4.2.5 Perspectivism

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section you will discover:

- How Friedrich Nietzsche’s “perspecitism” came to reject Kant’s certainties.

- How Nietzsche left epistemology at the end of the 19th century again in an age of skepticism.

- Strenghts and weaknesses of Nietzsche’s perspectivism.

The crucial thing is to find a truth that is true for me. – Soren Kierkegaard

Previous theories of knowledge that we have discussed have been objectivist theories. Each of these previous theories in their own way suggested that there existed some objective truth. Epistemological Relativism is very different. It is a subjectivist theory of knowledge, where truth claims are dependent on the beliefs of the society or individual. Friedrich Nietzsche pioneered this theory of knowledge by standing on the shoulders of objectivist thinkers like Kant, who cracked the door open for relativists like Nietzsche to step through.

Nietzsche believed that earlier philosophers like Plato or Kant who claimed to offer us objective, universal knowledge of the truth failed to recognize that their theories were conditioned by their own desires and “primitive” needs.

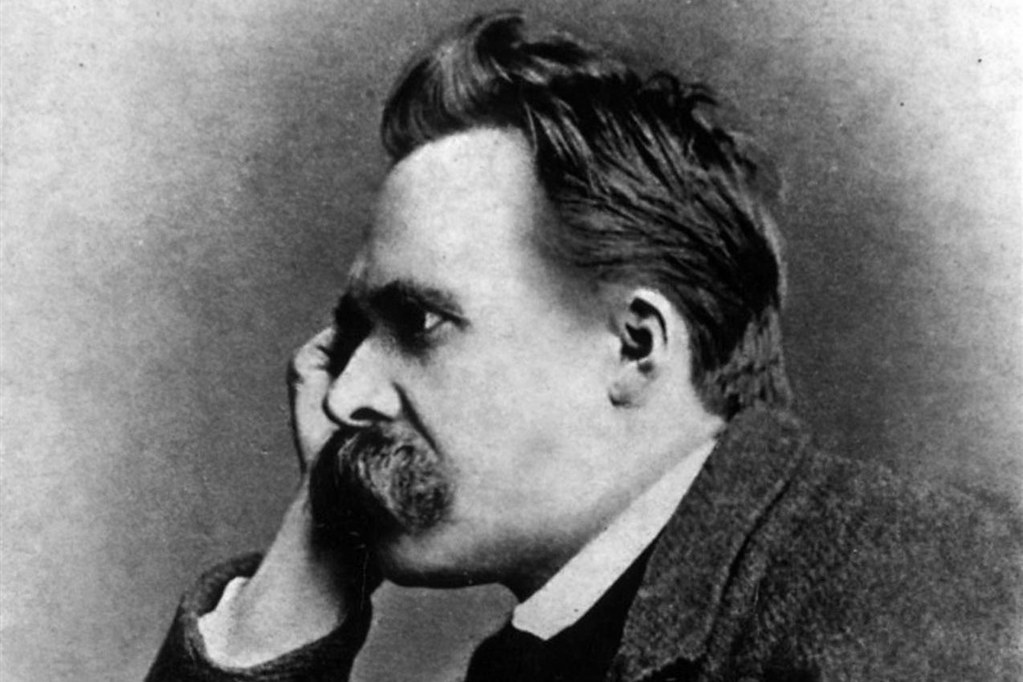

Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844–1900) was a German philosopher, cultural critic, composer, poet, writer, and philologist whose work exerted a profound influence on modern intellectual history. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person ever to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24. Nietzsche resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900.

Nietzsche’s Perspectivism

One of Nietzsche’s most important ideas is called perspectivism. Perspectivism is the epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing it. While perspectivism does not regard all perspectives and interpretations as being of equal truth or value, it holds that no one has access to an absolute view of the world cut off from perspective. Instead, all such viewing occurs from some point of view which in turn affects how things are perceived. Rather than attempting to determine truth by correspondence to things outside any perspective, perspectivism thus generally seeks to determine truth by comparing and evaluating perspectives among themselves. (“Perspectivism,” Wikipedia)

We can see from this that Perspectivism is a form of Epistemological Relativism in that it suggests that we all “construct” our worldviews in ways unique to our minds and our values.

