5.7 FUTURISM AND THE MECHANICAL STYLE

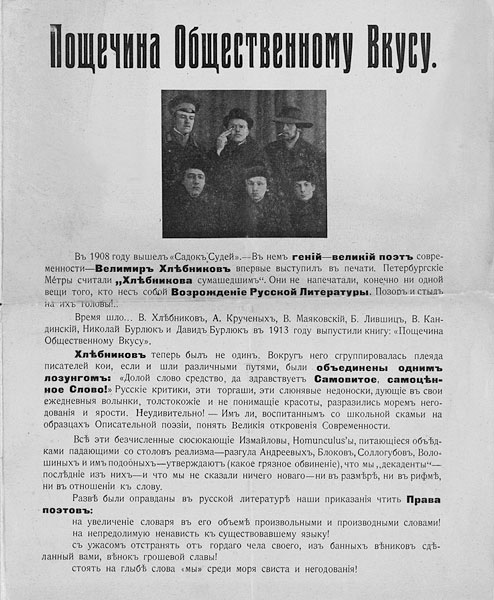

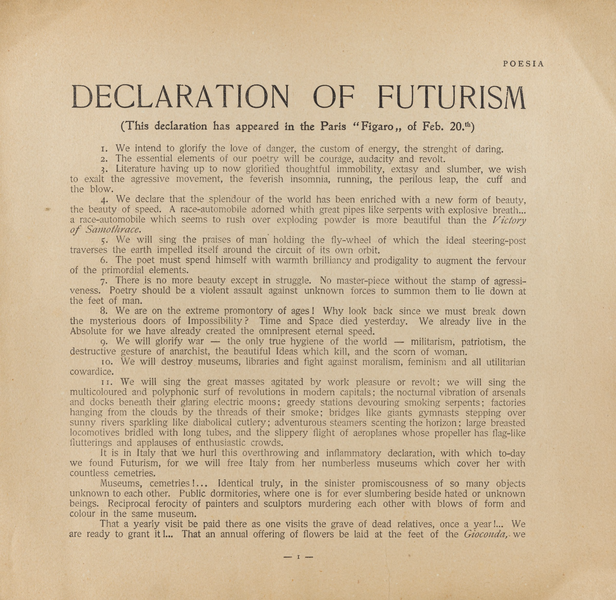

Another important early modern style is Futurism. It began in Italy under the poet and dramatist Filippo Tommaso Marinette before World War I. In 1909 he released the Futurist Manifesto. In it Marinette declared that Futurism would deliver Italy and the world from its plague of professors, archaeologists, tour guides and antique dealers. Marinette proclaimed a new art of violence, energy and boldness. Futurists believed that war was necessary because it would rid society of the evils of the past, just as the sciences rid mankind of the misunderstandings of the past. The past included museums, libraries and cities. Umberto Boccioni proposed that they sweep all motifs and subjects that had already been exploited, destroy the cult of the past, and eliminate any form of imitation. He said art should extol every form of originality and glorify the life of today unceasingly and violently transformed by victorious science. They sought a new reality through speed, technology and war. Above all they admired motion, force, speed and strength of mechanical forms, and they attempted to show dynamic motion in their paintings. Their canvases were filled with automobiles, airplanes, trains, machine and guns. However, they also had a political agenda, and after World War I the movement fell apart because the war had not answered all the problems.

Like the cubists they portrayed a unification of the painted object and its environment. They did this by using the cubist vocabulary and using cubist treatment of space. However, they tried by repetition of forms across the plane, to impart movement. Movement and time obsessed the futurists. Everything moves, everything runs, everything turns quickly. The figure in front of us is never still, but ceaselessly appears and disappears. Due to the persistence of images on the retina, objects in motion are multiplied and distorted, following one another like waves through space. Thus a galloping horse does not have four legs, it has twenty and their movements are triangular.3

