

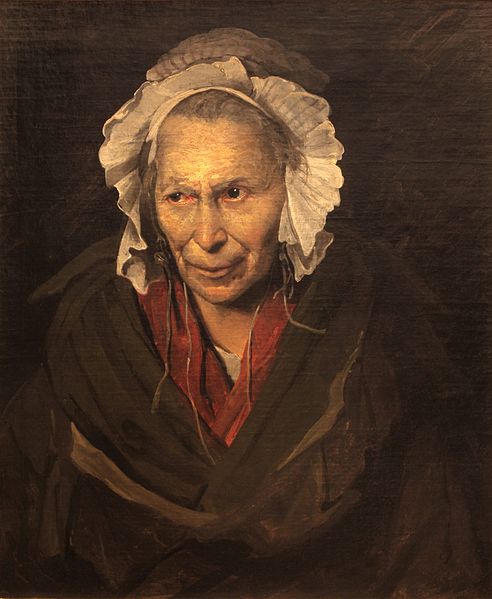

The Mad Woman is another example of the interest in the mentally ill, the irregular, and the abandoned. Gericault believed that a man’s face accurately reveals his character, especially in madness and at the moment of death. He made studies of inmates of hospitals and institutions for the criminally insane. He even spent some time as a patient in such places. He also studied the severed heads of guillotine victims. Notice that her eyes are red rimmed and she leers with paranoid hatred.

Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863)

Eugene Delacroix was a friend and a follower of Theodore Gericault. Delacroix looked to the literary world for inspiration. For him, color was more important than design, and he used color to dramatize and heighten the emotion. He believed that gray was the enemy of all painting and the more there was opposition between colors, the greater the brilliance of the work. He also looked to the past to the works of Rubens and Rembrandt. His art was built on the principles of color, light, and emotion rather than line, drawing and form.

Dante and Virgil in Hell is taken from a scene in the play Faust by Goethe. This is the scene from the Inferno section, the demonic, macabre as well as the tortures of the damned amid hellfire and brimstone. Virgil, in the crimson robe of a medieval Florentine, stands with dignified monumentality, classically calm. On his left is Dante with a bright red hood. He is mortal and suffers from mortal emotions. He looks with terror at the swirling bodies around him. The damned try to attach themselves to the boat, and distress and despair are everywhere. They cross the River Styx to the flaming shores of the City Dis. This work was not well received, but it brought Delacroix to the attention of the critics.

The Death of Sardanapalus expresses a thrilling story intended to stir and electrify the viewer. His art exemplifies the view that the power of imagination, nourished and continually kindled by great literature, art and music, will catch and inflame the imagination of the observer. This work is a grand opera on a canvas. It was inspired by Lord Byron’s poem Sardanapalus, which is about the defeat of the ancient Assyrian king by the conquering Medes. Hearing of the defeat of his armies and the enemies’ entry into his city, the king orders all of his most precious possessions, including his women, slaves, horses, and treasures, destroyed in his sight while he watches gloomily from his funeral pyre, soon to be set alight. The king, at the center of a hurricane of emotion, presides over the horror. These women are like those painted by Rubens: rich in color with many contrasts of light and dark. The brushstrokes are active and almost violent. There is no attempt to be historically accurate, but instead it focuses on the imagined violence and cruelty.

One of Delacroix’s most famous works is Liberty Leading the People, painted in 1830. This was painted after the Parisian revolution which overthrew the restored Bourbons and placed Louis Philippe on the throne of France. In this painting there is no attempt to recreate a real scene from the battle. Instead it is an allegory of revolution. Liberty, a partially nude woman reminiscent of a Greek goddess, represents the noble ideals of the revolutionary era. She carries the tri-color flag of the French Revolution as she waves the people forward to the street barricade. The flag is cut off, as if Liberty was just moved up in the picture and thrust it out of our view. She carries a musket with a bayonet and wears the cap of liberty. She strides forward over the dead and dying of the people and the royal troops they fought against. The bold citizens of Paris follow her into the battle: the street boy carries pistols, a menacing proletariat carries a cutlass and is ready to strike, and an intellectual dandy in a plug hat carries a sawed off musket. The towers of Notre Dame rise in the background through the smoke and clamor, a tiny tri-color flag flying above it. The clutter of bodies in the foreground forms a triangular base to support the pyramidal figures in the central ground. Light flashes from the firing of guns, mingling light and dark. This was shown for the Salon of 1831 and received varied reactions. It was purchased by the government for 3,000 francs and hung in the palace to remind the new king how he got to power. He didn’t like it much and had it taken down.

