Chapter 1: Introduction to Forensic Anthropology

WHAT IS ANTHROPOLOGY?

Why are people so diverse? Some people live in the frigid Arctic tundra, others in the arid deserts of sub-Saharan Africa, and still others in the dense forests of Papua New Guinea. Human beings speak more than 6,000 distinct languages. Some people are barely five feet tall while others stoop to fit through a standard door frame. In some places, people generally have very dark skin, in other places, people are generally pale. In some societies, eating pig is strictly prohibited; in others, pork is a rather ordinary food. What makes people differ from one another? What do we all share in common? How are humans different from other primates? How have primates adapted to different places? How and why did humans develop in the first place? These are some of the questions anthropologists try to answer.1

Derived from Greek, the word “anthropos” means “human” and “logy” refers to the “study of.” Therefore anthropology, by definition, is the study of humans. Anthropologists are not the only scholars to focus on the human condition; biologists, sociologists, psychologists, and others also examine human nature and societies. However, anthropologists uniquely draw on four key approaches to do their research: holism, comparison, dynamism, and fieldwork. Anthropology is an incredibly broad and dynamic discipline. It studies humanity by exploring our past and our present and all of our biological and cultural complexity.1

Holism

Anthropologists are interested in the whole of humanity, in how various aspects of biological or cultural life intersect. One cannot fully understand what it means to be human by studying a single aspect of our complex bodies or societies. By using a holistic approach, anthropologists ask how different aspects interact with and influence one another. For example, a biological anthropologist studying monkeys in South America might consider the species’ physical adaptations, foraging patterns, ecological conditions, and interactions with humans in order to answer questions about their social behaviors. By understanding how nonhuman primates behave, we discover more about ourselves: after all, as you will learn in this book, humans are primates! A cultural anthropologist studying marriage in a small village in India might consider local gender norms, existing family networks, laws regarding marriage, religious rules, and economic requisites in order to understand the particular meanings of marriage in that context. By using a holistic approach, anthropologists appreciate the complexity of any biological, social, or cultural phenomenon.1

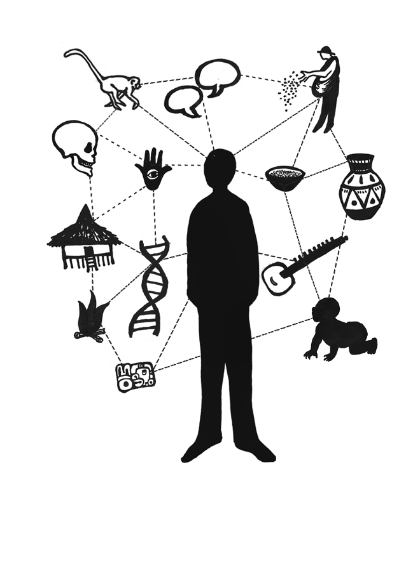

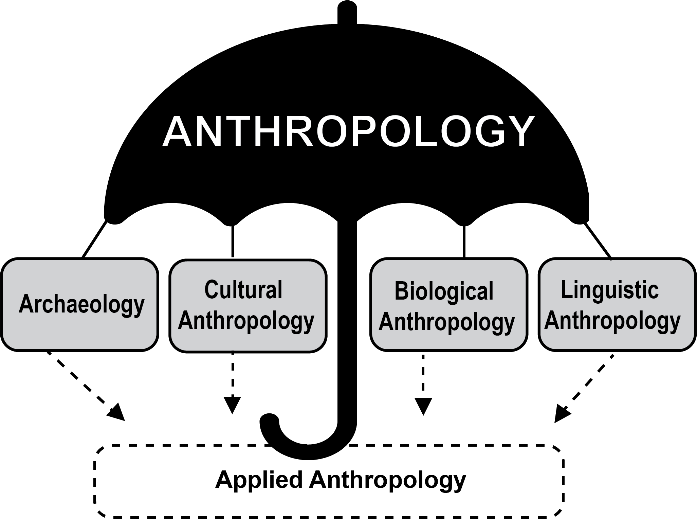

As we will discuss in more detail, anthropology itself is a holistic discipline, comprised (in the United States) of four major areas of study called subdisciplines: cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and archaeology. We need all four subdisciplines in order to understand the human experience, which involves culture, language, and biological and social adaptations, as well as our history, evolution, and relationship to our closest living relatives: nonhuman primates.1

Comparison

Anthropology is a comparative discipline: anthropologists compare and contrast data in order to understand what all humans have in common, how we differ, and how we have changed over time. The comparative approach can be historical: How do humans today differ from ancient Homo sapiens? How has Egyptian society changed since the building of the great pyramids? How is the English language adapting to new modes of communication like smartphones? The comparative approach is also applied to sociocultural phenomena. We can compare the roles of men and women in different societies or different religious traditions within a given society. Some anthropologists compare different primate species, investigating traits shared by all primates (including humans!) or identifying traits that distinguish one primate group from another. Unlike some other disciplines that also use comparative approaches, anthropologists do not just consider our own species or society. Our comparisons span societies, cultures, time, place, and species.1

Dynamism

Humans are one of the most dynamic species. Our ability to change, both biologically and culturally, has enabled us to persist over the course of millions of years, and to thrive in many different environments.1

Depending on their research focus, anthropologists ask about all kinds of changes: short-term or long-term, temporary or permanent, cultural or biological. For example, a cultural anthropologist might look at how people in a relatively isolated society change in the context of globalization, the process of interaction and interdependence among different nations and cultures of the world. A linguistic anthropologist might ask how a new form of language, like Spanglish, emerges. An archaeologist might ask how climate change influenced the emergence of agriculture. A biological anthropologist might consider how diseases affecting our ancestors led to changes in their bodies. All these examples highlight the dynamic nature of human bodies and societies. While we differ from our ancestors who lived hundreds of thousands of years ago, we share with them this capacity for change.1

Fieldwork

Throughout this book, you will read examples of anthropological research that will take you around the world. Anthropologists do not only work in laboratories, libraries, or offices. To collect data, they go to where their data lives, whether it is a city, village, cave, tropical forest, or desert. At their field sites, anthropologists collect data which, depending on subdiscipline, may be interviews with local peoples, examples of language in use, skeletal remains, or human cultural remains like potsherds or stone tools. While anthropologists ask an array of questions and use diverse methods to answer their research questions, they share this commitment to conducting their research out of their offices and in the field.1

A Brief History of Anthropology

Imagine only interacting with people who looked, spoke, and acted like you. Now, how would you begin to understand a seemingly new group of people? As people first began to explore the world, they grappled with how to make sense of human differences. Many were adventurers, missionaries, or traders, motivated by a desire to explore, spread their religion, or acquire wealth. All of them were familiar with only one way of life—their own. It was, therefore, through the lens of their own culture that they viewed people they met during their travels.1

