2 The Protestant Reformation

Discontent with the Roman Catholic Church

The Protestant Reformation was the schism within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other early Protestants.

Learning Objectives

Explain the main motivating factors behind the Protestant Reformation

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Reformation began as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church, by priests who opposed what they perceived as false doctrines and ecclesiastic malpractice.

- Following the breakdown of monastic institutions and scholasticism in late medieval Europe, accentuated by the Avignon Papacy, the Papal Schism, and the failure of the Conciliar movement, the 16th century saw a great cultural debate about religious reforms and later fundamental religious values. John Wycliffe and Jan Hus were early opponents of papal authority, and their work and views paved the way for the Reformation.

- Martin Luther was a seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation who strongly disputed the sale of indulgences. His Ninety-Five Theses criticized many of the doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church.

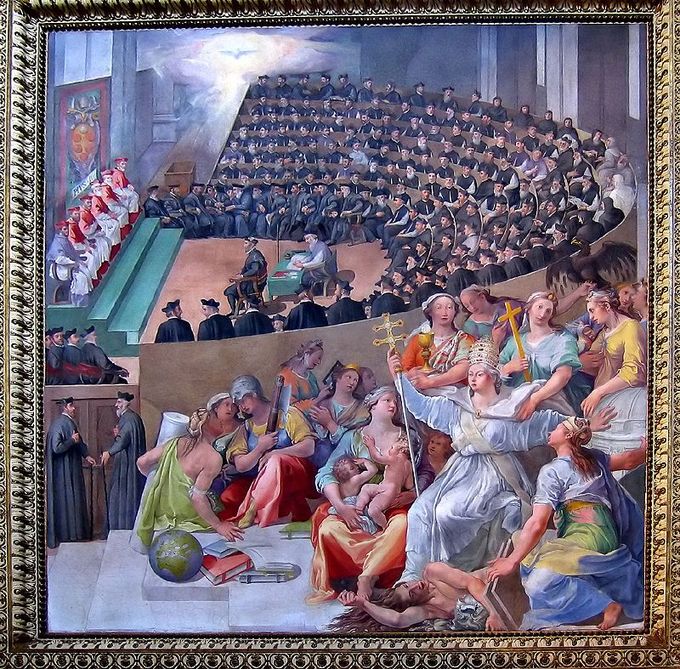

- The Roman Catholic Church responded with a Counter-Reformation spearheaded by the new order of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), specifically organized to counter the Protestant movement.

Key Terms

- Conciliar movement: A reform movement in the 14th-, 15th-, and 16th-century Catholic Church that held that supreme authority in the church resided with an Ecumenical council, apart from, or even against, the pope. The movement emerged in response to the Western Schism between rival popes in Rome and Avignon.

- the Western Schism: A split within the Catholic Church from 1378 to 1418, when several men simultaneously claimed to be the true pope.

- doctrine: List of beliefs and teachings by the church.

- ecclesiastic: One who adheres to a church-based philosophy.

- indulgences: In Catholic theology, a remission of the punishment that would otherwise be inflicted for a previously forgiven sin as a natural consequence of having sinned. They are granted for specific good works and prayers in proportion to the devotion with which those good works are performed or prayers recited.

- Council of Trent: Council of the Roman Catholic Church set up in Trento, Italy, in direct response to the Reformation.

The Protestant Reformation, often referred to simply as the Reformation, was a schism from the Roman Catholic Church initiated by Martin Luther and continued by other early Protestant reformers in Europe in the 16th century.

Although there had been significant earlier attempts to reform the Roman Catholic Church before Luther—such as those of Jan Hus, Geert Groote, Thomas A Kempis, Peter Waldo, and John Wycliffe—Martin Luther is widely acknowledged to have started the Reformation with his 1517 work The Ninety-Five Theses.

Luther began by criticizing the selling of indulgences, insisting that the pope had no authority over purgatory and that the Catholic doctrine of the merits of the saints had no foundation in the gospel. The Protestant position, however, would come to incorporate doctrinal changes such as sola scriptura (by the scripture alone) and sola fide (by faith alone). The core motivation behind these changes was theological, though many other factors played a part, including the rise of nationalism, the Western Schism that eroded faith in the papacy, the perceived corruption of the Roman Curia, the impact of humanism, and the new learning of the Renaissance that questioned much traditional thought.

Roots of Unrest

Following the breakdown of monastic institutions and scholasticism in late medieval Europe, accentuated by the Avignon Papacy, the Papal Schism, and the failure of the Conciliar movement, the 16th century saw a great cultural debate about religious reforms and later fundamental religious values. These issues initiated wars between princes, uprisings among peasants, and widespread concern over corruption in the Church, which sparked many reform movement within the church.

These reformist movements occurred in conjunction with economic, political, and demographic forces that contributed to a growing disaffection with the wealth and power of the elite clergy, sensitizing the population to the financial and moral corruption of the secular Renaissance church.

The major individualistic reform movements that revolted against medieval scholasticism and the institutions that underpinned it were humanism, devotionalism, and the observantine tradition. In Germany, “the modern way,” or devotionalism, caught on in the universities, requiring a redefinition of God, who was no longer a rational governing principle but an arbitrary, unknowable will that could not be limited. God was now a ruler, and religion would be more fervent and emotional. Thus, the ensuing revival of Augustinian theology, stating that man cannot be saved by his own efforts but only by the grace of God, would erode the legitimacy of the rigid institutions of the church meant to provide a channel for man to do good works and get into heaven.

Humanism, however, was more of an educational reform movement with origins in the Renaissance’s revival of classical learning and thought. A revolt against Aristotelian logic, it placed great emphasis on reforming individuals through eloquence as opposed to reason. The European Renaissance laid the foundation for the Northern humanists in its reinforcement of the traditional use of Latin as the great unifying language of European culture. Since the breakdown of the philosophical foundations of scholasticism, the new nominalism did not bode well for an institutional church legitimized as an intermediary between man and God. New thinking favored the notion that no religious doctrine can be supported by philosophical arguments, eroding the old alliance between reason and faith of the medieval period laid out by Thomas Aquinas.

The great rise of the burghers (merchant class) and their desire to run their new businesses free of institutional barriers or outmoded cultural practices contributed to the appeal of humanist individualism. To many, papal institutions were rigid, especially regarding their views on just price and usury. In the north, burghers and monarchs were united in their frustration for not paying any taxes to the nation, but collecting taxes from subjects and sending the revenues disproportionately to the pope in Italy.

Early Attempts at Reform

The first of a series of disruptive and new perspectives came from John Wycliffe at Oxford University, one of the earliest opponents of papal authority influencing secular power and an early advocate for translation of the Bible into the common language. Jan Hus at the University of Prague was a follower of Wycliffe and similarly objected to some of the practices of the Roman Catholic Church. Hus wanted liturgy in the language of the people (i.e. Czech), married priests, and to eliminate indulgences and the idea of purgatory.

Hus spoke out against indulgences in 1412 when he delivered an address entitled Quaestio magistri Johannis Hus de indulgentiis. It was taken literally from the last chapter of Wycliffe’s book, De ecclesia, and his treatise, De absolutione a pena et culpa. Hus asserted that no pope or bishop had the right to take up the sword in the name of the Church; he should pray for his enemies and bless those that curse him; man obtains forgiveness of sins by true repentance, not money. The doctors of the theological faculty replied, but without success. A few days afterward, some of Hus’s followers burnt the papal bulls. Hus, they said, should be obeyed rather than the Church, which they considered a fraudulent mob of adulterers and Simonists.

