4.2 REALIST PAINTERS

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877)

Gustave Courbet was born in Ornans in eastern France. He grew up in a middle class family, loved the rural countryside and was happy there. He left for Paris in 1839 and spent the next six years teaching himself how to paint by copying the paintings at the Louvre. He had several mistresses but never married. In 1849 he returned to Ornans to work in a studio provided by his father. Courbet has been regarded as the father of the Realist movement in 19th century art. He made a sharp iconographical break with Romanticism and tradition. He refused to become a professor and said that art could not be taught. This could have been due to the fact that he studied with a few teachers but always said that they had not taught him anything.

In social and political issues Courbet was far left. His paintings of the 1850’s were socially inflammatory because they were un-ideal and matter-of-fact, devoid of picturesque charm. At this moment the bourgeoisie had deprived the lower classes of the advantages they had won on the barricades of 1848. Universal suffrage was eliminated. Courbet’s work was seen as a threat to the shakily reestablished power of the middle class. Both realism and democracy were seen as threats to the status quo. Courbet’s artistic license and lack of decorum were equated with political lawlessness and radicalism. Courbet said that the goal of the Realist was to translate the customs, ideas, and appearance of his own epoch in his art and thus the social dimension automatically acquired importance.

In 1849 Courbet painted The Burial at Ornans, which was based on his great uncle’s funeral. The villagers, many of whom were probably his relatives, attend a burial, devoid of emotion. The grave digger waits his turn, the priest reads the services and the dog even seems bored. We see them from ground level, not elevated to a lofty position. These people are average, even ugly. They display no grief, but seem to be in attendance out of a sense of obligation. Some of the models were friends of the artist. There is no central focus; the attention is on all the figures which really means it is not on any of them. This is a democratization of all men, almost a monotonous repetition of the figures. Courbet’s Burial at Ornans was criticized because there was a lack of respect for the dead. It was said that Courbet had no faith in prayers and made fun of the life beyond. Note the large size of the canvas: the people were thought to be too large for their simplicity. Why was he painting monumental people that were so ugly and unimportant? This depicted the new working class which was considered dangerous. His work was rejected by the Salon, so he set up his own pavilion outside of the main exhibition hall and called it the Pavilion of Realism. This was the manifesto of the new Realist movement. Courbet used the palette knife to apply thick daubs of paint which created a rough surface. The public accused him of carelessness and brutality. The heroic, the sublime, and the terrible are not there, only the drab, the undramatized facts of life and death. His color choices are black, grey and white which constitutes a rejection of the brilliant color usage of the Academy. Although Courbet was often embattled with the critics over his work, he had secure official backing after 1855. When the new Impressionist movement began he did not understand their art and did not want to associate with it but the Impressionists took from him their impetus toward a modern style based on observation of the modern environment.

Compare the Burial at Ornans to The Burial of Count Orgaz painted by El Greco in 1586. Legend says that the count, who was generous to the church at San Tome, was buried by St. Stephen and St. Augustine, who are seen lowering his body into the tomb. His soul, the tiny, translucent spirit in the center of the painting, is cradled by an angel as he rises upward to meet the radiant figure of Christ. El Greco includes a self portrait with his hand raised and images of the local dignitaries who actually attended the funeral. He combines the real people attending the funeral with the unreal, divine vision of the supernatural.

Burial at Ornans, by Courbet 5:46 The Painter’s Studio, Courbet 8:18 If you receive an error with the links above, use the following links https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/courbet-a-burial-at-ornans, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/becoming-modern/avant-garde-france/realism/v/courbet-the-artist-s-studio-1854-55

In the huge work The Painter’s Studio Courbet places himself in the middle of the painting, hard at work. Compare to Velasquez’s work Las Meninas seen in figure 4.9. Here, at least, the artist is the central figure and has more respect. A nude model stands nearby to inspire him, though he is painting a landscape. She is probably supposed to represent Realism or Truth. The various other figures represent other forces that made up Courbet’s world. There is some doubt about what each of them is to represent. Courbet probably did not even know himself. This was not intended to be a real portrait, but an allegory. It could be divided into three sections: in the center is the artist and a woman and child, on the right are the intellectuals of Parisian life, and on the left are the lower classes from the provinces. Some of their presentations include an undertaker’s assistant, a small farmer forced to sell his land, a folksinger and a socialist thinker.

Compare Courbet’s work with Velazquez’s masterpiece, Maids of Honor. It is a portrait of the royal family Philip IV and his second wife Mariana of Austria, and it includes a self portrait of Velazquez with palette and brush in hand. The painter is wearing the uniform of the office of the court chamberlain with the keys of his office attached to his belt. He steps back to get a better view of his work. The king and queen are reflected in the mirror on the wall behind the artist. They were enchanted by the painting process and often watched him as he worked. Here the central focus is the royal family, not the artist.

