Chapter 8: The Early Twentieth Century

Russian Revolutions

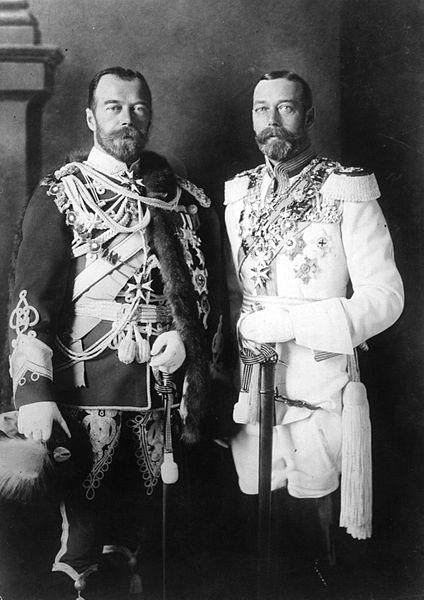

The last Tsar of Russia was Nikolai II (1868 – 1918). At the start of his reign in 1894, at the death of his father Alexander III, Nikolai was among the most powerful monarchs in Europe. Russia may have been technologically and socially backwards compared to the rest of Europe, but it commanded an enormous empire and boasted a powerful military. Alone among the monarchs of the great powers, the Tsars had successfully resisted most of the forces of modernity that had fundamentally changed the political structure of the rest of Europe. Nikolai ruled in much the same manner as had his father, grandfather, and great grandfather before him, holding nearly complete authority over day-to-day politics and the Russian Church.

It was, however, during his reign that modernity finally caught up with Russia. The Russian state was able to control the press and punish dissent into the first years of the twentieth century, but then events outside of its immediate control undermined its ability to exercise complete control over Russian society. The immediate cause of the downfall of Nikolai’s royal line, and the entire traditional order of Russian society, was war: The Russo – Japanese War of 1904 – 1905 and, ten years later, World War I.

Japan shocked the world when it handily defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War. To many Russians, the Tsar was to blame for the defeat in both allowing Russia to remain so far behind the rest of the industrialized world economically, and because he himself had proved an indecisive leader during the war. Following the Russian defeat, 100,000 workers tried to present a petition to the Tsar asking for better wages, better prices on food, and the end of official censorship. Troops fired on the crowds, which were unarmed, sparking a nationwide wave of strikes. For months, the nation was rocked by open rebellions in navy bases and cities, and radical terrorist groups managed to seize certain neighborhoods of the major metropolises of St. Petersburg and Moscow. Nikolai finally agreed to allow a representative assembly, the Duma, to meet, and after months of fighting the army managed to regain control.

The aftermath of this (semi-)revolution saw the Tsar still in power and various newly-constituted political parties elected to the Duma. Very soon, however, it was clear that the Duma was not going to serve as a counter-balance to Tsarist power. The Tsar retained control of foreign policy and military affairs. In addition, the parties in the Duma had no experience of actually governing, and quickly fell to infighting and petty squabbles, leaving most actual decision making where it always had been: with the Tsar himself and his circle of aristocratic advisors. Still, some things did change thanks to the revolution: unions were legalized and the Tsar was not able to completely dismiss the Duma. Most importantly, the state could no longer censor the press effectively. As a result, there was an explosion of anger as various forms of anti-governmental press spread across the country.