In response, three men from the lower classes who openly called the indulgences a fraud were beheaded. They were later considered the first martyrs of the Hussite Church. In the meantime, the faculty had condemned the forty-five articles and added several other theses, deemed heretical, that had originated with Hus. The king forbade the teaching of these articles, but neither Hus nor the university complied with the ruling, requesting that the articles should first be proven to be un-scriptural. The tumults at Prague had stirred up a sensation; papal legates and Archbishop Albik tried to persuade Hus to give up his opposition to the papal bulls, and the king made an unsuccessful attempt to reconcile the two parties.

Hus was later condemned and burned at the stake despite promise of safe-conduct when he voiced his views to church leaders at the Council of Constance (1414–1418). Wycliffe, who died in 1384, was also declared a heretic by the Council of Constance, and his corpse was exhumed and burned.

The Creation of New Protestant Churches

The Reformation led to the creation of new national Protestant churches. The largest of the new church’s groupings were the Lutherans (mostly in Germany, the Baltics, and Scandinavia) and the Reformed churches (mostly in Germany, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Scotland).

Response from the Catholic Church to the Reformation

The Roman Catholic Church responded with a Counter-Reformation initiated by the Council of Trent and spearheaded by the new order of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), specifically organized to counter the Protestant movement. In general, Northern Europe, with the exception of most of Ireland, turned Protestant. Southern Europe remained Roman Catholic, while Central Europe was a site of fierce conflict escalating to full-scale war.

Luther and Protestantism

Martin Luther was a seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation; he strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God’s punishment for sin could be purchased with money, famously argued in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517.

Learning Objectives

Describe Luther’s criticisms of the Catholic Church

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Martin Luther was a German professor of theology, composer, priest, monk and seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation.

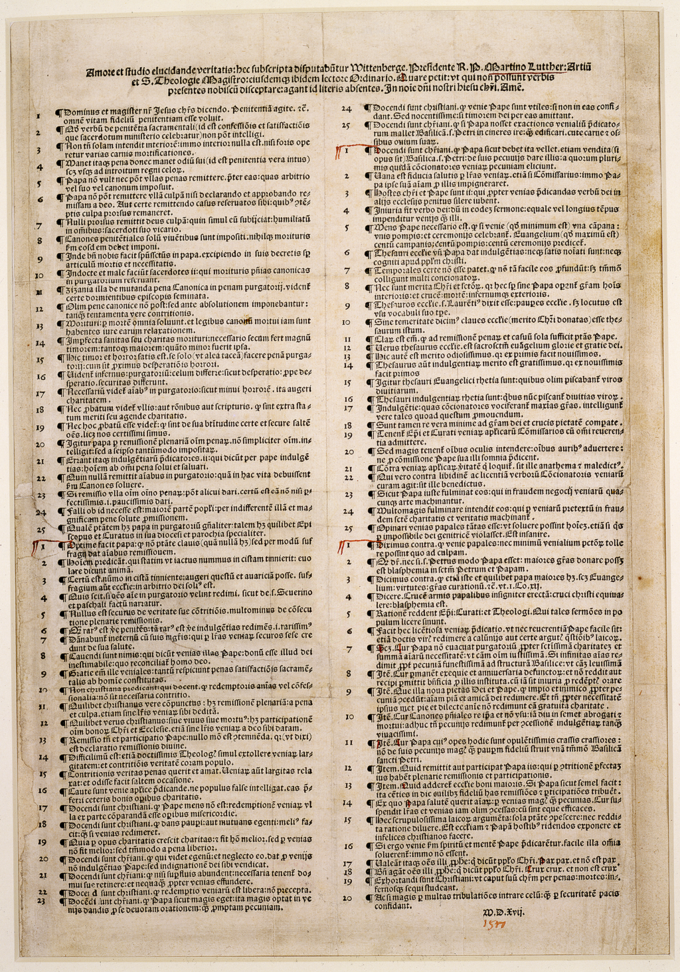

- Luther strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God’s punishment for sin could be purchased with money, called indulgences, which he argued in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517.

- When confronted by the church for his critiques, he refused to renounce his writings and was excommunicated by the pope and deemed an outlaw by the emperor.

- Luther’s translation of the Bible into the vernacular made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture.

Key Terms

- indulgences: A way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins, usually through the saying of prayers or good works, which during the middle ages included paying for church buildings or other projects.

- excommunication: An institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it.

- Ninety-five Theses: A list of propositions for an academic disputation written by Martin Luther in 1517. They advanced Luther’s positions against what he saw as abusive practices by preachers selling plenary indulgences, which were certificates that would reduce the temporal punishment for sins committed by the purchaser or their loved ones in purgatory.

Overview

Martin Luther (November 10, 1483–February 18, 1546) was a German professor of theology, composer, priest, monk and seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation. Luther came to reject several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God’s punishment for sin could be purchased with money, proposing an academic discussion of the practice and efficacy of indulgences in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517. His refusal to renounce all of his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521 resulted in his excommunication by the pope and condemnation as an outlaw by the emperor.

Luther taught that salvation and, subsequently, eternal life are not earned by good deeds but are received only as the free gift of God’s grace through the believer’s faith in Jesus Christ as redeemer from sin. His theology challenged the authority and office of the pope by teaching that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge from God, and opposed priestly intervention for the forgiveness of sins by considering all baptized Christians to be a holy priesthood. Those who identify with these, and all of Luther’s wider teachings, are called Lutherans, though Luther insisted on Christian or Evangelical as the only acceptable names for individuals who professed Christ.

His translation of the Bible into the vernacular (instead of Latin) made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation, and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible. His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches. His marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage, allowing Protestant clergy to marry.

In two of his later works, Luther expressed antagonistic views toward Jews, writing that Jewish homes and synagogues should be destroyed, their money confiscated, and their liberty curtailed. Condemned by virtually every Lutheran denomination, these statements and their influence on antisemitism have contributed to his controversial status.

Personal Life

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luther and his wife Margarethe on November 10, 1483, in Eisleben, Saxony, then part of the Holy Roman Empire. Hans Luther was ambitious for himself and his family, and he was determined to see Martin, his eldest son, become a lawyer.

In 1501, at the age of nineteen, Martin entered the University of Erfurt. In accordance with his father’s wishes, he enrolled in law school at the same university that year, but dropped out almost immediately, believing that law represented uncertainty. Luther sought assurances about life and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle, William of Ockham, and Gabriel Biel.

He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomaeus Arnoldi von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers and to test everything himself by experience. Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason but no assurance about loving God, which to Luther was more important. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he thereafter developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter’s emphasis on reason. For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation, he believed, and scripture therefore became increasingly important to him.

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to fasting, long hours in prayer, pilgrimage, and frequent confession. In 1507, he was ordained to the priesthood, and in 1508, von Staupitz, first dean of the newly founded University of Wittenberg, sent for Luther to teach theology. He was made provincial vicar of Saxony and Thuringia by his religious order in 1515. This meant he was to visit and oversee eleven monasteries in his province.

Start of the Reformation

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar and papal commissioner for indulgences, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money to rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Roman Catholic theology stated that faith alone, whether fiduciary or dogmatic, cannot justify man; justification rather depends only on such faith as is active in charity and good works. The benefits of good works could be obtained by donating money to the church.

On October 31, 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albert of Mainz, protesting the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his “Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” which came to be known as the Ninety-five Theses. Historian Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church, but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly “searching, rather than doctrinaire.” Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks, “Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?”

