18.8 Menstrual Cycle

Taboo Topic

The banner in Figure 18.8.1 was carried in a 2014 march in Uganda as part of the celebration of Menstrual Hygiene Day. Menstrual Hygiene Day is an awareness day on May 28 of each year that aims to raise awareness worldwide about menstruation and menstrual hygiene. Maintaining good menstrual hygiene is difficult in developing countries like Uganda because of taboos on discussing menstruation and lack of availability of menstrual hygiene products. Poor menstrual hygiene, in turn, can lead to embarrassment, degradation, and reproductive health problems in females. May 28 was chosen as Menstrual Hygiene Day because of its symbolism. May is the fifth month of the year, and most women average five days of menstrual bleeding each month. The 28th day was chosen because the menstrual cycle averages about 28 days.

What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

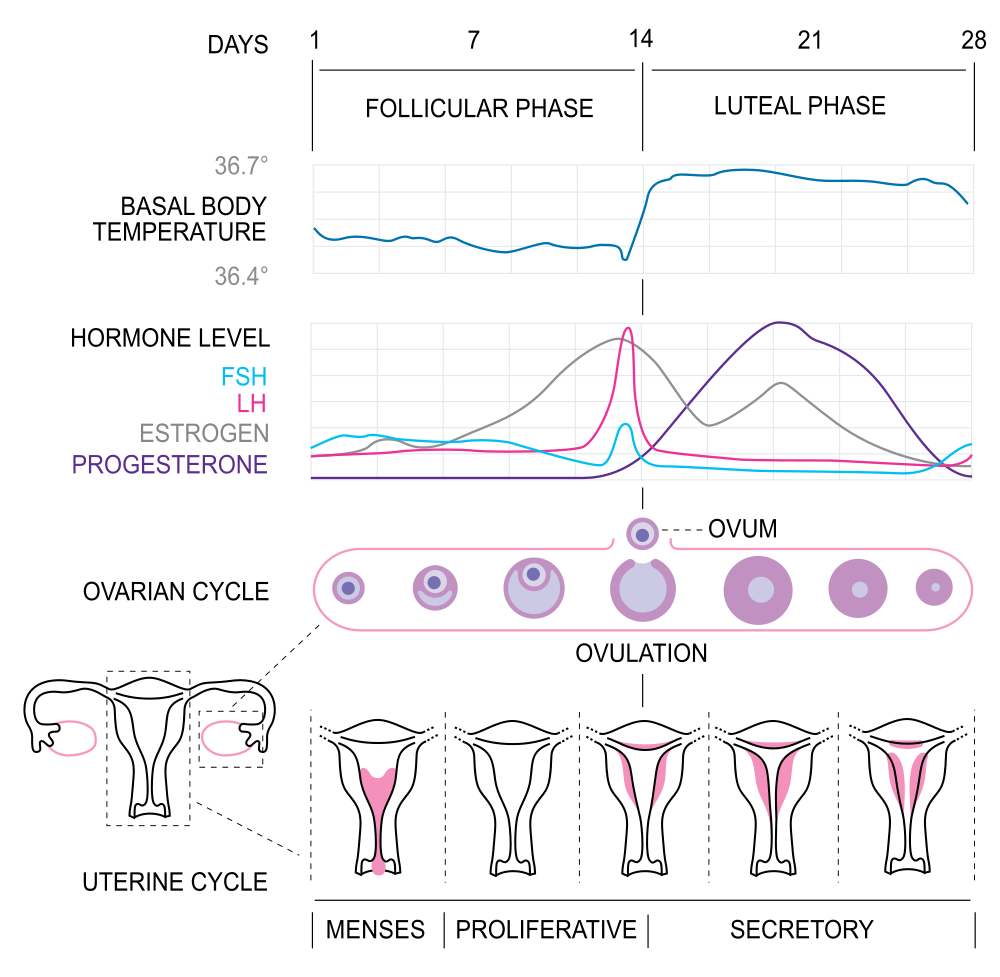

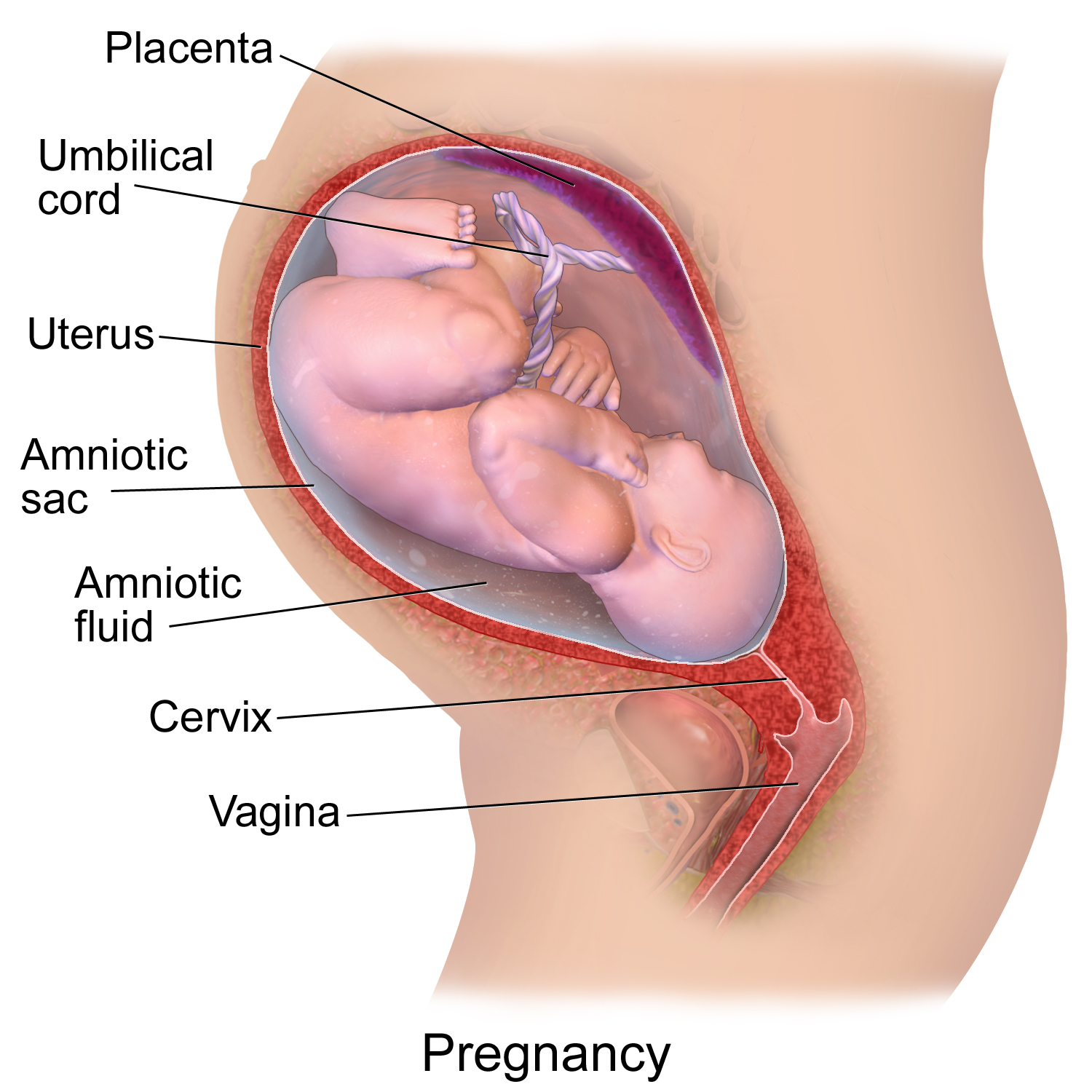

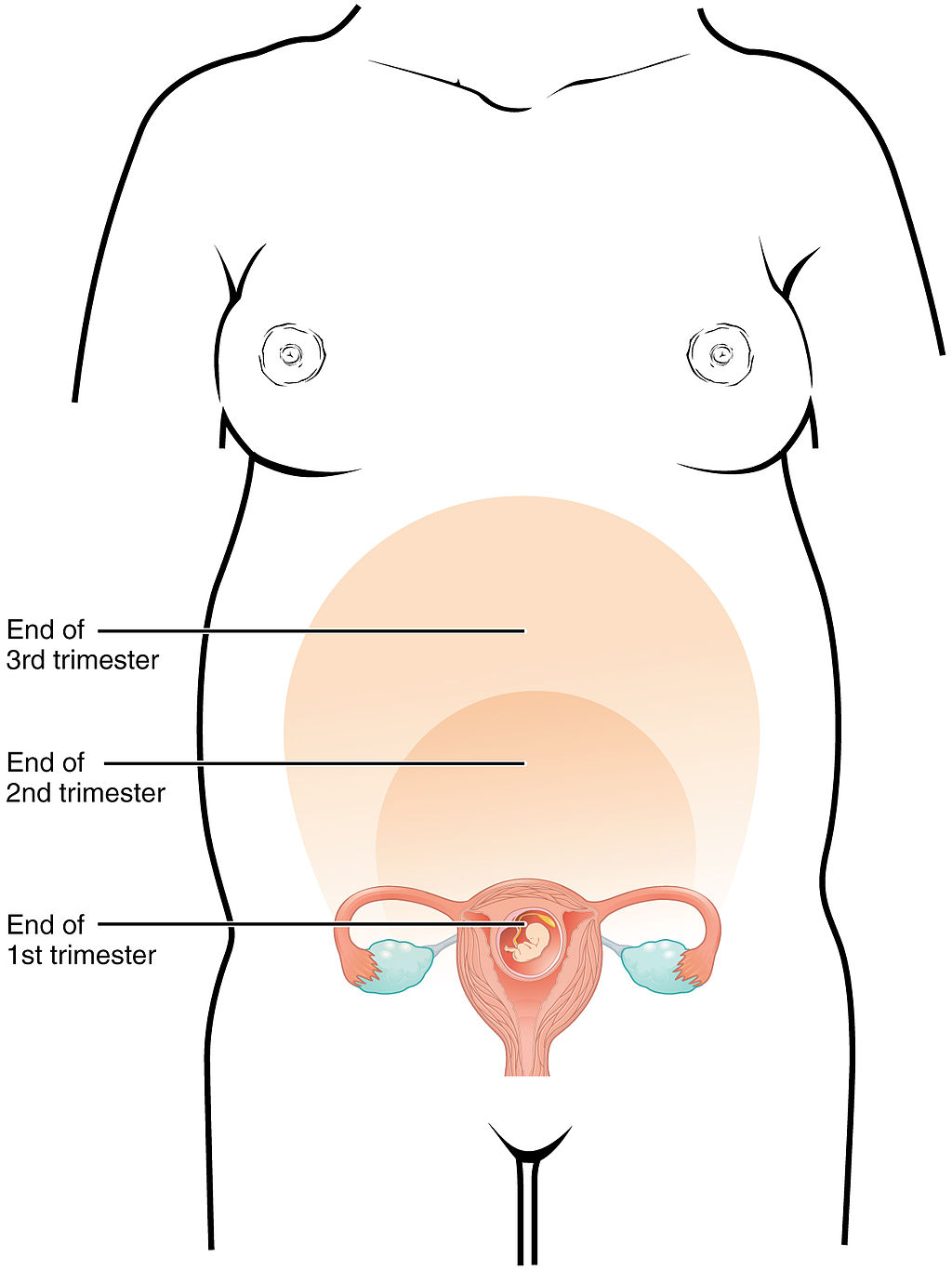

The menstrual cycle refers to natural changes that occur in the female reproductive system each month during the reproductive years. The cycle is necessary for the production of ova and the preparation of the uterus for pregnancy. It involves changes in both the ovaries and the uterus, and is controlled by pituitary and ovarian hormones. Day 1 of the cycle is the first day of the menstrual period, when bleeding from the uterus begins as the built-up endometrium lining the uterus is shed. The endometrium builds up again during the remainder of the cycle, only to be shed again during the beginning of the next cycle if pregnancy does not occur. In the ovaries, the menstrual cycle includes the development of a follicle, ovulation of a secondary oocyte, and then degeneration of the follicle if pregnancy does not occur. Both uterine and ovarian changes during the menstrual cycle are generally divided into three phases, although the phases are not the same in the two organs.

Menarche and Menopause

The female reproductive years are delineated by the start and stop of the menstrual cycle. The first menstrual period usually occurs around 12 or 13 years of age, an event that is known as menarche. There is considerable variation among individuals in the age at menarche. It may occasionally occur as early as eight years of age or as late as 16 years of age and still be considered normal. The average age is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world. This variation is thought to be largely attributable to nutritional differences.

The cessation of menstrual cycles at the end of a woman’s reproductive years is termed menopause. The average age of menopause is 52 years, but it may occur normally at any age between about 45 and 55 years of age. The age of menopause varies due to a variety of biological and environmental factors. It may occur earlier as a result of certain illnesses or medical treatments.

Variation in the Menstrual Cycle

The length of the menstrual cycle — as well as its phases — may vary considerably, not only among different women, but also from month to month for a given woman. The average length of time between the first day of one menstrual period and the first day of the next menstrual period is 28 days, but it may range from 21 days to 45 days. Cycles are considered regular when a woman’s longest and shortest cycles differ by less than eight days. The menstrual period itself is usually about five days long, but it may vary in length from about two days to seven days.

