4.12 Cell Cycle and Cell Division

So Many Cells!

This baby girl (Figure 4.12.1) has a lot of growing to do before she’s as big as her mom. Most of her growth will be the result of cell division. By the time she is an adult, her body will consist of trillions of cells. Cell division is just one of the stages that all cells go through during their life. This includes cells that are harmful, such as cancer cells. Cancer cells divide more often than normal cells, causing them to grow out of control. In fact, this is how cancer cells cause illness. In this concept, you will read about how cells divide, what other stages cells go through, and what causes cancer cells to divide out of control and harm the body.

The Cell Cycle

Cell division is just one of several stages that a cell goes through during its lifetime. The cell cycle is a repeating series of events that includes growth, DNA synthesis, and cell division. The cell cycle in prokaryotes is quite simple: the cell grows, its DNA replicates, and the cell divides. In eukaryotes, the cell cycle is more complicated.

Eukaryotic Cell Cycle

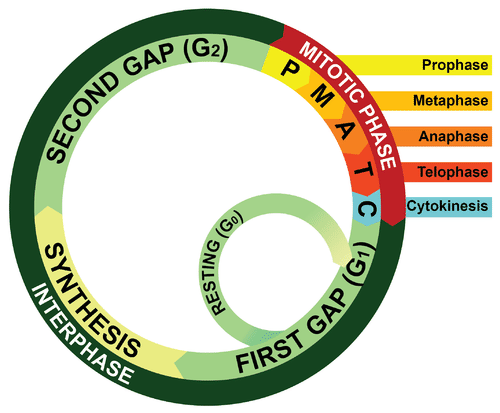

The diagram in Figure 4.12.2 represents the cell cycle of a eukaryotic cell. As you can see, the eukaryotic cell cycle has several phases. The mitotic phase (M) actually includes both mitosis and cytokinesis. This is when the nucleus and then the cytoplasm divide. The other three phases (G1, S, and G2) are generally grouped together as interphase. During interphase, the cell grows, performs routine life processes, and prepares to divide. These phases are discussed below.

Interphase

The interphase of the eukaryotic cell cycle can be subdivided into the three phases described below, which are represented in Figure 4.12.2.

- Growth Phase 1 (G1): During this phase, the cell grows rapidly, while performing routine metabolic processes. It also makes proteins needed for DNA replication and copies some of its organelles in preparation for cell division. A cell typically spends most of its life in this phase. This phase is also known as gap phase 1.

- Synthesis Phase (S): During this phase, the cell’s DNA is copied in the process of DNA replication, in order to prepare for the upcoming mitotic phase.

- Growth Phase 2 (G2): During this phase, the cell makes final preparations to divide. For example, it makes additional proteins and organelles. This phase is also known as gap phase 2.

Control of the Cell Cycle

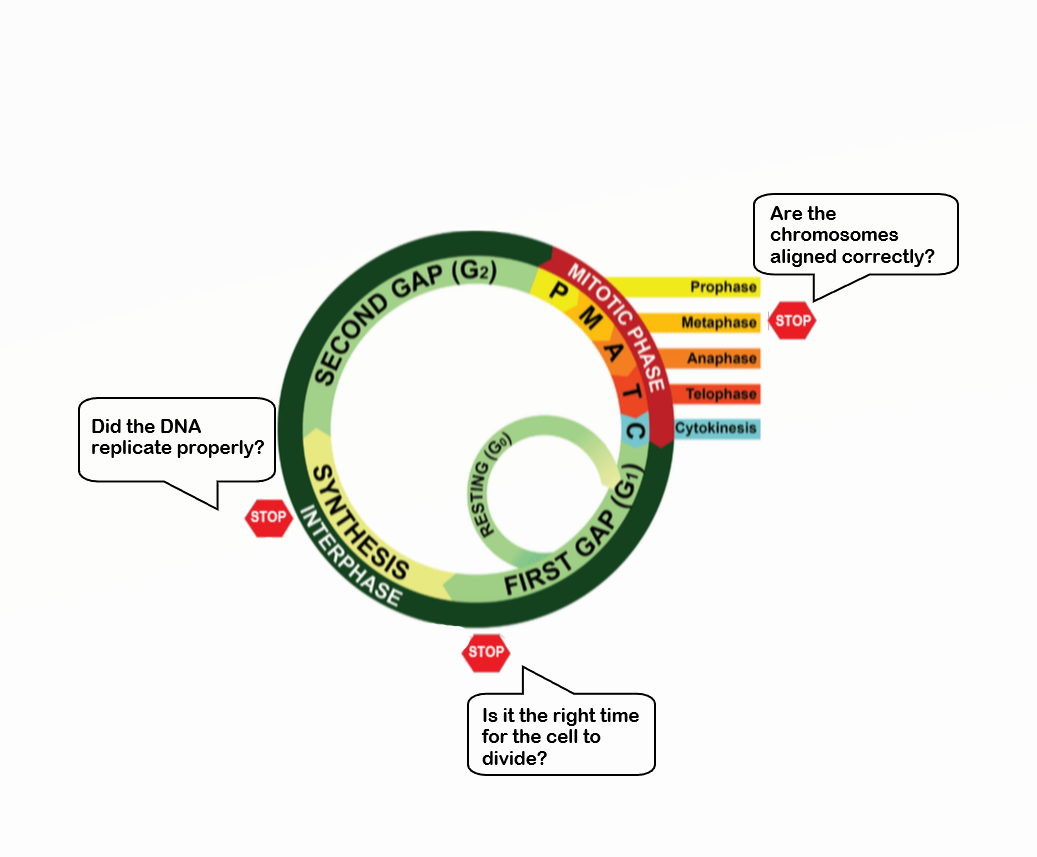

If the cell cycle occurred without regulation, cells might go from one phase to the next before they were ready. What controls the cell cycle? How does the cell know when to grow, synthesize DNA, and divide? The cell cycle is controlled mainly by regulatory proteins. These proteins control the cycle by signaling the cell to either start or delay the next phase of the cycle. They ensure that the cell completes the previous phase before moving on. Regulatory proteins control the cell cycle at key checkpoints, which are shown in Figure 4.12.3. There are a number of main checkpoints.

