17.2 Introduction to the Immune System

Worm Attack!

Does the organism in Figure 17.2.1 look like a space alien? A scary creature from a nightmare? In fact, it’s a 1-cm long worm in the genus Schistosoma. It may invade and take up residence in the human body, causing a very serious illness known as schistosomiasis. The worm gains access to the human body while it is in a microscopic life stage. It enters through a hair follicle when the skin comes into contact with contaminated water. The worm then grows and matures inside the human organism, causing disease.

Host vs. Pathogen

The Schistosoma worm has a parasitic relationship with humans. In this type of relationship, one organism, called the parasite, lives on or in another organism, called the host. The parasite always benefits from the relationship, and the host is always harmed. The human host of the Schistosoma worm is clearly harmed by the parasite when it invades the host’s tissues. The urinary tract or intestines may be infected, and signs and symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, or blood in the urine. Those who have been infected for a long time may experience liver damage, kidney failure, infertility, or bladder cancer. In children, Schistosoma infection may cause poor growth and difficulty learning.

Like the Schistosoma worm, many other organisms can make us sick if they manage to enter our body. Any such agent that can cause disease is called a pathogen. Most pathogens are microorganisms, although some — such as the Schistosoma worm — are much larger. In addition to worms, common types of pathogens of human hosts include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and single-celled organisms called protists. You can see examples of each of these types of pathogens in Table 17.1.1. Fortunately for us, our immune system is able to keep most potential pathogens out of the body, or quickly destroy them if they do manage to get in. When you read this chapter, you’ll learn how your immune system usually keeps you safe from harm — including from scary creatures like the Schistosoma worm!

| Type of Pathogen | Description | Disease Caused | |

|---|---|---|---|

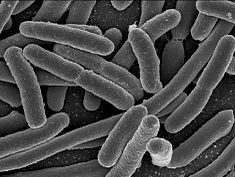

| Bacteria:

Example shown: Escherichia coli |

|

Single celled organisms without a nucleus | Strep throat, staph infections, tuberculosis, food poisoning, tetanus, pneumonia, syphillis |

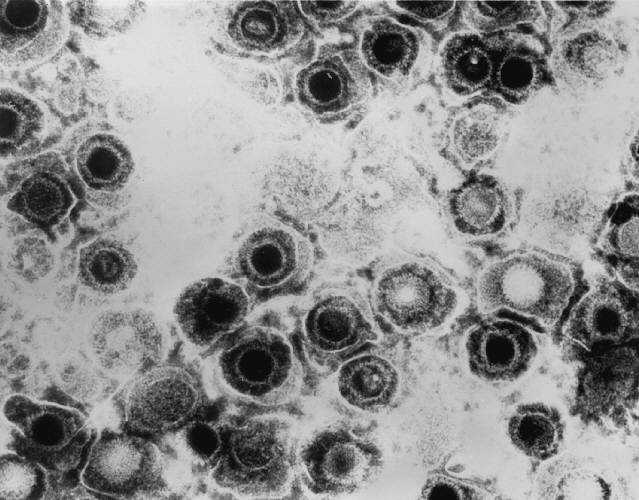

| Viruses:

Example shown: Herpes simplex |

|

Non-living particles that reproduce by taking over living cells | Common cold, flu, genital herpes, cold sores, measles, AIDS, genital warts, chicken pox, small pox |

| Fungi:

Example shown: Death cap mushroom |

|

Simple organisms, including mushrooms and yeast, that grow as single cells or thread-like filaments | Ringworm, athletes foot, tineas, candidias, histoplasmomis, mushroom poisoning |

| Protozoa:

Example shown: Giardia lamblia |

|

Single celled organisms with a nucleus | Malaria, “traveller’s diarrhea”, giardiasis, typano somiasis (“sleeping sickness”) |

What is the Immune System?

The immune system is a host defense system. It comprises many biological structures —ranging from individual leukocytes to entire organs — as well as many complex biological processes. The function of the immune system is to protect the host from pathogens and other causes of disease, such as tumor (cancer) cells. To function properly, the immune system must be able to detect a wide variety of pathogens. It also must be able to distinguish the cells of pathogens from the host’s own cells, and also to distinguish cancerous or damaged host cells from healthy cells. In humans and most other vertebrates, the immune system consists of layered defenses that have increasing specificity for particular pathogens or tumor cells. The layered defenses of the human immune system are usually classified into two subsystems, called the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system.

Innate Immune System

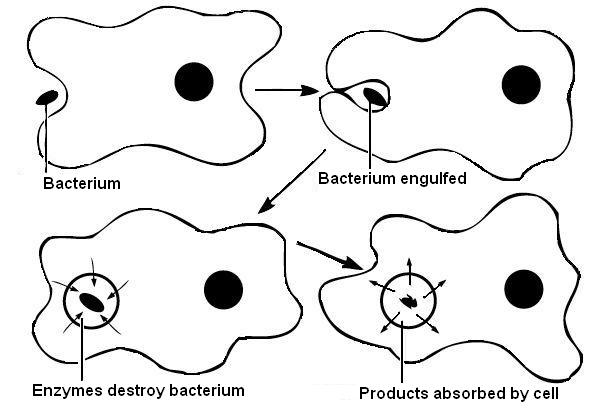

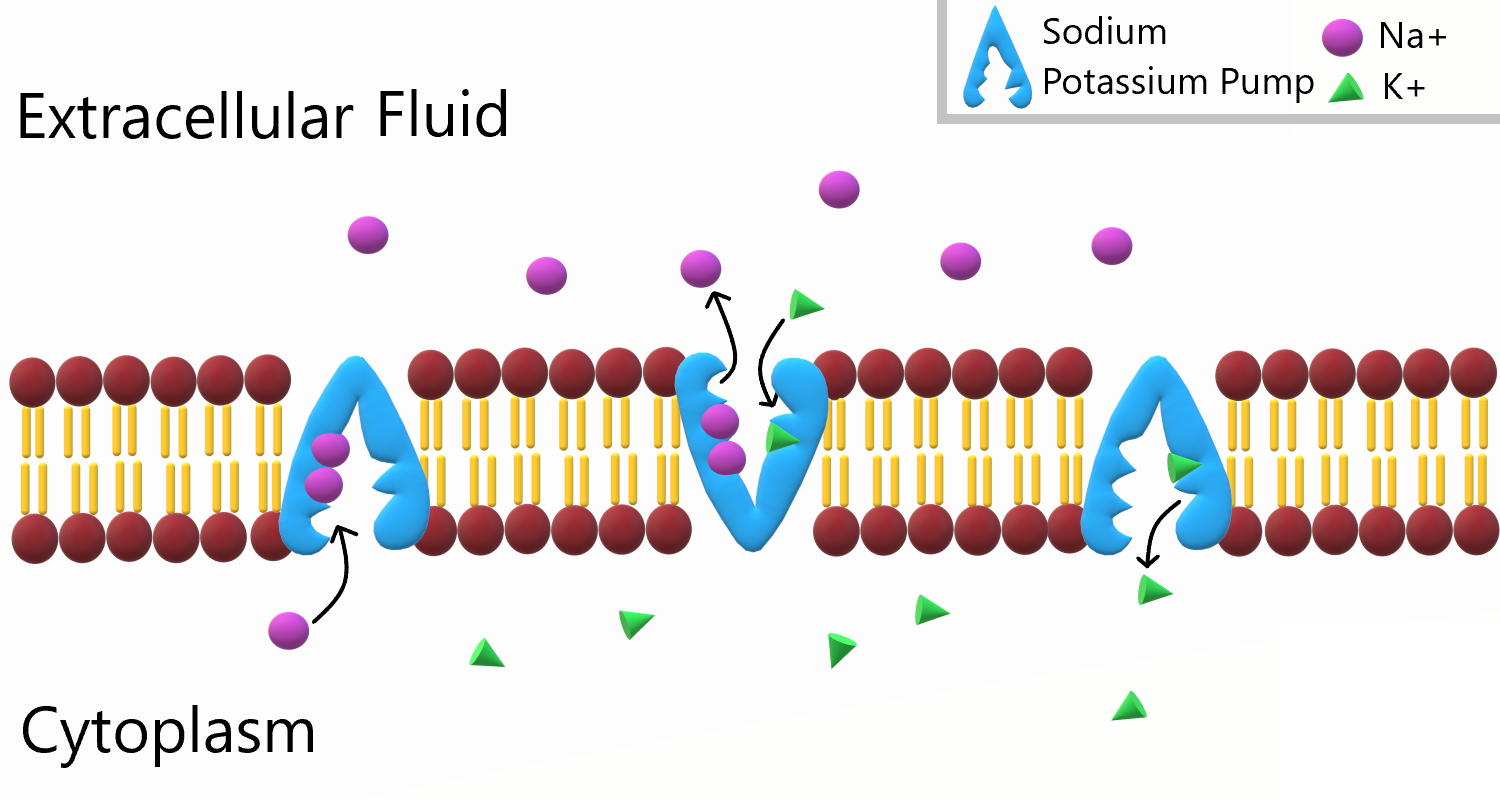

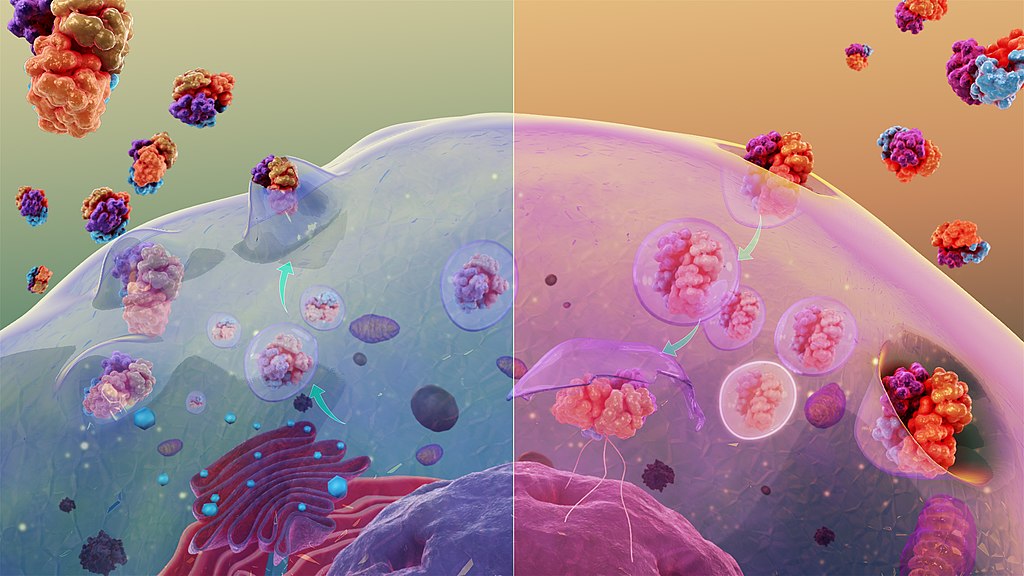

The innate immune system (sometimes referred to as “non-specific defense”) provides very quick, but non-specific responses to pathogens. It responds the same way regardless of the type of pathogen that is attacking the host. It includes barriers — such as the skin and mucous membranes — that normally keep pathogens out of the body. It also includes general responses to pathogens that manage to breach these barriers, including chemicals and cells that attack the pathogens inside the human host. Certain leukocytes (white blood cells), for example, engulf and destroy pathogens they encounter in the process called phagocytosis, which is illustrated in Figure 17.2.2. Exposure to pathogens leads to an immediate maximal response from the innate immune system.

Watch the video below, “Neutrophil Phagocytosis – White Blood Cells Eats Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteria” by ImmiflexImmuneSystem, to see phagocytosis in action.

Neutrophil Phagocytosis – White Blood Cell Eats Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteria, ImmiflexImmuneSystem, 2013.

Adaptive Immune System

The adaptive immune system is activated if pathogens successfully enter the body and manage to evade the general defenses of the innate immune system. An adaptive response is specific to the particular type of pathogen that has invaded the body, or to cancerous cells. It takes longer to launch a specific attack, but once it is underway, its specificity makes it very effective. An adaptive response also usually leads to immunity. This is a state of resistance to a specific pathogen, due to the adaptive immune system’s ability to “remember” the pathogen and immediately mount a strong attack tailored to that particular pathogen if it invades again in the future.

Self vs. Non-Self

Both innate and adaptive immune responses depend on the immune system’s ability to distinguish between self- and non-self molecules. Self molecules are those components of an organism’s body that can be distinguished from foreign substances by the immune system. Virtually all body cells have surface proteins that are part of a complex called major histocompatibility complex (MHC). These proteins are one way the immune system recognizes body cells as self. Non-self proteins, in contrast, are recognized as foreign, because they are different from self proteins.

Antigens and Antibodies

Many non-self molecules comprise a class of compounds called antigens. Antigens, which are usually proteins, bind to specific receptors on immune system cells and elicit an adaptive immune response. Some adaptive immune system cells (B cells) respond to foreign antigens by producing antibodies. An antibody is a molecule that precisely matches and binds to a specific antigen. This may target the antigen (and the pathogen displaying it) for destruction by other immune cells.

Antigens on the surface of pathogens are how the adaptive immune system recognizes specific pathogens. Antigen specificity allows for the generation of responses tailored to the specific pathogen. It is also how the adaptive immune system ”remembers” the same pathogen in the future.

Immune Surveillance

Another important role of the immune system is to identify and eliminate tumor cells. This is called immune surveillance. The transformed cells of tumors express antigens that are not found on normal body cells. The main response of the immune system to tumor cells is to destroy them. This is carried out primarily by aptly-named killer T cells of the adaptive immune system.

Lymphatic System

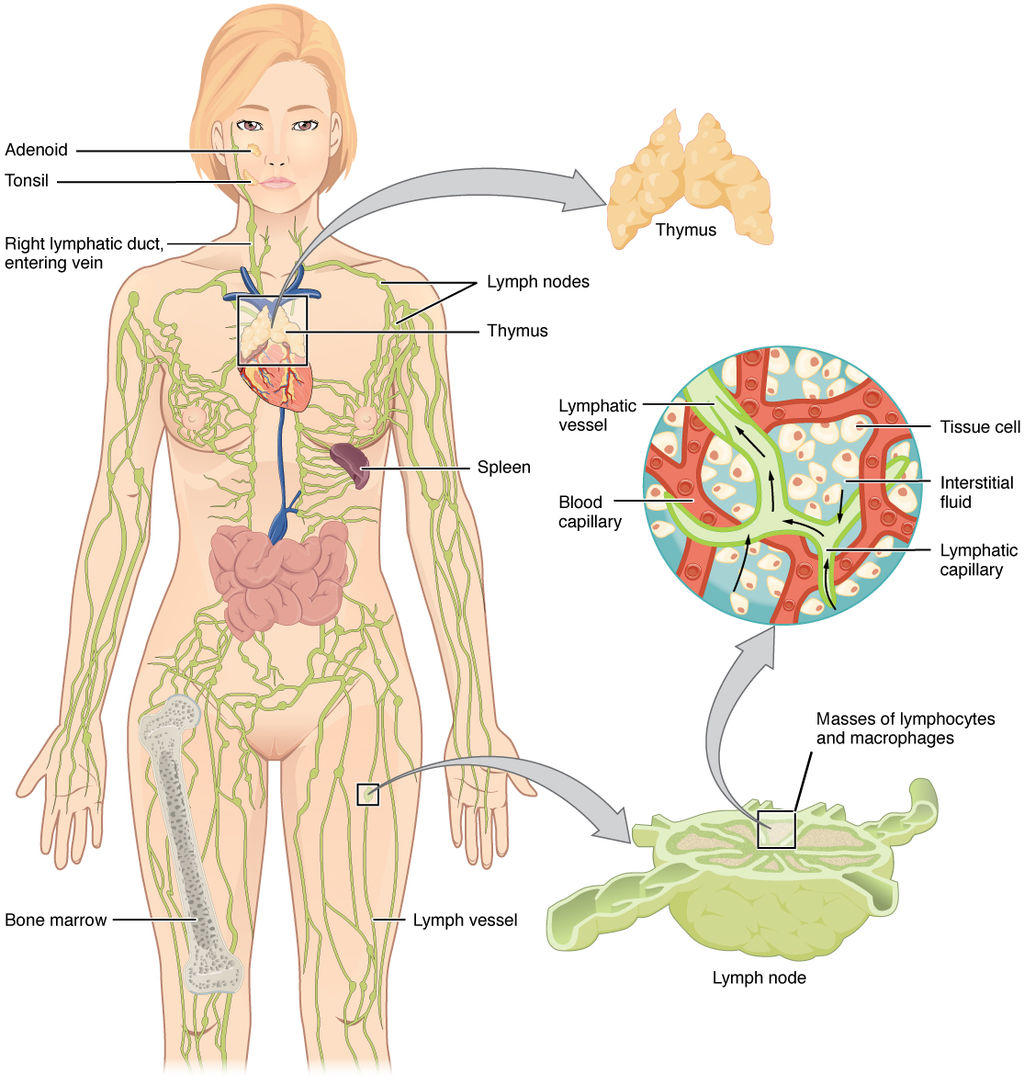

The lymphatic system is a human organ system that is a vital part of the adaptive immune system. It is also part of the cardiovascular system and plays a major role in the digestive system (see section 17.3 Lymphatic System). The major structures of the lymphatic system are shown in Figure 17.2.3 .

The lymphatic system consists of several lymphatic organs and a body-wide network of lymphatic vessels that transport the fluid called lymph. Lymph is essentially blood plasma that has leaked from capillaries into tissue spaces. It includes many leukocytes, especially lymphocytes, which are the major cells of the lymphatic system. Like other leukocytes, lymphocytes defend the body. There are several different types of lymphocytes that fight pathogens or cancer cells as part of the adaptive immune system.

Major lymphatic organs include the thymus and bone marrow. Their function is to form and/or mature lymphocytes. Other lymphatic organs include the spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes, which are small clumps of lymphoid tissue clustered along lymphatic vessels. These other lymphatic organs harbor mature lymphocytes and filter lymph. They are sites where pathogens collect, and adaptive immune responses generally begin.

Neuroimmune System vs. Peripheral Immune System

The brain and spinal cord are normally protected from pathogens in the blood by the selectively permeable blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers. These barriers are part of the neuroimmune system. The neuroimmune system has traditionally been considered distinct from the rest of the immune system, which is called the peripheral immune system — although that view may be changing. Unlike the peripheral system, in which leukocytes are the main cells, the main cells of the neuroimmune system are thought to be nervous system cells called neuroglia. These cells can recognize and respond to pathogens, debris, and other potential dangers. Types of neuroglia involved in neuroimmune responses include microglial cells and astrocytes.

- Microglial cells are among the most prominent types of neuroglia in the brain. One of their main functions is to phagocytize cellular debris that remains when neurons die. Microglial cells also “prune” obsolete synapses between neurons.

- Astrocytes are neuroglia that have a different immune function. They allow certain immune cells from the peripheral immune system to cross into the brain via the blood-brain barrier to target both pathogens and damaged nervous tissue.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

“They’ll have to rewrite the textbooks!”

That sort of response to a scientific discovery is sure to attract media attention, and it did. It’s what Kevin Lee, a neuroscientist at the University of Virginia, said in 2016 when his colleagues told him they had discovered human anatomical structures that had never before been detected. The structures were tiny lymphatic vessels in the meningeal layers surrounding the brain.

How these lymphatic vessels could have gone unnoticed when all human body systems have been studied so completely is amazing in its own right. The suggested implications of the discovery are equally amazing:

- The presence of these lymphatic vessels means that the brain is directly connected to the peripheral immune system, presumably allowing a close association between the human brain and human pathogens. This suggests an entirely new avenue by which humans and their pathogens may have influenced each other’s evolution. The researchers speculate that our pathogens even may have influenced the evolution of our social behaviors.

- The researchers think there will also be many medical applications of their discovery. For example, the newly discovered lymphatic vessels may play a major role in neurological diseases that have an immune component, such as multiple sclerosis. The discovery might also affect how conditions such as autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia are treated.

17.2 Summary

- Any agent that can cause disease is called a pathogen. Most human pathogens are microorganisms, such as bacteria and viruses. The immune system is the body system that defends the human host from pathogens and cancerous cells.

- The innate immune system is a subset of the immune system that provides very quick, but non-specific responses to pathogens. It includes multiple types of barriers to pathogens, leukocytes that phagocytize pathogens, and several other general responses.

- The adaptive immune system is a subset of the immune system that provides specific responses tailored to particular pathogens. It takes longer to put into effect, but it may lead to immunity to the pathogens.

- Both innate and adaptive immune responses depend on the immune system’s ability to distinguish between self and non-self molecules. Most body cells have major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins that identify them as self. Pathogens and tumor cells have non-self antigens that the immune system recognizes as foreign.

- Antigens are proteins that bind to specific receptors on immune system cells and elicit an adaptive immune response. Generally, they are non-self molecules on pathogens or infected cells. Some immune cells (B cells) respond to foreign antigens by producing antibodies that bind with antigens and target pathogens for destruction.

- Tumor surveillance is an important role of the immune system. Killer T cells of the adaptive immune system find and destroy tumor cells, which they can identify from their abnormal antigens.

- The lymphatic system is a human organ system vital to the adaptive immune system. It consists of several organs and a system of vessels that transport lymph. The main immune function of the lymphatic system is to produce, mature, and circulate lymphocytes, which are the main cells in the adaptive immune system.

- The neuroimmune system that protects the central nervous system is thought to be distinct from the peripheral immune system that protects the rest of the human body. The blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers are one type of protection for the neuroimmune system. Neuroglia also play role in this system, for example, by carrying out phagocytosis.

17.2 Review Questions

-

- What is a pathogen?

- State the purpose of the immune system.

- Compare and contrast the innate and adaptive immune systems.

- Explain how the immune system distinguishes self molecules from non-self molecules.

- What are antigens?

- Define tumor surveillance.

- Briefly describe the lymphatic system and its role in immune function.

- Identify the neuroimmune system.

- What does it mean that the immune system is not just composed of organs?

- Why is the immune system considered “layered?”

17.2 Explore More

The Antibiotic Apocalypse Explained, Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell, 2016.

Overview of the Immune System, Handwritten Tutorials, 2011.

The surprising reason you feel awful when you’re sick – Marco A. Sotomayor, TED-Ed, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 17.1.1

Schistosome Parasite by Bruce Wetzel and Harry Schaefer (Photographers) from the National Cancer Institute, Visuals online is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 17.1.2

Phagocytosis by Rlawson at en.wikibooks on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license. (Transferred from en.wikibooks to Commons by User:Adrignola.)

Figure 17.1.3

2201_Anatomy_of_the_Lymphatic_System by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Table 17.1.1

- EscherichiaColi NIAID [photo] by Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

- Herpes simplex virus TEM B82-0474 lores by Dr. Erskine Palmer/ CDC Public Health Image Library (PHIL) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

- Red death cap mushroom by Rosendahl on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (Transferred from Pixnio by Fæ.)

- Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of Giardia lamblia by Janice Haney Carr/ CDC, Public Health Image Library (PHIL) Photo ID# 8698 is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Barney, J. (2016, March 21). They’ll have to rewrite the textbooks [online article]. Illimitable – Discovery. UVA Today/ University of Virginia. https://news.virginia.edu/illimitable/discovery/theyll-have-rewrite-textbooks

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 21.2 Anatomy of the lymphatic system [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 21.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems

Handwritten Tutorials. (2011, October 25). Overview of the immune system. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nw27_jMWw10&feature=youtu.be

ImmiflexImmuneSystem. (2013). Neutrophil phagocytosis – White blood cell eats staphylococcus aureus bacteria. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_mXDvZQ6dU

Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell. (2016, March 16). The antibiotic apocalypse explained. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZbcwi7SfZE&feature=youtu.be

Louveau, A., Smirnov, I., Keyes, T. J., Eccles, J. D., Rouhani, S. J., Peske, J. D., Derecki, N. C., Castle, D., Mandell, J. W., Lee, K. S., Harris, T. H., & Kipnis, J. (2015). Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature, 523(7560), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14432

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Autism spectrum disorder [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352928

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Multiple sclerosis [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/multiple-sclerosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350269

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Schizophrenia [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/schizophrenia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354443

TED-Ed. (2016, April 19). The surprising reason you feel awful when you’re sick – Marco A. Sotomayor. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVdY9KXF_Sg&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Hormonal Havoc

Eighteen-year-old Gabrielle checks her calendar. It has been 42 days since her last menstrual period, which is two weeks longer than the length of the average woman’s menstrual cycle. Although many women would suspect pregnancy if their period was late, Gabrielle has not been sexually active. She is not even sure she is “late,” because her period has never been regular. Ever since her first period when she was 13 years old, her cycle lengths have varied greatly, and there are months where she does not get a period at all. Her mother told her that a girl’s period is often irregular when it first starts, but five years later, Gabrielle’s still has not become regular. She decides to go to the student health center on her college campus to get it checked out.

The doctor asks her about the timing of her menstrual periods and performs a pelvic exam. She also notices that Gabrielle is overweight, has acne, and excess facial hair. As she explains to Gabrielle, while these physical characteristics can be perfectly normal, in combination with an irregular period, they can be signs of a disorder of the endocrine — or hormonal — system called polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

In order to check for PCOS, the doctor refers Gabrielle for a pelvic ultrasound and sends her to the lab to get blood work done. When her lab results come back, Gabrielle learns that her levels of androgens (a group of hormones) are high, and so is her blood glucose (sugar). The ultrasound showed that she has multiple fluid-filled sacs (known as cysts) in her ovaries. Based on Gabrielle’s symptoms and test results, the doctor tells her that she does indeed have PCOS.

PCOS is common in young women. It is estimated that 6-10% women of childbearing age have PCOS — as many as 1.4 million women in in Canada. You may know someone with PCOS, or you may have it yourself.

Read the rest of this chapter to learn about the glands and hormones of the endocrine system, their functions, how they are regulated, and the disorders — such as PCOS — that can arise when hormones are not regulated properly. At the end of the chapter, you will learn more about PCOS, its possible long-term consequences (including fertility problems and diabetes), and how these negative outcomes can sometimes be prevented with lifestyle changes and medications.

Chapter Overview: Endocrine System

In this chapter, you will learn about the endocrine system, a system of glands that secrete hormones that regulate many of the body’s functions. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The glands that make up the endocrine system, and how hormones act as chemical messengers in the body.

- The general types of endocrine system disorders.

- The types of endocrine hormones — including steroid hormones (such as sex hormones) and non-steroid hormones (such as insulin) — and how they affect the functions of their target cells by binding to different types of receptor proteins.

- How the levels of hormones are regulated mostly through negative, but sometimes through positive, feedback loops.

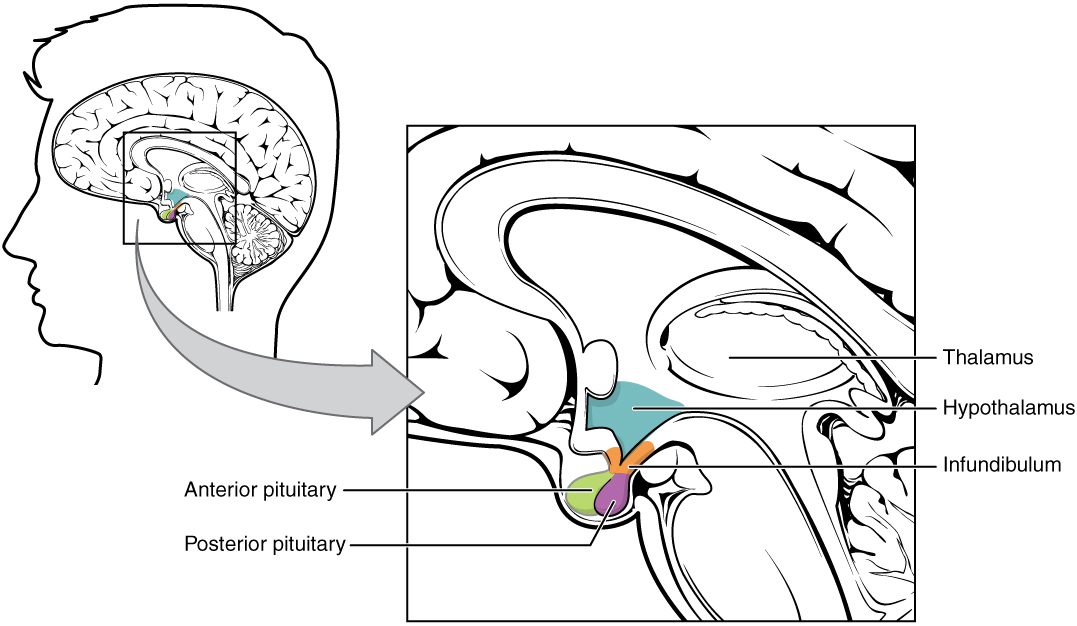

- The master gland of the endocrine system, the pituitary gland, which controls other parts of the endocrine system through the hormones that it secretes, as well as how the pituitary itself is regulated by hormones secreted from the hypothalamus of the brain.

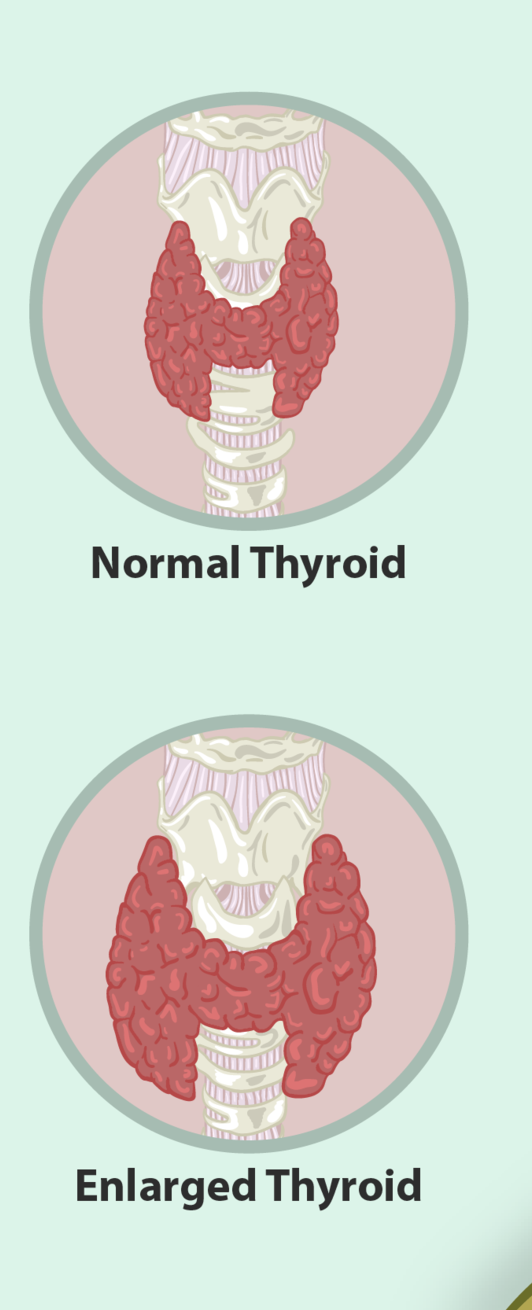

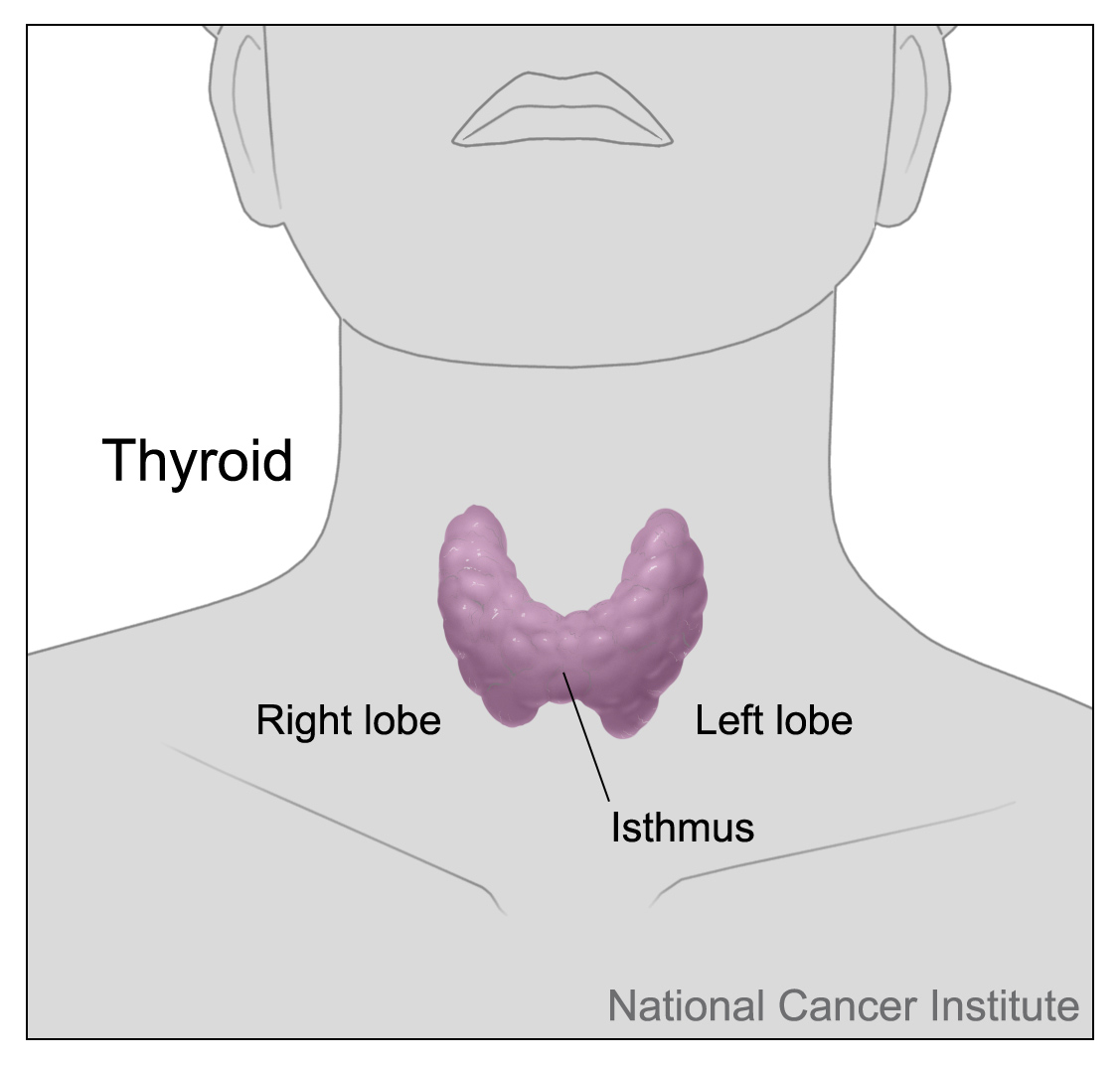

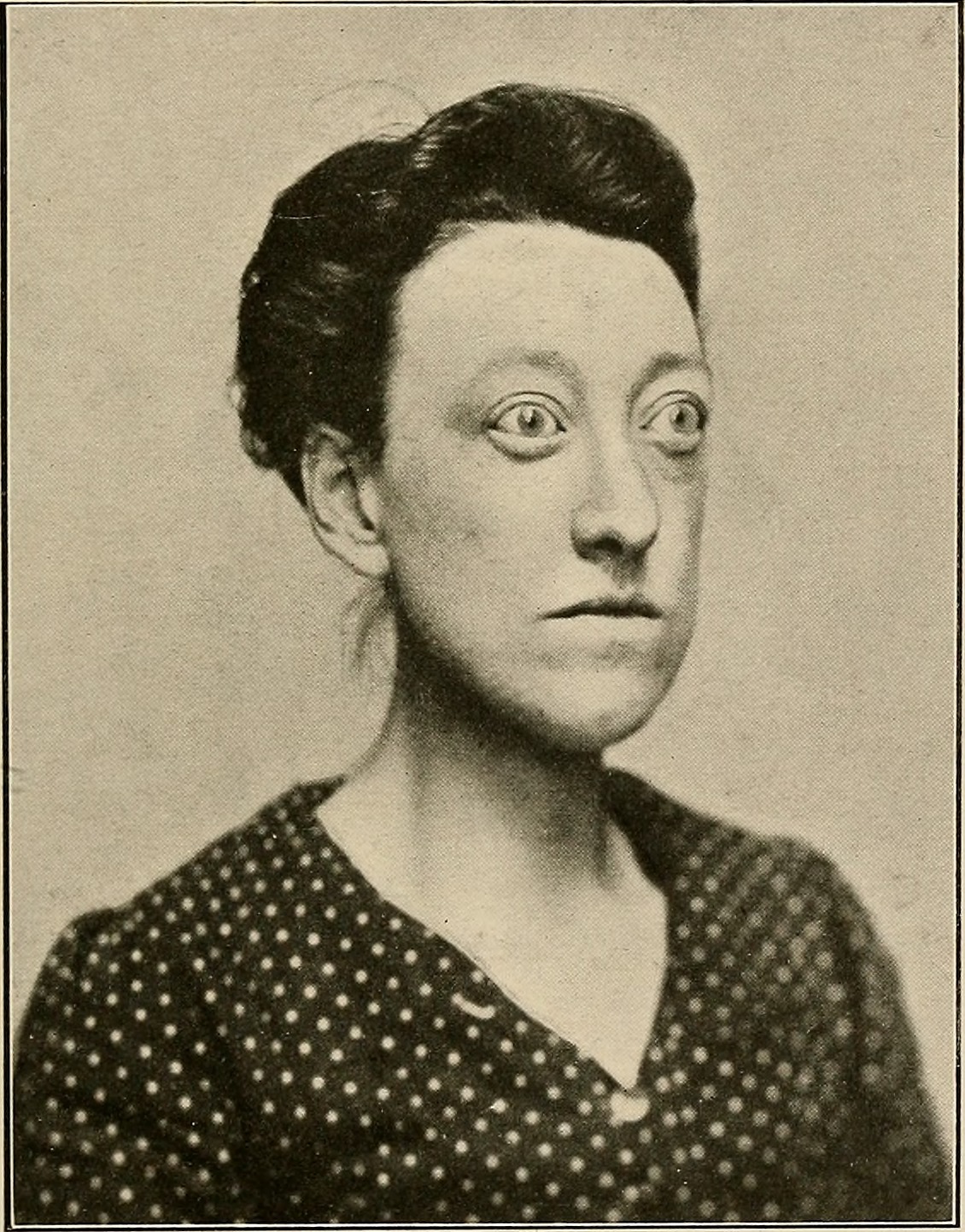

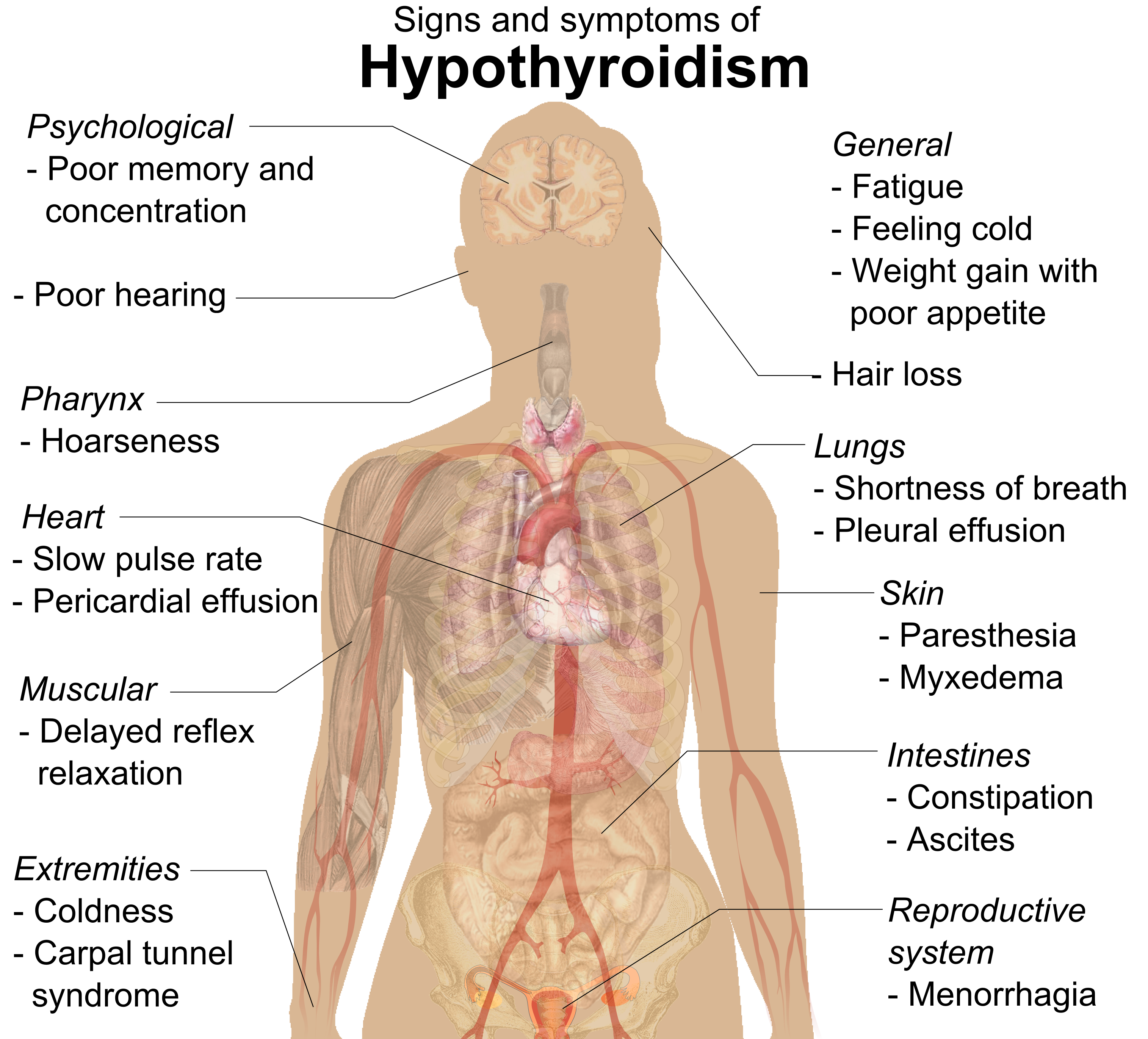

- The thyroid gland and its hormones — which regulate processes including metabolism and calcium homeostasis — how the thyroid is regulated, and the disorders that can occur when there are problems in thyroid hormone regulation (such as hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism).

- The adrenal glands, which secrete hormones that regulate processes such as metabolism, electrolyte balance, responses to stress, and reproductive functions, and the disorders that can occur when there are problems in adrenal hormone regulation, such as Cushing’s syndrome and Addison’s disease.

- The pancreas, which secretes hormones that regulate blood glucose levels (such as insulin), and disorders of the pancreas and its hormones, including diabetes.

Later chapters in this book will discuss the glands and hormones involved in the reproductive and immune systems in more depth.

As you read this chapter, think about the following questions:

- Why can hormones have such broad range effects on the body, as we see in PCOS?

- Which hormones normally regulate blood glucose? How is this related to diabetes?

- What are androgens? How do you think their functions relate to some of the symptoms that Gabrielle is experiencing?

Attribution

Figure 9.1.1

Chapter 9 case study [photo] by niklas_hamann on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Reference

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Polycystic ovary syndrome [online article]. MayoClinic.com. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/pcos/multimedia/polycystic-ovary-syndrome/img-20007768

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Doing the ‘Fly

The swimmer in the Figure 13.3.1 photo is doing the butterfly stroke, a swimming style that requires the swimmer to carefully control his breathing so it is coordinated with his swimming movements. Breathing is the process of moving air into and out of the lungs, which are the organs in which gas exchange takes place between the atmosphere and the body. Breathing is also called ventilation, and it is one of two parts of the life-sustaining process of respiration. The other part is gas exchange. Before you can understand how breathing is controlled, you need to know how breathing occurs.

How Breathing Occurs

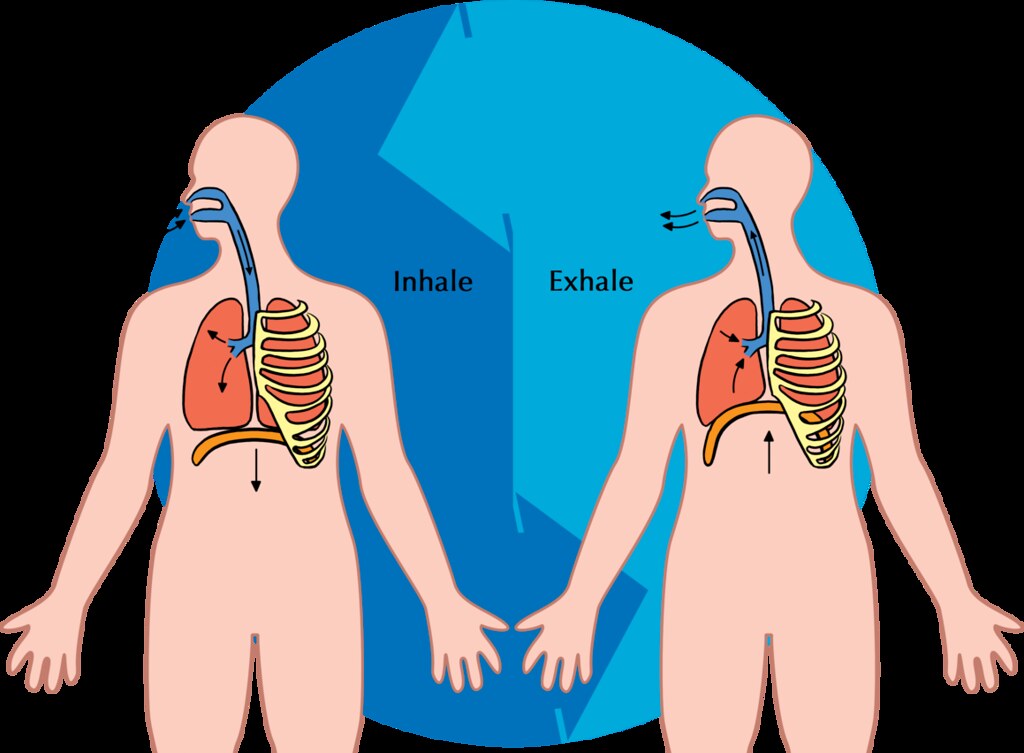

Breathing is a two-step process that includes drawing air into the lungs, or inhaling, and letting air out of the lungs, or exhaling. Both processes are illustrated in Figure 13.3.2.

Inhaling

Inhaling is an active process that results mainly from contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm, shown in Figure 13.3.2. The diaphragm is a large, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs that separates the thoracic (chest) and abdominal cavities. When the diaphragm contracts it moves down causing the thoracic cavity to expand, and the contents of the abdomen to be pushed downward. Other muscles — such as intercostal muscles between the ribs — also contribute to the process of inhalation, especially when inhalation is forced, as when taking a deep breath. These muscles help increase thoracic volume by expanding the ribs outward. The increase in thoracic volume creates a decrease in thoracic air pressure. With the chest expanded, there is lower air pressure inside the lungs than outside the body, so outside air flows into the lungs via the respiratory tract according the the pressure gradient (high pressure flows to lower pressure).

Exhaling

Exhaling involves the opposite series of events. The diaphragm relaxes, so it moves upward and decreases the volume of the thorax. Air pressure inside the lungs increases, so it is higher than the air pressure outside the lungs. Exhalation, unlike inhalation, is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs. With the change in air pressure, the lungs contract to their pre-inflated size, forcing out the air they contain in the process. Air flows out of the lungs, similar to the way air rushes out of a balloon when it is released. If exhalation is forced, internal intercostal and abdominal muscles may help move the air out of the lungs.

Control of Breathing

Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously, as well as unconsciously. Think about using your breath to blow up a balloon. You take a long, deep breath, and then you exhale the air as forcibly as you can into the balloon. Both the inhalation and exhalation are consciously controlled.

Conscious Control of Breathing

You can control your breathing by holding your breath, slowing your breathing, or hyperventilating, which is breathing more quickly and shallowly than necessary. You can also exhale or inhale more forcefully or deeply than usual. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities besides blowing up balloons, including swimming, speech training, singing, playing many different musical instruments (Figure 13.3.3), and doing yoga, to name just a few.

There are limits on the conscious control of breathing. For example, it is not possible for a healthy person to voluntarily stop breathing indefinitely. Before long, there is an irrepressible urge to breathe. If you were able to stop breathing for a long enough time, you would lose consciousness. The same thing would happen if you were to hyperventilate for too long. Once you lose consciousness so you can no longer exert conscious control over your breathing, involuntary control of breathing takes over.

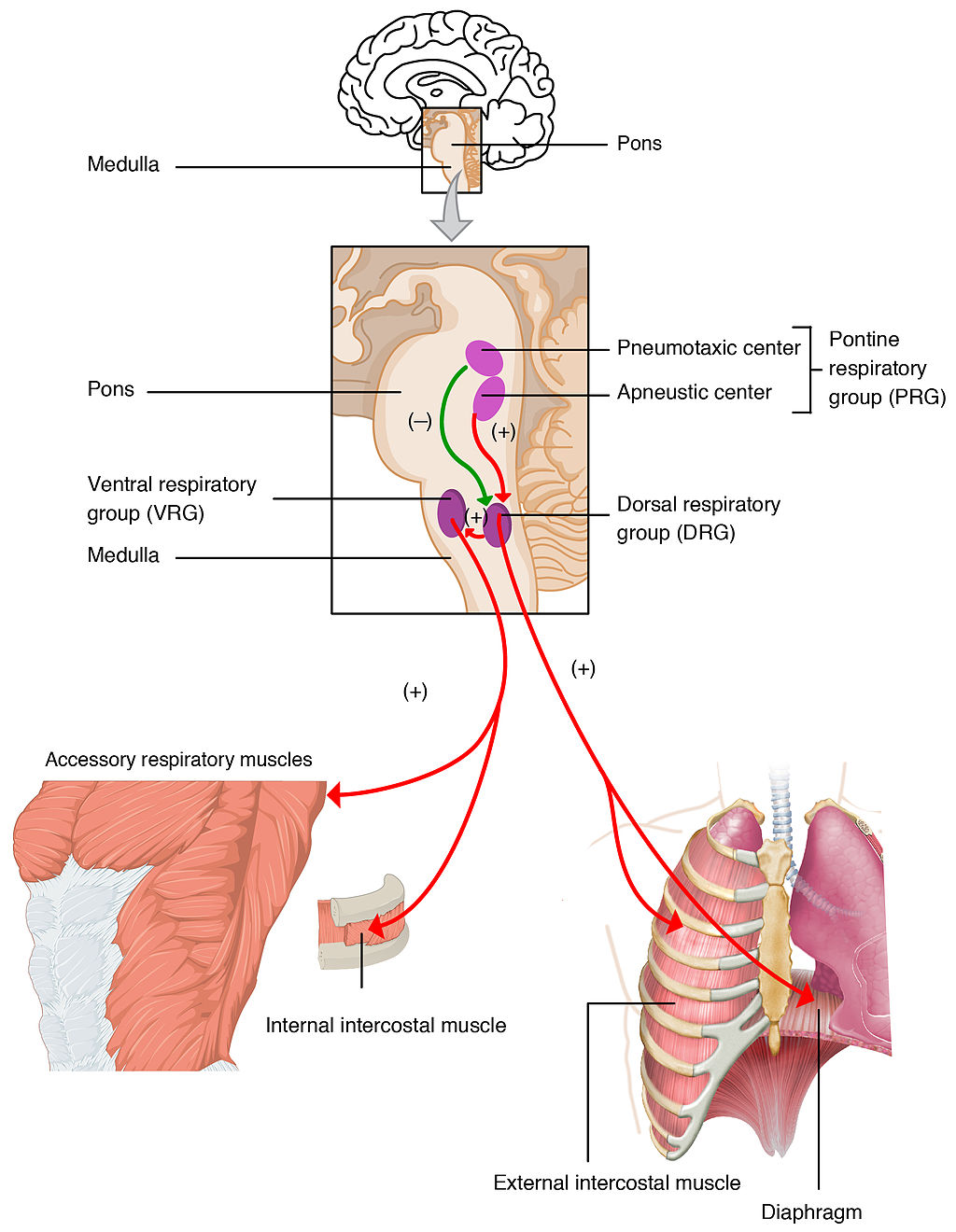

Unconscious Control of Breathing

Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem (see Figure 13.3.4). The respiratory centers automatically and continuously regulate the rate of breathing based on the body’s needs. These are determined mainly by blood acidity, or pH. When you exercise, for example, carbon dioxide levels increase in the blood, because of increased cellular respiration by muscle cells. The carbon dioxide reacts with water in the blood to produce carbonic acid, making the blood more acidic, so pH falls. The drop in pH is detected by chemoreceptors in the medulla. Blood levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide, in addition to pH, are also detected by chemoreceptors in major arteries, which send the “data” to the respiratory centers. The latter respond by sending nerve impulses to the diaphragm, “telling” it to contract more quickly so the rate of breathing speeds up. With faster breathing, more carbon dioxide is released into the air from the blood, and blood pH returns to the normal range.

The opposite events occur when the level of carbon dioxide in the blood becomes too low and blood pH rises. This may occur with involuntary hyperventilation, which can happen in panic attacks, episodes of severe pain, asthma attacks, and many other situations. When you hyperventilate, you blow off a lot of carbon dioxide, leading to a drop in blood levels of carbon dioxide. The blood becomes more basic (alkaline), causing its pH to rise.

Nasal vs. Mouth Breathing

Nasal breathing is breathing through the nose rather than the mouth, and it is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing. The hair-lined nasal passages do a better job of filtering particles out of the air before it moves deeper into the respiratory tract. The nasal passages are also better at warming and moistening the air, so nasal breathing is especially advantageous in the winter when the air is cold and dry. In addition, the smaller diameter of the nasal passages creates greater pressure in the lungs during exhalation. This slows the emptying of the lungs, giving them more time to extract oxygen from the air.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Drowning is defined as respiratory impairment from being in or under a liquid. It is further classified according to its outcome into: death, ongoing health problems, or no ongoing health problems (full recovery). Four hundred Canadians die annually from drowning, and drowning is one of the leading causes of death in children under the age of five. There are some potentially dangerous myths about drowning, and knowing what they are might save your life or the life of a loved one, especially a child.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| "People drown when they aspirate water into their lungs." | Generally, in the early stages of drowning, very little water enters the lungs. A small amount of water entering the trachea causes a muscular spasm in the larynx that seals the airway and prevents the passage of water into the lungs. This spasm is likely to last until unconsciousness occurs. |

| "You can tell when someone is drowning because they will shout for help and wave their arms to attract attention." | The muscular spasm that seals the airway prevents the passage of air, as well as water, so a person who is drowning is unable to shout or call for help. In addition, instinctive reactions that occur in the final minute or so before a drowning person sinks under the water may look similar to calm, safe behavior. The head is likely to be low in the water, tilted back, with the mouth open. The person may have uncontrolled movements of the arms and legs, but they are unlikely to be visible above the water. |

| "It is too late to save a person who is unconscious in the water." | An unconscious person rescued with an airway still sealed from the muscular spasm of the larynx stands a good chance of full recovery if they start receiving CPR within minutes. Without water in the lungs, CPR is much more effective. Even if cardiac arrest has occurred so the heart is no longer beating, there is still a chance of recovery. The longer the brain goes without oxygen, however, the more likely brain cells are to die. Brain death is likely after about six minutes without oxygen, except in exceptional circumstances, such as young people drowning in very cold water. There are examples of children surviving, apparently without lasting ill effects, for as long as an hour in cold water. Rescuers retrieving a child from cold water should attempt resuscitation even after a protracted period of immersion. |

| "If someone is drowning, you should start administering CPR immediately, even before you try to get the person out of the water." | Removing a drowning person from the water is the first priority, because CPR is ineffective in the water. The goal should be to bring the person to stable ground as quickly as possible and then to start CPR. |

| "You are unlikely to drown unless you are in water over your head." | Depending on circumstances, people have drowned in as little as 30 mm (about 1 ½ in.) of water. Inebriated people or those under the influence of drugs, for example, have been known to have drowned in puddles. Hundreds of children have drowned in the water in toilets, bathtubs, basins, showers, pails, and buckets (see Figure 13.3.5). |

13.3 Summary

- Breathing, or ventilation, is the two-step process of drawing air into the lungs (inhaling) and letting air out of the lungs (exhaling). Inhalation is an active process that results mainly from contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm. Exhalation is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs when the diaphragm relaxes.

- Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously, as well as unconsciously. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities, including swimming and singing. There are limits on the conscious control of breathing, however. If you try to hold your breath, for example, you will soon have an irrepressible urge to breathe.

- Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem. They respond to variations in blood pH by either increasing or decreasing the rate of breathing as needed to return the pH level to the normal range.

- Nasal breathing is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing because it does a better job of filtering, warming, and moistening incoming air. It also results in slower emptying of the lungs, which allows more oxygen to be extracted from the air.

- Drowning is a major cause of death in Canada, in particular in children under the age of five. It is important to supervise small children when they are playing in, around, or with water.

13.3 Review Questions

- Define breathing.

-

- Give examples of activities in which breathing is consciously controlled.

- Explain how unconscious breathing is controlled.

- Young children sometimes threaten to hold their breath until they get something they want. Why is this an idle threat?

- Why is nasal breathing generally considered superior to mouth breathing?

- Give one example of a situation that would cause blood pH to rise excessively. Explain why this occurs.

13.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl4cU9sG_08

How breathing works - Nirvair Kaur, TED-Ed, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDtKBXOEsoM

How do ventilators work? - Alex Gendler, TED-Ed, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFnGhrC_3Gs&feature=emb_logo

How I held my breath for 17 minutes | David Blaine, TED, 2010.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vca6DyFqt4c&feature=emb_logo

The Ultimate Relaxation Technique: How To Practice Diaphragmatic Breathing For Beginners, Kai Simon, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 13.3.1

US_Marines_butterfly_stroke by Cpl. Jasper Schwartz from U.S. Marine Corps on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.3.2

Inhale Exhale/Breathing cycle by Siyavula Education on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 13.3.3

Trumpet/ Frenchmen Street [photo] by Morgan Petroski on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 13.3.4

Respiratory_Centers_of_the_Brain by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 13.3.5

Lily & Ava in the Kiddie Pool by mob mob on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.20 Respiratory centers of the brain [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-3-the-process-of-breathing

Kai Simon. (2015, January 11). The ultimate relaxation technique: How to practice diaphragmatic breathing for beginners. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vca6DyFqt4c&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2010, January 19). How I held my breath for 17 minutes | David Blaine. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFnGhrC_3Gs&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2012, October 4). How breathing works - Nirvair Kaur. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl4cU9sG_08&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, May 21). How do ventilators work? - Alex Gendler. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDtKBXOEsoM&feature=youtu.be

One Piano, Four Hands

Did you ever see two people play the same piano? How do they coordinate all the movements of their own fingers — let alone synchronize them with those of their partner? The peripheral nervous system plays an important part in this challenge.

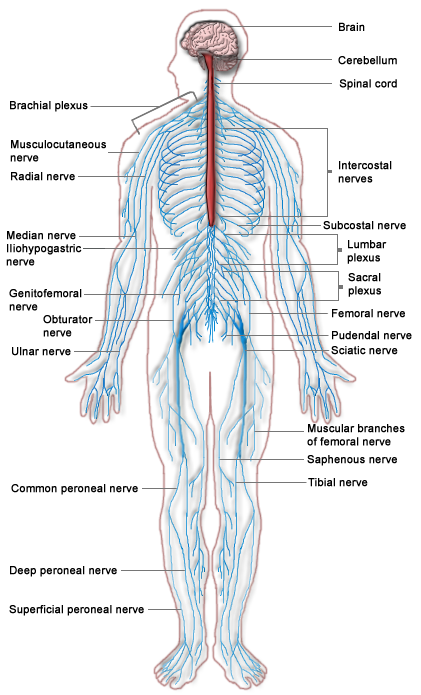

What Is the Peripheral Nervous System?

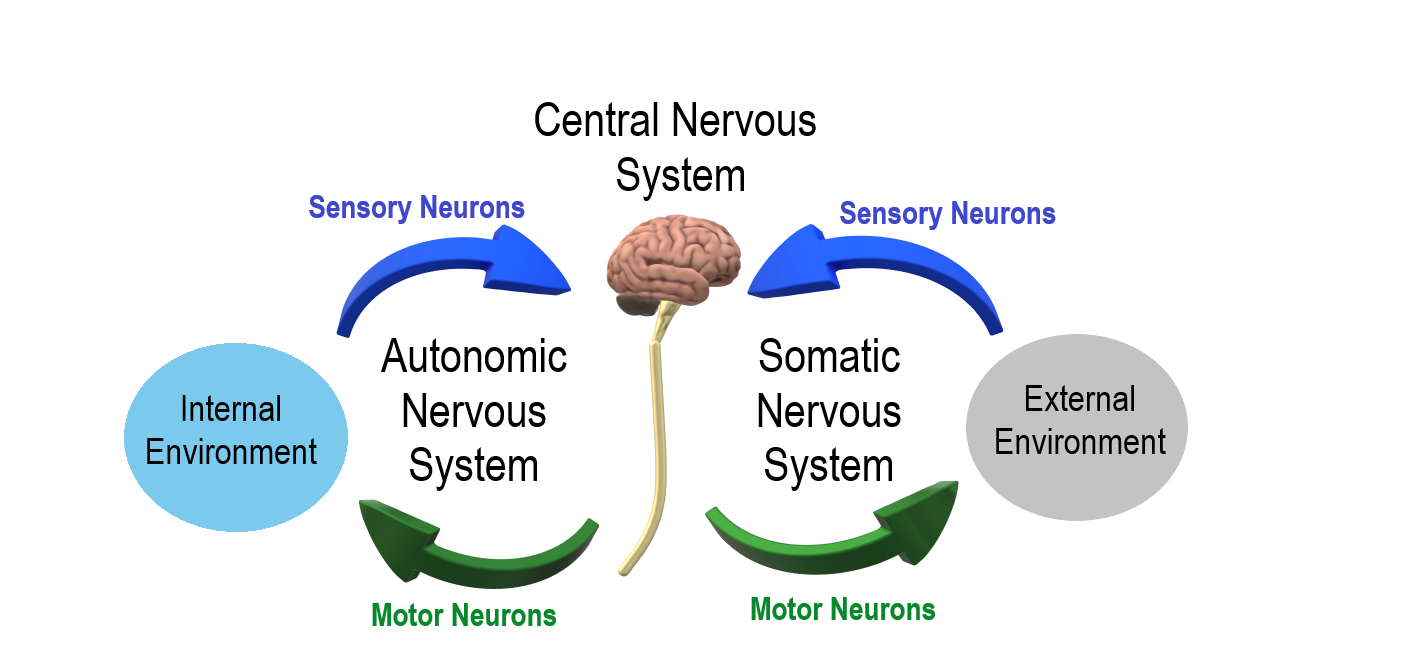

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside of the central nervous system (CNS). The main function of the PNS is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism. It serves as a communication relay, going back and forth between the CNS and muscles, organs, and glands throughout the body.

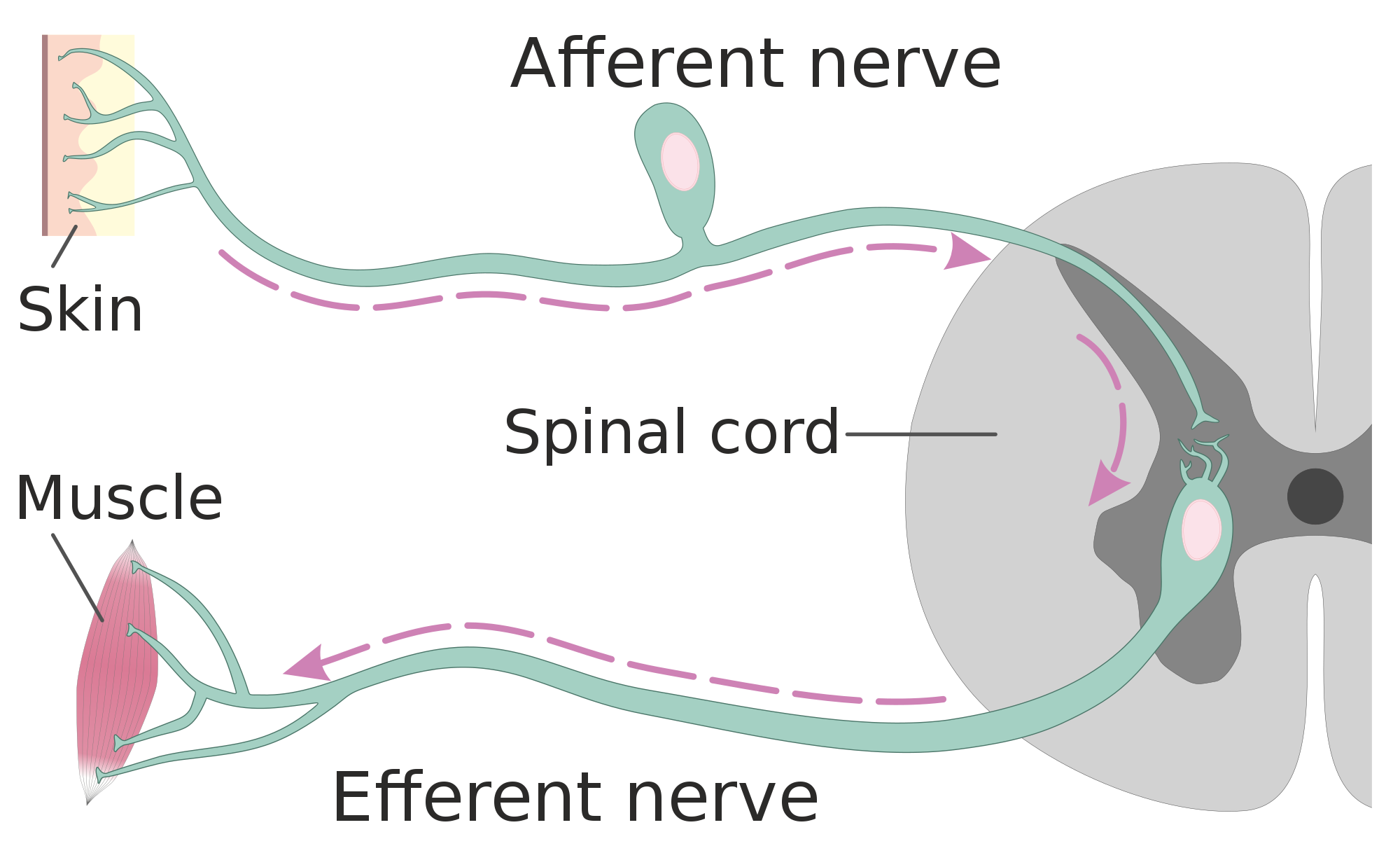

Tissues of the Peripheral Nervous System

The PNS is mostly made up of cable-like bundles of axons called nerves, as well as clusters of neuronal cell bodies called ganglia (singular, ganglion). Nerves are generally classified as sensory, motor, or mixed nerves based on the direction in which they carry nerve impulses.

- Sensory nerves transmit information from sensory receptors in the body to the CNS. Sensory nerves are also called afferent nerves. You can see an example in the figure below.

- Motor nerves transmit information from the CNS to muscles, organs, and glands. Motor nerves are also called efferent nerves. You can see one in the figure below.

- Mixed nerves contain both sensory and motor neurons, so they can transmit information in both directions. They have both afferent and efferent functions.

Divisions of the Peripheral Nervous System

The PNS is divided into two major systems, called the autonomic nervous system and the somatic nervous system. In the diagram below, the autonomic system is shown on the left, and the somatic system on the right. Both systems of the PNS interact with the CNS and include sensory and motor neurons, but they use different circuits of nerves and ganglia.

Somatic Nervous System

The somatic nervous system primarily senses the external environment and controls voluntary activities about which decisions and commands come from the cerebral cortex of the brain. When you feel too warm, for example, you decide to turn on the air conditioner. As you walk across the room to the thermostat, you are using your somatic nervous system. In general, the somatic nervous system is responsible for all of your conscious perceptions of the outside world, as well as all of the voluntary motor activities you perform in response. Whether it’s playing a piano, driving a car, or playing basketball, you can thank your somatic nervous system for making it possible.

Somatic sensory and motor information is transmitted through 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. Cranial nerves are in the head and neck and connect directly to the brain. Sensory components of cranial nerves transmit information about smells, tastes, light, sounds, and body position. Motor components of cranial nerves control skeletal muscles of the face, tongue, eyeballs, throat, head, and shoulders. Motor components of cranial nerves also control the salivary glands and swallowing. Four of the 12 cranial nerves participate in both sensory and motor functions as mixed nerves, having both sensory and motor neurons.

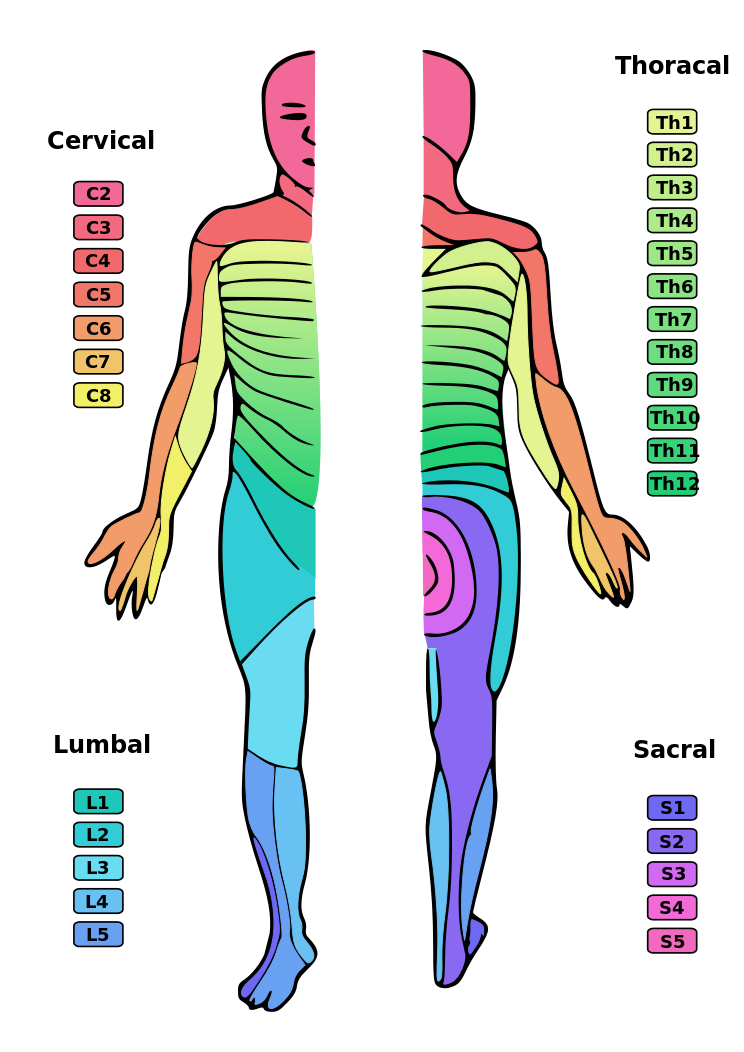

Spinal nerves emanate from the spinal column between vertebrae. All of the spinal nerves are mixed nerves, containing both sensory and motor neurons. The areas of skin innervated by the 31 pairs of spinal nerves are shown in the figure below. These include sensory nerves in the skin that sense pressure, temperature, vibrations, and pain. Other sensory nerves are in the muscles, and they sense stretching and tension. Spinal nerves also include motor nerves that stimulate skeletal muscles to contract, allowing for voluntary body movements.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system primarily senses the internal environment and controls involuntary activities. It is responsible for monitoring conditions in the internal environment and bringing about appropriate changes in them. In general, the autonomic nervous system is responsible for all the activities that go on inside your body without your conscious awareness or voluntary participation.

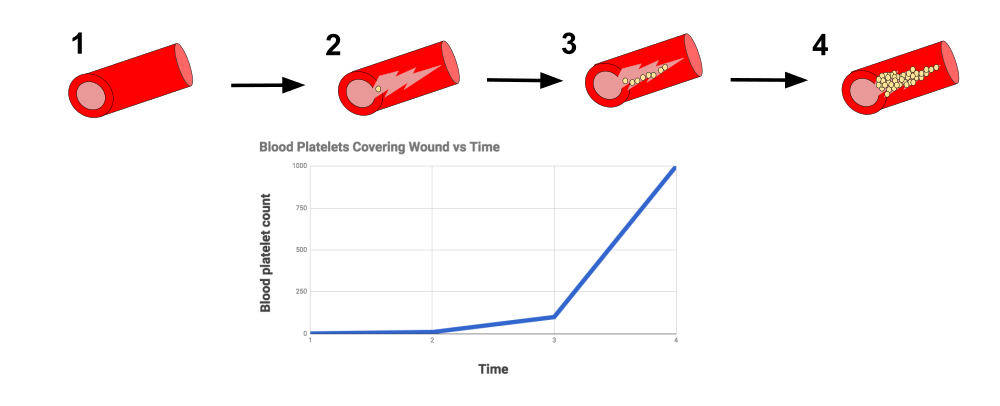

Structurally, the autonomic nervous system consists of sensory and motor nerves that run between the CNS (especially the hypothalamus in the brain), internal organs (such as the heart, lungs, and digestive organs), and glands (such as the pancreas and sweat glands). Sensory neurons in the autonomic system detect internal body conditions and send messages to the brain. Motor nerves in the autonomic system affect appropriate responses by controlling contractions of smooth or cardiac muscle, or glandular tissue. For example, when sensory nerves of the autonomic system detect a rise in body temperature, motor nerves signal smooth muscles in blood vessels near the body surface to undergo vasodilation, and the sweat glands in the skin to secrete more sweat to cool the body.

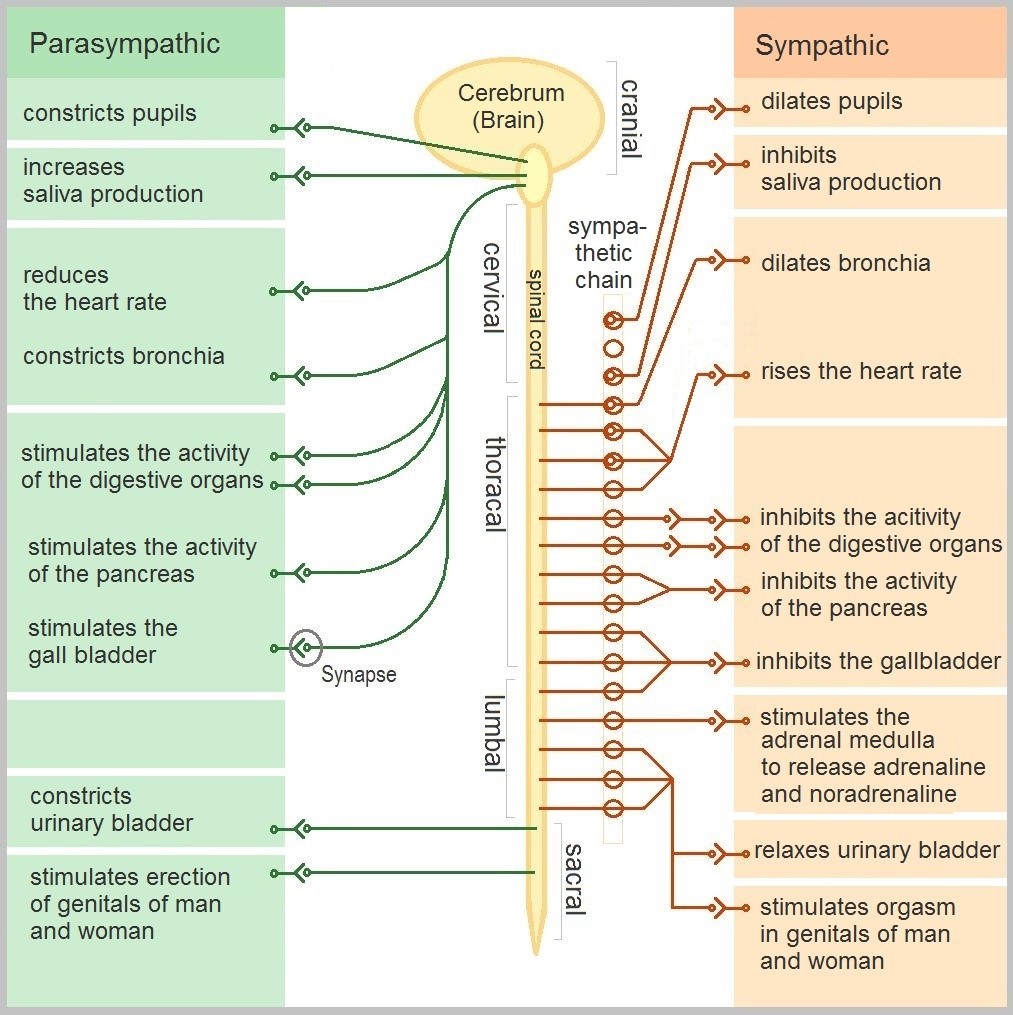

The autonomic nervous system, in turn, has three subdivisions: the sympathetic division, parasympathetic division, and enteric division. The first two subdivisions of the autonomic system are summarized in the figure below. Both affect the same organs and glands, but they generally do so in opposite ways.

- The sympathetic division controls the fight-or-flight response. Changes occur in organs and glands throughout the body that prepare the body to fight or flee in response to a perceived danger. For example, the heart rate speeds up, air passages in the lungs become wider, more blood flows to the skeletal muscles, and the digestive system temporarily shuts down.

- The parasympathetic division returns the body to normal after the fight-or-flight response has occurred. For example, it slows down the heart rate, narrows air passages in the lungs, reduces blood flow to the skeletal muscles, and stimulates the digestive system to start working again. The parasympathetic division also maintains internal homeostasis of the body at other times.

- The enteric division is made up of nerve fibres that supply the organs of the digestive system. This division allows for the local control of many digestive functions.

Disorders of the Peripheral Nervous System

Unlike the CNS — which is protected by bones, meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid — the PNS has no such protections. The PNS also has no blood-brain barrier to protect it from toxins and pathogens in the blood. Therefore, the PNS is more subject to injury and disease than is the CNS. Causes of nerve injury include diabetes, infectious diseases (such as shingles), and poisoning by toxins (such as heavy metals). PNS disorders often have symptoms like loss of feeling, tingling, burning sensations, or muscle weakness. If a traumatic injury results in a nerve being transected (cut all the way through), it may regenerate, but this is a very slow process and may take many months.

Two other diseases of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

- Guillain-Barre syndrome is a rare disease in which the immune system attacks nerves of the PNS, leading to muscle weakness and even paralysis. The exact cause of Guillain-Barre syndrome is unknown, but it often occurs after a viral or bacterial infection. There is no known cure for the syndrome, but most people eventually make a full recovery. Recovery can be slow, however, lasting anywhere from several weeks to several years.

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is a hereditary disorder of the nerves, and one of the most common inherited neurological disorders. It affects predominantly the nerves in the feet and legs, and often in the hands and arms, as well. The disease is characterized by loss of muscle tissue and sense of touch. It is presently incurable.

Feature: My Human Body

The autonomic nervous system is considered to be involuntary because it doesn't require conscious input. However, it is possible to exert some voluntary control over it. People who practice yoga or other so-called mind-body techniques, for example, can reduce their heart rate and certain other autonomic functions. Slowing down these otherwise involuntary responses is a good way to relieve stress and reduce the wear-and-tear that stress can place on the body. Such techniques may also be useful for controlling post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Three types of integrative practices for these purposes are breathing exercises, body-based tension modulation exercises, and mindfulness techniques.

Breathing exercises can help control the rapid, shallow breathing that often occurs when you are anxious or under stress. These exercises can be learned quickly, and they provide immediate feelings of relief. Specific breathing exercises include paced breath, diaphragmatic breathing, and Breathe2Relax or Chill Zone on MindShift™ CBT, which are downloadable breathing practice mobile applications, or "Apps". Try syncing your breathing with Eric Klassen's "Triangle breathing, 1 minute" video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9Q8D6n-3qw

Triangle breathing, 1 minute, Erin Klassen, 2015.

Body-based tension modulation exercises include yoga postures (also known as “asanas”) and tension manipulation exercises. The latter include the Trauma/Tension Release Exercise (TRE) and the Trauma Resiliency Model (TRM). Watch this video for a brief — but informative — introduction to the TRE program:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67R974D8swM&feature=youtu.be

TRE® : Tension and Trauma Releasing Exercises, an Introduction with Jessica Schaffer, Jessica Schaffer Nervous System RESET, 2015.

Mindfulness techniques have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression, as well as those of anxiety and stress. They have also been shown to be useful for pain management and performance enhancement. Specific mindfulness programs include Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness Mind-Fitness Training (MMFT). You can learn more about MBSR by watching the video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TA7P-iCCcY&feature=youtu.be

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness), Palouse Mindfulness, 2017.

8.6 Summary

- The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside the central nervous system (CNS). Its main function is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism.

- The PNS is made up of nerves and ganglia. Nerves are bundles of axons, and ganglia are groups of cell bodies. Nerves are classified as sensory, motor, or a mix of the two.

- The PNS is divided into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic system controls voluntary activities, whereas the autonomic system controls involuntary activities.

- The autonomic nervous system is further divided into sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric divisions. The sympathetic division controls fight-or-flight responses during emergencies, the parasympathetic system controls routine body functions the rest of the time, and the enteric division provides local control over the digestive system.

- The PNS is not as well protected physically or chemically as the CNS, so it is more prone to injury and disease. PNS problems include injury from diabetes, shingles, and heavy metal poisoning. Two disorders of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

8.6 Review Questions

- Describe the general structure of the peripheral nervous system. State its primary function.

- What are ganglia?

- Identify three types of nerves based on the direction in which they carry nerve impulses.

- Outline all of the divisions of the peripheral nervous system.

- Compare and contrast the somatic and autonomic nervous systems.

- When and how does the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system affect the body?

- What is the function of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system? Specifically, how does it affect the body?

- Name and describe two peripheral nervous system disorders.

- Give one example of how the CNS interacts with the PNS to control a function in the body.

- For each of the following types of information, identify whether the neuron carrying it is sensory or motor, and whether it is most likely in the somatic or autonomic nervous system:

- Visual information

- Blood pressure information

- Information that causes muscle contraction in digestive organs after eating

- Information that causes muscle contraction in skeletal muscles based on the person’s decision to make a movement

-

8.6 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySIDMU2cy0Y&feature=emb_logo

Phantom Limbs Explained, Plethrons, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=73yo5nJne6c&feature=emb_logo

Why Do Hot Peppers Cause Pain? Reactions, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 8.6.1

Kid’s piant duet by PJMixer on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/) license.

Figure 8.6.2

Nervous_system_diagram by ¤~Persian Poet Gal on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.6.3

Afferent_and_efferent_neurons_en.svg by Helixitta on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 8.6.4

Autonomic and Somatic Nervous System by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 8.6.5

Dermatoms.svg by Ralf Stephan (mailto:ralf@ark.in-berlin.de) on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.6.6

The_Autonomic_Nervous_System by Geo-Science-International on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC0 1.0 Universal

Public Domain Dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

References

Erin Klassen. (2015, December 15). Triangle breathing, 1 minute. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9Q8D6n-3qw&feature=youtu.be

Jessica Schaffer Nervous System RESET. (2015, January 15). TRE® : Tension and trauma releasing exercises, an Introduction with Jessica Schaffer. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67R974D8swM&feature=youtu.be

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/charcot-marie-tooth-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350517

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Diabetes [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20371444

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Guillain-Barre syndrome [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/guillain-barre-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20362793

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Shingles [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/shingles/symptoms-causes/syc-20353054

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Stroke [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stroke/symptoms-causes/syc-20350113

Palouse Mindfulness. (2017, March 25). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness), YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TA7P-iCCcY&feature=youtu.be

Plethrons, (2015, March 23). Phantom limbs explained. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySIDMU2cy0Y&feature=youtu.be

Reactions. (2015, December 1). Why do hot peppers cause pain? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=73yo5nJne6c&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a diagram of all the components of the endocrine system. This includes the pineal and pituitary glands in the brain, the thyroid gland surrounding the larynx, the thymus gland sitting above the heart, the adrenal glands sitting above the kidneys, the pancreas, and in females, the uterus and ovaries and in males the testes.

A group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body.

A microorganism which causes disease.

An organisms that is so small it is invisible to the human eye.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Flight Risk

Nineteen-year-old Malcolm is about to take his first plane flight. Shortly after he boards the plane and sits down, a man in his late sixties sits next to him in the aisle seat. About half an hour after the plane takes off, the pilot announces that she is turning the seat belt light off, and that it is safe to move around the cabin.

The man in the aisle seat — who has introduced himself to Malcolm as Willie — immediately unbuckles his seat belt and paces up and down the aisle a few times before returning to his seat. After about 45 minutes, Willie gets up again, walks some more, then sits back down and does some foot and leg exercises. After the third time Willie gets up and paces the aisles, Malcolm asks him whether he is walking so much to accumulate steps on a pedometer or fitness tracking device. Willie laughs and says no. He is actually trying to do something even more important for his health — prevent a blood clot from forming in his legs.

Willie explains that he has a chronic condition: heart failure. Although it sounds scary, his condition is currently well-managed, and he is able to lead a relatively normal lifestyle. However, it does put him at risk of developing other serious health conditions, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which is when a blood clot occurs in the deep veins, usually in the legs. Air travel — and other situations where a person has to sit for a long period of time — increases the risk of DVT. Willie’s doctor said that he is healthy enough to fly, but that he should walk frequently and do leg exercises to help avoid a blood clot.

As you read this chapter, you will learn about the heart, blood vessels, and blood that make up the cardiovascular system, as well as disorders of the cardiovascular system, such as heart failure. At the end of the chapter you will learn more about why DVT occurs, why Willie has to take extra precautions when he flies, and what can be done to lower the risk of DVT and its potentially deadly consequences.

Chapter Overview: Cardiovascular System

In this chapter, you will learn about the cardiovascular system, which transports substances throughout the body. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The major components of the cardiovascular system: the heart, blood vessels, and blood.

- The functions of the cardiovascular system, including transporting needed substances (such as oxygen and nutrients) to the cells of the body, and picking up waste products.

- How blood is oxygenated through the pulmonary circulation, which transports blood between the heart and lungs.

- How blood is circulated throughout the body through the systemic circulation.

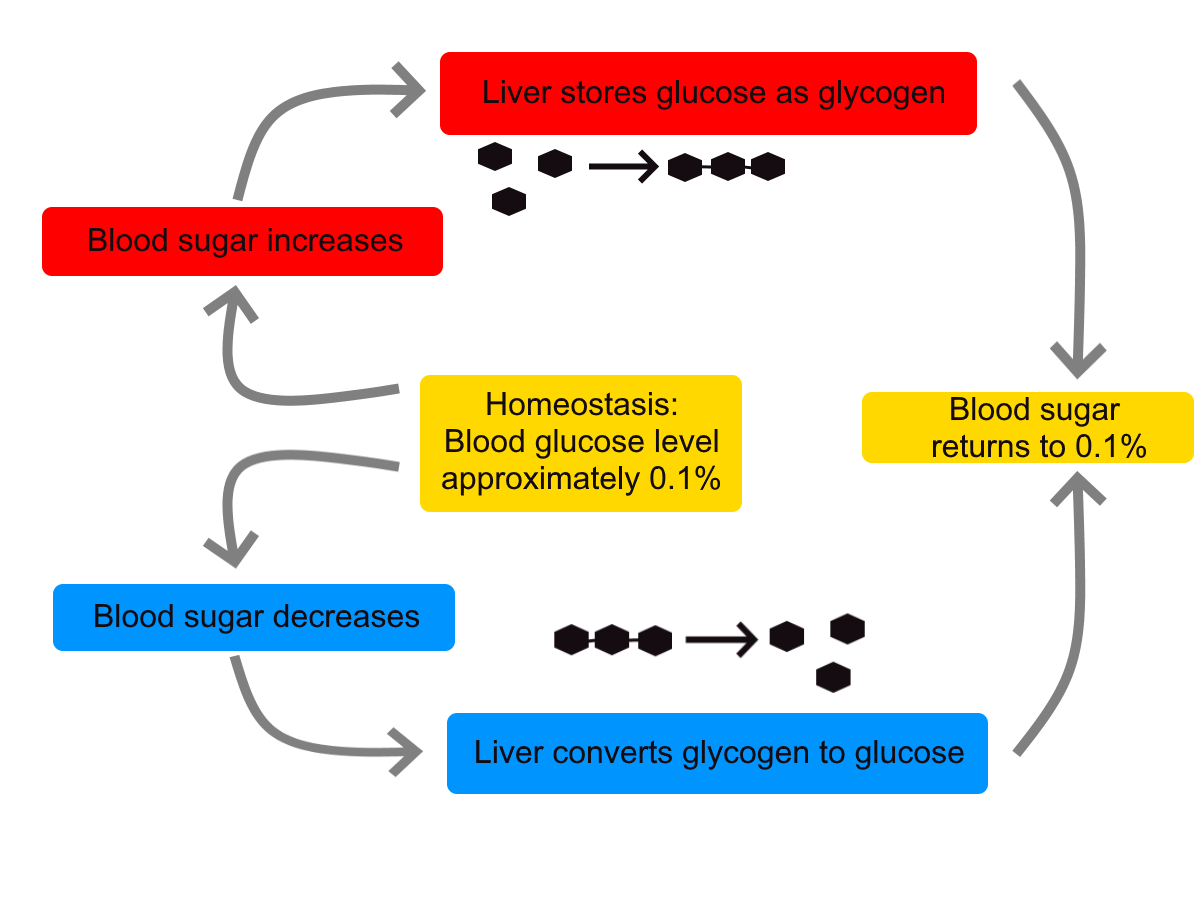

- The components of blood — including plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets — and their specific functions.

- Types of blood vessels — including arteries, veins, and capillaries — and their functions, similarities, and differences.

- The structure of the heart, how it pumps blood, and how contractions of the heart are controlled.

- What blood pressure is and how it is regulated.

- Blood disorders, including anemia, HIV, and leukemia.

- Cardiovascular diseases (including heart attack, stroke, and angina), and the risk factors and precursors — such as high blood pressure and atherosclerosis — that contribute to them.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- What is heart failure?Why do you think it increases the risk of DVT?

- What is a blood clot? What are possible health consequences of blood clots?

- Why do you think sitting for long periods of time increases the risk of DVT? Why does walking and exercising the legs help reduce this risk?

Attribution

Figure 14.1.1

aircraft-1583871_1920 [photo] by olivier89 from Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/de/service/license/).

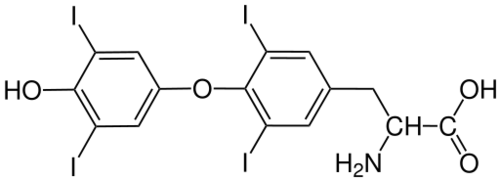

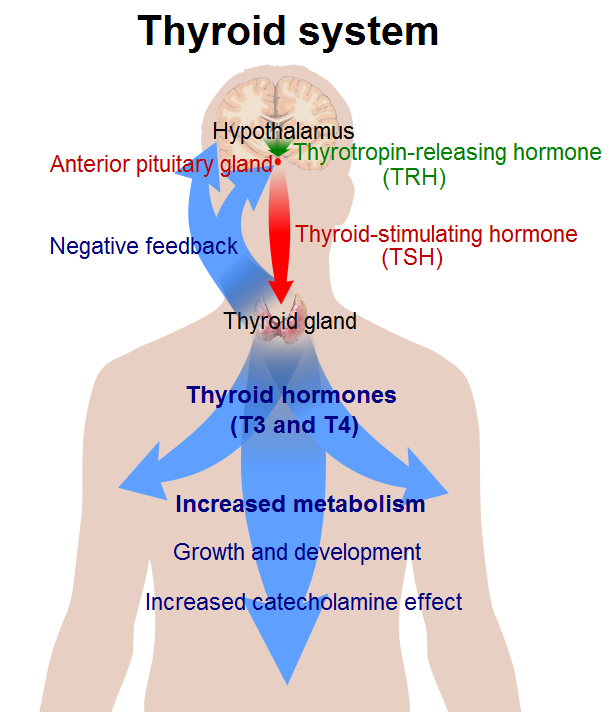

Image shows a diagram of the negative feedback loop governing thyroid gland function. In the absence of sufficient levels of thyroid hormones, the hypothalamus will secrete TRH, which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete TSH, which stimulates the thyroid gland to make thyroid hormones. Sufficient blood levels of thyroid hormone inhibit the hypothalamus from secreting TRH, halting the pathway, until thyroid hormone level sdrop again

Image shows a diagram of how alzheimer's progresses. In preclinical AD, just a small portion of the brain is affected. More of the brain and more areas of the brain are affected in mild to moderate AD. In severe AD, most of the brain is affected.

Pills from Pee

The medication pictured in Figure 9.3.1 with the brand name Progynon was a drug used to control the effects of menopause in women. The pills first appeared in 1928 and contained the human sex hormone estrogen. Estrogen secretion declines in women around the time of menopause and may cause symptoms like mood swings and hot flashes. The pills were supposed to ease the symptoms by supplementing estrogen in the body. The manufacturer of Progynon obtained estrogen for the pills from the urine of pregnant women, because it was a cheap source of the hormone. Progynon is still used today to treat menopausal symptoms. Although the drug has been improved over the years, it still contains estrogen, which is an example of an endocrine hormone.

How Do Endocrine Hormones Work?

Endocrine hormones like estrogen are messenger molecules secreted by endocrine glands into the bloodstream. They travel throughout the body in the circulation. Although they reach virtually every cell in the body in this way, each hormone affects only certain cells, called target cells. A target cell is the type of cell on which a hormone has an effect. A target cell is affected by a particular hormone because it has receptor proteins — either on the cell surface or within the cell — that are specific to that hormone. An endocrine hormone travels through the bloodstream until it finds a target cell with a matching receptor to which it can bind. When the hormone binds to the receptor, it causes changes within the cell. The manner in which it changes the cell depends on whether the hormone is a steroid hormone or a non-steroid hormone.

Steroid Hormones

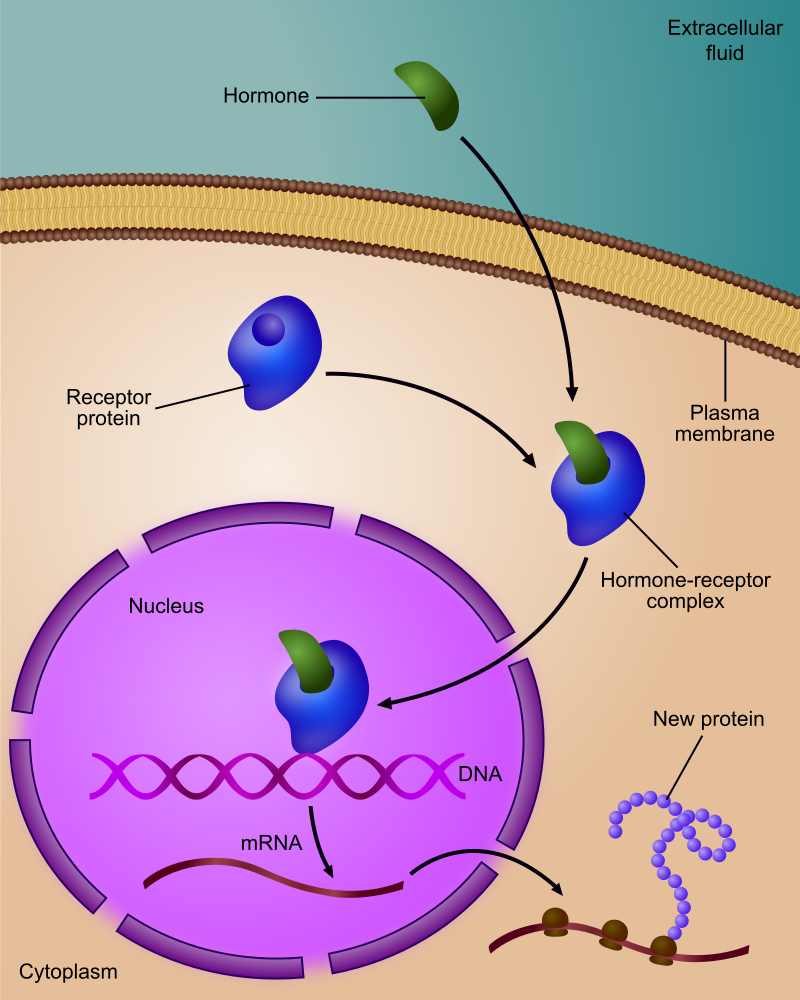

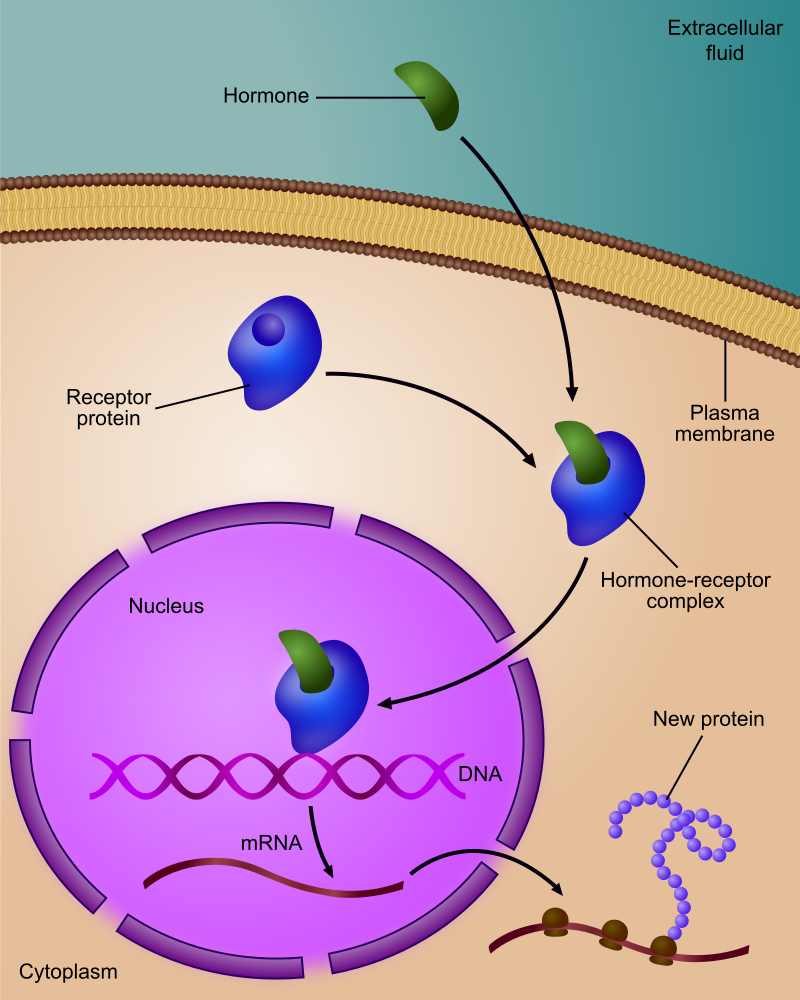

A steroid hormone (such as estrogen) is made of lipids. It is fat soluble, so it can diffuse across a target cell’s plasma membrane, which is also made of lipids. Once inside the cell, a steroid hormone binds with receptor proteins in the cytoplasm. As you can see in Figure 9.3.2, the steroid hormone and its receptor form a complex — called a steroid complex — which moves into the nucleus, where it influences the expression of genes. Examples of steroid hormones include cortisol, which is secreted by the adrenal glands, and sex hormones, which are secreted by the gonads.

Non-Steroid Hormones

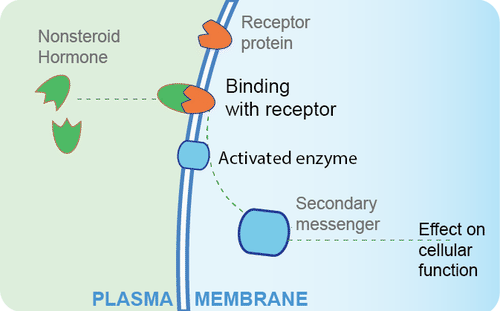

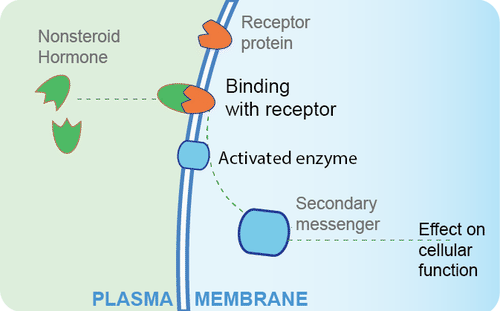

A non-steroid hormoneis made of amino acids. It is not fat soluble, so it cannot diffuse across the plasma membrane of a target cell. Instead, it binds to a receptor protein on the cell membrane. In the Figure 9.3.3 diagram, you can see that the binding of the hormone with the receptor activates an enzyme in the cell membrane. The enzyme then stimulates another molecule, called the second messenger, which influences processes inside the cell. Most endocrine hormones are non-steroid hormones. Examples include glucagon and insulin, both produced by the pancreas.

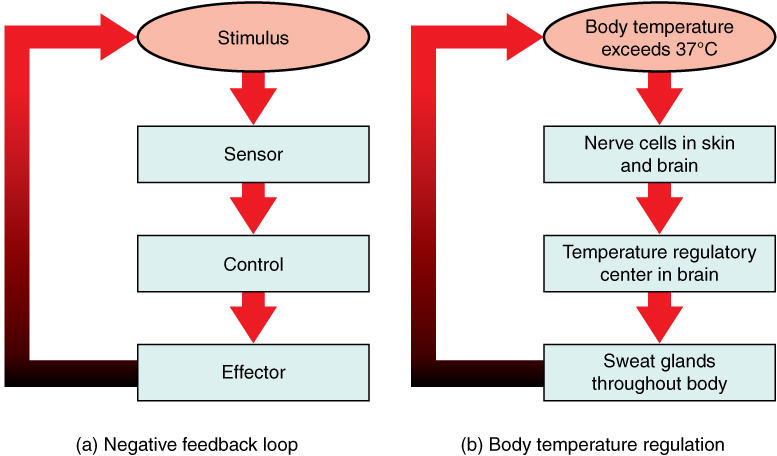

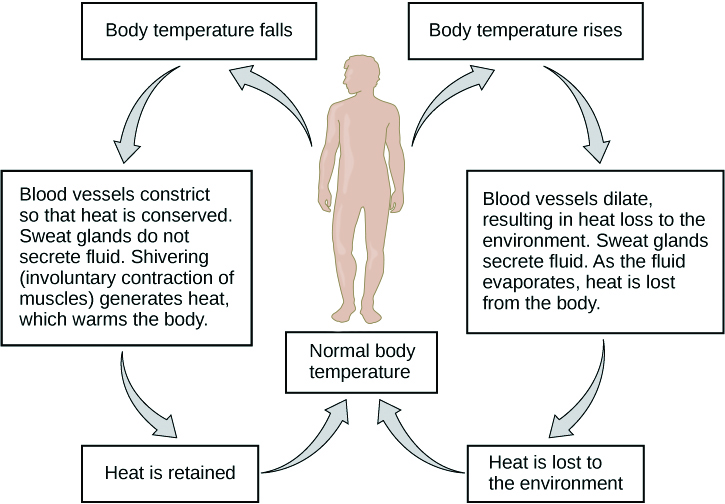

Regulation of Endocrine Hormones

Endocrine hormones regulate many body processes, but what regulates the secretion of endocrine hormones? Most endocrine hormones are controlled by feedback mechanisms. A feedback mechanism is a loop in which a product feeds back to control its own production. Feedback loops may be either negative or positive.

- Most endocrine hormones are regulated by negative feedback loops. Negative feedback keeps the concentration of a hormone within a relatively narrow range, and maintains homeostasis.

- Very few endocrine hormones are regulated by positive feedback loops. Positive feedback causes the concentration of a hormone to become increasingly higher.

Regulation by Negative Feedback

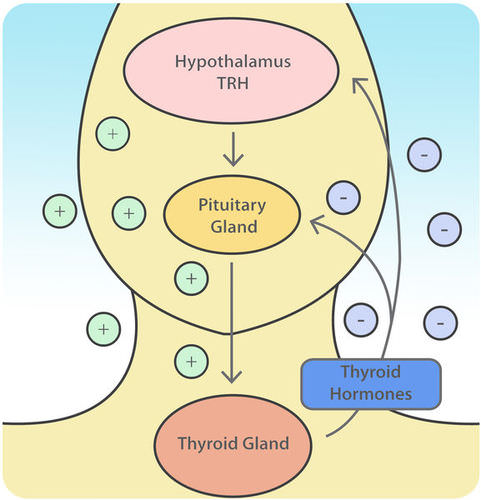

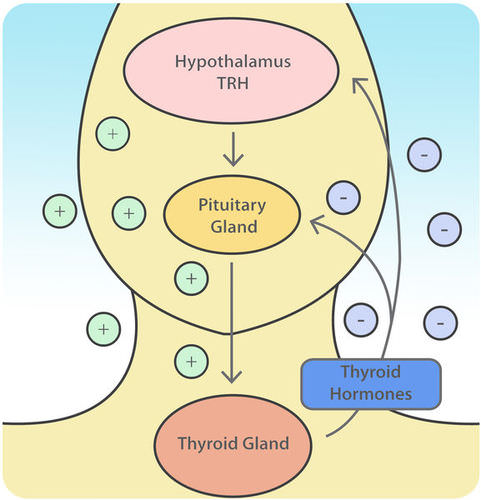

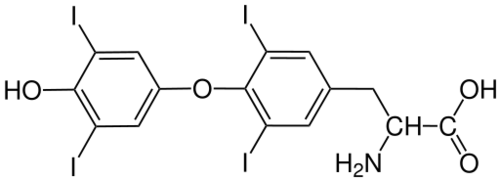

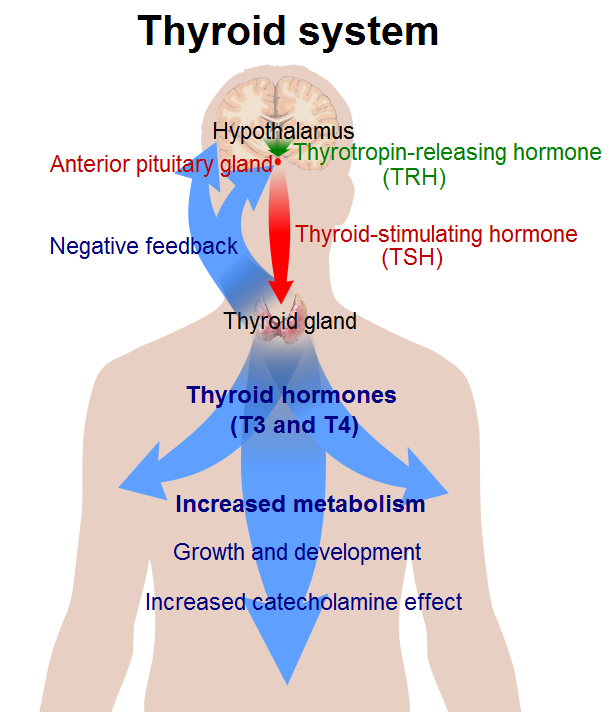

A negative feedback loop controls the synthesis and secretion of hormones by the thyroid gland. This loop includes the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, in addition to the thyroid, as shown in the diagram (Figure 9.3.4). When the levels of thyroid hormones circulating in the blood fall too low, the hypothalamus secretes thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH). This hormone travels directly to the pituitary gland through the thin stalk connecting the two structures. In the pituitary gland, TRH stimulates the pituitary to secrete thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH, in turn, travels through the bloodstream to the thyroid gland, and stimulates it to secrete thyroid hormones. This continues until the blood levels of thyroid hormones are high enough. At that point, the thyroid hormones feed back to stop the hypothalamus from secreting TRH and the pituitary from secreting TSH. Without the stimulation of TSH, the thyroid gland stops secreting its hormones. Eventually, the levels of thyroid hormones in the blood start to fall too low again. When that happens, the hypothalamus releases TRH, and the loop repeats.