Ovarian Cycle

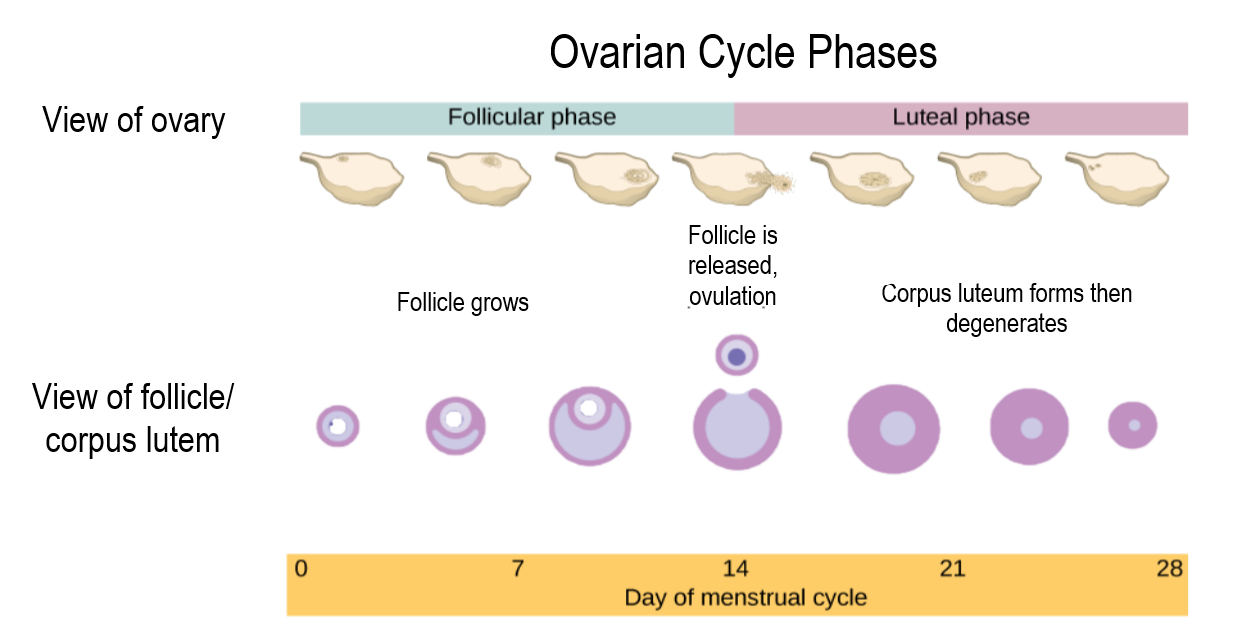

The events of the menstrual cycle that take place in the ovaries make up the ovarian cycle. It consists of changes that occur in the follicles of one of the ovaries. The ovarian cycle is divided into the following three phases: follicular phase, ovulation, and luteal phase. These phases are illustrated in Figure 18.8.2.

Follicular Phase

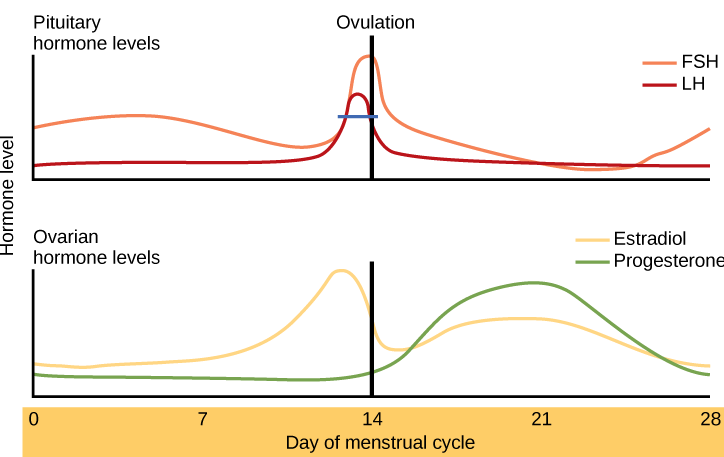

The follicular phase is the first phase of the ovarian cycle. It generally lasts about 12 to 14 days for a 28-day menstrual cycle. During this phase, several ovarian follicles are stimulated to begin maturing, but usually only one — called the Graafian follicle — matures completely so it is ready to release an egg. The other maturing follicles stop growing and disintegrate. Follicular development occurs because of a rise in the blood level of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which is secreted by the pituitary gland. The maturing follicle releases estrogen, the level of which rises throughout the follicular phase. You can see these and other changes in hormone levels that occur during the menstrual cycle in the following chart.

Ovulation

Ovulation is the second phase of the ovarian cycle. It usually occurs around day 14 of a 28-day menstrual cycle. During this phase, the Graafian follicle ruptures and releases its ovum. Ovulation is stimulated by a sudden rise in the blood level of luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary gland. This is called the LH surge. You can see the LH surge in the top hormone graph in Figure 18.8.3. The LH surge generally starts around day 12 of the cycle and lasts for a day or two. The surge in LH is triggered by a continued rise in estrogen from the maturing follicle in the ovary. During the follicular phase, the rising estrogen level actually suppresses LH secretion by the pituitary gland. However, by the time the follicular phase is nearing its end, the level of estrogen reaches a threshold level above which this effect is reversed, and estrogen stimulates the release of a large amount of LH. The surge in LH matures the ovum and weakens the wall of the follicle, causing the fully developed follicle to release its secondary oocyte.

Luteal Phase

The luteal phase is the third and final phase of the ovarian cycle. It typically lasts about 14 days in a 28-day menstrual cycle. At the beginning of the luteal phase, FSH and LH cause the Graafian follicle that ovulated the egg to transform into a structure called a corpus luteum. The corpus luteum secretes progesterone, which in turn suppresses FSH and LH production by the pituitary gland and stimulates the continued buildup of the endometrium in the uterus. How this phase ends depends on whether or not the ovum has been fertilized.

- If fertilization has not occurred, the falling levels of FSH and LH during the luteal phase cause the corpus luteum to atrophy, so its production of progesterone declines. Without a high level of progesterone to maintain it, the endometrium starts to break down. By the end of the luteal phase, the endometrium can no longer be maintained, and the next menstrual cycle begins with the shedding of the endometrium (menses).

- If fertilization has occurred so a zygote forms and then divides to become a blastocyst, the outer layer of the blastocyst produces a hormone called human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). This hormone is very similar to LH and preserves the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum can then continue to secrete progesterone to maintain the new pregnancy.

Uterine Cycle

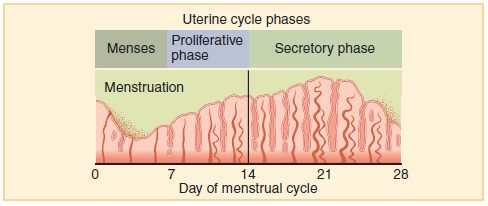

The events of the menstrual cycle that take place in the uterus make up the uterine cycle. This cycle consists of changes that occur mainly in the endometrium, which is the layer of tissue that lines the uterus. The uterine cycle is divided into the following three phases: menstruation, proliferative phase, and secretory phase. These phases are illustrated in Figure 18.8.4.

Menstruation

Menstruation (also called menstrual period or menses) is the first phase of the uterine cycle. It occurs if fertilization has not taken place during the preceding menstrual cycle. During menstruation, the endometrium of the uterus, which has built up during the preceding cycle, degenerates and is shed from the uterus, flowing through an opening in the cervix, and out through the external opening of the vagina. The average loss of blood during menstruation is about 35 mL (about 1 oz or 2 tablespoons). The flow of blood is often accompanied by uterine cramps, which may be severe in some women.

Proliferative Phase

The proliferative phase is the second phase of the uterine cycle. During this phase, estrogen secreted by cells of the maturing ovarian follicle causes the lining of the uterus to grow, or proliferate. Estrogen also stimulates the cervix of the uterus to secrete larger amounts of thinner mucus that can help sperm swim through the cervix and into the uterus, making fertilization more likely.

Secretory Phase

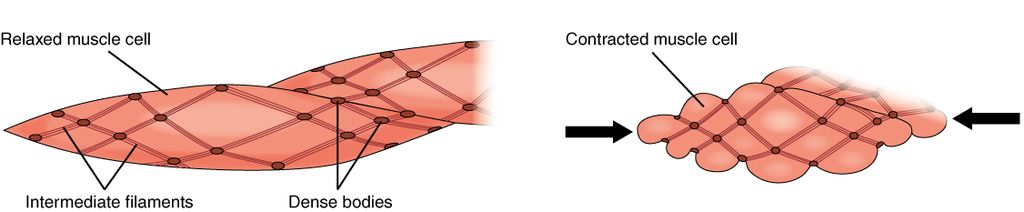

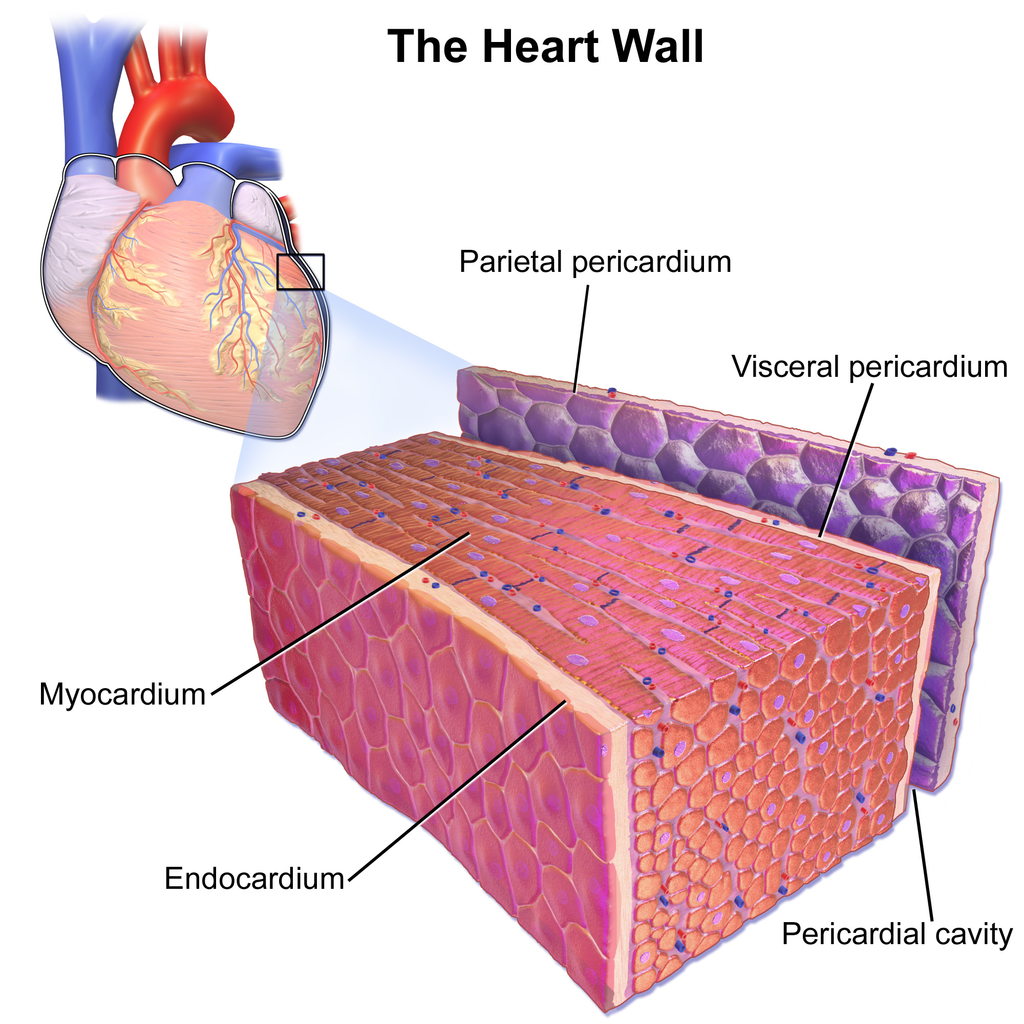

The secretory phase is the third and final phase of the uterine cycle. During this phase, progesterone produced by the corpus luteum in the ovary stimulates further changes in the endometrium so it is more receptive to implantation of a blastocyst. For example, progesterone increases blood flow to the uterus and promotes uterine secretions. It also decreases the contractility of smooth muscle tissue in the uterine wall.

Bringing it All Together

It is important to note that the pituitary gland, the ovaries and the uterus are all responsible for parts of the ovarian and uterine cycles. The pituitary hormones, LH and FSH affect the ovarian cycle and its hormones. The ovarian hormones, estrogen and progesterone affect the uterine cycle and also feedback on the pituitary gland. Look at Figure 18.8.5 and look at what is happening on different days of the cycle in each of the sets of hormones, the ovarian cycle and the uterine cycle.

18.8 Summary

- The menstrual cycle refers to natural changes that occur in the female reproductive system each month during the reproductive years, except when a woman is pregnant. The cycle is necessary for the production of ova and the preparation of the uterus for pregnancy. It involves changes in both the ovaries and uterus, and is controlled by pituitary gland hormones (FSH and LH) and ovarian hormones (estrogen and progesterone).

- The female reproductive period is delineated by menarche, or the first menstrual period, which usually occurs around age 12 or 13; and by menopause, or the cessation of menstrual periods, which typically occurs around age 52. A typical menstrual cycle averages 28 days in length but may vary normally from 21 to 45 days. The average menstrual period is five days long, but may vary normally from two to seven days. These variations in the menstrual cycle may occur both between women and within individual women from month to month.

- The events of the menstrual cycle that take place in the ovaries make up the ovarian cycle. It includes the follicular phase (when a follicle and its ovum mature due to rising levels of FSH), ovulation (when the ovum is released from the ovary due to a rise in estrogen and a surge in LH), and the luteal phase (when the follicle is transformed into a structure called a corpus luteum that secretes progesterone). In a 28-day menstrual cycle, the follicular and luteal phases typically average about two weeks in length, with ovulation generally occurring around day 14 of the cycle.

- The events of the menstrual cycle that take place in the uterus make up the uterine cycle. It includes menstruation, which generally occurs on days 1 to 5 of the cycle and involves shedding of endometrial tissue that built up during the preceding cycle; the proliferative phase, during which the endometrium builds up again until ovulation occurs; and the secretory phase, which follows ovulation and during which the endometrium secretes substances and undergoes other changes that prepare it to receive an embryo.

18.8 Review Questions

-

- What is the menstrual cycle? Why is the menstrual cycle necessary in order for pregnancy to occur?