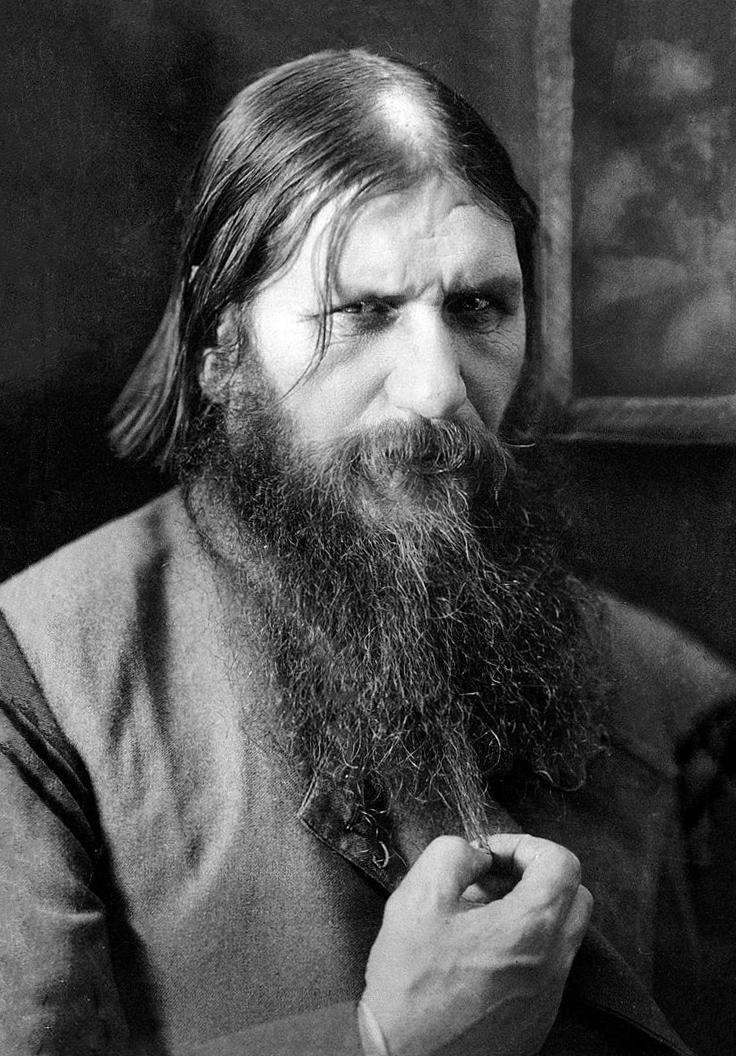

One of Nikolai’s many concerns was that his only male heir, Prince Alexei, was a hemophiliac (i.e. his blood did not clot properly when he was injured, meaning any minor scrape or cut was potentially lethal). Nikolai’s wife, Tsarina Alexandra, called upon the services of a wandering, illiterate monk and faith healer named Grigorii Rasputin. Rasputin, definitely one of the most peculiar characters in modern history, was somehow able (perhaps through a kind of hypnotism) to stop Alexei’s bleeding, and the Tsarina thus believed that he had been sent by God to protect the royal family. Rasputin moved in with the Tsar’s family and quickly became a powerful influence, despite being the son of Siberian peasants, and despite the fact that part of his philosophy was that one was closest to God after engaging in sexual orgies and other forms of debauchery.

When World War I began in 1914, the already fragile political balance within the Russian state teetered on the verge of collapse. In the autumn of 1915, as Russian fortunes in the war started to worsen, Nikolai departed for the front to personally command the Russian army. In 1916 a desperate conspiracy of Russian nobles, convinced that Rasputin was the cause of Russia’s problems, managed to assassinate him. By then, however, the German armies were steadily pressing towards Russian territory, and tens of thousands of Russian troops were deserting to return to their home villages. As the social and political situation began to approach outright anarchy, one group of Russian communists steeped in the tradition of radical terrorism stood ready to take action: the Bolsheviks.

The form of radical politics that had taken root in Russia in the late nineteenth century revolved around apocalyptic revolutionary socialism. Mikhail Bakunin was the exemplary figure in this regard – Bakunin believed that the only way to create a perfect socialist future was to utterly destroy the existing political and social order, after which “natural” human tendencies of peace and altruism would manifest and create a better society for all. By the late nineteenth century, this homegrown Russian version of socialist theory was joined with Marxism, as various Russian radical thinkers tried to determine how a Marxist revolution might occur in a society like theirs that was still largely feudal.

The problem with Marxist theory faced by Russian Marxists was that, according to Marx, a revolution could only happen in an advanced industrial society. The proletariat would recognize that it had “nothing to lose but its chains” and overthrow the bourgeois order. In Russia, however, industrialization was limited to some of the major cities of western Russia, and most of the population were still poor peasants in small villages. This did not look like a promising setting for a revolution of the industrial working class.

The key figure who saw a way out of this theoretical impasse was Vladimir Lenin. Lenin was an ardent revolutionary and a major political thinker. He created the concept of the “vanguard party”: a dedicated group of revolutionaries who would lead both workers and peasants in a massive uprising. Left to their own devices, he argued, workers alone would always settle for slight improvements in their lives and working conditions (he called this “trade union consciousness”) rather than recognizing the need for a full-scale revolutionary change. The vanguard party, however, could both instruct workers and lead them in the creation of a new society. Led by the party, not only could a communist revolution succeed in a backwards state like Russia, but it could “skip” a stage of (the Marxist version of) history, jumping directly from feudalism to socialism and bypassing industrial capitalism.

In Lenin’s mind, the obvious choice of a vanguard party was his own Russian communist party, the Bolsheviks. By 1917, the Bolsheviks were a highly organized militant group of revolutionaries with contacts in the army, navy, and working classes of the major cities. When political chaos descended on the country as the possibility of full-scale defeat to Germany loomed, the Bolsheviks had their chance to seize power.