Checkpoints in the eukaryotic cell cycle ensure that the cell is ready to proceed before it moves on to the next phase of the cycle.

- The G1 checkpoint, just before entry into S phase, makes the key decision of whether the cell should divide.

- The S checkpoint determines if the DNA has been replicated properly.

- The mitosis checkpoint ensures that all the chromosomes are properly aligned before the cell is allowed to divide.

Cancer and the Cell Cycle

Cancer is a disease that occurs when the cell cycle is no longer regulated. This happens because a cell’s DNA becomes damaged. Damage can occur due to exposure to hazards, such as radiation or toxic chemicals. Cancerous cells generally divide much faster than normal cells. which may end up forming a mass of abnormal cells called a tumor (see Figure 4.12.4). The rapidly dividing cells take up nutrients and space that normal cells need. This can damage tissues and organs and eventually lead to death.

Cell Division

Cell division is the process in which one cell, called the parent cell, divides to form two new cells, referred to as daughter cells. How this happens depends on whether the cell is prokaryotic or eukaryotic. Cell division is simpler in prokaryotes than eukaryotes because prokaryotic cells themselves are simpler. Prokaryotic cells have a single circular chromosome, no nucleus, and few other organelles. Eukaryotic cells, in contrast, have multiple chromosomes contained within a nucleus and many other organelles. All of these cell parts must be duplicated and separated when the cell divides.

Before a eukaryotic cell divides, all of the DNA in the cell’s multiple chromosomes is replicated. Its organelles are also duplicated. Cell division occurs in two major steps, called mitosis and cytokinesis, both of which are described in greater detail in Chapter 5.

- The first step in the division of a eukaryotic cell is mitosis, a multi-phase process in which the nucleus of the cell divides. During mitosis, the nuclear envelope (membrane) breaks down and later reforms. The chromosomes are also sorted and separated to ensure that each daughter cell receives a complete set of chromosomes.

- The second major step is cytokinesis. This step, which also occurs in prokaryotic cells, is when the cytoplasm divides, forming two daughter cells.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

Henrietta Lacks sought treatment for her cancer at Johns Hopkins University Hospital at a time when researchers were trying to grow human cells in the lab for medical testing. Despite many attempts, the cells always died before they had undergone many cell divisions. Mrs. Lacks’s doctor, Howard Jones, took a small sample of cells from her tumor without her knowledge and gave them to a Johns Hopkins researcher, George Gey, who tried to grow them on a culture plate. For the first time in history, human cells grown on a culture plate kept dividing… and dividing and dividing and dividing. Copies of Henrietta’s cells — called HeLa cells, for her name (Henrietta Lacks) — are still alive today. In fact, there are currently billions of HeLa cells in laboratories around the world!

Why Henrietta’s cells lived on when other human cells did not is still something of a mystery, but they are clearly extremely hardy and resilient cells. By 1953, when researchers learned of their ability to keep dividing indefinitely, factories were set up to start producing the cells commercially on a large scale for medical research. Since then, HeLa cells have been used in thousands of studies and have made possible hundreds of medical advances. Jonas Salk, for example, used the cells in the early 1950s to test his polio vaccine. Over the decades since then, HeLa cells have been used to make important discoveries in the study of cancer, AIDS, and many other diseases. The cells were even sent to space on early space missions to learn how human cells respond to zero gravity. HeLa cells were also the first human cells ever cloned, and their genes were some of the first ever mapped. It is almost impossible to overestimate the profound importance of HeLa cells to human biology and medicine.

You would think that Henrietta’s name would be well known in medical history for her unparalleled contributions to biomedical research. However, until 2010, her story was virtually unknown. That year, a science writer named Rebecca Skloot published a nonfiction book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Based on a decade of research, this riveting account became an almost instantaneous best seller. As of 2016, Oprah Winfrey and collaborators planned to make a movie based on the book, and in recent years, numerous articles about Henrietta Lacks have appeared in the press.

Ironically, Henrietta herself never knew her cells had been taken, and neither did her family. While her cells were making a lot of money and building scientific careers, her children were living in poverty, too poor to afford medical insurance. The story of Henrietta Lacks and her immortal cells raises ethical issues about human tissues and who controls them in biomedical research. There is no question that Henrietta Lacks deserves far more recognition for her contribution to the advancement of science and medicine.

If you want to learn more about Henrietta Lacks and her immortal cells, read Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (or watch the movie, if it is available). You can also watch the short video below about Henrietta Lacks and her immortal cells by Robin Bulleri:

The immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks – Robin Bulleri, TED-Ed, 2016.

4.12 Summary

- The cell cycle is a repeating series of events that includes growth, DNA synthesis, and cell division. The cycle is more complicated in eukaryotic than prokaryotic cells.