The first thesis has become famous: “When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said, ‘Repent,’ he willed the entire life of believers to be one of repentance.” In the first few theses Luther develops the idea of repentance as the Christian’s inner struggle with sin rather than the external system of sacramental confession.

In theses 41–47 Luther begins to criticize indulgences on the basis that they discourage works of mercy by those who purchase them. Here he begins to use the phrase, “Christians are to be taught…” to state how he thinks people should be instructed on the value of indulgences. They should be taught that giving to the poor is incomparably more important than buying indulgences, that buying an indulgence rather than giving to the poor invites God’s wrath, and that doing good works makes a person better while buying indulgences does not.

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Johann Tetzel that “As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.” He insisted that, since forgiveness was God’s alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Luther closes the Theses by exhorting Christians to imitate Christ even if it brings pain and suffering, because enduring punishment and entering heaven is preferable to false security.

It was not until January 1518 that friends of Luther translated the Ninety-five Theses from Latin into German and printed and widely copied it, making the controversy one of the first to be aided by the printing press. Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months, they had spread throughout Europe.

Excommunication and Later Life

On June 15, 1520, the pope warned Luther, with the papal bull Exsurge Domine, that he risked ex-communication unless he recanted forty-one sentences drawn from his writings, including the Ninety-five Theses, within sixty days. That autumn, Johann Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Karl von Miltitz, a papal nuncio, attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the pope a copy of On the Freedom of a Christian in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretals at Wittenberg on December 10, 1520, an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles. As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X on January 3, 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.

The enforcement of the ban on the Ninety-five Theses fell to the secular authorities. On April 18, 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the Diet of Worms. This was a general assembly of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire that took place in Worms, a town on the Rhine. It was conducted from January 28 to May 25, 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, obtained a safe conduct for Luther to and from the meeting.

Johann Eck, speaking on behalf of the empire as assistant of the Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with copies of his writings laid out on a table and asked him if the books were his, and whether he stood by their contents. Luther confirmed he was their author, but requested time to think about the answer to the second question. He prayed, consulted friends, and gave his response the next day:

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.

Over the next five days, private conferences were held to determine Luther’s fate. The emperor presented the final draft of the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521, which declared Luther an outlaw, banned his literature, and required his arrest: “We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic.” It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter, and permitted anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence.

By 1526, Luther found himself increasingly occupied in organizing a new church, later called the Lutheran Church, and for the rest of his life would continue building the Protestant movement.

An apoplectic stroke on February 18, 1546, deprived him of his speech, and he died shortly afterwards, at 2:45 a.m., aged sixty-two, in Eisleben, the city of his birth. He was buried in the Castle Church in Wittenberg, beneath the pulpit.

Reluctant Revolutionary: PBS Documentary about Martin Luther the “Reluctant Revolutionary.” Luther opposed the Catholic Church’s practices and in 1517 he wrote his Ninety-five Theses, which detailed the church’s failings. His actions led to the start of the Protestant Revolution.

Calvinism

Calvinism is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice of John Calvin and is characterized by the doctrine of predestination in the salvation of souls.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast Calvinism with Lutheranism

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Calvinism is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice of John Calvin and other Reformation -era theologians.

- Calvin’s theological critiques mostly broke with the Roman Catholic Church, but he differed from Luther on certain theological points, such as the idea that Christ died only for the elect instead of all humanity, like Luther believed.

- Calvin’s “Ordinances” of 1541 involved a collaboration of church affairs with the Geneva city council and consistory to bring morality to all areas of life. Geneva became the center of Protestantism.

- Protestantism also spread into France, where the Protestants were derisively nicknamed ” Huguenots,” and this touched off decades of warfare in France.

- Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536–1559) was one of the most influential theologies of the era and was written as an introductory textbook on the Protestant faith.

Key Terms

- Five Points of Calvinism: The basic theological tenets of Calvinism.

- Huguenots: A name for French Protestants, originally a derisive term.

- predestination: The doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul.

Overview

Calvinism is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice of John Calvin and other Reformation-era theologians.

Calvinists broke with the Roman Catholic Church but differed from Lutherans on the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, theories of worship, and the use of God’s law for believers, among other things. Calvinism can be a misleading term because the religious tradition it denotes is and has always been diverse, with a wide range of influences rather than a single founder. The movement was first called Calvinism by Lutherans who opposed it, and many within the tradition would prefer to use the word Reformed. While the Reformed theological tradition addresses all of the traditional topics of Christian theology, the word Calvinism is sometimes used to refer to particular Calvinist views on soteriology (the saving of the soul from sin and death) and predestination, which are summarized in part by the Five Points of Calvinism. Some have also argued that Calvinism as a whole stresses the sovereignty or rule of God in all things, including salvation. An important tenet of Calvinism, which differs from Lutheranism, is that God only saves the “elect,” a predestined group of individuals, and that these elect are essentially guaranteed salvation, but everyone else is damned.

Origins and Rise of Calvinism

First-generation Reformed theologians include Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531), Martin Bucer (1491–1551), Wolfgang Capito (1478–1541), John Oecolampadius (1482–1531), and Guillaume Farel (1489–1565). These reformers came from diverse academic backgrounds, but later distinctions within Reformed theology can already be detected in their thought, especially the priority of scripture as a source of authority. Scripture was also viewed as a unified whole, which led to a covenantal theology of the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper as visible signs of the covenant of grace. Another Reformed distinctive present in these theologians was their denial of the bodily presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. Each of these theologians also understood salvation to be by grace alone, and affirmed a doctrine of particular election (the teaching that some people are chosen by God for salvation). Martin Luther and his successor Philipp Melanchthon were undoubtedly significant influences on these theologians, and to a larger extent later Reformed theologians. The doctrine of justification by faith alone was a direct inheritance from Luther.

Following the excommunication of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the pope, the work and writings of John Calvin were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland, Hungary, Germany, and elsewhere. After the expulsion of Geneva’s bishop in 1526, and the unsuccessful attempts of the Berne reformer Guillaume (William) Farel, Calvin was asked to use the organizational skill he had gathered as a student of law to discipline the “fallen city.” His “Ordinances” of 1541 involved a collaboration of church affairs with the city council and consistory to bring morality to all areas of life. After the establishment of the Geneva academy in 1559, Geneva became the unofficial capital of the Protestant movement, providing refuge for Protestant exiles from all over Europe and educating them as Calvinist missionaries. These missionaries dispersed Calvinism widely, and formed the French Huguenots in Calvin’s own lifetime, as well as caused the conversion of Scotland under the leadership of the cantankerous John Knox in 1560. The faith continued to spread after Calvin’s death in 1563, and had reached as far as Constantinople by the start of the 17th century.

Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536–1559) was one of the most influential theologies of the era. The book was written as an introductory textbook on the Protestant faith for those with some previous knowledge of theology, and covered a broad range of theological topics, from the doctrines of church and sacraments to justification by faith alone and Christian liberty. It vigorously attacked the teachings Calvin considered unorthodox, particularly Roman Catholicism, to which Calvin says he had been “strongly devoted” before his conversion to Protestantism.

Controversies in France

Protestantism spread into France, where the Protestants were derisively nicknamed “Huguenots,” and this touched off decades of warfare in France, after initial support by Henry of Navarre was lost due to the “Night of the Placards” affair. Many French Huguenots, however, still contributed to the Protestant movement, including many who emigrated to the English colonies.

