18.7 Functions of the Female Reproductive System

Waiting Expectantly

A mother-to-be waits patiently for her baby to grow as her belly gradually swells. Reproduction is all about making babies, and the female reproductive system is specialized for this purpose. Its functions include producing female gametes called ova, secreting female sex hormones (such as estrogen), providing a site for fertilization, gestating a fetus if fertilization occurs, giving birth to a baby, and breastfeeding a baby after birth. The only thing missing is sperm.

Ova Production

At birth, a female’s ovaries contain all the ova she will ever produce, which may include a million or more ova. The ova don’t start to mature, however, until she enters puberty and attains sexual maturity. After that, one ovum typically matures each month, and is released from an ovary. This continues until a woman reaches menopause (cessation of monthly periods), typically by age 52. By then, viable eggs may be almost depleted, and hormone levels can no longer support the monthly cycle. During the reproductive years, which of the two ovaries releases an egg in a given month seems to be a matter of chance. Occasionally, both ovaries will release an egg at the same time. If both eggs are fertilized, the offspring are fraternal twins (dizygotic, or “two-zygote,” twins), and they are no more alike genetically than non-twin siblings.

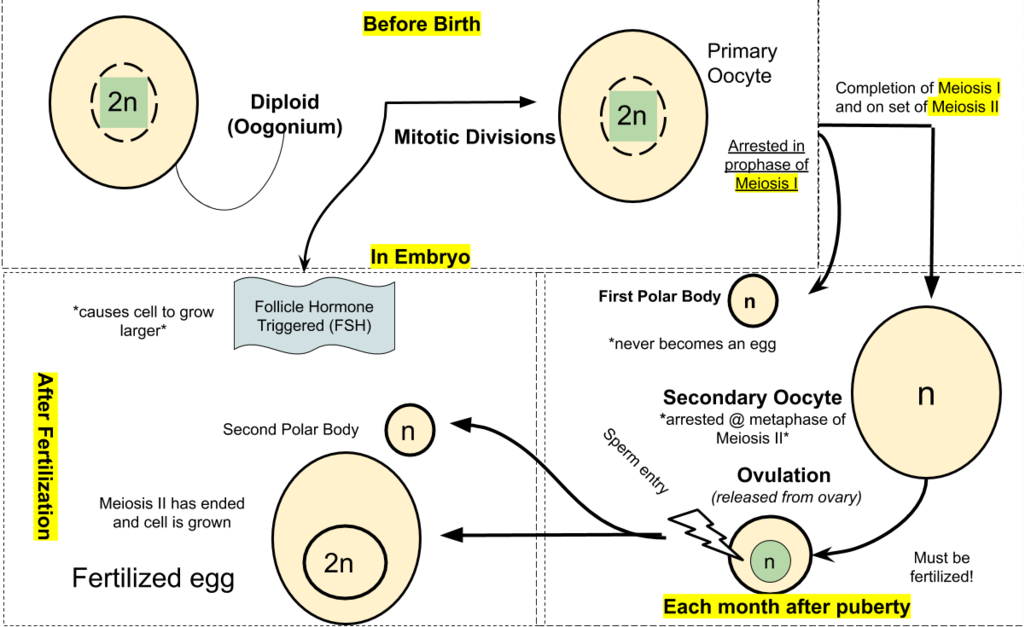

Oogenesis

The process of producing ova in the ovaries of a female fetus is called oogenesis. Ova are haploid gametes, and their production occurs in several steps that involve different types of cells, as summarized in Figure 18.7.2. Oogenesis is completed long before birth. It occurs when diploid germ cells called oogonia (singular, oogonium) undergo mitosis. Each such cell division produces two diploid daughter cells. One is called the primary oocyte, and the other is retained to help maintain a reserve of oogonia. The primary oocyte, in turn, starts to go through the first cell division of meiosis (meiosis I). However, it does not complete meiosis I until much later. Instead, it remains in a resting state, nestled within a tiny, immature follicle in the ovary until the female goes through puberty.

Maturation of a Follicle

Beginning in puberty, about once a month, one of the follicles in an ovary undergoes maturation, and an egg is released. As the follicle matures, it goes through changes in the numbers and types of its cells, as shown in Figure 18.7.2. The primary oocyte within the follicle also resumes meiosis. It completes meiosis I, which began long before birth, to form a secondary oocyte and a smaller cell, called the first polar body. Both the secondary oocyte and the first polar body are haploid cells. The secondary oocyte has most of the cytoplasm from the primary oocyte and is much larger than the first polar body, which soon disintegrates and disappears. The secondary oocyte begins meiosis II, but only completes it if the egg is fertilized.

Release of an Egg

It typically takes 12 to 14 days for a follicle to mature in an ovary, and for the secondary oocyte to form. Then, the follicle bursts open and the ovary ruptures, releasing the secondary oocyte from the ovary. This event is called ovulation. The now-empty follicle starts to change into a structure called a corpus luteum. The expelled secondary oocyte is usually swept into the nearby oviduct by its waving, fringe-like fimbriae.

Uterine Changes

While the follicle is maturing in the ovary, the uterus is also undergoing changes to prepare it for an embryo if fertilization occurs. For example, the endometrium gets thicker and becomes more vascular. Around the time of ovulation, the cervix undergoes changes that help sperm reach the ovum to fertilize it. The cervical canal widens, and cervical mucus becomes thinner and more alkaline. These changes help promote the passage of sperm from the vagina into the uterus and make the environment more hospitable to sperm.

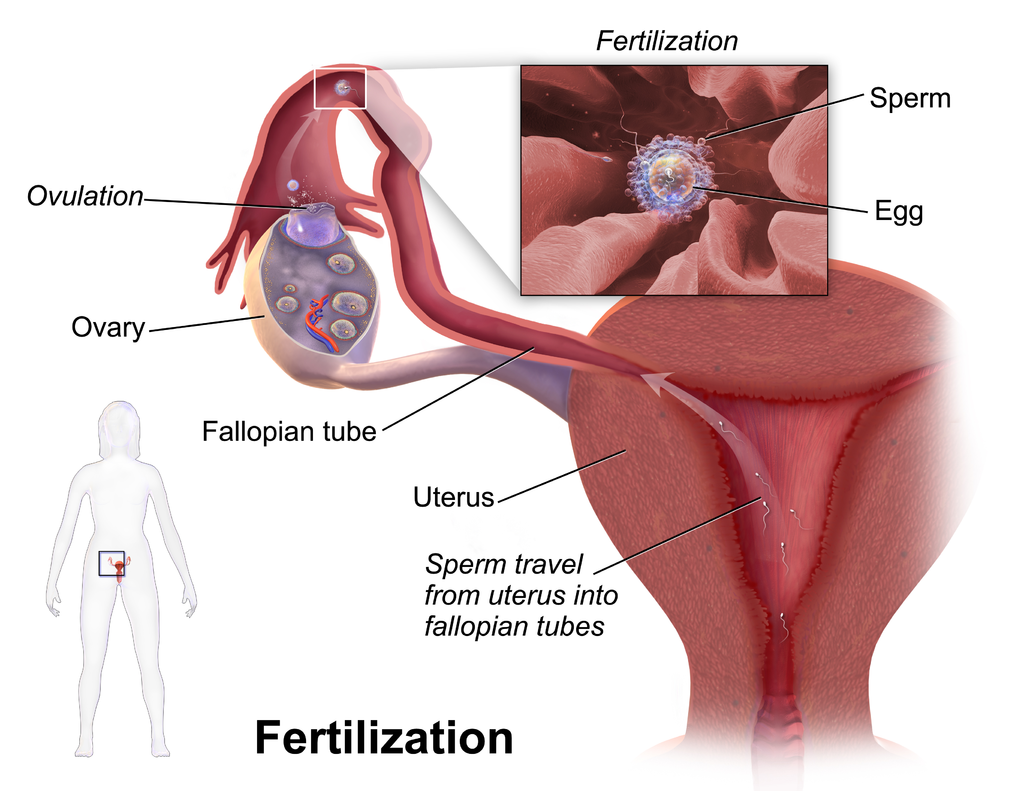

Fertilization — or Not

Fertilization of an ovum by a sperm normally occurs in an oviduct, most often in the part of the tube that passes above the ovary (see Figure 18.7.3). In order for fertilization to occur, sperm must “swim” from the vagina where they are deposited, through the cervical canal to the uterus, and then through the body of the uterus to one of the oviducts. Once sperm enter a oviduct, tubular fluids help carry them through the tube toward the secondary oocyte at the other end. The secondary oocyte also functions to promote fertilization. It releases molecules that guide the sperm and allow the surface of the ovum to attach to the surface of the sperm. The ovum can then absorb the sperm, allowing fertilization to occur.

If Fertilization Occurs

If the secondary oocyte is fertilized by a sperm as it passes through the oviduct, the secondary oocyte quickly completes meiosis II, forming a diploid zygote and another polar body. This second polar body, like the first, normally breaks down and disappears. The zygote then continues the journey through the oviduct to the uterus, during which it undergoes several mitotic cell divisions. By the time it reaches the uterus up to five days after fertilization, it consists of a ball of cells called a blastocyst. Within another day or two, the blastocyst implants itself in the endometrium lining the uterus, and gestation begins.

If Fertilization Does Not Occur

What happens if the secondary oocyte is not fertilized by a sperm as it passes through the oviduct? It continues on its way to the uterus without ever completing meiosis II. It is likely to disintegrate within a few days while still in the oviduct. Any remaining material will be shed from the woman’s body during the next menstrual period.

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Pregnancy is the carrying of one or more offspring from fertilization until birth. This is one of the major functions of the female reproductive system. It involves virtually every other body system including the cardiovascular, urinary, and respiratory systems, to name just three. The maternal organism plays a critical role in the development of the offspring. She must provide all the nutrients and other substances needed for normal growth and development of the offspring, and she must also remove the wastes excreted by the offspring. Most nutrients are needed in greater amounts by a pregnant woman to meet fetal needs, but some are especially important, including folic acid, calcium, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids. A healthy diet (see photo in Figure 18.7.4), along with prenatal vitamin supplements, is recommended for the best pregnancy outcome. A pregnant woman should also avoid ingesting substances (such as alcohol) that can damage the developing offspring, especially early in the pregnancy when all of the major organs and organ systems are forming.

Trimesters of Pregnancy

When counted from the first day of the last menstrual period, the average duration of pregnancy is about 40 weeks (38 weeks when counted from the time of fertilization), but a pregnancy that lasts between 37 and 42 weeks is still considered within the normal range. From the point of view of the maternal organism, the total duration of pregnancy is typically divided into three periods, called trimesters, each of which lasts about three months. This division of the total period of gestation is useful for summarizing the typical changes a woman can expect during pregnancy. From the point of view of the developing offspring, however, the major divisions are different. They are the embryonic and fetal stages. The offspring is called an embryo from the time it implants in the uterus through the first eight weeks of life. After that, it is called a fetus for the duration of the pregnancy.

First Trimester

The first trimester begins at the time of fertilization and lasts for the next 12 weeks. Even before she knows she is pregnant, a woman in the first trimester is likely to experience signs and symptoms of pregnancy. She may notice a missed menstrual period, and she may also experience tender breasts, increased appetite, and more frequent urination. Many women also experience nausea and vomiting in the first trimester. This is often called “morning sickness,” because it commonly occurs in the morning, but it may occur at any time of day. Some women may lose weight during the first trimester because of morning sickness.

Second Trimester

The second trimester occurs during weeks 13 to 28 of pregnancy. A pregnant woman may feel more energized during this trimester. If she experienced nausea and vomiting during the first trimester, these symptoms often subside during the second trimester. Weight gain starts occurring during this trimester, as well. By about week 20, the fetus is getting large enough that the mother can feel its movements. The photo in Figure 18.7.5 shows a pregnant woman at week 26, toward the end of the second trimester. (For comparison, the same woman is shown on the right at the end of the third trimester.)

Third Trimester

The third trimester occurs during weeks 29 through birth (at about 40 weeks). During this trimester, the uterus expands rapidly, making up a larger and larger portion of the woman’s abdomen. Weight gain is also more rapid. During the third trimester, the movements of the fetus become stronger and more frequent, and they may become disruptive to the mother. As the fetus grows larger, its weight and the space it takes up may lead to symptoms in the mother such as back pain, swelling of the lower extremities, more frequent urination, varicose veins, and heartburn. By the end of the third trimester, the woman’s abdomen often will transform in shape as it drops, due to the fetus turning to a downward position before birth so its head rests on the cervix. This relieves pressure on the upper abdomen, but reduces bladder capacity and increases pressure on the pelvic floor and rectum.

Childbirth

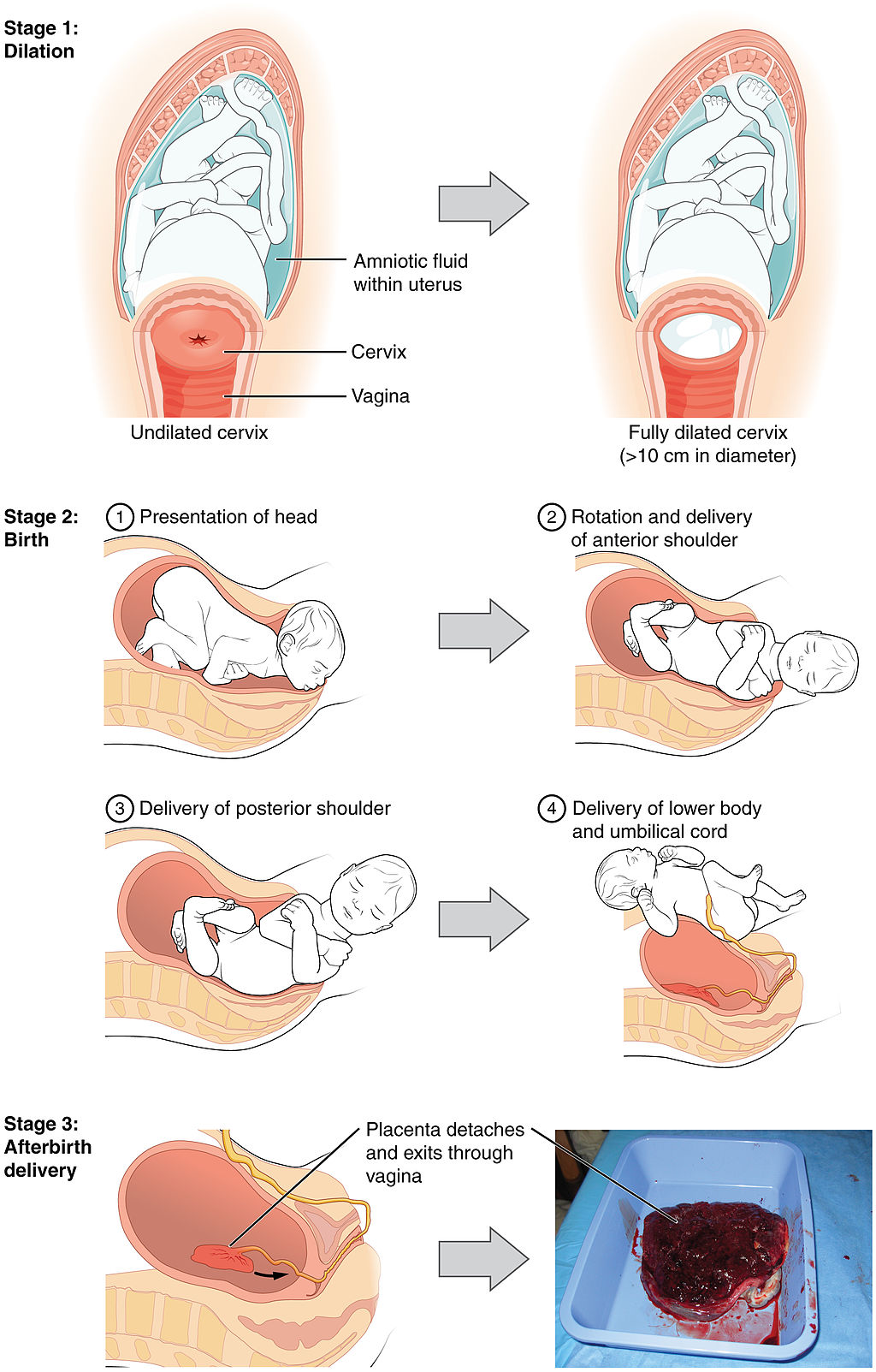

Near the time of birth, the amniotic sac — a fluid-filled membrane that encloses the fetus within the uterus — breaks in a gush of fluid. This is commonly called “breaking water.” Labour usually begins within a day of this event, although it may begin prior to it. Labour is the general term for the process of childbirth in which regular uterine contractions push the fetus and placenta out of the body. Labour can be divided into three stages, which are illustrated in Figure 18.7.6: dilation, birth, and afterbirth.

