4.1 INTRODUCTION

The late 19th century was a continued time of upheaval and revolution, with only a few islands of stability in Europe. From 1830 to 1848 Louis Philip was the constitutional king of France but in 1848 the February Revolution overthrew him and created the second French Republic. In fact there were six changes of government in France between 1789 and 1852. Victoria was the Queen of England from 1837 to 1901, creating a more stable government there. In 1853 Admiral Perry opened Japan to western trade and intervention. In 1886 the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in the United States. There was a new broadened sense of history and looking to the past. New democratic ideas grew up all over Europe. Italy united between 1860 and 1870. Germany united in 1866. Canada was granted dominion status in 1867. In short, the world as we know it now began to form politically, scientifically and economically.

Industry grew and new inventions became available, often creating cheap prices for the consumer. The Industrial Revolution created major changes in society, art, and family life. Factories grew and machine manufacturing increased dramatically. Wage earning was no longer based on self-sustained, land based farming but changed to time based wage earning. People moved from the country to the city and learned to exchange time and labor for goods. Workers began to expect to share in the profits of the Industrial Revolution. Infant mortality was reduced and life expectancy increased. Standards of living improved, causing the population to soar. This caused extreme shortages in food and housing and crowding in the cities.

Science was less controlled by the church and scientific positivism became popular. This meant that only scientifically verified facts were considered “real” and the scientific method was the only legitimate means of gaining knowledge. Religion, revelation, intuition and imagination were thought to produce only illusions. Science became the most prestigious of all 19th century enterprises. Scientists were revealing more about the how the nature and the world worked in the past and the present. There seemed no limits to what could be learned. Meteorologists studied clouds and geologists studied sedimentation layers in the earth. New theories suggested that the earth was much older than had ever been imagined. In 1859 Darwin published his theory of evolution.

These changes also affected the artist too. Improvements in the printing press allowed low cost reproductions, making posters and prints accessible to all classes. Synthetic dyes and pigments became available. Low cost reproductions flooded the market. The mass media grew and newspapers, sheet music and novels were available cheaply. Cast iron technology allowed rapid construction of complicated devices and decorations which could now be made inexpensively. Artists began to seek a truthful, objective and impartial representation of the real world, based on miraculous observation of contemporary life. In 1839 the process of photography was published by Daguerre and in 1860 the first speech was transmitted by telephone by Alexander Graham Bell. In 1896 the first moving picture (vitascope) was shown on Broadway.

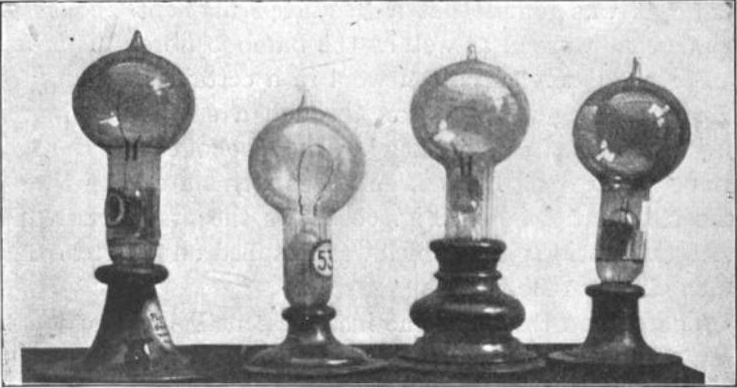

Artists learned to cope with events and ideas unique to what is commonly called “The Gilded Age.” This meant confronting the unexpected at every turn. The familiar components of everyday life were changing at a quickening pace. Edison’s new electric light bulb transformed every aspect of the world it lit, and his phonograph filled the air with music. The streetcar at first startled and then replaced the horses carrying humans and their baggage. The typewriter, mass circulation newspapers, and magazines gave artists a venue to publish their works, but it also enabled art critics to publish their thoughts in magazines and newspapers and write reviews of exhibitions. Articles in the newspaper became the authority on what was good and not so good in the art world.

All of these new inventions caused the artist to look for what was real and immediate. This led to a new kind of art called Realism. Technically it is the replication of an optical field by matching the color tones on a flat surface whether or not the subject matter has or could have been seen by the artist. So can realism be real? Is it a mirror image of visual reality? Can perception be “pure” and unconditioned by time or place? In painting, the visible world must be transformed to the flat surface of the canvas. The artist’s perception is therefore inevitably conditioned by properties such as brushstroke, paint, his or her knowledge, and technique. Even in photography which we might assume would create a pure, real representation of nature, the photographer’s choice of viewpoint, length of exposure, size of focal opening, and lens intervene between the object and the image.