Nietzsche believed that earlier philosophers like Plato or Kant who claimed to offer us objective, universal knowledge of the truth failed to recognize that their theories were conditioned by their own desires and “primitive” needs. A precursor to the development of psychology in the early 20th century, Nietzsche argued that our world views are often conditioned by our unrecognized traumas and passions.

One of the key concepts in Nietzsche’s perspectivism is interpretation. According to Nietzsche, interpretation is something that humans must do. Interpretation is how we understand our world and give our life meaning. Because there are no universal truths, everything gets interpreted through our subjective perspective.

Excerpts from Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil

In his best-known book, Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche outlines his views on knowledge.

In what follows,

What does Nietzsche say influences philosophers in their thinking?

What does he say lies behind all logic?

Having kept a sharp eye on philosophers, and having read between their lines long enough, I now say to myself that the greater part of conscious thinking must be counted among the instinctive functions, and it is so even in the case of philosophical thinking; one has here to learn anew, as one learned anew about heredity and “innateness.” As little as the act of birth comes into consideration in the whole process and procedure of heredity, just as little is “being-conscious” opposed to the instinctive in any decisive sense; the greater part of the conscious thinking of a philosopher is secretly influenced by his instincts and forced into definite channels. And behind all logic and its seeming sovereignty of movement, there are valuations, or to speak more plainly, physiological demands, for the maintenance of a definite mode of life For example, that the certain is worth more than the uncertain, that illusion is less valuable than “truth” such valuations, in spite of their regulative importance for US, might notwithstanding be only superficial valuations, special kinds of niaiserie, [silliness] such as may be necessary for the maintenance of beings such as ourselves. Supposing, in effect, that man is not just the “measure of things.”

The falseness of an opinion is not for us any objection to it: it is here, perhaps, that our new language sounds most strangely. The question is, how far an opinion is life-furthering, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps species-rearing, and we are fundamentally inclined to maintain that the falsest opinions (to which the synthetic judgments a priori belong), are the most indispensable to us, that without a recognition of logical fictions, without a comparison of reality with the purely imagined world of the absolute and immutable, without a constant counterfeiting of the world by means of numbers, man could not live—that the renunciation of false opinions would be a renunciation of life, a negation of life. To recognize untruth as a condition of life; that is certainly to impugn the traditional ideas of value in a dangerous manner, and a philosophy which ventures to do so, has thereby alone placed itself beyond good and evil.

In the next section, why does Nietzsche say that philosophers are being dishonest? What biases does he accuse them of?

Nietzsche compares philosophers to lawyers (he uses the term advocates). Why does he make this comparison? Is this a compliment to philosophers?

That which causes philosophers to be regarded half-distrustfully and half-mockingly, is not the oft-repeated discovery how innocent they are—how often and easily they make mistakes and lose their way, in short, how childish and childlike they are, —but that there is not enough honest dealing with them, whereas they all raise a loud and virtuous outcry when the problem of truthfulness is even hinted at in the remotest manner. They all pose as though their real opinions had been discovered and attained through the self-evolving of a cold, pure, divinely indifferent dialectic (in contrast to all sorts of mystics, who, fairer and foolisher, talk of “inspiration”), whereas, in fact, a prejudiced proposition, idea, or “suggestion,” which is generally their heart’s desire abstracted and refined, is defended by them with arguments sought out after the event. They are all advocates who do not wish to be regarded as such, generally astute defenders, also, of their prejudices, which they dub “truths,”—and very far from having the conscience which bravely admits this to itself, very far from having the good taste of the courage which goes so far as to let this be understood, perhaps to warn friend or foe, or in cheerful confidence and self-ridicule. The spectacle of the Tartuffery of old Kant, equally stiff and decent, with which he entices us into the dialectic by-ways that lead (more correctly mislead) to his “categorical imperative”—makes us fastidious ones smile, we who find no small amusement in spying out the subtle tricks of old moralists and ethical preachers. Or, still more so, the hocus-pocus in mathematical form, by means of which Spinoza has, as it were, clad his philosophy in mail and mask—in fact, the “love of his wisdom,” to translate the term fairly and squarely—in order thereby to strike terror at once into the heart of the assailant who should dare to cast a glance on that invincible maiden, that Pallas Athene:—how much of personal timidity and vulnerability does this masquerade of a sickly recluse betray!