- What organs are involved in the menstrual cycle?

- Identify the two major events that mark the beginning and end of the reproductive period in females. When do these events typically occur?

- Discuss the average length of the menstrual cycle and menstruation, as well as variations that are considered normal.

- If the LH surge did not occur in a menstrual cycle, what do you think would happen? Explain your answer.

- Give one reason why FSH and LH levels drop in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.

18.8 Explore More

Why do women have periods? TED-Ed, 2015.

Girl’s Rite of Passage | National Geographic, 2007.

Attributions

Figure 18.8.1

WaterforPeople_Uganda by WaterforPeople_Uganda on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 18.8.2

Ovarian Cycle by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 18.8.3

Figure_43_04_04 by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license. (Original: modification of work by Mikael Häggström)

Figure 18.8.4

Ovarian and menstrual cycle by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 18.8.5

1000px-MenstrualCycle2_en.svg by Isometrik on Wikimedia Common is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 27.15 Hormone levels in ovarian and menstrual cycles [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 27.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/27-2-anatomy-and-physiology-of-the-female-reproductive-system

National Geographic. (2007, May 31). Girl’s rite of passage | National Geographic. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5B3Abpv0ysM&feature=youtu.be

OpenStax. (2016, May 27) Figure 4 Rising and falling hormone levels result in progression of the ovarian and menstrual cycles [digital image]. In Open Stax, Biology (Section 43.4). OpenStax CNX. https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.53:Ha3dnFEx@6/Hormonal-Control-of-Human-Reproduction

TED-Ed. (2015, October 19). Why do women have periods? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cjbgZwgdY7Q&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a health professional administering a vaccine to a child. The childs mother is holding them.

Image shows a diagram labeling the major arteries of the body. Some of these include the carotid artery which provides blood to the neck and head, the brachiocephalic artery which supplies blood to the arms and head, the renal artery supplying blood to the kidneys, the mesenteric arteries supplying blood to the intestines, the femoral arteries supplying blood to the legs.

Image shows a two part diagram of inflammatory response. The first pane shows an initial injury to the skin and introduction of pathogens to deeper tissues. Mast cells release clouds of histamines into the tissue.

In the second pane, the capillaries have become more porous, due to the histamines. Leukocytes are squeezing out of the capillary into the injured tissue, where they will phagocytize any pathogens they come across.

Image shows a diagram of the process of hemodialysis. Blood is removed from the patient from a location on the arm. Blood enters the hemodialysis apparatus and is run through dialyser to clean wastes from the blood. There are mechanisms to maintain blood tonicity and pressure, to prevent clotting, and ensure no air enters the bloodstream. The cleaned blood is returned to the patient in their arm, proximal to the place where the blood was first removed.

Image shows a photo of a young man.

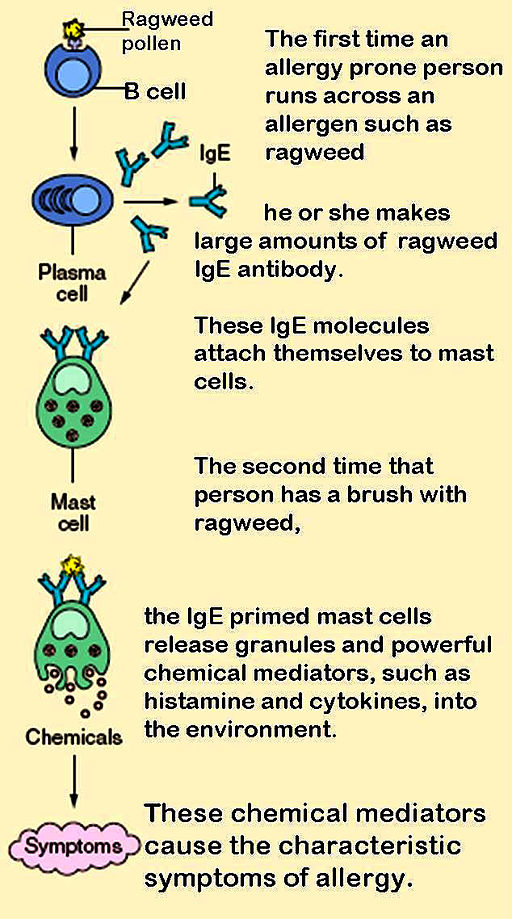

Image shows the sequence of events leading to an allergic reaction. The text reads: The first time an allergy prone person runs across an allergen such as ragweed, he or she makes large amounts of ragweed antibody. These antibodies attach themselves to mast cells. The second time that person has a brush with ragweed, the primed mast cells release granules and powerful chemical mediators such as histamine and cytokines into the environment. These chemical mediators cause the typical symptoms of allergies.

Case Study: Defending Your Defenses

Twenty-six-year-old Hakeem wasn’t feeling well. He was more tired than usual, dragging through his workdays despite going to bed earlier, and napping on the weekends. He didn’t have much of an appetite, and had started losing weight. When he pressed on the side of his neck, like the doctor is doing in Figure 17.1.1, he noticed an unusual lump.

Hakeem went to his doctor, who performed a physical exam and determined that the lump was a swollen lymph node. Lymph nodes are part of the immune system, and they will often become enlarged when the body is fighting off an infection. Dr. Hayes thinks that the swollen lymph node and fatigue could be signs of a viral or bacterial infection, although he is concerned about Hakeem’s lack of appetite and weight loss. All of those symptoms combined can indicate a type of cancer called lymphoma. An infection, however, is a more likely cause, particularly in a young person like Hakeem. Dr. Hayes prescribes an antibiotic in case Hakeem has a bacterial infection, and advises him to return in a few weeks if his lymph node does not shrink, or if he is not feeling better.

Hakeem returns a few weeks later. He is not feeling better and his lymph node is still enlarged. Dr. Hayes is concerned, and orders a biopsy of the enlarged lymph node. A lymph node biopsy for suspected lymphoma often involves the surgical removal of all or part of a lymph node. This helps to determine whether the tissue contains cancerous cells.

The initial results of the biopsy indicate that Hakeem does have lymphoma. Although lymphoma is more common in older people, young adults and even children can get this disease. There are many types of lymphoma, with the two main types being Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), in turn, has many subtypes. The subtype depends on several factors, including which cell types are affected. Some subtypes of NHL, for example, affect immune system cells called B cells, while others affect different immune system cells called T cells.

Dr. Hayes explains to Hakeem that it is important to determine which type of lymphoma he has, in order to choose the best course of treatment. Hakeem’s biopsied tissue will be further examined and tested to see which cell types are affected, as well as which specific cell-surface proteins — called antigens — are present. This should help identify his specific type of lymphoma.

As you read this chapter, you will learn about the functions of the immune system, and the specific roles that its cells and organs — such as B and T cells and lymph nodes — play in defending the body. At the end of this chapter, you will learn what type of lymphoma Hakeem has and what some of his treatment options are, including treatments that make use of the biochemistry of the immune system to fight cancer with the immune system itself.

Chapter Overview: Immune System

In this chapter, you will learn about the immune system — the system that defends the body against infections and other causes of disease, such as cancerous cells. Specifically, you will learn about:

- How the immune system identifies normal cells of the body as “self” and pathogens and damaged cells as “non-self.”

- The two major subsystems of the general immune system: the innate immune system — which provides a quick, but non-specific response — and the adaptive immune system, which is slower, but provides a specific response that often results in long-lasting immunity.

- The specialized immune system that protects the brain and spinal cord, called the neuroimmune system.

- The organs, cells, and responses of the innate immune system, which includes physical barriers (such as skin and mucus), chemical and biological barriers, inflammation, activation of the complement system of molecules, and non-specific cellular responses (such as phagocytosis).

- The lymphatic system — which includes white blood cells called lymphocytes, lymphatic vessels (which transport a fluid called lymph), and organs (such as the spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes) — and its important role in the adaptive immune system.

- Specific cells of the immune system and their functions, including B cells, T cells, plasma cells, and natural killer cells.

- How the adaptive immune system can generate specific and often long-lasting immunity against pathogens through the production of antibodies.

- How vaccines work to generate immunity.

- How cells in the immune system detect and kill cancerous cells.

- Some strategies that pathogens employ to evade the immune system.

- Disorders of the immune system, including allergies, autoimmune diseases (such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis), and immunodeficiency resulting from conditions such as HIV infection.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- What are the functions of lymph nodes?

- What are B and T cells? How do they relate to lymph nodes?

- What are cell-surface antigens? How do they relate to the immune system and to cancer?

Attributions

Figure 17.1.1

Lymph nodes/Is it a Cold or the Flu by Lee Health on Vimeo is used under Vimeo's Terms of Service (https://vimeo.com/terms#licenses).

Figure 17.1.2

mitchell-luo-ymo_yC_N_2o-unsplash [photo] by Mitchell Luo on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 17.1.3

Lymph node biopsy by US Army Africa on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

References

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Hodgkin's lymphoma [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hodgkins-lymphoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20352646

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/non-hodgkins-lymphoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20375680

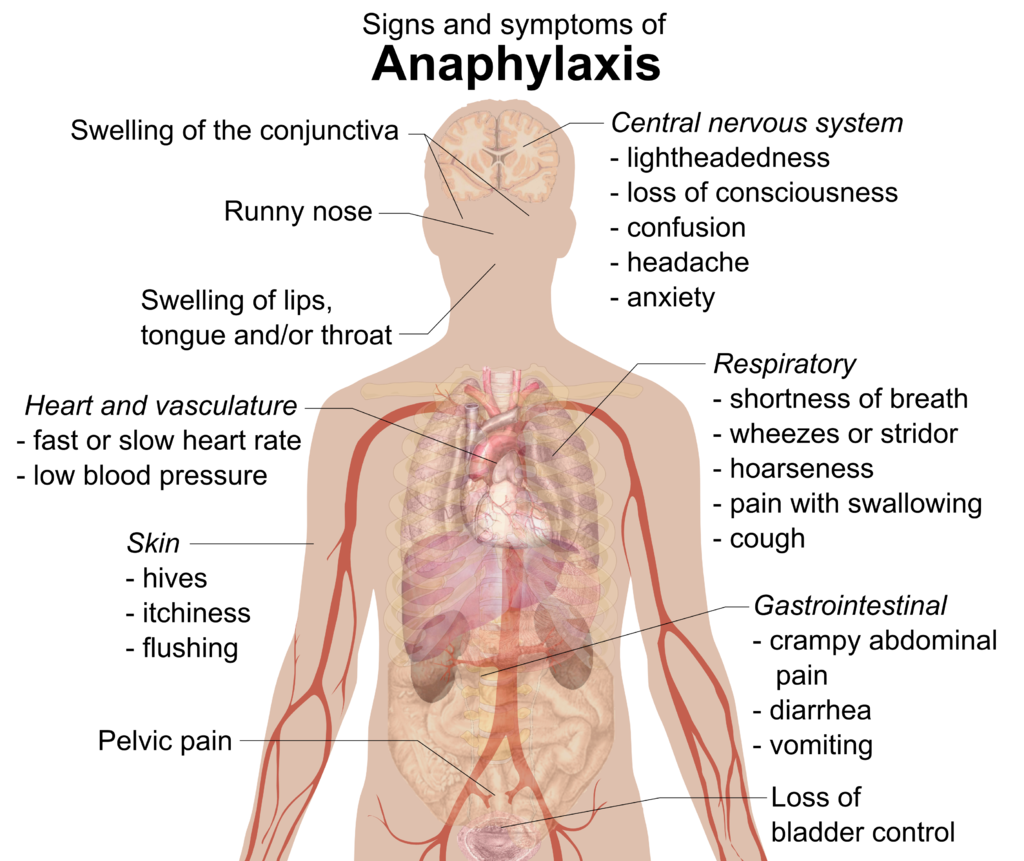

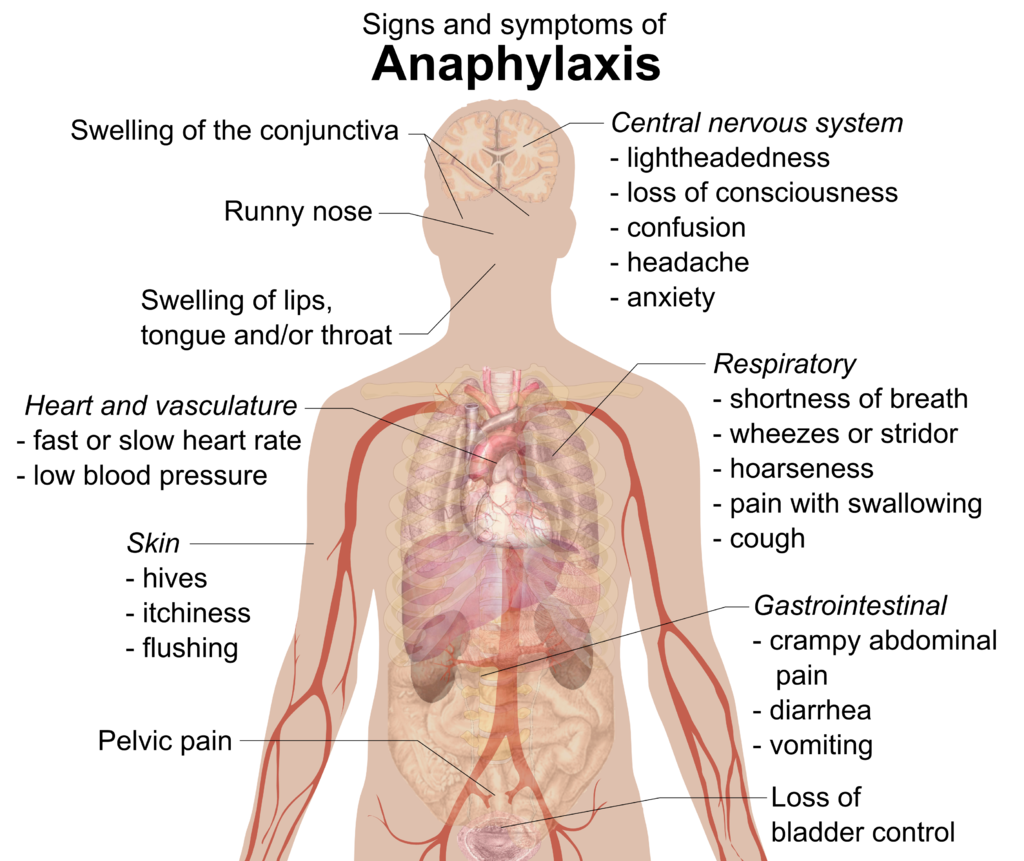

Image shows a diagram of the human body outlining the effects of anaphylaxis and where they occur in the body. These include: swelling of the tissues around the eyes, runny nose, swelling of lips, tongue and/or throat, fast or slow heartrate, low blood pressure, skin hives and itchiness, pelvic pain, lightheadedness, loss of consciousness, confusion, headache, anxiety, shortness of breath, wheezing, hoarseness, painful swallowing, cough, cramps and abdominal pains, diarrhea, vomiting, and loss of bladder control

A testable proposed explanation for a phenomenon.