- During the dilation stage of labour, uterine contractions begin and become increasingly frequent and intense. The contractions push the baby’s head (most often) against the cervix, causing the cervical canal to dilate, or become wider. This lasts until the cervical canal has dilated to about 10 cm (almost 4 in.) in width, which may take 12 to 20 hours — or even longer. The cervical canal must be dilated to this extent in order for the baby’s head to fit through it.

- During birth, the baby descends (usually headfirst) through the cervical canal and vagina, and into the world outside. This is the stage when the mother generally starts bearing down during the contractions to help push out the fetus. This stage may last from about 20 minutes to two hours or more. Usually, within a minute or less of birth, the umbilical cord is cut, so the baby is no longer connected to the placenta.

- During the afterbirth stage, the placenta is delivered. This stage may last from a few minutes to a half hour.

Breastfeeding

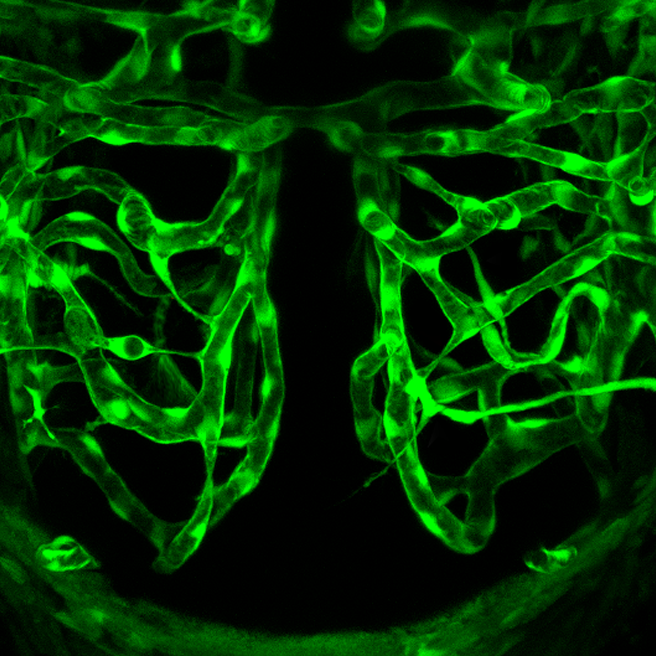

Although the breasts are not classified as organs of the reproductive system, they nonetheless may play an important role in reproduction. The physiological function of the female breast is lactation, or the production of breast milk to feed an infant. This function is illustrated in Figure 18.7.7. Besides nutrients, breast milk provides hormones, antibodies, and other substances that help ensure a healthy start after birth.

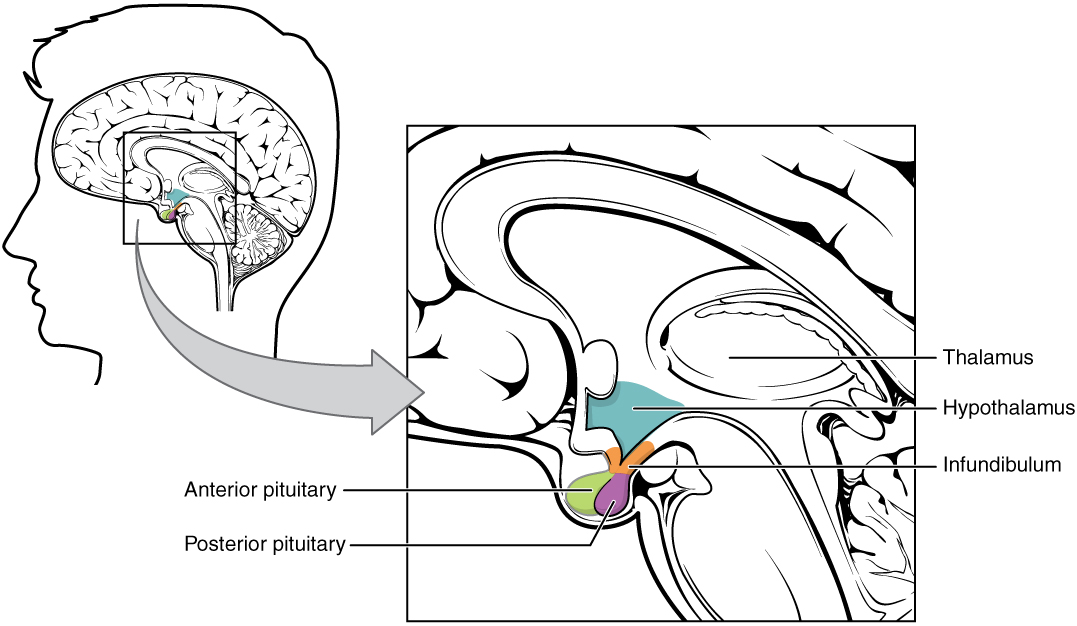

The Figure 18.7.7 (above) shows the correct way for an infant to suck the breast to stimulate the letdown of milk from the mammary glands (lips flanged, baby’s mouth on the nipple symmetrically). The letdown of milk when an infant sucks at the breast is one of the few examples of a positive feedback loop in the human organism. Sucking causes a release from the posterior pituitary gland of the hypothalamic hormone oxytocin. Oxytocin, in turn, causes milk to flow from the alveoli in the breasts where milk is produced, through the milk ducts, and into the milk sacs behind the areola. You can trace this route of milk through the breast in Figure 18.7.8. The baby can suck the milk out of the sacs through the nipple, where they converge. The release of milk stimulates the baby to continue sucking, which in turn keeps the milk flowing. Oxytocin is also an important hormone for maternal-child attachment.

Female Sex Hormones

Female reproduction could not occur without sex hormones released by the ovaries. These hormones include estrogen and progesterone.

Estrogen

Before birth, estrogen is released by the gonads in female fetuses and leads to the development of female reproductive organs. At puberty, estrogen levels rise and are responsible for sexual maturation, and for the development of female secondary sex characteristics (such as breasts). Estrogen is also needed to help regulate the menstrual cycle and ovulation throughout a woman’s reproductive years. Estrogen is produced primarily by follicular cells in the ovaries. During pregnancy, estrogen is also produced by the placenta. There are actually three forms of estrogen in the human female: estradiol, estriol, and estrone.

- Estradiol is the predominant form of estrogen during the reproductive years. It is also the most potent form of estrogen.

- Estriol is the predominant form of estrogen during pregnancy. It is also the weakest form of estrogen.

- Estrone is the predominant form of estrogen in post-menopausal women. It is intermediate in strength between the other two forms of estrogen.

Progesterone

Progesterone stands for “pro-gestational hormone.” It is synthesized and secreted primarily by the corpus luteum in the ovary. Progesterone plays many physiological roles, but is best known for its role during pregnancy. In fact, it is sometimes called the “hormone of pregnancy.” Among other functions, progesterone prepares the uterus for pregnancy each month by building up the uterine lining. If a pregnancy occurs, progesterone helps maintain the pregnancy in a number of ways, such as decreasing the maternal immune response to the genetically different embryo, and decreasing the ability of uterine muscle tissue to contract. Progesterone also prepares the mammary glands for lactation during pregnancy, and withdrawal of progesterone after birth is one of the triggers of milk production.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

There are many myths associated with pregnancy. Most are harmless, but some may put the pregnant woman or fetus at risk. As always, knowledge is power.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

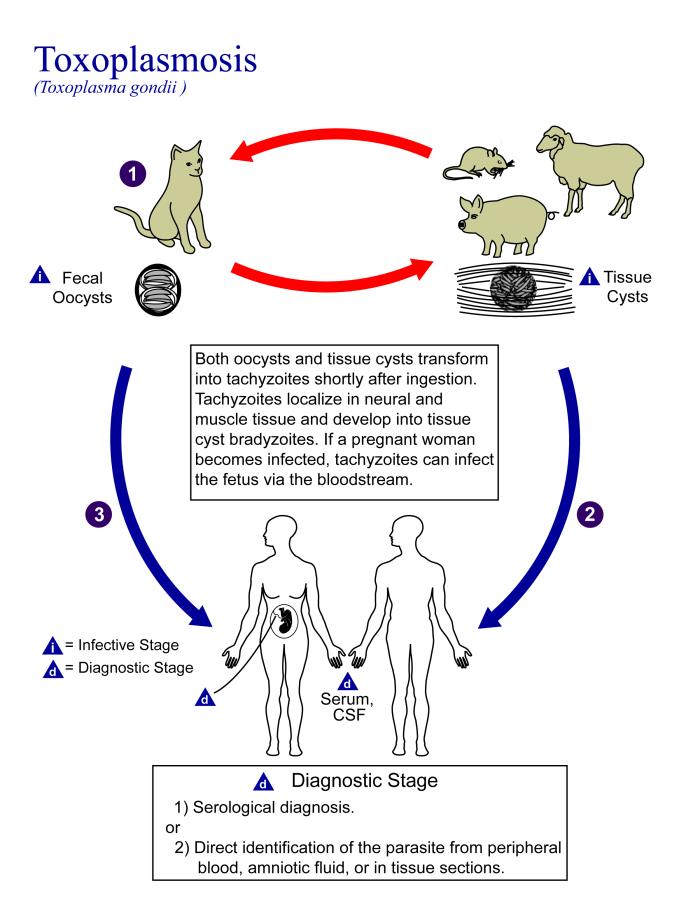

| “You should avoid petting your cat during pregnancy.” | Cat feces may be contaminated with microscopic parasites that can cause a disease called toxoplasmosis. Pregnant women who contract this disease are at risk of stillbirth, miscarriage, or giving birth to an infant with serious health problems. Pregnant women should not have contact with a cat’s litter box or feces, but petting a cat poses no real risk of infection. |

| “You should not dye your hair during pregnancy, because the chemicals can harm the fetus.” | Whereas some chemicals (such as certain pesticides) have been shown to be associated with birth defects, there is no evidence that using hair dye during pregnancy increases this risk. |

| “A pregnant woman needs to eat for two, so she should double her pre-pregnancy caloric intake.” | Throughout a typical pregnancy, a woman needs only about 300 extra calories per day, on average, to support her growing fetus. Most of the extra calories are needed during the last trimester, when the fetus is growing most rapidly. Doubling her caloric intake during pregnancy is likely to cause too much weight gain, which can be detrimental to her baby. Babies that weigh much more than the average 7.5 pounds (3.4 kg) at birth are more likely to develop diabetes and obesity in later life. |

| “Women who are pregnant have strange food cravings, such as ice cream with pickles.” | Some women do have food cravings during pregnancy, but they are not necessarily cravings for strange foods or unusual food combinations. For example, a pregnant woman might crave starchy foods for a few weeks, or she may be put off by certain foods that she loved before pregnancy. |

| “A pregnant woman has skin that glows.” | Pregnancy can actually be hard on the skin and its appearance. Besides stretch marks on the abdomen and breasts, pregnancy may lead to spider veins, varicose veins, new freckles, darkening of moles, and acne flare-ups. In addition, as many as 75 per cent of pregnant women experience chloasma, which is the emergence of blotchy brown patches of skin on the face due to high estrogen levels. Chloasma is often referred to as the “mask of pregnancy.” |

18.7 Summary

- Oogenesis is the process of producing ova in the ovaries of a female fetus. Oogenesis begins when a diploid oogonium divides by mitosis to produce a diploid primary oocyte. The primary oocyte begins meiosis I and then remains at this stage in an immature ovarian follicle until after birth. By birth, a female’s ovaries contain all the eggs she will ever produce, numbering at least a million.

- After puberty, one follicle a month matures, and its primary oocyte completes meiosis I to produce a secondary oocyte, which begins meiosis II. During ovulation, the mature follicle bursts open, and the secondary oocyte leaves the ovary and enters an oviduct.

- While a follicle is maturing in an ovary each month, the endometrium in the uterus is building up to prepare for an embryo. Around the time of ovulation, cervical mucus becomes thinner and more alkaline to help sperm reach the secondary oocyte.

- If the secondary oocyte is fertilized by a sperm, it quickly completes meiosis II and forms a diploid zygote, which will continue through the oviduct. The zygote will go through multiple cell divisions before reaching and implanting in the uterus. If the secondary oocyte is not fertilized, it will not complete meiosis II, and it will soon disintegrate.

- Pregnancy is the carrying of one or more offspring from fertilization until birth. The maternal organism must provide all the nutrients and other substances needed by the developing offspring, and also remove its wastes. She should also avoid exposures that could potentially damage the offspring, especially early in the pregnancy when organ systems are developing.

- The average duration of pregnancy is 40 weeks (from the first day of the last menstrual period) and is divided into three trimesters of about three months each. Each trimester is associated with certain events and conditions that a pregnant woman may expect, such as morning sickness during the first trimester, feeling fetal movements for the first time during the second trimester, and rapid weight gain in both fetus and mother during the third trimester.

- Labour, which is the general term for the birth process, usually begins around the time the amniotic sac breaks and its fluid leaks out. Labour occurs in three stages: dilation of the cervix, birth of the baby, and delivery of the placenta (afterbirth).

- The physiological function of female breasts is lactation, or the production of breast milk to feed an infant. Sucking on the breast by the infant stimulates the release of the hypothalamic hormone oxytocin from the posterior pituitary, which causes the flow of milk. The release of milk stimulates the baby to continue sucking, which in turn keeps the milk flowing. This is one of the few examples of positive feedback in the human organism.

- The ovaries produce female sex hormones, including estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen is responsible for sexual differentiation before birth, as well as for sexual maturation and the development of secondary sex characteristics at puberty. It is also needed to help regulate the menstrual cycle and ovulation after puberty and until menopause. Progesterone prepares the uterus for pregnancy each month during the menstrual cycle, and helps maintain the pregnancy if fertilization occurs.

18.7 Review Questions

-

- What is pregnancy, and what is the role of the maternal organism in pregnancy?

- What is the average duration of pregnancy? Identify the trimesters of pregnancy.

- Define labour. What event is often a sign that labour will soon begin?

- Identify the stages of labour.

- Describe the physiological function of female breasts. How is this function controlled?

- Identify the functions of the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone.

- Describe the roles of the cervix in fertilization and childbirth.

18.7 Explore More

Pregnancy 101 | National Geographic, 2018.

How do pregnancy tests work? – Tien Nguyen, TED-Ed, 2015.

Fertilization, Nucleus Medical Media, 2013.

The science of milk – Jonathan J. O’Sullivan, TED-Ed, 2017.

Attributions

Figure 18.7.1

Pregnant by Mustafa Omar on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 18.7.2

Oogenesis by Acedatrey2 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 18.7.3

Blausen_0404_Fertilization by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 18.7.4

Prenatal Diet/ Milch-Jogurt-Früchte by Peggy Greb, Agricultural Research Service (USDA) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 18.7.5

Pregnancy_comparison by Maustrauser at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 18.7.6

Stages_of_Childbirth-02 by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) license.

Figure 18.7.7

Childhood: breast feeding [photo] by Jan Kopřiva on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 18.7.8

Breast-Diagram by Women’s Health (NCI/ NIH) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 28.21 Stages of childbirth [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 28.4). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/28-4-maternal-changes-during-pregnancy-labor-and-birth

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436

National Geographic. (2018, December 20). Pregnancy 101 | National Geographic. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XEfnq4Q4bfk&feature=youtu.be

Nucleus Medical Media. (2013, January 31). Fertilization. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_5OvgQW6FG4&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed, (2015, July 7). How do pregnancy tests work? – Tien Nguyen. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOfWTscU8YM&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2017, January 31). The science of milk – Jonathan J. O’Sullivan. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xmNzUEmFZMg&feature=youtu.be

A mature haploid male or female germ cell which is able to unite with another of the opposite sex in sexual reproduction to form a zygote.

The female sex hormone secreted mainly by the ovaries.

The fusion of haploid gametes, egg and sperm, to form the diploid zygote.

As per caption.

A biological process which converts sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose into cellular energy, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide as by-products.