Though he was not personally interested in religious reform, Francis I (1515–1547) initially maintained an attitude of tolerance arising from his interest in the humanist movement. This changed in 1534 with the Affair of the Placards. In this act, Protestants denounced the mass in placards that appeared across France, even reaching the royal apartments. The issue of religious faith having been thrown into the arena of politics, Francis was prompted to view the movement as a threat to the kingdom’s stability. This led to the first major phase of anti-Protestant persecution in France, in which the Chambre Ardente (“Burning Chamber”) was established within the Parliament of Paris to handle the rise in prosecutions for heresy. Several thousand French Protestants fled the country during this time, most notably John Calvin, who settled in Geneva.

Calvin continued to take an interest in the religious affairs of his native land and, from his base in Geneva, beyond the reach of the French king, regularly trained pastors to lead congregations in France. Despite heavy persecution by Henry II, the Reformed Church of France, largely Calvinist in direction, made steady progress across large sections of the nation, in the urban bourgeoisie and parts of the aristocracy, appealing to people alienated by the obduracy and the complacency of the Catholic establishment.

Calvinist Theology

The “Five Points of Calvinism” summarize the faith’s basic tenets, although some historians contend that it distorts the nuance of Calvin’s own theological positions.

The Five Points:

- “Total depravity” asserts that as a consequence of the fall of man into sin, every person is enslaved to sin. People are not by nature inclined to love God, but rather to serve their own interests and to reject the rule of God. Thus, all people by their own faculties are morally unable to choose to follow God and be saved because they are unwilling to do so out of the necessity of their own natures.

- “Unconditional election” asserts that God has chosen from eternity those whom he will bring to himself not based on foreseen virtue, merit, or faith in those people; rather, his choice is unconditionally grounded in his mercy alone. God has chosen from eternity to extend mercy to those he has chosen and to withhold mercy from those not chosen. Those chosen receive salvation through Christ alone. Those not chosen receive the just wrath that is warranted for their sins against God.

- “Limited atonement” asserts that Jesus’s substitutionary atonement was definite and certain in its purpose and in what it accomplished. This implies that only the sins of the elect were atoned for by Jesus’s death. Calvinists do not believe, however, that the atonement is limited in its value or power, but rather that the atonement is limited in the sense that it is intended for some and not all. All Calvinists would affirm that the blood of Christ was sufficient to pay for every single human being IF it were God’s intention to save every single human being.

- “Irresistible grace” asserts that the saving grace of God is effectually applied to those whom he has determined to save (that is, the elect) and overcomes their resistance to obeying the call of the gospel, bringing them to a saving faith. This means that when God sovereignly purposes to save someone, that individual certainly will be saved. The doctrine holds that this purposeful influence of God’s Holy Spirit cannot be resisted.

- “Perseverance of the saints” asserts that since God is sovereign and his will cannot be frustrated by humans or anything else, those whom God has called into communion with himself will continue in faith until the end.

The Anabaptists

The Anabaptists were a group of radical religious reformists formed in Switzerland who suffered violent persecution by both Roman Catholics and Protestants.

Learning Objectives

Explain why the Anabaptists were ostracized by much of Europe

Key Takeaways

Key Points

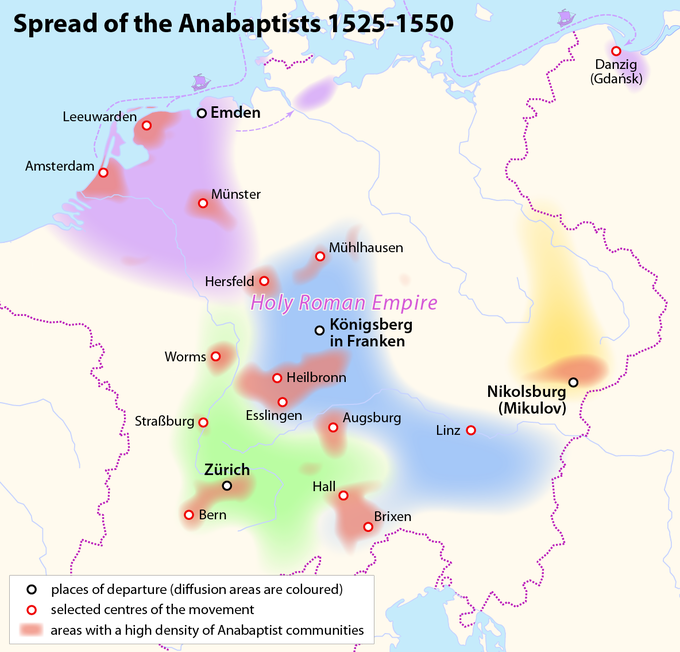

- Anabaptists are Christians who believe in delaying baptism until the candidate confesses his or her faith in Christ, as opposed to being baptized as an infant.

- Anabaptists were heavily persecuted during the 16th century and into the 17th century by both Protestants and Roman Catholics, including being drowned and burned at the stake.

- Anabaptists were often in conflict with civil society because part of their belief was to follow scripture at all costs, no matter the wishes of secular authority.

- Continuing persecution in Europe was largely responsible for the mass emigrations to North America by Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites, some of the major branches of Anabaptists.

Key Terms

- Ulrich Zwingli: A leader of the Reformation in Switzerland who clashed with the Anabaptists.

- infant baptism: The practice of baptizing infants or young children, sometimes contrasted with what is called “believer’s baptism,” which is the religious practice of baptizing only individuals who personally confess faith in Jesus.

- Magisterial Protestants: A phrase that names the manner in which the Lutheran and Calvinist reformers related to secular authorities, such as princes, magistrates, or city councils; opposed to the Radical Protestants.

Overview

Anabaptism is a Christian movement that traces its origins to the Radical Reformation in Europe. Some consider this movement to be an offshoot of European Protestantism, while others see it as distinct.

Anabaptists are Christians who believe in delaying baptism until the candidate confesses his or her faith in Christ, as opposed to being baptized as an infant. The Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites are direct descendants of the movement. Schwarzenau Brethren, Bruderhof, and the Apostolic Christian Church are considered later developments among the Anabaptists.

The name Anabaptist means “one who baptizes again.” Their persecutors named them this, referring to the practice of baptizing persons when they converted or declared their faith in Christ, even if they had been “baptized” as infants. Anabaptists required that baptismal candidates be able to make a confession of faith that was freely chosen, and so rejected baptism of infants. The early members of this movement did not accept the name Anabaptist, claiming that infant baptism was not part of scripture and was therefore null and void. They said that baptizing self-confessed believers was their first true baptism. Balthasar Hubmaier wrote:

I have never taught Anabaptism…But the right baptism of Christ, which is preceded by teaching and oral confession of faith, I teach, and say that infant baptism is a robbery of the right baptism of Christ.

Anabaptists were heavily persecuted during the 16th century and into the 17th century because of their views on the nature of baptism and other issues, by both Magisterial Protestants and Roman Catholics.

Anabaptists were persecuted largely because of their interpretation of scripture that put them at odds with official state church interpretations and government. Most Anabaptists adhered to a literal interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount, which precluded taking oaths, participating in military actions, and participating in civil government. Some who practiced re-baptism, however, felt otherwise, and complied with these requirements of civil society. They were thus technically Anabaptists, even though conservative Amish, Mennonites, and Hutterites, and some historians, tend to consider them as outside of true Anabaptism.

