6.5 Variation in Blood Types

Giving the Gift of Life

Did you ever donate blood? If you did, then you probably know that your blood type is an important factor in blood transfusions. People vary in the type of blood they inherit, and this determines which type(s) of blood they can safely receive in a transfusion. Do you know your blood type?

What Are Blood Types?

Blood is composed of cells suspended in a liquid called plasma. There are three types of cells in blood: red blood cells, which carry oxygen; white blood cells, which fight infections and other threats; and platelets, which are cell fragments that help blood clot. Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of certain molecules, called antigens, on the surface of red blood cells. These molecules may help maintain the integrity of the cell membrane, act as receptors, or have other biological functions. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens. Human blood group systems include the well-known ABO and Rhesus (Rh) systems, as well as at least 33 others that are less well known.

Antigens and Antibodies

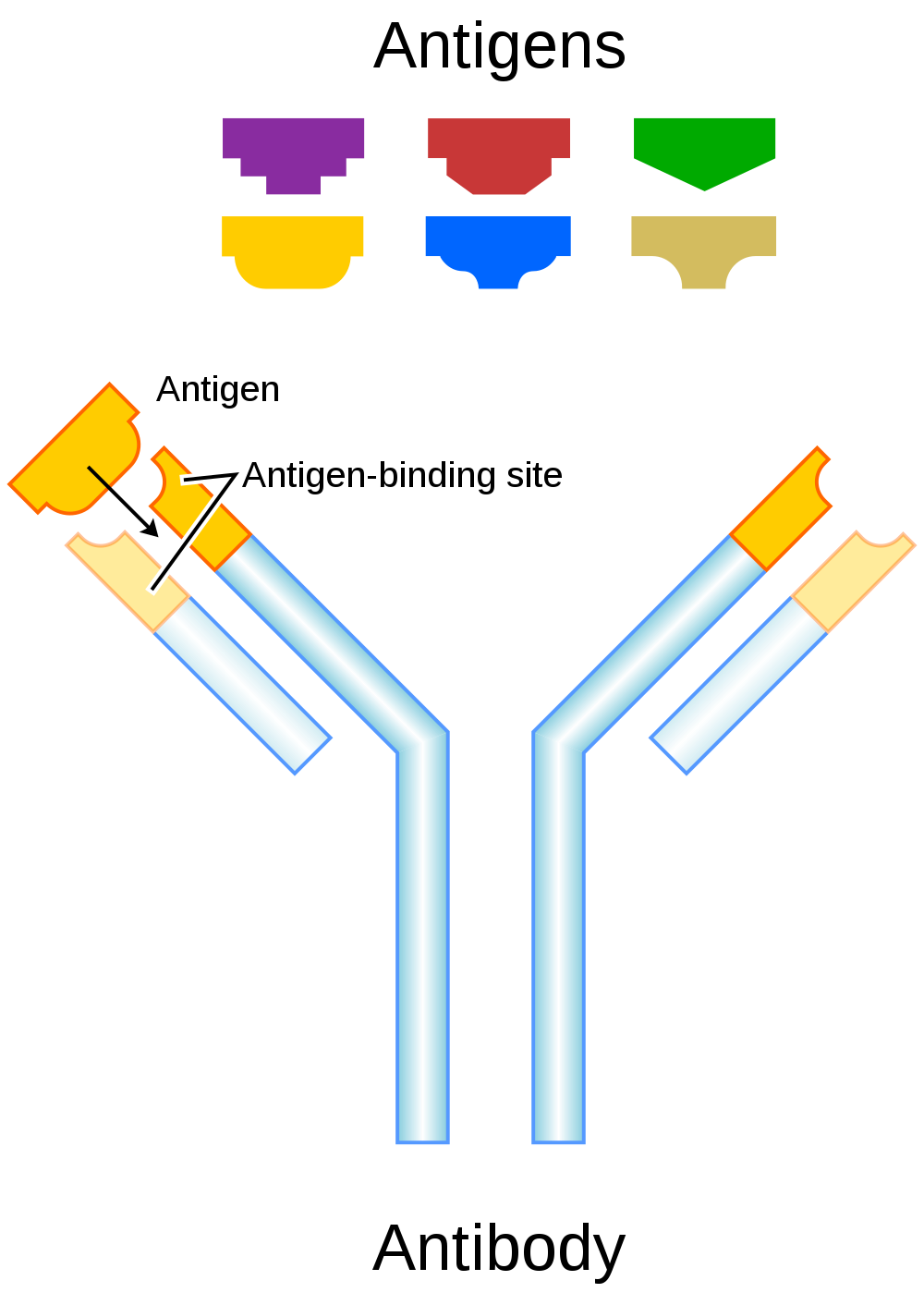

Antigens — such as those on the red blood cells — are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self (produced by your own body) or non-self (not produced by your own body). Blood group antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins (proteins attached to chains of sugars), or glycolipids (lipids attached to chains of sugars), depending on the particular blood group system. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens. Antibodies are large, Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system that recognize and bind to non-self antigens. The analogy of a lock and key is often used to represent how an antibody and antigen fit together, as shown in the illustration below (Figure 6.5.2). When antibodies bind to antigens, it marks them for destruction by other immune system cells. Non-self antigens may enter your body on pathogens (such as bacteria or viruses), on foods, or on red blood cells in a blood transfusion from someone with a different blood type than your own. The last way is virtually impossible nowadays because of effective blood typing and screening protocols.

Genetics of Blood Type

An individual’s blood type depends on which alleles for a blood group system were inherited from their parents. Generally, blood type is controlled by alleles for a single gene, or for two or more very closely linked genes. Closely linked genes are almost always inherited together, because there is little or no recombination between them. Like other genetic traits, a person’s blood type is generally fixed for life, but there are rare instances in which blood type can change. This could happen, for example, if an individual receives a bone marrow transplant to treat a disease, such as leukemia. If the bone marrow comes from a donor who has a different blood type, the patient’s blood type may eventually convert to the donor’s blood type, because red blood cells are produced in bone marrow.

ABO Blood Group System

The ABO blood group system is the best known human blood group system. Antigens in this system are glycoproteins. These antigens are shown in the list below. There are four common blood types for the ABO system:

- Type A, in which only the A antigen is present.

- Type B, in which only the B antigen is present.

- Type AB, in which both the A and B antigens are present.

- Type O, in which neither the A nor the B antigen is present.

Genetics of the ABO System

The ABO blood group system is controlled by a single gene on chromosome 9. There are three common alleles for the gene, often represented by the letters A , B , and O. With three alleles, there are six possible genotypes for ABO blood group. Alleles A and B, however, are both dominant to allele O and codominant to each other. This results in just four possible phenotypes (blood types) for the ABO system. These genotypes and phenotypes are shown in Table 6.5.1.