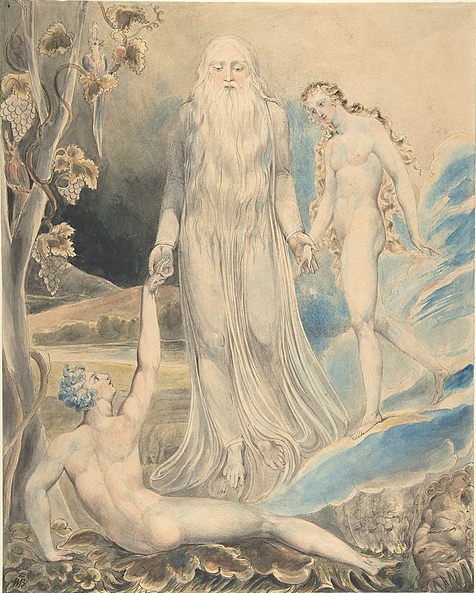

We discussed William Blake in the last chapter and mentioned some of his illustrated poetry. Remember that he believed in visions, especially what was in the Bible. He believed that the prophets knew everything and all others were imitators. He looked back at the Middle Ages for inspiration and was against religion, the rules, and marriage. Many of his prints and paintings illustrated Milton, Shakespeare, and Dante. He disliked the broken color of Rubens and wanted his color to be clear and concise. He believed that the artist should use inspiration rather than relying on the five senses. Many of his characters had the musculature of Michelangelo’s sculpture.

Blake believed in the premortal union of Adam and Eve and between man and God. He believed that man fell from his infinite relationship with God to mortality. Children are pure and unsullied by the things of the world but the perfect thoughts and ideas which existed before life began have been suppressed by reason and crushed by education and the impositions of rules and conventions.

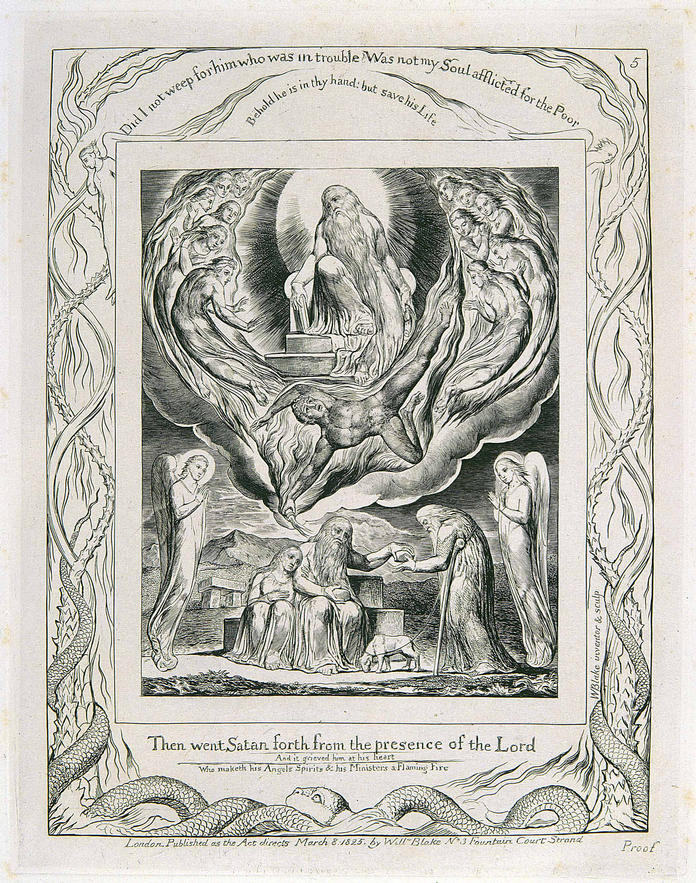

The Romantics, including Blake, believed that Job was the perfect and upright man who erred by following the Mosaic Law literally, but without feeling or passion. Blake rejected the self-righteousness of organized religion with its denial of the imagination and the joys of the body.

John Constable (1776-1837)

We have been looking at some brilliant, but tortured artists. John Constable is a different type of artist. He was the son of a wealthy miller, so he did not have to sell his art to make money. At first he painted portraits, but soon his beliefs as a pantheist came to light in his art. He felt an appreciation and love for even the uneventful, and began painting landscapes. He turned to the writings of Rousseau who advocated that we go “back to nature.” He taught that the charm of the noble savage came as he shunned society and big cities and communed with nature. This type of art was especially popular with the city dweller who dreamed of the idyllic country life. They hung landscapes on their walls and read poetry full of nature’s imagery. He often used studies of clouds, sky, water, and mossy rocks, and hung them in his studio to be used in his larger paintings. At this time meteorologist Luke Howard was investigating and classifying different cloud types, which was interesting to Constable.