One of the first examples of someone who attempted to systematically study and document cultural differences among different peoples is Zhang Qian (Chang Ch’ien 164 BC – 113 BC). Born in the second century BCE in Hanzhong, China, Zhang was a military officer who was assigned by Emperor Wu of Han to travel through Central Asia, going as far as what is today Uzbekistan. He spent more than 25 years traveling and recording his observations of the peoples and cultures of Central Asia. The Emperor used this information to establish new relationships and cultural connections with China’s neighbors to the West. Zhang discovered many of the trade routes used in the Silk Road and introduced many new cultural ideas, including Buddhism, into Chinese culture. 1

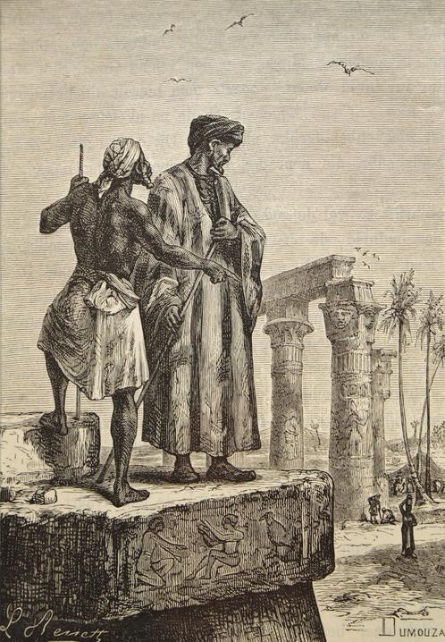

Another early traveler of note was Abu Abdullah Muhammad Ibn Battuta (known most widely as Ibn Battuta) (1304-1369). Ibn Battuta was an Amazigh (Berber) Moroccan Muslim scholar. Over a period of nearly 30 years during the fourteenth century, Ibn Battuta’s travels covered nearly the whole of the Islamic world, including parts of Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, India, and China. Upon his return to the Kingdom of Morocco, he documented the customs and traditions of the people he encountered in a book called Tuhfat al-anzar fi gharaaib al-amsar wa ajaaib al-asfar (A Gift to those who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling), but became commonly known as Al Rihla, which means “travels” in Arabic (McIntosh-Smith 2003: ix). This book became part of a genre of Arabic literature that included descriptions of the people and places visited along with commentary about the cultures encountered. Some scholars consider Rihla to be among the first examples of early pre-anthropological writing. 1

Later, from the 1400s through 1700s, during the so-called “Age of Discovery,” Europeans began to not only explore the world but also colonize it. Europeans exploited natural resources and human labor, exerting social and political control over people they encountered. New trade routes, along with the slave trade, fueled a growing European empire, while forever disrupting previously independent cultures in the Old World. European ethnocentrism—the belief that one’s own culture is better than others—was used to justify the subjugation of non-European societies.1

As European empires expanded, new ways of understanding the world and its people arose. Beginning in the eighteenth century in Europe, the Age of Enlightenment was a social and philosophical movement that privileged science, rationality, and empiricism while critiquing religious authority. This crucial period of intellectual development planted the seeds for many academic disciplines, including anthropology. It gave ordinary people the capacity to learn through observation and experience: Anyone could ask questions and use rational thought to discover things about the natural and social world.1

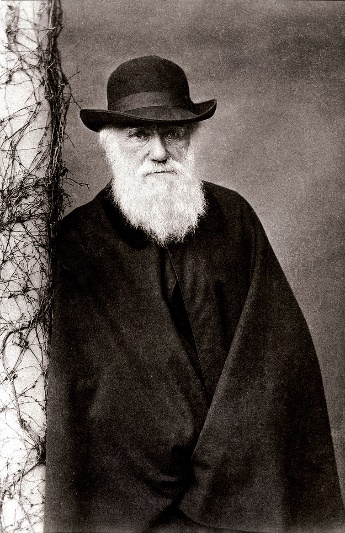

For example, Charles Lyell (1797–1875), a geologist, would observe layers of rock and argue that Earth’s surface must have changed gradually over long periods of time, such that it could not be only 6,000 years old (as the Young Earth interpretation in the Bible contends). Charles Darwin (1809–1882), a naturalist and biologist, would observe similarities between fossils and living specimens, leading him to argue that all life is descended from a common ancestor. Philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) would contemplate the origins of society itself. He wrote that people lived in relative isolation until they agreed to form a society in which the government would protect their personal property.1

These radical ideas about the earth, evolution, and society influenced early social scientists into the nineteenth century. For example, Herbert Spencer (1820–1903), inspired by scientific principles, used biological evolution as a model to understand social evolution: just as biological life evolved from simple to complex multicellular organisms, he postulated that societies “evolve” to become larger and more complex. Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881) argued that all societies “progress” through the same stages of development: savagery—barbarism—civilization. Societies were classified into these stages based on their kinship patterns, technologies, subsistence patterns, and so forth. So-called savage societies, ones that used rudimentary tools and foraged for food, were said to be stalled in their mental and moral development.1

Ethnocentric ideas, like those of Morgan, were challenged by anthropologists in the early twentieth century in both Europe and the United States. During World War I, Bronislaw Malinowski (1884–1942), a Polish anthropologist, became stranded on the Trobriand Islands, where he started to do participant-observation fieldwork: the method of immersive, long-term fieldwork that cultural anthropologists use today. By living with and observing the Trobrianders, he realized that their culture was not “savage,” but rather fulfilled the needs of the people. He developed a theory to explain human cultural diversity: Each culture functions to satisfy the specific biological and psychological needs of its people. While this theory has been critiqued for overemphasizing individuals apart from culture, it was an early attempt to view other cultures in more relativistic ways.1

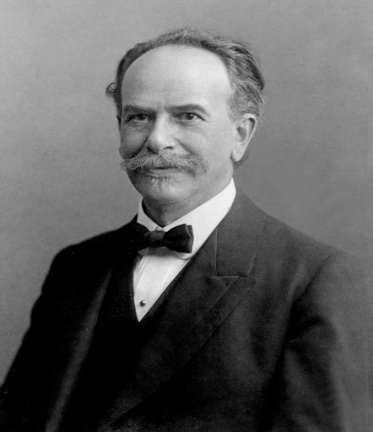

Around the same time in the United States, Franz Boas (1858–1942), widely regarded as the founder of American anthropology, developed the cultural relativistic approach: the view that cultures differ but are not better or worse than one another. In his critique of ethnocentric views, Boas insisted that physical and behavioral differences among so-called racial groups in the United States were shaped by environmental and social conditions, not biology. In fact, he argued, culture and biology are distinct realms of experience: Human behaviors are socially learned, contextual, and flexible, not innate. Further, Boas worked to transform anthropology into a professional and empirical academic discipline that integrated the four subdisciplines: cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology, archaeology, and biological anthropology.1

