6.9 Case Study Conclusion: Your Genes May Help You Save a Life

Case Study Conclusion: Your Genes May Help You Save a Life

As you have learned in this chapter, humans are much more genetically similar to each other than they are different. Any two people on Earth are 99.9 per cent genetically identical to each other — but the mere 0.1 per cent that is different can be very important, as in the case of bone marrow donation to treat diseases such as leukemia. A good match must exist between a bone marrow donor and recipient in genes that encode for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) proteins. As you have learned, antigens are molecules — often on the surface of cells — that the immune system uses to identify foreign invaders. If a patient receives a bone marrow transplant from a donor that has different types of HLAs than the patient does, antibodies in their immune system will identify the antigens as nonself and will launch an attack on the transplanted cells. Also, since bone marrow produces immune cells, antibodies in the transplanted tissue can actually attack the patient’s own cells using the same mechanism.

As you have also learned, a good HLA match is often difficult to find, even between full siblings. Finding a match in the registries is particularly hard for non-Caucasian people — and even harder for people from multiethnic backgrounds, such as seven-year-old Mateo, who you read about in the beginning of this chapter. Mateo is of African, Japanese, and Caucasian descent — a relatively rare combination. Because HLA matches are more likely to occur between people of the same ethnicity, the donor registries would ideally have sufficient potential donors from every ethnicity and ethnic combination. Unfortunately, some ethnicities are not sufficiently represented in the donor registry. According to the U.S. National Marrow Donor Program, while 97 per cent of Caucasian patients find a match, the match rate drops to 83 per cent for Hispanic or Latino patients and 76 per cent for African American or black patients. Multi-ethnic patients generally have an even harder time finding a match because the relative rareness of their particular ethnic combination in the general population makes it less likely that enough people of their same ancestry are registered donors.

As you learned in this chapter, human variation has historically been classified in several different ways, some of which resulted from or have contributed to racism. Most biological traits in humans exist on a continuum, and attempting to create biological categories of race based on discrete categories using a handful of traits is generally arbitrary and inaccurate. Gene flow through migration and mating between populations, genetic drift, and natural selection results in a gradual, clinal distribution of many human traits, rather than discrete categories. Mateo, for example, cannot be neatly placed into one racial category or another. Race and ethnic identity, however, remain important social and cultural concepts.

Mateo’s ancestry does play a role in determining his specific types of HLA proteins, and he is more likely to find a bone marrow match with a donor of an ethnic background similar to his own. Although there is much more genetic variation within races than between races, HLA types tend to correlate with ethnicity more than some other traits. As you have seen throughout this chapter, some environmental factors in different geographic regions have provided strong natural selection pressures, resulting in the development of genetic differences between people whose ancestors came from different areas. For example, adaptations to differing UV levels, diseases, altitudes, and climates all likely led to the evolution of human variations in skin colour, blood cells, and body morphology. This type of association between race and ethnicity and genetic variation is similar to the link between ethnicity and HLA type.

Mateo’s family was not able to find a match for him in the bone marrow registries, unlike the little boy pictured in Figure 6.9.1, but they are not giving up hope. His parents have started working with organizations to host bone marrow drives, where potential donors can provide cheek swabs to add themselves to the donor registry. His parents have contacted the news media with Mateo’s story, and family and friends are getting the word out on social media that more donors are needed, particular those with Mateo’s specific combination of ethnicities. They hope that even if they are unable to find a match for Mateo, bringing awareness to the issue may increase the ethnic diversity of the donor registry to save other lives.

You Can Help!

According to the Canadian Blood Services, more donors are needed to join the bone marrow registry. Currently, there is a need for more young male donors: male stem cell donors are more likely to be matched with recipients because they offer better patient outcomes after transplant. There is also a need for donors with diverse ethnic backgrounds, particularly Aboriginal, Hispanic, African-Canadian, Filipino, and more. DIverse donors are needed to acheive the closest possible match for HLA between the donor and the recipient.

Leukemia is not the only disease in which treatment involves bone marrow transplant — this course of action is often taken for conditions such as:

- Aplastic anemia

- Inherited immune system disorders

- Inherited metabolic disorders

- Bone marrow diseases

- Lymphomas

Are you registered? If not, it is a relatively simple process that could save someone’s life. A cheek swab is all that is initially needed. Only about one in 430 potential donors will actually be matched with a patient, and if you are chosen, it means that you are one of the only people on Earth who can donate to this patient because of your genetic similarity! If you decide to donate, bone marrow will either be surgically removed from the back of your pelvic bone, or blood-forming cells will be removed non-surgically from your bloodstream. Most donors are able to return to their normal activities one to seven days after donation — a small price to pay for potentially saving someone’s life!

Stem cell donation: Step by step, hemaquebec1998, 2015.

Marrow donors talk about donating and the donation process, Be The Match, 2012.

Chapter 6 Summary

In this chapter, you learned about human variation and its origins. Specifically, you learned that:

- No two human individuals are genetically identical (except for monozygotic twins), but the human species as a whole exhibits relatively little genetic diversity relative to other mammalian species. Genetically, two people chosen at random are likely to be 99.9 per cent identical.

- Of the total genetic variation in humans, about 90 per cent occurs between people within continental populations, and only about 10 per cent occurs between people from different continents. Older, larger populations tend to have greater genetic variation, because there’s been more time and there are more people in which to accumulate mutations.

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms account for most human genetic differences. Allele frequencies for polymorphic genes generally have a clinal, rather than discrete, distribution. A minority of alleles seem to cluster in particular geographic areas, such as the allele for no antigen in the Duffy blood group. Such alleles may be useful as genetic markers to establish the ancestry of individuals.

- Knowledge of genetic variation can help us understand our similarities and differences. It can also help us reconstruct our evolutionary origins and history as a species. For example, the distribution of modern human genetic variation is consistent with the out-of-Africa hypothesis for the origin of modern humans.

- An important benefit of studying human genetic variation is learning more about the genetic basis of human diseases. This should help us find more effective treatments and cures.

- Humans seem to have a need to classify and label people based on their similarities and differences. Three approaches to classifying human variation are typological, populational, and clinal approaches.

-

- The typological approach involves creating a system of discrete categories, or races (no longer used). This approach was widely used by scientists until the early 20th century. Racial categories are based on observable phenotypic traits (such as skin colour), but other traits and behaviors are often mistakenly assumed to apply to racial groups, as well. The use of racial classifications often leads to racism.

- By the mid-20th century, scientists started advocating a population approach (no longer used). This assumes that the breeding population, which is the unit of evolution, is the only biologically meaningful group. While this approach makes sense in theory, in reality, it can rarely be applied to actual human populations. With few exceptions, most human populations are not closed breeding populations.

- By the 1960s, scientists began to use a clinal approach to classify human variation. This approach maps variation in the frequency of traits or alleles over geographic regions or worldwide. Clinal maps for many genetic traits show variation that changes gradually from one geographic area to another. Gene flow and/or natural selection can cause this type of distribution.

- Humans may respond to environmental stress in four different ways: adaptation, developmental adjustment, acclimatization, and cultural responses.

-

- An adaptation is a genetically based trait that has evolved because it helps living things survive and reproduce in a given environment. Adaptations evolve by natural selection in populations over a relatively long period to time. Examples of adaptations include sickle cell trait as an adaptation to endemic malaria and the ability to taste bitter compounds as an adaptation to bitter-tasting toxins in plants.

- A developmental adjustment is a nongenetic response to stress that occurs during infancy or childhood. It may persist into adulthood and may be irreversible. Developmental adjustment is possible because humans have a high degree of phenotypic plasticity. It may be the result of environmental stresses, such as inadequate food — which may stunt growth — or cultural practices, such as orthodontic treatments, which re-align the teeth and jaws.

- Acclimatization is the development of reversible changes to environmental stress that develop over a relatively short period of time. The changes revert to the normal baseline state after the stress is removed. Examples of acclimatization include tanning of the skin and physiological changes (such as increased sweating) that occur with heat acclimatization.

- Cultural responses consist of learned behaviors and technology that allow us to change our environment to control stress, rather than changing our bodies genetically or physiologically to cope with stress. Examples include using shelter, fire, and clothing to cope with a cold climate.

- Blood type is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of antigens on the surface of red blood cells. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens.

-

- Antigens are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self or nonself. If antigens are identified as nonself, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the nonself antigens, leading to the destruction of cells bearing the antigens.

- The ABO blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by a single gene with three common alleles on chromosome 9. There are four possible ABO blood types: A, B, AB, and O. The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. People with type O blood are universal donors, and people with type AB blood are universal recipients.

- The frequencies of ABO blood type alleles and blood groups vary around the world. The allele for the B antigen is least common, and blood type O is the most common. Evolutionary forces of founder effect, genetic drift, and natural selection are responsible for the geographic distribution of ABO alleles and blood types. For example, people with type O blood may be somewhat resistant to malaria, possibly giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

- The Rhesus blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by two genes with many alleles on chromosome 1. There are five common Rhesus antigens, of which antigen D is the most significant. Individuals who have antigen D are called Rh+, and individuals who lack antigen D are called Rh-. Rh- mothers of Rh+ fetuses may produce antibodies against the D antigen in the fetal blood, causing hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN).

