4.4 IMPRESSIONISM – MONET

Claude Monet

Claude Monet (1840-1926) was the son of a grocer, and spent his youth in Le Havre, Normandy. His father wanted him to go into the family business and did not want him to become an artist, but his mother was more sympathetic. She died when he was only sixteen and he was sent to live with an aunt. Monet attended the Academie Suisse where he learned the basics of painting but was not noticed for his first works. He spent two years of military service in Algeria and he later said that the bright light and color of North Africa strongly influenced his later art. He began painting large outdoor canvases in the early 1860’s and was influenced by the works of Corot and J.M.W. Turner.

Monet’s early work used thick pigment applied with a flat brush and he left that thick paint visible on the surface of the canvas. He used color in both the bright and shaded areas of his canvas. He used a rainbow palette and disliked black. His works were a moment in time and he sought to capture the essence of light and color and to cause forms to dissolve in light. His work Women in the Garden was an attempt to paint portraits in the open air. He was so interested in working out of doors that he had a trench dug in the garden and lowered a huge canvas into it with a pulley. He could then move the canvas up and down so he could reach the top of the canvas when painting it. Monet’s model for all four women was his model Camille, but his focus was not the women but the play of light on the fabric of their dresses. When Monet left in the fall of 1866, probably to escape creditors and life with his family, he left behind 200 paintings which he made sure to mutilate to prevent them from being sold. This picture he took with him to finish in the studio. In 1866 Monet had a child with Camille, which was probably another reason he left his family home. The couple married in 1870 and eventually had two sons. In 1870 Monet traveled to London to look at the works of Turner and study the effects of light and haze in his works. In 1871 Monet moved to Argenteuil near Paris and it was in Argenteuil that Monet painted some of his most famous paintings.

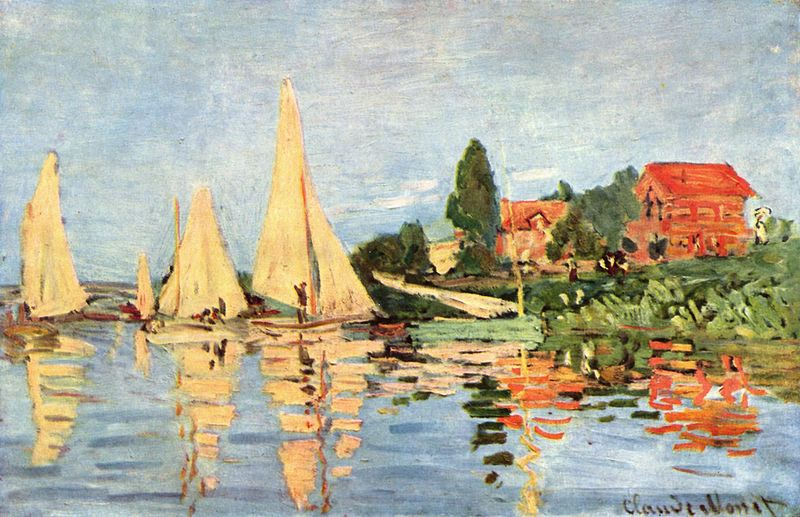

The harbor, bridge and water at Argenteuil offered many opportunities for Monet to experiment with his new found love of the effects of light on water. He wanted to portray the instantaneity of the moment and see the water, light, and color in a single sparkling image. His small dots of color are vibrant and without form. In fact he wanted his forms to dissolve into light. If you stand very close to one of his works all you see are daubs of paint. It is not until you step much further back that the forms come together into a recognizable shape. His canvases are luminous and the colors seem to dance on the surface of the water. The Regatta At Argenteuil is a juxtaposition of blue and orange, red and green, which creates tension.

Bridge at Argenteuil 3:25

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/impressionism/v/monet-the-argenteuil-bridge-1874?modal=1