It has gradually become clear to me what every great philosophy up till now has consisted of—namely, the confession of its originator, and a species of involuntary and unconscious autobiography; and moreover that the moral (or immoral) purpose in every philosophy has constituted the true vital germ out of which the entire plant has always grown. Indeed, to understand how the abstrusest metaphysical assertions of a philosopher have been arrived at, it is always well (and wise) to first ask oneself: “What morality do they (or does he) aim at?” Accordingly, I do not believe that an “impulse to knowledge” is the father of philosophy; but that another impulse, here as elsewhere, has only made use of knowledge (and mistaken knowledge!) as an instrument. But whoever considers the fundamental impulses of man with a view to determining how far they may have here acted as inspiring genii (or as demons and kobolds), will find that they have all practiced philosophy at one time or another, and that each one of them would have been only too glad to look upon itself as the ultimate end of existence and the legitimate Lord over all the other impulses. For every impulse is imperious, and as such, attempts to philosophize. To be sure, in the case of scholars, in the case of really scientific men, it may be otherwise—”better,” if you will; there may really be such a thing as an “impulse to knowledge,” some kind of small, independent clockwork, which, when well wound up, works away industriously to that end, without the rest of the scholarly impulses taking any material part therein. The actual “interests” of the scholar, therefore, are generally in quite another direction—in the family, perhaps, or in money-making, or in politics; it is, in fact, almost indifferent at what point of research his little machine is placed, and whether the hopeful young worker becomes a good philologist, a mushroom specialist, or a chemist; he is not characterized by becoming this or that. In the philosopher, on the contrary, there is absolutely nothing impersonal; and above all, his morality furnishes a decided and decisive testimony as to who he is, —that is to say, in what order the deepest impulses of his nature stand to each other. (Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Project Gutenberg)

The Death of Absolutes

Nietzsche’s relativism has broad-reaching implications for the notion of absolute truth. If there is no true objective standard, then nothing is absolute, including God. Nietzsche observed that Christianity was losing its central place in Western culture and proclaimed that “God is dead…and we killed him.”

Moreover, by this claim, he meant not only that the God of religion no longer made sense, but that any effort to discover absolute truth was folly. Nietzsche claimed the death of God would eventually lead to the loss of any universal perspective on things and any coherent sense of objective truth. Nietzsche rejected the idea of objective reality, arguing that knowledge is contingent and conditional, relative to various fluid perspectives or interests. This leads to constant reassessment of rules (i.e., those of philosophy, the scientific method, etc.) according to the circumstances of individual perspectives. This view has acquired the name perspectivism.

In the following excerpt from The Gay Science, Nietzsche warns of the coming cultural revolution.

Why does Nietzsche use the figure of a madman as the one seeking God?

Why does the madman say that God is dead and that we are the ones who killed him?

Why does the madman say, “I come too early?”

The Madman. —Have you ever heard of the madman who on a bright morning lighted a lantern and ran to the marketplace calling out unceasingly: “I seek God! I seek God!”—As there were many people standing about who did not believe in God, he caused a great deal of amusement. Why! is he lost? said one. Has he strayed away like a child? said another. Or does he keep himself hidden? Is he afraid of us? Has he taken a sea voyage? Has he emigrated? —the people cried out laughingly, all in a hubbub. The insane man jumped into their midst and transfixed them with his glances. “Where is God gone?” he called out. “I mean to tell you! We have killed him, —you and I! We are all his murderers! But how have we done it? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the whole horizon? What did we do when we loosened this earth from its sun? Whither does it now move? Whither do we move? Away from all suns? Do we not dash on unceasingly? Backwards, sideways, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an above and below? Do we not stray, as through infinite nothingness? Does not empty space breathe upon us? Has it not become colder? Does not night come on continually, darker and darker? Shall we not have to light lanterns in the morning? Do we not hear the noise of the gravediggers who are burying God? Do we not smell the divine putrefaction? —for even Gods putrefy! God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we console ourselves, the most murderous of all murderers? The holiest and the mightiest that the world has hitherto possessed, has bled to death under our knife, —who will wipe the blood from us? With what water could we cleanse ourselves? What lustrums, what sacred games shall we have to devise? Is not the magnitude of this deed too great for us? Shall we not ourselves have to become Gods, merely to seem worthy of it? There never was a greater event, —and on account of it, all who are born after us belong to a higher history than any history hitherto!”—Here the madman was silent and looked again at his hearers; they also were silent and looked at him in surprise. At last, he threw his lantern on the ground, so that it broke in pieces and was extinguished. “I come too early,” he then said, “I am not yet at the right time. This 169prodigious event is still on its way, and is travelling, —it has not yet reached men’s ears. Lightning and thunder need time, the light of the stars needs time, deeds need time, even after they are done, to be seen and heard. This deed is as yet further from them than the furthest star, —and yet they have done it!”—It is further stated that the madman made his way into different churches on the same day, and there intoned his Requiem aeternam deo. When led out and called to account, he always gave the reply: “What are these churches now, if they are not the tombs and monuments of God?”— (Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Gutenberg)

