1.1 INTRODUCTION TO THE AFRICAN CULTURES

Contemporary Africa consists of 54 countries, some of which are island nations (Cape Verde Islands, Comoros, Mauritius, Seychelles, São Tomé and Principe). Nations, however, are not synonymous with cultures. Very few countries consist of a homogeneous people. Rather, countries are made up of ethnic groups; some nations are occupied by a handful, while others include over 300. These groups are only occasionally isolated. Often a given town or city includes multiple ethnic groups in large numbers; at other times, a small cluster of one ethnic group’s members live as a minority within the territory of another. Members of one ethnic group may marry members of another, but self-identification is usually dependent on the culture’s inheritance system. In a patrilineal society, where inheritance is through the male line (i.e., from father to son), a child carries the ethnicity of its father. In a matrilineal society, where inheritance is through the female line (i.e., from a man to his sister’s son), a child carries his mother’s ethnicity.1

“Archaeology and physical anthropology show us human life originated in East Africa, yet our depth of knowledge relating to the earliest African history is limited either to those regions that had early writing systems (Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia) or to those that have hosted extensive archaeological research. Oral history supplies considerable information, but gaps remain. The dispersal of language families also supplies clues relating to population movements.”3

“Many parts of Africa were in direct or indirect contact with Europe and Asia. Egypt and some other parts of North Africa were incorporated into the Roman Empire and afterward continued to trade with the Mediterranean world. By the 8th century, Arab-speaking chroniclers recorded information about parts of eastern, northern and western Africa. Ethiopians travelled to Byzantium and the Middle East, as well as India, and Persians and Arabs traded with a number of East African coastal communities, as did the Chinese. The 15th century saw the beginning of European direct contact with West, then Central, then South and East Africa, as well as travelers’ accounts and documents written by Africans in European languages or Arabic.”4

“Even from the relatively little we know about African art in the distant past, we can see that substantial change has occurred over time. So what constitutes “traditional” African art, if change is consistent? Like many terms, it is imperfect, especially when contrasted with “contemporary” African art. The two words suggest division by time, but both artistic directions can coexist. “Traditional” African art is a response (whether it changes or not) to older patterns of function, such as traditional African religions, or use by traditional governmental institutions in palaces, or forms of protective and/or divinatory equipment. Traditional training is via formal or informal apprenticeship or self-education. Traditional patrons are individuals, male or female societies, priests, aristocrats or rulers.”5

““Contemporary” African art is distinguished by its diversions from the route of traditional art. The emphasis of its functions differs, emphasizing status display or advertising. Training can be by apprenticeship at some levels, such as sign painting, and can also result from self-education, but it often involves formalized training via a Western model: organized workshops, art school, or university specialization. Materials could be identical to those used by traditional artists, but technologies expand to incorporate acrylic or oil paint, glass, cement, resin, rubber, or other mediums that became available through foreign introduction. Contemporary patrons are usually individuals or corporate bodies—companies, hotels, government buildings—and need not be African at all. In a way, art made for export to tourists or overseas shops is contemporary art, because even if the artists are the same ones who make traditional art for local use, the shift to indirect patronage and accommodation to foreign preferences moves them toward the contemporary end of the spectrum.”6