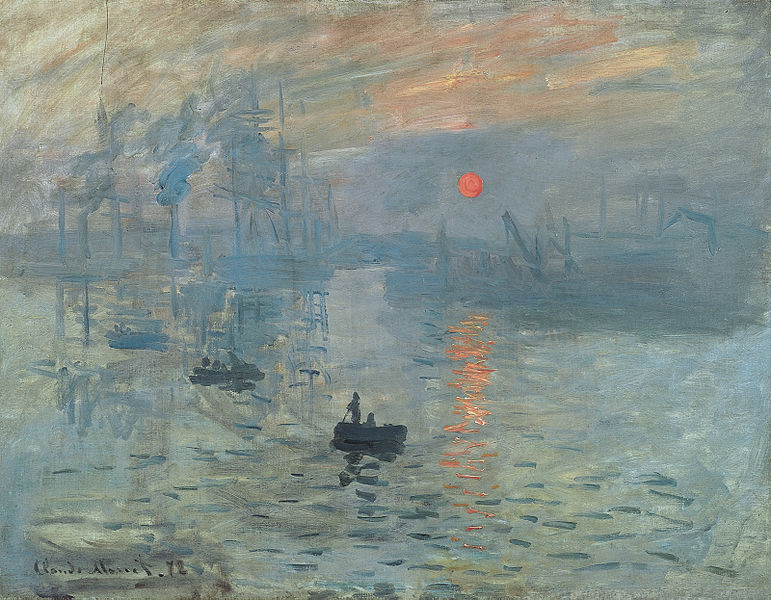

It was at Argenteuil that the Impressionist technique was born, but the term Impressionism was applied in a derogatory description by art critics. Monet’s work Impression Sunrise was a study of light, mist, and their reflections on water. The critics said it was unfinished and unworthy to be shown in the official Salon. Artworks shown in the official state sponsored Salon were selected by a jury, and many of the artists with new ideas were not chosen to show their work. So instead of waiting, they banded together and set up their own show. They collected money, rented a studio, and advertized their own exhibition. They called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Printmakers. Their work was shown each year from 1874 to 1886. Monet’s Impression Sunrise was painted at Le Havre, Normandy near his family home. Notice that the brushstrokes are flat and highly visible. There is not an attempt to justify the paint into recognizable forms. This is not about painting a boat or a sunrise; it is about capturing the momentary light and the atmosphere of the scene.

“The critic Louis Leroy was the first to emphasize the term “impression” in relation to the new painting, adopting it from Monet’s Impression: Sunrise in a satirical dialogue entitled “Exhibition of the Impressionists” that was published in the popular illustrated magazine Le Charivari. Leroy found Monet’s use of “Impression” in his painting’s title particularly appropriate because it suggested that the work was unfinished according to Academic conventions of representation; that is, it represented a mere impression of the scene, rather than a fully structured and completed work of art. Leroy repeatedly emphasized the term “impression” in the dialogue and described many of the paintings by Monet and his fellow exhibitors as sloppy and slapdash, going so far as to compare Monet’s Impression: Sunrise see figure 4.47, to embryonic wallpaper and Pissarro’s Hoarfrost to paint scraped off of a dirty palette.”4

So what are the basic tenants of Impressionism? In its purest form it includes the following:

- Rendering a passing scene including flux, movement, light, and atmosphere

- Painting modern subjects instead of religious or historical scenes

- Focusing on the human figure

- Painting plein aire, which means painting out of doors and not in the studio. This enables the study of the fugitive effects of light. Monet often began his work out of doors and then brought it into the studio to finish it.

- Using a rainbow palette to capture the light

- Eliminating dark under painting and outlining

- Leaving brushstrokes visible and not blended

- Juxtaposing paint rather than mixing it on the palette

- Relying on optical research. Chevreul’s color theory said that colors mix in the eye rather than on the palette.

- White highlights a color it is placed next to

- Black bleeds a color

- Grey adds brilliance and displays the complementary color of any color it is placed next to. (grey next to green will look red)

- Using random, unposed compositions and radical cropping. Scenes were unbalanced and candid showing a slice of life with no dramatic focus

- No didacticism and no moral standards of unchanging truth and timelessness

- Scenes are optimistic, unproblematic, gay, bourgeois, and not aristocratic

- Nature is a source of spiritual refreshment

- There is a fascination with science and truth

The New Painting, Concerning the Group of Artists Exhibiting at the Durand-Ruel Galleries, by Louis Emile Edmond Duranty, is a 38 page pamphlet published in 1876. It did not mention “Impressionism” or the names of the artists who participated in the new movement, but everyone in the art world knew who Duranty was referring to. Here is a translated excerpt from his pamphlet: “In the field of color they made a genuine discovery for which no precedent can be found, not in the Dutch master, not in the clear, pale tones of fresco painting, nor in the soft tonalities of the eighteenth century. They are not merely preoccupied by the refined and supple play of color that emerges when they observe the way the most delicate ranges of tone either contrast of intermingle with each other. Rather, the real discovery of these painters lies in their realization that strong light mitigates color, and that sunlight reflected by objects tends, by its very brightness, to restore that luminous unity that merges all seven prismatic rays into one single colorless beam—light itself. Proceeding by intuition, they little by little succeeded in splitting sunlight into its rays, and then reestablishing its unity in the general harmony of the iridescent color that they scatter over their canvases.”5

Monet chose subjects which best show luminous light: water, snow, fog, mist, and smoke. His Gare San Lazare, shows the arrival of a train amid the rising mist of the engines in the station. Gare San Lazare is a large and very busy train station. Monet painted twelve canvases of the interior of the station to try and capture all aspects of it. In this version of the train station, shown in see figure 4.48 the light seems to be able to waft through the glass overhead, illuminate the clouds of steam, and fall on the engines and tracks and people below. The solid buildings in the background are apartment buildings, but they seem to almost disappear into the haze and mist of the Paris sky. Monet, like the other Impressionists, was interested in modern life, and the roaring, steaming engines were an important part of that.