THE SUBDISCIPLINES

Because human experiences are varied and complex, we need a diversified tool kit to study them. Anthropology therefore comprises four subdisciplines: Some are more scientific (like biological anthropology), while others are more humanistic (like cultural anthropology). The scientific subdisciplines tend to use the scientific method to develop theories that explain human origins, evolution, material remains, or behaviors. The humanistic subdisciplines tend to use observational methods and interpretive approaches to understand human beliefs, languages, behaviors, cultures, and social organization. Findings from all four subdisciplines contribute to a multifaceted appreciation of human bio-cultural experiences, past and present.1

Cultural Anthropology

Cultural anthropologists focus on similarities and differences among living societies. They suspend their own sense of what is “normal” in order to understand the perspectives of the people they study (cultural relativism). They learn these perspectives through participant-observation fieldwork: a method that involves living with, observing, and learning from the people one studies. Beyond describing another way of life, cultural anthropologists ask broader questions about humankind: Are human emotions universal or culturally specific? Does globalization make us all the same or do we maintain cultural differences? For cultural anthropologists, no aspect of human life is outside their purview: They study art, religion, healing, natural disasters, video gaming, even pet cemeteries. While many cultural anthropologists are intrigued by human diversity, they realize that people around the world share much in common.1

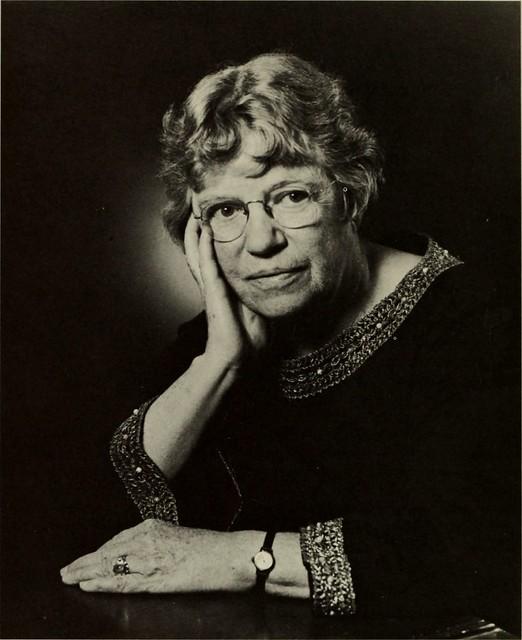

One famous American cultural anthropologist, Margaret Mead (1901–1978), conducted several cross-cultural studies of gender and socialization practices. In the early twentieth century in the United States, people wondered if the emotional turbulence of American adolescence was caused by the biology of puberty (and thus natural and universal) or something else. To find out, Mead set off for the Samoan Islands, where she lived for several months getting to know Samoan teenagers. She learned that Samoan adolescence was not angst-ridden (like it was in the United States), but rather a relatively tranquil and happy life stage. Upon returning to the United States, Mead wrote Coming of Age in Samoa, a best-selling book that was both sensational and scandalous (Mead 1928). In it, she critiqued U.S. parenting as overly restrictive, and contrasted it to Samoan parenting, which allowed teenagers to freely explore their community and even their sexuality. Ultimately, she argued that nurture (i.e., socialization) more than nature played a key role in the experience of child development.1

Cultural anthropologists do not always travel far to provide insight into human experience. In the 1980s, American anthropologist Philippe Bourgois (1956–) wanted to understand how pockets of extreme poverty persist amid the wealth and overall high quality of life in the United States. To answer this question, he lived with Puerto Rican crack dealers in East Harlem, contextualizing their experiences both historically (in terms of socioeconomic dynamics in Puerto Rico and in the United States) and presently (in terms of social marginalization and institutional racism). Rather than blame crack dealers for their poor choices or blame our society for perpetuating inequality, he argued that both individual choices and social inequality can trap people in the overlapping worlds of drugs and poverty.1

Linguistic Anthropology

Language is a defining trait of human beings. While other animals have communication systems, only humans have complex, symbolic languages—more than 6,000 of them! Human language makes it possible to teach and learn, to plan and think abstractly, to coordinate our efforts, and to contemplate even our own demise. Linguistic anthropologists ask questions like: How did language first emerge? How has it evolved and diversified over time? How has language helped us succeed as a species? How does language indicate social identity? How does language influence our views of the world? If you speak two or more languages, you may experience how language affects you. For example, in English, we say: “I love you.” But Spanish speakers use different terms— “te amo,” “te adoro,” “te quiero,” and so on—to convey different kinds of love: romantic love, platonic love, maternal love, etc. The Spanish language arguably expresses more nuanced versions of love than the English language.1

One intriguing line of linguistic anthropological research focuses on the relationships between language, thought, and culture. It may seem intuitive that our thoughts come first; after all, we like to say, “Think before you speak.” However, according to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (also known as linguistic relativity), the language you speak allows you to think about some things and not other things. When Benjamin Whorf (1897–1941) studied the Hopi language, he not only found word-level differences, but also grammatical differences between Hopi and English tenses. He wrote that Hopi has no grammatical tenses to convey the passage of time. Rather, Hopi language only indicates whether or not something has “manifested.” Whorf argued that English grammatical tenses (past, present, future) inspire a linear sense of time, while Hopi language inspires a cyclical experience of time (Whorf 1956). Some critics, like German American linguist Ekkehart Malotki (1938–), refute Whorf’s theory, arguing that Hopi do have linguistic terms for time and that a linear sense of time is natural and perhaps universal. At the same time, Malotki recognized that English and Hopi tenses differ, albeit in ways less pronounced than Whorf proposed.1

Other linguistic anthropologists track the emergence and diversification of languages, while others focus on language use in today’s social contexts. Still others explore how language is crucial to socialization: children learn their culture and social identities through language and nonverbal forms of communication.1

Archaeology

Archaeologists focus on the material past: the tools, food, pottery, art, shelters, seeds, and other objects left behind by people. Prehistoric archaeologists recover and analyze these materials to reconstruct the lifeways of past societies that lacked writing. They ask specific questions like: How did people in a particular area live? What did they eat? What happened to them? They ask general questions about humankind: When and why did humans first develop agriculture? How did cities first develop? What type of interactions did prehistoric people have with their neighbors?1

One key method that archaeologists use to answer their questions is excavation—a method of careful digging and removing of dirt and stones to uncover material remains while recording their context. Archaeological research spans millions of years from human origins to the present. For example, Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978), a British archaeologist, was one of few women working in this field in the 1940s. While excavating at Jericho (which dates back to 10,000 BCE), she discovered city structures and cemeteries built during the Early Bronze Age (3,200 y BP in Europe). Based on her findings, she argued that Jericho is the oldest city continuously occupied by different groups of people.1