His work The Hay Wain was painted in 1821, shown in the Salon of 1824, and won. It is a placid, untroubled view of the English countryside. A farmer encourages his three horses to pull a cart across a stream near a mill that was owned by Constable’s father. In his works nature includes the man, his dog, the cottage, the stream, the park, and the clouds. There is a oneness with nature sought by the Romantics. Man is not an observer, but a part of nature. He uses tiny dabs of local color stippled with white to give it a shimmering surface. He said that he sought light dews, breezes, bloom and freshness. Constable believed that landscape must be based on observable facts. He did not rely on scientific accuracy alone, but he accepted natural phenomena rather than symbolic representation. He was most concerned with intangible qualities in nature such as the conditions of light, atmosphere and sky, more than with the concrete details of the scene.

Another, similar work is Stratford Mill, also by Constable. Here children play, fishermen quietly go about their trade, and the water spills from the mill wheel into the quiet stream. All is calm and right with the world. Note how the sky is almost one third of the painting. He sought to capture the unpredictable and fleeting changes of the atmosphere. He painted the varied intensities of light on clear, showery, or foggy days; sunshine filtered through translucent green leaves and the river captures the reflections of light and clouds from the sky overhead.

Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Grounds. Even though the focus of this work is the cathedral, notice how it is dwarfed by the trees and the clouds and the park in the foreground. The sky, to him, was of key importance. The man made cathedral seems to also be part of nature and nearly melts into the clouds.

Constable’s watercolor of Stonehenge almost seems unfinished. This work is mystical and romantic, to match the mystery of the site itself. The sky is ominous and cold blue. He has used lead white paint alone on the canvas to indicate the brilliance of light reflecting from the clouds. Constable allowed his personal childhood memories to inspire his later works. He believed in the innocence of childhood. He was committed to realism by using light, the time of day, and genre scenes with people who could be real. He believed that God is present in everything: pantheism. His ideas and works mirror these words written by William Wordsworth:

Ode: Imitations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood– 1807

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old. Or let me die!

The child is father of the Man;

And I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety.22

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851)

J.M.W. Turner, as he was known in his art world, was a child prodigy. He was admitted to the Royal Academy as a landscape artist at the age of fourteen. He had a fascination with the powerful forces of the elements. His works exhibit dynamic lighting, vigorous brushstrokes, and color that expresses emotion.

In 1843 Turner read about an epidemic on a slave ship. The captain jettisoned his human cargo because he was insured against the loss of slaves at sea, but not insured against their death by disease.

Are the dead and dying to be tossed overboard to lighten the load before the coming storm? Is the coming storm God’s retribution for the captain’s action? A cosmic catastrophe seems about to engulf everything, not merely the guilty captain, but the sea and the creatures in it. Notice the sharks waiting in the water, a common sight around slave ships. Turner has transformed the tranquil landscape into a blazing sea of color. He releases color from simply defining outlines to express its nature as well as the painter’s emotion. Color and feeling are inseparably joined. The artist begins to produce art that could dispense with shape and form altogether, and rely on color and brushstroke to convey its meaning.

Turner’s Light and Colour: Morning After the Deluge is his version of the Biblical story of the deluge. It was also a study of Goethe’s color theory. His color study stated that minus colors such as greens, blues and purples create tension and anxiety. Plus colors such as reds, oranges, and yellows are warm, and create gaiety and lack of tension. Notice the human figures swirling in the waters and Moses, who is writing the story, sitting in the central area above.

In Rain, Steam and Speed, The Great Western Railroad the main line is a diagonal one which creates motion and causes the eye to move into the distance. Rain is pervasive as the Edinburgh Express crosses a bridge in a driving rain storm. The rabbit racing ahead of the train symbolizes both the speed and the Romantic’s vision of modern technology as a threat to nature and the organic fundamentals of life. The engine’s firebox glows red-hot in the mist. Turner is one of the most daring colorists in the history of painting.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)

Caspar David Friedrich was a German topographical draftsman, a student of nature, and a pantheist. He suffered an ice skating accident when he was young and was saved by his brother, but his brother died in the attempt. This tainted his life. His landscapes were religiously motivated. Nature was used to convey thought and emotion. He knew and believed the teachings of Kant: our experience comes through our organization of the things we see. Each person’s of life is different because we are different. For instance there is no single reality of “chair” because we each think of something different when we think of the word chair.