On International Women’s Day in February of 1917 (using the Eastern Orthodox calendar still in use at the time – it was March in the west), women workers in St. Petersburg demonstrated against the Tsar’s government to protest the price of food, which had skyrocketed due to the war. Within days the demands had grown to ending the war entirely and even calling for the ouster of the Tsar himself, and a general strike was called. Comparable demonstrations broke out in the other major cities in short order. The key moment, as had happened in revolutions since 1789, was when the army refused to put down the uprisings and instead joined them. The Duma demanded that the Tsar step aside and hand over control of the military. By early March, just a few weeks after it had begun, the Tsar abdicated, realizing that he had lost the support of almost the entire population.

In the aftermath of this event, power was split. The Duma appointed a provisional government than enacted important legal reforms but did not have the power to relieve the Russian army at the front or to provide food to the hungry protesters. Likewise, the Duma itself represented the interests and beliefs of the educated middle classes, still only a tiny portion of the Russian population as a whole. The members of the Duma hoped to create a democratic republic like those of France, Britain, or the United States, but they had no road map to bring it about. Likewise, the Duma had no way to enforce the new laws it passed, nor could they compel Russian peasants to fight on against the Germans. Most critically, the members of the Duma refused to sue for peace with Germany, believing that Russia still had to honor its commitment to the war despite the carnage being inflicted on Russian soldiers at the front.

Soon, in the industrial centers and in many of the army and naval bases, councils of workers and soldiers (called soviets) sprang up and declared that they had the real right to political power. There was a standoff between the provisional government, which had no police force to enforce its will, and the soviets, which could control their own areas but did not have the ability to bring the majority of the population (who wanted, in Lenin’s words, “peace, land, and bread”) over to their side. Many fled the cities for the countryside, peasants seized land from landowners, and soldiers deserted in droves; by 1917 fully 75% of the soldiers sent to the front against Germany deserted.

Thus, as of the late summer of 1917, there was a power vacuum created by the war and by the incompetence of the Duma. No group had power over the country as a whole, and so the Bolsheviks had their opportunity. In October the Bolsheviks took control of the most powerful soviet, that of Petrograd (former St. Petersburg). Next, the Bolsheviks seized control of the Duma, expelled the members of other political parties, and then stated their intention to pursue the goals that no other major party had been willing to: unconditional peace with Germany and land to the peasants with no compensation for landowners. In early 1918, after consolidating their control in Petrograd and Moscow, the Bolsheviks signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany, granting Germany huge territorial concessions in return for peace (Germany would lose those new territories when it lost the war itself later that year).

Almost immediately, a counter-revolution erupted and civil war broke out. The Bolsheviks proved effective at rallying troops to their cause and leading those troops in war. Their “Red Army” engaged the “White” counter-revolutionaries all over western Russia and the Ukraine. For their part, the Whites were an ungainly coalition of former Tsarists, the liberals who had been alienated by the Bolshevik takeover of the Duma, members of ethnic minorities who wanted political independence, an anarchist peasant army in the Ukraine, and troops sent by foreign powers (including the United States), terrified of the prospect of a communist revolution in a nation as large and potentially powerful as Russia. Despite the fact that very few Russians were active supporters of communist ideology, the Red Army still proved both coherent and effective under Bolshevik leadership.

The ensuing war was brutal, ultimately killing close to ten million people (most were civilians who were massacred or starved), and lasting for four years. In the end, however, the Bolsheviks prevailed in Russia itself, Ukraine, and Central Asia. Some Eastern European countries, including Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states, did gain their independence thanks to the war, but everywhere else in the former Russian Empire the Bolsheviks succeeded in creating a new communist empire in its place: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

Early Twentieth-Century Cultural Change

The Bolshevik Revolution and the subsequent creation of the USSR represents perhaps the most striking political event of its time, but it occurred during a period of profound political, cultural, and intellectual instability across Europe and much of the world. The first few decades of the twentieth century revolved around World War I in many ways, but even before the war began Western society was riven with cultural and political conflict. It was an incredibly tumultuous time, one in which “Western Civilization” struggled to define itself in the face of scientific progress and social change that seemed to be speeding forward ever faster.

Part of this phenomenon was the fact that the old order of monarchy and nobility was finally, definitively destroyed, a casualty of World War I. Never again would kings and emperors and noblemen share power over European countries. At the same time, the great political project of the nineteenth century, republican democracy, seemed profoundly disappointing to many Europeans, who had watched it degenerate into partisan squabbles that were helpless to prevent the Great War and its terrible aftermath. In that aftermath there was a terrific flowering of cultural and intellectual production even as the continent struggled to recover economically. It is tempting to see these years, especially the interwar period between 1918 and 1939, as nothing more than the staging ground for World War II, but a more accurate picture reveals them as being much more than just a prequel.