A testable proposed explanation for a phenomenon.

http://humanbiology.pressbooks.tru.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/06/human-heartbeat-daniel_simon.mp3

Lub, Dub

Lub dub, lub dub, lub dub... That’s how the sound of a beating heart is typically described. Those are also the only two sounds that should be audible when listening to a normal, healthy heart through a stethoscope, as in Figure 14.3.1. If a doctor hears something different from the normal lub dub sounds, it’s a sign of a possible heart abnormality. What causes the heart to produce the characteristic lub dub sounds? Read on to find out.

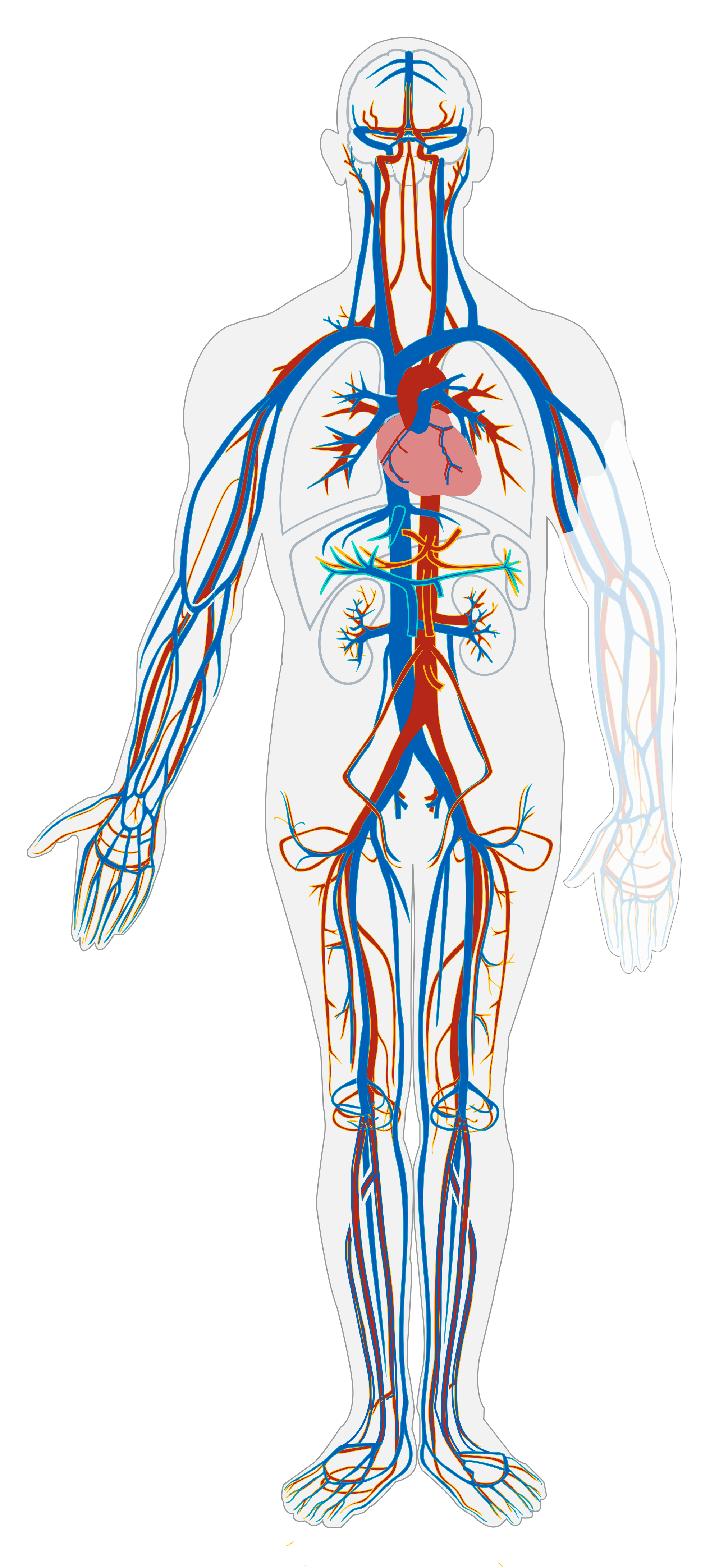

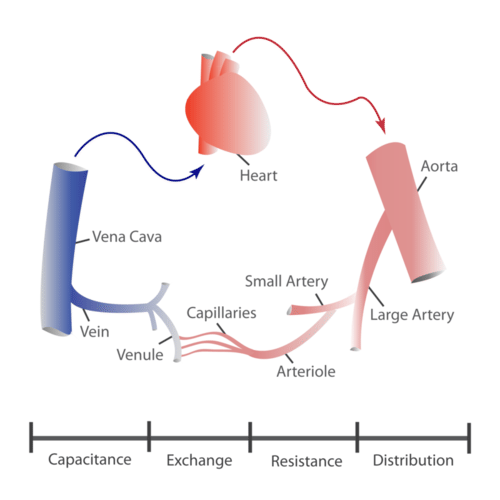

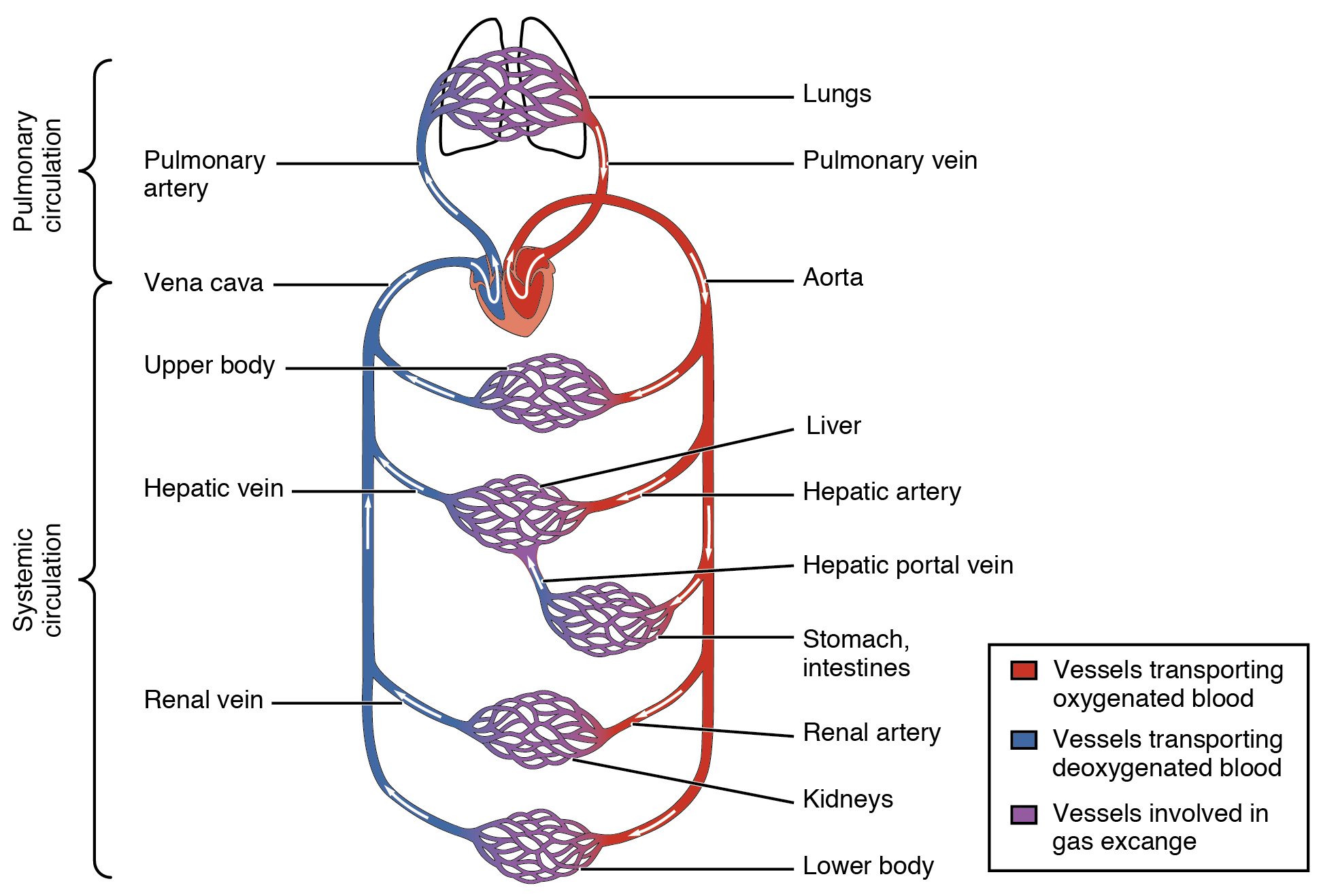

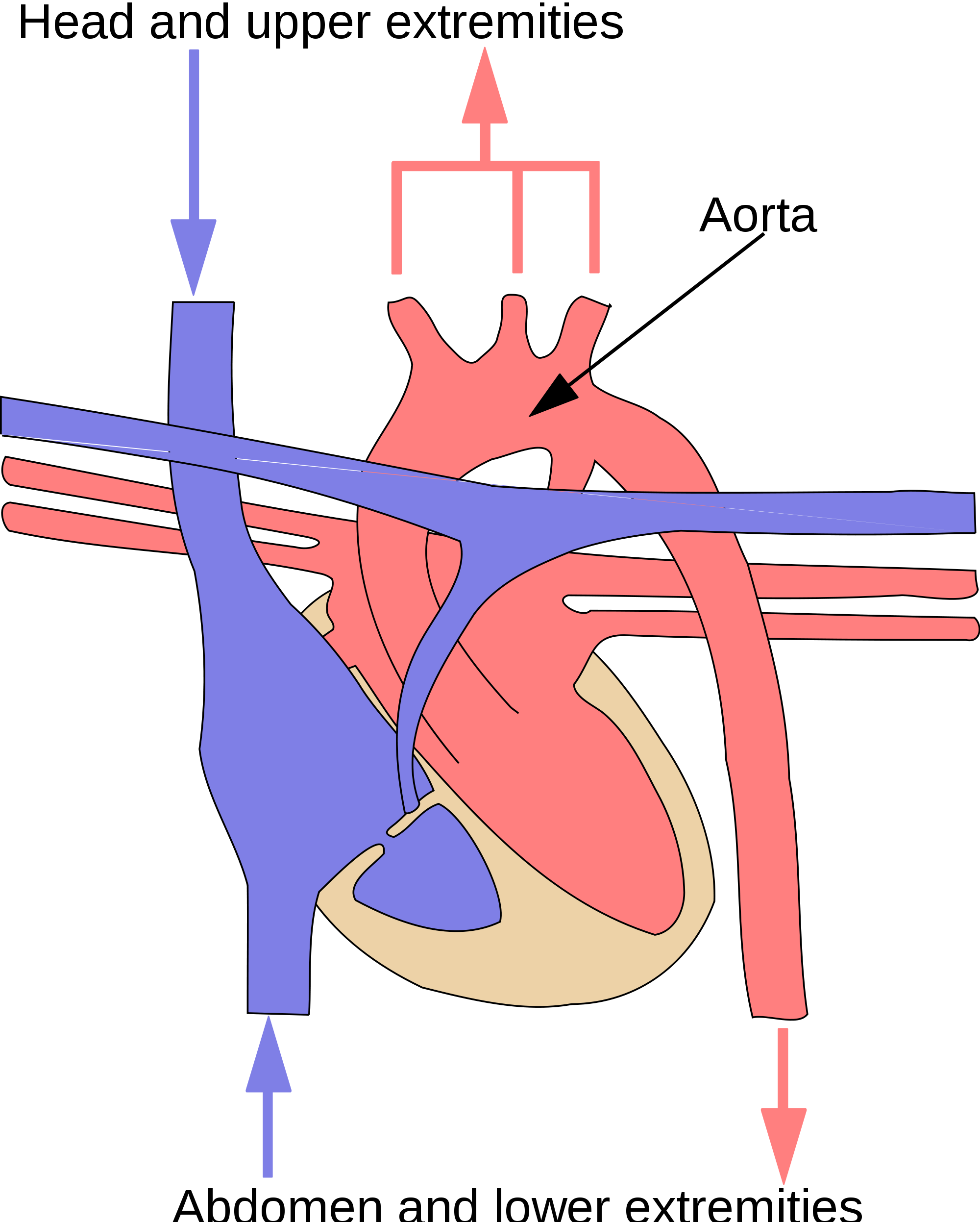

Introduction to the Heart

The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum (breastbone), slightly to the left of the center of the chest. A normal adult heart is about the size of a fist. The function of the heart is to pump blood through blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. The continuous flow of blood through the system is necessary to provide all the cells of the body with oxygen and nutrients, and to remove their metabolic wastes.

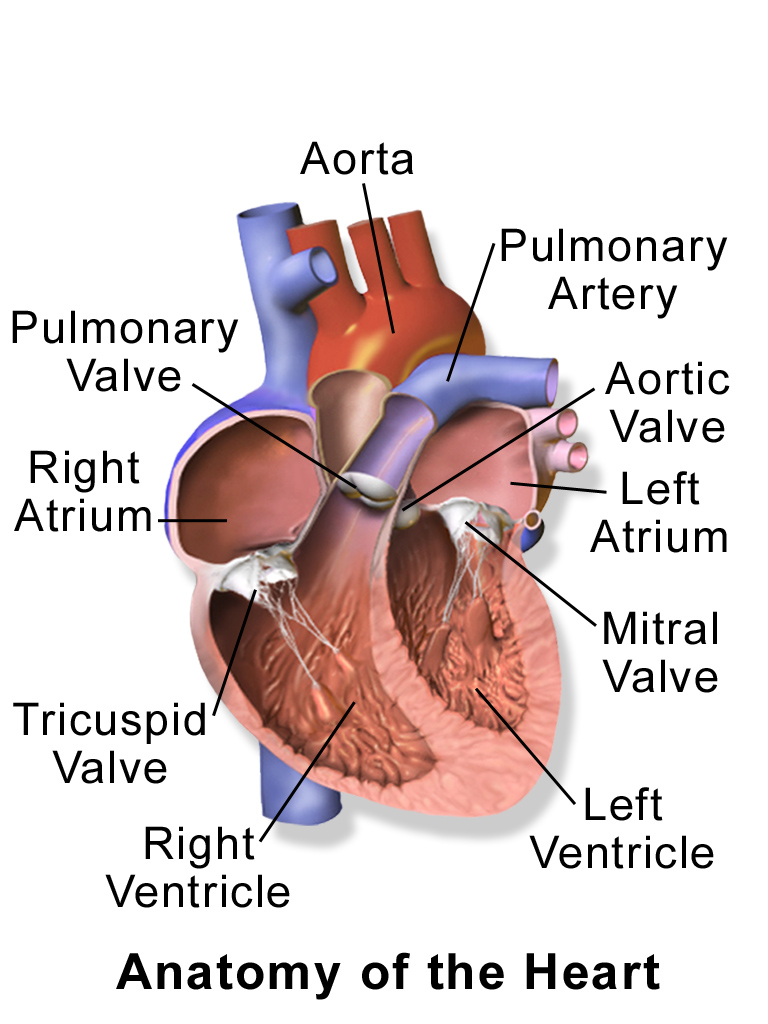

Structure of the Heart

The heart has a thick muscular wall that consists of several layers of tissue. Internally, the heart is divided into four chambers through which blood flows. Because of heart valves, blood flows in just one direction through the chambers.