Historical archaeologists’ study recent societies using material remains to complement the written record. For example, the Garbage Project, which began in the 1970s, is an archaeological project based in Tucson, Arizona. It involves excavating a contemporary landfill as if it were a conventional dig site. Archaeologists found a difference between what people say they throw out and what is actually in their trash. In fact, many landfills hold large amounts of paper products and construction debris. This finding has practical implications for creating more environmentally sustainable waste-disposal practices.1

Biological Anthropology

Biological anthropology, which will be thoroughly introduced later in this chapter, is the study of human origins, evolution, and variation. Some biological anthropologists focus on our closest living relatives: monkeys and apes. They examine the biological and behavioral similarities and differences between nonhuman primates and human primates (us!). Other biological anthropologists focus on extinct human species, asking questions like: What did our ancestors look like? What did they eat? When did they start to speak? And, how did they adapt to new environments?1

Many biological anthropologists explore how human genetic and phenotypic (observable) traits vary in response to environmental conditions. For instance, Nina Jablonski (1953–) asks why darker skin pigmentation is more prevalent in high ultraviolet (UV) contexts (like Central Africa), while lighter skin pigmentation is more prevalent in low UV contexts (like Nordic countries). She explains this pattern in terms of the interplay among skin pigmentation, UV radiation, folic acid, and vitamin D. In brief, UV radiation breaks down folic acid, which is essential to DNA and cell production. Dark skin helps to block UV, thereby protecting the body’s folic acid reserves in high-UV contexts. Light skin evolved when humans migrated out of Africa to low-UV contexts, where dark skin blocks too much UV radiation, compromising the body’s ability to absorb vitamin D from the sun (vitamin D is essential to calcium absorption and a healthy skeleton). Jablonski shows that the spectrum of skin pigmentation that we see today evolved to balance UV exposure with the bodily need for vitamin D and folic acid.1

While some biological anthropologists study hominins (modern-day humans and human ancestors), others focus on nonhuman primates. For example, Jane Goodall (1934–) has devoted her life to studying wild chimpanzees (Goodall 1996). Beginning in the 1960s when she began her research in Tanzania, Goodall challenged widely held assumptions about the inherent differences between humans and apes. At the time, it was assumed that monkeys and apes lacked the social and emotional traits that made human beings such exceptional creatures. However, Goodall discovered that, like humans, chimpanzees also make tools, socialize their young, have intense emotional lives, and form strong maternal-infant bonds. Her work highlights the value of field-based research in natural settings as it can reveal the complex lives of nonhuman primates. Throughout this book, we will learn about many examples of biological anthropological research that explores our earliest ancestors, our evolution, and our nonhuman primate cousins.1

Applied Anthropology

Sometimes considered a fifth subdiscipline, applied anthropology involves the practical application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve real-world problems. Applied anthropologists are employed outside of academic settings, in both the public and private sectors, including business or consulting firms, advertising companies, city government, law enforcement, the medical field, nongovernmental organizations, and even the military.1

Applied anthropologists span the subdisciplines. An applied archaeologist might work in cultural resource management to assess a potentially significant archaeological site unearthed during a construction project. An applied cultural anthropologist could work for a technology company that seeks to understand the human-technology interface in order to design better tools.1

Medical anthropology is an example of both an applied and theoretical area of study that draws on all four subdisciplines to understand the interrelationship of health, illness, and culture. Rather than assume that disease resides only within the individual body, medical anthropologists explore the environmental, social, and cultural conditions that impact the experience of illness. For example, in some cultures, people believe that illness is caused by an imbalance within the community. Therefore, a communal response, such as a group healing ceremony, is necessary to restore the health of the person and the group. In other cultures, like mainstream U.S. society, people typically go to a doctor to find the biological cause of an illness and then take medicine to restore the individual body.1

Trained as both a physician and medical anthropologist, Paul Farmer (1959–) demonstrates the potential of applied anthropology. During his college years in North Carolina, Farmer’s interest in the Haitian migrants working on nearby farms inspired him to visit Haiti. There, he was struck by the poor living conditions and lack of healthcare facilities. Eventually, as a physician, he would return to Haiti to treat diseases, like tuberculosis and cholera, that were rarely seen in the United States. As an anthropologist, he would contextualize the suffering of his Haitian patients in relation to the historical, social, and political forces that impact Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere (Farmer 2006). Today, he not only writes academic books about human suffering, he also takes action. Through the work of Partners in Health, a nonprofit organization that he cofounded, he has opened health clinics in many resource-poor countries and trained local staff to administer care. In this way, he applies his medical and anthropological training to improve people’s lives.1

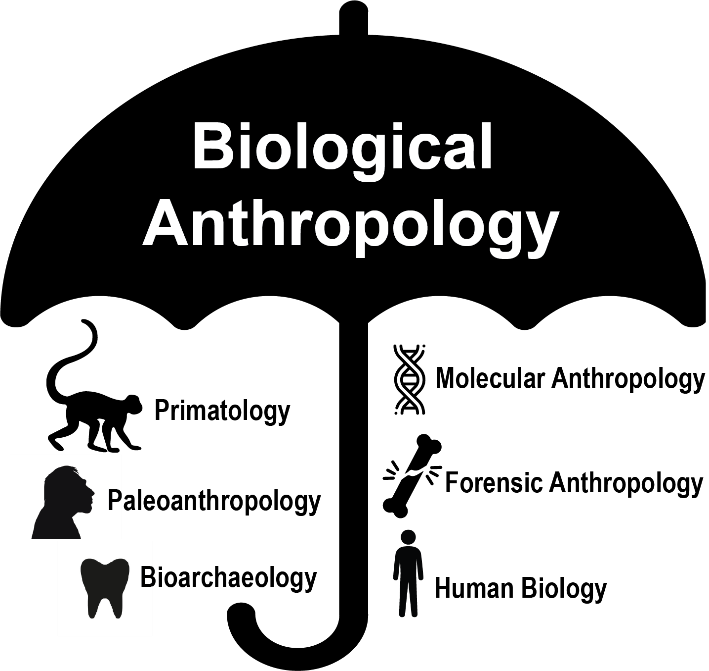

WHAT IS BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY?

