7.1 THOUGHT AND IDEAS-EXISTENTIALISM

Existentialism

Experts do not agree on who first coined the term, existentialist, however the ideas relating to existentialism have certainly been around for centuries The ancient Greek Ephemeras suggested that the gods, believed in by most of his compatriots, had been human heroes whose stories had grown over time until they were considered gods. In this assertion, Ephemeras suggests that people do not all share the same truths in reference to beliefs. This lack of a shared reality among believers is a primary identifier of existentialist thought. The doubting of the accepted “truths” of religions has reemerged multiple times in multiple places throughout history. For our purposes we will consider the existential thought that has emerged over the last two hundred years. Keep in mind that most of the philosophers who entertained this realm of questioning did not claim the title of existentialist. That term is finally accepted, although not at first, by Jean Paul Sartre in the 1940s. It is in this period and the decades following it that existentialism can be seen affecting the production of the arts.

The late 16th century was referred to as “The Age of Sensibility” due to the increased focus on subjectivity and introspection. This paved the way for new ways of viewing the human experience. In the following century Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) a religious writer, satirist, philosopher and literary critic (often considered the “father” of existentialism) took these ideas further. Kierkegaard felt that “the suspension of rationality is the very secret of Christianity. Against the cold logic of the Hegelian system Kierkegaard seeks ‘a truth which is truth for me.’” (Kierkegaard 1996:32).1 Here Kierkegaard presents the idea that every individual has their own truth, based on their personal view of the world and their experience within it.

In the later part of the seventeenth century The German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche moved the idea of individual truth a step further. His announced that “God is dead.”

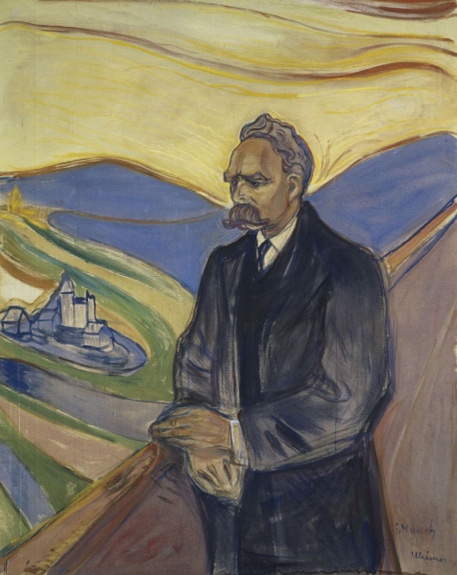

It is no surprise that the German Expressionists had read Nietzsche’s work and some may well have been influenced by it. Edvard Munch did several portraits of the philosopher, so it seems likely that he was familiar with Nietzsche’s ideas.

While there is no proof that Munch engaged in existential thought when creating his art, his work is often used as an example of the angst later associated with the existential movement. On the left is one of several images of the philosopher created by the artist. All of Munch’s drawings and paintings of the philosopher were done nearly a decade after Nietzsche’s death.

Regardless of Munch’s stance on Existentialism, many of the elements of German expressionism fit neatly into expectations of the existential movement that would be popularized later in the 20th century. Below is a brief outline of the seven elements of Existentialism as outlined by Douglas Burnam in his excellent discussion of the movement, “Existentialism.”4

- Philosophy as a way of life

- Anxiety and authenticity

- Freedom

- Situatedness

- Existence Irrationality/absurdity

- The crowd or the herd, the masses etc.

In the 19th and 20th centuries the rapid change brought by industrialization was often seen as alienation from nature and from a natural way of living. Existential philosophy becomes a lifestyle under this definition rather than merely an investigation into the nature of meaning. This can be seen in the alternate lifestyles embraced by many artists and writers at the turn of the century. Also seen at that time is the experimentation with art forms, writing styles and music and dance that result from existential thought. Similar attempts to redefine the arts are again made in the 1980s and 1990s with the implementation of postmodern thought.

Anxiety and authenticity are also identified in much expressionist art and in other aspects of the culture of the early twentieth century. For most people, the anxiety that Nietzsche hints at was focused on the fears that arose during the industrial revolution and after. The search for authenticity is also clear at that tumultuous time. The search for authenticity is one that has recurred countless times in history. Whenever a period’s idealism or realism is no longer an apt descriptor of life, the search is again launched. Similar fears as those of the people affected by the industrial revolution arose later in the century amidst more fast-paced change and the rise of consumerism and mass commercialization.

While there are negative aspects of existential thought it is important to realize that there is a positive side. If indeed the human is not bound by an external compass, rather that is an omnipotent god or a societal expectation, it means the individual has absolute freedom in creating and recreating the self. This freedom from traditional constraints can be viewed as hopeful, even as a possible road to personal or cultural salvation. The reflection of this is clearly seen in early expressionist philosophy as well as in later in postmodern arts.