Heart Wall

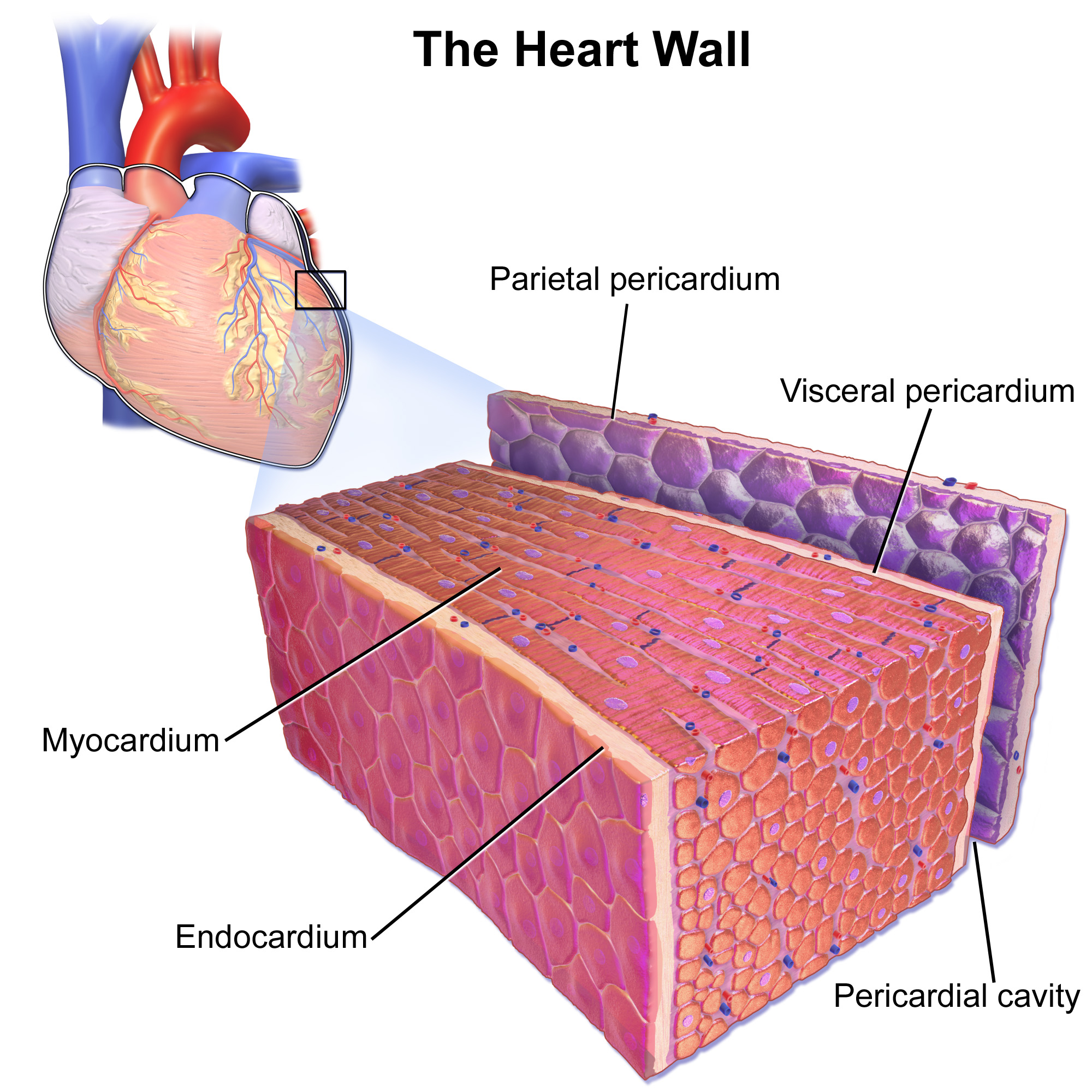

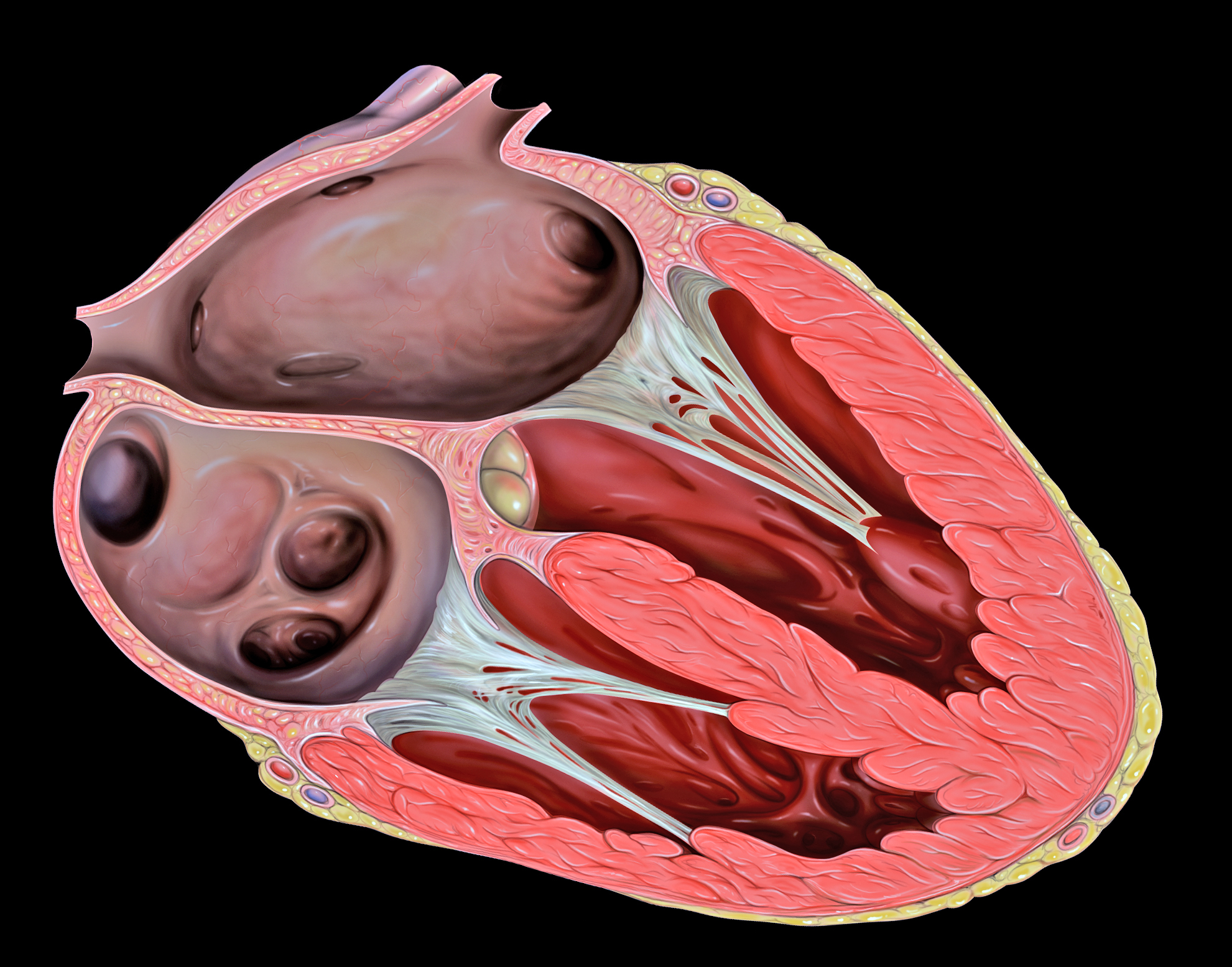

As shown in Figure 14.3.2, the wall of the heart is made up of three layers, called the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium.

- The endocardium is the innermost layer of the heart wall. It is made up primarily of simple epithelial cells. It covers the heart chambers and valves. A thin layer of connective tissue joins the endocardium to the myocardium.

- The myocardium is the middle and thickest layer of the heart wall. It consists of cardiac muscle surrounded by a framework of collagen. There are two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium: cardiomyocytes — which have the ability to contract easily — and pacemaker cells, which conduct electrical impulses that cause the cardiomyocytes to contract. About 99 per cent of cardiac muscle cells are cardiomyocytes, and the remaining one per cent is pacemaker cells. The myocardium is supplied with blood vessels and nerve fibres via the pericardium.

- The pericardium is a protective sac that encloses and protects the heart. The pericardium consists of two membranes (visceral pericardium and parietal pericardium), between which there is a fluid-filled cavity. The fluid helps to cushion the heart, and also lubricates its outer surface.

Heart Chambers

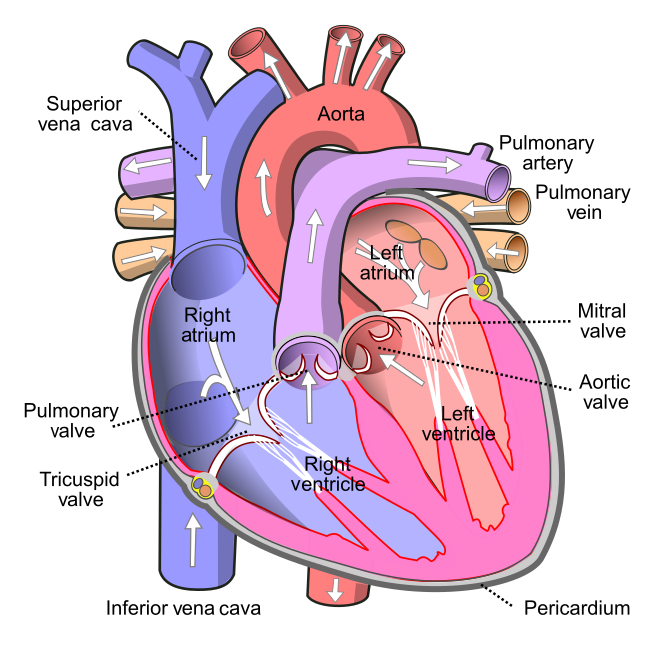

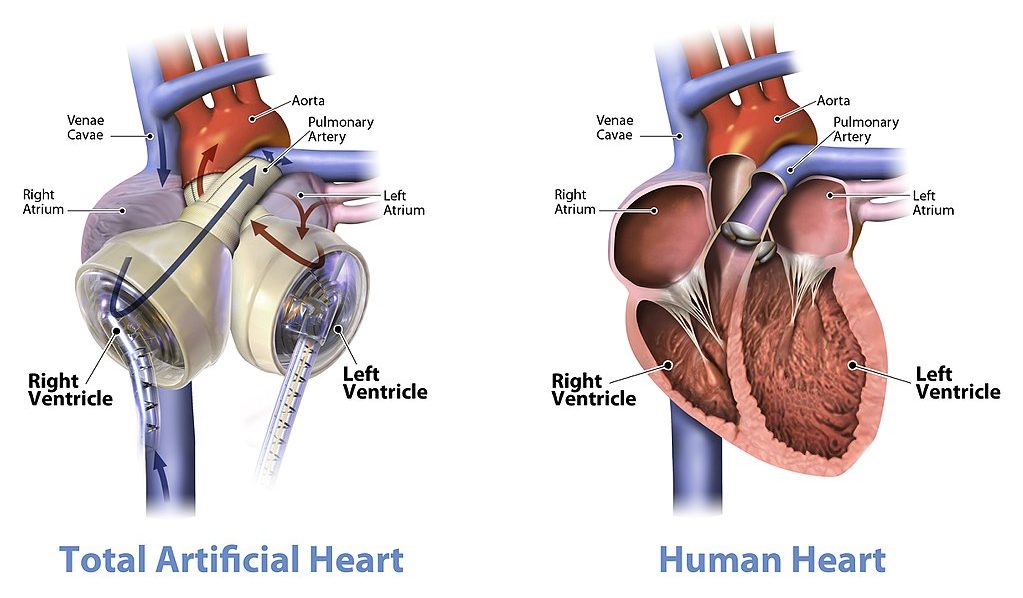

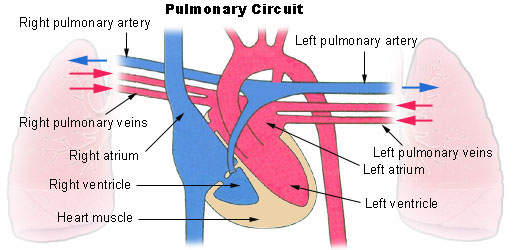

As shown in Figure 14.3.3 the four chambers of the heart include two upper chambers called atria (singular, atrium), and two lower chambers called ventricles. The atria are also referred to as receiving chambers, because blood coming into the heart first enters these two chambers. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the upper and lower body through the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, respectively. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs through the pulmonary veins. The ventricles are also referred to as discharging chambers, because blood leaving the heart passes out through these two chambers. The right ventricle discharges blood to the lungs through the pulmonary artery, and the left ventricle discharges blood to the rest of the body through the aorta. The four chambers are separated from each other by dense connective tissue consisting mainly of collagen.

Heart Valves

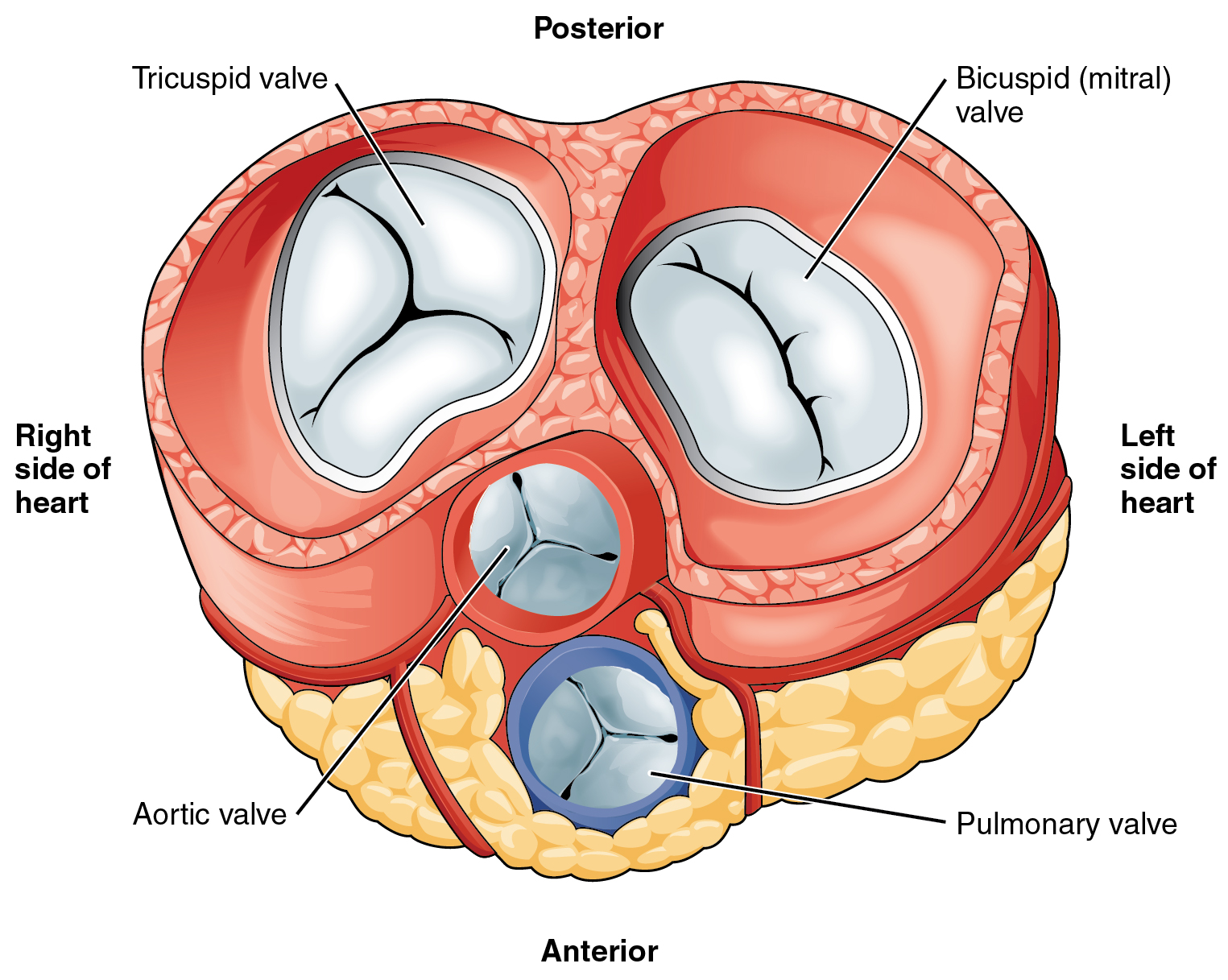

Figure 14.3.4 shows the location of the heart's four valves in a top-down view, looking down at the heart as if the arteries and veins feeding into and out of the heart were removed. The heart valves allow blood to flow from the atria to the ventricles, and from the ventricles to the pulmonary artery and aorta. The valves are constructed in such a way that blood can flow through them in only one direction, thus preventing the backflow of blood. Figure 14.3.5 shows how valves open to let blood into the appropriate chamber, and then close to prevent blood from moving in the wrong direction and the next chamber contracts. The four valves are the:

- Tricuspid atrioventricular valve, (can be shortened to tricuspid AV valve) which allows blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

- Bicuspid atrioventricular valve (also know as the mitral valve), which allows blood to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle.

- Pulmonary semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery.