Modernism

Modernism in the arts refers to a specific period starting around 1900 and coming into its own in the 1920s. It expressed a set of common attitudes and assumptions that centered on a rejection of established authority. It was a movement of skepticism directed toward the post-Victorian middle class, an overhaul of the entire legacy of comfort, security, paranoia, rigidity, and hierarchy. It rejected the premise of melodrama, namely clear moral messages in art and literature that were meant to edify and instruct. Socially, it was a reaction against the complacency of the bourgeoisie, of their willingness to start wars over empire and notions of nationalism.

Modernist art and literature sometimes openly attacked the moral values of mainstream society, but sometimes experimented with form itself and simply ignored moral issues. This was the era of

l’art pour l’art

(“art for art’s sake”), of creation disinterred from social or intellectual duty. Artists broke with the idea that art should “represent” something noble and beautiful, and instead many indulged in wild experiments and deliberately created disturbing pieces meant to provoke their audience. Sometimes, modernists were distinctly “modern” in glorifying industrialism and technology, while other times they were modern in that they were experimenting with entirely novel approaches to creation.

One of the quintessential modernist movements was Futurism. Starting in Italy before World War I, Futurism was a movement of poets, playwrights, and painters who celebrated speed, technology, violence, and chaos. Their stated goal was to destroy the remnants of past art and replace it with the art of the future, an art that reflected the modern, industrial world. Futurism sought something new and better than what the Victorian bourgeoisie had come up with: something heroic.

In 1909, F.T. Marinetti, the movement’s founder, wrote the Futurist Manifesto. In it, he thundered that the Futurists wanted to “sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness,” and that “poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown.” The Manifesto went on to proclaim, ominously, that “we want to glorify war – the only cure for the world” and that the Futurists were dedicated to demolishing “museums and libraries” and sought to “fight morality, feminism, and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.” The Manifesto, in short, was a profound expression of dissatisfaction with the mainstream culture of Europe leading up to World War I, and its proponents were proud partisans of violence, elitism, and misogyny.

Futurist art itself was often bizarre and provocative – one Futurist play consisted of a curtain opening to an empty stage, the sound of a gunshot and a scream offstage, and the closing of the curtain. Futurist paintings often depicted vast clouds of dark smoke with abstract images of trains and radio towers, or sometimes just jumbles of colour. While their politics were as murky as some of their art early on, after World War I most of the Futurists embraced fascism, seeing in fascism a political movement that reflected their desire for a politics that was new, virile, and contemptuous of democracy.

The Futurists were just one branch of modernism in the In visual arts. Other schools existed across Europe, including Vorticism in England, Expressionism in Austria, and Cubism in France. Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973), the major cubist painter and sculptor, was one of the quintessential modernist painters in that he portrayed objects, people, even the works of past masters, but he did so from several different perspectives at once. The English Vorticists, meanwhile, attempted to capture the impression of motion in static paintings, not least by depicting literal explosions in their art.

Among the creators of the most striking, sometimes beautiful, but other times grotesque images associated with modernism were the Austrian expressionists. The major point of expressionism was to put the artist’s inner life on display through abstract, often disturbing images. The governing concept was not to depict things “as they are,” but instead to reflect the disturbing realities of the artist’s mind and spirit. The greatest Austrian expressionist was Gustav Klimt (1862 – 1918), who created beautiful but haunting and often highly eroticized portraits, the most famous of which became one of the quintessential dorm room decorations of collegiate America – The Kiss.

In 1901, the University of Vienna commissioned Klimt to create paintings to celebrate the three great branches of traditional academic scholarship: philosophy, medicine, and law. In each case, Klimt created frightening images in which the nominal subject matter was somehow present, but was overshadowed by the grotesque depiction of either how it was being carried out or how it failed to adequately address its subject. Philosophy, for instance, depicts a column of naked, wretched figures clinging to one another over a starry abyss, with a sinister, translucent face visible in the backdrop. The paintings were all beautiful and skillfully rendered, but also dark and disturbing (the originals were destroyed by the Nazis during their occupation of Austria – Modernism was considered “degenerate art” by the Nazi party).

One of Klimt’s students was Egon Schiele (1890 – 1918), who subverted Klimt’s themes (which, although very dark, were also beautiful) and openly celebrated the ugly and threatening. His self-portraits in particular were meant to portray his own perversity and depression; he normally painted himself in the nude looking emaciated, threatening, and grim. Whereas Klimt sought to capture at least some positive or pleasurable aspects of the human spirit and the mind that existed at the unconscious level, Schiele’s work almost brutally portrayed the ugliness embedded in his own psyche.