- In a eukaryotic cell, the cell cycle has two major phases: mitotic phase and interphase. During mitotic phase, first the nucleus and then the cytoplasm divide. During interphase, the cell grows, performs routine life processes, and prepares to divide.

- The cell cycle is controlled mainly by regulatory proteins that signal the cell to either start or delay the next phase of the cycle. They ensure that the cell completes the previous phase before moving on. There are a number of main checkpoints in the regulation of the cell cycle.

- Cancer is a disease that occurs when the cell cycle is no longer regulated, often because the cell’s DNA has become damaged. Cancerous cells grow out of control and may form a mass of abnormal cells called a tumor.

- The cell division phase of the cell cycle in a eukaryotic cell occurs in two major steps: mitosis — when the nucleus divides — and cytokinesis, when the cytoplasm divides and two daughter cells form.

4.12 Review Questions

-

- Explain why cell division is more complex in eukaryotic than prokaryotic cells.

- Using a technique called flow cytometry, scientists can distinguish between cells with the normal amount of DNA and those that contain twice the normal amount of DNA as they go through the cell cycle. Which phases of the cell cycle will have cells with twice the amount of DNA? Explain your answer.

- What were scientists trying to do when they took tumor cells from Henrietta Lacks? Why did they specifically use tumor cells to try to achieve their goal?

4.12 Explore More

The Cell Cycle (and cancer) [Updated], The Amoeba Sisters, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 4.12.1

Mom and baby by Taiying Lu on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 4.12.2

Cell Cycle by LadyofHats; CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under ![]() • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

Figure 4.12.3

Cell Cycle Checkpoints by LadyofHats; CK-12 Foundation is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under ![]() • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

Figure 4.12.4

Cancer cells forming a tumour by Ed Uthman, MD on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.12.5

Henrietta Lacks by Oregon State University on Flickr is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/) license.

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2018, March 20). The cell cycle (and cancer) [Updated]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QVCjdNxJreE&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2016, February 8). The immortal cells of Henrietta Lacks – Robin Bulleri. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22lGbAVWhro&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 23). Henrietta Lacks. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Henrietta_Lacks&oldid=964020268

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 11). Howard W. Jones. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Howard_W._Jones&oldid=956033806

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 1). George Otto Gey. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=George_Otto_Gey&oldid=965394045

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 6). Johns Hopkins Hospital. In ,Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Johns_Hopkins_Hospital&oldid=966348552

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 28). Jonas Salk. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Jonas_Salk&oldid=964883129

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 14). Rebecca Skloot. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Rebecca_Skloot&oldid=950837115

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, February 21). The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Immortal_Life_of_Henrietta_Lacks&oldid=941942679

A cycle of growth and division that cells go through. It includes interphase (G1, S, and G2) and the mitotic phase.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Communicating with Urine

Why do dogs pee on fire hydrants? Besides “having to go,” they are marking their territory with chemicals in their urine called pheromones. It’s a form of communication, in which they are “saying” with odors that the yard is theirs and other dogs should stay away. In addition to fire hydrants, dogs may urinate on fence posts, trees, car tires, and many other objects. Urination in dogs, as in people, is usually a voluntary process controlled by the brain. The process of forming urine — which occurs in the kidneys — occurs constantly, and is not under voluntary control. What happens to all the urine that forms in the kidneys? It passes from the kidneys through the other organs of the urinary system, starting with the ureters.

Ureters

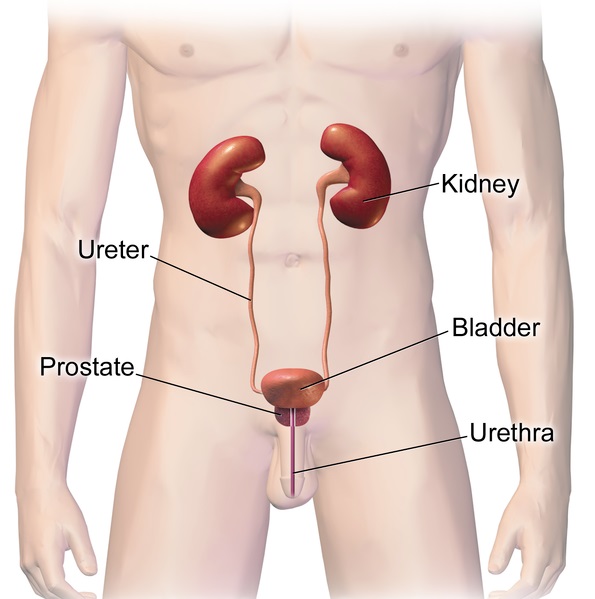

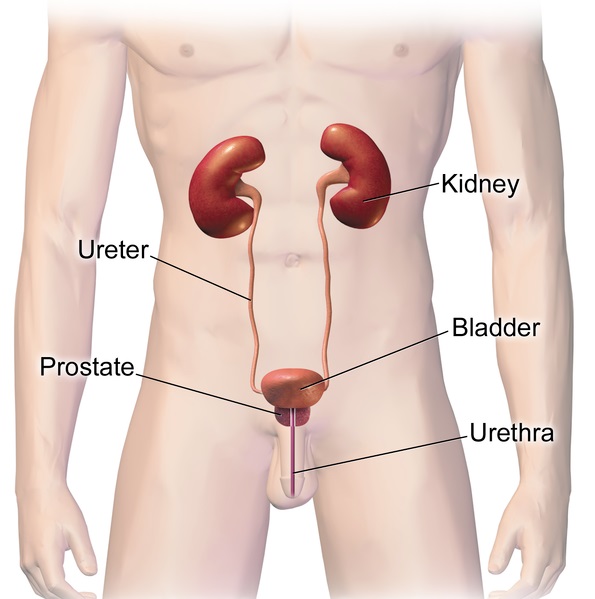

As shown in Figure 16.5.2, ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. They are paired structures, with one ureter for each kidney. In adults, ureters are between 25 and 30 cm (about 10–12 in) long and about 3 to 4 mm in diameter.