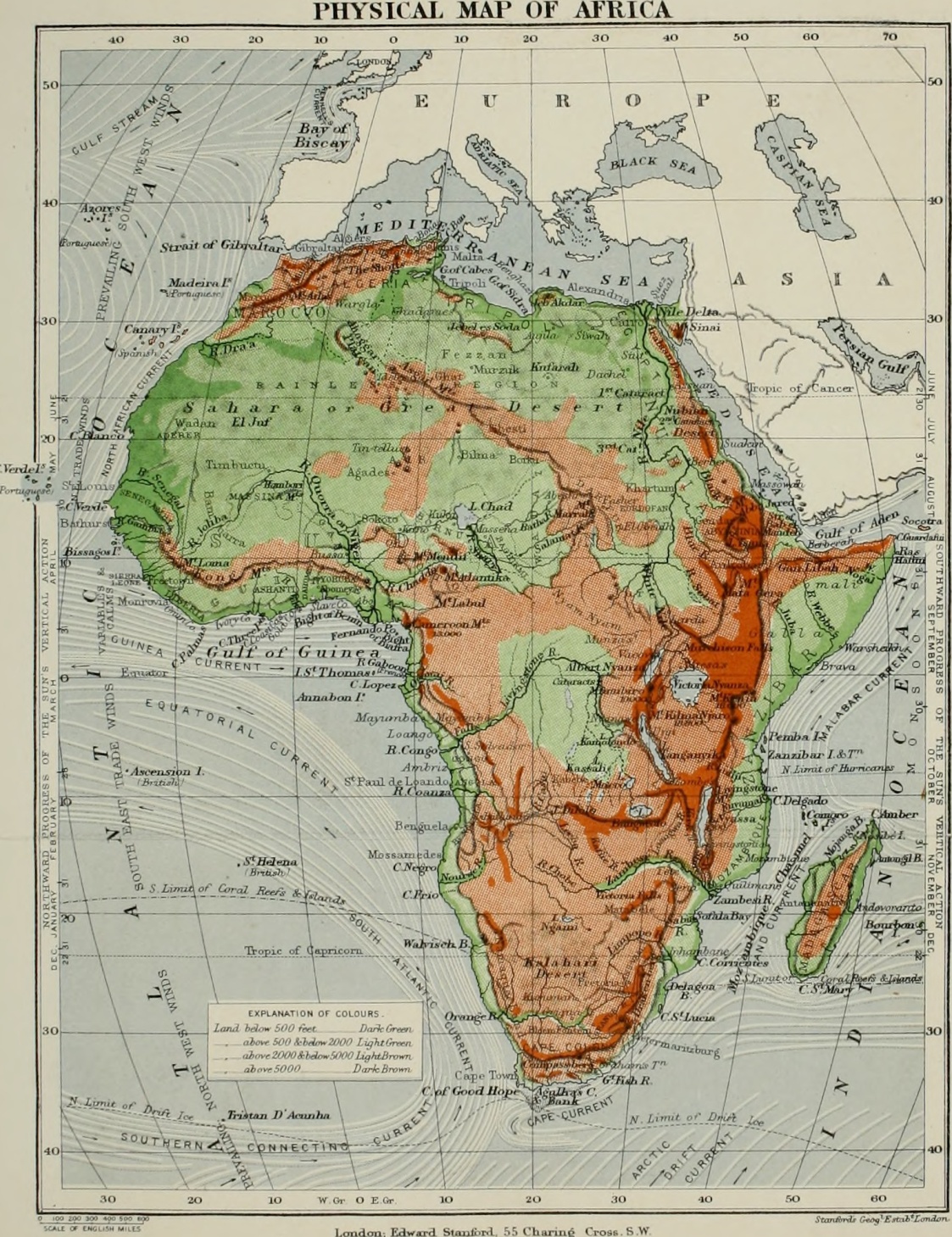

The African continent, second largest continent in the world, can be divided into climatic zones which play an important part in the cultures and ultimately the arts of the peoples who live there. By the 7th century CE. the areas bordering the Mediterranean Sea were heavily influenced by Islamic and Christian invaders. So, the art of North Africa, from Egypt to Morocco, and down the River Nile to Ethiopia, resembles the works of the Middle East and the Arab world. The immense Sahara desert separates the Islamic cultures in the north from the bush forests, brush, and grassy savannahs to the south. Between 7000 B.C.E. and 4000 B.C.E. the Sahara desert was covered with bush and grass and supported large numbers of animals. However, around 4000 B.C.E. the climate became extremely dry, most of the vegetation died, the animal populations dispersed, and the human populations followed the herds to milder areas.

South of the Sahara the land is slightly more hospitable. This area is sometimes called sub-Saharan Africa because it is beyond the desert barrier, which kept most travelers from crossing it to learn of the cultures further south. Although the leaders of savannah tribes were converted to Islam between the 7th and 14th centuries, many of the people were never completely converted because they lived in isolated areas. These cultures could not be subdued by the mounted Islamic horsemen, and instead they retained their individual religious beliefs. Large centralized kingdoms and empires grew in this area.