- Aortic semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

The two atrioventricular (AV) valves prevent backflow when the ventricles are contracting, while the semilunar valves prevent backflow from vessels. This means that the AV valves must withstand much more pressure than do the semilunar valves. In order to withstand the force of the ventricles contracting (to prevent blood from backflowing into the atria), the AV valves are reinforced with structures called chordae tendineae — tendon-like cords of connective tissue which anchor the valve and prevent it from prolapse. Figure 14.3.6 shows the structure and location of the chordae tendoneae.

The chordae tendoneae are under such force that they need special attachments to the interior of the ventricles where they anchor. Papillary muscles are specialized muscles in the interior of the ventricle that provide a strong anchor point for the chordae tendineae.

Coronary Circulation

The cardiomyocytes of the muscular walls of the heart are very active cells, because they are responsible for the constant beating of the heart. These cells need a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients. The carbon dioxide and waste products they produce also must be continuously removed. The blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells make up the coronary circulation. Note that the blood vessels of the coronary circulation supply heart tissues with blood, and are different from the blood vessels that carry blood to and from the chambers of the heart as part of the general circulation. Coronary arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle cells. Coronary veins remove deoxygenated blood from the heart muscles cells.

- There are two coronary arteries — a right coronary artery that supplies the right side of the heart, and a left coronary artery that supplies the left side of the heart. These arteries branch repeatedly into smaller and smaller arteries and finally into capillaries, which exchange gases, nutrients, and waste products with cardiomyocytes.

- At the back of the heart, small cardiac veins drain into larger veins, and finally into the great cardiac vein, which empties into the right atrium. At the front of the heart, small cardiac veins drain directly into the right atrium.

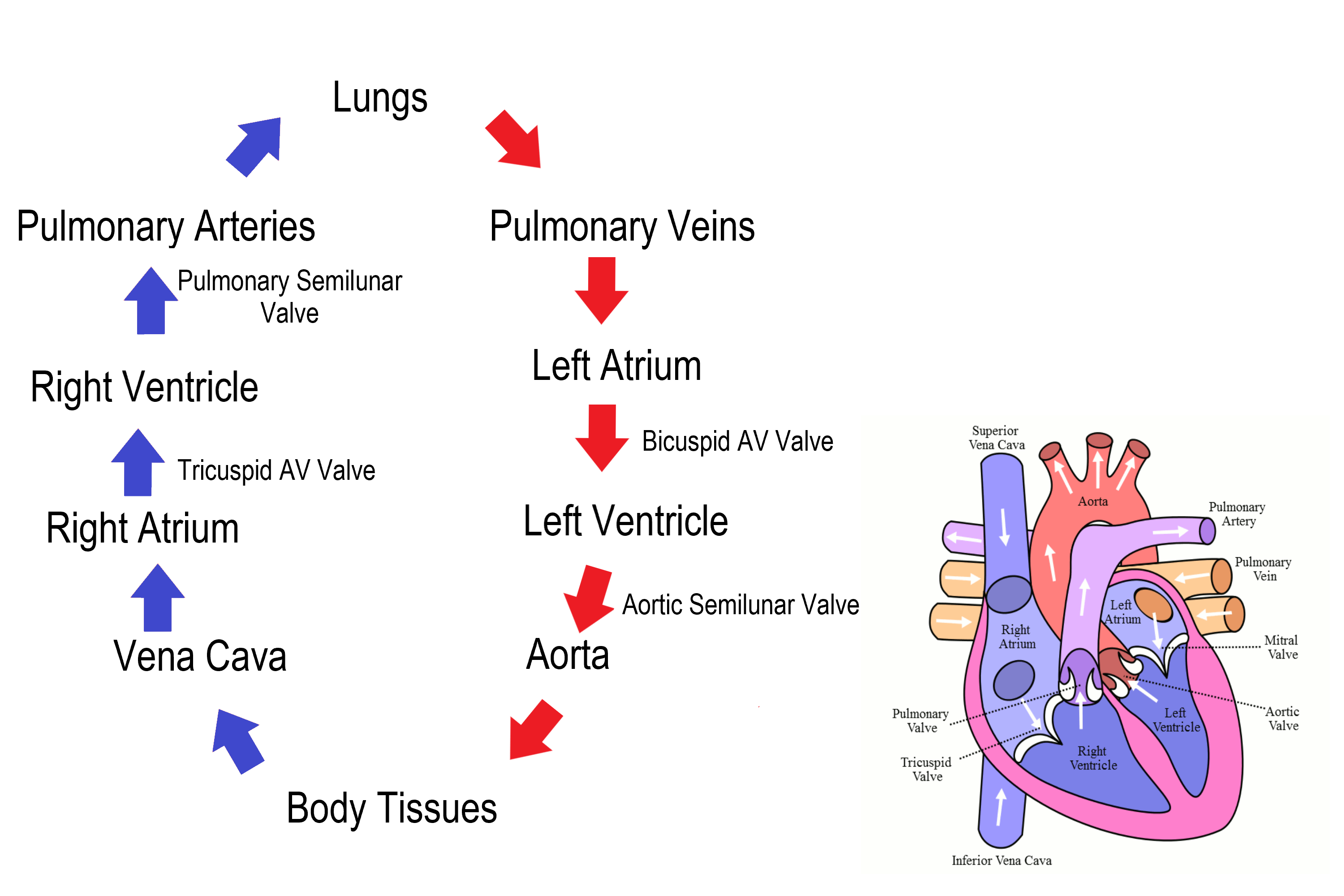

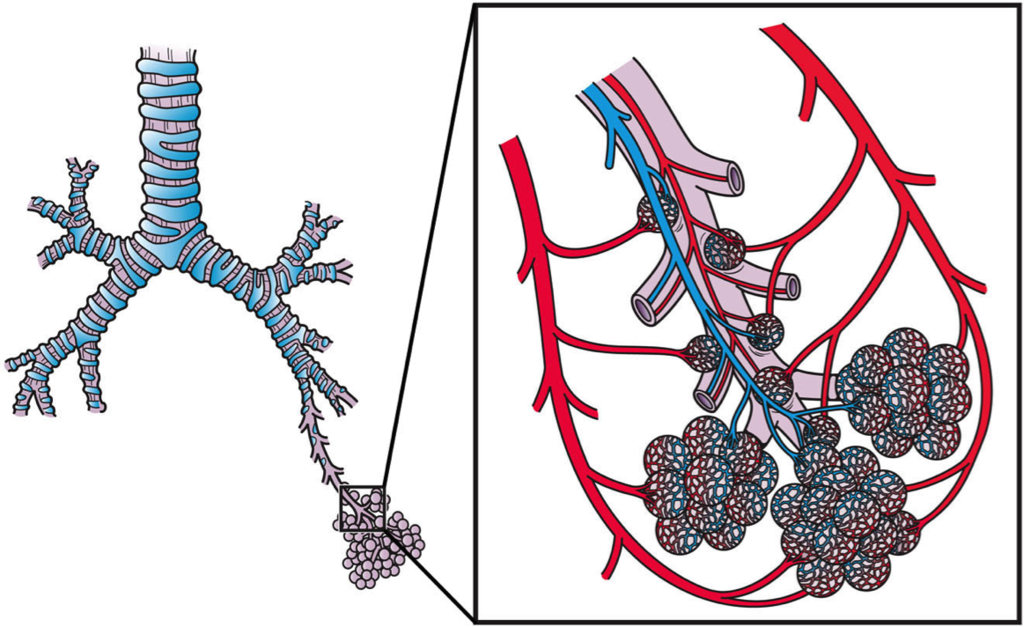

Blood Circulation Through the Heart

Figure 14.3.7 shows how blood circulates through the chambers of the heart. The right atrium collects blood from two large veins, the superior vena cava (from the upper body) and the inferior vena cava (from the lower body). The blood that collects in the right atrium is pumped through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. From the right ventricle, the blood is pumped through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery. The pulmonary artery carries the blood to the lungs, where it enters the pulmonary circulation, gives up carbon dioxide, and picks up oxygen. The oxygenated blood travels back from the lungs through the pulmonary veins (of which there are four), and enters the left atrium of the heart. From the left atrium, the blood is pumped through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From the left ventricle, the blood is pumped through the aortic valve into the aorta, which subsequently branches into smaller arteries that carry the blood throughout the rest of the body. After passing through capillaries and exchanging substances with cells, the blood returns to the right atrium via the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, and the process begins anew.

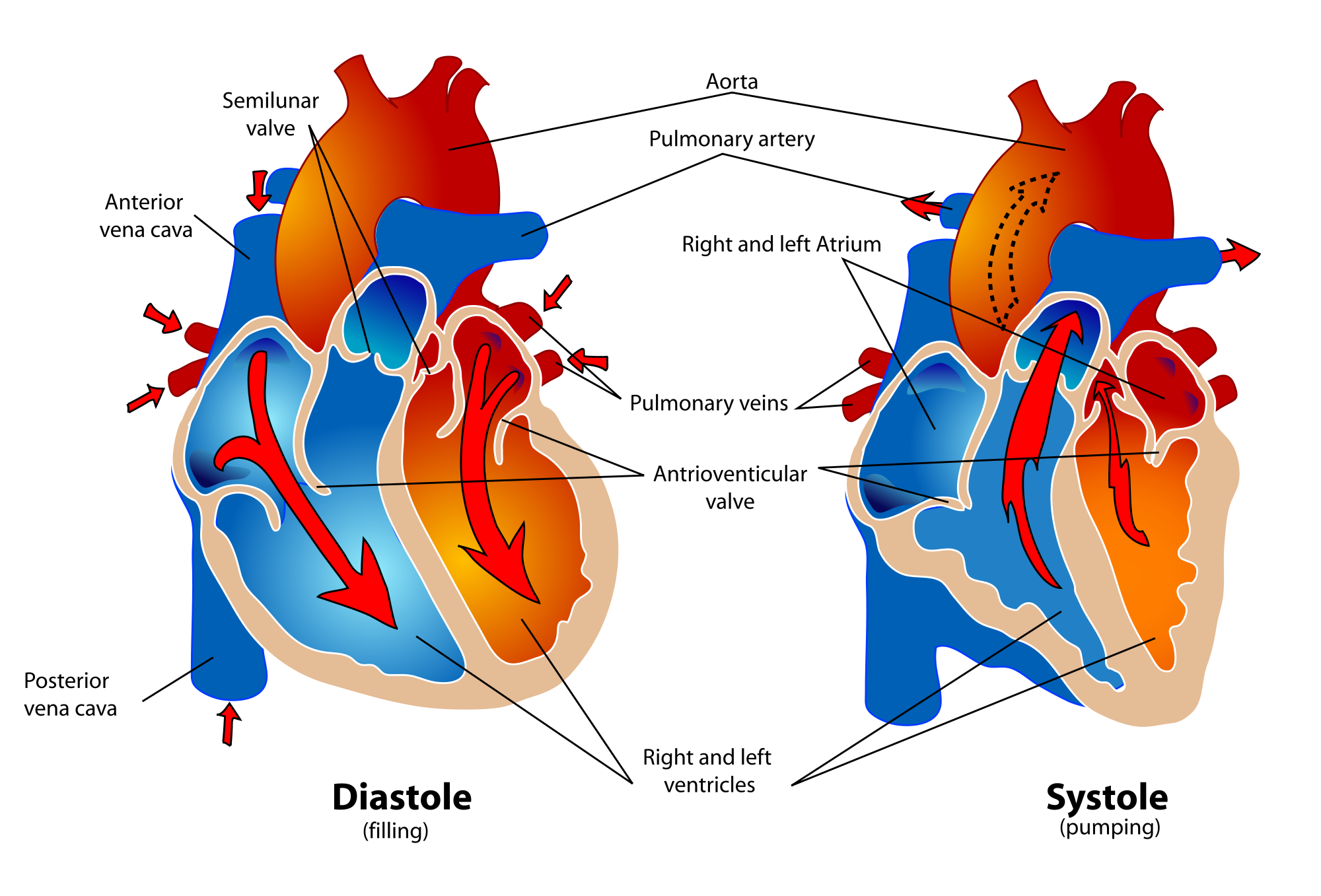

Cardiac Cycle

The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat, which includes one iteration of the lub and dub sounds heard through a stethoscope. During the cardiac cycle, the atria and ventricles work in a coordinated fashion so that blood is pumped efficiently through and out of the heart. The cardiac cycle includes two parts, called diastole and systole, which are illustrated in the diagrams in Figure 14.3.8.

- During diastole, the atria contract and pump blood into the ventricles, while the ventricles relax and fill with blood from the atria.

- During systole, the atria relax and collect blood from the lungs and body, while the ventricles contract and pump blood out of the heart.

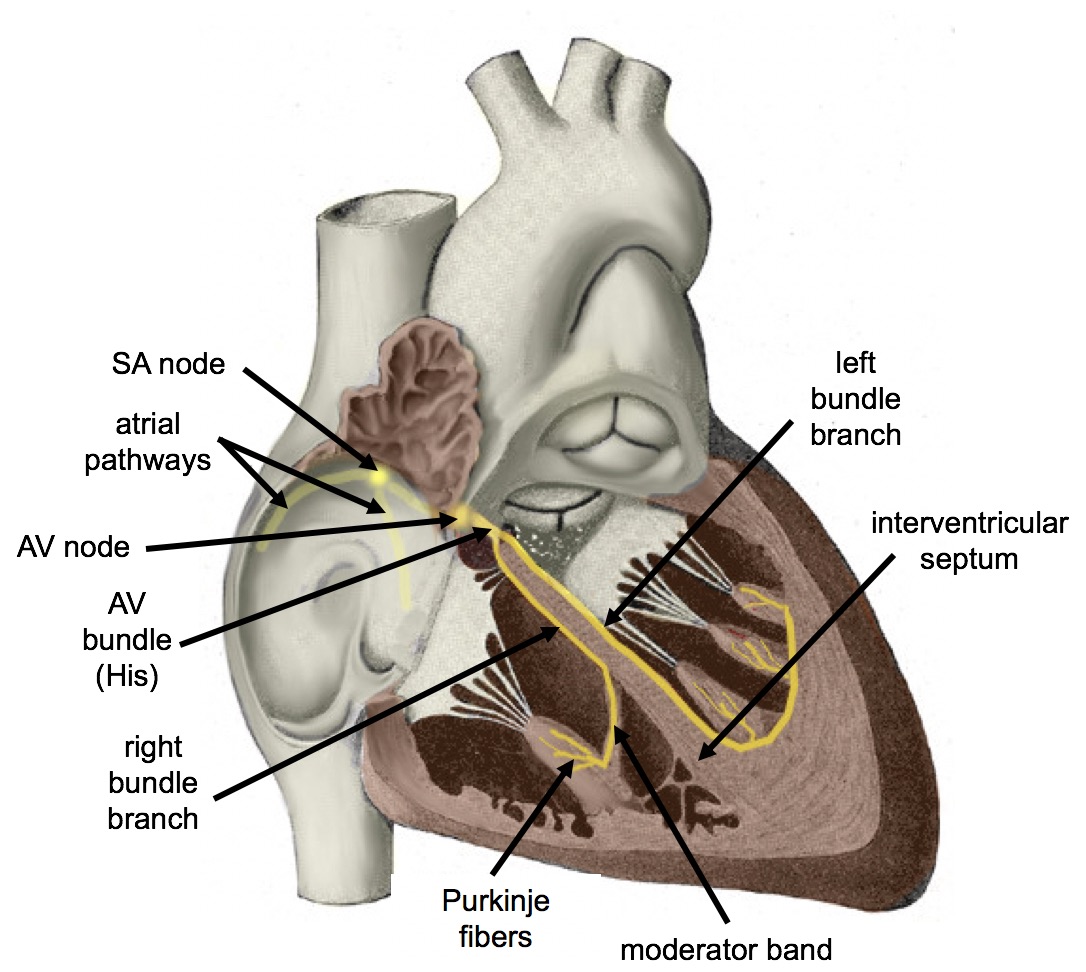

Electrical Stimulation of the Heart

The normal, rhythmical beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells, which are located in an area of the heart called the sinoatrial node (shown in Figure 14.3.9). The pacemaker cells create electrical signals with the movement of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and calcium ions) into and out of the cells. For each cardiac cycle, an electrical signal rapidly travels first from the sinoatrial node, to the right and left atria so they contract together. Then, the signal travels to another node, called the atrioventricular node (Figure 14.3.9), and from there to the right and left ventricles (which also contract together), just a split second after the atria contract.

