7.7 Interactions of Organ Systems

Figure 7.7.1 Everyone on a baseball team has a special job.

Teamwork

Every player on a baseball team has a special job. In the Figure 7.7.1 collage, each player has their part of the infield or outfield covered in case the ball comes their way. Other players on the team cover different parts of the field, or they pitch or catch the ball. Playing baseball clearly requires teamwork. In that regard, the human body is like a baseball team. All of the organ systems of the human body must work together as a team to keep the body alive and well. Teamwork within the body begins with communication.

Communication Among Organ Systems

Communication among organ systems is vital if they are to work together as a team. They must be able to respond to each other and change their responses as needed to keep the body in balance. Communication among organ systems is controlled mainly by the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system.

The autonomic nervous system is the part of the nervous system that controls involuntary functions. The autonomic nervous system, for example, controls heart rate, blood flow, and digestion. You don’t have to tell your heart to beat faster or to consciously squeeze muscles to push food through the digestive system. You don’t have to even think about these functions at all! The autonomic nervous system orchestrates all the signals needed to control them. It sends messages between parts of the nervous system, as well as between the nervous system and other organ systems via chemical messengers called neurotransmitters.

The endocrine system is the system of glands that secrete hormones directly into the bloodstream. Once in the blood, endocrine hormones circulate to cells everywhere in the body. The endocrine system itself is under control of the nervous system via a part of the brain called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus secretes hormones that travel directly to cells of the pituitary gland, which is located beneath it. The pituitary gland is the master gland of the endocrine system. Most of its hormones either turn on or turn off other endocrine glands. For example, if the pituitary gland secretes thyroid-stimulating hormone, the hormone travels through the circulation to the thyroid gland, which is stimulated to secrete thyroid hormone. Thyroid hormone then travels to cells throughout the body, where it increases their metabolism.

Examples of Organ System Interactions

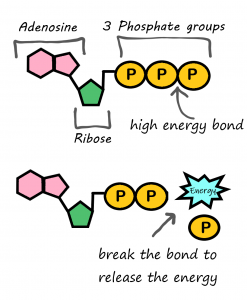

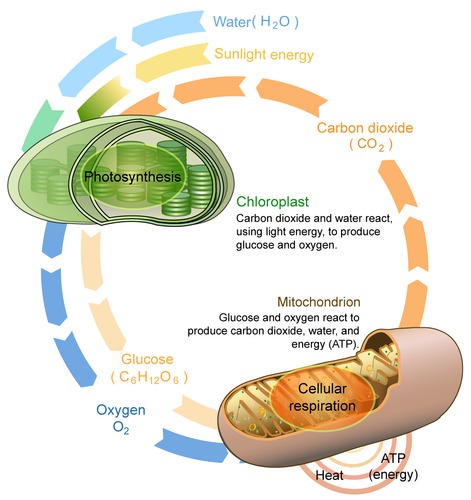

An increase in cellular metabolism requires more cellular respiration. Cellular respiration is a good example of organ system interactions, because it is a basic life process that occurs in all living cells.

Cellular Respiration

Cellular respiration is the intracellular process that breaks down glucose with oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and energy in the form of ATP molecules. It is the process by which cells obtain usable energy to power other cellular processes. Which organ systems are involved in cellular respiration? The glucose needed for cellular respiration comes from the digestive system via the cardiovascular system. The oxygen needed for cellular respiration comes from the respiratory system also via the cardiovascular system. The carbon dioxide produced in cellular respiration leaves the body by the opposite route. In short, cellular respiration requires — at a minimum — the digestive, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems.

Fight-or-Flight Response

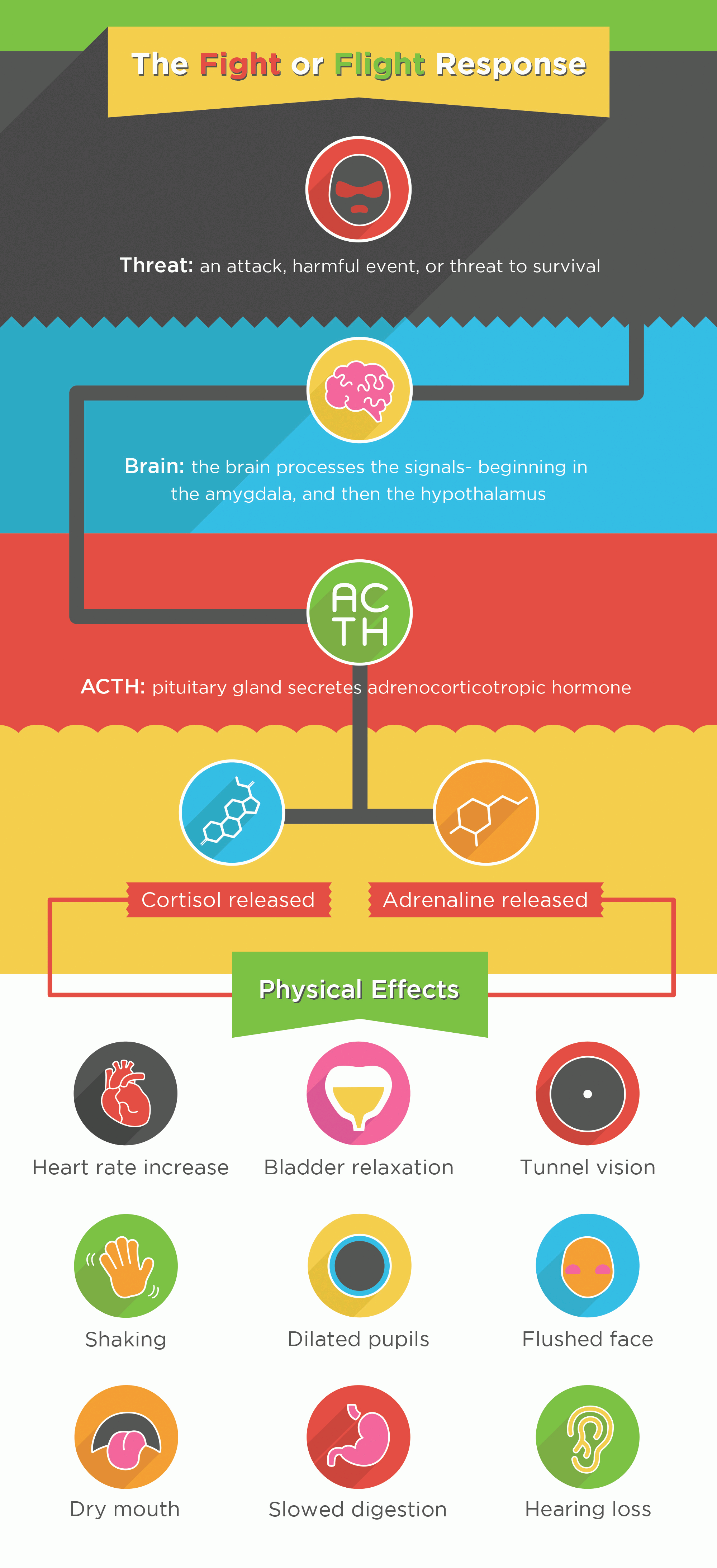

The well-known fight-or-flight response is a good example of how the nervous and endocrine systems control other organ system responses. The fight-or-flight response begins when the nervous system perceives sudden danger, as shown in the Figure 7.7.2 diagram. The brain sends a message to the endocrine system (via the pituitary gland) for the adrenal glands to secrete the hormones cortisol and adrenaline. These hormones flood the circulation and affect other organ systems throughout the body, including the cardiovascular, urinary, sensory, and digestive systems. Specific responses include increased heart rate, bladder relaxation, tunnel vision, and a shunting of blood away from the digestive system and toward the muscles, brain, and other vital organs needed to fight or flee.

Playing Baseball

The people playing baseball in the opening collage (Figure 7.7.1) are using multiple organ systems in this voluntary activity. Their nervous systems are focused on observing and preparing to respond to the next play. Their other systems are being controlled by the autonomic nervous system. The players are using the muscular, skeletal, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems. Can you explain how each of these organ systems is involved in playing baseball?

Feature: Reliable Sources

Teamwork among organ systems allows the human organism to work like a finely tuned machine — at least, it does until one of the organ systems fails. When that happens, other organ systems interacting in the same overall process will also be affected. This is especially likely if the affected system plays a controlling role in the process. An example is type 1 diabetes. This disorder occurs when the pancreas does not secrete the endocrine hormone insulin. Insulin normally is secreted in response to an increasing level of glucose in the blood, and it brings the level of glucose back to normal by stimulating body cells to take up insulin from the blood.

Learn more about type 1 diabetes. Use several reliable Internet sources to answer the following questions:

- In type 1 diabetes, what causes the endocrine system to fail to produce insulin?

- If type 1 diabetes is not controlled, which organ systems are affected by high blood glucose levels? What are some of the specific effects?

- How can blood glucose levels be controlled in patients with type 1 diabetes?

7.7 Summary

- The human body’s organ systems must work together to keep the body alive and functioning normally, which requires communication among systems. This communication is controlled by the autonomic nervous system and endocrine system. The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary body functions, such as heart rate and digestion. The endocrine system secretes hormones into the blood that travel to body cells and influence their activities.

- Cellular respiration is a good example of organ system interactions, because it is a basic life process that happens in all living cells. It is the intracellular process that breaks down glucose with oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and energy. Cellular respiration requires the interaction of the digestive, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems.

- The fight-or-flight response is a good example of how the nervous and endocrine systems control other organ system responses. It is triggered by a message from the brain to the endocrine system and prepares the body for flight or a fight. Many organ systems are stimulated to respond, including the cardiovascular, respiratory, and digestive systems.

- Playing baseball — or doing other voluntary physical activities — may involve the interaction of nervous, muscular, skeletal, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems.

7.7 Review Questions

- What is the autonomic nervous system?

- How do the autonomic nervous system and endocrine system communicate with other organ systems so the systems can interact?

- Explain how the brain communicates with the endocrine system.

- What is the role of the pituitary gland in the endocrine system?

- Identify the organ systems that play a role in cellular respiration.

- How does the hormone adrenaline prepare the body to fight or flee? What specific physiological changes does it bring about?

- Explain the role of the muscular system in digesting food.

- Describe how three different organ systems are involved when a player makes a particular play in baseball, such as catching a fly ball.

-

- What are two types of molecules that the body uses to communicate between organ systems?

- Explain why hormones can have such a wide variety of effects on the body.

7.7 Explore More

3D Medical Animation – Peristalsis in Large Intestine/Bowel ||

©Animated Biomedical Productions (ABP), 2013.

Adrenaline: Fight or Flight Response, Henk van ‘t Klooster, 2013.

Fight or Flight Response, Bozeman Science, 2012.

Attributions

Figure 7.7.1

- Baseball positions by Michael J on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de) license.

- US Navy 040229-N-8629D-070 photo by US Navy‘s Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Brett A. Dawson on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

- David Ortiz batter’s box by Albert Yau/ SecondPrint Productions on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.es) license.

