42 West African Empires

The Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire was located in what is now southeastern Mauritania, western Mali, and eastern Senegal, and derived its power from the control of trans-Saharan trade, particularly gold trade.

Learning Objectives

Describe the Ghana Empire and the source of its wealth

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Ghana Empire, called the Wagadou (or Wagadu) Empire by its rulers, was located in what is now southeastern Mauritania, western Mali, and eastern Senegal. There is no consensus on when precisely it originated. Different traditions identify its beginnings between as early as 100 CE and the 9th century, with most scholars accepting the 8th or 9th century.

- Ghana’s economic development and eventual wealth was linked to the growth of regular and intensified trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and ivory, which allowed for the development of larger urban centers and encouraged territorial expansion to gain control over different trade routes.

- The empire’s capital is believed to have been at Koumbi Saleh on the rim of the Sahara desert. According to the description of the town left by Al-Bakri in 1067/1068, the capital was actually two cities, but “between these two towns are continuous habitations,” so they might have merged into one.

- The Ghana Empire lay in the Sahel region to the north of the West African gold fields, and was able to profit by controlling the trans-Saharan gold trade, which turned Ghana into an empire of legendary wealth.

- Ghana appears to have had a central core region and was surrounded by vassal states. One of the earliest sources notes that “under the king’s authority are a number of kings.” These “kings” were presumably the rulers of the territorial units often called kafu in Mandinka.

- Although scholars debate how and when Ghana declined and collapsed, it is clear that it was incorporated into the Mali Empire around 1240.

Key Terms

- the Almoravids: A Berber imperial dynasty of Morocco that formed an empire in the 11th century that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus. Founded by Abdallah ibn Yasin, their capital was Marrakesh, a city they founded in 1062. The dynasty originated among the Lamtuna and the Gudala, nomadic Berber tribes of the Sahara, traversing the territory between the Draa, the Niger, and the Senegal rivers.

- the Soninke people: A Mandé people who descend from the Bafour and are closely related to the Imraguen of Mauritania. They were the founders of the ancient empire of Ghana c. 750–1240 CE. Subgroups include the Maraka and Wangara.

- Koumbi Saleh: The site of a ruined medieval town in southeast Mauritania that may have been the capital of the Ghana Empire.

Disputed Origins of the Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire, called the Wagadou (or Wagadu) Empire by its rulers, was located in what is now southeastern Mauritania, western Mali, and eastern Senegal. There is no consensus on when precisely it originated, but its development is linked to the changes in trade that emerged throughout the centuries after the introduction of the camel to the western Sahara (3rd century). By the time of the Muslim conquest of North Africa in the 7th century, the camel had changed the earlier, more irregular trade routes into a trade network running from Morocco to the Niger River. This regular and intensified trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and ivory allowed for the development of larger urban centers and encouraged territorial expansion to gain control over different trade routes.

The Ghana ruling dynasty was first mentioned in written records in 830, and thus the 9th century is sometimes identified as the empire’s beginning.

In the medieval Arabic sources the word “Ghana” can refer to a royal title, the name of a capital city, or a kingdom. The earliest reference to Ghana as a town is by al-Khuwarizmi, who died around 846. Research on the site of Koumbi Saleh (or Kumbi Saleh), a ruined medieval town in southeast Mauritania that may have been the capital of the Ghana Empire, suggests earlier beginnings. The earliest author to mention Ghana is the Persian astronomer Ibrahim al-Fazari, who, writing at the end of the eighth century, refers to “the territory of Ghana, the land of gold.” From the 9th century, Arab authors mention the Ghana Empire in connection with the trans-Saharan gold trade. Al-Bakri, who wrote in the 11th century, described the capital of Ghana as consisting of two towns six miles apart, one inhabited by Muslim merchants and the other by the king of Ghana. According to the tradition of the Soninke people, they migrated to southeastern Mauritania in the 1st century, and as early as around 100 CE created a settlement that would eventually develop into the Ghana Empire. Other sources identify the beginnings of the empire some time between the 4th century and the mid-8th century.

When the Gold Coast in 1957 became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to regain its independence from colonial rule, it was renamed in honor of the long-gone empire from which the ancestors to the Akan people of modern-day Ghana are thought to have migrated.