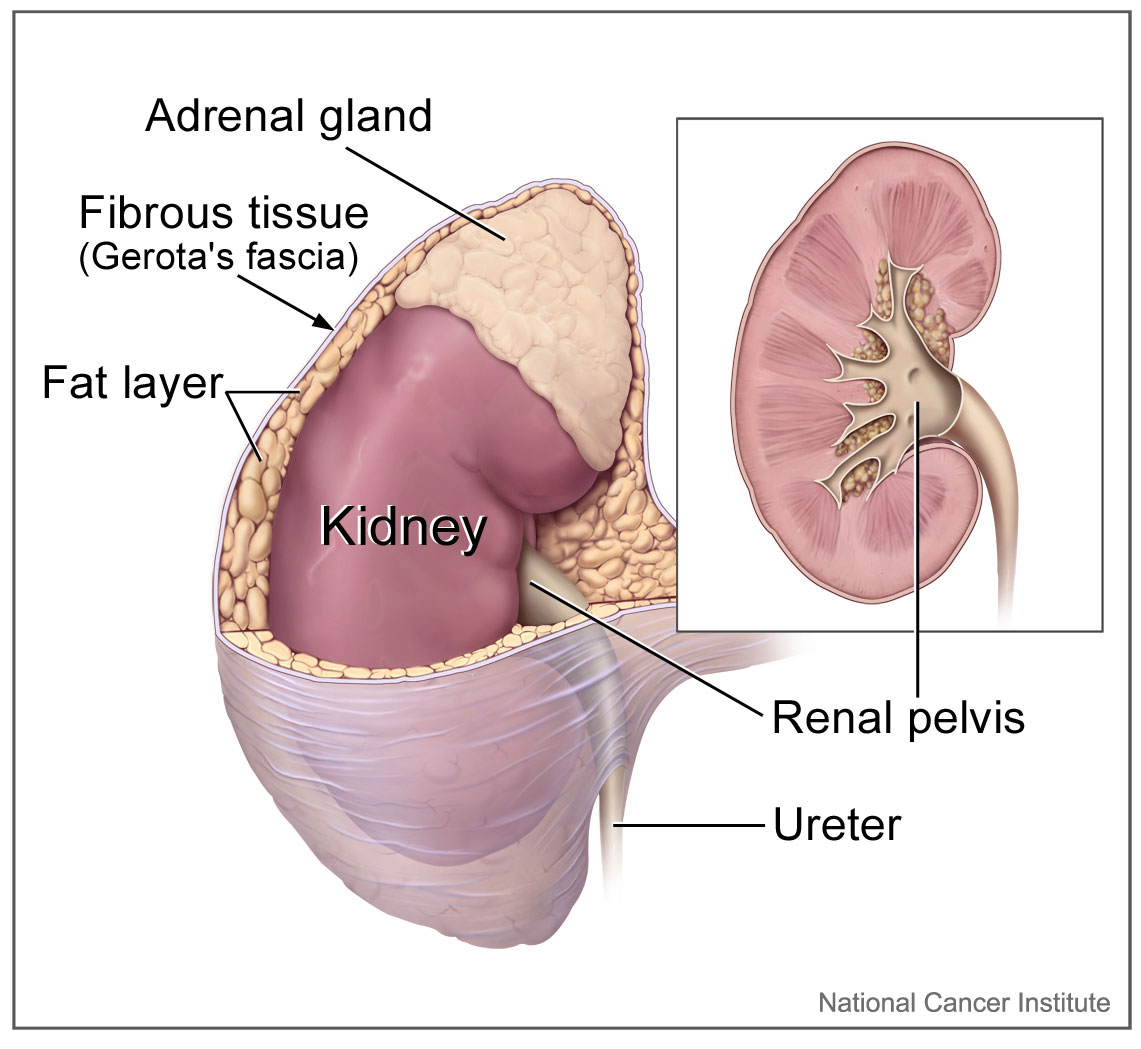

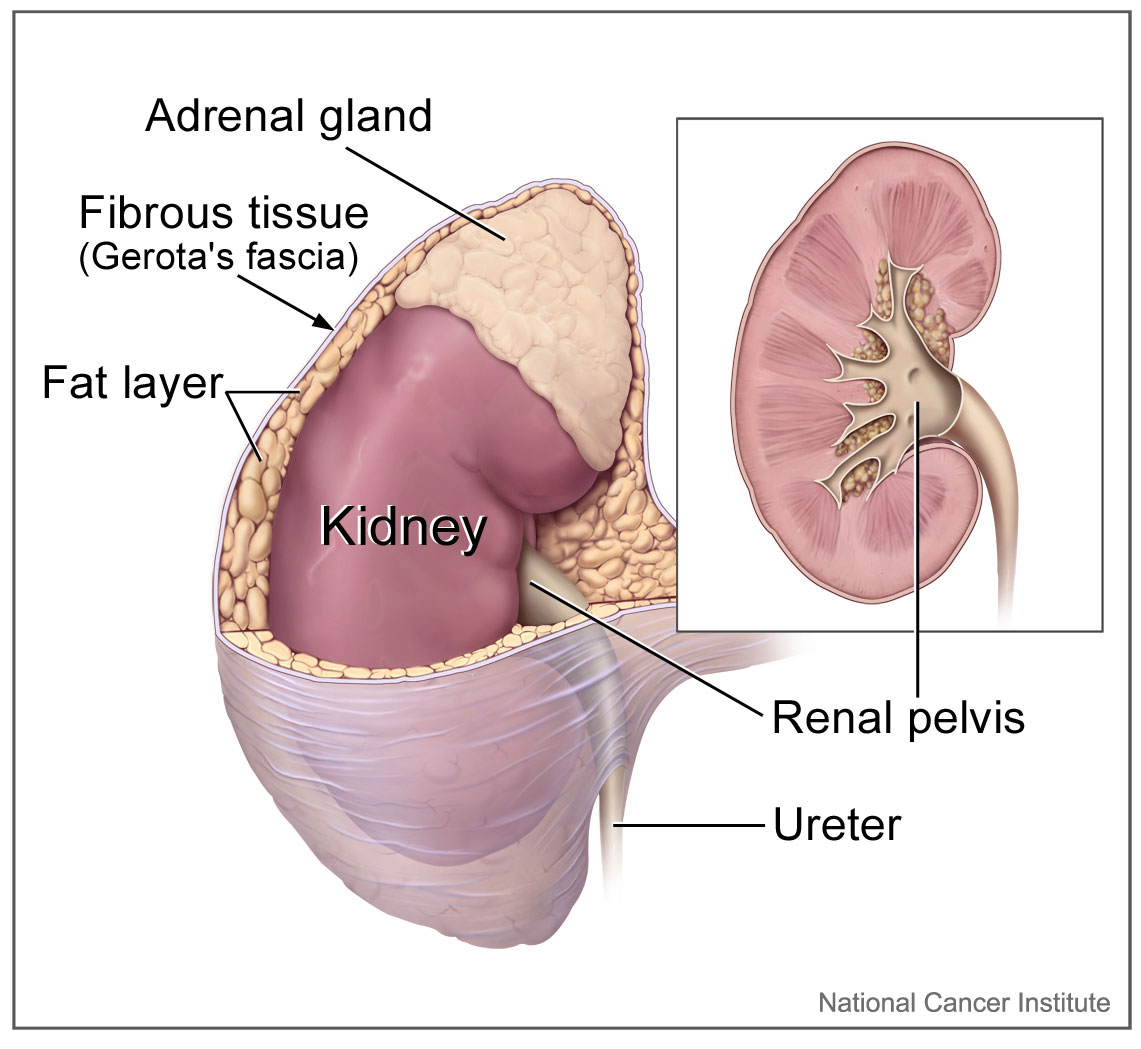

Each ureter arises in the pelvis of a kidney (the renal pelvis in Figure 16.5.3). It then passes down the side of the kidney, and finally enters the back of the bladder. At the entrance to the bladder, the ureters have sphincters that prevent the backflow of urine.

The walls of the ureters are composed of multiple layers of different types of tissues. The innermost layer is a special type of epithelium, called transitional epithelium. Unlike the epithelium lining most organs, transitional epithelium is capable of stretching and does not produce mucus. It lines much of the urinary system, including the renal pelvis, bladder, and much of the urethra, in addition to the ureters. Transitional epithelium allows these organs to stretch and expand as they fill with urine or allow urine to pass through. The next layer of the ureter walls is made up of loose connective tissue containing elastic fibres, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. After this layer are two layers of smooth muscles, an inner circular layer, and an outer longitudinal layer. The smooth muscle layers can contract in waves of peristalsis to propel urine down the ureters from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The outermost layer of the ureter walls consists of fibrous tissue.