The Will to Power

Nietzsche, aware of the new theory of Darwinian evolution, suggested that what drives the survival of the fittest was not a random “natural selection” but instead the supremacy of willpower. Again, from Beyond Good and Evil:

Psychologists should bethink themselves before putting down the instinct of self-preservation as the cardinal instinct of an organic being. A living thing seeks above all to discharge its strength—life itself is Will to Power; self-preservation is only one of the indirect and most frequent results thereof. (Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Project Gutenberg)

Strongly influenced by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s notion of “the will” as the motivating force of human existence, Nietzsche believed that it was the will to power that most motivates us.

However, the concept was never systematically defined in Nietzsche’s work, leaving its interpretation open to debate. On the one hand, it could be read as the will to dominate others. Nietzsche, however, seems to suggest that this will should be used to dominate the lesser passions of one’s self. To attain this self-control would set one apart from the majority of human beings. This idea becomes evident in his rhetoric about the distinction between masters and servants.

Wherever I found a living thing, there found I Will to Power; and even in the will of the servant found I the will to be master.

That to the stronger, the weaker shall serve—thereto persuadeth he his will who would be master over a still weaker one. That delight alone he is unwilling to forego.

And as the lesser surrendereth himself to the greater that he may have delight and power over the least of all, so doth even the greatest surrender himself, and staketh—life, for the sake of power. (Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra, Ch. 34, Gutenberg)

To become master of one’s own vital force, one’s will, is to become a superior human being, an ubermensch. This idea would be corrupted and twisted by the Nazi propagandists who came into power after Nietzsche’s death. According to one historian:

Friedrich Nietzsche and his younger sister, Elisabeth, were close as children but grew apart in adulthood when Elisabeth married Bernhard Förster, who had strong antisemitic beliefs. Friedrich did not attend their wedding. After her husband died by suicide, Elisabeth became a member of the Nazi party.

When Elisabeth took over the care of her brother towards the end of his life, she unfortunately also gained control of all his literary work. After her brother’s death in 1900, Elisabeth set to work editing some notes he had tentatively titled, “Will to Power.” She published the book in her brother’s name in 1901 with a great deal of her antisemitic and Nazi propaganda added to her brother’s original work. To this day, Nietzsche is still associated with the Nazi party in people’s minds despite the fact that he strongly disagreed with his sister’s antisemitic beliefs. “Will to Power” has been described as a “historic forgery.” (Giorgio Colli-Mazzino Montinari, Introduction to Friedrich Nietzsche “Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe” (KGA), hrsg. Colli und Montinari (edited by), Berlin und New York 1967.)

How to be an Epistemological Relativist

Taking it to the Streets…

Present the following hypothetical scenario to 10 different people. Take careful note of their responses and the approach they to arriving at what they will believe or do.

Compare and contrast the responses you get.

- How many of your respondents engaged in a Skeptical approach?

- How many utilized Rationalism or Empiricism?

- Were there any Constructivists among your respondents?

- Did any of your respondents take a “live and let live” Relativist approach?

- What patterns did you notice among your respondents?

- Were there any obvious biases?

- If there was one approach to evaluating this claim that stood out above the rest, why do you think that was the case?

The approach people take to evaluating a truth claim can tell us a great deal about their overall approach to knowledge and you may observe that approaches vary widely from person to person. What do you think accounts for this?