The normal sinus rhythm of the heart is influenced by the autonomic nervous system through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. These nerves arise from two paired cardiovascular centers in the medulla of the brainstem. The parasympathetic nerves act to decrease the heart rate, and the sympathetic nerves act to increase the heart rate. Parasympathetic input normally predominates. Without it, the pacemaker cells of the heart would generate a resting heart rate of about 100 beats per minute, instead of a normal resting heart rate of about 72 beats per minute. The cardiovascular centers receive input from receptors throughout the body, and act through the sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, as needed. Increased physical activity, for example, is detected by receptors in muscles, joints, and tendons. These receptors send nerve impulses to the cardiovascular centers, causing sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, and allowing more blood to flow to the muscles.

Besides the autonomic nervous system, other factors can also affect the heart rate. For example, thyroid hormones and adrenal hormones (such as epinephrine) can stimulate the heart to beat faster. The heart rate also increases when blood pressure drops or the body is dehydrated or overheated. On the other hand, cooling of the body and relaxation — among other factors — can contribute to a decrease in the heart rate.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

When a patient’s heart is too diseased or damaged to sustain life, a heart transplant is likely to be the only long-term solution. The first successful heart transplant was undertaken in South Africa in 1967. There are over 2,200 Canadians walking around today because of life-saving heart transplant surgery. Approximately 180 heart transplant surgeries are performed each year, but there are still so many Canadians on the transplant list that some die while waiting for a heart. The problem is that far too few hearts are available for transplant — there is more demand (people waiting for a heart transplant) than supply (organ donors). Sometimes, recipient hopefuls will receive a device called a Total Artificial Heart (see Figure 14.3.10), which can buy them some time until a donor heart becomes available.

Watch the video below "Total artificial heart option..." from Stanford Health Care to see how it works:

https://youtu.be/1PtxaxcPnGc

Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage), Stanford Health Care, 2014.

14.3 Summary

- The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum and slightly to the left of the center of the chest. Its function is to pump blood through the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system.

- The wall of the heart consists of three layers. The middle layer, the myocardium, is the thickest layer and consists mainly of cardiac muscle. The interior of the heart consists of four chambers, with an upper atrium and lower ventricle on each side of the heart. Blood enters the heart through the atria, which pump it to the ventricles. Then the ventricles pump blood out of the heart. Four valves in the heart keep blood flowing in the correct direction and prevent backflow.

- The coronary circulation consists of blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells, and is different from the general circulation of blood through the heart chambers. There are two coronary arteries that supply the two sides of the heart with oxygenated blood. Cardiac veins drain deoxygenated blood back into the heart.

- Deoxygenated blood flows into the right atrium through veins from the upper and lower body (superior and inferior vena cava, respectively), and oxygenated blood flows into the left atrium through four pulmonary veins from the lungs. Each atrium pumps the blood to the ventricle below it. From the right ventricle, deoxygenated blood is pumped to the lungs through the two pulmonary arteries. From the left ventricle, oxygenated blood is pumped to the rest of the body through the aorta.

- The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat. It includes diastole — when the atria contract — and systole, when the ventricles contract.

- The normal, rhythmic beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node. Electrical signals from the pacemaker cells travel to the atria, and cause them to contract. Then, the signals travel to the atrioventricular node and from there to the ventricles, causing them to contract. Electrical stimulation from the autonomic nervous system and hormones from the endocrine system can also influence heartbeat.

14.3 Review Questions

- What is the heart, where is located, and what is its function?

-

- Describe the coronary circulation.

- Summarize how blood flows into, through, and out of the heart.

- Explain what controls the beating of the heart.

- What are the two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium? What are the differences between these two types of cells?

- Explain why the blood from the cardiac veins empties into the right atrium of the heart. Focus on function (rather than anatomy) in your answer.

14.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM

Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face, TED, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M

Watch a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI

A Change of Heart: My Transplant Experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse, TEDx Talks, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk

Heart Transplant Recipient Meets Donor Family For The First Time, WMC Health, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 14.3.1

- Female clinician dressed in scrubs using a stethoscope by Amanda Mills, USCDCP, on Pixnio is used under a CC0 public domain certification license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/publicdomain/).

- Human heart beating loud and strong (audio) by Daniel Simion on Soundbible.com is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.2

Blausen_0470_HeartWall by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.3

Diagram_of_the_human_heart_(cropped).svg by Wapcaplet on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 14.3.4

Heart_Valves by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.5

CG_Heart Valve Animation by DrJanaOfficial on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 14.3.6

Heart_tee_four_chamber_view by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator from Yale University School of Medicine, on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) license.

Figure 14.3.7

Circulation of blood through the heart by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license. [Original image in the bottom right is by Wapcaplet / CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Figure 14.3.8

Human_healthy_pumping_heart_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Common is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 14.3.9

Cardiac_Conduction_System by Cypressvine on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 19.12 Heart valves with the atria and major vessels removed [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 19.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/19-1-heart-anatomy#fig-ch20_01_04

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. (n.d.). https://www.heartandstroke.ca/

Sliwa, K., Zilla, P. (2017, December 7). 50th anniversary of the first human heart transplant—How is it seen today? European Heart Journal, 38(46):3402–3404. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx695

Stanford Health Care. (2014, December 3). Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PtxaxcPnGc&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2012, March 21). Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM&feature=youtu.be

TEDx Talks. (2018, April 18). A change of heart: My transplant experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI&feature=youtu.be

UMagazine. (2015, Fall). The cutting edge: Patient first to bridge from experimental total artificial heart to transplant. UCLA Health. https://www.uclahealth.org/u-magazine/patient-first-to-bridge-from-experimental-total-artificial-heart-to-transplant

UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids. (2018, February 7). Watch a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M&feature=youtu.be

WMC Health. (2018, September 13). Heart transplant recipient meets donor family for the first time. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a diagram of all the locations that chemical and mechanical digestion take place along the GI tract. In the mouth and pharynx, mechanical digestion includes chewing and swallowing and chemical digestion of carbohydrates and fats occurs. In the stomach, mechanical digestion includes peristaltic mixing and propulsion, and the chemical digestion of proteins and fats occurs. In the small intestine, mechanical digestion includes mixing and propulsion, and chemical digestion of carbohydrates, fats, polypeptides and nucleic acids takes place.

Case Study: Defending Your Defenses

Twenty-six-year-old Hakeem wasn’t feeling well. He was more tired than usual, dragging through his workdays despite going to bed earlier, and napping on the weekends. He didn’t have much of an appetite, and had started losing weight. When he pressed on the side of his neck, like the doctor is doing in Figure 17.1.1, he noticed an unusual lump.

Hakeem went to his doctor, who performed a physical exam and determined that the lump was a swollen lymph node. Lymph nodes are part of the immune system, and they will often become enlarged when the body is fighting off an infection. Dr. Hayes thinks that the swollen lymph node and fatigue could be signs of a viral or bacterial infection, although he is concerned about Hakeem’s lack of appetite and weight loss. All of those symptoms combined can indicate a type of cancer called lymphoma. An infection, however, is a more likely cause, particularly in a young person like Hakeem. Dr. Hayes prescribes an antibiotic in case Hakeem has a bacterial infection, and advises him to return in a few weeks if his lymph node does not shrink, or if he is not feeling better.

Hakeem returns a few weeks later. He is not feeling better and his lymph node is still enlarged. Dr. Hayes is concerned, and orders a biopsy of the enlarged lymph node. A lymph node biopsy for suspected lymphoma often involves the surgical removal of all or part of a lymph node. This helps to determine whether the tissue contains cancerous cells.

The initial results of the biopsy indicate that Hakeem does have lymphoma. Although lymphoma is more common in older people, young adults and even children can get this disease. There are many types of lymphoma, with the two main types being Hodgkin's lymphoma and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), in turn, has many subtypes. The subtype depends on several factors, including which cell types are affected. Some subtypes of NHL, for example, affect immune system cells called B cells, while others affect different immune system cells called T cells.

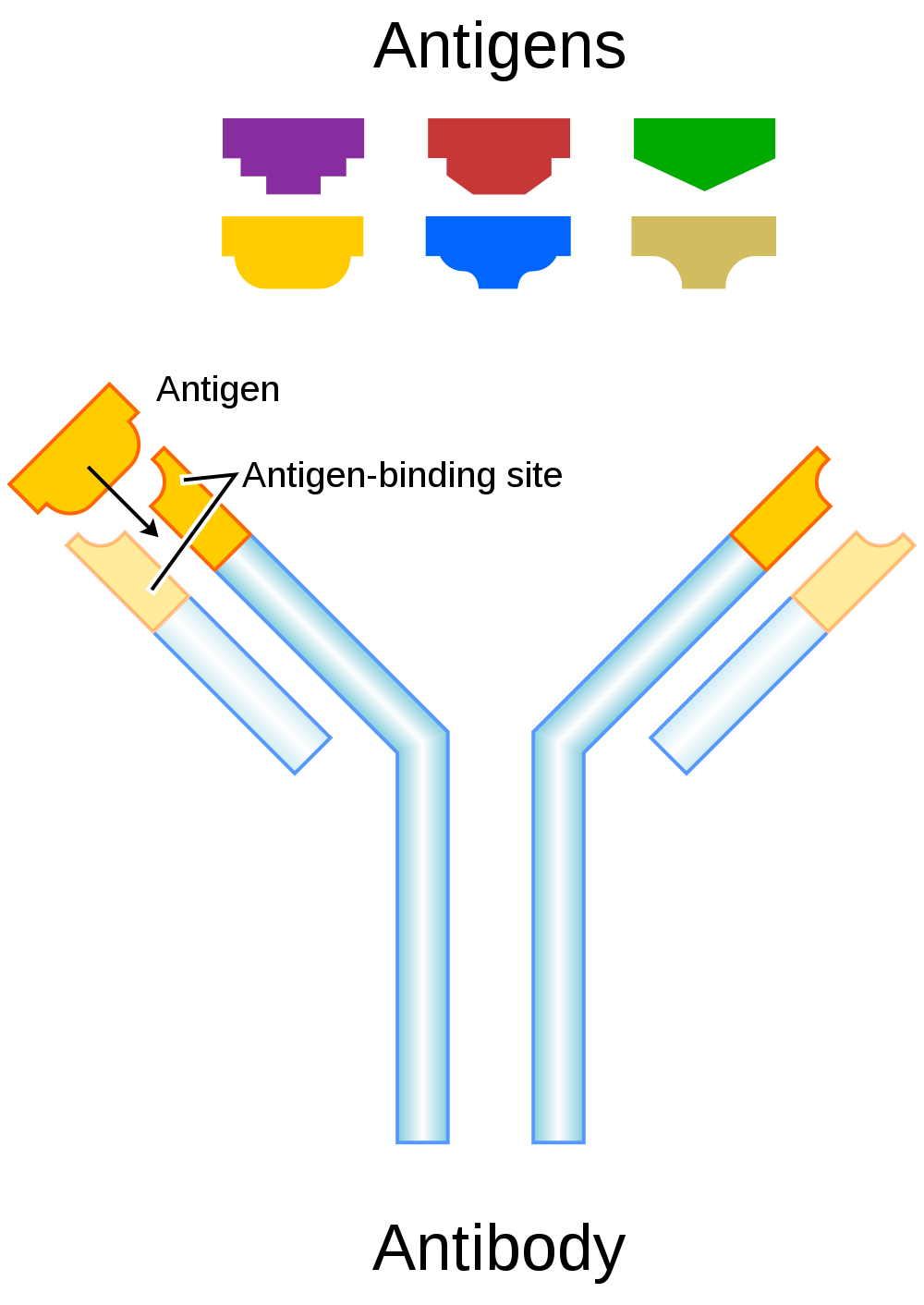

Dr. Hayes explains to Hakeem that it is important to determine which type of lymphoma he has, in order to choose the best course of treatment. Hakeem’s biopsied tissue will be further examined and tested to see which cell types are affected, as well as which specific cell-surface proteins — called antigens — are present. This should help identify his specific type of lymphoma.

As you read this chapter, you will learn about the functions of the immune system, and the specific roles that its cells and organs — such as B and T cells and lymph nodes — play in defending the body. At the end of this chapter, you will learn what type of lymphoma Hakeem has and what some of his treatment options are, including treatments that make use of the biochemistry of the immune system to fight cancer with the immune system itself.

Chapter Overview: Immune System

In this chapter, you will learn about the immune system — the system that defends the body against infections and other causes of disease, such as cancerous cells. Specifically, you will learn about:

- How the immune system identifies normal cells of the body as “self” and pathogens and damaged cells as “non-self.”

- The two major subsystems of the general immune system: the innate immune system — which provides a quick, but non-specific response — and the adaptive immune system, which is slower, but provides a specific response that often results in long-lasting immunity.

- The specialized immune system that protects the brain and spinal cord, called the neuroimmune system.

- The organs, cells, and responses of the innate immune system, which includes physical barriers (such as skin and mucus), chemical and biological barriers, inflammation, activation of the complement system of molecules, and non-specific cellular responses (such as phagocytosis).

- The lymphatic system — which includes white blood cells called lymphocytes, lymphatic vessels (which transport a fluid called lymph), and organs (such as the spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes) — and its important role in the adaptive immune system.

- Specific cells of the immune system and their functions, including B cells, T cells, plasma cells, and natural killer cells.

- How the adaptive immune system can generate specific and often long-lasting immunity against pathogens through the production of antibodies.

- How vaccines work to generate immunity.

- How cells in the immune system detect and kill cancerous cells.

- Some strategies that pathogens employ to evade the immune system.

- Disorders of the immune system, including allergies, autoimmune diseases (such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis), and immunodeficiency resulting from conditions such as HIV infection.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- What are the functions of lymph nodes?

- What are B and T cells? How do they relate to lymph nodes?

- What are cell-surface antigens? How do they relate to the immune system and to cancer?

Attributions

Figure 17.1.1

Lymph nodes/Is it a Cold or the Flu by Lee Health on Vimeo is used under Vimeo's Terms of Service (https://vimeo.com/terms#licenses).

Figure 17.1.2

mitchell-luo-ymo_yC_N_2o-unsplash [photo] by Mitchell Luo on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 17.1.3

Lymph node biopsy by US Army Africa on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

References

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Hodgkin's lymphoma [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hodgkins-lymphoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20352646

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/non-hodgkins-lymphoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20375680

The main mineralocorticoid hormone which is responsible for sodium conservation in the kidney, salivary glands, sweat glands and colon.

Image shows a man at an oxygen bar. There are several erlenmeyer flasks of differently scented oxygen with tubes coming out of the top of each. The man is wearing a nasal cannula (tube that blows air into your nostrils).

Image shows a labelled diagram of a lymph node. It is roughly kidney shaped, and there are multiple incoming and outgoing lymphatic vessels. It is surrounded by a capsule, lined with a cortex, and contains a sinus on the inside.

An evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms.

A type of immune cell that has granules (small particles) with enzymes that are released during allergic reactions and asthma. A basophil is a type of white blood cell and a type of granulocyte.

Image shows a diagram of the body and the locations where main lymph nodes are found. There are several regions along the midline of the body, a concentration in the neck, armpits, and groin.

A genetically-based trait that has evolved because it helps living things survive and reproduce in a given environment.

Image shows a photo of a young man.

Image shows a diagram comparing a healthy nephron and its blood supply and one with diabetic nephropathy. The diseased one has blood vessels that look deformed and fragile.

Image shows a photograph of a finger with a paper cut.

Image shows a photograph of several wine bottles on a shelf. The image has been deliberately blurred to simulate the effects of drunkeness.

Image shows a diagram labeling the major arteries of the body. Some of these include the carotid artery which provides blood to the neck and head, the brachiocephalic artery which supplies blood to the arms and head, the renal artery supplying blood to the kidneys, the mesenteric arteries supplying blood to the intestines, the femoral arteries supplying blood to the legs.

Image shows a diagram of the process of hemodialysis. Blood is removed from the patient from a location on the arm. Blood enters the hemodialysis apparatus and is run through dialyser to clean wastes from the blood. There are mechanisms to maintain blood tonicity and pressure, to prevent clotting, and ensure no air enters the bloodstream. The cleaned blood is returned to the patient in their arm, proximal to the place where the blood was first removed.

Image shows a side view diagram of the male and female pelvis. The male urethra is much longer because it extends through the penis, and in women it exits through the pelvic floor.

Case Study: Please Don’t Pass the Bread

Angela and Saloni are college students who met in physics class. They decide to study together for their upcoming midterm, but first, they want to grab some lunch. Angela says there is a particular restaurant she would like to go to, because they are able to accommodate her dietary restrictions. Saloni agrees and they head to the restaurant.