The focus of this book is the anthropological subdiscipline of biological anthropology, which is the study of the human species from a biological perspective. Biological anthropology uses a scientific and evolutionary approach to answer many of the same questions all anthropologists are concerned with: What does it mean to be human? Where do we come from? Who are we today? Biological anthropologists are concerned with exploring how humans vary biologically, how humans adapt to their changing environments, and how humans have evolved over time and continue to evolve today. Some biological anthropologists also study nonhuman primates to learn about what we have in common and how we differ.1

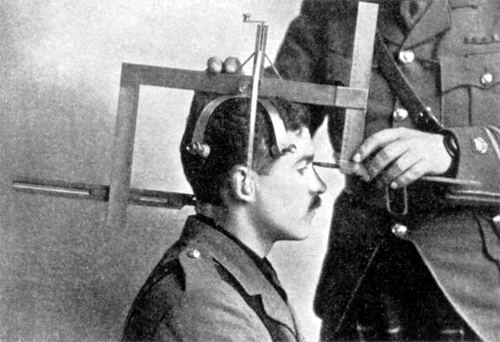

You may have heard biological anthropology referred to by another name—physical anthropology. Physical anthropology is an area of research that dates to as far back as the eighteenth century, when it focused mostly on physical variation among humans. Some early physical anthropologists were also physicians interested in comparing and contrasting human skeletons. These researchers dedicated themselves to measuring bodies and skulls (anthropometry and craniometry) in great detail. Many also acted under the misguided and oftentimes racist belief that human biological races existed and it was possible to differentiate between, or even rank, such races by measuring differences in human anatomy. Most anthropologists today agree that there are no biological human races and that all humans alive today are members of the same species and subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens. We recognize that the differences we can see between peoples’ bodies are due to a wide variety of factors, including our environment, our diet, the activities we engage in, and our genetic makeup.1

The subdiscipline has changed a great deal since these early years. Biological anthropologists no longer set out to identify human differences in order to assign people to groups, like races. The focus is instead understanding how and why human and primate variation developed through evolutionary processes. The name for the subdiscipline has transitioned in recent years to reflect these changes. Many believe the term biological anthropology better reflects the subdiscipline’s focus today, which includes genetic and molecular research. Nevertheless, the term physical anthropology is still common.1

The Scope of Biological Anthropology

Just as anthropology as a discipline is wide-ranging and holistic, so too is the subdiscipline of biological anthropology. There are at least six subfields within biological anthropology. Each subfield focuses on a different dimension of what it means to be human from a biological perspective. Through their varied research in these subfields, biological anthropologists try to answer the following key questions:

What is our place in nature? How are we related to other organisms? What makes us unique?

What are our origins? What influenced our evolution?

How and when did we move/migrate across the globe?

How are humans around the world today different from and similar to each other? What influences these patterns of variation? What are the patterns of our recent evolution and how do we continue to evolve?1

The terms subfield and subdiscipline are very similar and can be confusing because they are often used interchangeably. In this book we use subdiscipline to refer to the four major areas of focus that make up the discipline of anthropology: biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, archaeological anthropology, and linguistic anthropology. When we use the term subfield we are referring to the different specializations within biological anthropology. These subfields include primatology, paleoanthropology, molecular anthropology, bioarcheology, forensic anthropology, and human biology.1

Primatology

Primatologists study the anatomy, behavior, ecology and genetics of living and extinct nonhuman primates, including apes, monkeys, tarsiers, lemurs, and lorises, because nonhuman primates are our closest living biological relatives. The research done by primatologists gives us insights into how evolution has shaped our species and primates in general. Through such studies we have learned that all primates share a suite of traits. Primates, for instance, have nails instead of claws, have hands that can grasp and manipulate objects, invest great amounts of time and energy in raising just a few offspring, and have complex social behaviors.1

Similar to Jane Goodall’s studies of wild chimpanzees, Dian Fossey’s research among mountain gorillas provided scientists with some illuminating insights into our primate cousins. She learned, for instance, that gorillas are like humans in that they have families and form strong maternal-infant relationships. Gorillas mourn the death of their group members, and also exhibit behaviors similar to humans such as playing and tickling. Importantly, the work of Dian Fossey, Jane Goodall, Karen B. Strier (see Appendix B), and others focus on primate conservation: They have brought attention to the fact that 60% of primates are currently threatened with extinction.1

Paleoanthropology

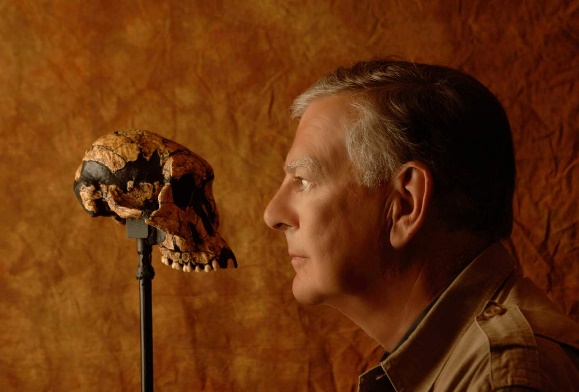

Paleoanthropologists study human ancestors from the distant past to learn how, why, and where they evolved. Because these ancestors lived before there were written records, paleoanthropologists have to rely on various types of physical evidence to come to their conclusions. This evidence includes fossilized remains (particularly fossilized bones), artifacts such as stone tools, and the contexts in which these items are found. Paleoanthropologists have made some monumental discoveries that have shaped the way we understand hominin evolution (hominin refers to humans and fossil relatives that are more similar to us than chimpanzees).1

One such discovery was made in Ethiopia in 1974 by paleoanthropologist Donald C. Johanson. He found the remains of a 3.2-million-year-old fossilized skeleton he named Lucy (she was named after the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” which the archaeologists played repeatedly at the celebration the evening after her discovery). Lucy was a remarkable find because she represented a new hominin species, Australopithecus afarensis, and the skeleton was over 40% complete. Like humans, she was bipedal (walked on two legs) and likely used tools. However, she had a much smaller brain than humans, larger teeth, and likely spent time in trees and on the ground. She was, in many ways, a transitional species between humans and earlier primates.1

Since the discovery of Lucy, several hundred more Australopithecus fossils have been found in Africa, as you will learn more about in chapter nine. From these finds, we know that many Australopithecus species flourished for millions of years. Some of these species likely led to our genus (Homo), while others appear to have died off. These findings helped us learn that human evolution did not occur in a simple, straight line, but branched out in many directions. Most branches were evolutionary “dead ends.” Humans are now the only hominins left living on planet Earth. Paleoanthropologists frequently work together with other scientists such as archaeologists, geologists, and paleontologists to interpret and understand the evidence they find. Paleoanthropology is a dynamic subfield of biological anthropology that contributes significantly to our understanding of human origins and evolution.1

Molecular Anthropology

Molecular anthropologists use molecular techniques (primarily genetics) to compare ancient and modern populations and to study living populations of humans and nonhuman primates. By examining DNA sequences in different populations, molecular anthropologists can estimate how closely related two populations are, as well as identify population events, like a population decline, that explain the observed genetic patterns. This information helps scientists trace patterns of migration or identify how people have adapted to different environments over time.1

Some exciting work that molecular anthropologists are doing today is studying the genetic material they find in ancient specimens. From this work we have learned, for instance, that many people in the world today have inherited some DNA from Neanderthals and/or a newly discovered species known as Denisovans. This tells us that at some point in our ancient past our modern human ancestors mated with Neanderthals and Denisovans and their genes were passed down to us. Moreover, it is now believed some of these genes helped our human ancestors survive.1