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes

| ABO Blood Group System | |

| Genotype | Phenotype (Blood Type, or Group) |

| AA | A |

| AO | A |

| BB | B |

| BO | B |

| OO | O |

| AB | AB |

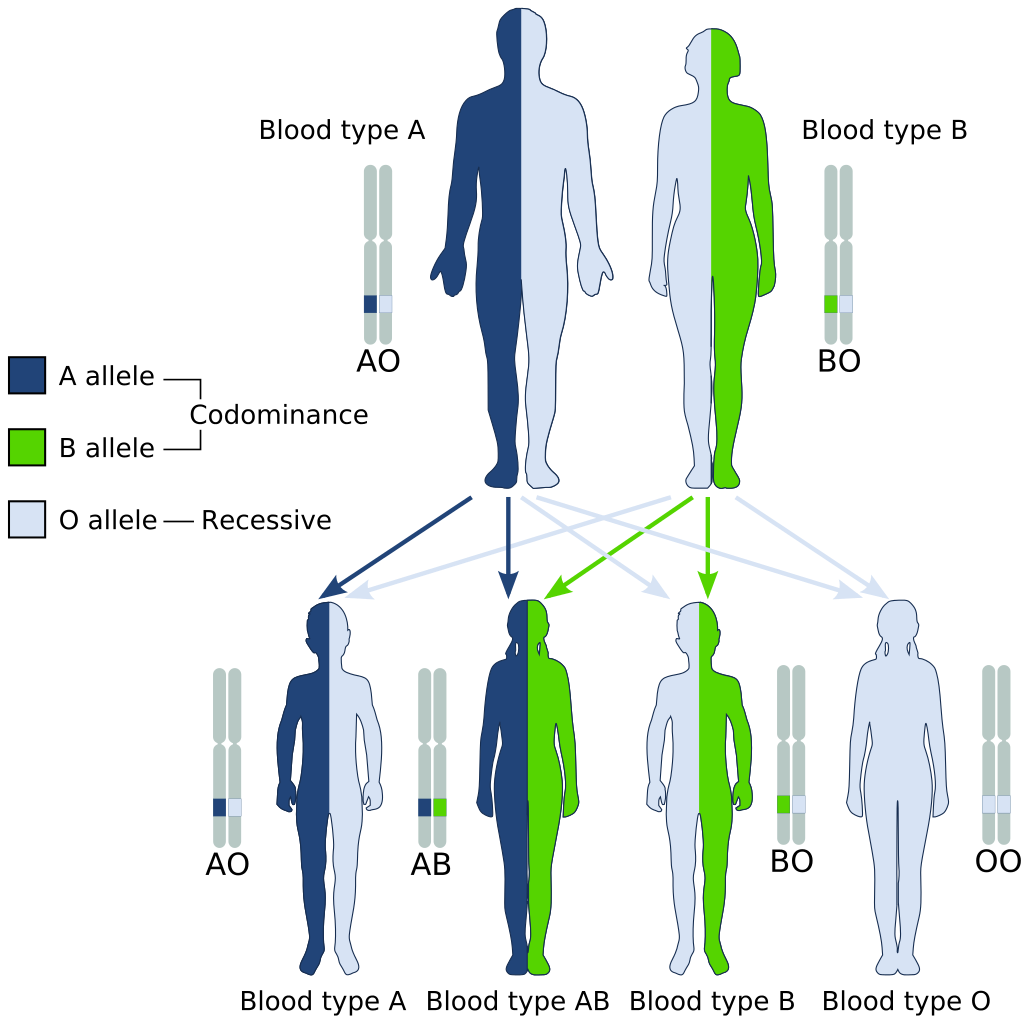

The diagram below (Figure 6.5.3) shows an example of how ABO blood type is inherited. In this particular example, the father has blood type A (genotype AO) and the mother has blood type B (genotype BO). This mating type can produce children with each of the four possible ABO phenotypes, although in any given family, not all phenotypes may be present in the children.

Medical Significance of ABO Blood Type

The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. If red blood cells containing a particular ABO antigen are transfused into a person who lacks that antigen, the person’s immune system will recognize the antigen on the red blood cells as non-self. Antibodies specific to that antigen will attack the red blood cells, causing them to agglutinate (or clump) and break apart. If a unit of incompatible blood were to be accidentally transfused into a patient, a severe reaction (called acute hemolytic transfusion reaction) is likely to occur, in which many red blood cells are destroyed. This may result in kidney failure, shock, and even death. Fortunately, such medical accidents virtually never occur today.

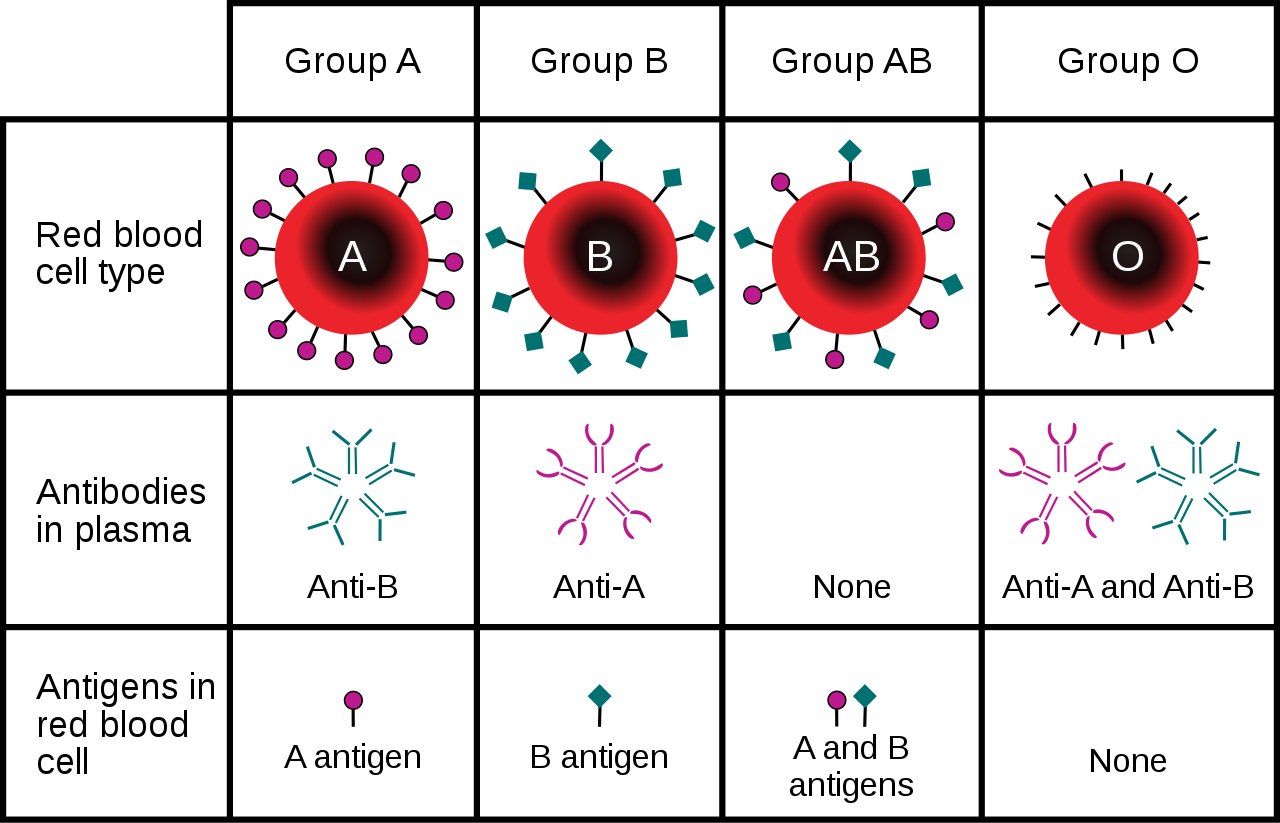

These antibodies are often spontaneously produced in the first years of life, after exposure to common microorganisms in the environment that have antigens similar to blood antigens. Specifically, a person with type A blood will produce anti-B antibodies, while a person with type B blood will produce anti-A antibodies. A person with type AB blood does not produce either antibody, while a person with type O blood produces both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Once the antibodies have been produced, they circulate in the plasma. The relationship between ABO red blood cell antigens and plasma antibodies is shown in Figure 6.5.4.

The antibodies that circulate in the plasma are for different antigens than those on red blood cells, which are recognized as self antigens.

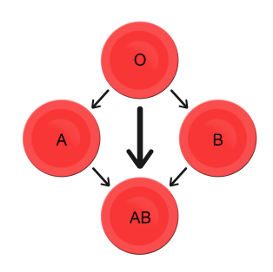

Which blood types are compatible and which are not? Type O blood contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, so people with type O blood can only receive type O blood. However, they can donate blood to people of any ABO blood type, which is why individuals with type O blood are called universal donors. Type AB blood contains neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies, so people with type AB blood can receive blood from people of any ABO blood type. That’s why individuals with type AB blood are called universal recipients. They can donate blood, however, only to people who also have type AB blood. These and other relationships between blood types of donors and recipients are summarized in the simple diagram to the right.

Geographic Distribution of ABO Blood Groups

The frequencies of blood groups for the ABO system vary around the world. You can see how the A and B alleles and the blood group O are distributed geographically on the maps in Figure 6.5.6.

- Worldwide, B is the rarest ABO allele, so type B blood is the least common ABO blood type. Only about 16 per cent of all people have the B allele. Its highest frequency is in Asia. Its lowest frequency is among the indigenous people of Australia and the Americas.

- The A allele is somewhat more common around the world than the B allele, so type A blood is also more common than type B blood. The highest frequencies of the A allele are in Australian Aborigines, the Lapps (Sami) of Northern Scandinavia, and Blackfoot Native Americans in North America. The allele is nearly absent among Native Americans in Central and South America.

- The O allele is the most common ABO allele around the world, and type O blood is the most common ABO blood type. Almost two-thirds of people have at least one copy of the O allele. It is especially common in Native Americans in Central and South America, where it reaches frequencies close to 100 per cent. It also has relatively high frequencies in Australian Aborigines and Western Europeans. Its frequencies are lowest in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Figure 6.5.6 Maps of populations that have the A, B and O alleles.

Evolution of the ABO Blood Group System

The geographic distribution of ABO blood type alleles provides indirect evidence for the evolutionary history of these alleles. Evolutionary biologists hypothesize that the allele for blood type A evolved first, followed by the allele for blood type O, and then by the allele for blood type B. This chronology accounts for the percentages of people worldwide with each blood group, and is also consistent with known patterns of early population movements.

The evolutionary forces of founder effect and genetic drift have no doubt played a significant role in the current distribution of ABO blood types worldwide. Geographic variation in ABO blood groups is also likely to be influenced by natural selection, because different blood types are thought to vary in their susceptibility to certain diseases. For example:

- People with type O blood may be more susceptible to cholera and plague. They are also more likely to develop gastrointestinal ulcers.

- People with type A blood may be more susceptible to smallpox and more likely to develop certain cancers.

- People with types A, B, and AB blood appear to be less likely to form blood clots that can cause strokes. However, early in our history, the ability of blood to form clots — which appears greater in people with type O blood — may have been a survival advantage.

- Perhaps the greatest natural selective force associated with ABO blood types is malaria. There is considerable evidence to suggest that people with type O blood are somewhat resistant to malaria, giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

Rhesus Blood Group System

Another well-known blood group system is the Rhesus (Rh) blood group system. The Rhesus system has dozens of different antigens, but only five main antigens (called D, C, c, E, and e). The major Rhesus antigen is the D antigen. People with the D antigen are called Rh positive (Rh+), and people who lack the D antigen are called Rh negative (Rh-). Rhesus antigens are thought to play a role in transporting ions across cell membranes by acting as channel proteins.

The Rhesus blood group system is controlled by two linked genes on chromosome 1. One gene, called RHD, produces a single antigen, antigen D. The other gene, called RHCE, produces the other four relatively common Rhesus antigens (C, c, E, and e), depending on which alleles for this gene are inherited.

Rhesus Blood Group and Transfusions

After the ABO system, the Rhesus system is the second most important blood group system in blood transfusions. The D antigen is the one most likely to provoke an immune response in people who lack the antigen. People who have the D antigen (Rh+) can be safely transfused with either Rh+ or Rh- blood, whereas people who lack the D antigen (Rh-) can be safely transfused only with Rh- blood.

Unlike anti-A and anti-B antibodies to ABO antigens, anti-D antibodies for the Rhesus system are not usually produced by sensitization to environmental substances. People who lack the D antigen (Rh-), however, may produce anti-D antibodies if exposed to Rh+ blood. This may happen accidentally in a blood transfusion, although this is extremely unlikely today. It may also happen during pregnancy with an Rh+ fetus if some of the fetal blood cells pass into the mother’s blood circulation.

Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

If a woman who is Rh- is carrying an Rh+ fetus, the fetus may be at risk. This is especially likely if the mother has formed anti-D antibodies during a prior pregnancy because of a mixing of maternal and fetal blood during childbirth. Unlike antibodies against ABO antigens, antibodies against the Rhesus D antigen can cross the placenta and enter the blood of the fetus. This may cause hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN), also called erythroblastosis fetalis, an illness in which fetal red blood cells are destroyed by maternal antibodies, causing anemia. This illness may range from mild to severe. If it is severe, it may cause brain damage and is sometimes fatal for the fetus or newborn. Fortunately, HDN can be prevented by preventing the formation of anti-D antibodies in the Rh- mother. This is achieved by injecting the mother with a medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.

Geographic Distribution of Rhesus Blood Types

The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system, as there is with the ABO system. The aboriginal inhabitants of the Americas and Australia originally had very close to 100 per cent Rh+ blood. The frequency of the Rh+ blood type is also very high in African populations, at about 97 to 99 per cent. In East Asia, the frequency of Rh+ is slightly lower, at about 93 to 99 per cent. Europeans have the lowest frequency of the Rh+ blood type at about 83 to 85 per cent.

What explains the population variation in Rhesus blood types? Prior to the advent of modern medicine, Rh+ positive children conceived by Rh- women were at risk of fetal or newborn death or impairment from HDN. This was an enigma, because presumably, natural selection would work to remove the rarer phenotype (Rh-) from populations. However, the frequency of this phenotype is relatively high in many populations.

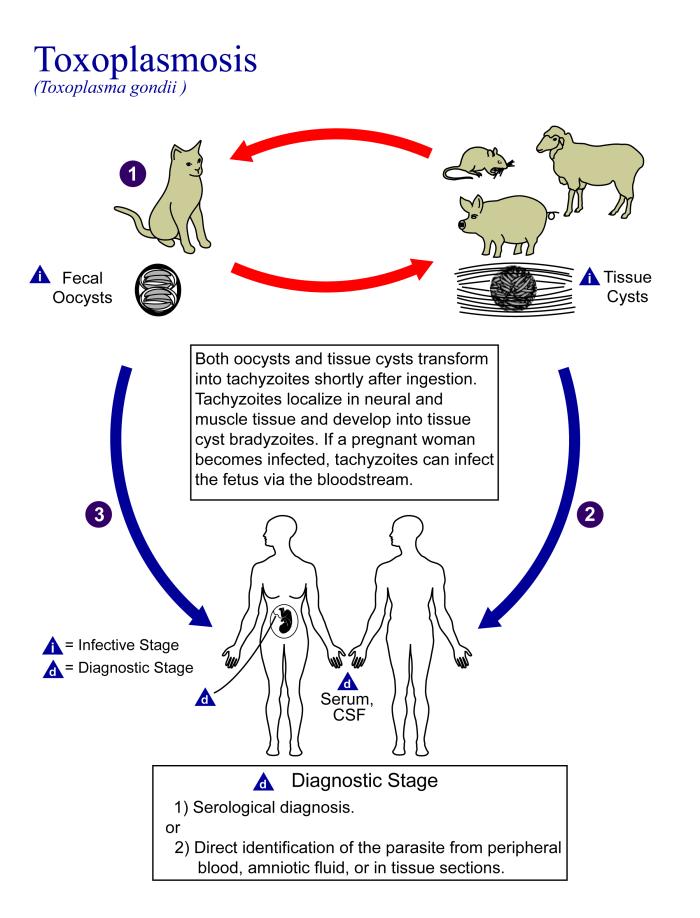

Recent studies have found evidence that natural selection may actually favor heterozygotes for the Rhesus D antigen. The selective agent in this case is thought to be toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, which is very common worldwide. You can see a life cycle diagram of the parasite in Figure 6.5.7. Infection by this parasite often causes no symptoms at all, or it may cause flu-like symptoms for a few days or weeks. Exposure to the parasite has been linked, however, to increased risk of mental disorders (such as schizophrenia), neurological disorders (such as Alzheimer’s), and other neurological problems, including delayed reaction times. One study found that people who tested positive for antibodies to the parasite were more than twice as likely to be involved in traffic accidents.

People who are heterozygous for the D antigen appear less likely to develop the negative neurological and mental effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection. This could help explain why both phenotypes (Rh+ and Rh-) are maintained in most populations. There are also striking geographic differences in the prevalence of toxoplasmosis worldwide, ranging from zero to 95 per cent in different regions. This could explain geographic variation in the D antigen worldwide, because its strength as a selective agent would vary with its prevalence.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Myth |

Reality |

| “Your nutritional needs can be determined by your ABO blood type. Knowing your blood type allows you to choose the appropriate foods that will help you lose weight, increase your energy, and live a longer, healthier life.” | This idea was proposed in 1996 in a New York Times bestseller Eat Right for Your Type, by Peter D’Adamo, a naturopath. Naturopathy is a method of treating disorders that involves the use of herbs, sunlight, fresh air, and other natural substances. Some medical doctors consider naturopathy a pseudoscience. A major scientific review of the blood type diet could find no evidence to support it. In one study, adults eating the diet designed for blood type A showed improved health — but this occurred in everyone, regardless of their blood type. Because the blood type diet is based solely on blood type, it fails to account for other factors that might require dietary adjustments or restrictions. For example, people with diabetes — but different blood types — would follow different diets, and one or both of the diets might conflict with standard diabetes dietary recommendations and be dangerous. |

| “ABO blood type is associated with certain personality traits. People with blood type A, for example, are patient and responsible, but may also be stubborn and tense, whereas people with blood type B are energetic and creative, but may also be irresponsible and unforgiving. In selecting a spouse, both your own and your potential mate’s blood type should be taken into account to ensure compatibility of your personalities.” | The belief that blood type is correlated with personality is widely held in Japan and other East Asian countries. The idea was originally introduced in the 1920s in a study commissioned by the Japanese government, but it was later shown to have no scientific support. The idea was revived in the 1970s by a Japanese broadcaster, who wrote popular books about it. There is no scientific basis for the idea, and it is generally dismissed as pseudoscience by the scientific community. Nonetheless, it remains popular in East Asian countries, just as astrology is popular in many other countries. |

6.5 Summary

- Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of antigens on the surface of red blood cells. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens.

- Antigens are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self or non-self. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens, leading to the destruction of cells bearing the antigens.

- The ABO blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by a single gene with three common alleles on chromosome 9. There are four possible ABO blood types: A, B, AB, and O. The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. People with type O blood are universal donors, and people with type AB blood are universal recipients.

- The frequencies of ABO blood type alleles and blood groups vary around the world. The allele for the B antigen is least common, and blood type O is the most common. The evolutionary forces of founder effect, genetic drift, and natural selection are responsible for the geographic distribution of ABO alleles and blood types. People with type O blood, for example, may be somewhat resistant to malaria, possibly giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

- The Rhesus blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by two genes with many alleles on chromosome 1. There are five common Rhesus antigens, of which antigen D is most significant. Individuals who have antigen D are called Rh+, and individuals who lack antigen D are called Rh-. Rh- mothers of Rh+ fetuses may produce antibodies against the D antigen in the fetal blood, causing hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN).

- The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system. This variation may be explained by natural selection that favors heterozygotes for the D antigen, because this genotype seems to be protected against some of the neurological consequences of the common parasitic infection toxoplasmosis.

6.5 Review Questions

- Define blood type and blood group system.

- Explain the relationship between antigens and antibodies.

- Identify the alleles, genotypes, and phenotypes in the ABO blood group system.

- Discuss the medical significance of the ABO blood group system.

- Compare the relative worldwide frequencies of the three ABO alleles.

- Give examples of how different ABO blood types vary in their susceptibility to diseases.

- Describe the Rhesus blood group system.

- Relate Rhesus blood groups to blood transfusions.

- What causes hemolytic disease of the newborn?

- Describe how toxoplasmosis may explain the persistence of the Rh- blood type in human populations.

- A woman is blood type O and Rh-, and her husband is blood type AB and Rh+. Answer the following questions about this couple and their offspring.

- What are the possible genotypes of their offspring in terms of ABO blood group?

- What are the possible phenotypes of their offspring in terms of ABO blood group?

- Can the woman donate blood to her husband? Explain your answer.

- Can the man donate blood to his wife? Explain your answer.

- Type O blood is characterized by the presence of O antigens — explain why this statement is false.

- Explain why newborn hemolytic disease may be more likely to occur in a second pregnancy than in a first.

6.5 Explore More

Why do blood types matter? – Natalie S. Hodge, TED-Ed, 2015.

How do blood transfusions work? – Bill Schutt, TED-Ed, 2020.

Attributes

Figure 6.5.1

Following the Blood Donation Trail by EJ Hersom/ USA Department of Defense is in the public domain. [Disclaimer: The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.]

Figure 6.5.2

Antibody by Fvasconcellos on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.3

ABO system codominance.svg, adapted by YassineMrabet (original “Codominant” image from US National Library of Medicine) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.4

ABO_blood_type.svg by InvictaHOG on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.5

Blood Donor and recipient ABO by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 6.5.6

- Map of Blood Group A by Muntuwandi at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

- Map of Blood Group B by Muntuwandi at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

- Map of Blood Group O by anthro palomar at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 6.5.7

Toxoplasma_gondii_Life_cycle_PHIL_3421_lores by Alexander J. da Silva, PhD/Melanie Moser, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention‘s Public Health Image Library (PHIL#3421) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes was created by Christine Miller.

References

Dean, L. (2005). Chapter 4 Hemolytic disease of the newborn. In Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2266/

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Toxoplasmosis [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/toxoplasmosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20356249

MedlinePlus. (2019, January 29). Hemolytic transfusion reaction [online article]. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_9&oldid=946440619

TED-Ed. (2015, June 29). Why do blood types matter? – Natalie S. Hodge. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfZhb6lmxjk&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, February 18). How do blood transfusions work? – Bill Schutt. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcZKbjYyOfE&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 10). Chromosome 1. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_1&oldid=955942444

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 20). Chromosome 9. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_9&oldid=946440619

Structures containing neuronal cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

http://humanbiology.pressbooks.tru.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/06/human-heartbeat-daniel_simon.mp3

Lub, Dub

Lub dub, lub dub, lub dub... That’s how the sound of a beating heart is typically described. Those are also the only two sounds that should be audible when listening to a normal, healthy heart through a stethoscope, as in Figure 14.3.1. If a doctor hears something different from the normal lub dub sounds, it’s a sign of a possible heart abnormality. What causes the heart to produce the characteristic lub dub sounds? Read on to find out.

Introduction to the Heart

The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum (breastbone), slightly to the left of the center of the chest. A normal adult heart is about the size of a fist. The function of the heart is to pump blood through blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. The continuous flow of blood through the system is necessary to provide all the cells of the body with oxygen and nutrients, and to remove their metabolic wastes.

Structure of the Heart

The heart has a thick muscular wall that consists of several layers of tissue. Internally, the heart is divided into four chambers through which blood flows. Because of heart valves, blood flows in just one direction through the chambers.

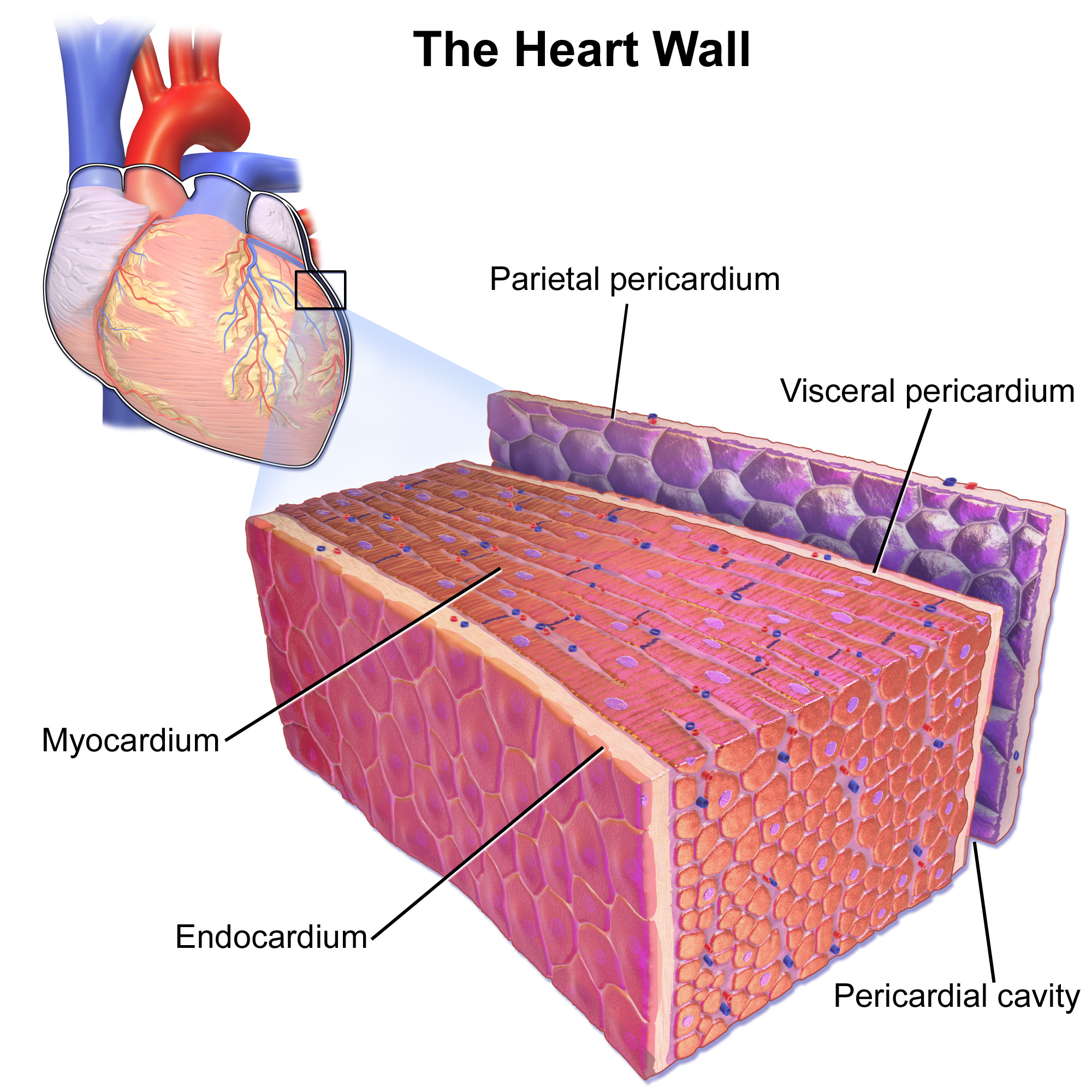

Heart Wall

As shown in Figure 14.3.2, the wall of the heart is made up of three layers, called the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium.

- The endocardium is the innermost layer of the heart wall. It is made up primarily of simple epithelial cells. It covers the heart chambers and valves. A thin layer of connective tissue joins the endocardium to the myocardium.

- The myocardium is the middle and thickest layer of the heart wall. It consists of cardiac muscle surrounded by a framework of collagen. There are two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium: cardiomyocytes — which have the ability to contract easily — and pacemaker cells, which conduct electrical impulses that cause the cardiomyocytes to contract. About 99 per cent of cardiac muscle cells are cardiomyocytes, and the remaining one per cent is pacemaker cells. The myocardium is supplied with blood vessels and nerve fibres via the pericardium.

- The pericardium is a protective sac that encloses and protects the heart. The pericardium consists of two membranes (visceral pericardium and parietal pericardium), between which there is a fluid-filled cavity. The fluid helps to cushion the heart, and also lubricates its outer surface.

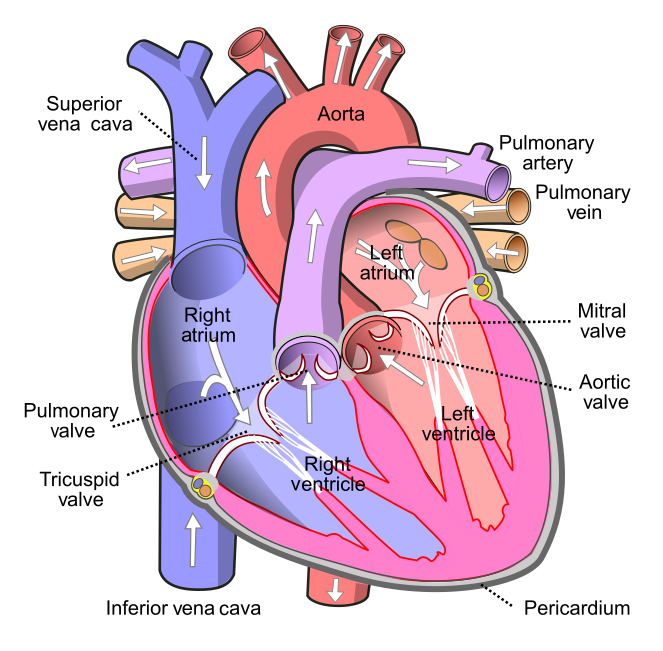

Heart Chambers

As shown in Figure 14.3.3 the four chambers of the heart include two upper chambers called atria (singular, atrium), and two lower chambers called ventricles. The atria are also referred to as receiving chambers, because blood coming into the heart first enters these two chambers. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the upper and lower body through the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, respectively. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs through the pulmonary veins. The ventricles are also referred to as discharging chambers, because blood leaving the heart passes out through these two chambers. The right ventricle discharges blood to the lungs through the pulmonary artery, and the left ventricle discharges blood to the rest of the body through the aorta. The four chambers are separated from each other by dense connective tissue consisting mainly of collagen.

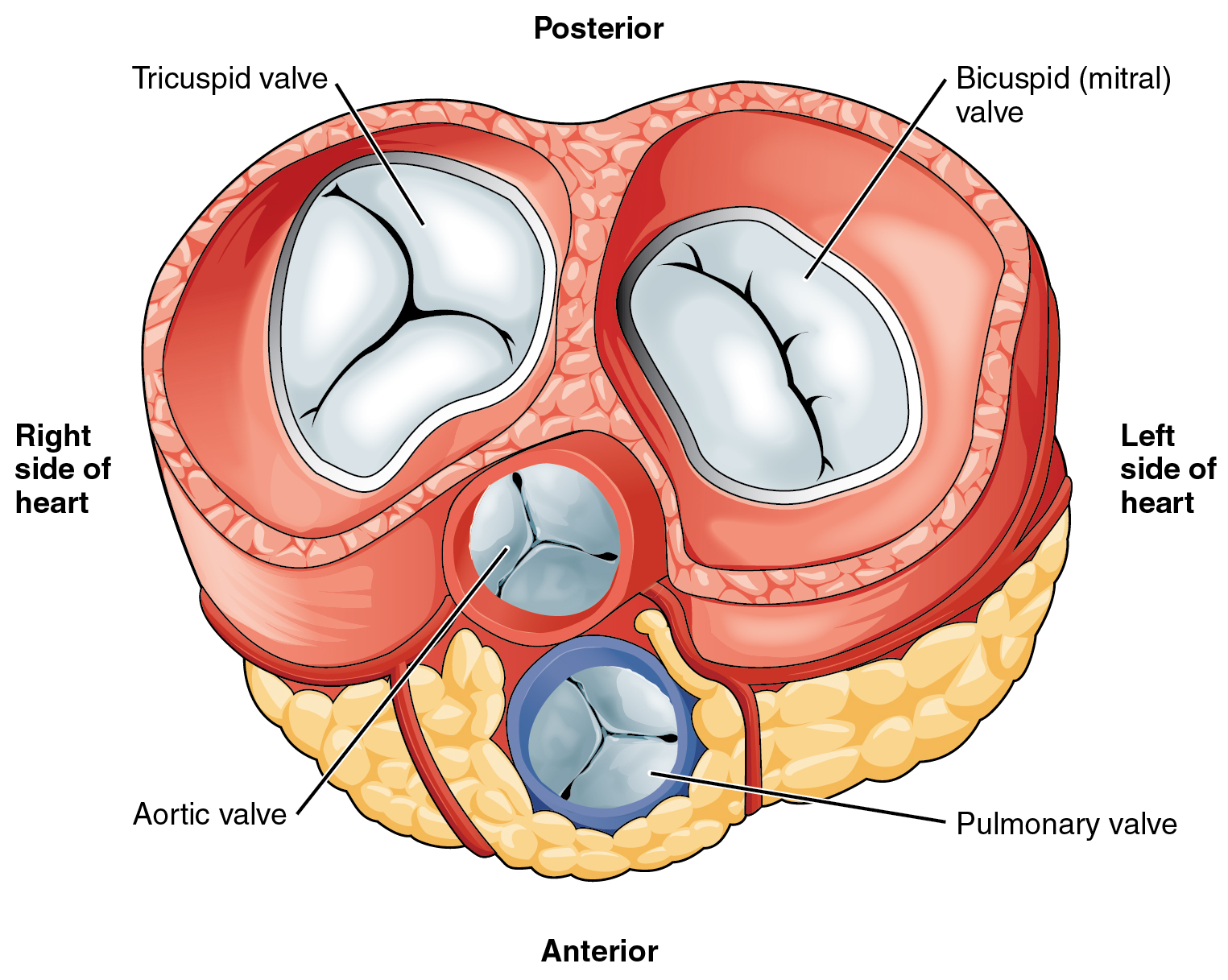

Heart Valves

Figure 14.3.4 shows the location of the heart's four valves in a top-down view, looking down at the heart as if the arteries and veins feeding into and out of the heart were removed. The heart valves allow blood to flow from the atria to the ventricles, and from the ventricles to the pulmonary artery and aorta. The valves are constructed in such a way that blood can flow through them in only one direction, thus preventing the backflow of blood. Figure 14.3.5 shows how valves open to let blood into the appropriate chamber, and then close to prevent blood from moving in the wrong direction and the next chamber contracts. The four valves are the:

- Tricuspid atrioventricular valve, (can be shortened to tricuspid AV valve) which allows blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

- Bicuspid atrioventricular valve (also know as the mitral valve), which allows blood to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle.

- Pulmonary semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery.

- Aortic semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

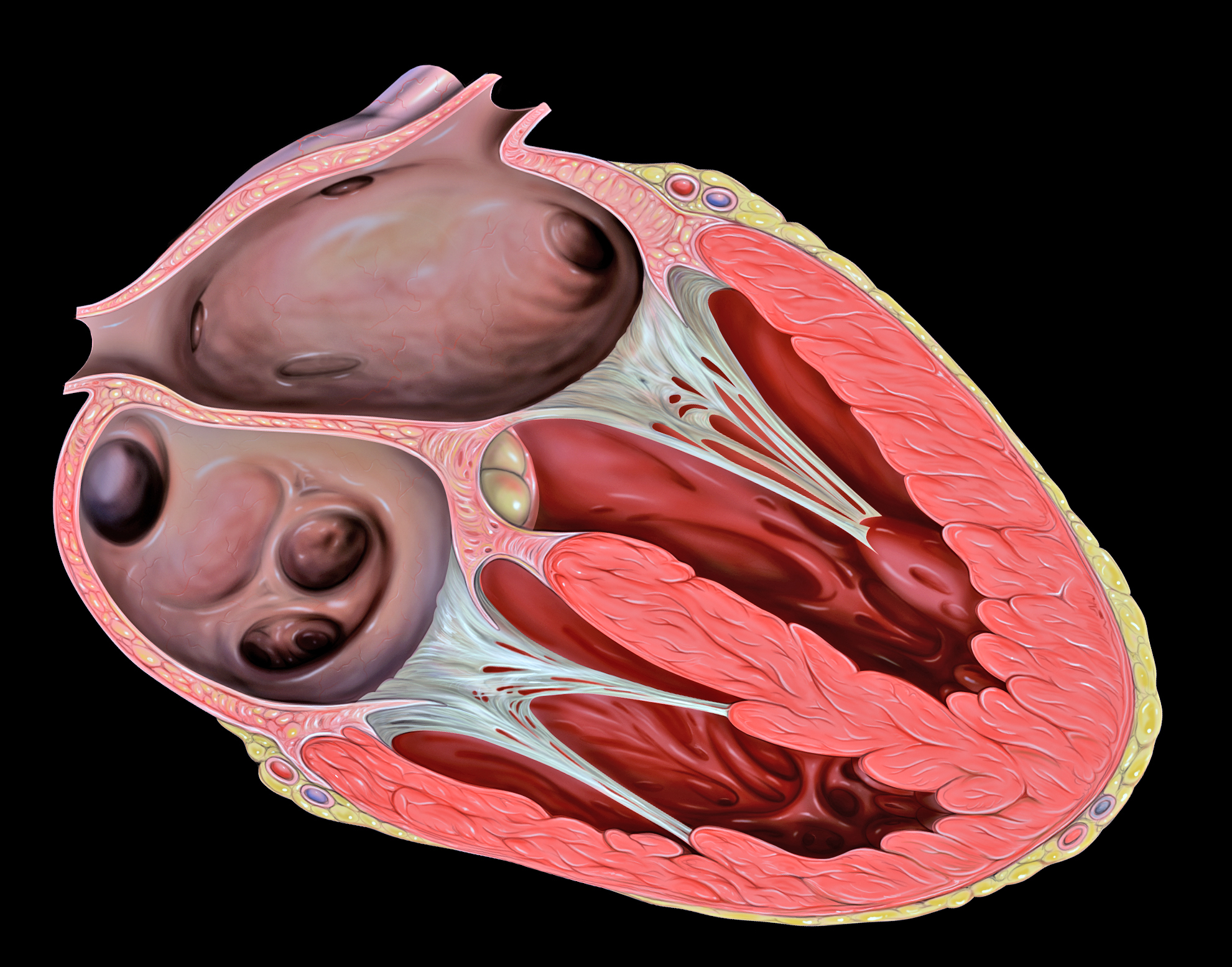

The two atrioventricular (AV) valves prevent backflow when the ventricles are contracting, while the semilunar valves prevent backflow from vessels. This means that the AV valves must withstand much more pressure than do the semilunar valves. In order to withstand the force of the ventricles contracting (to prevent blood from backflowing into the atria), the AV valves are reinforced with structures called chordae tendineae — tendon-like cords of connective tissue which anchor the valve and prevent it from prolapse. Figure 14.3.6 shows the structure and location of the chordae tendoneae.

The chordae tendoneae are under such force that they need special attachments to the interior of the ventricles where they anchor. Papillary muscles are specialized muscles in the interior of the ventricle that provide a strong anchor point for the chordae tendineae.

Coronary Circulation

The cardiomyocytes of the muscular walls of the heart are very active cells, because they are responsible for the constant beating of the heart. These cells need a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients. The carbon dioxide and waste products they produce also must be continuously removed. The blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells make up the coronary circulation. Note that the blood vessels of the coronary circulation supply heart tissues with blood, and are different from the blood vessels that carry blood to and from the chambers of the heart as part of the general circulation. Coronary arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle cells. Coronary veins remove deoxygenated blood from the heart muscles cells.

- There are two coronary arteries — a right coronary artery that supplies the right side of the heart, and a left coronary artery that supplies the left side of the heart. These arteries branch repeatedly into smaller and smaller arteries and finally into capillaries, which exchange gases, nutrients, and waste products with cardiomyocytes.

- At the back of the heart, small cardiac veins drain into larger veins, and finally into the great cardiac vein, which empties into the right atrium. At the front of the heart, small cardiac veins drain directly into the right atrium.

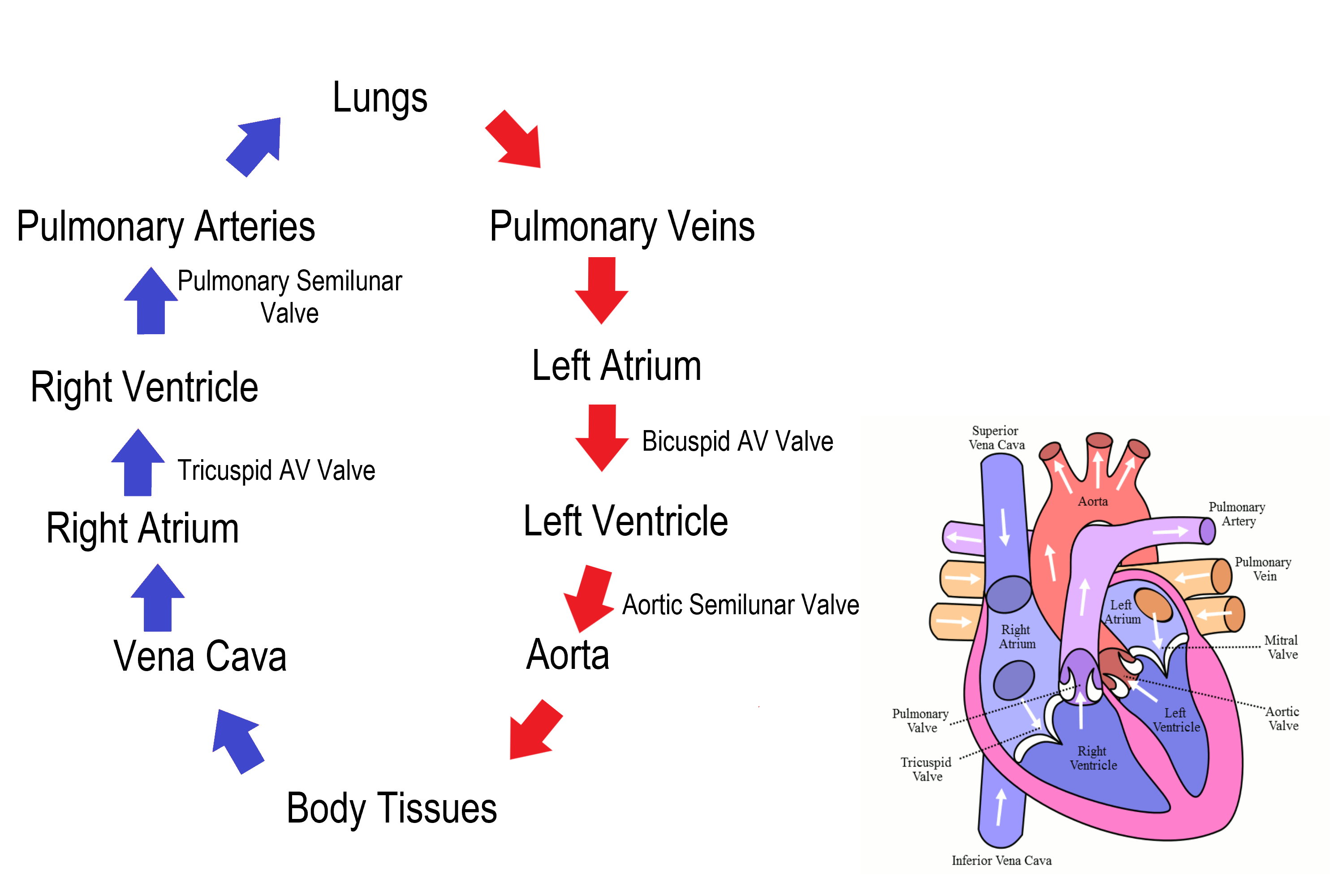

Blood Circulation Through the Heart

Figure 14.3.7 shows how blood circulates through the chambers of the heart. The right atrium collects blood from two large veins, the superior vena cava (from the upper body) and the inferior vena cava (from the lower body). The blood that collects in the right atrium is pumped through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. From the right ventricle, the blood is pumped through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery. The pulmonary artery carries the blood to the lungs, where it enters the pulmonary circulation, gives up carbon dioxide, and picks up oxygen. The oxygenated blood travels back from the lungs through the pulmonary veins (of which there are four), and enters the left atrium of the heart. From the left atrium, the blood is pumped through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From the left ventricle, the blood is pumped through the aortic valve into the aorta, which subsequently branches into smaller arteries that carry the blood throughout the rest of the body. After passing through capillaries and exchanging substances with cells, the blood returns to the right atrium via the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, and the process begins anew.

Cardiac Cycle

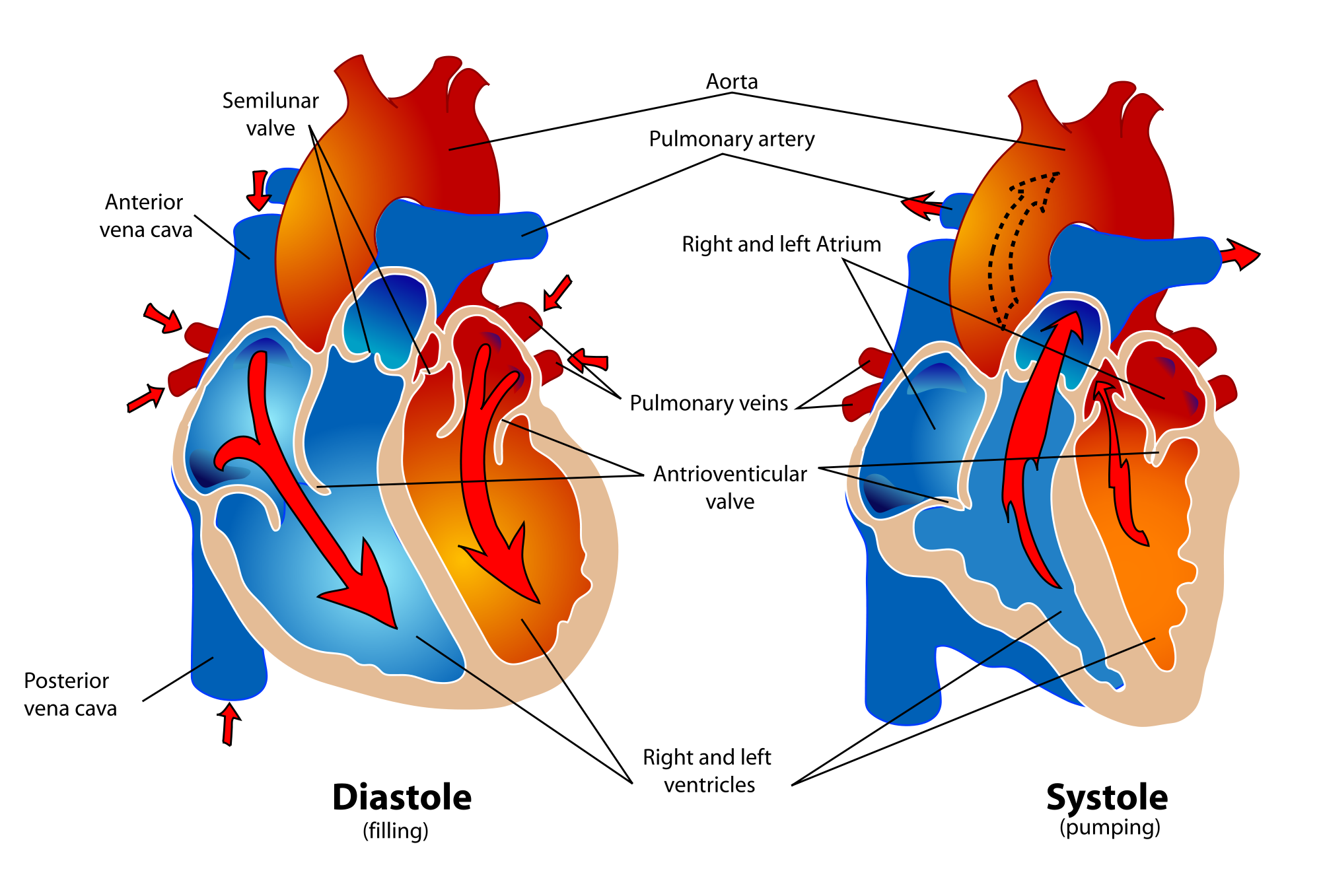

The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat, which includes one iteration of the lub and dub sounds heard through a stethoscope. During the cardiac cycle, the atria and ventricles work in a coordinated fashion so that blood is pumped efficiently through and out of the heart. The cardiac cycle includes two parts, called diastole and systole, which are illustrated in the diagrams in Figure 14.3.8.

- During diastole, the atria contract and pump blood into the ventricles, while the ventricles relax and fill with blood from the atria.

- During systole, the atria relax and collect blood from the lungs and body, while the ventricles contract and pump blood out of the heart.

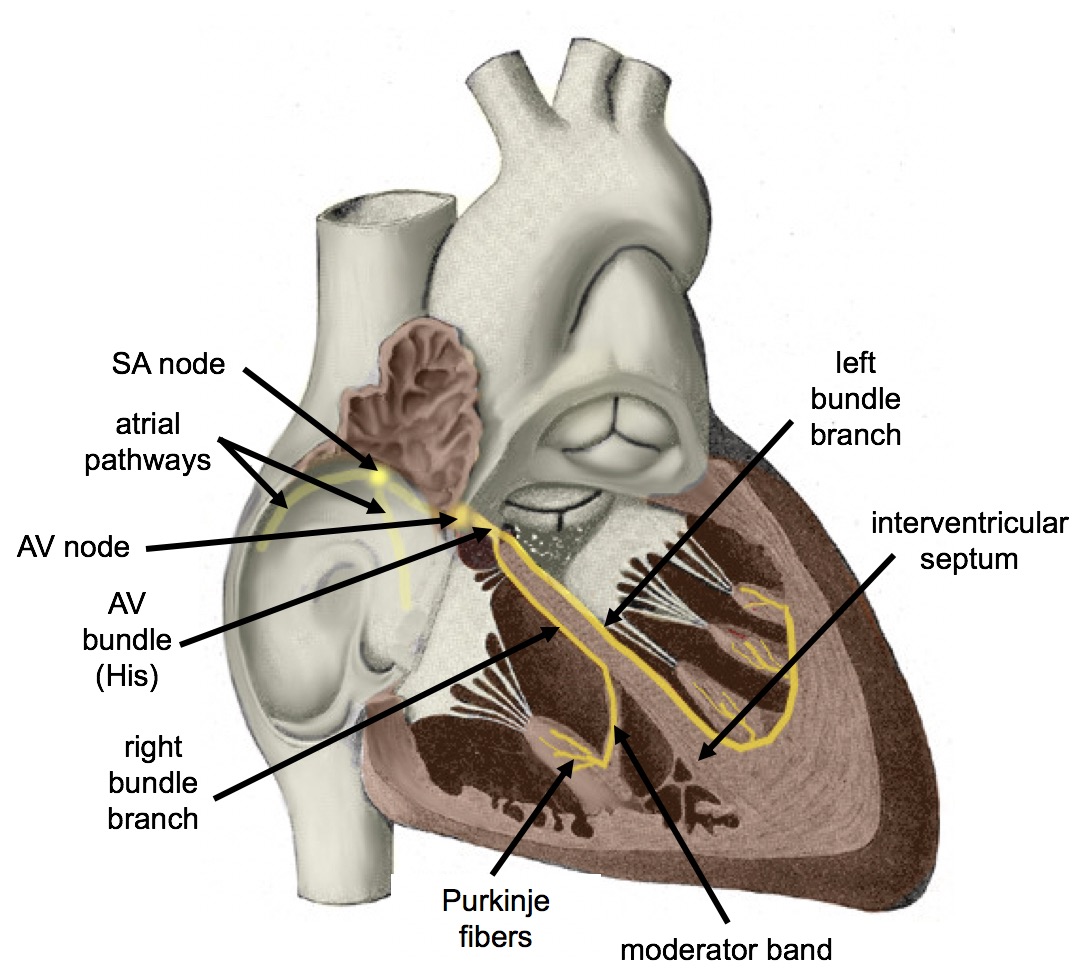

Electrical Stimulation of the Heart

The normal, rhythmical beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells, which are located in an area of the heart called the sinoatrial node (shown in Figure 14.3.9). The pacemaker cells create electrical signals with the movement of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and calcium ions) into and out of the cells. For each cardiac cycle, an electrical signal rapidly travels first from the sinoatrial node, to the right and left atria so they contract together. Then, the signal travels to another node, called the atrioventricular node (Figure 14.3.9), and from there to the right and left ventricles (which also contract together), just a split second after the atria contract.

The normal sinus rhythm of the heart is influenced by the autonomic nervous system through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. These nerves arise from two paired cardiovascular centers in the medulla of the brainstem. The parasympathetic nerves act to decrease the heart rate, and the sympathetic nerves act to increase the heart rate. Parasympathetic input normally predominates. Without it, the pacemaker cells of the heart would generate a resting heart rate of about 100 beats per minute, instead of a normal resting heart rate of about 72 beats per minute. The cardiovascular centers receive input from receptors throughout the body, and act through the sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, as needed. Increased physical activity, for example, is detected by receptors in muscles, joints, and tendons. These receptors send nerve impulses to the cardiovascular centers, causing sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, and allowing more blood to flow to the muscles.

