9.1 Why Should We Think About Art?

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section you will discover:

- How the study of Aesthetics can enrich your life.

- That Aesthetics is also concerned with the betterment of society.

- That we may have a unique faculty of mind that helps us recognize beauty.

- That judgments of beauty may be more than just personal opinion or preference.

The study of aesthetics can improve our lives

There are good reasons not just to experience art and beauty but to think about our experience of them. For some, there are very pragmatic reasons to study aesthetics. The study can serve as preparation for a career involving art or design. For careers involving curation, art criticism, arts management, etc., an aesthetics foundation helps strengthen insight and analysis skills.

But for most of us, aesthetics can enrich our personal experience of art. Imagine a scenario where you take your four-year-old niece to the art museum. You both look at the same painting, yet you as an adult will likely have a significantly different experience from that of your niece. Perhaps you have some knowledge of the artist, his or her period, the genre in which s/he worked. You can understand how the artist uses form, light and shadow, depth, and perspective. Your niece may find a painting pretty or boring or scary, but your knowledge about art is likely to give you a greater appreciation of the work in front of you.

Aesthetics can help us develop a deeper understanding and appreciation of art, beauty, and creative expression. Studying aesthetics exposes us to theories about what makes something artistic, beautiful, or meaningful. This can enhance how we experience and interact with art and culture. Aesthetics also asks us to think critically about perception, taste, and judgments of value. It encourages us to think deeply about subjective vs. objective criteria in art criticism and evaluation. It prompts us to reflect on our own tastes and why we value certain creative works.

Does art have social or merely personal value?

There are good arguments on both sides of this complex issue. While much art is created for personal expression and fulfillment, suggesting it has intrinsic personal value for the artist and that creating art can be meaningful on an individual level, there also is often a strong social dimension to artistic creation. Aesthetics can help us gain new insights into history, society, and the human condition. By studying aesthetics, we can better understand how art and creative expression have evolved through history, as well as how they relate to economic, political, and social contexts. This provides insight into different cultures and time periods.

Art also often communicates ideas, emotions, and perspectives that can resonate with others. Sharing art is a way to connect people and spread new ways of thinking. In this sense, it has social value. Certain types of art like protest songs, political theater, and social realist painting are expressly created to comment on society and encourage social change. This implies art can have a direct social impact.

Over time, some works of art accrue broader social importance as they become cultural touchstones or icons. Consider the Statue of Liberty, a clear example of public art with immediate political meaning. Compare that to a new piece of statuary that might have been erected in your downtown. It likely has yet to attain the importance or social meaning that Lady Liberty immediately knew. But over time, this local piece could become quite meaningful. Yet that meaning develops gradually through collective experience. Art for its own sake, without a specific social motive, can still have social ripple effects by inspiring creativity in others. Its social value may be indirect.

Overall, there are reasonable arguments that art has both inherent personal value and wider social value. The two are not mutually exclusive. A balanced view is that art often combines personal creative impulses with a social dimension, in varying degrees. But the long-term value of any specific work is ultimately determined by its unique cultural life and reception.

How does our experience of beauty differ from other kinds of experiences?

Philosophers of aesthetics also like to discuss how our experience of beauty differs from other kinds of human experiences. Beauty often elicits an emotional response in us — we may feel awe, joy, appreciation, etc. when encountering something beautiful. Other kinds of experiences may not have the same emotional impact. Also, judgments of beauty are more subjective than other judgments. While we may agree on logical truths, for example, what is considered beautiful is more dependent on personal taste. Beauty is often tied to objects and experiences that we find intrinsically valuable, not just instrumentally valuable. We tend to value beauty for its own sake, not because it achieves some practical aim.

The experience of beauty seems to have an immediacy and felt intensity that other experiences may lack. There is often an ineffable quality to beauty that goes beyond rational description and analysis. Beauty offers a type of pleasure and fulfillment that seems distinct from our satisfaction of other kinds of desire or the achievement of our goals. It is a disinterested pleasure, i.e. a pleasure in and of itself without any other purpose and focused on pure appreciation. Experiencing beauty can change our perspective and expand our sense of meaning in life. It highlights the intrinsic value of human existence beyond mere utility.

In the end, the unique subjective feeling that beauty evokes, its focus on intrinsic value, and its power to shift our perspective in some important ways all make it a unique human experience.

Is beauty objective?

Do we each experience art in a unique way, so that a work’s beauty lies only in our subjective opinion of it, or is there a basis for believing beauty is objective, can be understood more collectively, that it lies in the work of art itself? There have been reasonable arguments on both sides of this issue.