At lunch, Saloni asks Angela what is special about her diet. Angela tells her that she can’t eat gluten. Saloni says, “My cousin did that for a while because she heard that gluten is bad for you. But it was too hard for her to not eat bread and pasta, so she gave it up.” Angela tells Saloni that avoiding gluten isn’t optional for her — she has celiac disease. Eating even very small amounts of gluten could damage her digestive system. It can be difficult for people living with celiac disease to find foods when eating out.

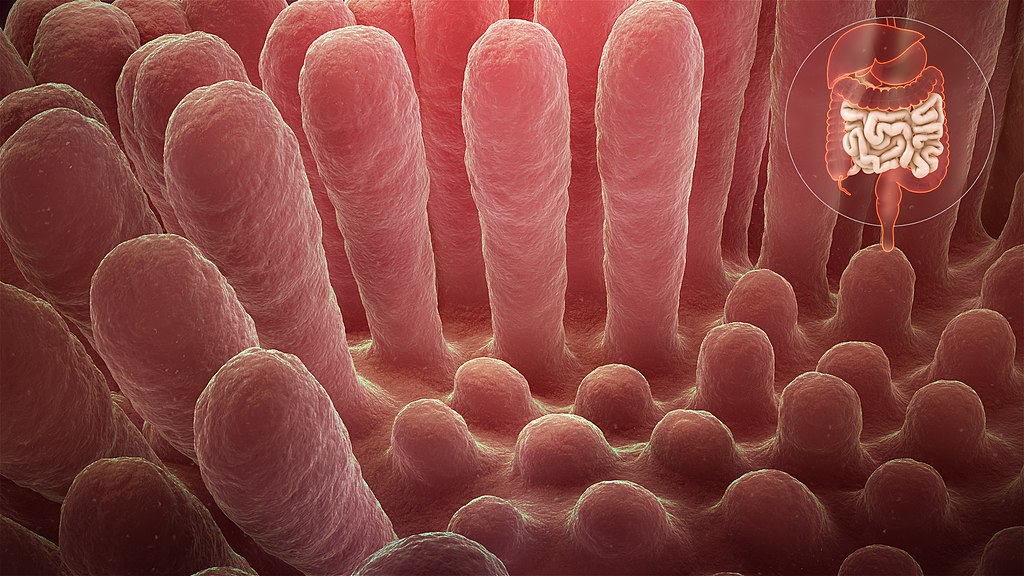

You have probably heard of gluten, but what is it, and why is it harmful to people with celiac disease? Gluten is a protein present in wheat and some other grains (such as barley, rye, and oats), so it is commonly found in foods like bread, pasta, baked goods, and many packaged foods, like the ones pictured in Figure 15.1.2.

Figure 15.1.2 Gluten is a protein present in foods like bread, pasta, and baked goods.

For people with celiac disease, eating gluten causes an autoimmune reaction that results in damage to the small, finger-like villi lining the small intestine, causing them to become inflamed and flattened (see Figure 15.1.3). This damage interferes with the digestive process, which can result in a wide variety of symptoms including diarrhea, anemia, skin rash, bone pain, depression, and anxiety, among others. The degree of damage to the villi can vary from mild to severe, with more severe damage generally resulting in more significant symptoms and complications. Celiac disease can have serious long-term consequences, such as osteoporosis, problems in the nervous and reproductive systems, and the development of certain types of cancers.

Why does celiac disease cause so many different types of symptoms and have such significant negative health consequences? As you read this chapter and learn about how the digestive system works, you will see just how important the villi of the small intestine are to the body as a whole. At the end of the chapter, you will learn more about celiac disease, why it can be so serious, and whether it is worth avoiding gluten for people who do not have a diagnosed medical issue with it.

Chapter Overview: Digestive System

In this chapter, you will learn about the digestive system, which processes food so that our bodies can obtain nutrients. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The structures and organs of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through which food directly passes. This includes the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.

- The functions of the GI tract, including mechanical and chemical digestion, absorption of nutrients, and the elimination of solid waste.

- The accessory organs of digestion — the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas — which secrete substances needed for digestion into the GI tract, in addition to performing other important functions.

- Specializations of the tissues of the digestive system that allow it to carry out its functions.

- How different types of nutrients (such as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) are digested and absorbed by the body.

- Beneficial bacteria that live in the GI tract and help us digest food, produce vitamins, and protect us from harmful pathogens and toxic substances.

- Disorders of the digestive system, including inflammatory bowel diseases, ulcers, diverticulitis, and gastroenteritis (commonly known as “stomach flu”).

As you read this chapter, think about the following questions related to celiac disease:

- What are the general functions of the small intestine? What do the villi in the small intestine do?

- Why do you think celiac disease causes so many different types of symptoms and potentially serious complications?

- What are some other autoimmune diseases that involve the body attacking its own digestive system?

Attributions

Figure 15.1.1

Bread [photo] by Sergio Arze on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 15.1.2

- Paste cu sos de roșii by Sestrjevitovschii Ina on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Cookies and More by Sarah Shaffer on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Raspberry waffles by Izabelle Acheson on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Homemade croissant & pain au chocolat by Cristiano Pinto on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 15.1.3

Inflammed_mucous_layer_of_the_intestinal_villi_depicting_Celiac_disease by www.scientificanimations.com (image 140/191) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Image shows to small children in a backyard wading pool. One adult is standing by the pool resting their foot on the edge and another adult is sitting nearby in a lawn chair.

Image shows a man sneezing against a black background. You can see all the the saliva and snot he has expelled in a cloud coming out of his mouth and nose. It is super gross.

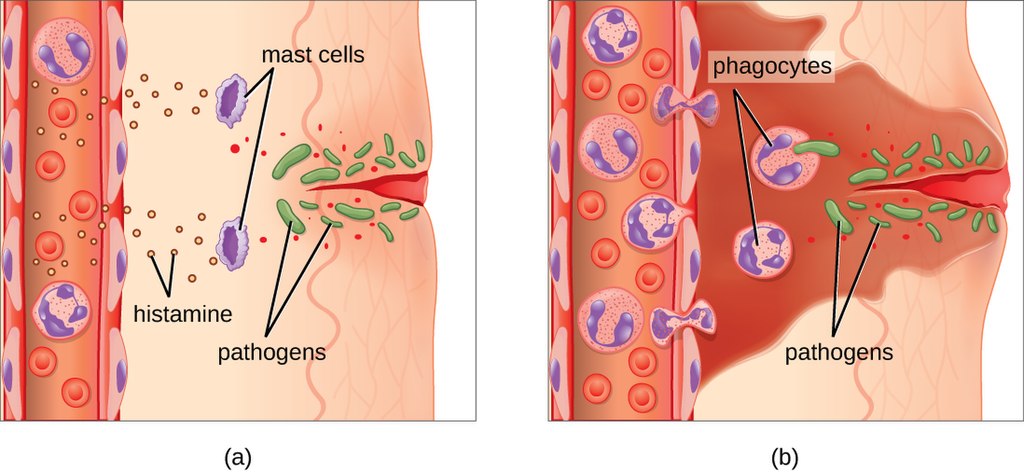

Image shows a two part diagram of inflammatory response. The first pane shows an initial injury to the skin and introduction of pathogens to deeper tissues. Mast cells release clouds of histamines into the tissue.

In the second pane, the capillaries have become more porous, due to the histamines. Leukocytes are squeezing out of the capillary into the injured tissue, where they will phagocytize any pathogens they come across.

Image shows 8 leukocytes involved in innate immunity. They are: Mast cells, , monoctyes, natural killer cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, basophils and eosinophyls. Monocytes are round with a large round central nucleus. Natural killer cells are

almost round, with a "U" shaped nucleus. Macrophages have an irregular shape and are quite large. Dendritic cells are star-shaped. Neutrophils and basophils are round with a "U"shaped nucleus that is quite large. The ends of the "U" are a bit bulbous.

Image shows a diagram of the four steps of a white blood cell phagocytizing a bacterium. In the first stage, the white blood cell extends its plasma membrane to surround the bacteria and trap it inside a vesicle, very similar to endocytosis. In the next stage, a lysosome merges with the vesicle containing the bacterium; the digestive enzymes break down the bacterium, and the white blood cell absorbs the resulting nutrients.

Paper Cut

It’s just a paper cut, but the break in your skin could provide an easy way for pathogens to enter your body. If bacteria were to enter through the cut and infect the wound, your innate immune system would quickly respond with a dizzying array of general defenses.

What Is the Innate Immune System?

The innate immune system is a subset of the human immune system that produces rapid, but non-specific responses to pathogens. Innate responses are generic, rather than tailored to a particular pathogen. The innate system responds in the same general way to every pathogen it encounters. Although the innate immune system provides immediate and rapid defenses against pathogens, it does not confer long-lasting immunity to them. In most organisms, the innate immune system is the dominant system of host defense. Other than most vertebrates (including humans), the innate immune system is the only system of host defense.

In humans, the innate immune system includes surface barriers, inflammation, the complement system, and a variety of cellular responses. Surface barriers of various types generally keep most pathogens out of the body. If these barriers fail, then other innate defenses are triggered. The triggering event is usually the identification of pathogens by pattern-recognition receptors on cells of the innate immune system. These receptors recognize molecules that are broadly shared by pathogens, but distinguishable from host molecules. Alternatively, the other innate defenses may be triggered when damaged, injured, or stressed cells send out alarm signals, many of which are recognized by the same receptors as those that recognize pathogens.

Barriers to Pathogens

The body’s first line of defense consists of three different types of barriers that keep most pathogens out of body tissues. The types of barriers are mechanical, chemical, and biological barriers.

Mechanical Barriers

Mechanical barriers are the first line of defense against pathogens, and they physically block pathogens from entering the body. The skin is the most important mechanical barrier. In fact, it is the single most important defense the body has. The outer layer of skin — the epidermis — is tough, and very difficult for pathogens to penetrate. It consists of dead cells that are constantly shed from the body surface, a process that helps remove bacteria and other infectious agents that have adhered to the skin. The epidermis also lacks blood vessels and is usually lacking moisture, so it does not provide a suitable environment for most pathogens. Hair — which is an accessory organ of the skin — also helps keep out pathogens. Hairs inside the nose may trap larger pathogens and other particles in the air before they can enter the airways of the respiratory system (see Figure 17.4.2).

Mucous membranes provide a mechanical barrier to pathogens and other particles at body openings. These membranes also line the respiratory, gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive tracts. Mucous membranes secrete mucus, which is a slimy and somewhat sticky substance that traps pathogens. Many mucous membranes also have hair-like cilia that sweep mucus and trapped pathogens toward body openings, where they can be removed from the body. When you sneeze or cough, mucus and pathogens are mechanically ejected from the nose and throat, as you can see in Figure 17.4.3. A sneeze can travel as fast as 160 Km/hr (about 99 mi/hour) and expel as many as 100,000 droplets into the air around you (a good reason to cover your sneezes!). Other mechanical defenses include tears, which wash pathogens from the eyes, and urine, which flushes pathogens out of the urinary tract.

Chemical Barriers

Chemical barriers also protect against infection by pathogens. They destroy pathogens on the outer body surface, at body openings, and on inner body linings. Sweat, mucus, tears, saliva, and breastmilk all contain antimicrobial substances (such as the enzyme lysozyme) that kill pathogens, especially bacteria. Sebaceous glands in the dermis of the skin secrete acids that form a very fine, slightly acidic film on the surface of the skin. This film acts as a barrier to bacteria, viruses, and other potential contaminants that might penetrate the skin. Urine and vaginal secretions are also too acidic for many pathogens to endure. Semen contains zinc — which most pathogens cannot tolerate — as well as defensins, which are antimicrobial proteins that act mainly by disrupting bacterial cell membranes. In the stomach, stomach acid and digestive enzymes called proteases (which break down proteins) kill most of the pathogens that enter the gastrointestinal tract in food or water.

Biological Barriers

Biological barriers are living organisms that help protect the body from pathogens. Trillions of harmless bacteria normally live on the human skin and in the urinary, reproductive, and gastrointestinal tracts. These bacteria use up food and surface space that help prevent pathogenic bacteria from colonizing the body. Some of these harmless bacteria also secrete substances that change the conditions of their environment, making it less hospitable to potentially harmful bacteria. They may release toxins or change the pH, for example. All of these effects of harmless bacteria reduce the chances that pathogenic microorganisms will be able to reach sufficient numbers and cause illness.

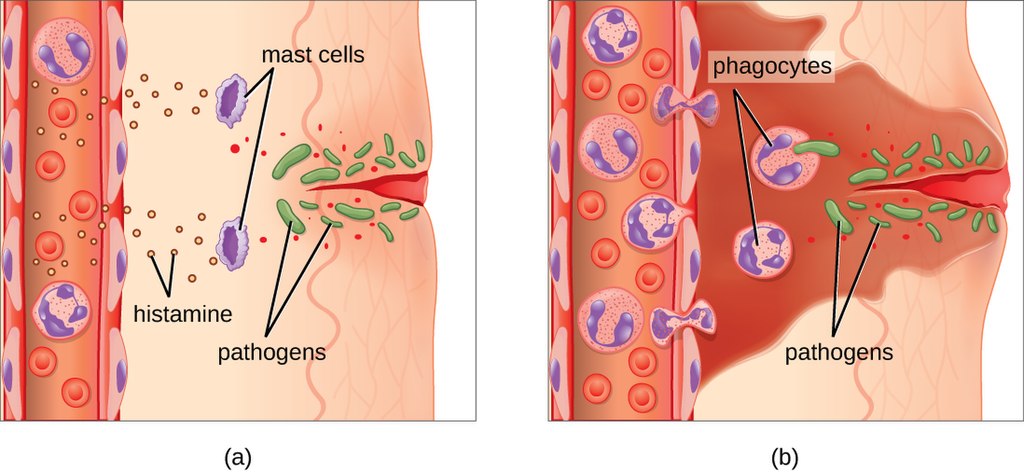

Inflammation

If pathogens manage to breach the barriers protecting the body, one of the first active responses of the innate immune system kicks in. This response is inflammation. The main function of inflammation is to establish a physical barrier against the spread of infection. It also eliminates the initial cause of cell injury, clears out dead cells and tissues damaged from the original insult and the inflammatory process, and initiates tissue repair. Inflammation is often a response to infection by pathogens, but there are other possible causes, including burns, frostbite, and exposure to toxins.

The signs and symptoms of inflammation include redness, swelling, warmth, pain, and frequently some loss of function. These symptoms are caused by increased blood flow into infected tissue, and a number of other processes, illustrated in Figure 17.4.4.

Inflammation is triggered by chemicals such as cytokines and histamines,which are released by injured or infected cells, or by immune system cells such as macrophages (described below) that are already present in tissues. These chemicals cause capillaries to dilate and become leaky, increasing blood flow to the infected area and allowing blood to enter the tissues. Pathogen-destroying leukocytes and tissue-repairing proteins migrate into tissue spaces from the bloodstream to attack pathogens and repair their damage. Cytokines also promote chemotaxis, which is migration to the site of infection by pathogen-destroying leukocytes. Some cytokines have anti-viral effects. They may shut down protein synthesis in host cells, which viruses need in order to survive and replicate.

See the video "The inflammatory response" by Neural Academy to learn about inflammatory response in more detail:

https://youtu.be/Fbzb75HA9M8

The inflammatory response, Neural Academy, 2019.