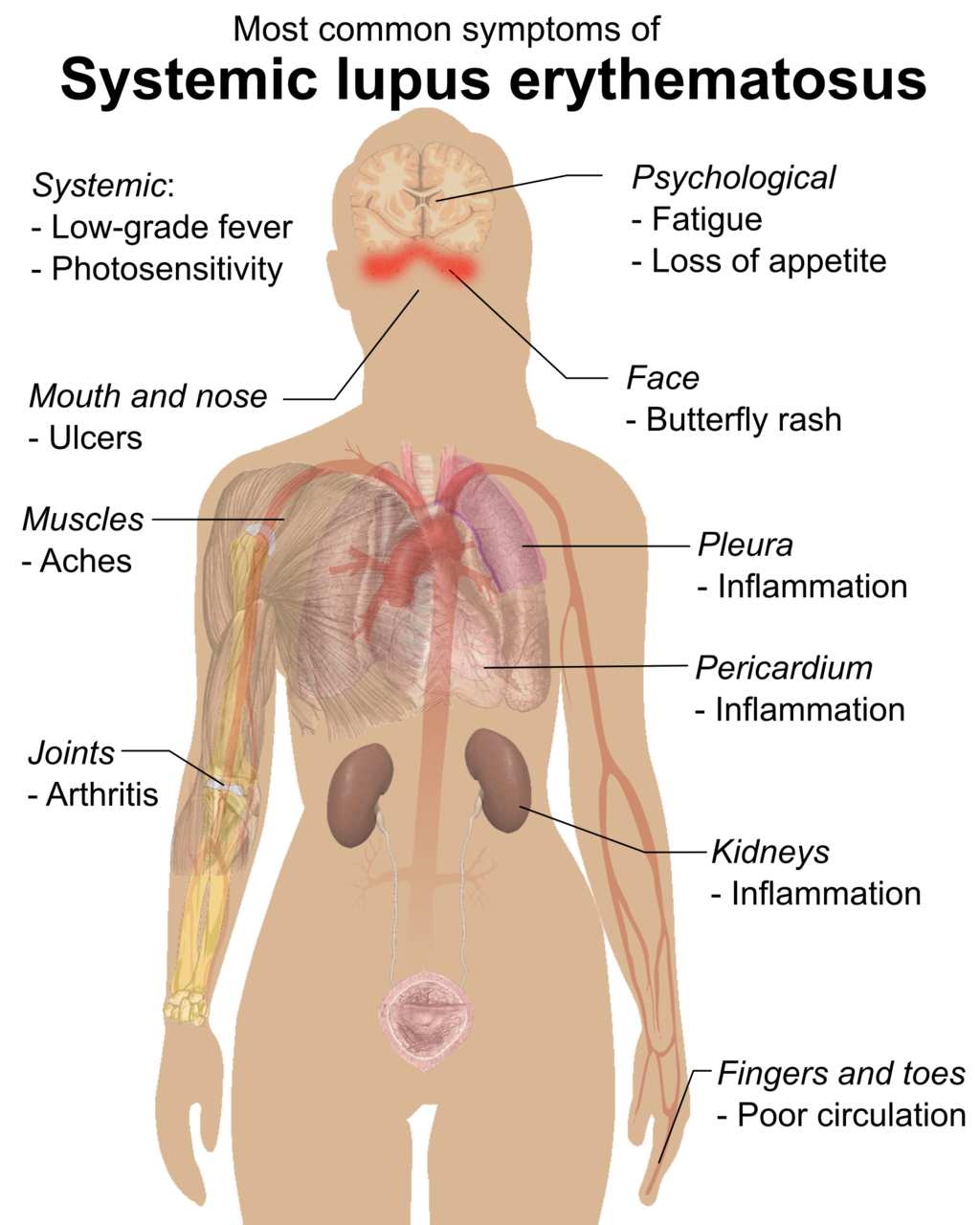

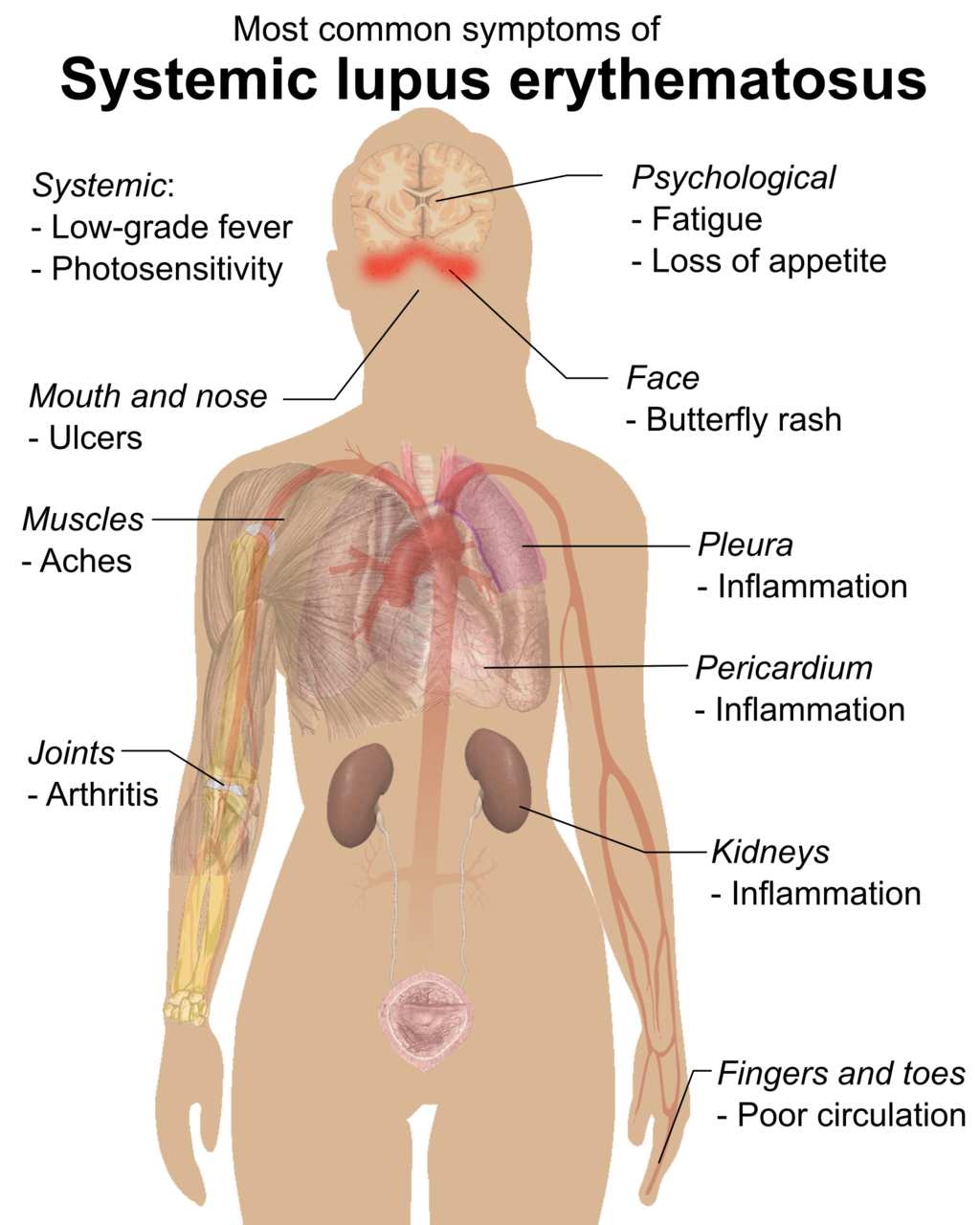

Image shows a diagram depicting the locations of the symptoms of Lupus. These include: low grade fever, photosensitivity, ulcers in the mouth and nose, muscle pain, joint pain, fatigue, loss of appetite, facial rash, inflammation of the lungs heart and kidneys, and poor circulation of the extremities.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Drink and Flush

“Wow, this line for the restroom is long!” Shae says to Talia, anxiously bobbing from side to side to ease the pressure in her bladder. Talia nods and says, “It’s always like this at parties. It’s the alcohol.”

Shae and Talia are 21-year-old college students at a party. They — along with the other party guests — have been drinking alcoholic beverages over the course of the evening. As the night goes on, the line for the restroom has gotten longer and longer. You may have noticed this phenomenon if you have been to places where large numbers of people are drinking alcohol, like at the ballpark in Figure 16.1.2.

Shae says, “I wonder why alcohol makes you have to pee?” Talia says she learned about this in her Human Biology class. She tells Shae that alcohol inhibits a hormone that helps you retain water. Instead of your body retaining water, you urinate more out. This could lead to dehydration, so she suggests that after their trip to the restroom, they start drinking water, instead of alcohol.

For people who drink occasionally or moderately, this effect of alcohol on the excretory system — the system that removes wastes such as urine — is usually temporary. However, in people who drink excessively, alcohol can have serious, long-term effects on the excretory system. Heavy drinking on a regular basis can cause liver and kidney disease.

As you will learn in this chapter, the liver and kidneys are important organs of the excretory system, and impairment of the functioning of these organs can cause serious health consequences. At the end of the chapter, you will learn which hormone Talia was referring to. You will also learn some of the ways alcohol can affect the excretory system — both after the occasional drink, and in cases of excessive alcohol use and abuse.

Chapter Overview: Excretory System

In this chapter, you will learn about the excretory system, which rids the body of toxic waste products and helps maintain homeostasis. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The organs of the excretory system —including the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys — that eliminate waste and excess water from the body.

- How wastes are eliminated through sweat, feces, urine, and exhaled gases.

- How toxic substances in the blood are broken down by the liver.

- The urinary system, which includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra.

- The main function of the urinary system, which is to filter the blood and eliminate wastes, mineral ions, and excess water from the body in the form of urine.

- How the kidneys filter the blood, retain necessary substances, produce urine, and help maintain homeostasis (such as proper ion and water balance).

- How urine is stored, transported, and released from the body.

- Disorders of the urinary system, including bladder infections, kidney stones, polycystic kidney disease, urinary incontinence, and kidney damage caused by factors such as uncontrolled diabetes and high blood pressure.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- Which hormone do you think Talia was referring to? Remember that this hormone causes the urinary system to retain water and excrete less water out in urine.

- How and where does this hormone work?

- Long-term, excessive use of alcohol can affect the liver and kidneys. How do these two organs of excretion interact and work together?

Attributions

Figure 16.1.1

Gotta Pee [photo] by Jon-Eric Melsæter on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 16.1.2

Bathroom line up [photo] by Dorothy on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

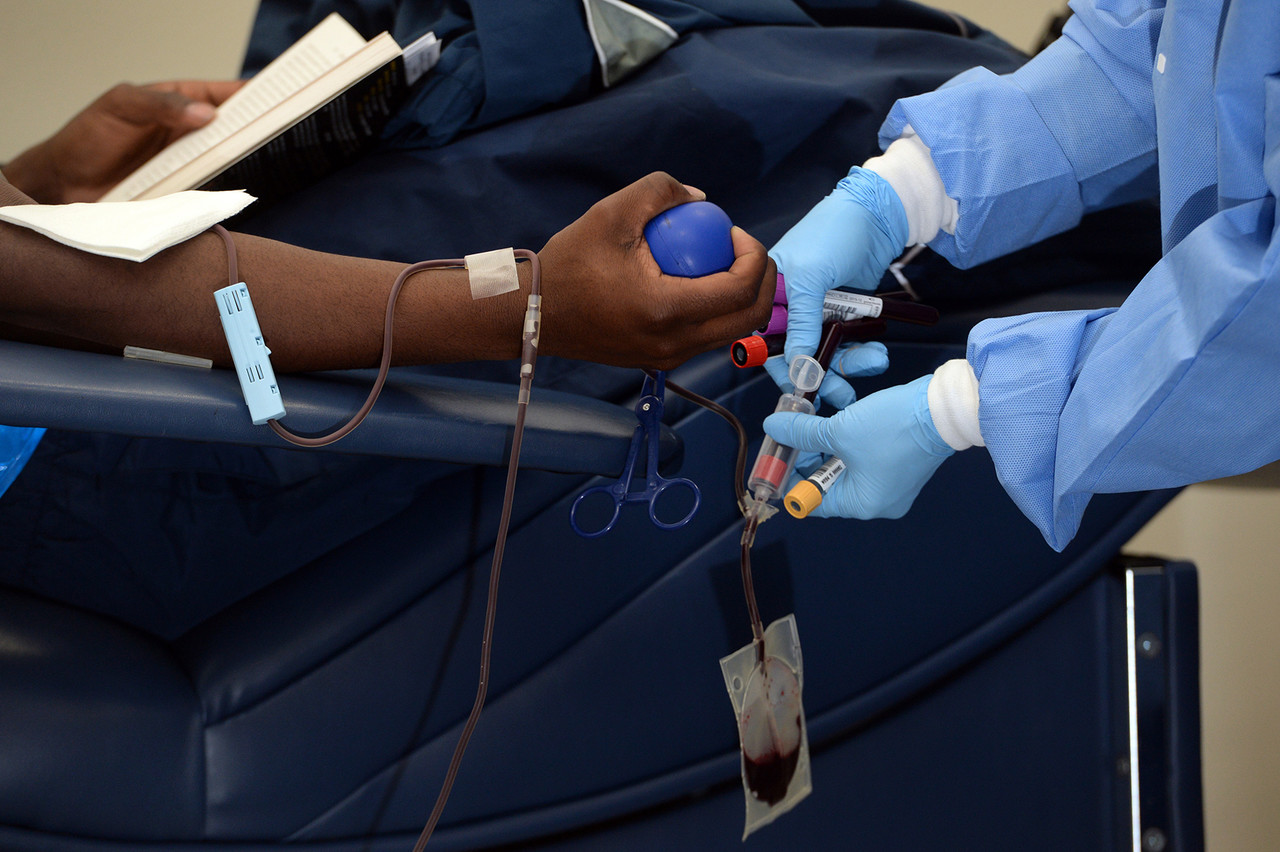

Giving the Gift of Life

Did you ever donate blood? If you did, then you probably know that your blood type is an important factor in blood transfusions. People vary in the type of blood they inherit, and this determines which type(s) of blood they can safely receive in a transfusion. Do you know your blood type?

