2.2 PAINTING

Neo-classical painting took much of its subject matter from Greco-Roman antiquity including classical mythology, classical history, and literature. Artists used classical forms such as columns, pediments, statuary and vases in their work. Wall paintings, implements, mosaics, dress, jewelry and architecture were discovered as they had been left on the day Mount Vesuvius erupted. There was a new desire among the middle class to learn about the discoveries and what had happened that day in 79 CE.

There was also a growing reaction against the excesses of the aristocracy. People wanted to put aside the unintelligent, the coy, and the flirtatious. They sought the simple rather than the decorative and put aside the sinful excesses of the Rococo. Works like The Swing by jean-Honoré Fragonard lost favor with the buying public.

Reading classical history brought forth examples of virtuous conduct rather than eroticism. It was all the rage to read the Roman writers such as Cicero, Horace, Tacitus, Seneca and Plutarch. Self-sacrifice and heroism were more important than pleasure and fun. When the Americans proclaimed independence from the British king, others around the world wondered if their government should also be based on an agreement between the people and the king. People began to read biographies and travelogues to learn more about the world around them. “Many of the symbols of the French Revolution too were borrowed directly from the ancients. The cap of liberty was a copy of the Phrygian cap worm by the liberated slaves in Rome. The fasces, or bundle of sticks with the protruding ax tied together with a common bond, was once again the symbol of power.”2

During this new Neo-classical era art had new “moralizing” attitudes and the artist became the teacher. The artist was now more educated and was expected to teach Stoic virtue. The new attitudes could take several forms. They might focus on “gothic horror” and show pain and anguish, violence, gloom, death, and terror. Or they might concentrate on love themes using antique love stories of unrequited love. This might take the form of sexual themes, cool statuary, or lovers in ancient costumes. There were deathbed scenes, gravity, and seriousness compared to the silliness of the previous Rococo works of art. Christian traditions lost their validity and became part of the past. Morality became atheistic. For centuries people had turned to the church and had faith in its morals, but now faith was placed in the newly created state.

These new moralizing attitudes were “exemplum virtutis” or we might say an example of virtue, or a model of virtuous behavior which others should follow. Not only were the new morals against the excesses of the earlier Rococo, but they supported the overthrow of the aristocracy. This happened as the middle class began to grow. People were encouraged to seek virtue rather than material wealth. There was an unyielding dedication to the support of the government regardless of family tragedies. Death was preferred to dishonor. Allegiance should be to the state rather than to the family. These ideas became important just as cries for revolution increased all over Europe.

Angelica Kaufmann

Angelica Kaufmann (1741-1807), Maria Anna Angelika, Kaufmann, was born in Switzerland, trained with her father who was a mural painter and worked as his assistant. His work caused them to travel most of the time and enabled her to become familiar with the art and architecture of ancient Rome and the Renaissance. Some think of her as a child prodigy because she was producing and selling portraits when she was a young teenager. Eventually she spent most of her productive years in London where she enjoyed a lucrative career as a portrait painter. Kaufmann had a huge clientele from the aristocracy and from royal patrons. She is also known for her history paintings. She was a protégée of Sir Joshua Reynolds and an interior decorator. Kaufmann was also a founding member of the British Royal Academy of Arts and enjoyed a fashionable reputation. “In 1781 she married the painter Antonio Zucchi who then became her business manager. When she died, Kaufmann’s funeral was directed by Antonio Canova who based it on the funeral of the Renaissance master Raphael.”5

One of her most well known history paintings is Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi. In it a visitor has come to see Cornelia and has brought her jewelry box to show off her treasures. The setting is in front of Roman columns and the women and Cornelia’s children are all dressed as we would expect to see Roman citizens. What makes this work important is Kaufmann’s use of the story to present a model of virtue, or exemplum virtutis. Instead of retrieving her jewel box, the virtuous mother presents her children and says, “These are my jewels.” The two children on the left are still young, but Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, will someday be important political leaders who worked for social reform that would benefit second century B.C.E. Roman citizens.

Kaufmann’s portrait paintings are numerous. This one is of Barbara St. John Bletsoe, the second wife of the Earl of Coventry. Her skin is pale and her clothing and jewelry are those of a well dressed aristocrat. She wears a pin with a ruby and a large pearl. But this is not just a well dressed wealthy woman. On the table beside her is a shuttle that was used to make lace, much like the tatted lace that was made by wealthy ladies in the 19th and 20th centuries. This is another example of exemplum virtutis because she has learned a skill that makes her productive, even though she does not have the financial need to make money.