Modernism was not confined to literature and the visual arts, however. Some composers and musicians in the first decades of the twentieth century sought to shatter musical traditions, defying the expectations of their listeners by altering the very scales, notes, and tempos that western audiences were used to hearing. Some of the resulting pieces eventually became classics in their own right, while others tended to become part of the history of music more so than music very many people actually listened to.

One of the most noteworthy modernist composers was Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971). A Russian composer, Stravinsky’s was best known for his Rite of Spring. The Rite of Spring was a ballet depicting the fertility rites of the ancient Scythians, the nomadic people native to southern Russia in the ancient past. Staged by classical ballet dancers, the Rite of Spring completely scandalized its early audiences; at its first performance in Paris, members of the audience hissed at the dancers, and pelted the orchestra with debris, while the press described it as pornographic and barbaric. The dancers lurched about on stage, sometimes in an overtly sexual manner, and the music changed its tempo and abandoned its central theme. Within a few years, however (and following a change in its wild choreography), the Rite became part of ballet’s canon of great pieces.

In contrast, the Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874 – 1951) invented a form of orchestral music that remains more of an important influence to avant-garde musicians and composers than something actively listened to by mainstream audiences. Schoenberg’s major innovations consisted of experiments with atonality – music without a central, binding key – and a newly-invented twelve-tone scale of his own creation. Schoenberg was among the first to defy the entire tradition of western music in his experiments. Ever since the Renaissance, western musicians had worked in basically the same set of scales. As a result, listeners were “trained” from birth to expect certain sounds and certain rhythms in music. Schoenberg deliberately subverted those expectations, inserting dissonance and unexpected notes in many of his works.

Similar in some ways to the innovations in the visual arts and music, modernist literature created out a new approach to poetry and prose. Authors like Virginia Woolf, Marcel Proust, Franz Kafka, and James Joyce (whose places of origins spanned from Dublin to Prague) created a new form of literature in which the nominal plot of a story was less important than the protagonist’s inner life and experience of his or her surroundings and interactions. Joyce’s (incredible difficult to read) novel Ulysses described a single unremarkable day in the life of a man in Dublin, Ireland, focusing on the vast range of thoughts, emotions, and reactions that passed through the man’s consciousness rather than on the events of the day itself. Proust and Woolf also wrote works focused on the inner life rather than the outside event, and Woolf was also a seminal feminist writer. Kafka’s work brilliantly, and tragically, satirized the experience of being lost in the modern world, hemmed in by impersonal bureaucracies and disconnected from other people – his most famous story, Metamorphosis, describes the experience of a young man who awakens one day to discover that he has become a gigantic insect, but whose immediate concern is that he will be unable to make it in to his job.

Ultimately, artistic modernism in the arts, music, and literature questioned the (post-)Victorian obsession with traditional morality, hierarchy, and control. The inner life was not straightforward – it was a complicated mess of conflicting values, urges, and drives, and traditional morality was often a smokescreen over a system of repression and violence. Certain modernist artists attacked the system, while others exposed its vacuity, its emptiness or shallowness, against the darker, more complex reality they thought lay underneath.