The Stone Breakers was painted by Courbet in 1850. Its subject matter is the peasant performing monotonous tasks in seeming despair. We see only the facts, no political subject, no moral meaning, and no elevated purpose. It is a large canvas of an unimportant subject, and that was a political statement. Courbet was a champion for the masses, like Marx and other Socialists. There is no dramatic focus and even the lighting is democratic and bathes everything. The figures seem stiff and perhaps a little naïve. It portrays monumental grandeur, much like Michelangelo’s sibyls from the Sistine Ceiling, but there is no biblical overtone. He was hostile to religion saying it was oppressive.

Bonjour Mr. Courbet, sometimes called The Meeting, Self Portrait, was painted in 1854. It was to represent the meeting of two minds, or the meeting of two equals. Courbet, on the right, uses as much space on the canvas as the other two men and the dog combined. He compares himself to a wandering Jew sentenced to wander as punishment for insulting Christ. He sees himself as an apostle of realism, the intellectual giver of knowledge, a voyager with a purpose. These are figures in the landscape, outdoors. He still uses dark under painting, which the Impressionists later reject. This is a Rousseauian search for purity, simplicity and sincerity.

Honoré Daumier (1808-1879)

When we look at the work of Honoré Daumier we cross over to the work of a printmaker. He is known for his 4000 lithographs which were best known for getting him in trouble with the political leadership of the time. He wanted to become a painter, but his father was against it so he worked at various jobs, eventually working with booksellers. It was with the booksellers that he became interested in printing. Some of his prints caused him to run contrary to King Louis Philippe and others, so he was occasionally put into jail. Daumier followed Goya’s ideas and criticized the evils of society in general and the government in particular. He spent more than he earned and was always in debt. He painted for pleasure but could not earn enough to make a good living.

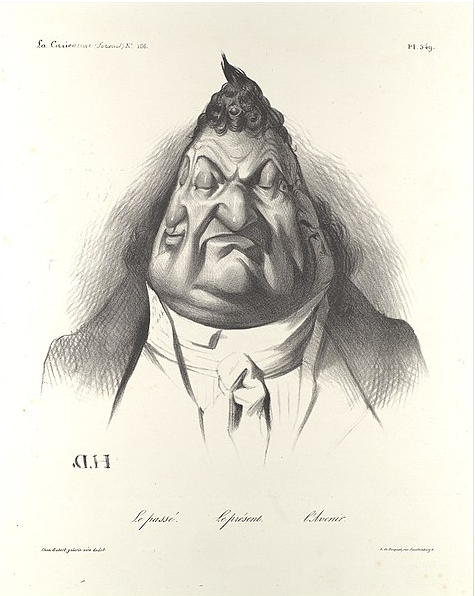

The Past, the Present, and the Future was created by Daumier for the January 9, 1934 issue of the weekly journal La Caricature. His politician, with a pointed head and the hair to match, seems able to see all time, but then why are his eyes closed? In truth he cannot see anything. He is self absorbed or perhaps sleeping instead of doing his duty.

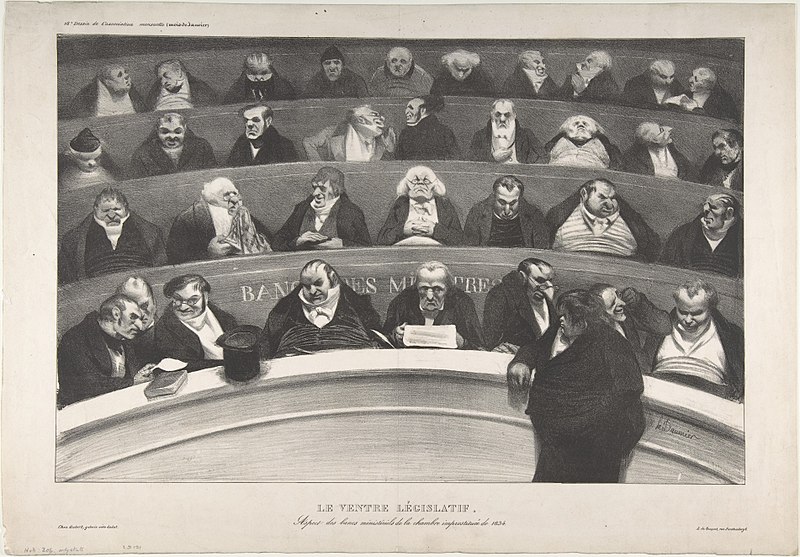

The Legislative Belly, or the Legislative Paunch depicts his politicians as caricatures, but they were recognized as individual members of the legislative body of the time. This could be compared to our political cartoons today. He produced an image of power, greed, and corruption in the political system. They are grossly obese, they gossip with each other, and they sleep instead of doing their duty. The lines of the composition reemphasize the folds of their bellies just to make sure you don’t miss it.