Further south of the savannah was the great tropical rain forest. In the thick forests the older religions and the art associated with them, flourished. The social conditions there were based on smaller clan units and family groups which were diffused in the dark, crowded forests. These areas receive up to 8 feet of rain per year and are infested by tsetse flies and mosquitoes which carry sleeping sickness and malaria.

Still further south is another strip of grassy savannah on the southern edge of the rain forest. These savannahs are not lush prairies, but are baked by six months of heat followed by six months of heavy rain which washes away the nutrients from the soil. The topsoil is not very productive and only produces a few crops. Further south is another large desert, the Kalahari, which is bordered by a small strip of scrub land now known as the Cape of Good Hope. The two large areas of desert served to keep most explorers out of the central areas of Africa for centuries. It was not until the Portuguese began exploring the coasts of Africa that the internal areas and cultures were encountered.

General Tendencies in African Religion

Islamic and Christian influences were pervasive in the northern areas of the continent and Africans practiced a variety of local religions. Religion was the basic guiding force in their lives. It was a “system of moral and spiritual teaching, without which the Africans could never have built and maintained their stable societies, their patterns of law and order, their standards of good and bad, their measures for bringing comfort to the sick and relief to the troubled and despairing.” 10 Although there were many variations, there were also many similarities in the way religion was practiced. Their gods were, for the most part, human. They were also well respected and even feared. There was a belief in a single High God from whom all things flowed. This god is not human, but is like energy, a sort- of life force. They believed that the dead do not really die, but that they join a community which includes the unborn, those living and those who have already died. They believed that the land belonged to that vast family, a community which encompassed everyone in a great continuum.

Most Africans believed that the High God once lived among humans, and that he left because of a mistake made by a human. The High God did not play a major role in the life of men, but left the work to a large collection of lesser gods who acted as intercessors. This was much like the Catholic Christian use of the saints who have power to act in God’s name and solve the problems of the world. The local gods may have been revered by one community or may be important to several. Africans were not interested in building large churches, and their temples and shrines were simple and humble. The altar might contain nothing more than a lump of wood or a piece of stone. It was these humble local shrines which became places where men and women could pray and consult the oracles. The local leaders who cared for the shrines were very important. They were often skilled in herbal medicine and practiced physical and psychological healing methods. Often they were to mediate with the gods, predict the future, settle disputes or feuds, and correct problems. The gods controlled the mysteries of nature and could give help, but the ancestors guaranteed the survival and prosperity of the communal group. If the ancestors were honored they could help the community to prosper, if they were ignored, they could cause great harm. Ancestor cults assured law and order in the traditional rites of passage such as birth, puberty, marriage, and burial. They also controlled the economy of the village through the “secret societies” which were executors of the ancestral laws.

Basic characteristics of African art

Line:

Two-dimensional artworks may include actual, contour, directional, and implied lines. Actual lines are created by the artist’s hand movements, and are the marks made by moving a tool from one point to another. They may be curved or straight. The latter can be horizontal (parallel to the top and bottom of the surface), vertical (parallel to the sides of the surface), or diagonal. Lines have varying width and can be light or dark depending on the pressure on the tool. Lines, like all of the elements of designs, have their own character and personality. A light, looping line may have a carefree or sensual feel, while verticals and horizontals create a sense of stability. If an artist wants to insert a feeling of motion or power, diagonals indicate action. While lines can simply indicate a mark, they can also describe an object–an outline. Placing them close together and crossing them may produce the effect of shade, or they may be rhythmically spaced to create a pattern. Contours indicate an object’s edges, but they do not have to be actual lines where one object’s edge is perceived against a background or against another object, that non-drawn edge is considered a line, and can have a personality like a drawn line. Likewise, a limb or other section of an object has contours, but the whole of the limb can also be considered a non-drawn line describing a direction. Lastly, there are invisible lines that are psychological in nature; when two figures in an artwork look at each other, or a figure looks at a thing, there is an invisible sightline between the two.11