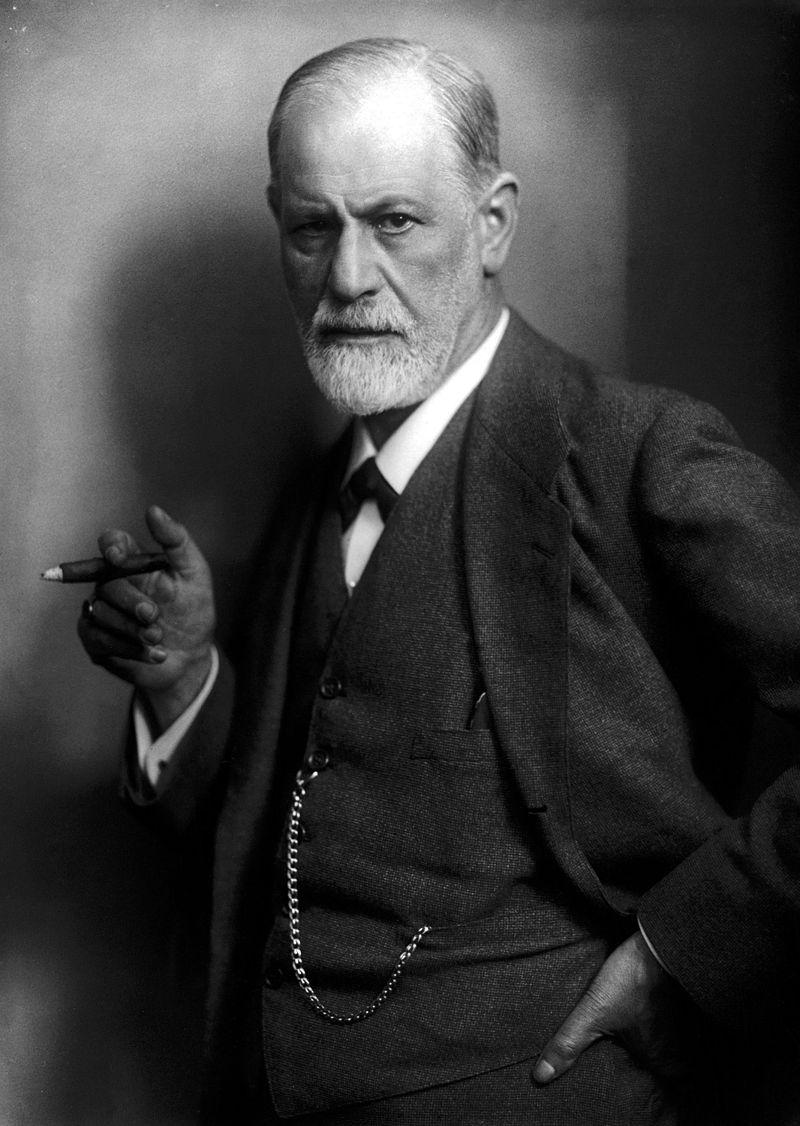

Freud

While not an artist himself, the great thinker of modernism was, in many ways, Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939). Freud was one of the founders of the medical and scientific discipline of psychology. He was the forefather of the concept of modern therapy itself and his theories, while now largely rejected by psychologists in terms of their empirical accuracy, nevertheless continue to exert tremendous influence. In historical hindsight, Freud’s importance derives from his work as a philosopher of the mind more so than as a “scientist” per se, although it was precisely his drive for his work to be respected as a true science that inspired his research and writing.

Freud was born in Moravia (today’s Czech Republic) in 1856, and his family eventually moved to Vienna, the capital of the Austrian Empire of which Moravia was part. Freud was Jewish, and his family underwent a generational transformation that was very common among Central European Jews in the latter part of the nineteenth century, following legal emancipation from anti-Semitic laws: his grandparents were unassimilated and poor, his parents were able to create a successful business in a major city, and Freud himself became a highly-educated professional (he received his medical degree in 1881). Many of Freud’s theories were influenced by his own experience as a brilliant scholar who happened to be Jewish, living in a society rife with anti-Semitism – he sought to understand the inner psychological drives that led people to engage in irrational behavior.

Freud’s greatest accomplishment was diagnosing the essential irrationality of the human mind. Influenced by modernist philosophers, by great writers like Shakespeare, and by Darwin’s work on evolution, Freud came to believe that the mind itself “evolved” from childhood into adulthood in a fundamentally hostile psychic environment. The mind was forced to conform to social pressure from outside while being enslaved to its own unconscious desires (the “drives”) that sought unlimited power and pleasure. Freud wanted to be the “Darwin of the mind,” the inventor of a truescience of psychology that could explain and, he hoped, cure psychological disorders.

Freud became well known because of his work with “hysterical” patients. The word hysteria is related to the Greek hystera, meaning womb. Essentially, “hysteria” consisted of physical symptoms of panic, pain, and paralysis in women who had no detectable physical problems. “Hysteria” was a term invented to blame the female anatomy for physical symptoms, in the absence of other discernible causes. Freud, however, believed that hysteria was the result not of some unknown physical problem among women, but instead a physical result of psychological trauma – in almost all cases, that of what we would now describe as sexual abuse.

Freud built on the work of an earlier psychologist and employed the “talking cure” with his hysterical patients, naming his version of the talking cure “psychoanalysis.” The talking cure was the process by which the therapist and the patient recounted memories, dreams, and events, searching for a buried, suppressed idea that is causing physical symptoms. As Freud’s theories developed, he identified a series of common causes tied to childhood traumas that seemed remarkably consistent. He extrapolated those into “scientific” truths, most of which had to do with the development of sexual identity. This culminated in his 1905 Three Essays in the Theory of Sexuality.

The Freudian “talking cure” was verbal, inferential, and in a way speculative, since it was about the conversation between the therapist and the patient, working toward causes of mental disorder. The analyst played an active role, above and beyond the medical diagnosis of disorder. Freud believed that the human mind was almost always arrested in its progress toward mental health from childhood to adulthood. It was possible to be “healthy,” to be mostly unencumbered by mental disorders, but it was also very difficult to arrive at that position. In turn, he hoped that his theories would create “the possibility of happiness.”