Those who argue beauty is primarily subjective suggest that beauty is largely in the eye of the beholder. What is considered beautiful varies greatly across individuals and cultures. This suggests beauty is a subjective matter of personal taste and social/cultural norms. An examination of what various cultures across the world have considered beautiful might suggest there are no universal standards or features that define beauty. Attempts to identify objective proportions, symmetries, etc. tend to break down with counterexamples. Finally, the experience of beauty involves personal emotions, memories, preferences, etc. This is a subjective psychological reaction.

Those who suggest there might be some arguments for beauty having objective elements would remind us that while personal tastes differ, there seem to be certain universal aesthetic principles, e.g., symmetry, color, harmony, etc. that broadly underlie perceptions of beauty across cultures. In addition, studies have found that people from diverse backgrounds tend to agree on assessments of physical attractiveness, suggesting shared criteria. They note that elements like mathematical symmetry, geometric proportions, and signs of being healthy and whole objectively contribute to perceptions of beauty, even if some subjectivity remains. Lately as well there have been studies in neurology that suggest that there may be a common neurological basis for our response to beauty.1

Overall, perhaps the most reasonable position is that beauty has both objective and subjective elements. There are certain universal principles and biological responses to beauty, but how we apply them is filtered through subjective experience. But reasonable minds can disagree on where the balance lies between the two. Beauty likely has no fully objective or fully subjective explanation.

___________________

1 Consider for example Kawabata H, Zeki S., “Neural correlates of beauty.” J Neurophysiology. 2004 Apr; 91(4):1699-705 which found that viewing different categories of beautiful visual images (such as landscapes, faces, artwork) commonly activates the orbitofrontal cortex, supporting the idea of a common neural circuitry for perceiving beauty.

Works Cited

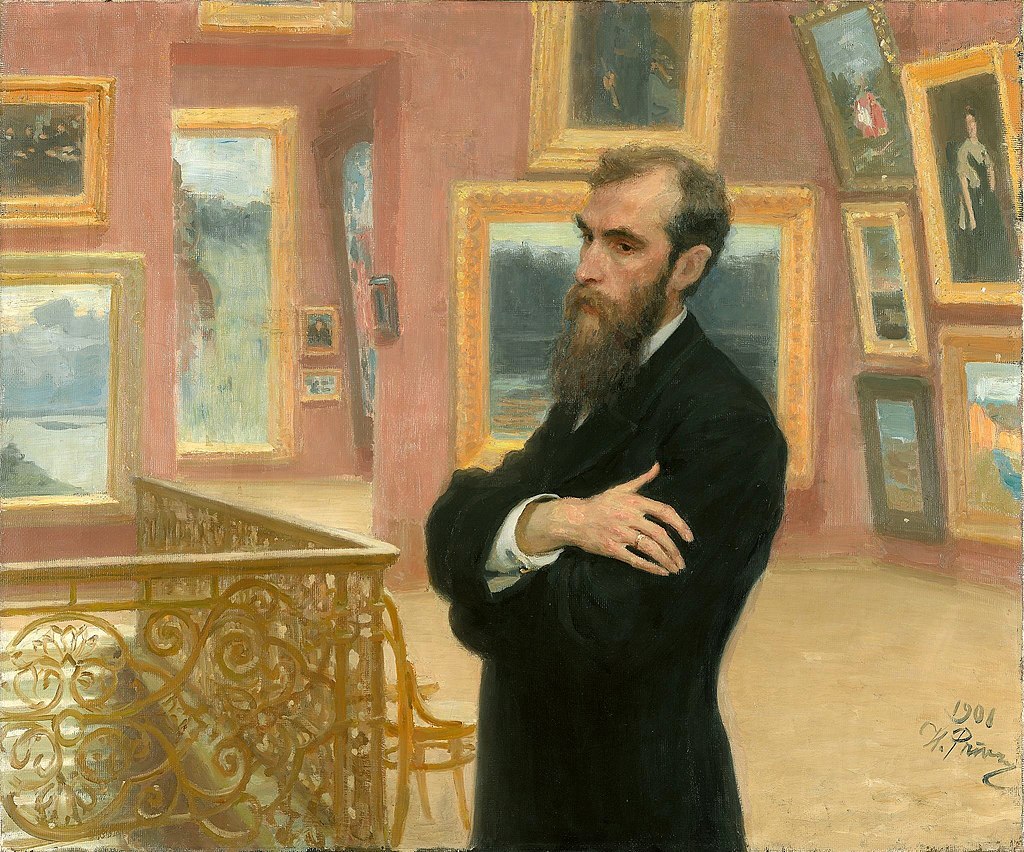

Portrait of Pavel Mikhailovich Tretyakov, founder of the Gallery, www.wikipedia.org, is in the Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_valuation#:~:text=Art%20valuation%2C%20an%20art%2Dspecific,play%20a%20part%20as%20well. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.