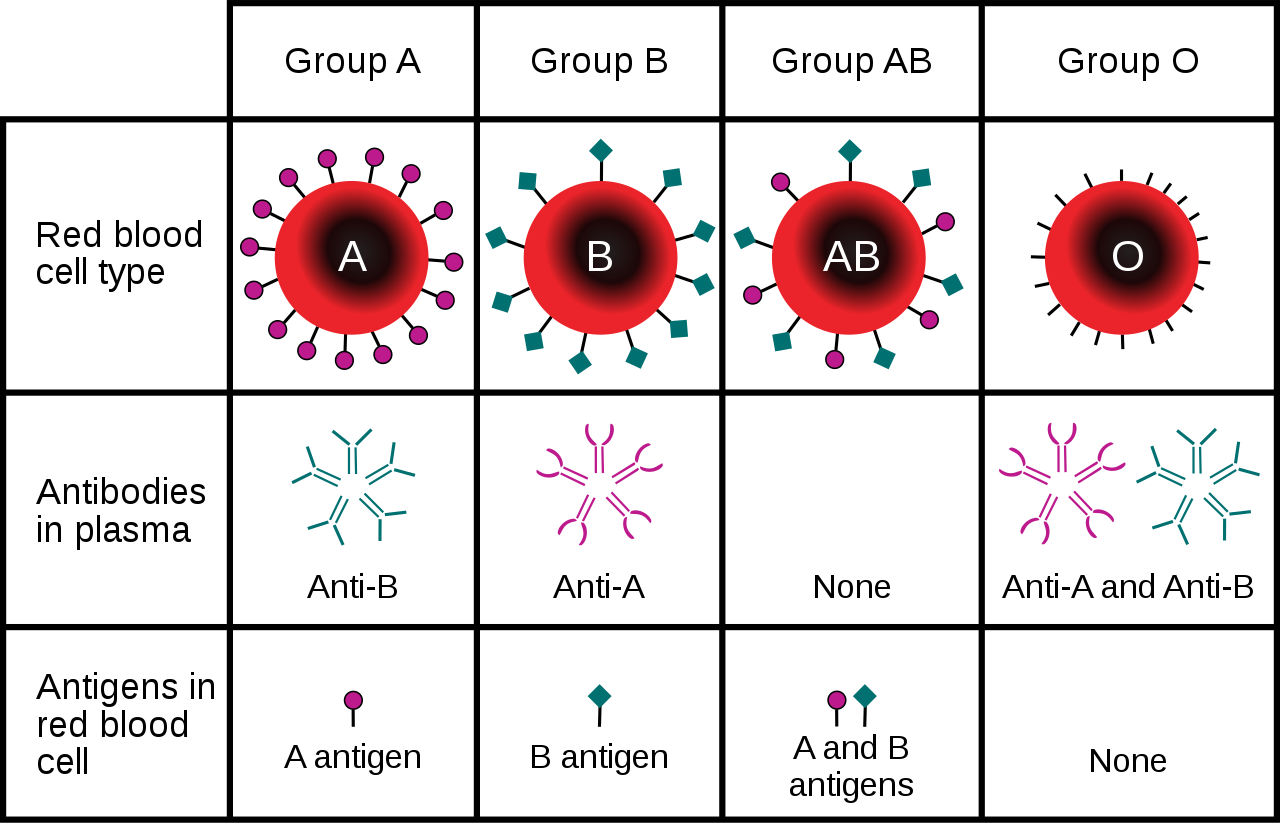

What Are Blood Types?

Blood is composed of cells suspended in a liquid called plasma. There are three types of cells in blood: red blood cells, which carry oxygen; white blood cells, which fight infections and other threats; and platelets, which are cell fragments that help blood clot. Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of certain molecules, called antigens, on the surface of red blood cells. These molecules may help maintain the integrity of the cell membrane, act as receptors, or have other biological functions. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens. Human blood group systems include the well-known ABO and Rhesus (Rh) systems, as well as at least 33 others that are less well known.

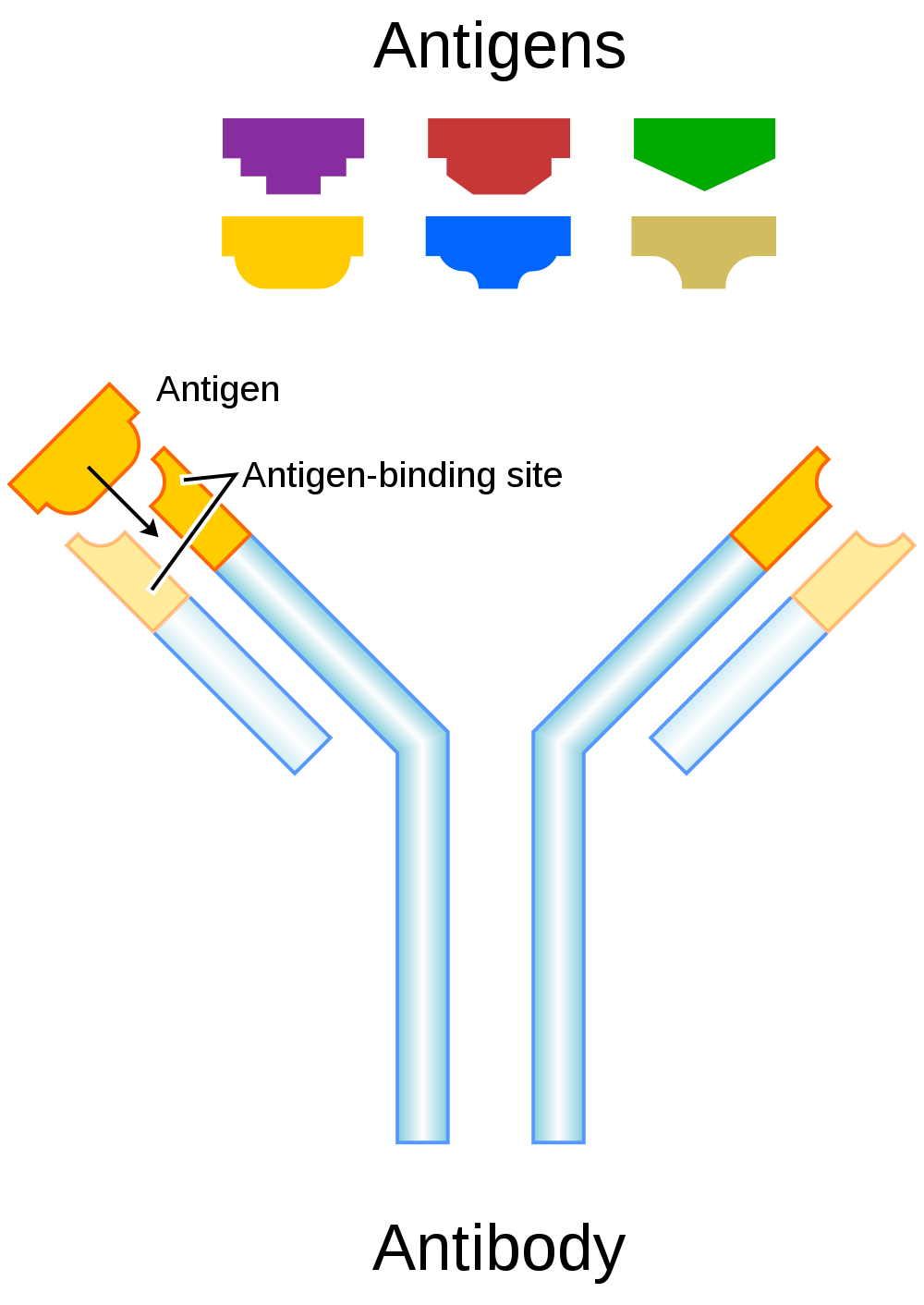

Antigens and Antibodies

Antigens — such as those on the red blood cells — are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self (produced by your own body) or non-self (not produced by your own body). Blood group antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins (proteins attached to chains of sugars), or glycolipids (lipids attached to chains of sugars), depending on the particular blood group system. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens. Antibodies are large, Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system that recognize and bind to non-self antigens. The analogy of a lock and key is often used to represent how an antibody and antigen fit together, as shown in the illustration below (Figure 6.5.2). When antibodies bind to antigens, it marks them for destruction by other immune system cells. Non-self antigens may enter your body on pathogens (such as bacteria or viruses), on foods, or on red blood cells in a blood transfusion from someone with a different blood type than your own. The last way is virtually impossible nowadays because of effective blood typing and screening protocols.

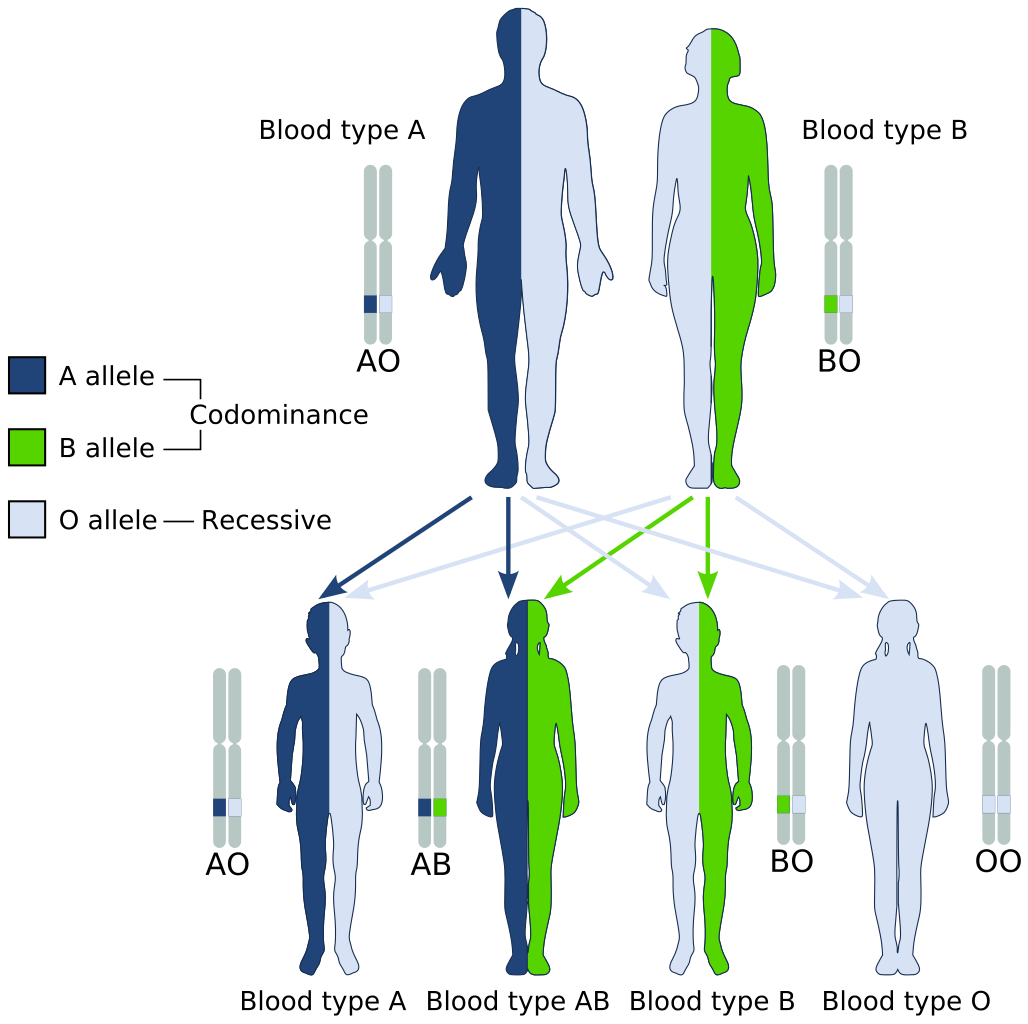

Genetics of Blood Type

An individual’s blood type depends on which alleles for a blood group system were inherited from their parents. Generally, blood type is controlled by alleles for a single gene, or for two or more very closely linked genes. Closely linked genes are almost always inherited together, because there is little or no recombination between them. Like other genetic traits, a person’s blood type is generally fixed for life, but there are rare instances in which blood type can change. This could happen, for example, if an individual receives a bone marrow transplant to treat a disease, such as leukemia. If the bone marrow comes from a donor who has a different blood type, the patient’s blood type may eventually convert to the donor’s blood type, because red blood cells are produced in bone marrow.

ABO Blood Group System

The ABO blood group system is the best known human blood group system. Antigens in this system are glycoproteins. These antigens are shown in the list below. There are four common blood types for the ABO system:

- Type A, in which only the A antigen is present.