Ultimately, Freud’s most important theories had to do with the nature of the unconscious mind. According to Freud, the thoughts and feelings we experience and can control are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. Most thoughts and feelings are buried in the unconscious. Within the unconscious are stored repressed memories that trigger responses, verbal slips, and dreams, symptoms of their existence. It is always terribly difficult to reconcile one’s desires and the requirements of socialization (of living in a society with its own rules and laws) and that leads inevitably to inner conflict. Thus, people form defense systems that may protect their emotions in the short term, but return later in life to cause unhappiness and alienation.

According to Freud, there are three basic areas or states that exist simultaneously in the human mind. First, part of the unconscious is the “Id:” the seat of the drives for pleasure (sexual lust, power, security, food, alcohol and other drugs, etc.) and for what might be considered “obsession” – the seemingly irrational desires that have nothing to do with pleasure per se (pyromania, kleptomania, or seemingly self-destructive political activity). Freud called the drive for pleasure ” eros,”

the Pleasure Principle, and the obsessive and self-destructive drive “thanatos,” the Death Drive.

Next, Freud identified another area of the unconscious as the “Superego:” the social pressure to conform, the confrontation with outside authority, and the overwhelming sense of shame and inadequacy that can, and usually does, result from facing all of the pressures of living in human society. In the context of his own, deeply Victorian bourgeois society, Freud identified the Superego’s demands as having to do primarily with the suppression of the desires that arose from the Id.

Finally, the only aspect of the human psyche the mind is directly aware of is the “Ego:” the embattled conscious mind, forced to reconcile the drives of the Id and Superego with the “reality principle,” the knowledge that to give in to one’s urges completely would be to risk injury or death. In Freud’s theory, the reason most people have so many psychological problems is that the Ego is perpetually beset by these powerful forces it is not consciously aware of. The Id bombards the Ego with an endless hunger for indulgence, while the Superego demands social conformity.

In short, Freud described the mind itself as defying control: despite the illusion of free will and autonomy, no one is capable of complete self-control. Freudian theory suggested that the life of the mind was complicated and opaque, not rational and straightforward. The great dream of the optimistic theorists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had been that proper education and rational politics could create a perfect society. Freud, however, cautioned that no one is completely rational, and that politics could easily follow the path of the Death Drive and plunge whole nations, even whole civilizations, into self-destruction. He lived to see at least part of his worst fears come to pass at the end of the life as he fled from the Nazi takeover of Austria in 1938.

One other major theme present in Freud’s theories had to do with sexuality, which he believed to be of central importance to psychology. His theories largely revolved around sexual instincts and their repression, and he invented various specific concepts like the “Oedipus complex,” the idea that young boys sexually desire their mothers and fear the authority of their fathers, and “penis envy,” the claim that girls are psychologically wounded by not having male genitalia, that he claimed were fundamental to the human psyche. For all his insight, and all his clinical work with women patients, however, Freud remained convinced that women were in a sense less “evolved” than men and were biologically destined for a secondary role. He also admitted that he could not really figure out women’s motivations; he famously asserted that the question that psychology could not answer was “what does a woman want?” In the end, the irony of Freud’s take on gender and sexuality is that it simply reproduced age-old sexual stereotypes and double standards, however important his other theories were in exploring the unconscious. Despite the genuine changes occurring to gender in the society around him, Freud remained embedded in the assumption that a male and female physiology dictated separate and unequal destinies for men and women.

Gender Roles

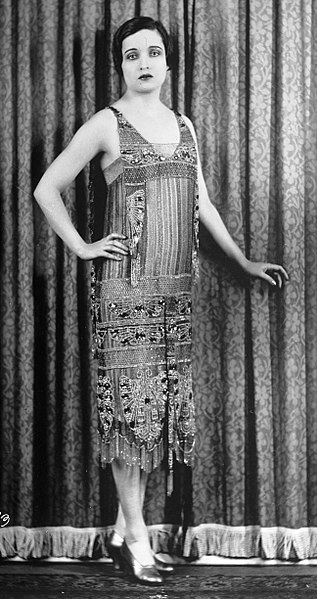

Those destinies, however, were slowly changing. As noted in the discussion of World War I in the previous chapter, gender roles had been transformed both economically and culturally during (and because of) the war. Some of those changes were durable. The range of jobs available to women was certainly larger than it had been before the war. Women continued to wear more comfortable and practical clothing after the war than before it, the restrictive ankle-length dress replaced by the looser, calf-length dress or skirt. Some women continued to cut their hair short, and of course women’s suffrage was finally realized (albeit with various restrictions) in most European countries and the United States over the course of the 1920s.