The Gare San Lazare, by Monet 5:26

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://smarthistory.org/monet-the-gare-saint-lazare/

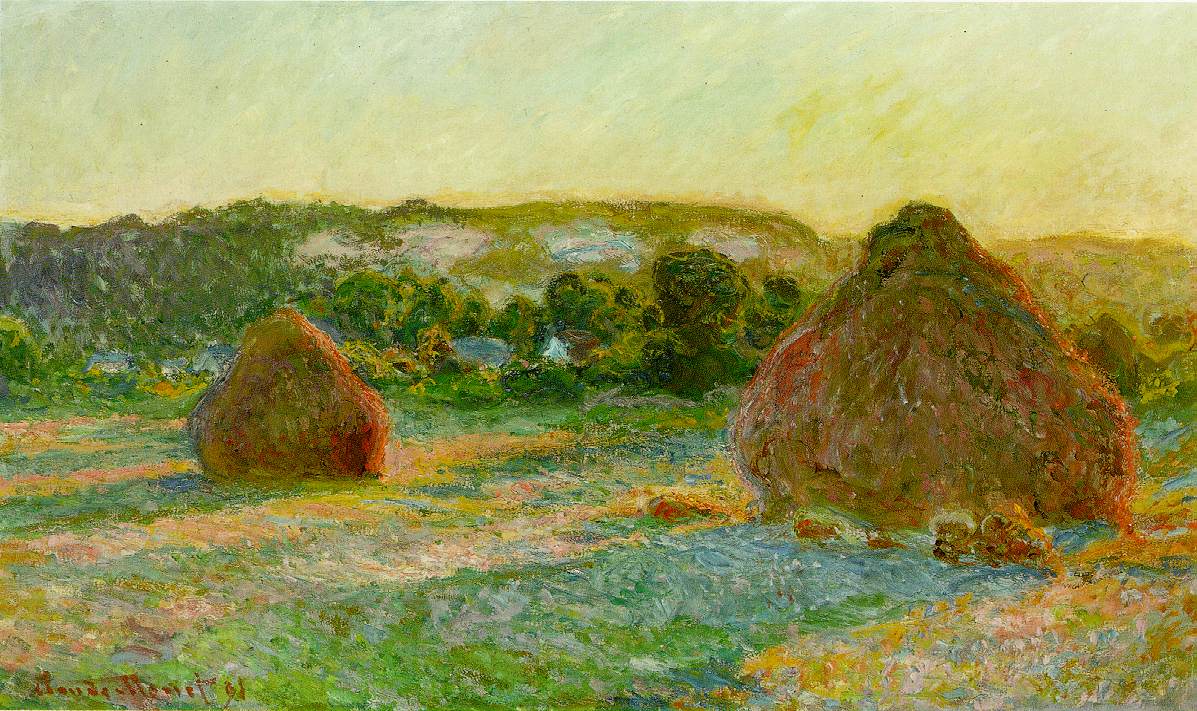

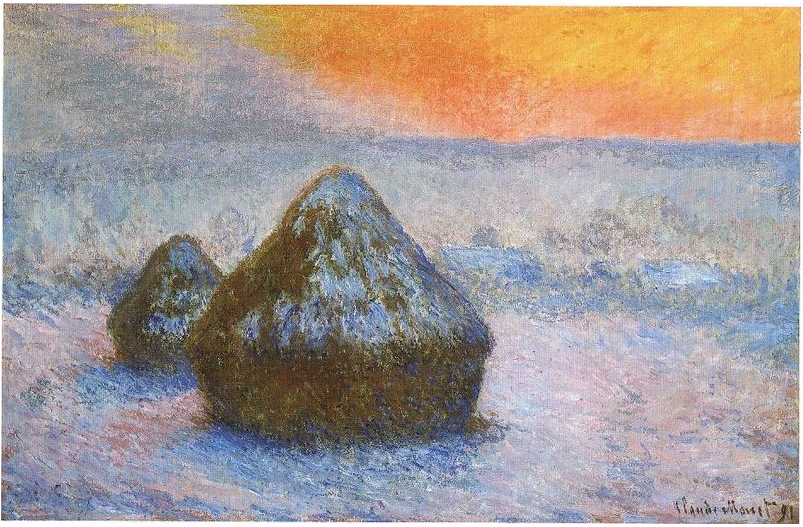

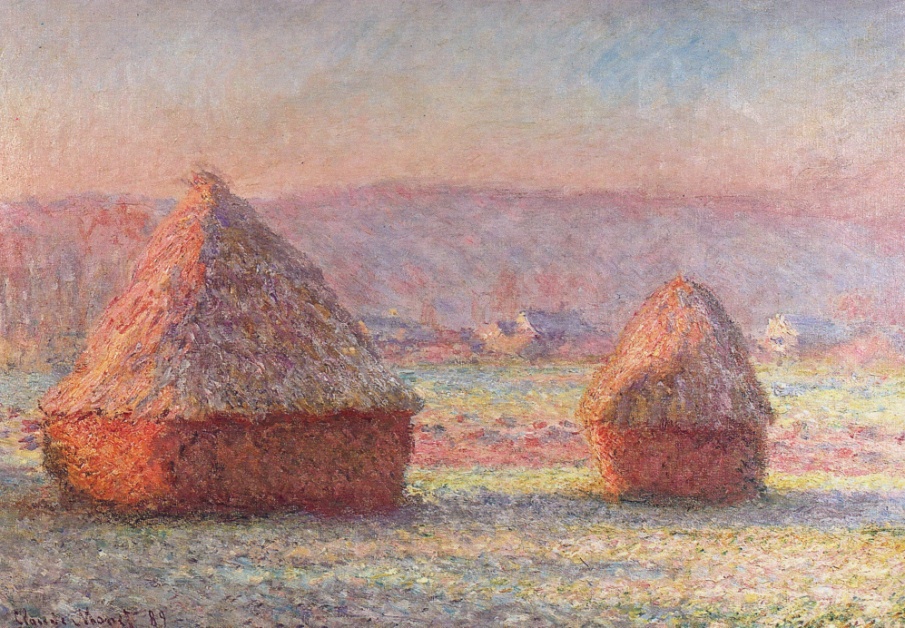

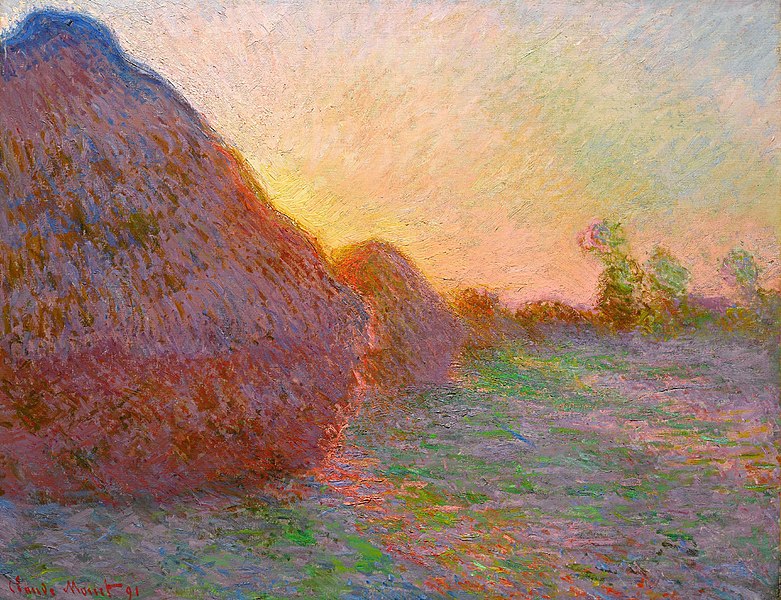

As Monet began to study the effects of light, he focused often on series paintings. These were groups of paintings of the same or nearly the same subject painted at different times of the day and different seasons of the year. He used this process to better understand how the light and its color changed. He did not record the realist’s gradations of light and color. Instead he recorded his own sensations of color. This allowed the outlines and solidities of the objects to melt away.

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/impressionism/v/monet-rouen-cathedral-series-1892-4?modal=1

The Rouen Cathedral Series was begun in February 1892 above a shop called Au Caprice on the rue du Grand-Pont in Paris. There monsieur Mauquit rented Monet a room where he could work on the more than thirty canvases. He lived and painted there for several months. These show the Rouen Cathedral observed from the same point of view, but at different times of day and in different weather conditions. Monet gives us, with scientific precision, an unparalleled record of the passing of time as seen in the movement of light over the solid form of the building. Critics accused Monet of destroying form and order for the sake of fleeting atmospheric effects. Monet worked on many of the views at the same time, and switched from canvas to canvas as the light changed during the day. For Monet light was the form, the subject, and the end. When he was finished he selected twenty of what he considered to be the best views and displayed them in an exhibit. There were suggestions that the state purchase them and keep them together, but eight were sold, and in the end they were disbursed around the world.