- Type B, in which only the B antigen is present.

- Type AB, in which both the A and B antigens are present.

- Type O, in which neither the A nor the B antigen is present.

Genetics of the ABO System

The ABO blood group system is controlled by a single gene on chromosome 9. There are three common alleles for the gene, often represented by the letters A , B , and O. With three alleles, there are six possible genotypes for ABO blood group. Alleles A and B, however, are both dominant to allele O and codominant to each other. This results in just four possible phenotypes (blood types) for the ABO system. These genotypes and phenotypes are shown in Table 6.5.1.

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes

| ABO Blood Group System | |

| Genotype | Phenotype (Blood Type, or Group) |

| AA | A |

| AO | A |

| BB | B |

| BO | B |

| OO | O |

| AB | AB |

The diagram below (Figure 6.5.3) shows an example of how ABO blood type is inherited. In this particular example, the father has blood type A (genotype AO) and the mother has blood type B (genotype BO). This mating type can produce children with each of the four possible ABO phenotypes, although in any given family, not all phenotypes may be present in the children.

Medical Significance of ABO Blood Type

The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. If red blood cells containing a particular ABO antigen are transfused into a person who lacks that antigen, the person’s immune system will recognize the antigen on the red blood cells as non-self. Antibodies specific to that antigen will attack the red blood cells, causing them to agglutinate (or clump) and break apart. If a unit of incompatible blood were to be accidentally transfused into a patient, a severe reaction (called acute hemolytic transfusion reaction) is likely to occur, in which many red blood cells are destroyed. This may result in kidney failure, shock, and even death. Fortunately, such medical accidents virtually never occur today.

These antibodies are often spontaneously produced in the first years of life, after exposure to common microorganisms in the environment that have antigens similar to blood antigens. Specifically, a person with type A blood will produce anti-B antibodies, while a person with type B blood will produce anti-A antibodies. A person with type AB blood does not produce either antibody, while a person with type O blood produces both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Once the antibodies have been produced, they circulate in the plasma. The relationship between ABO red blood cell antigens and plasma antibodies is shown in Figure 6.5.4.

The antibodies that circulate in the plasma are for different antigens than those on red blood cells, which are recognized as self antigens.

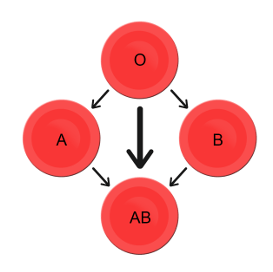

Which blood types are compatible and which are not? Type O blood contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, so people with type O blood can only receive type O blood. However, they can donate blood to people of any ABO blood type, which is why individuals with type O blood are called universal donors. Type AB blood contains neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies, so people with type AB blood can receive blood from people of any ABO blood type. That’s why individuals with type AB blood are called universal recipients. They can donate blood, however, only to people who also have type AB blood. These and other relationships between blood types of donors and recipients are summarized in the simple diagram to the right.

Geographic Distribution of ABO Blood Groups

The frequencies of blood groups for the ABO system vary around the world. You can see how the A and B alleles and the blood group O are distributed geographically on the maps in Figure 6.5.6.

- Worldwide, B is the rarest ABO allele, so type B blood is the least common ABO blood type. Only about 16 per cent of all people have the B allele. Its highest frequency is in Asia. Its lowest frequency is among the indigenous people of Australia and the Americas.

- The A allele is somewhat more common around the world than the B allele, so type A blood is also more common than type B blood. The highest frequencies of the A allele are in Australian Aborigines, the Lapps (Sami) of Northern Scandinavia, and Blackfoot Native Americans in North America. The allele is nearly absent among Native Americans in Central and South America.

- The O allele is the most common ABO allele around the world, and type O blood is the most common ABO blood type. Almost two-thirds of people have at least one copy of the O allele. It is especially common in Native Americans in Central and South America, where it reaches frequencies close to 100 per cent. It also has relatively high frequencies in Australian Aborigines and Western Europeans. Its frequencies are lowest in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Figure 6.5.6 Maps of populations that have the A, B and O alleles.

Evolution of the ABO Blood Group System

The geographic distribution of ABO blood type alleles provides indirect evidence for the evolutionary history of these alleles. Evolutionary biologists hypothesize that the allele for blood type A evolved first, followed by the allele for blood type O, and then by the allele for blood type B. This chronology accounts for the percentages of people worldwide with each blood group, and is also consistent with known patterns of early population movements.

The evolutionary forces of founder effect and genetic drift have no doubt played a significant role in the current distribution of ABO blood types worldwide. Geographic variation in ABO blood groups is also likely to be influenced by natural selection, because different blood types are thought to vary in their susceptibility to certain diseases. For example:

- People with type O blood may be more susceptible to cholera and plague. They are also more likely to develop gastrointestinal ulcers.

- People with type A blood may be more susceptible to smallpox and more likely to develop certain cancers.

- People with types A, B, and AB blood appear to be less likely to form blood clots that can cause strokes. However, early in our history, the ability of blood to form clots — which appears greater in people with type O blood — may have been a survival advantage.

- Perhaps the greatest natural selective force associated with ABO blood types is malaria. There is considerable evidence to suggest that people with type O blood are somewhat resistant to malaria, giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

Rhesus Blood Group System

Another well-known blood group system is the Rhesus (Rh) blood group system. The Rhesus system has dozens of different antigens, but only five main antigens (called D, C, c, E, and e). The major Rhesus antigen is the D antigen. People with the D antigen are called Rh positive (Rh+), and people who lack the D antigen are called Rh negative (Rh-). Rhesus antigens are thought to play a role in transporting ions across cell membranes by acting as channel proteins.

The Rhesus blood group system is controlled by two linked genes on chromosome 1. One gene, called RHD, produces a single antigen, antigen D. The other gene, called RHCE, produces the other four relatively common Rhesus antigens (C, c, E, and e), depending on which alleles for this gene are inherited.

Rhesus Blood Group and Transfusions

After the ABO system, the Rhesus system is the second most important blood group system in blood transfusions. The D antigen is the one most likely to provoke an immune response in people who lack the antigen. People who have the D antigen (Rh+) can be safely transfused with either Rh+ or Rh- blood, whereas people who lack the D antigen (Rh-) can be safely transfused only with Rh- blood.

Unlike anti-A and anti-B antibodies to ABO antigens, anti-D antibodies for the Rhesus system are not usually produced by sensitization to environmental substances. People who lack the D antigen (Rh-), however, may produce anti-D antibodies if exposed to Rh+ blood. This may happen accidentally in a blood transfusion, although this is extremely unlikely today. It may also happen during pregnancy with an Rh+ fetus if some of the fetal blood cells pass into the mother’s blood circulation.

Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

If a woman who is Rh- is carrying an Rh+ fetus, the fetus may be at risk. This is especially likely if the mother has formed anti-D antibodies during a prior pregnancy because of a mixing of maternal and fetal blood during childbirth. Unlike antibodies against ABO antigens, antibodies against the Rhesus D antigen can cross the placenta and enter the blood of the fetus. This may cause hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN), also called erythroblastosis fetalis, an illness in which fetal red blood cells are destroyed by maternal antibodies, causing anemia. This illness may range from mild to severe. If it is severe, it may cause brain damage and is sometimes fatal for the fetus or newborn. Fortunately, HDN can be prevented by preventing the formation of anti-D antibodies in the Rh- mother. This is achieved by injecting the mother with a medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.

Geographic Distribution of Rhesus Blood Types

The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system, as there is with the ABO system. The aboriginal inhabitants of the Americas and Australia originally had very close to 100 per cent Rh+ blood. The frequency of the Rh+ blood type is also very high in African populations, at about 97 to 99 per cent. In East Asia, the frequency of Rh+ is slightly lower, at about 93 to 99 per cent. Europeans have the lowest frequency of the Rh+ blood type at about 83 to 85 per cent.

What explains the population variation in Rhesus blood types? Prior to the advent of modern medicine, Rh+ positive children conceived by Rh- women were at risk of fetal or newborn death or impairment from HDN. This was an enigma, because presumably, natural selection would work to remove the rarer phenotype (Rh-) from populations. However, the frequency of this phenotype is relatively high in many populations.

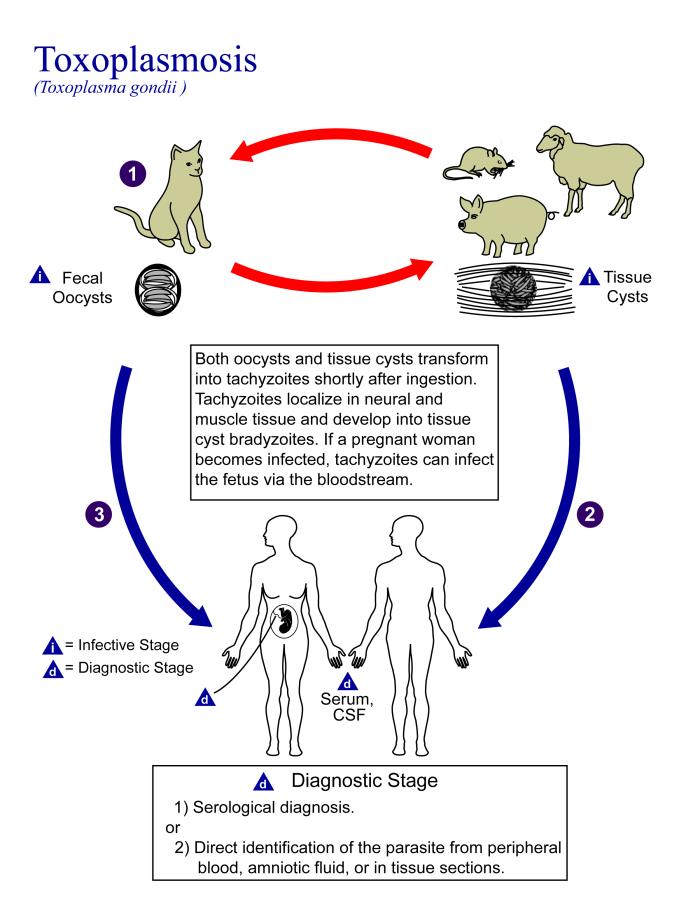

Recent studies have found evidence that natural selection may actually favor heterozygotes for the Rhesus D antigen. The selective agent in this case is thought to be toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, which is very common worldwide. You can see a life cycle diagram of the parasite in Figure 6.5.7. Infection by this parasite often causes no symptoms at all, or it may cause flu-like symptoms for a few days or weeks. Exposure to the parasite has been linked, however, to increased risk of mental disorders (such as schizophrenia), neurological disorders (such as Alzheimer’s), and other neurological problems, including delayed reaction times. One study found that people who tested positive for antibodies to the parasite were more than twice as likely to be involved in traffic accidents.

People who are heterozygous for the D antigen appear less likely to develop the negative neurological and mental effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection. This could help explain why both phenotypes (Rh+ and Rh-) are maintained in most populations. There are also striking geographic differences in the prevalence of toxoplasmosis worldwide, ranging from zero to 95 per cent in different regions. This could explain geographic variation in the D antigen worldwide, because its strength as a selective agent would vary with its prevalence.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Myth |

Reality |

| "Your nutritional needs can be determined by your ABO blood type. Knowing your blood type allows you to choose the appropriate foods that will help you lose weight, increase your energy, and live a longer, healthier life." | This idea was proposed in 1996 in a New York Times bestseller Eat Right for Your Type, by Peter D’Adamo, a naturopath. Naturopathy is a method of treating disorders that involves the use of herbs, sunlight, fresh air, and other natural substances. Some medical doctors consider naturopathy a pseudoscience. A major scientific review of the blood type diet could find no evidence to support it. In one study, adults eating the diet designed for blood type A showed improved health — but this occurred in everyone, regardless of their blood type. Because the blood type diet is based solely on blood type, it fails to account for other factors that might require dietary adjustments or restrictions. For example, people with diabetes — but different blood types — would follow different diets, and one or both of the diets might conflict with standard diabetes dietary recommendations and be dangerous. |

| "ABO blood type is associated with certain personality traits. People with blood type A, for example, are patient and responsible, but may also be stubborn and tense, whereas people with blood type B are energetic and creative, but may also be irresponsible and unforgiving. In selecting a spouse, both your own and your potential mate’s blood type should be taken into account to ensure compatibility of your personalities." | The belief that blood type is correlated with personality is widely held in Japan and other East Asian countries. The idea was originally introduced in the 1920s in a study commissioned by the Japanese government, but it was later shown to have no scientific support. The idea was revived in the 1970s by a Japanese broadcaster, who wrote popular books about it. There is no scientific basis for the idea, and it is generally dismissed as pseudoscience by the scientific community. Nonetheless, it remains popular in East Asian countries, just as astrology is popular in many other countries. |

6.5 Summary

- Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of antigens on the surface of red blood cells. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens.

- Antigens are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self or non-self. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens, leading to the destruction of cells bearing the antigens.

- The ABO blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by a single gene with three common alleles on chromosome 9. There are four possible ABO blood types: A, B, AB, and O. The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. People with type O blood are universal donors, and people with type AB blood are universal recipients.

- The frequencies of ABO blood type alleles and blood groups vary around the world. The allele for the B antigen is least common, and blood type O is the most common. The evolutionary forces of founder effect, genetic drift, and natural selection are responsible for the geographic distribution of ABO alleles and blood types. People with type O blood, for example, may be somewhat resistant to malaria, possibly giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

- The Rhesus blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by two genes with many alleles on chromosome 1. There are five common Rhesus antigens, of which antigen D is most significant. Individuals who have antigen D are called Rh+, and individuals who lack antigen D are called Rh-. Rh- mothers of Rh+ fetuses may produce antibodies against the D antigen in the fetal blood, causing hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN).

- The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system. This variation may be explained by natural selection that favors heterozygotes for the D antigen, because this genotype seems to be protected against some of the neurological consequences of the common parasitic infection toxoplasmosis.

