7.8 Homeostasis and Feedback

Steady as She Goes

This device (Figure 7.8.1) looks simple, but it controls a complex system that keeps a home at a steady temperature — it’s a thermostat. The device shows the current temperature in the room, and also allows the occupant to set the thermostat to the desired temperature. A thermostat is a commonly cited model of how living systems — including the human body— maintain a steady state called homeostasis.

What Is Homeostasis?

Homeostasis is the condition in which a system (such as the human body) is maintained in a more or less steady state. It is the job of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems throughout the body to maintain many different variables within narrow ranges compatible with life. Keeping a stable internal environment requires continually monitoring the internal environment and constantly making adjustments to keep things in balance.

Set Point and Normal Range

For any given variable, such as body temperature or blood glucose level, there is a particular set point that is the physiological optimum value. The set point for human body temperature, for example, is about 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). As the body works to maintain homeostasis for temperature or any other internal variable, the value typically fluctuates around the set point. Such fluctuations are normal, as long as they do not become too extreme. The spread of values within which such fluctuations are considered insignificant is called the normal range. In the case of body temperature, for example, the normal range for an adult is about 36.5 to 37.5 degrees C (97.7 to 99.5 degrees F).

A good analogy for set point, normal range, and maintenance of homeostasis is driving. When you are driving a vehicle on the road, you are supposed to drive in the centre of your lane — this is analogous to the set point. Sometimes, you are not driving in the exact centre of the lane, but you are still within your lines, so you are in the equivalent of the normal range. However, if you were to get too close to the centre line or the shoulder of the road, you would take action to correct your position. You’d move left if you were too close to the shoulder, or right if too close to the centre line — which is analogous to our next concept, negative feedback to maintain homeostasis.

Maintaining Homeostasis

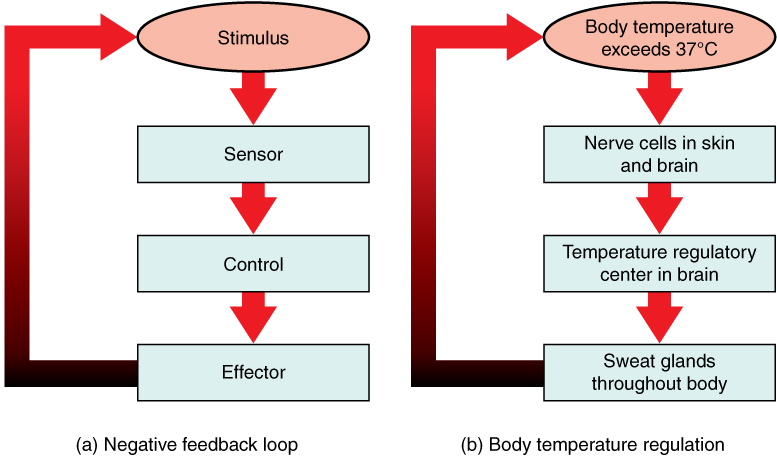

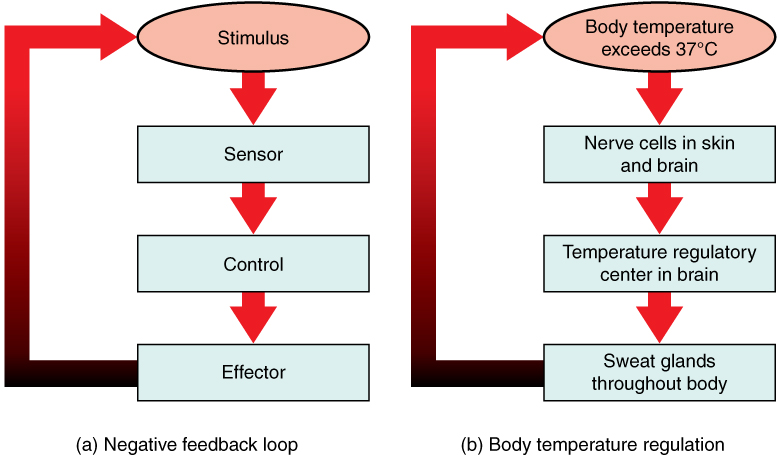

Homeostasis is normally maintained in the human body by an extremely complex balancing act. Regardless of the variable being kept within its normal range, maintaining homeostasis requires at least four interacting components: stimulus, sensor, control centre, and effector.

- The stimulus is provided by the variable being regulated. Generally, the stimulus indicates that the value of the variable has moved away from the set point or has left the normal range.

- The sensor monitors the values of the variable and sends data on it to the control centre.

- The control centre matches the data with normal values. If the value is not at the set point or is outside the normal range, the control centre sends a signal to the effector.

- The effector is an organ, gland, muscle, or other structure that acts on the signal from the control centre to move the variable back toward the set point.

Each of these components is illustrated in Figure 7.8.2. The diagram on the left is a general model showing how the components interact to maintain homeostasis. The diagram on the right shows the example of body temperature. From the diagrams, you can see that maintaining homeostasis involves feedback, which is data that feeds back to control a response. Feedback may be negative (as in the example below) or positive. All the feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis use negative feedback. Biological examples of positive feedback are much less common.

Negative Feedback

In a negative feedback loop, feedback serves to reduce an excessive response and keep a variable within the normal range. Two processes controlled by negative feedback are body temperature regulation and control of blood glucose.

Body Temperature

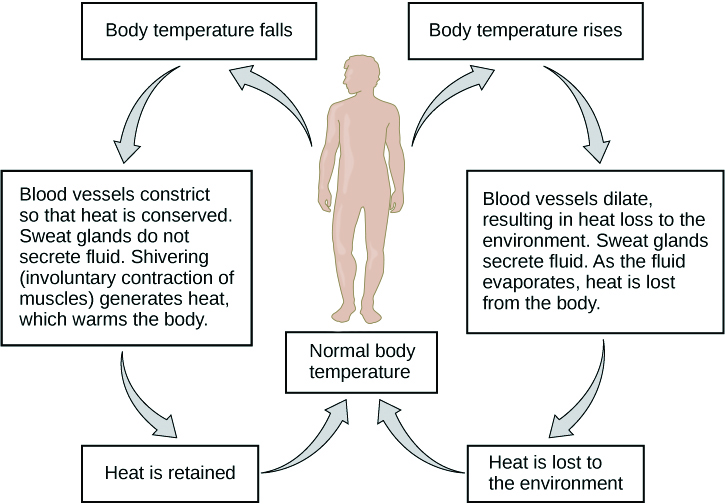

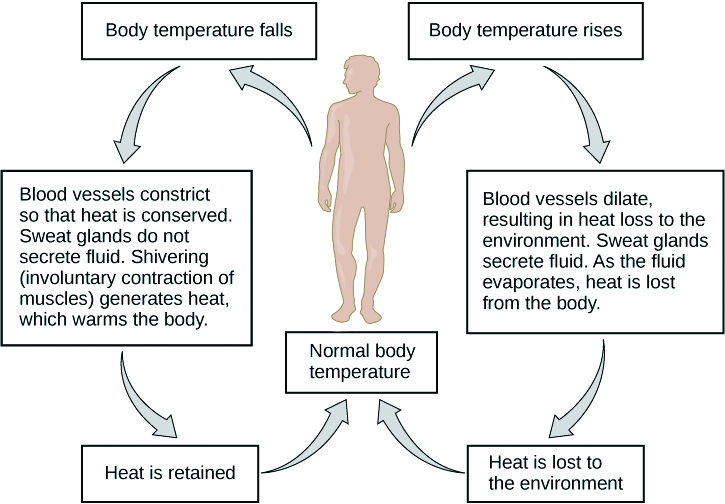

Body temperature regulation involves negative feedback, whether it lowers the temperature or raises it, as shown in Figure 7.8.3 and explained in the text that follows.

Cooling Down

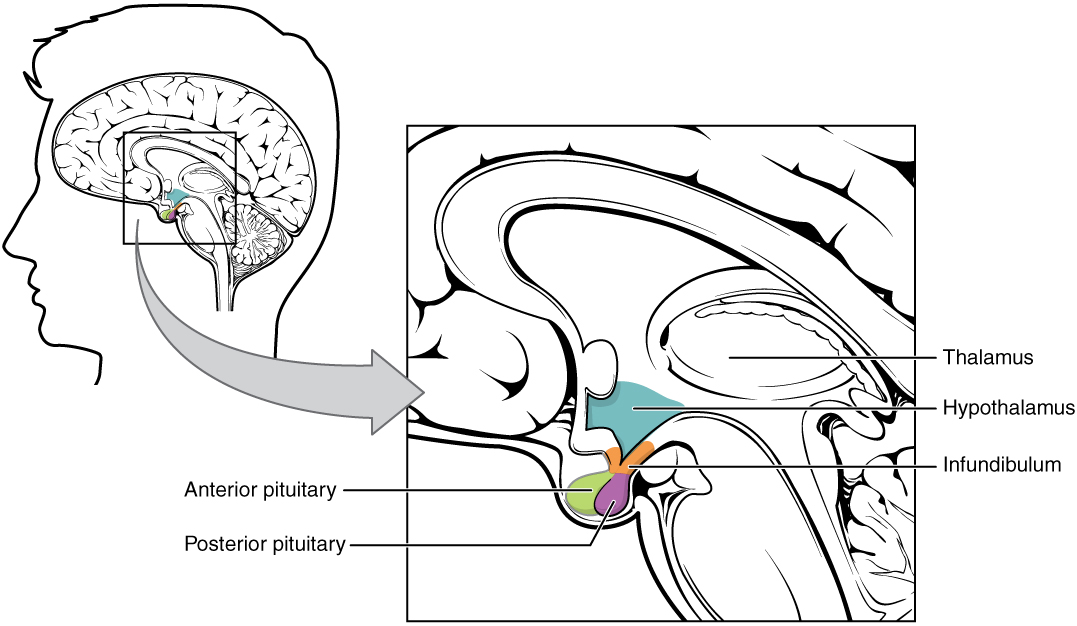

The human body’s temperature regulatory centre is the hypothalamus in the brain. When the hypothalamus receives data from sensors in the skin and brain that body temperature is higher than the set point, it sets into motion the following responses:

- Blood vessels in the skin dilate (vasodilation) to allow more blood from the warm body core to flow close to the surface of the body, so heat can be radiated into the environment.

- As blood flow to the skin increases, sweat glands in the skin are activated to increase their output of sweat (diaphoresis). When the sweat evaporates from the skin surface into the surrounding air, it takes heat with it.

- Breathing becomes deeper, and the person may breathe through the mouth instead of the nasal passages. This increases heat loss from the lungs.

Heating Up

When the brain’s temperature regulatory centre receives data that body temperature is lower than the set point, it sets into motion the following responses:

- Blood vessels in the skin contract (vasoconstriction) to prevent blood from flowing close to the surface of the body, which reduces heat loss from the surface.

- As temperature falls lower, random signals to skeletal muscles are triggered, causing them to contract. This causes shivering, which generates a small amount of heat.

- The thyroid gland may be stimulated by the brain (via the pituitary gland) to secrete more thyroid hormone. This hormone increases metabolic activity and heat production in cells throughout the body.

- The adrenal glands may also be stimulated to secrete the hormone adrenaline. This hormone causes the breakdown of glycogen (the carbohydrate used for energy storage in animals) to glucose, which can be used as an energy source. This catabolic chemical process is exothermic, or heat producing.

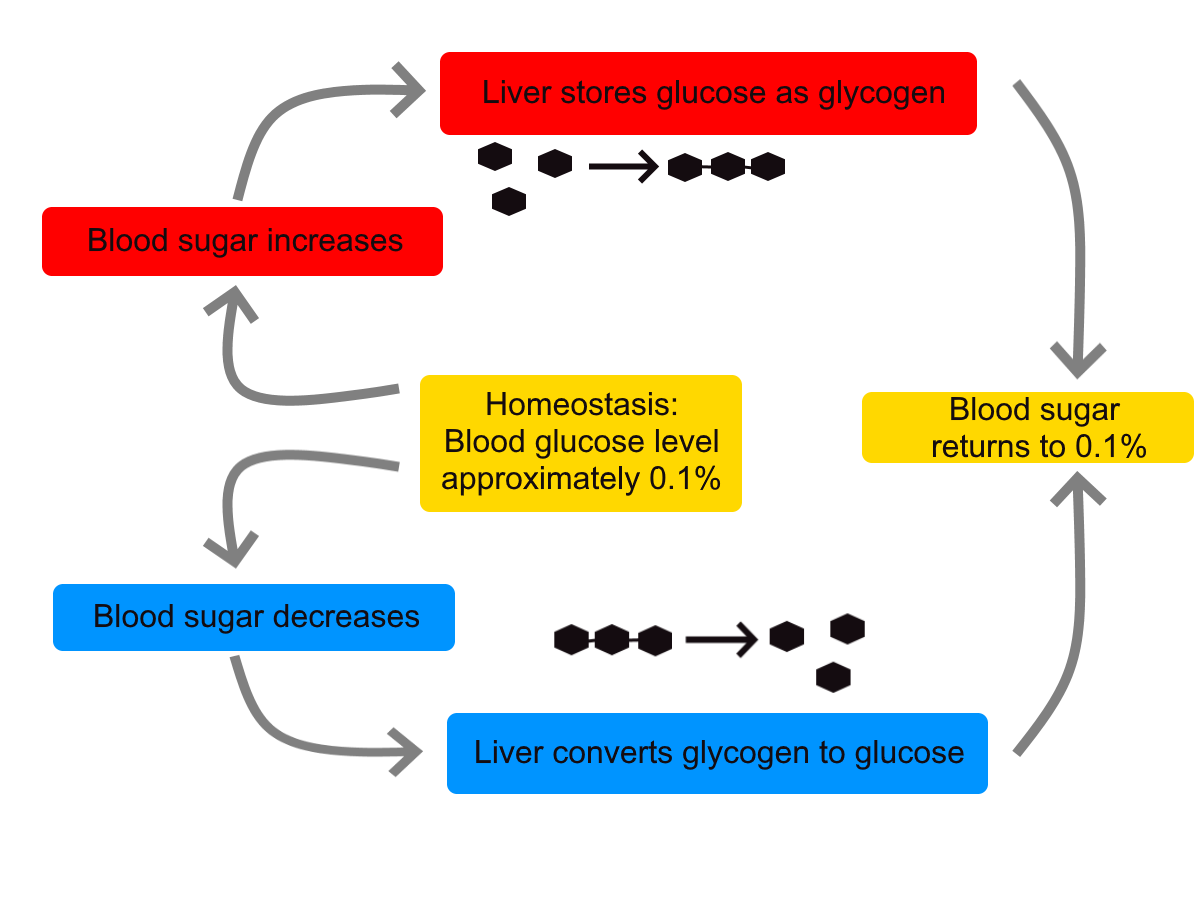

Blood Glucose

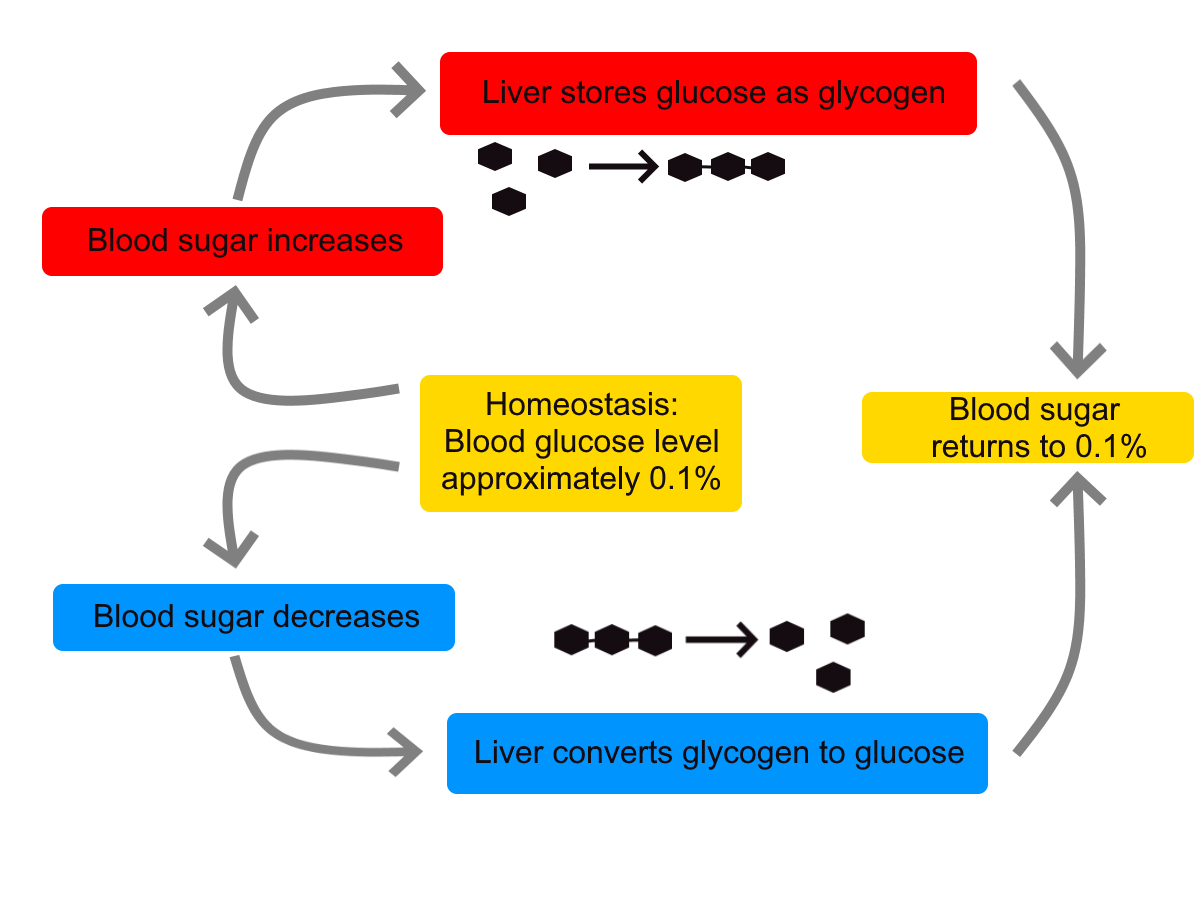

In controlling the blood glucose level, certain endocrine cells in the pancreas (called alpha and beta cells) detect the level of glucose in the blood. They then respond appropriately to keep the level of blood glucose within the normal range.