Origins

Anabaptism in Switzerland began as an offshoot of the church reforms instigated by Ulrich Zwingli. As early as 1522 it became evident that Zwingli was on a path of reform preaching when he began to question or criticize such Catholic practices as tithes, the mass, and even infant baptism. Zwingli had gathered a group of reform-minded men around him, with whom he studied classical literature and the scriptures. However, some of these young men began to feel that Zwingli was not moving fast enough in his reform. The division between Zwingli and his more radical disciples became apparent in an October 1523 disputation held in Zurich. When the discussion of the mass was about to be ended without making any actual change in practice, Conrad Grebel stood up and asked “what should be done about the mass?” Zwingli responded by saying the council would make that decision. At this point, Simon Stumpf, a radical priest from Hongg, answered, saying, “The decision has already been made by the Spirit of God.”

This incident illustrated clearly that Zwingli and his more radical disciples had different expectations. To Zwingli, the reforms would only go as fast as the city council allowed them. To the radicals, the council had no right to make that decision, but rather the Bible was the final authority on church reform. Feeling frustrated, some of them began to meet on their own for Bible study. As early as 1523, William Reublin began to preach against infant baptism in villages surrounding Zurich, encouraging parents to not baptize their children.

The council ruled in this meeting that all who refused to baptize their infants within one week should be expelled from Zurich. Since Conrad Grebel had refused to baptize his daughter Rachel, born on January 5, 1525, the council decision was extremely personal to him and others who had not baptized their children. Thus, when sixteen of the radicals met on Saturday evening, January 21, 1525, the situation seemed particularly dark.

At that meeting Grebel baptized George Blaurock, and Blaurock in turn baptized several others immediately. These baptisms were the first “re-baptisms” known in the movement. This continues to be the most widely accepted date posited for the establishment of Anabaptism.

Anabaptism then spread to Tyrol (modern-day Austria), South Germany, Moravia, the Netherlands, and Belgium.

Persecutions

Roman Catholics and Protestants alike persecuted the Anabaptists, resorting to torture and execution in attempts to curb the growth of the movement. The Protestants under Zwingli were the first to persecute the Anabaptists, with Felix Manz becoming the first martyr in 1527. On May 20, 1527, Roman Catholic authorities executed Michael Sattler. King Ferdinand declared drowning (called the third baptism) “the best antidote to Anabaptism.” The Tudor regime, even the Protestant monarchs (Edward VI of England and Elizabeth I of England), persecuted Anabaptists, as they were deemed too radical and therefore a danger to religious stability. The persecution of Anabaptists was condoned by ancient laws of Theodosius I and Justinian I that were passed against the Donatists, which decreed the death penalty for any who practiced re-baptism. Martyrs Mirror, by Thieleman J. van Braght, describes the persecution and execution of thousands of Anabaptists in various parts of Europe between 1525 and 1660. Continuing persecution in Europe was largely responsible for the mass emigrations to North America by Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites.

The Anglican Church

Beginning with Henry VIII in the 16th century, the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church.

Learning Objectives

Describe the key developments of the English Reformation, distinguishing it from the wider reformation movement in Europe.

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The English Reformation was associated with the wider process of the European Protestant Reformation, though based on Henry VIII’s desire for an annulment of his marriage, it was at the outset more of a political affair than a theological dispute.

- Having been refused an annulment by the pope, Henry summoned parliament to deal with annulment, and the breaking with Rome proceeded.

- After Henry’s death his son Edward VI was crowned, and the reformation continued with the destruction and removal of decor and religious features, which changed the church forever.

- From 1553, under the reign of Henry’s Roman Catholic daughter, Mary I, the Reformation legislation was repealed, and Mary sought to achieve reunion with Rome.

- During Elizabeth I’s reign, support for her father’s idea of reforming the church continued with some minor adjustments. In this way, Elizabeth and her advisors aimed at a church that found a middle ground.

Key Terms

- Canon Law: The body of laws and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership), for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members.

- annulment: Legal term for declaring a marriage null and void. Unlike divorce, it is usually retroactive, meaning that this kind of marriage is considered to be invalid from the beginning, almost as if it had never taken place. They are closely associated with the Catholic Church, which does not permit divorce, teaching that marriage is a lifelong commitment that cannot be dissolved through divorce.

- nationalism: A belief, creed, or political ideology that involves an individual identifying with, or becoming attached to, one’s nation. In Europe, people were generally loyal to the church or to a local king or leader.

- Puritans: Group of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries founded by some exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England.

Overview

The English Reformation was a series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Roman Catholic Church. The English Reformation was, in part, associated with the wider process of the European Protestant Reformation, a religious and political movement that affected the practice of Christianity across most of Europe during this period. Many factors contributed to the process—the decline of feudalism and the rise of nationalism, the rise of the common law, the invention of the printing press and increased circulation of the Bible, and the transmission of new knowledge and ideas among scholars, the upper and middle classes, and readers in general. However, the various phases of the English Reformation, which also covered Wales and Ireland, were largely driven by changes in government policy, to which public opinion gradually accommodated itself.

Role of Henry VIII and Royal Marriages

Henry VIII ascended the English throne in 1509 at the age of seventeen. He made a dynastic marriage with Catherine of Aragon, widow of his brother, Arthur, in June 1509, just before his coronation on Midsummer’s Day. Unlike his father, who was secretive and conservative, the young Henry appeared the epitome of chivalry and sociability. An observant Roman Catholic, he heard up to five masses a day (except during the hunting season). Of “powerful but unoriginal mind,” he let himself be influenced by his advisors from whom he was never apart, by night or day. He was thus susceptible to whoever had his ear.

This contributed to a state of hostility between his young contemporaries and the Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. As long as Wolsey had his ear, Henry’s Roman Catholicism was secure; in 1521, he defended the Roman Catholic Church from Martin Luther’s accusations of heresy in a book he wrote—probably with considerable help from the conservative Bishop of Rochester, John Fisher—entitled The Defence of the Seven Sacraments, for which he was awarded the title “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X. Wolsey’s enemies at court included those who had been influenced by Lutheran ideas, among whom was the attractive, charismatic Anne Boleyn.

Anne arrived at court in 1522 from years in France, where she had been educated by Queen Claude of France. Anne served as maid of honor to Queen Catherine. She was a woman of “charm, style and wit, with will and savagery which made her a match for Henry.” By the late 1520s, Henry wanted his marriage to Catherine annulled. She had not produced a male heir who survived into adulthood, and Henry wanted a son to secure the Tudor dynasty.

Henry claimed that this lack of a male heir was because his marriage was “blighted in the eyes of God”; Catherine had been his late brother’s wife, and it was therefore against biblical teachings for Henry to have married her—a special dispensation from Pope Julius II had been needed to allow the wedding to take place. Henry argued that this had been wrong and that his marriage had never been valid. In 1527 Henry asked Pope Clement VII to annul the marriage, but the pope refused. According to Canon Law the pope cannot annul a marriage on the basis of a canonical impediment previously dispensed. Clement also feared the wrath of Catherine’s nephew, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, whose troops earlier that year had sacked Rome and briefly taken the pope prisoner.

In 1529 the king summoned parliament to deal with annulment, thus bringing together those who wanted reform but disagreed what form it should take; it became known as the Reformation Parliament. There were common lawyers who resented the privileges of the clergy to summon laity to their courts, and there were those who had been influenced by Lutheran evangelicalism and were hostile to the theology of Rome; Thomas Cromwell was both.

Cromwell was a lawyer and a member of Parliament—a Protestant who saw how Parliament could be used to advance the Royal Supremacy, which Henry wanted, and to further Protestant beliefs and practices Cromwell and his friends wanted.

