18.10 Infertility

Figure 18.10.1 Families all have something in common.

Family Portrait

What do all these families (Figure 18.10.1) have in common? They were born! Every person on this planet was conceived, carried in utero and then born. While families come in all shapes, sizes and styles, we all came into existence in the same way. Virtually all human societies past and present — value having children. Indeed, for many people, parenthood is an important life goal. Unfortunately, some people are unable to achieve that goal because of infertility.

What Is Infertility?

Infertility is the inability of a sexually mature adult to reproduce by natural means. For scientific and medical purposes, infertility is generally defined as the failure to achieve a successful pregnancy after at least one year of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse. Infertility may be primary or secondary. Primary infertility applies to cases in which an individual has never achieved a successful pregnancy. Secondary infertility applies to cases in which an individual has had at least one successful pregnancy, but fails to achieve another after trying for at least a year. Infertility is a common problem. The government of Canada reported that in 2019, 16% of Canadian couples experience infertility, a number which has doubled since the 1980s. If you look around at the couples you know, that means that almost 1 in 6 of them are having issues with fertility.

Causes of Infertility

Pregnancy is the result of a multi-step process. In order for a normal pregnancy to occur, a woman must release an ovum from one of her ovaries, the ovum must go through an oviduct, a man’s sperm must fertilize the ovum as it passes through the oviduct, and then the resulting zygote must implant in the uterus. If there is a problem with any of these steps, infertility can result.

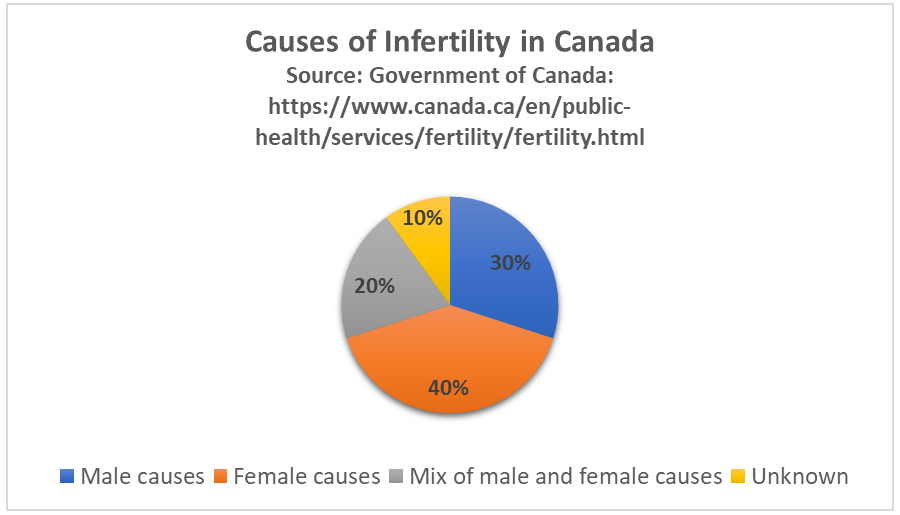

A couple’s infertility may be due to a problem with either the male or the female partner. As shown in the circle graph below (Figure 18.10.2), about 40% of infertility cases are due to female infertility, and about 30% are due to male infertility. The remaining 30% of cases are due to a combination of male and female problems or unknown causes.

Causes of Male Infertility

Male infertility occurs when there are no, or too few, sperm, or when the sperm are not healthy and motile and cannot travel through the female reproductive tract to fertilize an egg. A common cause of inadequate numbers or motility of sperm is varicocele, which is enlargement of blood vessels in the scrotum. This may raise the temperature of the testes and adversely affect sperm production. In other cases, there is no problem with the sperm, but there is a blockage in the male reproductive tract that prevents the sperm from being ejaculated.

Factors that increase a man’s risk of infertility include heavy alcohol use, drug abuse, cigarette smoking, exposure to environmental toxins (such as pesticides or lead), certain medications, serious diseases (such as kidney disease), and radiation or chemotherapy for cancer. Another risk factor is advancing age. Male fertility normally peaks in the mid-twenties and gradually declines after about age 40, although it may never actually drop to zero.

Causes of Female Infertility

Female infertility generally occurs due to one of two problems: failure to produce viable ova by the ovaries, or structural problems in the oviducts or uterus. The most common cause of female infertility is a problem with ovulation. Without ovulation, there are no ova to be fertilized. Anovulatory cycles (menstrual cycles in which ovulation does not occur) may be associated with no or irregular menstrual periods, but even regular menstrual periods may be anovulatory for a variety of reasons. The most common cause of anovulatory cycles is polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which causes hormone imbalances that can interfere with normal ovulation. Another relatively common cause of anovulation is primary ovarian insufficiency. In this condition, the ovaries stop working normally and producing viable eggs at a relatively early age, generally before the age of 40.

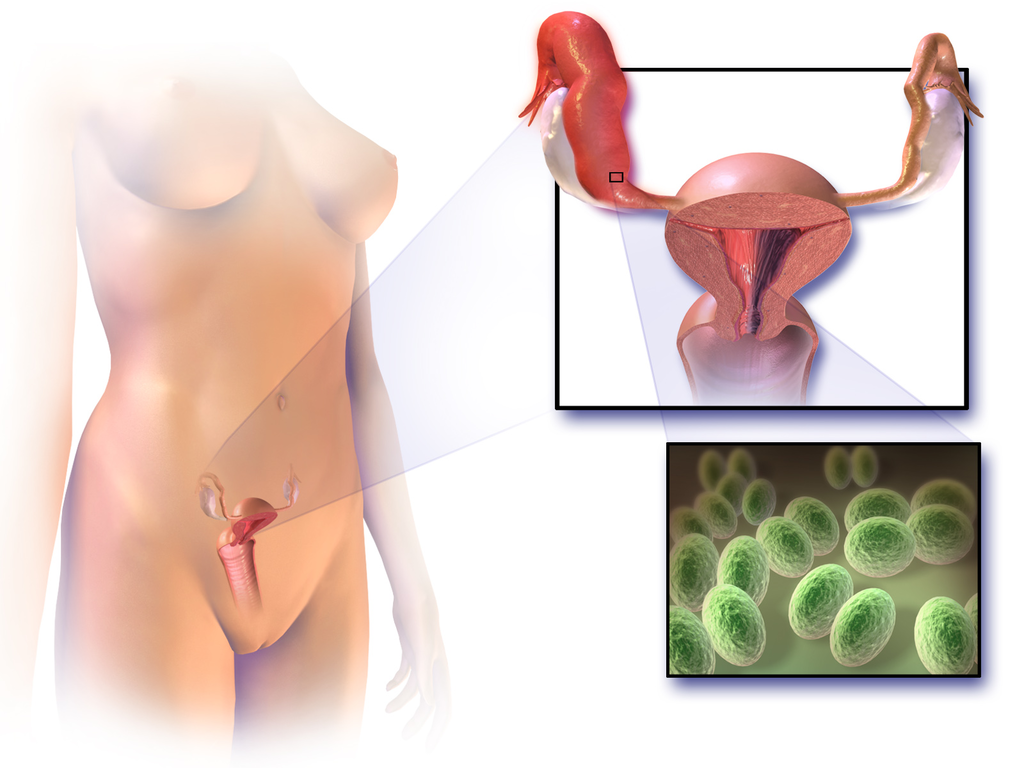

Structural problems with the oviducts or uterus are less common causes of female infertility. The oviducts may be blocked as a result of endometriosis. Another possible cause is pelvic inflammatory disease, which occurs when sexually transmitted infections spread to the oviducts or other female reproductive organs (see Figure 18.10.3). The infection may lead to scarring and blockage of the oviducts. If an ovum is produced and the oviducts are functioning — and a woman has a condition such as uterine fibroids — implantation in the uterus may not be possible. Uterine fibroids are non-cancerous clumps of tissue and muscle that form on the walls of the uterus.

Factors that increase a woman’s risk of infertility include tobacco smoking, excessive use of alcohol, stress, poor diet, strenuous athletic training, and being overweight or underweight. Advanced age is even more problematic for females than males. Female fertility normally peaks in the mid-twenties, and continuously declines after age 30 and until menopause around the age of 52, after which the ovary no longer releases eggs. About 1/3 of couples in which the woman is over age 35 have fertility problems. In older women, more cycles are likely to be anovulatory, and the eggs may not be as healthy.

Diagnosing Causes of Infertility

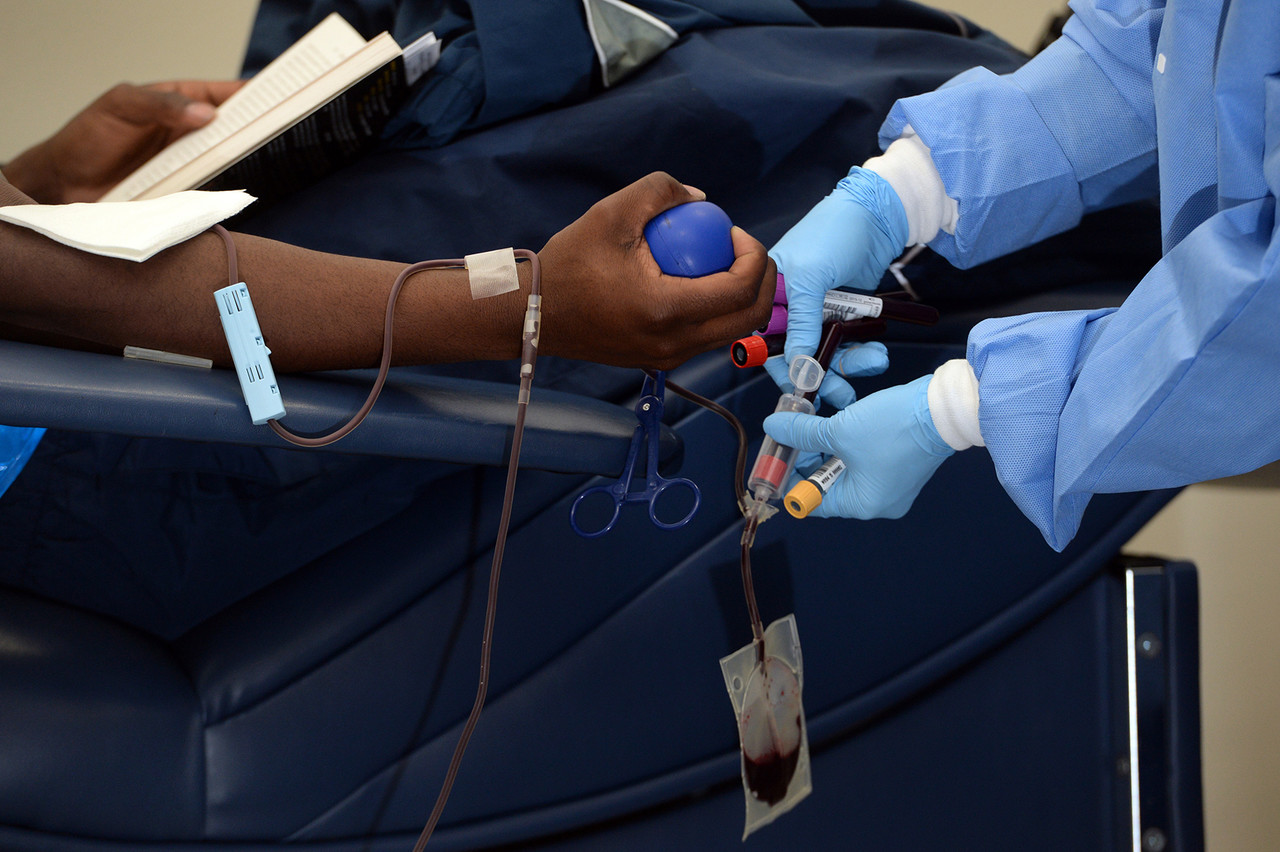

Diagnosing the cause(s) of a couple’s infertility often requires testing both the man and the woman for potential problems. In men, the semen is likely to be examined for the number, shape, and motility of sperm. If problems are found with sperm, further studies are likely to be done, such as medical imaging to look for structural problems with the testes or ducts.

In women, the first step is most often determining whether ovulation is occurring. This can be done at home by carefully monitoring body temperature (it rises slightly around the time of ovulation) or using a home ovulation test kit, which is available over the counter at most drugstores. Whether or not ovulation is occurring can also be detected with blood tests or ultrasound imaging of the ovaries. If ovulation is occurring normally, then the next step may be an X-ray of the oviducts and uterus to see if there are any blockages or other structural problems. Another approach to examining the female reproductive tract for potential problems is laparoscopy. In this surgical procedure, a tiny camera is inserted into the woman’s abdomen through a small incision. This allows the doctor to directly inspect the reproductive organs.

Treating Infertility

Infertility often can be treated successfully. The type of treatment depends on the cause of infertility.

Treating Male Infertility

Medical problems that interfere with sperm production may be treated with medications or other interventions that may lead to the resumption of normal sperm production. If, for example, an infection is interfering with sperm production, then antibiotics that clear up the infection may resolve the problem. If there is a blockage in the male reproductive tract that prevents the ejaculation of sperm, surgery may be able to remove the blockage. Alternatively, the man’s sperm may be removed from his body and then used for artificial insemination of his partner. In this procedure, the sperm are injected into the woman’s reproductive tract.

Treating Female Infertility

In females, it may be possible to correct blocked Fallopian tubes or uterine fibroids with surgery. Ovulation problems, on the other hand, are usually treated with hormones that act either on the pituitary gland or on the ovaries. Hormonal treatments that stimulate ovulation often result in more than one egg being ovulated at a time, thus increasing the chances of a woman having twins, triplets, or even higher multiple births. Multiple fetuses are at greater risk of being born too early or having health and developmental problems. The mother is also at greater risk of complications arising during pregnancy. Therefore, the possibility of multiple fetuses should be weighed in making a decision about this type of infertility treatment.