Fernand Leger

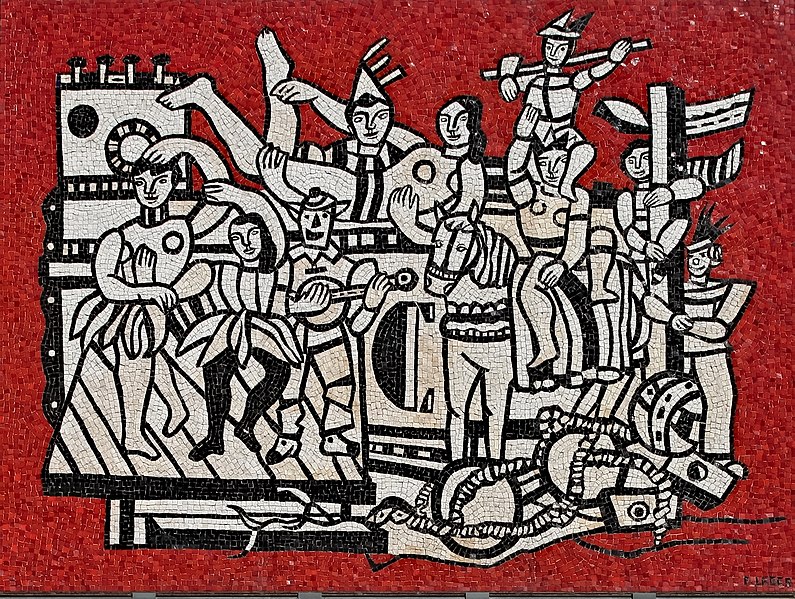

Fernand Leger (1881-1955) was a friend to the cubists and a follower of their ideas. He was born in the Normandy region of France and served an apprenticeship in an architect’s office as a draftsman. He attended the Paris School of Decorative Arts and studied on his own after seeing a retrospective of Paul Cezanne’s work. His works have the sharp precision of the machine, the beauty and quality of which Leger was one of the first to discover. He is the painter of modern urban life, including in his works the effects of modern posters and billboard advertisements, flashing electric lights, the noise of traffic, and the robot-like movement of mechanized people. His is the mechanical commotion of the city. In 1926 he conceived, directed, and produced an abstract film called Mechanical Ballet, in which machine forms replaced human beings and their activities. It even included the sound of an airplane engine. Although many of his works are similar to Cubism, he adapted their ideas and created tubular shapes. Often his humans are slabs and cylinders that look much like robots.

After his service in World War I in which he served as an engineer, he became more interested in cylindrical shapes like those he saw in the weapons and ammunition of the war. He was gassed at the Battle of Verdun and spent time recovering before he was able to return to painting. Leger loved machine parts such as crankshafts, cylinder blocks and pistons, all painted in primary colors. He looked back to Cezanne’s ideas about the sphere, cylinder and cone and used them to create fantastic modern environments. His world was unsentimental and populated by robots that had no feelings. His human forms were purposely inexpressive. He used literal elements of machines and buildings: robot figures mounting a staircase, stenciled letters and signs all contribute to the kaleidoscopic glimpses of the industrial world. These are not entirely abstract because he has left glimpses of the real world. But he has put them together in a way that we do not recognize as a real place, only parts of a modern world.

Leger wanted to prove that every industrial object possessed an absolute value regardless of its specific role in the machine. Here he simplifies the human and mechanical forms. He gives this work a feeling of abstraction, intensity and monumentality. We cannot tell what all of the elements are, nor does it matter. Each member in the parade does its part. The figures are rendered as black outlines against a red background. Objects and people are broken into facets and reassembled in barely recognizable forms. Although the lines are clear and crisp, they do not represent reality.

Giacomo Balla

Another artist that explored Futurism is Giacomo Balla (1871-1958). He was the oldest of the members of the Futurist group and was the teacher of Severini and Boccioni. His most famous work is Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, which he painted in 1912.

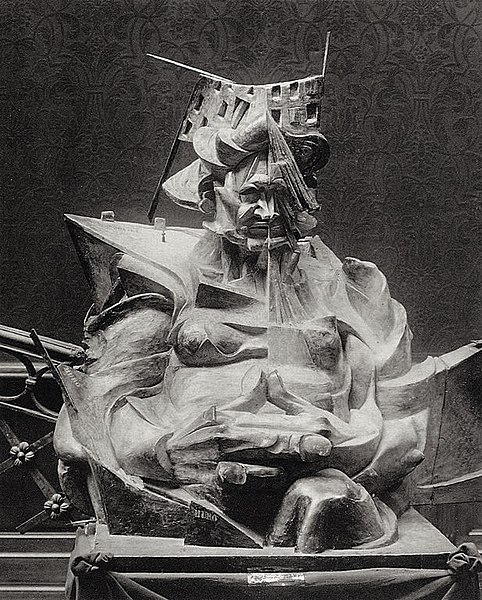

This work portrays the movement of a dog, by repeating the main form several times across the canvas. This little dog scurries forward on his short Terrier legs, creating movement because there are so many of them. We cannot see his owner’s feet because they are not important to the image. All that matters is the little dog running as fast as he can. This method for showing rapid movement or physical activity became the stock method used by comic strip artists and animated cartoons as they became popular. Giacomo also worked in sculpture. See his Sculptural Construction of Noise and Speed as reconstructed and displayed in the Hirschhorn Museum