The Capital City: Koumbi Saleh

The empire’s capital is believed to have been at Koumbi Saleh on the rim of the Sahara desert. According to the description of the town left by Al-Bakri in 1067/1068, the capital was actually two cities, but “between these two towns are continuous habitations,” so they might have merged into one. According to al-Bakri, the major part of the city was called El-Ghaba, and was the residence of the king. It was protected by a stone wall and functioned as the royal and spiritual capital of the empire. It contained a sacred grove of trees used for Soninke religious rites in which priests lived. It also contained the king’s palace, the grandest structure in the city. There was also one mosque for visiting Muslim officials. The name of the other section of the city is not recorded. It was surrounded by wells with fresh water, where vegetables were grown. It had twelve mosques, one of which was designated for Friday prayers, and had a full group of scholars, scribes, and Islamic jurists. Because the majority of these Muslims were merchants, this part of the city was probably its primary business district.

Economy and Government

Most of our information about the economy of Ghana comes from al-Bakri. He noted that merchants had to pay a one gold dinar tax on imports of salt and two on exports of salt. Al-Bakri mentioned also copper and “other goods.” Imports probably included products such as textiles and ornaments. Many of the hand-crafted leather goods found in old Morocco also had their origins in the Ghana Empire. Tribute was also received from various tributary states and chiefdoms at the empire’s periphery. The Ghana Empire lay in the Sahel region to the north of the West African gold fields, and was able to profit from controlling the trans-Saharan gold trade. The early history of Ghana is unknown, but there is evidence that North Africa had begun importing gold from West Africa before the Arab conquest in the middle of the 7th century.

Much testimony on ancient Ghana comes from the recorded visits of foreign travelers, who, by definition, could provide only a fragmentary picture. Islamic writers often commented on the social-political stability of the Empire based on the seemingly just actions and grandeur of the king. Al-Bakri questioned merchants who visited the empire in the 11th century and wrote of the king hearing grievances against officials and being surrounded by great wealth. Ghana appears to have had a central core region and was surrounded by vassal states. One of the earliest sources, al-Ya’qubi, writing in 889/890 (276 AH), noted that “under the king’s authority are a number of kings.” These “kings” were presumably the rulers of the territorial units often called kafu in Mandinka. In al-Bakri’s time, the rulers of Ghana had begun to incorporate more Muslims into government, including the treasurer, his interpreter, and “the majority of his officials.”

Decline

Given scarce Arabic sources and the ambiguity of the existing archaeological record, it is difficult to determine when and how Ghana declined and fell. According to Arab tradition, Ghana fell when it was sacked by the Almoravid movement in 1076–1077, but this interpretation has been questioned. Conrad and Fisher (1982) argued that the notion of any Almoravid military conquest is merely perpetuated folklore, derived from a misinterpretation of or limited reliance on Arabic sources. Dierke Lange agreed with the original military incursion theory but argued that this does not preclude Almoravid political agitation, claiming that Ghana’s demise owed much to the latter. Sheryl L. Burkhalter

argued that while the idea of the conquest was unclear, the influence and success of the Almoravid movement in securing West African gold and circulating it widely necessitated a high degree of political control. Furthermore, the archaeology of ancient Ghana does not show signs of the rapid change and destruction that would be associated with any Almoravid-era military conquests.

It is assumed that the ensuing war pushed Ghana over the edge, ending the kingdom’s position as a commercial and military power by 1100. It collapsed into tribal groups and chieftaincies, some of which later assimilated into the Almoravids, while others founded the Mali Empire. Despite ambiguous evidence, it is clear that Ghana was incorporated into the Mali Empire around 1240.

Mali

The Mali Empire was an empire in West Africa that lasted from 1230 to 1600 and profoundly influenced the culture of the region through the spread of its language, laws, and customs along lands adjacent to the Niger River, as well as other areas consisting of numerous vassal kingdoms and provinces.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate each period in the history of the Mali Empire

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Mali Empire, also historically referred to as the Manden Kurufaba, was an empire in West Africa that lasted from c. 1230 to 1600. It was the largest empire in West Africa and profoundly influenced the culture of the region through the spread of its language, laws, and customs along lands adjacent to the Niger River, as well as other areas consisting of numerous vassal kingdoms and provinces.

- Modern oral traditions recorded that the Mandinka kingdoms of Mali or Manden had already existed several centuries before unification. This area was composed of mountains, savanna, and forest providing ideal protection and resources for the population of hunters. Those not living in the mountains formed small city-states.

- The combined forces of northern and southern Manden defeated the Sosso army at the Battle of Kirina in approximately 1235. This victory resulted in the fall of the Kaniaga kingdom and the rise of the Mali Empire.

- The Mali Empire covered a larger area for a longer period of time than any other West African state before or since. What made this possible was the decentralized nature of administration throughout the state. Its power came, above all, from trade.

