9.7 Contemporary Aesthetics – Bell

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section you will discover:

- How the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century saw a radical change in artistic expression, from the representational to the abstract, from the harmonious to the discordant, from the intention of the artist to the impact on those perceiving the art.

- How Clive Bell’s formalism gave us a way to appreciate a work of art in and of itself without considering its social, historical, or intentional contexts.

How are we to make sense of modern art?

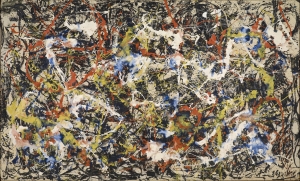

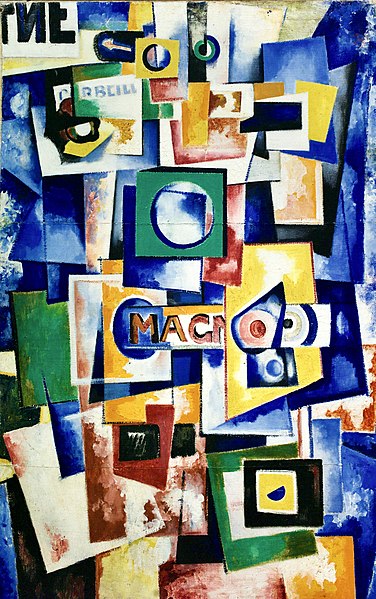

Beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries the western tradition of art went through some radical changes. Rapid industrialization and the violence of World War I prompted artists to radically review every assumption underpinning art. They focused more on the inner self through highly personal perspectives, rather than accurately depicting the external world. Across visual arts, music, literature, etc., artists began to reject traditional styles, techniques, and forms. They replaced traditional forms with such things as atonality in music, stream-of-consciousness writing, abstract painting. Artists moved away from representing or depicting the world and nature, instead focusing on reducing art to basic elements like line, color, sound. The focus of art changed to its creation rather than to its ability to reproduce the world. It also turned inward. Surrealism, expressionism, and Freudian ideas led artists to try expressing inner psychological states, the subliminal, and dreams rather than external reality. Stream of consciousness developed in literature, atonality, and dissonance in classical music. More and more the formerly separate genres of art began to be combined. Stravinsky combined ballet and orchestra. Cubist paintings incorporated letters and everyday materials. Prominent mixed-media works emerged. Also, modern art attempted to shock bourgeois sensibilities through experimentation, novelty and going against convention.

The most important encouragement of this new art is to engage with it actively and openly. Modern art often asks the viewer to meet it halfway rather than passively consuming it. There are no right or wrong responses if you’re sincerely trying to connect with the art. Over time, its complexities can reveal themselves.

Bell

Clive Bell was an English art historian who offered a new aesthetic approach to understanding these changing artistic trends.

Bell was an advocate of formalism. Formalism is the study of art that analyzes and compares form and style. Its focus is also on the way artistic objects are made and their purely visual or material aspects. In painting, formalism emphasizes compositional elements such as color, line, shape, texture, and other perceptual aspects rather than content, meaning, the artist’s intentions, or a work’s historical and social context. At its extreme, formalism in art history posits that everything necessary to comprehending a work of art is contained within the work of art. The context of the work, including the reason for its creation, the historical background, and the life of the artist—these are all considered by formalism to be of less importance than the actual work itself.

In his Art (1913) Bell attempted to offer an aesthetic theory responsive to an emerging tendency toward abstraction in modern art. Contrary to Plato, Bell argues that visual art was not about imitation (mimesis) but about form. Within each work of art there must be found a visual formal structure. Famously opening his work by saying that “either all works of visual art have some common qualities, or when we speak of works of art, we gibber,” Bell argued that what all visual art shares is significant form. By this he meant that all genuine art contains an arrangement of line, color, space, and vectors that causes in the viewer an aesthetic emotion. He freely admits that such an experience is subjective. What else could experience be? But whereas initially a work of art might give rise to a diverse number of reactions, educating viewers in its significant form can eventually bring viewers into a convergence of understanding.

Bell argued that art refers only to its own formal reality and not to anything outside itself. Art should no longer be considered as depicting the external world but as creating new forms and patterns that take on independent aesthetic meaning. In other words, abstract qualities interact within a painting or sculpture to open an isolated sphere of completely self-referential aesthetic actuality separate from any external reality. Form has content in-itself for Bell. This distinguishes art from mere representation of pre-existing things.

Bell gave theorists terminology and principles to highlight formal qualities and viewers’ aesthetic responses as the definitive markers of art rather than judging art socio-politically or in terms of how well it presented the natural world. This approach remains influential in studying modern abstract and non-representational art to this day.

Work Cited

Pollock, Jackson Convergence, (1952), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convergence_%28Pollock%29. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Robert Fry, Portrait of Clive Bell (c. 1924), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clive_Bell. Public Domain. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Amadeo de Sousa-Cardoso (1887-1918), The Green Square Ascension and the woman with the violin (c.1916), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Green_Square_Ascension_and_the_woman_with_the_violin%28c.1916%29_-_Amadeo_de_Sousa-Cardoso_%281887-1918%29_%2849588056691%29.jpg. CC BY 2.0. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.