The breaking of the power of Rome proceeded little by little starting in 1531. The Act in Restraint of Appeals, drafted by Cromwell, declared that clergy recognized Henry as the “sole protector and Supreme Head of the Church and clergy of England.” This declared England an independent country in every respect.

Meanwhile, having taken Anne to France on a pre-nuptial honeymoon, Henry married her in Westminster Abbey in January 1533.

Henry maintained a strong preference for traditional Catholic practices and, during his reign, Protestant reformers were unable to make many changes to the practices of the Church of England. Indeed, this part of Henry’s reign saw trials for heresy of Protestants as well as Roman Catholics.

The Reformation during Edward VI

When Henry died in 1547, his nine-year-old son, Edward VI, inherited the throne. Under King Edward VI, more Protestant-influenced forms of worship were adopted. Under the leadership of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, a more radical reformation proceeded. Cranmer introduced a series of religious reforms that revolutionized the English church from one that—while rejecting papal supremacy—remained essentially Catholic to one that was institutionally Protestant. All images in churches were to be dismantled. Stained glass, shrines, and statues were defaced or destroyed. Roods, and often their lofts and screens, were cut down and bells were taken down. Vestments were prohibited and either burned or sold. Chalices were melted down or sold. The requirement of the clergy to be celibate was lifted. Processions were banned and ashes and palms were prohibited.

A new pattern of worship was set out in the Book of Common Prayer (1549 and 1552). These were based on the older liturgy but influenced by Protestant principles. Cranmer’s formulation of the reformed religion, finally divesting the communion service of any notion of the real presence of God in the bread and the wine, effectively abolished the mass. The publication of Cranmer’s revised prayer book in 1552, supported by a second Act of Uniformity, “marked the arrival of the English Church at protestantism.” The prayer book of 1552 remains the foundation of the Church of England’s services. However, Cranmer was unable to implement all these reforms once it became clear in the spring of 1553 that King Edward, upon whom the whole Reformation in England depended, was dying.

Catholic Restoration

From 1553, under the reign of Henry’s Roman Catholic daughter, Mary I, the Reformation legislation was repealed, and Mary sought to achieve reunion with Rome. Her first Act of Parliament was to retroactively validate Henry’s marriage to her mother and so legitimize her claim to the throne.

After 1555, the initial reconciling tone of the regime began to harden. The medieval heresy laws were restored and 283 Protestants were burned at the stake for heresy. Full restoration of the Catholic faith in England to its pre-Reformation state would take time. Consequently, Protestants secretly ministering to underground congregations were planning for a long haul, a ministry of survival. However, Mary died in November 1558, childless and without having made provision for a Catholic to succeed her, undoing her work to restore the Catholic Church in England.

Elizabeth I

Following Mary’s death, her half-sister Elizabeth inherited the throne. One of the most important concerns during Elizabeth’s early reign was religion. Elizabeth could not be Catholic, as that church considered her illegitimate, being born of Anne Boleyn. At the same time, she had observed the turmoil brought about by Edward’s introduction of radical Protestant reforms. Communion with the Catholic Church was again severed by Elizabeth. Chiefly she supported her father’s idea of reforming the church, but she made some minor adjustments. In this way, Elizabeth and her advisors aimed at a church that included most opinions.

Elizabeth I and the Church of England: Dr. Tarnya Cooper, the National Portrait Gallery’s Chief Curator and Curator of Sixteenth Century Portraits, discusses Elizabeth I’s solution to religious turmoil in England.

Two groups were excluded in Elizabeth’s Church of England. Roman Catholics who remained loyal to the pope were not tolerated. They were, in fact, regarded as traitors because the pope had refused to accept Elizabeth as Queen of England. Roman Catholics were given the hard choice of being loyal either to their church or their country. For some priests it meant life on the run, and in some cases death for treason.

The other group not tolerated were people who wanted reform to go much further, and who finally gave up on the Church of England. They could no longer see it as a true church. They believed it had refused to obey the Bible, so they formed small groups of convinced believers outside the church. One of the main groups that formed during this time was the Puritans. The government responded with imprisonment and exile to try to crush these “separatists.”

Reformation and Division, 1530–1558: Professor Wrightson examines the various stages of the reformation in England, beginning with the legislative, as opposed to doctrinal, reformation begun by Henry VIII in a quest to settle the Tudor succession. Wrightson shows how the jurisdictional transformation of the royal supremacy over the church resulted, gradually, in the introduction of true religious change. The role played by various personalities at Henry’s court, and the manner in which the king’s own preferences shaped the doctrines of the Church of England, are considered. Doctrinal change, in line with continental Protestant developments, accelerated under Edward VI, but was reversed by Mary I. However, Wrightson suggests that, by this time, many aspects of Protestantism had been internalized by part of the English population, especially the young, and so the reformation could not wholly be undone by Mary’s short reign. The lecture ends with the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558, an event which presaged further religious change.

The French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion (1562–98) is the name of a period of fighting between French Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots).

Learning Objectives

Discuss how the patterns of warfare that took place in France affected the Huguenots

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Protestant ideas were first introduced to France during the reign of Francis I, who firmly opposed Protestantism, but continued to try and seek a middle course until the later stages of his regime.

- As the Huguenots gained influence and displayed their faith more openly, Roman Catholic hostility to them grew, spurning eight civil wars from 1562 to 1598.

- The wars were interrupted by breaks in peace that only lasted temporarily as the Huguenots’ trust in the Catholic throne diminished, and the violence became more severe and Protestant demands became grander.

- One of the most infamous events of the wars was the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were killed by Catholics.

- The pattern of warfare followed by brief periods of peace continued for nearly another quarter-century. The proclamation of the Edict of Nantes, and the subsequent protection of Huguenot rights, finally quelled the uprisings.

Key Terms

- Edict of Nantes: Issued on April 13, 1598, by Henry IV of France; granted the Huguenots substantial rights in a nation still considered essentially Catholic.

- Huguenots: Members of the Protestant Reformed Church of France during the 16th and 17th centuries; inspired by the writings of John Calvin.

- Real Presence: A term used in various Christian traditions to express belief that in the Eucharist, Jesus Christ is really present in what was previously just bread and wine, and not merely present in symbol.

Overview

The French Wars of Religion (1562–1598) is the name of a period of civil infighting and military operations primarily between French Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots). The conflict involved the factional disputes between the aristocratic houses of France, such as the House of Bourbon and the House of Guise, and both sides received assistance from foreign sources.

The exact number of wars and their respective dates are the subject of continued debate by historians; some assert that the Edict of Nantes in 1598 concluded the wars, although a resurgence of rebellious activity following this leads some to believe the Peace of Alais in 1629 is the actual conclusion. However, the Massacre of Vassy in 1562 is agreed to have begun the Wars of Religion; up to a hundred Huguenots were killed in this massacre. During the wars, complex diplomatic negotiations and agreements of peace were followed by renewed conflict and power struggles.

Between 2,000,000 and 4,000,000 people were killed as a result of war, famine, and disease, and at the conclusion of the conflict in 1598, Huguenots were granted substantial rights and freedoms by the Edict of Nantes, though it did not end hostility towards them. The wars weakened the authority of the monarchy, already fragile under the rule of Francis II and then Charles IX, though the monarchy later reaffirmed its role under Henry IV.

Introduction of Protestantism

Protestant ideas were first introduced to France during the reign of Francis I (1515–1547) in the form of Lutheranism, the teachings of Martin Luther, and circulated unimpeded for more than a year around Paris. Although Francis firmly opposed heresy, the difficulty was initially in recognizing what constituted it; Catholic doctrine and definition of orthodox belief was unclear. Francis I tried to steer a middle course in the developing religious schism in France.