Monet Water Lilies 6:22

If you receive an error with the link above, use the following link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/impressionism/v/monet-les-nymph-as-the-water-lilies-1918-26?modal=1

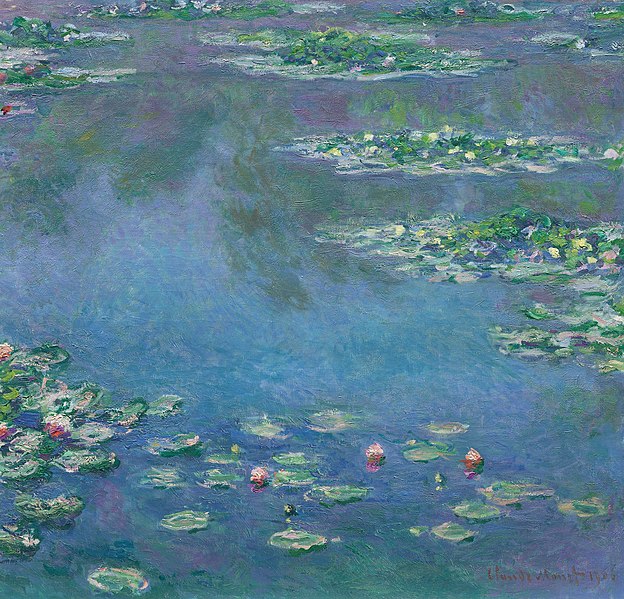

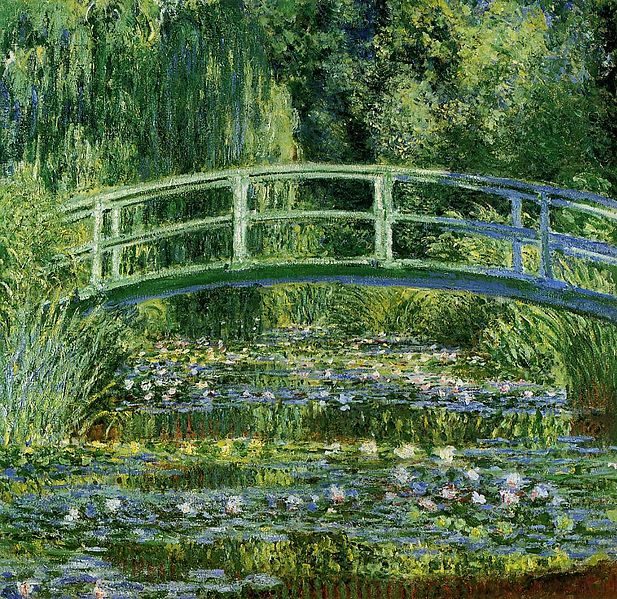

In 1883 Monet purchased a home in Giverny which is in the outskirts of Paris. He lived there until his death in 1926. The property had a home, which he enlarged, a barn, which he renovated and enlarged so he could use it as his studio, and a storage place for his large canvases. His home was filled with color. The dining room was bright yellow and the kitchen was blue. Japanese woodblock prints hung throughout his home.

But the most important parts of his home were the ponds and streams. Monet worked on the water features and the surrounding gardens for much of the last forty years of his life. He built and maintained paths and arches and bridges and used these gardens and ponds as the subject matter of many of his most famous paintings. Other artists were drawn to Giverny, partly because Money was there and also because of the beautiful landscapes of the area.

As he aged Monet’s eyes began to be impacted by cataracts. From 1912 to 1922 he began to notice a deterioration of his vision. There was medical treatment for cataracts at the time, but in some cases it was not successful and some patients lost their sight. For many years Monet refused to get the surgery. His paintings of that time are much different than his earlier work. Monet consulted with several ophthalmologists, tried different drops and glasses, and in 1923 finally agreed to a small surgery. It did not go well. Against the wishes of friends and family he began to destroy canvases from his recent period. Eventually, in 1925, his surgeon covered his left eye completely with a black lens and he was able to see relatively better. He was reconciled with his situation and resumed his work.21

Claude Monet was prolific and driven. He was the leader of the Impressionist movement and taught others to look at the world in a different way. It was his leadership that brought the western art world into Abstract Expressionism and totally changed the way we look at the world and the artist’s place in it. Art would never be the same.