From the work of molecular anthropologists we have also learned which genes distinguish us genetically from our closest living relatives: chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas. In the case of chimpanzees, our genomes are somewhere between 96% and 99% identical. Yet that 2-4% contributes to a lot of physical (morphological) and behavioral differences! Molecular anthropology is a field changing quickly as new techniques and discoveries shape our understanding of ourselves and our nonhuman primate cousins.1

Human Biology

Many biological anthropologists do work that falls under the label human biology. This type of research is varied, but tends to explore how the human body is impacted by different physical environments, cultural influences, and nutrition. These include studies of human variation or the physiological differences among humans around the world. For instance, some humans have the ability to digest lactase in milk into adulthood, and others lack this ability. Some humans have an enhanced ability to resist malarial infections. Some humans tend to be very tall and lean while others are short and stocky. Still others tend to have dark skin and others lighter brown and even pale skin colors.1

Some of these anthropologists study human adaptations to extreme environments, which includes individual physiological responses and genetic advantages populations develop to help them live there. For example, people born at very high elevations adapt to life in an environment with decreased oxygen. Research has shown that populations that have lived for many generations at very high elevations, such as those in parts of Tibet, Peru, and Ethiopia, have developed long-term physiological adaptations. These include large lungs and chests and enhanced oxygen respiration and blood circulation systems that help them survive in an environment that otherwise might cause life-threatening hypoxia (oxygen deprivation) (Bigham 2016). Some anthropologists believe Tibetans’ adaptation to living in high altitudes, estimated to have occurred in less than 3,000 years, is one of the fastest cases of human evolution in the scientific record!1

In addition to studying how humans adapt to their physical environments and vary biologically, some biological anthropologists are interested in how nutrition and disease affect human growth and development. The modern Western diet that is high in processed starches, refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, sugar, and salt is increasingly causing a number of metabolic conditions. As cultural groups around the world begin to replace their traditional diets with these processed food products, they begin to experience a rise in diseases that plague Western societies, such as diabetes, heart disease, and hormonal imbalances. Other biological anthropologists have asked why girls in Western societies have begun to menstruate earlier (sometimes as young as seven years of age). A definitive explanation is still unresolved. Some speculate this may have to do with changes in our diet, while others believe it may also have to do with exposure to chemicals in the environment or other factors. Biological anthropologists engage in a wide range of research that span the breadth of human biological diversity.1

Bioarcheology

Bioarcheologists study human skeletal remains and the soils and other materials found in and around the remains. They use the research methods of skeletal biology, mortuary studies, osteology, and archaeology to answer questions about the lives and lifeways of past populations. Through studying the bones and burials of past peoples, bioarcheologists search for answers to how people lived and died. For example, bioarcheologists can estimate the sex, height, and age at which someone died. They can also gather clues about their lifestyle based on the skeleton, since bones respond to muscle use and developed muscle attachments may indicate extensive muscle use. Most bioarcheologists study not just individuals, but populations, to reveal biological and cultural patterns.1

Bioarcheologists are also interested in learning about ancient people’s health and nutrition, the diseases they suffered from and injuries they suffered. They may also look for clues to what people ate by examining the wear and condition of teeth or, in the case of well-preserved specimens, the residue from their last meals. Chemical studies of bones and teeth can also provide information about people’s diets as well as where people lived and moved during their lives. Bioarcheologists can reconstruct human migration and track the growth or decline of populations by looking for patterns of malnutrition, disease, and activities.1

Not all places are ideal for finding well-preserved human remains. Environments that are very cold, very dry, or devoid of oxygen can preserve corpses for many years, sometimes centuries. In 1991, a group of hikers found the body of a man frozen in the Italian Alps. Because of how well-preserved the body was, the discoverers initially thought he might be a hiker who had died several years prior. However, once bioarcheologists had a chance to study the body, they discovered the man had died around 5,300 years ago! Nicknamed Őtzi, or the Iceman, bioarcheologists determined he was wearing leggings, a coat, and shoes made of leather and fur when he died. They also discovered he had an arrow embedded in his left shoulder, suffered from osteoporosis, had multiple tattoo patterns throughout his body and was infected by the bacterium H. pylori, a common human stomach pathogen that likely gave him significant stomach pain. Researchers later found similarities between the strain of H. plyori bacterium that plagued Őtzi and the strains seen today in parts of Central and Southern Asia. Modern-day Europeans have strains of the bacterium that reflect mixtures of both African and Asian strains. This research helped scientists demonstrate that for thousands of years after Őtzi died human groups were migrating all over the world, even returning to Africa and then moving back north again. Research within the subfield of bioarcheology is continually providing important insights into humanity’s past.1

Forensic Anthropology

Forensic anthropologists use many of the same techniques as bioarcheologists to develop a biological profile for unidentified individuals including estimating sex, age at death, height, ancestry, diseases they had, or other unique identifying features. They may also go to a crime or accident scene to assist in the search and recovery of human remains, and/or identify trauma, like fractures, on bones. The popular television program Bones told the fictional story of a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Temperance Brennan, who brilliantly interpreted clues from victims’ bones and helped solve crimes. While the show includes forensic anthropology techniques and responsibilities, it also includes many inaccuracies. For example, forensic anthropologists generally do not collect trace evidence like hair or fibers, run DNA tests, carry weapons, or solve criminal cases. These researchers play an important role in aiding law enforcement to identify human remains.1

Some forensic anthropologists have been called on to interpret the remains of victims of mass murders, such as the case of the town of El Mozote in El Salvador. In December of 1981, during the country’s intense civil war, over 1,000 people were brutally killed by the Salvadoran right-wing military in and around a church in the town of El Mozote. Researchers later discovered that the U.S. government, under President Reagan, funded and trained the Special Forces of the Salvadoran Army who perpetrated the massacre. Starting in the mid-1990s, human rights organizations began to investigate the incident as a war crime, and finally, in 2015, a team of forensic anthropologists were called upon to study the bones of the deceased and try to reconstruct what happened at El Mozote and how the victims died. Their work provided important clues that helped bring some closure to the families and survivors of this horrible incident. It also provided answers to investigators looking to bring accountability to those responsible.1

Forensic anthropology is considered an “applied” area of biological anthropology, since it is a practical application of anthropological theories, methods, and findings to solve real-world problems. While many forensic anthropologists are also academics and work for colleges and universities, some are employed by other agencies. Forensic anthropology is an active area of applied biological anthropology and a career that is useful all over the world.1