No sooner had the war ended, however, that men generally did everything in their power to reverse many of the changes to gender roles it had caused. Through a combination of legal restrictions and quasi-legal practices, women were forced from traditional male jobs, prevented from enrolling in universities and medical schools, and paid significantly less than men for the same work. Fascist parties (described in a following chapter) were explicitly devoted to enforcing traditional gender roles, and when some countries were overtaken by fascist rule women were often forced out of the workplace. Everywhere, most men (and many women) continued to insist that women were inherently biologically inferior to men and that it was the “natural” role of men to serve as head of the household and head of the nation-state in equal measure.

The exemplar of both the greater freedom enjoyed by women and male resentment of that freedom was the “New Woman.” A stock figure in the media of the time, the New Woman was independent, working at her own job full time and living by herself, and able to enjoy a social life that included drinking, dancing, and even the possibility of casual sex. The famous “flappers” of the 1920s, young women in the latest fashion who danced to cutting-edge American jazz and wore scandalously short, knee-length dresses, were the ultimate expression of the New Woman. While the image of the New Woman was greatly exaggerated, both in advertising and by male misogynists, there was at least a kernel of truth to the archetype. Far more women were independent by the 1920s than in the past, fashions really had changed, and thanks to halting advances in contraception, casual sexual relationships were easier to have without fear of pregnancy. It would take at least another half-century, however, for laws against sexual discrimination to come into being in most countries, and of course the struggle for cultural equality remains unfulfilled to this day.

The Great Depression

Modernism in the arts and modernist theory came of age before, during, and after World War I; some of the most interesting writing and art of the modernist movement occurred during the 1920s. The political order of Europe (Russia, as usual, was an exception) and the United States during the 1920s was beset by struggle and conflict, but while the economies of the west struggled to recover from World War I, there was at least some economic growth. That growth came crashing to a halt in 1929 with the advent of the Great Depression.

The Great Depression has the dubious distinction of being the worst economic disaster in the modern era. It constituted an almost total failure of governments, businesses, and banks to anticipate or prevent economic disaster or to effectively deal with it. The Depression explains in large part the appeal of extremist politics like Nazism, in that the average person was profoundly frightened by what had happened to their world; instead of progress resulting in better standards of living, all of a sudden the hard-won gains of the recent past were completely ruined.

The background to the Depression was the financial mess left by World War I. The victorious alliance of Britain and France imposed massive reparations on Germany – 132 billion gold marks. In addition, the former members of the Triple Entente themselves owed enormous sums to the United States for the loans they had received during the war, amounting to approximately $10 billion. Over the course of the 1920s, as the German economy struggled to recover (at one point the value of German currency collapsed completely in the process), the US government oversaw enormous loans to Germany. In the end, a “triangle” of debt and repayment locked together the economies of the United States and Europe: US loans underwrote German reparation payments to Britain and France, with Britain and France then trying to pay off their debts to the US. None of the debts were anywhere near settled by the end of the 1920s, not least because more loans were still flooding into the market.

The Depression started in the United States with a massive stock market crash on October 24, 1929. The ill-conceived cycle of debt described above had worked well enough for most of the 1920s while the American economy was stable and American banks were willing to underwrite new loans. When the stock market crashed, however, American banks demanded repayment of the European loans, from Germany and its former enemies alike. The capital to repay those loans simply did not exist. Businesses shut down, governments defaulted on the American loans, and unemployment soared. In one year, Germany’s industrial output dropped by almost 50% and millions were out of work. In turn, inspired by liberal economic theories, governments embraced policies of austerity, cutting back the already limited social programs that existed, balancing state budgets, and slashing spending. The result was that even less capital was available in the private sector. In the United States and Western Europe, the Depression would drag on for a decade (1929 – 1939), at which point World War II overshadowed economic hardship as the great crisis of the century.

Summing Up

What do Modernist art, Freudian psychology, shifts in gender, and the Great Depression have in common besides chronological coincidence? They were all, in different ways, symptoms of disruption and (often) a profound sense of unease that pervaded Western culture after World War I. European civilization was powerful and self-confident before the war, master of over 80% of the globe, and at the forefront of science and technology. That civilization emerged from four years of bloodshed economically shattered, politically disunited, and in many ways skeptical of the possibility of further progress. It was in this uncertain context that the most destructive political philosophy in modern history emerged: fascism, and its even more horrific offshoot, Nazism.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Nikolai II and George V – Public Domain

Rasputin – Public Domain

Lenin Speech– Public Domain

Klimt The Kiss– Public Domain

Klimt Philosophy – Public Domain

Freud – Public Domain

Alice Joyce – Public Domain