Iconographically realism is the subject matter of everyday contemporary life as seen or as is seeable by the artist. The quarrel in mid 19th century with Romanticism was with subject matter. Realists disapproved of fictional, mythological fantasy subjects because they are not real and visible and are not of the present world. Only the things of the present time, things that can be seen, are real. Realists cut themselves off from the past. This signaled the end of history painting and a move toward historical genre painting, in other words, painting scenes from everyday life of Greece and Rome.

There was a new interest in the depiction of time, captured as it is now. It is a disjointed temporal fragment with no sense of what preceded or what would follow. This also included the elimination or reduction of traditional values. Adversaries were quick to accuse realists of producing works that were emotionally and morally lacking in continuity and coherence. Critics accused artists of a lack of emotions or any understanding of the implications of a scene. Realists expanded their field of vision to a wider range of experience. There was a new demand for democracy which opened a whole new realm of subjects unnoticed or considered unworthy before their time. The boundary line between the beautiful and the ugly had been erased. Realists placed positive value on the depiction of the low, the humble, and the commonplace, the socially dispossessed or marginal as well as the more prosperous sectors of contemporary life. They turned to the worker, the peasant, the laundress, the prostitute, the middle class café, their gardens, stone breakers, rag-pickers, and beggars.

But realists did not just depict peasants. The realist commitment went deeper. This was the artist striving for sincerity. Although the realist refrained from comment in his or her work, the whole attitude toward art implied a moral commitment to the values of truth honesty and sincerity. The artist striving for truth or sincerity had to guard against distortion or alteration by conventions or preconceptions. Some critics went so far as to say that sheer ignorance or lack of training were positive assets for the artist. Some proposed a closure of the Academy and others proposed that they burn down the Louvre. The realist sought to be divested of the impediments of traditional training. Realists shared the scientist’s respect for facts as a basis for truth. Realists admired science and sought to imitate many of its attitudes. Realism was attacked because of its reduction of the human situation to that of an experimental laboratory. Photography was condemned outright by Baudelaire as a threat to genuine artistic creation.

One of the most important influences on the art of Europe was the opening of Japan by Admiral Perry. Interest in Japan was part of the 19th century’s continuing Romantic interest in exotic cultures. By the 1880’s it caught the imagination of French women who seemed entranced by Japanese print albums and fans that could be bought in Parisian department stores. Le Bon Marché and other department stores sold print albums at very cheap prices, and some were not very good quality. It was a popular fad encouraged by textile and ceramic manufacturers. Trade in Japanese goods increased drastically. As illustrations of Japanese landscapes and other books came to Europe, travelers went to Japan and brought back art which was placed on exhibit in European settings.

The art of Japan was also taken seriously by some artists who analyzed it and absorbed concepts into their own style. Some artists belonged to a Société du Jing-lar where they dressed in kimonos, discussed Japanese art, ate Japanese foods, and in general tried to find ways for the Japanese print to help French printmaking.

Here is a list of the most important elements of Japanese art that made their way into western art of the 19th century:

- Depicting changing seasons and slanting rain

- Placing figures randomly and often asymmetrically

- Severing forms by the edge of a composition

- Placing forms in the foreground, which intensified study of details. Often a figure or object is large

- Showing a bird’s eye perspective, as if seen from far above the ground

- Using a confusing perspective

- Including Japanese objects such as fans, kimono’s, and porcelain ware

- Leaving large areas of negative space

- Using silhouette images with no solidity or shading

- Concentrating on a surface pattern

- Implying that what is not represented must be imagined

- Flattening pictorial space

- Often the theme was a woman in a bath

- Including poor human anatomy, no perfect nude models, and an elongated female form

- Using broad diagonals

- Showing events in mid-action

- Eliminating the ground or skyline

Artists who thought of themselves as realists and those who eventually broke away and became Impressionists used the elements and the physical accoutrements of Japanese culture in their art. Japanese woodcut prints from the Ukiyo-e tradition were used by artists all over Europe, but especially in France. Use the list of characteristics above and look at figure 4.4 which is taken from a series of Famous Places in the Eastern Capital. Not all of the items in the list are used in Hiroshige’s print.

As an example of how important Japanese culture became to the European artists of the late 19th century, notice how Claude Monet painted his wife Camille wearing a kimono, surrounded by fans, but wearing a blond wig to emphasize that she is of western descent.