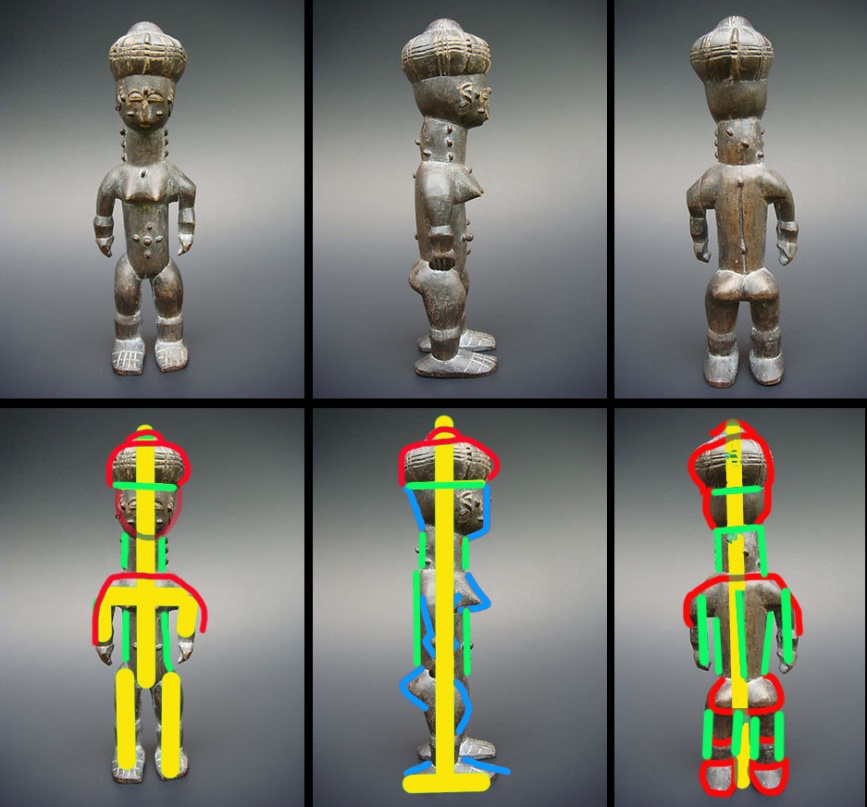

Line in three dimensional objects

In this type of art we are normally talking about the lines produced by the edges of the forms. Notice the lines created by drawing on a picture of the image below.

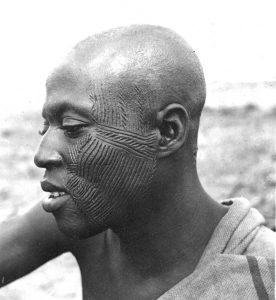

Abstract designs

in the form of surface texture and decoration often had a deep spiritual significance in African art. “Geometric patterns were known to have had mystic powers so important that they reappeared in many forms, including ceremonial scarring and tattooing on bodies and faces. Other patterns represented the more ordinary spirits that lived in such material objects as fabric and yarn”.14 At times the sculpture is so completely covered with lines that the shape of the work is denied.

Texture

Three dimensional texture is produced both by the material and the artist’s working of the material. Some artists create works with all-over textures, while others contrast smooth expanses with areas of submerged or raised surfaces. In African traditional art, texture also frequently results from the use of multiple mediums in one piece. A wooden sculpture, for example, might have a feathered headdress, be dressed in actual cloth, and wear a beaded necklace with metal earrings. These all provide varied tactile sensations for those allowed to touch the artworks. Even without actual touch, viewers are experienced in the sensations produced by those materials, and can conceptualize what the surfaces feel like.

Shape

Often a prescribed tradition dictated the basic shape of an object, but the artist was allowed originality within that form. Most sculpture was made from a single piece of wood which was selected from a live tree. Few works were pieced or jointed. The cylindrical shape of the tree limb dictated the finished shape of the sculpture. The sculpted piece conformed to the original shape of the available material. This convention often resulted in abstracted shapes, with surfaces broken into simple, flat planes which emphasized the parts of the human body. The human head was believed to be the seat of the spirit or personality and the center of power. Large heads on sculpture could have originated from this idea.