6.5 Review Questions

- Define blood type and blood group system.

- Explain the relationship between antigens and antibodies.

- Identify the alleles, genotypes, and phenotypes in the ABO blood group system.

- Discuss the medical significance of the ABO blood group system.

- Compare the relative worldwide frequencies of the three ABO alleles.

- Give examples of how different ABO blood types vary in their susceptibility to diseases.

- Describe the Rhesus blood group system.

- Relate Rhesus blood groups to blood transfusions.

- What causes hemolytic disease of the newborn?

- Describe how toxoplasmosis may explain the persistence of the Rh- blood type in human populations.

- A woman is blood type O and Rh-, and her husband is blood type AB and Rh+. Answer the following questions about this couple and their offspring.

- What are the possible genotypes of their offspring in terms of ABO blood group?

- What are the possible phenotypes of their offspring in terms of ABO blood group?

- Can the woman donate blood to her husband? Explain your answer.

- Can the man donate blood to his wife? Explain your answer.

- Type O blood is characterized by the presence of O antigens — explain why this statement is false.

- Explain why newborn hemolytic disease may be more likely to occur in a second pregnancy than in a first.

6.5 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfZhb6lmxjk

Why do blood types matter? - Natalie S. Hodge, TED-Ed, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcZKbjYyOfE

How do blood transfusions work? - Bill Schutt, TED-Ed, 2020.

Attributes

Figure 6.5.1

Following the Blood Donation Trail by EJ Hersom/ USA Department of Defense is in the public domain. [Disclaimer: The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.]

Figure 6.5.2

Antibody by Fvasconcellos on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.3

ABO system codominance.svg, adapted by YassineMrabet (original "Codominant" image from US National Library of Medicine) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.4

ABO_blood_type.svg by InvictaHOG on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.5

Blood Donor and recipient ABO by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 6.5.6

- Map of Blood Group A by Muntuwandi at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

- Map of Blood Group B by Muntuwandi at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

- Map of Blood Group O by anthro palomar at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 6.5.7

Toxoplasma_gondii_Life_cycle_PHIL_3421_lores by Alexander J. da Silva, PhD/Melanie Moser, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Public Health Image Library (PHIL#3421) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes was created by Christine Miller.

References

Dean, L. (2005). Chapter 4 Hemolytic disease of the newborn. In Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2266/

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Toxoplasmosis [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/toxoplasmosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20356249

MedlinePlus. (2019, January 29). Hemolytic transfusion reaction [online article]. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_9&oldid=946440619

TED-Ed. (2015, June 29). Why do blood types matter? - Natalie S. Hodge. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfZhb6lmxjk&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, February 18). How do blood transfusions work? - Bill Schutt. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcZKbjYyOfE&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 10). Chromosome 1. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_1&oldid=955942444

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 20). Chromosome 9. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_9&oldid=946440619

The female sex hormone secreted mainly by the ovaries.

Image shows a diagram comparing a healthy nephron and its blood supply and one with diabetic nephropathy. The diseased one has blood vessels that look deformed and fragile.

Case Study: Drink and Flush

“Wow, this line for the restroom is long!” Shae says to Talia, anxiously bobbing from side to side to ease the pressure in her bladder. Talia nods and says, “It’s always like this at parties. It’s the alcohol.”

Shae and Talia are 21-year-old college students at a party. They — along with the other party guests — have been drinking alcoholic beverages over the course of the evening. As the night goes on, the line for the restroom has gotten longer and longer. You may have noticed this phenomenon if you have been to places where large numbers of people are drinking alcohol, like at the ballpark in Figure 16.1.2.

Shae says, “I wonder why alcohol makes you have to pee?” Talia says she learned about this in her Human Biology class. She tells Shae that alcohol inhibits a hormone that helps you retain water. Instead of your body retaining water, you urinate more out. This could lead to dehydration, so she suggests that after their trip to the restroom, they start drinking water, instead of alcohol.

For people who drink occasionally or moderately, this effect of alcohol on the excretory system — the system that removes wastes such as urine — is usually temporary. However, in people who drink excessively, alcohol can have serious, long-term effects on the excretory system. Heavy drinking on a regular basis can cause liver and kidney disease.

As you will learn in this chapter, the liver and kidneys are important organs of the excretory system, and impairment of the functioning of these organs can cause serious health consequences. At the end of the chapter, you will learn which hormone Talia was referring to. You will also learn some of the ways alcohol can affect the excretory system — both after the occasional drink, and in cases of excessive alcohol use and abuse.

Chapter Overview: Excretory System

In this chapter, you will learn about the excretory system, which rids the body of toxic waste products and helps maintain homeostasis. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The organs of the excretory system —including the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys — that eliminate waste and excess water from the body.

- How wastes are eliminated through sweat, feces, urine, and exhaled gases.

- How toxic substances in the blood are broken down by the liver.

- The urinary system, which includes the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra.

- The main function of the urinary system, which is to filter the blood and eliminate wastes, mineral ions, and excess water from the body in the form of urine.

- How the kidneys filter the blood, retain necessary substances, produce urine, and help maintain homeostasis (such as proper ion and water balance).

- How urine is stored, transported, and released from the body.

- Disorders of the urinary system, including bladder infections, kidney stones, polycystic kidney disease, urinary incontinence, and kidney damage caused by factors such as uncontrolled diabetes and high blood pressure.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- Which hormone do you think Talia was referring to? Remember that this hormone causes the urinary system to retain water and excrete less water out in urine.

- How and where does this hormone work?

- Long-term, excessive use of alcohol can affect the liver and kidneys. How do these two organs of excretion interact and work together?

Attributions

Figure 16.1.1

Gotta Pee [photo] by Jon-Eric Melsæter on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 16.1.2

Bathroom line up [photo] by Dorothy on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Image shows a diagram of the body and the locations where main lymph nodes are found. There are several regions along the midline of the body, a concentration in the neck, armpits, and groin.

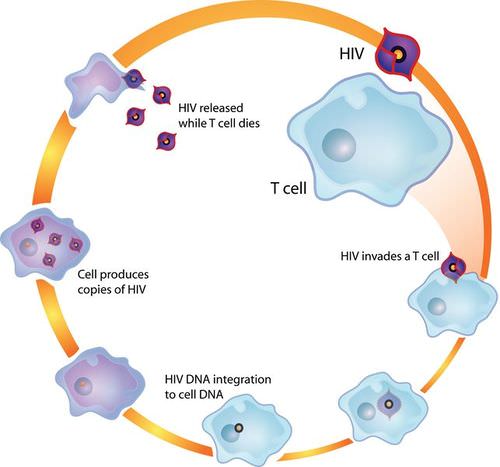

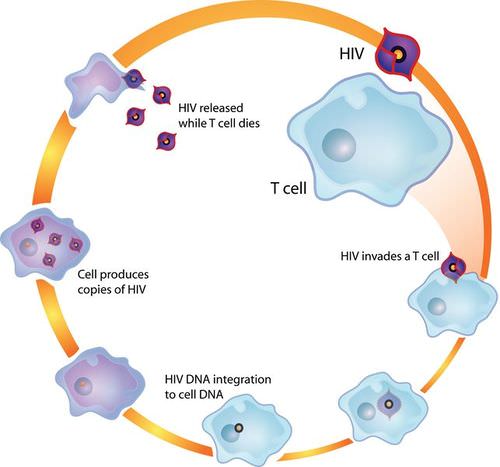

Image shows how HIV invades a helper t cell, inserts the viral DNA into the cell's DNA, reprograms the helper T cell to mass produce more HIV viruses, and then lyses to release all the newly made HIV into the host.

Image shows a photograph of an epipen.

Image shows a photograph of a finger with a paper cut.

A substance that is formed as the result of a chemical reaction.

The fusion of haploid gametes, egg and sperm, to form the diploid zygote.

Image shows to small children in a backyard wading pool. One adult is standing by the pool resting their foot on the edge and another adult is sitting nearby in a lawn chair.

Image shows a man sneezing against a black background. You can see all the the saliva and snot he has expelled in a cloud coming out of his mouth and nose. It is super gross.

Allergy Eyes

Eyes that are red, watery, and itchy are typical of an allergic reaction known as allergic rhinitis. Commonly called hay fever, allergic rhinitis is an immune system reaction, typically to the pollen of certain plants. Your immune system usually protects you from pathogens and keeps you well. However, like any other body system, the immune system itself can develop problems. Sometimes, it responds to harmless foreign substances as though they were pathogens. This is the basis of allergies like hay fever.

Allergies

An allergy is a disorder in which the immune system makes an inflammatory response to a harmless antigen. It occurs when the immune system is hypersensitive to an antigen in the environment that causes little or no response in most people. Allergies are strongly familial. Allergic parents are more likely to have allergic children, and those children’s allergies are likely to be more severe, which is evidence that there is a heritable tendency to develop allergies. Allergies are more common in children than adults, because many children outgrow their allergies by adulthood.

Allergens

Any antigen that causes an allergy is called an allergen. Common allergens are plant pollens, dust mites, mold, specific foods (such as peanuts or shellfish), insect stings, and certain common medications (such as aspirin and penicillin). Allergens may be inhaled or ingested, or they may come into contact with the skin or eyes. Symptoms vary depending on the type of exposure, and the severity of the immune system response. Some of the most common causes of allergies are shown in Figure 17.6.2: latex, pollen, dust mites, pet dander, insect stings and various foods. Inhaling pollen may cause symptoms of allergic rhinitis, such as sneezing and red itchy eyes. Insect stings may cause an itchy rash. This type of allergy is called contact dermatitis.

Figure 17.6.2 Common allergens include latex, pollen, dust mites, pet dander, insect stings, and foods.

Prevalence of Allergies

There has been a significant increase in the prevalence of allergies over the past several decades, especially in the rich nations of the world, where allergies are now very common disorders. In the developed countries, about 20% of people have or have had hay fever, another 20% have had contact dermatitis, and about 6% have food allergies. In the poorer nations of the world, on the other hand, allergies of all types are much less common.

One explanation for the rise in allergies in the developed world is the hygiene hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, people in developed countries live in relatively sterile environments because of hygienic practices and sanitation systems. As a result, people in these countries are exposed to fewer pathogens than their immune system evolved to cope with. To compensate, their immune system “keeps busy” by attacking harmless antigens in allergic responses.

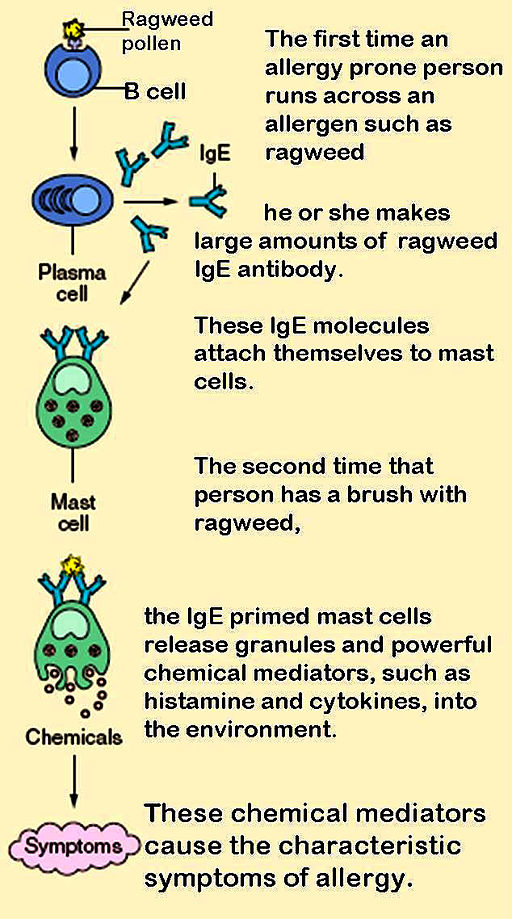

How Allergies Occur

The diagram in Figure 17.6.3 shows how an allergic reaction occurs. At the first exposure to an allergen, B cells are activated to form plasma cells that produce large amounts of antibodies to the allergen. These antibodies attach to leukocytes called mast cells. Subsequently, every time the person encounters the allergen again, the mast cells are already primed and ready to deal with it. The primed mast cells immediately release cytokines and histamines, which in turn cause inflammation and recruitment of leukocytes, among other responses. These responses are responsible for the signs and symptoms of allergies.

Treating Allergies

The symptoms of allergies can range from mild to life-threatening. Mild allergy symptoms are often treated with antihistamines. These are drugs that reduce or eliminate the effects of the histamines that produce allergy symptoms.

Treating Anaphylaxis

The most severe allergic reaction is a systemic reaction called anaphylaxis. This is a life-threatening response caused by a massive release of histamines. Many of the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis are shown in Figure 17.6.4. Some of them include a drop in blood pressure, changes in heart rate, shortness of breath, and swelling of the tongue and throat, which may threaten the patient with suffocation unless emergency treatment is given. People who have had anaphylactic reactions may carry an epinephrine autoinjector (widely known by its brand name EpiPen®) so they can inject themselves with epinephrine if they start to experience an anaphylactic response. The epinephrine helps control the immune reaction until medical care can be provided. Epinephrine constricts blood vessels to increase blood pressure, relaxes smooth muscles in the lungs to reduce wheezing and improve breathing, modulates heart rate, and works to reduce swelling that may otherwise block the airways.

Immunotherapy for Allergies

Another way to treat allergies is called immunotherapy, commonly called “allergy shots.” This approach may actually cure specific allergies, at least for several years if not permanently. It may be particularly beneficial for allergens that are difficult or impossible to avoid (such as pollen). First, however, patients must be tested to identify the specific allergens that are causing their allergies. As shown in Figure 17.6.5, this may involve scratching tiny amounts of common allergens into the skin, and then observing whether there is a localized reaction to any of them. Each allergen is applied in a different numbered location on the skin, so if there is a reaction — such as redness or swelling — the responsible allergens can be identified. Then, through periodic injections (usually weekly or monthly), patients are gradually exposed to larger and larger amounts of the allergens. Over time, generally from months to years, the immune system becomes desensitized to the allergens. This method of treating allergies is often effective for allergies to pollen or insect stings, but its usefulness for allergies to food is unclear.