Jacques-Louis David

Another important painter of this time period is Jacque-Louis David. He was born in Paris, the nephew of Francois Boucher. His father died in a dual, leaving his mother and uncles to raise him. He received classical artistic training and competed several times for the coveted Prix de Rome, which he eventually won in 1774. As time passed and David gained notoriety and power, he also became more and more committed to the Revolution in France. He served in many Revolutionary capacities, voted to behead the king and queen and presided over the convention as a legislator. He worked with Robespierre to plan national pageants which were used to indoctrinate the public about revolutionary ideas. Eventually, Robespierre lost power and David fell with him, barely staying clear of the guillotine. He was in prison for several months and when he got out, he spent several years distancing himself from politics.

One of David’s most important works during his revolutionary years was the Oath of the Horatii painted in 1784. This work is known as a history painting, and according to the judges at the Academy of Arts, history painting was the noblest subject. In it David tells the Roman storey of the three Horatii brothers who pledge to leave home and family to fight the Albans. Their wives and some children languish on the right. The woman in blue had married into the Horatii family, but her original family was the Alban clan. This is the moment the three brothers swear to fight for Rome, no matter the consequences. Remember exemplum virtutis: here David shows us the perfect example of virtue as the Horatii, in their Roman clothing and Roman helmets. When the people of Paris saw this painting in 1874 they immediately thought of their own revolutionary turmoil and how important it might be to fight the enemy rather than to follow the wishes of their family.

Watch the Khan Academy about The Oath of the Horatii 6:2411

If you cannot access the link above, use this link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/rococo-neoclassicism/neo-classicism/v/david-oath-of-the-horatii-1784

David‘s work “The Death of Marat” is an amazing portrait of a revolutionary leader who was stabbed in his bath by a woman visitor. Notice the note in his hand that she used to gain entrance to his home. Marat is said to have contracted a skin disease while hiding in the sewers beneath Paris, so he spent much of his time in the bath to relieve the pain. Compare Marat to Michelangelo’s Pieta: the wound in his body, the position of his hand. David wanted to convert Marat’s bathroom to holy space, and the inkwell, knife and quill were to be considered holy relics. David’s painting, and the revolution it aggrandized, sought to lower the stature of the church. Click the link below to hear one explanation of David’s work and the historical events that surrounded it.

Watch the Khan Academy about the Death of Marat 6:2313

If you cannot access the link above, use this link https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/rococo-neoclassicism/neo-classicism/v/david-marat

One of the things David had done while in power during his involvement in the early revolutionary years was to disband the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The Academy had been a gathering place for art students and had controlled the arts, determined who would be trained, who would be given commissions, and who would have the blessing of “The Academy”. After the fall of Robespierre, the Academy was reestablished and David again became a member. He also set up a large studio of his own and engaged with hundreds of students to teach them the basics of art.