- Fenway-from Legend’s Box by Jared Vincent on Wikipedia is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 7.7.2

The_Fight_or_Flight_Response by Jvnkfood (original), converted to PNG and reduced to 8-bit by Pokéfan95 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

References

Animated Biomedical Productions. (2013, January 30). 3D Medical animation – Peristalsis in large intestine/bowel || ©ABP. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ujr0UAbyPS4&feature=youtu.be

Bozeman Science. (2012, January 9). Fight or flight response. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m2GywoS77qc&feature=youtu.be

Henk van ‘t Klooster. (2013). Adrenaline: Fight or flight response. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBnBTkcr6No&t=4s

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Type 1 diabetes. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-1-diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20353011

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 22). Thyroid-stimulating hormone. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thyroid-stimulating_hormone&oldid=968942540

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study Conclusion: Fading Memory

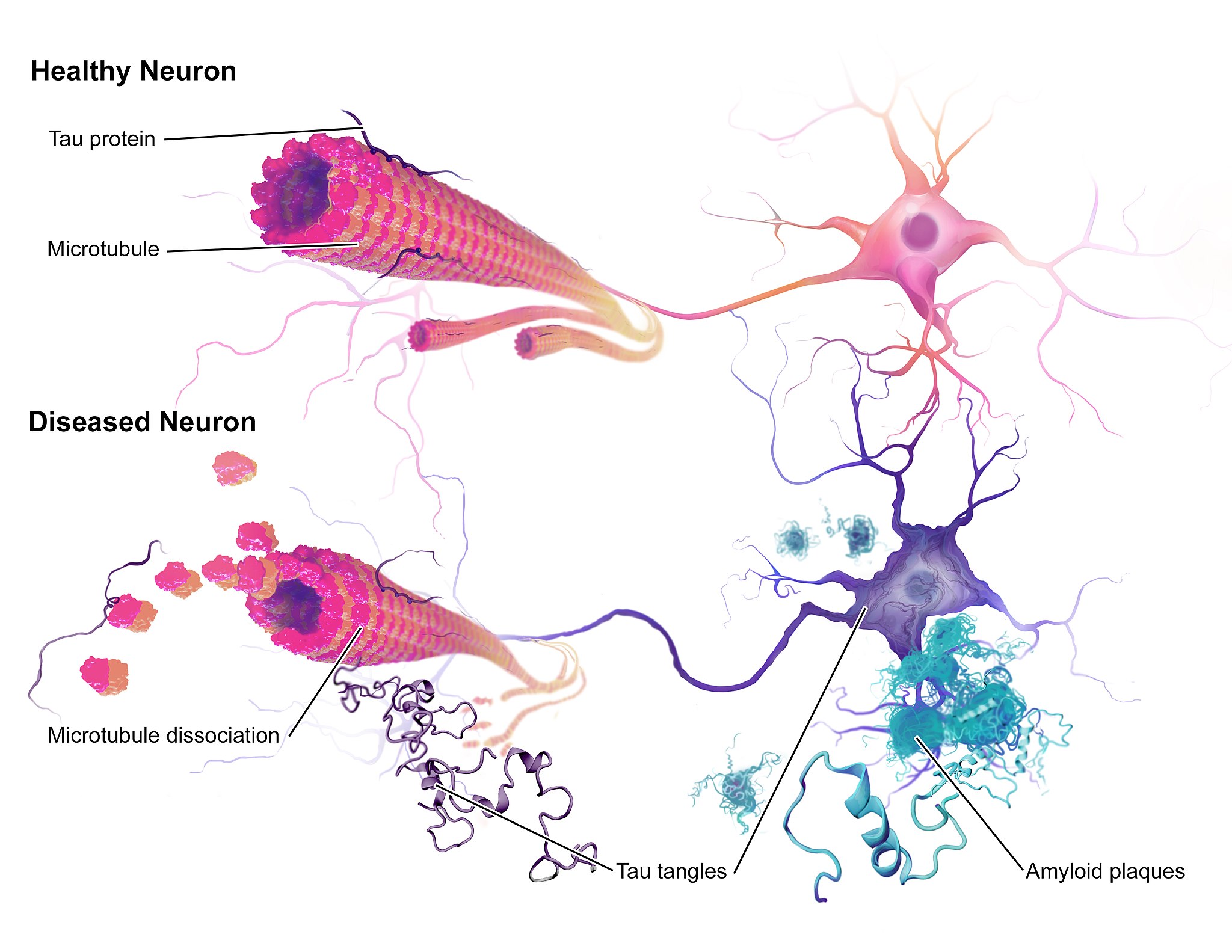

The illustration above (Figure 8.9.1) shows some of the molecular and cellular changes that occur in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Rosa was diagnosed with AD at the beginning of this chapter after experiencing memory problems and other changes in her cognitive functioning, mood, and personality. These abnormal changes in the brain include the development of amyloid plaques between brain cells and neurofibrillary tangles inside of neurons. These hallmark characteristics of AD are associated with the loss of synapses between neurons, and ultimately the death of neurons.

After reading this chapter, you should have a good appreciation for the importance of keeping neurons alive and communicating with each other at synapses. The nervous system coordinates all of the body’s voluntary and involuntary activities. It interprets information from the outside world through sensory systems, and makes appropriate responses through the motor system, through communication between the PNS and CNS. The brain directs the rest of the nervous system and controls everything from basic vital functions (such as heart rate and breathing) to high-level functions (such as problem solving and abstract thought). The nervous system can perform these important functions by generating action potentials in neurons in response to stimulation and sending messages between cells at synapses, typically using chemical neurotransmitter molecules. When neurons are not functioning properly, lose their synapses, or die, they cannot carry out the signaling essential for the proper functioning of the nervous system.

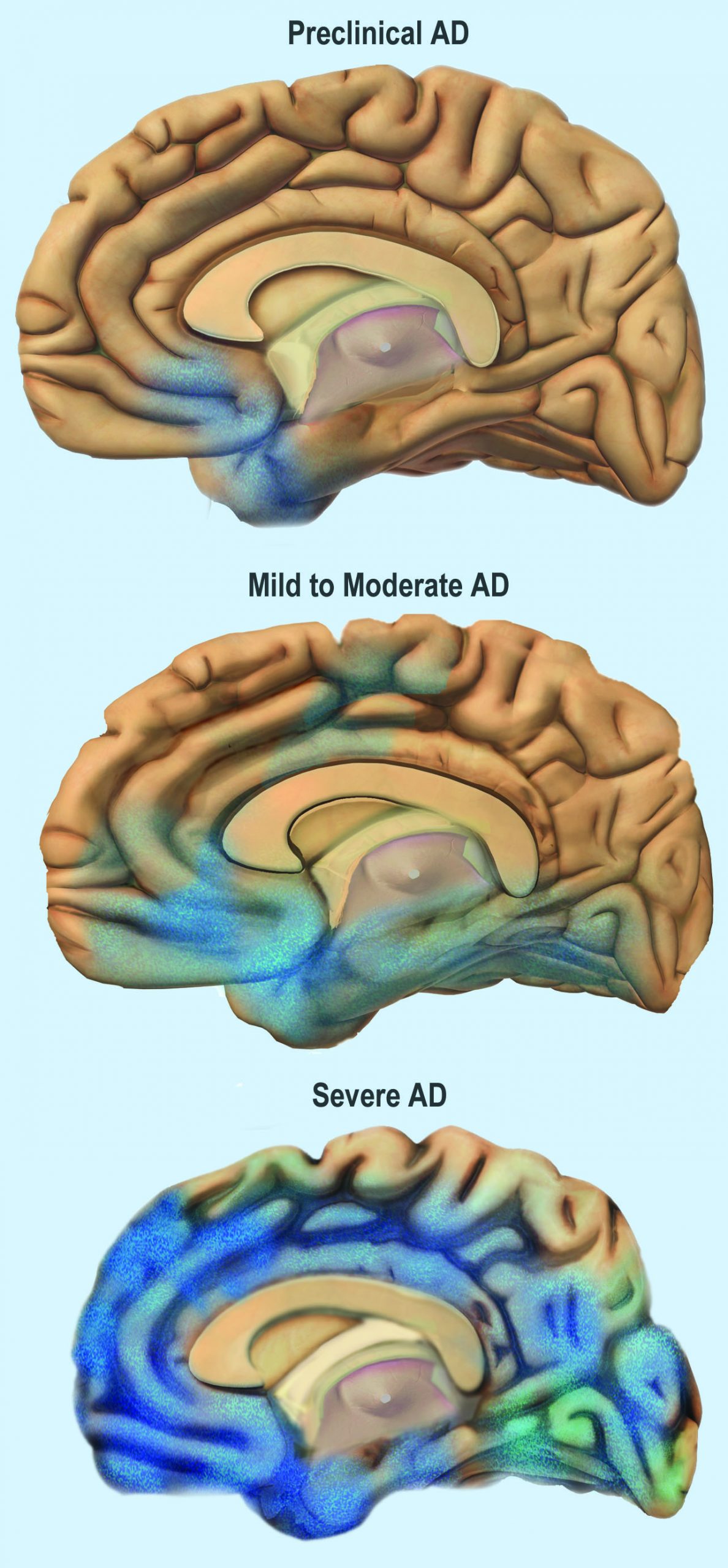

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, meaning that the damage to the brain becomes more extensive as time goes on. The picture in Figure 8.9.2 illustrates how the damage progresses from before AD is diagnosed (preclinical AD), to mild and moderate AD, to severe AD.

You can see that the damage starts in a relatively small location toward the bottom of the brain. One of the earliest brain areas to be affected by AD is the hippocampus. As you have learned, the hippocampus is important for learning and memory, which explains why many of Rosa’s symptoms of mild AD involve deficits in memory, such as trouble remembering where she placed objects, recent conversations, and appointments.

As AD progresses, more of the brain is affected, including areas involved in emotional regulation, social behavior, planning, language, spatial navigation, and higher-level thought. Rosa is beginning to show signs of problems in these areas, including irritability, lashing out at family members, getting lost in her neighborhood, problems finding the right words, putting objects in unusual locations, and difficulty in managing her finances. You can see that as AD progresses, damage spreads further across the cerebrum, which you now know controls conscious functions like reasoning, language, and interpretation of sensory stimuli. You can also see how the frontal lobe — which controls executive functions such as planning, self-control, and abstract thought — becomes increasingly damaged.

Increasing damage to the brain causes corresponding deficits in functioning. In moderate AD, patients have increased memory, language, and cognitive deficits, compared to mild AD. They may not recognize their own family members, and may wander and get lost, engage in inappropriate behaviors, become easily agitated, and have trouble carrying out daily activities such as dressing. In severe AD, much of the brain is affected. Patients usually cannot recognize family members or communicate, and they are often fully dependent on others for their care. They begin to lose the ability to control their basic functions, such as bladder control, bowel control, and proper swallowing. Eventually, AD causes death, usually as a result of this loss of basic functions.

For now, Rosa only has mild AD and is still able to function relatively well with care from her family. The medication her doctor gave her has helped improve some of her symptoms. It is a cholinesterase inhibitor, which blocks an enzyme that normally degrades the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. With more of the neurotransmitter available, more of it can bind to neurotransmitter receptors on postsynaptic cells. Therefore, this drug acts as an agonist for acetylcholine, which enhances communication between neurons in Rosa’s brain. This increase in neuronal communication can help restore some of the functions lost in early Alzheimer’s disease and may slow the progression of symptoms.

But medication such as this is only a short-term measure, and does not halt the progression of the underlying disease. Ideally, the damaged or dead neurons would be replaced by new, functioning neurons. Why does this not happen automatically in the body? As you have learned, neurogenesis is very limited in adult humans, so once neurons in the brain die, they are not normally replaced to any significant extent. Scientists, however, are studying the ways in which neurogenesis might be increased in cases of disease or injury to the brain. They are also investigating the possibility of using stem cell transplants to replace damaged or dead neurons with new neurons. But this research is in very early stages and is not currently a treatment for AD.

One promising area of research is in the development of methods to allow earlier detection and treatment of AD, given that the changes in the brain may actually start ten to 20 years before diagnosis of AD. A radiolabeled chemical called Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) binds to amyloid plaques in the brain, and in the future, it may be used in conjunction with brain imaging techniques to detect early signs of AD. Scientists are also looking for biomarkers in bodily fluids (such as blood and cerebrospinal fluid) that might indicate the presence of AD before symptoms appear. Finally, researchers are also investigating possible early and subtle symptoms (such as changes in how people move or a loss of smell) to see whether they can be used to identify people who will go on to develop AD. This research is in the early stages, but the hope is that patients can be identified earlier, allowing for earlier and more effective treatment, as well as more planning time for families.

Scientists are also still trying to fully understand the causes of AD, which affects more than five million Americans. Some genetic mutations have been identified as contributors, but environmental factors also appear to be important. With more research into the causes and mechanisms of AD, hopefully a cure can be found, and people like Rosa can live a longer and better life.

Chapter 8 Summary

In this chapter, you learned about the human nervous system. Specifically, you learned that:

- The nervous system is the organ system that coordinates all of the body’s voluntary and involuntary actions by transmitting signals to and from different parts of the body. It has two major divisions: the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

- The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord.

- The PNS consists mainly of nerves that connect the CNS with the rest of the body. It has two major divisions: the somatic nervous system and the autonomic nervous system. These divisions control different types of functions, and often interact with the CNS to carry out these functions. The somatic system controls activities that are under voluntary control. The autonomic system controls activities that are involuntary.

- The autonomic nervous system is further divided into the sympathetic division (which controls the fight-or-flight response), the parasympathetic division (which controls most routine involuntary responses), and the enteric division (which provides local control for digestive processes).

- Signals sent by the nervous system are electrical signals called nerve impulses. They are transmitted by special, electrically excitable cells called neurons, which are one of two major types of cells in the nervous system.

- Neuroglia are the other major type of nervous system cells. There are many types of glial cells, and they have many specific functions. In general, neuroglia function to support, protect, and nourish neurons.

- The main parts of a neuron include the cell body, dendrites, and axon. The cell body contains the nucleus. Dendrites receive nerve impulses from other cells, and the axon transmits nerve impulses to other cells at axon terminals. A synapse is a complex membrane junction at the end of an axon terminal that transmits signals to another cell.

- Axons are often wrapped in an electrically-insulating myelin sheath, which is produced by oligodendrocytes or schwann cells, both of which are types of neuroglia. Electrical impulses called action potentials occur at gaps in the myelin sheath, called nodes of Ranvier, which speeds the conduction of nerve impulses down the axon.

- Neurogenesis, or the formation of new neurons by cell division, may occur in a mature human brain — but only to a limited extent.

- The nervous tissue in the brain and spinal cord consists of gray matter — which contains mainly unmyelinated cell bodies and dendrites of neurons — and white matter, which contains mainly myelinated axons of neurons. Nerves of the peripheral nervous system consist of long bundles of myelinated axons that extend throughout the body.

- There are hundreds of types of neurons in the human nervous system, but many can be classified on the basis of the direction in which they carry nerve impulses. Sensory neurons carry nerve impulses away from the body and toward the central nervous system, motor neurons carry them away from the central nervous system and toward the body, and interneurons often carry them between sensory and motor neurons.

- A nerve impulse is an electrical phenomenon that occurs because of a difference in electrical charge across the plasma membrane of a neuron.

- The sodium-potassium pump maintains an electrical gradient across the plasma membrane of a neuron when it is not actively transmitting a nerve impulse. This gradient is called the resting potential of the neuron.

- An action potential is a sudden reversal of the electrical gradient across the plasma membrane of a resting neuron. It begins when the neuron receives a chemical signal from another cell or some other type of stimulus. The action potential travels rapidly down the neuron’s axon as an electric current.

- A nerve impulse is transmitted to another cell at either an electrical or a chemical synapse. At a chemical synapse, neurotransmitter chemicals are released from the presynaptic cell into the synaptic cleft between cells. The chemicals travel across the cleft to the postsynaptic cell and bind to receptors embedded in its membrane.

- There are many different types of neurotransmitters. Their effects on the postsynaptic cell generally depend on the type of receptor they bind to. The effects may be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory in more complex ways. Both physical and mental disorders may occur if there are problems with neurotransmitters or their receptors.

- The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord. It is physically protected by bones, meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid. It is chemically protected by the blood-brain barrier.

- The brain is the control center of the nervous system and of the entire organism. The brain uses a relatively large proportion of the body’s energy, primarily in the form of glucose.

-

- The brain is divided into three major parts, each with different functions: the forebrain, the midbrain and the hindbrain.

- The forebrain includes the cerebrum, the thalamus, the hypothalamus, the hippocampus and the amygdala. The cerebrum is further divided into left and right hemispheres. Each hemisphere has four lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. Each lobe is associated with specific senses or other functions. The cerebrum has a thin outer layer called the cerebral cortex. Its many folds give it a large surface area. This is where most information processing takes place.

- The thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala are all part of the limbic system which helps regulate memories, coordination and attention

- The brain is divided into three major parts, each with different functions: the forebrain, the midbrain and the hindbrain.

- The spinal cord is a tubular bundle of nervous tissues that extends from the head down the middle of the back to the pelvis. It functions mainly to connect the brain with the PNS. It also controls certain rapid responses called reflexes without input from the brain.

- A spinal cord injury may lead to paralysis (loss of sensation and movement) of the body below the level of the injury, because nerve impulses can no longer travel up and down the spinal cord beyond that point.

- The PNS consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside of the CNS. Its main function is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism.

- The tissues that make up the PNS are nerves and ganglia. Nerves are bundles of axons and ganglia are groups of cell bodies. Nerves are classified as sensory, motor, or a mix of the two.

- The PNS is not as well protected physically or chemically as the CNS, so it is more prone to injury and disease. PNS problems include injury from diabetes, shingles, and heavy metal poisoning. Two disorders of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

- The human body has two major types of senses: special senses and general senses. Special senses have specialized sense organs and include vision (eyes), hearing (ears), balance (ears), taste (tongue), and smell (nasal passages). General senses are all associated with touch and lack special sense organs. Touch receptors are found throughout the body but particularly in the skin.

- All senses depend on sensory receptor cells to detect sensory stimuli and transform them into nerve impulses. Types of sensory receptors include mechanoreceptors (mechanical forces), thermoreceptors (temperature), nociceptors (pain), photoreceptors (light), and chemoreceptors (chemicals).

- Touch includes the ability to sense pressure, vibration, temperature, pain, and other tactile stimuli. The skin includes several different types of touch receptor cells.

- Vision is the ability to sense light and see. The eye is the special sensory organ that collects and focuses light, forms images, and changes them to nerve impulses. Optic nerves send information from the eyes to the brain, which processes the visual information and “tells” us what we are seeing.

- Common vision problems include myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), and presbyopia (age-related decline in close vision).

- Hearing is the ability to sense sound waves, and the ear is the organ that senses sound. It changes sound waves to vibrations that trigger nerve impulses, which travel to the brain through the auditory nerve. The brain processes the information and “tells” us what we are hearing.

- The ear is also the organ responsible for the sense of balance, which is the ability to sense and maintain an appropriate body position. The ears send impulses on head position to the brain, which sends messages to skeletal muscle via the peripheral nervous system. The muscles respond by contracting to maintain balance.

- Taste and smell are both abilities to sense chemicals. Taste receptors in taste buds on the tongue sense chemicals in food, and olfactory receptors in the nasal passages sense chemicals in the air. The sense of smell contributes significantly to the sense of taste.

- Psychoactive drugs are substances that change the function of the brain and result in alterations of mood, thinking, perception, and behavior. They include prescription medications (such as opioid painkillers), legal substances (such as nicotine and alcohol), and illegal drugs (such as LSD and heroin).

- Psychoactive drugs are divided into different classes according to their pharmacological effects. They include stimulants, depressants, anxiolytics, euphoriants, hallucinogens, and empathogens. Many psychoactive drugs have multiple effects, so they may be placed in more than one class.

- Psychoactive drugs generally produce their effects by affecting brain chemistry. Generally, they act either as agonists, which enhance the activity of particular neurotransmitters, or as antagonists, which decrease the activity of particular neurotransmitters.

- Psychoactive drugs are used for medical, ritual, and recreational purposes.

- Misuse of psychoactive drugs may lead to addiction, which is the compulsive use of a drug, despite its negative consequences. Sustained use of an addictive drug may produce physical or psychological dependence on the drug. Rehabilitation typically involves psychotherapy, and sometimes the temporary use of other psychoactive drugs.

In addition to the nervous system, there is another system of the body that is important for coordinating and regulating many different functions – the endocrine system. You will learn about the endocrine system in the next chapter.

Chapter 8 Review

- Imagine that you decide to make a movement. To carry out this decision, a neuron in the cerebral cortex of your brain (neuron A) fires a nerve impulse that is sent to a neuron in your spinal cord (neuron B). Neuron B then sends the signal to a muscle cell, causing it to contract, resulting in movement. Answer the following questions about this pathway.

- Which part of the brain is neuron A located in — the cerebellum, cerebrum, or brain stem? Explain how you know.

- The cell body of neuron A is located in a lobe of the brain that is involved in abstract thought, problem solving, and planning. Which lobe is this?

- Part of neuron A travels all the way down to the spinal cord to meet neuron B. Which part of neuron A travels to the spinal cord?

- Neuron A forms a chemical synapse with neuron B in the spinal cord. How is the signal from neuron A transmitted to neuron B?

- Is neuron A in the central nervous system (CNS) or peripheral nervous system (PNS)?

- The axon of neuron B travels in a nerve to a skeletal muscle cell. Is the nerve part of the CNS or PNS? Is this an afferent nerve or an efferent nerve?

- What part of the PNS is involved in this pathway — the autonomic nervous system or the somatic nervous system? Explain your answer.

- What are the differences between a neurotransmitter receptor and a sensory receptor?

-

- If a person has a stroke and then has trouble using language correctly, which hemisphere of their brain was most likely damaged? Explain your answer.

- Electrical gradients are responsible for the resting potential and action potential in neurons. Answer the following questions about the electrical characteristics of neurons.

- Define an electrical gradient, in the context of a cell.

- What is responsible for maintaining the electrical gradient that results in the resting potential?

- Compare and contrast the resting potential and the action potential.

- Where along a myelinated axon does the action potential occur? Why does it happen here?

- What does it mean that the action potential is “all-or-none?”

- Compare and contrast Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes.

- For the senses of smell and hearing, name their respective sensory receptor cells, what type of receptor cells they are, and what stimuli they detect.

- Nicotine is a psychoactive drug that binds to and activates a receptor for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Is nicotine an agonist or an antagonist for acetylcholine? Explain your answer.

Attributions

Figure 8.9.1

Alzheimers_Disease by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 8.9.2

Alzheimer’s Disease stagess by NIH Image Gallery on Flickr is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Jumping for Joy!

The people in Figure 6.2.1 illustrate some of the great phenotypic variation displayed in modern Homo sapiens. The lighter-skinned men in the photo are Euro-American tourists in Kenya (East Africa). The darker-skinned men are native Kenyans who belong to a tribal group named the Maasai. These men come from populations on different continents on opposite sides of the globe. Their populations have unique histories, environments, and cultures. Besides differences in skin colour, the men have different hair and eye colours, facial features, and body builds. Based on such obvious physical differences, you might think that our species is characterized by a high degree of genetic variation. In fact, there is much less genetic variation in the human species than there is in many other mammalian species, including our closest relatives — the chimpanzees.

Overview of Human Genetic Variation

No two human individuals are genetically identical unless they are monozygotic (identical) twins. Between any two people, DNA differs, on average, at about one in one thousand nucleotide base pairs. We each have a total of about three billion base pairs, so any two people differ by an average of about three million base pairs. That may sound like a lot, but it's only 0.1% of our total genetic makeup. This means that two people chosen at random are likely to be 99.9 per cent identical genetically, no matter where in the world they come from.

At an individual level, most human genetic variation is not very important biologically, because it has no apparent adaptive significance. It neither enhances nor detracts from individual fitness. Only a small percentage of DNA variations actually occur in coding regions of DNA — which are sequences that are translated into proteins — or in regulatory regions, which are sequences that control gene expression. Differences that occur in other regions of DNA have no impact on phenotype. Even variations in coding regions of DNA may or may not affect phenotype. Some DNA variations may alter the amino acid sequence of a protein, but not affect how the protein functions. Other DNA variations do not even change the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein.

At a population level, genetic variation is crucial if evolution is to occur. Genetically-based differences in fitness among individuals are the key to evolution by natural selection. Without genetic variation within populations, there can be no differential fitness by genotype, and natural selection cannot occur.

Patterns of Human Genetic Variation

Data comparing DNA sequences from around the world show that only about ten per cent of our total genetic variation occurs between people from different continents, like the American tourists and African Maasai pictured in Figure 6.1.1. The other 90 per cent of genetic variation occurs between people within continental populations, such as between North Americans or between Africans. Within any human population, many genes have two or more normal alleles that contribute to genetic differences among individuals. The case in which a gene has two or more alleles in a population at frequencies greater than one per cent is called a polymorphism. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) involves variation in just one nucleotide in a DNA sequence. SNPs account for most of our genetic differences. Other types of variations (such as deletions and insertions of nucleotides in DNA sequences) account for a much smaller proportion of our overall genetic variation.

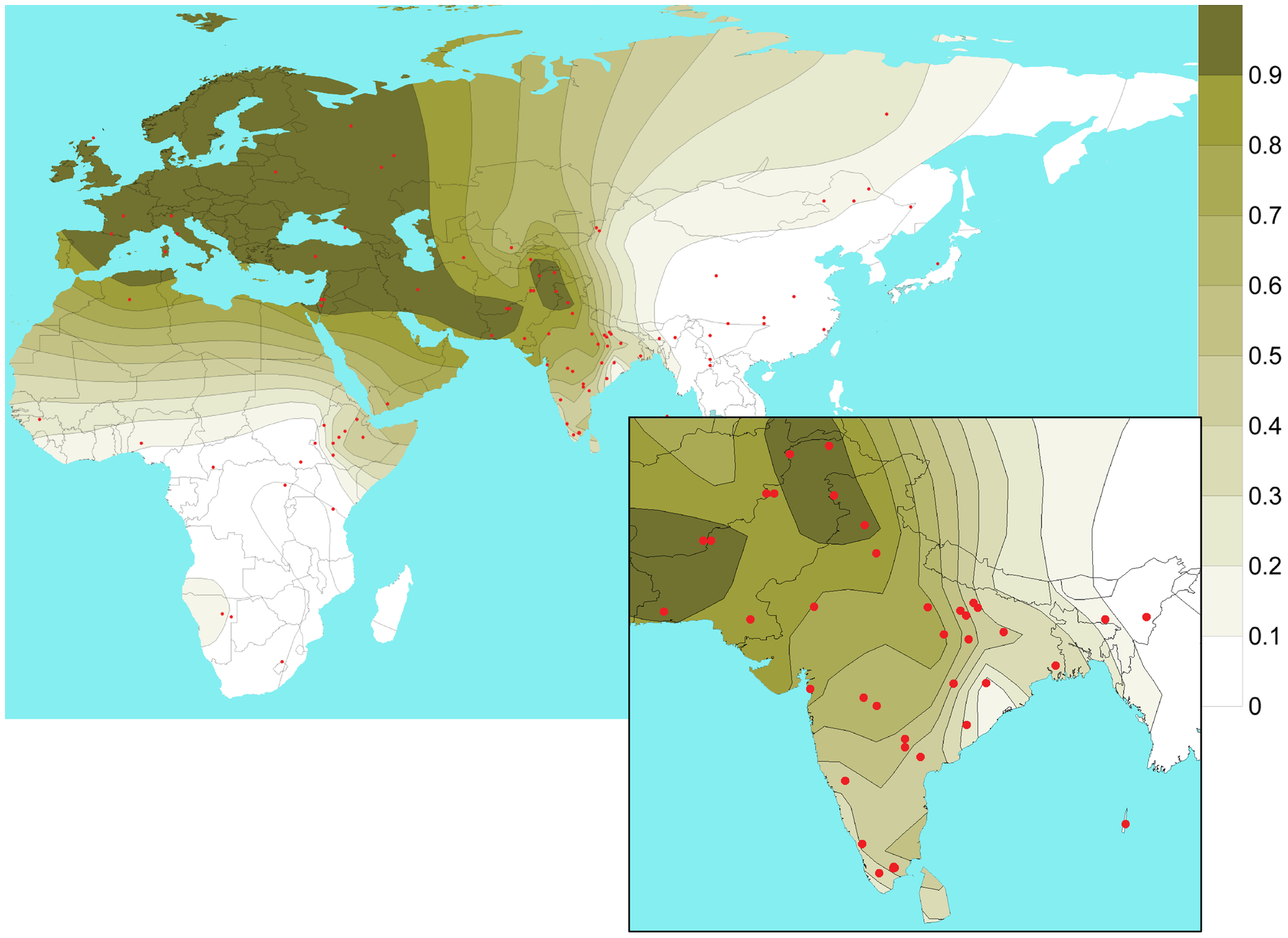

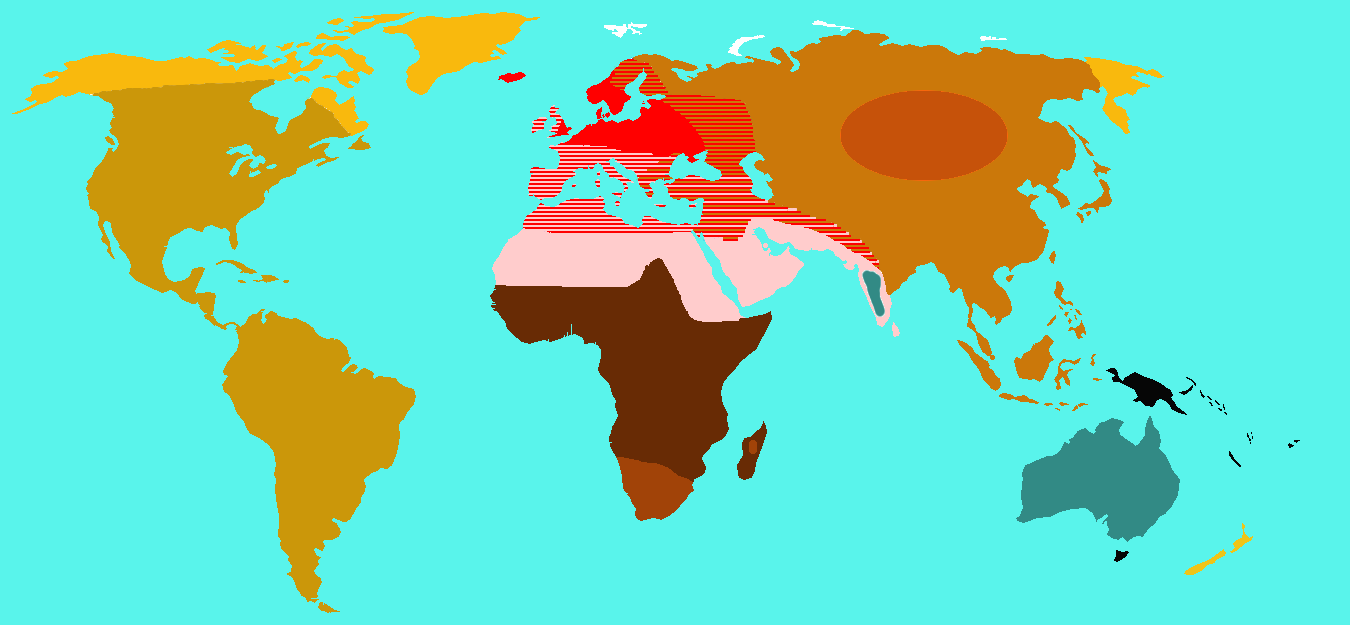

Different populations may have different allele frequencies for polymorphic genes. However, the distribution of allele frequencies in different populations around the world tends not to be discrete or distinct. Instead, the pattern is more often one of gradual geographic variations, or clines, in allele frequencies. You can see an example of a clinal distribution of allele frequencies in the map (Figure 6.2.2) below. Clinal distributions like this may be a reflection of natural selection pressures varying continuously over geographic space, or they may reflect a combination of genetic drift and gene flow of neutral alleles.

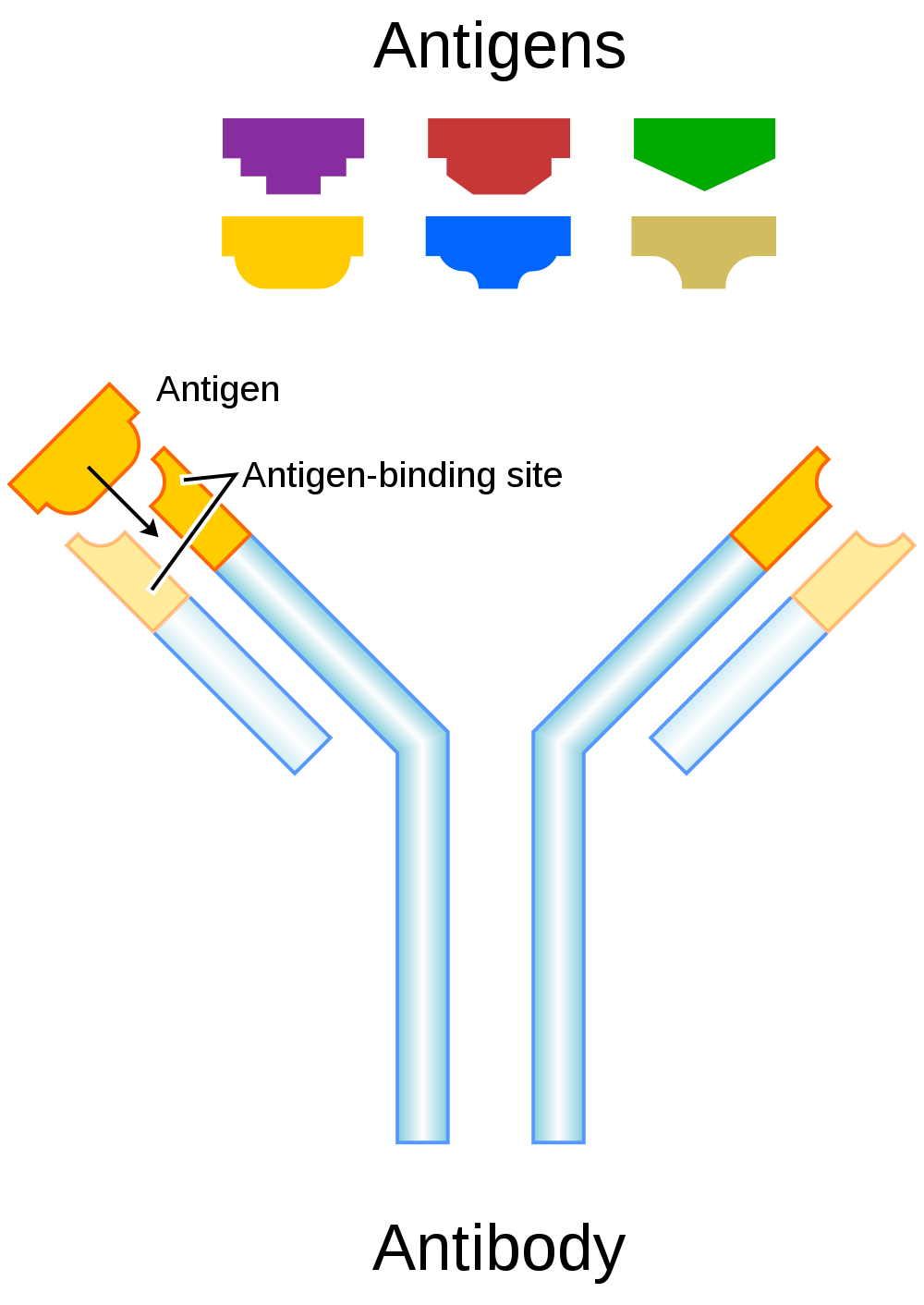

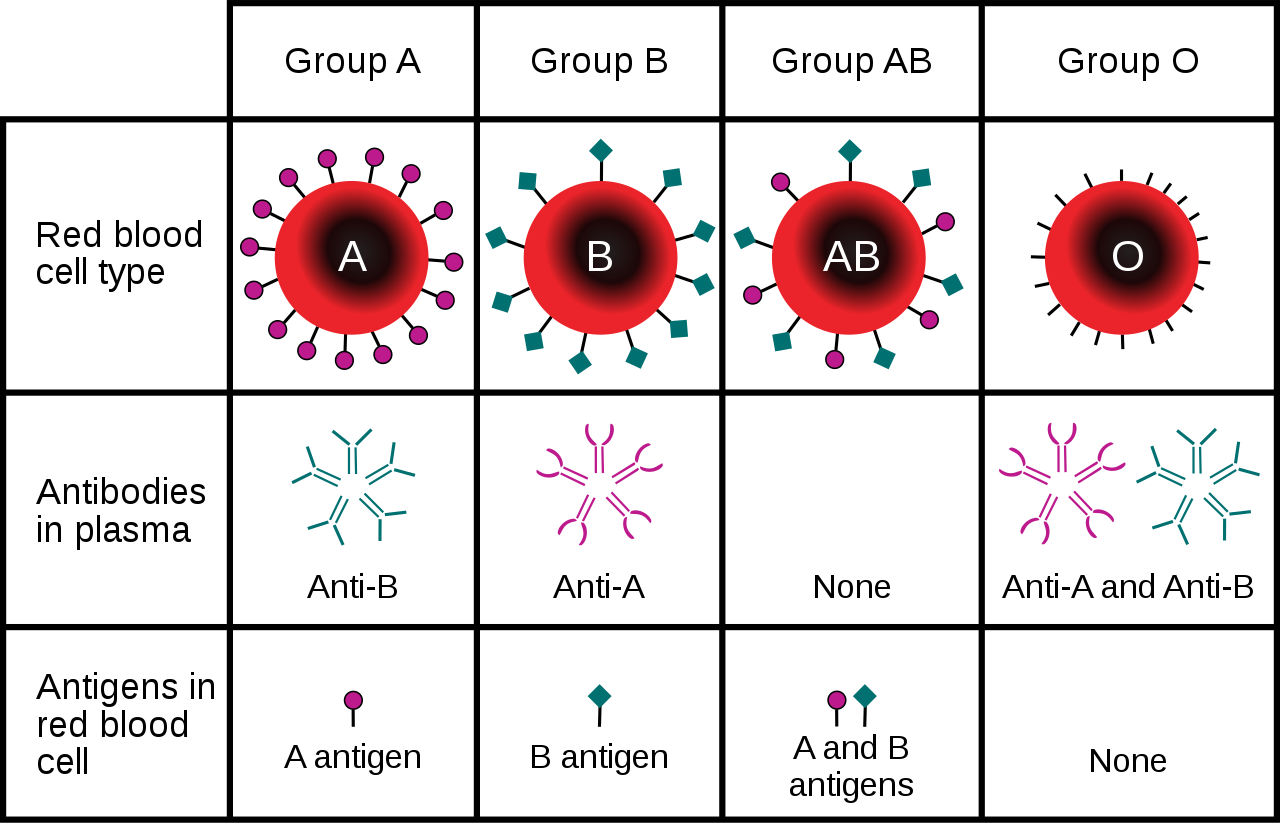

Although most genetic variation occurs within rather than between populations, certain alleles do seem to cluster in particular geographic areas. One example happens with the Duffy gene. Variations in this gene are the basis of the Duffy blood group, which is determined by the presence or absence of a red blood cell antigen, similar to the more familiar ABO blood group antigens. The genotype for having no antigen for the Duffy blood group is far higher in African populations and in people who have African ancestry than it is in non-African people, as indicated in the following table. Genes (such as the Duffy gene) may be useful as genetic markers to establish the ancestral populations of individuals.

Table 6.2.1

Population Frequencies for No Antigen in the Duffy Blood Group

| Population | Per cent of Population Lacking Duffy Antigen |

| African | 88-100 |

| African American | 68 |

| non-African American | <1 |

The reason for the different population frequencies for the Duffy antigen appears to be natural selection. People who lack the Duffy antigen are relatively resistant to malaria, which is one of the oldest and most devastating human diseases. Malaria has been a persistent and widespread disease in sub-Saharan Africa for tens of thousands of years. DNA analyses suggest that the allele associated with lack of the Duffy antigen evolved at least twice in Africa and was strongly selected for, causing it to increase in frequency. The Duffy gene is just one of many genes that have polymorphic alleles, because one of the alleles protects against malaria. In fact, a greater number of known genetic polymorphisms may be attributed to selection because of malaria than any other single selective agent.

Factors Influencing the Level of Human Genetic Variation

The age and size of a population increases the genetic variation within that population. You would expect an older, larger population to have more genetic variation. The older a population is, the longer it has been accumulating mutations. The larger a population is, the more people there are in which mutations can occur. Anatomically modern humans evolved less than a quarter million years ago, which is a relatively short period of time for mutations to accumulate. Our population was also quite small at some point in the past, perhaps consisting of no more than ten thousand adults, which reduced genetic variation even more. These factors explain why humans are relatively homogeneous genetically as a species.

What We Can Learn From Knowledge of Human Genetic Variation

Knowledge of genetic variation can help us understand our similarities and differences, our origins, and our evolutionary past. It can also help us understand human diseases and — hopefully — find new ways to treat them.

Human Origins

The data on human genetic variation generally supports the out-of-Africa hypothesis for human origins. According to this hypothesis, the common ancestor of all modern humans evolved in Africa around 200 thousand years ago. Then, starting no later than about 60 thousand years ago, part of the African population left Africa and migrated to Europe and Asia. As the migrants spread throughout the Old World, they replaced (and/or absorbed) the populations of archaic humans they encountered.

Most studies of human genetic variation find there is greater genetic diversity in African than non-African populations. This is consistent with the older age of the African population proposed by the out-of-Africa hypothesis. In addition, most of the genetic variation in non-African populations is a subset of the variation in African populations. This is consistent with the idea that part of the African population left Africa much later and migrated to other places in the Old World.

Recent comparisons of modern human and archaic human (including Neanderthal and Denisovan) DNA show that interbreeding occurred between their populations, but to differing degrees. The result of new DNA sequences entering a population’s gene pool through interbreeding is called admixture. There is greater admixture with archaic humans in modern European, Asian, and Oceanic populations than in modern African populations. Populations with the greatest admixture are those in Melanesia. About eight per cent of their DNA came from archaic Denisovans in East Asia.

Human Population History

Patterns of human genetic variation can be used to reconstruct population history. That history is literally recorded in our DNA. Any major population event (such as a significant reduction in population size or a high rate of migration) leaves a mark on a population’s genetic variation.

- Going through a dramatic size reduction decreases intra-population genetic variation (variation occurring within a population). As a case in point, DNA analyses suggest that there may have been drastic size reductions in the human populations that colonized the New World between 15 thousand and 20 thousand years ago. There were also size reductions in the human populations that first left Africa at least 60 thousand years ago, which helps explain the lower genetic diversity of modern non-African populations.

- A high rate of migration between populations may lead to gene flow, and this changes genetic variation in two ways. Gene flow decreases inter-population genetic variation (variation occurring between populations), while it increases intra-population variation. Gene flow — primarily between nearby populations — may contribute to the formation of clines in allele frequencies, as on the map in Figure 6.2.2.

Human Genetic Variation and Disease

An important benefit of studying human genetic variation is that we can learn more about the genetic basis of human diseases. The more we understand the causes of diseases, the more likely it is that we will be able to find effective treatments and cures for them.

Some disorders are caused by mutations in a single gene. Most of these disorders are generally rare, but some of them occur at significantly higher frequencies in certain populations. For example, Ellis-van Creveld syndrome has an unusually high frequency in Pennsylvania Amish populations, and Tay-Sachs disease has a relatively high frequency in Ashkenazi Jewish populations. Albinism is another single-gene disorder that has a variable frequency. In North America and Europe, rates of albinism are approximately 1:18,000. In Africa, in contrast, the rates range from 1:5,000 to 1:15,000. Some African populations have estimated albinism rates as high as 1:1000. The photo below (Figure 6.2.3) shows an African albino man from Mali, where there is a relatively high rate of albinism. High population-specific frequencies of single-gene disorders like these may be attributable to a variety of factors, such as small founding populations and a relative lack of gene flow.

It is likely that the majority of human diseases are caused by a complex mix of multiple genes (polygenic) and environmental factors (multifactorial). Examples of polygenic, multifactorial diseases are type II diabetes and heart disease. We do not typically think of these diseases as genetic diseases, because our genes do not predetermine whether we develop them. Our genes, however, do influence our chances of developing the diseases under certain environmental conditions. Even our chances of developing some infectious diseases are influenced by our genes. For example, a variant allele for a gene called CCR5 seems to confer resistance to infection with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

6.2 Summary

- No two human individuals are genetically identical (except for monozygotic twins), but the human species as a whole exhibits relatively little genetic diversity, relative to other mammalian species. Genetically, two people chosen at random are likely to be 99.9 per cent identical.

- Of the total genetic variation in humans, about 90 per cent occurs between people within continental populations. Only about 10 per cent occurs between people from different continents. Older, larger populations tend to have greater genetic variation, because there is more time and there are more people in which to accumulate mutations.

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms account for most human genetic differences. Allele frequencies for polymorphic genes generally have a clinal (rather than discrete) distribution. A minority of alleles seem to cluster in particular geographic areas, such as the allele for no antigen in the Duffy blood group. Such alleles may be useful as genetic markers to establish the ancestry of individuals.

- Knowledge of genetic variation can help us understand our similarities and differences. It can also help us reconstruct our evolutionary origins and history as a species. For example, the distribution of modern human genetic variation is consistent with the out-of-Africa hypothesis for the origin of modern humans.

- An important benefit of studying human genetic variation is learning more about the genetic basis of human diseases. This, in turn, should help us find more effective treatments and cures.

6.2 Review Questions

- Compare and contrast the significance of genetic variation at the individual and population levels.

- Describe genetic variation within and between human populations on different continents.

- Explain why allele frequencies for the Duffy gene may be used as a genetic marker for African ancestry.

- Identify factors that increase the level of genetic variation within populations.

-

- Discuss genetic evidence that supports the out-of-Africa hypothesis of modern human origins.

- What evidence suggests that modern humans interbred with archaic human populations after modern humans left Africa?

- How do population size reductions and gene flow impact the genetic variation of populations?

- Describe the role of genetic variation in human disease.

- Explain the reasons why variation in a DNA sequence can have no effect on the fitness of an individual.

- Explain why migration between populations decreases inter-population genetic variation. How does this relate to the development of clines in allele frequency?

- The amount of mixing of modern human DNA and archaic human DNA is an example of _________ .

6.2 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RGtaq3PiIoU

The Journey of Your Past | National Geographic, National Geographic, 2013.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kU0ei9ApmsY

Svante Pääbo: DNA clues to our inner neanderthal, TED, 2011.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=cHRM2S_fBOk&feature=emb_logo

Why Are Some People Albino?, Seeker, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 6.2.1

Maasai_men_and_tourists_jumping by Christopher Michel on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) (license.

Figure 6.2.2

Geospatial_distribution_of_SNP_rs1426654-A_allele by Basu Mallick C, Iliescu FM, Möls M, Hill S, Tamang R, Chaubey G, et al. on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en) license.

Figure 6.2.3

Mali_Salif_Keita2_400 [cropped] by unknown from The Department of State, Washington, DC. on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Basu Mallick C., Iliescu, F.M., Möls, M., Hill, S., Tamang, R., Chaubey, G., et al. (2013). The light skin allele of SLC24A5 in South Asians and Europeans shares identity by descent: Figure 2. Isofrequency map illustrating the geospatial distribution of SNP rs1426654-A allele across the world. PLoS Genetics, 9(11): e1003912. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003912 http://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1003912

HealthLinkBC. (2019, November 5). Health topics: Malaria [online article]. BC Government (gov.bc.ca). https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/hw119119

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Albinism [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/albinism/symptoms-causes/syc-20369184

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Heart disease [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20353118

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). HIV/AIDS [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hiv-aids/symptoms-causes/syc-20373524

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Type 2 diabetes [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-2-diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20351193

National Geographic. (2013, March 13). The journey of your past | National Geographic. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RGtaq3PiIoU&feature=youtu.be

National Institutes of Health/ National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Genes: CCR5 gene - C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 [online article]. US Government. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/CCR5

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). (2012). Ellis Van Creveld syndrome [online article]. RareDiseases.org. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/ellis-van-creveld-syndrome/

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD). (2017). Tay Sachs disease [online article]. RareDiseases.org. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/tay-sachs-disease/

Seeker. (2015, July 25). Why are some people albino?. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHRM2S_fBOk&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2011, August 30). Svante Pääbo: DNA clues to our inner neanderthal. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kU0ei9ApmsY&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 18). Melanesia. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Melanesia&oldid=963224885

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 4). Old world. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Old_World&oldid=960713597

The body system which acts as a chemical messenger system comprising feedback loops of the hormones released by internal glands of an organism directly into the circulatory system, regulating distant target organs. In humans, the major endocrine glands are the thyroid gland and the adrenal glands.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Ribosome Review

The 25-metre long sculpture shown in Figure 4.6.1 is a recognition of the beauty of one of the metabolic functions that takes place in the cells in your body. This artwork brings to life an important structure in living cells: the ribosome, the cell structure where proteins are synthesized. The slender silver strand is the messenger RNA(mRNA) bringing the code for a protein out into the cytoplasm. The purple and green structures are ribosomal subunits (which together form a single ribosome), which can "read" the code on the mRNA and direct the bonding of the correct sequence of amino acids to create a protein. All living cells — whether they are prokaryotic or eukaryotic — contain ribosomes, but only eukaryotic cells also contain a nucleus and several other types of organelles.

What Are Organelles?

An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell that is enclosed within a membrane and performs a specific job. Organelles are involved in many vital cell functions. Organelles in animal cells include the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, vesicles, and vacuoles. Ribosomes are not enclosed within a membrane, but they are still commonly referred to as organelles in eukaryotic cells.

The Nucleus

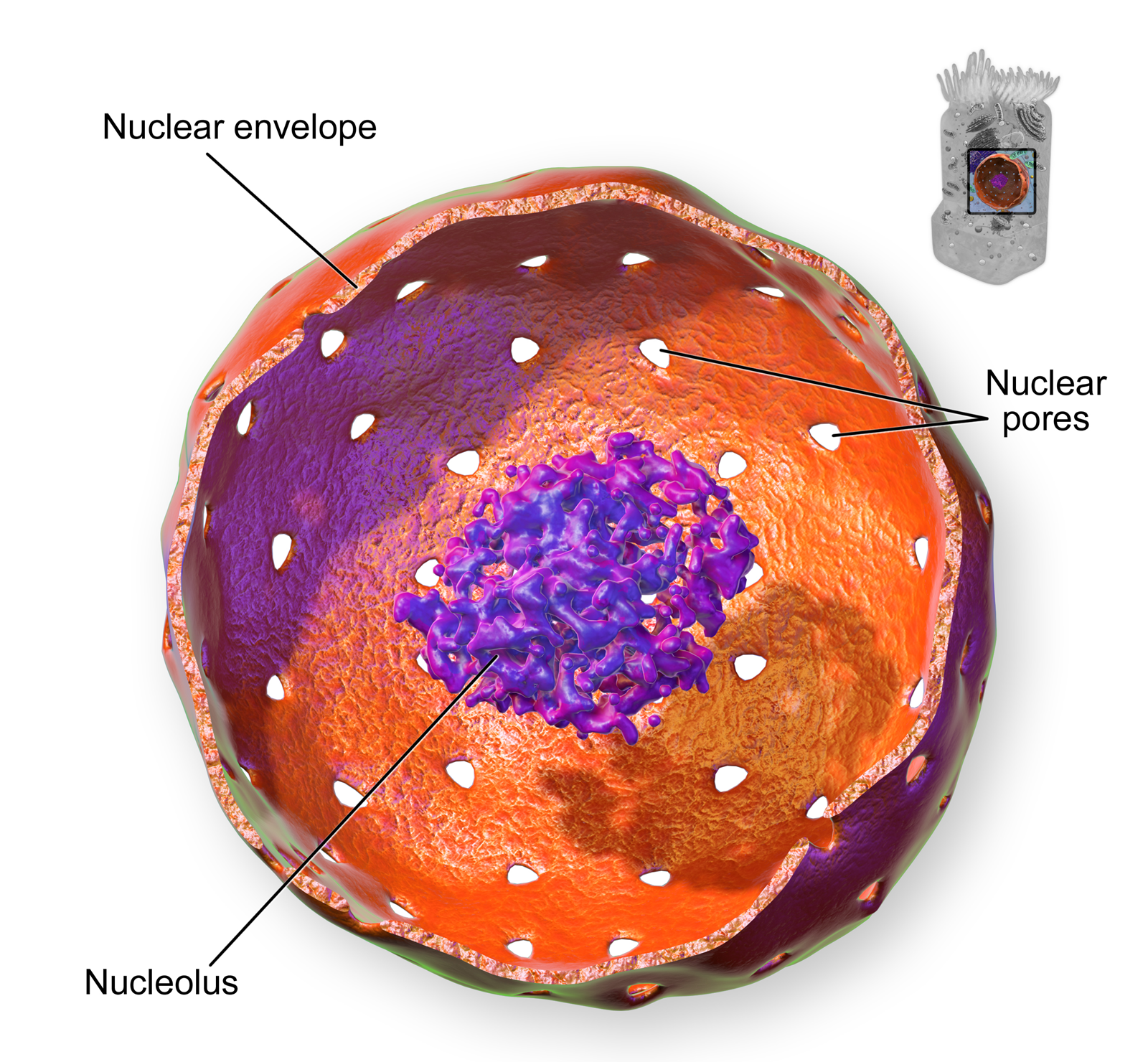

The nucleus is the largest organelle in a eukaryotic cell, and it's considered the cell’s control center. It contains most of the cell’s DNA(which makes up chromosomes), and it is encoded with the genetic instructions for making proteins. The function of the nucleus is to regulate gene expression, including controlling which proteins the cell makes. In addition to DNA, the nucleus contains a thick liquid called nucleoplasm, which is similar in composition to the cytosol found in the cytoplasm outside the nucleus. Most eukaryotic cells contain just a single nucleus, but some types of cells (such as red blood cells) contain no nucleus and a few other types of cells (such as muscle cells) contain multiple nuclei.

As you can see in the model pictured in Figure 4.6.2, the membrane enclosing the nucleus is called the nuclear envelope. This is actually a double membrane that encloses the entire organelle and isolates its contents from the cellular cytoplasm. Tiny holes called nuclear pores allow large molecules to pass through the nuclear envelope, with the help of special proteins. Large proteins and RNA molecules must be able to pass through the nuclear envelope so proteins can be synthesized in the cytoplasm and the genetic material can be maintained inside the nucleus. The nucleolus shown in the model below is mainly involved in the assembly of ribosomes. After being produced in the nucleolus, ribosomes are exported to the cytoplasm, where they are involved in the synthesis of proteins.

Mitochondria

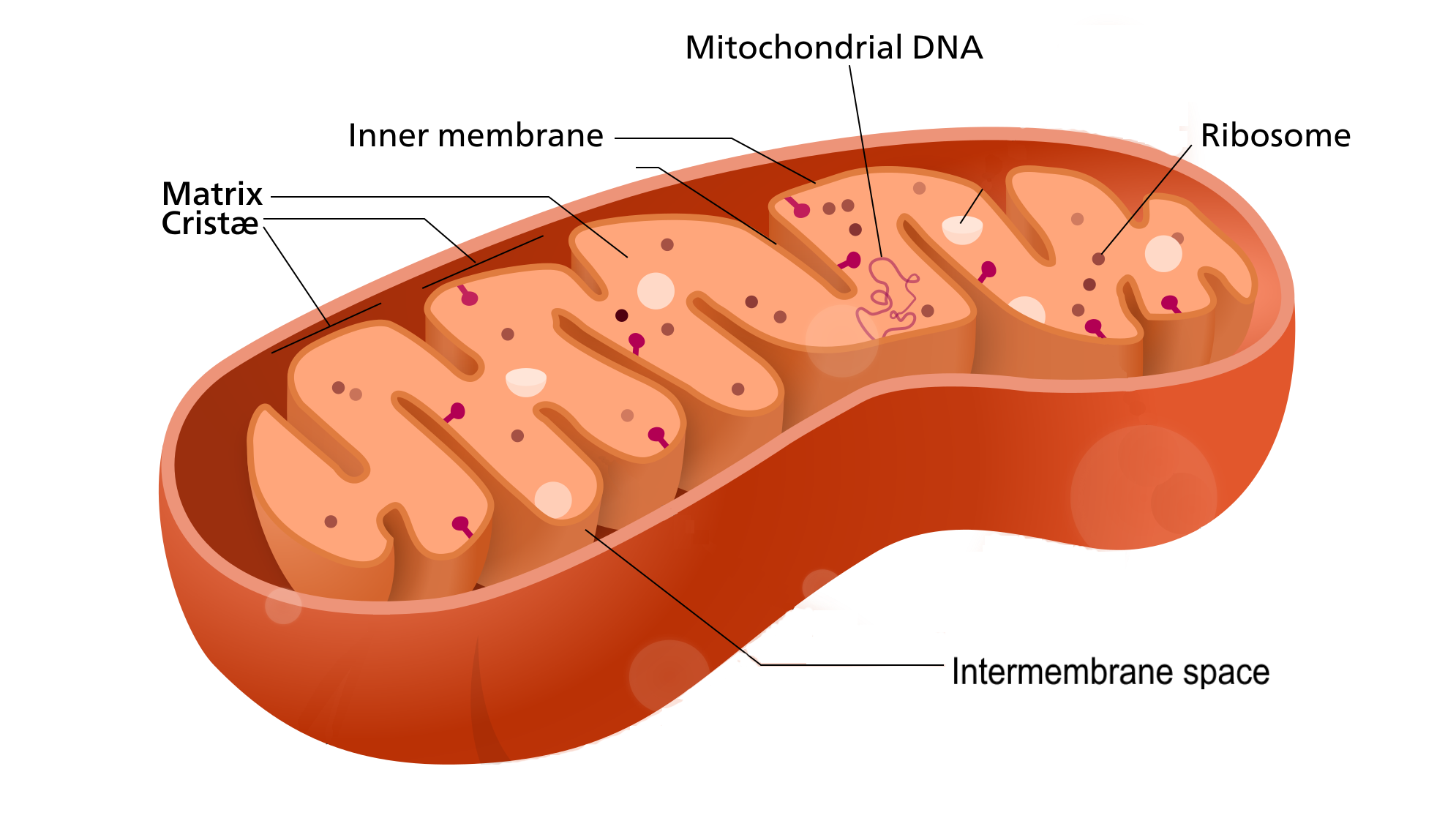

The mitochondrion (plural, mitochondria) is an organelle that makes energy available to the cell. This is why mitochondria are sometimes referred to as the "power plants of the cell." They use energy from organic compounds (such as glucose) to make molecules of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), an energy-carrying molecule that is used almost universally inside cells for energy.

Mitochondria (as in the Figure 4.6.3 diagram) have a complex structure including an inner and out membrane. In addition, mitochondria have their own DNA, ribosomes, and a version of cytoplasm, called matrix. Does this sound similar to the requirements to be considered a cell? That's because they are!

Scientists think that mitochondria were once free-living organisms because they contain their own DNA. They theorize that ancient prokaryotes infected (or were engulfed by) larger prokaryotic cells, and the two organisms evolved a symbiotic relationship that benefited both of them. The larger cells provided the smaller prokaryotes with a place to live. In return, the larger cells got extra energy from the smaller prokaryotes. Eventually, the smaller prokaryotes became permanent guests of the larger cells, as organelles inside them. This theory is called endosymbiotic theory, and it is widely accepted by biologists today. (See the video in section 4.3 to learn all about endosymbiotic theory.)

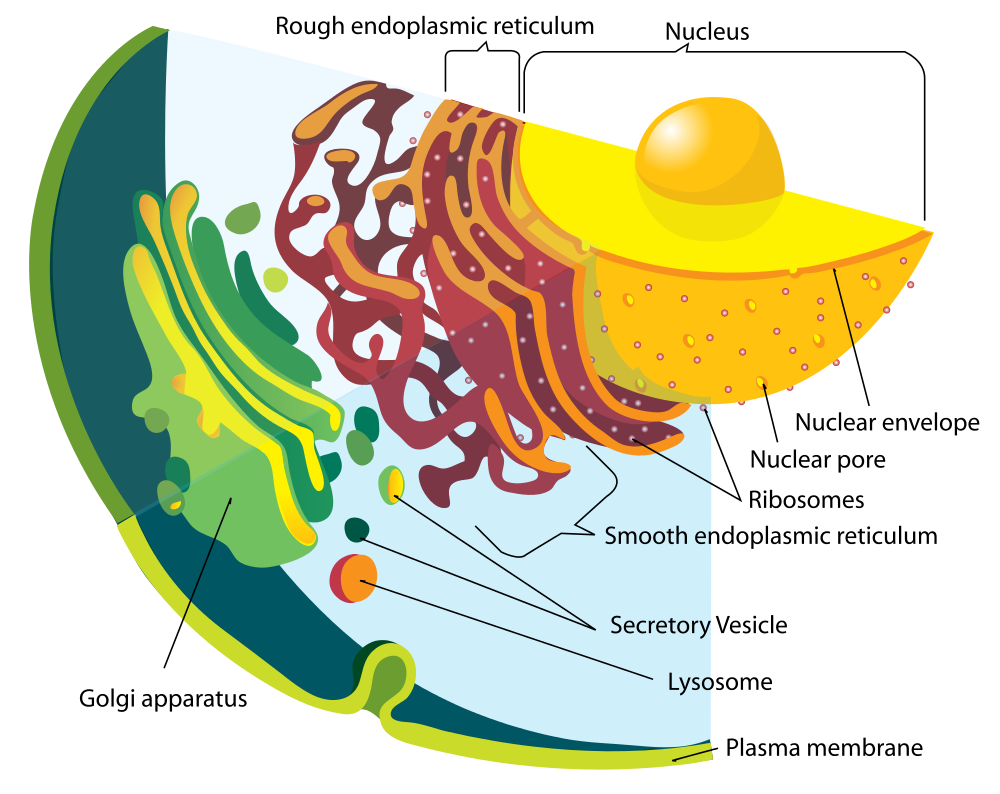

Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that helps make and transport proteins and lipids. There are two types of endoplasmic reticulum: rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER). Both types are shown in Figure 4.6.4.

- rER looks rough because it is studded with ribosomes. It provides a framework for the ribosomes, which make proteins. Bits of its membrane pinch off to form tiny sacs called vesicles, which carry proteins away from the ER.

- sER looks smooth because it does not have ribosomes. sER makes lipids, stores substances, and plays other roles.

The Figure 4.6.4 drawing includes the nucleus, rER, sER, and Golgi apparatus. From the drawing, you can see how all these organelles work together to make and transport proteins.

Golgi Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (shown in the Figure 4.6.4 diagram) is a large organelle that processes proteins and prepares them for use both inside and outside the cell. You can see the Golgi apparatus in the figure above. The Golgi apparatus is something like a post office. It receives items (proteins from the ER), then packages and labels them before sending them on to their destinations (to different parts of the cell or to the cell membrane for transport out of the cell). The Golgi apparatus is also involved in the transport of lipids around the cell.

Vesicles and Vacuoles

Both vesicles and vacuoles are sac-like organelles made of phospholipid bilayer that store and transport materials in the cell. Vesicles are much smaller than vacuoles and have a variety of functions. The vesicles that pinch off from the membranes of the ER and Golgi apparatus store and transport protein and lipid molecules. You can see an example of this type of transport vesicle in the Figure 4.6.4. Some vesicles are used as chambers for biochemical reactions.

There are some vesicles which are specialized to carry out specific functions. Lysosomes, which use enzymes to break down foreign matter and dead cells, have a double membrane to make sure their contents don't leak into the rest of the cell. Peroxisomes are another type of specialized vesicle with the main function of breaking down fatty acids and some toxins.

Centrioles

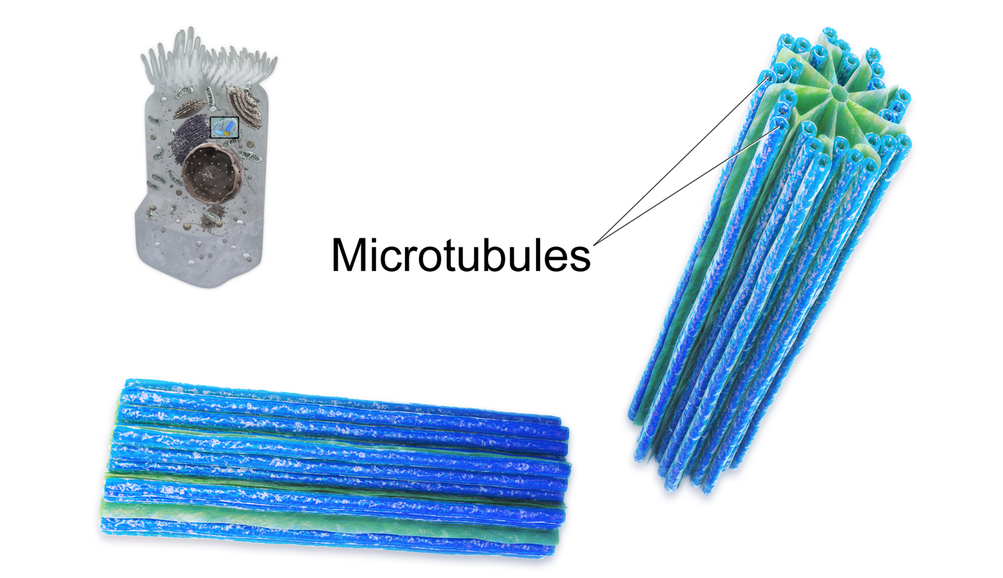

Centrioles are organelles involved in cell division. The function of centrioles is to help organize the chromosomes before cell division occurs so that each daughter cell has the correct number of chromosomes after the cell divides. Centrioles are found only in animal cells, and are located near the nucleus. Each centriole is made mainly of a protein named tubulin. The centriole is cylindrical in shape and consists of many microtubules, as shown in the model pictured in Figure 4.6.5.

Ribosomes

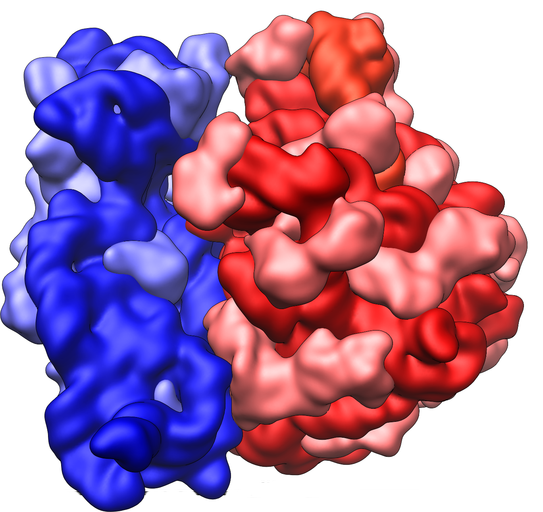

Ribosomes are small structures where proteins are made. Although they are not enclosed within a membrane, they are frequently considered organelles. Each ribosome is formed of two subunits, like the ones pictured at the beginning of this section (Figure 4.6.1) and in Figure 4.6.6. Both subunits consist of proteins and RNA. mRNA from the nucleus carries the genetic code, copied from DNA, which remains in the nucleus. At the ribosome, the genetic code in mRNA is used to assemble and join together amino acids to make proteins. Ribosomes can be found alone or in groups within the cytoplasm, as well as on the rER.

4.6 Summary

- An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell that is enclosed within a membrane and performs a specific job. Although ribosomes are not enclosed within a membrane, they are still commonly referred to as organelles in eukaryotic cells.

- The nucleus is the largest organelle in a eukaryotic cell, and it is considered to be the cell's control center. It controls gene expression, including controlling which proteins the cell makes.

- The mitochondrion (plural, mitochondria) is an organelle that makes energy available to the cells. It is like the power plant of the cell. According to the widely accepted endosymbiotic theory, mitochondria evolved from prokaryotic cells that were once free-living organisms that infected or were engulfed by larger prokaryotic cells.

- The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that helps make and transport proteins and lipids. Rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) is studded with ribosomes. Smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER) has no ribosomes.

- The Golgi apparatus is a large organelle that processes proteins and prepares them for use both inside and outside the cell. It is also involved in the transport of lipids around the cell.

- Both vesicles and vacuoles are sac-like organelles that may be used to store and transport materials in the cell or as chambers for biochemical reactions. Lysosomes and peroxisomes are special types of vesicles that break down foreign matter, dead cells, or poisons.

- Centrioles are organelles located near the nucleus that help organize the chromosomes before cell division so each daughter cell receives the correct number of chromosomes.

- Ribosomes are small structures where proteins are made. They are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. They may be found alone or in groups within the cytoplasm or on the rER.

4.6 Review Questions

- What is an organelle?

- Describe the structure and function of the nucleus.

- Explain how the nucleus, ribosomes, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus work together to make and transport proteins.

- Why are mitochondria referred to as the "power plants of the cell"?

- What roles are played by vesicles and vacuoles?

- Why do all cells need ribosomes — even prokaryotic cells that lack a nucleus and other cell organelles?

- Explain endosymbiotic theory as it relates to mitochondria. What is one piece of evidence that supports this theory?

-

4.6 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URUJD5NEXC8&t=121s

Biology: Cell Structure I Nucleus Medical Media, Nucleus Medical Media, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Id2rZS59xSE&feature=youtu.be

David Bolinsky: Visualizing the wonder of a living cell, TED, 2007.

Attributes

Figure 4.6.1

Ribosomes at Work by Pedrik on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 4.6.2

Nucleus by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.3

Mitochondrion_structure.svg by Kelvinsong; modified by Sowlos on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.4

Endomembrane_system_diagram_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.6.5

Centrioles by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.6

Ribosome_shape by Vossman on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

References

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Nucleus - Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Medicine/Medical_gallery_of_Blausen_Medical_2014

Blausen.com staff (2014). Centrioles - Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Medicine/Medical_gallery_of_Blausen_Medical_2014

Nucleus Medical Media. (2015, March 18). Biology: Cell structure I Nucleus Medical Media. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URUJD5NEXC8&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2007, July 24). David Bolinsky: Visualizing the wonder of a living cell. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Id2rZS59xSE&feature=youtu.be

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Figure 6.3.1 How would you classify these people?

Why Classify?

What do you see when you look at Figure 6.3.1? Did you sort individuals into categories based in gender, age, body type, facial features, skin colour or other characteristics? As humans, we seem to have a penchant for classifying and labeling people and things. It helps us establish a sense of order in the world around us. The 18th century taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, for example, classified virtually all known living things into different species, genera, families, and other taxonomic categories. His classifications were based on observable phenotypic characteristics, such as skin colour. Modern biological classifications of living things are usually based on phylogenetic relationships. Phylogenies reflect evolutionary history and group together living things that are related by descent from a common ancestor.

Starting with Linnaeus and continuing to the present, scientists and others have attempted to classify human variation. There are three basic approaches to classification: typological, populational, and clinal.

Typological Approach

The typological approach involves creating a typology, which is a system of discrete types, or categories. This approach was widely used by scientists up through the early 20th century. Racial classifications are typological classifications. They place people into a small number of discrete categories, or races, based on a few readily observable traits, such as skin colour, hair texture, facial features, and body build.

Racial Classifications and Racism

Racial classifications of humans probably go back as long as people distinguished “us” from “them.” An early “scientific” classification of humans into races is Linnaeus’ 1735 classification. He divided Homo sapiens into continental races, which he named europaeus, asiaticus, americanus, and afer. Linnaeus described these races in terms of observable physical traits. He also associated, inaccurately, each race with different personality qualities and behaviors. For example, he described Homo sapiens europaeus as active and adventurous and Homo sapiens afer as lazy and careless. In 1795, the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach proposed five major races of Homo sapiens, which he named the caucasoid, mongoloid, negroid, American Indian, and Malayan races. Blumenbach thought that the caucasoid race was the original race, and that the other races arose in a process of “degeneration” from the caucasoids.

In 1870, the English biologist Thomas Huxley classified Homo sapiens into nine races which were distributed geographically. The map in Figure 6.3.2 shows how Huxley thought the races were distributed worldwide. Each colour represents one of Huxley’s proposed races. These categories included “Australoid,” “Xanthochroi,” “Melanochori,” “Negroes,” and “Mongoloids,” and they are not used today. It should be noted that Huxley did not hold such strong negative stereotypes about non-European (or non-caucasoid) races as did his intellectual forebears. Huxley, however, still attributed different behaviors to racial groups that had nothing to do with the colour of their skin or continent of origin.

By the early 20th century, so-called scientific racism was a popular ideology. This was the idea that race is a biological concept and that human behavior is partly determined by race. At around 1950, in a series of groundbreaking studies of skeletal anatomy, anthropologist Franz Boas showed that cranial (skull) shape and size were highly malleable, depending on environmental factors (such as health and nutrition). He contrasted this with racial anthropologists' claims that head shape is a stable racial trait. In this way, Boas demonstrated that this commonly used racial trait was determined by the environment, and not just genes. Boas also worked to demonstrate that differences in human behavior are not determined primarily by innate biological dispositions, but are largely the result of cultural differences acquired through social learning.

Unfortunately, racism still persists today — in society at large, if not in science. This is the association of racial traits (such as skin colour) with unrelated traits (such as intelligence), often leading to prejudice and discrimination against people based only on how they look. The concept of human race is real, not in a biological sense, but in a social sense. Racial stereotypes and racism are deeply ingrained in our history and culture, and they have real material effects on human lives.

Additional Problems with Typological Classification

Besides the problem of racism, there are other problems with typological approaches to the biological classification of Homo sapiens. One problem is that most human biological traits are not either present or absent, but instead vary on a continuum. This type of distribution cannot be adequately represented by discrete categories, such as races. The typological approach also results in groupings of people that may be similar in terms of some traits, but not others. How people are grouped together depends on which traits are chosen. In addition, the number of groups that are needed to classify people depends on the number of traits that are used. The greater the number of traits, the greater the number of racial categories there must be. If racial categories depend on the traits chosen to define them, it is clear that the racial classifications are arbitrary and do not reflect biological reality.

Another problem with typological classifications is that they lead to the mistaken belief that people within typological categories are more similar to each other than they are to people in other categories. There is actually more variation within than between typological groups. An estimated 90 per cent of human genetic variation occurs between people within races, and only 10 per cent occurs between races. Clearly, races are far from homogenous in terms of their genetic composition. In short, we are all more alike than we are different.

Populational Approach

By the middle of the 20th century, scientists started advocating a populational approach to classifying Homo sapiens. This approach is based on the idea that the breeding population is the only biologically meaningful group. The breeding population is the unit of evolution, and it includes people who have mated and produced offspring together for many generations. As a result, members of the same breeding population should share many genetic traits. You would also expect them to have many of the same phenotypic traits, because of their similar genetic makeup.

While the populational approach makes sense in theory, in reality, it can rarely be applied, because most human populations are not closed breeding populations. Some people have always selected mates from outside their local population (even mating with archaic humans such as Neanderthals). This tendency has increased dramatically in recent centuries with the advent of efficient means of traveling long distances. As a consequence, there are very few remaining distinct breeding populations within the human species.

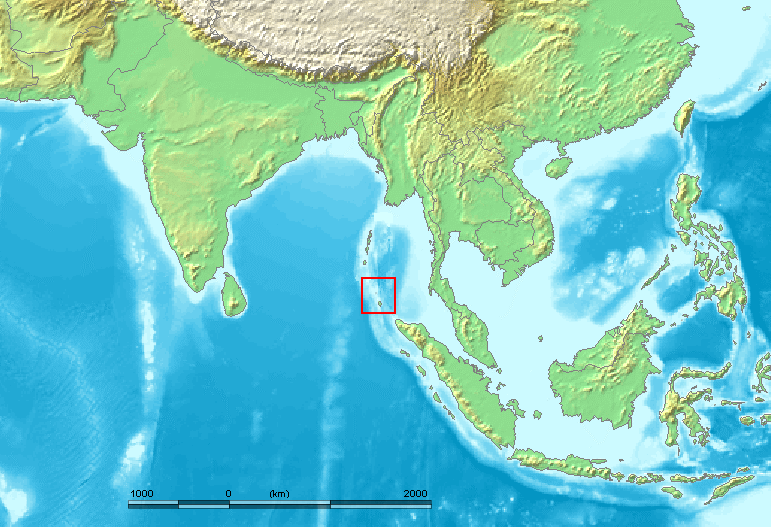

An example of one such population is the Sentinelese, a small population of hunter-gatherers who live alone on a small island in the Andaman Islands (see the map). The Sentinelese are thought to be direct descendants of the first modern humans to leave Africa, and they may have lived in the Andaman Islands for as long as 60 thousand years. The Sentinelese are also one of the most isolated human populations on Earth. The fact that their language is distinctly different from other Andaman Islands languages is evidence that they have had little contact with other people for thousands of years. Although closed breeding populations (such as the Sentinelese) may be useful for investigating questions about evolutionary processes, they are not useful for classifying most of humanity.

Clinal Approach

By the 1960s, scientists began to use a clinal approach to classify human variation. This approach maps variation in traits over geographic regions (such as continents) or even worldwide. Clinal models are a useful way of describing human variation that does not lead to discrete races or other categories of people.

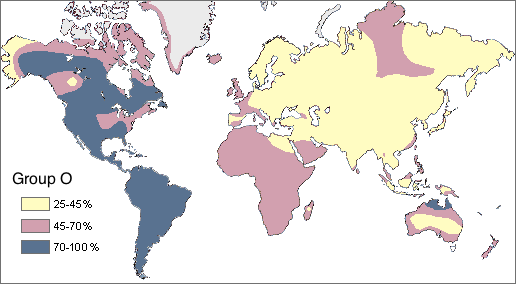

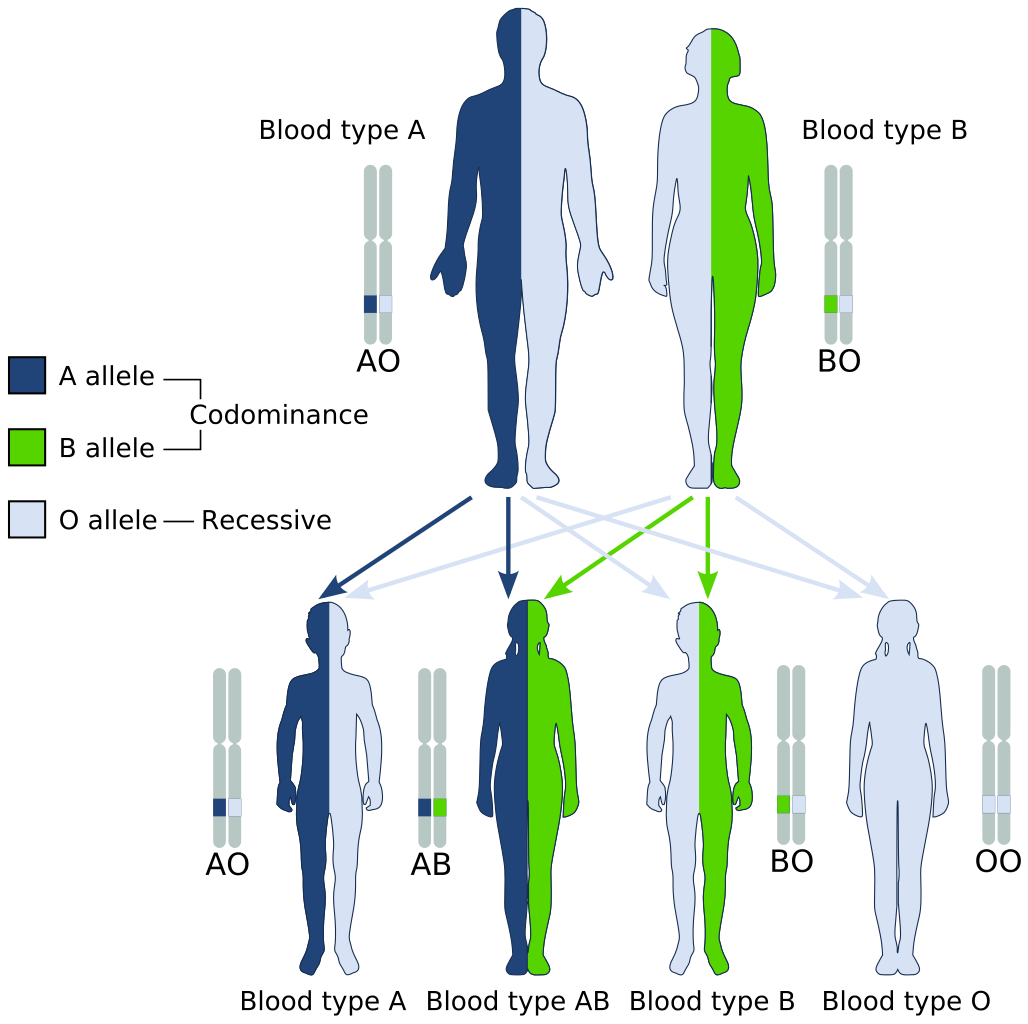

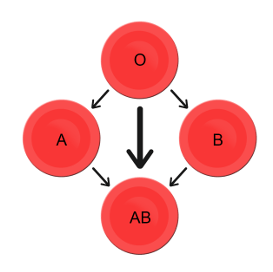

In Figure 6.3.4 you can see a worldwide clinal map for type O blood in the human ABO blood group system. The frequency of this trait is shown for the indigenous populations of various regions. It is lowest throughout Asia and highest in Native American populations in both North and South America. This geographic distribution results from the complex interaction of a variety of factors, including natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow. You can read more about geographic variation in blood types in the concept Variation in Blood Types.

Clinal maps for many genetic traits show variation that changes gradually from one geographic area to another, which may happen because of the nature of gene flow. Gene flow occurs when mating takes place between people in different populations. The likelihood of mating with others depends on their distance from us. You may not marry the boy or girl next door, but your mate is more likely to be someone in the same state or country than someone on another continent.

Natural selection has a major impact on the clinal distribution of some traits, because variation in the traits tracks variation in selective pressures. For example, the environmental stressor of malaria varies throughout Africa with climate, as you can see in the left-hand map below (Figure 6.3.5). The sickle cell trait that protects from malaria has a similar distribution, as shown in the right-hand map.

Figure 6.3.5

6.3 Summary

- Humans seem to have a need to classify and label people based on their similarities and differences. Three approaches to classifying human variation include typological, populational, and clinal approaches.

- The typological approach involves creating a typology, which is a system of discrete categories, or races. This approach was widely used by scientists until the early 20th century. Racial categories are based on observable phenotypic traits (such as skin colour), but other traits and behaviors are often assumed to apply to racial groups, as well. The use of racial classifications often leads to racism.

- By the mid-20th century, scientists started advocating a population approach. This assumes that the breeding population, which is the unit of evolution, is the only biologically meaningful group. While this approach makes sense in theory, in reality, it can rarely be applied to actual human populations. With few exceptions, most human populations are not closed breeding populations.

- By the 1960s, scientists began to use a clinal approach to classify human variation. This approach maps variation in the frequency of traits or alleles over geographic regions or worldwide. Clinal maps for many genetic traits show variation that changes gradually from one geographic area to another. This type of distribution may result from gene flow and/or natural selection.

6.3 Review Questions

- Name the 18th century taxonomist that classified virtually all known living things.

- Describe the typological approach to classifying human variation.

- Discuss why typological classifications of Homo sapiens are associated with racism.

- Why is the breeding population considered to be the most meaningful biological group?

- Explain why it is generally unrealistic to apply a populational approach to classifying the human species.

- What does a clinal map show?

- Explain how gene flow and natural selection can result in a gradual change in the frequency of a trait over geographic space.

- Most human traits vary on a continuum. Explain why this presents a problem for the typological classification approach.

-

6.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ntimKsWDUpA&feature=emb_logo

The Biology of Race in the Absence of Biological Races,

Centre for Genetic Medicine, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOSPNVunyFQ

Nina Jablonski breaks the illusion of skin color, TED, 2009.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r4c2NT4naQ

The science of skin color - Angela Koine Flynn, TED-Ed, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 6.3.1

- Three women sitting by flowers and laughing by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Two women sitting on sofa by AllGo on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Young people in conversation by Alexis Brown on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Men talking in the cold by Anna Vander Stel on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Laughing by the tracks by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 6.3.2

Huxley_races by Wobble on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.3.3

Nicobar_Islands is edited by M.Minderhoud on Wikimedia Commons, and was released into the public domain by its original author, www.demis.nl. (See also approval email on de.wp and its clarification.)

Figure 6.3.4

Map_of_Group_O/ (Percent of Native population that has the O blood type) by Ephert on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en) license. (Original Spanish edition by Maulucioni)

Figure 6.3.5

- Malaria distribution by Muntuwandi at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

- Sickle cell distribution by Muntuwandi at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

References

Centre for Genetic Medicine. (2015, July 14). The biology of race in the absence of biological races. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ntimKsWDUpA&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2009, August 7). Nina Jablonski breaks the illusion of skin color. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QOSPNVunyFQ&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2016, February 16). The science of skin color - Angela Koine Flynn. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r4c2NT4naQ&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 27). Carl Linnaeus. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Carl_Linnaeus&oldid=964690855

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 18). Franz Boas. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Franz_Boas&oldid=957282443

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 5). Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Johann_Friedrich_Blumenbach&oldid=966196943

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 11). Sentinelese. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sentinelese&oldid=967121254

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 14). Thomas Henry Huxley. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thomas_Henry_Huxley&oldid=967701553

A hormone is a signaling molecule produced by glands in multicellular organisms that target distant organs to regulate physiology and behavior.

Structures containing neuronal cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Oh, the Agony!

Wearing braces can be very uncomfortable, but it is usually worth it. Braces and other orthodontic treatments can re-align the teeth and jaws to improve bite and appearance. Braces can change the position of the teeth and the shape of the jaws because the human body is malleable. Many phenotypic traits — even those that have a strong genetic basis — can be molded by the environment. Changing the phenotype in response to the environment is just one of several ways we respond to environmental stress.

Types of Responses to Environmental Stress

There are four different types of responses that humans may make to cope with environmental stress:

- Adaptation

- Developmental adjustment

- Acclimatization

- Cultural responses

The first three types of responses are biological in nature, and the fourth type is cultural. Only adaptation involves genetic change and occurs at the level of the population or species. The other three responses do not require genetic change, and they occur at the individual level.

Adaptation

An adaptation is a genetically-based trait that has evolved because it helps living things survive and reproduce in a given environment. Adaptations generally evolve in a population over many generations in response to stresses that last for a long period of time. Adaptations come about through natural selection. Those individuals who inherit a trait that confers an advantage in coping with an environmental stress are likely to live longer and reproduce more. As a result, more of their genes pass on to the next generation. Over many generations, the genes and the trait they control become more frequent in the population.

A Classic Example: Hemoglobin S and Malaria