- The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system. This variation may be explained by natural selection that favors heterozygotes for the D antigen, because this genotype seems to be protected against some of the neurological consequences of the common parasitic infection toxoplasmosis.

- At high altitudes, humans face the stress of hypoxia, or a lack of oxygen. Hypoxia occurs at high altitude because there is less oxygen in each breath of air and lower air pressure, which prevents adequate absorption of oxygen from the lungs.

- Initial responses to hypoxia include hyperventilation and elevated heart rate, but these responses are stressful to the body. Continued exposure to high altitude may cause high altitude sickness, with symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and loss of appetite. At higher altitudes, there is greater risk of serious illness.

- After several days at high altitude, acclimatization starts to occur in someone from a lowland population. More red blood cells and capillaries form, along with other changes. Full acclimatization may take several weeks. Returning to low altitude causes a reversal of the changes to the pre-high altitude state in a matter of weeks.

- Well over 100 million people live at altitudes higher than 2,500 metres above sea level. Some indigenous populations of Tibet, Peru, and Ethiopia have been living above 2,500 metres for thousands of years, and have evolved genetic adaptations to high altitude hypoxia. Different high altitude populations have evolved different adaptations to the same hypoxic stress. Tibetan highlanders, for example, have a faster rate of breathing and wider arteries, whereas Peruvian highlanders have larger red blood cells and a greater concentration of the oxygen-carrying protein hemoglobin.

- Both hot and cold temperatures are serious environmental stresses on the human body. In the cold, there is risk of hypothermia, which is a dangerous decrease in core body temperature. In the heat, there is risk of hyperthermia, which is a dangerous increase in core body temperature.

- According to Bergmann’s rule, body size tends to be negatively correlated with temperature, because larger body size increases heat production and decreases heat loss. The opposite holds true for small body size. Bergmann’s rule applies to many human populations that are hot or cold adapted.

- According Allen’s rule, the length of body extremities is positively correlated with temperature, because longer extremities are better at dissipating excess body heat. The opposite applies to shorter extremities. Allen’s rule applies to relative limb lengths in many human populations that have adapted to heat or cold.

- Sweating is the primary way humans lose body heat. The evaporation of sweat from the skin cools the body. This only works well when the relative humidity is fairly low. At high relative humidity, sweat does not readily evaporate to cool us down. The heat index (HI) indicates how hot it feels due to the humidity.

- Gradually working longer and harder in the heat can bring about heat acclimatization, in which the body has improved responses to heat stress. Sweating starts earlier, sweat contains less salt, and vasodilation brings heat to the surface to help cool the body. Full acclimatization takes up to 14 days and reverses just as quickly when the heat stress is removed.

- The human body can respond to cold by producing more heat (by shivering or increasing the basal metabolic rate) or by conserving heat (by vasoconstriction at the body surface or a layer of fat-insulating internal organs).

- At temperatures below freezing, the hunting response occurs to prevent cold injury (such as frostbite). This is a process of alternating vasoconstriction and vasodilation in extremities that are exposed to dangerous cold. Where temperatures are repeatedly cold but rarely below freezing, the hunting response may not occur, and the skin may remain cold due to vasoconstriction alone.

- Milk contains the sugar lactose, a disaccharide. Lactose must be broken down into its two component sugars to be absorbed by the small intestine, and the enzyme lactase is needed for this process.

- In about 60 per cent of people worldwide, the ability to synthesize lactase and digest lactose declines after the first two years of life. These people become lactose intolerant, and cannot consume much milk without suffering symptoms such as bloating, cramps, and diarrhea.

- In populations that herded milking animals for thousands of years, lactase persistence evolved. People who were able to synthesize lactase and digest lactose throughout life were strongly favored by natural selection. People who descended from these early herders generally still have lactase persistence. That includes many Europeans and European-Americans.

- Human populations may vary in how efficiently they use calories in food. Some people (especially South Pacific Islanders, Native Americans, and sub-Saharan Africans) may be able to get by on fewer calories than would be adequate for others, so they tend to easily gain weight, become obese, and develop diseases such as diabetes.

- The thrifty gene hypothesis proposes that “thrifty genes” were selected for because they allowed people to use calories efficiently and store body fat when food was plentiful so they had a reserve to use when food was scarce. According to the hypothesis, thrifty genes become detrimental and lead to obesity and diabetes when food is plentiful all of the time.

- Several assumptions underlying the thrifty gene hypothesis have been called into question, and genetic research has been unable to actually identify thrifty genes. Alternate hypotheses to the thrifty gene hypothesis have been proposed, including the drifty gene hypothesis. The latter hypothesis explains variation in the tendency to become obese by genetic drift on neutral genes.

In this chapter, you learned about how genetic variation can lead to differences in human characteristics. Genes encode for proteins, which carry out our bodies’ life processes. In the next chapter, you will learn about how proteins and other molecules make up the cells, tissues, and organs of the human body, and how these units work together in interacting systems to allow us to function.

Chapter 6 Review

- Explain why an evolutionarily older population is likely to have more genetic variation than a similarly-sized younger population.

- The genetic difference between any two people on Earth is only about 0.1 percent. Based on our evolutionary history, describe one reason why humans are relatively homogeneous genetically.

- What aspect(s) of human skin colour are due to adaptation? Be sure to define adaptation in your answer. What aspect(s) of human skin colour are due to acclimatization? Be sure to define acclimatization in your answer.

- For each of the following human responses to the environment, list whether it can be best described as an example of adaptation, acclimatization, or developmental adjustment:

- Reduction in height due to lack of food in childhood

- Resistance to malaria

- Shivering in the cold

- Changes in body size and dimensions to better tolerate heat or cold

- Give an example of a human response to environmental stress that involves changes in behavior, instead of changes in physiology.

- What are two types of environmental stresses that caused genetic changes related to hemoglobin in some populations of humans?

- The ability of an organism to change their phenotype in response to the environment is called phenotypic __________ .

- List three natural selection pressures that differ geographically across the world and contributed to the evolution of human genetic variation in different regions.

-

- You may have noticed that when a sudden hot day occurs during a cool period, it can feel even more uncomfortable than higher temperatures during a hot period — even with the same humidity levels. Using what you learned in this chapter, explain why you think that happens.

- Out of all mammals, why are humans the only ones that evolved lactase persistence?

- If the Inuit people who live in the Arctic were not able to get enough vitamin D from their diet, what do you think might happen to their skin colour over a long period of time? Explain your answer.

- Explain why malaria has been such a strong force of natural selection on human populations.

- Give one example of “heterozygote advantage” (i.e. when the heterozygous genotype has higher relative fitness than the dominant or recessive homozygous genotype) in humans.

- What is one way in which humans have evolved genetic adaptations in response to their food sources?

- Do you think adaptation to high altitude evolved once or several times? Explain your reasoning.

Attribution

Figure 6.9.1

Give Life – Donner la vie by Andrew Scheer on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en) license.

References

Be The Match. (2012, December 19). Marrow donors talk about donating and the donation process. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLO0Usg8vcY&feature=youtu.be

Canadian Blood Services. (n.d.). There is an immediate need for blood as demand is rising. https://www.blood.ca/en

hemaquebec1998. (2015, August 27).Stem cell donation: Step by step. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FyriQibRhLA&feature=youtu.be

As per caption.

The transfer of genetic variation from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations are considered to have equivalent allele frequencies and therefore effectively be a single population.

Refers to the relationship between two versions of a gene. Individuals receive two versions of each gene, known as alleles, from each parent. If the alleles of a gene are different, one allele will be expressed; it is the dominant gene. The effect of the other allele, called recessive, is masked.

A genetically-based trait that has evolved because it helps living things survive and reproduce in a given environment.

The process in which an individual organism adjusts to a change in its environment, allowing it to maintain performance across a range of environmental conditions. Acclimatization occurs in a short period of time, and within the organism's lifetime.

The process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional protein.

A sequence of nucleotides in DNA or RNA that codes for a molecule that has a function.

The part of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of any individual, which determines one of its characteristics (phenotype).

Body cavity that fills the lower half of the trunk and holds the kidneys and the digestive and reproductive organs.

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large, Y-shaped protein produced mainly by plasma cells that is used by the immune system to neutralize pathogens such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses.

Any gland of the endocrine system, which is the system of glands that releases hormones directly into the blood.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by: Christine Miller

What Is Pseudoscience?

Pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice that is presented as scientific but does not adhere to the standards and methods of science. True science is based on repeated evidence-gathering and testing of falsifiable hypotheses. Pseudoscience does not adhere to these criteria. In addition to phrenology, some other examples of pseudoscience include astrology, extrasensory perception (ESP), reflexology, reincarnation, and Scientology,

Characteristics of Pseudoscience

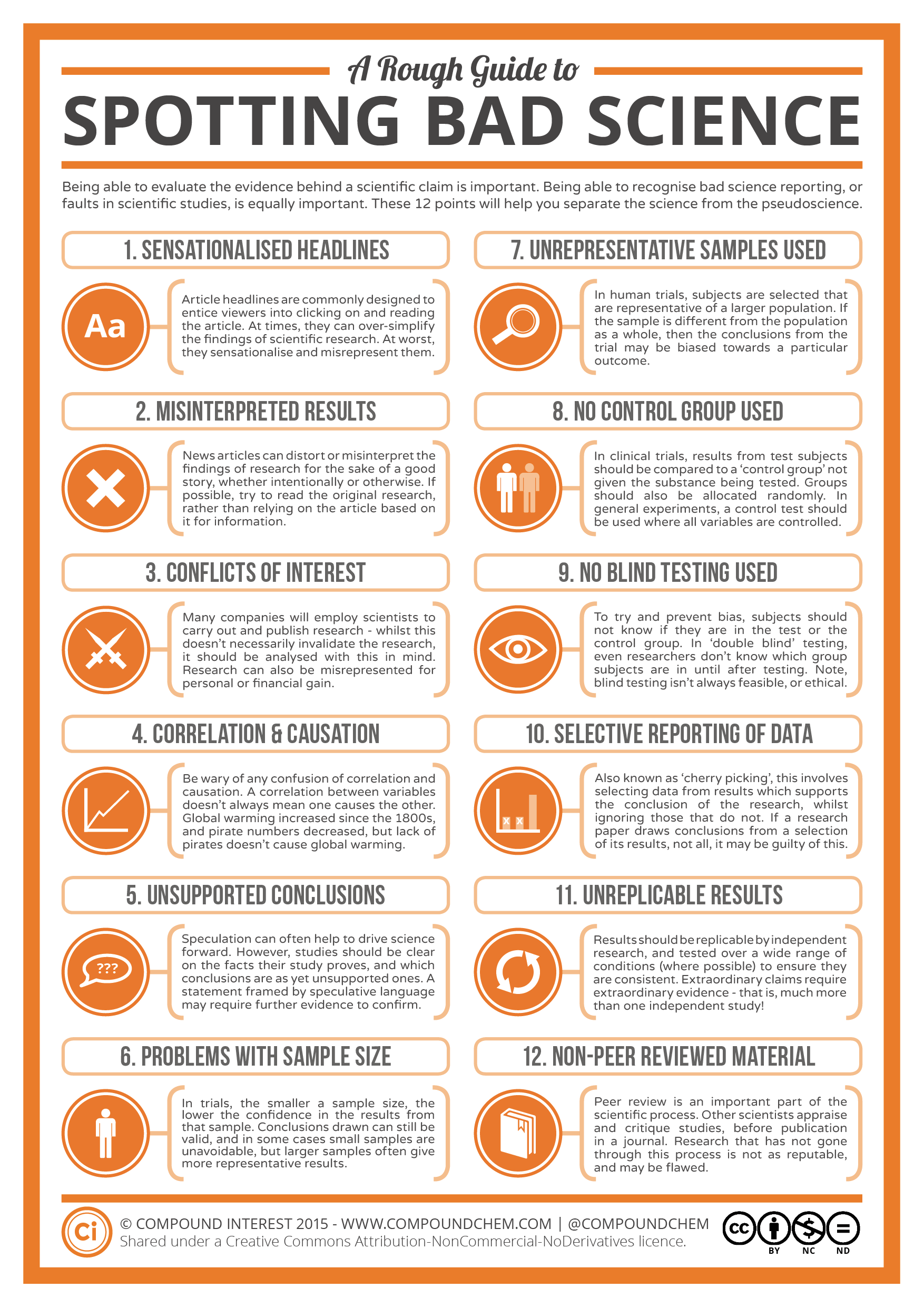

Whether a field is actually science or just pseudoscience is not always clear. However, pseudoscience generally exhibits certain common characteristics. Indicators of pseudoscience include:

- The use of vague, exaggerated, or untestable claims: Many claims made by pseudoscience cannot be tested with evidence. As a result, they cannot be falsified, even if they are not true.

- An over-reliance on confirmation rather than refutation: Any incident that appears to justify a pseudoscience claim is treated as proof of the claim. Claims are assumed true until proven otherwise, and the burden of disproof is placed on skeptics of the claim.

- A lack of openness to testing by other experts: Practitioners of pseudoscience avoid subjecting their ideas to peer review. They may refuse to share their data and justify the need for secrecy with claims of proprietary or privacy.

- An absence of progress in advancing knowledge: In pseudoscience, ideas are not subjected to repeated testing followed by rejection or refinement, as hypotheses are in true science. Ideas in pseudoscience may remain unchanged for hundreds — or even thousands — of years. In fact, the older an idea is, the more it tends to be trusted in pseudoscience.

- Personalization of issues: Proponents of pseudoscience adopt beliefs that have little or no rational basis, so they may try to confirm their beliefs by treating critics as enemies. Instead of arguing to support their own beliefs, they attack the motives and character of their critics.

- The use of misleading language: Followers of pseudoscience may use scientific-sounding terms to make their ideas sound more convincing. For example, they may use the formal name dihydrogen monoxide to refer to plain old water.

Persistence of Pseudoscience

Despite failing to meet scientific standards, many pseudosciences survive. Some pseudosciences remain very popular with large numbers of believers. A good example is astrology.

Astrology is the study of the movements and relative positions of celestial objects as a means for divining information about human affairs and terrestrial events. Many ancient cultures attached importance to astronomical events, and some developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. Throughout most of its history in the West, astrology was considered a scholarly tradition and was common in academic circles. With the advent of modern Western science, astrology was called into question. It was challenged on both theoretical and experimental grounds, and it was eventually shown to have no scientific validity or explanatory power.

Today, astrology is considered a pseudoscience, yet it continues to have many devotees. Most people know their astrological sign, and many people are familiar with the personality traits supposedly associated with their sign. Astrological readings and horoscopes are readily available online and in print media, and a lot of people read them, even if only occasionally. About a third of all adult Americans actually believe that astrology is scientific. Studies suggest that the persistent popularity of pseudosciences such as astrology reflects a high level of scientific illiteracy. It seems that many Americans do not have an accurate understanding of scientific principles and methodology. They are not convinced by scientific arguments against their beliefs.

Dangers of Pseudoscience

Belief in astrology is unlikely to cause a person harm, but belief in some other pseudosciences might — especially in health care-related areas. Treatments that seem scientific but are not may be ineffective, expensive, and even dangerous to patients. Seeking out pseudoscientific treatments may also delay or preclude patients from seeking scientifically-based medical treatments that have been tested and found safe and effective. In short, irrational health care may not be harmless.

Scientific Hoaxes, Frauds, and Fallacies

Pseudoscience is not the only way that science may be misused. Scientific hoaxes, frauds, and fallacies may misdirect the pursuit of science, put patients at risk, or mislead and confuse the public. An example of each of these misuses of science and its negative effects is described below.

The Piltdown Hoax

![Image by By James Howard McGregor [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons A side profile view of an artists rendition of what the Piltdown Man may have looked like, had he been real.](https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/acchumanbio/wp-content/uploads/sites/152/2023/10/Piltdown-Man-300x285.jpg)

Piltdown Man (see picture left) was a paleontological hoax in which bone fragments were presented as the fossilized remains of a previously unknown early human. These fragments consisted of parts of a skull and jawbone, reported to have been found in 1908 in a gravel pit at Piltdown, East Sussex, England. The significance of the specimen remained the subject of controversy until it was exposed in 1953 as a hoax. It eventually came to light that the specimen consisted of the lower jawbone of an orangutan deliberately combined with skull bones of a modern human. The Piltdown hoax is perhaps the most infamous paleontological hoax ever perpetrated, both for its impact on the direction of research on human evolution and for the length of time between its "discovery" and its full exposure as a forgery.

![Photo by Anrie [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons A replica of the infamous Piltdown skull. The skull is encased in a glass sphere. The replica shows portions of the skull which were bone in white, and the portions of the skull which were inferred in black.](https://pressbooks.ccconline.org/acchumanbio/wp-content/uploads/sites/152/2023/10/Sterkfontein_Piltdown_man-300x294.jpg)

In 1912, the head of the geological department at the British Museum proposed that Piltdown man represented an evolutionary missing link between apes and humans. With its human-like cranium and ape-like jaw, it seemed to support the idea then prevailing in England that human evolution began with the brain. The Piltdown specimen led scientists down a blind alley in the belief that the human brain increased in size before the jaw underwent size reductions to become more like the modern human jaw. This belief confused and misdirected the study of human evolution for decades, and actual fossils of early humans were ignored because they didn't support the accepted paradigm.

The Vaccine-Autism Fraud

You may have heard that certain vaccines put the health of young children at risk. This persistent idea is not supported by scientific evidence or accepted by the vast majority of experts in the field. It stems largely from an elaborate medical research fraud that was reported in a 1998 article published in the respected British medical journal, The Lancet. The main author of the article was a British physician named Andrew Wakefield. In the article, Wakefield and his colleagues described case histories of 12 children, most of whom were reported to have developed autism soon after the administration of the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine.

Several subsequent peer-reviewed studies failed to show any association between the MMR vaccine and autism. It also later emerged that Wakefield had received research funding from a group of people who were suing vaccine manufacturers. In 2004, ten of Wakefield's 12 coauthors formally retracted the conclusions in their paper. In 2010, editors of The Lancetretracted the entire paper. That same year, Wakefield was charged with deliberate falsification of research and barred from practicing medicine in the United Kingdom. Unfortunately, by then, the damage had already been done. Parents afraid that their children would develop autism had refrained from having them vaccinated. British MMR vaccination rates fell from nearly 100 per cent to 80 per cent in the years following the study. The consensus of medical experts today is that Wakefield's fraud put hundreds of thousands of children at risk because of the lower vaccination rates and also diverted research efforts and funding away from finding the true cause of autism.

Correlation-Causation Fallacy

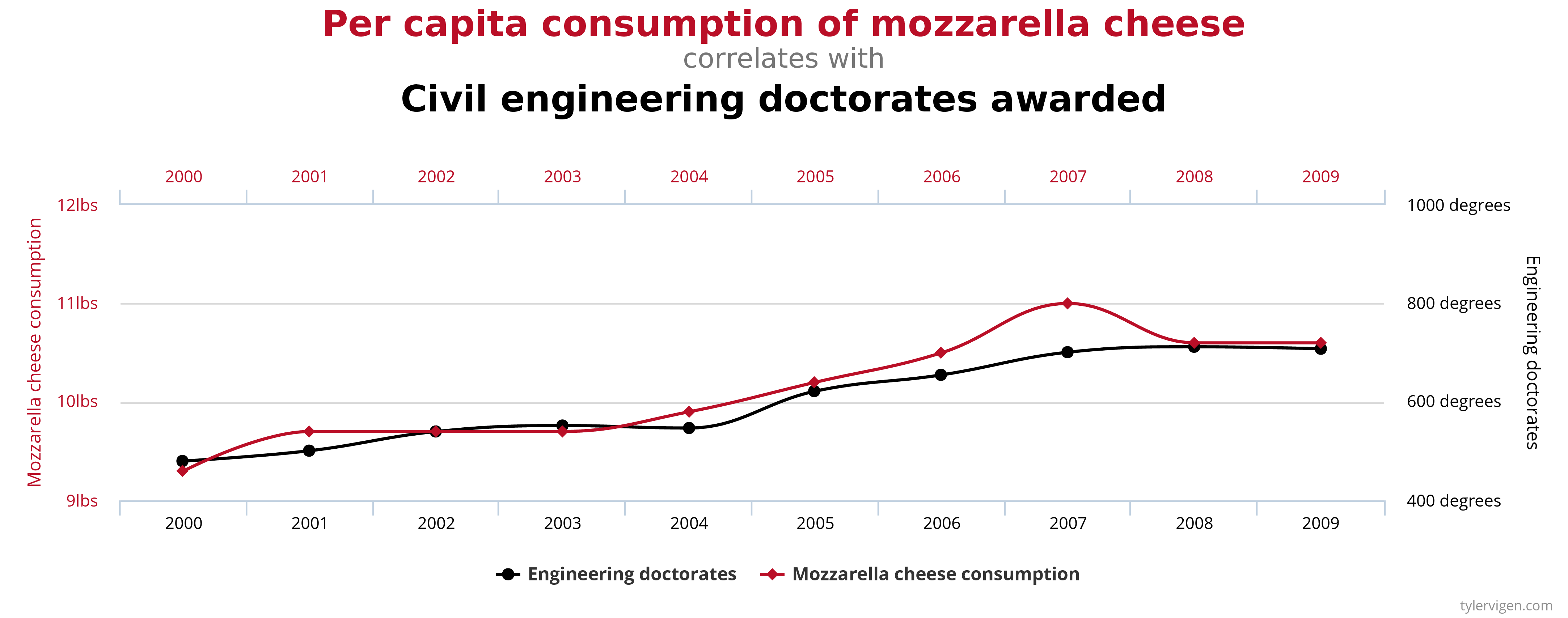

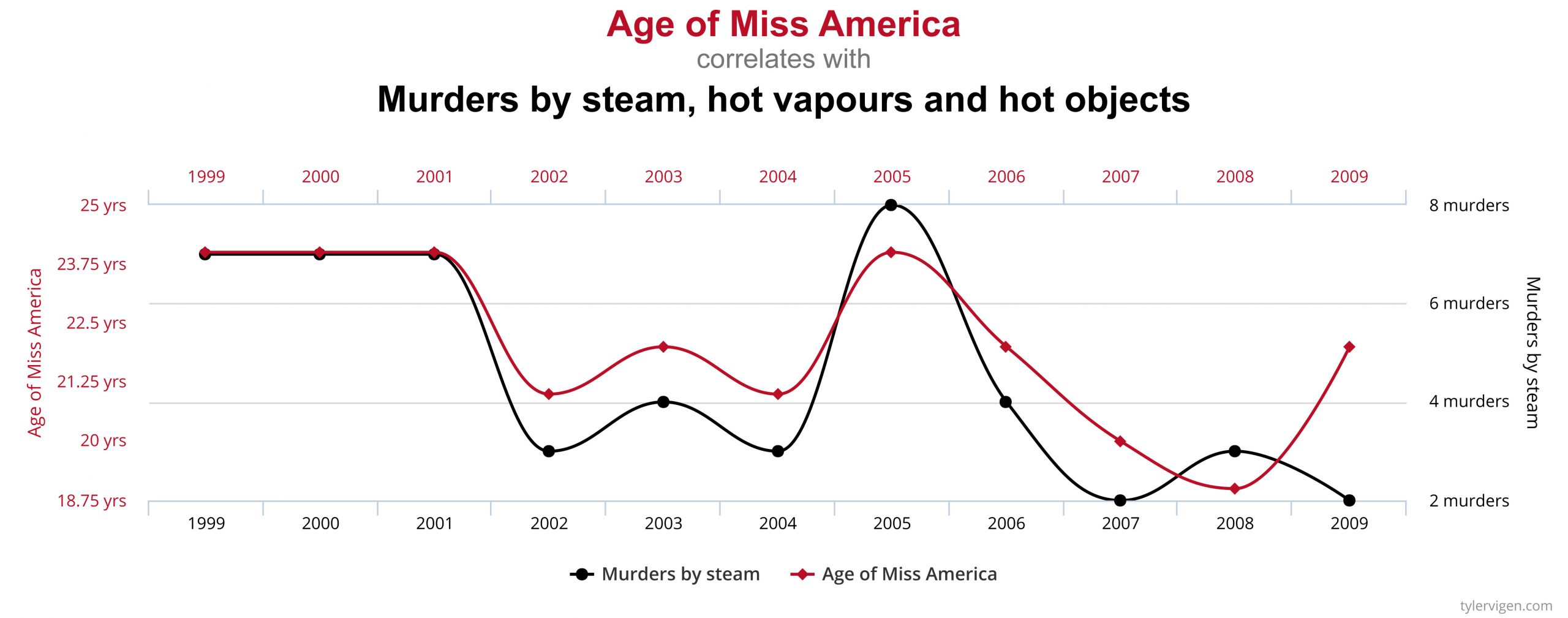

Many statistical tests used in scientific research calculate correlations between variables. Correlation refers to how closely related two data sets are, which may be a useful starting point for further investigation. Correlation, however, is also one of the most misused types of evidence, primarily because of the logical fallacy that correlation implies causation. In reality, just because two variables are correlated does not necessarily mean that either variable causes the other.

A few simple examples, illustrated by the graphs below, can be used to demonstrate the correlation-causation fallacy. Assume a study found that both per capita consumption of mozzarella cheese and the number of Civil Engineering doctorates awarded are correlated; that is, rates of both events increase together. If correlation really did imply causation, then you could conclude from the second example that the increase in age of Miss America causes an increase in murders of a specific type or vice versa.

An actual example of the correlation-causation fallacy occurred during the latter half of the 20th century. Numerous studies showed that women taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to treat menopausal symptoms also had a lower-than-average incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD). This correlation was misinterpreted as evidence that HRT protects women against CHD. Subsequent studies that controlled other factors related to CHD disproved this presumed causal connection. The studies found that women taking HRT were more likely to come from higher socio-economic groups, with better-than-average diets and exercise regimens. Rather than HRT causing lower CHD incidence, these studies concluded that HRT and lower CHD were both effects of higher socio-economic status and related lifestyle factors.

Check out this “Rough Guide to Spotting Bad Science” infographic from Compound Interest:

1.7 Summary

- Pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice that is presented as scientific, but does not adhere to scientific standards and methods.

- Indicators of pseudoscience include untestable claims, lack of openness to testing by experts, absence of progress in advancing knowledge, and attacks on the motives and character of critics.

- Some pseudosciences, including astrology, remain popular. This suggests that many people do not possess the scientific literacy needed to distinguish pseudoscience from true science, or to be convinced by scientific arguments against them.

- Belief in a pseudoscience such as astrology is unlikely to cause harm, but belief in pseudoscientific medical treatments may be harmful.

- In addition to pseudoscience, other examples of the misuse of science include scientific hoaxes (such as the Piltdown hoax), scientific frauds (such as the MMR vaccine-autism fraud), and scientific fallacies (such as the correlation-causation fallacy).

1.7 Review Questions

- Define pseudoscience. Give three examples.

- What are some indicators that a claim, belief, or practice might be pseudoscience rather than true science?

- Astrology was once considered a science, and it was common in academic circles. Why did its status change from a science to a pseudoscience?

- What are possible reasons that some pseudosciences remain popular even after they have been shown to have no scientific validity or explanatory power?

- List three other ways besides pseudoscience that science can be misused, and identify an example of each.

- Explain how misuses of science may waste money and effort. How can they potentially cause harm to the public?

- Many claims made by pseudoscience cannot be tested with evidence. From a scientific perspective, why is it important that claims be testable?

- What do you think is the difference between pseudoscience and belief?

- If you see a website that claims that an herbal supplement causes weight loss and they use a lot of scientific terms to explain how it works, can you be assured that the drug is scientifically proven to work? If not, what are some steps you can take to determine whether or not the drug does in fact work?

- Why do you think it was problematic that Andrew Wakefield received funding from a group of people who were suing vaccine manufacturers?

- What do you think it says about the 1998 Wakefield paper that ten of the 12 coauthors formally retracted their conclusions?

1.7 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E91bGT9BjYk

How to spot a misleading graph - Lea Gaslowitz, TED-Ed, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxYrzzy3cq8

How statistics can be misleading - Mark Liddell, TED-Ed, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 1.7.1

Zodiac Signs Cancer Aquarius Aries Gemini Leo from Max Pixel, is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en).

Figure 1.7.2

Piltdown Man - McGregor model, by James Howard McGregor on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 1.7.3

Sterkfontein Piltdown man, by Anrie on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 1.7.4

Spurious Correlations (Causation Fallacy) - Consumption of mozzarella cheese and awarded Doctorates by Tyler Vigen on Tylervigen.com is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) license.

Figure 1.7.5

Spurious Correlations (Causation Fallacy) - Miss America and Murder, by Tyler Vigen, is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) license.

Figure 1.7.6

A rough guide to spotting bad science, by Compound Interest, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/ca/) license

References

TED-Ed. (2017, July 6). How to spot a misleading graph - Lea Gaslowitz. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E91bGT9BjYk&feature=youtu.be

Wakefield, A.J., Murch, S.H., Anthony, A., Linnell, J., Casson, D.M., Malik, M., et al. (1998). Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet, 351: 637–41.

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 18). Andrew Wakefield. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Andrew_Wakefield&oldid=963243135

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

A Bag Full of Jell-O

The simple cut-away model of an animal cell (Figure 4.4.1) shows that a cell resembles a plastic bag full of Jell-O. Its basic structure is a plasma membrane filled with cytoplasm. Like Jell-O containing mixed fruit (Figure 4.4.2), the cytoplasm of the cell also contains various structures, including a nucleus and other organelles. Your body is composed of trillions of cells, but all of them perform the same basic life functions. They all obtain and use energy, respond to the environment, and reproduce. How do your cells carry out these basic functions and keep themselves — and you — alive? To answer these questions, you need to know more about the structures that make up cells, starting with the plasma membrane.

What is the Plasma Membrane?

The plasma membrane is a structure that forms a barrier between the cytoplasm inside the cell and the environment outside the cell. Without the plasma membrane, there would be no cell. Although it is very thin and flexible, the plasma membrane protects and supports the cell by controlling everything that enters and leaves it. It allows only certain substances to pass through, while keeping others in or out. To understand how the plasma membrane controls what passes into or out of the cell, you need to know its basic structure.

Phospholipid Bilayer

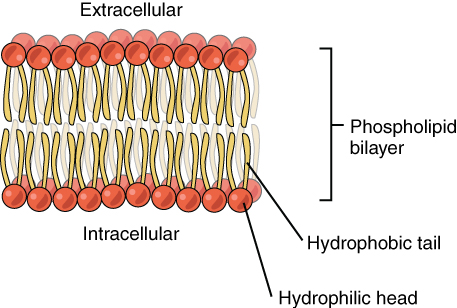

The plasma membrane is composed mainly of phospholipids, which consist of fatty acids and alcohol. The phospholipids in the plasma membrane are arranged in two layers, called a phospholipid bilayer. As shown in the simplified diagram in Figure 4.4.3, each individual phospholipid molecule has a phosphate group head (in red) and two fatty acid tails (in yellow). The head “loves” water (hydrophilic) and the tails “hate” water (hydrophobic). The water-hating tails are on the interior of the membrane, whereas the water-loving heads point outward, toward either the cytoplasm (intracellular) or the fluid that surrounds the cell (extracellular).

Hydrophobic molecules can easily pass through the plasma membrane if they are small enough, because they are water-hating like the interior of the membrane. Hydrophilic molecules, on the other hand, cannot pass through the plasma membrane — at least not without help — because they are water-loving like the exterior of the membrane.

Other Molecules in the Plasma Membrane

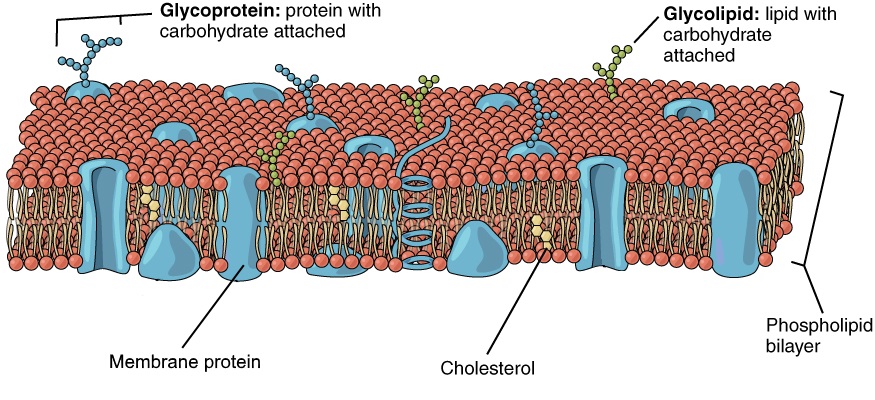

The plasma membrane also contains other molecules, primarily other lipids and proteins. The yellow molecules in the diagram here, for example, are the lipid cholesterol. Molecules of the steroid lipid cholesterol help the plasma membrane keep its shape. Proteins in the plasma membrane (shown blue in Figure 4.4.4) include: transport proteins that assist other substances in crossing the cell membrane, receptors that allow the cell to respond to chemical signals in its environment, and cell-identity markers that indicate what type of cell it is and whether it belongs in the body.

Additional Functions of the Plasma Membrane

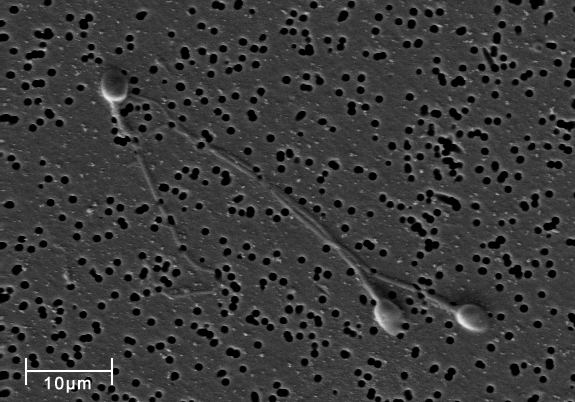

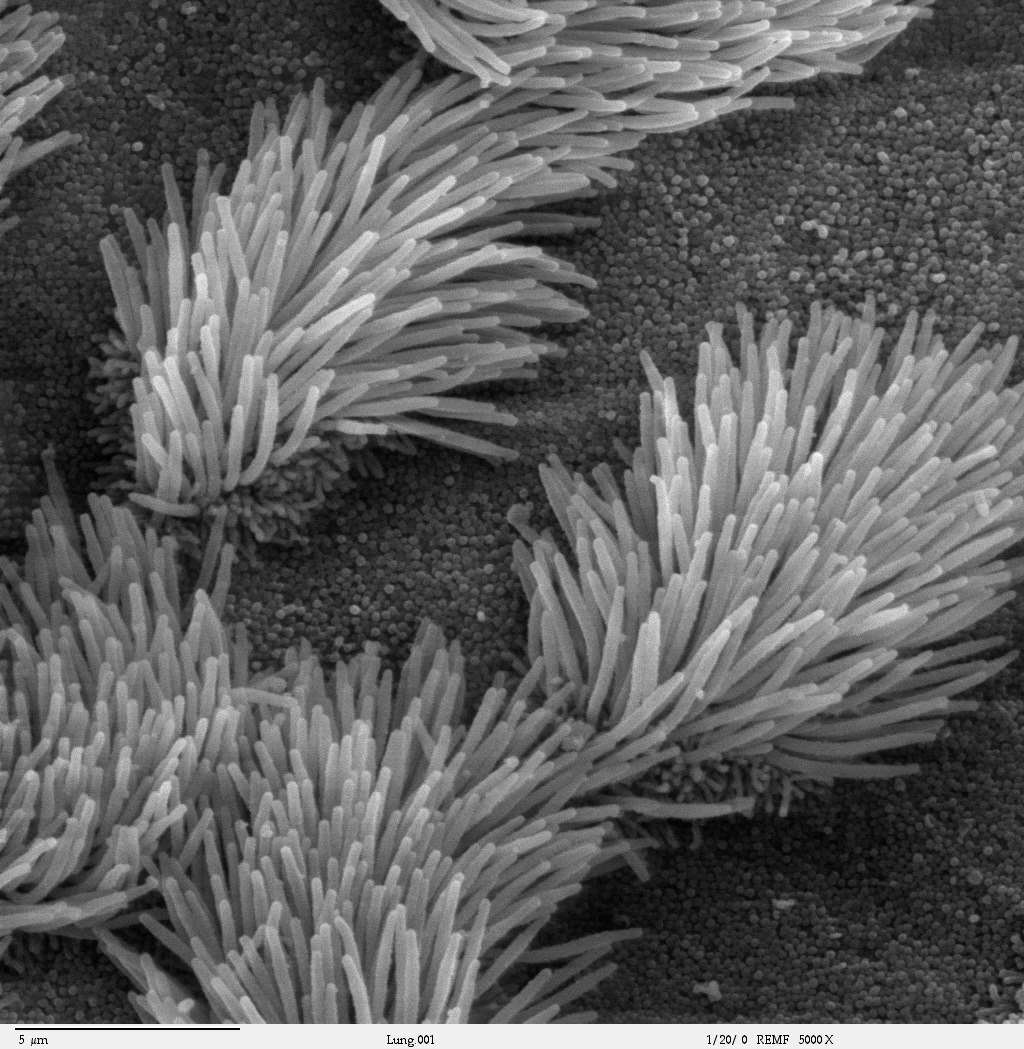

The plasma membrane may have extensions, such as whip-like flagella (singular flagellum) or brush-like cilia (singular cilium), shown below (Figure 4.4.5), that give it other functions. In single-celled organisms, these membrane extensions may help the organisms move. In multicellular organisms, the extensions have different functions. For example, the cilia on human lung cells sweep foreign particles and mucus toward the mouth and nose, while the flagellum on a human sperm cell allows it to swim.

Feature: My Human Body

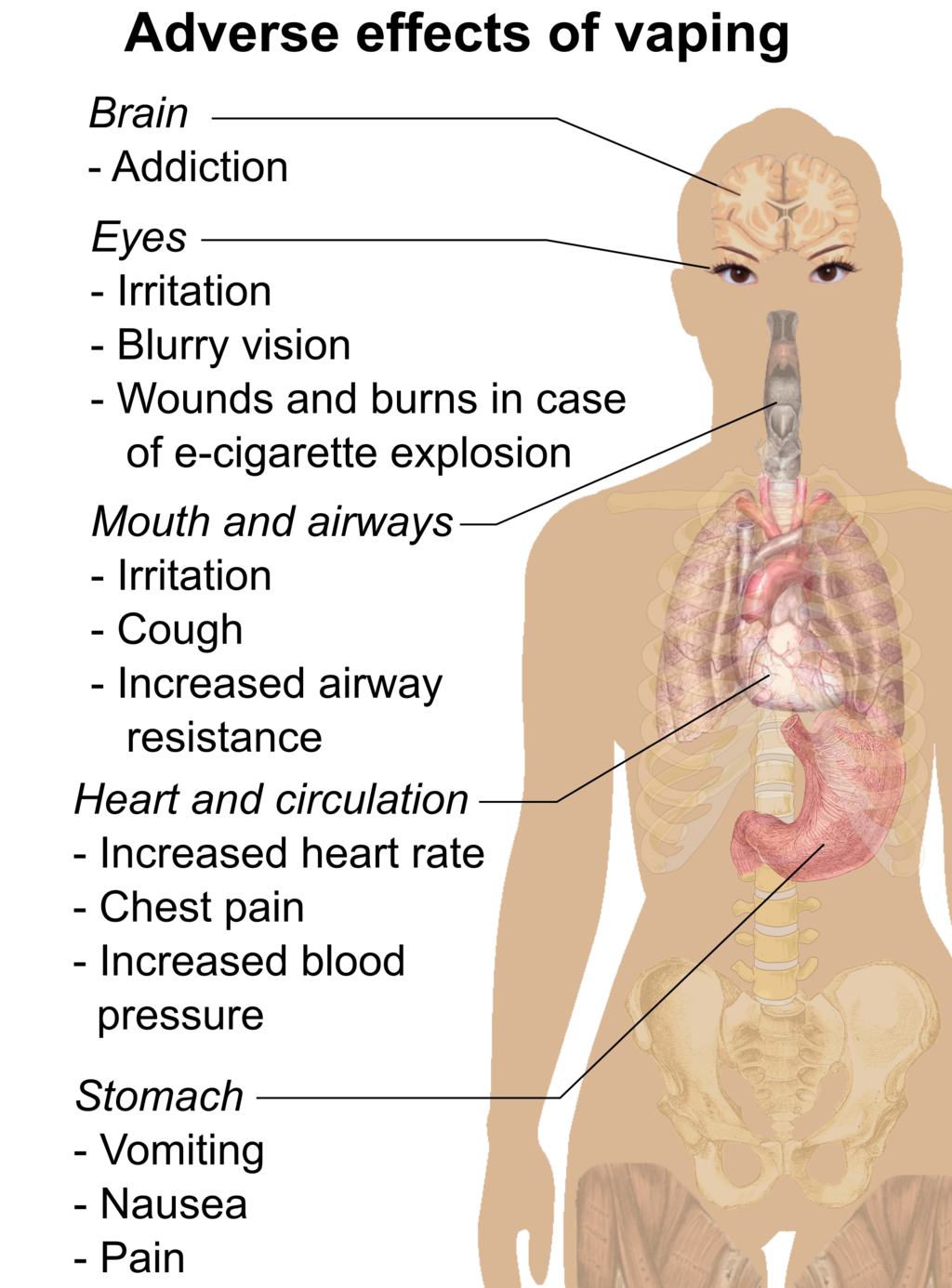

If you smoke or use e-cigarettes (vaping) and need another reason to quit, here's a good one. We usually think of lung cancer as the major disease caused by smoking. But smoking and vaping can have devastating effects on the body's ability to protect itself from repeated, serious respiratory infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia.

Cilia are microscopic, hair-like projects on cells that line the respiratory, reproductive, and digestive systems. Cilia in the respiratory system line most of your airways, where they have the job of trapping and removing dust, germs, and other foreign particles before they can make you sick. Cilia secrete mucus that traps particles, and they move in a continuous wave-like motion that sweeps the mucus and particles upward toward the throat, where they can be expelled from the body. When you are sick and cough up phlegm, that's what you are doing.

Smoking prevents cilia from performing these important functions. Chemicals in tobacco smoke paralyze the cilia so they can't sweep mucus out of the airways. Those chemicals also inhibit the cilia from producing mucus. Fortunately, these effects start to wear off soon after the most recent exposure to tobacco smoke. If you stop smoking, your cilia will return to normal. Even if prolonged smoking has destroyed cilia, they will regrow and resume functioning in a matter of months after you stop smoking.

4.4 Summary

- The plasma membrane is a structure that forms a barrier between the cytoplasm inside the cell and the environment outside the cell. It allows only certain substances to pass in or out of the cell.

- The plasma membrane is composed mainly of a bilayer of phospholipid molecules. It also contains other molecules, such as the steroid cholesterol, which helps the membrane keep its shape, and transport proteins, which help substances pass through the membrane.

- The plasma membranes of some cells have extensions that have other functions, like flagella to help sperm move, or cilia to help keep our airways clear.

4.4 Review Questions

- What are the general functions of the plasma membrane?

- Describe the phospholipid bilayer of the plasma membrane.

- Identify other molecules in the plasma membrane. State their functions.

- Why do some cells have plasma membrane extensions, like flagella and cilia?

- Explain why hydrophilic molecules cannot easily pass through the cell membrane. What type of molecule in the cell membrane might help hydrophilic molecules pass through it?

- Which part of a phospholipid molecule in the plasma membrane is made of fatty acid chains? Is this part hydrophobic or hydrophilic?

- The two layers of phospholipids in the plasma membrane are called a phospholipid ____________.

-

- Steroid hormones can pass directly through cell membranes. Why do you think this is the case?

- Some antibiotics work by making holes in the plasma membrane of bacterial cells. How do you think this kills the cells?

- What is the name of the long, whip-like extensions of the plasma membrane that helps some single-celled organisms move?

4.4 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAXnYcUjn5k&feature=emb_logo

Insights into cell membranes via dish detergent - Ethan Perlstein, TED-Ed, 2013.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBCVVszQQNs

Inside the cell membrane, by The Amoeba Sisters, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 4.4.1

Animal Cell Unannotated, by Kelvin Song on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en) public domain dedication license.

Figure 4.4.2

Jello mold at the mexican bakery photo by Aimée Knight on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 4.4.3

Phospholipid_Bilayer by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 4.4.4

Lipid bilayer by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 4.4.5

Spermatozoa-human-3140x by No specific author on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.4.6

Cilia/ Bronchiolar epithelium 3 - SEM by Charles Daghlian on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.4.7

Adverse effects of vaping (raster) by Mikael Häggström on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2018, February 27). Inside the cell membrane. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBCVVszQQNs&feature=youtu.be

Betts, J.G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E.. Womble, M., DeSaix. P. (2013, April 25). Figure 3.3 Phospolipid Bilayer [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/3-1-the-cell-membrane

Betts, J.G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E.. Womble, M., DeSaix. P. (2013, April 25). Figure 3.4 Cell Membrane [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/3-1-the-cell-membrane

Ghosh, A., Coakley, R. C., Mascenik, T., Rowell, T. R., Davis, E. S., Rogers, K., Webster, M. J., Dang, H., Herring, L. E., Sassano, M. F., Livraghi-Butrico, A., Van Buren, S. K., Graves, L. M., Herman, M. A., Randell, S. H., Alexis, N. E., & Tarran, R. (n.d.). Chronic E-Cigarette Exposure Alters the Human Bronchial Epithelial Proteome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical /Care Medicine, 198(1), 67–76. https://doi-org.ezproxy.tru.ca/10.1164/rccm.201710-2033OC

TED-Ed. (2013, February 26). Insights into cell membranes via dish detergent - Ethan Perlstein. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAXnYcUjn5k&feature=youtu.be

The principle holding that in a warm-blooded animal species having distinct geographic populations, the limbs, ears, and other appendages of the animals living in cold climates tend to be shorter than in animals of the same species living in warm climates.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Of Peas and People

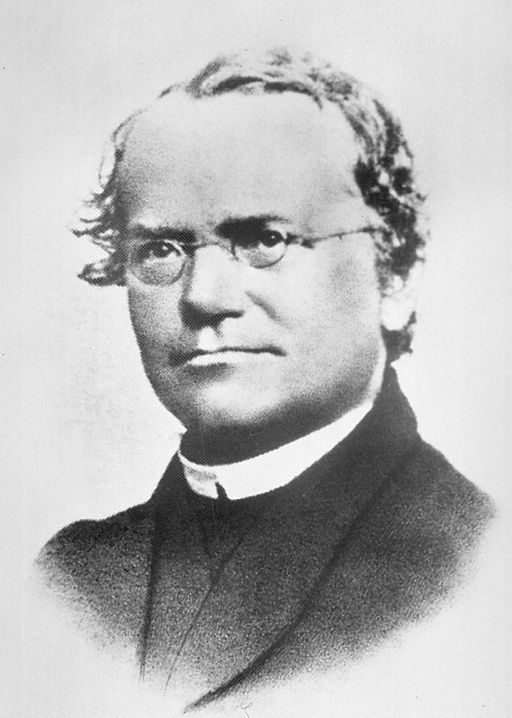

These purple-flowered plants are not just pretty to look at. Plants like these led to a huge leap forward in biology. They're common garden peas, and they were studied in the mid-1800s by an Austrian monk named Gregor Mendel. Through careful experimentation, Mendel uncovered the secrets of heredity, or how parents pass characteristics to their offspring. You may not care much about heredity in pea plants, but you probably care about your own heredity. Mendel's discoveries apply to people, as well as to peas — and to all other living things that reproduce sexually. In this concept, you will read about Mendel's experiments and the secrets of heredity that he discovered.

Mendel and His Pea Plants

Gregor Mendel (Figure 5.10.2) was born in 1822. He grew up on his parents’ farm in Austria. He did well in school and became a friar (and later an abbot) at St. Thomas' Abbey. Through sponsorship from the monastery, he went on to the University of Vienna, where he studied science and math. His professors encouraged him to learn science through experimentation, and to use math to make sense of his results. Mendel is best known for his experiments with pea plants (like the purple flower pictured in Figure 5.10.1).

Blending Theory of Inheritance

During Mendel's time, the blending theory of inheritance was popular. According to this theory, offspring have a blend (or mix) of their parents' characteristics. Mendel, however, noticed plants in his own garden that weren’t a blend of the parents. For example, a tall plant and a short plant had offspring that were either tall or short — not medium in height. Observations such as these led Mendel to question the blending theory. He wondered if there was a different underlying principle that could explain how characteristics are inherited. He decided to experiment with pea plants to find out. In fact, Mendel experimented with almost 30 thousand pea plants over the next several years!

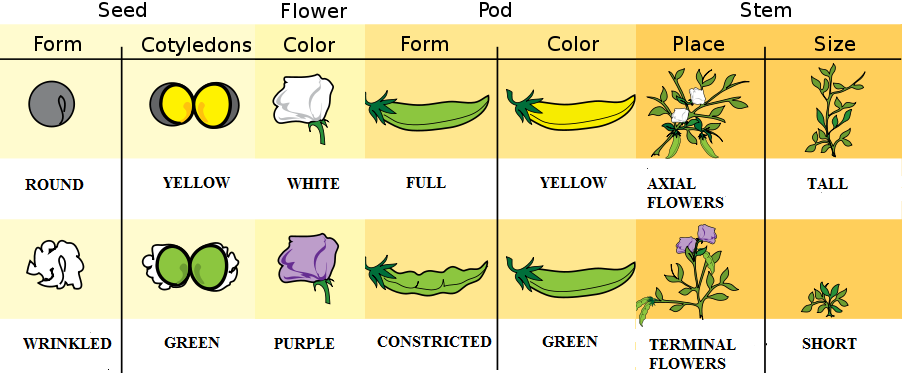

Why Study Pea Plants?

Why did Mendel choose common, garden-variety pea plants for his experiments? Pea plants are a good choice because they are fast-growing and easy to raise. They also have several visible characteristics that can vary. These characteristics — some of which are illustrated in Figure 5.10.4 — include seed form and colour, flower colour, pod form and colour, placement of pods and flowers on stems, and stem length. Each of these characteristics has two common values. For example, seed form may be round or wrinkled, and flower colour may be white or purple (violet).

Controlling Pollination

To research how characteristics are passed from parents to offspring, Mendel needed to control pollination, which is the fertilization step in the sexual reproduction of plants. Pollen consists of tiny grains that are the male sex cells (or gametes) of plants. They are produced by a male flower part called the anther. Pollination occurs when pollen is transferred from the anther to the stigma of the same or another flower. The stigma is a female part of a flower, and it passes pollen grains to female gametes in the ovary.

Pea plants are naturally self-pollinating. In self-pollination, pollen grains from anthers on one plant are transferred to stigmas of flowers on the same plant. Mendel was interested in the offspring of two different parent plants, so he had to prevent self-pollination. He removed the anthers from the flowers of some of the plants in his experiments. Then he pollinated them by hand using a small paintbrush with pollen from other parent plants of his choice.

When pollen from one plant fertilizes another plant of the same species, it is called cross-pollination. The offspring that result from such a cross are called hybrids. When the term hybrid is used in this context, it refers to any offspring resulting from the breeding of two genetically distinct individuals.

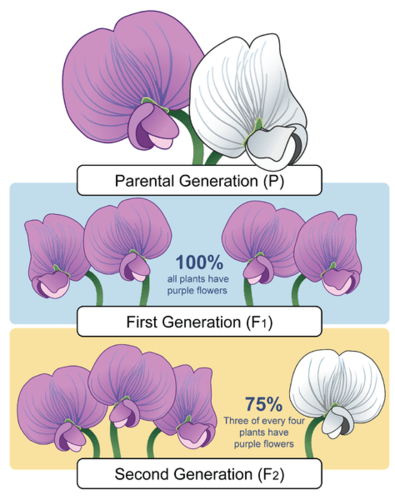

Mendel's First Set of Experiments

At first, Mendel experimented with just one characteristic at a time. He began with flower colour. As shown in Figure 5.10.5, Mendel cross-pollinated purple- and white-flowered parent plants. The parent plants in the experiments are referred to as the P (for parent) generation.

Figure 5.10.5 shows Mendel's first experiment with pea plants. The F1 generation results from the cross-pollination of two parent (P) plants, and it contains all purple flowers. The F2 generation results from the self-pollination of F1 plants, and contains 75% purple flowers and 25% white flowers.

F1 and F2 Generations

The offspring of the P generation are called the F1 (for filial, or “offspring”) generation. As shown in Figure 5.10.5, all of the plants in the F1 generation had purple flowers — none of them had white flowers. Mendel wondered what had happened to the white-flower characteristic. He assumed that some type of inherited factor produces white flowers and some other inherited factor produces purple flowers. Did the white-flower factor just disappear in the F1 generation? If so, then the offspring of the F1 generation — called the F2 generation — should all have purple flowers like their parents.

To test this prediction, Mendel allowed the F1 generation plants to self-pollinate. He was surprised by the results. Some of the F2 generation plants had white flowers. He studied hundreds of F2 generation plants, and for every three purple-flowered plants, there was an average of one white-flowered plant.

Law of Segregation

Mendel did the same experiment for all seven characteristics. In each case, one value of the characteristic disappeared in the F1 plants, later showing up again in the F2 plants. In each case, 75 per cent of F2 plants had one value of the characteristic, while 25 per cent had the other value. Based on these observations, Mendel formulated his first law of inheritance. This law is called the law of segregation. It states that there are two factors controlling a given characteristic, one of which dominates the other, and these factors separate and go to different gametes when a parent reproduces.

Mendel's Second Set of Experiments

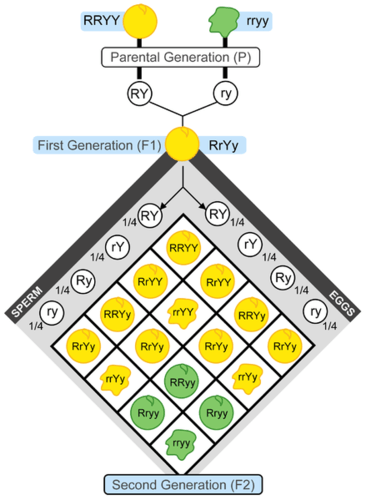

Mendel wondered whether different characteristics are inherited together. For example, are purple flowers and tall stems always inherited together, or do these two characteristics show up in different combinations in offspring? To answer these questions, Mendel next investigated two characteristics at a time. For example, he crossed plants with yellow round seeds and plants with green wrinkled seeds. The results of this cross are shown in Figure 5.10.6.

Figure 5.10.6 shows the outcome of a cross between plants that differ in seed colour (yellow or green) and seed form (shown here with a smooth round appearance or wrinkled appearance). The letters R, r, Y, and y represent genes for the characteristics Mendel was studying. Mendel didn’t know about genes, however, because genes would not be discovered until several decades later. This experiment demonstrates that, in the F2 generation, nine out of 16 were round yellow seeds, three out of 16 were wrinkled yellow seeds, three out of 16 were round green seeds, and one out of 16 was wrinkled green seeds.

F1 and F2 Generations

In this set of experiments, Mendel observed that plants in the F1 generation were all alike. All of them had yellow round seeds like one of the two parents. When the F1 generation plants self-pollinated, however, their offspring — the F2 generation — showed all possible combinations of the two characteristics. Some had green round seeds, for example, and some had yellow wrinkled seeds. These combinations of characteristics were not present in the F1 or P generations.

Law of Independent Assortment

Mendel repeated this experiment with other combinations of characteristics, such as flower colour and stem length. Each time, the results were the same as those shown in Figure 5.10.6. The results of Mendel's second set of experiments led to his second law. This is the law of independent assortment. It states that factors controlling different characteristics are inherited independently of each other.

Mendel's Legacy

You might think that Mendel's discoveries would have made a big impact on science as soon as he made them, but you would be wrong. Why? Because Mendel's work was largely ignored. Mendel was far ahead of his time, and he was working from a remote monastery. He had no reputation in the scientific community and had only published sparingly in the past. Additionally, he published this research in an obscure scientific journal. As a result, when Charles Darwin published his landmark book on evolution in 1869, although Mendel's work had been published just a few years earlier, Darwin was unaware of it. Consequently, Darwin knew nothing about Mendel's laws, and didn’t understand heredity. This made Darwin's arguments about evolution less convincing to many.

Then, in 1900, three different European scientists — Hugo de DeVries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak — arrived independently at Mendel's laws. All three had done experiments similar to Mendel's and come to the same conclusions that he had drawn several decades earlier. Only then was Mendel's work rediscovered, so that Mendel himself could be given the credit he was due. Although Mendel knew nothing about genes, which were discovered after his death, he is now considered the father of genetics.

5.10 Cultural Connection

Corn is the world's most produced crop. Canada produces 13,000-14,000 metric Kilo tonnes of corn annually, mostly in fields in Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba. Approximately 1.5 million hectares are devoted to this crop which is critically important for both humans and livestock as a food source. Despite these high numbers of output, Canada is still only 11th on the list of world corn producers, with USA, China and Brazil claiming the top three places. How did corn become such an important part of modern agriculture?

We didn't always have corn as we know it. Modern corn is descended from a type of grass called teosinte (Figure 5.10.7) native to Mesoamerica (southern part of North America). It is estimated that Indigenous people have been harvesting corn and corn ancestors for over 9000 years. Excavations of the Xihuatoxtla Shelter in southwestern Mexico revealed our earliest evidence of domesticated corn: maize remains on tools dating back 8,700 years.

Ancient Indigenous peoples of southern Mexico developed corn from grass plants using a process we now call selective breeding, also known as artificial selection. Teosinte doesn't resemble the corn we have today- it had only a few kernels individually encased on very hard shells, and yet today we have multiple varieties of corn with row upon row of bare kernels. This means that ancient agriculturalists among the Indigenous people of Mexico were intentionally cross-breeding strains of teosinte, and later, early maize to create plants which had more kernels, and reduced seed casings. Watch the TED Ed video in the Explore More section to see what other changes agriculturalists have made to modern-day corn.

5.10 Summary

- Mendel experimented with the inheritance of traits in pea plants at a time when the blending theory of inheritance was popular. This is the theory that offspring have a blend of the characteristics of their parents.

- Pea plants were good choices for this research, largely because they have several visible characteristics that exist in two different forms. By controlling pollination, Mendel was able to cross pea plants with different forms of the traits.

- In Mendel's first set of experiments, he experimented with just one characteristic at a time. The results of this set of experiments led to Mendel's first law of inheritance, called the law of segregation. This law states that there are two factors controlling a given characteristic, one of which dominates the other, and these factors separate and go to different gametes when a parent reproduces.

- In Mendel's second set of experiments, he experimented with two characteristics at a time. The results of this set of experiments led to Mendel's second law of inheritance, called the law of independent assortment. This law states that the factors controlling different characteristics are inherited independently of each other.

- Mendel's work was largely ignored during his own lifetime. However, when other researchers arrived at the same laws in 1900, Mendel's work was rediscovered, and he was given the credit he was due. He is now considered the father of genetics.

5.10 Review Questions

- Why were pea plants a good choice for Mendel's experiments?

-

- How did the outcome of Mendel's second set of experiments lead to his second law?

- Discuss the development of Mendel's legacy.

- If Mendel’s law of independent assortment was not correct, and characteristics were always inherited together, what types of offspring do you think would have been produced by crossing plants with yellow round seeds and green wrinkled seeds? Explain your answer.

5.10 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mehz7tCxjSE&feature=emb_logo

How Mendel's pea plants helped us understand genetics - Hortensia Jiménez Díaz, TED-Ed, 2013.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogc367xyzfk&feature=emb_logo

10 Strange Hybrid Fruits, Junkyboss, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6teBcfKpik

The history of the world according to corn - Chris A. Kniesly, TED-Ed, 2019.

Attributions

Figure 5.10.1

Purple sweet pea flower by unknown on Yana Ray on publicdomainpictures.net is used under a CC0 1.0 public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en).

Figure 5.10.2

Gregor_Mendel by unknown from National Institutes of Health, Health & Human Services on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 5.10.3

Gregor Mendel in Lego by Alan on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 5.10.4

Mendels_peas by Mariana Ruiz [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en).

Figure 5.10.5

Mendel's first experiment with pea plants by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under ![]() • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

Figure 5.10.6

Mendel's Second Experiment by by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under ![]() • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

Figure 5.10.7

Maize-teosinte by John Doebley on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en) license.

References

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2016). Figure 5 Mendel's first experiment [digital image]. In CK-12 College Human Biology (Section 5.9) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-human-biology/section/5.9/

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2016). Figure 6 Mendel's second experiment [digital image]. In CK-12 College Human Biology (Section 5.9) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-human-biology/section/5.9/

Junkyboss. (2016, March 31). 10 Strange hybrid fruits. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ogc367xyzfk&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2013, March 12). How Mendel's pea plants helped us understand genetics - Hortensia Jiménez Díaz. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mehz7tCxjSE&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2019, November 26). The history of the world according to corn - Chris A. Kniesly. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6teBcfKpik&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 1). Carl Correns. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Carl_Correns&oldid=960172546

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 8). Charles Darwin. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charles_Darwin&oldid=966652322

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 9). Erich von Tschermak. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Erich_von_Tschermak&oldid=944695823

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 7). Hugo de Vries. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hugo_de_Vries&oldid=966513671