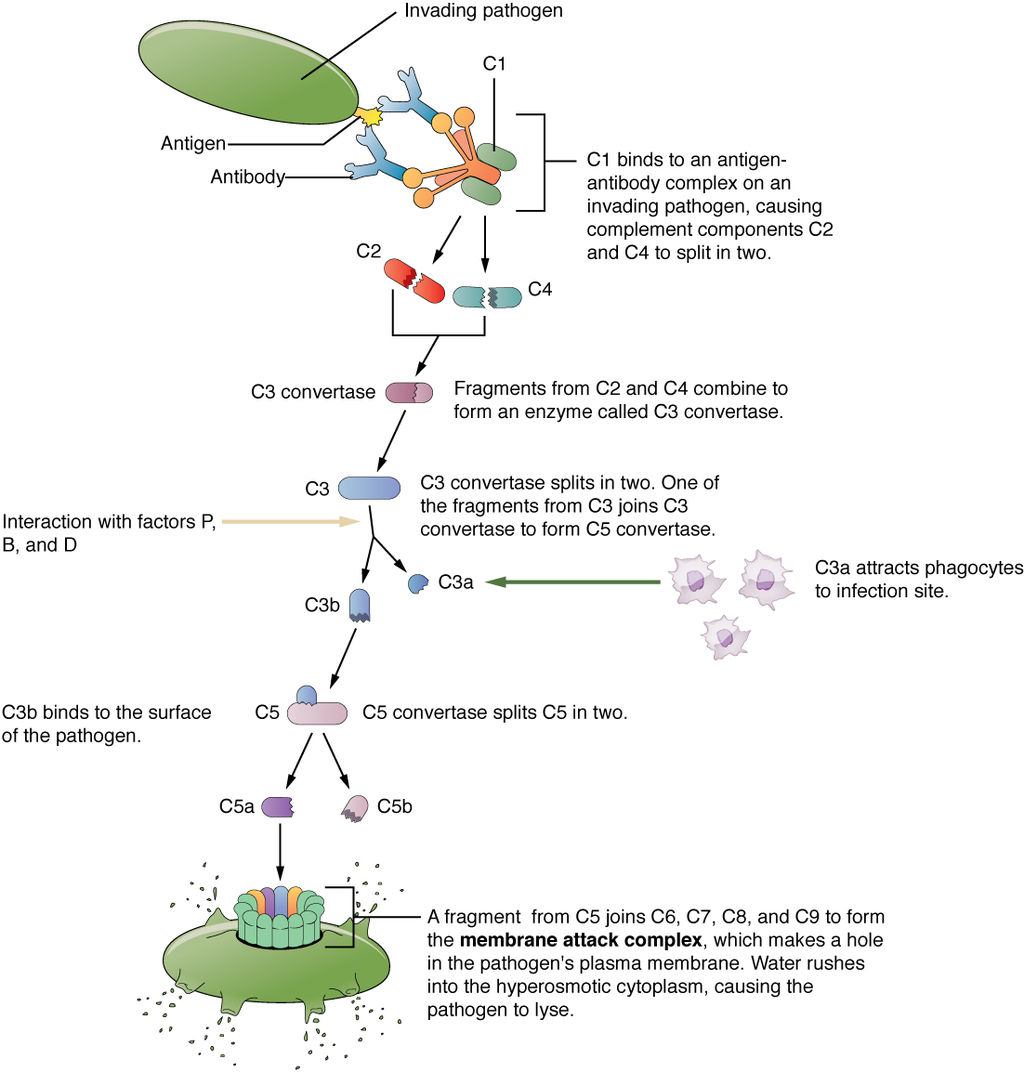

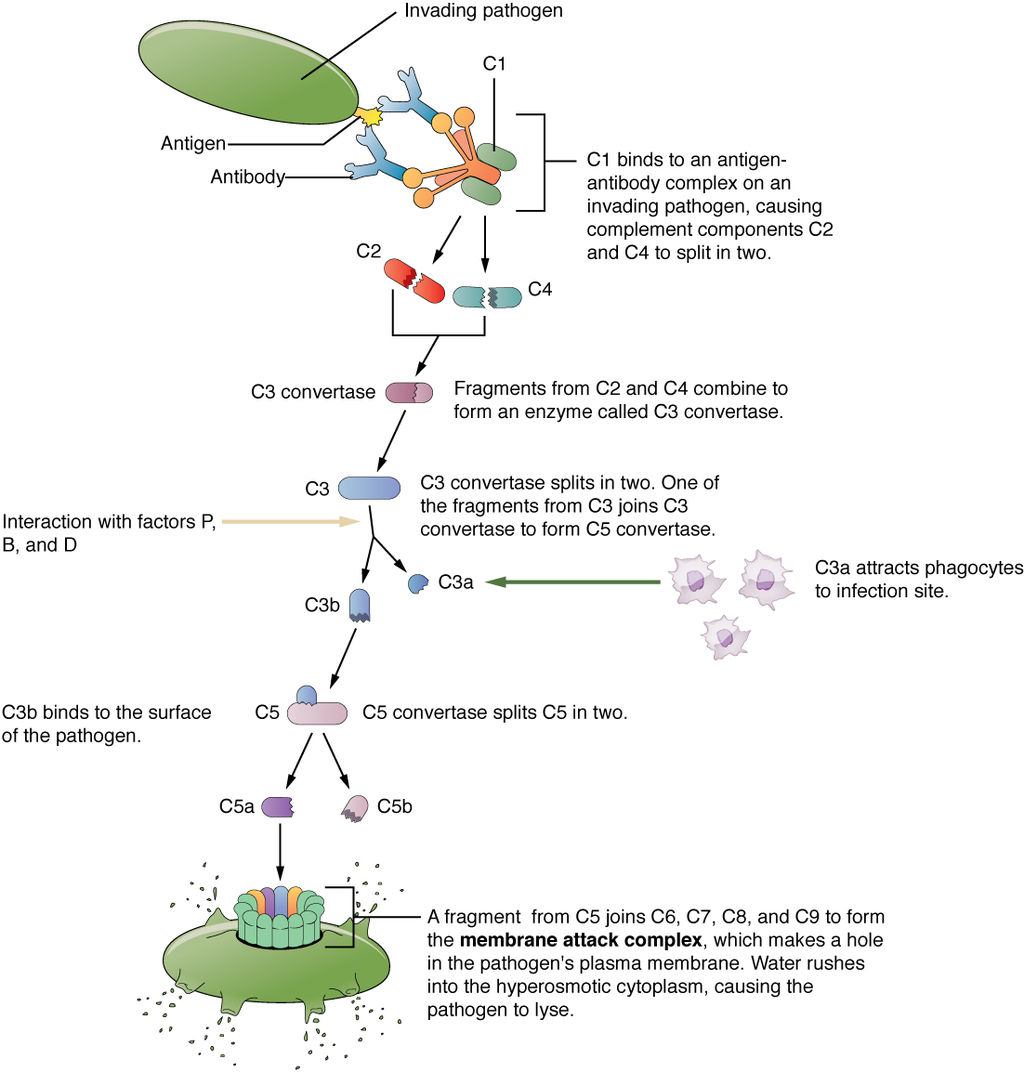

Complement System

The complement system is a complex biochemical mechanism named for its ability to “complement” the killing of pathogens by antibodies, which are produced as part of an adaptive immune response. The complement system consists of more than two dozen proteins normally found in the blood and synthesized in the liver. The proteins usually circulate as non-functional precursor molecules until activated.

As shown in Figure 17.4.5, when the first protein in the complement series is activated —typically by the binding of an antibody to an antigen on a pathogen — it sets in motion a domino effect. Each component takes its turn in a precise chain of steps known as the complement cascade. The end product is a cylinder that punctures a hole in the pathogen’s cell membrane. This allows fluids and molecules to flow in and out of the cell, which swells and bursts.

Cellular Responses

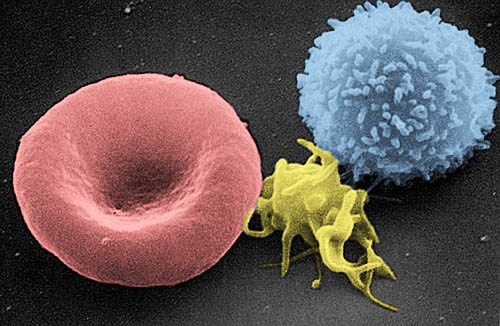

Cellular responses of the innate immune system involve a variety of different types of leukocytes. Many of these leukocytes circulate in the blood and act like independent, single-celled organisms, searching out and destroying pathogens in the human host. These and other immune cells of the innate system identify pathogens or debris, and then help to eliminate them in some way. One way is by phagocytosis.

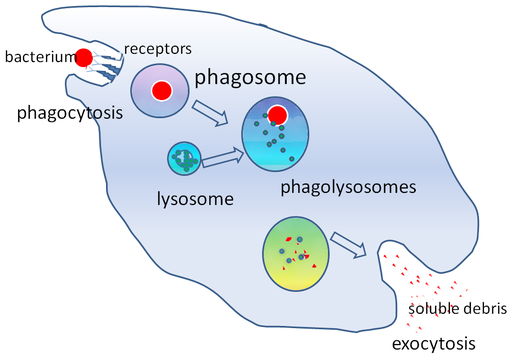

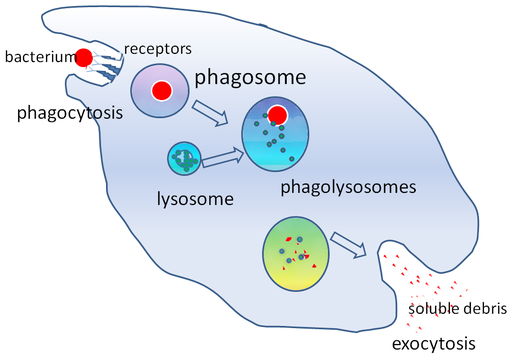

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis is an important feature of innate immunity that is performed by cells classified as phagocytes. In the process of phagocytosis, phagocytes engulf and digest pathogens or other harmful particles. Phagocytes generally patrol the body searching for pathogens, but they can also be called to specific locations by the release of cytokines when inflammation occurs. Some phagocytes reside permanently in certain tissues.

As shown in Figure 17.4.6, when a pathogen such as a bacterium is encountered by a phagocyte, the phagocyte extends a portion of its plasma membrane, wrapping the membrane around the pathogen until it is enveloped. Once inside the phagocyte, the pathogen becomes enclosed within an intracellular vesicle called a phagosome. The phagosome then fuses with another vesicle called a lysosome, forming a phagolysosome. Digestive enzymes and acids from the lysosome kill and digest the pathogen in the phagolysosome. The final step of phagocytosis is excretion of soluble debris from the destroyed pathogen through exocytosis.

Types of leukocytes that kill pathogens by phagocytosis include neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells. You can see illustrations of these and other leukocytes involved in innate immune responses in Figure 17.4.7.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are leukocytes that travel throughout the body in the blood. They are usually the first immune cells to arrive at the site of an infection. They are the most numerous types of phagocytes, and they normally make up at least half of the total circulating leukocytes. The bone marrow of a normal healthy adult produces more than 100 billion neutrophils per day. During acute inflammation, more than ten times that many neutrophils may be produced each day. Many neutrophils are needed to fight infections, because after a neutrophil phagocytizes just a few pathogens, it generally dies.

Macrophages

Macrophages are large phagocytic leukocytes that develop from monocytes. Macrophages spend much of their time within the interstitial fluid in body tissues. They are the most efficient phagocytes, and they can phagocytize substantial numbers of pathogens or other cells. Macrophages are also versatile cells that produce a wide array of chemicals — including enzymes, complement proteins, and cytokines — in addition to their phagocytic action. As phagocytes, macrophages act as scavengers that rid tissues of worn-out cells and other debris, as well as pathogens. In addition, macrophages act as antigen-presenting cells that activate the adaptive immune system.

Dendritic Cells

Like macrophages, dendritic cells develop from monocytes. They reside in tissues that have contact with the external environment, so they are located mainly in the skin, nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines. Besides engulfing and digesting pathogens, dendritic cells also act as antigen-presenting cells that trigger adaptive immune responses.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils are non-phagocytic leukocytes that are related to neutrophil. They specialize in defending against parasites. They are very effective in killing large parasites (such as worms) by secreting a range of highly-toxic substances when activated. Eosinophils may become overactive and cause allergies or asthma.

Basophils

Basophils are non-phagocytic leukocytes that are also related to neutrophils. They are the least numerous of all white blood cells. Basophils secrete two types of chemicals that aid in body defenses: histamines and heparin. Histamines are responsible for dilating blood vessels and increasing their permeability in inflammation. Heparin inhibits blood clotting, and also promotes the movement of leukocytes into an area of infection.

Mast Cells

Mast cells are non-phagocytic leukocytes that help initiate inflammation by secreting histamines. In some people, histamines trigger allergic reactions, as well as inflammation. Mast cells may also secrete chemicals that help defend against parasites.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer cells are in the subset of leukocytes called lymphocytes, which are produced by the lymphatic system. Natural killer cells destroy cancerous or virus-infected host cells, although they do not directly attack invading pathogens. Natural killer cells recognize these host cells by a condition they exhibit called “missing self.” Cells with missing self have abnormally low levels of cell-surface proteins of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which normally identify body cells as self.

Innate Immune Evasion

Many pathogens have evolved mechanisms that allow them to evade human hosts' innate immune systems. Some of these mechanisms include:

- Invading host cells to replicate so they are “hidden” from the immune system. The bacterium that causes tuberculosis uses this mechanism.

- Forming a protective capsule around themselves to avoid being destroyed by immune system cells. This defense occurs in bacteria, such as Salmonella species.

- Mimicking host cells so the immune system does not recognize them as foreign. Some species of Staphylococcus bacteria use this mechanism.

- Directly killing phagocytes. This ability evolved in several species of bacteria, including the species that causes anthrax.

- Producing molecules that prevent the formation of interferons, which are immune chemicals that fight viruses. Some influenza viruses have this capability.

- Forming complex biofilms that provide protection from the cells and proteins of the immune system. This characterizes some species of bacteria and fungi. You can see an example of a bacterial biofilm on teeth in Figure 17.4.8.

17.4 Summary

- The innate immune system is a subset of the human immune system that produces rapid, but non-specific responses to pathogens. Unlike the adaptive immune system, the innate system does not confer immunity. The innate immune system includes surface barriers, inflammation, the complement system, and a variety of cellular responses.

- The body’s first line of defense consists of three different types of barriers that keep most pathogens out of body tissues. The types of barriers are mechanical, chemical, and biological barriers.

- Mechanical barriers — which include the skin, mucous membranes, and fluids such as tears and urine — physically block pathogens from entering the body. Chemical barriers — such as enzymes in sweat, saliva, and semen — kill pathogens on body surfaces. Biological barriers are harmless bacteria that use up food and space so pathogenic bacteria cannot colonize the body.

- If pathogens breach protective barriers, inflammation occurs. This creates a physical barrier against the spread of infection, and repairs tissue damage. Inflammation is triggered by chemicals such as cytokines and histamines, and it causes swelling, redness, and warmth.

- The complement system is a complex biochemical mechanism that helps antibodies kill pathogens. Once activated, the complement system consists of more than two dozen proteins that lead to disruption of the cell membrane of pathogens and bursting of the cells.

- Cellular responses of the innate immune system involve various types of leukocytes. For example, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells phagocytize pathogens. Basophils and mast cells release chemicals that trigger inflammation. Natural killer cells destroy cancerous or virus-infected cells, and eosinophils kill parasites.

- Many pathogens have evolved mechanisms that help them evade the innate immune system. For example, some pathogens form a protective capsule around themselves, and some mimic host cells so the immune system does not recognize them as foreign.

17.4 Review Questions

- What is the innate immune system?

- Identify the body’s first line of defense.

-

- What are biological barriers? How do they protect the body?

- State the purposes of inflammation. What triggers inflammation, and what signs and symptoms does it cause?

- Define the complement system. How does it help destroy pathogens?

- Describe two ways that pathogens can evade the innate immune system.

- What are the ways in which phagocytes can encounter pathogens in the body?

- Describe two different ways in which enzymes play a role in the innate immune response.

17.4 Explore More

https://youtu.be/WW4skW6gucU

How mucus keeps us healthy - Katharina Ribbeck, TED-Ed, 2015.

https://youtu.be/sYjtMP67vyk

Human Physiology - Innate Immune System, Janux, 2015.

https://youtu.be/c64M1tZyWPM

Myriam Sidibe: The simple power of handwashing, TED, 2014.

https://youtu.be/shEPwQPQG4I

Everything You Didn't Want To Know About Snot, Gross Science, 2017.

https://youtu.be/dy1D3d1FBcw

Cough Grosser Than Sneeze? | Curiosity - World's Dirtiest Man, Discovery, 2011.

Attributions

Figure 17.4.1

Oww_Papercut_14365 by Laurence Facun on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 17.4.2

hairy-nose by Piotr Siedlecki on publicdomainpictures.net is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) license.

Figure 17.4.3

1024px-Sneeze by James Gathany/ CDC Public Health Image library (PHIL) ID# 11162 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 17.4.4

OSC_Microbio_17_06_Erythema by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 17.4.5

2212_Complement_Cascade_and_Function by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 17.4.6

512px-Phagocytosis2 by Graham Colm at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 17.4.7

Innate_Immune_cells.svg by Fred the Oyster on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 17.4.8

1024px-Gingivitis-before-and-after-3 by Onetimeuseaccount on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) license.

References