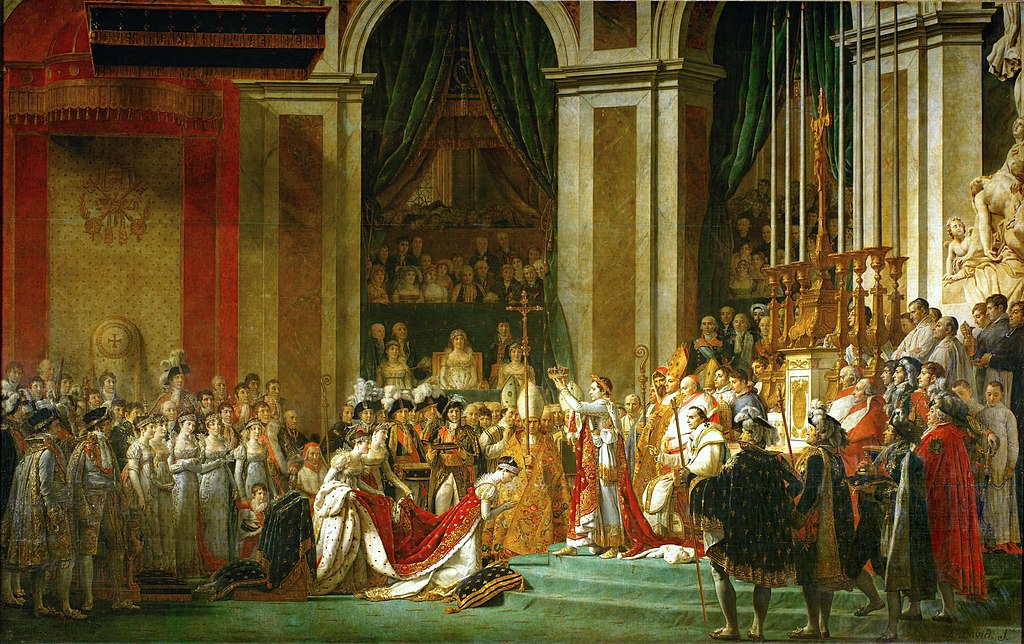

The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte caused David to rethink his short lived apolitical attitude, so he sought to paint for the new ruler. The Coronation of Bonaparte must have been an unsavory change for the classical painter that David had been originally. But from our perspective it is a grand example of history paining. It is interesting that now, instead of simple Roman attire, participants wear embroidered velvet, gold and jewels, amid pomp and ceremony. This is the moment when Napoleon has already crowned himself and he now approaches Josephine with the crown he plans to place on her head. They are in the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris and pope Pius VII sits in the background giving his tacit approval. Gone are the patriotic works of the revolution. David’s largest work, this was done in 1805-07. It is now like the official portraits of the aristocracy we used to see in the grand paintings of the Renaissance.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Before we finish with the Neo-Classical era, we should look at one more artist: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) who was a student of David. He looked to the artists of the past such as Raphael and others of the Italian Renaissance and revered their work. He attended the Royal Academy in Paris where he studied painting and architecture, and developed the ability to play the violin. As time passed, his work changed from history painting to portrait painting. When we look at his depictions of the human form it will become evident that he distorted form in ways that made his work a precursor of the modern art that was soon to come. When he left the Academy Ingres joined the studio of David and learned from him for four years. In 1801 he won the Grand Prix de Rome but the government of France was not well organized at the time and did not have the funds to pay the prize money, which was intended to allow the artist to travel to Rome and live and study the arts there. Eventually they paid him and he began his studies at the Villa Medici. He was commissioned to paint several history paintings. When Napoleon fell, he was left in Rome without income or patrons. To make a living he drew small pencil portraits of tourists visiting Rome. Later art historians consider these portraits to be some of his best work.