- If the blood glucose level rises above the normal range, pancreatic beta cells release the hormone insulin into the bloodstream. Insulin signals cells to take up the excess glucose from the blood until the level of blood glucose decreases to the normal range.

- If the blood glucose level falls below the normal range, pancreatic alpha cells release the hormone glucagon into the bloodstream. Glucagon signals cells to break down stored glycogen to glucose and release the glucose into the blood until the level of blood glucose increases to the normal range.

Homeostasis and Negative/Positive Feedback, Amoeba Sisters, 2017.

Positive Feedback

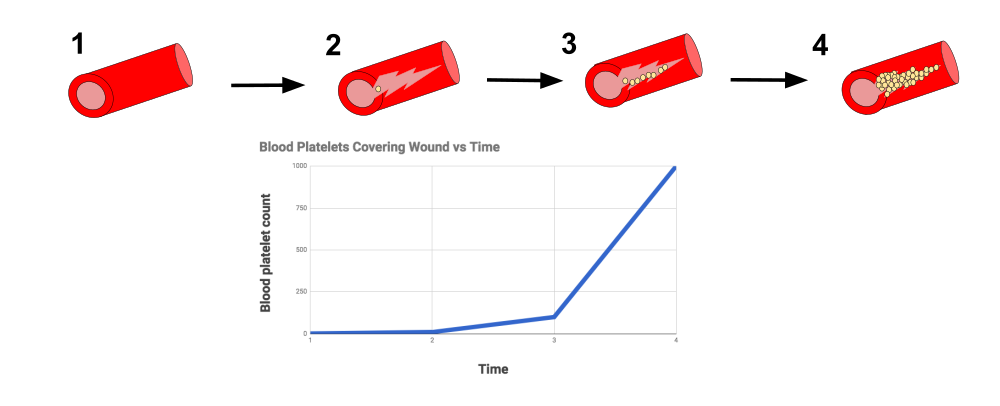

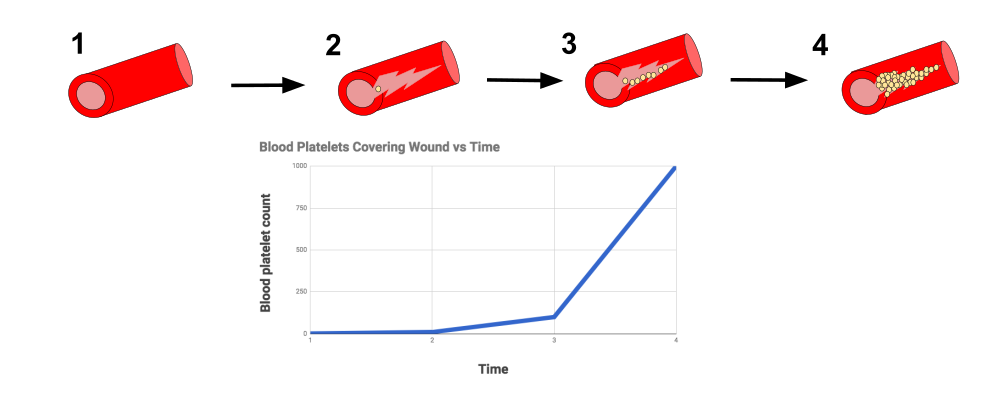

In a positive feedback loop, feedback serves to intensify a response until an end point is reached. Examples of processes controlled by positive feedback in the human body include blood clotting and childbirth.

Blood Clotting

When a wound causes bleeding, the body responds with a positive feedback loop to clot the blood and stop blood loss. Substances released by the injured blood vessel wall begin the process of blood clotting. Platelets in the blood start to cling to the injured site and release chemicals that attract additional platelets. As the platelets continue to amass, more of the chemicals are released and more platelets are attracted to the site of the clot. The positive feedback accelerates the process of clotting until the clot is large enough to stop the bleeding.

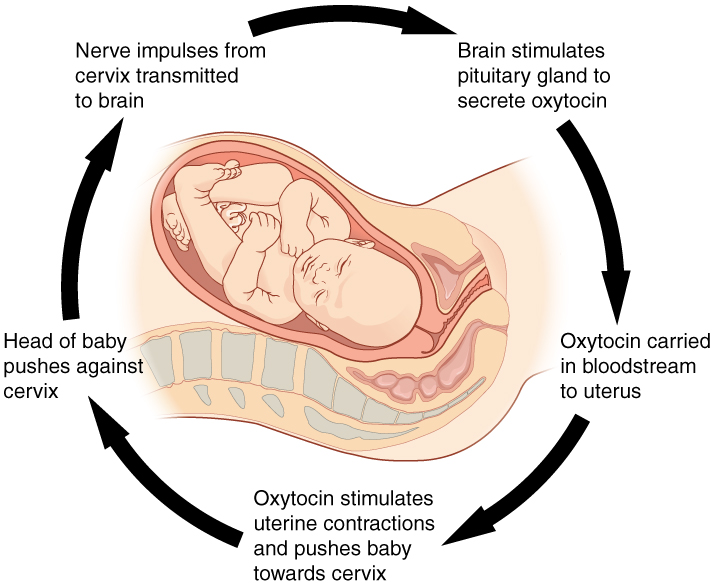

Childbirth

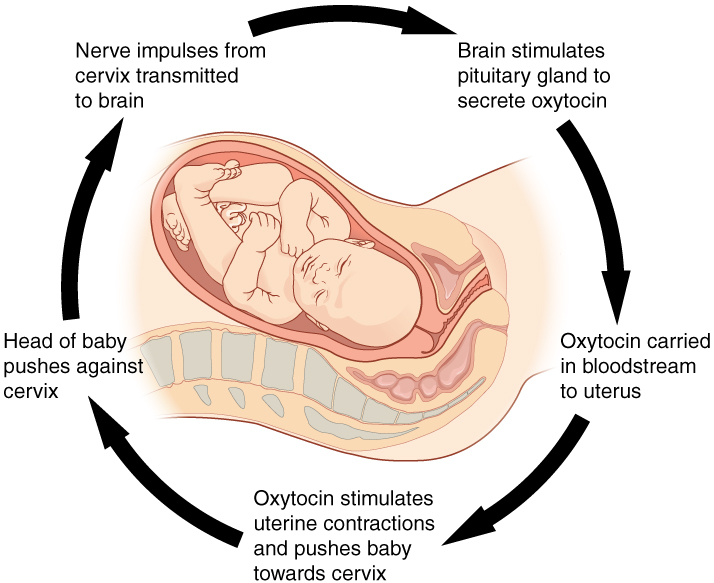

Figure 7.8.6 shows the positive feedback loop that controls childbirth. The process normally begins when the head of the infant pushes against the cervix. This stimulates nerve impulses, which travel from the cervix to the hypothalamus in the brain. In response, the hypothalamus sends the hormone oxytocin to the pituitary gland, which secretes it into the bloodstream so it can be carried to the uterus. Oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions, which push the baby harder against the cervix. In response, the cervix starts to dilate in preparation for the passage of the baby. This cycle of positive feedback continues, with increasing levels of oxytocin, stronger uterine contractions, and wider dilation of the cervix until the baby is pushed through the birth canal and out of the body. At that point, the cervix is no longer stimulated to send nerve impulses to the brain, and the entire process stops.

Normal childbirth is driven by a positive feedback loop. Positive feedback causes an increasing deviation from the normal state to a fixed end point, rather than a return to a normal set point as in homeostasis.

When Homeostasis Fails

Homeostatic mechanisms work continuously to maintain stable conditions in the human body. Sometimes, however, the mechanisms fail. When they do, homeostatic imbalance may result, in which cells may not get everything they need or toxic wastes may accumulate in the body. If homeostasis is not restored, the imbalance may lead to disease — or even death. Diabetes is an example of a disease caused by homeostatic imbalance. In the case of diabetes, blood glucose levels are no longer regulated and may be dangerously high. Medical intervention can help restore homeostasis and possibly prevent permanent damage to the organism.

Normal aging may bring about a reduction in the efficiency of the body’s control systems, which makes the body more susceptible to disease. Older people, for example, may have a harder time regulating their body temperature. This is one reason they are more likely than younger people to develop serious heat-induced illnesses, such as heat stroke.

Feature: My Human Body

Diabetes is diagnosed in people who have abnormally high levels of blood glucose after fasting for at least 12 hours. A fasting level of blood glucose below 100 is normal. A level between 100 and 125 places you in the pre-diabetes category, and a level higher than 125 results in a diagnosis of diabetes.

Of the two types of diabetes, type 2 diabetes is the most common, accounting for about 90 per cent of all cases of diabetes in the United States. Type 2 diabetes typically starts after the age of 40. However, because of the dramatic increase in recent decades in obesity in younger people, the age at which type 2 diabetes is diagnosed has fallen. Even children are now being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Today, about 3 million Canadians (8.1% of total population) are living with diabetes.

You may at some point have your blood glucose level tested during a routine medical exam. If your blood glucose level indicates that you have diabetes, it may come as a shock to you because you may not have any symptoms of the disease. You are not alone, because as many as one in four diabetics do not know they have the disease. Once the diagnosis of diabetes sinks in, you may be devastated by the news. Diabetes can lead to heart attacks, strokes, blindness, kidney failure, nerve damage, and loss of toes or feet. The risk of death in adults with diabetes is 50 per cent greater than it is in adults without diabetes, and diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death of adults. In addition, controlling diabetes usually requires frequent blood glucose testing, watching what and when you eat, and taking medications or even insulin injections. All of this may seem overwhelming.

The good news is that changing your lifestyle may stop the progression of type 2 diabetes or even reverse it. By adopting healthier habits, you may be able to keep your blood glucose level within the normal range without medications or insulin. Here’s how:

- Lose weight. Any weight loss is beneficial. Losing as little as seven per cent of your weight may be all that is needed to stop diabetes in its tracks. It is especially important to eliminate excess weight around your waist.

- Exercise regularly. You should try to exercise for at least 30 minutes, five days a week. This will not only lower your blood sugar and help your insulin work better, but it will also lower your blood pressure and improve your heart health. Another bonus of exercise is that it will help you lose weight by increasing your basal metabolic rate.

- Adopt a healthy diet. Decrease your consumption of refined carbohydrates, such as sweets and sugary drinks. Increase your intake of fibre-rich foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. About one-quarter of each meal should consist of high-protein foods, such as fish, chicken, dairy products, legumes, or nuts.

- Control stress. Stress can increase your blood glucose and also raise your blood pressure and risk of heart disease. When you feel stressed out, do breathing exercises or take a brisk walk or jog. Try to replace stressful thoughts with more calming ones.

- Establish a support system. Enlist the help and support of loved ones, as well as medical professionals, such as a nutritionist and diabetes educator. Having a support system will help ensure that you are on the path to wellness, and that you can stick to your plan.

7.8 Summary

- Homeostasis is the condition in which a system (such as the human body) is maintained in a more or less steady state. It is the job of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems throughout the body to maintain homeostasis.

- For any given variable, such as body temperature, there is a particular set point that is the physiological optimum value. The spread of values around the set point that is considered insignificant is called the normal range.

- Homeostasis is generally maintained by a negative feedback loop that includes a stimulus, sensor, control centre, and effector. Negative feedback serves to reduce an excessive response and to keep a variable within the normal range. Negative feedback loops control body temperature and the blood glucose level.

- Positive feedback loops are not common in biological systems. Positive feedback serves to intensify a response until an end point is reached. Positive feedback loops control blood clotting and childbirth.

- Sometimes homeostatic mechanisms fail, resulting in homeostatic imbalance. Diabetes is an example of a disease caused by homeostatic imbalance. Aging can bring about a reduction in the efficiency of the body’s control system, which makes the elderly more susceptible to disease.

7.8 Review Questions

-

-

- Compare and contrast negative and positive feedback loops.

- Explain how negative feedback controls body temperature.

- Give two examples of physiological processes controlled by positive feedback loops.

- During breastfeeding, the stimulus of the baby sucking on the nipple increases the amount of milk produced by the mother. The more sucking, the more milk is usually produced. Is this an example of negative or positive feedback? Explain your answer. What do you think might be the evolutionary benefit of the milk production regulation mechanism you described?

- Explain why homeostasis is regulated by negative feedback loops, rather than positive feedback loops.

- The level of a sex hormone, testosterone (T), is controlled by negative feedback. Another hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), is released by the hypothalamus of the brain, which triggers the pituitary gland to release luteinizing hormone (LH). LH stimulates the gonads to produce T. When there is too much T in the bloodstream, it feeds back on the hypothalamus, causing it to produce less GnRH. While this does not describe all the feedback loops involved in regulating T, answer the following questions about this particular feedback loop.

- What is the stimulus in this system? Explain your answer.

- What is the control centre in this system? Explain your answer.

- In this system, is the pituitary considered the stimulus, sensor, control centre, or effector? Explain your answer.

7.8 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSgEJSlk6W4

Homeostasis – What Is Homeostasis – What Is Set Point For Homeostasis – Homeostasis In The Human Body, Whats Up Dude, 2017.

Attributions

Figure 7.8.1

Nest_Thermostat by Amanitamano on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 7.8.2

Negative_Feedback_Loops by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 7.8.3

Body Temperature Homeostasis by OpenStax College, Biology is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Figure 7.8.4

Homeostasis_of_blood_sugar by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 7.8.5

Positive_Feedback_Diagram_Blood_Clotting by Elliottuttle on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 7.8.6

Pregnancy-Positive_Feedback by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en) license.

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2017, September 7). Homeostasis and negative/positive feedback. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iz0Q9nTZCw4&feature=youtu.be

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, April 25). Figure 1.10 Negative feedback loop [digital image/ diagram]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 1.5). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-5-homeostasis

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, April 25). Figure 1.11 Positive feedback loop normal childbirth is driven by a positive feedback loop [digital image/ diagram]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 1.5). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-5-homeostasis

Cognito. (2018, December 18). GCSE Biology – Homeostasis #38. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMsJ-3qRVJM&feature=youtu.be

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Type 2 diabetes [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-2-diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20351193

OpenStax CNX. (2016, March 23). Figure 4 The body is able to regulate temperature in response to signals from the nervous system [digital image]. In OpenStax, Biology (Section 33.3). https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.8:BP24ZReh@7/Homeostasis

Whats Up Dude. (2017, September 20). Homeostasis – What is homeostasis – What is set point for homeostasis – Homeostasis in the human body. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSgEJSlk6W4&feature=youtu.be

The ability of an organism to maintain constant internal conditions despite external changes.

The smallest unit of life, consisting of at least a membrane, cytoplasm, and genetic material.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

One Piano, Four Hands

Did you ever see two people play the same piano? How do they coordinate all the movements of their own fingers — let alone synchronize them with those of their partner? The peripheral nervous system plays an important part in this challenge.

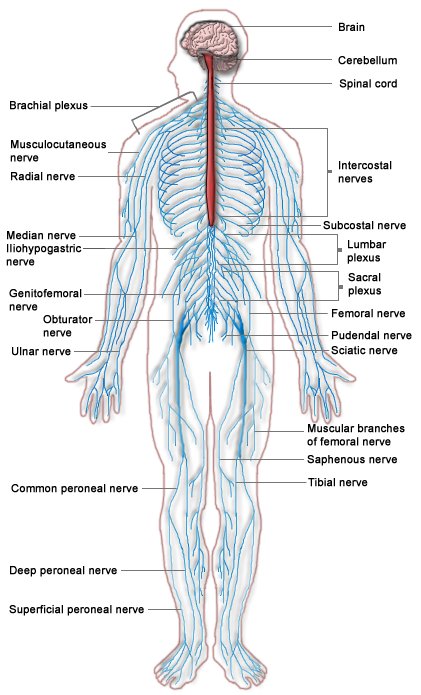

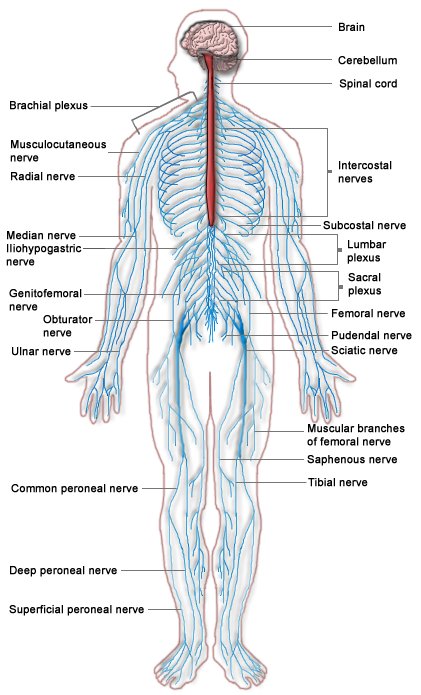

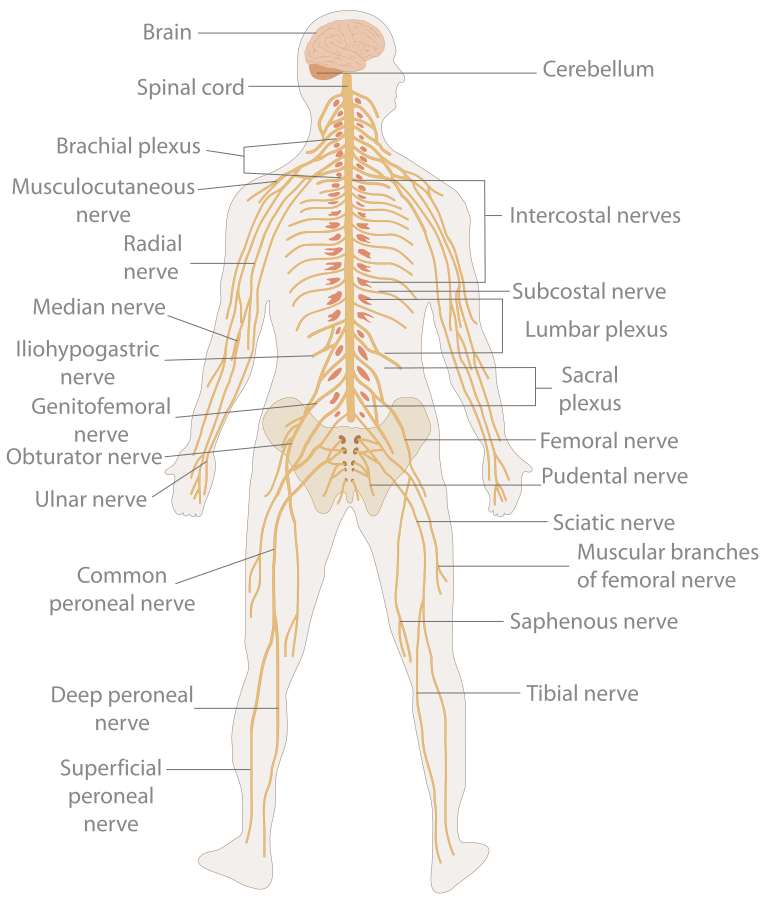

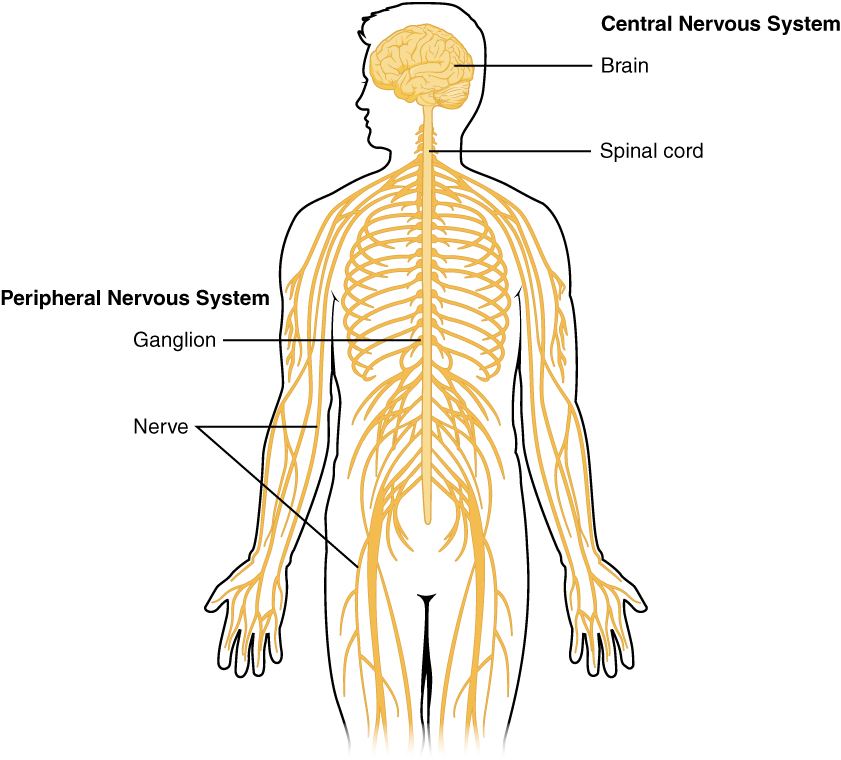

What Is the Peripheral Nervous System?

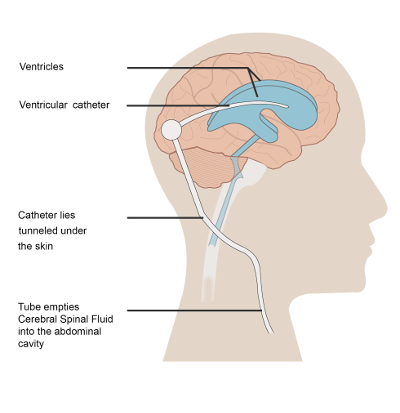

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside of the central nervous system (CNS). The main function of the PNS is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism. It serves as a communication relay, going back and forth between the CNS and muscles, organs, and glands throughout the body.

Tissues of the Peripheral Nervous System

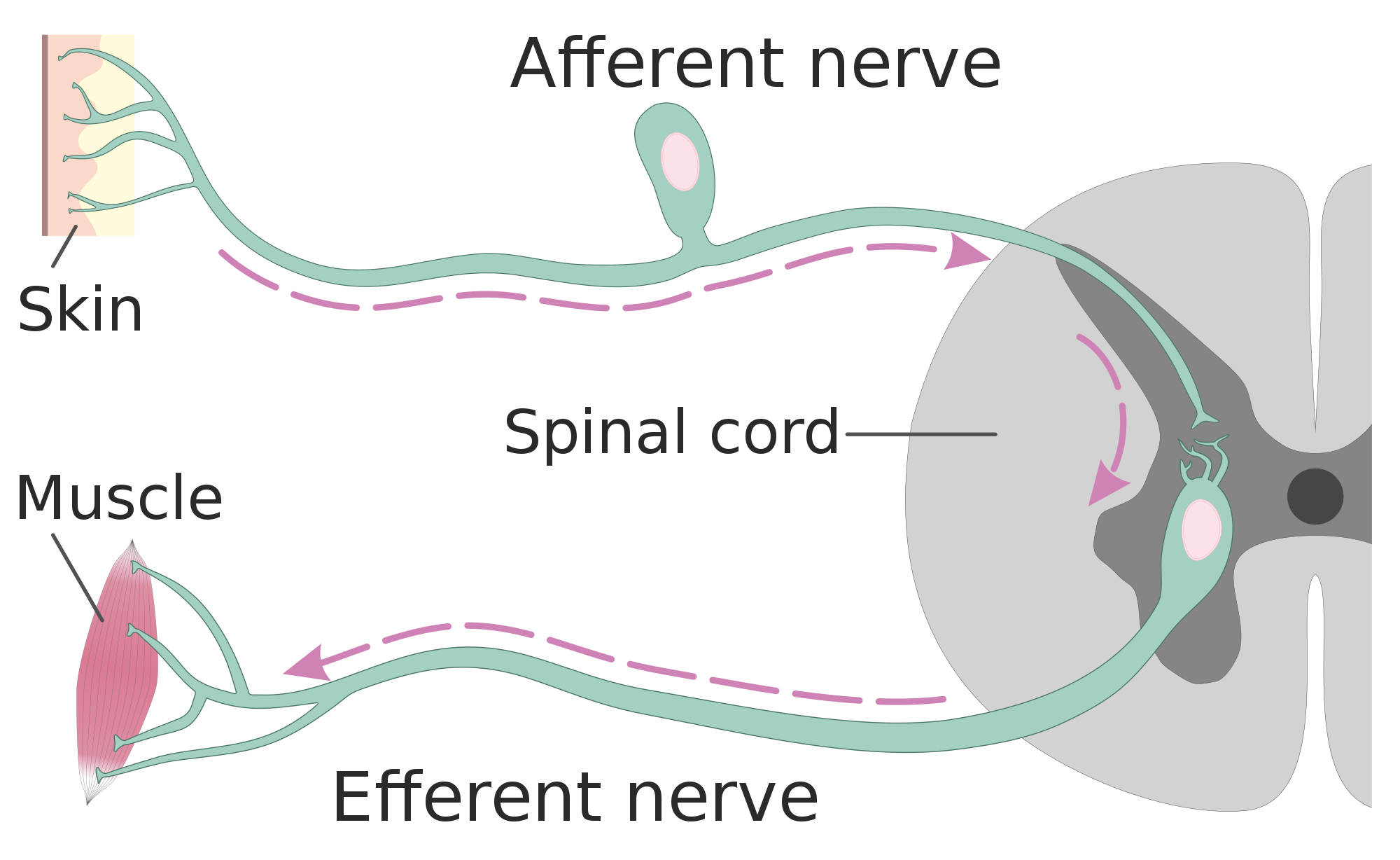

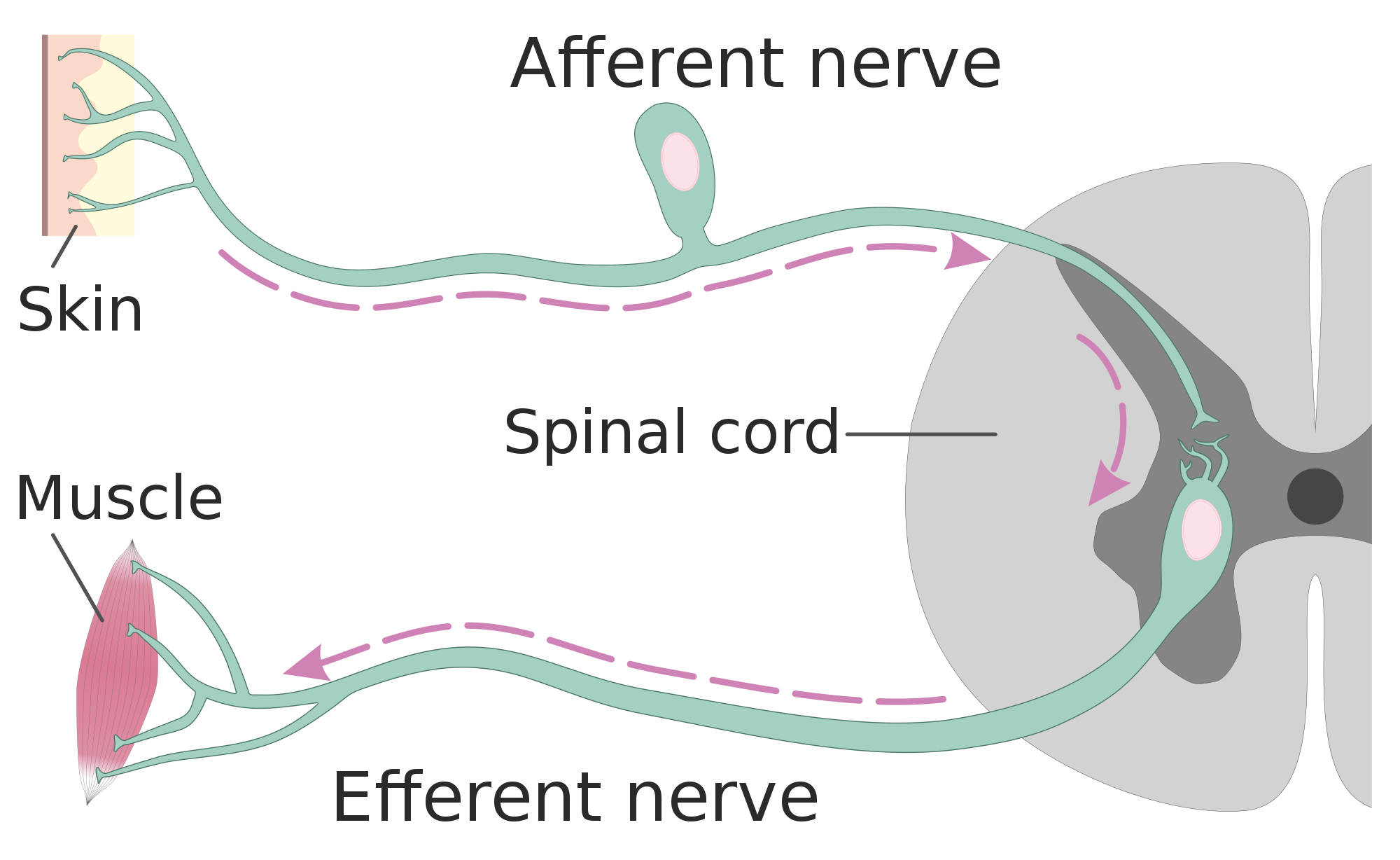

The PNS is mostly made up of cable-like bundles of axons called nerves, as well as clusters of neuronal cell bodies called ganglia (singular, ganglion). Nerves are generally classified as sensory, motor, or mixed nerves based on the direction in which they carry nerve impulses.

- Sensory nerves transmit information from sensory receptors in the body to the CNS. Sensory nerves are also called afferent nerves. You can see an example in the figure below.

- Motor nerves transmit information from the CNS to muscles, organs, and glands. Motor nerves are also called efferent nerves. You can see one in the figure below.

- Mixed nerves contain both sensory and motor neurons, so they can transmit information in both directions. They have both afferent and efferent functions.

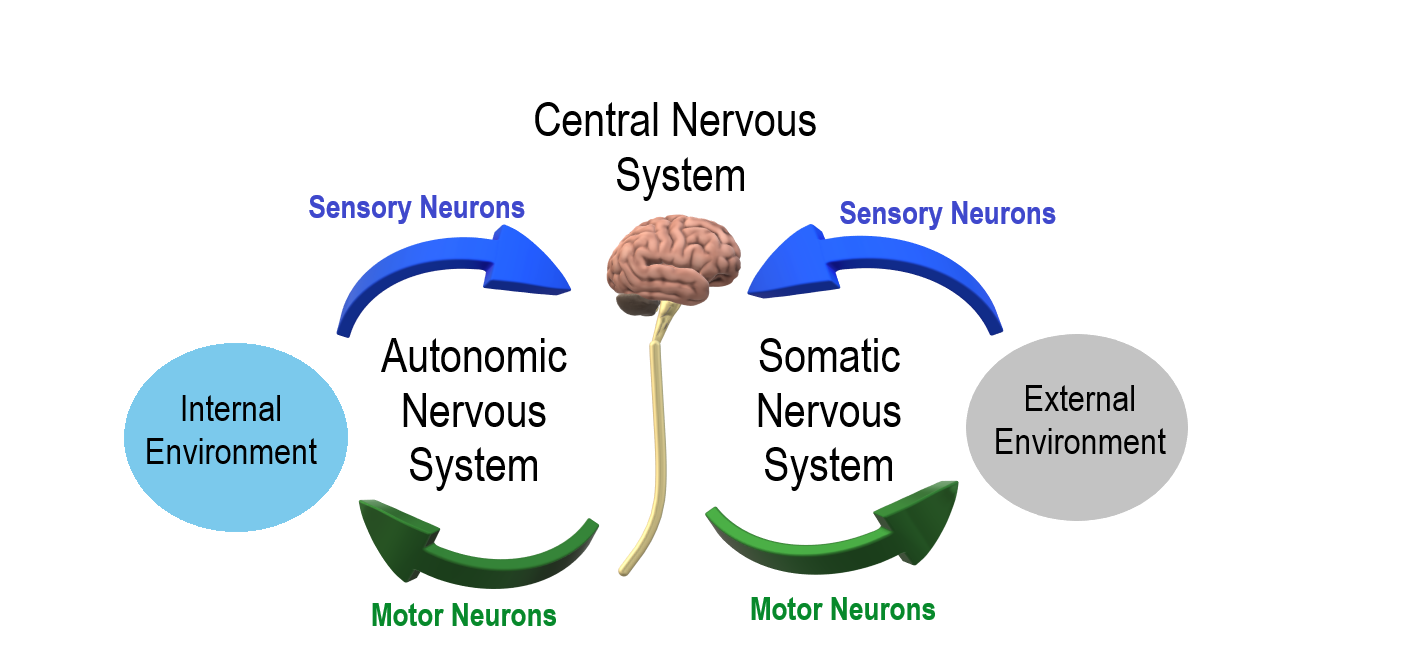

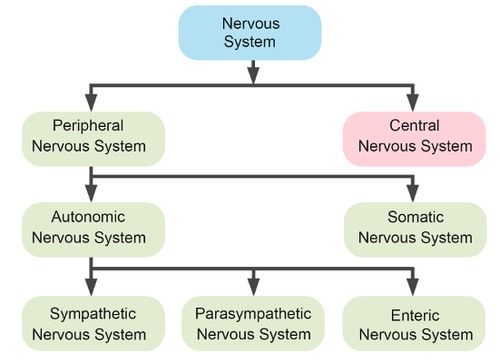

Divisions of the Peripheral Nervous System

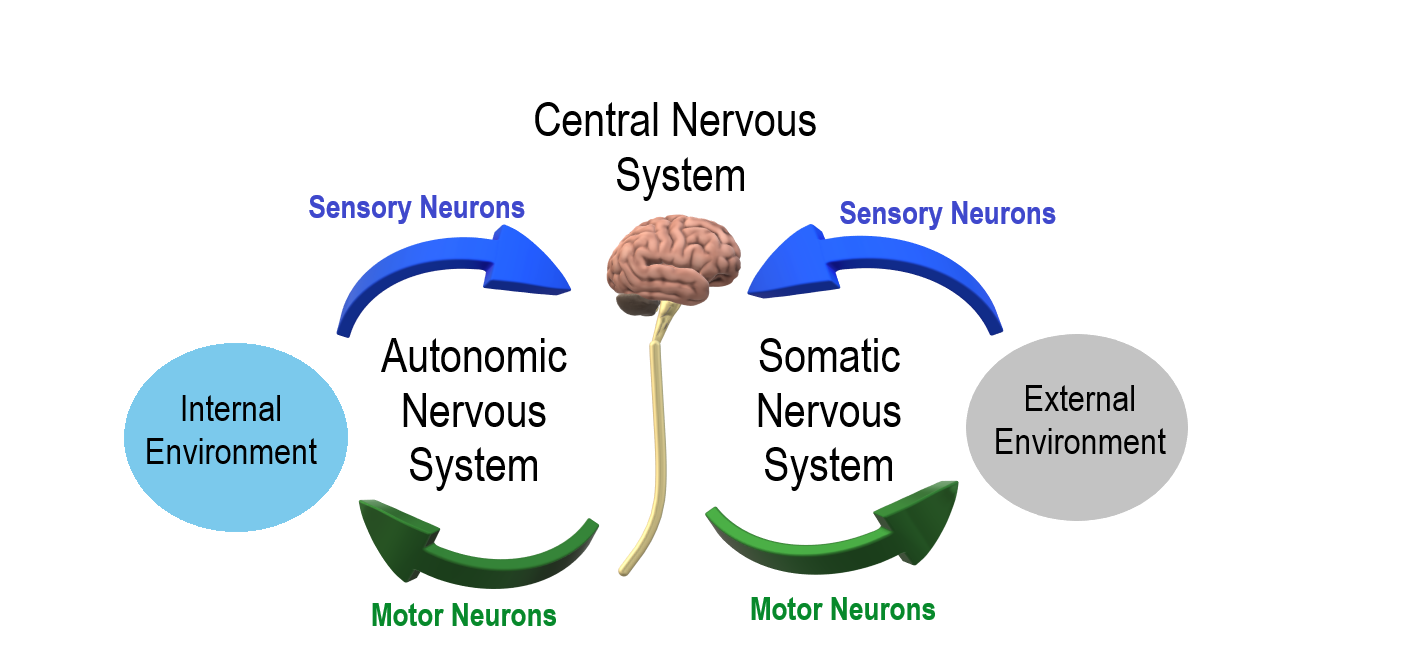

The PNS is divided into two major systems, called the autonomic nervous system and the somatic nervous system. In the diagram below, the autonomic system is shown on the left, and the somatic system on the right. Both systems of the PNS interact with the CNS and include sensory and motor neurons, but they use different circuits of nerves and ganglia.

Somatic Nervous System

The somatic nervous system primarily senses the external environment and controls voluntary activities about which decisions and commands come from the cerebral cortex of the brain. When you feel too warm, for example, you decide to turn on the air conditioner. As you walk across the room to the thermostat, you are using your somatic nervous system. In general, the somatic nervous system is responsible for all of your conscious perceptions of the outside world, as well as all of the voluntary motor activities you perform in response. Whether it’s playing a piano, driving a car, or playing basketball, you can thank your somatic nervous system for making it possible.

Somatic sensory and motor information is transmitted through 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. Cranial nerves are in the head and neck and connect directly to the brain. Sensory components of cranial nerves transmit information about smells, tastes, light, sounds, and body position. Motor components of cranial nerves control skeletal muscles of the face, tongue, eyeballs, throat, head, and shoulders. Motor components of cranial nerves also control the salivary glands and swallowing. Four of the 12 cranial nerves participate in both sensory and motor functions as mixed nerves, having both sensory and motor neurons.

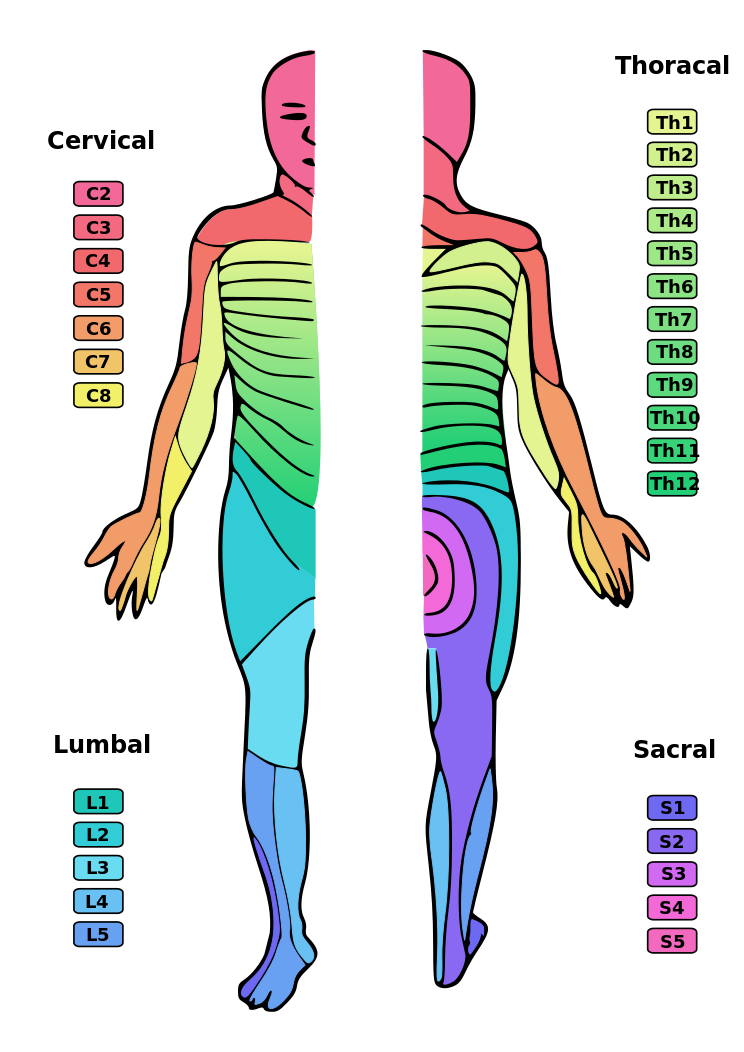

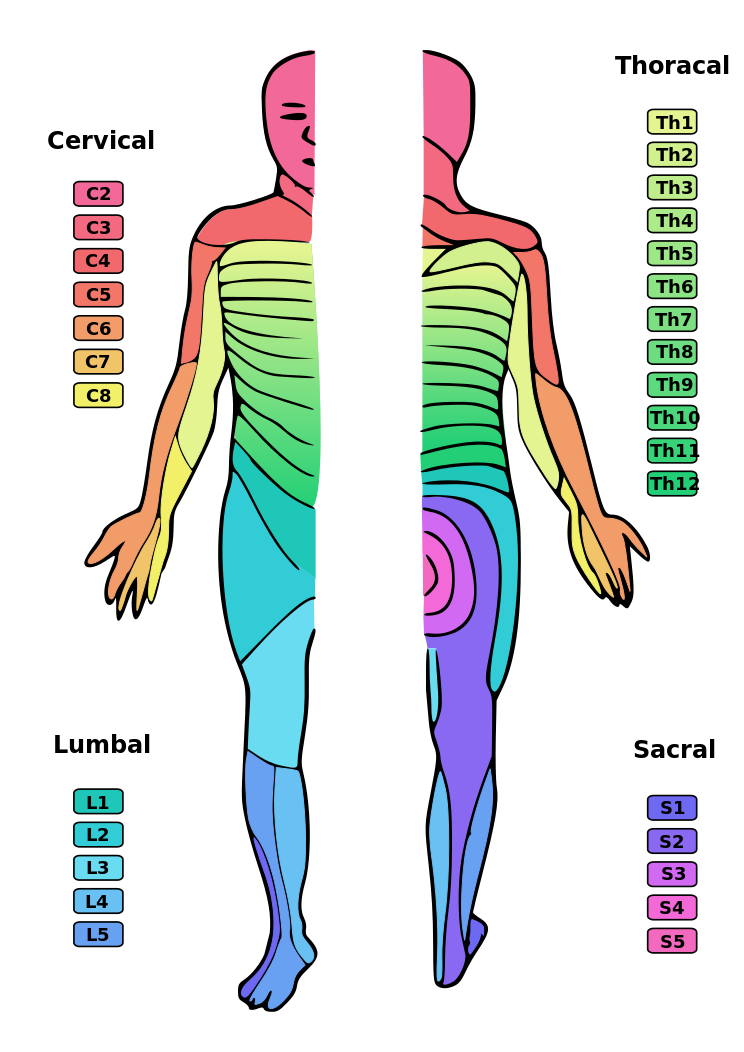

Spinal nerves emanate from the spinal column between vertebrae. All of the spinal nerves are mixed nerves, containing both sensory and motor neurons. The areas of skin innervated by the 31 pairs of spinal nerves are shown in the figure below. These include sensory nerves in the skin that sense pressure, temperature, vibrations, and pain. Other sensory nerves are in the muscles, and they sense stretching and tension. Spinal nerves also include motor nerves that stimulate skeletal muscles to contract, allowing for voluntary body movements.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system primarily senses the internal environment and controls involuntary activities. It is responsible for monitoring conditions in the internal environment and bringing about appropriate changes in them. In general, the autonomic nervous system is responsible for all the activities that go on inside your body without your conscious awareness or voluntary participation.

Structurally, the autonomic nervous system consists of sensory and motor nerves that run between the CNS (especially the hypothalamus in the brain), internal organs (such as the heart, lungs, and digestive organs), and glands (such as the pancreas and sweat glands). Sensory neurons in the autonomic system detect internal body conditions and send messages to the brain. Motor nerves in the autonomic system affect appropriate responses by controlling contractions of smooth or cardiac muscle, or glandular tissue. For example, when sensory nerves of the autonomic system detect a rise in body temperature, motor nerves signal smooth muscles in blood vessels near the body surface to undergo vasodilation, and the sweat glands in the skin to secrete more sweat to cool the body.

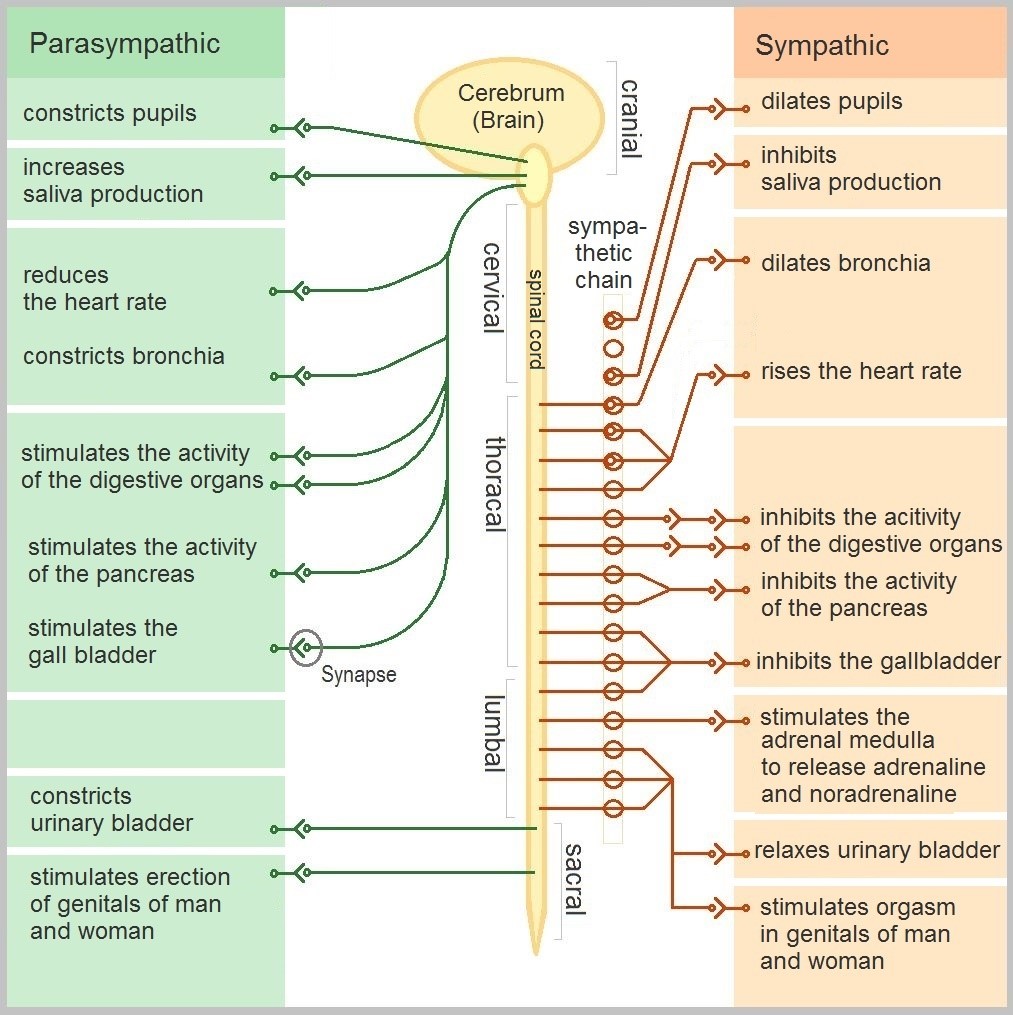

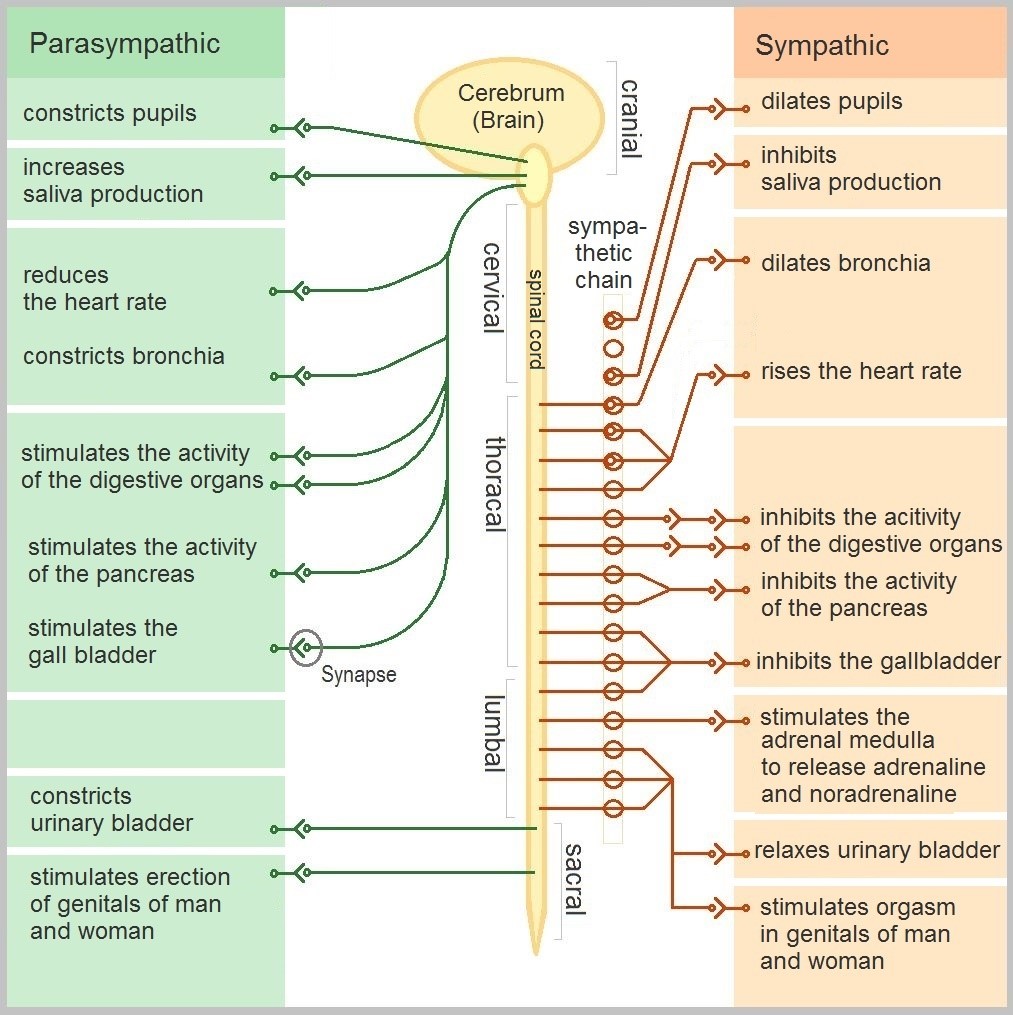

The autonomic nervous system, in turn, has three subdivisions: the sympathetic division, parasympathetic division, and enteric division. The first two subdivisions of the autonomic system are summarized in the figure below. Both affect the same organs and glands, but they generally do so in opposite ways.

- The sympathetic division controls the fight-or-flight response. Changes occur in organs and glands throughout the body that prepare the body to fight or flee in response to a perceived danger. For example, the heart rate speeds up, air passages in the lungs become wider, more blood flows to the skeletal muscles, and the digestive system temporarily shuts down.

- The parasympathetic division returns the body to normal after the fight-or-flight response has occurred. For example, it slows down the heart rate, narrows air passages in the lungs, reduces blood flow to the skeletal muscles, and stimulates the digestive system to start working again. The parasympathetic division also maintains internal homeostasis of the body at other times.

- The enteric division is made up of nerve fibres that supply the organs of the digestive system. This division allows for the local control of many digestive functions.

Disorders of the Peripheral Nervous System

Unlike the CNS — which is protected by bones, meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid — the PNS has no such protections. The PNS also has no blood-brain barrier to protect it from toxins and pathogens in the blood. Therefore, the PNS is more subject to injury and disease than is the CNS. Causes of nerve injury include diabetes, infectious diseases (such as shingles), and poisoning by toxins (such as heavy metals). PNS disorders often have symptoms like loss of feeling, tingling, burning sensations, or muscle weakness. If a traumatic injury results in a nerve being transected (cut all the way through), it may regenerate, but this is a very slow process and may take many months.

Two other diseases of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

- Guillain-Barre syndrome is a rare disease in which the immune system attacks nerves of the PNS, leading to muscle weakness and even paralysis. The exact cause of Guillain-Barre syndrome is unknown, but it often occurs after a viral or bacterial infection. There is no known cure for the syndrome, but most people eventually make a full recovery. Recovery can be slow, however, lasting anywhere from several weeks to several years.

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is a hereditary disorder of the nerves, and one of the most common inherited neurological disorders. It affects predominantly the nerves in the feet and legs, and often in the hands and arms, as well. The disease is characterized by loss of muscle tissue and sense of touch. It is presently incurable.

Feature: My Human Body

The autonomic nervous system is considered to be involuntary because it doesn't require conscious input. However, it is possible to exert some voluntary control over it. People who practice yoga or other so-called mind-body techniques, for example, can reduce their heart rate and certain other autonomic functions. Slowing down these otherwise involuntary responses is a good way to relieve stress and reduce the wear-and-tear that stress can place on the body. Such techniques may also be useful for controlling post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Three types of integrative practices for these purposes are breathing exercises, body-based tension modulation exercises, and mindfulness techniques.

Breathing exercises can help control the rapid, shallow breathing that often occurs when you are anxious or under stress. These exercises can be learned quickly, and they provide immediate feelings of relief. Specific breathing exercises include paced breath, diaphragmatic breathing, and Breathe2Relax or Chill Zone on MindShift™ CBT, which are downloadable breathing practice mobile applications, or "Apps". Try syncing your breathing with Eric Klassen's "Triangle breathing, 1 minute" video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9Q8D6n-3qw

Triangle breathing, 1 minute, Erin Klassen, 2015.

Body-based tension modulation exercises include yoga postures (also known as “asanas”) and tension manipulation exercises. The latter include the Trauma/Tension Release Exercise (TRE) and the Trauma Resiliency Model (TRM). Watch this video for a brief — but informative — introduction to the TRE program:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67R974D8swM&feature=youtu.be

TRE® : Tension and Trauma Releasing Exercises, an Introduction with Jessica Schaffer, Jessica Schaffer Nervous System RESET, 2015.

Mindfulness techniques have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression, as well as those of anxiety and stress. They have also been shown to be useful for pain management and performance enhancement. Specific mindfulness programs include Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness Mind-Fitness Training (MMFT). You can learn more about MBSR by watching the video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TA7P-iCCcY&feature=youtu.be

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness), Palouse Mindfulness, 2017.

8.6 Summary

- The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside the central nervous system (CNS). Its main function is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism.

- The PNS is made up of nerves and ganglia. Nerves are bundles of axons, and ganglia are groups of cell bodies. Nerves are classified as sensory, motor, or a mix of the two.

- The PNS is divided into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic system controls voluntary activities, whereas the autonomic system controls involuntary activities.

- The autonomic nervous system is further divided into sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric divisions. The sympathetic division controls fight-or-flight responses during emergencies, the parasympathetic system controls routine body functions the rest of the time, and the enteric division provides local control over the digestive system.

- The PNS is not as well protected physically or chemically as the CNS, so it is more prone to injury and disease. PNS problems include injury from diabetes, shingles, and heavy metal poisoning. Two disorders of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

8.6 Review Questions

- Describe the general structure of the peripheral nervous system. State its primary function.

- What are ganglia?

- Identify three types of nerves based on the direction in which they carry nerve impulses.

- Outline all of the divisions of the peripheral nervous system.

- Compare and contrast the somatic and autonomic nervous systems.

- When and how does the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system affect the body?

- What is the function of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system? Specifically, how does it affect the body?

- Name and describe two peripheral nervous system disorders.

- Give one example of how the CNS interacts with the PNS to control a function in the body.

- For each of the following types of information, identify whether the neuron carrying it is sensory or motor, and whether it is most likely in the somatic or autonomic nervous system:

- Visual information

- Blood pressure information

- Information that causes muscle contraction in digestive organs after eating

- Information that causes muscle contraction in skeletal muscles based on the person’s decision to make a movement

-

8.6 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySIDMU2cy0Y&feature=emb_logo

Phantom Limbs Explained, Plethrons, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=73yo5nJne6c&feature=emb_logo

Why Do Hot Peppers Cause Pain? Reactions, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 8.6.1

Kid’s piant duet by PJMixer on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/) license.

Figure 8.6.2

Nervous_system_diagram by ¤~Persian Poet Gal on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.6.3

Afferent_and_efferent_neurons_en.svg by Helixitta on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 8.6.4

Autonomic and Somatic Nervous System by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 8.6.5

Dermatoms.svg by Ralf Stephan (mailto:ralf@ark.in-berlin.de) on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.6.6

The_Autonomic_Nervous_System by Geo-Science-International on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC0 1.0 Universal

Public Domain Dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

References

Erin Klassen. (2015, December 15). Triangle breathing, 1 minute. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9Q8D6n-3qw&feature=youtu.be

Jessica Schaffer Nervous System RESET. (2015, January 15). TRE® : Tension and trauma releasing exercises, an Introduction with Jessica Schaffer. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67R974D8swM&feature=youtu.be

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/charcot-marie-tooth-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350517

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Diabetes [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20371444

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Guillain-Barre syndrome [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/guillain-barre-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20362793

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Shingles [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/shingles/symptoms-causes/syc-20353054

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Stroke [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stroke/symptoms-causes/syc-20350113

Palouse Mindfulness. (2017, March 25). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness), YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TA7P-iCCcY&feature=youtu.be

Plethrons, (2015, March 23). Phantom limbs explained. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySIDMU2cy0Y&feature=youtu.be

Reactions. (2015, December 1). Why do hot peppers cause pain? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=73yo5nJne6c&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Art in a Cup

Who knew that a cup of coffee could also be a work of art? A talented barista can make coffee look as good as it tastes. If you are a coffee drinker, you probably know that coffee can also affect your mental state. It can make you more alert, and it may improve your concentration. That’s because the caffeine in coffee is a psychoactive drug. In fact, caffeine is the most widely consumed psychoactive substance in the world. In North America, for example, 90 per cent of adults consume caffeine daily.

What Are Psychoactive Drugs?

Psychoactive drugs are substances that change the function of the brain and result in alterations of mood, thinking, perception, and/or behavior. Psychoactive drugs may be used for many purposes, including therapeutic, ritual, or recreational purposes. Besides caffeine, other examples of psychoactive drugs include cocaine, LSD, alcohol, tobacco, codeine, and morphine. Psychoactive drugs may be legal prescription medications (codeine and morphine), legal nonprescription drugs (alcohol and tobacco), or illegal drugs (cocaine and LSD).

Cannabis (or marijuana) is also a psychoactive drug that while illegal in many countries is legal for use in Canada by individuals over the age of 19 years. Legal prescription medications (such as opioids) are also used illegally by increasingly large numbers of people. Some legal drugs, such as alcohol and nicotine, are readily available almost everywhere, as illustrated by the images below.

Figure 8.8.2 These psychoactive drugs are legal and accessible almost anywhere.

Classes of Psychoactive Drugs

Psychoactive drugs are divided into different classes based on their pharmacological effects. Several classes are listed below, along with examples of commonly used drugs in each class.

- Stimulants are drugs that stimulate the brain and increase alertness and wakefulness. Examples of stimulants include caffeine, nicotine, cocaine, and amphetamines (such as Adderall).

- Depressants are drugs that calm the brain, reduce anxious feelings, and induce sleepiness. Examples of depressants include ethanol (in alcoholic beverages) and opioids, such as codeine and heroin.

- Anxiolytics are drugs that have a tranquilizing effect and inhibit anxiety. Examples of anxiolytic drugs include benzodiazepines (such as diazepam/Valium), barbiturates (such as phenobarbital), opioids, and antidepressant drugs (such as sertraline/Zoloft).

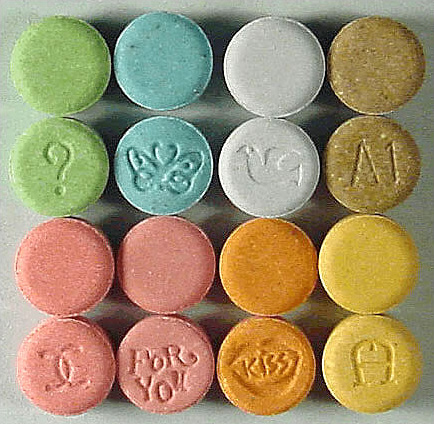

- Euphoriants are drugs that bring about a state of euphoria, or intense feelings of well-being and happiness. Examples of euphoriants include the so-called "club drug" MDMA (ecstasy), amphetamines, ethanol, and opioids (such as morphine).

- Hallucinogens are drugs that can cause hallucinations and other perceptual anomalies. They also cause subjective changes in thoughts, emotions, and consciousness. Examples of hallucinogens include LSD, mescaline, nitrous oxide, and psilocybin.

- Empathogens are drugs that produce feelings of empathy, or sympathy with other people. Examples of empathogens include amphetamines and MDMA.

Many psychoactive drugs have multiple effects, so they may be placed in more than one class. One example is MDMA, pictured below, which may act both as a euphoriant and as an empathogen. In some people, MDMA may also have stimulant or hallucinogenic effects. As of 2016, MDMA had no accepted medical uses, but it was undergoing testing for use in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and certain other types of anxiety disorders.

Mechanisms of Action

Psychoactive drugs generally produce their effects by affecting brain chemistry, which in turn may cause changes in a person’s mood, thinking, perception, and behavior. Each drug tends to have a specific action on one or more neurotransmitters or neurotransmitter receptors in the brain. Generally, they act as either agonists or antagonists.

- Agonists are drugs that increase the activity of particular neurotransmitters. They might act by promoting the synthesis of the neurotransmitters, reducing their reuptake from synapses, or mimicking their action by binding to receptors for the neurotransmitters.

- Antagonists are drugs that decrease the activity of particular neurotransmitters. They might act by interfering with the synthesis of the neurotransmitters or by blocking their receptors so the neurotransmitters cannot bind to them.

Consider the example of the neurotransmitter GABA. This is one of the most common neurotransmitters in the brain, and it normally has an inhibitory effect on cells. GABA agonists — which increase its activity — include ethanol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines, among other psychoactive drugs. All of these drugs work by promoting the activity of GABA receptors in the brain.

Uses of Psychoactive Drugs

You may have been prescribed psychoactive drugs by your doctor. For example, your doctor may have prescribed you an opioid drug, such as codeine for pain (most likely in the form of Tylenol with added codeine). Chances are you also use nonprescription psychoactive drugs (like caffeine) for mental alertness. These are just two of the many possible uses of psychoactive drugs.

Medical Uses

General anesthesia is one use of psychoactive drugs in medicine. With general anesthesia, pain is blocked and unconsciousness is induced. General anesthetics are most often used during surgical procedures and may be administered in gaseous form, as in Figure 8.8.4. General anesthetics include the drugs halothane and ketamine. Other psychoactive drugs are used to manage pain without affecting consciousness. They may be prescribed either for acute pain in cases of trauma (such as broken bones) or for chronic pain caused by arthritis, cancer, or fibromyalgia. Most often, the drugs used for pain control are opioids, such as morphine and codeine.

Many psychiatric disorders are also managed with psychoactive drugs. Antidepressants like sertraline, for example, are used to treat depression, anxiety, and eating disorders. Anxiety disorders may also be treated with anxiolytics, such as buspirone and diazepam. Stimulants (such as amphetamines) are used to treat attention deficit disorder. Antipsychotics (such as clozapine and risperidone) — as well as mood stabilizers, such as lithium — are used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Ritual Uses

Certain psychoactive drugs, particularly hallucinogens, have been used for ritual purposes since prehistoric times. For example, Native Americans have used the mescaline-containing peyote cactus (pictured in Figure 8.8.5) for religious ceremonies for as long as 5,700 years. In prehistoric Europe, the mushroom Amanita muscaria, which contains a hallucinogenic drug called muscimol, was used for similar purposes. Various other psychoactive drugs — including jimsonweed, psilocybin mushrooms, and cannabis — have also been used for millennia, by various peoples, for ritual purposes.

Recreational Uses

The recreational use of psychoactive drugs generally has the purpose of altering one’s consciousness and creating a feeling of euphoria commonly called a “high.” Some of the drugs used most commonly for recreational purposes are cannabis, ethanol (alcohol), opioids, and stimulants (such as nicotine). Hallucinogens are also used recreationally, primarily for the alterations they cause in thinking and perception.

Some investigators have suggested that the urge to alter one’s state of consciousness is a universal human drive, similar to the drive to satiate thirst, hunger, or sexual desire. They think that this instinct is even present in children, who may attain an altered state by repetitive motions, such as spinning or swinging. Some nonhuman animals also exhibit a drive to experience altered states. They may consume fermented berries or fruit and become intoxicated. The way cats respond to catnip (see Figure 8.8.6) is another example.

Addiction, Dependence, and Rehabilitation

Psychoactive substances often bring about subjective changes that the user may find pleasant (euphoria) or advantageous (increased alertness). These changes are rewarding and positively reinforcing, so they have the potential for misuse, addiction, and dependence. Addiction refers to the compulsive use of a drug, despite negative consequences that such use may entail. Sustained use of an addictive drug may produce dependence on the drug. Dependence may be physical and/or psychological. It occurs when cessation of drug use produces withdrawal symptoms. Physical dependence produces physical withdrawal symptoms, which may include tremors, pain, seizures, or insomnia. Psychological dependence produces psychological withdrawal symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, paranoia, or hallucinations.

Rehabilitation for drug dependence and addiction typically involves psychotherapy, which may include both individual and group therapy. Organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) may also be helpful for people trying to recover from addiction. These groups are self-described as international mutual aid fellowships, and their primary purpose is to help addicts achieve and maintain sobriety. In some cases, rehabilitation is aided by the temporary use of psychoactive substances that reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms without creating addiction themselves. The drug methadone, for example, is commonly used to treat heroin addiction.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

In North America, a lot of media attention is currently given to a rising tide of opioid addiction and overdose deaths. Opioids are drugs derived from the opium poppy or synthetic versions of such drugs. They include the illegal drug heroin, as well as prescription painkillers such as codeine, morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and fentanyl. In 2016, fentanyl received wide media attention when it was announced that an accidental fentanyl overdose was responsible for the death of music icon Prince. Fentanyl is an extremely strong and dangerous drug, said to be 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, making risk of overdose death from fentanyl very high.

The dramatic increase in opioid addiction and overdose deaths has been called an opioid epidemic. It is considered to be the worst drug crisis in Canadian history. Consider the following facts:

- In 2016, there were almost 2,500 opioid-related deaths in Canada — almost 7 per day.

- The number of prescriptions written for opioids quadrupled between 1999 and 2010. If you have been prescribed codeine, fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone or medical heroin, then you have been prescribed an opiate.

- There are many long-term health effects of using opioids, which include:

- Increased tolerance to the drug.

- Liver damage.

- Substance use disorder or addiction.

Doctors, public health professionals, and politicians have all called for new policies, funding, programs, and laws to address the opioid epidemic. Changes that have already been made include a shift from criminalizing to medicalizing the problem, more treatment programs, and more widespread distribution and use of the opioid-overdose antidote naloxone (Narcan). Opioids can slow or stop a person's breathing, which is what usually causes overdose deaths. Naloxone helps the person wake up and keeps them breathing until emergency medical treatment can be provided.

What, if anything, will work to stop the opioid epidemic in Canada and the United States? Keep watching the news to find out.

8.8 Summary

- Psychoactive drugs are substances that change the function of the brain and result in alterations of mood, thinking, perception, and behavior. They include prescription medications (such as opioid painkillers), legal substances (such as nicotine and alcohol), and illegal drugs (such as LSD and heroin).

- Psychoactive drugs are divided into different classes according to their pharmacological effects. They include stimulants, depressants, anxiolytics, euphoriants, hallucinogens, and empathogens. Many psychoactive drugs have multiple effects, so they may be placed in more than one class.

- Psychoactive drugs generally produce their effects by affecting brain chemistry. Generally, they act either as agonists — which enhance the activity of particular neurotransmitters — or as antagonists, which decrease the activity of particular neurotransmitters.

- Psychoactive drugs are used for various purposes, including medical, ritual, and recreational purposes.

- Misuse of psychoactive drugs may lead to addiction, which is the compulsive use of a drug despite the negative consequences such use may entail. Sustained use of an addictive drug may produce physical or psychological dependence on the drug. Rehabilitation typically involves psychotherapy, and sometimes the temporary use of other psychoactive drugs.

8.8 Review Questions

- What are psychoactive drugs?

- Identify six classes of psychoactive drugs, along with an example of a drug in each class.

- Compare and contrast psychoactive drugs that are agonists and psychoactive drugs that are antagonists.

- Describe two medical uses of psychoactive drugs.

- Give an example of a ritual use of a psychoactive drug.

- Generally speaking, why do people use psychoactive drugs recreationally?

- Define addiction.

- Identify possible withdrawal symptoms associated with physical dependence on a psychoactive drug.

- Why might a person with a heroin addiction be prescribed the psychoactive drug methadone?

- The prescription drug Prozac inhibits the reuptake of the neurotransmitter serotonin, causing more serotonin to be present in the synapse. Prozac can elevate mood, which is why it is sometimes used to treat depression. Answer the following questions about Prozac:

- Is Prozac an agonist or an antagonist for serotonin? Explain your answer.

- Is Prozac a psychoactive drug? Explain your answer.

- Name three classes of psychoactive drugs that include opioids.

- True or False: All psychoactive drugs are either illegal or available by prescription only.

- True or False: Anxiolytics might be prescribed by a physician.

- Name two drugs that activate receptors for the neurotransmitter GABA. Why do you think these drugs generally have a depressant effect?

8.8 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=foLf5Bi9qXs

How does caffeine keep us awake? - Hanan Qasim, TED-Ed, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qK0hxuXOC8

How do drugs affect the brain? - Sara Garofalo, TED-Ed, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nlcr1jd_Tok

Is marijuana bad for your brain? - Anees Bahji, TED-Ed, 2019.

Attributions

Figure 8.8.1

Cappucino Art by drew-coffman-tZKwLRO904E [photo] by Drew Coffman on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 8.8.2

- 3804, Saint-Laurent, Montreal - Cannabis Culture shop by Exile on Ontario St (Montreal, Canada) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en) license.

- Drive Through Cigarette Store by Cosmo Spacely on Flickr is used under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

- Franklin-Nicollet Liquors by Max Sparber on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 8.8.3

Ecstasy_monogram by Drug Enforcement Administration on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.8.4

US Navy 030513-N-1577S-001 Lt. Cmdr. Joe Casey, Ship's Anesthetist, trains on anesthetic procedures with Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class Eric Wichman aboard USS Nimitz (CVN 68) by U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate Airman Timothy F. Sosais on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.8.5

Peyote Lophophora_williamsii_pm by Peter A. Mansfeld on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 8.8.6

Cat under effects of catnip/Self Indulgence by Katieb50 on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. (n.d.). Regional correspondent U.S. and Canada [website]. https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/regional-correspondent-us-and-canada

Belzak, L., & Halverson, J. (2018). The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. La crise des opioïdes au Canada : une perspective nationale. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada : research, policy and practice, 38(6), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.6.02

British Columbia Regional Service Committee of Narcotics Anonymous. (n.d.). Welcome to the B.C. region of N.A. [website]. https://www.bcrna.ca/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011 November 4). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR),60(43):1487-1492. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm

TED-Ed. (2017, June 29). How do drugs affect the brain? - Sara Garofalo. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qK0hxuXOC8&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2017, July 17). How does caffeine keep us awake? - Hanan Qasim. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=foLf5Bi9qXs&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2019, December 2). Is marijuana bad for your brain? - Anees Bahji. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nlcr1jd_Tok&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study Conclusion: Fading Memory

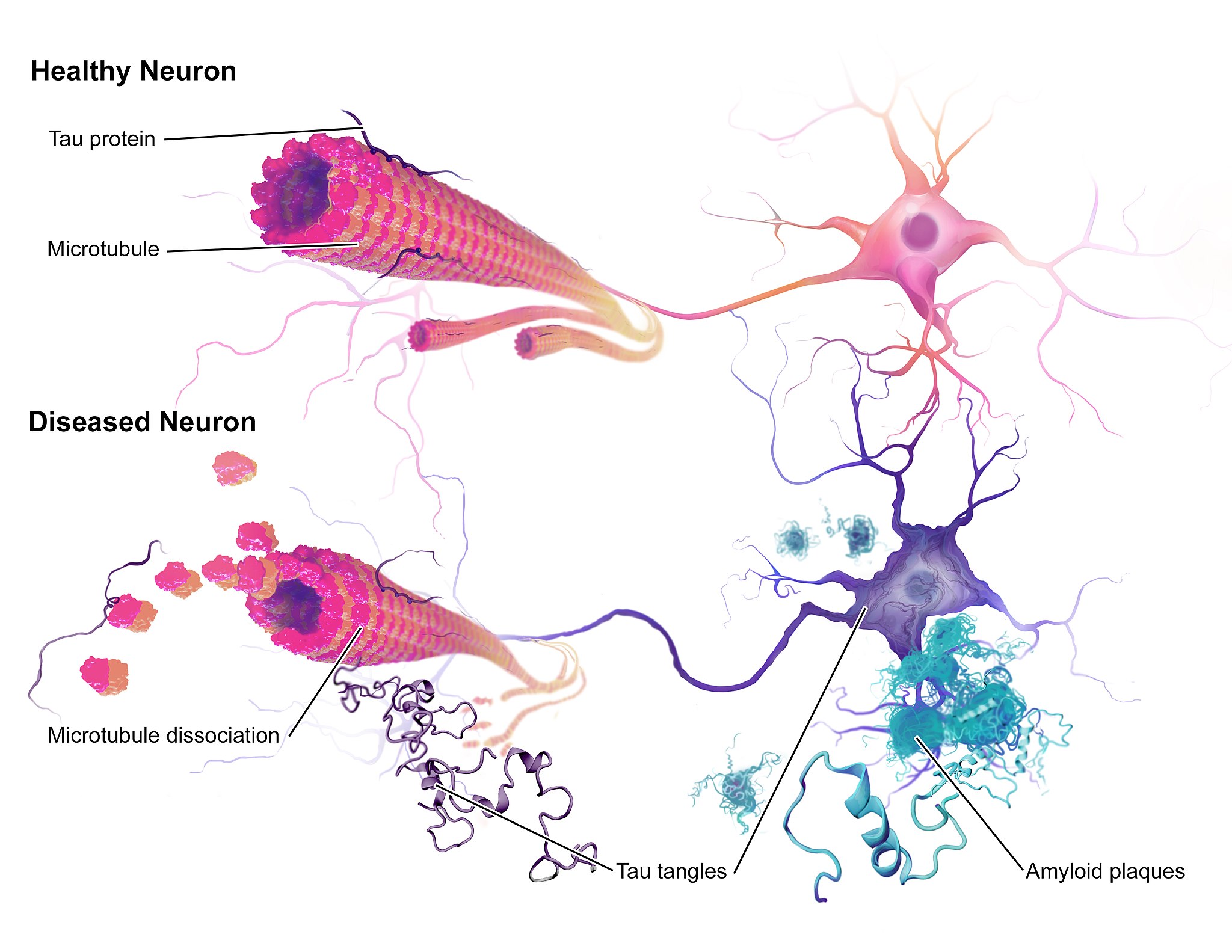

The illustration above (Figure 8.9.1) shows some of the molecular and cellular changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Rosa was diagnosed with AD at the beginning of this chapter after experiencing memory problems and other changes in her cognitive functioning, mood, and personality. These abnormal changes in the brain include the development of amyloid plaques between brain cells and neurofibrillary tangles inside of neurons. These hallmark characteristics of AD are associated with the loss of synapses between neurons, and ultimately the death of neurons.

After reading this chapter, you should have a good appreciation for the importance of keeping neurons alive and communicating with each other at synapses. The nervous system coordinates all of the body’s voluntary and involuntary activities. It interprets information from the outside world through sensory systems, and makes appropriate responses through the motor system, through communication between the PNS and CNS. The brain directs the rest of the nervous system and controls everything from basic vital functions (such as heart rate and breathing) to high-level functions (such as problem solving and abstract thought). The nervous system can perform these important functions by generating action potentials in neurons in response to stimulation and sending messages between cells at synapses, typically using chemical neurotransmitter molecules. When neurons are not functioning properly, lose their synapses, or die, they cannot carry out the signaling essential for the proper functioning of the nervous system.

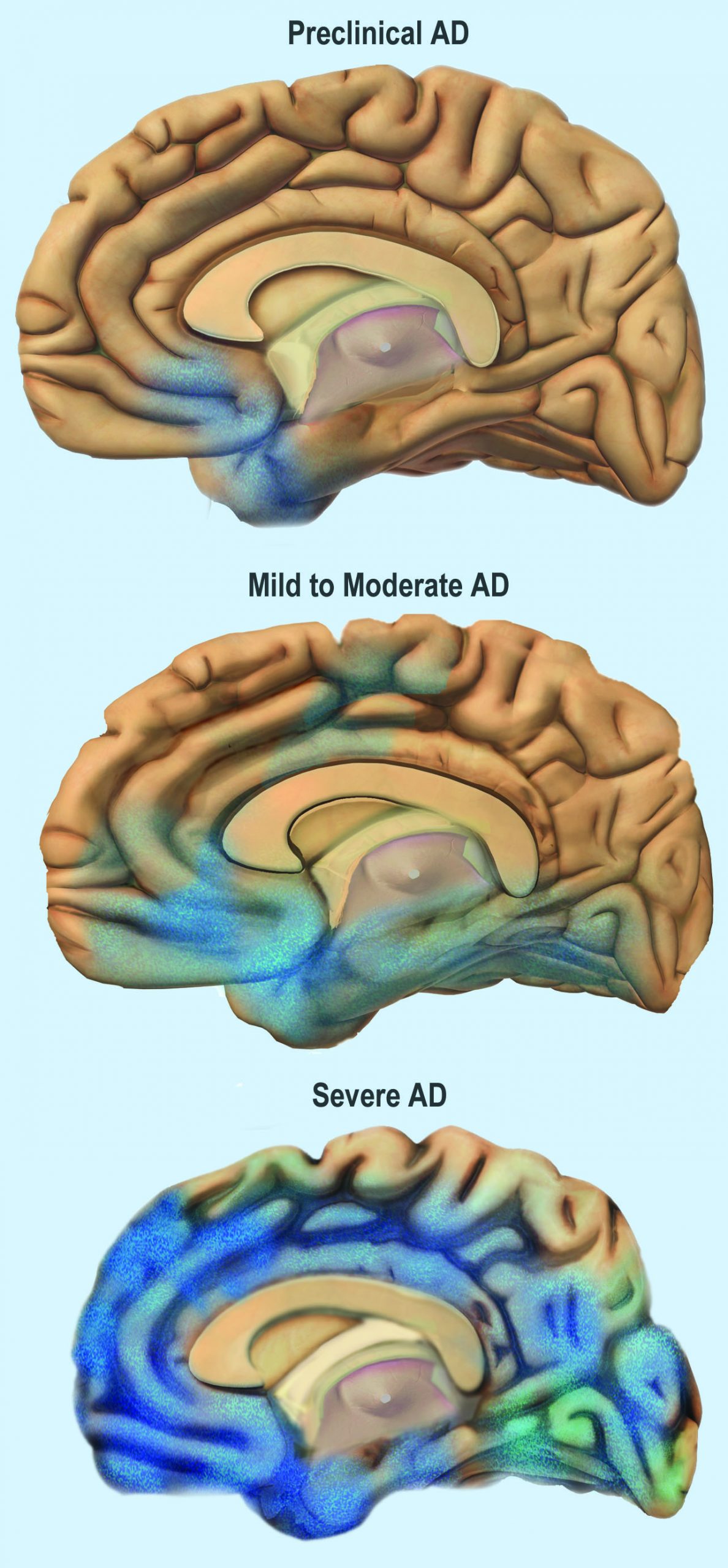

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, meaning that the damage to the brain becomes more extensive as time goes on. The picture in Figure 8.9.2 illustrates how the damage progresses from before AD is diagnosed (preclinical AD), to mild and moderate AD, to severe AD.

You can see that the damage starts in a relatively small location toward the bottom of the brain. One of the earliest brain areas to be affected by AD is the hippocampus. As you have learned, the hippocampus is important for learning and memory, which explains why many of Rosa’s symptoms of mild AD involve deficits in memory, such as trouble remembering where she placed objects, recent conversations, and appointments.

As AD progresses, more of the brain is affected, including areas involved in emotional regulation, social behavior, planning, language, spatial navigation, and higher-level thought. Rosa is beginning to show signs of problems in these areas, including irritability, lashing out at family members, getting lost in her neighborhood, problems finding the right words, putting objects in unusual locations, and difficulty in managing her finances. You can see that as AD progresses, damage spreads further across the cerebrum, which you now know controls conscious functions like reasoning, language, and interpretation of sensory stimuli. You can also see how the frontal lobe — which controls executive functions such as planning, self-control, and abstract thought — becomes increasingly damaged.

Increasing damage to the brain causes corresponding deficits in functioning. In moderate AD, patients have increased memory, language, and cognitive deficits, compared to mild AD. They may not recognize their own family members, and may wander and get lost, engage in inappropriate behaviors, become easily agitated, and have trouble carrying out daily activities such as dressing. In severe AD, much of the brain is affected. Patients usually cannot recognize family members or communicate, and they are often fully dependent on others for their care. They begin to lose the ability to control their basic functions, such as bladder control, bowel control, and proper swallowing. Eventually, AD causes death, usually as a result of this loss of basic functions.

For now, Rosa only has mild AD and is still able to function relatively well with care from her family. The medication her doctor gave her has helped improve some of her symptoms. It is a cholinesterase inhibitor, which blocks an enzyme that normally degrades the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. With more of the neurotransmitter available, more of it can bind to neurotransmitter receptors on postsynaptic cells. Therefore, this drug acts as an agonist for acetylcholine, which enhances communication between neurons in Rosa’s brain. This increase in neuronal communication can help restore some of the functions lost in early Alzheimer’s disease and may slow the progression of symptoms.

But medication such as this is only a short-term measure, and does not halt the progression of the underlying disease. Ideally, the damaged or dead neurons would be replaced by new, functioning neurons. Why does this not happen automatically in the body? As you have learned, neurogenesis is very limited in adult humans, so once neurons in the brain die, they are not normally replaced to any significant extent. Scientists, however, are studying the ways in which neurogenesis might be increased in cases of disease or injury to the brain. They are also investigating the possibility of using stem cell transplants to replace damaged or dead neurons with new neurons. But this research is in very early stages and is not currently a treatment for AD.

One promising area of research is in the development of methods to allow earlier detection and treatment of AD, given that the changes in the brain may actually start ten to 20 years before diagnosis of AD. A radiolabeled chemical called Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) binds to amyloid plaques in the brain, and in the future, it may be used in conjunction with brain imaging techniques to detect early signs of AD. Scientists are also looking for biomarkers in bodily fluids (such as blood and cerebrospinal fluid) that might indicate the presence of AD before symptoms appear. Finally, researchers are also investigating possible early and subtle symptoms (such as changes in how people move or a loss of smell) to see whether they can be used to identify people who will go on to develop AD. This research is in the early stages, but the hope is that patients can be identified earlier, allowing for earlier and more effective treatment, as well as more planning time for families.

Scientists are also still trying to fully understand the causes of AD, which affects more than five million Americans. Some genetic mutations have been identified as contributors, but environmental factors also appear to be important. With more research into the causes and mechanisms of AD, hopefully a cure can be found, and people like Rosa can live a longer and better life.

Chapter 8 Summary

In this chapter, you learned about the human nervous system. Specifically, you learned that:

- The nervous system is the organ system that coordinates all of the body’s voluntary and involuntary actions by transmitting signals to and from different parts of the body. It has two major divisions: the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

- The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord.

- The PNS consists mainly of nerves that connect the CNS with the rest of the body. It has two major divisions: the somatic nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. These divisions control different types of functions, and often interact with the CNS to carry out these functions. The somatic system controls activities that are under voluntary control. The autonomic system controls activities that are involuntary.

- The autonomic nervous system is further divided into the sympathetic division (which controls the fight-or-flight response), the parasympathetic division (which controls most routine involuntary responses), and the enteric division (which provides local control for digestive processes).

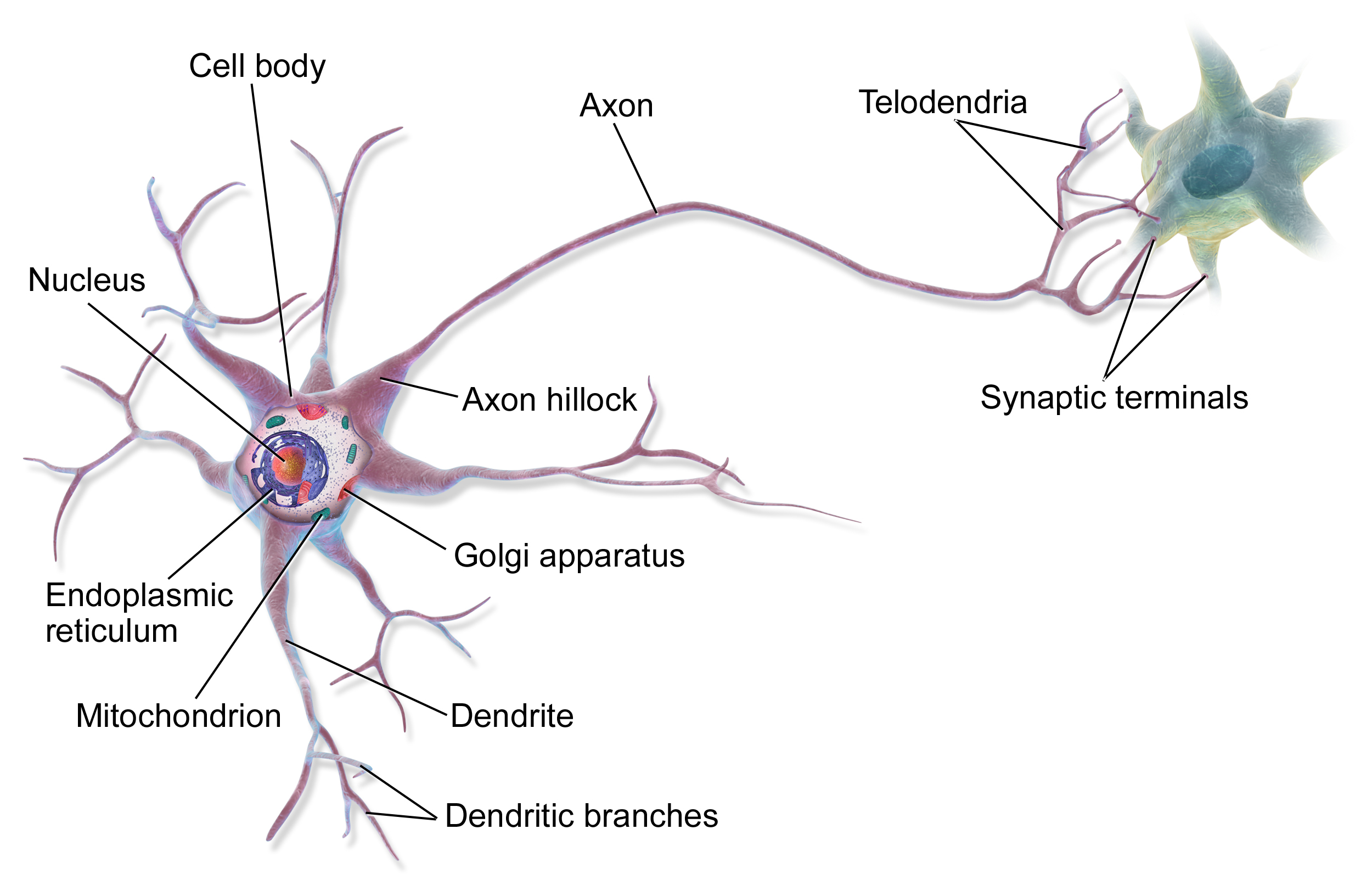

- Signals sent by the nervous system are electrical signals called nerve impulses. They are transmitted by special, electrically excitable cells called neurons, which are one of two major types of cells in the nervous system.

- Neuroglia are the other major type of nervous system cells. There are many types of glial cells, and they have many specific functions. In general, neuroglia function to support, protect, and nourish neurons.

- The main parts of a neuron include the cell body, dendrites, and axon. The cell body contains the nucleus. Dendrites receive nerve impulses from other cells, and the axon transmits nerve impulses to other cells at axon terminals. A synapse is a complex membrane junction at the end of an axon terminal that transmits signals to another cell.

- Axons are often wrapped in an electrically-insulating myelin sheath, which is produced by oligodendrocytes or schwann cells, both of which are types of neuroglia. Electrical impulses called action potentials occur at gaps in the myelin sheath, called nodes of Ranvier, which speeds the conduction of nerve impulses down the axon.

- Neurogenesis, or the formation of new neurons by cell division, may occur in a mature human brain — but only to a limited extent.

- The nervous tissue in the brain and spinal cord consists of gray matter — which contains mainly unmyelinated cell bodies and dendrites of neurons — and white matter, which contains mainly myelinated axons of neurons. Nerves of the peripheral nervous system consist of long bundles of myelinated axons that extend throughout the body.

- There are hundreds of types of neurons in the human nervous system, but many can be classified on the basis of the direction in which they carry nerve impulses. Sensory neurons carry nerve impulses away from the body and toward the central nervous system, motor neurons carry them away from the central nervous system and toward the body, and interneurons often carry them between sensory and motor neurons.

- A nerve impulse is an electrical phenomenon that occurs because of a difference in electrical charge across the plasma membrane of a neuron.

- The sodium-potassium pump maintains an electrical gradient across the plasma membrane of a neuron when it is not actively transmitting a nerve impulse. This gradient is called the resting potential of the neuron.

- An action potential is a sudden reversal of the electrical gradient across the plasma membrane of a resting neuron. It begins when the neuron receives a chemical signal from another cell or some other type of stimulus. The action potential travels rapidly down the neuron’s axon as an electric current.

- A nerve impulse is transmitted to another cell at either an electrical or a chemical synapse. At a chemical synapse, neurotransmitter chemicals are released from the presynaptic cell into the synaptic cleft between cells. The chemicals travel across the cleft to the postsynaptic cell and bind to receptors embedded in its membrane.

- There are many different types of neurotransmitters. Their effects on the postsynaptic cell generally depend on the type of receptor they bind to. The effects may be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory in more complex ways. Both physical and mental disorders may occur if there are problems with neurotransmitters or their receptors.

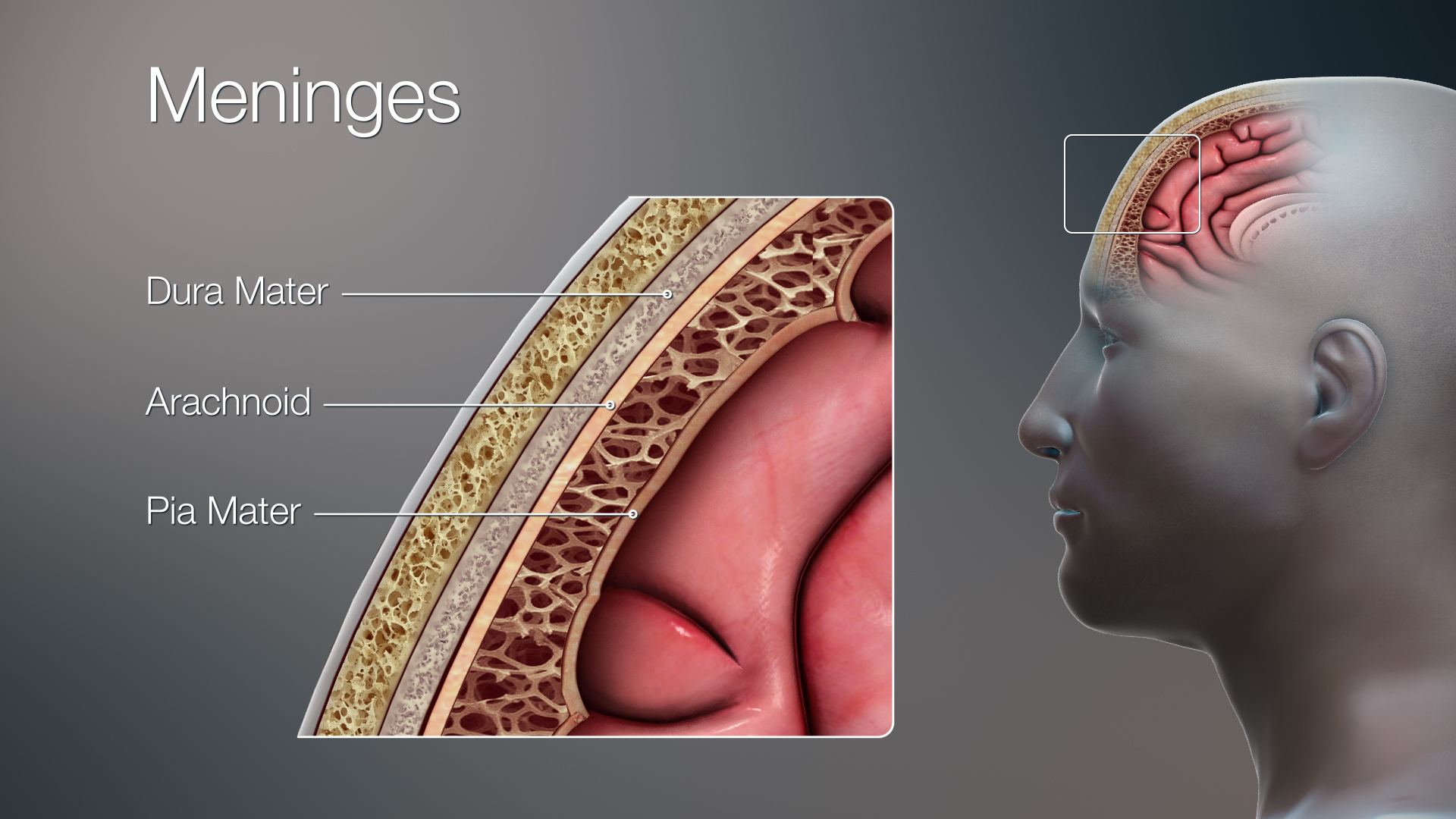

- The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord. It is physically protected by bones, meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid. It is chemically protected by the blood-brain barrier.

- The brain is the control center of the nervous system and of the entire organism. The brain uses a relatively large proportion of the body’s energy, primarily in the form of glucose.

-

- The brain is divided into three major parts, each with different functions: the forebrain, the midbrain and the hindbrain.

- The forebrain includes the cerebrum, the thalamus, the hypothalamus, the hippocampus and the amygdala. The cerebrum is further divided into left and right hemispheres. Each hemisphere has four lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. Each lobe is associated with specific senses or other functions. The cerebrum has a thin outer layer called the cerebral cortex. Its many folds give it a large surface area. This is where most information processing takes place.

- The thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala are all part of the limbic system which helps regulate memories, coordination and attention

- The brain is divided into three major parts, each with different functions: the forebrain, the midbrain and the hindbrain.

- The spinal cord is a tubular bundle of nervous tissues that extends from the head down the middle of the back to the pelvis. It functions mainly to connect the brain with the PNS. It also controls certain rapid responses called reflexes without input from the brain.

- A spinal cord injury may lead to paralysis (loss of sensation and movement) of the body below the level of the injury, because nerve impulses can no longer travel up and down the spinal cord beyond that point.

- The PNS consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside of the CNS. Its main function is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism.

- The tissues that make up the PNS are nerves and ganglia. Nerves are bundles of axons and ganglia are groups of cell bodies. Nerves are classified as sensory, motor, or a mix of the two.

- The PNS is not as well protected physically or chemically as the CNS, so it is more prone to injury and disease. PNS problems include injury from diabetes, shingles, and heavy metal poisoning. Two disorders of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