Autoimmune Diseases

Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system fails to recognize the body’s own molecules as self. As a result, instead of ignoring the body’s healthy cells, it attacks them, causing damage to tissues and altering organ growth and function. Most often, B cells are at fault for autoimmune responses. They are generally the cells that lose tolerance for self. Why does this occur? Some autoimmune diseases are thought to be caused by exposure to pathogens that have antigens similar to the body’s own molecules. After this exposure, the immune system responds to body cells as though they were pathogens, as well.

Certain individuals are genetically susceptible to developing autoimmune diseases. These individuals are also more likely to develop more than one such disease. Gender is a risk factor for autoimmunity — females are much more likely than males to develop autoimmune diseases. This is likely due, in part, to gender differences in sex hormones.

At a population level, autoimmune diseases are less common where infectious diseases are more common. The hygiene hypothesis has been proposed to explain the inverse relationship between infectious and autoimmune diseases, as well as the prevalence of allergies. According to the hypothesis, without infectious diseases to “keep it busy,” the immune system may attack the body’s own cells instead.

Common Autoimmune Diseases

An estimated 15 million or more people worldwide have one or more autoimmune diseases. Two of the most common autoimmune diseases are type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis. In terms of the specific body cells that are attacked by the immune system, both are localized diseases. In the case of type I diabetes, the immune system attacks and destroys insulin-secreting islet cells in the pancreas. In the case of multiple sclerosis, the immune system attacks and destroys the myelin sheaths that normally insulate the axons of neurons and allow rapid transmission of nerve impulses.

Some relatively common autoimmune diseases are systemic — or body-wide — diseases. They include rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In these diseases, the immune system may attack and injure many tissues and organs. For example, as you can see in Figure 17.6.6, symptoms of SLE may involve the muscular, skeletal, integumentary, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems.

Treatment for Autoimmune Diseases

None of these common autoimmune diseases can be cured, although all of them have treatments that may help relieve symptoms and prevent some of the long-term damage they may cause. Traditional treatments for autoimmune diseases include immunosuppressive drugs to block the immune response, as well as anti-inflammatory drugs to quell inflammation. Hormone replacement may be another option. Type I diabetes, for example, is treated with injections of the hormone insulin, because islet cells in the pancreas can no longer secrete it.

Immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency occurs when the immune system is not working properly, generally because one or more components of the immune system are inactive. As a result, the immune system may be unable to fight off pathogens or cancers that a normal immune system would be able to resist. Immunodeficiency may occur for a variety of reasons.

Causes of Immunodeficiency

Dozens of rare genetic diseases can result in a defective immune system. This type of immunodeficiency is called primary immunodeficiency. One is born with one of these diseases, rather than acquiring it after birth. Probably the best known of these primary immunodeficiency diseases is severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). It is also known as “bubble boy disease,” because people with this disorder are extremely vulnerable to infectious diseases, and some of them have become well known for living inside a bubble that provides a sterile environment. SCID is most often caused by an X-linked recessive mutation that interferes with normal B cell and T cell production.

Other types of immunodeficiency are not present at birth, but are acquired due to experiences or exposures that occur after birth. Acquired immunodeficiency is called secondary immunodeficiency because it is secondary to some other event or exposure. Secondary immunodeficiency may occur for a number of different reasons:

- Some pathogens attack and destroy immune system cells. An example is the virus known as HIV, which attacks and destroys T cells.

- The immune system naturally becomes less effective as people get older. This age-related decline — called immunosenescence — generally begins around the age of 50 and worsens with increasing age. Immunosenescence is the reason older people are generally more susceptible to disease than younger people.

- The immune system may be damaged by another disorder, such as obesity, alcoholism, or the abuse of other drugs.

- In developing countries, malnutrition is the most common cause of immune system damage and immunodeficiency. Inadequate protein intake is especially damaging to the immune system. It can lead to impaired complement system activity, phagocyte malfunction, and lower-than-normal production of antibodies and cytokines.

- Certain medications can suppress the immune system. This is the intended effect of immunosuppressant drugs given to people with transplanted organs so they do not reject them. In many cases, however, immunosuppression is an unwanted side effect of drugs used to treat other disorders.

Focus on HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the most common cause of immunodeficiency in the world today. HIV infections of human hosts are a relatively recent phenomenon. Scientists think that the virus originally infected monkeys, but then jumped to human populations. most likely from a bite, probably sometime during the early to mid-1900s. This most likely occurred in West Africa, but the virus soon spread around the world. HIV was first identified by medical researchers in 1981. Since then, HIV has killed almost 40 million people worldwide, and its economic toll has also been enormous. The hardest hit countries are in Africa, where the virus has infected human populations the longest, and medications to control the virus are least available. In 2016, over 63,000 Canadians were living with HIV.

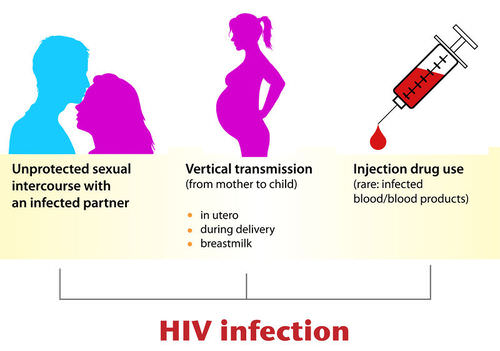

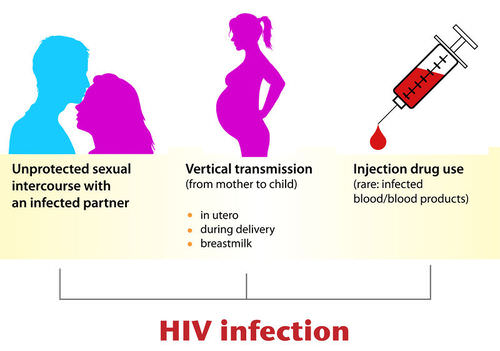

HIV Transmission

HIV is transmitted through direct contact of mucous membranes or body fluids such as blood, semen, or breast milk. As shown in Figure 17.6.7, transmission of the virus can occur through sexual contact or the use of contaminated hypodermic needles. It can also be transmitted from an infected mother’s blood during late pregnancy or childbirth, or through breast milk after birth. In the past, HIV was also transmitted occasionally through blood transfusions. Because donated blood is now screened for HIV, the virus is no longer transmitted this way.

HIV and the Immune System

HIV infects and destroys helper T cells, the type of lymphocytes that regulate the immune response. This process is illustrated in the diagram in Figure 17.6.8. The virus injects its own DNA into a helper T cell and uses the T cell’s “machinery” to make copies of itself. In the process, the helper T cell is destroyed, and the virus copies go on to infect other helper T cells. HIV is able to evade the immune system and keep destroying helper T cells by mutating frequently so its surface antigens keep changing, and by using the host cell’s membrane to hide its own antigens.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) may result from years of damage to the immune system by HIV. It occurs when helper T cells fall to a very low level and opportunistic diseases occur. Opportunistic diseases are infections and tumors that are rare, except in people with a damaged immune system. The diseases take advantage of the “opportunity” presented by people whose immune system cannot fight back. Opportunistic diseases are usually the direct cause of death for people with AIDS.

Treating HIV/AIDS

For patients who have access to HIV medications, infection with the virus is no longer the death sentence that it once was. By 1995, combinations of drugs called “highly active antiretroviral therapy” were developed. For some patients, these drugs can reduce the amount of virus they are carrying to undetectable levels. However, some level of virus always hides in the body’s immune cells, and it will multiply again if a patient stops taking the medications. Researchers are trying to develop drugs to kill these hidden viruses, as well. If their efforts are successful, it could end AIDS.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

EpiPens® and their sole manufacturer (pharmaceutical company Mylan) were featured in headlines in 2016, but not for a good reason. The media outburst was triggered by a drastic price hike in EpiPens® — and Mylan’s apparent greed.

EpiPens® are auto-injectable syringes preloaded with a measured dose of epinephrine, a drug that can rapidly stop a life-threatening anaphylactic response to an allergen. Using the device is easy and does not require any special training. The injector just needs to be jammed against the thigh, which can be done through clothing or on bare skin. Each year, doctors write millions of prescriptions for EpiPens®. Many people with severe allergies always carry two of the devices with them, just in case they experience anaphylaxis, although most of them never need to use them. Other people with severe allergies have literally had their lives saved multiple times by EpiPens® when they had anaphylactic reactions. Even when the devices haven’t been used, they must be replaced each year due to expiration of the epinephrine.

You might think that EpiPens® would be relatively inexpensive, given their life-saving potential. As recently as 2009, a two-pack of EpiPens® cost about $100. However, in just seven years, the cost of the same two-pack of EpiPens® skyrocketed by an incredible 400%! By 2016, the cost was $600 or more. Mylan apparently raised the price for the sole purpose of increasing profits. The company also raised prices significantly on many other drugs. The price hike in EpiPens® alone was certainly profitable. In 2015, the sale of EpiPens® earned Mylan $1 billion. Mylan’s CEO took home almost $19 million the same year, which was an increase of more than 600% over her prior salary.

News coverage of the price hike in EpiPens® began in the summer of 2016 after a price increase in May of that year. Both private citizens and elected officials expressed outrage over the price increase, especially when coupled with the gluttonous profits of the company and its CEO. By late August, Mylan responded to the backlash by offering discount coupons for EpiPens®. A few days later, the company promised to introduce a cheaper, generic version of the device. Analysts quickly determined that selling a generic version would allow Mylan to make more money on the product than reducing the price of the name-brand device, which they still declined to do. By September of 2016, Mylan was being investigated for antitrust violations related to sales of EpiPens® to public schools in New York City.

The Mylan/EpiPen® story may still be making the news. But whatever its outcome, the story has already added fuel to public and private debates about important ethical issues — issues such as the excessive costs of life-saving drugs and the huge profits of big pharma. What is the most recent news on EpiPens® and Mylan? If you are interested, you can check the headlines online to find out. What are your views on the ethical issues they raise?

17.6 Summary

- An allergy is a disorder in which the immune system makes an inflammatory response to a harmless antigen. Any antigen that causes allergies is called an allergen. Common allergens include pollen, dust mites, mold, specific foods (such as peanuts), insect stings, and certain medications (such as aspirin).

- The prevalence of allergies has been increasing for decades, especially in developed countries, where they are much more common than in developing countries. The hygiene hypothesis posits that this has occurred because humans evolved to cope with more pathogens than we now typically face in our relatively sterile environments in developed countries. As a result, the immune system “keeps busy” by attacking harmless antigens.

- Allergies occur when B cells are first activated to produce large amounts of antibodies to an otherwise harmless allergen, and the antibodies attach to mast cells. On subsequent exposures to the allergen, the mast cells immediately release cytokines and histamines that cause inflammation.

- Mild allergy symptoms are frequently treated with antihistamines that counter histamines and reduce allergy symptoms. A severe systemic allergic reaction, called anaphylaxis, is a medical emergency that is usually treated with injections of epinephrine. Immunotherapy for allergies involves injecting increasing amounts of allergens to desensitize the immune system to them.

- Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system fails to recognize the body’s own molecules as self and attacks them, causing damage to tissues and organs. A family history of autoimmunity and female gender are risk factors for autoimmune diseases.

- In some autoimmune diseases, such as type I diabetes, the immune system attacks and damages specific body cells. In other autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, many different tissues and organs may be attacked and injured. Autoimmune diseases generally cannot be cured, but their symptoms can often be managed with drugs or other treatments.

- Immunodeficiency occurs when the immune system is not working properly, generally because one or more of its components are inactive. As a result, the immune system is unable to fight off pathogens or cancers that a normal immune system would be able to resist.

- Primary immunodeficiency is present at birth and caused by rare genetic diseases. An example is severe combined immunodeficiency. Secondary immunodeficiency occurs because of some event or exposure experienced after birth. Possible causes include aging, certain medications, infections with pathogens, and other disorders, such as obesity or malnutrition.

- The most common cause of immunodeficiency in the world today is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which infects and destroys helper T cells. HIV is transmitted through mucous membranes or body fluids. The virus may eventually lead to such low levels of helper T cells that opportunistic infections occur. When this happens, the patient is diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Medications can control the multiplication of HIV in the human body — but they don't eliminate the virus completely.

17.6 Review Questions

-

- How does immunotherapy for allergies work?

- What are autoimmune diseases?

- Identify two risk factors for autoimmune diseases.

- Autoimmune diseases may be specific to particular tissues, or they may be systemic. Give an example of each type of autoimmune disease.

- What is immunodeficiency? Compare and contrast primary and secondary immunodeficiency. Give an example of each.

- What is the most common cause of immunodeficiency in the world today? How does this affect the immune system?

- Distinguish between HIV and AIDS.

17.6 Explore More

https://youtu.be/-q7Fz7NIMWM

Why do people have seasonal allergies? - Eleanor Nelsen, TED-Ed, 2016.

https://youtu.be/0TipTogQT3E

Why it’s so hard to cure HIV/AIDS - Janet Iwasa, TED-Ed, 2015.

https://youtu.be/pJa6KVLwl9U

The Boy in the Bubble | Retro Report | The New York Times, 2015.

https://youtu.be/Mjr9h_QmdeM

Why Are Peanut Allergies Becoming So Common? Seeker, 2014.

https://youtu.be/RiMSmDBvgto

What Are Tonsil Stones? | Gross Science, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 17.6.1

Oedema by Championswimmer on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain).

Figure 17.6.2

- Medical (latex) gloves from pngimg.com is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) license.

- House dust mites (5247996458) by Gilles San Martin from Namur, Belgium on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en) license.

- Honey bee macro by Karunakar Rayker on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

- Peanuts by Karolina Grabowska on Pexels is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).