Burnam’s use of the term situatedness, Burnam means that the freedom discussed above is limited and colored by the situation a person or culture finds themselves in. Even if freedom is absolute, context weighs upon freedom, making freedom all the more meaningful. Situatedness makes the expressionist urge to go back to a simpler time seem absurd. Because the lives of humans are greatly affected by their context, there is never a way to “go backwards.” An existentialist might say that we are what we experience, not just what we wish to experience. Burnam shares, “human existence cannot be abstracted from its world because being-in-the-world is part of the ontological structure of that existence.”5

Existence, in existential thought, is reserved for human existence. Burnham shares, “Unlike a created cosmos, for example, we cannot expect the scientifically described cosmos to answer our questions concerning value or meaning. Moreover, such description comes at the cost of a profound falsification of nature: namely, the positing of ideal entities such as ‘laws of nature’, or the conflation of all reality under a single model of being.”6 Humans searching for meaning in a world devoid of inherent meaning is absurd and “human existence as action is doomed to always destroy itself. A free action, once done, is no longer free; it has become an aspect of the world, a thing. The absurdity of human existence then seems to lie in the fact that in becoming myself (a free existence) I must be what I am not (a thing). If I do not face up to this absurdity, and choose to be or pretend to be thing-like, I exist inauthentically.”7

Nietzsche’s deliberately provocative expression, ‘the herd’, portrays the bulk of humanity not only as animal, but as docile and domesticated animals. Notice that these are all collective terms: inauthenticity manifests itself as de-individuated or faceless. Instead of being formed authentically in freedom and anxiety, values are just accepted from others because ‘that is what everybody does’. These terms often carry a definite historical resonance, embodying a critique of specifically modern modes of human existence.8

Burnham’s definition of existentialism is necessarily broad in scope but it is as close to a single definition as is possible when discussing a term that has been embraced under such a variety of definitions. In any case interest in existential thought was interpreted and popularized by late twentieth century philosophers such as Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1980), Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) and Albert Camus (1913-1960). Many artists in the 1980s and 1990s embraced this philosophy, if not as a lifestyle, as a guide for the creation of a new type of art, which came to be called, postmodernism.

Postmodern Style

The postmodern style was a reaction against modernist ideas. The style rejected the “grand narratives” of modernism. It rejected the intellectual dependence on reason posited by such artists as the cubists. Embracing the existentialist idea that experience is highly subjective, the postmodernists rejected the idealistic vision of the future that art styles dependent on application of the scientific approach or method embraced. Postmodernists, like their predecessors, sought to redefine art. They were against art of ideas and formulas, however popular. The postmodernist painters, writers, philosophers, sculptors, architects, theatre creators, music makers and dancers rebelled against the status quo, against the institutions and rules that tend to structure the arts and human lives.

Postmodern philosophers, among them, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault and Jean-François Lyotard deconstructed language, power relationships, institutional forms and a multitude of other important aspects of modern life that is shared by humanity. The purpose of the deconstruction, in most cases was to reexamine the validity of systems created in and/or based on the 18th century enlightenment. That paradigm shift placed reason above passion and science above internal understanding. Many postmodernists will argue that with the creation of these hierarchies comes internal bias against the individual. By homogenizing human experience, often based on a narrow sampling, institutions, and agencies disproportionally distance some groups from success in the communal “game.”

It is ironic that one of the purposes of many early postmodernists was to eliminate hierarchies such as the placing of “high art” (museum pieces that experts agreed are valuable) above “low art,” (folk art, commercial art, graphic advertising art, graffiti, etc) literature versus the dime novel, good versus bad, etc. This would, in theory, create an art of the people. As you will see, most postmodern art of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s was viewed primarily by elite crowds.

The postmodern style differs slightly depending on the medium used. There is also no single clear definition of postmodernism. Generally, however, the following ideas tend to be elements of this new urban rejection of modernism.

Notice how existentialism integrates with many ideas in the following list:

- Fragmentation (deconstructivism)

- Disassociated relationships between objects

- Surprises and unusual relationships between objects and people

- Meaning must be brought to the piece by the viewer/listener

- Repetition

- Includes pastiche (imitation of past styles or genres)

- Self-referential

- Dark humor

- Unrealistic and sometimes impossible plots or images

- Rejection of traditional form

- Items, people and events out of context or in strange new contexts

- Lack of hierarchical structuring of the experience

- Skeptical of binary constructs (good versus evil, dominance versus submission, king versus subject, etc.)

- Truth is dependent on context, never universal in nature

- Exaggeration of slowing or speeding up of time

- Values and morals are social constructs, not absolute truths

- Rejects all absolutes and universals such as truth, reality, objectivity, human nature, etc.

- Lack of traditional structure such as linear plots, climaxes in action, continuity of characterization, the breaking of rules of painting and music, etc.

Postmodern Literature

Kurt Vonnegut’s (1922-2007) Slaughterhouse Five is probably the most popular postmodern novel. In it, Billy Pilgrim, the main character in the novel is a soldier in World War II. He is captured by the Germans toward the end of the war. The novel jumps from his internment to his life both before and after the war. The reader is even retreated to bits of his life on another planet called, Tralfamadore.

The novel is in some ways autobiographical, even with the added elements of science fiction. Vonnegut personally experienced the Dresden bombing. “He suggests this fiction not only as an anti-war work, but also as an anti-narrative fiction. In Slaughterhouse-Five, he, by his key character Billy Pilgrim, shows that free will does not exist. Billy has been unstuck by time, and in general, humans cannot control the path which their life takes.”9

Vonnegut fulfills most of the expectations of postmodern work in this book. The work is a series of fragmented experiences, each as important and as banal as the last. None are really prioritized in terms of importance. Life in a prison camp is juxtaposed with life in a boring job after the war. The author creates a collage of American experience, a reflection of life in a country that is a superpower. He presents irony and absurdity as the products of a country thriving on consumerism and the illusory stability of wealth.

Other postmodern novels:

- Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace

- American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

- The Crying Lot by Thomas Pynchon

- White Noise by Don DeLillo

- Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon