7.6 Human Body Cavities

Contain the Brain

You probably recognize the colourful object in this photo (Figure 7.6.1) as a human brain. The brain is arguably the most important organ in the human body. Fortunately for us, the brain has its own special “container,” called the cranial cavity. The cranial cavity enclosing the brain is just one of several cavities in the human body that form “containers” for vital organs.

What Are Body Cavities?

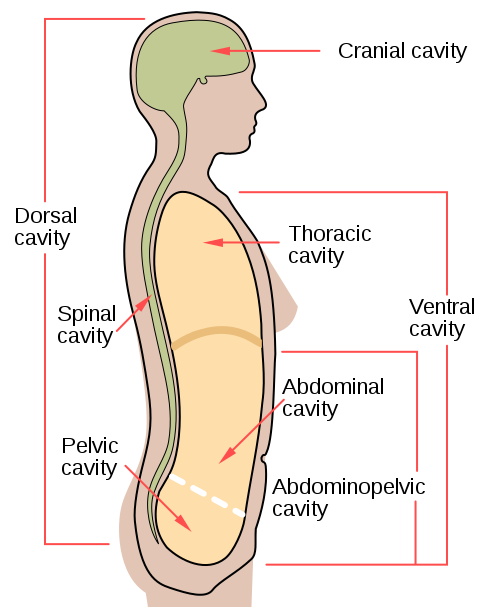

The human body, like that of many other multicellular organisms, is divided into a number of body cavities. A body cavity is a fluid-filled space inside the body that holds and protects internal organs. Human body cavities are separated by membranes and other structures. The two largest human body cavities are the ventral cavity and dorsal cavity. These two body cavities are subdivided into smaller body cavities. Both the dorsal and ventral cavities and their subdivisions are shown in the Figure 7.6.2 diagram.

Ventral Cavity

The ventral cavity is at the anterior (or front) of the trunk. Organs contained within this body cavity include the lungs, heart, stomach, intestines, and reproductive organs. The ventral cavity allows for considerable changes in the size and shape of the organs inside as they perform their functions. Organs such as the lungs, stomach, or uterus, for example, can expand or contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activities of nearby organs.

The ventral cavity is subdivided into the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities.

- The thoracic cavity fills the chest and is subdivided into two pleural cavities and the pericardial cavity. The pleural cavities hold the lungs, and the pericardial cavity holds the heart.

- The abdominopelvic cavity fills the lower half of the trunk and is subdivided into the abdominal cavity and the pelvic cavity. The abdominal cavity holds digestive organs and the kidneys, and the pelvic cavity holds reproductive organs and organs of excretion.

Dorsal Cavity

The dorsal cavity is at the posterior (or back) of the body, including both the head and the back of the trunk. The dorsal cavity is subdivided into the cranial and spinal cavities.

- The cranial cavity fills most of the upper part of the skull and contains the brain.

- The spinal cavity is a very long, narrow cavity inside the vertebral column. It runs the length of the trunk and contains the spinal cord.

The brain and spinal cord are protected by the bones of the skull and the vertebrae of the spine. They are further protected by the meninges, a three-layer membrane that encloses the brain and spinal cord. A thin layer of cerebrospinal fluid is maintained between two of the meningeal layers. This clear fluid is produced by the brain, and it provides extra protection and cushioning for the brain and spinal cord.

Feature: My Human Body

The meninges membranes that protect the brain and spinal cord inside their cavities may become inflamed, generally due to a bacterial or viral infection. This condition is called meningitis, and it can lead to serious long-term consequences such as deafness, epilepsy, or cognitive deficits, especially if not treated quickly. Meningitis can also rapidly become life-threatening, so it is classified as a medical emergency.

Learning the symptoms of meningitis may help you or a loved one get prompt medical attention if you ever develop the disease. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or altered consciousness, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light or loud noises. Young children often exhibit less specific symptoms, such as irritability, drowsiness, or poor feeding.

Meningitis is diagnosed with a lumbar puncture (commonly known as a “spinal tap”), in which a needle is inserted into the spinal canal to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid. The fluid is analyzed in a medical lab for the presence of pathogens. If meningitis is diagnosed, treatment consists of antibiotics and sometimes antiviral drugs. Corticosteroids may also be administered to reduce inflammation and the risk of complications (such as brain damage). Supportive measures such as IV fluids may also be provided.

Some types of meningitis can be prevented with a vaccine. Ask your health care professional whether you have had the vaccine or should get it. Giving antibiotics to people who have had significant exposure to certain types of meningitis may reduce their risk of developing the disease. If someone you know is diagnosed with meningitis and you are concerned about contracting the disease yourself, see your doctor for advice.

7.6 Summary

- The human body is divided into a number of body cavities, fluid-filled spaces in the body that hold and protect internal organs. The two largest human body cavities are the ventral cavity and dorsal cavity.

- The ventral cavity is at the anterior (or front) of the trunk. It is subdivided into the thoracic cavity and abdominopelvic cavity.

- The dorsal cavity is at the posterior (or back) of the body, and includes the head and the back of the trunk. It is subdivided into the cranial cavity and spinal cavity.

7.6 Review Questions

-

- What is a body cavity?

- Compare and contrast the ventral and dorsal body cavities.

- Identify the subdivisions of the ventral cavity, and the organs each contains.

- Describe the subdivisions of the dorsal cavity and their contents.

- Identify and describe all the tissues that protect the brain and spinal cord.

- What do you think might happen if fluid were to build up excessively in one of the body cavities?

- Explain why a woman’s body can accommodate a full-term fetus during pregnancy without damaging her internal organs.

- Which body cavity does the needle enter in a lumbar puncture?

- What are the names given to the three body cavity divisions where the heart is located?What are the names given to the three body cavity divisions where the kidneys are located?

-

7.6 Explore More

Why is meningitis so dangerous? – Melvin Sanicas, TED-Ed, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 7.6.1

Brain Lobes by John A Beal, Department of Cellular Biology & Anatomy, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Shreveport on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en) license.

Figure 7.6.2

body_cavities-en.svg by Mysid (SVG) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (Original by US National Cancer Institute [NCI].)

References

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Meningitis. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/meningitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350508

TED-Ed. (2018, November 19). Why is meningitis so dangerous? – Melvin Sanicas. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IaQdv_dBDqM&feature=youtu.be

A fluid-filled space inside the body that holds and protects internal organs.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Can You Code?

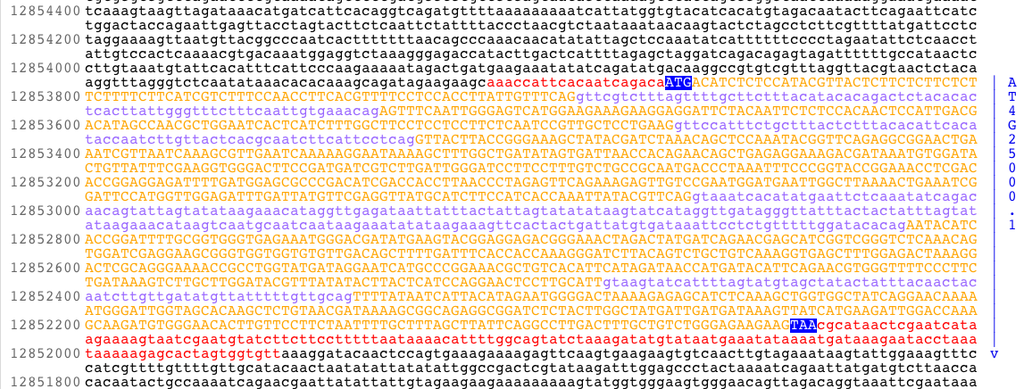

If someone asks you whether you can code, you probably assume they are referring to computer code. The image in Figure 5.6.1 represents an important code that you use all the time — but not with a computer! It's the genetic code, and it is used by your cells to store information, as well as to make RNA and proteins.

What Is the Genetic Code?

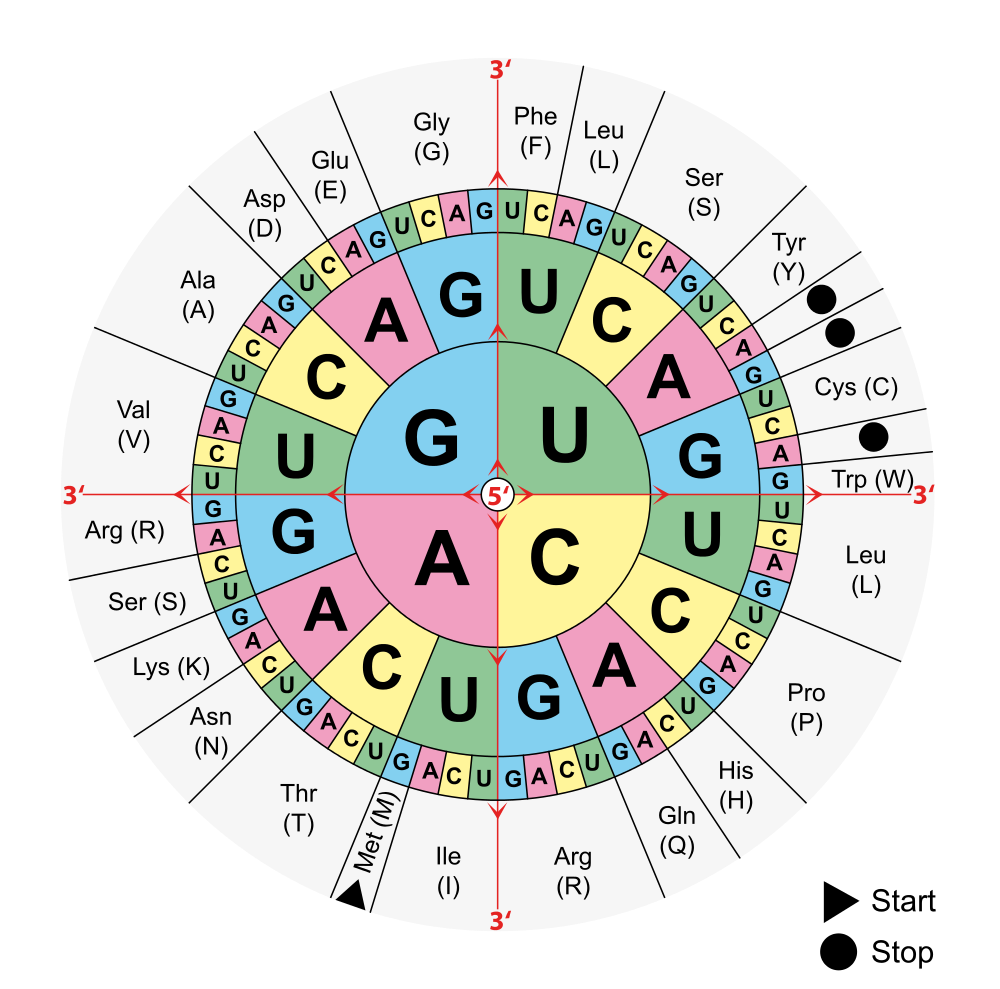

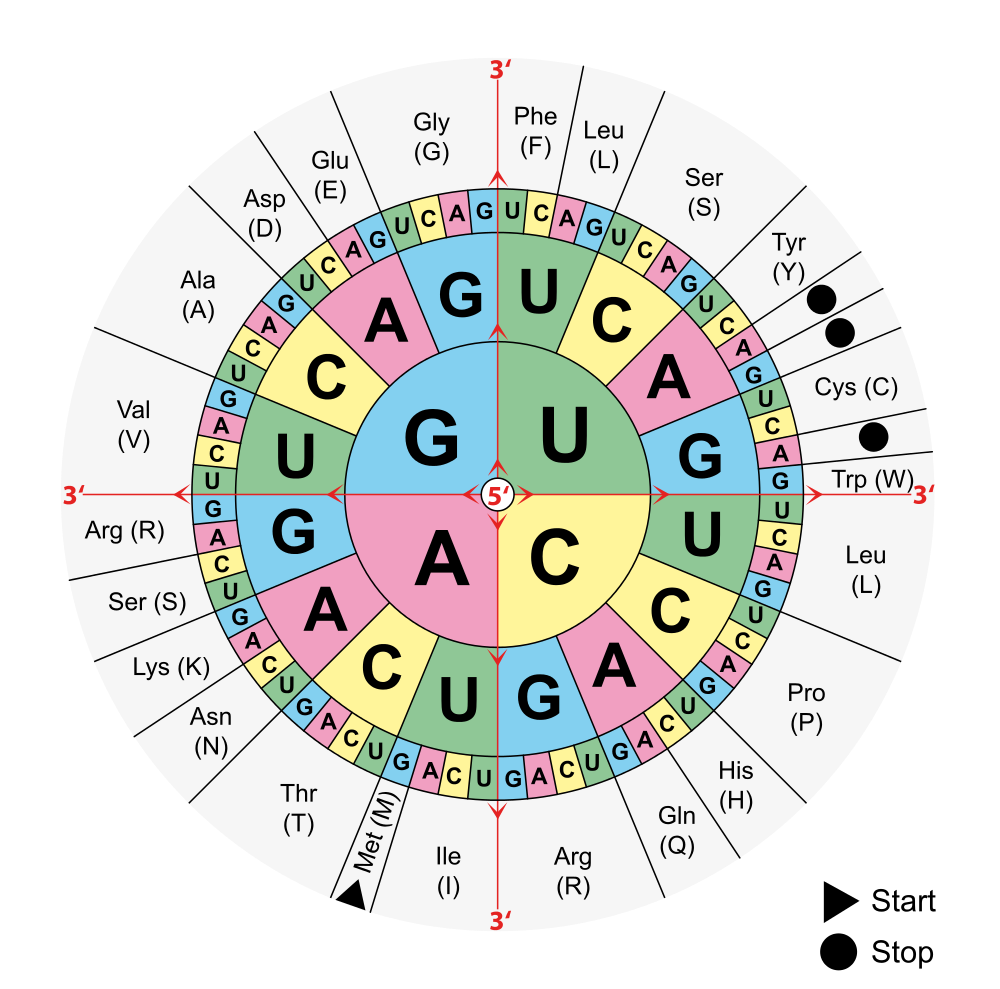

The genetic code consists of the sequence of nitrogen bases in a polynucleotide chain of DNA or RNA. The bases are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T) (or uracil, U, in RNA). The four bases make up the “letters” of the genetic code. The letters are combined in groups of three to form code “words,” called codons. Each codon stands for (encodes) one amino acid, unless it codes for a start or stop signal. There are 20 common amino acids in proteins. With four bases forming three-base codons, there are 64 possible codons. This is more than enough to code for the 20 amino acids. The genetic code is shown in Figure 5.6.2.

To find the amino acid for a particular codon, find the first base in the codon in the centre of the circle in Figure 5.6.2, then the second base in the middle row out from the center, and finally the third base in the outer ring For example, CUG codes for leucine, AAG codes for lysine, and GGG codes for glycine. Try it out: Can you figure out what the codon AGC codes for?

Reading the Genetic Code

If you find the codon AUG in Figure 5.6.2, you will see that it codes for the amino acid methionine. This codon is also the start codon that establishes the reading frame of the code. The start codon is a necessary tool in translation, since a single chromosome contains many genes. In order to transcribe and translate a gene for a specific protein, we need to know where in the DNA code to start "reading" the instructions. AUG signals the start of a reading frame. After the AUG start codon, the next three bases are read as the second codon. The next three bases after that are read as the third codon, and so on. The sequence of bases is read, codon by codon, until a stop codon is reached. UAG, UGA, and UAA are all stop codons. They do not code for any amino acids.

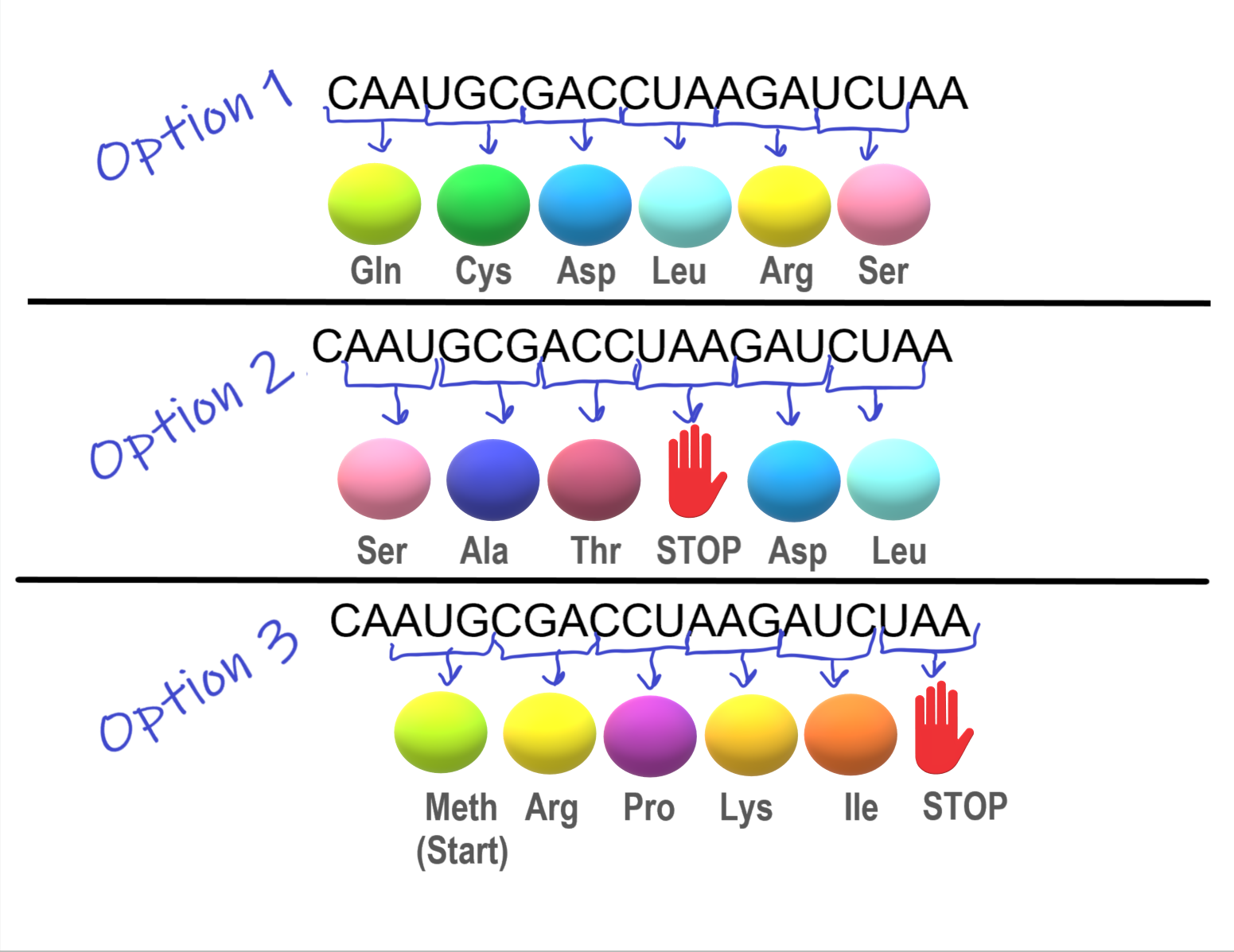

The importance of the reading frame is illustrated in the hypothetical situation below:

The section of mRNA in Figure 5.6.3 is designed to create a chain of five specific amino acids.

- In Option 1, a string of amino acids is created, but the chain does not have a stop codon, and so keeps on adding amino acids. This means the desired protein was not made.

- In Option 2, a stop codon was encountered and the amino acid chain was stopped after 3 amino acids. This means the desired protein was not made

- In Option 3, using the AUG start codon, a chain of five specific amino acids was successfully formed. Success! This was only possible because the start codon, AUG, specified the reading frame.

Characteristics of the Genetic Code

The genetic code has a number of important characteristics:

- The genetic code is universal. All known living things have the same genetic code, which shows that all organisms share a common evolutionary history.

- The genetic code is unambiguous. This means that each codon codes for just one amino acid (or start or stop). This is necessary so there is no question about which amino acid is correct.

- The genetic code is redundant. This means that each amino acid is encoded by more than one codon. For example, in Figure 5.6.2, four codons code for the amino acid threonine. Redundancy in the code helps prevent errors in protein synthesis. If a base in a codon changes by accident, there is a good chance that it will still code for the same amino acid.

Cracking the Code

The double helix structure of DNA was discovered in 1953. It took just eight more years to crack the genetic code. The scientist primarily responsible for deciphering the code was American biochemist Marshall Nirenberg, who worked at the National Institutes of Health in the United States. When Nirenberg began the research in 1959, the manner in which proteins are synthesized in cells was not well understood, and messenger RNA had not yet been discovered. At that time, scientists didn't even know whether DNA or RNA was the molecule used as a template for protein synthesis. Nirenberg, along with a collaborator named Heinrich Matthaei, devised an ingenious experiment to determine which molecule — DNA or RNA — has this important role. They also began deciphering the genetic code.

Nirenberg and Matthaei added the contents of bacterial cells to each of 20 test tubes. The cell contents provided the necessary "machinery" for the synthesis of a polypeptide molecule. The researchers also added all 20 amino acids to the test tubes, with a different amino acid "tagged" by a radioactive element in each test tube. That way, if a polypeptide formed in a test tube, they would be able to tell which amino acid it contained. Then, they added synthetic RNA containing just one nitrogen base to all 20 test tubes. They used the base uracil in their first experiment. They discovered that an RNA chain consisting only of uracil bases produces a polypeptide chain of the amino acid phenylalanine. This experiment showed that RNA (rather than DNA) is the template for protein synthesis, but it also showed that a sequence of uracil bases codes for the amino acid phenylalanine. The year was 1961, and it was a momentous occasion. When Nirenberg presented the discovery at a scientific conference later that year, he received a standing ovation. As Nirenberg puts it, "...for the next five years I became like a scientific rock star."

After Nirenberg and Matthaei cracked the first word of the genetic code, they used similar experiments to show that each codon consists of three bases. Before long, they had discovered the codons for all 20 amino acids. In 1968, in recognition of this important achievement, Nirenberg was named a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

5.6 Summary

- The genetic code consists of the sequence of nitrogen bases in a polynucleotide chain of DNA or RNA. The four bases make up the "letters" of the code. The letters are combined in groups of three to form code "words" known as codons, each of which encodes for one amino acid or a start or stop signal.

- AUG is the start codon, and it establishes the reading frame of the code. After the start codon, the next three bases are read as the second codon, the three bases after that as the third codon, and so on until a stop codon is reached.

- The genetic code is universal, unambiguous, and redundant.

- The genetic code was cracked in the 1960s, mainly by a series of ingenious experiments carried out by Marshall Nirenberg, who won a Nobel Prize for this achievement.

5.6 Review Questions

- Describe the genetic code and explain how it is "read"

- Identify three important characteristics of the genetic code.

- Summarize how the genetic code was deciphered.

- Use the decoder above to answer the following questions:

- Is the code from DNA or RNA? How do you know?

- Which amino acid does the codon CAA code for?

- What does UGA code for?

- Look at the codons that code for the amino acid glycine. How many of them are there and how are they similar and different?

-

5.6 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSKwuOccAak&feature=emb_logo

Comparing DNA Sequences, Bozeman Science, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsEYgwuP6ko

How to Read a Codon Chart, Amoeba Sisters, 2019.

Attributions

Figure 5.6.1

AMY1gene by unknown author from National Science Foundation on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 5.6.2

Aminoacids table (Adapted) by Mouagip on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain. (Original: Codons sun ("codesonne" in German) by Onie~commonswiki])

Figure 5.6.3

Reading Frame (3 Options) by Christine Miller is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) license.

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2019, September 17). How to read a codon chart. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsEYgwuP6ko&feature=youtu.be

Bozeman Science. (2012, September 15). Comparing DNA sequences. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSKwuOccAak&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 2). Marshall Warren Nirenberg. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Marshall_Warren_Nirenberg&oldid=965562106

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Mutant Cosplay

You probably recognize these costumed comic fans in Figure 5.8.1 as two of the four Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Can a mutation really turn a reptile into an anthropomorphic superhero? Of course not — but mutations can often result in other drastic (but more realistic) changes in living things.

What Are Mutations?

Mutations are random changes in the sequence of bases in DNA or RNA. The word mutation may make you think of the Ninja Turtles, but that's a misrepresentation of how most mutations work. First of all, everyone has mutations. In fact, most people have dozens (or even hundreds!) of mutations in their DNA. Secondly, from an evolutionary perspective, mutations are essential. They are needed for evolution to occur because they are the ultimate source of all new genetic variation in any species.

Causes of Mutations

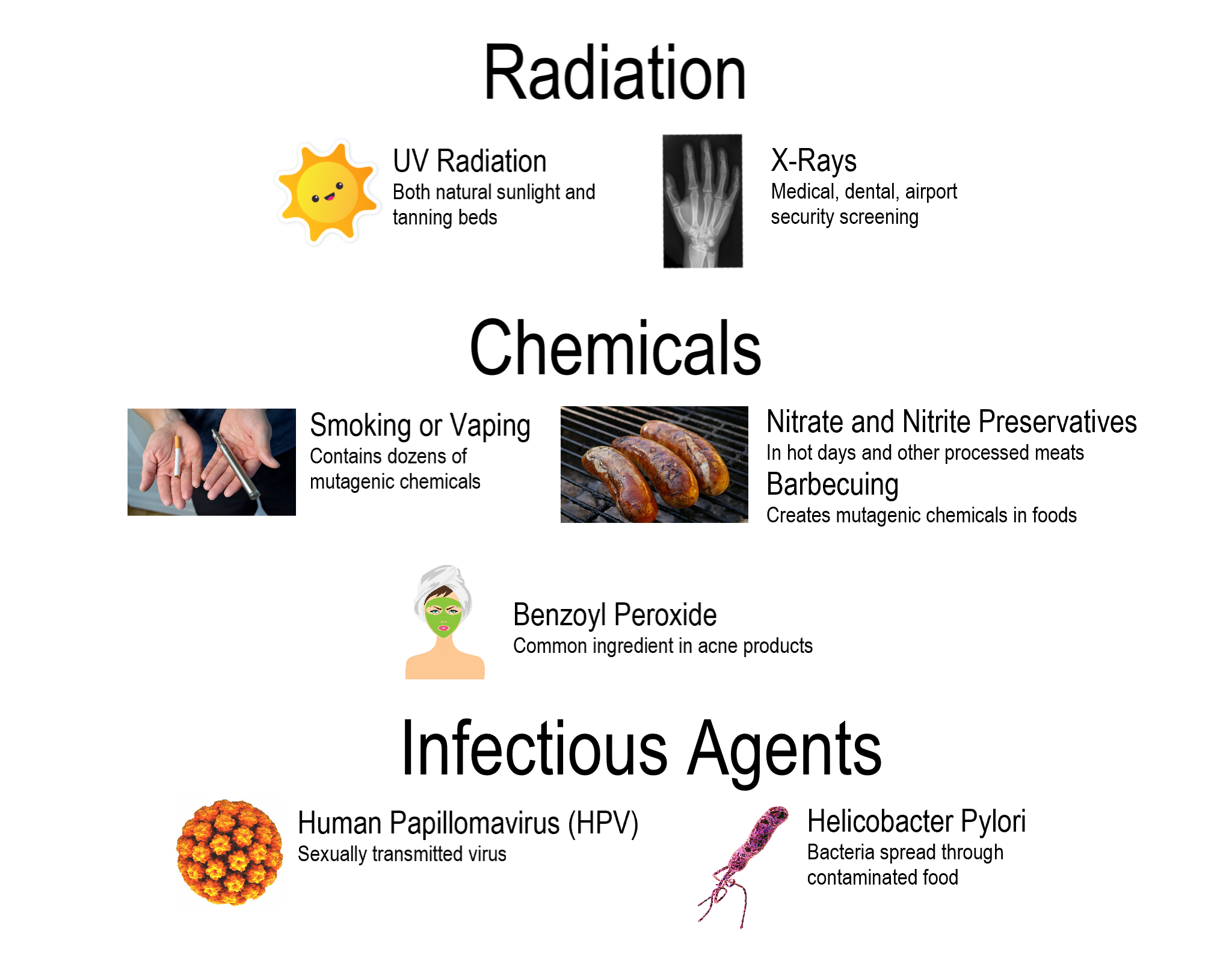

Mutations have many possible causes. Some mutations seem to happen spontaneously, without any outside influence. They occur when errors are made during DNA replication or during the transcription phase of protein synthesis. Other mutations are caused by environmental factors. Anything in the environment that can cause a mutation is known as a mutagen. Examples of mutagens are shown in the figure below.

Types of Mutations

Mutations come in a variety of types. Two major categories of mutations are germline mutations and somatic mutations.

- Germline mutations occur in gametes (the sex cells), such as eggs and sperm. These mutations are especially significant because they can be transmitted to offspring, causing every cell in the offspring to carry those mutations.

- Somatic mutations occur in other cells of the body. These mutations may have little effect on the organism, because they are confined to just one cell and its daughter cells. Somatic mutations cannot be passed on to offspring.

Mutations also differ in the way that the genetic material is changed. Mutations may change an entire chromosome, or they may alter just one or a few nucleotides.

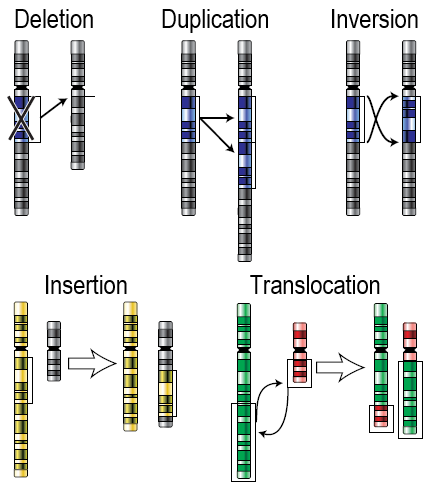

Chromosomal Alterations

Chromosomal alterations are mutations that change chromosome structure. They occur when a section of a chromosome breaks off and rejoins incorrectly, or otherwise does not rejoin at all. Possible ways in which these mutations can occur are illustrated in the figure below. Chromosomal alterations are very serious. They often result in the death of the organism in which they occur. If the organism survives, it may be affected in multiple ways. An example of a human disease caused by a chromosomal duplication is Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 (CMT1). It is characterized by muscle weakness, as well as loss of muscle tissue and sensation. The most common cause of CMT1 is a duplication of part of chromosome 17.

Point Mutations

A point mutation is a change in a single nucleotide in DNA. This type of mutation is usually less serious than a chromosomal alteration. An example of a point mutation is a mutation that changes the codon UUU to the codon UCU. Point mutations can be silent, missense, or nonsense mutations, as described in Table 5.8.1. The effects of point mutations depend on how they change the genetic code.

| Type | Description | Example | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silent | mutated codon codes for the same amino acid | CAA (glutamine) → CAG (glutamine) | none |

| Missense | mutated codon codes for a different amino acid | CAA (glutamine) → CCA (proline) | variable |

| Nonsense | mutated codon is a premature stop codon | CAA (glutamine) → UAA (stop) usually | serious |

Frameshift Mutations

A frameshift mutation is a deletion or insertion of one or more nucleotides, changing the reading frame of the base sequence. Deletions remove nucleotides, and insertions add nucleotides. Consider the following sequence of bases in RNA:

AUG-AAU-ACG-GCU = start-asparagine-threonine-alanine

Now, assume that an insertion occurs in this sequence. Let’s say an A nucleotide is inserted after the start codon AUG. The sequence of bases becomes:

AUG-AAA-UAC-GGC-U = start-lysine-tyrosine-glycine

Even though the rest of the sequence is unchanged, this insertion changes the reading frame and, therefore, all of the codons that follow it. As this example shows, a frameshift mutation can dramatically change how the codons in mRNA are read. This can have a drastic effect on the protein product.

Effects of Mutations

The majority of mutations have neither negative nor positive effects on the organism in which they occur. These mutations are called neutral mutations. Examples include silent point mutations, which are neutral because they do not change the amino acids in the proteins they encode.

Many other mutations have no effects on the organism because they are repaired before protein synthesis occurs. Cells have multiple repair mechanisms to fix mutations in DNA.

Beneficial Mutations

Some mutations — known as beneficial mutations — have a positive effect on the organism in which they occur. They generally code for new versions of proteins that help organisms adapt to their environment. If they increase an organism’s chances of surviving or reproducing, the mutations are likely to become more common over time. There are several well-known examples of beneficial mutations. Here are two such examples:

- Mutations have occurred in bacteria that allow the bacteria to survive in the presence of antibiotic drugs, leading to the evolution of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria.

- A unique mutation is found in people in Limone, a small town in Italy. The mutation protects them from developing atherosclerosis, which is the dangerous buildup of fatty materials in blood vessels despite a high-fat diet. The individual in which this mutation first appeared has even been identified and many of his descendants carry this gene.

Harmful Mutations

Imagine making a random change in a complicated machine, such as a car engine. There is a chance that the random change would result in a car that does not run well — or perhaps does not run at all. By the same token, a random change in a gene's DNA may result in the production of a protein that does not function normally... or may not function at all. Such mutations are likely to be harmful. Harmful mutations may cause genetic disorders or cancer.

- A genetic disorder is a disease, syndrome, or other abnormal condition caused by a mutation in one or more genes, or by a chromosomal alteration. An example of a genetic disorder is cystic fibrosis. A mutation in a single gene causes the body to produce thick, sticky mucus that clogs the lungs and blocks ducts in digestive organs.

- Cancer is a disease in which cells grow out of control and form abnormal masses of cells (called tumors). It is generally caused by mutations in genes that regulate the cell cycle. Because of the mutations, cells with damaged DNA are allowed to divide without restriction.

Feature: My Human Body

Inherited mutations are thought to play a role in roughly five to ten per cent of all cancers. Specific mutations that cause many of the known hereditary cancers have been identified. Most of the mutations occur in genes that control the growth of cells or the repair of damaged DNA.

Genetic testing can be done to determine whether individuals have inherited specific cancer-causing mutations. Some of the most common inherited cancers for which genetic testing is available include hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, caused by mutations in genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2. Besides breast and ovarian cancers, mutations in these genes may also cause pancreatic and prostate cancers. Genetic testing is generally done on a small sample of body fluid or tissue, such as blood, saliva, or skin cells. The sample is analyzed by a lab that specializes in genetic testing, and it usually takes at least a few weeks to get the test results.

Should you get genetic testing to find out whether you have inherited a cancer-causing mutation? Such testing is not done routinely just to screen patients for risk of cancer. Instead, the tests are generally done only when the following three criteria are met:

- The test can determine definitively whether a specific gene mutation is present. This is the case with the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations, for example.

- The test results would be useful to help guide future medical care. For example, if you found out you had a mutation in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, you might get more frequent breast and ovarian cancer screenings than are generally recommended.

- You have a personal or family history that suggests you are at risk of an inherited cancer.

Criterion number 3 is based, in turn, on such factors as:

- Diagnosis of cancer at an unusually young age.

- Several different cancers occurring independently in the same individual.

- Several close genetic relatives having the same type of cancer (such as a maternal grandmother, mother, and sister all having breast cancer).

- Cancer occurring in both organs in a set of paired organs (such as both kidneys or both breasts).

If you meet the criteria for genetic testing and are advised to undergo it, genetic counseling is highly recommended. A genetic counselor can help you understand what the results mean and how to make use of them to reduce your risk of developing cancer. For example, a positive test result that shows the presence of a mutation may not necessarily mean that you will develop cancer. It may depend on whether the gene is located on an autosome or sex chromosome, and whether the mutation is dominant or recessive. Lifestyle factors may also play a role in cancer risk even for hereditary cancers. Early detection can often be life saving if cancer does develop. Genetic counseling can also help you assess the chances that any children you may have will inherit the mutation.

5.8 Summary

- Mutations are random changes in the sequence of bases in DNA or RNA. Most people have multiple mutations in their DNA without ill effects. Mutations are the ultimate source of all new genetic variation in any species.

- Mutations may happen spontaneously during DNA replication or transcription. Other mutations are caused by environmental factors called mutagens. Mutagens include radiation, certain chemicals, and some infectious agents.

- Germline mutations occur in gametes and may be passed onto offspring. Every cell in the offspring will then have the mutation. Somatic mutations occur in cells other than gametes and are confined to just one cell and its daughter cells. These mutations cannot be passed on to offspring.

- Chromosomal alterations are mutations that change chromosome structure and usually affect the organism in multiple ways. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 is an example of a chromosomal alteration in humans.

- Point mutations are changes in a single nucleotide. The effects of point mutations depend on how they change the genetic code and may range from no effects to very serious effects.

- Frameshift mutations change the reading frame of the genetic code and are likely to have a drastic effect on the encoded protein.

- Many mutations are neutral and have no effect on the organism in which they occur. Some mutations are beneficial and improve fitness. An example is a mutation that confers antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Other mutations are harmful and decrease fitness, such as the mutations that cause genetic disorders or cancers.

5.8 Review Question

- Define mutation.

- Identify causes of mutation.

- Compare and contrast germline and somatic mutations.

- Describe chromosomal alterations, point mutations, and frameshift mutations. Identify the potential effects of each type of mutation.

- Why do many mutations have neutral effects?

- Give one example of a beneficial mutation and one example of a harmful mutation.

-

- Why do you think that exposure to mutagens (such as cigarette smoke) can cause cancer?

- Explain why the insertion or deletion of a single nucleotide can cause a frameshift mutation.

- Compare and contrast missense and nonsense mutations.

- Explain why mutations are important to evolution.

5.8 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=51&v=PQjL4ZDuq2o&feature=emb_logo

How Radiation Changes Your DNA, Seeker, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9HIYjRRaDE&t=93s

Where do genes come from? - Carl Zimmer, TED-Ed, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a63t8r70QN0&feature=youtu.be

What you should know about vaping and e-cigarettes | Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin,

TED, 2019.

Attributions

Figure 5.8.1

Ninja Turtles by Pat Loika on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 5.8.2

Separate images are all in public domain or CC licensed:

- Beauty treatment face mask by no-longer-here on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

- HPV by AJC1 on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

- H Pylori by AJC1 on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

- Vape and Cigarette by Vaping360 on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

- Hand X-Ray by Hellerhoff on Wikimedia Commons - CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

- Hot dogs by unknown on PxFuel is used under the Pxfuel Terms (https://www.pxfuel.com/terms-of-use).

- Sunshine face is clipart.

Figure 5.8.3

Scheme of possible chromosome mutations/ Chromosomenmutationen by unknown on Wikimedia Commons is adapted from NIH's Talking Glossary of Genetics. [Changes as described by de:user:Dietzel65]. Further use and adapation (text translated to English) by Christine Miller as image is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Seeker. (2016, April 23). How radiation changes your DNA. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PQjL4ZDuq2o&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2019, June 5). What you should know about vaping and e-cigarettes | Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a63t8r70QN0&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2014, September 22). Where do genes come from? - Carl Zimmer. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9HIYjRRaDE&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 6). Breast cancer. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Breast_cancer&oldid=966366739

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 9). Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charcot%E2%80%93Marie%E2%80%93Tooth_disease&oldid=966912915

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 7). Cystic fibrosis. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cystic_fibrosis&oldid=966566921

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 4). Limone sul Garda. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Limone_sul_Garda&oldid=960771991

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 23). Ovarian cancer. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ovarian_cancer&oldid=964157192

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 7). BRCA mutation. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BRCA_mutation&oldid=955463902

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 10). Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Teenage_Mutant_Ninja_Turtles&oldid=967030468

Body cavity that fills the lower half of the trunk and holds the kidneys and the digestive and reproductive organs.

A major human body cavity that includes the head and the posterior (back) of the trunk and holds the brain and spinal cord.

A cavity that fills most of the upper part of the skull and contains the brain.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Like Father, Like Son

This father-son duo share some similarities. The shape of their faces and their facial features look very similar. If you saw them together, you might well guess that they are father and son. People have long known that the characteristics of living things are similar between parents and their offspring. However, it wasn’t until the experiments of Gregor Mendel that scientists understood how those traits are inherited.

The Father of Genetics

Mendel did experiments with pea plants to show how traits such as seed shape and flower colour are inherited. Based on his research, he developed his two well known laws of inheritance: the law of segregation and the law of independent assortment. When Mendel died in 1884, his work was still virtually unknown. In 1900, three other researchers working independently came to the same conclusions that Mendel had drawn almost half a century earlier. Only then was Mendel's work rediscovered.

Mendel knew nothing about genes, because they were discovered after his death. He did think, however, that some type of "factors" controlled traits, and that those "factors" were passed from parents to offspring. We now call these "factors" genes. Mendel's laws of inheritance, now expressed in terms of genes, form the basis of genetics, the science of heredity. For this reason, Mendel is often called the father of genetics.

The Language of Genetics

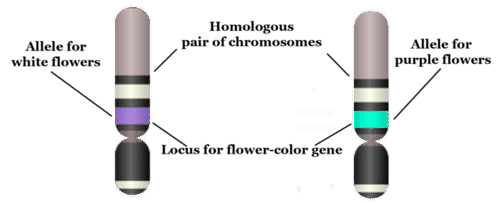

Today, we know that traits of organisms are controlled by genes on chromosomes. To talk about inheritance in terms of genes and chromosomes, you need to know the language of genetics. The terms below serve as a good starting point. They are illustrated in the figure that follows.

- A gene is the part of a chromosome that contains the genetic code for a given protein. For example, in pea plants, a given gene might code for flower colour.

- The position of a given gene on a chromosome is called its locus (plural, loci). A gene might be located near the center, or at one end or the other of a chromosome.

- A given gene may have different normal versions, which are called alleles. For example, in pea plants, there is a purple-flower allele (B) and a white-flower allele (b) for the flower-colour gene. Different alleles account for much of the variation in the traits of organisms, including people.

- In sexually reproducing organisms, each individual has two copies of each type of chromosome. Paired chromosomes of the same type are called homologous chromosomes. They are about the same size and shape, and they have all the same genes at the same loci.

Genotype

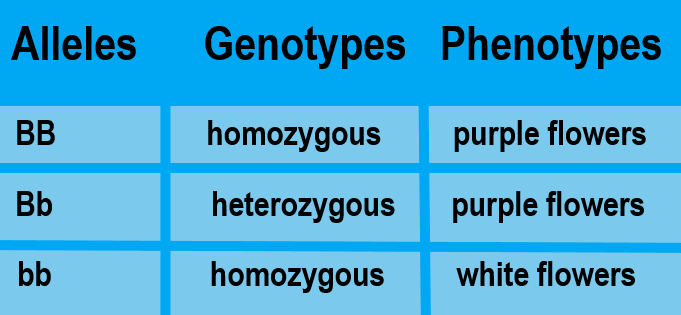

When sexual reproduction occurs, sex cells (called gametes) unite during fertilization to form a single cell called a zygote. The zygote inherits two of each type of chromosome, with one chromosome of each type coming from the father, and the other coming from the mother. Because homologous chromosomes have the same genes at the same loci, each individual also inherits two copies of each gene. The two copies may be the same allele or different alleles. The alleles an individual inherits for a given gene make up the individual’s genotype. As shown in Table 5.11.1, an organism with two of the same allele (for example, BB or bb) is called a homozygote. An organism with two different alleles (in this example, Bb) is called a heterozygote.

Table 5.11.1

Allele Combinations Associated With the Terms Homozygous and Heterozygous

Phenotype

The expression of an organism’s genotype is referred to as its phenotype, and it refers to the organism’s traits, such as purple or white flowers in pea plants. As you can see from Table 5.11.1, different genotypes may produce the same phenotype. In this example, both BB and Bb genotypes produce plants with the same phenotype, purple flowers. Why does this happen? In a Bb heterozygote, only the B allele is expressed, so the b allele doesn’t influence the phenotype. In general, when only one of two alleles is expressed in the phenotype, the expressed allele is called dominant, and the allele that isn’t expressed is called recessive.

The terms dominant and recessive may also be used to refer to phenotypic traits. For example, purple flower colour in pea plants is a dominant trait. It shows up in the phenotype whenever a plant inherits even one dominant allele for the trait. Similarly, white flower colour is a recessive trait. Like other recessive traits, it shows up in the phenotype only when a plant inherits two recessive alleles for the trait.

5.11 Summary

- Mendel's laws of inheritance, now expressed in terms of genes, form the basis of genetics, which is the science of heredity. This is why Mendel is often called the father of genetics.

- A gene is the part of a chromosome that codes for a given protein. The position of a gene on a chromosome is its locus. A given gene may have different versions, called alleles. Paired chromosomes of the same type are called homologous chromosomes. They have the same size and shape, and they have the same genes at the same loci.

- The alleles an individual inherits for a given gene make up the individual's genotype. An organism with two of the same allele is called a homozygote, and an individual with two different alleles is called a heterozygote.

- The expression of an organism's genotype is referred to as its phenotype. A dominant allele is always expressed in the phenotype, even when just one dominant allele has been inherited. A recessive allele is expressed in the phenotype only when two recessive alleles have been inherited.

5.11 Review Questions

- Define genetics.

- Why is Gregor Mendel called the father of genetics if genes were not discovered until after his death?

-

- Imagine that there are two alleles, R and r, for a given gene. R is dominant to r. Answer the following questions about this gene:

- What are the possible homozygous and heterozygous genotypes?

- Which genotype or genotypes express the dominant R phenotype? Explain your answer.

- Are R and r on different loci? Why or why not?

- Can R and r be on the same exact chromosome? Why or why not? If not, where are they located?

5.11 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pv3Kj0UjiLE

Alleles and Genes, Amoeba Sisters, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OaovnS7BAoc

Genotypes and Phenotypes, Bozeman Science, 2011.

Attributions

Figure 5.11.1

Father holding his baby boy with matching haircut [photo] by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 5.11.2

Chromosome, Gene, Locus, and Allele by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under ![]() • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

Table 5.11.1

Allele Combinations Associated With the Terms Homozygous and Heterozygous by Christine Miller is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2018, February 1). Alleles and genes. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pv3Kj0UjiLE&feature=youtu.be

Bozeman Science. (2011, August 4). Genotypes and phenotypes. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OaovnS7BAoc&feature=youtu.be

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2016). Figure 2 Chromosome, gene, locus, and allele [digital image]. In CK-12 College Human Biology (Section 5.10) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-human-biology/section/5.9/

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

All in the Family

This family photo (Figure 5.12.1) clearly illustrates an important point: children in a family resemble their parents and each other, but the children never look exactly the same, unless they are identical twins. Each of the daughters in the photo have inherited a unique combination of traits from the parents. In this concept, you will learn how this happens. It all begins with sex — sexual reproduction, that is.

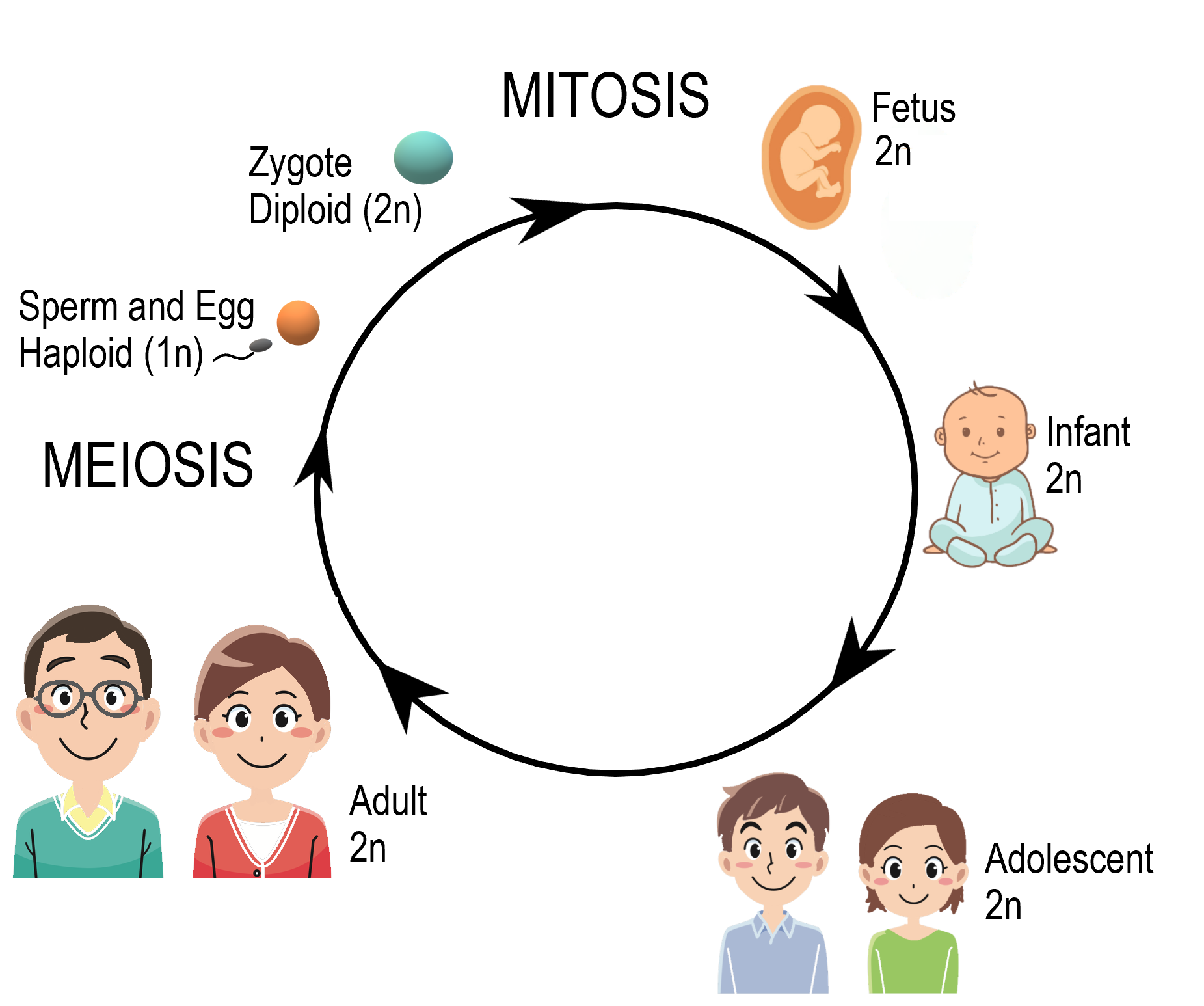

Sexual Reproduction

Reproduction is the process by which organisms give rise to offspring. It is one of the defining characteristics of living things. Like many other organisms, human beings reproduce sexually. Sexual reproduction involves two parents. As you can see from Figure 5.12.2, in sexual reproduction, parents produce reproductive (sex) cells — called gametes — that unite to form an offspring. Gametes are haploid (or 1N) cells. This means they contain one copy of each chromosome in the nucleus. Gametes are produced by a type of cell division called meiosis, which is described in detail below. The process in which two gametes unite is called fertilization. The fertilized cell that results is referred to as a zygote. A zygote is a diploid (or 2N) cell, which means it contains two copies of each chromosome. Thus, it has twice the number of chromosomes as a gamete.

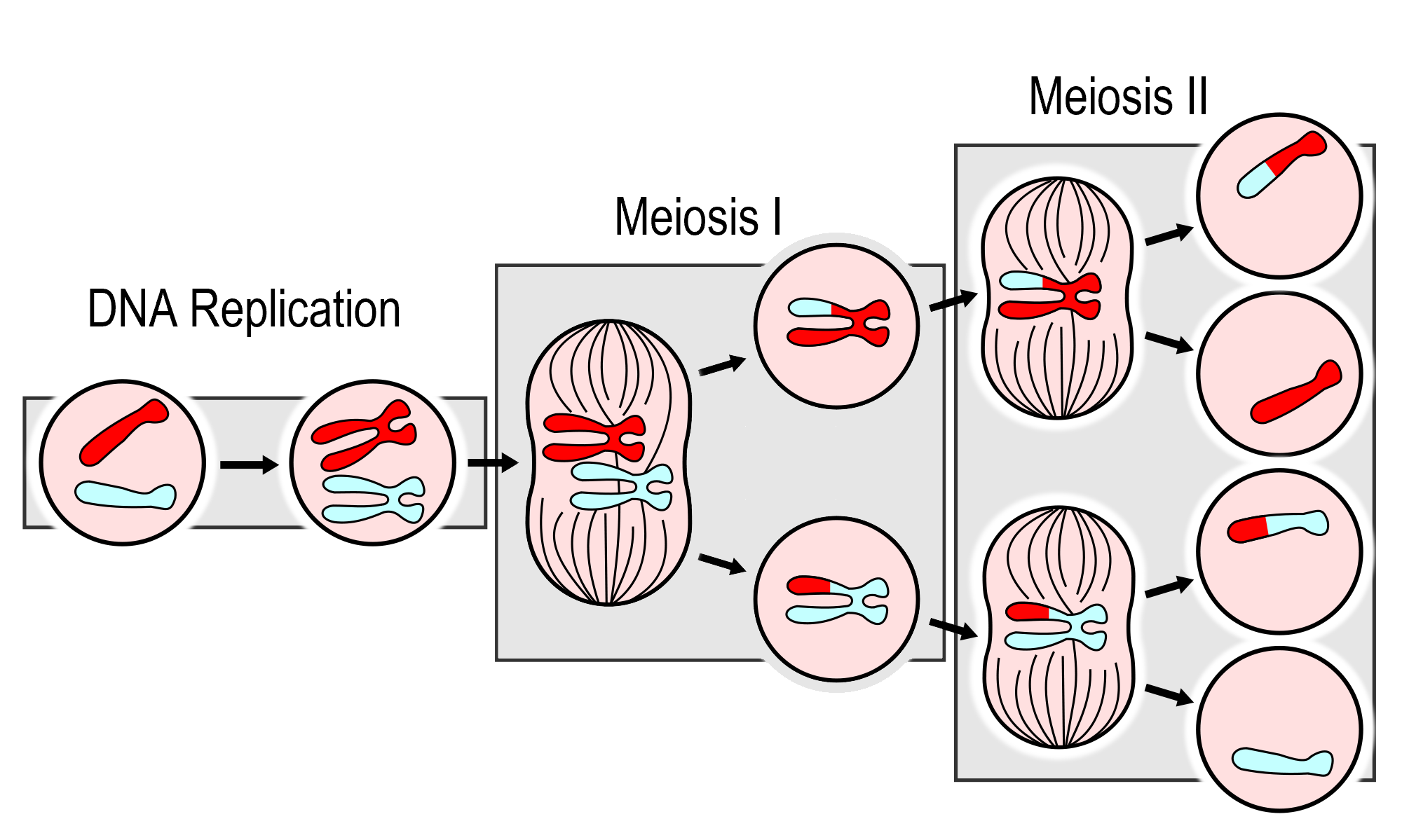

Meiosis

The process that produces haploid gametes is called meiosis. Meiosis is a type of cell division in which the number of chromosomes is reduced by half. It occurs only in certain special cells of an organism. During meiosis, homologous (paired) chromosomes separate, and four haploid cells form that have only one chromosome from each pair. The diagram (Figure 5.12.3) gives an overview of meiosis.

As you can see in the meiosis diagram, two cell divisions occur during the overall process, producing a total of four haploid cells from one parent cell. The two cell divisions are called meiosis I and meiosis II. Meiosis I begins after DNA replicates during interphase. Meiosis II follows meiosis I without DNA replicating again. Both meiosis I and meiosis II occur in four phases, called prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. You may recognize these four phases from mitosis, the division of the nucleus that takes place during routine cell division of eukaryotic cells.

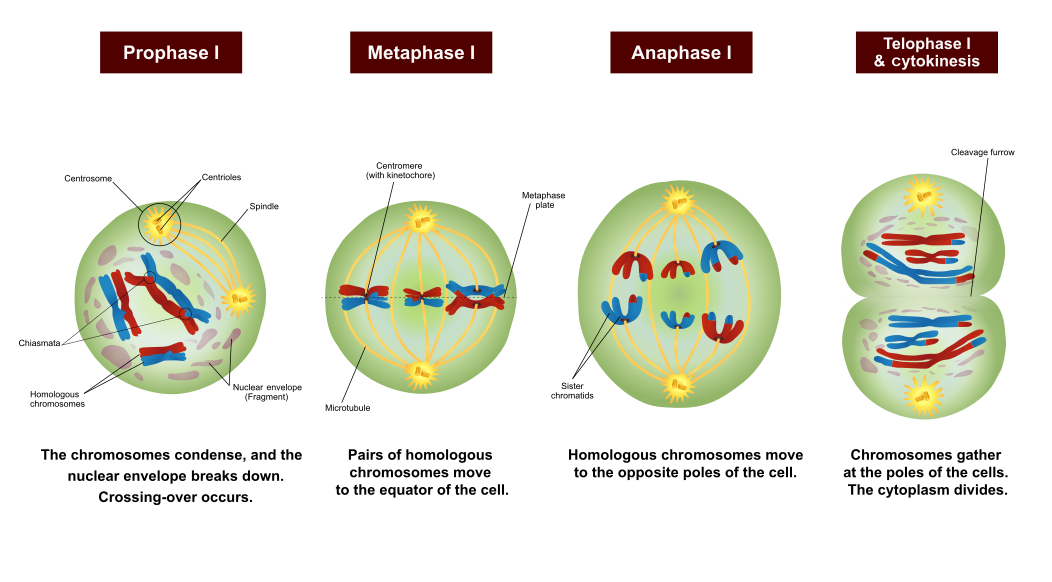

Meiosis I- Increasing genetic variation

The phases of Meiosis I are:

- Prophase I: The nuclear envelope begins to break down, and the chromosomes condense. Centrioles start moving to opposite poles of the cell, and a spindle begins to form. Importantly, homologous chromosomes pair up, which is unique to prophase I. In prophase of mitosis and meiosis II, homologous chromosomes do not form pairs in this way. During prophase I, crossing-over occurs. The significance of crossing-over is discussed below.

- Metaphase I: Spindle fibres attach to the paired homologous chromosomes. The paired chromosomes line up along the equator of the cell, randomly aligning in a process called independent alignment. The significance of independent alignment is discussed below. This occurs only in metaphase I. In metaphase of mitosis and meiosis II, it is sister chromatids that line up along the equator of the cell.

- Anaphase I: Spindle fibres shorten, and the chromosomes of each homologous pair start to separate from each other. One chromosome of each pair moves toward one pole of the cell, and the other chromosome moves toward the opposite pole.

- Telophase I and Cytokinesis: The spindle breaks down, and new nuclear membranes form. The cytoplasm of the cell divides, and two haploid daughter cells result. The daughter cells each have a random assortment of chromosomes, with one from each homologous pair. Both daughter cells go on to meiosis II.

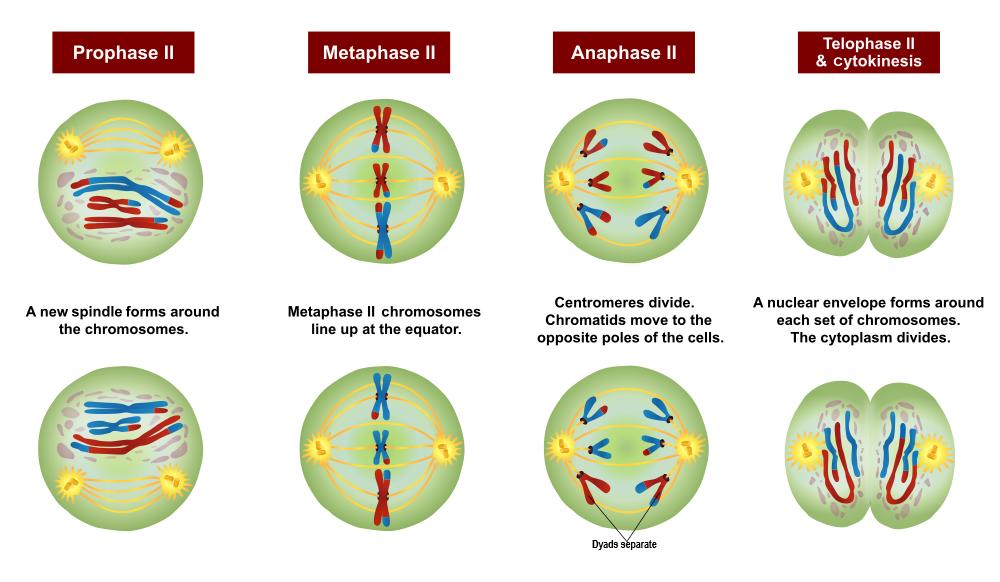

Meiosis II- Halfing the DNA

The phases of Meiosis II are:

- Prophase II: The nuclear envelope breaks down, and the spindle begins to form in each haploid daughter cell from meiosis I. The centrioles also start to separate.

- Metaphase II: Spindle fibres line up the sister chromatids of each chromosome along the equator of the cell.

- Anaphase II: Sister chromatids separate and move to opposite poles.

- Telophase II and Cytokinesis: The spindle breaks down, and new nuclear membranes form. The cytoplasm of each cell divides, and four haploid cells result. Each cell has a unique combination of chromosomes.

Sexual Reproduction and Genetic Variation

"It takes two to tango" might be a euphemism for sexual reproduction. Requiring two individuals to produce offspring, however, is also the main drawback of this way of reproducing, because it requires extra steps — and often a certain amount of luck — to successfully reproduce with a partner. On the other hand, sexual reproduction greatly increases the potential for genetic variation in offspring, which increases the likelihood that the resulting offspring will have genetic advantages. In fact, each offspring produced is almost guaranteed to be genetically unique, differing from both parents and from any other offspring. Sexual reproduction increases genetic variation in a number of ways:

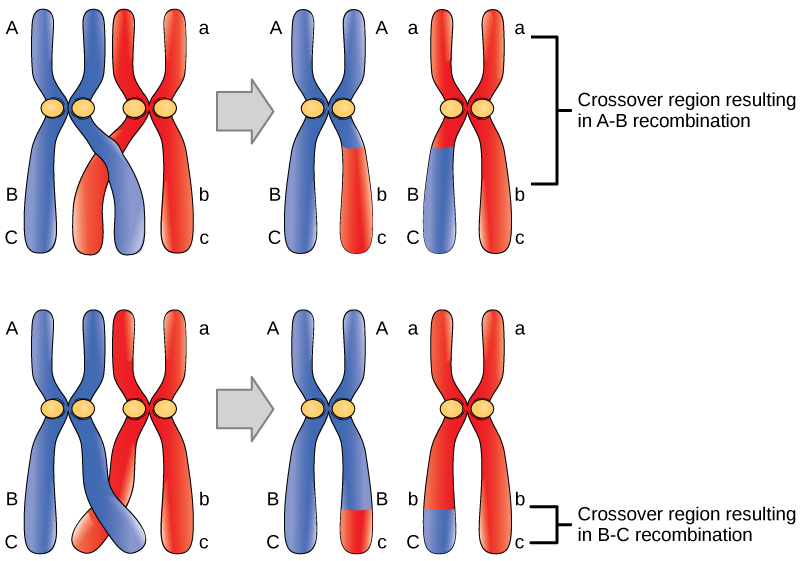

- When homologous chromosomes pair up during meiosis I, crossing-over can occur. Crossing-over is the exchange of genetic material between non-sister chromatids of homologous chromosomes. It results in new combinations of genes on each chromosome. This is called recombination. You can see how it happens in the figure to the right.

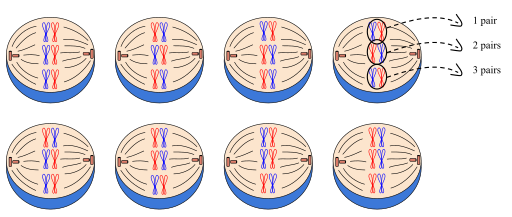

- When cells divide during meiosis, homologous chromosomes are randomly distributed to daughter cells, and different chromosomes segregate independently of each other. This is called independent alignment. It results in gametes that have unique combinations of chromosomes. You can see how it happens in Figure 5.12.7.

- In sexual reproduction, two gametes unite to produce an offspring. But which two of the millions of possible gametes will it be? This is a matter of chance, and it's obviously another source of genetic variation in offspring.

With all of this recombination of genes, there is a need for a new set of vocabulary. Remember, that sister chromatids are two identical pieces of DNA connected at a centromere. Once crossing over has occured, we can no longer call them sister chromatids since they are no longer identical; we term them dyads. In addition, once crossing over has occurred, the pair of homologous chromosomes can be referred to as tetrads.

All of these mechanisms — crossing over, independent assortment, and the random union of gametes — work together to result in an amazing range of potential genetic variation. Each human couple, for example, has the potential to produce more than 64 trillion genetically unique children. No wonder we are all different!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzDMG7ke69g

Meiosis (updated), Amoeba Sisters, 2017.

Gametogenesis

At the end of meiosis, four haploid cells have been produced, but the cells are not yet gametes. The cells need to develop before they become mature gametes capable of fertilization. The development of haploid cells into gametes is called gametogenesis. It differs between males and females.

- A gamete produced by a male is called a sperm, and the process that produces a mature sperm is called spermatogenesis. During this process, a sperm cell grows a tail and gains the ability to “swim,” like the human sperm cell shown in Figure 5.12.8.

- A gamete produced by a female is called anegg or ovum, and the process that produces a mature egg is called oogenesis, during which just one functional egg is produced. The other three haploid cells that result from meiosis are called polar bodies, and they disintegrate. The single egg is a very large cell, as you can see from the human egg also shown in Figure 5.12.8.

5.12 Summary

- In sexual reproduction, two parents produce gametes that unite in the process of fertilization to form a single-celled zygote. Gametes are haploid cells with one copy of each of the 23 chromosomes, and the zygote is a diploid cell with two copies of each of the 23 chromosomes.

- Meiosis is the type of cell division that produces four haploid daughter cells that may become gametes. Meiosis occurs in two stages, called meiosis I and meiosis II, each of which occurs in four phases (prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase).

- Meiosis is followed by gametogenesis, the process during which the haploid daughter cells change into mature gametes. Males produce gametes called sperm in a process known as spermatogenesis, and females produce gametes called eggs in the process known as oogenesis.

- Sexual reproduction produces genetically unique offspring. Crossing-over, independent alignment, and the random union of gametes work together to result in an amazing range of potential genetic variation.

5.12 Review Questions

-

- Explain how sexual reproduction happens at the cellular level.

- Summarize what happens during Meiosis.

- Compare and contrast gametogenesis in males and females.

- Explain the mechanisms that increase genetic variation in the offspring produced by sexual reproduction.

- Why do gametes need to be haploid? What would happen to the chromosome number after fertilization if they were diploid?

- Describe one difference between Prophase I of Meiosis and Prophase of Mitosis.

- Do all of the chromosomes that you got from your mother go into one of your gametes? Why or why not?

5.12 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCLmR9-YY7o&feature=emb_logo

Meiosis: Where the Sex Starts - Crash Course Biology #13, CrashCourse, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrKdz93WlVk

Mitosis vs Meiosis Comparison, Amoeba Sisters, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 5.12.1

Family portrait by loly galina on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 5.12.2

Human Life Cycle by Christine Miller is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) license.

Figure 5.12.3

MajorEventsInMeiosis_variant_int by PatríciaR (internationalization) on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller. This image in the public domain. (Original image from NCBI; original vector version by Jakov.)

Figure 5.12.4

Meiosis 1/ Meiosis Stages by Ali Zifan on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 5.12.5

Meiosis 2/ Meiosis Stages by Ali Zifan on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 5.12.6

Crossover/ Figure 17 02 01 by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 5.12.7

Independent_assortment by Mtian20 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 5.12.8

sperm fertilizing egg by AndreaLaurel on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2017, July 11). Meiosis (updated). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzDMG7ke69g&feature=youtu.be

Amoeba Sisters. (2018, May 31). Mitosis vs meiosis comparison. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zrKdz93WlVk&feature=youtu.be

CrashCourse, (2012, April 23). Meiosis: Where the sex starts - Crash Course Biology #13. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCLmR9-YY7o&feature=youtu.be

OpenStax CNX. (2016, May 27). Figure 1 Crossover may occur at different locations on the chromosome. In OpenStax, Biology (Section 17.2). http://cnx.org/contents/185cbf87-c72e-48f5-b51e-f14f21b5eabd@10.53.

Clear fluid produced by the brain that forms a thin layer within the meninges and provides protection and cushioning for the brain and spinal cord.