In a legal situation, forensic anthropology is the application of anthropology’s anatomical science and its different subfields, such as forensic archaeology and forensic taphonomy. In the event of an aircraft accident, a forensic anthropologist can assist in the identification of deceased victims whose remains have deteriorated, been burned, mangled, or otherwise become unrecognizable. In addition to investigating and documenting genocide and mass graves, forensic anthropologists play a key role in the investigation and documentation of genocide and mass graves. Forensic anthropologists, like forensic pathologists, forensic dentists, and homicide investigators, frequently testify in court as expert witnesses. A forensic anthropologist can potentially establish a person’s age, sex, size, and race using physical evidence found on a skeleton. Skeletal abnormalities can be used by forensic anthropologists to detect the cause of death, past trauma such as broken bones or medical treatments, and diseases such as bone cancer, in addition to identifying physical traits of the deceased. The methods for identifying a person from a skeleton are based on the work of numerous anthropologists and the study of human skeletal characteristics in the past.3

Estimates based on physical traits can be made by the gathering of thousands of specimens and the examination of differences within a group. A set of remains can potentially be identified using these. During the twentieth century, forensic anthropology evolved into a fully recognized forensic specialty with trained anthropologists and various research institutes collecting data on decomposition and its effects on the skeleton. In today’s forensic realm, forensic anthropology is a well-established science. When other physical qualities that may be used to identify a body no longer exist, anthropologists are relied upon to analyze remains and assist in the identification of individuals from bones. To identify remains based on skeletal traits, forensic anthropologists collaborate with forensic pathologists. If the victim is missing for an extended period of time or is devoured by scavengers, the flesh marks required for identification are lost, making routine identification difficult, if not impossible. Forensic anthropologists can offer physical characteristics of a missing individual to be entered into databases such as the National Crime Information Center in the United States or INTERPOL’s yellow notice database.3

Aside from these responsibilities, forensic anthropologists frequently aid in the investigation of war crimes and mass death cases. Anthropologists have been tasked with assisting in the identification of victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, as well as victims of plane crashes like the Arrow Air Flight 1285 disaster and the USAir Flight 427 disaster, where the flesh had been vaporized or mangled to the point where normal identification was impossible. Anthropologists have also assisted in the identification of genocide victims in countries all over the world, often many years after the occurrence. War crimes anthropologists have helped investigate include the Rwandan genocide and the Srebrenica Genocide. Organizations like the Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe, the British Association for Forensic Anthropology, and the American Society of Forensic Anthropologists continue to establish guidelines for forensic anthropology’s improvement and growth of standards.3

History Of Forensic Anthropology

In Europe in the 1800s, the genesis of the ethnic groups of humans was intensely agitated. Scientists began with skull dimensions to make a distinction among those. The differences between male and female framework, and the evolution, aging, and fusing of bones were also examined, laying the structure for today’s awareness. Jeffries Wyman (1814–1874) represents a key early pathfinder of forensic anthropology evidence. Wyman had a medical degree from Harvard University and was the first administrator of the Peabody Museum of American Archeology and Ethnology in 1866. His evidence in the trial of Harvard professor of chemistry John W. Webster, accused of the murder of Dr. George Parkman, captivated widespread media, and scholarly notice. At Harvard in 1894, Thomas Dwight gave his lecture about the study of human skeletal remains in a lawful setting (i.e., forensic anthropology). Thus, he was rightfully hailed as the “Father of Forensic Anthropology.” Another nineteenth century murder trail brought well-known notice to anthropological testimony. In Chicago, Adolph Luetgert, a sausage producer, was hold responsible of assassinating his wife and disposing of the dead body by inserting it in a solution of potash in one of the factory vats. Investigation of the remains exposed minute remains that were bought to the notice of Dorsey of the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago. In the Luetgert trial of 1897–1898, Dorsey testified that the small remains recovered from material connected with the sausage vat were matched from a human female. His testimony was cruelly blamed by defense expert who argued that such determinations could not be through with poise from such minor evidence. In 1932, the FBI declared the opening of its first crime lab. The Smithsonian Institute became a working partner, aiding in the recognition of human remains. In 1939, the FBI published’ Guide to the Identification of Human Skeletal Material”.4

Anthropologist William Krogman made available his book, “of Guide to the Identification of Human Skeletal Material,” in 1962. Forensic anthropologists use this textbook even today. “Skeletal age change sin young American males” was in print in 1954 by Tom Mckern and T. Dale Stewart. In this report, Mckern and Stewart recognized skeletal aging approach based on facts from skeletal remains of Korean War military. In the early 1960s, the computer was discovered; this enabled forensic anthropologists to use discriminant purpose study, a statistical system to categorize sex and origin of skeletal remains. More recently, a new practice in DNA originated in the mitochondria of cells has been used in detection. Thomas Wingate Todd was in charge for the compilation of human skeletons in 1912. In total, Todd got skulls and skeletons of humans, anthropoids and other mammals. Todd also developed age estimation based on physical individuality of the pubic symphysis. Though the principles have been bringing up to dated, these estimates a range of skeletonized remains.4

The acknowledgement of anthropology as a distinct scientific field, as well as the emergence of physical anthropology, led to the application of anthropology in forensic investigations of human remains. During the early years of the twentieth century, the field of anthropology fought to gain acceptance as a valid science, beginning in the United States. Earnest Hooton established the field of physical anthropology and was the first physical anthropologist in the United States to hold a full-time teaching post. Along with its founder Ale Hrdlika, he was a member of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists’ organizational committee. During the early twentieth century, Hooton’s students established some of the earliest doctoral programs in physical anthropology. Hooton was a proponent of criminal anthropology in addition to physical anthropology.3

Criminal anthropologists believed that phrenology and physiognomy could link a person’s behavior to specific physical traits, which is now regarded a pseudoscience. The eugenics movement, which was prominent at the time, inspired the use of criminal anthropology to try to explain some criminal habits. Because of these concepts, skeletal differences were studied more seriously, eventually leading to the development of anthropometry and Alphonse Bertillon’s Bertillon method of skeletal measuring. The examination of this data aided anthropologists in their understanding of the human skeleton and the various skeletal variations that can exist. Thomas Wingate Todd, another early anthropologist, was largely responsible for the development of the first substantial collection of human bones in 1912. Todd got 3,300 human skulls and bones, 600 anthropoid skulls and skeletons, and 3,000 mammalian skulls and skeletons in all. Todd’s contributions to anthropology are still being used today, and include studies on suture closures on the skull and the time of teeth eruption in the jaw. Krogman was the first anthropologist to actively publicize anthropologists’ potential forensic value, including placing ads in the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin informing agencies of anthropologists’ abilities to assist in the identification of skeletal remains during the 1940s. During this time, federal agencies, like the FBI, began to use anthropologists on a more formal basis. During the Korean Battle in the 1950s, the United States Army Quartermaster Corps used forensic anthropologists to identify war casualties.3