Calvinism, a form of Protestant religion, was introduced by John Calvin, who was born in Noyon, Picardy, in 1509, and fled France in 1536 after the Affair of the Placards. Calvinism in particular appears to have developed with large support from the nobility. It is believed to have started with Louis Bourbon, Prince of Condé, who, while returning home to France from a military campaign, passed through Geneva, Switzerland, and heard a sermon by a Calvinist preacher. Later, Louis Bourbon would become a major figure among the Huguenots of France. In 1560, Jeanne d’Albret, Queen regnant of Navarre, converted to Calvinism possibly due to the influence of Theodore de Beze. She later married Antoine de Bourbon, and their son Henry of Navarre would be a leader among the Huguenots.

Affair of the Placards

Francis I continued his policy of seeking a middle course in the religious rift in France until an incident called the Affair of the Placards. The Affair of the Placards began in 1534 when Protestants started putting up anti-Catholic posters. The posters were extreme in their anti-Catholic content—specifically, the absolute rejection of the Catholic doctrine of “Real Presence.” Protestantism became identified as “a religion of rebels,” helping the Catholic Church to more easily define Protestantism as heresy. In the wake of the posters, the French monarchy took a harder stand against the protesters. Francis I had been severely criticized for his initial tolerance towards Protestants, and now was encouraged to repress them.

Tensions Mount

King Francis I died on March 31, 1547, and was succeeded to the throne by his son Henry II. Henry II continued the harsh religious policy that his father had followed during the last years of his reign. In 1551, Henry issued the Edict of Châteaubriant, which sharply curtailed Protestant rights to worship, assemble, or even discuss religion at work, in the fields, or over a meal.

An organized influx of Calvinist preachers from Geneva and elsewhere during the 1550s succeeded in setting up hundreds of underground Calvinist congregations in France. This underground Calvinist preaching (which was also seen in the Netherlands and Scotland) allowed for the formation of covert alliances with members of the nobility and quickly led to more direct action to gain political and religious control.

As the Huguenots gained influence and displayed their faith more openly, Roman Catholic hostility to them grew, even though the French crown offered increasingly liberal political concessions and edicts of toleration. However, these measures disguised the growing tensions between Protestants and Catholics.

The Eight Wars of Religion

These tensions spurred eight civil wars, interrupted by periods of relative calm, between 1562 and 1598. With each break in peace, the Huguenots’ trust in the Catholic throne diminished, and the violence became more severe and Protestant demands became grander, until a lasting cessation of open hostility finally occurred in 1598.

The wars gradually took on a dynastic character, developing into an extended feud between the Houses of Bourbon and Guise, both of which—in addition to holding rival religious views—staked a claim to the French throne. The crown, occupied by the House of Valois, generally supported the Catholic side, but on occasion switched over to the Protestant cause when it was politically expedient.

St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre

One of the most infamous events of the Wars of Religion was the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, when Catholics killed thousands of Huguenots in Paris. The massacre began on the night of August 23, 1572 (the eve of the feast of Bartholomew the Apostle), two days after the attempted assassination of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, the military and political leader of the Huguenots. The king ordered the killing of a group of Huguenot leaders, including Coligny, and the slaughter spread throughout Paris and beyond. The exact number of fatalities throughout the country is not known, but estimates are that between about 2,000 and 3,000 Protestants were killed in Paris, and between 3,000 and 7,000 more in the French provinces. Similar massacres took place in other towns in the weeks following. By September 17, almost 25,000 Protestants had been massacred in Paris alone. Outside of Paris, the killings continued until October 3. An amnesty granted in 1573 pardoned the perpetrators.

The massacre also marked a turning point in the French Wars of Religion. The Huguenot political movement was crippled by the loss of many of its prominent aristocratic leaders, as well as many re-conversions by the rank and file, and those who remained were increasingly radicalized.

War of the Three Henrys

The War of the Three Henrys (1587–1589) was the eighth and final conflict in the series of civil wars in France known as the Wars of Religion. It was a three-way war fought between:

- King Henry III of France, supported by the royalists and the politiques;

- King Henry of Navarre, leader of the Huguenots and heir-presumptive to the French throne, supported by Elizabeth I of England and the Protestant princes of Germany; and

- Henry of Lorraine, Duke of Guise, leader of the Catholic League, funded and supported by Philip II of Spain.

The war began when the Catholic League convinced King Henry III to issue an edict outlawing Protestantism and annulling Henry of Navarre’s right to the throne. For the first part of the war, the royalists and the Catholic League were uneasy allies against their common enemy, the Huguenots. Henry of Navarre sought foreign aid from the German princes and Elizabeth I of England.

Henry III successfully prevented the junction of the German and Swiss armies. The Swiss were his allies, and had come to invade France to free him from subjection, but Henry III insisted that their invasion was not in his favor, but against him, forcing them to return home.

In Paris, the glory of repelling the German and Swiss Protestants all fell to the Duke of Guise. The king’s actions were viewed with contempt. People thought that the king had invited the Swiss to invade, paid them for coming, and sent them back again. The king, who had really performed the decisive part in the campaign, and expected to be honored for it, was astounded that public voice should thus declare against him. The Catholic League had put its preachers to good use.

Open war erupted between the royalists and the Catholic League. Charles, Duke of Mayenne, Guise’s younger brother, took over the leadership of the league. At the moment it seemed that he could not possibly resist his enemies. His power was effectively limited to Blois, Tours, and the surrounding districts. In these dark times the King of France finally reached out to his cousin and heir, the King of Navarre. Henry III declared that he would no longer allow Protestants to be called heretics, while the Protestants revived the strict principles of royalty and divine right. As on the other side ultra-Catholic and anti-royalist doctrines were closely associated, so on the side of the two kings the principles of tolerance and royalism were united.

In July 1589, in the royal camp at Saint-Cloud, a Dominican monk named Jacques Clément gained an audience with the King and drove a long knife into his spleen. Clément was killed on the spot, taking with him the information of who, if anyone, had hired him. On his deathbed, Henri III called for Henry of Navarre, and begged him, in the name of statecraft, to become a Catholic, citing the brutal warfare that would ensue if he refused. He named Henry Navarre as his heir, who became Henry IV.

Edict of Nantes

Fighting continued between Henry IV and the Catholic League for almost a decade. The warfare was finally quelled in 1598 when Henry IV recanted Protestantism in favor of Roman Catholicism, issued as the Edict of Nantes. The edict established Catholicism as the state religion of France, but granted the Protestants equality with Catholics under the throne and a degree of religious and political freedom within their domains. The edict simultaneously protected Catholic interests by discouraging the founding of new Protestant churches in Catholic-controlled regions. With the proclamation of the Edict of Nantes, and the subsequent protection of Huguenot rights, pressures to leave France abated.

In offering general freedom of conscience to individuals, the edict gave many specific concessions to the Protestants, such as amnesty and the reinstatement of their civil rights, including the right to work in any field or for the state and to bring grievances directly to the king. This marked the end of the religious wars that had afflicted France during the second half of the 16th century.

The Witch Trials

Between the 15th and 18th centuries in Europe, many people were accused of and put on trial for practicing witchcraft.

Learning Objectives

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In early modern Europe, there was widespread hysteria that malevolent Satanic witches were operating as an organized threat to Christianity. Those who were accused of witchcraft were portrayed as being Devil worshipers.

- In medieval Europe, the Black Death was a turning point in peoples’ views of witches. The death of a large percentage of the European population was believed by many Christians to have been caused by their enemies.