Urinary Bladder

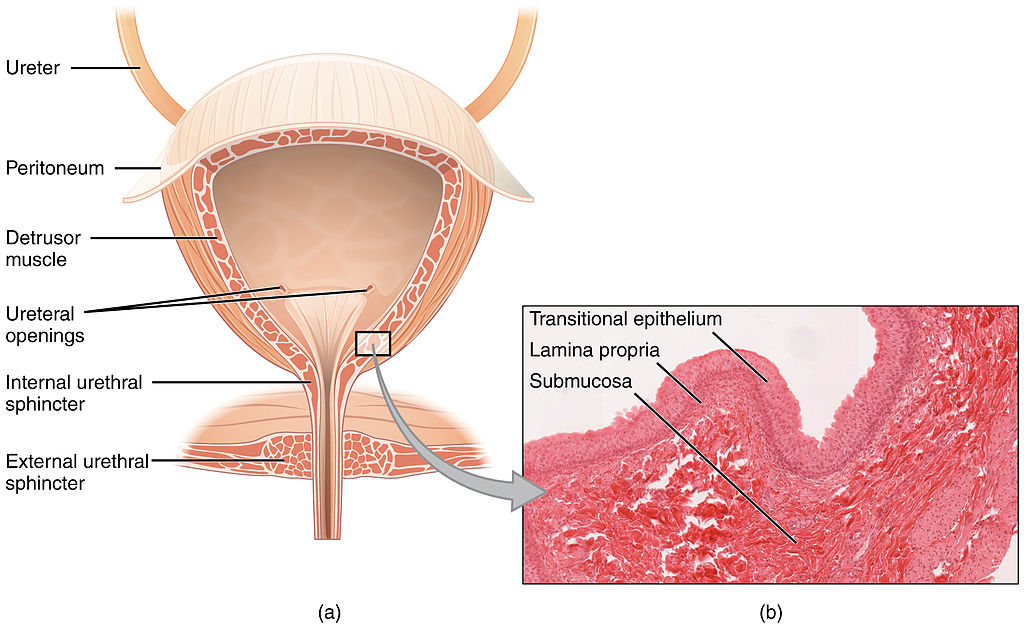

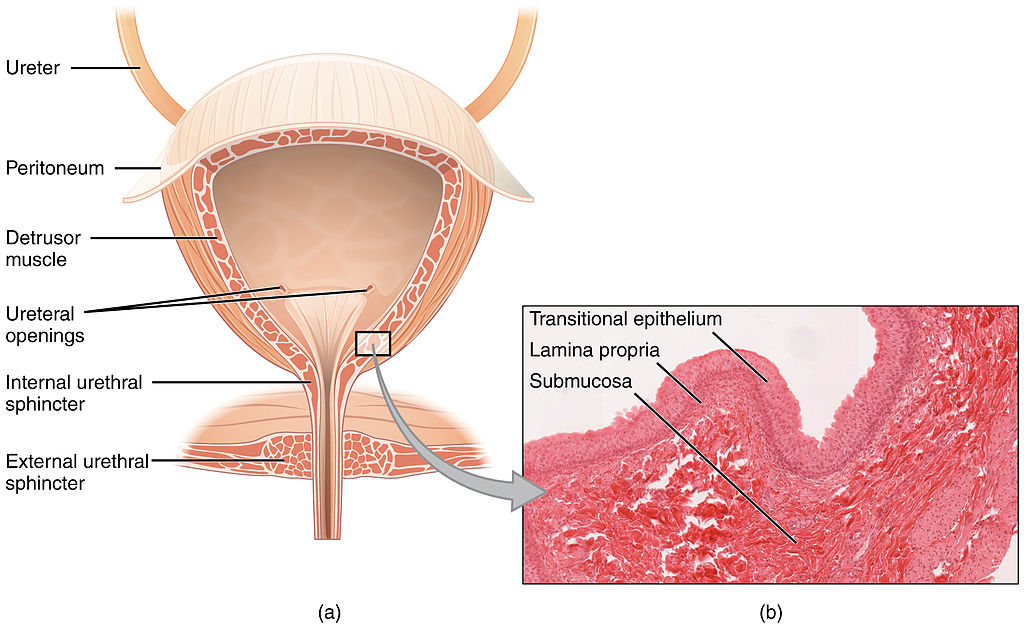

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It collects and stores urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. As shown in Figure 16.5.4, urine enters the urinary bladder from the ureters through two ureteral openings on either side of the back wall of the bladder. Urine leaves the bladder through a sphincter called the internal urethral sphincter. When the sphincter relaxes and opens, it allows urine to flow out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Like the ureters, the bladder is lined with transitional epithelium, which can flatten out and stretch as needed as the bladder fills with urine. The next layer (lamina propria) is a layer of loose connective tissue, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. This is followed by a submucosa layer, which connects the lining of the bladder with the detrusor muscle in the walls of the bladder. The outer covering of the bladder is peritoneum, which is a smooth layer of epithelial cells that lines the abdominal cavity and covers most abdominal organs.

The detrusor muscle in the wall of the bladder is made of smooth muscle fibres controlled by both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills, the detrusor muscle automatically relaxes to allow it to hold more urine. When the bladder is about half full, the stretching of the walls triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When the individual is ready to void, conscious nervous signals cause the detrusor muscle to contract, and the internal urethral sphincter to relax and open. As a result, urine is forcefully expelled out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Urethra

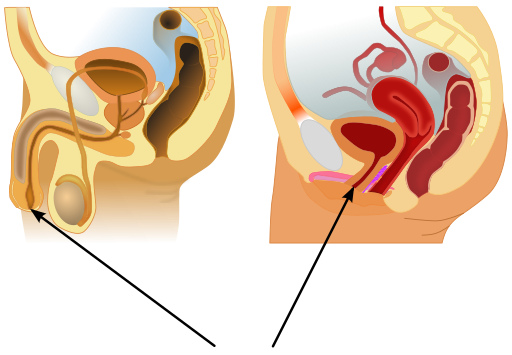

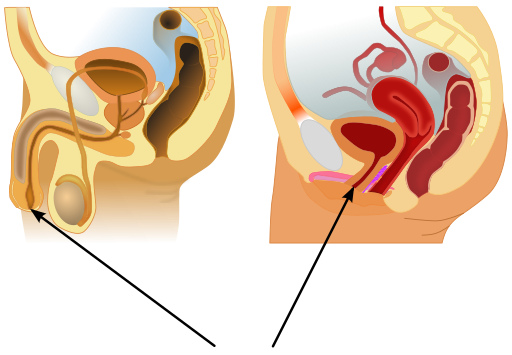

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice, which is the opening of the urethra on the surface of the body. As shown in Figure 16.5.5, the urethra in males travels through the penis, so it is much longer than the urethra in females. In males, the urethra averages about 20 cm (about 7.8 in) long, whereas in females, it averages only about 4.8 cm (about 1.9 in) long. In males, the urethra carries semen (as well as urine), but in females, it carries only urine. In addition, in males, the urethra passes through the prostate gland (part of the reproductive system) which is absent in women.