Besides the autonomic nervous system, other factors can also affect the heart rate. For example, thyroid hormones and adrenal hormones (such as epinephrine) can stimulate the heart to beat faster. The heart rate also increases when blood pressure drops or the body is dehydrated or overheated. On the other hand, cooling of the body and relaxation — among other factors — can contribute to a decrease in the heart rate.

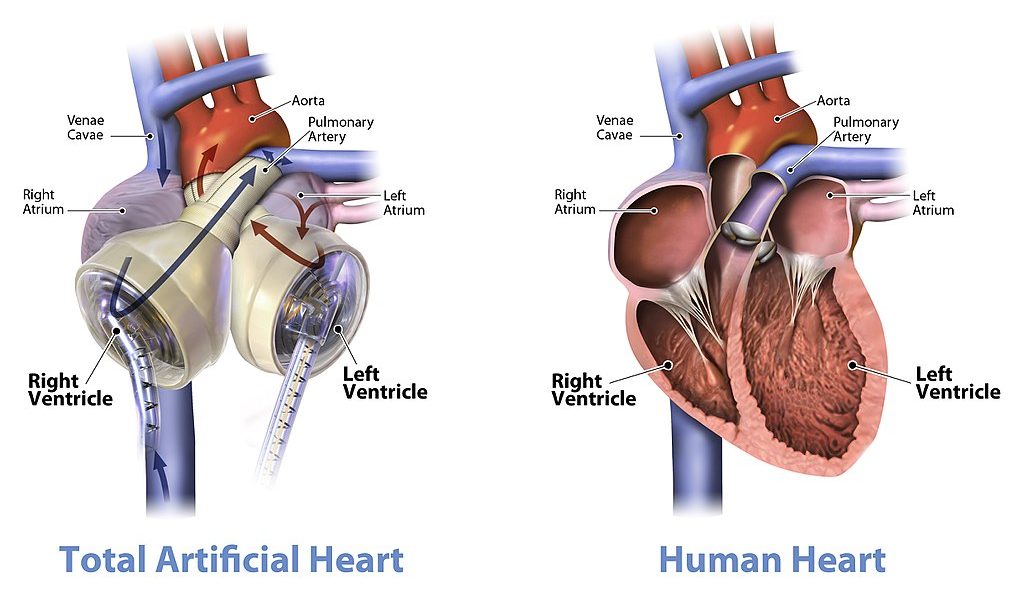

Feature: Human Biology in the News

When a patient’s heart is too diseased or damaged to sustain life, a heart transplant is likely to be the only long-term solution. The first successful heart transplant was undertaken in South Africa in 1967. There are over 2,200 Canadians walking around today because of life-saving heart transplant surgery. Approximately 180 heart transplant surgeries are performed each year, but there are still so many Canadians on the transplant list that some die while waiting for a heart. The problem is that far too few hearts are available for transplant — there is more demand (people waiting for a heart transplant) than supply (organ donors). Sometimes, recipient hopefuls will receive a device called a Total Artificial Heart (see Figure 14.3.10), which can buy them some time until a donor heart becomes available.

Watch the video below "Total artificial heart option..." from Stanford Health Care to see how it works:

https://youtu.be/1PtxaxcPnGc

Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage), Stanford Health Care, 2014.

14.3 Summary

- The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum and slightly to the left of the center of the chest. Its function is to pump blood through the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system.

- The wall of the heart consists of three layers. The middle layer, the myocardium, is the thickest layer and consists mainly of cardiac muscle. The interior of the heart consists of four chambers, with an upper atrium and lower ventricle on each side of the heart. Blood enters the heart through the atria, which pump it to the ventricles. Then the ventricles pump blood out of the heart. Four valves in the heart keep blood flowing in the correct direction and prevent backflow.

- The coronary circulation consists of blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells, and is different from the general circulation of blood through the heart chambers. There are two coronary arteries that supply the two sides of the heart with oxygenated blood. Cardiac veins drain deoxygenated blood back into the heart.

- Deoxygenated blood flows into the right atrium through veins from the upper and lower body (superior and inferior vena cava, respectively), and oxygenated blood flows into the left atrium through four pulmonary veins from the lungs. Each atrium pumps the blood to the ventricle below it. From the right ventricle, deoxygenated blood is pumped to the lungs through the two pulmonary arteries. From the left ventricle, oxygenated blood is pumped to the rest of the body through the aorta.

- The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat. It includes diastole — when the atria contract — and systole, when the ventricles contract.

- The normal, rhythmic beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node. Electrical signals from the pacemaker cells travel to the atria, and cause them to contract. Then, the signals travel to the atrioventricular node and from there to the ventricles, causing them to contract. Electrical stimulation from the autonomic nervous system and hormones from the endocrine system can also influence heartbeat.

14.3 Review Questions

- What is the heart, where is located, and what is its function?

-

- Describe the coronary circulation.

- Summarize how blood flows into, through, and out of the heart.

- Explain what controls the beating of the heart.

- What are the two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium? What are the differences between these two types of cells?

- Explain why the blood from the cardiac veins empties into the right atrium of the heart. Focus on function (rather than anatomy) in your answer.

14.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM

Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face, TED, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M

Watch a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI

A Change of Heart: My Transplant Experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse, TEDx Talks, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk

Heart Transplant Recipient Meets Donor Family For The First Time, WMC Health, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 14.3.1

- Female clinician dressed in scrubs using a stethoscope by Amanda Mills, USCDCP, on Pixnio is used under a CC0 public domain certification license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/publicdomain/).

- Human heart beating loud and strong (audio) by Daniel Simion on Soundbible.com is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.2

Blausen_0470_HeartWall by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.3

Diagram_of_the_human_heart_(cropped).svg by Wapcaplet on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 14.3.4

Heart_Valves by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.5

CG_Heart Valve Animation by DrJanaOfficial on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 14.3.6

Heart_tee_four_chamber_view by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator from Yale University School of Medicine, on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) license.

Figure 14.3.7

Circulation of blood through the heart by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license. [Original image in the bottom right is by Wapcaplet / CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Figure 14.3.8

Human_healthy_pumping_heart_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Common is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 14.3.9

Cardiac_Conduction_System by Cypressvine on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 19.12 Heart valves with the atria and major vessels removed [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 19.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/19-1-heart-anatomy#fig-ch20_01_04

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. (n.d.). https://www.heartandstroke.ca/

Sliwa, K., Zilla, P. (2017, December 7). 50th anniversary of the first human heart transplant—How is it seen today? European Heart Journal, 38(46):3402–3404. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx695

Stanford Health Care. (2014, December 3). Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PtxaxcPnGc&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2012, March 21). Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM&feature=youtu.be

TEDx Talks. (2018, April 18). A change of heart: My transplant experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI&feature=youtu.be

UMagazine. (2015, Fall). The cutting edge: Patient first to bridge from experimental total artificial heart to transplant. UCLA Health. https://www.uclahealth.org/u-magazine/patient-first-to-bridge-from-experimental-total-artificial-heart-to-transplant

UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids. (2018, February 7). Watch a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M&feature=youtu.be

WMC Health. (2018, September 13). Heart transplant recipient meets donor family for the first time. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk&feature=youtu.be

A sequence of nucleotides in DNA or RNA that codes for a molecule that has a function.

A variant form of a given gene, meaning it is one of two or more versions of a known mutation at the same place on a chromosome. It can also refer to different sequence variations for a several-hundred base-pair or more region of the genome that codes for a protein.

The part of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of any individual, which determines one of its characteristics (phenotype).

Body cavity that fills the lower half of the trunk and holds the kidneys and the digestive and reproductive organs.

The process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional protein.

A biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1. Complex carbohydrates are polymers made from monomers of simple carbohydrates, also termed monosaccharides.

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large, Y-shaped protein produced mainly by plasma cells that is used by the immune system to neutralize pathogens such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses.

The loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population.

Variation in the relative frequency of different genotypes in a small population, owing to the chance disappearance of particular genes as individuals die or do not reproduce.

Refers to the relationship between two versions of a gene. Individuals receive two versions of each gene, known as alleles, from each parent. If the alleles of a gene are different, one allele will be expressed; it is the dominant gene. The effect of the other allele, called recessive, is masked.

A condition in which you don't have enough healthy red blood cells to carry adequate oxygen to the body's tissues resulting in symptoms including weakness and fatigue.

A nervous system cell that provides support for neurons and helps them transmit nerve impulses.