4.6 Cell Organelles

Ribosome Review

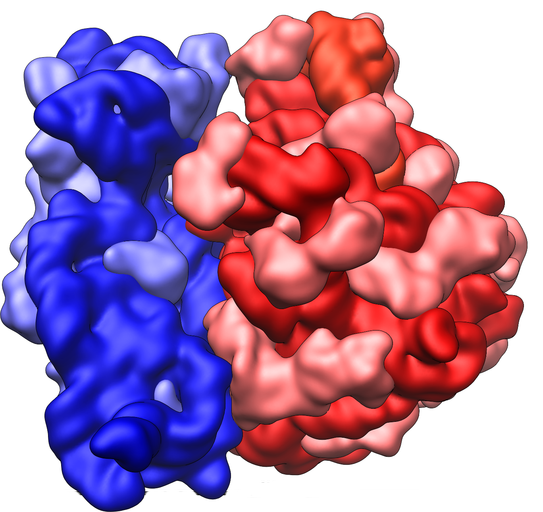

The 25-metre long sculpture shown in Figure 4.6.1 is a recognition of the beauty of one of the metabolic functions that takes place in the cells in your body. This artwork brings to life an important structure in living cells: the ribosome, the cell structure where proteins are synthesized. The slender silver strand is the messenger RNA(mRNA) bringing the code for a protein out into the cytoplasm. The purple and green structures are ribosomal subunits (which together form a single ribosome), which can “read” the code on the mRNA and direct the bonding of the correct sequence of amino acids to create a protein. All living cells — whether they are prokaryotic or eukaryotic — contain ribosomes, but only eukaryotic cells also contain a nucleus and several other types of organelles.

What Are Organelles?

An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell that is enclosed within a membrane and performs a specific job. Organelles are involved in many vital cell functions. Organelles in animal cells include the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, vesicles, and vacuoles. Ribosomes are not enclosed within a membrane, but they are still commonly referred to as organelles in eukaryotic cells.

The Nucleus

The nucleus is the largest organelle in a eukaryotic cell, and it’s considered the cell’s control center. It contains most of the cell’s DNA(which makes up chromosomes), and it is encoded with the genetic instructions for making proteins. The function of the nucleus is to regulate gene expression, including controlling which proteins the cell makes. In addition to DNA, the nucleus contains a thick liquid called nucleoplasm, which is similar in composition to the cytosol found in the cytoplasm outside the nucleus. Most eukaryotic cells contain just a single nucleus, but some types of cells (such as red blood cells) contain no nucleus and a few other types of cells (such as muscle cells) contain multiple nuclei.

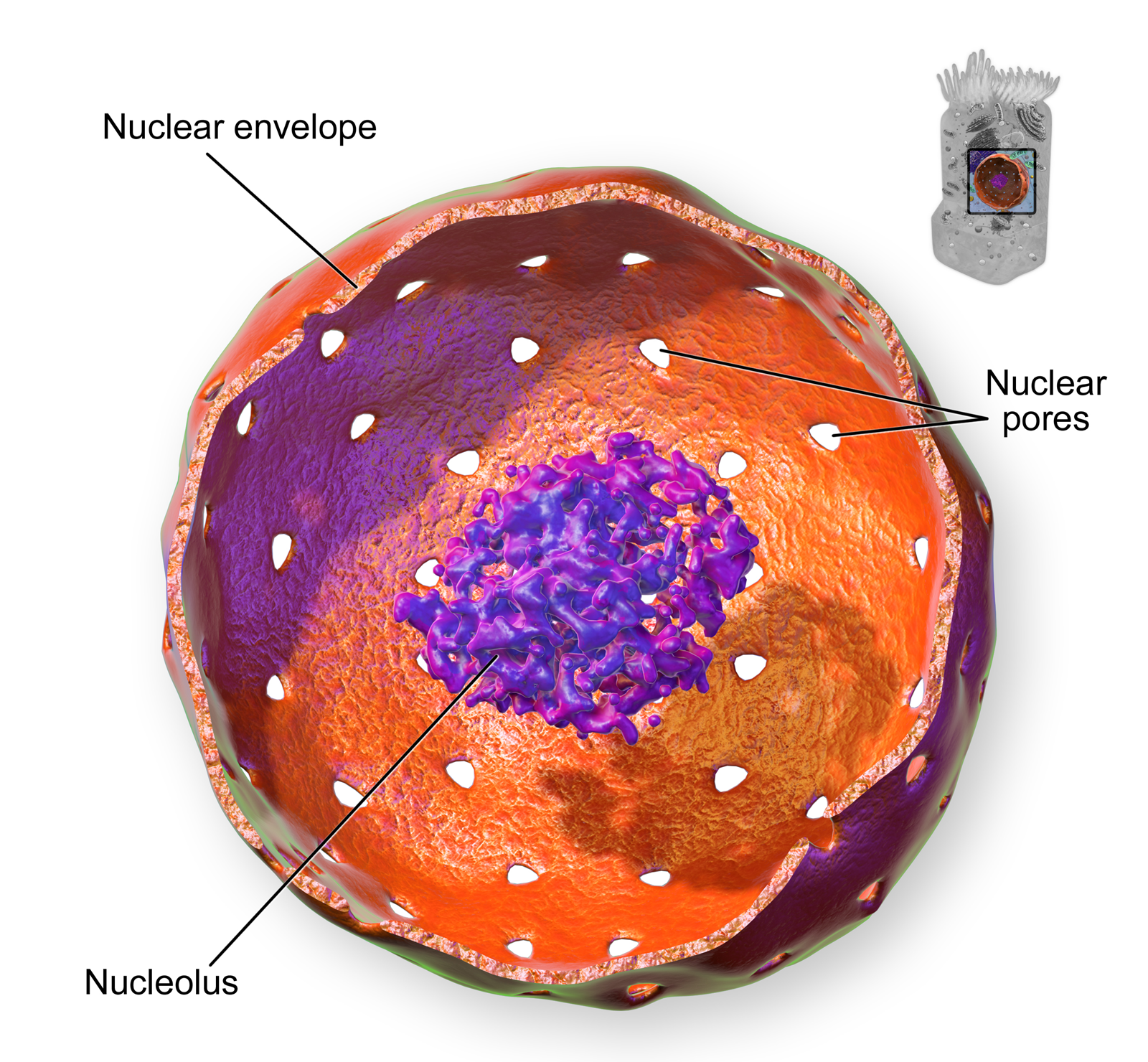

As you can see in the model pictured in Figure 4.6.2, the membrane enclosing the nucleus is called the nuclear envelope. This is actually a double membrane that encloses the entire organelle and isolates its contents from the cellular cytoplasm. Tiny holes called nuclear pores allow large molecules to pass through the nuclear envelope, with the help of special proteins. Large proteins and RNA molecules must be able to pass through the nuclear envelope so proteins can be synthesized in the cytoplasm and the genetic material can be maintained inside the nucleus. The nucleolus shown in the model below is mainly involved in the assembly of ribosomes. After being produced in the nucleolus, ribosomes are exported to the cytoplasm, where they are involved in the synthesis of proteins.

Mitochondria

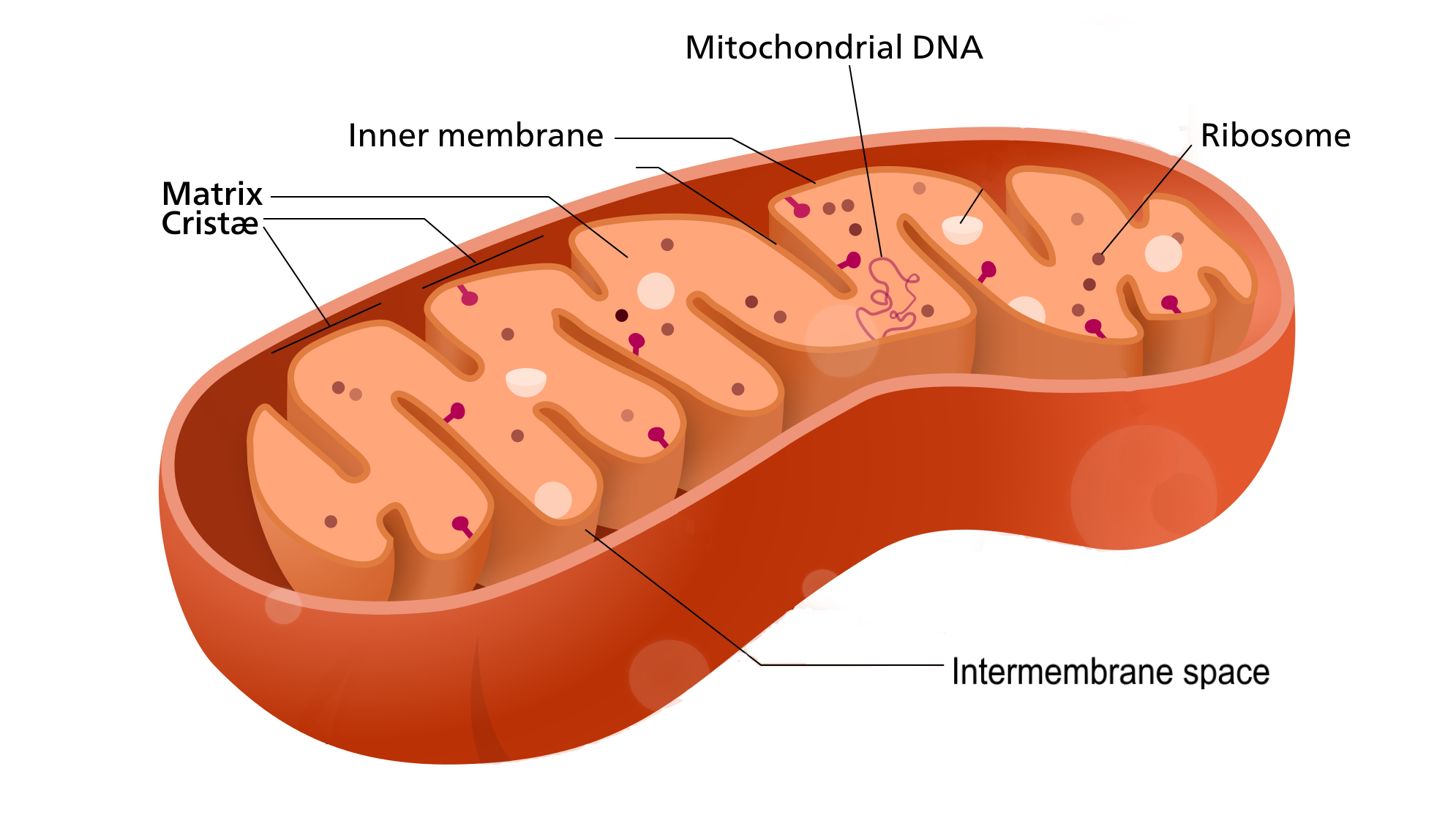

The mitochondrion (plural, mitochondria) is an organelle that makes energy available to the cell. This is why mitochondria are sometimes referred to as the “power plants of the cell.” They use energy from organic compounds (such as glucose) to make molecules of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), an energy-carrying molecule that is used almost universally inside cells for energy.

Mitochondria (as in the Figure 4.6.3 diagram) have a complex structure including an inner and out membrane. In addition, mitochondria have their own DNA, ribosomes, and a version of cytoplasm, called matrix. Does this sound similar to the requirements to be considered a cell? That’s because they are!

Scientists think that mitochondria were once free-living organisms because they contain their own DNA. They theorize that ancient prokaryotes infected (or were engulfed by) larger prokaryotic cells, and the two organisms evolved a symbiotic relationship that benefited both of them. The larger cells provided the smaller prokaryotes with a place to live. In return, the larger cells got extra energy from the smaller prokaryotes. Eventually, the smaller prokaryotes became permanent guests of the larger cells, as organelles inside them. This theory is called endosymbiotic theory, and it is widely accepted by biologists today. (See the video in section 4.3 to learn all about endosymbiotic theory.)

Endoplasmic Reticulum

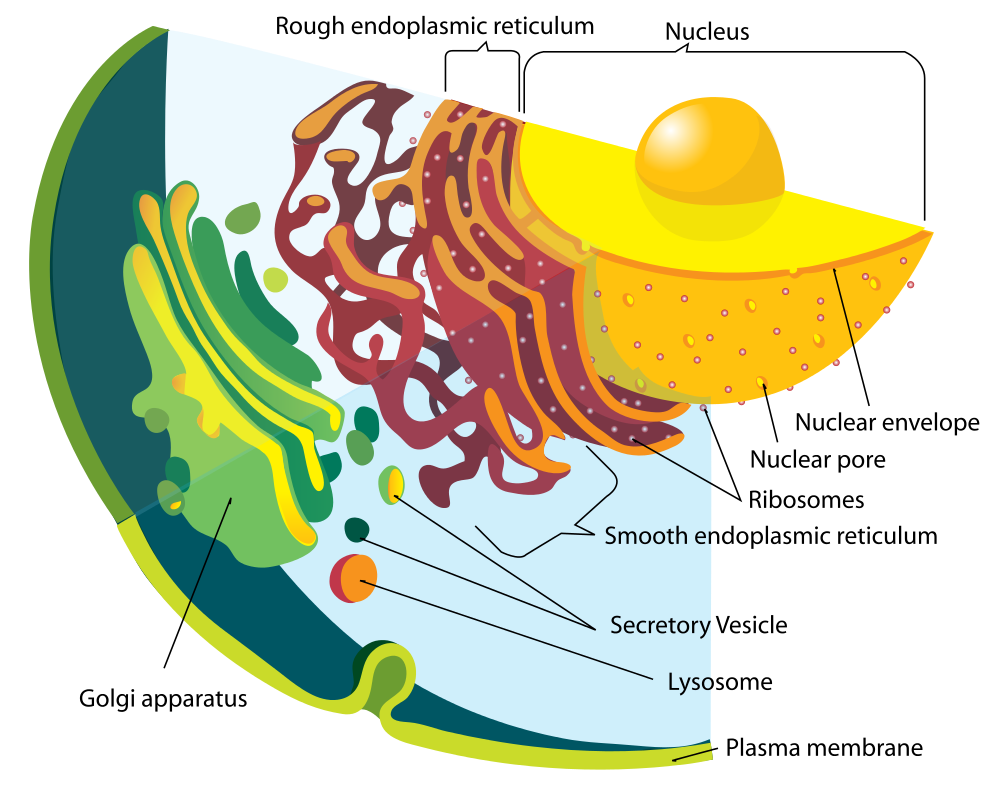

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that helps make and transport proteins and lipids. There are two types of endoplasmic reticulum: rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER). Both types are shown in Figure 4.6.4.

- rER looks rough because it is studded with ribosomes. It provides a framework for the ribosomes, which make proteins. Bits of its membrane pinch off to form tiny sacs called vesicles, which carry proteins away from the ER.

- sER looks smooth because it does not have ribosomes. sER makes lipids, stores substances, and plays other roles.

The Figure 4.6.4 drawing includes the nucleus, rER, sER, and Golgi apparatus. From the drawing, you can see how all these organelles work together to make and transport proteins.

Golgi Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (shown in the Figure 4.6.4 diagram) is a large organelle that processes proteins and prepares them for use both inside and outside the cell. You can see the Golgi apparatus in the figure above. The Golgi apparatus is something like a post office. It receives items (proteins from the ER), then packages and labels them before sending them on to their destinations (to different parts of the cell or to the cell membrane for transport out of the cell). The Golgi apparatus is also involved in the transport of lipids around the cell.

Vesicles and Vacuoles

Both vesicles and vacuoles are sac-like organelles made of phospholipid bilayer that store and transport materials in the cell. Vesicles are much smaller than vacuoles and have a variety of functions. The vesicles that pinch off from the membranes of the ER and Golgi apparatus store and transport protein and lipid molecules. You can see an example of this type of transport vesicle in the Figure 4.6.4. Some vesicles are used as chambers for biochemical reactions.

There are some vesicles which are specialized to carry out specific functions. Lysosomes, which use enzymes to break down foreign matter and dead cells, have a double membrane to make sure their contents don’t leak into the rest of the cell. Peroxisomes are another type of specialized vesicle with the main function of breaking down fatty acids and some toxins.

Centrioles

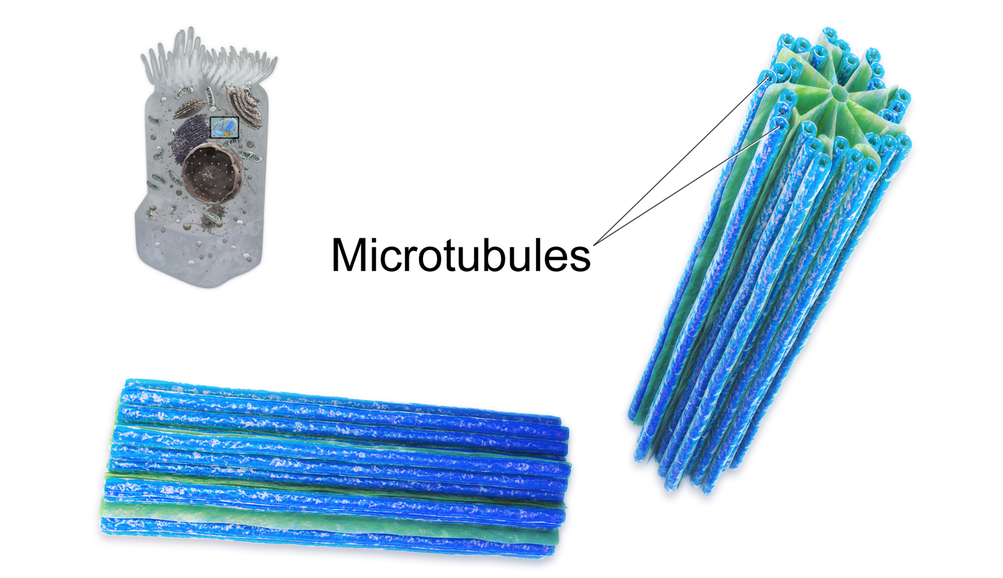

Centrioles are organelles involved in cell division. The function of centrioles is to help organize the chromosomes before cell division occurs so that each daughter cell has the correct number of chromosomes after the cell divides. Centrioles are found only in animal cells, and are located near the nucleus. Each centriole is made mainly of a protein named tubulin. The centriole is cylindrical in shape and consists of many microtubules, as shown in the model pictured in Figure 4.6.5.

Ribosomes

Ribosomes are small structures where proteins are made. Although they are not enclosed within a membrane, they are frequently considered organelles. Each ribosome is formed of two subunits, like the ones pictured at the beginning of this section (Figure 4.6.1) and in Figure 4.6.6. Both subunits consist of proteins and RNA. mRNA from the nucleus carries the genetic code, copied from DNA, which remains in the nucleus. At the ribosome, the genetic code in mRNA is used to assemble and join together amino acids to make proteins. Ribosomes can be found alone or in groups within the cytoplasm, as well as on the rER.

4.6 Summary

- An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell that is enclosed within a membrane and performs a specific job. Although ribosomes are not enclosed within a membrane, they are still commonly referred to as organelles in eukaryotic cells.

- The nucleus is the largest organelle in a eukaryotic cell, and it is considered to be the cell’s control center. It controls gene expression, including controlling which proteins the cell makes.

- The mitochondrion (plural, mitochondria) is an organelle that makes energy available to the cells. It is like the power plant of the cell. According to the widely accepted endosymbiotic theory, mitochondria evolved from prokaryotic cells that were once free-living organisms that infected or were engulfed by larger prokaryotic cells.

- The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that helps make and transport proteins and lipids. Rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) is studded with ribosomes. Smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER) has no ribosomes.

- The Golgi apparatus is a large organelle that processes proteins and prepares them for use both inside and outside the cell. It is also involved in the transport of lipids around the cell.

- Both vesicles and vacuoles are sac-like organelles that may be used to store and transport materials in the cell or as chambers for biochemical reactions. Lysosomes and peroxisomes are special types of vesicles that break down foreign matter, dead cells, or poisons.

- Centrioles are organelles located near the nucleus that help organize the chromosomes before cell division so each daughter cell receives the correct number of chromosomes.

- Ribosomes are small structures where proteins are made. They are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. They may be found alone or in groups within the cytoplasm or on the rER.

4.6 Review Questions

- What is an organelle?

- Describe the structure and function of the nucleus.

- Explain how the nucleus, ribosomes, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus work together to make and transport proteins.

- Why are mitochondria referred to as the “power plants of the cell”?

- What roles are played by vesicles and vacuoles?

- Why do all cells need ribosomes — even prokaryotic cells that lack a nucleus and other cell organelles?

- Explain endosymbiotic theory as it relates to mitochondria. What is one piece of evidence that supports this theory?

-

4.6 Explore More

Biology: Cell Structure I Nucleus Medical Media, Nucleus Medical Media, 2015.

David Bolinsky: Visualizing the wonder of a living cell, TED, 2007.

Attributes

Figure 4.6.1

Ribosomes at Work by Pedrik on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 4.6.2

Nucleus by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.3

Mitochondrion_structure.svg by Kelvinsong; modified by Sowlos on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.4

Endomembrane_system_diagram_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.6.5

Centrioles by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.6

Ribosome_shape by Vossman on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

References

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Nucleus – Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Medicine/Medical_gallery_of_Blausen_Medical_2014

Blausen.com staff (2014). Centrioles – Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Medicine/Medical_gallery_of_Blausen_Medical_2014

Nucleus Medical Media. (2015, March 18). Biology: Cell structure I Nucleus Medical Media. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URUJD5NEXC8&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2007, July 24). David Bolinsky: Visualizing the wonder of a living cell. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Id2rZS59xSE&feature=youtu.be

A large complex of RNA and protein which acts as the site of RNA translation, building proteins from amino acids using messenger RNA as a template.

A class of biological molecule consisting of linked monomers of amino acids and which are the most versatile macromolecules in living systems and serve crucial functions in essentially all biological processes.

The smallest unit of life, consisting of at least a membrane, cytoplasm, and genetic material.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Communicating with Urine

Why do dogs pee on fire hydrants? Besides “having to go,” they are marking their territory with chemicals in their urine called pheromones. It’s a form of communication, in which they are “saying” with odors that the yard is theirs and other dogs should stay away. In addition to fire hydrants, dogs may urinate on fence posts, trees, car tires, and many other objects. Urination in dogs, as in people, is usually a voluntary process controlled by the brain. The process of forming urine — which occurs in the kidneys — occurs constantly, and is not under voluntary control. What happens to all the urine that forms in the kidneys? It passes from the kidneys through the other organs of the urinary system, starting with the ureters.

Ureters

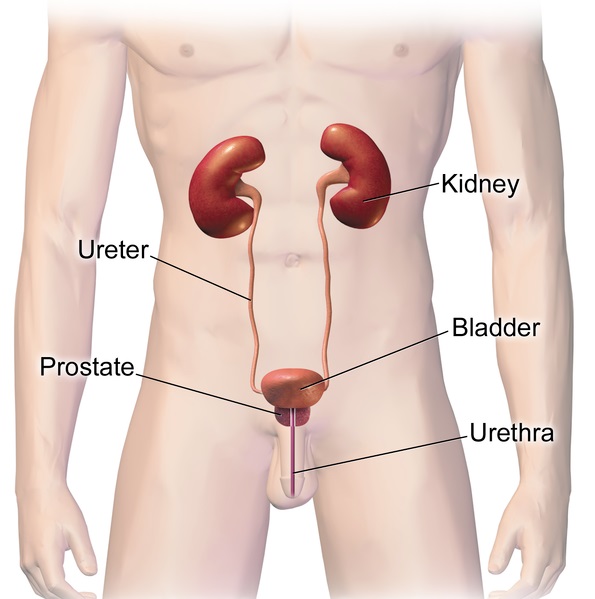

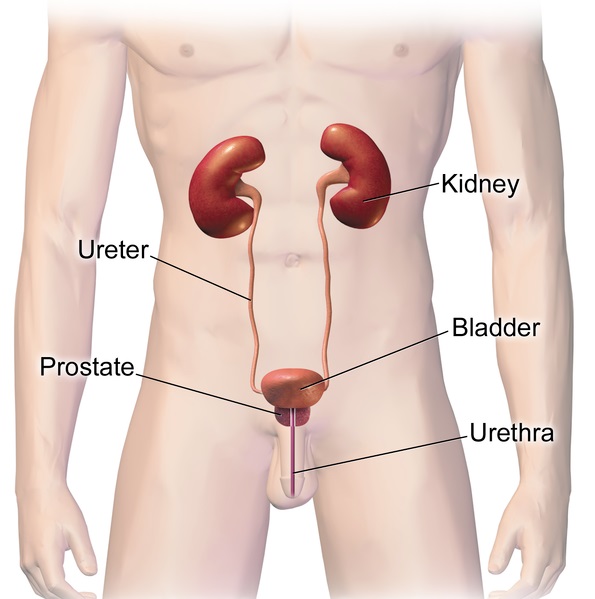

As shown in Figure 16.5.2, ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. They are paired structures, with one ureter for each kidney. In adults, ureters are between 25 and 30 cm (about 10–12 in) long and about 3 to 4 mm in diameter.

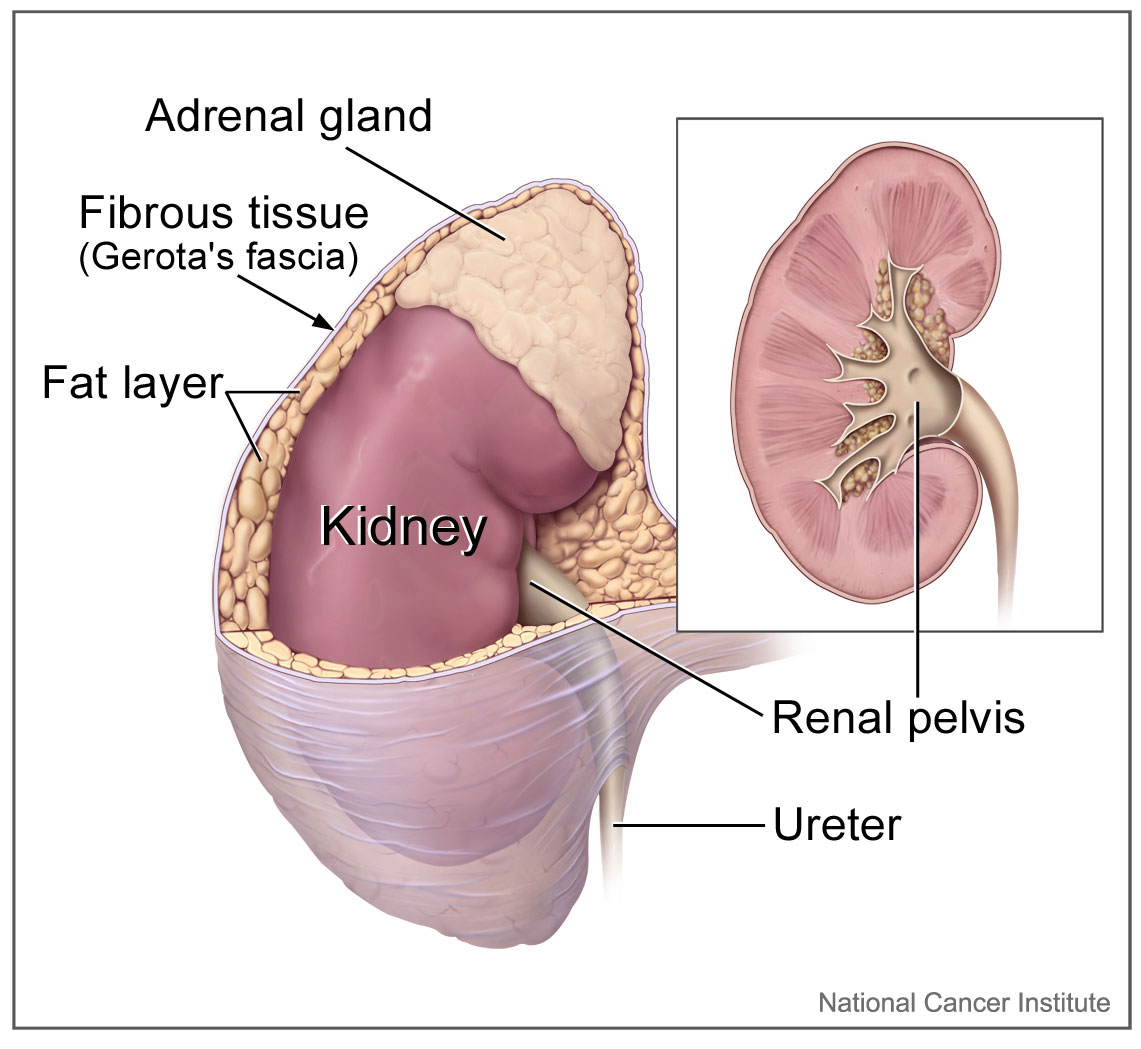

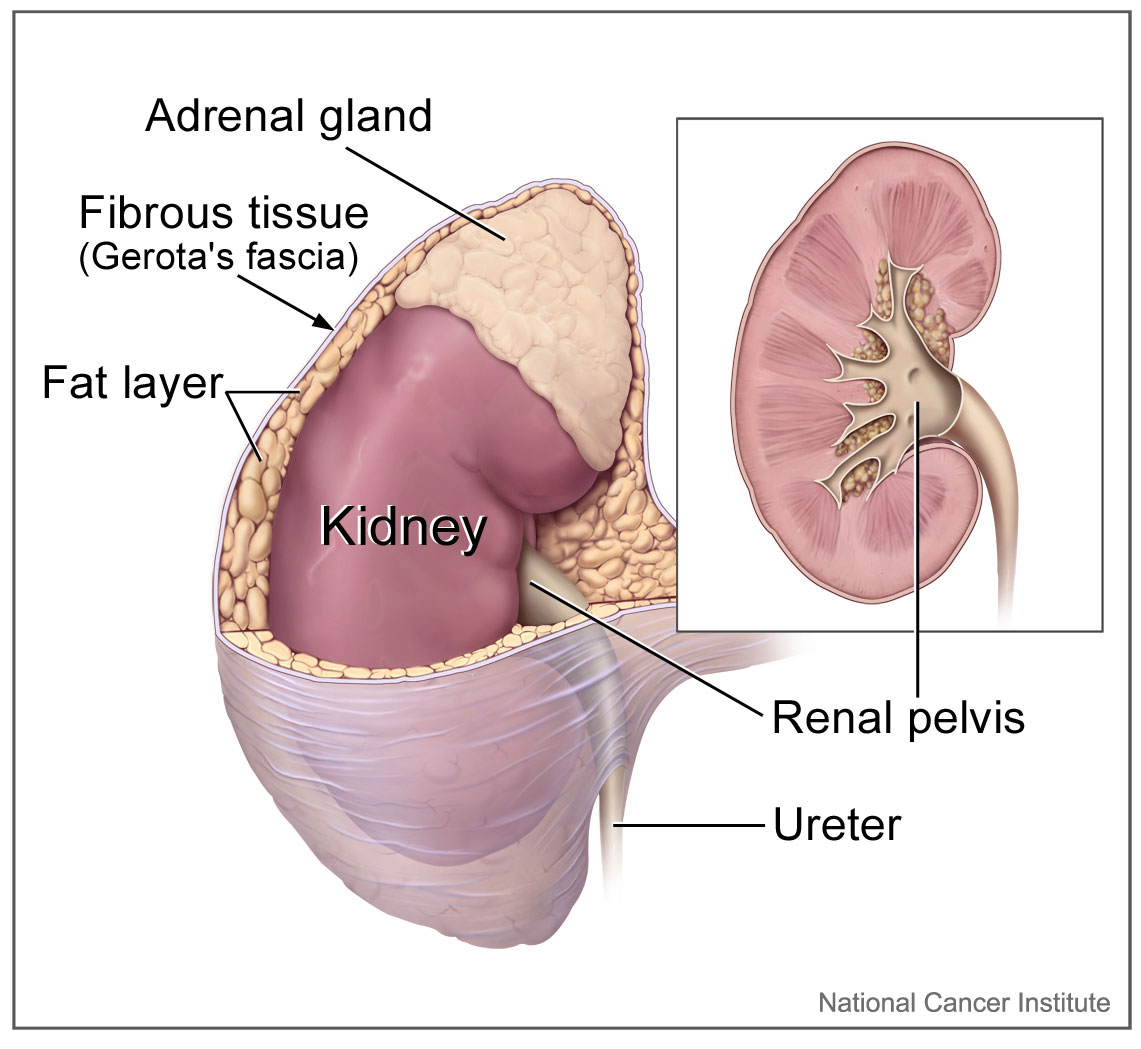

Each ureter arises in the pelvis of a kidney (the renal pelvis in Figure 16.5.3). It then passes down the side of the kidney, and finally enters the back of the bladder. At the entrance to the bladder, the ureters have sphincters that prevent the backflow of urine.

The walls of the ureters are composed of multiple layers of different types of tissues. The innermost layer is a special type of epithelium, called transitional epithelium. Unlike the epithelium lining most organs, transitional epithelium is capable of stretching and does not produce mucus. It lines much of the urinary system, including the renal pelvis, bladder, and much of the urethra, in addition to the ureters. Transitional epithelium allows these organs to stretch and expand as they fill with urine or allow urine to pass through. The next layer of the ureter walls is made up of loose connective tissue containing elastic fibres, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. After this layer are two layers of smooth muscles, an inner circular layer, and an outer longitudinal layer. The smooth muscle layers can contract in waves of peristalsis to propel urine down the ureters from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The outermost layer of the ureter walls consists of fibrous tissue.

Urinary Bladder

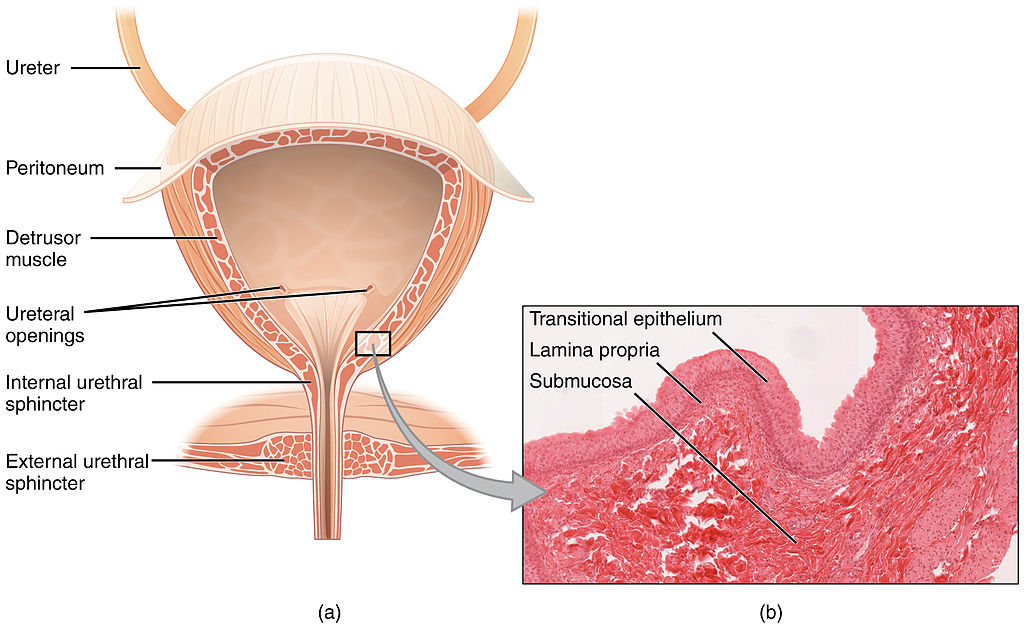

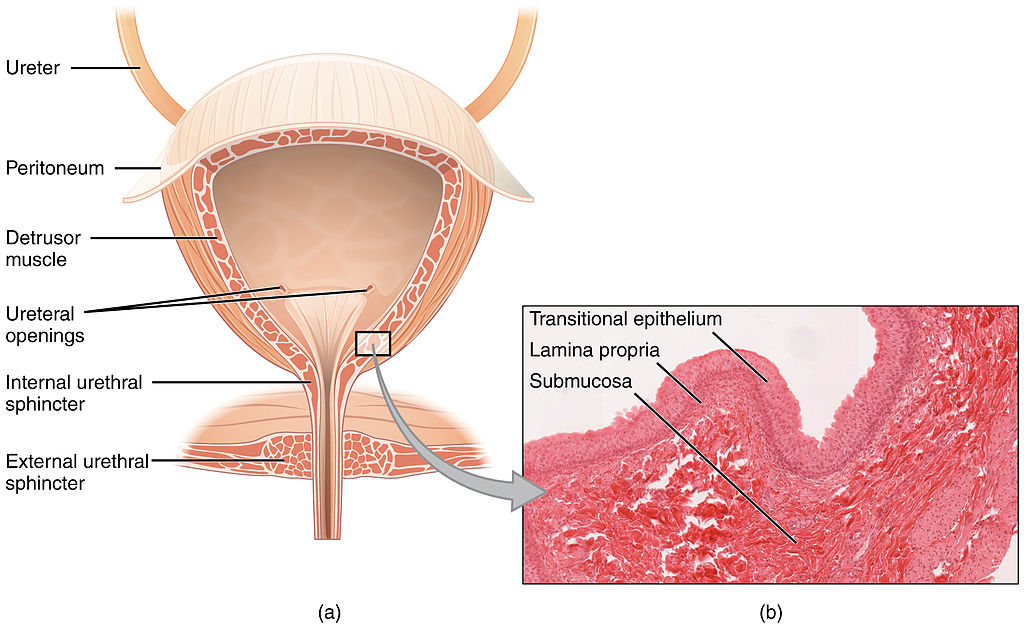

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It collects and stores urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. As shown in Figure 16.5.4, urine enters the urinary bladder from the ureters through two ureteral openings on either side of the back wall of the bladder. Urine leaves the bladder through a sphincter called the internal urethral sphincter. When the sphincter relaxes and opens, it allows urine to flow out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Like the ureters, the bladder is lined with transitional epithelium, which can flatten out and stretch as needed as the bladder fills with urine. The next layer (lamina propria) is a layer of loose connective tissue, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. This is followed by a submucosa layer, which connects the lining of the bladder with the detrusor muscle in the walls of the bladder. The outer covering of the bladder is peritoneum, which is a smooth layer of epithelial cells that lines the abdominal cavity and covers most abdominal organs.

The detrusor muscle in the wall of the bladder is made of smooth muscle fibres controlled by both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills, the detrusor muscle automatically relaxes to allow it to hold more urine. When the bladder is about half full, the stretching of the walls triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When the individual is ready to void, conscious nervous signals cause the detrusor muscle to contract, and the internal urethral sphincter to relax and open. As a result, urine is forcefully expelled out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Urethra

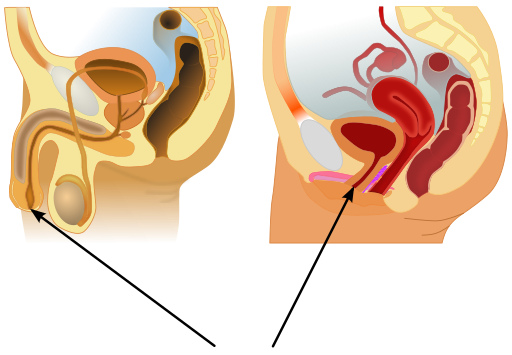

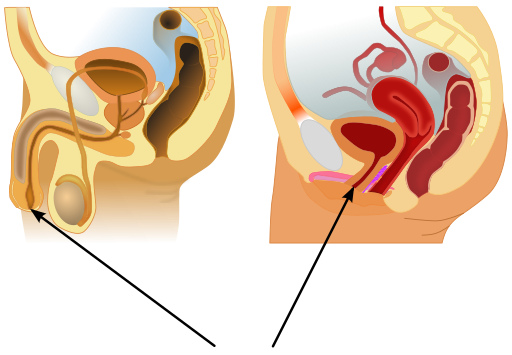

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice, which is the opening of the urethra on the surface of the body. As shown in Figure 16.5.5, the urethra in males travels through the penis, so it is much longer than the urethra in females. In males, the urethra averages about 20 cm (about 7.8 in) long, whereas in females, it averages only about 4.8 cm (about 1.9 in) long. In males, the urethra carries semen (as well as urine), but in females, it carries only urine. In addition, in males, the urethra passes through the prostate gland (part of the reproductive system) which is absent in women.

Like the ureters and bladder, the proximal (closer to the bladder) two-thirds of the urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The distal (farther from the bladder) third of the urethra is lined with mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucus helps protect the epithelium from urine, which is corrosive. Below the epithelium is loose connective tissue, and below that are layers of smooth muscle that are continuous with the muscle layers of the urinary bladder. When the bladder contracts to forcefully expel urine, the smooth muscle of the urethra relaxes to allow the urine to pass through.

In order for urine to leave the body through the external urethral orifice, the external urethral sphincter must relax and open. This sphincter is a striated muscle that is controlled by the somatic nervous system, so it is under conscious, voluntary control in most people (exceptions are infants, some elderly people, and patients with certain injuries or disorders). The muscle can be held in a contracted state and hold in the urine until the person is ready to urinate. Following urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra automatically contracts to re-establish muscle tone, and the individual consciously contracts the external urethral sphincter to close the external urethral opening.

16.5 Summary

- Ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. Each ureter arises at the renal pelvis of a kidney and travels down through the abdomen to the urinary bladder. The walls of the ureter contain smooth muscle that can contract to push urine through the ureter by peristalsis. The walls are lined with transitional epithelium that can expand and stretch.

- The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It is also lined with transitional epithelium. The function of the bladder is to collect and store urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. Filling of the bladder triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When a conscious decision to urinate is made, the detrusor muscle in the bladder wall contracts and forces urine out of the bladder and into the urethra.

- The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice. Somatic nerves control the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra. This allows the opening of the sphincter for urination to be under voluntary control.

16.5 Review Questions

- What are ureters? Describe the location of the ureters relative to other urinary tract organs.

- Identify layers in the walls of a ureter. How do they contribute to the ureter’s function?

- Describe the urinary bladder. What is the function of the urinary bladder?

-

- How does the nervous system control the urinary bladder?

- What is the urethra?

- How does the nervous system control urination?

- Identify the sphincters that are located along the pathway from the ureters to the external urethral orifice.

- What are two differences between the male and female urethra?

- When the bladder muscle contracts, the smooth muscle in the walls of the urethra _________ .

16.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/2Brajdazp1o

The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter, TED. 2016.

https://youtu.be/dg4_deyHLvQ

What Happens When You Hold Your Pee? SciShow, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 16.5.1

Cliche by Jackie on Wikimedia Common s is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 16.5.2

Urinary System Male by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.5.3

Adrenal glands on Kidney by NCI Public Domain by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) /National Cancer Institute (photo ID 4355) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.5.4

2605_The_Bladder by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license. (Micrograph originally provided by the Regents of the University of Michigan Medical School © 2012.)

Figure 16.5.5

512px-Male_and_female_urethral_openings.svg by andrybak (derivative work) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. (Original: Male anatomy blank.svg: alt.sex FAQ, derivative work: Tsaitgaist Female anatomy with g-spot.svg: Tsaitgaist.)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.4 Bladder (a) Anterior cross section of the bladder. (b) The detrusor muscle of the bladder (source: monkey tissue) LM × 448 [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 7.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-2-gross-anatomy-of-urine-transport

SciShow. (2016, January 22). What happens when you hold your pee? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dg4_deyHLvQ&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2016, September 2). The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Brajdazp1o&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Communicating with Urine

Why do dogs pee on fire hydrants? Besides “having to go,” they are marking their territory with chemicals in their urine called pheromones. It’s a form of communication, in which they are “saying” with odors that the yard is theirs and other dogs should stay away. In addition to fire hydrants, dogs may urinate on fence posts, trees, car tires, and many other objects. Urination in dogs, as in people, is usually a voluntary process controlled by the brain. The process of forming urine — which occurs in the kidneys — occurs constantly, and is not under voluntary control. What happens to all the urine that forms in the kidneys? It passes from the kidneys through the other organs of the urinary system, starting with the ureters.

Ureters

As shown in Figure 16.5.2, ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. They are paired structures, with one ureter for each kidney. In adults, ureters are between 25 and 30 cm (about 10–12 in) long and about 3 to 4 mm in diameter.

Each ureter arises in the pelvis of a kidney (the renal pelvis in Figure 16.5.3). It then passes down the side of the kidney, and finally enters the back of the bladder. At the entrance to the bladder, the ureters have sphincters that prevent the backflow of urine.

The walls of the ureters are composed of multiple layers of different types of tissues. The innermost layer is a special type of epithelium, called transitional epithelium. Unlike the epithelium lining most organs, transitional epithelium is capable of stretching and does not produce mucus. It lines much of the urinary system, including the renal pelvis, bladder, and much of the urethra, in addition to the ureters. Transitional epithelium allows these organs to stretch and expand as they fill with urine or allow urine to pass through. The next layer of the ureter walls is made up of loose connective tissue containing elastic fibres, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. After this layer are two layers of smooth muscles, an inner circular layer, and an outer longitudinal layer. The smooth muscle layers can contract in waves of peristalsis to propel urine down the ureters from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The outermost layer of the ureter walls consists of fibrous tissue.

Urinary Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It collects and stores urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. As shown in Figure 16.5.4, urine enters the urinary bladder from the ureters through two ureteral openings on either side of the back wall of the bladder. Urine leaves the bladder through a sphincter called the internal urethral sphincter. When the sphincter relaxes and opens, it allows urine to flow out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Like the ureters, the bladder is lined with transitional epithelium, which can flatten out and stretch as needed as the bladder fills with urine. The next layer (lamina propria) is a layer of loose connective tissue, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. This is followed by a submucosa layer, which connects the lining of the bladder with the detrusor muscle in the walls of the bladder. The outer covering of the bladder is peritoneum, which is a smooth layer of epithelial cells that lines the abdominal cavity and covers most abdominal organs.

The detrusor muscle in the wall of the bladder is made of smooth muscle fibres controlled by both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills, the detrusor muscle automatically relaxes to allow it to hold more urine. When the bladder is about half full, the stretching of the walls triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When the individual is ready to void, conscious nervous signals cause the detrusor muscle to contract, and the internal urethral sphincter to relax and open. As a result, urine is forcefully expelled out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Urethra

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice, which is the opening of the urethra on the surface of the body. As shown in Figure 16.5.5, the urethra in males travels through the penis, so it is much longer than the urethra in females. In males, the urethra averages about 20 cm (about 7.8 in) long, whereas in females, it averages only about 4.8 cm (about 1.9 in) long. In males, the urethra carries semen (as well as urine), but in females, it carries only urine. In addition, in males, the urethra passes through the prostate gland (part of the reproductive system) which is absent in women.

Like the ureters and bladder, the proximal (closer to the bladder) two-thirds of the urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The distal (farther from the bladder) third of the urethra is lined with mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucus helps protect the epithelium from urine, which is corrosive. Below the epithelium is loose connective tissue, and below that are layers of smooth muscle that are continuous with the muscle layers of the urinary bladder. When the bladder contracts to forcefully expel urine, the smooth muscle of the urethra relaxes to allow the urine to pass through.

In order for urine to leave the body through the external urethral orifice, the external urethral sphincter must relax and open. This sphincter is a striated muscle that is controlled by the somatic nervous system, so it is under conscious, voluntary control in most people (exceptions are infants, some elderly people, and patients with certain injuries or disorders). The muscle can be held in a contracted state and hold in the urine until the person is ready to urinate. Following urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra automatically contracts to re-establish muscle tone, and the individual consciously contracts the external urethral sphincter to close the external urethral opening.

16.5 Summary

- Ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. Each ureter arises at the renal pelvis of a kidney and travels down through the abdomen to the urinary bladder. The walls of the ureter contain smooth muscle that can contract to push urine through the ureter by peristalsis. The walls are lined with transitional epithelium that can expand and stretch.

- The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It is also lined with transitional epithelium. The function of the bladder is to collect and store urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. Filling of the bladder triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When a conscious decision to urinate is made, the detrusor muscle in the bladder wall contracts and forces urine out of the bladder and into the urethra.

- The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice. Somatic nerves control the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra. This allows the opening of the sphincter for urination to be under voluntary control.

16.5 Review Questions

- What are ureters? Describe the location of the ureters relative to other urinary tract organs.

- Identify layers in the walls of a ureter. How do they contribute to the ureter’s function?

- Describe the urinary bladder. What is the function of the urinary bladder?

-

- How does the nervous system control the urinary bladder?

- What is the urethra?

- How does the nervous system control urination?

- Identify the sphincters that are located along the pathway from the ureters to the external urethral orifice.

- What are two differences between the male and female urethra?

- When the bladder muscle contracts, the smooth muscle in the walls of the urethra _________ .

16.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/2Brajdazp1o

The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter, TED. 2016.

https://youtu.be/dg4_deyHLvQ

What Happens When You Hold Your Pee? SciShow, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 16.5.1

Cliche by Jackie on Wikimedia Common s is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 16.5.2

Urinary System Male by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.5.3

Adrenal glands on Kidney by NCI Public Domain by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) /National Cancer Institute (photo ID 4355) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.5.4

2605_The_Bladder by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license. (Micrograph originally provided by the Regents of the University of Michigan Medical School © 2012.)

Figure 16.5.5

512px-Male_and_female_urethral_openings.svg by andrybak (derivative work) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. (Original: Male anatomy blank.svg: alt.sex FAQ, derivative work: Tsaitgaist Female anatomy with g-spot.svg: Tsaitgaist.)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.4 Bladder (a) Anterior cross section of the bladder. (b) The detrusor muscle of the bladder (source: monkey tissue) LM × 448 [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 7.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-2-gross-anatomy-of-urine-transport

SciShow. (2016, January 22). What happens when you hold your pee? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dg4_deyHLvQ&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2016, September 2). The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Brajdazp1o&feature=youtu.be

A central organelle containing hereditary material.

A tiny cellular structure that performs specific functions within a cell.

The jellylike material that makes up much of a cell inside the cell membrane, and, in eukaryotic cells, surrounds the nucleus. The organelles of eukaryotic cells, such as mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum, and (in green plants) chloroplasts, are contained in the cytoplasm.

A double-membrane-bound organelle found in most eukaryotic organisms. Mitochondria convert oxygen and nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is the chemical energy "currency" of the cell that powers the cell's metabolic activities.

A network of membranous tubules within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell, continuous with the nuclear membrane. It often has ribosomes attached and is involved in protein and lipid synthesis.

A membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells made up of a series of flattened stacked pouches with the purpose of collecting and dispatching protein and lipid products received from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Also referred to as the Golgi complex or the Golgi body.

A structure within a cell, consisting of lipid bilayer. Vesicles form naturally during the processes of secretion, uptake and transport of materials within the plasma membrane.

A membrane-bound organelle which is present in all plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal and bacterial cells. It's function is storage of substances and to maintain the rigidity of plant cells.

A solution, similar to the cytoplasm of a cell, enveloped by the nuclear envelope and surrounding the chromosomes and nucleolus.

The aqueous component of the cytoplasm of a cell, within which various organelles and particles are suspended.

A structure made up of two lipid bilayer membranes which in eukaryotic cells surrounds the nucleus, which encases the genetic material. Also know as the nuclear membrane.

A protein-lined channel in the nuclear envelope that regulates the transportation of molecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

A structure in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells which is the site of ribosome synthesis/production.

The ability to do work.

Glucose (also called dextrose) is a simple sugar with the molecular formula C6H12O6. Glucose is the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight.

A complex organic chemical that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, e.g. muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, and chemical synthesis. Found in all forms of life, ATP is often referred to as the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer.

Any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms.

An evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms.

A substance that is insoluble in water. Examples include fats, oils and cholesterol. Lipids are made from monomers such as glycerol and fatty acids.

An organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Its main function is to produce proteins. It is a portion of the endoplasmic reticulum which is studded with attached ribosomes.

An organelle found in eukaryotic cells with the function of making cellular products such as hormones and lipids. The smooth endoplasmic reticulum is a part of the endoplasmic reticulum that does not have attached ribosomes.

The semipermeable membrane surrounding the cytoplasm of a cell.

A cylindrical organelle composed of microtubules located near the nucleus in animal cells, occurring in pairs and involved in the development of spindle fibers in cell division.

The process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle.

A threadlike structure of nucleic acids and protein found in the nucleus of most living cells, carrying genetic information in the form of genes.