- The peak of the witch hunt was during the European wars of religion, peaking between about 1580 and 1630.

- Over the entire duration of the trials, which spanned three centuries, an estimated total of 40,000–100,000 people were executed.

- The Witch Trials of Trier in Germany was perhaps the biggest witch trial in European history. It led to the death of about 386 people, and was perhaps the biggest mass execution in Europe during peacetime.

- While the witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid-17th century, they became more prominent in the American colonies.

- An estimated 75% to 85% of those accused in the early modern witch trials were women, and there is certainly evidence of misogyny on the part of those persecuting witches.

Key Terms

- Johannes Kepler: A German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution.

The witch trials in the early modern period were a series of witch hunts between the 15th and 18th centuries, when across early modern Europe, and to some extent in the European colonies in North America, there was a widespread hysteria that malevolent Satanic witches were operating as an organized threat to Christendom. Those accused of witchcraft were portrayed as being worshippers of the Devil, who engaged in sorcery at meetings known as Witches’ Sabbaths. Many people were subsequently accused of being witches and were put on trial for the crime, with varying punishments being applicable in different regions and at different times.

In early modern European tradition, witches were stereotypically, though not exclusively, women. European pagan belief in witchcraft was associated with the goddess Diana and dismissed as “diabolical fantasies” by medieval Christian authors.

Background to the Witch Trials

During the medieval period, there was widespread belief in magic across Christian Europe. The medieval Roman Catholic Church, which then dominated a large swath of the continent, divided magic into two forms—natural magic, which was acceptable because it was viewed as merely taking note of the powers in nature that were created by God, and demonic magic, which was frowned upon and associated with demonology.

It was also during the medieval period that the concept of Satan, the Biblical Devil, began to develop into a more threatening form. Around the year 1000, when there were increasing fears that the end of the world would soon come in Christendom, the idea of the Devil had become prominent.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the concept of the witch in Christendom underwent a relatively radical change. No longer were witches viewed as sorcerers who had been deceived by the Devil into practicing magic that went against the powers of God. Instead they became all-out malevolent Devil-worshippers, who had made pacts with him in which they had to renounce Christianity and devote themselves to Satanism. As a part of this, it was believed that they gained new, supernatural powers that enabled them to work magic, which they would use against Christians.

While the witch trials only really began in the 15th century, with the start of the early modern period, many of their causes had been developing during the previous centuries, with the persecution of heresy by the medieval Inquisition during the late 12th and the 13th centuries, and during the late medieval period, during which the idea of witchcraft or sorcery gradually changed and adapted. An important turning point was the Black Death of 1348–1350, which killed a large percentage of the European population, and which many Christians believed had been caused by evil forces.

Beginnings of the Witch Trials

While the idea of witchcraft began to mingle with the persecution of heretics even in the 14th century, the beginning of the witch hunts as a phenomenon in its own right became apparent during the first half of the 15th century in southeastern France and western Switzerland, in communities of the Western Alps, in what was at the time Burgundy and Savoy.

Here, the cause of eliminating the supposed Satanic witches from society was taken up by a number of individuals; Claude Tholosan for instance had tried over two hundred people, accusing them of witchcraft in Briançon, Dauphiné, by 1420.

While early trials fall still within the late medieval period, the peak of the witch hunt was during the period of the European wars of religion, between about 1580 and 1630. Over the entire duration of the phenomenon of some three centuries, an estimated total of 40,000 to 100,000 people were executed.

The Trials of 1580–1630

The height of the European witch trials was between 1560 and 1630, with the large hunts first beginning in 1609. During this period, the biggest witch trials were held in Europe, notably the Trier witch trials (1581–1593), the Fulda witch trials (1603–1606), the Basque witch trials (1609–1611), the Würzburg witch trial (1626–1631), and the Bamberg witch trials (1626–1631).

The Witch Trials of Trier in Germany was perhaps the biggest witch trial in European history. The persecutions started in the diocese of Trier in 1581 and reached the city itself in 1587, where they were to lead to the deaths of about 368 people, and as such it was perhaps the biggest mass execution in Europe during peacetime.

In Denmark, the burning of witches increased following the reformation of 1536. Christian IV of Denmark, in particular, encouraged this practice, and hundreds of people were convicted of witchcraft and burned. In England, the Witchcraft Act of 1542 regulated the penalties for witchcraft. In the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, over seventy people were accused of witchcraft on account of bad weather when James VI of Scotland, who shared the Danish king’s interest in witch trials, sailed to Denmark in 1590 to meet his betrothed, Anne of Denmark.

The sentence for an individual found guilty of witchcraft or sorcery during this time, and in previous centuries, typically included either burning at the stake or being tested with the “ordeal of cold water” or judicium aquae frigidae. Accused persons who drowned were considered innocent, and ecclesiastical authorities would proclaim them “brought back,” but those who floated were considered guilty of practicing witchcraft, and burned at the stake or executed in an unholy fashion.

Decline of the Trials

While the witch trials had begun to fade out across much of Europe by the mid-17th century, they continued to a greater extent on the fringes of Europe and in the American colonies. The clergy and intellectuals began to speak out against the trials from the late 16th century. Johannes Kepler in 1615 could only by the weight of his prestige keep his mother from being burned as a witch. The 1692 Salem witch trials were a brief outburst of witch hysteria in the New World at a time when the practice was already waning in Europe.

Witch Trials and Women

An estimated 75% to 85% of those accused in the early modern witch trials were women, and there is certainly evidence of misogyny on the part of those persecuting witches, evident from quotes such as “[It is] not unreasonable that this scum of humanity, [witches], should be drawn chiefly from the feminine sex” (Nicholas Rémy, c. 1595) or “The Devil uses them so, because he knows that women love carnal pleasures, and he means to bind them to his allegiance by such agreeable provocations.” In early modern Europe, it was widely believed that women were less intelligent than men and more susceptible to sin.

Nevertheless, it has been argued that the supposedly misogynistic agenda of works on witchcraft has been greatly exaggerated, based on the selective repetition of a few relevant passages of the Malleus Maleficarum. Many modern scholars argue that the witch hunts cannot be explained simplistically as an expression of male misogyny, as indeed women were frequently accused by other women, to the point that witch hunts, at least at the local level of villages, have been described as having been driven primarily by “women’s quarrels.” Especially at the margins of Europe, in Iceland, Finland, Estonia, and Russia, the majority of those accused were male.

Barstow (1994) claimed that a combination of factors, including the greater value placed on men as workers in the increasingly wage-oriented economy, and a greater fear of women as inherently evil, loaded the scales against women, even when the charges against them were identical to those against men. Thurston (2001) saw this as a part of the general misogyny of the late medieval and early modern periods, which had increased during what he described as “the persecuting culture” from what it had been in the early medieval period. Gunnar Heinsohn and Otto Steiger in a 1982 publication speculated that witch hunts targeted women skilled in midwifery specifically in an attempt to extinguish knowledge about birth control and “repopulate Europe” after the population catastrophe of the Black Death.

The Terror of History: The Witch Hunt in Early Modern Europe, UCLA: Professor Ruiz, UCLA department chair and Premio del Rey prize for best book in Spanish history before 1580 for his Crisis and Continuity: Land and Town in Late Medieval Castile, was speaker for the UCLA History Alumni Faculty Lecture, cohosted by the UCLA Alumni Association and UCLA Department of History. Ruiz spoke to an audience of more than eighty history department alumni and guests. Watch his lively and engaging presentation.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike