12.4 Muscle Contraction

Arm Wrestling

It’s obvious that a sport like arm wrestling (Figure 12.4.1) depends on muscle contractions. Arm wrestlers must contract muscles in their hands and arms, and keep them contracted in order to resist the opposing force exerted by their opponent. The wrestler whose muscles can contract with greater force wins the match.

What Is a Muscle Contraction?

A muscle contraction is an increase in the tension or a decrease in the length of a muscle. Muscle tension is the force exerted by the muscle on a bone or other object. A muscle contraction is isometric if muscle tension changes, but muscle length remains the same. An example of isometric muscle contraction is holding a book in the same position. A muscle contraction is isotonic if muscle length changes, but muscle tension remains the same. An example of isotonic muscle contraction is raising a book by bending the arm at the elbow. The termination of a muscle contraction of either type occurs when the muscle relaxes and returns to its non-contracted tension or length.

To use our arm wrestling example, if both arm wrestlers have equal strength and they are pulling with all their might, but there is no movement, that is isometric muscle contraction. However, as soon as one arm wrestler starts to win and is able to start pulling the opponents arm down, that is isotonic muscle contraction.

How a Skeletal Muscle Contraction Begins

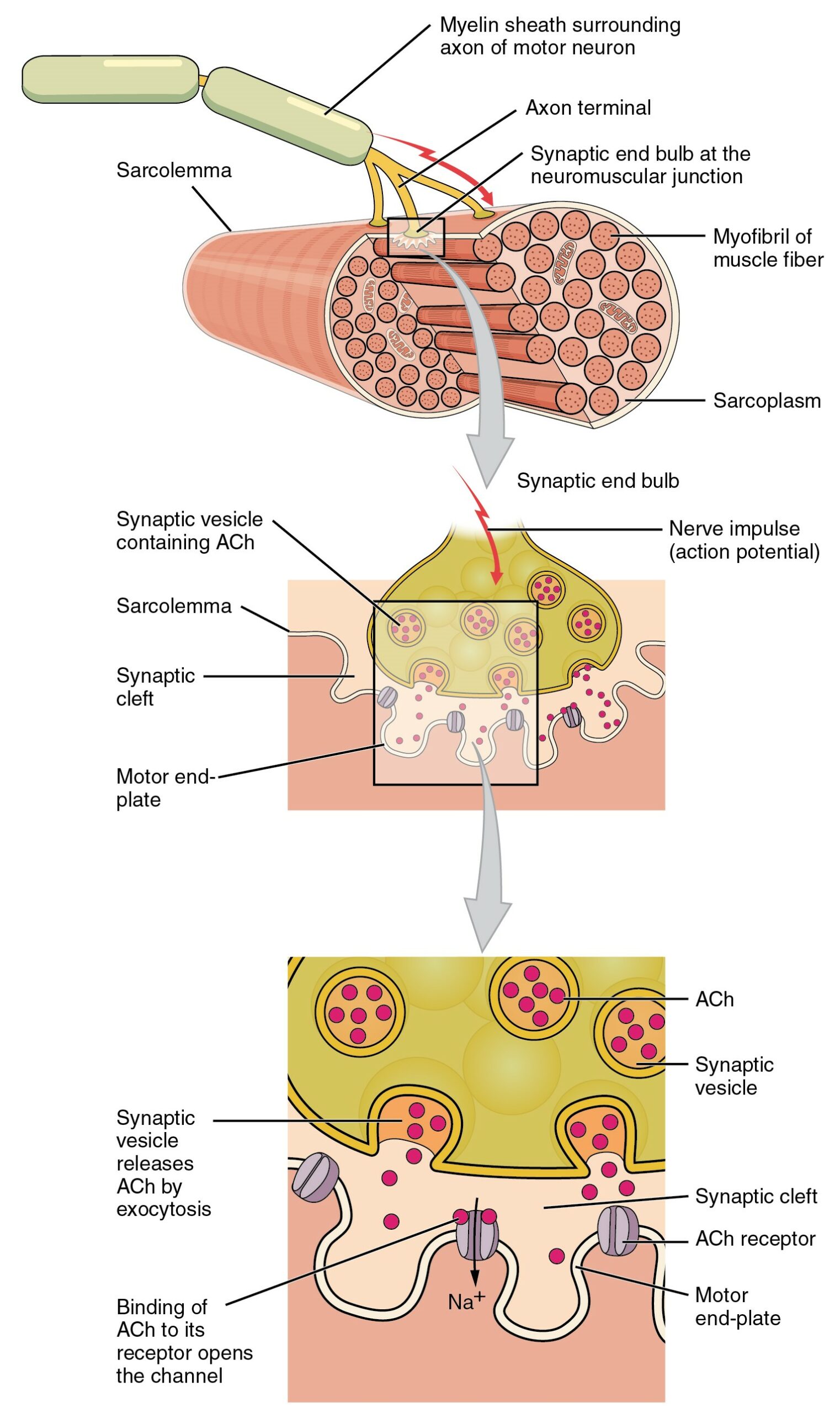

Excluding reflexes, all skeletal muscle contractions occur as a result of conscious effort originating in the brain. The brain sends electrochemical signals through the somatic nervous system to motor neurons that innervate muscle fibres (to review how the brain and neurons function, see the chapter Nervous System). A single motor neuron with multiple axon terminals is able to innervate multiple muscle fibres, thereby causing all of them to contract at the same time. The connection between a motor neuron axon terminal and a muscle fibre occurs at a site called a neuromuscular junction. This is a chemical synapse where a motor neuron transmits a signal to a muscle fibre to initiate a muscle contraction. The process by which a signal is transmitted at a neuromuscular junction is illustrated in Figure 12.4.2 below.

The sequence of events begins when an action potential is initiated in the cell body of a motor neuron, and the action potential is propagated along the neuron’s axon to the neuromuscular junction. Once the action potential reaches the end of the axon terminal, it causes the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) from synaptic vesicles in the axon terminal. The ACh molecules diffuse across the synaptic cleft and bind to receptors on the muscle fibre, thereby initiating a muscle contraction.

Sliding Filament Theory of Muscle Contraction

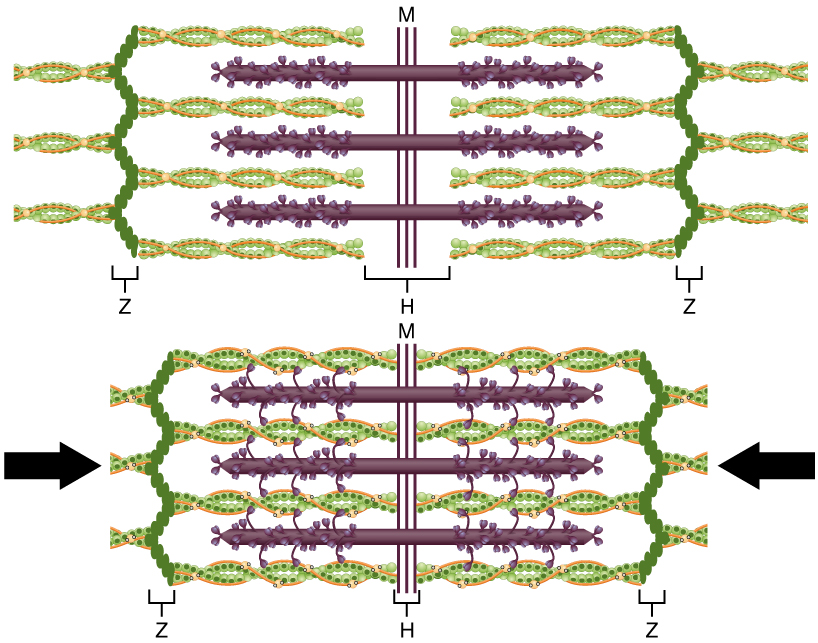

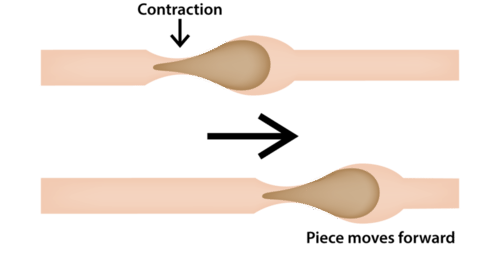

Once the muscle fibre is stimulated by the motor neuron, actin and myosin protein filaments within the skeletal muscle fibre slide past each other to produce a contraction. The sliding filament theory is the most widely accepted explanation for how this occurs. According to this theory, muscle contraction is a cycle of molecular events in which thick myosin filaments repeatedly attach to and pull on thin actin filaments, so the filaments slide over one another, as illustrated in Figure 12.4.3. The actin filaments are attached to Z discs, each of which marks the end of a sarcomere. The sliding of the filaments pulls the Z discs of a sarcomere closer together, thus shortening the sarcomere. As this occurs, the muscle contracts.

Crossbridge Cycling

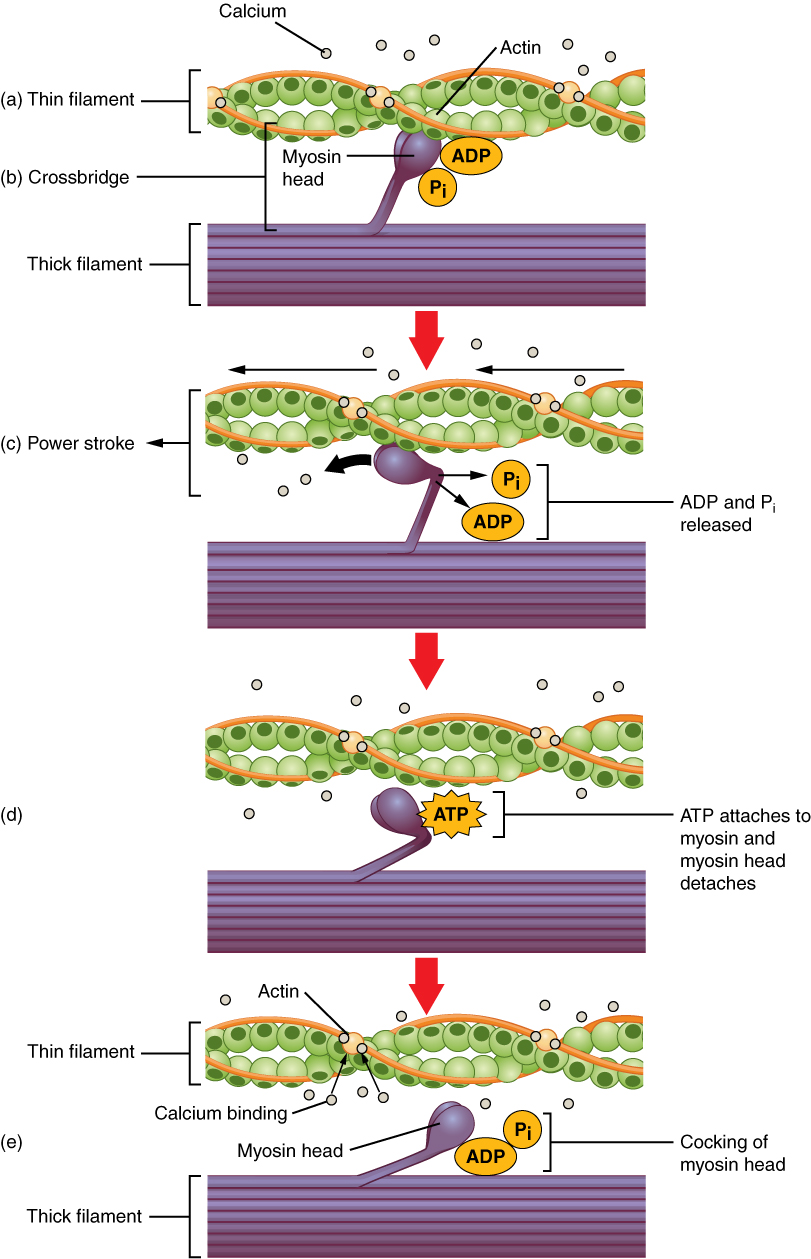

Crossbridge cycling is a sequence of molecular events that underlies the sliding filament theory. There are many projections from the thick myosin filaments, each of which consists of two myosin heads (you can see the projections and heads in Figures 12.4.3 and 12.4.4). Each myosin head has binding sites for ATP (or the products of ATP hydrolysis: ADP and Pi) and for actin. The thin actin filaments also have binding sites for the myosin heads. A crossbridge forms when a myosin head binds with an actin filament.

The process of crossbridge cycling is shown in the video “Muscle Contraction 3D” by 3DBiology (below), and in Figure 12.4.4. A crossbridge cycle begins when the myosin head binds to an actin filament. ADP and Pi are also bound to the myosin head at this stage. Next, a power stroke moves the actin filament inward toward the center of sarcomere, thereby shortening the sarcomere. At the end of the power stroke, ADP and Pi are released from the myosin head, leaving the myosin head attached just to the thin filament until another ATP binds to the myosin head. When ATP binds to the myosin head, it causes the myosin head to detach from the actin. ATP is once again split into ADP and Pi and the energy released is used to move the myosin head into a “cocked” position. Once in this position, the myosin head can bind to the actin filament again, and another crossbridge cycle begins.

Muscle Contraction 3D, 3DBiology, 2017.

Energy for Muscle Contraction

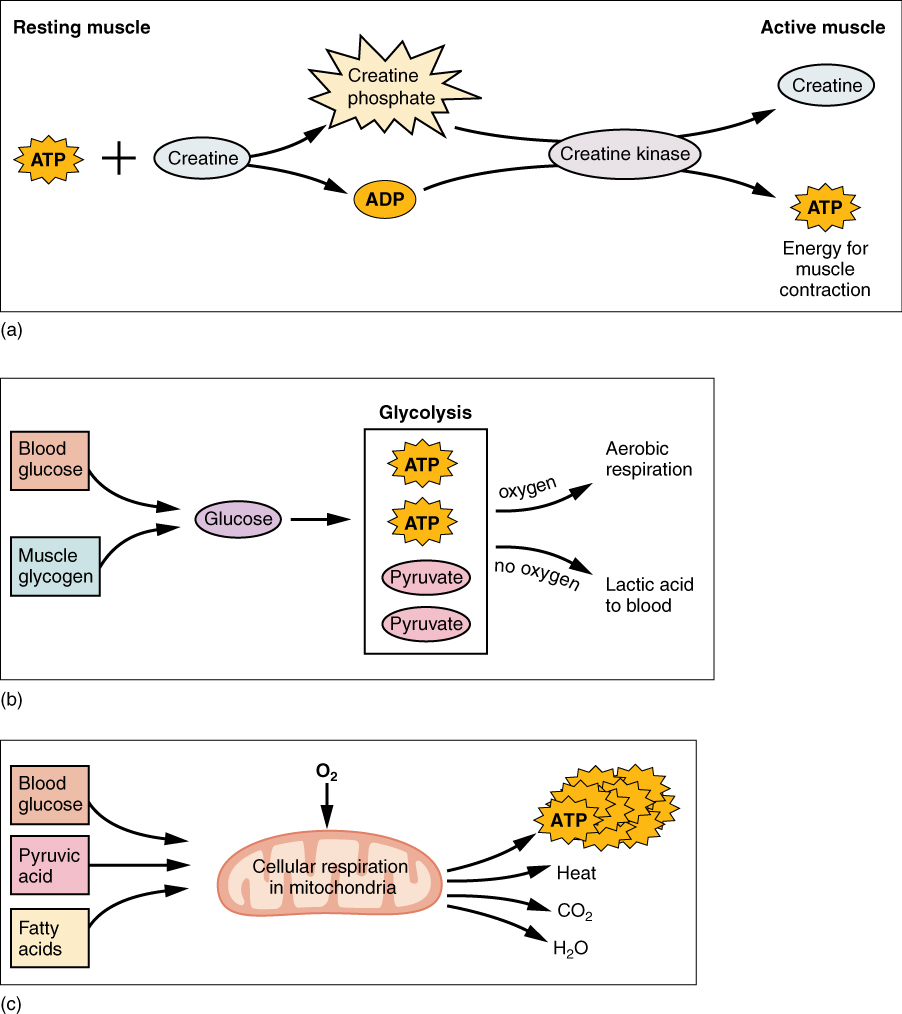

According to the sliding filament theory, ATP is needed to provide the energy for a muscle contraction. Where does this ATP come from? Actually, there are multiple potential sources, as illustrated in Figure 12.4.5 below.

- As you can see from the first diagram, some ATP is already available in a resting muscle. As a muscle contraction starts, this ATP is used up in just a few seconds. More ATP is generated from creatine phosphate, but this ATP is used up rapidly as well. It’s gone in another 15 seconds or so.

- Glucose from the blood and glycogen stored in muscle can then be used to make more ATP. Glycogen breaks down to form glucose, and each glucose molecule produces two molecules of ATP and two molecules of pyruvate. Pyruvate (as pyruvic acid) can be used in aerobic respiration if oxygen is available. Alternatively, pyruvate can be used in anaerobic respiration, if oxygen is not available. The latter produces lactic acid, which may contribute to muscle fatigue. Anaerobic respiration typically occurs only during strenuous exercise when so much ATP is needed that sufficient oxygen cannot be delivered to the muscle to keep up.

- Resting or moderately active muscles can get most of the ATP they need for contractions by aerobic respiration. This process takes place in the mitochondria of muscle cells. In the process, glucose and oxygen react to produce carbon dioxide, water, and many molecules of ATP.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

Basic research on muscle contraction, especially if it is interesting and hopeful, is often in the news, because muscle contractions are involved in so many different body processes and disorders, including heart failure and stroke.

- Heart failure is a chronic condition in which cardiac muscle cells cannot contract forcefully enough to keep body cells adequately supplied with oxygen. According to a 2016 report by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, 600,000 Canadians are living with heart failure and each year, 50,000 new cases are diagnosed. Heart failure costs the Canadian medical system more than $2.8 billion annually. In 2016, researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center identified a potential new target for the development of drugs to increase the strength of cardiac muscle contractions in patients with heart failure. The UT researchers found a previously unidentified protein involved in muscle contraction. The protein, which is very small, turns off the “brake” on the heart so it pumps blood more vigorously. At the molecular level, the protein affects the calcium-ion pump that controls muscle contraction. The scientists also found the same protein in slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibres. Interestingly, the protein is encoded by a stretch of mRNA that had been dismissed by scientists as non-coding RNA, commonly referred to as “junk” RNA. According to one of the researchers, “We dipped into the RNA ‘junk’ pile and came up with a hidden treasure.” This result is likely to lead to searches for additional treasures that might be hiding in the RNA junk pile.

- A stroke occurs when a blood clot lodges in an artery in the brain and cuts off blood flow to part of the brain. Approximately 6% of deaths in Canada are due to stroke and while men and women experiences strokes almost equally, women are more likely to die from a stroke. Damage from the clot associated with strokes would be reduced if the smooth muscles lining brain arteries relaxed following a stroke, because the arteries would dilate and allow greater blood flow to the brain. In a recent study undertaken at the Yale University School of Medicine, researchers determined that the muscles lining blood vessels in the brain actually contract after a stroke. This constricts the vessels, reduces blood flow to the brain, and appears to contribute to permanent brain damage. The hopeful takeaway of this finding is that it suggests a new target for stroke therapy.

12.4 Summary

- A muscle contraction is an increase in the tension or a decrease in the length of a muscle. A muscle contraction is isometric if muscle tension changes, but muscle length remains the same. It is isotonic if muscle length changes, but muscle tension remains the same.

- A skeletal muscle contraction begins with electrochemical stimulation of a muscle fibre by a motor neuron. This occurs at a chemical synapse called a neuromuscular junction. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine diffuses across the synaptic cleft and binds to receptors on the muscle fibre. This initiates a muscle contraction.

- Once stimulated, the protein filaments within the skeletal muscle fibre slide past each other to produce a contraction. The sliding filament theory is the most widely accepted explanation for how this occurs. According to this theory, thick myosin filaments repeatedly attach to and pull on thin actin filaments, thus shortening sarcomeres.

- Crossbridge cycling is a cycle of molecular events that underlies the sliding filament theory. Using energy in ATP, myosin heads repeatedly bind with and pull on actin filaments. This moves the actin filaments toward the center of a sarcomere, shortening the sarcomere and causing a muscle contraction.

- The ATP needed for a muscle contraction comes first from ATP already available in the cell, and more is generated from creatine phosphate. These sources are quickly used up. Glucose and glycogen can be broken down to form ATP and pyruvate. Pyruvate can then be used to produce ATP in aerobic respiration if oxygen is available, or it can be used in anaerobic respiration if oxygen is not available.

12.4 Review Questions

- What is a skeletal muscle contraction?

-

- Explain sliding filament theory and describe crossbridge cycling.

- If the acetylcholine receptors on muscle fibres were blocked by a drug, what do you think this would do to muscle contraction? Explain your answer.

- Explain how crossbridge cycling and sliding filament theory are related to each other.

- When does anaerobic respiration typically occur in human muscle cells?

- If there were no ATP available in a muscle, how would this affect crossbridge cycling? What would this do to muscle contraction?

12.4 Explore More

The Mechanism of Muscle Contraction: Sarcomeres, Action Potential, and the Neuromuscular Junction, Professor Dave Explains, 2019.

Aerobic vs Anaerobic Difference, Dorian Wilson, 2017.

Attributions

Figure 12.4.1

Armwrestling_Championships by Jnadler1 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 12.4.2

Motor_End_Plate_and_Innervation by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by 4.0) license.

Figure 12.4.3

Sliding_Filament_Model_of_Muscle_Contraction by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by 4.0) license.

Figure 12.4.4

Skeletal_Muscle_Contraction by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by 4.0) license.

Figure 12.4.5

Muscle_Metabolism by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by 4.0) license.

References

3DBiology. (2017). Muscle contraction 3D. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrHsiHazpsw

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 27). Figure 10.6 Motor end-plate and innervation [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-2-skeletal-muscle

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 27). Figure 10.10 The sliding filament model of muscle contraction [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-3-muscle-fiber-contraction-and-relaxation

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 27). Figure 10.11 Skeletal muscle contraction [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-3-muscle-fiber-contraction-and-relaxation

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 27). Figure 10.12 Muscle metabolism [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-3-muscle-fiber-contraction-and-relaxation

Dorian Wilson. (2017, March 8). Aerobic vs anaerobic difference. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Y_FdjI2v4I&feature=youtu.be

Heart and Stroke Foundation. (2016). 2016 Report on the health of Canadians: The burden of heart failure. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/2017-heart-month/heartandstroke-reportonhealth-2016.ashx?la=en

Hill, R. A., Tong, L., Yuan, P., Murikinati, S., Gupta, S., & Grutzendler, J. (2015). Regional blood flow in the normal and ischemic brain is controlled by arteriolar smooth muscle cell contractility and not by capillary pericytes. Neuron, 87(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.001

UTSouthwestern Newsroom. (2016, January 14). Researchers find a small protein that plays a big role in heart muscle contraction [online article]. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/newsroom/articles/year-2016/dworf-protein-olson.html

What we do. (n.d.). Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/what-we-do

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

http://humanbiology.pressbooks.tru.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/06/human-heartbeat-daniel_simon.mp3

Lub, Dub

Lub dub, lub dub, lub dub... That’s how the sound of a beating heart is typically described. Those are also the only two sounds that should be audible when listening to a normal, healthy heart through a stethoscope, as in Figure 14.3.1. If a doctor hears something different from the normal lub dub sounds, it’s a sign of a possible heart abnormality. What causes the heart to produce the characteristic lub dub sounds? Read on to find out.

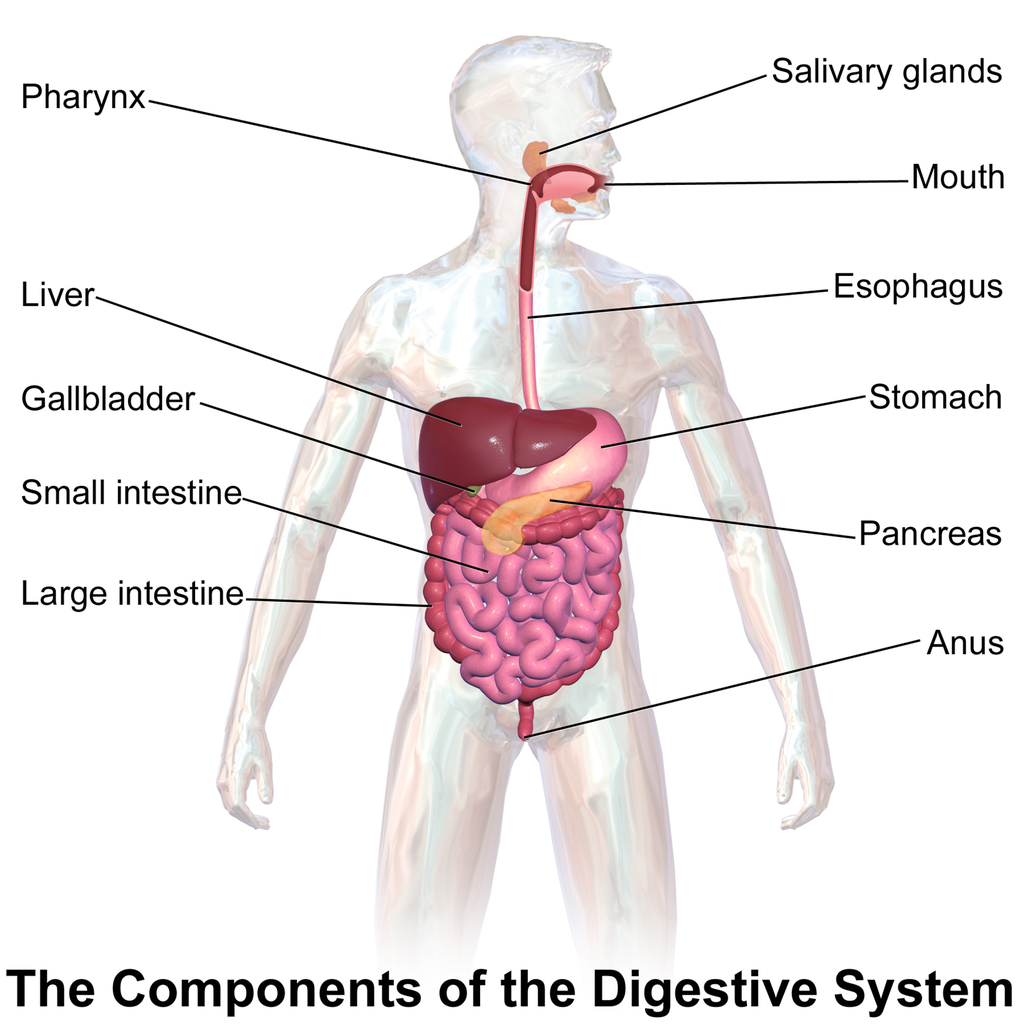

Introduction to the Heart

The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum (breastbone), slightly to the left of the center of the chest. A normal adult heart is about the size of a fist. The function of the heart is to pump blood through blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. The continuous flow of blood through the system is necessary to provide all the cells of the body with oxygen and nutrients, and to remove their metabolic wastes.

Structure of the Heart

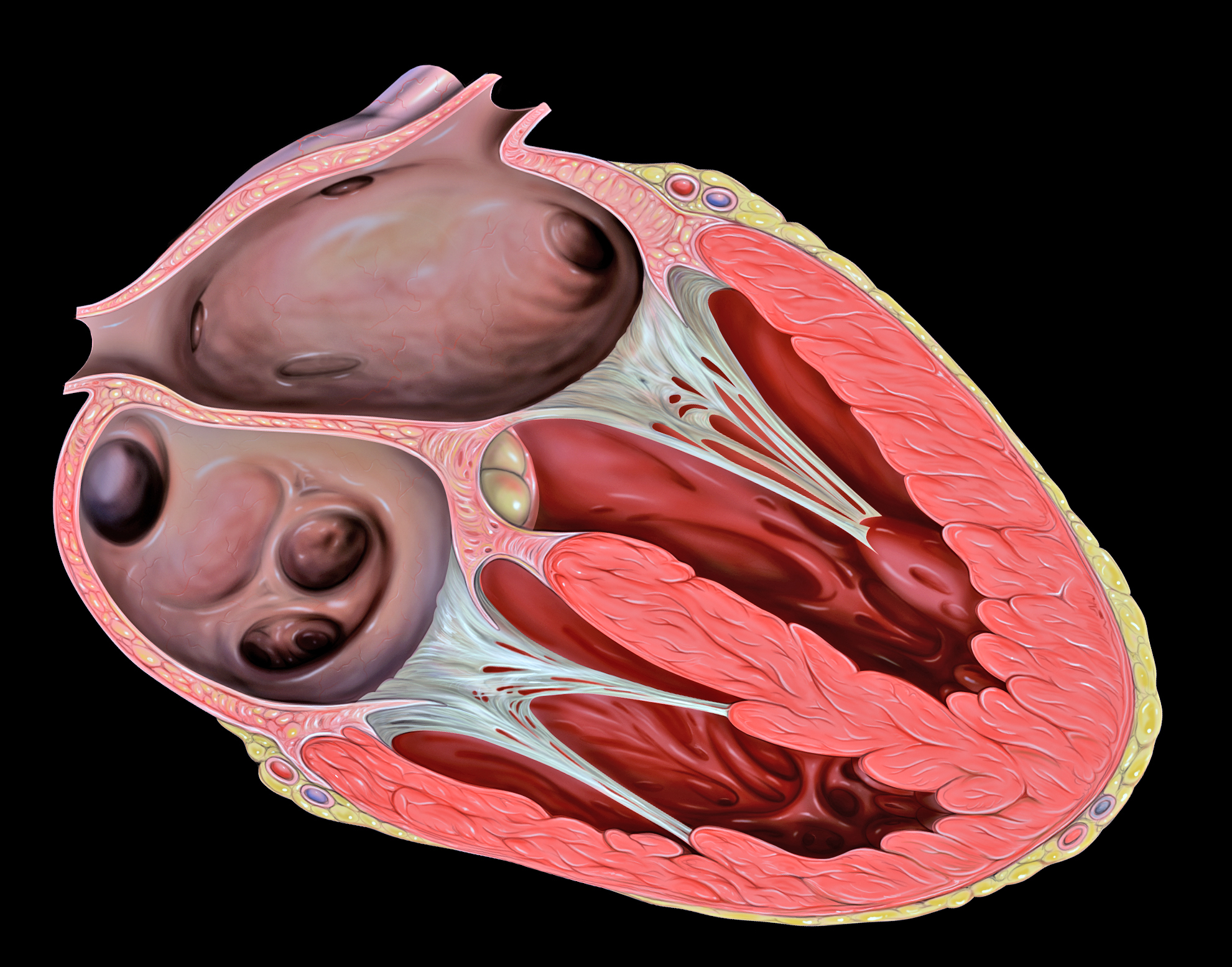

The heart has a thick muscular wall that consists of several layers of tissue. Internally, the heart is divided into four chambers through which blood flows. Because of heart valves, blood flows in just one direction through the chambers.

Heart Wall

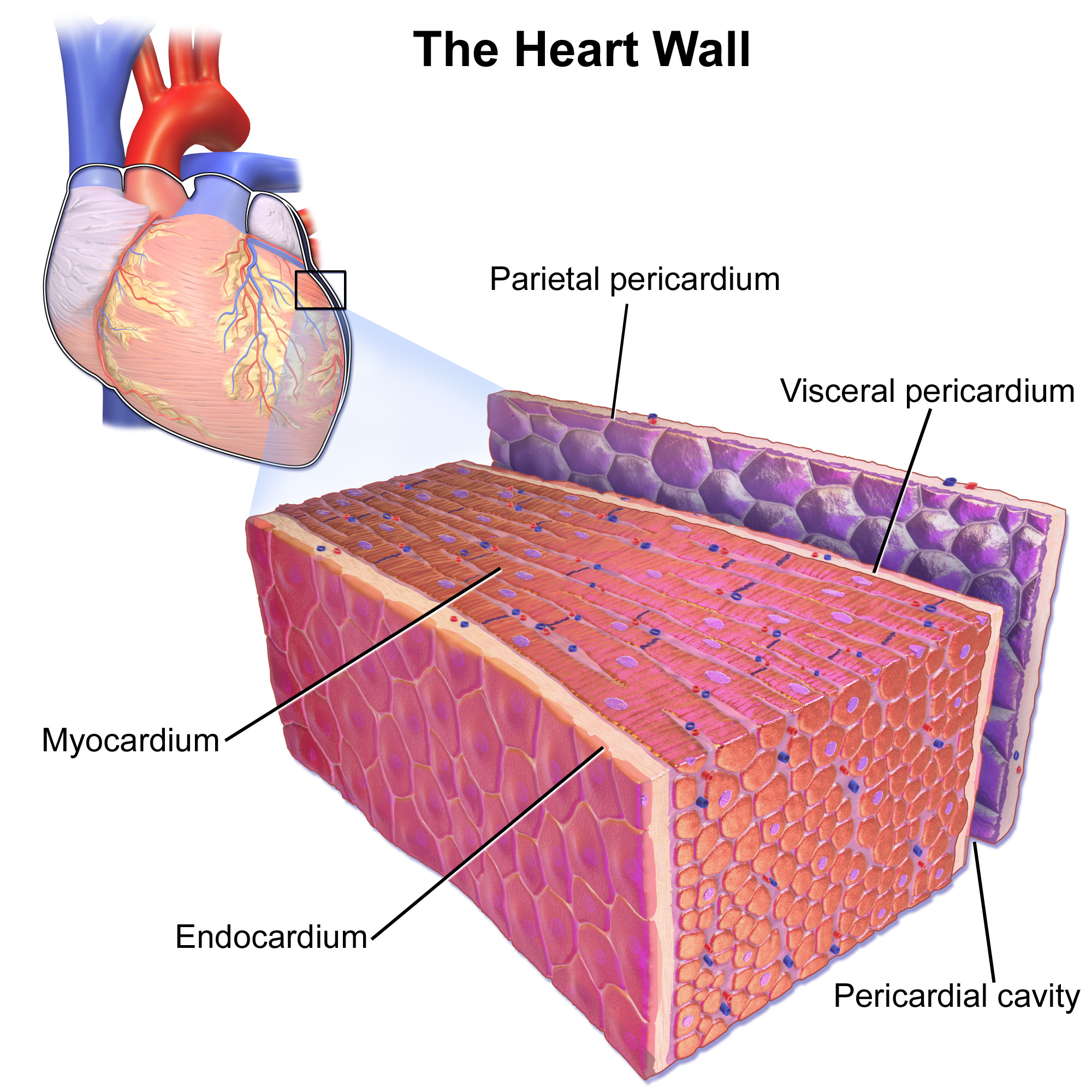

As shown in Figure 14.3.2, the wall of the heart is made up of three layers, called the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium.

- The endocardium is the innermost layer of the heart wall. It is made up primarily of simple epithelial cells. It covers the heart chambers and valves. A thin layer of connective tissue joins the endocardium to the myocardium.

- The myocardium is the middle and thickest layer of the heart wall. It consists of cardiac muscle surrounded by a framework of collagen. There are two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium: cardiomyocytes — which have the ability to contract easily — and pacemaker cells, which conduct electrical impulses that cause the cardiomyocytes to contract. About 99 per cent of cardiac muscle cells are cardiomyocytes, and the remaining one per cent is pacemaker cells. The myocardium is supplied with blood vessels and nerve fibres via the pericardium.

- The pericardium is a protective sac that encloses and protects the heart. The pericardium consists of two membranes (visceral pericardium and parietal pericardium), between which there is a fluid-filled cavity. The fluid helps to cushion the heart, and also lubricates its outer surface.

Heart Chambers

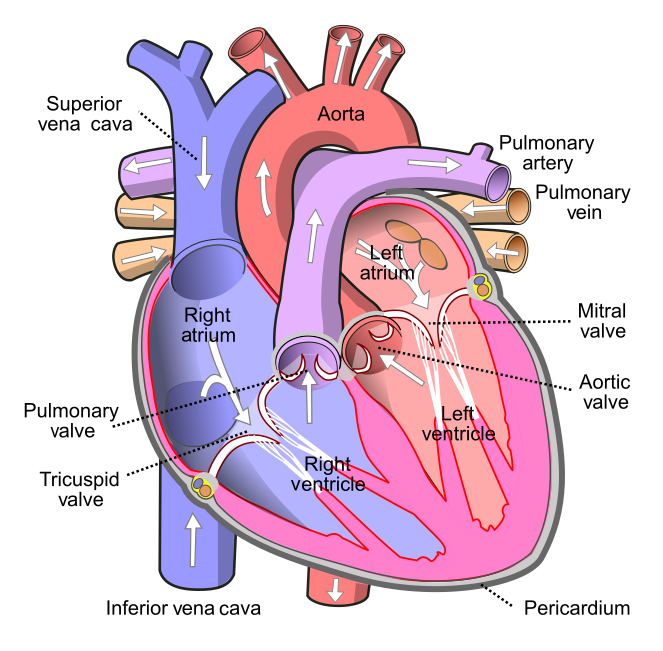

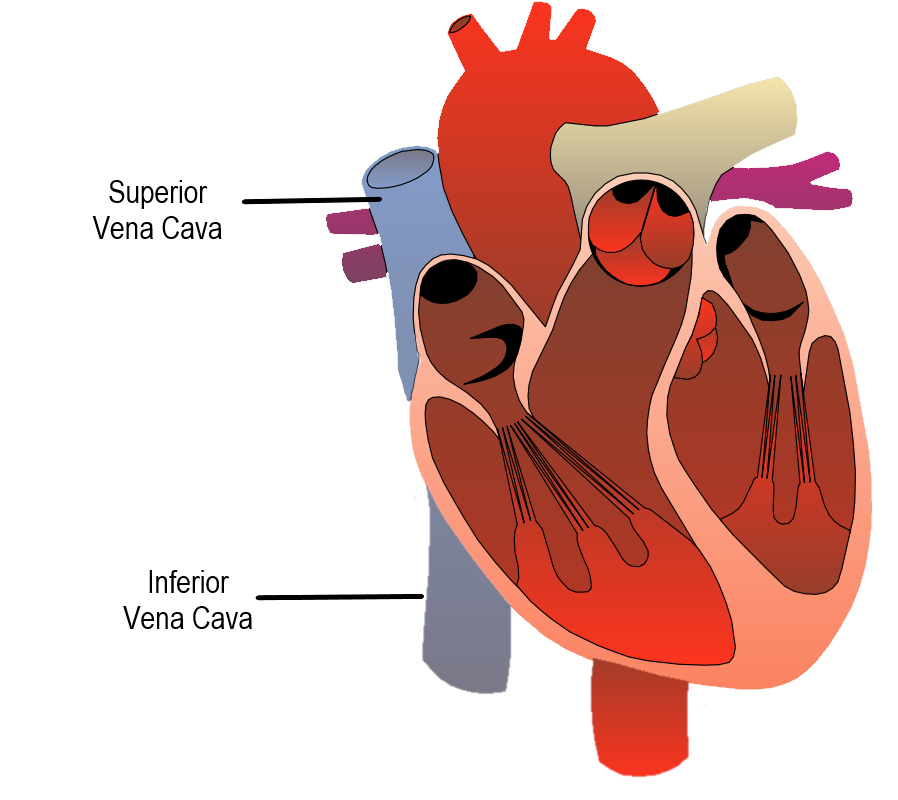

As shown in Figure 14.3.3 the four chambers of the heart include two upper chambers called atria (singular, atrium), and two lower chambers called ventricles. The atria are also referred to as receiving chambers, because blood coming into the heart first enters these two chambers. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the upper and lower body through the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, respectively. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs through the pulmonary veins. The ventricles are also referred to as discharging chambers, because blood leaving the heart passes out through these two chambers. The right ventricle discharges blood to the lungs through the pulmonary artery, and the left ventricle discharges blood to the rest of the body through the aorta. The four chambers are separated from each other by dense connective tissue consisting mainly of collagen.

Heart Valves

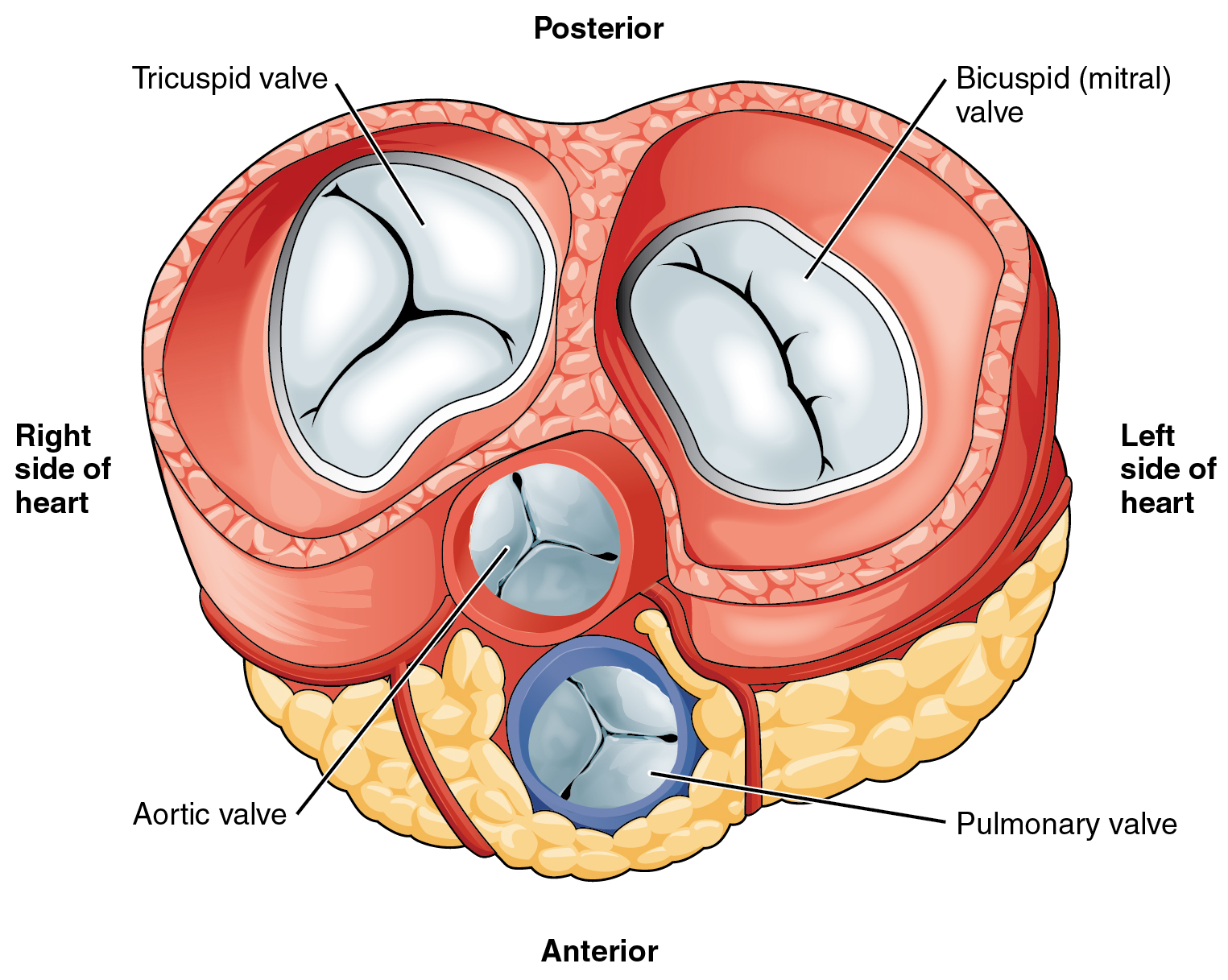

Figure 14.3.4 shows the location of the heart's four valves in a top-down view, looking down at the heart as if the arteries and veins feeding into and out of the heart were removed. The heart valves allow blood to flow from the atria to the ventricles, and from the ventricles to the pulmonary artery and aorta. The valves are constructed in such a way that blood can flow through them in only one direction, thus preventing the backflow of blood. Figure 14.3.5 shows how valves open to let blood into the appropriate chamber, and then close to prevent blood from moving in the wrong direction and the next chamber contracts. The four valves are the:

- Tricuspid atrioventricular valve, (can be shortened to tricuspid AV valve) which allows blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

- Bicuspid atrioventricular valve (also know as the mitral valve), which allows blood to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle.

- Pulmonary semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery.

- Aortic semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

The two atrioventricular (AV) valves prevent backflow when the ventricles are contracting, while the semilunar valves prevent backflow from vessels. This means that the AV valves must withstand much more pressure than do the semilunar valves. In order to withstand the force of the ventricles contracting (to prevent blood from backflowing into the atria), the AV valves are reinforced with structures called chordae tendineae — tendon-like cords of connective tissue which anchor the valve and prevent it from prolapse. Figure 14.3.6 shows the structure and location of the chordae tendoneae.

The chordae tendoneae are under such force that they need special attachments to the interior of the ventricles where they anchor. Papillary muscles are specialized muscles in the interior of the ventricle that provide a strong anchor point for the chordae tendineae.

Coronary Circulation

The cardiomyocytes of the muscular walls of the heart are very active cells, because they are responsible for the constant beating of the heart. These cells need a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients. The carbon dioxide and waste products they produce also must be continuously removed. The blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells make up the coronary circulation. Note that the blood vessels of the coronary circulation supply heart tissues with blood, and are different from the blood vessels that carry blood to and from the chambers of the heart as part of the general circulation. Coronary arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle cells. Coronary veins remove deoxygenated blood from the heart muscles cells.

- There are two coronary arteries — a right coronary artery that supplies the right side of the heart, and a left coronary artery that supplies the left side of the heart. These arteries branch repeatedly into smaller and smaller arteries and finally into capillaries, which exchange gases, nutrients, and waste products with cardiomyocytes.

- At the back of the heart, small cardiac veins drain into larger veins, and finally into the great cardiac vein, which empties into the right atrium. At the front of the heart, small cardiac veins drain directly into the right atrium.

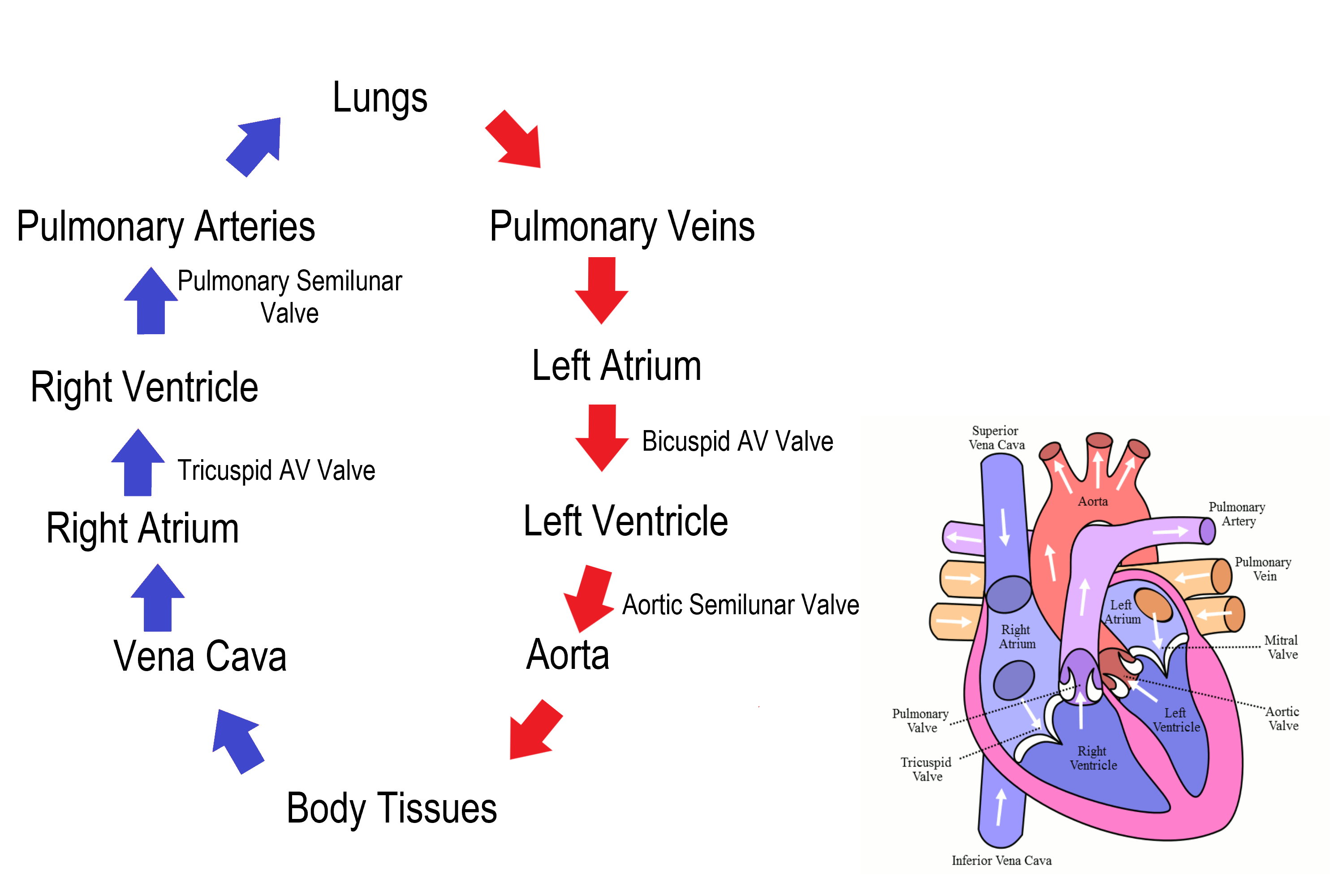

Blood Circulation Through the Heart

Figure 14.3.7 shows how blood circulates through the chambers of the heart. The right atrium collects blood from two large veins, the superior vena cava (from the upper body) and the inferior vena cava (from the lower body). The blood that collects in the right atrium is pumped through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. From the right ventricle, the blood is pumped through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery. The pulmonary artery carries the blood to the lungs, where it enters the pulmonary circulation, gives up carbon dioxide, and picks up oxygen. The oxygenated blood travels back from the lungs through the pulmonary veins (of which there are four), and enters the left atrium of the heart. From the left atrium, the blood is pumped through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From the left ventricle, the blood is pumped through the aortic valve into the aorta, which subsequently branches into smaller arteries that carry the blood throughout the rest of the body. After passing through capillaries and exchanging substances with cells, the blood returns to the right atrium via the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, and the process begins anew.

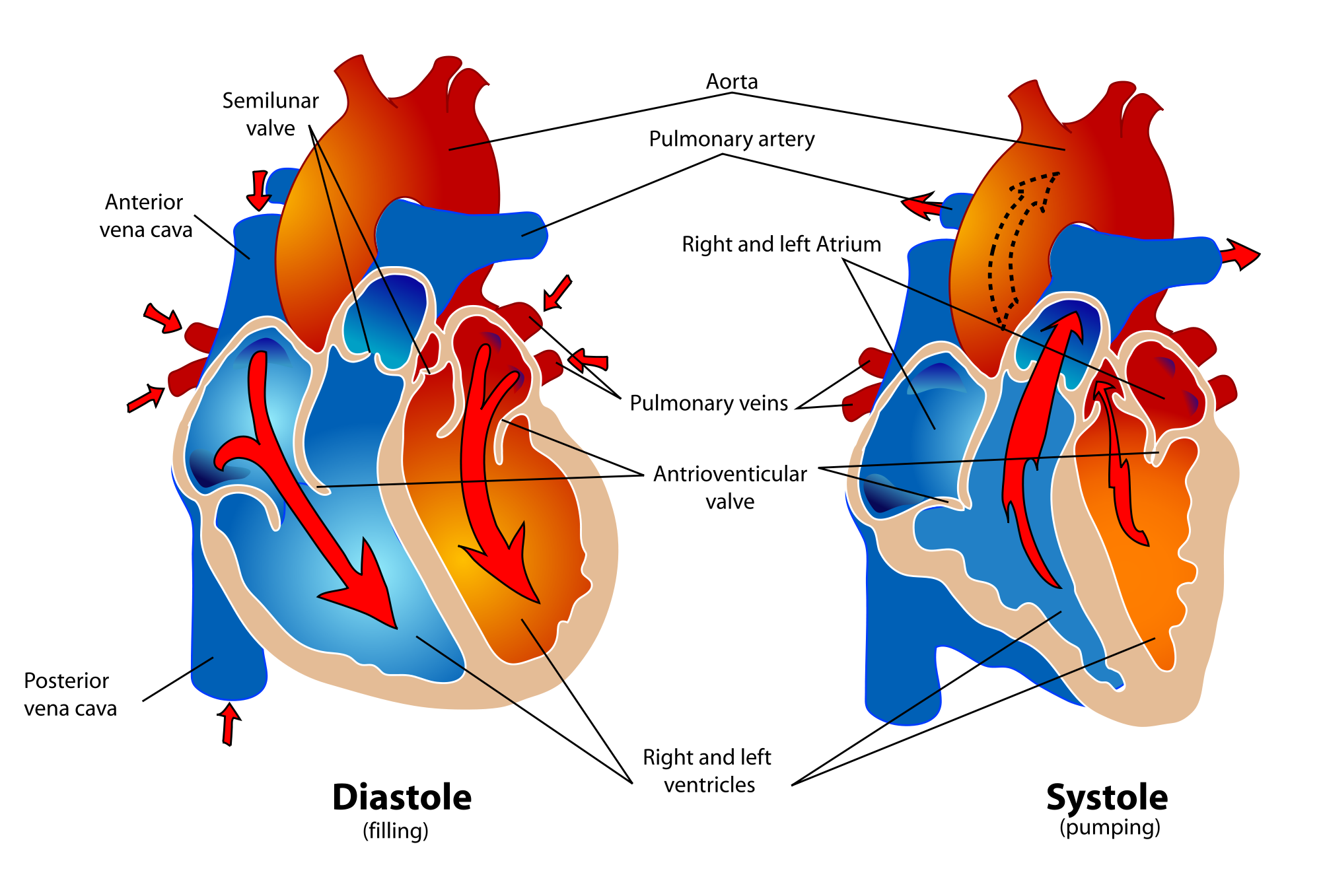

Cardiac Cycle

The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat, which includes one iteration of the lub and dub sounds heard through a stethoscope. During the cardiac cycle, the atria and ventricles work in a coordinated fashion so that blood is pumped efficiently through and out of the heart. The cardiac cycle includes two parts, called diastole and systole, which are illustrated in the diagrams in Figure 14.3.8.

- During diastole, the atria contract and pump blood into the ventricles, while the ventricles relax and fill with blood from the atria.

- During systole, the atria relax and collect blood from the lungs and body, while the ventricles contract and pump blood out of the heart.

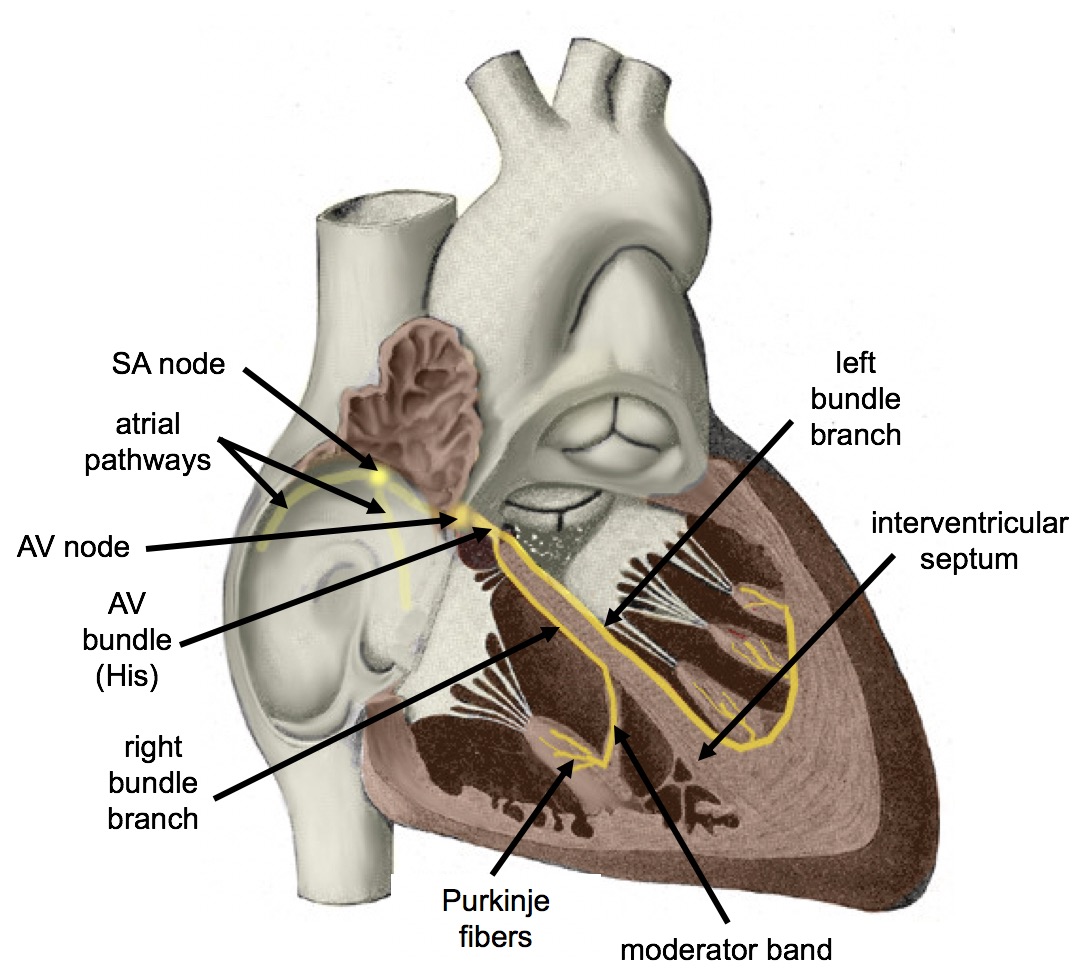

Electrical Stimulation of the Heart

The normal, rhythmical beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells, which are located in an area of the heart called the sinoatrial node (shown in Figure 14.3.9). The pacemaker cells create electrical signals with the movement of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and calcium ions) into and out of the cells. For each cardiac cycle, an electrical signal rapidly travels first from the sinoatrial node, to the right and left atria so they contract together. Then, the signal travels to another node, called the atrioventricular node (Figure 14.3.9), and from there to the right and left ventricles (which also contract together), just a split second after the atria contract.

The normal sinus rhythm of the heart is influenced by the autonomic nervous system through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. These nerves arise from two paired cardiovascular centers in the medulla of the brainstem. The parasympathetic nerves act to decrease the heart rate, and the sympathetic nerves act to increase the heart rate. Parasympathetic input normally predominates. Without it, the pacemaker cells of the heart would generate a resting heart rate of about 100 beats per minute, instead of a normal resting heart rate of about 72 beats per minute. The cardiovascular centers receive input from receptors throughout the body, and act through the sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, as needed. Increased physical activity, for example, is detected by receptors in muscles, joints, and tendons. These receptors send nerve impulses to the cardiovascular centers, causing sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, and allowing more blood to flow to the muscles.

Besides the autonomic nervous system, other factors can also affect the heart rate. For example, thyroid hormones and adrenal hormones (such as epinephrine) can stimulate the heart to beat faster. The heart rate also increases when blood pressure drops or the body is dehydrated or overheated. On the other hand, cooling of the body and relaxation — among other factors — can contribute to a decrease in the heart rate.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

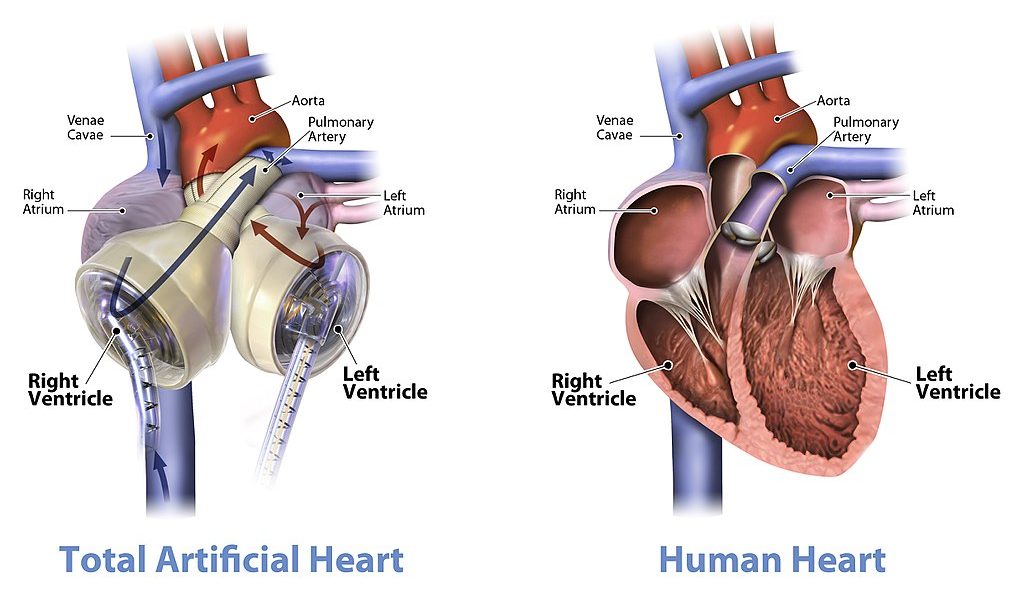

When a patient’s heart is too diseased or damaged to sustain life, a heart transplant is likely to be the only long-term solution. The first successful heart transplant was undertaken in South Africa in 1967. There are over 2,200 Canadians walking around today because of life-saving heart transplant surgery. Approximately 180 heart transplant surgeries are performed each year, but there are still so many Canadians on the transplant list that some die while waiting for a heart. The problem is that far too few hearts are available for transplant — there is more demand (people waiting for a heart transplant) than supply (organ donors). Sometimes, recipient hopefuls will receive a device called a Total Artificial Heart (see Figure 14.3.10), which can buy them some time until a donor heart becomes available.

Watch the video below "Total artificial heart option..." from Stanford Health Care to see how it works:

https://youtu.be/1PtxaxcPnGc

Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage), Stanford Health Care, 2014.

14.3 Summary

- The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum and slightly to the left of the center of the chest. Its function is to pump blood through the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system.

- The wall of the heart consists of three layers. The middle layer, the myocardium, is the thickest layer and consists mainly of cardiac muscle. The interior of the heart consists of four chambers, with an upper atrium and lower ventricle on each side of the heart. Blood enters the heart through the atria, which pump it to the ventricles. Then the ventricles pump blood out of the heart. Four valves in the heart keep blood flowing in the correct direction and prevent backflow.

- The coronary circulation consists of blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells, and is different from the general circulation of blood through the heart chambers. There are two coronary arteries that supply the two sides of the heart with oxygenated blood. Cardiac veins drain deoxygenated blood back into the heart.

- Deoxygenated blood flows into the right atrium through veins from the upper and lower body (superior and inferior vena cava, respectively), and oxygenated blood flows into the left atrium through four pulmonary veins from the lungs. Each atrium pumps the blood to the ventricle below it. From the right ventricle, deoxygenated blood is pumped to the lungs through the two pulmonary arteries. From the left ventricle, oxygenated blood is pumped to the rest of the body through the aorta.

- The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat. It includes diastole — when the atria contract — and systole, when the ventricles contract.

- The normal, rhythmic beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node. Electrical signals from the pacemaker cells travel to the atria, and cause them to contract. Then, the signals travel to the atrioventricular node and from there to the ventricles, causing them to contract. Electrical stimulation from the autonomic nervous system and hormones from the endocrine system can also influence heartbeat.

14.3 Review Questions

- What is the heart, where is located, and what is its function?

-

- Describe the coronary circulation.

- Summarize how blood flows into, through, and out of the heart.

- Explain what controls the beating of the heart.

- What are the two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium? What are the differences between these two types of cells?

- Explain why the blood from the cardiac veins empties into the right atrium of the heart. Focus on function (rather than anatomy) in your answer.

14.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM

Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face, TED, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M

Watch a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI

A Change of Heart: My Transplant Experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse, TEDx Talks, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk

Heart Transplant Recipient Meets Donor Family For The First Time, WMC Health, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 14.3.1

- Female clinician dressed in scrubs using a stethoscope by Amanda Mills, USCDCP, on Pixnio is used under a CC0 public domain certification license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/publicdomain/).

- Human heart beating loud and strong (audio) by Daniel Simion on Soundbible.com is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.2

Blausen_0470_HeartWall by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.3

Diagram_of_the_human_heart_(cropped).svg by Wapcaplet on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 14.3.4

Heart_Valves by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.5

CG_Heart Valve Animation by DrJanaOfficial on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 14.3.6

Heart_tee_four_chamber_view by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator from Yale University School of Medicine, on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) license.

Figure 14.3.7

Circulation of blood through the heart by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license. [Original image in the bottom right is by Wapcaplet / CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Figure 14.3.8

Human_healthy_pumping_heart_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Common is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 14.3.9

Cardiac_Conduction_System by Cypressvine on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 19.12 Heart valves with the atria and major vessels removed [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 19.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/19-1-heart-anatomy#fig-ch20_01_04

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. (n.d.). https://www.heartandstroke.ca/

Sliwa, K., Zilla, P. (2017, December 7). 50th anniversary of the first human heart transplant—How is it seen today? European Heart Journal, 38(46):3402–3404. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx695

Stanford Health Care. (2014, December 3). Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PtxaxcPnGc&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2012, March 21). Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM&feature=youtu.be

TEDx Talks. (2018, April 18). A change of heart: My transplant experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI&feature=youtu.be

UMagazine. (2015, Fall). The cutting edge: Patient first to bridge from experimental total artificial heart to transplant. UCLA Health. https://www.uclahealth.org/u-magazine/patient-first-to-bridge-from-experimental-total-artificial-heart-to-transplant

UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids. (2018, February 7). Watch a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M&feature=youtu.be

WMC Health. (2018, September 13). Heart transplant recipient meets donor family for the first time. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Bulging Veins

Why do bodybuilders have such prominent veins? Bulging muscles push surface veins closer to the skin. Combine that with a virtual lack of subcutaneous fat, and you have bulging veins, as well as bulging muscles. Veins are one of three major types of blood vessels in the cardiovascular system.

Types of Blood Vessels

Blood vessels are the part of the cardiovascular system that transports blood throughout the human body. There are three major types of blood vessels. Besides veins, they include arteries and capillaries.

Arteries

Arteries are defined as blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart. Blood flows through arteries largely because it is under pressure from the pumping action of the heart. It should be noted that coronary arteries, which supply heart muscle cells with blood, travel toward the heart, but not as part of the blood flow that travels through the chambers of the heart. Most arteries, including coronary arteries, carry oxygenated blood, but there are a few exceptions, most notably the pulmonary artery. This artery carries deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs, where it picks up oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. In virtually all other arteries, the hemoglobin in red blood cells is highly saturated with oxygen (95–100 per cent). These arteries distribute oxygenated blood to tissues throughout the body.

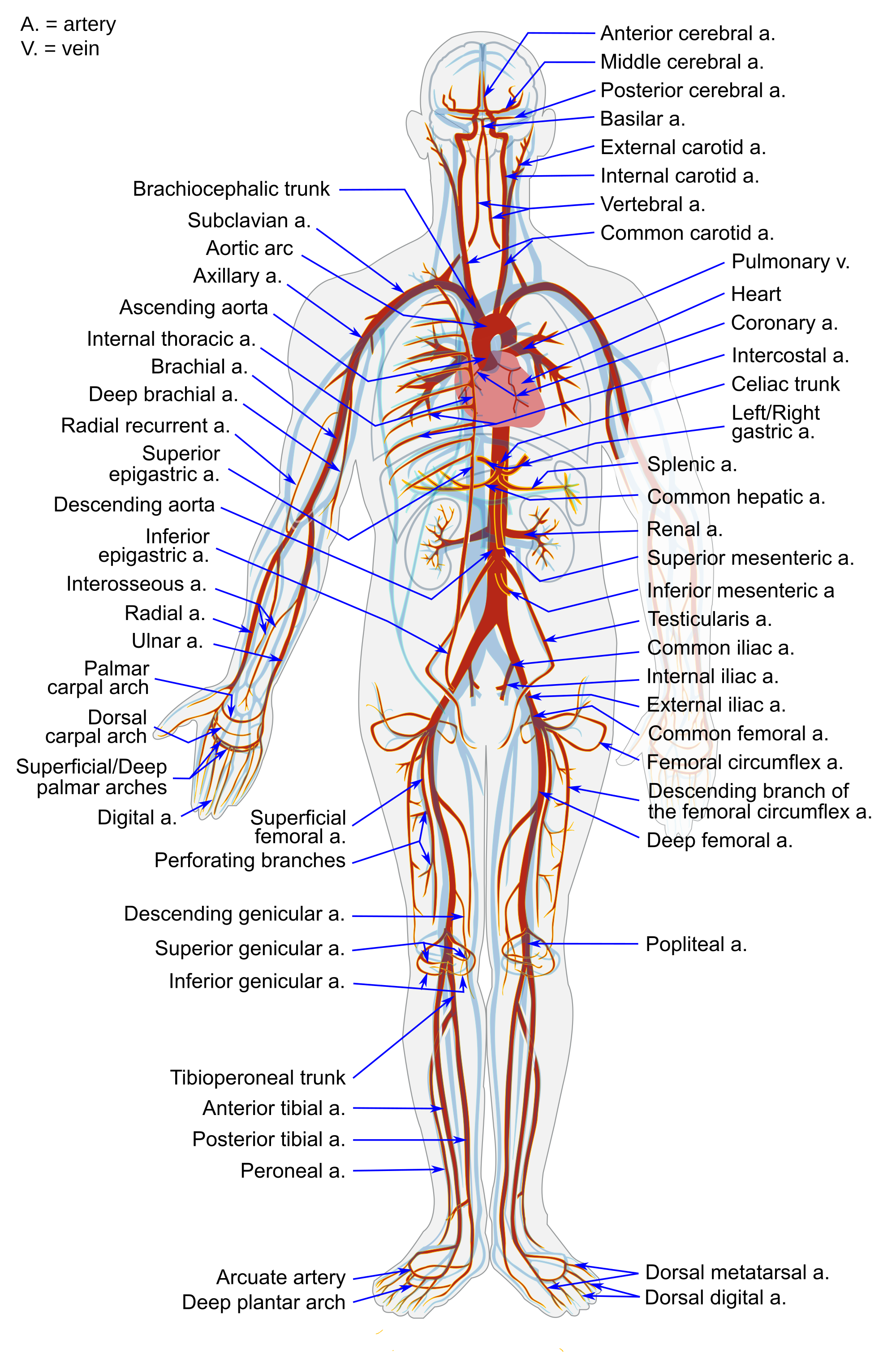

The largest artery in the body is the aorta, which is connected to the heart and extends down into the abdomen (see Figure 14.4.2). The aorta has high-pressure, oxygenated blood pumped directly into it from the left ventricle of the heart. The aorta has many branches, and the branches subdivide repeatedly, with the subdivisions growing smaller and smaller in diameter. The smallest arteries are called arterioles.

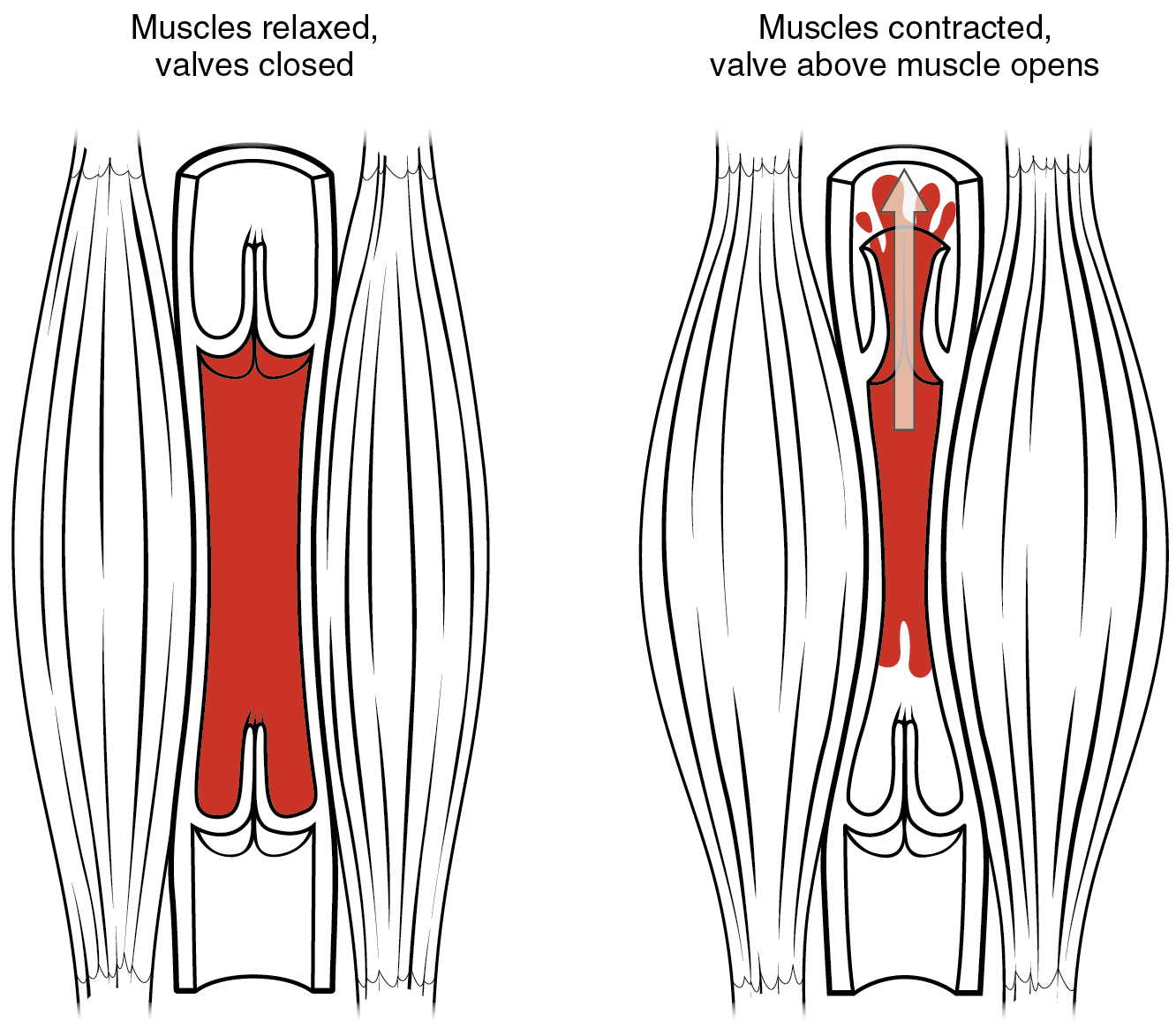

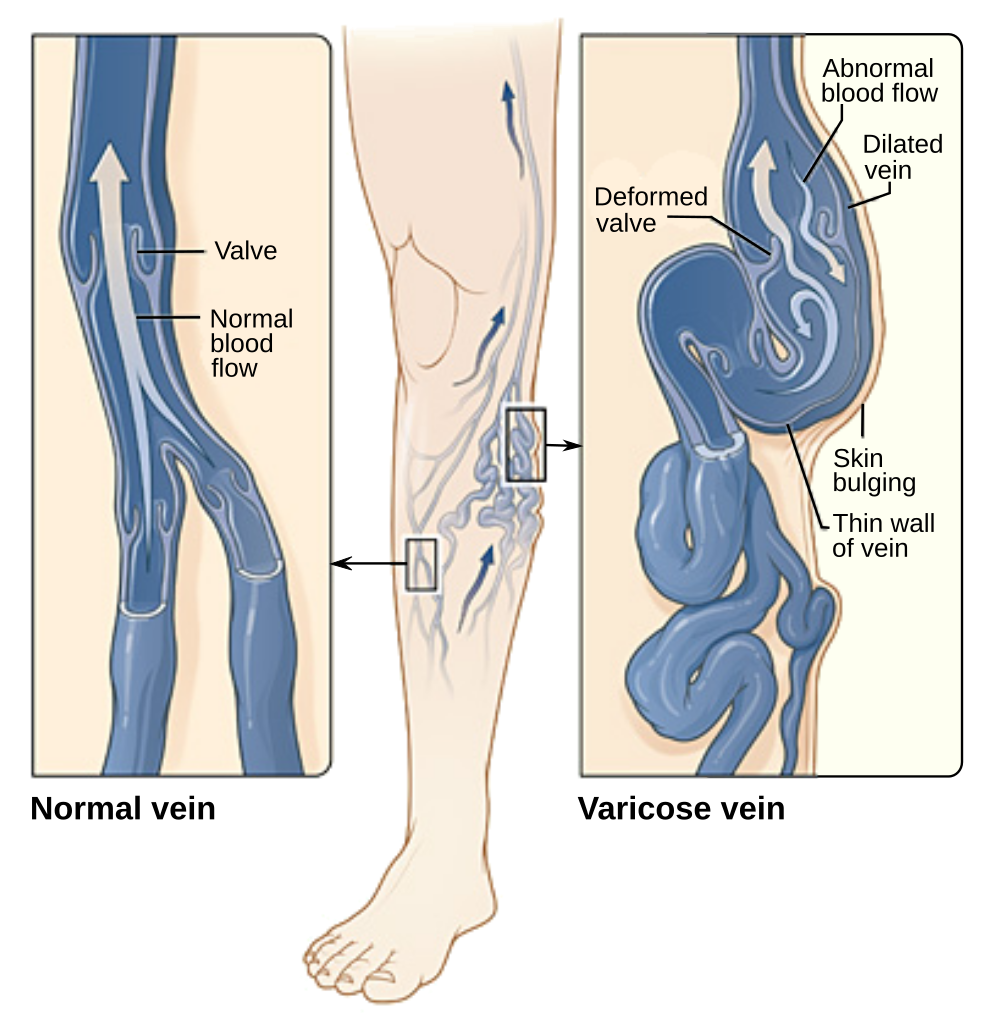

Veins

Veins are defined as blood vessels that carry blood toward the heart. Blood traveling through veins is not under pressure from the beating heart. It gets help moving along by the squeezing action of skeletal muscles, for example, when you walk or breathe. It is also prevented from flowing backward by valves in the larger veins, as illustrated in Figure 14.4.3. and as seen in the ultrasonography image in Figure 14.4.4. Veins are called capacitance blood vessels, because the majority of the body’s total volume of blood (about 60 per cent) is contained within veins.

Most veins carry deoxygenated blood, but there are a few exceptions, including the four pulmonary veins. These veins carry oxygenated blood from the lungs to the heart, which then pumps the blood to the rest of the body. In virtually all other veins, hemoglobin is relatively unsaturated with oxygen (about 75 per cent).

The two largest veins in the body are the superior vena cava — which carries blood from the upper body directly to the right atrium of the heart — and the inferior vena cava, which carries blood from the lower body directly to the right atrium (shown in Figure 14.4.5). Like arteries, veins form a complex, branching system of larger and smaller vessels. The smallest veins are called venules. They receive blood from capillaries and transport it to larger veins. Each venule receives blood from multiple capillaries. See the major veins of the human body in Figure 14.4.6.

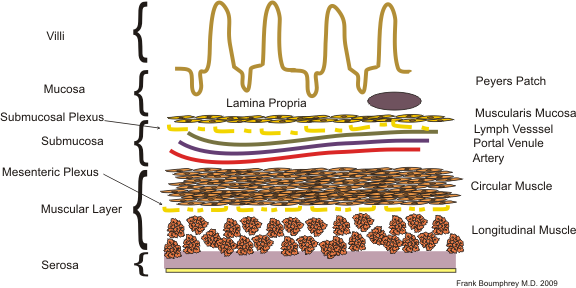

Capillaries

Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels in the cardiovascular system. They are so small that only one red blood cell at a time can squeeze through a capillary, and then only if the red blood cell deforms. Capillaries connect arterioles and venules, as shown in Figure 14.4.7. Capillaries generally form a branching network of vessels, called a capillary bed, that provides a large surface area for the exchange of substances between the blood and surrounding tissues.

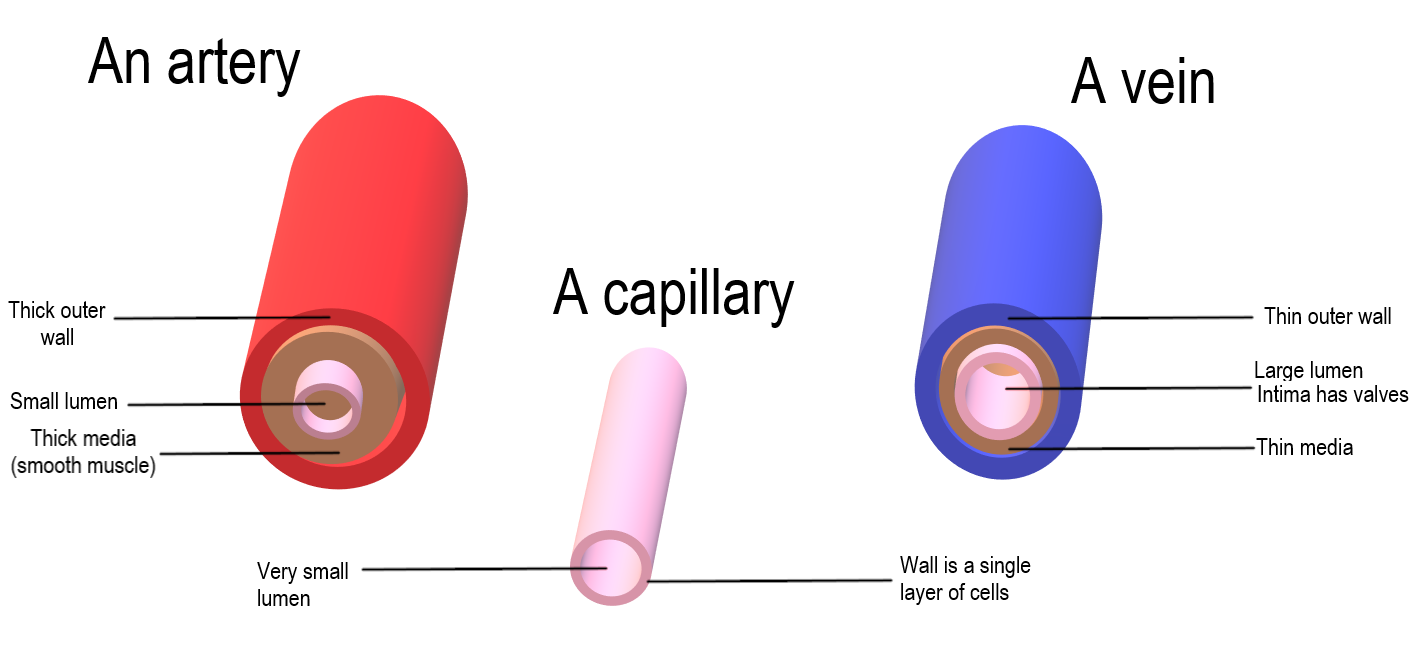

Structure of Blood Vessels

All blood vessels are basically hollow tubes with an internal space, called a lumen, through which blood flows. The lumen of an artery is shown in cross section in the photomicrograph (Figure 14.4.8). The width of blood vessels varies, but they all have a lumen. The walls of blood vessels differ depending on the type of vessel. In general, arteries and veins are more similar to one another than to capillaries in the structure of their walls.

Walls of Arteries and Veins

The walls of both arteries and veins have three layers: the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. You can see the three layers for an artery in the Figure 14.4.9.

- The tunica intima is the inner layer of arteries and veins. It is also the thinnest layer, consisting of a single layer of endothelial cells surrounded by a thin layer of connective tissues. It reduces friction between the blood and the inside of the blood vessel walls.

- The tunica media is the middle layer of arteries and veins. In arteries, this is the thickest layer. It consists mainly of elastic fibres and connective tissues. In arteries, this is the thickest layer, because it also contains smooth muscle tissues, which control the diameter of the vessels- as such, the width of the tunic media can be helpful in distinguishing arteries from veins.

- The tunica externa (also called tunica adventitia) is the outer layer of arteries and veins. It consists of connective tissue, and also contains nerves. In veins, this is the thickest layer. In general, the tunica externa protects and strengthens vessels, and attaches them to surrounding structures.

Capillary Walls

The walls of capillaries consist of little more than a single layer of epithelial cells. Being just one cell thick, the walls are well-suited for the exchange of substances between the blood inside them and the cells of surrounding tissues. Substances including water, oxygen, glucose, and other nutrients, as well as waste products (such as carbon dioxide), can pass quickly and easily through the extremely thin walls of capillaries. See figure 14.4.9 for a comparison of the structure of arteries, veins and capillaries.

Blood Pressure

The blood in arteries is normally under pressure because of the beating of the heart. The pressure is highest when the heart contracts and pumps out blood, and lowest when the heart relaxes and refills with blood. (You can feel this variation in pressure in your wrist or neck when you count your pulse.) Blood pressure is a measure of the force that blood exerts on the walls of arteries. It is generally measured in millimetres of mercury (mm Hg), and expressed as a double number — a higher number for systolic pressure when the ventricles contract, and a lower number for diastolic pressure when the ventricles relax. Normal blood pressure is generally defined as less than 120 mm Hg (systolic)/80 mm Hg (diastolic) when measured in the arm at the level of the heart. It decreases as blood flows farther away from the heart and into smaller arteries.

As arteries grow smaller, there is increasing resistance to blood flow through them, because of the blood's friction against the arterial walls. This resistance restricts blood flow so that less blood reaches smaller, downstream vessels, thus reducing blood pressure before the blood flows into the tiniest vessels, the capillaries. Without this reduction in blood pressure, capillaries would not be able to withstand the pressure of the blood without bursting. By the time blood flows through the veins, it is under very little pressure. The pressure of blood against the walls of veins is always about the same — normally no more than 10 mm Hg.

Vasoconstriction and Vasodilation

Smooth muscles in the walls of arteries can contract or relax to cause vasoconstriction (narrowing of the lumen of blood vessels) or vasodilation (widening of the lumen of blood vessels). This allows the arteries — especially the arterioles — to contract or relax as needed to help regulate blood pressure. In this regard, the arterioles act like an adjustable nozzle on a garden hose. When they narrow, the increased friction with the arterial walls causes less blood to flow downstream from the narrowing, resulting in a drop in blood pressure. These actions are controlled by the autonomic nervous system in response to pressure-sensitive sensory receptors in the walls of larger arteries.

Arteries can also dilate or constrict to help regulate body temperature, by allowing more or less blood to flow from the warm body core to the body’s surface. In addition, vasoconstriction and vasodilation play roles in the fight-or-flight response, under control of the sympathetic nervous system. Vasodilation allows more blood to flow to skeletal muscles, and vasoconstriction reduces blood flow to digestive organs.

Feature: My Human Body

The lumpy appearance of this man’s leg (Figure 14.4.10) is caused by varicose veins. Do you have varicose veins? If you do, you may wonder whether they are a sign of a significant health problem. You may also wonder whether you should have them treated, and if so, what treatments are available. As is usually the case, when it comes to your health, knowledge is power.

Varicose veins are veins that have become enlarged and twisted, because their valves have become ineffective (see Figure 14.4.11). As a result, blood pools in the veins and stretches them out. Varicose veins occur most frequently in the superficial veins of the legs, but they may also occur in other parts of the body. They are most common in older adults, females, and people who have a family history of the condition. Obesity and pregnancy also increase the risk of developing varicose veins. A job that requires standing for long periods of time, chronic constipation, and long-term alcohol consumption are additional risk factors.

Varicose veins usually are not serious. For many people, they are only a cosmetic issue. In severe cases, however, varicose veins may cause pain and other problems. The affected leg(s) may feel heavy and achy, especially after long periods of standing. Ankles may become swollen by the end of the day. Minor injuries may bleed more than normal. The skin over the varicosity may become red, dry, and itchy. In very severe cases, skin ulcers may develop.

If you are concerned about varicose veins, call them to the attention of your doctor, who can determine the best course of action for your case. There are many potential treatments for varicose veins. Some of the treatments have potential adverse side effects, and with many of the treatments, varicose veins may return. The best treatment for a given patient depends in part on the severity of the condition.

- If varicose veins are not serious, conservative treatment options may be recommended. These include avoiding standing or sitting for long periods, frequently elevating the legs, and wearing graduated compression stockings.

- For more serious cases, less conservative, but non-surgical options may be advised. These include sclerotherapy, in which medicine is injected into the veins to make them shrink. Another non-surgical approach is endovenous thermal ablation. In this type of treatment, laser light, radio-frequency energy, or steam is used to heat the walls of the veins, causing them to shrink and collapse.

- For the most serious cases, surgery may be the best option. The most invasive surgery is vein stripping, in which all or part of the main trunk of a vein is tied off and removed from the leg while the patient is under general anesthesia. In a less invasive surgery, called ambulatory phlebectomy, short segments of a vein are removed through tiny incisions under local anesthesia.

14.4 Summary

- Blood vessels are the part of the cardiovascular system that carries blood throughout the human body. They are long, hollow,tube-like structures. There are three major types of blood vessels: arteries, veins, and capillaries.

- Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart. Most arteries carry oxygenated blood. The largest artery is the aorta, which is connected to the heart and extends into the abdomen. Blood moves through arteries due to pressure from the beating of the heart.

- Veins are blood vessels that carry blood toward the heart. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood. The largest veins are the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava. Blood moves through veins by the squeezing action of surrounding skeletal muscles. Valves in veins prevent backflow of blood.

- Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels. They connect arterioles and venules. They form capillary beds, where substances are exchanged between the blood and surrounding tissues.

- The walls of arteries and veins have three layers. The middle layer is thickest in arteries, in which it contains smooth muscle tissue that controls the diameter of the vessels. The outer layer is thickest in veins, and consists mainly of connective tissue. The walls of capillaries consist of little more than a single layer of epithelial cells.

- Blood pressure is a measure of the force that blood exerts on the walls of arteries. It is expressed as a double number, with the higher number representing systolic pressure when the ventricles contract, and the lower number representing diastolic pressure when the ventricles relax. Normal blood pressure is generally defined as a pressure of less than 120/80 mm Hg.

- Vasoconstriction (narrowing) and vasodilation (widening) of arteries can occur to help regulate blood pressure or body temperature, or change blood flow as part of the fight-or-flight response.

14.4 Review Questions

- What are blood vessels? Name the three major types of blood vessels.

-

- Compare and contrast how blood moves through arteries and veins.

- What are capillaries, and what is their function?

- Does the blood in most veins have any oxygen at all? Explain your answer.

- Explain why it is important that the walls of capillaries are very thin.

14.4 Explore More

https://youtu.be/Ab9OZsDECZw

How blood pressure works - Wilfred Manzano, TED-Ed, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Wf8bLXVwFI

What are Varicose Veins? Cleveland Clinic, 2019.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hnjMdXSyA5o

Arteries vs Veins ( Circulatory System ), MooMooMath and Science, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 14.4.1

bodybuilding_PNG24 from pngimg.com is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) license.

Figure 14.4.2

Arterial_System_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 14.4.3

Skeletal_Muscle_Vein_Pump by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.4.4

Venous_valve_00013 by Nevit Dilmen on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 14.4.5

Superior and Inferior Vena Cava by ArtFavor (acquired from OCAL) from Freestockphotos.biz, is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/). Work adapted by Christine Miller.

Figure 14.4.6

Venous_system_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 14.4.7

1024px-2105_Capillary_Bed by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.4.8

Artery by Lord of Konrad on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

Figure 14.4.9

Blausen_0055_ArteryWallStructure by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.4.10

Artery Vein Capillary Comparison by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 14.4.11

Varicose-veins by Jackerhack at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5) license.

Figure 14.4.12

Varicose_veins-en.svg by Jmarchn on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. [Work modified from Varicose veins.jpg on Wikimedia Commons from National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH)]

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 20.6 Capillary bed [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 20.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/20-1-structure-and-function-of-blood-vessels

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 20.15 Skeletal muscle pump [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 20.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/20-2-blood-flow-blood-pressure-and-resistance

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Cleveland Clinic. (2019, December 30). What are varicose veins? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Wf8bLXVwFI&feature=youtu.be

MooMooMath and Science. (2018, April 5). Arteries vs veins ( Circulatory System ). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hnjMdXSyA5o&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2015, July 23). How blood pressure works - Wilfred Manzano. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ab9OZsDECZw&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Vampires

From Bram Stoker’s famous novel about Count Dracula, to films such as Van Helsing and the Twilight Saga, fantasies featuring vampires (like the one in Figure 14.5.1) have been popular for decades. Vampires, in fact, are found in centuries-old myths from many cultures. In such myths, vampires are generally described as creatures that drink blood — preferably of the human variety — for sustenance. Dracula, for example, is based on Eastern European folklore about a human who attains immortality (and eternal damnation) by drinking the blood of others.

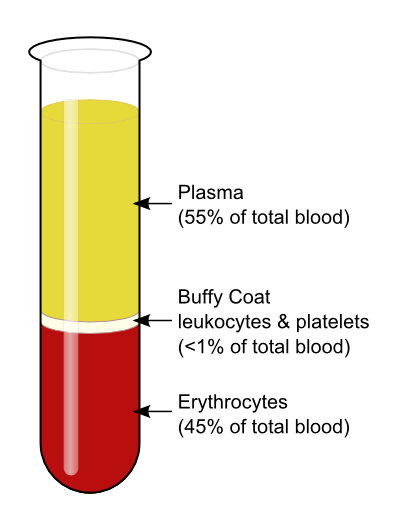

What Is Blood?

The average adult body contains between 4.7 and 5.7 litres of blood. More than half of that amount is fluid. Most of the rest of that amount consists of blood cells. The relative amounts of the various components in blood are illustrated in Figure 14.5.2. The components are also described in detail below.

Blood is a fluid connective tissue that circulates throughout the body through blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. What makes blood so special that it features in widespread myths? Although blood accounts for less than 10% of human body weight, it is quite literally the elixir of life. As blood travels through the vessels of the cardiovascular system, it delivers vital substances (such as nutrients and oxygen) to all of the cells, and carries away their metabolic wastes. It is no exaggeration to say that without blood, cells could not survive. Indeed, without the oxygen carried in blood, cells of the brain start to die within a matter of minutes.

Functions of Blood

Blood performs many important functions in the body. Major functions of blood include:

- Supplying tissues with oxygen, which is needed by all cells for aerobic cellular respiration.

- Supplying cells with nutrients, including glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids.

- Removing metabolic wastes from cells, including carbon dioxide, urea, and lactic acid.

- Helping to defend the body from pathogens and other foreign substances.

- Forming clots to seal broken blood vessels and stop bleeding.

- Transporting hormones and other messenger molecules.

- Regulating the pH of the body, which must be kept within a narrow range (7.35 to 7.45).

- Helping regulate body temperature (through vasoconstriction and vasodilation).

Blood Plasma

Plasma is the liquid component of human blood. It makes up about 55% of blood by volume. It is about 92% water, and contains many dissolved substances. Most of these substances are proteins, but plasma also contains trace amounts of glucose, mineral ions, hormones, carbon dioxide, and other substances. In addition, plasma contains blood cells. When the cells are removed from plasma, as in Figure 14.5.2 above, the remaining liquid is clear but yellow in colour.

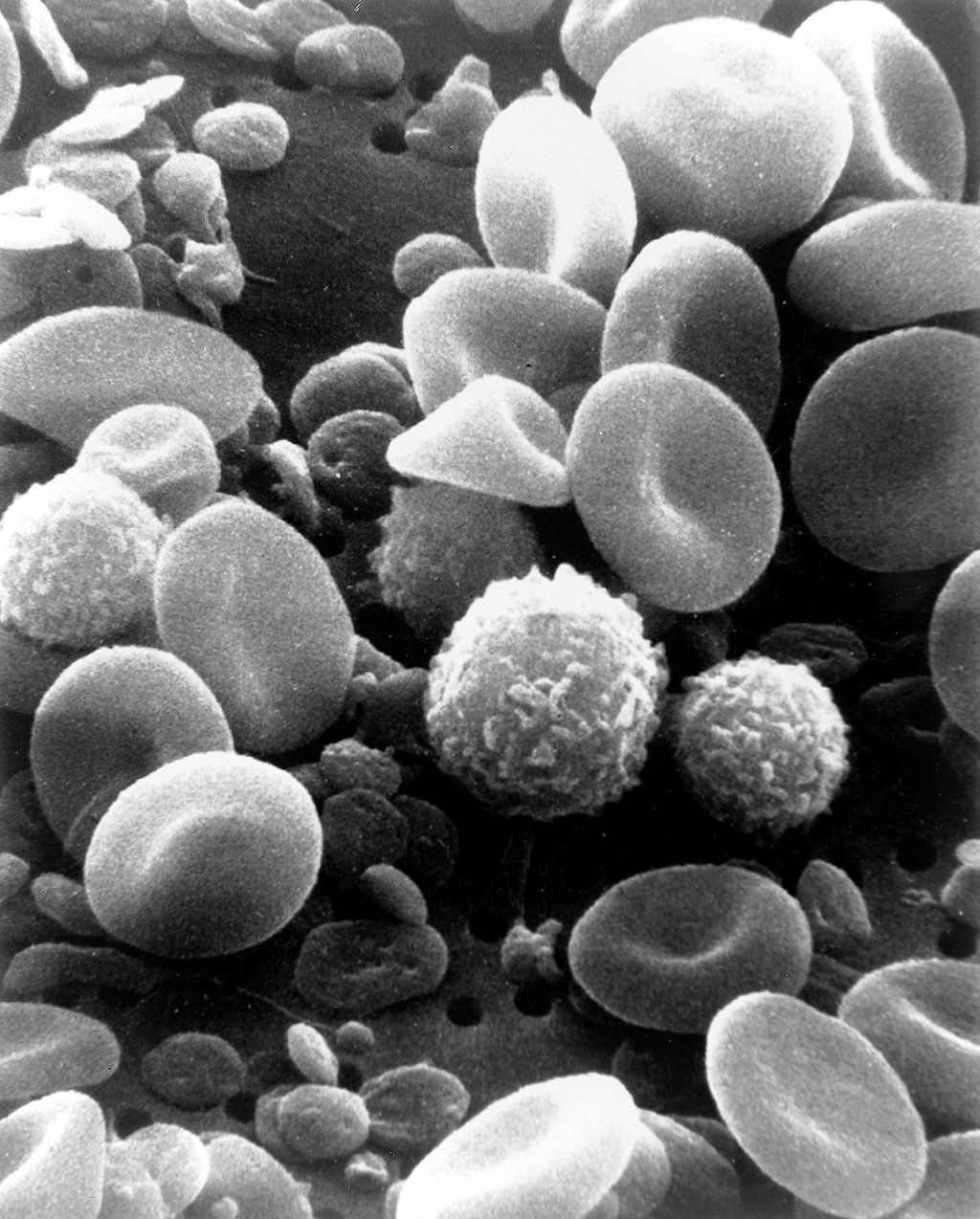

Blood Cells

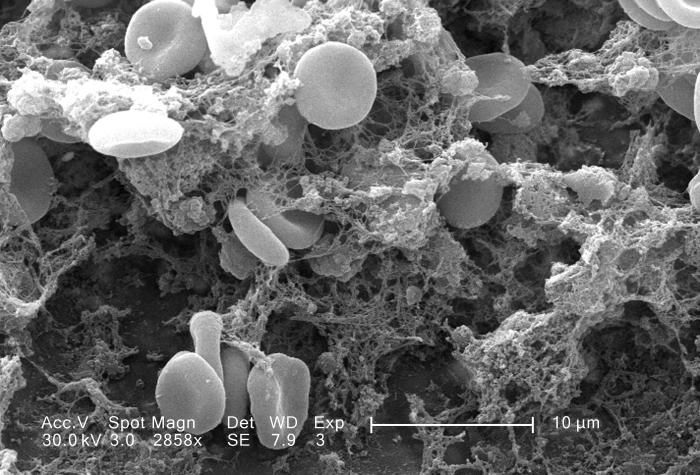

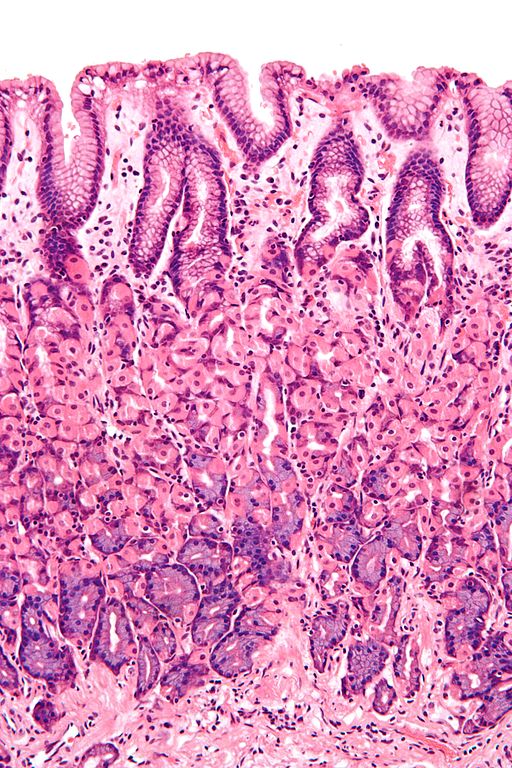

The cells in blood include erythrocytes, leukocytes, and thrombocytes. These different types of blood cells are shown in the photomicrograph (Figure 14.5.3) and described in the sections that follow.

Erythrocytes

The most numerous cells in blood are red blood cells, also called erythrocytes. One microlitre of blood contains between 4.2 and 6.1 million red blood cells, and red blood cells make up about 25% of all the cells in the human body. The cytoplasm of a mature erythrocyte is almost completely filled with hemoglobin, the iron-containing protein that binds with oxygen and gives the cell its red colour. In order to provide maximum space for hemoglobin, mature erythrocytes lack a cell nucleus and most organelles. They are little more than sacks of hemoglobin.

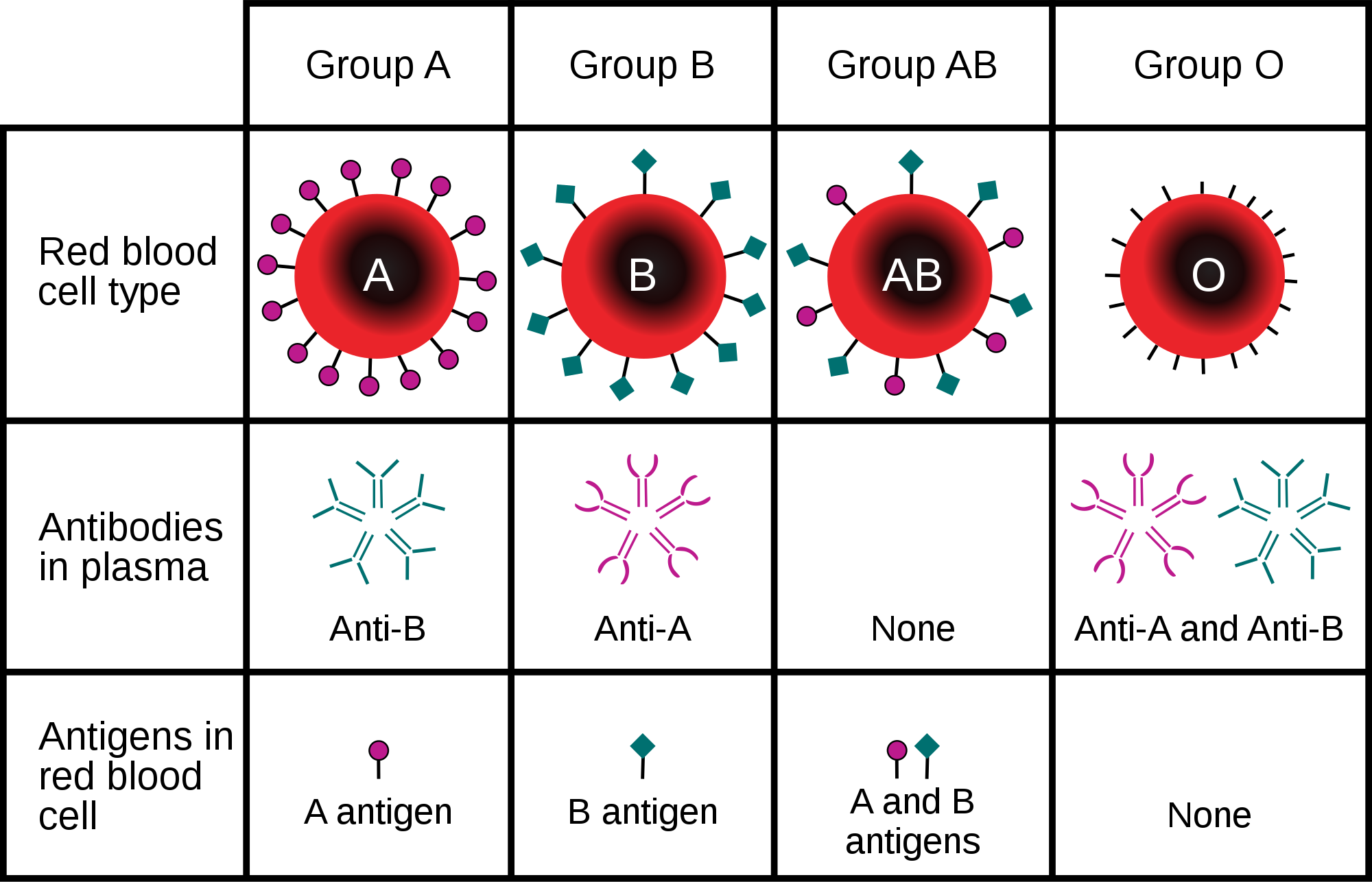

Erythrocytes also carry proteins called antigens that determine blood type. Blood type is a genetic characteristic. The best known human blood type systems are the ABO and Rhesus systems.

- In the ABO system, there are two common antigens, called antigen A and antigen B. There are four ABO blood types, A (only A antigen), B (only B antigen), AB (both A and B antigens), and O (neither A nor B antigen). The ABO antigens are illustrated in Figure 14.5.4.

- In the Rhesus system, there is just one common antigen. A person may either have the antigen (Rh+) or lack the antigen (Rh-).

Blood type is important for medical reasons. A person who needs a blood transfusion must receive blood of a compatible type. Blood that is compatible lacks antigens that the patient's own blood also lacks. For example, for a person with type A blood (no B antigen), compatible types include any type of blood that lacks the B antigen. This would include type A blood or type O blood, but not type AB or type B blood. If incompatible blood is transfused, it may cause a potentially life-threatening reaction in the patient’s blood.

Leukocytes

Leukocytes (also called white blood cells) are cells in blood that defend the body against invading microorganisms and other threats. There are far fewer leukocytes than red blood cells in blood. There are normally only about 1,000 to 11,000 white blood cells per microlitre of blood. Unlike erythrocytes, leukocytes have a nucleus. White blood cells are part of the body’s immune system. They destroy and remove old or abnormal cells and cellular debris, as well as attack pathogens and foreign substances. There are five main types of white blood cells, which are described in Table 14.5.1: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. The five types differ in their specific immune functions.

| Type of Leukocyte | Per cent of All Leukocytes | Main Function(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil | 62% | Phagocytize (engulf and destroy) bacteria and fungi in blood. |

| Eosinophil | 2% | Attack and kill large parasites; carry out allergic responses. |

| Basophil | less than 1% | Release histamines in inflammatory responses. |

| Lymphocyte | 30% | Attack and destroy virus-infected and tumor cells; create lasting immunity to specific pathogens. |

| Monocyte | 5% | Phagocytize pathogens and debris in tissues. |

Thrombocytes

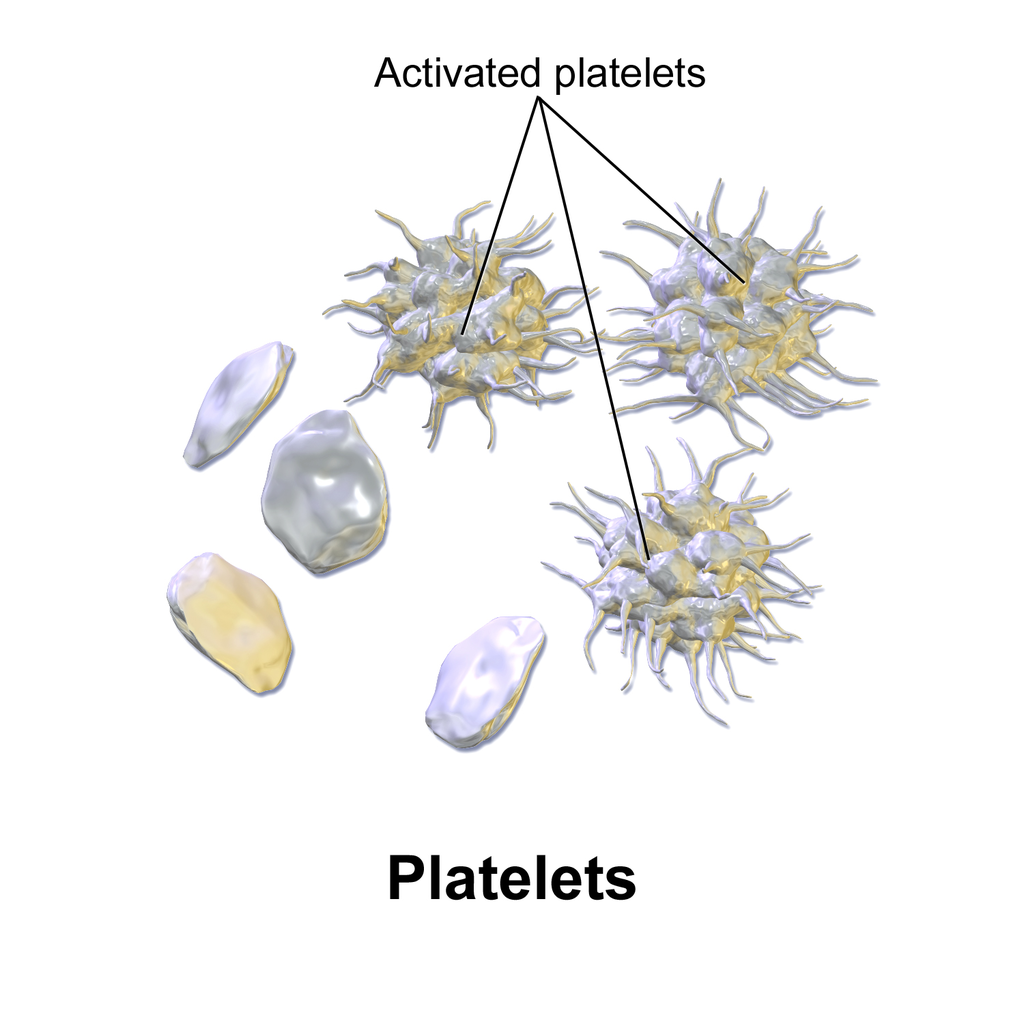

Thrombocytes, also called platelets, are actually cell fragments. Like erythrocytes, they lack a nucleus and are more numerous than white blood cells. There are about 150 thousand to 400 thousand thrombocytes per microlitre of blood.

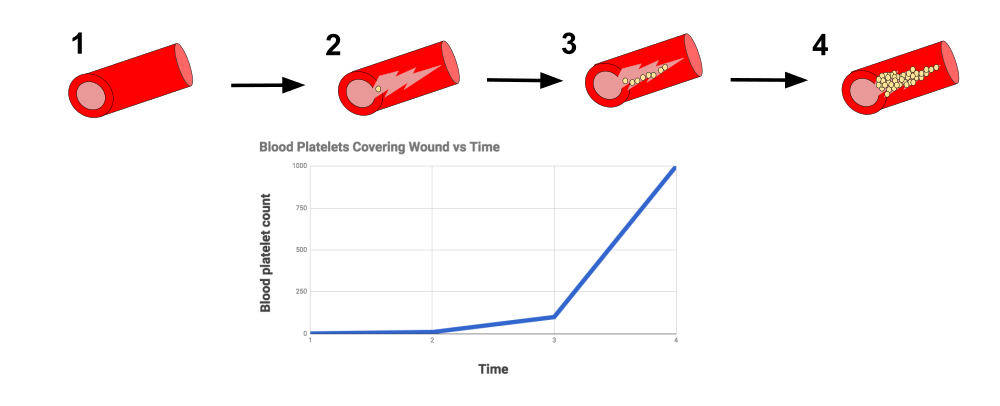

The main function of thrombocytes is blood clotting, or coagulation. This is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a plug in a damaged blood vessel. If blood clotting is successful, it results in hemostasis, which is the cessation of blood loss from the damaged vessel. A blood clot consists of both platelets and proteins, especially the protein fibrin. You can see a scanning electron microscope photomicrograph of a blood clot in Figure 14.5.5.

Coagulation begins almost instantly after an injury occurs to the endothelium of a blood vessel. Thrombocytes become activated and change their shape from spherical to star-shaped, as shown in Figure 14.5.6. This helps them aggregate with one another (stick together) at the site of injury to start forming a plug in the vessel wall. Activated thrombocytes also release substances into the blood that activate additional thrombocytes and start a sequence of reactions leading to fibrin formation. Strands of fibrin crisscross the platelet plug and strengthen it, much as rebar strengthens concrete.

Formation and Degradation of Blood Cells

Blood is considered a connective tissue, because blood cells form inside bones. All three types of blood cells are made in red marrow within the medullary cavity of bones in a process called hematopoiesis. Formation of blood cells occurs by the proliferation of stem cells in the marrow. These stem cells are self-renewing — when they divide, some of the daughter cells remain stem cells, so the pool of stem cells is not used up. Other daughter cells follow various pathways to differentiate into the variety of blood cell types. Once the cells have differentiated, they cannot divide to form copies of themselves.

Eventually, blood cells die and must be replaced through the formation of new blood cells from proliferating stem cells. After blood cells die, the dead cells are phagocytized (engulfed and destroyed) by white blood cells, and removed from the circulation. This process most often takes place in the spleen and liver.

Blood Disorders

Many human disorders primarily affect the blood. They include cancers, genetic disorders, poisoning by toxins, infections, and nutritional deficiencies.

- Leukemia is a group of cancers of the blood-forming tissues in the bone marrow. It is the most common type of cancer in children, although most cases occur in adults. Leukemia is generally characterized by large numbers of abnormal leukocytes. Symptoms may include excessive bleeding and bruising, fatigue, fever, and an increased risk of infections. Leukemia is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- Hemophilia refers to any of several genetic disorders that cause dysfunction in the blood clotting process. People with hemophilia are prone to potentially uncontrollable bleeding, even with otherwise inconsequential injuries. They also commonly suffer bleeding into the spaces between joints, which can cause crippling.

- Carbon monoxide poisoning occurs when inhaled carbon monoxide (in fumes from a faulty home furnace or car exhaust, for example) binds irreversibly to the hemoglobin in erythrocytes. As a result, oxygen cannot bind to the red blood cells for transport throughout the body, and this can quickly lead to suffocation. Carbon monoxide is extremely dangerous, because it is colourless and odorless, so it cannot be detected in the air by human senses.

- HIV is a virus that infects certain types of leukocytes and interferes with the body’s ability to defend itself from pathogens and other causes of illness. HIV infection may eventually lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). AIDS is characterized by rare infections and cancers that people with a healthy immune system almost never acquire.

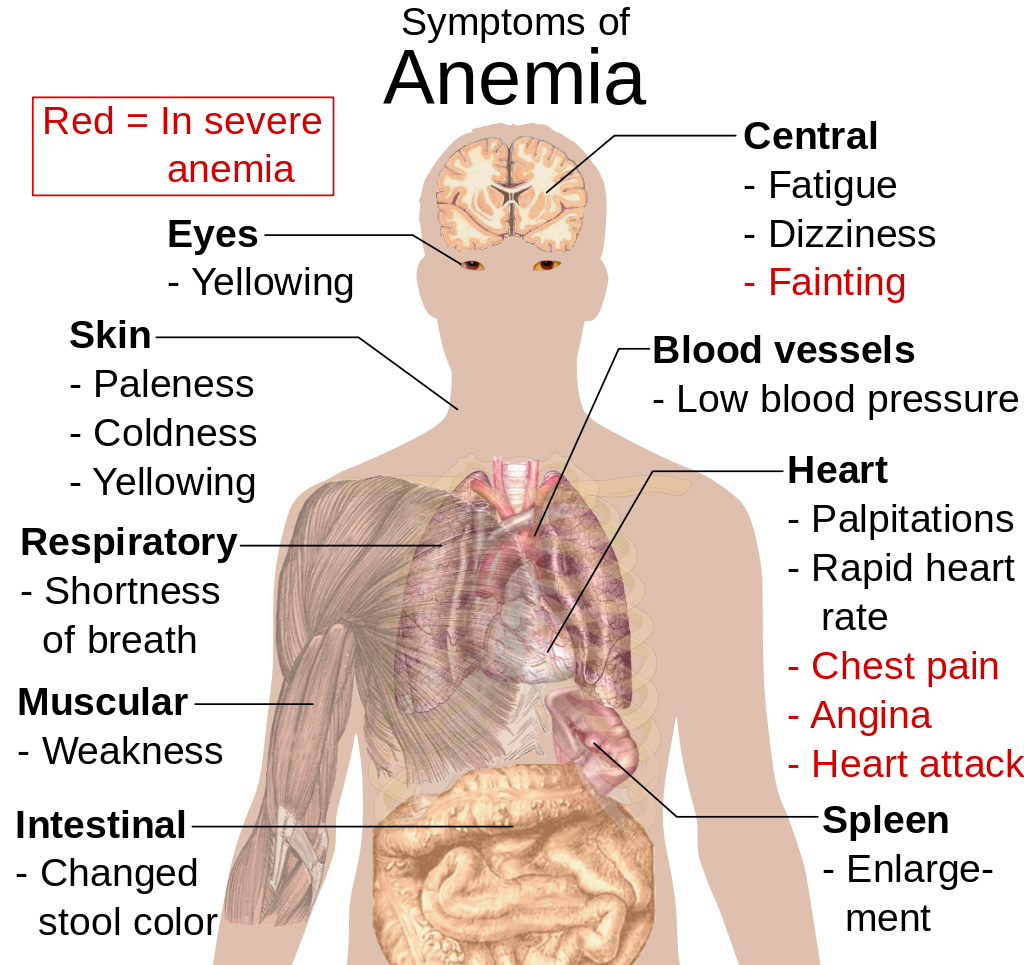

- Anemia is a disorder in which the blood has an inadequate volume of erythrocytes, reducing the amount of oxygen that the blood can carry, and potentially causing weakness and fatigue. These and other signs and symptoms of anemia are shown in Figure 14.5.8. Anemia has many possible causes, including excessive bleeding, inherited disorders (such as sickle cell hemoglobin), or nutritional deficiencies (iron, folate, or B12). Severe anemia may require transfusions of donated blood.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Donating blood saves lives. In fact, with each blood donation, as many as three lives may be saved. According to Government Canada, up to 52% of Canadians have reported that they or a family member have needed blood or blood products at some point in their lifetime. Many donors agree that the feeling that comes from knowing you have saved lives is well worth the short amount of time it takes to make a blood donation. Nonetheless, only a minority of potential donors actually donate blood. There are many myths about blood donation that may help explain the small percentage of donors. Knowing the facts may reaffirm your decision to donate if you are already a donor — and if you aren’t a donor already, getting the facts may help you decide to become one.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| "Your blood might become contaminated with an infection during the donation." | There is no risk of contamination because only single-use, disposable catheters, tubing, and other equipment are used to collect blood for a donation. |

| "You are too old (or too young) to donate blood." | There is no upper age limit on donating blood, as long as you are healthy. The minimum age is 16 years. |

| "You can’t donate blood if you have high blood pressure." | As long as your blood pressure is below 180/100 at the time of donation, you can give blood. Even if you take blood pressure medication to keep your blood pressure below this level, you can donate. |

| "You can’t give blood if you have high cholesterol." | Having high cholesterol does not affect your ability to donate blood. Taking cholesterol-lowering medication also does not disqualify you. |

| "You can’t donate blood if you have had a flu shot." | Having a flu shot has no effect on your ability to donate blood. You can even donate on the same day that you receive a flu shot. |

| "You can’t donate blood if you take medication." | As long as you are healthy, in most cases, taking medication does not preclude you from donating blood. |

| "Your blood isn’t needed if it’s a common blood type." | All types of blood are in constant demand. |

14.5 Summary

- Blood is a fluid connective tissue that circulates throughout the body in the cardiovascular system. Blood supplies tissues with oxygen and nutrients and removes their metabolic wastes. Blood helps defend the body from pathogens and other threats, transports hormones and other substances, and helps keep the body’s pH and temperature in homeostasis.

- Plasma is the liquid component of blood, and it makes up more than half of blood by volume. It consists of water and many dissolved substances. It also contains blood cells, including erythrocytes, leukocytes and thrombocytes.

- Erythrocytes, (also known as red blood cells) are the most numerous cells in blood. They consist mostly of hemoglobin, which carries oxygen. Erythrocytes also carry antigens that determine blood type.

- Leukocytes (also referred to as white blood cells) are less numerous than erythrocytes and are part of the body’s immune system. There are several different types of leukocytes that differ in their specific immune functions. They protect the body from abnormal cells, microorganisms, and other harmful substances.

- Thrombocytes (also called platelets) are cell fragments that play important roles in blood clotting, or coagulation. They stick together at breaks in blood vessels to form a clot and stimulate the production of fibrin, which strengthens the clot.

- All blood cells form by proliferation of stem cells in red bone marrow in a process called hematopoiesis. When blood cells die, they are phagocytized by leukocytes and removed from the circulation.

- Disorders of the blood include leukemia, which is cancer of the bone-forming cells; hemophilia, which is any of several genetic blood-clotting disorders; carbon monoxide poisoning, which prevents erythrocytes from binding with oxygen and causes suffocation; HIV infection, which destroys certain types of leukocytes and can cause AIDS; and anemia, in which there are not enough erythrocytes to carry adequate oxygen to body tissues.

14.5 Review Questions

- What is blood? Why is blood considered a connective tissue?

- Identify four physiological roles of blood in the body.

- Describe plasma and its components.

-

14.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/e-5wqwp64MM

Joe Landolina: This gel can make you stop bleeding instantly, TED, 2014.

https://youtu.be/hgp8LtwFSBA

Can Synthetic Blood Help The World's Blood Shortage? Science Plus, 2016.

https://youtu.be/1Qfmkd6C8u8

How bones make blood - Melody Smith, TED-Ed, 2020.

Attributions

Figure 14.5.1

vampire_PNG32 from pngimg.com is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) license.

Figure 14.5.2

Blood-centrifugation-scheme by KnuteKnudsen at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.5.3

SEM_blood_cells by Bruce Wetzel and Harry Schaefer (Photographers)/ NCI AV-8202-3656 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Public_domain).

Figure 14.5.4

ABO_blood_type.svg by InvictaHOG on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Public_domain).

Figure 14.5.5

Blood_clot_in_scanning_electron_microscopy by Janice Carr from CDC/ Public Health Image LIbrary (PHIL) ID #7308 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Public_domain).

Figure 14.5.6

Blausen_0740_Platelets by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.5.7

Platelet_Party_900x by Awkward Yeti (used with permission of the author) © All Rights Reserved

Figure 14.5.8

Symptoms_of_anemia.svg by Mikael Häggström on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain).

References

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Blood, organ and tissue donation. (2020, April 28). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/healthy-living/blood-organ-tissue-donation.html#a3

Canadian Blood Services. (n.d.). There is an immediate need for blood as demand is rising. https://www.blood.ca

Science Plus. (2016, March 2). Can synthetic blood help the world's blood shortage? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hgp8LtwFSBA&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2014, November 20). Joe Landolina: This gel can make you stop bleeding instantly. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-5wqwp64MM&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, January 27). How bones make blood - Melody Smith. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Qfmkd6C8u8&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Worm Attack!

Does the organism in Figure 17.2.1 look like a space alien? A scary creature from a nightmare? In fact, it’s a 1-cm long worm in the genus Schistosoma. It may invade and take up residence in the human body, causing a very serious illness known as schistosomiasis. The worm gains access to the human body while it is in a microscopic life stage. It enters through a hair follicle when the skin comes into contact with contaminated water. The worm then grows and matures inside the human organism, causing disease.

Host vs. Pathogen

The Schistosoma worm has a parasitic relationship with humans. In this type of relationship, one organism, called the parasite, lives on or in another organism, called the host. The parasite always benefits from the relationship, and the host is always harmed. The human host of the Schistosoma worm is clearly harmed by the parasite when it invades the host’s tissues. The urinary tract or intestines may be infected, and signs and symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, or blood in the urine. Those who have been infected for a long time may experience liver damage, kidney failure, infertility, or bladder cancer. In children, Schistosoma infection may cause poor growth and difficulty learning.

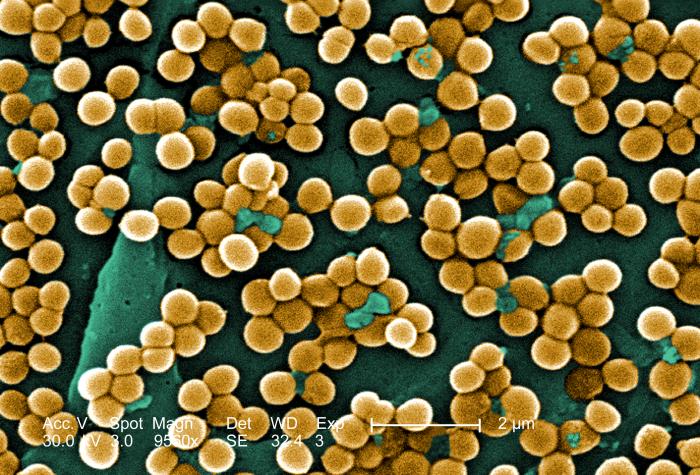

Like the Schistosoma worm, many other organisms can make us sick if they manage to enter our body. Any such agent that can cause disease is called a pathogen. Most pathogens are microorganisms, although some — such as the Schistosoma worm — are much larger. In addition to worms, common types of pathogens of human hosts include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and single-celled organisms called protists. You can see examples of each of these types of pathogens in Table 17.1.1. Fortunately for us, our immune system is able to keep most potential pathogens out of the body, or quickly destroy them if they do manage to get in. When you read this chapter, you’ll learn how your immune system usually keeps you safe from harm — including from scary creatures like the Schistosoma worm!

| Type of Pathogen | Description | Disease Caused | |

|---|---|---|---|

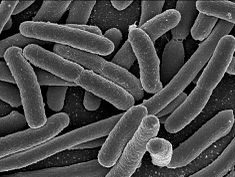

| Bacteria:

Example shown: Escherichia coli |

|

Single celled organisms without a nucleus | Strep throat, staph infections, tuberculosis, food poisoning, tetanus, pneumonia, syphillis |

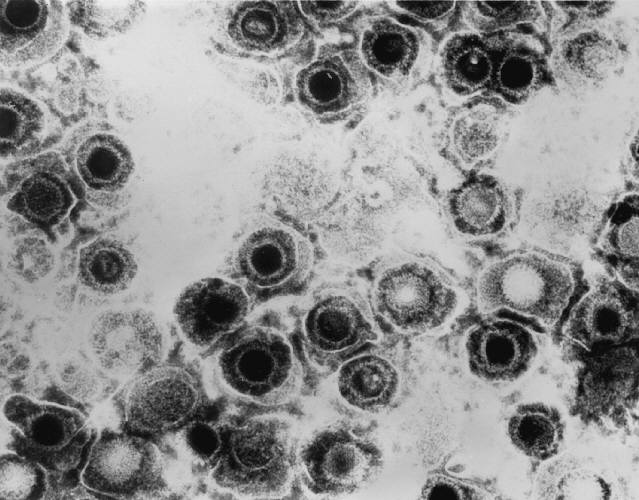

| Viruses:

Example shown: Herpes simplex |

|

Non-living particles that reproduce by taking over living cells | Common cold, flu, genital herpes, cold sores, measles, AIDS, genital warts, chicken pox, small pox |

| Fungi:

Example shown: Death cap mushroom |

|

Simple organisms, including mushrooms and yeast, that grow as single cells or thread-like filaments | Ringworm, athletes foot, tineas, candidias, histoplasmomis, mushroom poisoning |

| Protozoa:

Example shown: Giardia lamblia |

|

Single celled organisms with a nucleus | Malaria, "traveller's diarrhea", giardiasis, typano somiasis ("sleeping sickness") |

What is the Immune System?

The immune system is a host defense system. It comprises many biological structures —ranging from individual leukocytes to entire organs — as well as many complex biological processes. The function of the immune system is to protect the host from pathogens and other causes of disease, such as tumor (cancer) cells. To function properly, the immune system must be able to detect a wide variety of pathogens. It also must be able to distinguish the cells of pathogens from the host’s own cells, and also to distinguish cancerous or damaged host cells from healthy cells. In humans and most other vertebrates, the immune system consists of layered defenses that have increasing specificity for particular pathogens or tumor cells. The layered defenses of the human immune system are usually classified into two subsystems, called the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system.

Innate Immune System

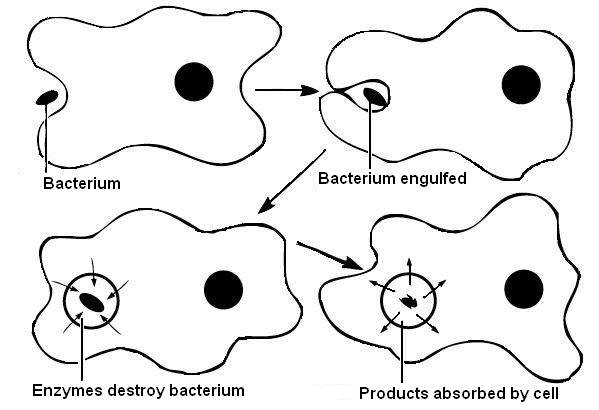

The innate immune system (sometimes referred to as "non-specific defense") provides very quick, but non-specific responses to pathogens. It responds the same way regardless of the type of pathogen that is attacking the host. It includes barriers — such as the skin and mucous membranes — that normally keep pathogens out of the body. It also includes general responses to pathogens that manage to breach these barriers, including chemicals and cells that attack the pathogens inside the human host. Certain leukocytes (white blood cells), for example, engulf and destroy pathogens they encounter in the process called phagocytosis, which is illustrated in Figure 17.2.2. Exposure to pathogens leads to an immediate maximal response from the innate immune system.

Watch the video below, "Neutrophil Phagocytosis - White Blood Cells Eats Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteria" by ImmiflexImmuneSystem, to see phagocytosis in action.

https://youtu.be/Z_mXDvZQ6dU

Neutrophil Phagocytosis - White Blood Cell Eats Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteria, ImmiflexImmuneSystem, 2013.

Adaptive Immune System

The adaptive immune system is activated if pathogens successfully enter the body and manage to evade the general defenses of the innate immune system. An adaptive response is specific to the particular type of pathogen that has invaded the body, or to cancerous cells. It takes longer to launch a specific attack, but once it is underway, its specificity makes it very effective. An adaptive response also usually leads to immunity. This is a state of resistance to a specific pathogen, due to the adaptive immune system's ability to “remember” the pathogen and immediately mount a strong attack tailored to that particular pathogen if it invades again in the future.

Self vs. Non-Self

Both innate and adaptive immune responses depend on the immune system's ability to distinguish between self- and non-self molecules. Self molecules are those components of an organism’s body that can be distinguished from foreign substances by the immune system. Virtually all body cells have surface proteins that are part of a complex called major histocompatibility complex (MHC). These proteins are one way the immune system recognizes body cells as self. Non-self proteins, in contrast, are recognized as foreign, because they are different from self proteins.

Antigens and Antibodies

Many non-self molecules comprise a class of compounds called antigens. Antigens, which are usually proteins, bind to specific receptors on immune system cells and elicit an adaptive immune response. Some adaptive immune system cells (B cells) respond to foreign antigens by producing antibodies. An antibody is a molecule that precisely matches and binds to a specific antigen. This may target the antigen (and the pathogen displaying it) for destruction by other immune cells.

Antigens on the surface of pathogens are how the adaptive immune system recognizes specific pathogens. Antigen specificity allows for the generation of responses tailored to the specific pathogen. It is also how the adaptive immune system ”remembers” the same pathogen in the future.

Immune Surveillance

Another important role of the immune system is to identify and eliminate tumor cells. This is called immune surveillance. The transformed cells of tumors express antigens that are not found on normal body cells. The main response of the immune system to tumor cells is to destroy them. This is carried out primarily by aptly-named killer T cells of the adaptive immune system.

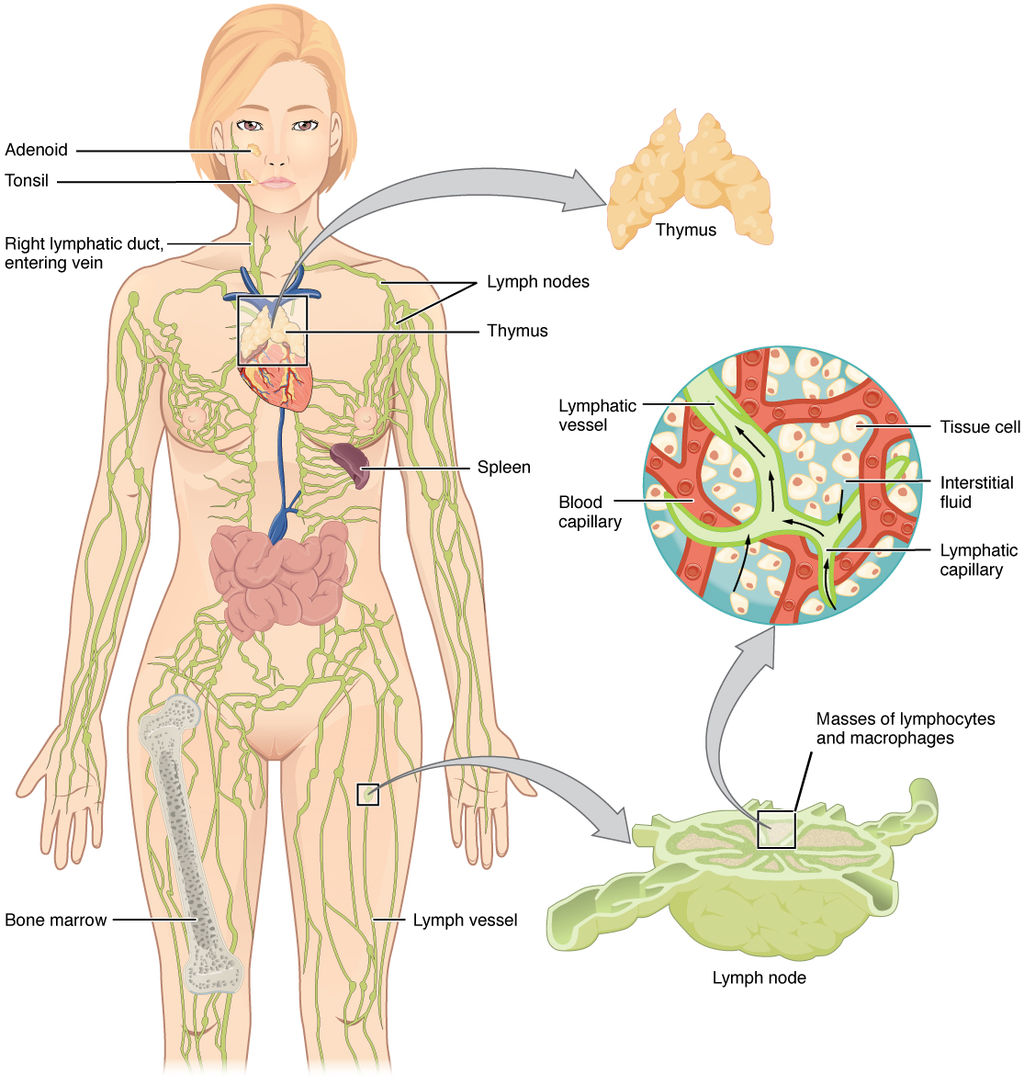

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is a human organ system that is a vital part of the adaptive immune system. It is also part of the cardiovascular system and plays a major role in the digestive system (see section 17.3 Lymphatic System). The major structures of the lymphatic system are shown in Figure 17.2.3 .

The lymphatic system consists of several lymphatic organs and a body-wide network of lymphatic vessels that transport the fluid called lymph. Lymph is essentially blood plasma that has leaked from capillaries into tissue spaces. It includes many leukocytes, especially lymphocytes, which are the major cells of the lymphatic system. Like other leukocytes, lymphocytes defend the body. There are several different types of lymphocytes that fight pathogens or cancer cells as part of the adaptive immune system.

Major lymphatic organs include the thymus and bone marrow. Their function is to form and/or mature lymphocytes. Other lymphatic organs include the spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes, which are small clumps of lymphoid tissue clustered along lymphatic vessels. These other lymphatic organs harbor mature lymphocytes and filter lymph. They are sites where pathogens collect, and adaptive immune responses generally begin.

Neuroimmune System vs. Peripheral Immune System