Space

Consider this bronze plaque from Benin as an attempt to create some degree of illusionistic space. There is some overlapping of the figures and the arms of the oba (king) reach out into the foreground. It is possible that this may have been caused by the possession of European books by the artists after the Portuguese began trading for slaves in the area, though this is a controversial hypothesis. Notice the hierarchical scaling used in the plaque depicting the small guards below the elbows of the oba. This means that the most important person is depicted as the largest person. The background of the plaque is lightly incised with dots and floral forms, which do not create the illusion of real space, but instead block the viewer’s eye from moving backward into the distance.

By definition, two-dimensional art cannot have actual depth. However, artists often try to create the illusion of depth through a variety of techniques. One of the simplest is overlapping. The position of two equally-sized shapes on a flat surface can also suggest a distance relationship–things at the bottom seem closer to the viewer than things at the top do. The rock painting seen in figure 1.xx includes a dark cow at the top that no other cows overlap. Nonetheless, because it is at the top of the composition, we read it as being farther away. If two objects are the same size in the real world, and one is larger in a painting, our real-world cues can suggest the larger one is closer to us, depending on what other cues are present.21

Medium-The materials available for the artist in Africa included ivory; some stone; metals, including gold, silver, bronze, iron and copper; and wood. Most sculpture was created in easily accessible wood. The tree was specially chosen before cutting, and a prayer of thanksgiving was offered for its use. Wood was carved using the hand held axe and chisel. Most artisans developed a rhythmic, swinging movement, turning the wood with one hand and shaping it with the other hand while balancing it between his feet. Although the wood was intended to “return” to the earth, it was often coated with residue from the bottom of the dye pit, wrapped in banana leaves and hung in the smoke from the fire.

Associated values

- Secrecy– Much of the art created in African cultures was not to be seen by the common man, or not to be seen very often. Ancestor sculptures were hidden away to be brought out only on special occasions. The stools of the king were sacred and were not for public view. Masks and fetishes might be used on special feast days or to initiate new young people into the secret societies. The diviner’s tools were only to be used by the oracle, and not to be understood by all. Each piece of art had its intended purpose, but it was not public art. Africans did not create art museums for public display and collection of artifacts because their art was too much a part of their religious culture.

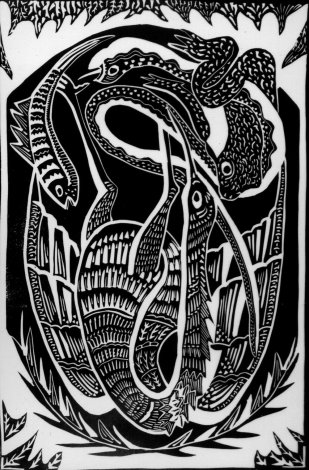

- Use of animals and their behavior– The people of Africa lived in association with nature. Their economics revolved around farming and hunting which depended in part on the knowledge of animals and animal behavior. Their art placed a strong emphasis on the appearance of animals, just as their religious myths revolved around animals. “It was believed in some African societies that there was a correspondence between human and animal characteristics, and some chose as their symbol the animal they most resembled, and their behavior conformed to this symbolic pattern”. 22 For this reason we will often see animals or half human half animal creatures in African art.

- Permanence/ transience. Art in permanent mediums was found in centralized kingdoms in which the ruler had imposed order. “The use of form of expression based on a close observation of animals, and their behavior in their environment was a constant feature of the art for eight thousand years and explains its long continuity, but the adaptation of these forms to the poetry and theatre of constantly changing conditions explains their variety and vivacity. The necessity for adaptation also explained why the art was made of transient materials and why it was kept out of sight until it was needed in a theatrical expression of what was of most contemporary and immediate.”23

Economic and Social influences

African influence on European culture began in the middle ages. The crusaders brought western adventurers in contact with Islamic trade and with the African kingdoms to the south. They sought pepper, ivory, gold and slaves for European markets as early as the 13th century. It was the search for gold by prominent European banking houses after the closing of the Hungarian mines, which drew westerners into Africa. Portuguese sailing vessels explored the coast of Africa beginning in the 15th century, and as their maritime skills improved, they sailed further and further south, aiming to more easily approach land south of the formidable Saharan Desert.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama took his ship through the South Atlantic and around the Cape of Good Hope and found tall stone towns populated with wealthy, intelligent people who knew as much about charts and compasses as he did. In the early 16th century Pope Leo X learned from a captured Moor that the legendary city of Timbuktu, in the kingdom of Mali, had so many scholars that its merchants made more profits from the sale of books than from any other commodities.24

Dutch explorers came through the interior rain forests of Nigeria and found the city of Benin. They reported that its king lived in a palace as large as the city of Haarlem in the Netherlands.25 Few explorers understood the African languages enough to ask questions about what they saw. Many wild tales and invented stories filtered back to western society, but very few valid studies or histories were recorded. Europeans believed legends and rumors were true for centuries.