Regulation by Positive Feedback

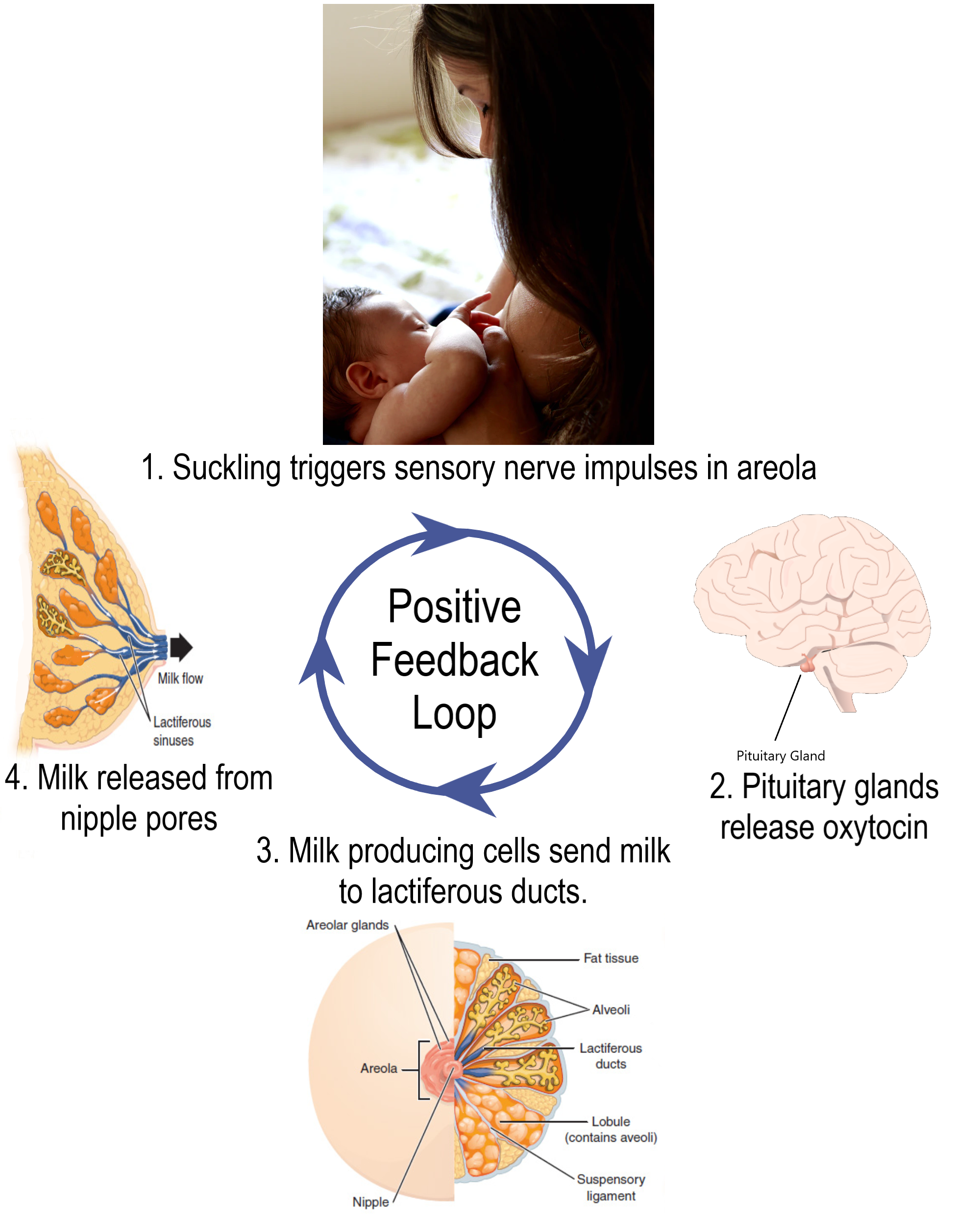

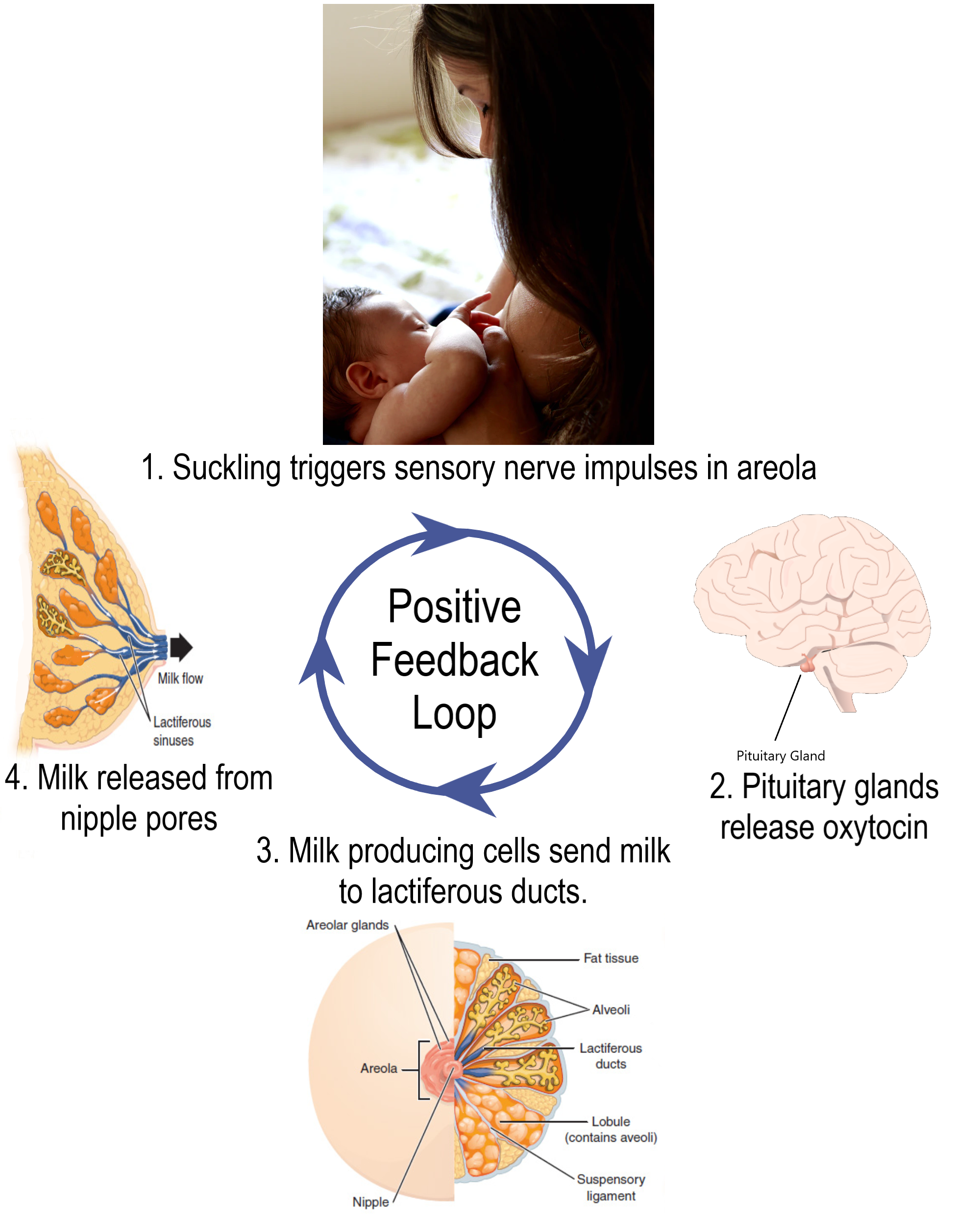

Prolactin is a non-steroid endocrine hormone secreted by the pituitary gland. One of the functions of prolactin is to stimulate a nursing mother’s mammary glands to produce milk. The regulation of prolactin in the mother is controlled by a positive feedback loop that involves the nipples, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and mammary glands. Positive feedback begins when a baby suckles on the mother’s nipple. Nerve impulses from the nipple reach the hypothalamus, which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete prolactin. Prolactin travels in the blood to the mammary glands and stimulates them to produce milk. The release of milk causes the baby to continue suckling, which causes more prolactin to be secreted and more milk to be produced. The positive feedback loop continues until the baby stops suckling at the breast.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Anabolic steroids are synthetic versions of the naturally occurring male sex hormone testosterone. Male hormones have androgenic (or masculinizing) effects, but they also have anabolic (or muscle-building) effects. The anabolic effects are the reason that synthetic steroids are used by athletes. In addition to building muscles, they also accelerate the development of bones and red blood cells, increase endurance so athletes can train harder and longer, and speed up muscle recovery. Unfortunately, these benefits of steroid use come with costs. If you ever consider taking anabolic steroids to build muscles and improve athletic performance, consider the following myths and corresponding realities.

Myth |

Reality |

| "Steroids are safe." | Steroid use may cause several serious side effects. Prolonged use may increase the risk of liver cancer, heart disease, and high blood pressure. |

| "Steroids will not stunt your growth." | Teens who take steroids before they have finished growing in height may have their growth stunted so they remain shorter throughout life than they would otherwise have been. Such stunting occurs because steroids increase the rate at which skeletal maturity is reached. Once skeletal maturity occurs, additional growth in height is impossible. |

| "Steroids do not cause drug dependency." | Steroid use may cause dependency, as evidenced by the negative effects of stopping steroid use. These negative effects may include insomnia, fatigue, and depressed mood, among others. |

| "There is no such thing as 'roid rage.'" | Steroid use has been shown to increase aggressiveness in some people. It has also been implicated in a number of violent acts committed by people who had not demonstrated violent tendencies until they started using steroids. |

| "Only males use steroids." | Although steroid use is more common in males than females, some females also use steroids. They use them to build muscle and improve physical performance, generally either for athletic competition or for self-defense. |

9.3 Summary

- Endocrine hormones are messenger molecules secreted by endocrine glands into the bloodstream. They travel throughout the body but affect only certain cells, called target cells, which have receptors specific to particular hormones.

- Steroid hormones such as estrogen are endocrine hormones made of lipids that cross plasma membranes and bind to receptors inside target cells. The hormone-receptor complexes then move into the nucleus, where they influence gene expression.

- Non-steroid hormones (such as insulin) are endocrine hormones made of amino acids that bind to receptors on the surface of target cells. This activates an enzyme in the plasma membrane, and the enzyme controls a second messenger molecule, which influences cell processes.

- Most endocrine hormones are controlled by negative feedback loops in which rising levels of a hormone feed back to stop its own production — and vice-versa. For example, a negative feedback loop controls production of thyroid hormones. The loop includes the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and thyroid gland.

- Only a few endocrine hormones are controlled by positive feedback loops, in which rising levels of a hormone feed back to stimulate continued production of the hormone. Prolactin, the pituitary hormone that stimulates milk production by mammary glands, is controlled by a positive feedback loop. The loop includes the nipples, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and mammary glands.

9.3 Review Questions

-

-

- Explain how steroid hormones influence target cells.

- How do non-steroid hormones affect target cells?

- Compare and contrast negative and positive feedback loops.

- Outline the way feedback controls the production of thyroid hormones.

- Describe the feedback mechanism that controls milk production by the mammary glands.

- People with a condition called hyperthyroidism produce too much thyroid hormone. What do you think this does to the level of TSH? Explain your answer.

- Which is more likely to maintain homeostasis— negative feedback or positive feedback? Explain your answer.

- Does testosterone bind to receptors on the plasma membrane of target cells or in the cytoplasm of target cells? Explain your answer.

9.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVrlHH14q3o&feature=emb_logo

Great Glands - Your Endocrine System: CrashCourse Biology #33, CrashCourse, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXaDDa3FB5Q&feature=emb_logo

National Geographic | Benefits and Side Effects of Steroids Use 2015, 24 Physic.

Attributions

Figure 9.3.1

L0058274 Glass bottle for ‘Progynon’ pills, United Kingdom, 1928-1948 by Wellcome Collection gallery (2018-03-29)/ Science Museum, London on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC-BY-4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) license.

Figure 9.3.2

Regulation_of_gene_expression_by_steroid_hormone_receptor.svg by Ali Zifan on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 9.3.3

Non-steroid hormone pathway by CK-12 Foundation, Biology for High School is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 9.3.4

Thyroid Negative Feedback Loop by CK-12 Foundation, College Human Biology is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under ![]() • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

Figure 9.3.5

Lactation Positive Feedback Loop by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

References

24 Physic. (2015,July 19). National Geographic | Benefits and side effects of steroids use 2015. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXaDDa3FB5Q&feature=youtu.be

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2016, August 15). Figure 4 Thyroid negative feedback loop [digital image]. In CK-12 College Human Biology (Section 11.3 Endocrine hormones). CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-human-biology/section/11.3/

CK-12 Foundation. (2019, March 5). Figure 3 A non-steroid hormone binds with a receptor on the plasma membrane of a target cell [digital image]. In Flexbook 2.0: CK-12 Biology For High School (Section 13.21 Hormone). CK12. https://flexbooks.ck12.org/cbook/ck-12-biology-flexbook-2.0/section/13.21/primary/lesson/hormones-bio

CrashCourse. (2012, September 10). Great glands - Your endocrine system: CrashCourse Biology #33. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVrlHH14q3o&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, June 21). How do your hormones work? - Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SPRPkLoKp8&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Pills from Pee

The medication pictured in Figure 9.3.1 with the brand name Progynon was a drug used to control the effects of menopause in women. The pills first appeared in 1928 and contained the human sex hormone estrogen. Estrogen secretion declines in women around the time of menopause and may cause symptoms like mood swings and hot flashes. The pills were supposed to ease the symptoms by supplementing estrogen in the body. The manufacturer of Progynon obtained estrogen for the pills from the urine of pregnant women, because it was a cheap source of the hormone. Progynon is still used today to treat menopausal symptoms. Although the drug has been improved over the years, it still contains estrogen, which is an example of an endocrine hormone.

How Do Endocrine Hormones Work?

Endocrine hormones like estrogen are messenger molecules secreted by endocrine glands into the bloodstream. They travel throughout the body in the circulation. Although they reach virtually every cell in the body in this way, each hormone affects only certain cells, called target cells. A target cell is the type of cell on which a hormone has an effect. A target cell is affected by a particular hormone because it has receptor proteins — either on the cell surface or within the cell — that are specific to that hormone. An endocrine hormone travels through the bloodstream until it finds a target cell with a matching receptor to which it can bind. When the hormone binds to the receptor, it causes changes within the cell. The manner in which it changes the cell depends on whether the hormone is a steroid hormone or a non-steroid hormone.

Steroid Hormones

A steroid hormone (such as estrogen) is made of lipids. It is fat soluble, so it can diffuse across a target cell’s plasma membrane, which is also made of lipids. Once inside the cell, a steroid hormone binds with receptor proteins in the cytoplasm. As you can see in Figure 9.3.2, the steroid hormone and its receptor form a complex — called a steroid complex — which moves into the nucleus, where it influences the expression of genes. Examples of steroid hormones include cortisol, which is secreted by the adrenal glands, and sex hormones, which are secreted by the gonads.

Non-Steroid Hormones

A non-steroid hormoneis made of amino acids. It is not fat soluble, so it cannot diffuse across the plasma membrane of a target cell. Instead, it binds to a receptor protein on the cell membrane. In the Figure 9.3.3 diagram, you can see that the binding of the hormone with the receptor activates an enzyme in the cell membrane. The enzyme then stimulates another molecule, called the second messenger, which influences processes inside the cell. Most endocrine hormones are non-steroid hormones. Examples include glucagon and insulin, both produced by the pancreas.

Regulation of Endocrine Hormones

Endocrine hormones regulate many body processes, but what regulates the secretion of endocrine hormones? Most endocrine hormones are controlled by feedback mechanisms. A feedback mechanism is a loop in which a product feeds back to control its own production. Feedback loops may be either negative or positive.

- Most endocrine hormones are regulated by negative feedback loops. Negative feedback keeps the concentration of a hormone within a relatively narrow range, and maintains homeostasis.

- Very few endocrine hormones are regulated by positive feedback loops. Positive feedback causes the concentration of a hormone to become increasingly higher.

Regulation by Negative Feedback

A negative feedback loop controls the synthesis and secretion of hormones by the thyroid gland. This loop includes the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, in addition to the thyroid, as shown in the diagram (Figure 9.3.4). When the levels of thyroid hormones circulating in the blood fall too low, the hypothalamus secretes thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH). This hormone travels directly to the pituitary gland through the thin stalk connecting the two structures. In the pituitary gland, TRH stimulates the pituitary to secrete thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH, in turn, travels through the bloodstream to the thyroid gland, and stimulates it to secrete thyroid hormones. This continues until the blood levels of thyroid hormones are high enough. At that point, the thyroid hormones feed back to stop the hypothalamus from secreting TRH and the pituitary from secreting TSH. Without the stimulation of TSH, the thyroid gland stops secreting its hormones. Eventually, the levels of thyroid hormones in the blood start to fall too low again. When that happens, the hypothalamus releases TRH, and the loop repeats.

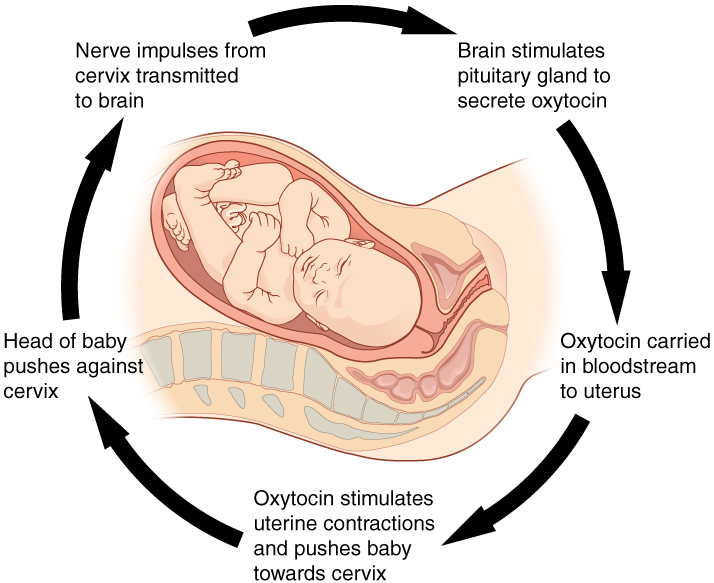

Regulation by Positive Feedback

Prolactin is a non-steroid endocrine hormone secreted by the pituitary gland. One of the functions of prolactin is to stimulate a nursing mother’s mammary glands to produce milk. The regulation of prolactin in the mother is controlled by a positive feedback loop that involves the nipples, hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and mammary glands. Positive feedback begins when a baby suckles on the mother’s nipple. Nerve impulses from the nipple reach the hypothalamus, which stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete prolactin. Prolactin travels in the blood to the mammary glands and stimulates them to produce milk. The release of milk causes the baby to continue suckling, which causes more prolactin to be secreted and more milk to be produced. The positive feedback loop continues until the baby stops suckling at the breast.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Anabolic steroids are synthetic versions of the naturally occurring male sex hormone testosterone. Male hormones have androgenic (or masculinizing) effects, but they also have anabolic (or muscle-building) effects. The anabolic effects are the reason that synthetic steroids are used by athletes. In addition to building muscles, they also accelerate the development of bones and red blood cells, increase endurance so athletes can train harder and longer, and speed up muscle recovery. Unfortunately, these benefits of steroid use come with costs. If you ever consider taking anabolic steroids to build muscles and improve athletic performance, consider the following myths and corresponding realities.

Myth |

Reality |

| "Steroids are safe." | Steroid use may cause several serious side effects. Prolonged use may increase the risk of liver cancer, heart disease, and high blood pressure. |

| "Steroids will not stunt your growth." | Teens who take steroids before they have finished growing in height may have their growth stunted so they remain shorter throughout life than they would otherwise have been. Such stunting occurs because steroids increase the rate at which skeletal maturity is reached. Once skeletal maturity occurs, additional growth in height is impossible. |

| "Steroids do not cause drug dependency." | Steroid use may cause dependency, as evidenced by the negative effects of stopping steroid use. These negative effects may include insomnia, fatigue, and depressed mood, among others. |

| "There is no such thing as 'roid rage.'" | Steroid use has been shown to increase aggressiveness in some people. It has also been implicated in a number of violent acts committed by people who had not demonstrated violent tendencies until they started using steroids. |

| "Only males use steroids." | Although steroid use is more common in males than females, some females also use steroids. They use them to build muscle and improve physical performance, generally either for athletic competition or for self-defense. |

9.3 Summary

- Endocrine hormones are messenger molecules secreted by endocrine glands into the bloodstream. They travel throughout the body but affect only certain cells, called target cells, which have receptors specific to particular hormones.

- Steroid hormones such as estrogen are endocrine hormones made of lipids that cross plasma membranes and bind to receptors inside target cells. The hormone-receptor complexes then move into the nucleus, where they influence gene expression.

- Non-steroid hormones (such as insulin) are endocrine hormones made of amino acids that bind to receptors on the surface of target cells. This activates an enzyme in the plasma membrane, and the enzyme controls a second messenger molecule, which influences cell processes.