Assisted Reproductive Technology

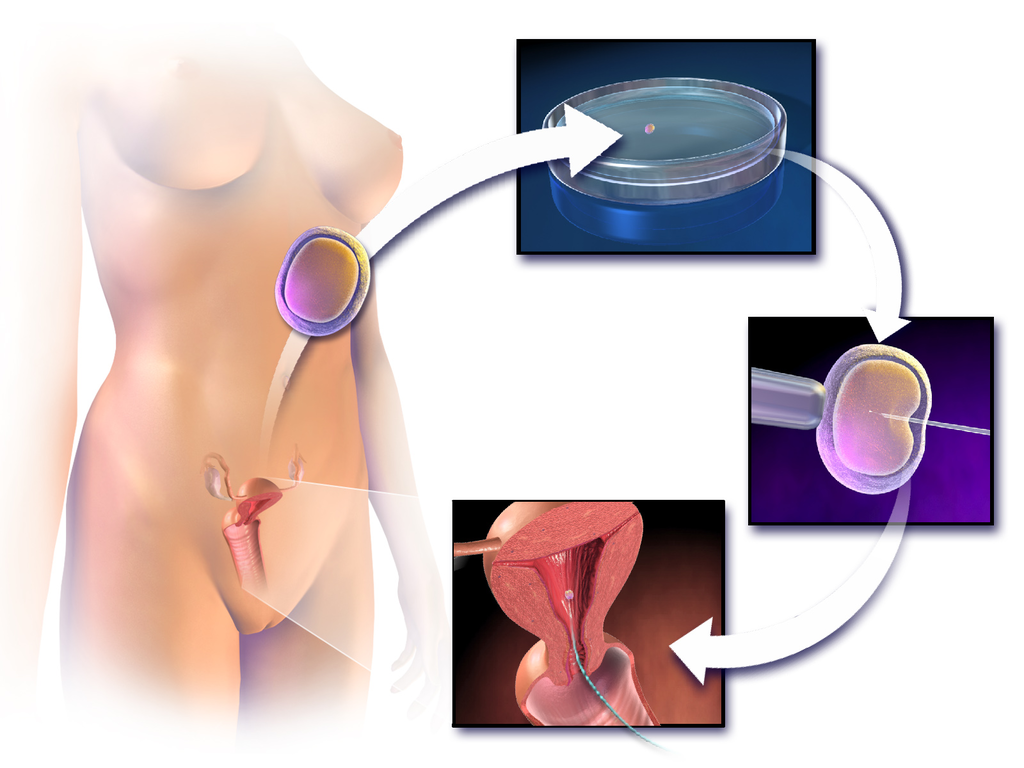

Some cases of infertility are treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART). This is a collection of medical procedures in which ova are removed from the woman’s body and sperm are taken from the man’s body to be manipulated in ways that increase the chances of fertilization occurring. The eggs and sperm may be injected into one of the woman’s oviducts for fertilization to take place in vivo (in the body). More commonly, however, the eggs and sperm are mixed together outside the body so fertilization takes place in vitro (in a test tube or dish in a lab). The latter approach is illustrated in Figure 18.10.4. With in vitro fertilization, the fertilized eggs may be allowed to develop into embryos before being placed in the woman’s uterus.

ART has about a 40% chance of leading to a live birth in women under the age of 35, but only about a 20%t chance of success in women over the age of 35. Some studies have found a higher-than-average risk of birth defects in children produced by ART procedures, but this may be due to the generally higher ages of the parent — not the technologies used.

Other Approaches

Other approaches for certain causes of infertility include the use of a surrogate mother, a gestational carrier, or sperm donation.

- A surrogate mother is a woman who agrees to become pregnant using the man’s sperm and her own egg. The child, who will be the biological offspring of the surrogate and the male partner, is given up at birth for adoption by the couple. Surrogacy might be selected by women with no eggs or unhealthy eggs. A woman who carries a mutant gene for a serious genetic disorder might choose this option to ensure that the defective gene is not passed on to the offspring.

- A gestational carrier is a woman who agrees to receive a transplanted embryo from a couple and carry it to term. The child, who will be the biological offspring of the couple, is given to the parents at birth. A gestational carrier might be used by women who have normal ovulation but no uterus, or who cannot safely carry a fetus to term because of a serious health problem (such as kidney disease or cancer).

- Sperm donation is the use of sperm from a fertile man (generally through artificial insemination) for cases in which the male partner in a couple is infertile, or in which a woman seeks to become pregnant without a male partner. A lesbian couple may use donated sperm to enable one of them to become pregnant and have a child. Sperm can be obtained from a sperm bank, which buys and stores sperm for artificial insemination, or a male friend or other individual may donate sperm to a specific woman.

Social and Ethical Issues Relating to Infertility

For people who have a strong desire for children of their own, infertility may lead to deep disappointment and depression. Individuals who are infertile may even feel biologically inadequate. Partners in infertile couples may argue and feel resentment toward each other, and married couples may get divorced because of infertility. Infertility treatments — especially ART procedures — are generally time-consuming and expensive. The high cost of the treatments can put them out of financial reach of many couples.

Ethical Concerns

Some people question whether the allocation of medical resources to infertility treatments is justified, and whether the resources could be better used in other ways. The status of embryos that are created in vitro and then not used for a pregnancy is another source of debate. Some people oppose their destruction on religious grounds, and couples may sometimes argue about what should be done with their extra embryos. Ethical issues are also raised by procedures that increase the chances of multiple births, because of the medical and developmental risks associated with multiple births.

Infertility in Developing Countries

Infertility is an under-appreciated problem in the poorer nations of the world, because of assumptions about overpopulation problems and high birth rates in developing countries. In fact, infertility is at least as great a problem in developing as in developed countries. High rates of health problems and inadequate health care in the poorer nations increase the risk of infertility. At the same time, infertility treatments are usually not available — or are far too expensive — for the vast majority of people who may need them. In addition, in many developing countries, the production of children is highly valued. Children may be needed for family income generation and economic security of the elderly. It is not uncommon for infertility to lead to social stigmatization, psychological problems, and abandonment by spouses.

18.10 Summary

- Infertility is the inability of a sexually mature adult to reproduce by natural means. It is defined scientifically and medically as the failure to achieve a successful pregnancy after at least one year of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse.

- About 40% of infertility in couples is due to female infertility, and another 30% is due to male infertility. In the remaining cases, a couple’s infertility is due to problems in both partners, or to unknown causes.

- Male infertility occurs when there are no, or too few, healthy, motile sperm. This may be caused by problems with spermatogenesis, or by blockage of the male reproductive tract that prevents sperm from being ejaculated. Risk factors for male infertility include heavy alcohol use, smoking, certain medications, and advancing age, to name just a few.

- Female infertility occurs due to failure to produce viable ova by the ovaries, or structural problems in the oviducts or uterus. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of failure to produce viable ova. Endometriosis and uterine fibroids are possible causes of structural problems in the oviducts and uterus. Risk factors for female infertility include smoking, stress, poor diet, and older age, among others.

- Diagnosing the cause(s) of a couple’s infertility generally requires testing both the man and the woman for potential problems. For men, semen is likely to be examined for adequate numbers of healthy, motile sperm. For women, signs of ovulation are monitored, for example, with an ovulation test kit or ultrasound of the ovaries. For both partners, the reproductive tract may be medically imaged to look for blockages or other abnormalities.

- Treatments for infertility depend on the cause. For example, if a medical problem is interfering with sperm production, medication may resolve the underlying problem so sperm production is restored. Blockages in either the male or the female reproductive tract can often be treated surgically. If there are problems with ovulation, hormonal treatments may stimulate ovulation.

- Some cases of infertility are treated with assisted reproductive technology (ART). This is a collection of medical procedures in which ova and sperm are taken from the couple and manipulated in a lab to increase the chances of fertilization occurring and an embryo forming. Other approaches for certain causes of infertility include the use of a surrogate mother, gestational carrier, or sperm donation.

- Infertility can negatively impact a couple socially and psychologically, and it may be a major cause of marital friction or even divorce. Infertility treatments may raise ethical issues relating to the costs of the procedures and the status of embryos that are created in vitro, but not used for pregnancy. Infertility is an under-appreciated problem in developing countries, where birth rates are high and children have high economic — as well as social — value. In these countries, poor health care is likely to lead to more problems with infertility and fewer options for treatment.

18.10 Review Questions

- What is infertility? How is infertility defined scientifically and medically?

- What percentage of infertility in couples is due to male infertility? What percentage is due to female infertility?

- Identify causes of and risk factors for male infertility.

- Identify causes of and risk factors for female infertility.

- How are causes of infertility in couples diagnosed?

- How is infertility treated?

- Discuss some of the social and ethical issues associated with infertility or its treatment.

- Why is infertility an under-appreciated problem in developing countries?

- Describe two similarities between causes of male and female infertility.

- Explain the difference between males and females in terms of how age affects fertility.

-

- Do you think that taking medication to stimulate ovulation is likely to improve fertility in cases where infertility is due to endometriosis? Explain your answer.

18.10 Explore More

How in vitro fertilization (IVF) works – Nassim Assefi and Brian A. Levine, TED-Ed, 2015

A journey through infertility — over terror’s edge | Camille Preston | TEDxBeaconStreet, TEDx Talks, 2014.

Smoking Marijuana May Lower Sperm Count by 33%, David Pakman Show, 2015.

ivf embryo developing over 5 days by fertility Dr Raewyn Teirney, Fertility Specialist Sydney, 2014.

Homosexuality: It’s about survival – not sex | James O’Keefe | TEDxTallaght, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 18.10.1

- Gay Pride Parade NYC 2013 – Happy Family by Bob Jagendorf on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

- #beaches #summer #family #blue #water by Jove Duero on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Photograph of five men near outdoor by Dollar Gill on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Família by Laercio Cavalcanti on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Happiness 🙂 by Ashwini Chaudhary on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 18.10.2

Causes of infertility in Canada by Christine Miller is in the Public Domain (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/).

Figure 18.10.3

1024px-Blausen_0719_PelvicInflammatoryDisease by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 18.10.4

1024px-Blausen_0060_AssistedReproductiveTechnology by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

References

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

David Pakman Show. (2015, September 1). Smoking marijuana may lower sperm count by 33%. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iqA8uAjvEdM

Fertility Specialist Sydney. (2014, April 11). ivf embryo developing over 5 days by fertility Dr Raewyn Teirney. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V6-v4eF9dyA&t=5s

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2019, May 28). Fertility. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/fertility/fertility.html

TED-Ed. (2015, May 7). How in vitro fertilization (IVF) works – Nassim Assefi and Brian A. Levine. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P27waC05Hdk&t=4s

TEDx Talks. (2014, June 26). A journey through infertility — over terror’s edge | Camille Preston | TEDxBeaconStreet. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6BBmMtVfZ4Y&t=2s

TEDx Talks. (2016, November 15). Homosexuality: It’s about survival – not sex | James O’Keefe | TEDxTallaght. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Khn_z9FPmU&t=1s

Image shows a diagram of all the components of the endocrine system. This includes the pineal and pituitary glands in the brain, the thyroid gland surrounding the larynx, the thymus gland sitting above the heart, the adrenal glands sitting above the kidneys, the pancreas, and in females, the uterus and ovaries and in males the testes.

Image shows a two part diagram of inflammatory response. The first pane shows an initial injury to the skin and introduction of pathogens to deeper tissues. Mast cells release clouds of histamines into the tissue.

In the second pane, the capillaries have become more porous, due to the histamines. Leukocytes are squeezing out of the capillary into the injured tissue, where they will phagocytize any pathogens they come across.

http://humanbiology.pressbooks.tru.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2019/06/human-heartbeat-daniel_simon.mp3

Lub, Dub

Lub dub, lub dub, lub dub... That’s how the sound of a beating heart is typically described. Those are also the only two sounds that should be audible when listening to a normal, healthy heart through a stethoscope, as in Figure 14.3.1. If a doctor hears something different from the normal lub dub sounds, it’s a sign of a possible heart abnormality. What causes the heart to produce the characteristic lub dub sounds? Read on to find out.

Introduction to the Heart

The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum (breastbone), slightly to the left of the center of the chest. A normal adult heart is about the size of a fist. The function of the heart is to pump blood through blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. The continuous flow of blood through the system is necessary to provide all the cells of the body with oxygen and nutrients, and to remove their metabolic wastes.

Structure of the Heart

The heart has a thick muscular wall that consists of several layers of tissue. Internally, the heart is divided into four chambers through which blood flows. Because of heart valves, blood flows in just one direction through the chambers.

Heart Wall

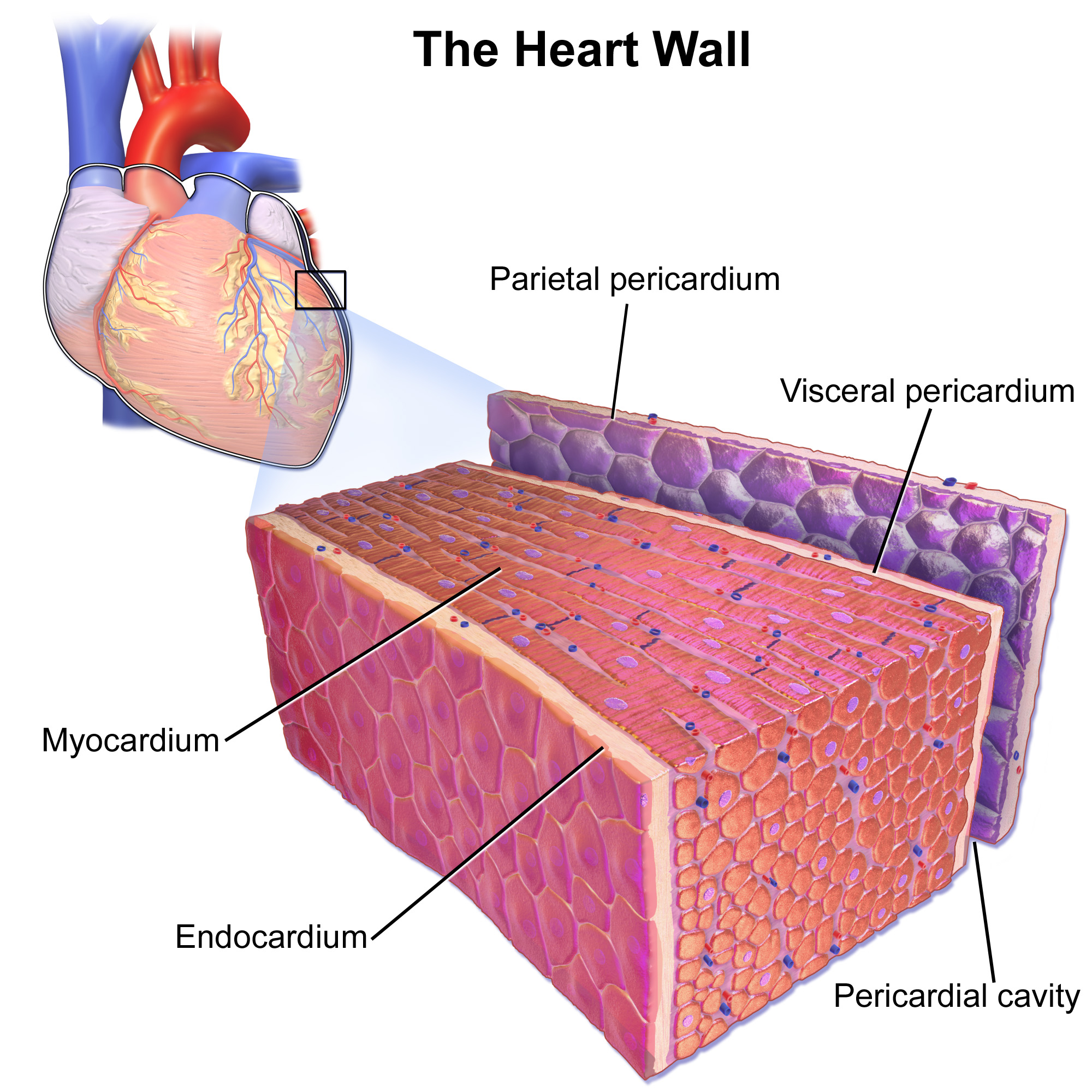

As shown in Figure 14.3.2, the wall of the heart is made up of three layers, called the endocardium, myocardium, and pericardium.

- The endocardium is the innermost layer of the heart wall. It is made up primarily of simple epithelial cells. It covers the heart chambers and valves. A thin layer of connective tissue joins the endocardium to the myocardium.

- The myocardium is the middle and thickest layer of the heart wall. It consists of cardiac muscle surrounded by a framework of collagen. There are two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium: cardiomyocytes — which have the ability to contract easily — and pacemaker cells, which conduct electrical impulses that cause the cardiomyocytes to contract. About 99 per cent of cardiac muscle cells are cardiomyocytes, and the remaining one per cent is pacemaker cells. The myocardium is supplied with blood vessels and nerve fibres via the pericardium.

- The pericardium is a protective sac that encloses and protects the heart. The pericardium consists of two membranes (visceral pericardium and parietal pericardium), between which there is a fluid-filled cavity. The fluid helps to cushion the heart, and also lubricates its outer surface.

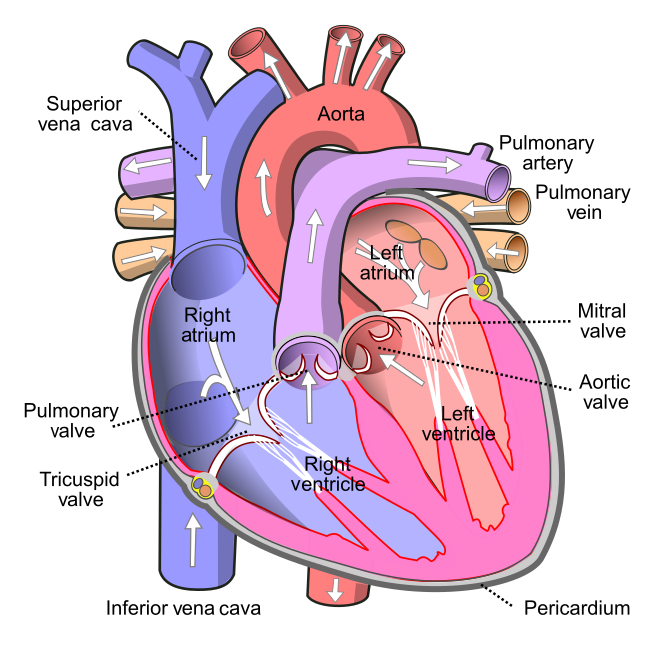

Heart Chambers

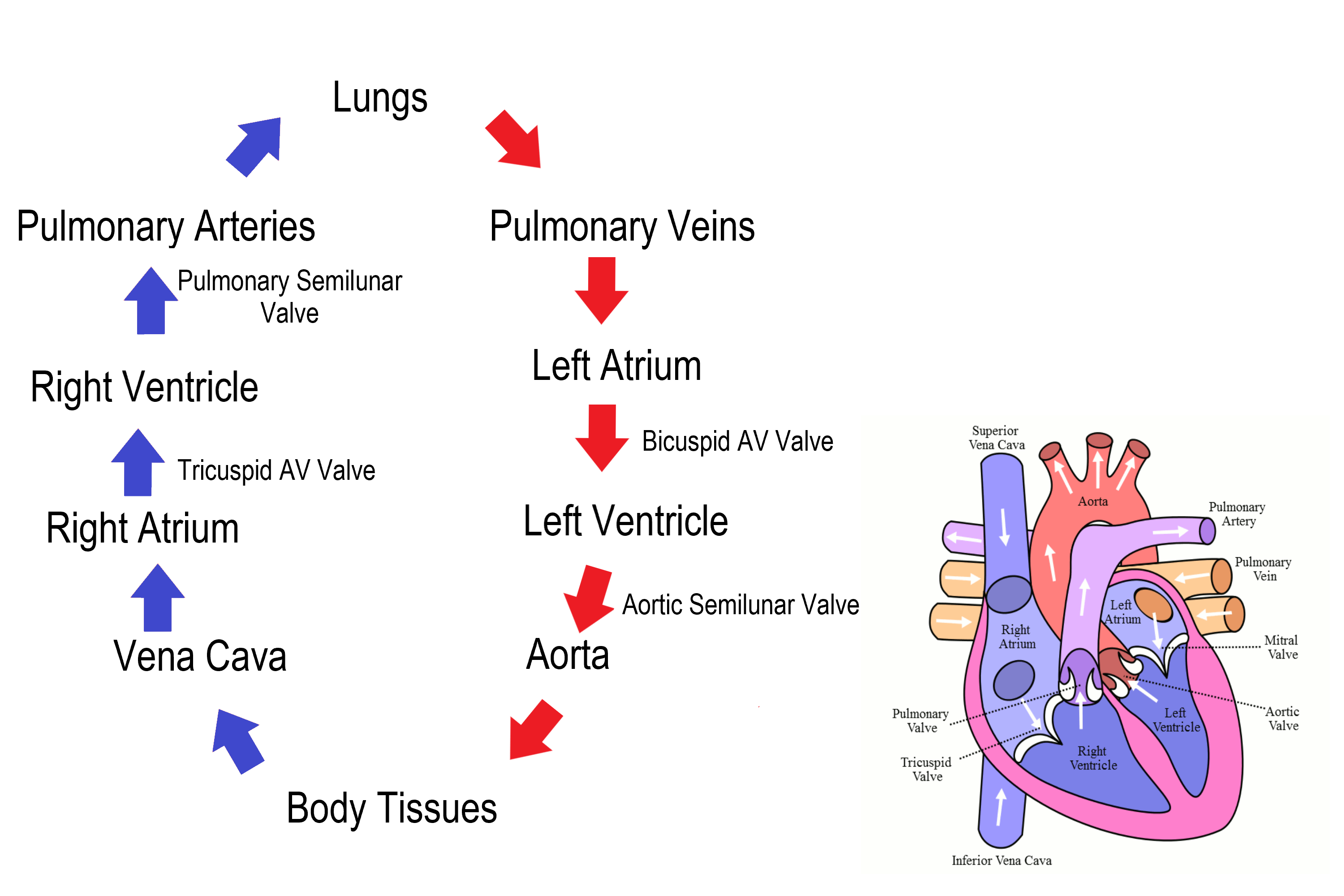

As shown in Figure 14.3.3 the four chambers of the heart include two upper chambers called atria (singular, atrium), and two lower chambers called ventricles. The atria are also referred to as receiving chambers, because blood coming into the heart first enters these two chambers. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the upper and lower body through the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, respectively. The left atrium receives oxygenated blood from the lungs through the pulmonary veins. The ventricles are also referred to as discharging chambers, because blood leaving the heart passes out through these two chambers. The right ventricle discharges blood to the lungs through the pulmonary artery, and the left ventricle discharges blood to the rest of the body through the aorta. The four chambers are separated from each other by dense connective tissue consisting mainly of collagen.

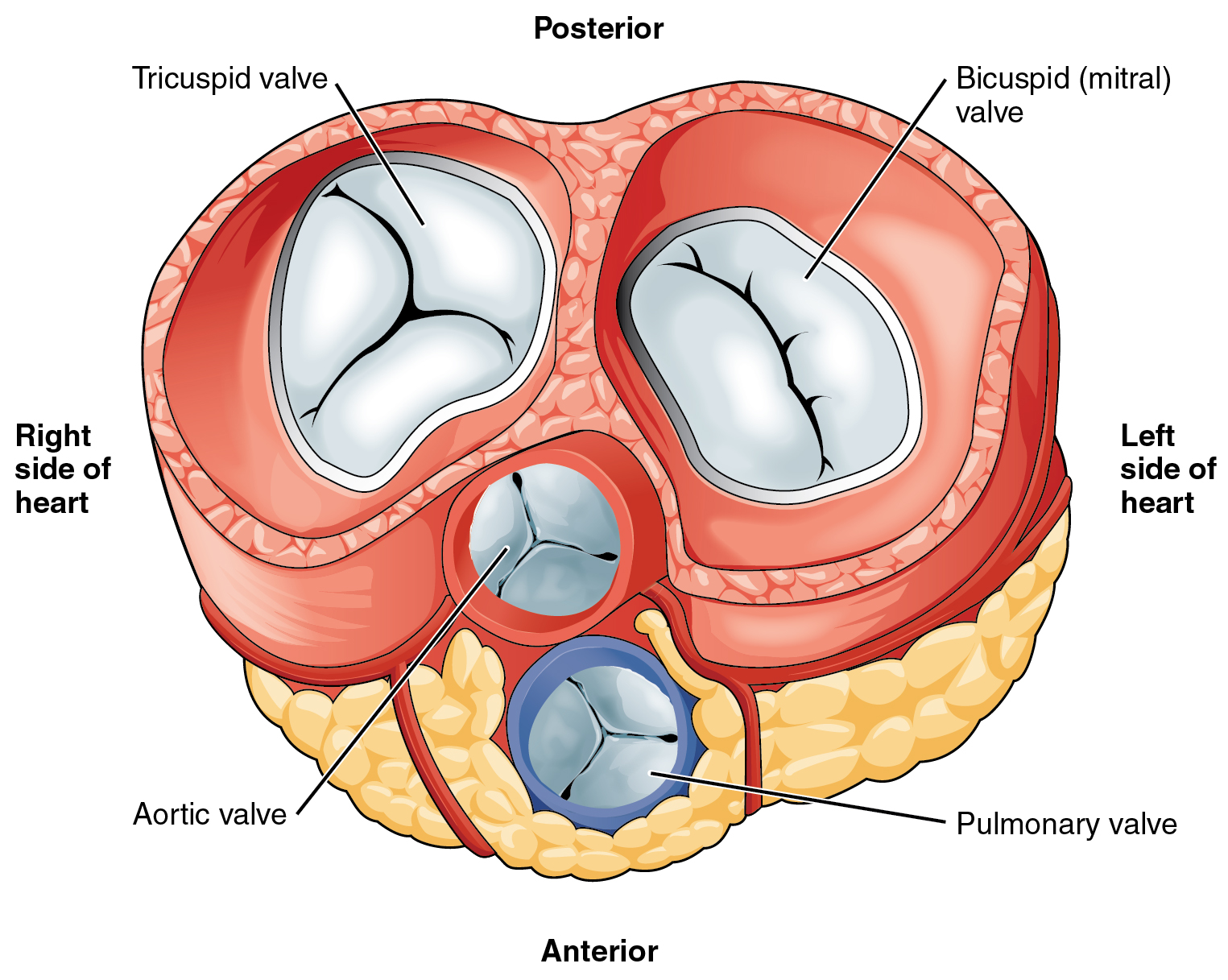

Heart Valves

Figure 14.3.4 shows the location of the heart's four valves in a top-down view, looking down at the heart as if the arteries and veins feeding into and out of the heart were removed. The heart valves allow blood to flow from the atria to the ventricles, and from the ventricles to the pulmonary artery and aorta. The valves are constructed in such a way that blood can flow through them in only one direction, thus preventing the backflow of blood. Figure 14.3.5 shows how valves open to let blood into the appropriate chamber, and then close to prevent blood from moving in the wrong direction and the next chamber contracts. The four valves are the:

- Tricuspid atrioventricular valve, (can be shortened to tricuspid AV valve) which allows blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle.

- Bicuspid atrioventricular valve (also know as the mitral valve), which allows blood to flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle.

- Pulmonary semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery.

- Aortic semilunar valve, which allows blood to flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

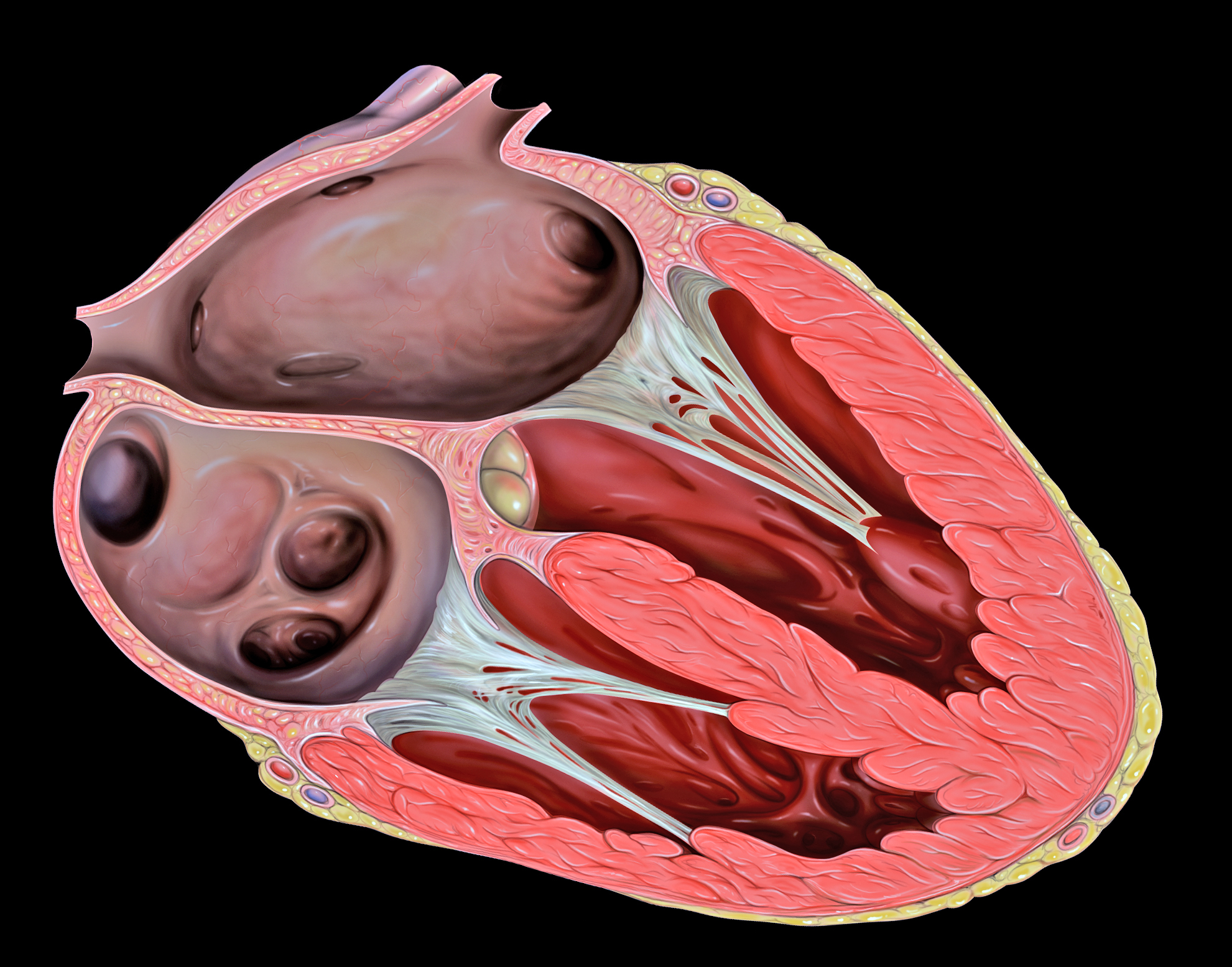

The two atrioventricular (AV) valves prevent backflow when the ventricles are contracting, while the semilunar valves prevent backflow from vessels. This means that the AV valves must withstand much more pressure than do the semilunar valves. In order to withstand the force of the ventricles contracting (to prevent blood from backflowing into the atria), the AV valves are reinforced with structures called chordae tendineae — tendon-like cords of connective tissue which anchor the valve and prevent it from prolapse. Figure 14.3.6 shows the structure and location of the chordae tendoneae.

The chordae tendoneae are under such force that they need special attachments to the interior of the ventricles where they anchor. Papillary muscles are specialized muscles in the interior of the ventricle that provide a strong anchor point for the chordae tendineae.

Coronary Circulation

The cardiomyocytes of the muscular walls of the heart are very active cells, because they are responsible for the constant beating of the heart. These cells need a continuous supply of oxygen and nutrients. The carbon dioxide and waste products they produce also must be continuously removed. The blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells make up the coronary circulation. Note that the blood vessels of the coronary circulation supply heart tissues with blood, and are different from the blood vessels that carry blood to and from the chambers of the heart as part of the general circulation. Coronary arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscle cells. Coronary veins remove deoxygenated blood from the heart muscles cells.

- There are two coronary arteries — a right coronary artery that supplies the right side of the heart, and a left coronary artery that supplies the left side of the heart. These arteries branch repeatedly into smaller and smaller arteries and finally into capillaries, which exchange gases, nutrients, and waste products with cardiomyocytes.

- At the back of the heart, small cardiac veins drain into larger veins, and finally into the great cardiac vein, which empties into the right atrium. At the front of the heart, small cardiac veins drain directly into the right atrium.

Blood Circulation Through the Heart

Figure 14.3.7 shows how blood circulates through the chambers of the heart. The right atrium collects blood from two large veins, the superior vena cava (from the upper body) and the inferior vena cava (from the lower body). The blood that collects in the right atrium is pumped through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. From the right ventricle, the blood is pumped through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery. The pulmonary artery carries the blood to the lungs, where it enters the pulmonary circulation, gives up carbon dioxide, and picks up oxygen. The oxygenated blood travels back from the lungs through the pulmonary veins (of which there are four), and enters the left atrium of the heart. From the left atrium, the blood is pumped through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From the left ventricle, the blood is pumped through the aortic valve into the aorta, which subsequently branches into smaller arteries that carry the blood throughout the rest of the body. After passing through capillaries and exchanging substances with cells, the blood returns to the right atrium via the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava, and the process begins anew.

Cardiac Cycle

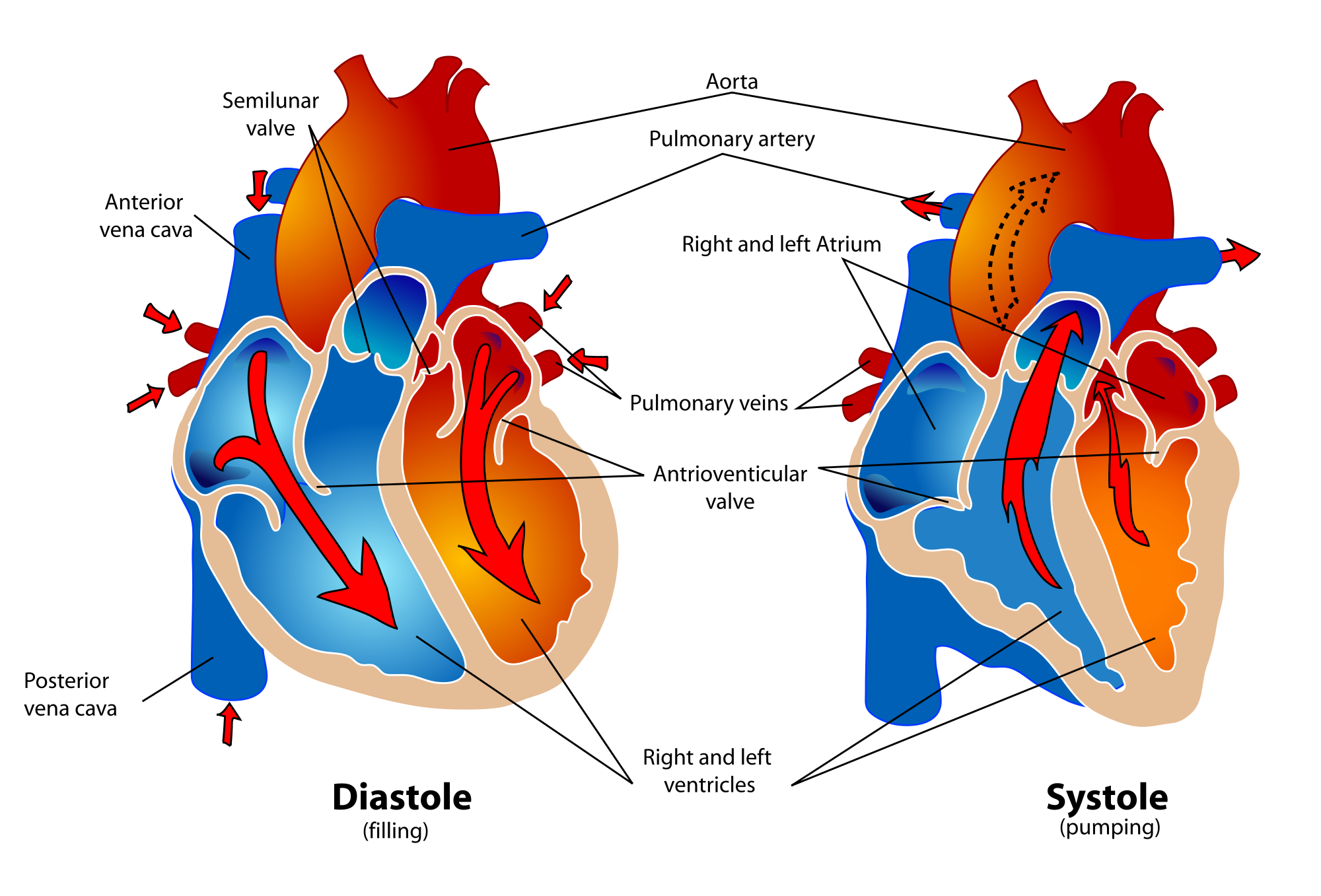

The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat, which includes one iteration of the lub and dub sounds heard through a stethoscope. During the cardiac cycle, the atria and ventricles work in a coordinated fashion so that blood is pumped efficiently through and out of the heart. The cardiac cycle includes two parts, called diastole and systole, which are illustrated in the diagrams in Figure 14.3.8.

- During diastole, the atria contract and pump blood into the ventricles, while the ventricles relax and fill with blood from the atria.

- During systole, the atria relax and collect blood from the lungs and body, while the ventricles contract and pump blood out of the heart.

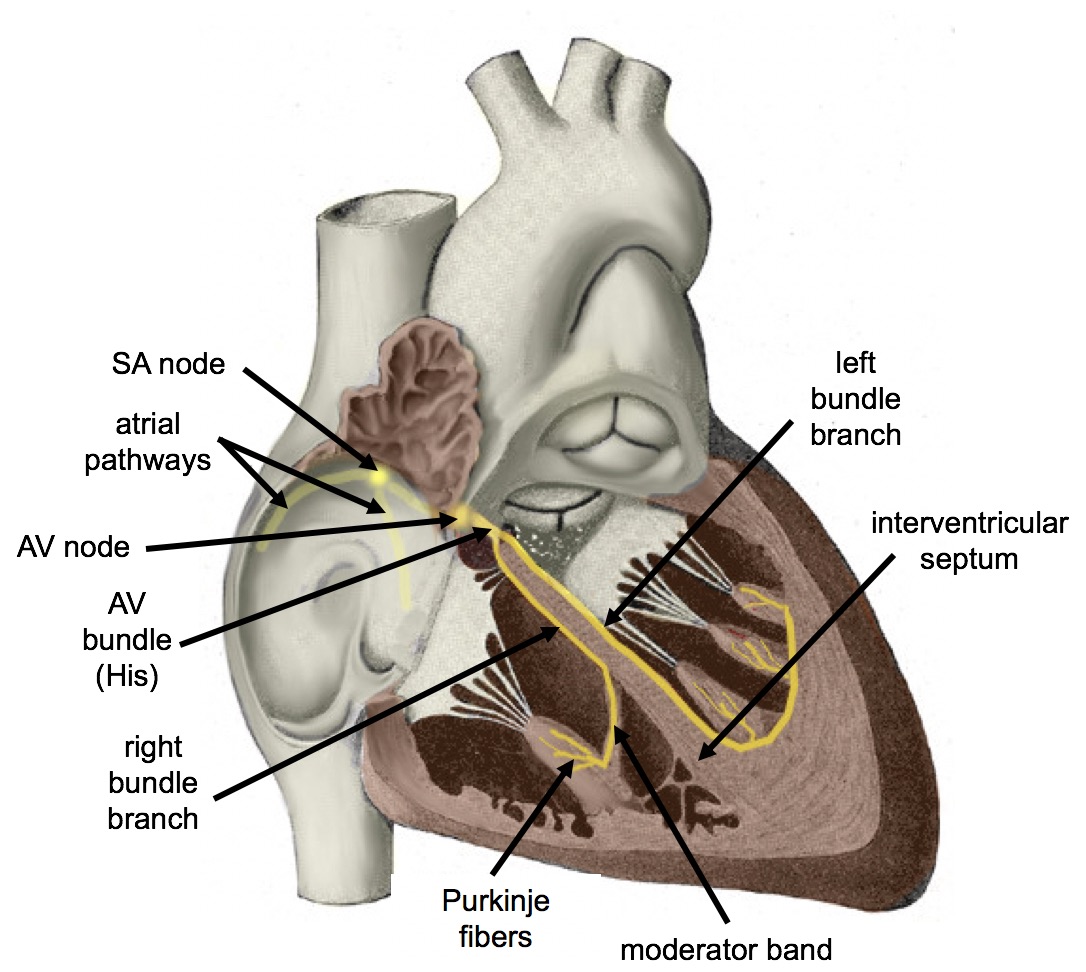

Electrical Stimulation of the Heart

The normal, rhythmical beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells, which are located in an area of the heart called the sinoatrial node (shown in Figure 14.3.9). The pacemaker cells create electrical signals with the movement of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, and calcium ions) into and out of the cells. For each cardiac cycle, an electrical signal rapidly travels first from the sinoatrial node, to the right and left atria so they contract together. Then, the signal travels to another node, called the atrioventricular node (Figure 14.3.9), and from there to the right and left ventricles (which also contract together), just a split second after the atria contract.

The normal sinus rhythm of the heart is influenced by the autonomic nervous system through sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. These nerves arise from two paired cardiovascular centers in the medulla of the brainstem. The parasympathetic nerves act to decrease the heart rate, and the sympathetic nerves act to increase the heart rate. Parasympathetic input normally predominates. Without it, the pacemaker cells of the heart would generate a resting heart rate of about 100 beats per minute, instead of a normal resting heart rate of about 72 beats per minute. The cardiovascular centers receive input from receptors throughout the body, and act through the sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, as needed. Increased physical activity, for example, is detected by receptors in muscles, joints, and tendons. These receptors send nerve impulses to the cardiovascular centers, causing sympathetic nerves to increase the heart rate, and allowing more blood to flow to the muscles.

Besides the autonomic nervous system, other factors can also affect the heart rate. For example, thyroid hormones and adrenal hormones (such as epinephrine) can stimulate the heart to beat faster. The heart rate also increases when blood pressure drops or the body is dehydrated or overheated. On the other hand, cooling of the body and relaxation — among other factors — can contribute to a decrease in the heart rate.

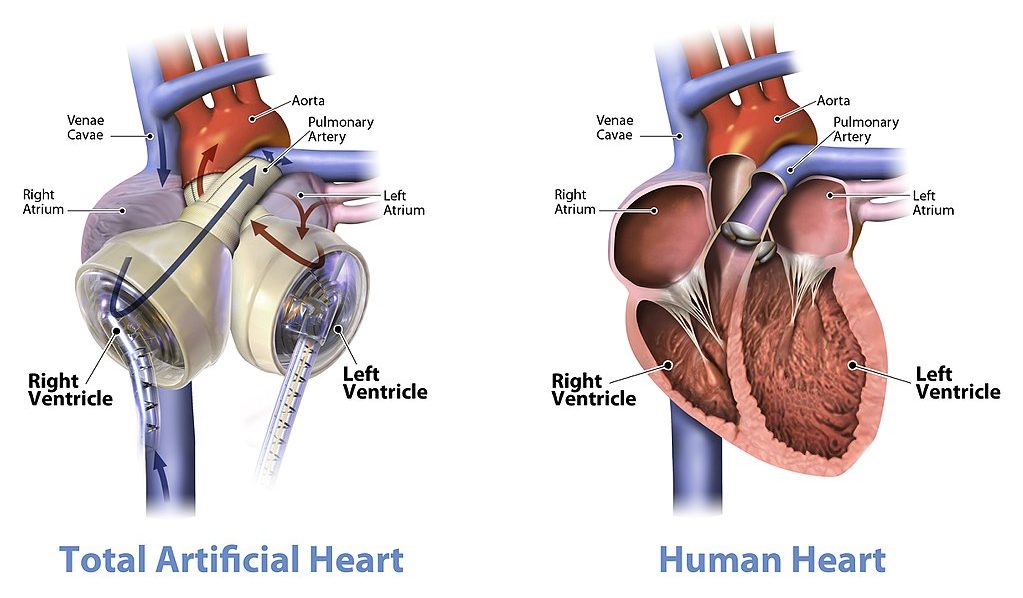

Feature: Human Biology in the News

When a patient’s heart is too diseased or damaged to sustain life, a heart transplant is likely to be the only long-term solution. The first successful heart transplant was undertaken in South Africa in 1967. There are over 2,200 Canadians walking around today because of life-saving heart transplant surgery. Approximately 180 heart transplant surgeries are performed each year, but there are still so many Canadians on the transplant list that some die while waiting for a heart. The problem is that far too few hearts are available for transplant — there is more demand (people waiting for a heart transplant) than supply (organ donors). Sometimes, recipient hopefuls will receive a device called a Total Artificial Heart (see Figure 14.3.10), which can buy them some time until a donor heart becomes available.

Watch the video below "Total artificial heart option..." from Stanford Health Care to see how it works:

https://youtu.be/1PtxaxcPnGc

Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage), Stanford Health Care, 2014.

14.3 Summary

- The heart is a muscular organ behind the sternum and slightly to the left of the center of the chest. Its function is to pump blood through the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system.

- The wall of the heart consists of three layers. The middle layer, the myocardium, is the thickest layer and consists mainly of cardiac muscle. The interior of the heart consists of four chambers, with an upper atrium and lower ventricle on each side of the heart. Blood enters the heart through the atria, which pump it to the ventricles. Then the ventricles pump blood out of the heart. Four valves in the heart keep blood flowing in the correct direction and prevent backflow.

- The coronary circulation consists of blood vessels that carry blood to and from the heart muscle cells, and is different from the general circulation of blood through the heart chambers. There are two coronary arteries that supply the two sides of the heart with oxygenated blood. Cardiac veins drain deoxygenated blood back into the heart.

- Deoxygenated blood flows into the right atrium through veins from the upper and lower body (superior and inferior vena cava, respectively), and oxygenated blood flows into the left atrium through four pulmonary veins from the lungs. Each atrium pumps the blood to the ventricle below it. From the right ventricle, deoxygenated blood is pumped to the lungs through the two pulmonary arteries. From the left ventricle, oxygenated blood is pumped to the rest of the body through the aorta.

- The cardiac cycle refers to a single complete heartbeat. It includes diastole — when the atria contract — and systole, when the ventricles contract.

- The normal, rhythmic beating of the heart is called sinus rhythm. It is established by the heart’s pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node. Electrical signals from the pacemaker cells travel to the atria, and cause them to contract. Then, the signals travel to the atrioventricular node and from there to the ventricles, causing them to contract. Electrical stimulation from the autonomic nervous system and hormones from the endocrine system can also influence heartbeat.

14.3 Review Questions

- What is the heart, where is located, and what is its function?

-

- Describe the coronary circulation.

- Summarize how blood flows into, through, and out of the heart.

- Explain what controls the beating of the heart.

- What are the two types of cardiac muscle cells in the myocardium? What are the differences between these two types of cells?

- Explain why the blood from the cardiac veins empties into the right atrium of the heart. Focus on function (rather than anatomy) in your answer.

14.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM

Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face, TED, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M

Watch a Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI

A Change of Heart: My Transplant Experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse, TEDx Talks, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk

Heart Transplant Recipient Meets Donor Family For The First Time, WMC Health, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 14.3.1

- Female clinician dressed in scrubs using a stethoscope by Amanda Mills, USCDCP, on Pixnio is used under a CC0 public domain certification license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/publicdomain/).

- Human heart beating loud and strong (audio) by Daniel Simion on Soundbible.com is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.2

Blausen_0470_HeartWall by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.3

Diagram_of_the_human_heart_(cropped).svg by Wapcaplet on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 14.3.4

Heart_Valves by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.3.5

CG_Heart Valve Animation by DrJanaOfficial on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 14.3.6

Heart_tee_four_chamber_view by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator from Yale University School of Medicine, on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) license.

Figure 14.3.7

Circulation of blood through the heart by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license. [Original image in the bottom right is by Wapcaplet / CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Figure 14.3.8

Human_healthy_pumping_heart_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Common is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 14.3.9

Cardiac_Conduction_System by Cypressvine on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 19.12 Heart valves with the atria and major vessels removed [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 19.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/19-1-heart-anatomy#fig-ch20_01_04

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. (n.d.). https://www.heartandstroke.ca/

Sliwa, K., Zilla, P. (2017, December 7). 50th anniversary of the first human heart transplant—How is it seen today? European Heart Journal, 38(46):3402–3404. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx695

Stanford Health Care. (2014, December 3). Total artificial heart option at Stanford (Includes surgical graphic footage). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PtxaxcPnGc&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2012, March 21). Noel Bairey Merz: The single biggest health threat women face. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bnzVjOJ6NM&feature=youtu.be

TEDx Talks. (2018, April 18). A change of heart: My transplant experience | Thomas Volk | TEDxUWLaCrosse. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zU6mmix04PI&feature=youtu.be

UMagazine. (2015, Fall). The cutting edge: Patient first to bridge from experimental total artificial heart to transplant. UCLA Health. https://www.uclahealth.org/u-magazine/patient-first-to-bridge-from-experimental-total-artificial-heart-to-transplant

UnityPoint Health - Cedar Rapids. (2018, February 7). Watch a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) Procedure at St. Luke's in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJm7zBcN6-M&feature=youtu.be

WMC Health. (2018, September 13). Heart transplant recipient meets donor family for the first time. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=biGuwQhuAsk&feature=youtu.be

A testable proposed explanation for a phenomenon.

A biological process which converts sugars such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose into cellular energy, producing ethanol and carbon dioxide as by-products.

Image shows to small children in a backyard wading pool. One adult is standing by the pool resting their foot on the edge and another adult is sitting nearby in a lawn chair.

Image shows a diagram labeling the major arteries of the body. Some of these include the carotid artery which provides blood to the neck and head, the brachiocephalic artery which supplies blood to the arms and head, the renal artery supplying blood to the kidneys, the mesenteric arteries supplying blood to the intestines, the femoral arteries supplying blood to the legs.

Image shows a female clinician dressed in scrubs listening to the heartbeat of a patient.

a hormonal disorder common among women of reproductive age. Women with PCOS may have infrequent or prolonged menstrual periods or excess male hormone (androgen) levels. The ovaries may develop numerous small collections of fluid (follicles) and fail to regularly release eggs.

Image shows a diagram comparing a healthy nephron and its blood supply and one with diabetic nephropathy. The diseased one has blood vessels that look deformed and fragile.

a hormonal disorder common among women of reproductive age. Women with PCOS may have infrequent or prolonged menstrual periods or excess male hormone (androgen) levels. The ovaries may develop numerous small collections of fluid (follicles) and fail to regularly release eggs.

Rocky Mountain Oysters

First, they are peeled and pounded flat. Then, they are coated in flour, seasoned with salt and pepper, and deep fried. What are they? They are often called Rocky Mountain oysters, but they don’t come from the sea. They may also be known as Montana tendergroin, cowboy caviar, or swinging beef — all names that hint at their origins. Here’s another hint: they are harvested only from male animals, such as bulls or sheep. What are they? In a word: testes.

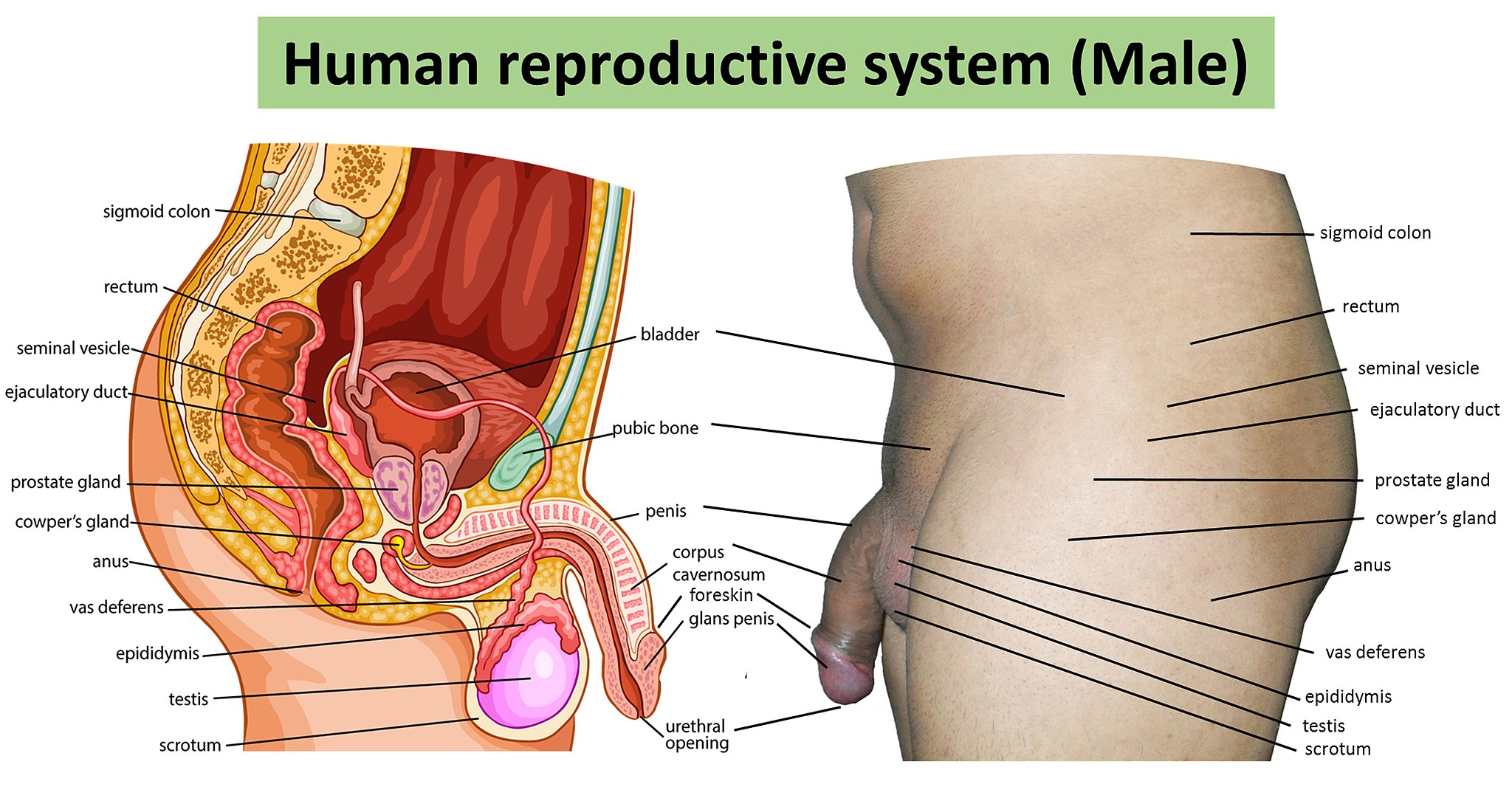

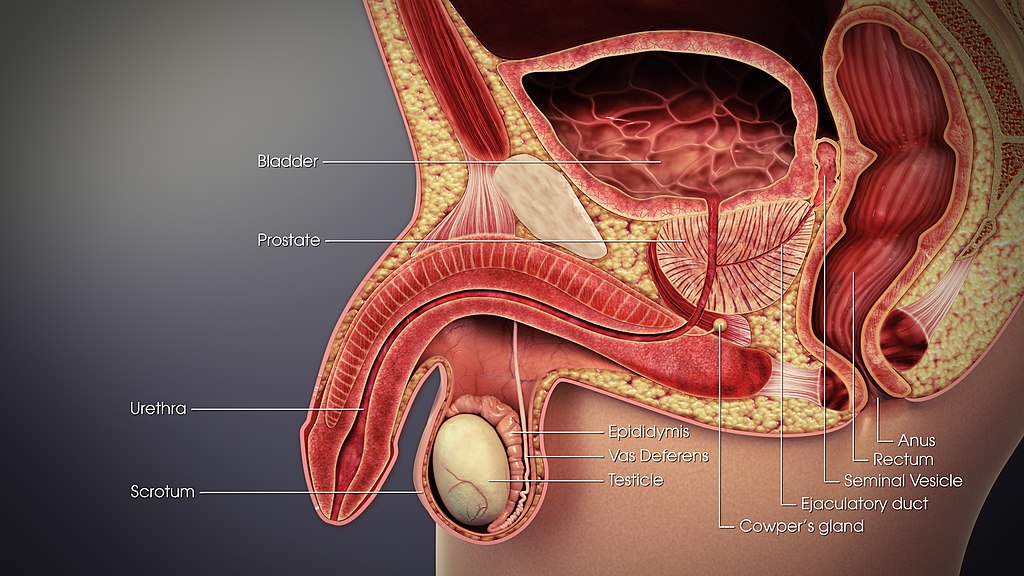

Testes and Scrotum

The two testes (singular, testis) are sperm- and testosterone-producing gonads in male mammals, including male humans. These and other organs of the human male reproductive system are shown in Figure 18.3.2. The testes are contained within the scrotum, a pouch made of skin and smooth muscle that hangs down behind the penis.

Testes Structure

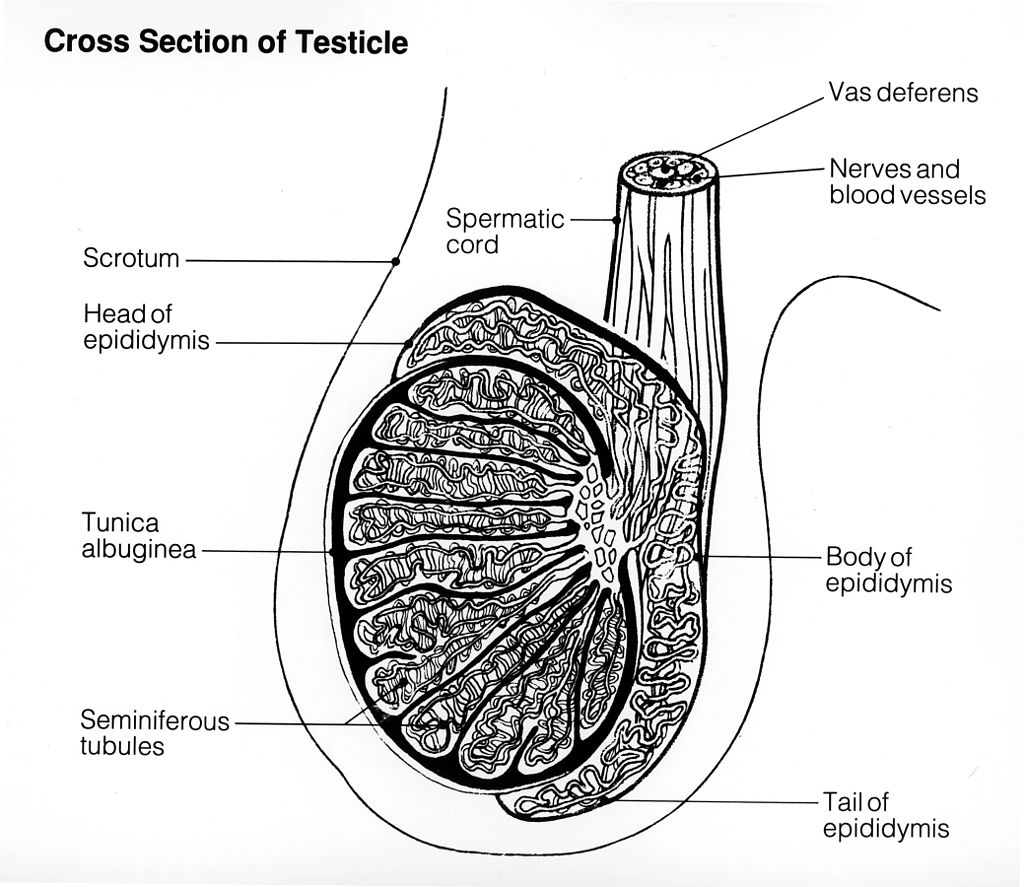

The testes are filled with hundreds of tiny tubes, called seminiferous tubules, which are the functional units of the testes. As shown in the longitudinal-section drawing of a testis in Figure 18.3.3, the seminiferous tubules are coiled and tightly packed within divisions of the testis called lobules. Lobules are separated from one another by internal walls (or septa).

Tunica

The multi-layered covering of each testis, called the tunica, protects the organ, ensures its blood supply, and separates the testis into lobules. There are three layers of the tunica: the tunica vasculosa, tunica albuginea, and tunica vaginalis. The latter two layers are labeled in the drawing above (Figure 18.3.3).

- The tunica vasculosa is the innermost layer of the tunica. It consists of connective tissue and contains arteries and veins that carry blood to and from the testis.

- The tunica albuginea is the middle layer of the tunica. It is a dense layer of fibrous tissue that encases the testis. It also extends into the testis, creating the septa between lobules.

- The tunica vaginalis is the outmost layer of the tunica. It actually consists of two layers of tissue separated by a thin fluid layer. The fluid reduces friction between the testes and the scrotum.

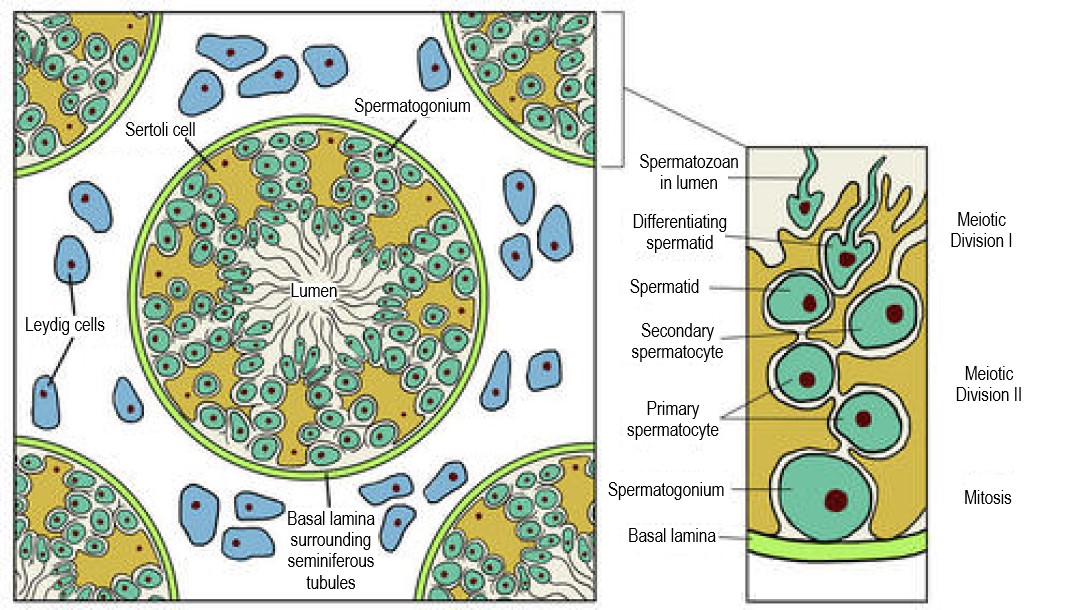

Seminiferous Tubules

One or more seminiferous tubules are tightly coiled within each of the hundreds of lobules in the testis. A single testis normally contains a total of about 30 metres of these tightly packed tubules! As shown in the cross-sectional drawing of a seminiferous tubule in Figure 18.3.4, the tubule contains sperm in several different stages of development (spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa). The seminiferous tubule is also lined with epithelial cells called Sertoli cells. These cells release a hormone (inhibin) that helps regulate sperm production. Adjacent Sertoli cells are closely spaced so large molecules cannot pass from the blood into the tubules. This prevents the male’s immune system from reacting against the developing sperm, which may be antigenically different from his own self tissues. Cells of another type, called Leydig cells, are found between the seminiferous tubules. Leydig cells produce and secrete testosterone.

Other Scrotal Structures

Besides the two testes, the scrotum also contains a pair of organs called epididymes (singular, epididymis) and part of each of the paired vas deferens (or ducti deferens). Both structures play important functions in the production or transport of sperm.

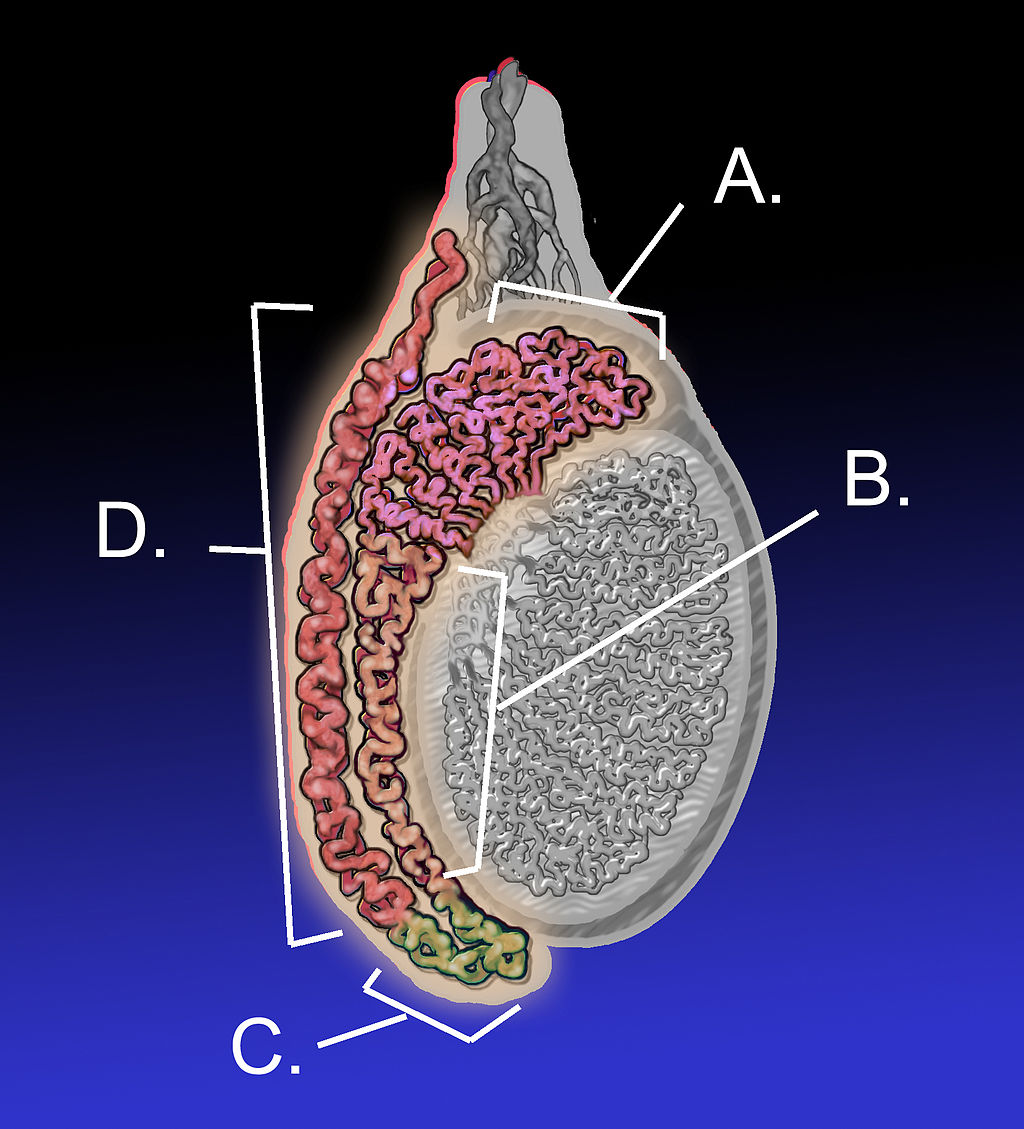

Epididymis

The seminiferous tubules within each testis join together to form ducts (called efferent ducts) that transport immature sperm to the epididymis associated with that testis. Each epididymis (plural, epididymes) consists of a tightly coiled tubule with a total length of about 6 metres. As shown in Figure 18.3.5, the epididymis is generally divided into three parts: the head (which rests on top of the testis), the body (which drapes down the side of the testis), and the tail (which joins with the vas deferens near the bottom of the testis). The functions of the two epididymes are to mature sperm, and then to store that mature sperm until they leave the body during an ejaculation, when they pass the sperm on to the vas deferens.

Vas Deferens

The vas deferens, also known as sperm ducts, are a pair of thin tubes, each about 30 cm (almost 12 in) long, which begin at the epididymes in the scrotum, and continue up into the pelvic cavity. They are composed of ciliated epithelium and smooth muscle. These structures help the vas deferens fulfill their function of transporting sperm from the epididymes to the ejaculatory ducts, which are accessory structures of the male reproductive system.

Accessory Structures

In addition to the structures within the scrotum, the male reproductive system includes several internal accessory structures that are shown in the detailed drawing in Figure 18.3.6. They include the ejaculatory ducts, seminal vesicles, and the prostate and bulbourethral (Cowper’s) glands.

Seminal Vesicles

The seminal vesicles are a pair of exocrine glands that each consist of a single tube, which is folded and coiled upon itself. Each vesicle is about 5 cm (almost 2 in) long and has an excretory duct that merges with the vas deferens to form one of the two ejaculatory ducts. Fluid secreted by the seminal vesicles into the ducts makes up about 70% of the total volume of semen, which is the sperm-containing fluid that leaves the penis during an ejaculation. The fluid from the seminal vesicles is alkaline, so it gives semen a basic pH that helps prolong the lifespan of sperm after it enters the acidic secretions inside the female vagina. Fluid from the seminal vesicles also contains proteins, fructose (a simple sugar), and other substances that help nourish sperm.

Ejaculatory Ducts

The ejaculatory ducts form where the vas deferens join with the ducts of the seminal vesicles in the prostate gland. They connect the vas deferens with the urethra. The ejaculatory ducts carry sperm from the vas deferens, as well as secretions from the seminal vesicles and prostate gland that together form semen. The substances secreted into semen by the glands as it passes through the ejaculatory ducts control its pH and provide nutrients to sperm, among other functions. The fluid itself provides sperm with a medium in which to “swim.”

Prostate Gland

The prostate gland is located just below the seminal vesicles. It is a walnut-sized organ that surrounds the urethra and its junction with the two ejaculatory ducts. The function of the prostate gland is to secrete a slightly alkaline fluid that constitutes close to 30% of the total volume of semen. Prostate fluid contains small quantities of proteins, such as enzymes. In addition, it has a very high concentration of zinc, which is an important nutrient for maintaining sperm quality and motility.

Bulbourethral Glands

Also called Cowper’s glands, the two bulbourethral glands are each about the size of a pea and located just below the prostate gland. The bulbourethral glands secrete a clear, alkaline fluid that is rich in proteins. Each of the glands has a short duct that carries the secretions into the urethra, where they make up a tiny percentage of the total volume of semen. The function of the bulbourethral secretions is to help lubricate the urethra and neutralize any urine (which is acidic) that may remain in the urethra.

Figure 18.3.7 Male reproductive system.

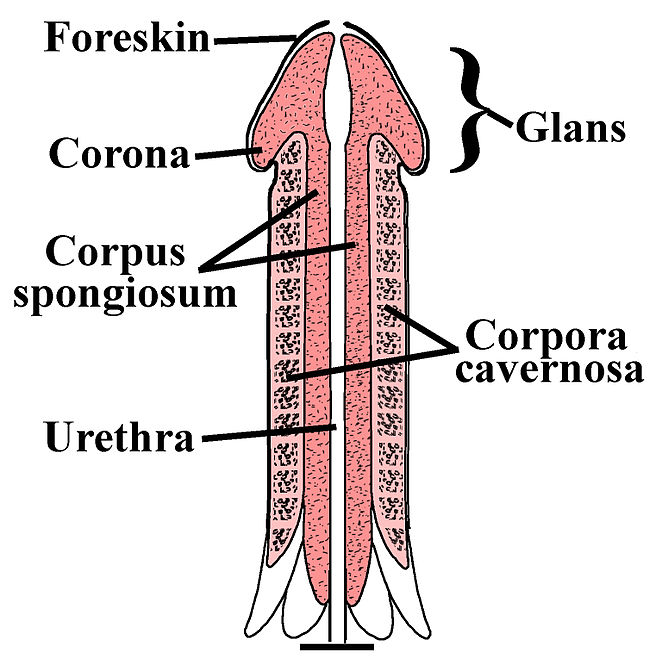

Penis

The penis is the external male organ that has the reproductive function of delivering sperm to the female reproductive tract. This function is called intromission. The penis also serves as the organ that excretes urine.

Structure of the Penis

The structure of the penis and its location relative to other reproductive organs are shown in Figure 18.3.8. The part of the penis that is located inside the body and out of sight is called the root of the penis. The shaft of the penis is the part of the penis that is outside the body. The enlarged, bulbous end of the shaft is called the glans penis.

Urethra

The urethra passes through the penis to carry urine from the bladder — or semen from the ejaculatory ducts — through the penis and out of the body. After leaving the urinary bladder, the urethra passes through the prostate gland, where the urethra is joined by the ejaculatory ducts. From there, the urethra passes through the penis to its external opening at the tip of the glans penis. Called the external urethral orifice, this opening provides a way for urine or semen to leave the body.

Tissues of the Penis

The penis is covered with skin (epithelium) that is unattached and free to move over the body of the penis. In an uncircumcised male, the glans penis is also mainly covered by epithelium, which (in this location) is called the foreskin, and below which is a layer of mucous membrane. The foreskin is attached to the penis at an area on the underside of the penis called the frenulum.

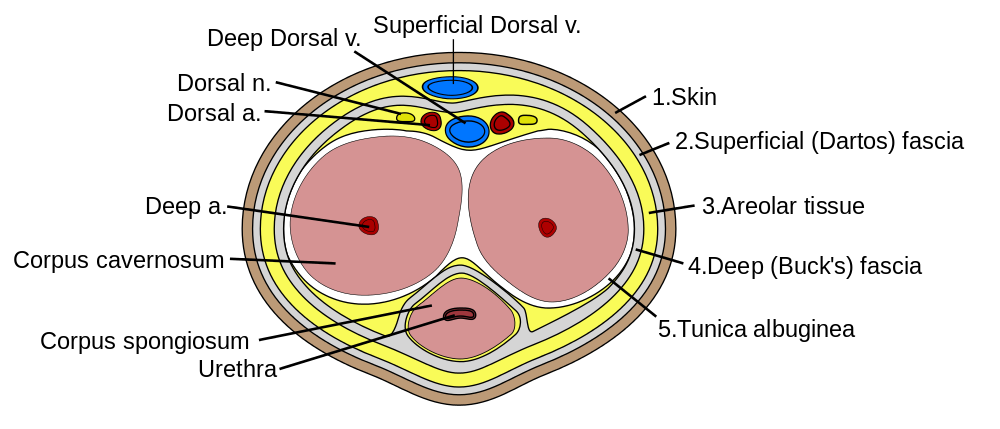

As shown in the Figure 18.3.9, the interior of the penis consists of three columns of spongy tissue that can fill with blood and swell in size, allowing the penis to become erect. This spongy tissue is called corpus cavernosum (plural, corpora cavernosa). Two columns of this tissue run side by side along the top of the shaft, and one column runs along the bottom of the shaft. The urethra runs through this bottom column of spongy tissue, which is sometimes called corpus spongiosum. The glans penis also consists mostly of spongy erectile tissue. Veins and arteries run along the top of the penis, allowing blood circulation through the spongy tissues.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

Lung, heart, kidney, and other organ transplants have become relatively commonplace, so when they occur, they are unlikely to make the news. However, when the nation’s first penis transplant took place, it was considered very newsworthy.

In 2016, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston announced that a team of its surgeons had performed the first penis transplant in the United States. The patient who received the donated penis was a 64-year-old cancer patient. During the 15-hour procedure, the intricate network of nerves and blood vessels of the donor penis were connected with those of the penis recipient. The surgery went well, but doctors reported it would be a few weeks until they would know if normal urination would be possible, and even longer before they would know if sexual functioning would be possible. At the time that news of the surgery was reported in the media, the patient had not shown any signs of rejecting the donated organ. Within 6 months, the patient was able to urinate properly and was beginning to regain sexual function. The surgeons also reported they were hopeful that such transplants would become relatively common, and that patient populations would expand to include wounded warriors and transgender males seeking to transition.

The 2016 Massachusetts operation was not the first penis transplant ever undertaken. The world’s first successful penis transplant was actually performed in 2014 in Cape Town, South Africa. A young man who had lost his penis from complications of a botched circumcision at age 18 was given a donor penis three years later. That surgery lasted nine hours and was highly successful. The young man made a full recovery and regained both urinary and sexual functions in the transplanted organ.

In 2005, a man in China also received a donated penis in a technically successful operation. However, the patient asked doctors to reverse the procedure just two weeks later, because of psychological problems associated with the transplanted organ for both himself and his wife.

18.3 Summary

- The two testes are sperm- and testosterone-producing male gonads. They are contained within the scrotum, a pouch that hangs down behind the penis. The testes are filled with hundreds of tiny, tightly coiled seminiferous tubules, where sperm are produced. The tubules contain sperm in different stages of development and also Sertoli cells, which secrete substances needed for sperm production. Between the tubules are Leydig cells, which secrete testosterone.

- Also contained within the scrotum are the two epididymes. Each epididymis is a tightly coiled tubule where sperm mature and are stored until they leave the body during an ejaculation.

- The two vas deferens are long, thin tubes that run from the scrotum up into the pelvic cavity. During ejaculation, each vas deferens carries sperm from one of the two epididymes to one of the pair of ejaculatory ducts.

- The two seminal vesicles are glands within the pelvis that secrete fluid through ducts into the junction of each vas deferens and ejaculatory duct. This alkaline fluid makes up about 70% of semen, the sperm-containing fluid that leaves the penis during ejaculation. Semen contains alkaline substances and nutrients that sperm need to survive and “swim” in the female reproductive tract.

- The paired ejaculatory ducts form where the vas deferens joins with the ducts of the seminal vesicles in the prostate gland. They connect the vas deferens with the urethra. The ejaculatory ducts carry sperm from the vas deferens, as well as secretions from the seminal vesicles and prostate gland that together form semen.

- The prostate gland is located just below the seminal vesicles, and it surrounds the urethra and its junction with the ejaculatory ducts. The prostate secretes an alkaline fluid that makes close to 30% of semen. Prostate fluid contains a high concentration of zinc, which sperm need to be healthy and motile.

- The paired bulbourethral glands are located just below the prostate gland. They secrete a tiny amount of fluid into semen. The secretions help lubricate the urethra and neutralize any acidic urine it may contain.

- The penis is the external male organ that has the reproductive function of intromission, which is delivering sperm to the female reproductive tract. The penis also serves as the organ that excretes urine. The urethra passes through the penis and carries urine or semen out of the body. Internally, the penis consists largely of columns of spongy tissue that can fill with blood and make the penis stiff and erect. This is necessary for sexual intercourse so intromission can occur.

18.3 Review Questions

-

-

- Describe the structure of a testis.

- Which parts of the male reproductive system are connected by the ejaculatory ducts? What fluids enter and leave the ejaculatory ducts?

- A vasectomy is a form of birth control for men that is performed by surgically cutting or blocking the vas deferens so that sperm cannot be ejaculated out of the body. Do you think men who have a vasectomy emit semen when they ejaculate? Why or why not?

-

18.3 Explore More

https://youtu.be/k60M1h-DKVY

Human Physiology - Functional Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System (Updated), Janux, 2015.

https://youtu.be/D1et5NgT6bQ

The Science of 'Morning Wood', AsapSCIENCE, 2012.

https://youtu.be/Ot7CYjm9B7U

I Had One Of The World's First Penis Transplants - Thomas Manning | This Morning, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 18.3.1

Lamb_fries by Paul Lowry on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 18.3.2

Human_reproductive_system_(Male) by Baresh25 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 18.3.3

Testicle by Unknown Illustrator from National Cancer Institute, of the National Institutes of Health, Visuals Online, ID 1769 is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain).

Figure 18.3.4

Testis-cross-section by Laura Guerin from CK-12 Foundation is used under a

CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 18.3.5

Epididymis-KDS by KDS444 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 18.3.6

3D_Medical_Animation_Vas_Deferens by https://www.scientificanimations.com/wiki-images (image 26 of 191) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 18.3.7

Male anatomy blank [adapted] by Tsaitgaist on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license. (Original: Male anatomy.png)

Figure 18.3.8

Penile-Clitoral_Structure by Esseh on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 18.3.9

Penis_cross_section.svg by Mcstrother on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

References

AsapSCIENCE, (2012, November 14). The science of 'morning wood'. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1et5NgT6bQ&feature=youtu.be

Associated Press. (2016, May 17). Man receives new penis in 15-hour operation, the first transplant of its kind in U.S. history [online article]. Canada.com. http://www.canada.com/health/receives+penis+hour+operation+first+transplant+kind+history/11922832/story.html

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2012). Figure 3 Cross section of a testis and seminiferous tubules [digital image]. In CK-12 Biology (Section 25.1) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-biology/section/25.1/

Gallagher, J. (2015, March 13). South Africans perform first 'successful' penis transplant (online article). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-31876219

Grady, D. (2016, May 16). Cancer survivor receives first penis transplant in the United States [online article]. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/17/health/thomas-manning-first-penis-transplant-in-us.html

Janux. (2015, August 16). Human physiology - Functional anatomy of the male reproductive system (Updated). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k60M1h-DKVY&feature=youtu.be

This Morning. (2016, June 15). I had one of the world's first penis transplants - Thomas Manning | This Morning. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ot7CYjm9B7U&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a photograph of an Amish man. His hairstyle and beard with no mustache is evidence that he is married.

As per caption

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Giving the Gift of Life

Did you ever donate blood? If you did, then you probably know that your blood type is an important factor in blood transfusions. People vary in the type of blood they inherit, and this determines which type(s) of blood they can safely receive in a transfusion. Do you know your blood type?

What Are Blood Types?

Blood is composed of cells suspended in a liquid called plasma. There are three types of cells in blood: red blood cells, which carry oxygen; white blood cells, which fight infections and other threats; and platelets, which are cell fragments that help blood clot. Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of certain molecules, called antigens, on the surface of red blood cells. These molecules may help maintain the integrity of the cell membrane, act as receptors, or have other biological functions. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens. Human blood group systems include the well-known ABO and Rhesus (Rh) systems, as well as at least 33 others that are less well known.

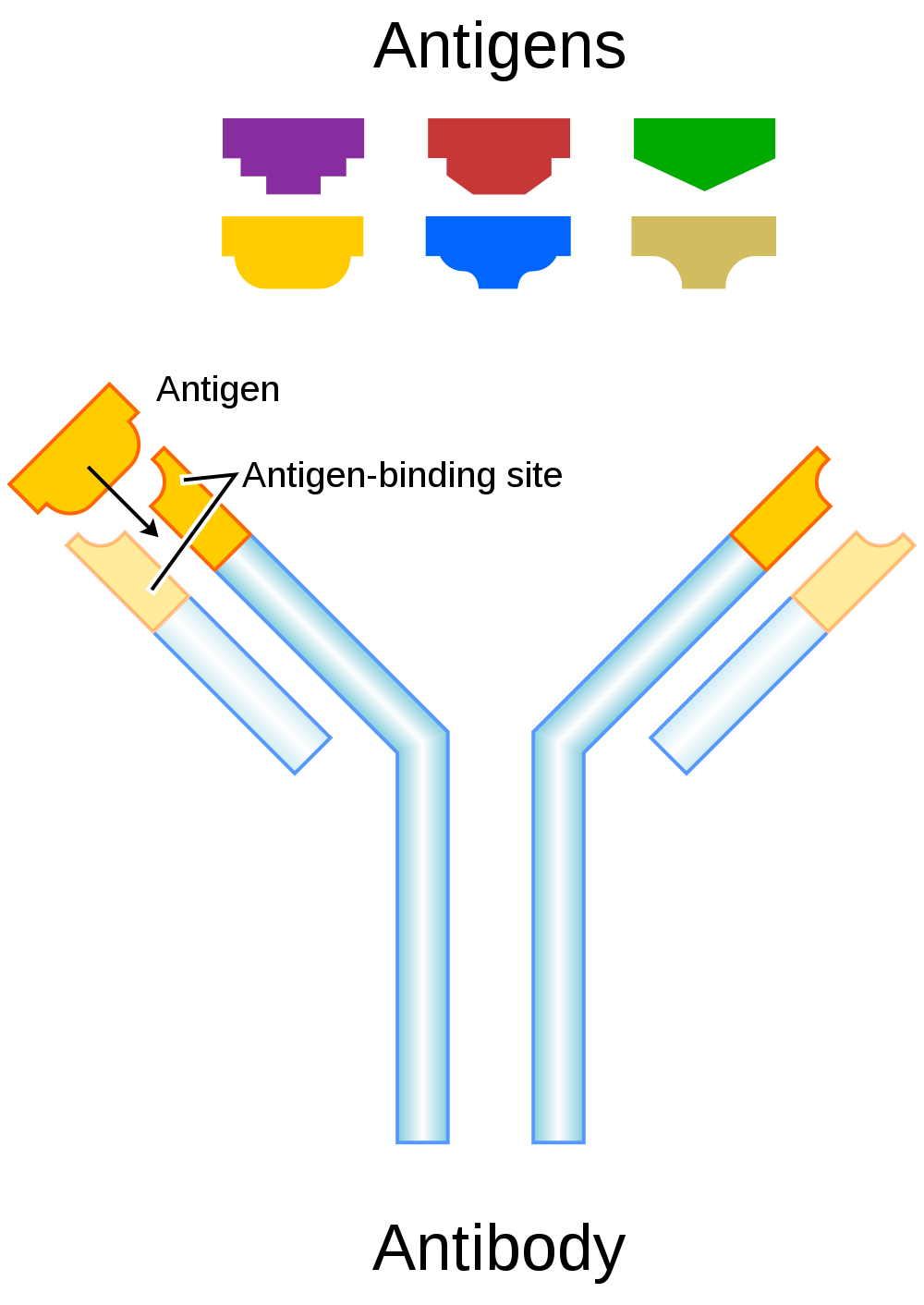

Antigens and Antibodies

Antigens — such as those on the red blood cells — are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self (produced by your own body) or non-self (not produced by your own body). Blood group antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins (proteins attached to chains of sugars), or glycolipids (lipids attached to chains of sugars), depending on the particular blood group system. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens. Antibodies are large, Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system that recognize and bind to non-self antigens. The analogy of a lock and key is often used to represent how an antibody and antigen fit together, as shown in the illustration below (Figure 6.5.2). When antibodies bind to antigens, it marks them for destruction by other immune system cells. Non-self antigens may enter your body on pathogens (such as bacteria or viruses), on foods, or on red blood cells in a blood transfusion from someone with a different blood type than your own. The last way is virtually impossible nowadays because of effective blood typing and screening protocols.

Genetics of Blood Type

An individual’s blood type depends on which alleles for a blood group system were inherited from their parents. Generally, blood type is controlled by alleles for a single gene, or for two or more very closely linked genes. Closely linked genes are almost always inherited together, because there is little or no recombination between them. Like other genetic traits, a person’s blood type is generally fixed for life, but there are rare instances in which blood type can change. This could happen, for example, if an individual receives a bone marrow transplant to treat a disease, such as leukemia. If the bone marrow comes from a donor who has a different blood type, the patient’s blood type may eventually convert to the donor’s blood type, because red blood cells are produced in bone marrow.

ABO Blood Group System

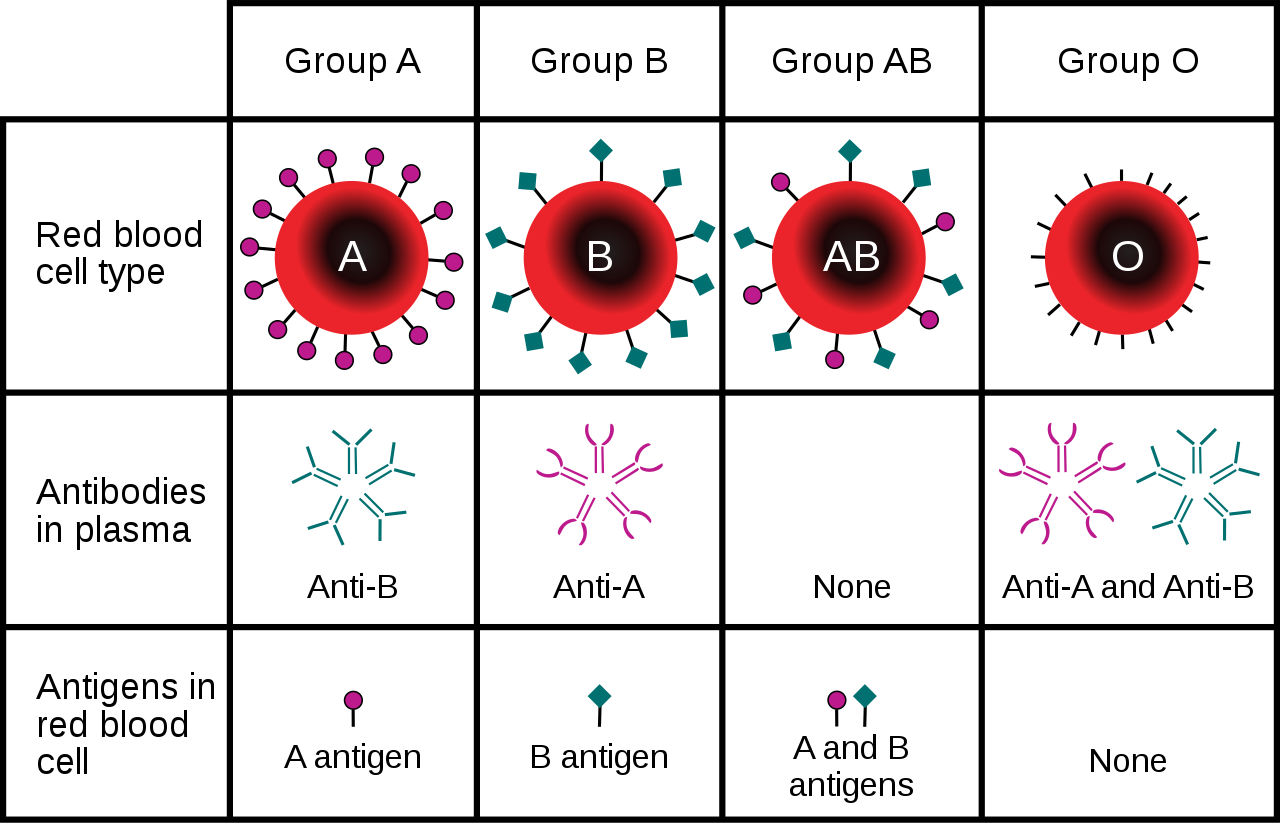

The ABO blood group system is the best known human blood group system. Antigens in this system are glycoproteins. These antigens are shown in the list below. There are four common blood types for the ABO system:

- Type A, in which only the A antigen is present.

- Type B, in which only the B antigen is present.

- Type AB, in which both the A and B antigens are present.

- Type O, in which neither the A nor the B antigen is present.

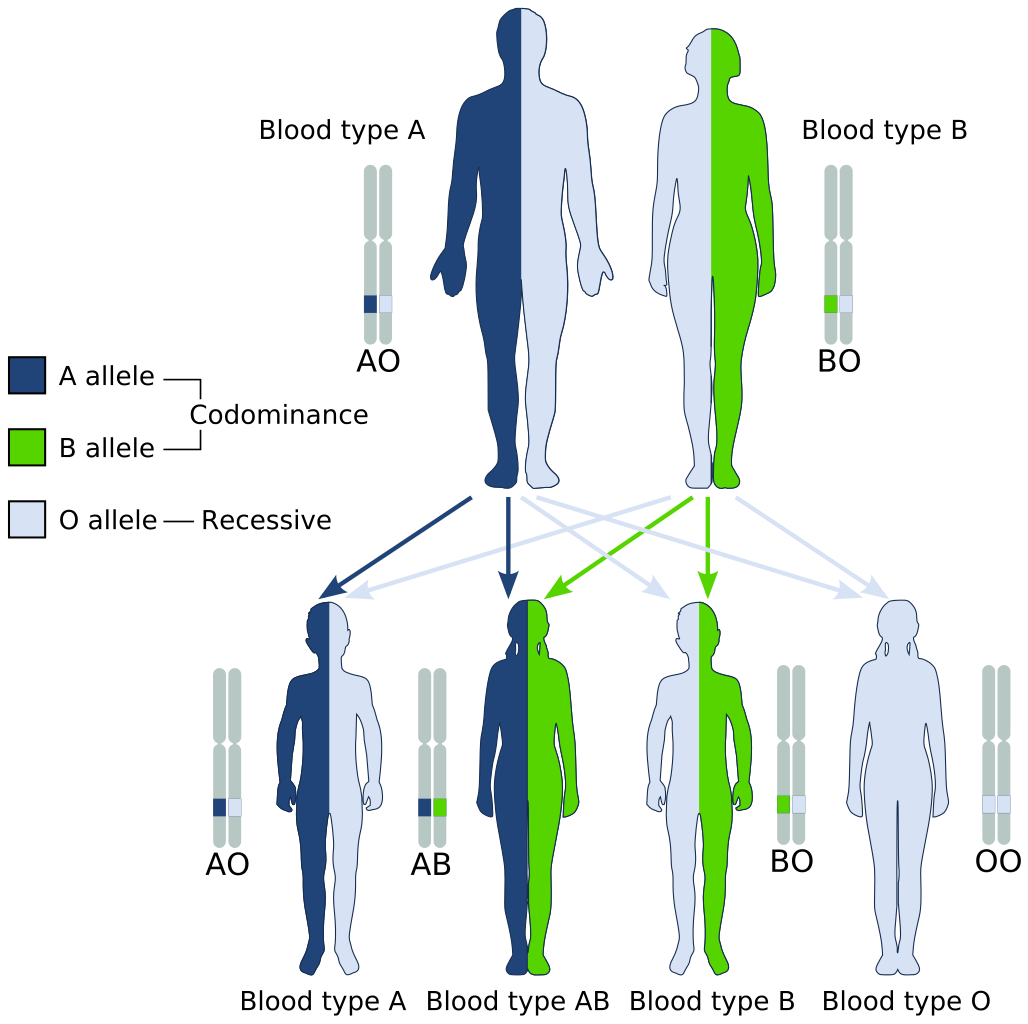

Genetics of the ABO System

The ABO blood group system is controlled by a single gene on chromosome 9. There are three common alleles for the gene, often represented by the letters A , B , and O. With three alleles, there are six possible genotypes for ABO blood group. Alleles A and B, however, are both dominant to allele O and codominant to each other. This results in just four possible phenotypes (blood types) for the ABO system. These genotypes and phenotypes are shown in Table 6.5.1.

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes

| ABO Blood Group System | |

| Genotype | Phenotype (Blood Type, or Group) |

| AA | A |

| AO | A |

| BB | B |

| BO | B |

| OO | O |

| AB | AB |

The diagram below (Figure 6.5.3) shows an example of how ABO blood type is inherited. In this particular example, the father has blood type A (genotype AO) and the mother has blood type B (genotype BO). This mating type can produce children with each of the four possible ABO phenotypes, although in any given family, not all phenotypes may be present in the children.

Medical Significance of ABO Blood Type

The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. If red blood cells containing a particular ABO antigen are transfused into a person who lacks that antigen, the person’s immune system will recognize the antigen on the red blood cells as non-self. Antibodies specific to that antigen will attack the red blood cells, causing them to agglutinate (or clump) and break apart. If a unit of incompatible blood were to be accidentally transfused into a patient, a severe reaction (called acute hemolytic transfusion reaction) is likely to occur, in which many red blood cells are destroyed. This may result in kidney failure, shock, and even death. Fortunately, such medical accidents virtually never occur today.

These antibodies are often spontaneously produced in the first years of life, after exposure to common microorganisms in the environment that have antigens similar to blood antigens. Specifically, a person with type A blood will produce anti-B antibodies, while a person with type B blood will produce anti-A antibodies. A person with type AB blood does not produce either antibody, while a person with type O blood produces both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Once the antibodies have been produced, they circulate in the plasma. The relationship between ABO red blood cell antigens and plasma antibodies is shown in Figure 6.5.4.

The antibodies that circulate in the plasma are for different antigens than those on red blood cells, which are recognized as self antigens.

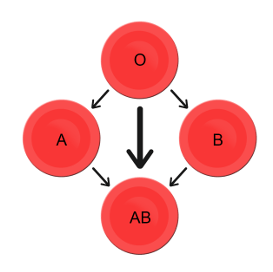

Which blood types are compatible and which are not? Type O blood contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, so people with type O blood can only receive type O blood. However, they can donate blood to people of any ABO blood type, which is why individuals with type O blood are called universal donors. Type AB blood contains neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies, so people with type AB blood can receive blood from people of any ABO blood type. That’s why individuals with type AB blood are called universal recipients. They can donate blood, however, only to people who also have type AB blood. These and other relationships between blood types of donors and recipients are summarized in the simple diagram to the right.

Geographic Distribution of ABO Blood Groups

The frequencies of blood groups for the ABO system vary around the world. You can see how the A and B alleles and the blood group O are distributed geographically on the maps in Figure 6.5.6.

- Worldwide, B is the rarest ABO allele, so type B blood is the least common ABO blood type. Only about 16 per cent of all people have the B allele. Its highest frequency is in Asia. Its lowest frequency is among the indigenous people of Australia and the Americas.

- The A allele is somewhat more common around the world than the B allele, so type A blood is also more common than type B blood. The highest frequencies of the A allele are in Australian Aborigines, the Lapps (Sami) of Northern Scandinavia, and Blackfoot Native Americans in North America. The allele is nearly absent among Native Americans in Central and South America.

- The O allele is the most common ABO allele around the world, and type O blood is the most common ABO blood type. Almost two-thirds of people have at least one copy of the O allele. It is especially common in Native Americans in Central and South America, where it reaches frequencies close to 100 per cent. It also has relatively high frequencies in Australian Aborigines and Western Europeans. Its frequencies are lowest in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Figure 6.5.6 Maps of populations that have the A, B and O alleles.

Evolution of the ABO Blood Group System

The geographic distribution of ABO blood type alleles provides indirect evidence for the evolutionary history of these alleles. Evolutionary biologists hypothesize that the allele for blood type A evolved first, followed by the allele for blood type O, and then by the allele for blood type B. This chronology accounts for the percentages of people worldwide with each blood group, and is also consistent with known patterns of early population movements.

The evolutionary forces of founder effect and genetic drift have no doubt played a significant role in the current distribution of ABO blood types worldwide. Geographic variation in ABO blood groups is also likely to be influenced by natural selection, because different blood types are thought to vary in their susceptibility to certain diseases. For example:

- People with type O blood may be more susceptible to cholera and plague. They are also more likely to develop gastrointestinal ulcers.

- People with type A blood may be more susceptible to smallpox and more likely to develop certain cancers.

- People with types A, B, and AB blood appear to be less likely to form blood clots that can cause strokes. However, early in our history, the ability of blood to form clots — which appears greater in people with type O blood — may have been a survival advantage.

- Perhaps the greatest natural selective force associated with ABO blood types is malaria. There is considerable evidence to suggest that people with type O blood are somewhat resistant to malaria, giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

Rhesus Blood Group System

Another well-known blood group system is the Rhesus (Rh) blood group system. The Rhesus system has dozens of different antigens, but only five main antigens (called D, C, c, E, and e). The major Rhesus antigen is the D antigen. People with the D antigen are called Rh positive (Rh+), and people who lack the D antigen are called Rh negative (Rh-). Rhesus antigens are thought to play a role in transporting ions across cell membranes by acting as channel proteins.

The Rhesus blood group system is controlled by two linked genes on chromosome 1. One gene, called RHD, produces a single antigen, antigen D. The other gene, called RHCE, produces the other four relatively common Rhesus antigens (C, c, E, and e), depending on which alleles for this gene are inherited.

Rhesus Blood Group and Transfusions

After the ABO system, the Rhesus system is the second most important blood group system in blood transfusions. The D antigen is the one most likely to provoke an immune response in people who lack the antigen. People who have the D antigen (Rh+) can be safely transfused with either Rh+ or Rh- blood, whereas people who lack the D antigen (Rh-) can be safely transfused only with Rh- blood.

Unlike anti-A and anti-B antibodies to ABO antigens, anti-D antibodies for the Rhesus system are not usually produced by sensitization to environmental substances. People who lack the D antigen (Rh-), however, may produce anti-D antibodies if exposed to Rh+ blood. This may happen accidentally in a blood transfusion, although this is extremely unlikely today. It may also happen during pregnancy with an Rh+ fetus if some of the fetal blood cells pass into the mother’s blood circulation.

Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

If a woman who is Rh- is carrying an Rh+ fetus, the fetus may be at risk. This is especially likely if the mother has formed anti-D antibodies during a prior pregnancy because of a mixing of maternal and fetal blood during childbirth. Unlike antibodies against ABO antigens, antibodies against the Rhesus D antigen can cross the placenta and enter the blood of the fetus. This may cause hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN), also called erythroblastosis fetalis, an illness in which fetal red blood cells are destroyed by maternal antibodies, causing anemia. This illness may range from mild to severe. If it is severe, it may cause brain damage and is sometimes fatal for the fetus or newborn. Fortunately, HDN can be prevented by preventing the formation of anti-D antibodies in the Rh- mother. This is achieved by injecting the mother with a medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.

Geographic Distribution of Rhesus Blood Types

The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system, as there is with the ABO system. The aboriginal inhabitants of the Americas and Australia originally had very close to 100 per cent Rh+ blood. The frequency of the Rh+ blood type is also very high in African populations, at about 97 to 99 per cent. In East Asia, the frequency of Rh+ is slightly lower, at about 93 to 99 per cent. Europeans have the lowest frequency of the Rh+ blood type at about 83 to 85 per cent.

What explains the population variation in Rhesus blood types? Prior to the advent of modern medicine, Rh+ positive children conceived by Rh- women were at risk of fetal or newborn death or impairment from HDN. This was an enigma, because presumably, natural selection would work to remove the rarer phenotype (Rh-) from populations. However, the frequency of this phenotype is relatively high in many populations.

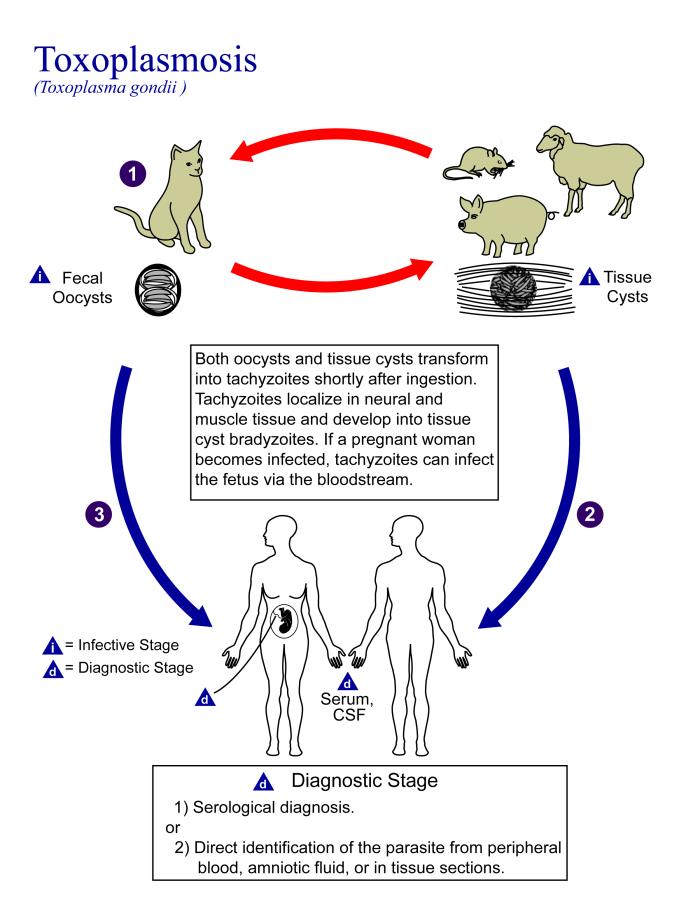

Recent studies have found evidence that natural selection may actually favor heterozygotes for the Rhesus D antigen. The selective agent in this case is thought to be toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, which is very common worldwide. You can see a life cycle diagram of the parasite in Figure 6.5.7. Infection by this parasite often causes no symptoms at all, or it may cause flu-like symptoms for a few days or weeks. Exposure to the parasite has been linked, however, to increased risk of mental disorders (such as schizophrenia), neurological disorders (such as Alzheimer’s), and other neurological problems, including delayed reaction times. One study found that people who tested positive for antibodies to the parasite were more than twice as likely to be involved in traffic accidents.

People who are heterozygous for the D antigen appear less likely to develop the negative neurological and mental effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection. This could help explain why both phenotypes (Rh+ and Rh-) are maintained in most populations. There are also striking geographic differences in the prevalence of toxoplasmosis worldwide, ranging from zero to 95 per cent in different regions. This could explain geographic variation in the D antigen worldwide, because its strength as a selective agent would vary with its prevalence.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Myth |

Reality |

| "Your nutritional needs can be determined by your ABO blood type. Knowing your blood type allows you to choose the appropriate foods that will help you lose weight, increase your energy, and live a longer, healthier life." | This idea was proposed in 1996 in a New York Times bestseller Eat Right for Your Type, by Peter D’Adamo, a naturopath. Naturopathy is a method of treating disorders that involves the use of herbs, sunlight, fresh air, and other natural substances. Some medical doctors consider naturopathy a pseudoscience. A major scientific review of the blood type diet could find no evidence to support it. In one study, adults eating the diet designed for blood type A showed improved health — but this occurred in everyone, regardless of their blood type. Because the blood type diet is based solely on blood type, it fails to account for other factors that might require dietary adjustments or restrictions. For example, people with diabetes — but different blood types — would follow different diets, and one or both of the diets might conflict with standard diabetes dietary recommendations and be dangerous. |

| "ABO blood type is associated with certain personality traits. People with blood type A, for example, are patient and responsible, but may also be stubborn and tense, whereas people with blood type B are energetic and creative, but may also be irresponsible and unforgiving. In selecting a spouse, both your own and your potential mate’s blood type should be taken into account to ensure compatibility of your personalities." | The belief that blood type is correlated with personality is widely held in Japan and other East Asian countries. The idea was originally introduced in the 1920s in a study commissioned by the Japanese government, but it was later shown to have no scientific support. The idea was revived in the 1970s by a Japanese broadcaster, who wrote popular books about it. There is no scientific basis for the idea, and it is generally dismissed as pseudoscience by the scientific community. Nonetheless, it remains popular in East Asian countries, just as astrology is popular in many other countries. |

6.5 Summary

- Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of antigens on the surface of red blood cells. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens.

- Antigens are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self or non-self. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens, leading to the destruction of cells bearing the antigens.

- The ABO blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by a single gene with three common alleles on chromosome 9. There are four possible ABO blood types: A, B, AB, and O. The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. People with type O blood are universal donors, and people with type AB blood are universal recipients.

- The frequencies of ABO blood type alleles and blood groups vary around the world. The allele for the B antigen is least common, and blood type O is the most common. The evolutionary forces of founder effect, genetic drift, and natural selection are responsible for the geographic distribution of ABO alleles and blood types. People with type O blood, for example, may be somewhat resistant to malaria, possibly giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.