Like the ureters and bladder, the proximal (closer to the bladder) two-thirds of the urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The distal (farther from the bladder) third of the urethra is lined with mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucus helps protect the epithelium from urine, which is corrosive. Below the epithelium is loose connective tissue, and below that are layers of smooth muscle that are continuous with the muscle layers of the urinary bladder. When the bladder contracts to forcefully expel urine, the smooth muscle of the urethra relaxes to allow the urine to pass through.

In order for urine to leave the body through the external urethral orifice, the external urethral sphincter must relax and open. This sphincter is a striated muscle that is controlled by the somatic nervous system, so it is under conscious, voluntary control in most people (exceptions are infants, some elderly people, and patients with certain injuries or disorders). The muscle can be held in a contracted state and hold in the urine until the person is ready to urinate. Following urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra automatically contracts to re-establish muscle tone, and the individual consciously contracts the external urethral sphincter to close the external urethral opening.

16.5 Summary

- Ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. Each ureter arises at the renal pelvis of a kidney and travels down through the abdomen to the urinary bladder. The walls of the ureter contain smooth muscle that can contract to push urine through the ureter by peristalsis. The walls are lined with transitional epithelium that can expand and stretch.

- The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It is also lined with transitional epithelium. The function of the bladder is to collect and store urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. Filling of the bladder triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When a conscious decision to urinate is made, the detrusor muscle in the bladder wall contracts and forces urine out of the bladder and into the urethra.

- The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice. Somatic nerves control the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra. This allows the opening of the sphincter for urination to be under voluntary control.

16.5 Review Questions

- What are ureters? Describe the location of the ureters relative to other urinary tract organs.

- Identify layers in the walls of a ureter. How do they contribute to the ureter’s function?

- Describe the urinary bladder. What is the function of the urinary bladder?

-

- How does the nervous system control the urinary bladder?

- What is the urethra?

- How does the nervous system control urination?

- Identify the sphincters that are located along the pathway from the ureters to the external urethral orifice.

- What are two differences between the male and female urethra?

- When the bladder muscle contracts, the smooth muscle in the walls of the urethra _________ .

16.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/2Brajdazp1o

The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter, TED. 2016.

https://youtu.be/dg4_deyHLvQ

What Happens When You Hold Your Pee? SciShow, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 16.5.1

Cliche by Jackie on Wikimedia Common s is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 16.5.2

Urinary System Male by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.5.3

Adrenal glands on Kidney by NCI Public Domain by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) /National Cancer Institute (photo ID 4355) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.5.4

2605_The_Bladder by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license. (Micrograph originally provided by the Regents of the University of Michigan Medical School © 2012.)

Figure 16.5.5

512px-Male_and_female_urethral_openings.svg by andrybak (derivative work) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. (Original: Male anatomy blank.svg: alt.sex FAQ, derivative work: Tsaitgaist Female anatomy with g-spot.svg: Tsaitgaist.)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.4 Bladder (a) Anterior cross section of the bladder. (b) The detrusor muscle of the bladder (source: monkey tissue) LM × 448 [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 7.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-2-gross-anatomy-of-urine-transport

SciShow. (2016, January 22). What happens when you hold your pee? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dg4_deyHLvQ&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2016, September 2). The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Brajdazp1o&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Communicating with Urine

Why do dogs pee on fire hydrants? Besides “having to go,” they are marking their territory with chemicals in their urine called pheromones. It’s a form of communication, in which they are “saying” with odors that the yard is theirs and other dogs should stay away. In addition to fire hydrants, dogs may urinate on fence posts, trees, car tires, and many other objects. Urination in dogs, as in people, is usually a voluntary process controlled by the brain. The process of forming urine — which occurs in the kidneys — occurs constantly, and is not under voluntary control. What happens to all the urine that forms in the kidneys? It passes from the kidneys through the other organs of the urinary system, starting with the ureters.

Ureters

As shown in Figure 16.5.2, ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. They are paired structures, with one ureter for each kidney. In adults, ureters are between 25 and 30 cm (about 10–12 in) long and about 3 to 4 mm in diameter.

Each ureter arises in the pelvis of a kidney (the renal pelvis in Figure 16.5.3). It then passes down the side of the kidney, and finally enters the back of the bladder. At the entrance to the bladder, the ureters have sphincters that prevent the backflow of urine.

The walls of the ureters are composed of multiple layers of different types of tissues. The innermost layer is a special type of epithelium, called transitional epithelium. Unlike the epithelium lining most organs, transitional epithelium is capable of stretching and does not produce mucus. It lines much of the urinary system, including the renal pelvis, bladder, and much of the urethra, in addition to the ureters. Transitional epithelium allows these organs to stretch and expand as they fill with urine or allow urine to pass through. The next layer of the ureter walls is made up of loose connective tissue containing elastic fibres, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. After this layer are two layers of smooth muscles, an inner circular layer, and an outer longitudinal layer. The smooth muscle layers can contract in waves of peristalsis to propel urine down the ureters from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The outermost layer of the ureter walls consists of fibrous tissue.

Urinary Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It collects and stores urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. As shown in Figure 16.5.4, urine enters the urinary bladder from the ureters through two ureteral openings on either side of the back wall of the bladder. Urine leaves the bladder through a sphincter called the internal urethral sphincter. When the sphincter relaxes and opens, it allows urine to flow out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Like the ureters, the bladder is lined with transitional epithelium, which can flatten out and stretch as needed as the bladder fills with urine. The next layer (lamina propria) is a layer of loose connective tissue, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. This is followed by a submucosa layer, which connects the lining of the bladder with the detrusor muscle in the walls of the bladder. The outer covering of the bladder is peritoneum, which is a smooth layer of epithelial cells that lines the abdominal cavity and covers most abdominal organs.

The detrusor muscle in the wall of the bladder is made of smooth muscle fibres controlled by both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills, the detrusor muscle automatically relaxes to allow it to hold more urine. When the bladder is about half full, the stretching of the walls triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When the individual is ready to void, conscious nervous signals cause the detrusor muscle to contract, and the internal urethral sphincter to relax and open. As a result, urine is forcefully expelled out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Urethra

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice, which is the opening of the urethra on the surface of the body. As shown in Figure 16.5.5, the urethra in males travels through the penis, so it is much longer than the urethra in females. In males, the urethra averages about 20 cm (about 7.8 in) long, whereas in females, it averages only about 4.8 cm (about 1.9 in) long. In males, the urethra carries semen (as well as urine), but in females, it carries only urine. In addition, in males, the urethra passes through the prostate gland (part of the reproductive system) which is absent in women.

Like the ureters and bladder, the proximal (closer to the bladder) two-thirds of the urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The distal (farther from the bladder) third of the urethra is lined with mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucus helps protect the epithelium from urine, which is corrosive. Below the epithelium is loose connective tissue, and below that are layers of smooth muscle that are continuous with the muscle layers of the urinary bladder. When the bladder contracts to forcefully expel urine, the smooth muscle of the urethra relaxes to allow the urine to pass through.

In order for urine to leave the body through the external urethral orifice, the external urethral sphincter must relax and open. This sphincter is a striated muscle that is controlled by the somatic nervous system, so it is under conscious, voluntary control in most people (exceptions are infants, some elderly people, and patients with certain injuries or disorders). The muscle can be held in a contracted state and hold in the urine until the person is ready to urinate. Following urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra automatically contracts to re-establish muscle tone, and the individual consciously contracts the external urethral sphincter to close the external urethral opening.

16.5 Summary

- Ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. Each ureter arises at the renal pelvis of a kidney and travels down through the abdomen to the urinary bladder. The walls of the ureter contain smooth muscle that can contract to push urine through the ureter by peristalsis. The walls are lined with transitional epithelium that can expand and stretch.

- The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It is also lined with transitional epithelium. The function of the bladder is to collect and store urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. Filling of the bladder triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When a conscious decision to urinate is made, the detrusor muscle in the bladder wall contracts and forces urine out of the bladder and into the urethra.

- The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice. Somatic nerves control the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra. This allows the opening of the sphincter for urination to be under voluntary control.

16.5 Review Questions

- What are ureters? Describe the location of the ureters relative to other urinary tract organs.

- Identify layers in the walls of a ureter. How do they contribute to the ureter’s function?

- Describe the urinary bladder. What is the function of the urinary bladder?

-

- How does the nervous system control the urinary bladder?

- What is the urethra?

- How does the nervous system control urination?

- Identify the sphincters that are located along the pathway from the ureters to the external urethral orifice.

- What are two differences between the male and female urethra?

- When the bladder muscle contracts, the smooth muscle in the walls of the urethra _________ .

16.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/2Brajdazp1o

The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter, TED. 2016.

https://youtu.be/dg4_deyHLvQ

What Happens When You Hold Your Pee? SciShow, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 16.5.1

Cliche by Jackie on Wikimedia Common s is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 16.5.2

Urinary System Male by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.5.3

Adrenal glands on Kidney by NCI Public Domain by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) /National Cancer Institute (photo ID 4355) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.5.4

2605_The_Bladder by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license. (Micrograph originally provided by the Regents of the University of Michigan Medical School © 2012.)

Figure 16.5.5

512px-Male_and_female_urethral_openings.svg by andrybak (derivative work) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. (Original: Male anatomy blank.svg: alt.sex FAQ, derivative work: Tsaitgaist Female anatomy with g-spot.svg: Tsaitgaist.)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.4 Bladder (a) Anterior cross section of the bladder. (b) The detrusor muscle of the bladder (source: monkey tissue) LM × 448 [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 7.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-2-gross-anatomy-of-urine-transport

SciShow. (2016, January 22). What happens when you hold your pee? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dg4_deyHLvQ&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2016, September 2). The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Brajdazp1o&feature=youtu.be

A group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.

inflammation of the epididymis, which may be acute or chronic

The process by which a parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle.

A tiny cellular structure that performs specific functions within a cell.

An evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms.

A structure made up of two lipid bilayer membranes which in eukaryotic cells surrounds the nucleus, which encases the genetic material. Also know as the nuclear membrane.

A threadlike structure of nucleic acids and protein found in the nucleus of most living cells, carrying genetic information in the form of genes.

A synovial joint in which an oval-shaped process of one bone fits into a roughly elliptical cavity of the other, allowing movement in two planes.

A membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells made up of a series of flattened stacked pouches with the purpose of collecting and dispatching protein and lipid products received from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Also referred to as the Golgi complex or the Golgi body.