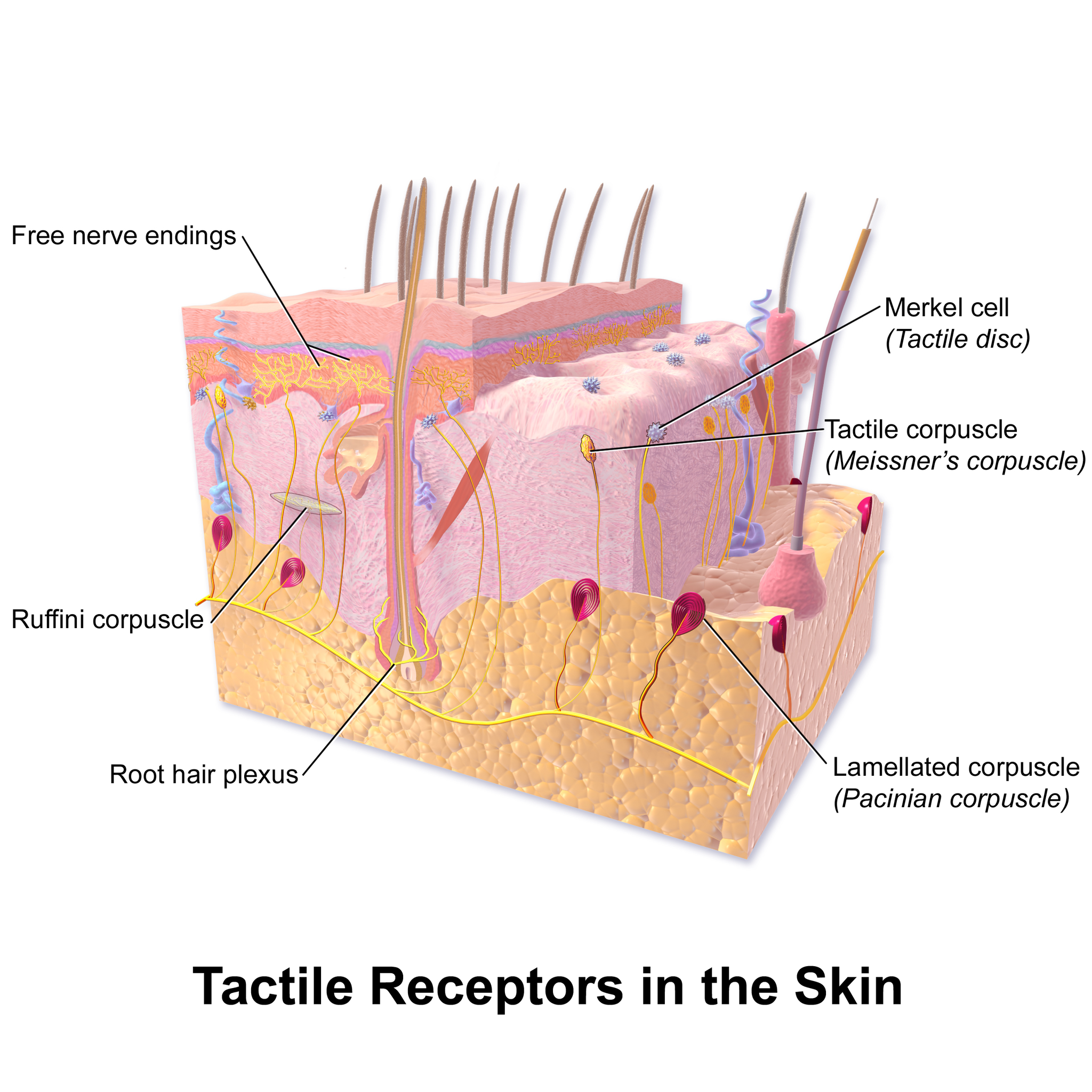

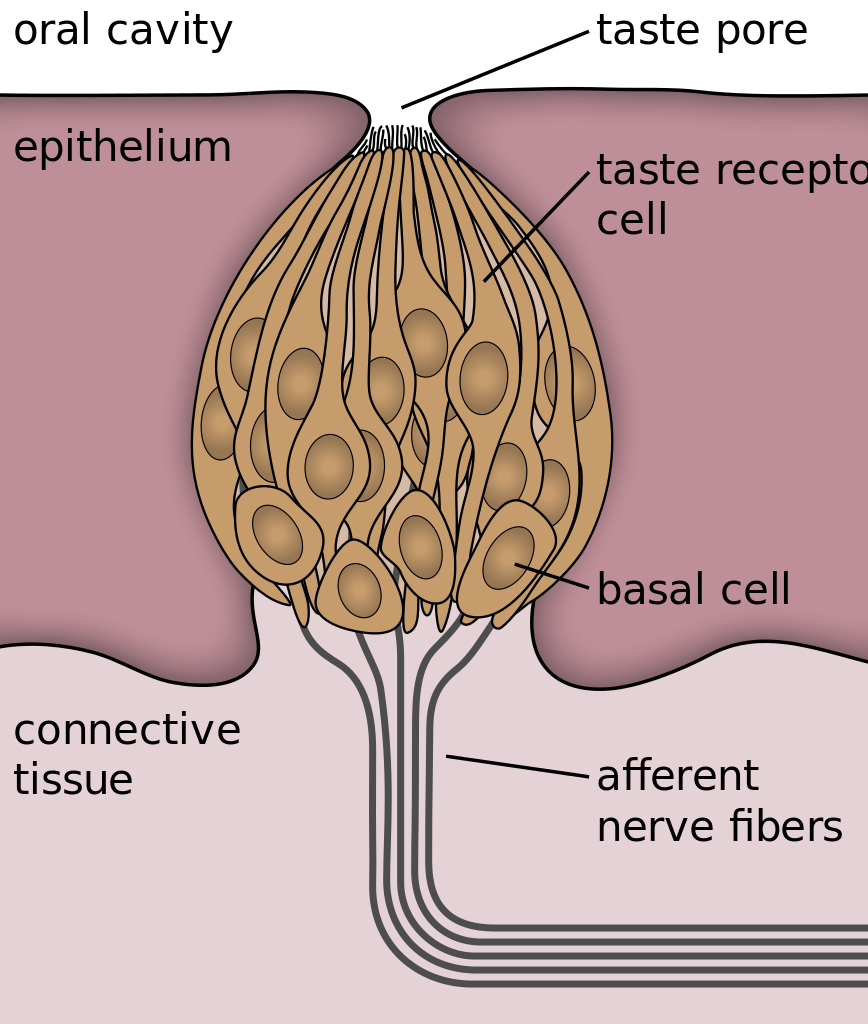

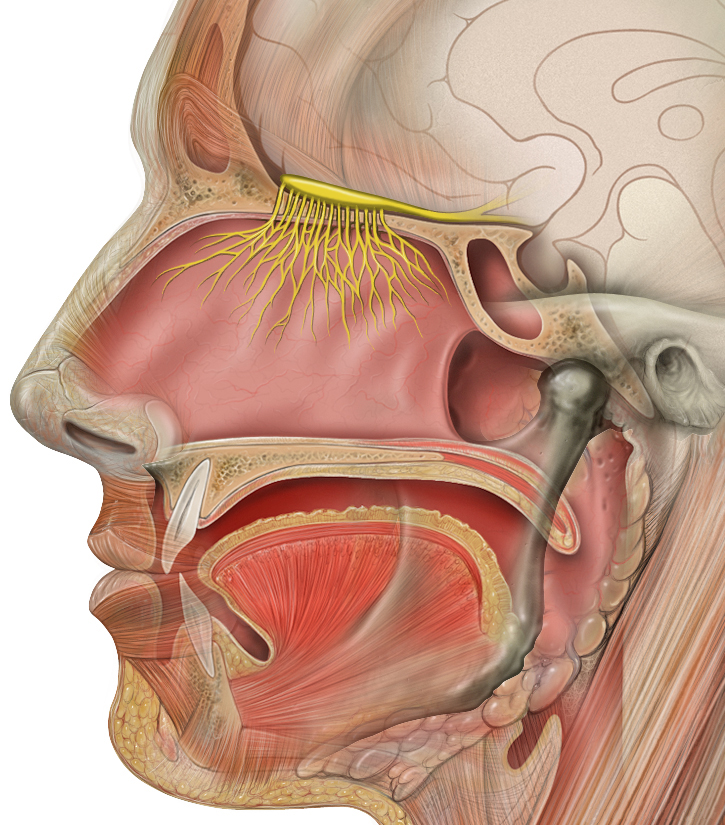

- The human body has two major types of senses: special senses and general senses. Special senses have specialized sense organs and include vision (eyes), hearing (ears), balance (ears), taste (tongue), and smell (nasal passages). General senses are all associated with touch and lack special sense organs. Touch receptors are found throughout the body but particularly in the skin.

- All senses depend on sensory receptor cells to detect sensory stimuli and transform them into nerve impulses. Types of sensory receptors include mechanoreceptors (mechanical forces), thermoreceptors (temperature), nociceptors (pain), photoreceptors (light), and chemoreceptors (chemicals).

- Touch includes the ability to sense pressure, vibration, temperature, pain, and other tactile stimuli. The skin includes several different types of touch receptor cells.

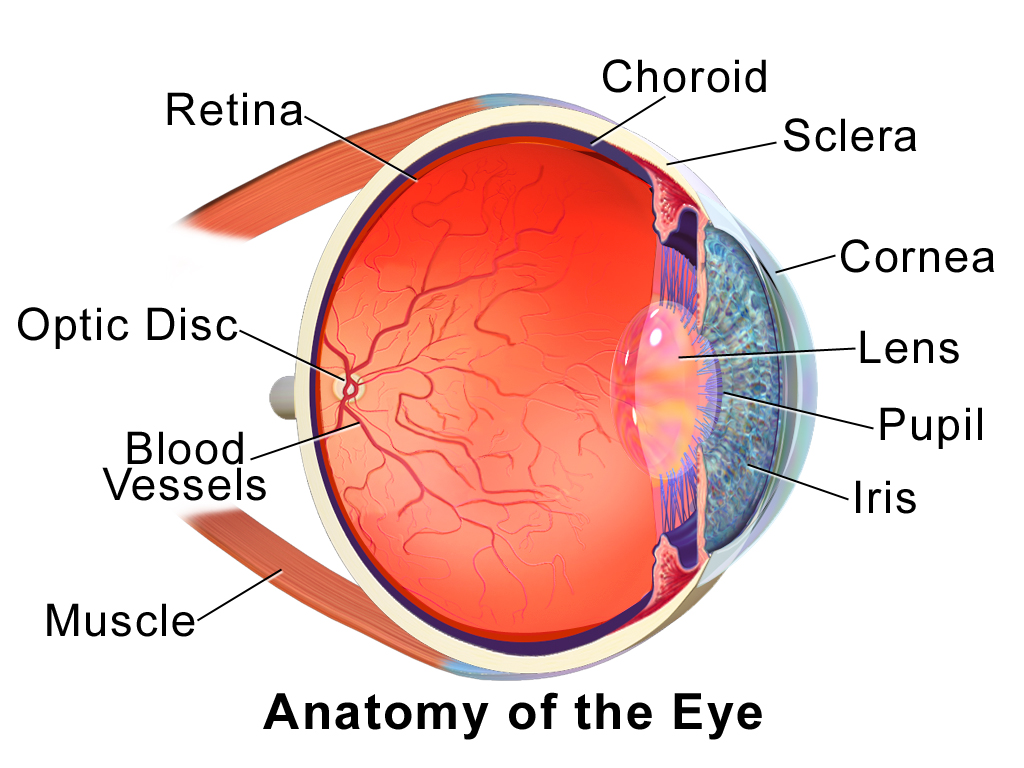

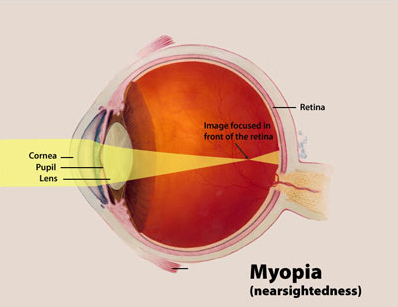

- Vision is the ability to sense light and see. The eye is the special sensory organ that collects and focuses light, forms images, and changes them to nerve impulses. Optic nerves send information from the eyes to the brain, which processes the visual information and “tells” us what we are seeing.

- Common vision problems include myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), and presbyopia (age-related decline in close vision).

- Hearing is the ability to sense sound waves, and the ear is the organ that senses sound. It changes sound waves to vibrations that trigger nerve impulses, which travel to the brain through the auditory nerve. The brain processes the information and “tells” us what we are hearing.

- The ear is also the organ responsible for the sense of balance, which is the ability to sense and maintain an appropriate body position. The ears send impulses on head position to the brain, which sends messages to skeletal muscle via the peripheral nervous system. The muscles respond by contracting to maintain balance.

- Taste and smell are both abilities to sense chemicals. Taste receptors in taste buds on the tongue sense chemicals in food, and olfactory receptors in the nasal passages sense chemicals in the air. The sense of smell contributes significantly to the sense of taste.

- Psychoactive drugs are substances that change the function of the brain and result in alterations of mood, thinking, perception, and behavior. They include prescription medications (such as opioid painkillers), legal substances (such as nicotine and alcohol), and illegal drugs (such as LSD and heroin).

- Psychoactive drugs are divided into different classes according to their pharmacological effects. They include stimulants, depressants, anxiolytics, euphoriants, hallucinogens, and empathogens. Many psychoactive drugs have multiple effects, so they may be placed in more than one class.

- Psychoactive drugs generally produce their effects by affecting brain chemistry. Generally, they act either as agonists, which enhance the activity of particular neurotransmitters, or as antagonists, which decrease the activity of particular neurotransmitters.

- Psychoactive drugs are used for medical, ritual, and recreational purposes.

- Misuse of psychoactive drugs may lead to addiction, which is the compulsive use of a drug, despite its negative consequences. Sustained use of an addictive drug may produce physical or psychological dependence on the drug. Rehabilitation typically involves psychotherapy, and sometimes the temporary use of other psychoactive drugs.

In addition to the nervous system, there is another system of the body that is important for coordinating and regulating many different functions – the endocrine system. You will learn about the endocrine system in the next chapter.

Chapter 8 Review

- Imagine that you decide to make a movement. To carry out this decision, a neuron in the cerebral cortex of your brain (neuron A) fires a nerve impulse that is sent to a neuron in your spinal cord (neuron B). Neuron B then sends the signal to a muscle cell, causing it to contract, resulting in movement. Answer the following questions about this pathway.

- Which part of the brain is neuron A located in — the cerebellum, cerebrum, or brain stem? Explain how you know.

- The cell body of neuron A is located in a lobe of the brain that is involved in abstract thought, problem solving, and planning. Which lobe is this?

- Part of neuron A travels all the way down to the spinal cord to meet neuron B. Which part of neuron A travels to the spinal cord?

- Neuron A forms a chemical synapse with neuron B in the spinal cord. How is the signal from neuron A transmitted to neuron B?

- Is neuron A in the central nervous system (CNS) or peripheral nervous system (PNS)?

- The axon of neuron B travels in a nerve to a skeletal muscle cell. Is the nerve part of the CNS or PNS? Is this an afferent nerve or an efferent nerve?

- What part of the PNS is involved in this pathway — the autonomic nervous system or the somatic nervous system? Explain your answer.

- What are the differences between a neurotransmitter receptor and a sensory receptor?

-

- If a person has a stroke and then has trouble using language correctly, which hemisphere of their brain was most likely damaged? Explain your answer.

- Electrical gradients are responsible for the resting potential and action potential in neurons. Answer the following questions about the electrical characteristics of neurons.

- Define an electrical gradient, in the context of a cell.

- What is responsible for maintaining the electrical gradient that results in the resting potential?

- Compare and contrast the resting potential and the action potential.

- Where along a myelinated axon does the action potential occur? Why does it happen here?

- What does it mean that the action potential is “all-or-none?”

- Compare and contrast Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes.

- For the senses of smell and hearing, name their respective sensory receptor cells, what type of receptor cells they are, and what stimuli they detect.

- Nicotine is a psychoactive drug that binds to and activates a receptor for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Is nicotine an agonist or an antagonist for acetylcholine? Explain your answer.

Attributions

Figure 8.9.1

Alzheimers_Disease by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 8.9.2

Alzheimer’s Disease stagess by NIH Image Gallery on Flickr is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Steady as She Goes

This device (Figure 7.8.1) looks simple, but it controls a complex system that keeps a home at a steady temperature — it's a thermostat. The device shows the current temperature in the room, and also allows the occupant to set the thermostat to the desired temperature. A thermostat is a commonly cited model of how living systems — including the human body— maintain a steady state called homeostasis.

What Is Homeostasis?

Homeostasis is the condition in which a system (such as the human body) is maintained in a more or less steady state. It is the job of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems throughout the body to maintain many different variables within narrow ranges compatible with life. Keeping a stable internal environment requires continually monitoring the internal environment and constantly making adjustments to keep things in balance.

Set Point and Normal Range

For any given variable, such as body temperature or blood glucose level, there is a particular set point that is the physiological optimum value. The set point for human body temperature, for example, is about 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). As the body works to maintain homeostasis for temperature or any other internal variable, the value typically fluctuates around the set point. Such fluctuations are normal, as long as they do not become too extreme. The spread of values within which such fluctuations are considered insignificant is called the normal range. In the case of body temperature, for example, the normal range for an adult is about 36.5 to 37.5 degrees C (97.7 to 99.5 degrees F).

A good analogy for set point, normal range, and maintenance of homeostasis is driving. When you are driving a vehicle on the road, you are supposed to drive in the centre of your lane — this is analogous to the set point. Sometimes, you are not driving in the exact centre of the lane, but you are still within your lines, so you are in the equivalent of the normal range. However, if you were to get too close to the centre line or the shoulder of the road, you would take action to correct your position. You'd move left if you were too close to the shoulder, or right if too close to the centre line — which is analogous to our next concept, negative feedback to maintain homeostasis.

Maintaining Homeostasis

Homeostasis is normally maintained in the human body by an extremely complex balancing act. Regardless of the variable being kept within its normal range, maintaining homeostasis requires at least four interacting components: stimulus, sensor, control centre, and effector.

- The stimulus is provided by the variable being regulated. Generally, the stimulus indicates that the value of the variable has moved away from the set point or has left the normal range.

- The sensor monitors the values of the variable and sends data on it to the control centre.

- The control centre matches the data with normal values. If the value is not at the set point or is outside the normal range, the control centre sends a signal to the effector.

- The effector is an organ, gland, muscle, or other structure that acts on the signal from the control centre to move the variable back toward the set point.

Each of these components is illustrated in Figure 7.8.2. The diagram on the left is a general model showing how the components interact to maintain homeostasis. The diagram on the right shows the example of body temperature. From the diagrams, you can see that maintaining homeostasis involves feedback, which is data that feeds back to control a response. Feedback may be negative (as in the example below) or positive. All the feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis use negative feedback. Biological examples of positive feedback are much less common.

Negative Feedback

In a negative feedback loop, feedback serves to reduce an excessive response and keep a variable within the normal range. Two processes controlled by negative feedback are body temperature regulation and control of blood glucose.

Body Temperature

Body temperature regulation involves negative feedback, whether it lowers the temperature or raises it, as shown in Figure 7.8.3 and explained in the text that follows.

Cooling Down

The human body’s temperature regulatory centre is the hypothalamus in the brain. When the hypothalamus receives data from sensors in the skin and brain that body temperature is higher than the set point, it sets into motion the following responses:

- Blood vessels in the skin dilate (vasodilation) to allow more blood from the warm body core to flow close to the surface of the body, so heat can be radiated into the environment.

- As blood flow to the skin increases, sweat glands in the skin are activated to increase their output of sweat (diaphoresis). When the sweat evaporates from the skin surface into the surrounding air, it takes heat with it.

- Breathing becomes deeper, and the person may breathe through the mouth instead of the nasal passages. This increases heat loss from the lungs.

Heating Up

When the brain’s temperature regulatory centre receives data that body temperature is lower than the set point, it sets into motion the following responses:

- Blood vessels in the skin contract (vasoconstriction) to prevent blood from flowing close to the surface of the body, which reduces heat loss from the surface.

- As temperature falls lower, random signals to skeletal muscles are triggered, causing them to contract. This causes shivering, which generates a small amount of heat.

- The thyroid gland may be stimulated by the brain (via the pituitary gland) to secrete more thyroid hormone. This hormone increases metabolic activity and heat production in cells throughout the body.