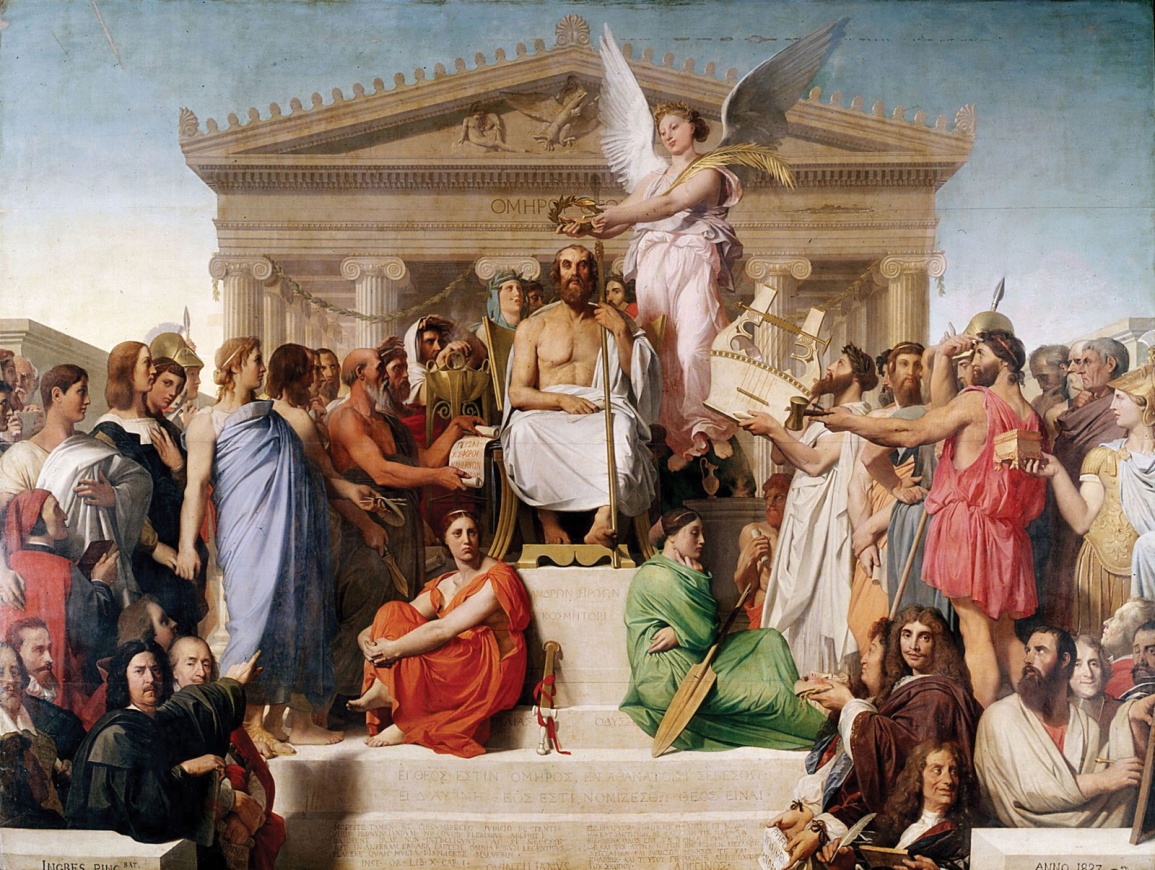

The Apotheosis of Homer, figure 2.12 was painted by Ingres in 1827. It is based on classical Greek history, and is an example of the type of painting for which he wanted to become famous. But it was his paintings of the female form, both dressed and nude that places Ingres on the cusp of Neo-Classicism and Romanticism, which we will look at next. Ingres always placed himself firmly in the Neo-classical category and even disliked the Romantic painters of the day. But his work seems to lean away from history paintings and toward the Romantic genre.

Watch the Smart History video about La Grande Odalisque 4:1217

If you cannot access the link above, use this link https://smarthistory.org/painting-colonial-culture-ingress-la-grande-odalisque/

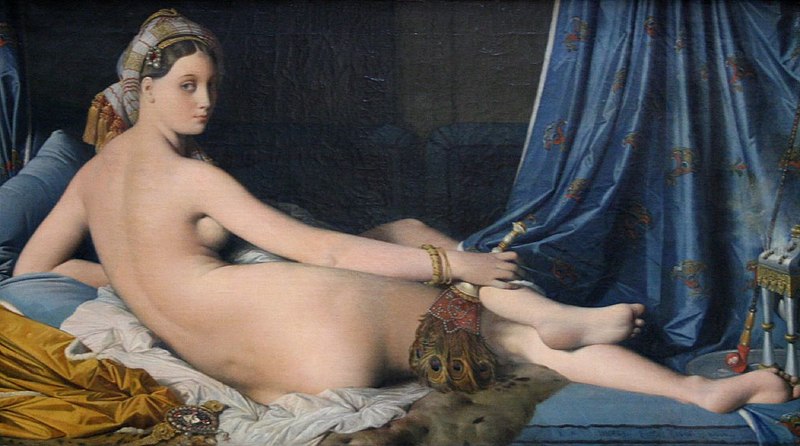

One notable painting that causes us to place Ingres outside of the category of history painter is La Grande Odalisque. Notice how long her torso is and notice that her left leg could not possibly connect to her body and then curve into the position painted by Ingres. The subject matter is a woman in a harem, surrounded by beautiful silks, peacock feathers, and ornate jewels. This is one of the definitions of a romantic painter: to paint scenes of faraway places and people dressed in unusual costumes.

The portrait of Comtess d’Haussonville is also in this category. Look at the placement of her right arm. There is no way a human body would be built like that. So both La Grande Odalisque and the portrait of Comtess d’Haussonville also cause us to think of Ingres as the forerunner of modern art. He dared to paint the human form in distorted ways, without respect to correct anatomy. We will soon see more of this type of art, but in his time, it was very adventurous.