- The Mali Empire reached its largest size and flourished as a trade and intellectual center under the Laye Keita mansas (1312–1389). The

empire’s total area included nearly all the land between the Sahara Desert and the coastal forests. - The 1599 battle of Djenné marked the effective end of the great Mali Empire and set the stage for a plethora of smaller West African states to emerge.

Key Terms

- mansa: A Mandinka word meaning “sultan” (king) or “emperor.” It is particularly associated with the Keita dynasty of the Mali Empire, which dominated West Africa from the 13th century to the 15th century.

- muezzin: The person appointed at a mosque to lead and recite the call to prayer for every event of prayer and worship. The muezzin’s post is an important one, and the community depends on him for an accurate prayer schedule.

Introduction

The Mali Empire, also historically referred to as the Manden Kurufaba, was an empire in West Africa that lasted from c. 1230 to 1600. The empire was founded by Sundiata Keita and became renowned for the wealth of its rulers. It was the largest empire in West Africa and profoundly influenced the culture of the region through the spread of its language, laws, and customs along lands adjacent to the Niger River, as well as other areas consisting of numerous vassal kingdoms and provinces.

Pre-Imperial Mali

Modern oral traditions recorded that the Mandinka kingdoms of Mali or Manden had already existed several centuries before unification by Sundiata, a Malian mansa also known as Mari Djata I, as a small state just to the south of the Soninké empire of Wagadou (the Ghana Empire). This area was composed of mountains, savanna, and forest providing ideal protection and resources for the population of hunters. Those not living in the mountains formed small city-states such as Toron, Ka-Ba, and Niani.

In approximately 1140, the Sosso kingdom of Kaniaga, a former vassal of Wagadou, began conquering the lands of its old masters. By 1180, it had even subjugated Wagadou, forcing the Soninké to pay tribute. In 1203, the Sosso king Soumaoro of the Kanté clan came to power and reportedly terrorized much of Manden, stealing women and goods from both Dodougou and Kri.

After many years in exile, first at the court of Wagadou and then at Mema, Sundiata,

a prince who eventually became founder of the Mali Empire, was sought out by a Niani delegation and begged to combat the Sosso and free the kingdoms of Manden. Returning with the combined armies of Mema, Wagadou, and all the rebellious Mandinka city-states, Maghan Sundiata, or Sumanguru, led a revolt against the Kaniaga Kingdom around 1234. The combined forces of northern and southern Manden defeated the Sosso army at the Battle of Kirina (then known as Krina) in approximately 1235. This victory resulted in the fall of the Kaniaga kingdom and the rise of the Mali Empire. After the victory, King Soumaoro disappeared and the Mandinka stormed the last of the Sosso cities. Maghan Sundiata was declared “faama of faamas” and received the title “mansa,” which translates roughly to emperor. At the age of eighteen, he gained authority over all the twelve kingdoms in an alliance known as the Manden Kurufaba. He was crowned under the throne name Sunidata Keita, becoming the first Mandinka emperor. And so the name Keita became a clan/family and began its reign.

Imperial Mali (1250–1559)

The Mali Empire covered a larger area for a longer period of time than any other West African state before or since. What made this possible was the decentralized nature of administration throughout the state; yet the mansa managed to keep tax money and nominal control over the area without agitating his subjects into revolt. Officials at the village, town, city, and county levels were elected locally, and only at the state or provincial level was there any palpable interference from the central authority in Niani. Provinces picked their own governors via their own custom (election, inheritance, etc.), but governors had to be approved by the mansa and were subject to his oversight.

The Mali Empire flourished because of trade above all else. It contained three immense gold mines within its borders, and the empire taxed every ounce of gold or salt that entered its borders. By the beginning of the 14th century, Mali was the source of almost half the Old World’s gold, exported from mines in Bambuk, Boure, and Galam. There was no standard currency throughout the realm, but several forms were prominent by region. The Sahelian and Saharan towns of the Mali Empire were organized as both staging posts in the long-distance caravan trade and trading centers for the various West African products (e.g., salt, copper). Ibn Battuta,

a Medieval Moroccan Muslim traveler and scholar, observed the employment of slave labor. During most of his journey, Ibn Battuta traveled with a retinue that included slaves, most of whom carried goods for trade but would also be traded themselves. On the return from Takedda to Morocco, his caravan transported 600 female slaves, which suggests that slavery was a substantial part of the commercial activity of the empire.

The number and frequency of conquests in the late 13th century and throughout the 14th century indicate that the Kolonkan mansas (who ruled at the time) inherited and/or developed a capable military. However, it went through radical changes before reaching the legendary proportions proclaimed by its subjects. Thanks to steady tax revenue and a stable government beginning in the last quarter of the 13th century, the Mali Empire was able to project its power throughout its own extensive domain and beyond. The empire maintained a semi-professional full-time army in order to defend its borders. The entire nation was mobilized, with each clan obligated to provide a quota of fighting-age men. Historians who lived during the height and decline of the Mali Empire consistently recorded its army at 100,000, with 10,000 of that number being made up of cavalry.

The Mali Empire reached its largest size under the Laye Keita mansas (1312–1389). The empire’s total area included nearly all the land between the Sahara Desert and the coastal forests. It spanned modern-day Senegal, southern Mauritania, Mali, northern Burkina Faso, western Niger, the Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, and northern Ghana.

The first ruler from the Laye lineage was Kankan Musa Keita (or Moussa), also known as Mansa Musa. He embarked on a large building program, raising mosques and madrasas in Timbuktu and Gao.

He also transformed Sankore from an informal madrasah into an Islamic university.

By the end of Mansa Musa’s reign, the Sankoré University had been converted into a fully staffed university, with the largest collections of books in Africa since the Library of Alexandria. During this period, there was an advanced level of urban living in the major centers of the Mali. Sergio Domian, an Italian art and architecture scholar, wrote the following about this period: “Thus was laid the foundation of an urban civilization. At the height of its power, Mali had at least 400 cities, and the interior of the Niger Delta was very densely populated.”

Collapse

Mansa Mahmud Keita IV was the last emperor of Manden, according to the Tarikh al-Sudan. He launched an attack on the city of Djenné in 1599 with Fulani allies, hoping to take advantage of Songhai’s defeat. Eventually, the army inside Djenné intervened, forcing Mansa Mahmud Keita IV and his army to retreat to Kangaba. The battle marked the effective end of the great Mali Empire and set the stage for a plethora of smaller West African states to emerge. Around 1610, Mahmud Keita IV died. Oral tradition states that he had three sons who fought over Manden’s remains. No single Keita ever ruled Manden after Mahmud Keita IV’s death, thus the end of the Mali Empire.

The old core of the empire was divided into three spheres of influence. Kangaba, the de facto capital of Manden since the time of the last emperor, became the capital of the northern sphere. The Joma area, governed from Siguiri, controlled the central region, which encompassed Niani. Hamana (or Amana), southwest of Joma, became the southern sphere, with its capital at Kouroussa in modern Guinea. Each ruler used the title of mansa, but their authority only extended as far as their own sphere of influence. Despite this disunity in the realm, the realm remained under Mandinka control into the mid-17th century. The three states warred on each other as much if not more than they did against outsiders, but rivalries generally stopped when faced with invasion. This trend would continue into colonial times against Tukulor enemies from the west.

Songhai

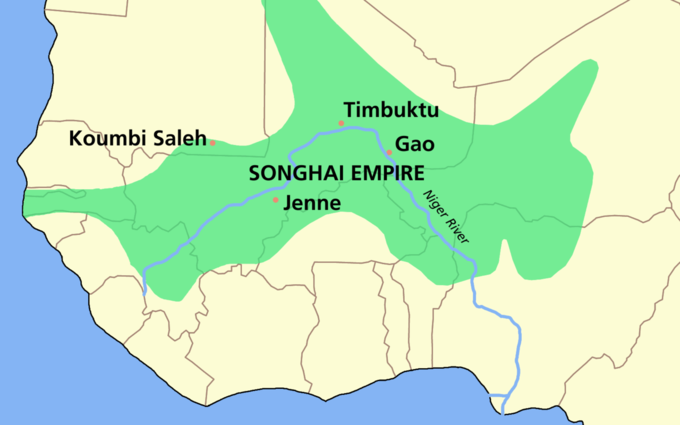

The Songhai Empire dominated the western Sahel in the 15th and 16th centuries; at its peak, it was one of the largest states in Africa.

Learning Objectives

Explain the importance of Timbuktu after locating the Songhai Empire

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The Songhai Empire was a state that dominated the western Sahel in the 15th and 16th centuries. At its peak, it was one of the largest states in African history. Initially, the empire was ruled by the Sonni dynasty (c. 1464–1493), but it was later replaced by the Askiya dynasty (1493–1591).

- In the second half of the 14th century, disputes over succession weakened the Mali Empire and in the 1430s Songhai, previously a Mali dependency, gained independence under the Sonni Dynasty.

- Sonni Ali reigned from 1464 to 1492. In the late 1460s, he conquered many of the Songhai’s neighboring states, including what remained of the Mali Empire. He was arguably the empire’s most formidable military strategist and conqueror. Under his rule, Songhai reached a size of over 1,400,000 square kilometers.

- The internal political chaos and multiple civil wars within the empire allowed Morocco to invade Songhai. The main reason for the Moroccan invasion was to seize control of and revive the trans-Saharan trade in salt and gold. The empire fell to the Moroccans and their firearms in 1591.

- The empire’s power was linked to economic trade; their government system granted authority to local chiefs as long as they did not undermine Songhai policy and tightly controlled labor division system.

Key Terms

- Gao: A city in Mali located on the River Niger that for much of its history was an important commercial center involved in the trans-Saharan trade. Towards the end of the 13th century, it became part of the Mali Empire, but in the first half of the 15th century the town regained its independence and with the conquests of Sonni Ali (ruled 1464–1492) it became the capital of the Songhai Empire.

- Sonni dynasty: A dynasty of rulers of the Songhai Empire of medieval West Africa. The first ruler of the dynasty, Sunni Ali Kulun, probably reigned at the end of the fourteenth century. The last ruler, Sonni Baru, ruled until 1493 when the throne was usurped by the Askiya Muhammad I (known also as Askia the Great), the founder of the Askiya Dynasty.

- Sahel: The ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition in Africa between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian Savanna to the south. Having a semi-arid climate, it stretches across the south-central latitudes of Northern Africa between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea.

- Timbuktu: A historical and still-inhabited city in the West African nation of Mali, situated 20 km (12 mi) north of the River Niger on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. In its Golden Age, the town’s numerous Islamic scholars and extensive trading network enabled an important book trade. Together with the campuses of the Sankore Madrasah, an Islamic university, this established the city as a scholarly center in Africa.

Introduction

The Songhai Empire (also transliterated as Songhay) was a state that dominated the western Sahel in the 15th and 16th centuries. At its peak, it was one of the largest states in African history. The state is known by its historiographical name, derived from its leading ethnic group and ruling elite, the Songhai. Sonni Ali established Gao as the capital of the empire, although a Songhai state had existed in and around Gao since the 11th century. Other important cities in the empire were Timbuktu and Djenné, conquered in 1468 and 1475 respectively, where urban-centered trade flourished. Initially, the empire was ruled by the Sonni dynasty (c. 1464–1493), but it was later replaced by the Askiya dynasty (1493–1591).

During the second half of the 13th century, Gao and the surrounding region had grown into an important trading center and attracted the interest of the expanding Mali Empire. Mali conquered Gao towards the end of the 13th century and the town would remain under Malian hegemony until the late 14th century. But as the Mali Empire started to disintegrate, the Songhai reasserted control of Gao. Songhai rulers subsequently took advantage of the weakened Mali Empire to expand Songhai rule.

Imperial Songhai

In the second half of the 14th century, disputes over succession weakened the Mali Empire and in the 1430s, Songhai, previously a Mali dependency, gained independence under the Sonni Dynasty. Around thirty years later, Sonni Sulayman Dama attacked Mema, the Mali province west of Timbuktu, paving the way for his successor, Sonni Ali, to turn his country into one of the greatest empires sub-Saharan Africa has ever seen.

Sonni Ali reigned from 1464 to 1492. Like Songhai kings before him, he was a Muslim. In the late 1460s, he conquered many of the Songhai’s neighboring states, including what remained of the Mali Empire. He was arguably the empire’s most formidable military strategist and conqueror. Under his rule, Songhai reached a size of over 1,400,000 square kilometers. During his campaigns for expansion, Ali conquered many lands, repelling attacks from the Mossi to the south and overcoming the Dogon people to the north. He annexed Timbuktu in 1468, after Islamic leaders of the town requested his assistance in overthrowing marauding Tuaregs (Berber people with a traditionally nomadic pastoralist lifestyle) who had taken the city following the decline of Mali. However, Ali met stark resistance after setting his sights on the wealthy and renowned trading town of Djenné (also known as Jenne). After a persistent seven-year siege, he was able to forcefully incorporate it into his vast empire in 1473, but only after having starved its citizens into surrender

Oral traditions present a conflicted image of Sonni Ali. On the one hand, the invasion of Timbuktu destroyed the city; Ali was described as an intolerant tyrant who conducted a repressive policy against the scholars of Timbuktu, especially those of the Sankore region who were associated with the Tuareg. On the other hand, his control of critical trade routes and cities brought great wealth. He is thus often presented as a powerful politician and great military commander and under his reign, Djenné and Timbuktu became great centers of learning.

Following Ali’s reign, Askia the Great strengthened the Songhai Empire and made it the largest empire in West Africa’s history. At its peak under his reign, the Songhai Empire encompassed the Hausa states as far as Kano (in present-day Nigeria) and much of the territory that had belonged to the Songhai empire in the west. His policies resulted in a rapid expansion of trade with Europe and Asia, the creation of many schools, and the establishment of Islam as an integral part of the empire. Askia opened religious schools, constructed mosques, and opened up his court to scholars and poets from throughout the Muslim world, but he was also tolerant of other religions and did not force Islam on his people. Among his great accomplishments was an interest in astronomical knowledge, which led to the development of astronomy and observatories in the capital.

Not only was he a patron of Islam but he was also gifted in administration and encouraging trade. He centralized the administration of the empire and established an efficient bureaucracy that was responsible for, among other things, tax collection and the administration of justice. He also demanded that canals be built in order to enhance agriculture, which would eventually increase trade. More importantly than anything he did for trade was the introduction of weights and measures and the appointment of an inspector for each of Songhai’s important trading centers. During his reign Islam became more widely entrenched, trans-Saharan trade flourished, and the Saharan salt mines of Taghaza were brought within the boundaries of the empire.

However, as Askia the Great grew older, his power declined. In 1528, his sons revolted against him and declared Musa, one of Askia’s many sons, as king. Following Musa’s overthrow in 1531, Songhai’s empire went into decline. Multiple attempts at governing the empire by Askia’s sons and grandsons failed and between the political chaos and multiple civil wars within the empire, Morocco invaded Songhai. The main reason for the Moroccan invasion of Songhai was to seize control and revive the trans-Saharan trade in salt and gold. The Songhai military, during Askia’s reign, consisted of full-time soliders, but the king never modernized his army. The Empire fell to the Moroccans and their firearms in 1591.

The Organization of Songhai

At its peak, the Songhai city of Timbuktu became a thriving cultural and commercial center where Arab, Italian, and Jewish merchants all gathered for trade. Economic trade existed throughout the empire due to the standing army stationed in the provinces. Central to the regional economy were independent gold fields. The Julla (merchants) would form partnerships, and the state would protect these merchants and the port cities of the Niger.

The Songhai economy was based on a clan system. The clan a person belonged to ultimately decided one’s occupation. The most common were metalworkers, fishermen, and carpenters. Lower caste participants consisted of mostly non-farm working immigrants, who at times were provided special privileges and held high positions in society. At the top were noblemen and direct descendants of the original Songhai people, followed by freemen and traders. At the bottom were war captives and European slaves obligated to labor, especially in farming. Historian James Olson describes the labor system as resembling modern day unions, with the empire possessing craft guilds that consisted of various mechanics and artisans

Criminal justice in Songhai was based mainly, if not entirely, on Islamic principles, especially during the rule of Askia the Great. Upper classes in society converted to Islam while lower classes often continued to follow traditional religions. Sermons emphasized obedience to the king. Sonni Ali established a system of government under the royal court, later to be expanded by Askia, which appointed governors and mayors to preside over local tributary states situated around the Niger valley. Local chiefs were still granted authority over their respective domains as long as they did not undermine Songhai policy.

Tax was imposed onto peripheral chiefdoms and provinces to ensure the dominance of Songhai, and in return these provinces were given almost complete autonomy. Songhai rulers only intervened in the affairs of these neighboring states when a situation became volatile, usually an isolated incident. Each town was represented by government officials, holding positions and responsibilities similar to today’s central bureaucrats.

The Yoruba States

While Ile-Ife is considered to be the spiritual homeland of the Yoruba people, numerous Yoruba states were eventually centralized within the modern Oyo Empire, which grew to become one of the largest African states.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the Yoruba states and their progression towards centralized government

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Yorubaland is the cultural region of the Yoruba people in West Africa. It spans the modern-day countries of Nigeria, Togo, and Benin. Its pre-modern history is based largely on oral traditions and legends. According to Yoruba religion, Oduduwa became the ancestor of the first divine king of the Yoruba.

- By the 8th century, Ile-Ife was already a powerful Yoruba kingdom, one of the earliest in Africa south of the Sahara-Sahel. Almost every Yoruba settlement traces its origin to princes of Ile-Ife. As such, Ife can be regarded as the cultural and spiritual homeland of the Yoruba nation.

- Ile-Ife was a settlement of substantial size between the 12th and 14th centuries, with houses featuring potsherd pavements. It is known worldwide for its ancient and naturalistic bronze as well as stone and terracotta sculptures, which reached their peak of artistic expression between 1200 and 1400.

- The mythical origins of the Oyo Empire lie with Oranyan, who made Oyo his new kingdom and became the first oba with the title of Alaafin of Oyo. The oral tradition holds that he left all his treasures in Ife and allowed another king named Adimu to rule there.

- Oyo had grown into a formidable inland power by the end of the 14th century, but it suffered military defeats at the hands of the Nupe led by Tsoede. During the 17th century, Oyo began a long stretch of growth, becoming a major empire. It never encompassed all Yoruba speaking people, but it was the most populous kingdom in Yoruba history. The key to Yoruba rebuilding Oyo was a stronger military and a more centralized government.

- In the second half of the 18th century, dynastic intrigues, palace coups, and failed military campaigns began to weaken the Oyo Empire. It became a protectorate of Great Britain in 1888 before further fragmenting into warring factions. The Oyo state ceased to exist as any sort of power in 1896.

Key Terms

- Oranyan: A Yoruba king from the kingdom of Ile-Ife; although last born, he was heir to Oduduwa. According to Yoruba history, he founded Oyo as its first Alaafin at around the year 1300 and one of his children, Eweka I, went on to become the first Oba of the Benin Empire.

- Yorubaland: The cultural region of the Yoruba people in West Africa. It spans the modern-day countries of Nigeria, Togo, and Benin, and covers a total land area of 142,114 square kilometers. The geocultural space contains an estimated 55 million people, the overwhelming majority of whom are ethnic Yorubas.

- Ile-Ife: An ancient Yoruba city in southwestern Nigeria (located in the present-day Osun State) that turned into the first powerful Yoruba kingdom, one of the earliest in Africa south of the Sahara-Sahel.

It is regarded as the cultural and spiritual homeland of the Yoruba nation. - Oduduwa: The King of Ile-Ife, whose name is generally ascribed to the ancestral dynasties of Yorubaland because he is held by the Yoruba to have been the ancestor of their numerous crowned kings. Following his posthumous deification, he was admitted to the Yoruba pantheon as an aspect of a primordial divinity of the same name.

Yorubaland: Introduction

Yorubaland is the cultural region of the Yoruba people in West Africa. It spans the modern-day countries of Nigeria, Togo, and Benin. Its pre-modern history is based largely on oral traditions and legends. According to Yoruba religion, Olodumare, the Supreme God, ordered Obatala to create the earth, but on Obatala’s way he found palm wine, which he drank and became intoxicated. Therefore, his younger brother, Oduduwa, took the three items of creation from him, climbed down from the heavens on a chain, and threw a handful of earth on the primordial ocean, then put a cockerel on it so that it would scatter the earth, thus creating the land on which Ile-Ife would be built. On account of his creation of the world, Oduduwa became the ancestor of the first divine king of the Yoruba, while Obatala is believed to have created the first Yoruba people out of clay. The meaning of the word “ife” in Yoruba is “expansion.” “Ile-Ife” is therefore in reference to the myth of origin, “The Land of Expansion.”

Ile-Ife

Evidence suggests that as of the 7th century BCE, the African peoples who lived in Yorubaland were not initially known as the Yoruba, though they shared a common ethnicity and language group. By the 8th century CE, Ile-Ife was already a powerful Yoruba kingdom, one of the earliest in Africa south of the Sahara-Sahel. Almost every Yoruba settlement traces its origin to princes of Ile-Ife. As such, Ife can be regarded as the cultural and spiritual homeland of the Yoruba nation. Archaeologically, the settlement at Ife can be dated to the 4th century BC, with urban structures appearing in the 12th century CE.

Until today, the Oòni (or king) of Ife claims direct descent from Oduduwa.

The city was a settlement of substantial size between the 12th and 14th centuries, with houses featuring potsherd pavements. Ile-Ife is known worldwide for its ancient and naturalistic bronze as well as stone and terracotta sculptures, which reached their peak of artistic expression between 1200 and 1400. In the period around 1300 the artists at Ife developed a refined and naturalistic sculptural tradition in terracotta, stone, and copper alloy—copper, brass, and bronze—many of which appear to have been created under the patronage of King Obalufon II, the man who today is identified as the Yoruba patron deity of brass casting, weaving, and regalia. After this period, production declined as political and economic power shifted to the nearby kingdom of Benin, which, like the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo, developed into a major empire.

Ile-Ife is known worldwide for its ancient and naturalistic bronze, stone, and terracotta sculptures, which reached their peak of artistic expression between 1200 and 1400.

The Rise of the Oyo Empire

The mythical origins of the Oyo Empire lie with Oranyan (also known as Oranmiyan), the second prince of Ile-Ife, who made Oyo his new kingdom and became the first oba with the title of Alaafin of Oyo (Alaafin means “owner of the palace” in Yoruba). The oral tradition holds that he left all his treasures in Ife and allowed another king, named Adimu, to rule there.

Oranyan was succeeded by Oba Ajaka, but he was deposed because he allowed his sub-chiefs too much independence. Leadership was then conferred upon Ajaka’s brother, Shango, who was later deified as the deity of thunder and lightning. Ajaka was restored after Shango’s death. His successor, Kori, managed to conquer the rest of what later historians would refer to as metropolitan Oyo. The heart of metropolitan Oyo was its capital at Oyo-Ile.

Oyo had grown into a formidable inland power by the end of the 14th century, but it suffered military defeats at the hands of the Nupe led by Tsoede. Sometime around 1535, the Nupe occupied Oyo and forced its ruling dynasty to take refuge in the kingdom of Borgu.

The Yoruba of Oyo went through an interregnum of eighty years as an exiled dynasty. However, they re-established Oyo to be more centralized and expansive than ever. During the 17th century, Oyo began a long stretch of growth, becoming a major empire. It never encompassed all Yoruba-speaking people, but it was the most populous kingdom in Yoruba history.

The Oyo Empire rose through the outstanding organizational skills of the Yoruba, gaining wealth from trade and its powerful cavalry. It was the most politically important state in the region from the mid-17th century to the late 18th century, holding sway not only over most of the other kingdoms in Yorubaland, but also over nearby African states, notably the Fon Kingdom of Dahomey in the modern Republic of Benin to the west.

The Power Of Oyo

The key to Yoruba rebuilding Oyo was a stronger military and a more centralized government. Oba Ofinran succeeded in regaining Oyo’s original territory from the Nupe. A new capital, Oyo-Igboho, was constructed, and the original became known as Old Oyo. The next oba, Eguguojo, conquered nearly all of Yorubaland. Despite a failed attempt to conquer the Benin Empire sometime between 1578 and 1608, Oyo continued to expand. The Yoruba allowed autonomy to the southeast of metropolitan Oyo, where the non-Yoruba areas could act as a buffer between Oyo and Imperial Benin. By the end of the 16th century, the Ewe and Aja states of modern Benin were paying tribute to Oyo.

The reinvigorated Oyo Empire began raiding southward as early as 1682. By the end of its military expansion, its borders would reach to the coast some 200 miles southwest of its capital. At the beginning, the people were concentrated in metropolitan Oyo. With imperial expansion, Oyo reorganized to better manage its vast holdings within and outside Yorubaland. It was divided into four layers defined by relation to the core of the empire. These layers were Metropolitan Oyo, southern Yorubaland, the Egbado Corridor, and Ajaland.

The Oyo Empire developed a highly sophisticated political structure to govern its territorial domains. Scholars have not determined how much of this structure existed prior to the Nupe invasion. Some of Oyo’s institutions are clearly derivative of early accomplishments in Ife.

The Oyo Empire was not a hereditary monarchy, nor an absolute one.

While the Alaafin of Oyo was supreme overlord of the people, he was not without checks on his power. The Oyo Mesi (seven councilors of the states) and the Yoruba Earth cult known as Ogboni kept the Oba’s power in check. The Oyo Mesi spoke for the politicians while the Ogboni spoke for the people, backed by the power of religion. The power of the Alaafin of Oyo in relation to the Oyo Mesi and Ogboni depended on his personal character and political shrewdness.

Oyo became the southern emporium of the trans-Saharan trade. Exchanges were made in salt, leather, horses, kola nuts, ivory, cloth, and slaves. The Yoruba of metropolitan Oyo were also highly skilled in craft making and iron work. Aside from taxes on trade products coming in and out of the empire, Oyo also became wealthy off the taxes imposed on its tributaries. Oyo’s imperial success made Yoruba a lingua franca almost to the shores of the Volta. Toward the end of the 18th century, the empire acted as a go-between for both the trans-Saharan and trans-Atlantic slave trade. By 1680, the Oyo Empire spanned over 150,000 square kilometers.

Decline

In the second half of the 18th century, dynastic intrigues, palace coups, and failed military campaigns began to weaken the Oyo Empire. Recurrent power struggles and resulting periods of interregnum created a vacuum, in which the power of regional commanders rose.

As Oyo tore itself apart via political intrigue, its vassals began taking advantage of the situation to press for independence. Some of them succeeded, and Oyo never regained its prominence in the region. It became a protectorate of Great Britain in 1888 before further fragmenting into warring factions. The Oyo state ceased to exist as any sort of power in 1896.