Relativism holds that we are making a mistake if we think that there is only one objective way to live or view the world. As a subjective theory, Relativism states that it is up to the individual or society to make a determination regarding what is true. Any truth claim is true only with respect to our particular perspective and how we interpret information from that unique perspective. There is no neutral or objective way to know. We can only make a determination based on how well a particular belief works for us. When faced with the claim that the Earth is flat, each relativist would make their own decision about whether to believe that to be the case or not based on their personal, subjective perspective.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Perspectivism

Nietzsche’s perspectivism is a philosophical viewpoint that suggests that all knowledge is perspectival and subjective, shaped by individual perspectives, experiences, and interpretations. Here are the strengths and weaknesses of Nietzsche’s perspectivism:

On the one hand:

- Perspectivism acknowledges the diversity of human experiences and perspectives. It celebrates the multiplicity of viewpoints and highlights the richness that different perspectives bring to understanding the world. Perspectivism recognizes that humans have always had differing opinions and perspectives. Throughout human history, people and cultures have held a diversity of views. Nietzsche’s theory validates these unique experiences and interpretations. It helps us be more open-minded and tolerant, and less dogmatic, rejecting the idea that any individual or group’s ideas are superior to another. Because there is no objective standard, perspectivism allows us the freedom to doubt and question, and think outside the box.

- It challenges the idea of absolute truths or objective knowledge. Nietzsche’s perspectivism questions the existence of universal, unchanging truths and emphasizes the dynamic and subjective nature of knowledge.

- Perspectivism encourages critical reflection on established beliefs and values. By acknowledging that knowledge is shaped by perspectives, it prompts individuals to critically examine their assumptions and question the validity of commonly accepted truths. Nietzsche’s Perspectivism paved the way for the emergence of psychology by recognizing that each of us colors our experience of the world based on our past emotional histories.

- Perspectivism also opened doors in the world of art and music. Nietzsche considered art to be the highest expression of a noble existence. Prior to Nietzsche, the assumption was that artists painted or sculpted the reality of what they were seeing in the world. But after Nietzsche, it became more and more the case that artists presented abstract works and left their meaning up to the perceiver who brought his or her unique perspective to the work.

On the other hand:

- Critics argue that Nietzsche’s perspectivism can slide into relativism, where all perspectives are considered equally valid. This can lead to a problematic stance where there’s no basis for distinguishing between well-supported perspectives and baseless opinions. The theory requires that we give equal weight and value to all opinions, even those that are harmful or damaging. It is difficult to rationalize the claim that Hitler was doing what he saw as good and necessary when the vast majority of the world found his actions abhorrent. Yet relativism means we must see Hitler’s views as being equally as valid as those who opposed him and his regime.

- While perspectivism rightly highlights the role of perspectives in shaping knowledge, it may downplay or dismiss the existence of an objective reality. This dismissal might lead to skepticism or a lack of belief in any shared truth or reality beyond subjective experiences. There are moral implications here: if there are no objective standards, then we can never say that something is wrong or mistaken. In order to say that something is untrue or mistaken, we need an objective measurement by which to make comparisons or draw conclusions, but this is not a tool available to the relativist. Relativists may have differing opinions, but there is no “right” or “wrong.”

- Nietzsche doesn’t offer a clear epistemic grounding for how one can differentiate between valid and invalid perspectives. The absence of criteria for evaluating perspectives might hinder the ability to discern valuable insights from mere personal biases.

- Perspectivism’s insistence on subjectivity might undermine the authority of expertise or established knowledge. If all perspectives are deemed equally valid, it might devalue expert opinions or well-founded scholarly conclusions.

- Moreover, perspectivism gives us no incentive to better ourselves or our society. If there is no higher standard or objective truth to seek, then we make the mistake of allowing our practices and beliefs to become stagnant. It may take us much longer to make progress if we think that our way of thinking or of doing things is the best.

Nietzsche’s perspectivism has been influential in challenging traditional notions of truth and knowledge, advocating for a more nuanced understanding of how knowledge is constructed. However, its potential to slide into relativism and the lack of clear criteria for evaluating perspectives remain points of contention among philosophers.

Works Cited

Alienized. “Ufo Extraterrestrial Science-Fiction Alien.” Pixabay, Pixabay, https://pixabay.com/illustrations/ufo-extraterrestrial-science-fiction-4995753/. Accessed 12 Apr. 2022.

Schultze, Gustav. “Friedrich Nietzsche.” Flickr, WikiCommons, 24 Apr. 2015, https://www.flickr.com/photos/royaloperahouse/17048487967. Accessed 12 Apr. 2022.