9.6 Art and the Emotional Life – Schopenhauer and Tolstoy

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section you will discover:

- How Arthur Schopenhauer understood the aesthetic experience to be one of the few ways in which we humans can escape the crushing suffering of our existence.

- How the novelist Leo Tolstoy saw the arts as human attempts to communicate with others via deeply moving emotions to evoke love and brotherhood, ultimately bringing us to spiritual unity.

What is art’s personal value? Can art be therapeutic? Hegel had understood art to be of value to the full freedom of his universal world Spirit and the well-being of society but had not much explored the individual’s subjective experience of artistic beauty. Certainly when we enjoy a great film or piece of music we are not often thinking about how it advances the self-consciousness of the universe but instead reveling in the temporary pleasure it provides. It’s this kind of temporary escape that Schopenhauer focuses on in his aesthetics.

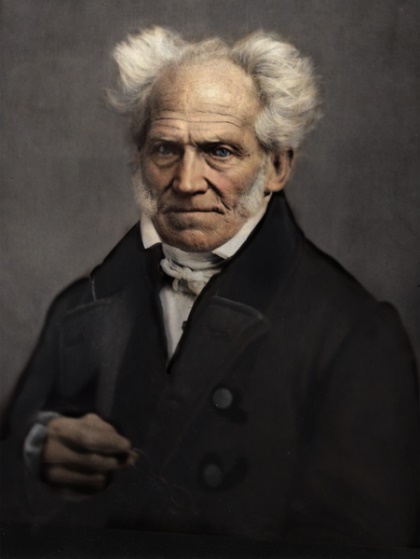

Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer was a contemporary and rival of Hegel.

He is famous for his pessimistic understanding of human existence. In his The World as Will and Representation (1818/1844) he argues that:

1. Life is suffering – Schopenhauer believed that existence at its core is constituted of pain, misery, anguish, frustration, and dissatisfaction. These pervade the human condition no matter one’s external circumstances. Even fleeting pleasures only satisfy desires that immediately regenerate, leaving us wanting.

2. The root cause of this suffering is the metaphysical Will – The ceaseless striving force that drives all of existence, including human desires, is the inherently irrational Will that subjects us to suffering by enslaving us to ultimately dissatisfying and endless willing. Life is thus guaranteed to be painful.

3. No lasting happiness is ever truly attainable – Because the very nature of the omnipresent Will makes suffering intrinsic to life at the most fundamental level, for Schopenhauer, there is no lasting salvation or happiness to be had. Any joys are temporary respites from the Will before suffering inevitably returns even stronger. The basic structure of existence entails profound, irrevocable dissatisfaction.

It was in this context that Schopenhauer viewed the arts, especially music, as one of the few joys of human existence. Schopenhauer’s aesthetics are found chiefly in Volume I of his The World as Will and Representation (1818/1844) –especially Book III where Schopenhauer presents his metaphysical theory of art—and in his Parerga and Paralipomena (1851) in the essays “On the Metaphysics of Music,” “On the Inner Nature of Art,” and “On Genius.” In these he argues that the arts provide momentary escape and respite from the suffering imposed by the endless striving Will that constitutes reality. By becoming engrossed in contemplating aesthetic ideas within great art, we are temporarily lifted out of life’s misery.

In his main work, Schopenhauer praised the Dutch Golden Age artists, who “directed such purely objective perception to the most insignificant objects and set up a lasting monument of their objectivity and spiritual peace in paintings of still life. The aesthetic beholder does not contemplate this without emotion.”(The World as Will and Representation, Vol 1).

Art can relieve our misery because it has the capacity to elicit the Platonic Ideas – – the eternal essences and timeless archetypes that lie behind the vain appearances of the world available to sense perception [See section 4.2.2 above]. Apprehending these Ideas leads to liberation from individuality and affirmation of the possibility of timeless truths. By revealing the perfect Platonic ideas art points to a profound beauty and perfection behind existence itself. Thus Schopenhauer saw art as almost a quasi-religious salvific force that allowed a glimpse of a deep meaning beyond the vexing strife of daily life. Art was humanity’s momentary redeemer and only genuine consolation.

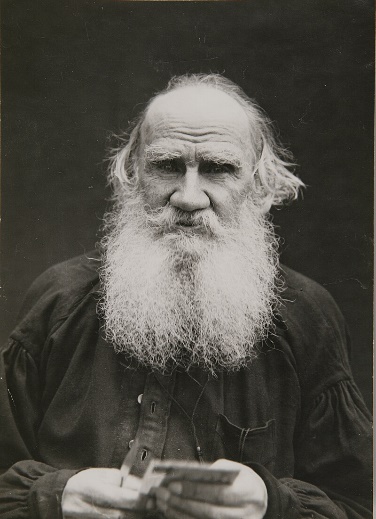

Tolstoy

A near contemporary of Schopenhauer, the great Russian novelist and philosopher Leo Tolstoy viewed art as the expression of universal brotherhood.

Tolstoy wrote in the age of Realism. In his work “What is Art?” (1897) he claimed that art is an activity by which one person transmits feelings intentionally to others so that they too experience those feelings. Its purpose is emotional “infection.” Good art infects us with “lofty religious perception and feeling.” It is this universal accessibility and infectious emotional power that defines real art. We see here something of a return to the concerns of Plato and Aristotle that art serve a positive purpose for society. Good art can convey feelings across social/cultural barriers. If a work fails to infect others emotionally it cannot truly be called art. In the creation of such infectious art sincerity is essential. An artist must genuinely feel the emotions fueling their creations. Those creating just for fame, rewards, merchandizing or with ulterior motives are not authentic artists according to Tolstoy.

The supreme aim of art should be the generation of religious/moral emotions that evoke love and solidarity, promoting life’s spiritual unity. The highest arts ought to awaken love of one’s neighbor and God. Lesser, more gratuitous, or materialistic expressions elicit only base emotions and should not truly be called art. In this sense Tolstoy’s philosophy of art was deeply bound to morality, religion, and spirituality. Art was valuable only in its ability to infect audiences with emotions reflecting religious ideals that could promote moral principles and social bonds advocating for universal solidarity, empathy, and love. This was true art’s ethical purpose for Tolstoy.

Works Cited

Johann Schäfer, Arthur Schopenhauer, (1859), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur_Schopenhauer_colorized.png, CC0 1.0 Public Domain. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid (1658–1661), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_Golden_Age_painting. Public Domain. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

(Leo Tolstoy, 1828-1910), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_Tolstoy, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LNTolstoy.jpg. Public Domain. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Alexei Savrasov, The Rooks Have Returned, (1871), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Realism_%28arts%29. Public Domain. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.