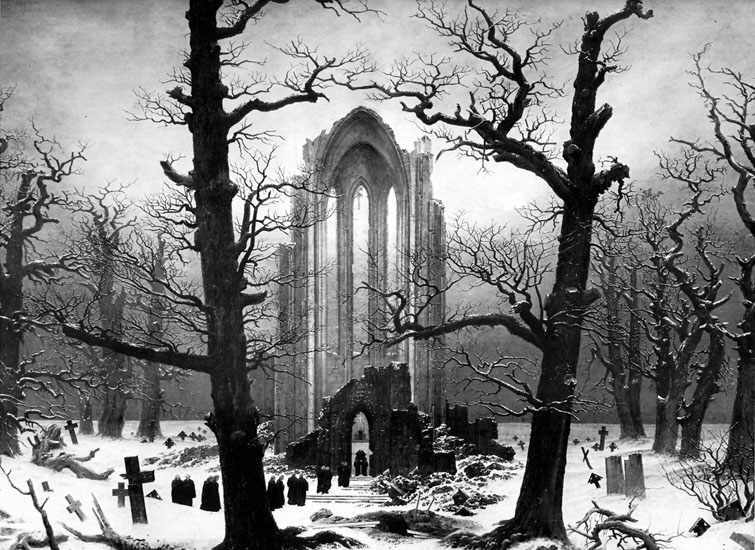

The Abby Graveyard Under Snow is a fantasy depicting the ruin of a monastery that has long been deserted. He creates the mood with symbolic images: the medieval vaults represent the Christian age now in the distant past when faith and religion were important; the tombstones are covered by snow and are long forgotten, and signify man’s final reconciliation with nature; bare, dark, and even ominous trees shelter and screen the church. He poses the question “if man is against nature, who won?”

Friedrich believed that the contemplation of nature gives us self knowledge and leads us to the ultimate self knowledge and the ultimate reality. We can find moral regeneration in nature. Nature and God are infinite and immeasurable. He did not paint actual, real landscapes, but combined several ideas and things together. He believed in the overthrow of established religion and the rise of personal religious ethics based on nature.

The Cross and Cathedral in the Mountain is a symmetrical, silent, mystical symbol. Is this an actual place, or does it symbolize Golgotha where Christ was crucified? The landscape is a composite of what he sees and what he feels. The sunset symbolizes the end of the pagan world. The cross is firmly rooted in the ground, as Christianity is firmly rooted in his culture. The trees represent evergreen faith. The drama of the moment is heightened by the bold, clear forms. He painted many “cross” paintings to convey the presence of God in nature. He also sees the emptiness of space and the yearning to embrace eternity. Man is small when confronted with nature around him.

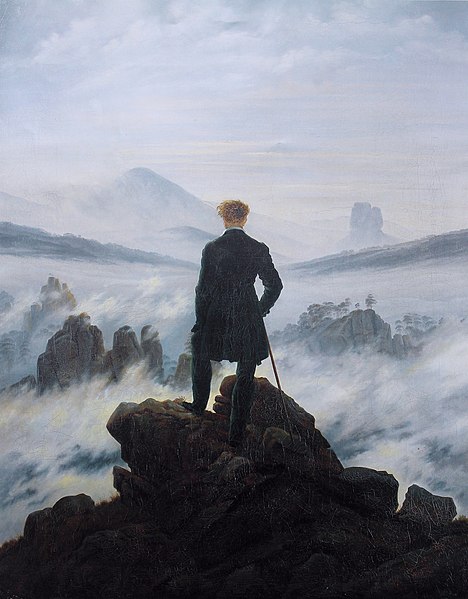

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, painted in 1817, is a dramatic moment when man contemplates the swirling mists below him. He surveys the wide expanse of nature below and his own insignificance. Space is empty and God is in control. The man has his back to us, beckoning us to look past him out into nature and see what he sees. Notice how Friedrich has positioned the man exactly at the center of two diagonal lines and at the top of a pyramid of rocks.

The Wreck of the Hope was painted in 1822 and was probably based on a dangerous moment in William Perry’s expedition of 1819-20 when he went to look for a route to Asia through the North Pole. This is another work where Friedrich uses diagonal lines to cause movement and the draw the eye up to the bleak sunlight peaking through the clouds. The ship’s mast is barely seen in the jagged pile of broken ice.