CAREER CONNECTION

Forensic Pathology and Forensic Anthropology

A forensic pathologist (also known as a medical examiner) is a medically trained physician who has been specifically trained in pathology to examine the bodies of the deceased to determine the cause of death. A forensic pathologist applies his or her understanding of disease as well as toxins, blood and DNA analysis, firearms and ballistics, and other factors to assess the cause and manner of death. At times, a forensic pathologist will be called to testify under oath in situations that involve a possible crime. Forensic pathology is a field that has received much media attention on television shows or following a high-profile death.2

While forensic pathologists are responsible for determining whether the cause of someone’s death was natural, a suicide, accidental, or a homicide, there are times when uncovering the cause of death is more complex, and other skills are needed. Forensic anthropology brings the tools and knowledge of physical anthropology and human osteology (the study of the skeleton) to the task of investigating a death. A forensic anthropologist assists medical and legal professionals in identifying human remains. The science behind forensic anthropology involves the study of archaeological excavation; the examination of hair; an understanding of plants, insects, and footprints; the ability to determine how much time has elapsed since the person died; the analysis of past medical history and toxicology; the ability to determine whether there are any postmortem injuries or alterations of the skeleton; and the identification of the decedent (deceased person) using skeletal and dental evidence.2

Due to the extensive knowledge and understanding of excavation techniques, a forensic anthropologist is an integral and invaluable team member to have on-site when investigating a crime scene, especially when the recovery of human skeletal remains is involved. When remains are bought to a forensic anthropologist for examination, he or she must first determine whether the remains are in fact human. Once the remains have been identified as belonging to a person and not to an animal, the next step is to approximate the individual’s age, sex, race, and height. The forensic anthropologist does not determine the cause of death, but rather provides information to the forensic pathologist, who will use all of the data collected to make a final determination regarding the cause of death.2

Forensic Entomology

Forensic entomology is a very narrow field of forensic science that focuses on the life cycle of bugs. When a dead body has been left out in the elements and allowed to decompose, the investigative challenge is not only to identify the body, but to establish the time of death. Once a body has decomposed, the process of determining time of death can be aided by a forensic entomologist. As discussed in a previous chapter, these experts look at the bugs that live on a decomposing body through the various stages of their life cycle. From these life-cycle calculations, scientists are sometimes able to offer and estimate relative time of death.5

Forensic Odontology

To paraphrase the description provided by Dr. Leung (2008), forensic odontology is essentially forensic dentistry and includes the expert analysis of various aspects of teeth for the purposes of investigation. Since the advent of dental x-rays, dental records have been used as a reliable source of comparison data to confirm the identity of bodies that were otherwise too damaged or too decomposed to identify through other means. The development of DNA and the ability to use DNA in the identification of badly decomposed human remains has made identity through dental records less critical. That said, even in a badly decomposed or damaged corpse, teeth can retain DNA material inside the tooth, allowing it to remain a viable source of post-mortem DNA evidence.5

Beyond the identification of dead bodies, forensic odontology can sometimes also provide investigators with assistance in confirming the possible identity of a suspect responsible for a bite mark. This comparison is done by the examination and photographic preservation of the bite mark on a victim or an object, and the subsequent matching of the details in that bite mark configuration to a dental mold showing the bite configuration of a known suspect’s teeth. Although bite mark comparison has been in practice for over fifty years there remain questions to the reliability for exact matching of an unknown bite mark to a suspect.5

References:

1. Katie Nelson, Lara Braff, Beth Shook and Kelsie Aguilera, “Introduction to Biological Anthropology” In Explorations, ed. Beth Shook, Katie Nelson, Kelsie Aguilera and Lara Braff (Arlington: American Anthropological Association, 2019). https://pressbooksdev.oer.hawaii.edu/explorationsbioanth/chapter/osteology/.

2. Layci Harrison, Anatomical Basis of Injury (Houston: University of Houston, 2019). https://uhlibraries.pressbooks.pub/atpanatomy/front-matter/about-this-book/.

3. Manisha Dash, “Forensic Anthropology: An Overview,” Journal of Forensic Research 13 (2022). https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/forensic-anthropology-an-overview-85859.html.

4. Purva Wagisha Upadhyay and Amarnath Mishra, “Forensic Anthropology” in Biological Anthropology – Applications and Case Studies, ed. Alessio Vovlas (London: IntechOpen, 2021). https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/73372.

5. Rod Gehl and Darryl Plecas, Introduction to Criminal Investigation: Processes, Practices and Thinking (New Westminster, BC: Justice Institute of British Columbia, 2017). https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/criminalinvestigation/ CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure Attributions:

Figure 1.1 Untitled by Mission de I’ONU au Mali – UN Mission in Mali/Gema Cortes is under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 License; Untitled in Middle East by Mark Fischer is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.0 License; Smiling Blonde Girl by Egor Gribanov from St. Petersburg, Russia is under a CC BY 2.0 License; Steppe Gobi Desert Mongolia Nomadic Man Travel at MaxPixel has been designated to the public domain (CC0).

Figure 1.2 Holism original to Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology by Mary Nelson is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure 1.3 Untitled by Luke Berhow is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure 1.4 Statue of Zhang Qian in Chenggu by Debi Lander is used with permission.

Figure 1.5 Ibn Batuta en Égypte by Léon Benett is in the public domain.

Figure 1.6 Charles Darwin Standing by unknown photographer is in the public domain.

Figure 1.7 FranzBoas by unknown photographer is in the public domain. This image is from the collection of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, Negative 79-796.

Figure 1.8 Subdisciplines of anthropology original to Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology by Mary Nelson is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure 1.9 Margaret Mead – Image from page 47 of “A brief expedition into science at the American Museum of Natural History” (1969) by Internet Archive Book Images is in the public domain.

Figure 1.10 Babytalk by Torbein Rønning is under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 License.

Figure 1.11 Jerycho8 by A. Sobkowski has been designated to the public domain (CC0).

Figure 1.12 Chimpanzees by Klaus Post is under a CC BY 2.0 License.

Figure 1.13 Untitled at pxhere.com has been designated to the public domain (CC0).

Figure 1.14 PEF-with-mom-and-baby—Quy-Ton-12-2003 1-1-310 by Cjmadson is under a CC BY 3.0 License.

Figure 1.15 Head-Measurer of Tremearne (side view) by A.J.N. Tremearne, Man 15 (1914): 87-88 is in the public domain.

Figure 1.16 Subfields of biological anthropology original to Explorations: An Open Invitation to Biological Anthropology by Mary Nelson is under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Figure 1.17 Mountain gorilla finger detail.KMRA by Kurt Ackermann (English Wikipedia username KMRA) is under a CC BY 2.5 License.

Figure 1.18 Donald Johanson 2009 by Julesasu has been designated to the public domain (CC0 1.0).

Figure 1.19 Oetzi the Iceman Rekonstruktion 1 by Thilo Parg is under a CC BY-SA 3.0 License.

Figure 1.20 Untitled by Presidencia El Salvador has been designated to the public domain (CC0 1.0).