Gino Severini

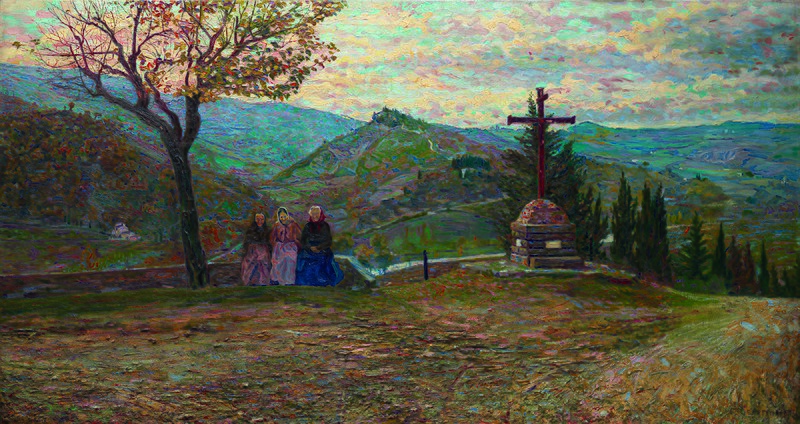

Gino Severini (1883-1966) was born in Cortona, Italy and worked with Giacomo Balla. Severini became interested in the new types of art happening in France so he moved there in 1906 and met Braque, Picasso and the writer Guillaume Apollinaire. You can see Balla’s pointillist influence in the painting below.

This is one of Severini’s early works, painted in the small Tuscan town of Dicomano. Three elderly women sit quietly in a natural setting. They may be Severini’s way of depicting human harmony with nature. Or they could be his way of saying that these old women, like the leaves on the tree above them, are withering as they age. Severini thought of this painting as a culmination of the painting techniques he had learned from Balla and considered it one of his most important works to that point. It shows his growing interest in the experimentation with color and the division of paint on the surface of his canvas. Notice the small dabs of paint that are not blended in the sky, the mountains, and the foreground. He was very happy with this work and believed that it was better than what he had done in the past. He continued to work with the pointillist ideas until he signed the Futurist painters’ manifesto in 1910. Although he wanted to portray movement, speed, and action of the modern life, he was not as interested in the political beliefs of the Futurists.

Umberto Boccioni

Umberto Boccioni’s (1882-1916) most important contribution was his cubist-futurist sculpture, but he also painted. In The City Rises he sought “a great synthesis of labor, light, and movement. In the foreground we see a large, surging horse which is running over humans in its way. Boccioni is attempting to convey speed, light, and action. Solid shapes disintegrate into intangible masses of light. One of the main ideas was the dynamism of work and labor in modern industrial society. Notice his use of strong diagonal lines to draw the eye back into space and create instability and movement. He also uses warm colors to move forward and invite the viewer into the action.

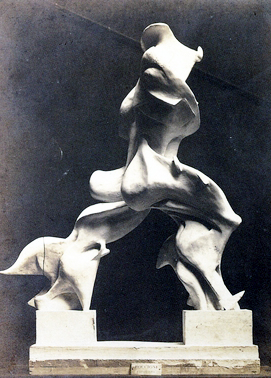

In 1912 he wrote “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture which attacked the old problem of how to organize three-dimensional space, intangible space, so that it expressed as solid mass. Be he also sought to assimilate the object into its surrounding space, as cubist painters had created paintings in which the object was indistinguishable from its surrounding space. In 1913 he created Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, which is a striding figure with a fluid form, curing planes of bronze moving in two dimensions. Compare it to the Victory of Samothrace with her wings and draperies flowing out behind her. It looks like her even more because her arms are missing. Boccioni’s subject is speed, not the figure. We feel the swirling, spiraling lines and the rushing currents of air as the figure cuts a path through space. Umberto Boccioni

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.16

One of the tenants of Futurism was to clear away the old versions of art by emptying museums, but instead their art came to be listed in the museum’s holdings.

Joseph Stella

Joseph Stella (1877-1946) was an Italian who came to live in the United States in 1902. He abandoned his study of medicine and turned to painting, and was influenced by the futurists on a visit back to Italy in 1909-12 Stella liked the linear dynamism and use of brilliant colors chosen by the Futurists. To the Italian futurists the United States of the early twentieth century was a romantic ideal, a world of exploding energy, new frontiers, expanding industry, and unlimited opportunity. It was a land without a past to be erased, a clean slate. Stella brought these romantic ideas into his art, especially his paintings of New York and other modern cities. Battle of Lights, Coney Island, Mardi Gras bursts with the energy and light of carnivals and movement, and color, and noise, and smell, and senses. Everything is in flux, and we are not even sure what we are looking at. But it doesn’t matter. It is the essence of light and action rather than a specific light or a specific action. This work was one of the first paintings of its kind exhibited in the United States and it gained him immediate public recognition. From this time forward galleries were willing to show experimental art. Nothing like this had ever been seen here. The public came to see it in droves and the press hated it. Demands for paintings of the newest styles increased and collectors now traveled to Europe to purchase paintings and sculptures.

Stella’s great work is in his depiction of the Brooklyn Bridge, the construction which had become the symbol of the booming, expansive, metropolis. The beams and girders of the bridge are intermingled with the lights of the vehicles crossing it and the buildings behind it. The diagonal lines draw the eye across the bridge to the city beyond. All is light and movement.

My Tree of Life is filled with trees and plants flowers, but nature is not dark or foreboding or peaceful, instead it bursts with light and color. The eye is drawn from flower to sky to forest floor by carefully placed lines and the brilliant colors reflect the light.