Rue Transnonain, The 15 of April 1834, shows anonymous figures sprawled around the wreckage of their commonplace dwelling. They are slaughtered victims of social forces beyond their control. This is a depiction of the murder of innocent people who were killed because the troops thought they had fired a bullet at them. Everyone in the apartment complex was killed. The gradations of black and white seem almost to be colors. The exposed bolster and the overturned chair are simply what they are and nothing more. This is a report of brutality and injustice. The light reveals not the eternal truths, but the actualities of death. It seems almost photographic.

There are three different versions of the work Third Class Carriage. Later in his life Daumier began to paint in oil in addition to working on lithographs. He seems to be saying that trains and the people who must use them to move from place to place are also important. These are people of modest means. They are alienated from each other. They are part of the urban modernity and have no connections. His figures are sketchy and sculptural and the paint is heavy on the surface of the canvas. His urban poor are exaggerated to the point that they almost become heroic. They are not simply representing the poor, but they seem to convey his feelings about the poor. In some ways he is caught between the Romantic depiction of the poor and his Realist beliefs about them.

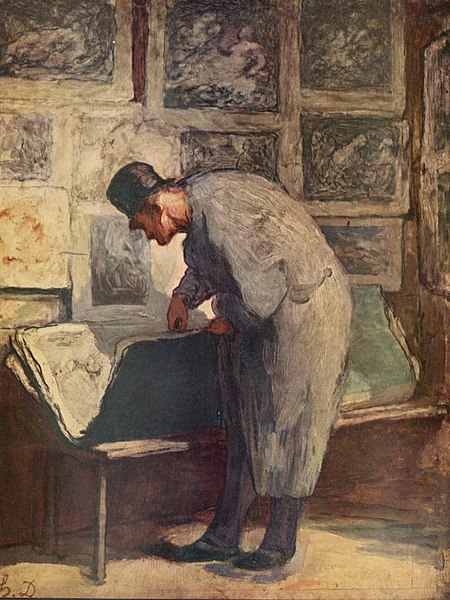

“During the 1850s and early 1860s, one of Daumier’s favourite subjects was the bourgeoisie (middle and lower middle classes) as print collectors. Sometimes Daumier paints them as merely curious passers-by gazing at displays of prints for sale or actually inside a dealer’s gallery. There are several oil versions similar to this one in which a solitary figure stands, sometimes rifling through sheets in a portfolio or, as in this work, looking at the prints on the wall, with the folder at his feet.”13

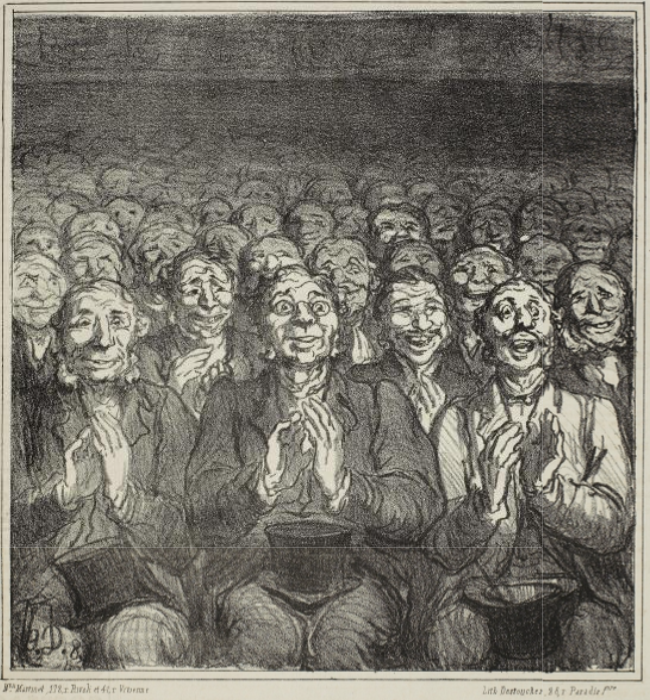

During the mid 1860’s Daumier’s popularity was declining and he had trouble paying his bills. In 1864 the magazine Le Charivari, which had dropped him from their staff several years before, offered him a new contract to draw satirical cartoons. Eventually the public began to show some interest in his works and he was able to make a living. figure 4.18, They Say Parisians are Hard to Please, is from ‘Theater Sketches’. Daumier often made fun of the rich and often drew favorable images of the poor. In this image he conveys the idea that the unwashed masses can enjoy theater as can the wealthy. He was never really acknowledged for his painting and was always thought of as a maker of prints.