It was the trafficking of human slaves that had the greatest economic influence on the African peoples. In 1452 and 1455 Pope Nicolas V issued a series of papal bulls that granted Portugal the right to enslave sub-Saharan Africans. Church leaders argued that slavery served as a natural deterrent and christianizing influence to “barbarous” behavior among pagans. In 1526 Portuguese sailors brought the first of 10 million slaves from Africa to the Americas.26 They were taken to work in the mines and factories to produce cotton, rum, and sugar in the new world.

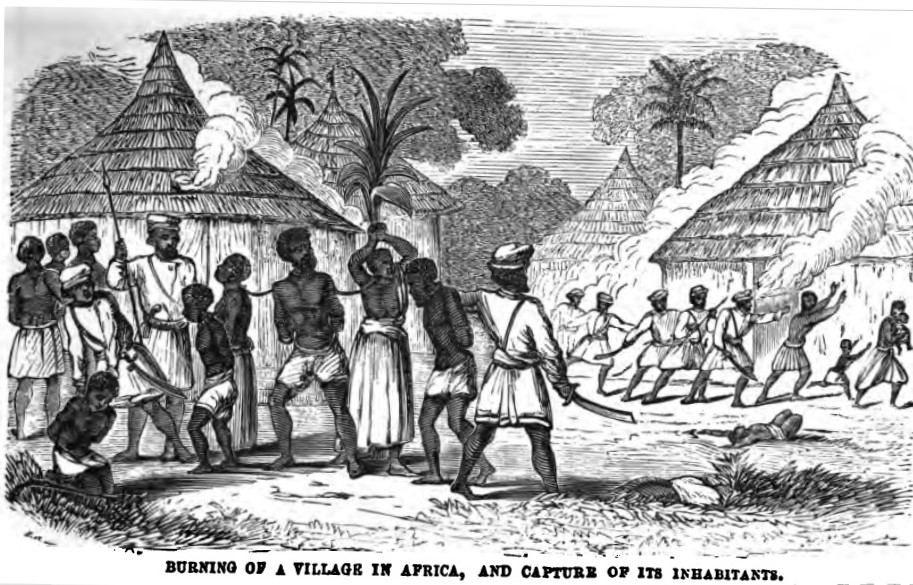

“Historians have debated the nature and extent of European and African agency in the actual capture of those who were enslaved. During the early years of the transatlantic slave trade, the Portuguese generally purchased Africans who had been enslaved during tribal wars. As the demand for enslaved people grew, the Portuguese began to enter the interior of Africa to forcibly take captives; as other Europeans became involved in the slave trade, generally they remained on the coast and purchased captives from Africans who had transported them from the interior. Following capture, the abducted Africans were marched to the coast, a journey that could be as many as 300 miles. Typically, two captives were chained together at the ankle, and columns of captives were tied together by ropes around their necks. An estimated 10 to 15 percent of the captives died on their way to the coast.”28

“The slave trade had devastating effects in Africa. Economic incentives for warlords and tribes to engage in the trade of enslaved people promoted an atmosphere of lawlessness and violence. Depopulation and a continuing fear of captivity made economic and agricultural development almost impossible throughout much of western Africa. A large percentage of the people taken captive were women in their childbearing years and young men who normally would have been starting families. The European enslavers usually left behind persons who were elderly, disabled, or otherwise dependent—groups who were least able to contribute to the economic health of their societies.”29

Some information in this text was taken from the OER Commons book written by Kathy Curnow, The Bright Continent: African Art History, Chapter 1, CC BY SA 4.0, https://www.oercommons.org/courses/the-bright-continent-african-art-history/view