17.4 Innate Immune System

Paper Cut

It’s just a paper cut, but the break in your skin could provide an easy way for pathogens to enter your body. If bacteria were to enter through the cut and infect the wound, your innate immune system would quickly respond with a dizzying array of general defenses.

What Is the Innate Immune System?

The innate immune system is a subset of the human immune system that produces rapid, but non-specific responses to pathogens. Innate responses are generic, rather than tailored to a particular pathogen. The innate system responds in the same general way to every pathogen it encounters. Although the innate immune system provides immediate and rapid defenses against pathogens, it does not confer long-lasting immunity to them. In most organisms, the innate immune system is the dominant system of host defense. Other than most vertebrates (including humans), the innate immune system is the only system of host defense.

In humans, the innate immune system includes surface barriers, inflammation, the complement system, and a variety of cellular responses. Surface barriers of various types generally keep most pathogens out of the body. If these barriers fail, then other innate defenses are triggered. The triggering event is usually the identification of pathogens by pattern-recognition receptors on cells of the innate immune system. These receptors recognize molecules that are broadly shared by pathogens, but distinguishable from host molecules. Alternatively, the other innate defenses may be triggered when damaged, injured, or stressed cells send out alarm signals, many of which are recognized by the same receptors as those that recognize pathogens.

Barriers to Pathogens

The body’s first line of defense consists of three different types of barriers that keep most pathogens out of body tissues. The types of barriers are mechanical, chemical, and biological barriers.

Mechanical Barriers

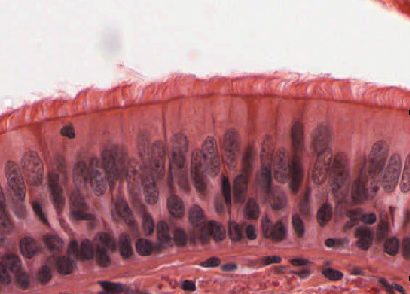

Mechanical barriers are the first line of defense against pathogens, and they physically block pathogens from entering the body. The skin is the most important mechanical barrier. In fact, it is the single most important defense the body has. The outer layer of skin — the epidermis — is tough, and very difficult for pathogens to penetrate. It consists of dead cells that are constantly shed from the body surface, a process that helps remove bacteria and other infectious agents that have adhered to the skin. The epidermis also lacks blood vessels and is usually lacking moisture, so it does not provide a suitable environment for most pathogens. Hair — which is an accessory organ of the skin — also helps keep out pathogens. Hairs inside the nose may trap larger pathogens and other particles in the air before they can enter the airways of the respiratory system (see Figure 17.4.2).

Mucous membranes provide a mechanical barrier to pathogens and other particles at body openings. These membranes also line the respiratory, gastrointestinal, urinary, and reproductive tracts. Mucous membranes secrete mucus, which is a slimy and somewhat sticky substance that traps pathogens. Many mucous membranes also have hair-like cilia that sweep mucus and trapped pathogens toward body openings, where they can be removed from the body. When you sneeze or cough, mucus and pathogens are mechanically ejected from the nose and throat, as you can see in Figure 17.4.3. A sneeze can travel as fast as 160 Km/hr (about 99 mi/hour) and expel as many as 100,000 droplets into the air around you (a good reason to cover your sneezes!). Other mechanical defenses include tears, which wash pathogens from the eyes, and urine, which flushes pathogens out of the urinary tract.

Chemical Barriers

Chemical barriers also protect against infection by pathogens. They destroy pathogens on the outer body surface, at body openings, and on inner body linings. Sweat, mucus, tears, saliva, and breastmilk all contain antimicrobial substances (such as the enzyme lysozyme) that kill pathogens, especially bacteria. Sebaceous glands in the dermis of the skin secrete acids that form a very fine, slightly acidic film on the surface of the skin. This film acts as a barrier to bacteria, viruses, and other potential contaminants that might penetrate the skin. Urine and vaginal secretions are also too acidic for many pathogens to endure. Semen contains zinc — which most pathogens cannot tolerate — as well as defensins, which are antimicrobial proteins that act mainly by disrupting bacterial cell membranes. In the stomach, stomach acid and digestive enzymes called proteases (which break down proteins) kill most of the pathogens that enter the gastrointestinal tract in food or water.

Biological Barriers

Biological barriers are living organisms that help protect the body from pathogens. Trillions of harmless bacteria normally live on the human skin and in the urinary, reproductive, and gastrointestinal tracts. These bacteria use up food and surface space that help prevent pathogenic bacteria from colonizing the body. Some of these harmless bacteria also secrete substances that change the conditions of their environment, making it less hospitable to potentially harmful bacteria. They may release toxins or change the pH, for example. All of these effects of harmless bacteria reduce the chances that pathogenic microorganisms will be able to reach sufficient numbers and cause illness.

Inflammation

If pathogens manage to breach the barriers protecting the body, one of the first active responses of the innate immune system kicks in. This response is inflammation. The main function of inflammation is to establish a physical barrier against the spread of infection. It also eliminates the initial cause of cell injury, clears out dead cells and tissues damaged from the original insult and the inflammatory process, and initiates tissue repair. Inflammation is often a response to infection by pathogens, but there are other possible causes, including burns, frostbite, and exposure to toxins.

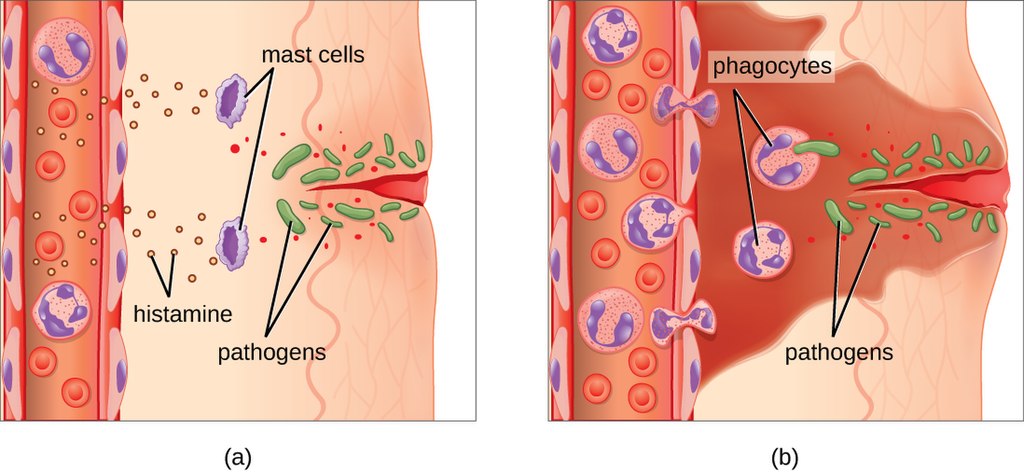

The signs and symptoms of inflammation include redness, swelling, warmth, pain, and frequently some loss of function. These symptoms are caused by increased blood flow into infected tissue, and a number of other processes, illustrated in Figure 17.4.4.

Inflammation is triggered by chemicals such as cytokines and histamines,which are released by injured or infected cells, or by immune system cells such as macrophages (described below) that are already present in tissues. These chemicals cause capillaries to dilate and become leaky, increasing blood flow to the infected area and allowing blood to enter the tissues. Pathogen-destroying leukocytes and tissue-repairing proteins migrate into tissue spaces from the bloodstream to attack pathogens and repair their damage. Cytokines also promote chemotaxis, which is migration to the site of infection by pathogen-destroying leukocytes. Some cytokines have anti-viral effects. They may shut down protein synthesis in host cells, which viruses need in order to survive and replicate.

See the video “The inflammatory response” by Neural Academy to learn about inflammatory response in more detail:

The inflammatory response, Neural Academy, 2019.

Complement System

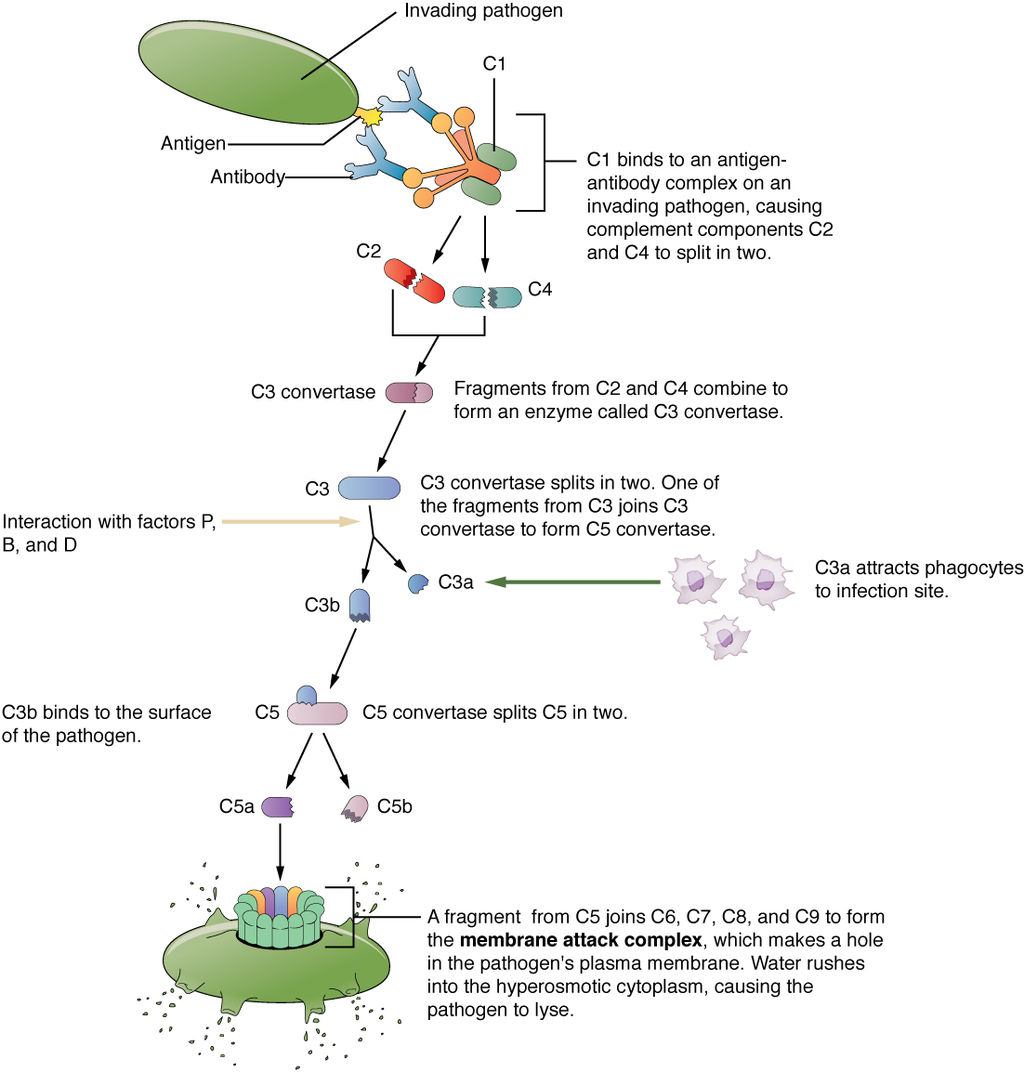

The complement system is a complex biochemical mechanism named for its ability to “complement” the killing of pathogens by antibodies, which are produced as part of an adaptive immune response. The complement system consists of more than two dozen proteins normally found in the blood and synthesized in the liver. The proteins usually circulate as non-functional precursor molecules until activated.

As shown in Figure 17.4.5, when the first protein in the complement series is activated —typically by the binding of an antibody to an antigen on a pathogen — it sets in motion a domino effect. Each component takes its turn in a precise chain of steps known as the complement cascade. The end product is a cylinder that punctures a hole in the pathogen’s cell membrane. This allows fluids and molecules to flow in and out of the cell, which swells and bursts.

Cellular Responses

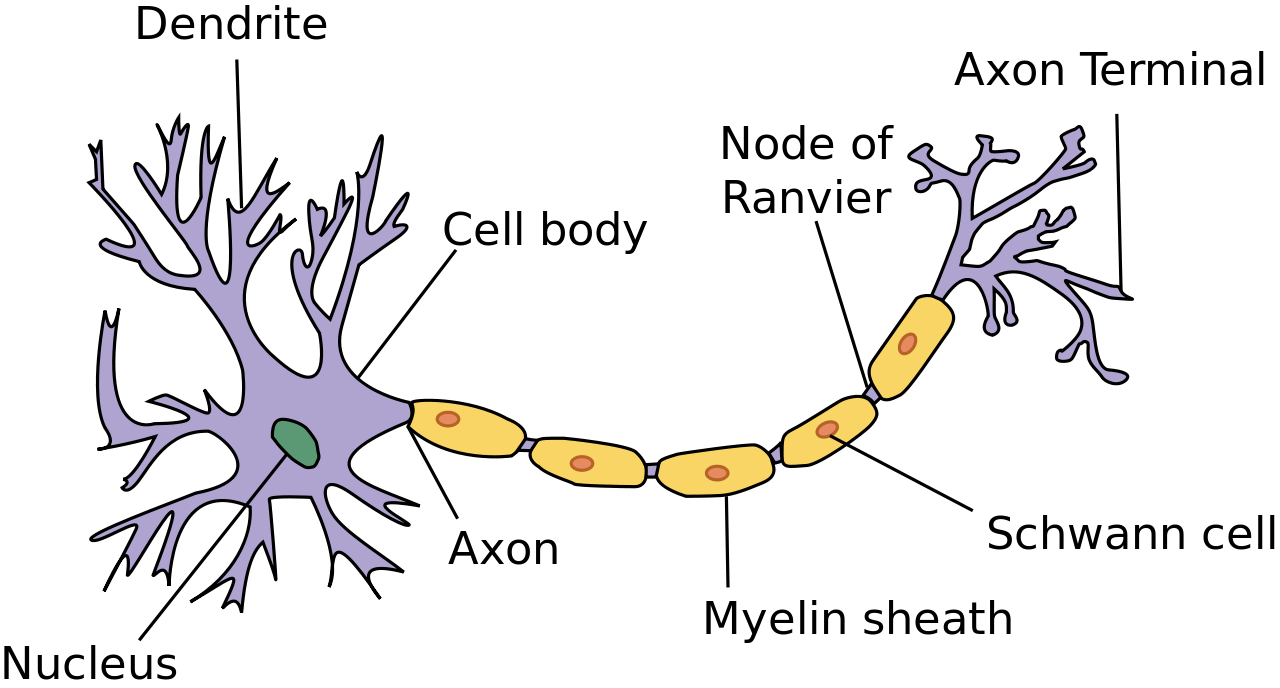

Cellular responses of the innate immune system involve a variety of different types of leukocytes. Many of these leukocytes circulate in the blood and act like independent, single-celled organisms, searching out and destroying pathogens in the human host. These and other immune cells of the innate system identify pathogens or debris, and then help to eliminate them in some way. One way is by phagocytosis.

Phagocytosis

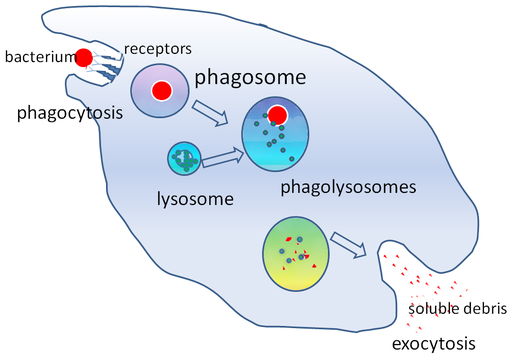

Phagocytosis is an important feature of innate immunity that is performed by cells classified as phagocytes. In the process of phagocytosis, phagocytes engulf and digest pathogens or other harmful particles. Phagocytes generally patrol the body searching for pathogens, but they can also be called to specific locations by the release of cytokines when inflammation occurs. Some phagocytes reside permanently in certain tissues.

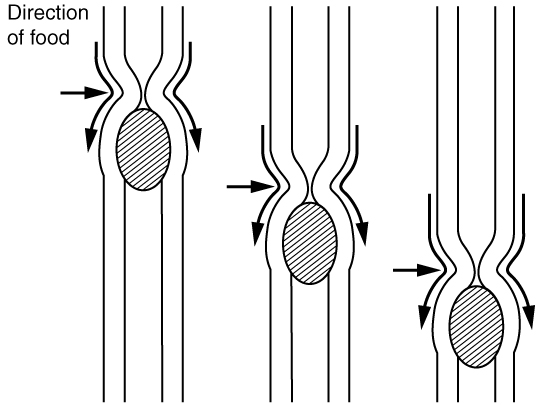

As shown in Figure 17.4.6, when a pathogen such as a bacterium is encountered by a phagocyte, the phagocyte extends a portion of its plasma membrane, wrapping the membrane around the pathogen until it is enveloped. Once inside the phagocyte, the pathogen becomes enclosed within an intracellular vesicle called a phagosome. The phagosome then fuses with another vesicle called a lysosome, forming a phagolysosome. Digestive enzymes and acids from the lysosome kill and digest the pathogen in the phagolysosome. The final step of phagocytosis is excretion of soluble debris from the destroyed pathogen through exocytosis.

Types of leukocytes that kill pathogens by phagocytosis include neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells. You can see illustrations of these and other leukocytes involved in innate immune responses in Figure 17.4.7.

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are leukocytes that travel throughout the body in the blood. They are usually the first immune cells to arrive at the site of an infection. They are the most numerous types of phagocytes, and they normally make up at least half of the total circulating leukocytes. The bone marrow of a normal healthy adult produces more than 100 billion neutrophils per day. During acute inflammation, more than ten times that many neutrophils may be produced each day. Many neutrophils are needed to fight infections, because after a neutrophil phagocytizes just a few pathogens, it generally dies.

Macrophages

Macrophages are large phagocytic leukocytes that develop from monocytes. Macrophages spend much of their time within the interstitial fluid in body tissues. They are the most efficient phagocytes, and they can phagocytize substantial numbers of pathogens or other cells. Macrophages are also versatile cells that produce a wide array of chemicals — including enzymes, complement proteins, and cytokines — in addition to their phagocytic action. As phagocytes, macrophages act as scavengers that rid tissues of worn-out cells and other debris, as well as pathogens. In addition, macrophages act as antigen-presenting cells that activate the adaptive immune system.

Dendritic Cells

Like macrophages, dendritic cells develop from monocytes. They reside in tissues that have contact with the external environment, so they are located mainly in the skin, nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines. Besides engulfing and digesting pathogens, dendritic cells also act as antigen-presenting cells that trigger adaptive immune responses.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils are non-phagocytic leukocytes that are related to neutrophil. They specialize in defending against parasites. They are very effective in killing large parasites (such as worms) by secreting a range of highly-toxic substances when activated. Eosinophils may become overactive and cause allergies or asthma.

Basophils

Basophils are non-phagocytic leukocytes that are also related to neutrophils. They are the least numerous of all white blood cells. Basophils secrete two types of chemicals that aid in body defenses: histamines and heparin. Histamines are responsible for dilating blood vessels and increasing their permeability in inflammation. Heparin inhibits blood clotting, and also promotes the movement of leukocytes into an area of infection.

Mast Cells

Mast cells are non-phagocytic leukocytes that help initiate inflammation by secreting histamines. In some people, histamines trigger allergic reactions, as well as inflammation. Mast cells may also secrete chemicals that help defend against parasites.

Natural Killer Cells

Natural killer cells are in the subset of leukocytes called lymphocytes, which are produced by the lymphatic system. Natural killer cells destroy cancerous or virus-infected host cells, although they do not directly attack invading pathogens. Natural killer cells recognize these host cells by a condition they exhibit called “missing self.” Cells with missing self have abnormally low levels of cell-surface proteins of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), which normally identify body cells as self.

Innate Immune Evasion

Many pathogens have evolved mechanisms that allow them to evade human hosts’ innate immune systems. Some of these mechanisms include:

- Invading host cells to replicate so they are “hidden” from the immune system. The bacterium that causes tuberculosis uses this mechanism.

- Forming a protective capsule around themselves to avoid being destroyed by immune system cells. This defense occurs in bacteria, such as Salmonella species.

- Mimicking host cells so the immune system does not recognize them as foreign. Some species of Staphylococcus bacteria use this mechanism.

- Directly killing phagocytes. This ability evolved in several species of bacteria, including the species that causes anthrax.

- Producing molecules that prevent the formation of interferons, which are immune chemicals that fight viruses. Some influenza viruses have this capability.

- Forming complex biofilms that provide protection from the cells and proteins of the immune system. This characterizes some species of bacteria and fungi. You can see an example of a bacterial biofilm on teeth in Figure 17.4.8.

17.4 Summary

- The innate immune system is a subset of the human immune system that produces rapid, but non-specific responses to pathogens. Unlike the adaptive immune system, the innate system does not confer immunity. The innate immune system includes surface barriers, inflammation, the complement system, and a variety of cellular responses.

- The body’s first line of defense consists of three different types of barriers that keep most pathogens out of body tissues. The types of barriers are mechanical, chemical, and biological barriers.

- Mechanical barriers — which include the skin, mucous membranes, and fluids such as tears and urine — physically block pathogens from entering the body. Chemical barriers — such as enzymes in sweat, saliva, and semen — kill pathogens on body surfaces. Biological barriers are harmless bacteria that use up food and space so pathogenic bacteria cannot colonize the body.

- If pathogens breach protective barriers, inflammation occurs. This creates a physical barrier against the spread of infection, and repairs tissue damage. Inflammation is triggered by chemicals such as cytokines and histamines, and it causes swelling, redness, and warmth.

- The complement system is a complex biochemical mechanism that helps antibodies kill pathogens. Once activated, the complement system consists of more than two dozen proteins that lead to disruption of the cell membrane of pathogens and bursting of the cells.

- Cellular responses of the innate immune system involve various types of leukocytes. For example, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells phagocytize pathogens. Basophils and mast cells release chemicals that trigger inflammation. Natural killer cells destroy cancerous or virus-infected cells, and eosinophils kill parasites.

- Many pathogens have evolved mechanisms that help them evade the innate immune system. For example, some pathogens form a protective capsule around themselves, and some mimic host cells so the immune system does not recognize them as foreign.

17.4 Review Questions

- What is the innate immune system?

- Identify the body’s first line of defense.

-

- What are biological barriers? How do they protect the body?

- State the purposes of inflammation. What triggers inflammation, and what signs and symptoms does it cause?

- Define the complement system. How does it help destroy pathogens?

- Describe two ways that pathogens can evade the innate immune system.

- What are the ways in which phagocytes can encounter pathogens in the body?

- Describe two different ways in which enzymes play a role in the innate immune response.

17.4 Explore More

How mucus keeps us healthy – Katharina Ribbeck, TED-Ed, 2015.

Human Physiology – Innate Immune System, Janux, 2015.

Myriam Sidibe: The simple power of handwashing, TED, 2014.

Everything You Didn’t Want To Know About Snot, Gross Science, 2017.

Cough Grosser Than Sneeze? | Curiosity – World’s Dirtiest Man, Discovery, 2011.

Attributions

Figure 17.4.1

Oww_Papercut_14365 by Laurence Facun on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 17.4.2

hairy-nose by Piotr Siedlecki on publicdomainpictures.net is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) license.

Figure 17.4.3

1024px-Sneeze by James Gathany/ CDC Public Health Image library (PHIL) ID# 11162 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 17.4.4

OSC_Microbio_17_06_Erythema by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 17.4.5

2212_Complement_Cascade_and_Function by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 17.4.6

512px-Phagocytosis2 by Graham Colm at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 17.4.7

Innate_Immune_cells.svg by Fred the Oyster on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 17.4.8

1024px-Gingivitis-before-and-after-3 by Onetimeuseaccount on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 21.13 Complement cascade and function [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 21.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-2-barrier-defenses-and-the-innate-immune-response

Discovery. (2011, October 27). Cough grosser than sneeze? | Curiosity – World’s dirtiest man. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dy1D3d1FBcw&feature=youtu.be

Gross Science. (2017, January 31). Everything you didn’t want to know about snot. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shEPwQPQG4I&feature=youtu.be

Janux. (2015, January 10). Human physiology – Innate immune system. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYjtMP67vyk&feature=youtu.be

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Anthrax [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anthrax/symptoms-causes/syc-20356203

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Influenza (flu) [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/flu/symptoms-causes/syc-20351719

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Salmonella infection [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/salmonella/symptoms-causes/syc-20355329

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Staph infection [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/staph-infections/multimedia/staph-infection/img-20008600

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Tuberculosis [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tuberculosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351250

OpenStax. (2016, November 11). Figure 17.23 A typical case of acute inflammation at the site of a skin wound – Erythema [digital image]. In OpenStax, Microbiology (Section 17.5). https://openstax.org/details/books/microbiology?Bookdetails

TED. (2014, October 14). Myriam Sidibe: The simple power of handwashing. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c64M1tZyWPM&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2015, November 5). How mucus keeps us healthy – Katharina Ribbeck. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WW4skW6gucU&feature=youtu.be

A microorganism which causes disease.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Flight Risk

Nineteen-year-old Malcolm is about to take his first plane flight. Shortly after he boards the plane and sits down, a man in his late sixties sits next to him in the aisle seat. About half an hour after the plane takes off, the pilot announces that she is turning the seat belt light off, and that it is safe to move around the cabin.

The man in the aisle seat — who has introduced himself to Malcolm as Willie — immediately unbuckles his seat belt and paces up and down the aisle a few times before returning to his seat. After about 45 minutes, Willie gets up again, walks some more, then sits back down and does some foot and leg exercises. After the third time Willie gets up and paces the aisles, Malcolm asks him whether he is walking so much to accumulate steps on a pedometer or fitness tracking device. Willie laughs and says no. He is actually trying to do something even more important for his health — prevent a blood clot from forming in his legs.

Willie explains that he has a chronic condition: heart failure. Although it sounds scary, his condition is currently well-managed, and he is able to lead a relatively normal lifestyle. However, it does put him at risk of developing other serious health conditions, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which is when a blood clot occurs in the deep veins, usually in the legs. Air travel — and other situations where a person has to sit for a long period of time — increases the risk of DVT. Willie’s doctor said that he is healthy enough to fly, but that he should walk frequently and do leg exercises to help avoid a blood clot.

As you read this chapter, you will learn about the heart, blood vessels, and blood that make up the cardiovascular system, as well as disorders of the cardiovascular system, such as heart failure. At the end of the chapter you will learn more about why DVT occurs, why Willie has to take extra precautions when he flies, and what can be done to lower the risk of DVT and its potentially deadly consequences.

Chapter Overview: Cardiovascular System

In this chapter, you will learn about the cardiovascular system, which transports substances throughout the body. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The major components of the cardiovascular system: the heart, blood vessels, and blood.

- The functions of the cardiovascular system, including transporting needed substances (such as oxygen and nutrients) to the cells of the body, and picking up waste products.

- How blood is oxygenated through the pulmonary circulation, which transports blood between the heart and lungs.

- How blood is circulated throughout the body through the systemic circulation.

- The components of blood — including plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets — and their specific functions.

- Types of blood vessels — including arteries, veins, and capillaries — and their functions, similarities, and differences.

- The structure of the heart, how it pumps blood, and how contractions of the heart are controlled.

- What blood pressure is and how it is regulated.

- Blood disorders, including anemia, HIV, and leukemia.

- Cardiovascular diseases (including heart attack, stroke, and angina), and the risk factors and precursors — such as high blood pressure and atherosclerosis — that contribute to them.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- What is heart failure?Why do you think it increases the risk of DVT?

- What is a blood clot? What are possible health consequences of blood clots?

- Why do you think sitting for long periods of time increases the risk of DVT? Why does walking and exercising the legs help reduce this risk?

Attribution

Figure 14.1.1

aircraft-1583871_1920 [photo] by olivier89 from Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/de/service/license/).

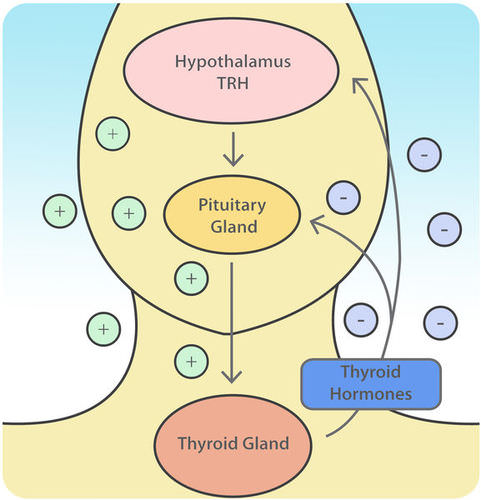

Image shows a diagram of the negative feedback loop governing thyroid gland function. In the absence of sufficient levels of thyroid hormones, the hypothalamus will secrete TRH, which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete TSH, which stimulates the thyroid gland to make thyroid hormones. Sufficient blood levels of thyroid hormone inhibit the hypothalamus from secreting TRH, halting the pathway, until thyroid hormone level sdrop again

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Wearing His Heart on His Sleeve

Aiko, 22, and Larissa, 23, met through mutual friends and hit it off right away. They began dating and just four months later, they are now madly in love. They spend as much time as they can with each other, and have decided to move in together when Larissa’s roommate moves out. They are even discussing getting married one day.

Inspired by his passion for Larissa, Aiko is considering getting her name tattooed on his arm. As you probably know, tattoos are designs on the skin created by injecting pigments into the skin with a needle. Aiko looks up different tattoo styles online, and starts to envision what he would want in a tattoo.

One day at a street festival, Aiko sees a sign that says “Henna Tattoos.” Henna tattoos are not technically tattoos — they are temporary designs that artists can create on the skin using a paste made out of the leaves of the henna plant. The henna stains the skin a reddish-brown colour, and once the paste is scraped off, the design typically remains on the skin for a few weeks. The use of henna to create designs on the skin is called mehndi. It is traditionally used by people in and from regions such as India, Pakistan, the Middle East, and Africa to celebrate special occasions, particularly weddings. Mendhi is often done on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, where the designs usually come out darker than on other areas of the skin. You can see some examples of henna art in the images below.

Figure 10.1.2 Examples of henna art.

Aiko asks the mehndi artist to inscribe Larissa’s name on his arm, so that he can see whether he likes it without making the permanent commitment of a real tattoo. Two days later, Aiko visits his parents. They are not familiar with mehndi, and they have a moment of panic when they think he got a real tattoo. Aiko reassures them that it is temporary, but tells them that he is thinking about getting a real tattoo.

His parents are concerned. His father points out that he has not known Larissa long — what if they break up and he regrets the tattoo? His mother additionally worries about whether tattoos are safe. Aiko says that he doesn’t think he will regret the decision, but if he does, he can cover it up with another tattoo or get it removed with laser treatments. He also tells them that he would go to an artist and shop that are reputable, and take appropriate safety precautions. His parents warn him that getting a tattoo removed may not be as simple as he thinks, and that he should think very carefully before making such a permanent decision.

Humans have long decorated and adorned their skin with tattoos, makeup, and piercings. They also colour, cut, straighten, curl, and remove their hair; and paint, grow, and cut their nails. The skin, hair, and nails make up the integumentary system. As you read this chapter, you will learn about the important biological functions that these organs carry out, beyond being a convenient canvas for personal expression. At the end of the chapter you will find out if Aiko got his tattoo. You will also learn more about how tattoos, mehndi, and laser tattoo removal work, as well as the important considerations to protect your health if you are thinking about getting a tattoo.

Chapter 10 Overview: Integumentary System

In this chapter you will learn about the structure and functions of the integumentary system, along with its relationships to culture, evolution, and health. Specifically, you will learn about:

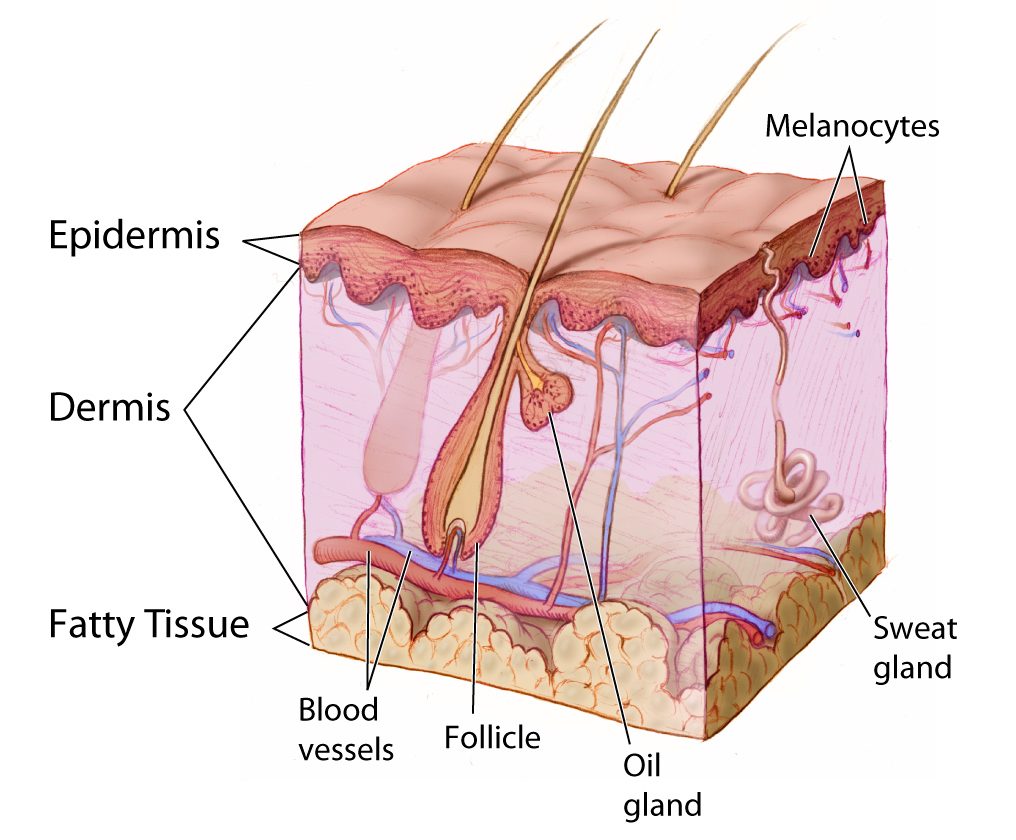

- The functions of the organs of the integumentary system — the skin, hair, and nails — including protecting the body, helping to regulate homeostasis, and sensing and interacting with the external world.

- The two main layers of the skin: the thinner outer layer (called the epidermis) and the thicker inner layer (called the dermis).

- The cells and layers of the epidermis and their functions, including synthesizing vitamin D and protecting the body against injury, pathogens, UV light exposure, and water loss.

- The composition of epidermal cells and how the epidermis grows.

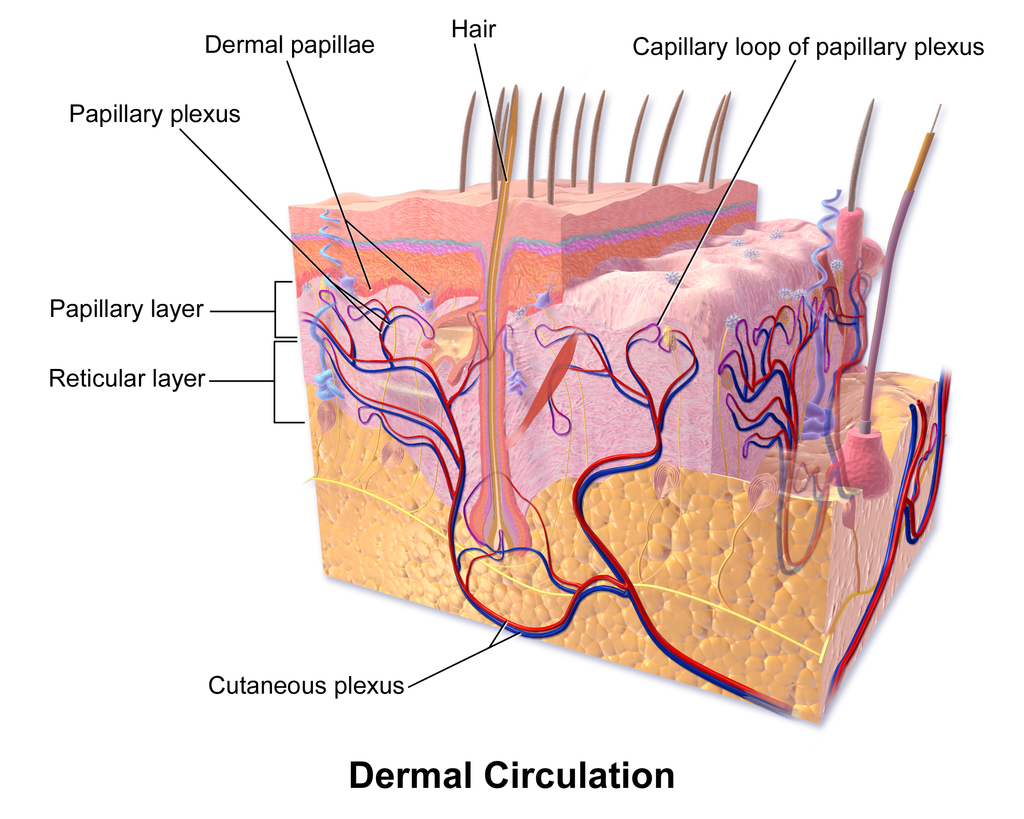

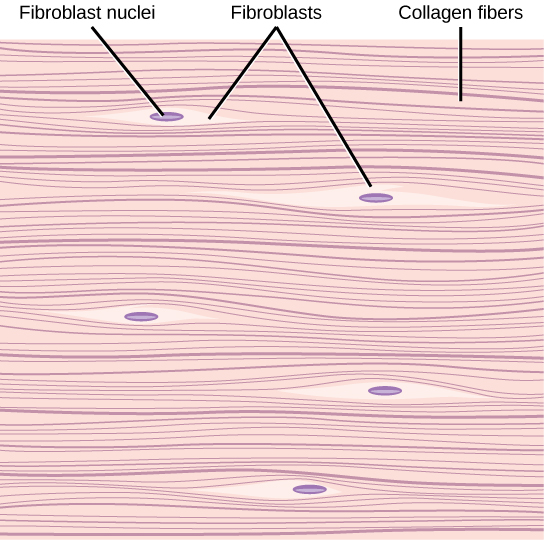

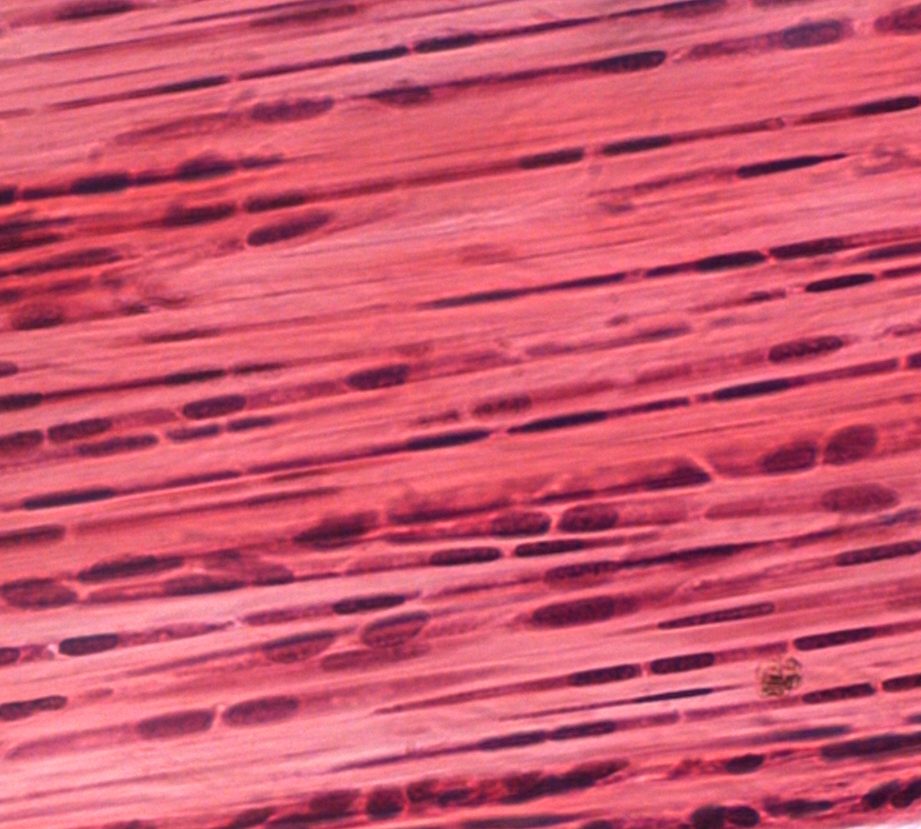

- The composition and layers of the dermis and their functions, including cushioning other tissues, regulating body temperature, sensing the environment, and excreting wastes.

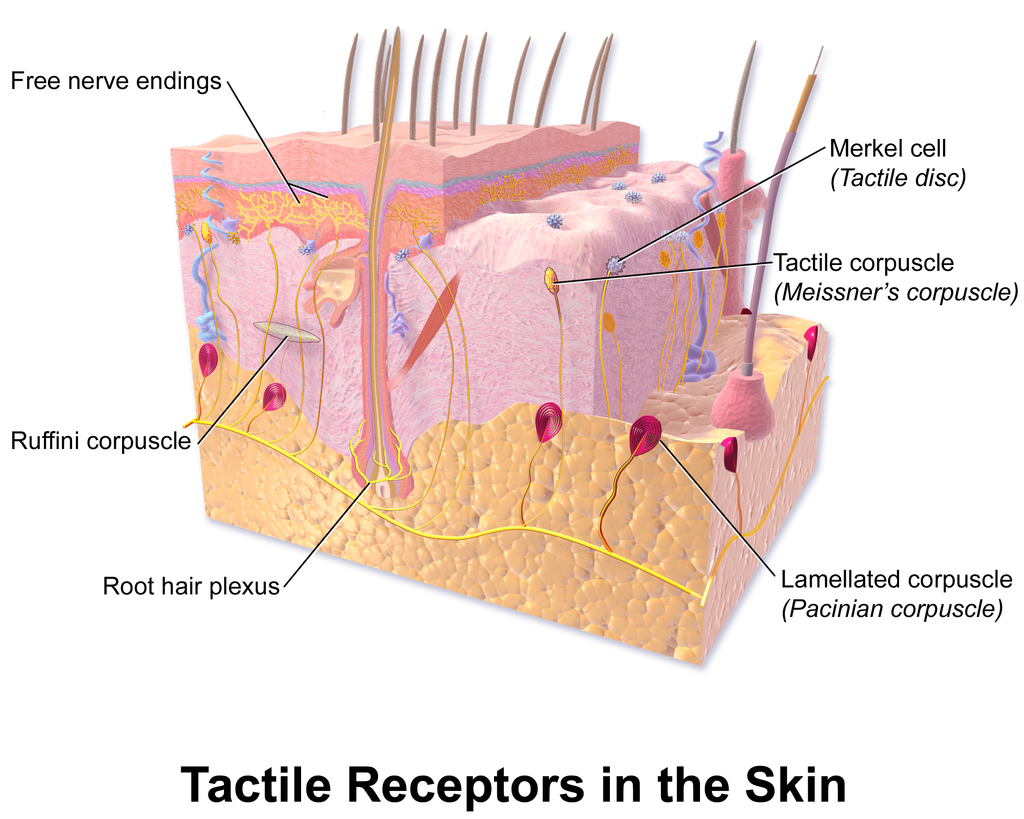

- The specialized structures in the dermis, which include sweat and sebaceous (oil) glands, hair follicles, and sensory receptors that detect touch, temperature, and pain.

- The structure and biological functions of hair, which include retaining body heat, detecting sensory stimuli, and protecting the body against UV light, pathogens, and small particles.

- How hair grows, how variations in hair colour and texture arise, and hypotheses about the evolution of hair in humans.

- The sociocultural roles of hair, including its expression of characteristics like sex and age, as well as cultural identity and social cues.

- The structure and functions of nails, which includes protecting the fingers and toes, enhancing the detection of sensory stimuli, and acting as tools.

- How nails grow and how they can reflect and affect our health.

- Skin cancer — which is the most common form of cancer — and its types and risk factors.

As you read the chapter and learn more about the skin, think about the following questions:

- Why do you think real tattoos are permanent, but mehndi is not?

- Why do you think mehndi might come out darker on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet than on other areas of the skin?

- What do you think are some of the health concerns about tattoos?

Attributions

Figure 10.1.1

Arm tattoo by telly telly on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 10.1.2

- Henna for hair by Andrey "A.I." Sitnik ( www.sitnik.ru ) on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

- Henna on foot in Morocco by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

- Mehndi (front) by AKS.9955 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

- Tags: Hand Jewelry Ornaments. . .Henna by BenBernardBags on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/ja/service/license/).

visible part of a nail that is external to the skin

The outer layer of skin that consists mainly of epithelial cells and lacks nerve endings, blood vessels, and other structures.

a colorless cell that circulates in the blood and body fluids and is involved in counteracting foreign substances and disease; a white (blood) cell. There are several types, all amoeboid cells with a nucleus, including lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.

The space occurring between two or more membranes. In cell biology, it's most commonly described as the region between the inner membrane and the outer membrane of a mitochondrion or a chloroplast.

Image shows an operating room. There are several surgeons in gowns, masks and gloves. They are operating on a patient.

Image shows a man jogging in the forest. His shirt is wet with sweat.

Image shows a diagram of the layers of the epidermis. The outermost layer is the stratum corneum, below that is the stratum lucidum, below that the stratum granulosum, below that the stratum spinosum, below that the stratum basale, and then a basement membrane which connects the dermis to the epidermis.

Image shows a scraped knee. It is bleeding slightly.

Image shows a

Image shows a pictomicrograph of staphylococcus.

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large, Y-shaped protein produced mainly by plasma cells that is used by the immune system to neutralize pathogens such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Doing the ‘Fly

The swimmer in the Figure 13.3.1 photo is doing the butterfly stroke, a swimming style that requires the swimmer to carefully control his breathing so it is coordinated with his swimming movements. Breathing is the process of moving air into and out of the lungs, which are the organs in which gas exchange takes place between the atmosphere and the body. Breathing is also called ventilation, and it is one of two parts of the life-sustaining process of respiration. The other part is gas exchange. Before you can understand how breathing is controlled, you need to know how breathing occurs.

How Breathing Occurs

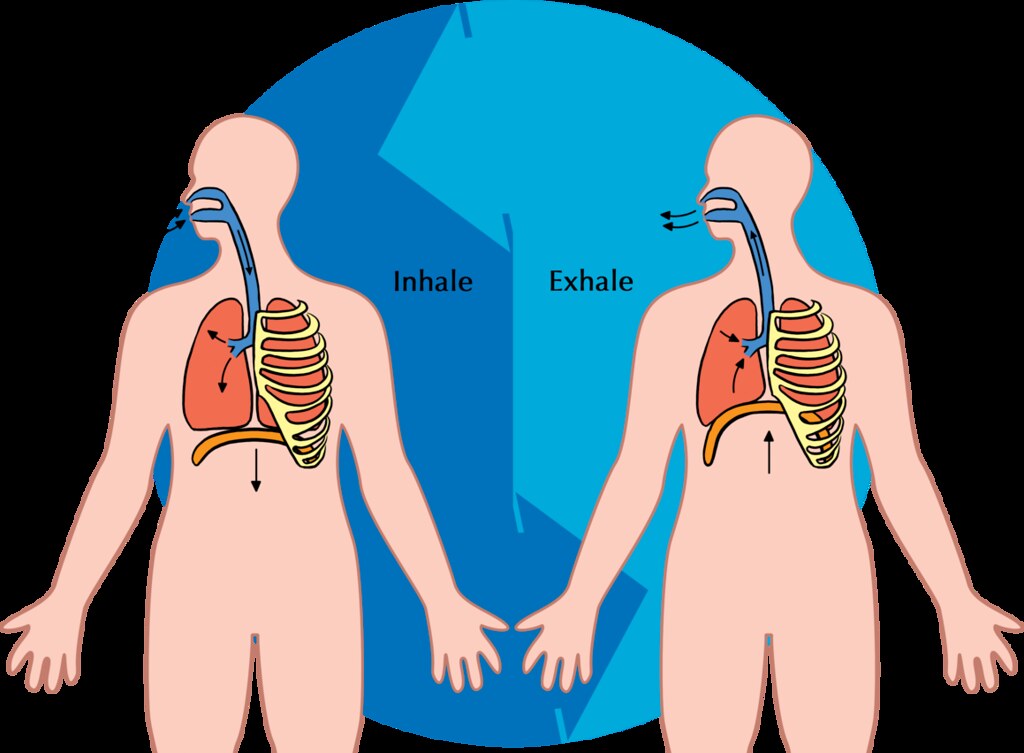

Breathing is a two-step process that includes drawing air into the lungs, or inhaling, and letting air out of the lungs, or exhaling. Both processes are illustrated in Figure 13.3.2.

Inhaling

Inhaling is an active process that results mainly from contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm, shown in Figure 13.3.2. The diaphragm is a large, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs that separates the thoracic (chest) and abdominal cavities. When the diaphragm contracts it moves down causing the thoracic cavity to expand, and the contents of the abdomen to be pushed downward. Other muscles — such as intercostal muscles between the ribs — also contribute to the process of inhalation, especially when inhalation is forced, as when taking a deep breath. These muscles help increase thoracic volume by expanding the ribs outward. The increase in thoracic volume creates a decrease in thoracic air pressure. With the chest expanded, there is lower air pressure inside the lungs than outside the body, so outside air flows into the lungs via the respiratory tract according the the pressure gradient (high pressure flows to lower pressure).

Exhaling

Exhaling involves the opposite series of events. The diaphragm relaxes, so it moves upward and decreases the volume of the thorax. Air pressure inside the lungs increases, so it is higher than the air pressure outside the lungs. Exhalation, unlike inhalation, is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs. With the change in air pressure, the lungs contract to their pre-inflated size, forcing out the air they contain in the process. Air flows out of the lungs, similar to the way air rushes out of a balloon when it is released. If exhalation is forced, internal intercostal and abdominal muscles may help move the air out of the lungs.

Control of Breathing

Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously, as well as unconsciously. Think about using your breath to blow up a balloon. You take a long, deep breath, and then you exhale the air as forcibly as you can into the balloon. Both the inhalation and exhalation are consciously controlled.

Conscious Control of Breathing

You can control your breathing by holding your breath, slowing your breathing, or hyperventilating, which is breathing more quickly and shallowly than necessary. You can also exhale or inhale more forcefully or deeply than usual. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities besides blowing up balloons, including swimming, speech training, singing, playing many different musical instruments (Figure 13.3.3), and doing yoga, to name just a few.

There are limits on the conscious control of breathing. For example, it is not possible for a healthy person to voluntarily stop breathing indefinitely. Before long, there is an irrepressible urge to breathe. If you were able to stop breathing for a long enough time, you would lose consciousness. The same thing would happen if you were to hyperventilate for too long. Once you lose consciousness so you can no longer exert conscious control over your breathing, involuntary control of breathing takes over.

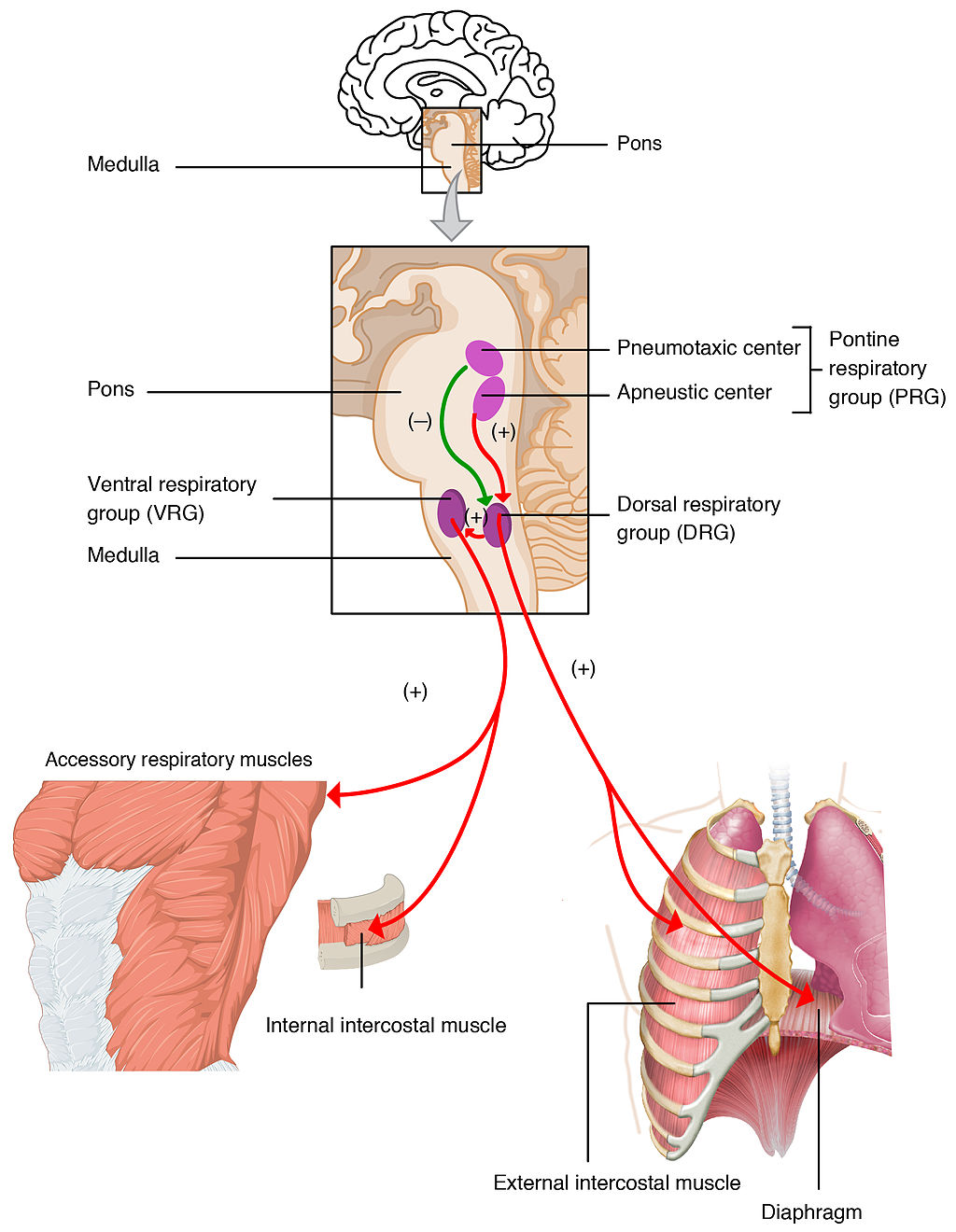

Unconscious Control of Breathing

Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem (see Figure 13.3.4). The respiratory centers automatically and continuously regulate the rate of breathing based on the body’s needs. These are determined mainly by blood acidity, or pH. When you exercise, for example, carbon dioxide levels increase in the blood, because of increased cellular respiration by muscle cells. The carbon dioxide reacts with water in the blood to produce carbonic acid, making the blood more acidic, so pH falls. The drop in pH is detected by chemoreceptors in the medulla. Blood levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide, in addition to pH, are also detected by chemoreceptors in major arteries, which send the “data” to the respiratory centers. The latter respond by sending nerve impulses to the diaphragm, “telling” it to contract more quickly so the rate of breathing speeds up. With faster breathing, more carbon dioxide is released into the air from the blood, and blood pH returns to the normal range.

The opposite events occur when the level of carbon dioxide in the blood becomes too low and blood pH rises. This may occur with involuntary hyperventilation, which can happen in panic attacks, episodes of severe pain, asthma attacks, and many other situations. When you hyperventilate, you blow off a lot of carbon dioxide, leading to a drop in blood levels of carbon dioxide. The blood becomes more basic (alkaline), causing its pH to rise.

Nasal vs. Mouth Breathing

Nasal breathing is breathing through the nose rather than the mouth, and it is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing. The hair-lined nasal passages do a better job of filtering particles out of the air before it moves deeper into the respiratory tract. The nasal passages are also better at warming and moistening the air, so nasal breathing is especially advantageous in the winter when the air is cold and dry. In addition, the smaller diameter of the nasal passages creates greater pressure in the lungs during exhalation. This slows the emptying of the lungs, giving them more time to extract oxygen from the air.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Drowning is defined as respiratory impairment from being in or under a liquid. It is further classified according to its outcome into: death, ongoing health problems, or no ongoing health problems (full recovery). Four hundred Canadians die annually from drowning, and drowning is one of the leading causes of death in children under the age of five. There are some potentially dangerous myths about drowning, and knowing what they are might save your life or the life of a loved one, especially a child.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| "People drown when they aspirate water into their lungs." | Generally, in the early stages of drowning, very little water enters the lungs. A small amount of water entering the trachea causes a muscular spasm in the larynx that seals the airway and prevents the passage of water into the lungs. This spasm is likely to last until unconsciousness occurs. |

| "You can tell when someone is drowning because they will shout for help and wave their arms to attract attention." | The muscular spasm that seals the airway prevents the passage of air, as well as water, so a person who is drowning is unable to shout or call for help. In addition, instinctive reactions that occur in the final minute or so before a drowning person sinks under the water may look similar to calm, safe behavior. The head is likely to be low in the water, tilted back, with the mouth open. The person may have uncontrolled movements of the arms and legs, but they are unlikely to be visible above the water. |

| "It is too late to save a person who is unconscious in the water." | An unconscious person rescued with an airway still sealed from the muscular spasm of the larynx stands a good chance of full recovery if they start receiving CPR within minutes. Without water in the lungs, CPR is much more effective. Even if cardiac arrest has occurred so the heart is no longer beating, there is still a chance of recovery. The longer the brain goes without oxygen, however, the more likely brain cells are to die. Brain death is likely after about six minutes without oxygen, except in exceptional circumstances, such as young people drowning in very cold water. There are examples of children surviving, apparently without lasting ill effects, for as long as an hour in cold water. Rescuers retrieving a child from cold water should attempt resuscitation even after a protracted period of immersion. |

| "If someone is drowning, you should start administering CPR immediately, even before you try to get the person out of the water." | Removing a drowning person from the water is the first priority, because CPR is ineffective in the water. The goal should be to bring the person to stable ground as quickly as possible and then to start CPR. |

| "You are unlikely to drown unless you are in water over your head." | Depending on circumstances, people have drowned in as little as 30 mm (about 1 ½ in.) of water. Inebriated people or those under the influence of drugs, for example, have been known to have drowned in puddles. Hundreds of children have drowned in the water in toilets, bathtubs, basins, showers, pails, and buckets (see Figure 13.3.5). |

13.3 Summary

- Breathing, or ventilation, is the two-step process of drawing air into the lungs (inhaling) and letting air out of the lungs (exhaling). Inhalation is an active process that results mainly from contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm. Exhalation is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs when the diaphragm relaxes.

- Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously, as well as unconsciously. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities, including swimming and singing. There are limits on the conscious control of breathing, however. If you try to hold your breath, for example, you will soon have an irrepressible urge to breathe.

- Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem. They respond to variations in blood pH by either increasing or decreasing the rate of breathing as needed to return the pH level to the normal range.

- Nasal breathing is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing because it does a better job of filtering, warming, and moistening incoming air. It also results in slower emptying of the lungs, which allows more oxygen to be extracted from the air.

- Drowning is a major cause of death in Canada, in particular in children under the age of five. It is important to supervise small children when they are playing in, around, or with water.

13.3 Review Questions

- Define breathing.

-

- Give examples of activities in which breathing is consciously controlled.

- Explain how unconscious breathing is controlled.

- Young children sometimes threaten to hold their breath until they get something they want. Why is this an idle threat?

- Why is nasal breathing generally considered superior to mouth breathing?

- Give one example of a situation that would cause blood pH to rise excessively. Explain why this occurs.

13.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl4cU9sG_08

How breathing works - Nirvair Kaur, TED-Ed, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDtKBXOEsoM

How do ventilators work? - Alex Gendler, TED-Ed, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFnGhrC_3Gs&feature=emb_logo

How I held my breath for 17 minutes | David Blaine, TED, 2010.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vca6DyFqt4c&feature=emb_logo

The Ultimate Relaxation Technique: How To Practice Diaphragmatic Breathing For Beginners, Kai Simon, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 13.3.1

US_Marines_butterfly_stroke by Cpl. Jasper Schwartz from U.S. Marine Corps on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.3.2

Inhale Exhale/Breathing cycle by Siyavula Education on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 13.3.3

Trumpet/ Frenchmen Street [photo] by Morgan Petroski on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 13.3.4

Respiratory_Centers_of_the_Brain by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 13.3.5

Lily & Ava in the Kiddie Pool by mob mob on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.20 Respiratory centers of the brain [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-3-the-process-of-breathing

Kai Simon. (2015, January 11). The ultimate relaxation technique: How to practice diaphragmatic breathing for beginners. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vca6DyFqt4c&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2010, January 19). How I held my breath for 17 minutes | David Blaine. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFnGhrC_3Gs&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2012, October 4). How breathing works - Nirvair Kaur. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl4cU9sG_08&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, May 21). How do ventilators work? - Alex Gendler. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDtKBXOEsoM&feature=youtu.be

The process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional protein.

a colorless cell that circulates in the blood and body fluids and is involved in counteracting foreign substances and disease; a white (blood) cell. There are several types, all amoeboid cells with a nucleus, including lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.

Image shows a diagram of how alzheimer's progresses. In preclinical AD, just a small portion of the brain is affected. More of the brain and more areas of the brain are affected in mild to moderate AD. In severe AD, most of the brain is affected.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Feel the Burn

The person in Figure 10.3.1 is no doubt feeling the burn — sunburn, that is. Sunburn occurs when the outer layer of the skin is damaged by UV light from the sun or tanning lamps. Some people deliberately allow UV light to burn their skin, because after the redness subsides, they are left with a tan. A tan may look healthy, but it is actually a sign of skin damage. People who experience one or more serious sunburns are significantly more likely to develop skin cancer. Natural pigment molecules in the skin help protect it from UV light damage. These pigment molecules are found in the layer of the skin called the epidermis.

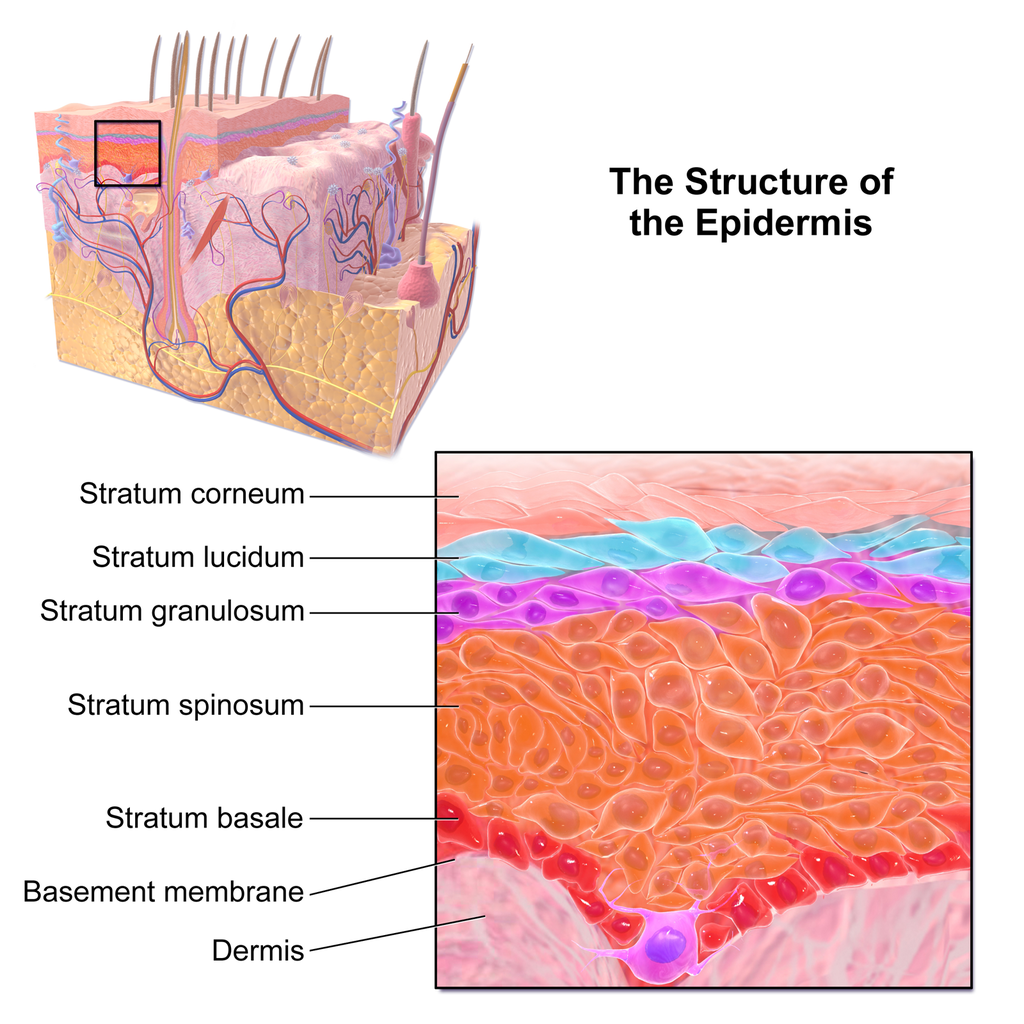

What is the Epidermis?

The epidermis is the outer of the two main layers of the skin. The inner layer is the dermis. It averages about 0.10 mm thick, and is much thinner than the dermis. The epidermis is thinnest on the eyelids (0.05 mm) and thickest on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (1.50 mm). The epidermis covers almost the entire body surface. It is continuous with — but structurally distinct from — the mucous membranes that line the mouth, anus, urethra, and vagina.

Structure of the Epidermis

There are no blood vessels and very few nerve cells in the epidermis. Without blood to bring epidermal cells oxygen and nutrients, the cells must absorb oxygen directly from the air and obtain nutrients via diffusion of fluids from the dermis below. However, as thin as it is, the epidermis still has a complex structure. It has a variety of cell types and multiple layers.

Cells of the Epidermis

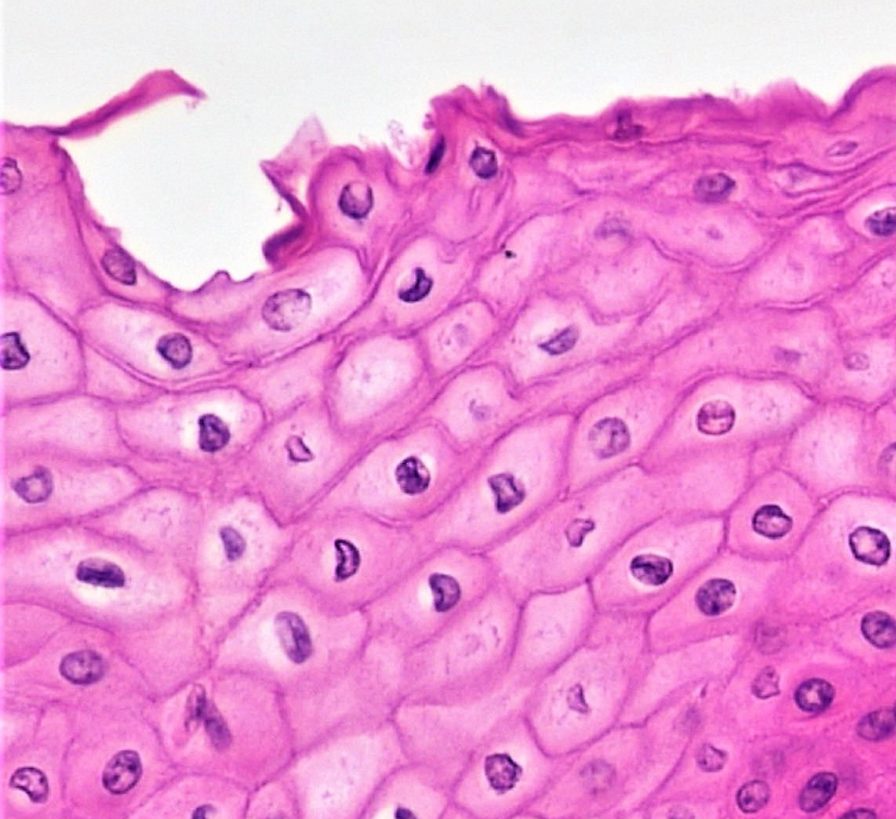

There are several different types of cells in the epidermis. All of the cells are necessary for the important functions of the epidermis.

- The epidermis consists mainly of stacks of keratin-producing epithelial cells called keratinocytes. These cells make up at least 90 per cent of the epidermis. Near the top of the epidermis, these cells are also called squamous cells.

- Another eight per cent of epidermal cells are melanocytes. These cells produce the pigment melanin that protects the dermis from UV light.

- About one per cent of epidermal cells are Langerhans cells. These are immune system cells that detect and fight pathogens entering the skin.

- Less than one per cent of epidermal cells are Merkel cells, which respond to light touch and connect to nerve endings in the dermis.

Layers of the Epidermis

The epidermis in most parts of the body consists of four distinct layers. A fifth layer occurs in the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, where the epidermis is thicker than in the rest of the body. The layers of the epidermis are shown in Figure 10.3.2, and described in the following text.

Stratum Basale

The stratum basale is the innermost (or deepest) layer of the epidermis. It is separated from the dermis by a membrane called the basement membrane. The stratum basale contains stem cells — called basal cells — which divide to form all the keratinocytes of the epidermis. When keratinocytes first form, they are cube-shaped and contain almost no keratin. As more keratinocytes are produced, previously formed cells are pushed up through the stratum basale. Melanocytes and Merkel cells are also found in the stratum basale. The Merkel cells are especially numerous in touch-sensitive areas, such as the fingertips and lips.

Stratum Spinosum

Just above the stratum basale is the stratum spinosum. This is the thickest of the four epidermal layers. The keratinocytes in this layer have begun to accumulate keratin, and they have become tougher and flatter. Spiny cellular projections form between the keratinocytes and hold them together. In addition to keratinocytes, the stratum spinosum contains the immunologically active Langerhans cells.

Stratum Granulosum

The next layer above the stratum spinosum is the stratum granulosum. In this layer, keratinocytes have become nearly filled with keratin, giving their cytoplasm a granular appearance. Lipids are released by keratinocytes in this layer to form a lipid barrier in the epidermis. Cells in this layer have also started to die, because they are becoming too far removed from blood vessels in the dermis to receive nutrients. Each dying cell digests its own nucleus and organelles, leaving behind only a tough, keratin-filled shell.

Stratum Lucidum

Only on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, the next layer above the stratum granulosum is the stratum lucidum. This is a layer consisting of stacks of translucent, dead keratinocytes that provide extra protection to the underlying layers.

Stratum Corneum

The uppermost layer of the epidermis everywhere on the body is the stratum corneum. This layer is made of flat, hard, tightly packed dead keratinocytes that form a waterproof keratin barrier to protect the underlying layers of the epidermis. Dead cells from this layer are constantly shed from the surface of the body. The shed cells are continually replaced by cells moving up from lower layers of the epidermis. It takes a period of about 48 days for newly formed keratinocytes in the stratum basale to make their way to the top of the stratum corneum to replace shed cells.

Functions of the Epidermis

The epidermis has several crucial functions in the body. These functions include protection, water retention, and vitamin D synthesis.

Protective Functions

The epidermis provides protection to underlying tissues from physical damage, pathogens, and UV light.

Protection from Physical Damage

Most of the physical protection of the epidermis is provided by its tough outer layer, the stratum corneum. Because of this layer, minor scrapes and scratches generally do not cause significant damage to the skin or underlying tissues. Sharp objects and rough surfaces have difficulty penetrating or removing the tough, dead, keratin-filled cells of the stratum corneum. If cells in this layer are pierced or scraped off, they are quickly replaced by new cells moving up to the surface from lower skin layers.

Protection from Pathogens

When pathogens such as viruses and bacteria try to enter the body, it is virtually impossible for them to enter through intact epidermal layers. Generally, pathogens can enter the skin only if the epidermis has been breached, for example by a cut, puncture, or scrape (like the one pictured in Figure 10.3.3). That’s why it is important to clean and cover even a minor wound in the epidermis. This helps ensure that pathogens do not use the wound to enter the body. Protection from pathogens is also provided by conditions at or near the skin surface. These include relatively high acidity (pH of about 5.0), low amounts of water, the presence of antimicrobial substances produced by epidermal cells, and competition with non-pathogenic microorganisms that normally live on the epidermis.

Protection from UV Light

UV light that penetrates the epidermis can damage epidermal cells. In particular, it can cause mutations in DNA that lead to the development of skin cancer, in which epidermal cells grow out of control. UV light can also destroy vitamin B9 (in forms such as folate or folic acid), which is needed for good health and successful reproduction. In a person with light skin, just an hour of exposure to intense sunlight can reduce the body’s vitamin B9 level by 50 per cent.

Melanocytes in the stratum basale of the epidermis contain small organelles called melanosomes, which produce, store, and transport the dark brown pigment melanin. As melanosomes become full of melanin, they move into thin extensions of the melanocytes. From there, the melanosomes are transferred to keratinocytes in the epidermis, where they absorb UV light that strikes the skin. This prevents the light from penetrating deeper into the skin, where it can cause damage. The more melanin there is in the skin, the more UV light can be absorbed.

Water Retention

Skin's ability to hold water and not lose it to the surrounding environment is due mainly to the stratum corneum. Lipids arranged in an organized way among the cells of the stratum corneum form a barrier to water loss from the epidermis. This is critical for maintaining healthy skin and preserving proper water balance in the body.

Although the skin is impermeable to water, it is not impermeable to all substances. Instead, the skin is selectively permeable, allowing certain fat-soluble substances to pass through the epidermis. The selective permeability of the epidermis is both a benefit and a risk.

- Selective permeability allows certain medications to enter the bloodstream through the capillaries in the dermis. This is the basis of medications that are delivered using topical ointments, or patches (see Figure 10.3.4) that are applied to the skin. These include steroid hormones, such as estrogen (for hormone replacement therapy), scopolamine (for motion sickness), nitroglycerin (for heart problems), and nicotine (for people trying to quit smoking).

- Selective permeability of the epidermis also allows certain harmful substances to enter the body through the skin. Examples include the heavy metal lead, as well as many pesticides.

Vitamin D Synthesis

Vitamin D is a nutrient that is needed in the human body for the absorption of calcium from food. Molecules of a lipid compound named 7-dehydrocholesterol are precursors of vitamin D. These molecules are present in the stratum basale and stratum spinosum layers of the epidermis. When UV light strikes the molecules, it changes them to vitamin D3. In the kidneys, vitamin D3 is converted to calcitriol, which is the form of vitamin D that is active in the body.

What Gives Skin Its Colour?

Melanin in the epidermis is the main substance that determines the colour of human skin. It explains most of the variation in skin colour in people around the world. Two other substances also contribute to skin colour, however, especially in light-skinned people: carotene and hemoglobin.

- The pigment carotene is present in the epidermis and gives skin a yellowish tint, especially in skin with low levels of melanin.

- Hemoglobin is a red pigment found in red blood cells. It is visible through skin as a pinkish tint, mainly in skin with low levels of melanin. The pink colour is most visible when capillaries in the underlying dermis dilate, allowing greater blood flow near the surface.

Hear what Bill Nye has to say about the subject of skin colour in the video here.

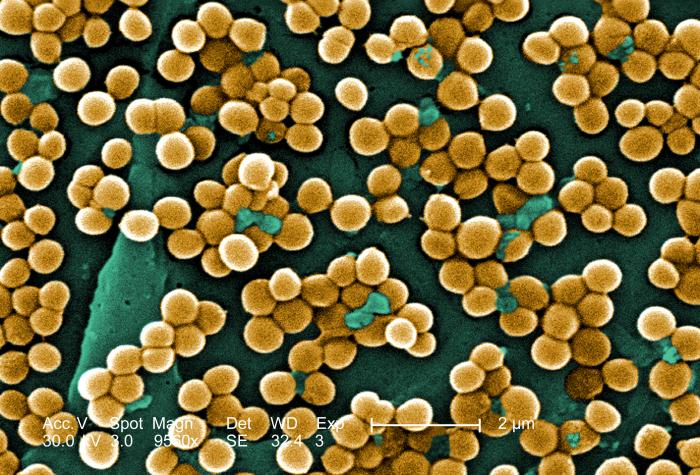

Bacteria on Skin

The surface of the human skin normally provides a home to countless numbers of bacteria. Just one square inch of skin normally has an average of about 50 million bacteria. These generally harmless bacteria represent roughly one thousand bacterial species (including the one in Figure 10.3.5) from 19 different bacterial phyla. Typical variations in the moistness and oiliness of the skin produce a variety of rich and diverse habitats for these microorganisms. For example, the skin in the armpits is warm and moist and often hairy, whereas the skin on the forearms is smooth and dry. These two areas of the human body are as diverse to microorganisms as rainforests and deserts are to larger organisms. The density of bacterial populations on the skin depends largely on the region of the skin and its ecological characteristics. For example, oily surfaces, such as the face, may contain over 500 million bacteria per square inch. Despite the huge number of individual microorganisms living on the skin, their total volume is only about the size of a pea.

In general, the normal microorganisms living on the skin keep one another in check, and thereby play an important role in keeping the skin healthy. If the balance of microorganisms is disturbed, however, there may be an overgrowth of certain species, and this may result in an infection. For example, when a patient is prescribed antibiotics, it may kill off normal bacteria and allow an overgrowth of single-celled yeast. Even if skin is disinfected, no amount of cleaning can remove all of the microorganisms it contains. Disinfected areas are also quickly recolonized by bacteria residing in deeper areas (such as hair follicles) and in adjacent areas of the skin.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Because of the negative health effects of excessive UV light exposure, it is important to know the facts about protecting the skin from UV light.

Myth |

Reality |

| "Sunblock and sunscreen are just different names for the same type of product. They both work the same way and are equally effective." | Sunscreens and sunblocks are different types of products that protect the skin from UV light in different ways. They are not equally effective. Sunblocks are opaque, so they do not let light pass through. They prevent most of the rays of UV light from penetrating to the skin surface. Sunblocks are generally stronger and more effective than sunscreens. Sunblocks also do not need to be reapplied as often as sunscreens. Sunscreens, in contrast, are transparent once they are applied the skin. Although they can prevent most UV light from penetrating the skin when first applied, the active ingredients in sunscreens tend to break down when exposed to UV light. Sunscreens, therefore, must be reapplied often to remain effective. |

| "The skin needs to be protected from UV light only on sunny days. When the sky is cloudy, UV light cannot penetrate to the ground and harm the skin." | Even on cloudy days, a significant amount of UV radiation penetrates the atmosphere to strike Earth’s surface. Therefore, using sunscreens or sunblocks to protect exposed skin is important even when there are clouds in the sky. |

| "People who have dark skin, such as African Americans, do not need to worry about skin damage from UV light." | No matter what colour skin you have, your skin can be damaged by too much exposure to UV light. Therefore, even dark-skinned people should use sunscreens or sunblocks to protect exposed skin from UV light. |

| "Sunscreens with an SPF (sun protection factor) of 15 are adequate to fully protect the skin from UV light." | Most dermatologists recommend using sunscreens with an SPF of at least 35 for adequate protection from UV light. They also recommend applying sunscreens at least 20 minutes before sun exposure and reapplying sunscreens often, especially if you are sweating or spending time in the water. |

| "Using tanning beds is safer than tanning outside in natural sunlight." | The light in tanning beds is UV light, and it can do the same damage to the skin as the natural UV light in sunlight. This is evidenced by the fact that people who regularly use tanning beds have significantly higher rates of skin cancer than people who do not. It is also the reason that the use of tanning beds is prohibited in many places in people who are under the age of 18, just as youth are prohibited from using harmful substances, such as tobacco and alcohol. |

10.3 Summary

- The epidermis is the outer of the two main layers of the skin. It is very thin, but has a complex structure.

- Cell types in the epidermis include keratinocytes that produce keratin and make up 90 per cent of epidermal cells, melanocytes that produce melanin, Langerhans cells that fight pathogens in the skin, and Merkel cells that respond to light touch.

- The epidermis in most parts of the body consists of four distinct layers. A fifth layer occurs only in the epidermis of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.

- The innermost layer of the epidermis is the stratum basale, which contains stem cells that divide to form new keratinocytes. The next layer is the stratum spinosum, which is the thickest layer and contains Langerhans cells and spiny keratinocytes. This is followed by the stratum granulosum, in which keratinocytes are filling with keratin and starting to die. The stratum lucidum is next, but only on the palms and soles. It consists of translucent dead keratinocytes. The outermost layer is the stratum corneum, which consists of flat, dead, tightly packed keratinocytes that form a tough, waterproof barrier for the rest of the epidermis.

- Functions of the epidermis include protecting underlying tissues from physical damage and pathogens. Melanin in the epidermis absorbs and protects underlying tissues from UV light. The epidermis also prevents loss of water from the body and synthesizes vitamin D.

- Melanin is the main pigment that determines the colour of human skin. The pigments carotene and hemoglobin, however, also contribute to skin colour, especially in skin with low levels of melanin.

- The surface of healthy skin normally is covered by vast numbers of bacteria representing about one thousand species from 19 phyla. Different areas of the body provide diverse habitats for skin microorganisms. Usually, microorganisms on the skin keep each other in check unless their balance is disturbed.

10.3 Review Questions

- What is the epidermis?

- Identify the types of cells in the epidermis.

- Describe the layers of the epidermis.

-

- State one function of each of the four epidermal layers found all over the body.

- Explain three ways the epidermis protects the body.

- What makes the skin waterproof?

- Why is the selective permeability of the epidermis both a benefit and a risk?

- How is vitamin D synthesized in the epidermis?

- Identify three pigments that impart colour to skin.

- Describe bacteria that normally reside on the skin, and explain why they do not usually cause infections.

- Explain why the keratinocytes at the surface of the epidermis are dead, while keratinocytes located deeper in the epidermis are still alive.

- Which layer of the epidermis contains keratinocytes that have begun to die?

-

- Explain why our skin is not permanently damaged if we rub off some of the surface layer by using a rough washcloth.

10.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=27lMmdmy-b8

Jonathan Eisen: Meet your microbes, TED, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9AcQXnOscQ8

Why Do We Blush?, SciShow, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_r4c2NT4naQ

The science of skin colour - Angela Koine Flynn, TED-Ed, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 10.3.1

Sunburn by QuinnHK at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 10.3.2

Blausen_0353_Epidermis by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 10.3.3

Isaac's scraped knee close-up by Alpha on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 10.3.4

Nicoderm by RegBarc on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license. (No machine-readable author provided for original.)

Figure 10.3.5

Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, MRSA by Microbe World on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

References

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Jeff Bone 'n' Pookie. (2020, July 19). Bill Nye the science guy explains we have different skin color. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOkj5jgC4sM&feature=youtu.be

SciShow. (2014, July 15). Why do we blush? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9AcQXnOscQ8

TED. (2015, July 17). Jonathan Eisen: Meet your microbes. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=27lMmdmy-b8

TED-Ed. (2016, February 16). The science of skin color - Angela Koine Flynn. YouTube. https://youtu.be/_r4c2NT4naQ

As per caption.

A type of immune cell that is one of the first cell types to travel to the site of an infection. Neutrophils help fight infection by ingesting microorganisms and releasing enzymes that kill the microorganisms. A neutrophil is a type of white blood cell, a type of granulocyte, and a type of phagocyte.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Steady as She Goes

This device (Figure 7.8.1) looks simple, but it controls a complex system that keeps a home at a steady temperature — it's a thermostat. The device shows the current temperature in the room, and also allows the occupant to set the thermostat to the desired temperature. A thermostat is a commonly cited model of how living systems — including the human body— maintain a steady state called homeostasis.

What Is Homeostasis?

Homeostasis is the condition in which a system (such as the human body) is maintained in a more or less steady state. It is the job of cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems throughout the body to maintain many different variables within narrow ranges compatible with life. Keeping a stable internal environment requires continually monitoring the internal environment and constantly making adjustments to keep things in balance.

Set Point and Normal Range

For any given variable, such as body temperature or blood glucose level, there is a particular set point that is the physiological optimum value. The set point for human body temperature, for example, is about 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). As the body works to maintain homeostasis for temperature or any other internal variable, the value typically fluctuates around the set point. Such fluctuations are normal, as long as they do not become too extreme. The spread of values within which such fluctuations are considered insignificant is called the normal range. In the case of body temperature, for example, the normal range for an adult is about 36.5 to 37.5 degrees C (97.7 to 99.5 degrees F).

A good analogy for set point, normal range, and maintenance of homeostasis is driving. When you are driving a vehicle on the road, you are supposed to drive in the centre of your lane — this is analogous to the set point. Sometimes, you are not driving in the exact centre of the lane, but you are still within your lines, so you are in the equivalent of the normal range. However, if you were to get too close to the centre line or the shoulder of the road, you would take action to correct your position. You'd move left if you were too close to the shoulder, or right if too close to the centre line — which is analogous to our next concept, negative feedback to maintain homeostasis.

Maintaining Homeostasis

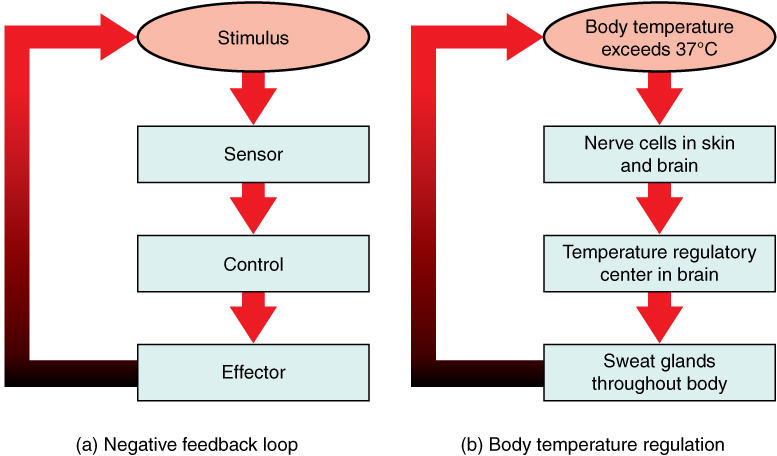

Homeostasis is normally maintained in the human body by an extremely complex balancing act. Regardless of the variable being kept within its normal range, maintaining homeostasis requires at least four interacting components: stimulus, sensor, control centre, and effector.

- The stimulus is provided by the variable being regulated. Generally, the stimulus indicates that the value of the variable has moved away from the set point or has left the normal range.

- The sensor monitors the values of the variable and sends data on it to the control centre.

- The control centre matches the data with normal values. If the value is not at the set point or is outside the normal range, the control centre sends a signal to the effector.

- The effector is an organ, gland, muscle, or other structure that acts on the signal from the control centre to move the variable back toward the set point.

Each of these components is illustrated in Figure 7.8.2. The diagram on the left is a general model showing how the components interact to maintain homeostasis. The diagram on the right shows the example of body temperature. From the diagrams, you can see that maintaining homeostasis involves feedback, which is data that feeds back to control a response. Feedback may be negative (as in the example below) or positive. All the feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis use negative feedback. Biological examples of positive feedback are much less common.

Negative Feedback

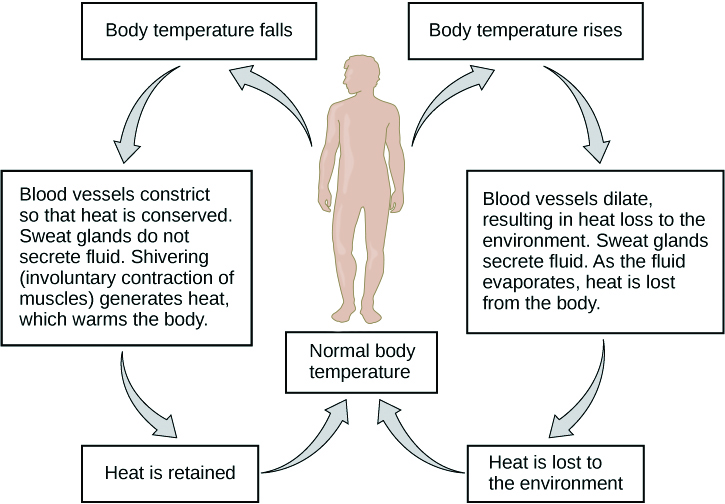

In a negative feedback loop, feedback serves to reduce an excessive response and keep a variable within the normal range. Two processes controlled by negative feedback are body temperature regulation and control of blood glucose.

Body Temperature

Body temperature regulation involves negative feedback, whether it lowers the temperature or raises it, as shown in Figure 7.8.3 and explained in the text that follows.

Cooling Down

The human body’s temperature regulatory centre is the hypothalamus in the brain. When the hypothalamus receives data from sensors in the skin and brain that body temperature is higher than the set point, it sets into motion the following responses:

- Blood vessels in the skin dilate (vasodilation) to allow more blood from the warm body core to flow close to the surface of the body, so heat can be radiated into the environment.

- As blood flow to the skin increases, sweat glands in the skin are activated to increase their output of sweat (diaphoresis). When the sweat evaporates from the skin surface into the surrounding air, it takes heat with it.

- Breathing becomes deeper, and the person may breathe through the mouth instead of the nasal passages. This increases heat loss from the lungs.

Heating Up

When the brain’s temperature regulatory centre receives data that body temperature is lower than the set point, it sets into motion the following responses:

- Blood vessels in the skin contract (vasoconstriction) to prevent blood from flowing close to the surface of the body, which reduces heat loss from the surface.

- As temperature falls lower, random signals to skeletal muscles are triggered, causing them to contract. This causes shivering, which generates a small amount of heat.

- The thyroid gland may be stimulated by the brain (via the pituitary gland) to secrete more thyroid hormone. This hormone increases metabolic activity and heat production in cells throughout the body.

- The adrenal glands may also be stimulated to secrete the hormone adrenaline. This hormone causes the breakdown of glycogen (the carbohydrate used for energy storage in animals) to glucose, which can be used as an energy source. This catabolic chemical process is exothermic, or heat producing.

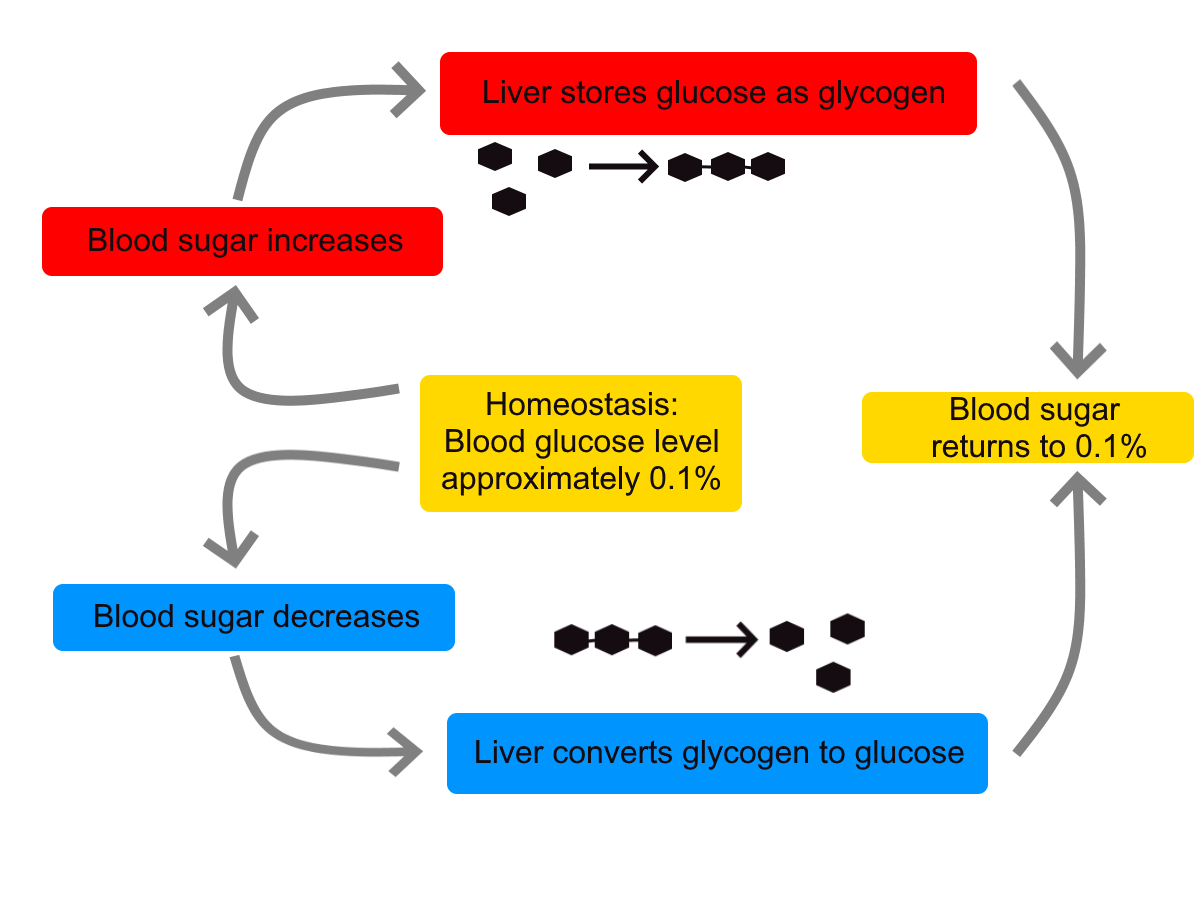

Blood Glucose

In controlling the blood glucose level, certain endocrine cells in the pancreas (called alpha and beta cells) detect the level of glucose in the blood. They then respond appropriately to keep the level of blood glucose within the normal range.

- If the blood glucose level rises above the normal range, pancreatic beta cells release the hormone insulin into the bloodstream. Insulin signals cells to take up the excess glucose from the blood until the level of blood glucose decreases to the normal range.

- If the blood glucose level falls below the normal range, pancreatic alpha cells release the hormone glucagon into the bloodstream. Glucagon signals cells to break down stored glycogen to glucose and release the glucose into the blood until the level of blood glucose increases to the normal range.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iz0Q9nTZCw4

Homeostasis and Negative/Positive Feedback, Amoeba Sisters, 2017.

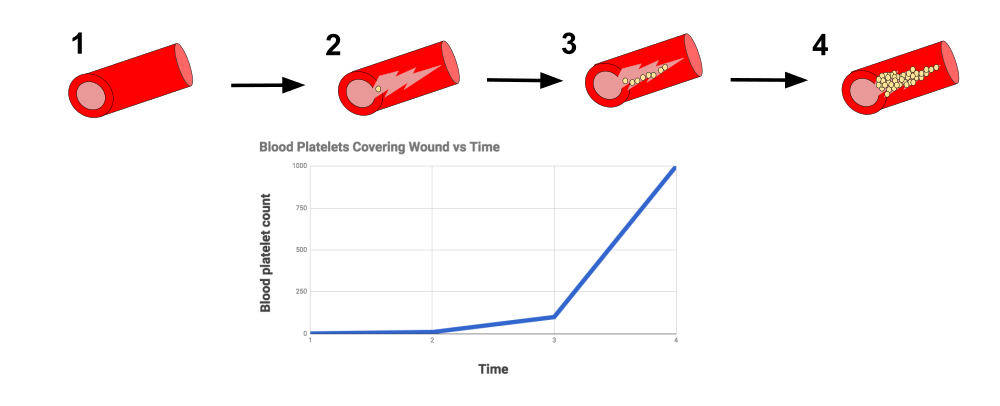

Positive Feedback

In a positive feedback loop, feedback serves to intensify a response until an end point is reached. Examples of processes controlled by positive feedback in the human body include blood clotting and childbirth.

Blood Clotting

When a wound causes bleeding, the body responds with a positive feedback loop to clot the blood and stop blood loss. Substances released by the injured blood vessel wall begin the process of blood clotting. Platelets in the blood start to cling to the injured site and release chemicals that attract additional platelets. As the platelets continue to amass, more of the chemicals are released and more platelets are attracted to the site of the clot. The positive feedback accelerates the process of clotting until the clot is large enough to stop the bleeding.

Childbirth

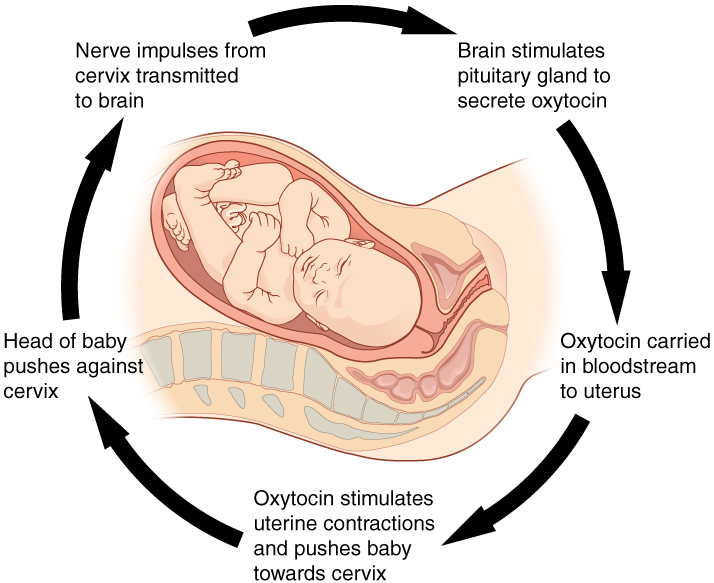

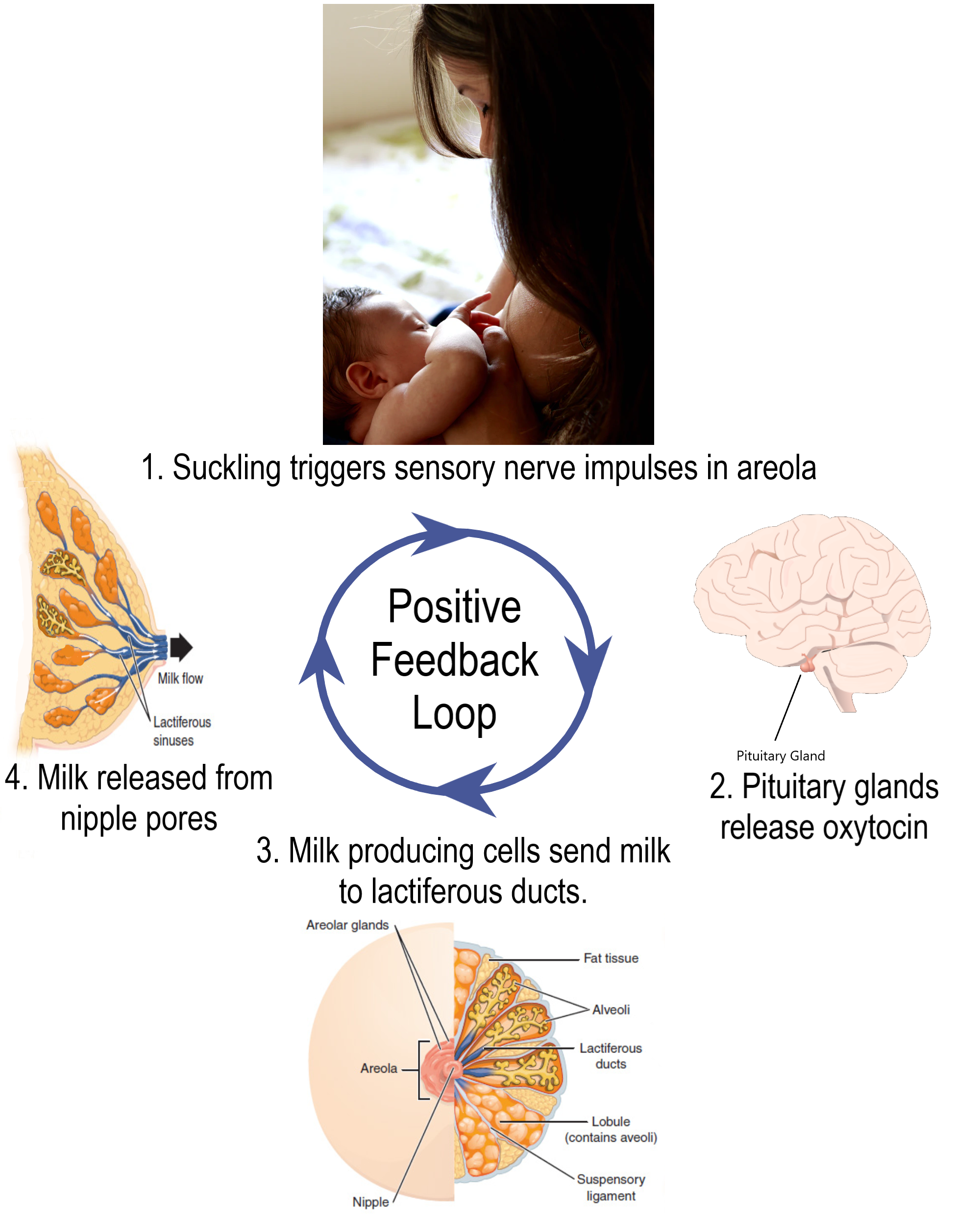

Figure 7.8.6 shows the positive feedback loop that controls childbirth. The process normally begins when the head of the infant pushes against the cervix. This stimulates nerve impulses, which travel from the cervix to the hypothalamus in the brain. In response, the hypothalamus sends the hormone oxytocin to the pituitary gland, which secretes it into the bloodstream so it can be carried to the uterus. Oxytocin stimulates uterine contractions, which push the baby harder against the cervix. In response, the cervix starts to dilate in preparation for the passage of the baby. This cycle of positive feedback continues, with increasing levels of oxytocin, stronger uterine contractions, and wider dilation of the cervix until the baby is pushed through the birth canal and out of the body. At that point, the cervix is no longer stimulated to send nerve impulses to the brain, and the entire process stops.

Normal childbirth is driven by a positive feedback loop. Positive feedback causes an increasing deviation from the normal state to a fixed end point, rather than a return to a normal set point as in homeostasis.

When Homeostasis Fails

Homeostatic mechanisms work continuously to maintain stable conditions in the human body. Sometimes, however, the mechanisms fail. When they do, homeostatic imbalance may result, in which cells may not get everything they need or toxic wastes may accumulate in the body. If homeostasis is not restored, the imbalance may lead to disease — or even death. Diabetes is an example of a disease caused by homeostatic imbalance. In the case of diabetes, blood glucose levels are no longer regulated and may be dangerously high. Medical intervention can help restore homeostasis and possibly prevent permanent damage to the organism.

Normal aging may bring about a reduction in the efficiency of the body’s control systems, which makes the body more susceptible to disease. Older people, for example, may have a harder time regulating their body temperature. This is one reason they are more likely than younger people to develop serious heat-induced illnesses, such as heat stroke.

Feature: My Human Body

Diabetes is diagnosed in people who have abnormally high levels of blood glucose after fasting for at least 12 hours. A fasting level of blood glucose below 100 is normal. A level between 100 and 125 places you in the pre-diabetes category, and a level higher than 125 results in a diagnosis of diabetes.

Of the two types of diabetes, type 2 diabetes is the most common, accounting for about 90 per cent of all cases of diabetes in the United States. Type 2 diabetes typically starts after the age of 40. However, because of the dramatic increase in recent decades in obesity in younger people, the age at which type 2 diabetes is diagnosed has fallen. Even children are now being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Today, about 3 million Canadians (8.1% of total population) are living with diabetes.