16.2 Organs of Excretion

Getting Rid of Wastes

The many chimneys on these houses are one way that the inhabitants of the home get rid of the wastes they produce. The chimneys expel waste gases that are created when they burn fuel in their furnace or fireplace. Think about the other wastes that people create in their homes and how we dispose of them. Solid trash and recyclables may go to the curb in a trash can, or in a recycling bin for pick up and transport to a landfill or recycling centre. Wastewater from sinks, showers, toilets, and the washing machine goes into a main sewer pipe and out of the house to join the community’s sanitary sewer system.

Like a busy home, your body also produces a lot of wastes that must be eliminated. Like a home, the way your body gets rid of wastes depends on the nature of the waste products. Some human body wastes are gases, some are solids, and some are in a liquid state. Getting rid of body wastes is called excretion, and there are a number of different organs of excretion in the human body.

Excretion

Excretion is the process of removing wastes and excess water from the body. It is an essential process in all living things, and it is one of the major ways the human body maintains homeostasis. It also helps prevent damage to the body. Wastes include by-products of metabolism — some of which are toxic — and other non-useful materials, such as used up and broken down components. Some of the specific waste products that must be excreted from the body include carbon dioxide from cellular respiration, ammonia and urea from protein catabolism, and uric acid from nucleic acid catabolism.

Excretory Organs

Organs of excretion include the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys (see Figure 16.2.2). Together, these organs make up the excretory system. They all excrete wastes, but they don’t work together in the same way that organs do in most other body systems. Each of the excretory organs “does its own thing” more-or-less independently of the others, but all are necessary to successfully excrete the full range of wastes from the human body.

Figure 16.2.2 Internal organs of excretion are identified in this illustration. They include the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys.

Skin

The skin is part of the integumentary system, but it also plays a role in excretion through the production of sweat by sweat glands in the dermis. Although the main role of sweat production is to cool the body and maintain temperature homeostasis, sweating also eliminates excess water and salts, as well as a small amount of urea. When sweating is copious, as in Figure 16.2.3, ingestion of salts and water may be helpful to maintain homeostasis in the body.

Liver

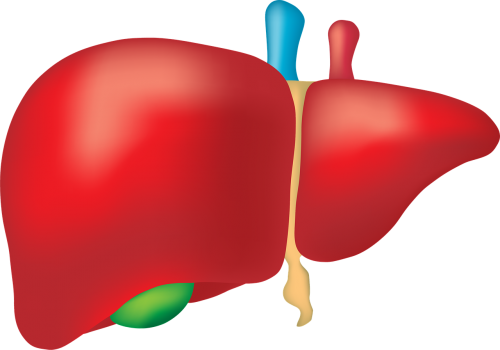

The liver (shown in Figure 16.2.4) has numerous major functions, including secreting bile for digestion of lipids, synthesizing many proteins and other compounds, storing glycogen and other substances, and secreting endocrine hormones. In addition to all of these functions, the liver is a very important organ of excretion. The liver breaks down many substances in the blood, including toxins. For example, the liver transforms ammonia — a poisonous by-product of protein catabolism — into urea, which is filtered from the blood by the kidneys and excreted in urine. The liver also excretes in its bile the protein bilirubin, a byproduct of hemoglobin catabolism that forms when red blood cells die. Bile travels to the small intestine and is then excreted in feces by the large intestine.

Large Intestine

The large intestine is an important part of the digestive system and the final organ in the gastrointestinal tract. As an organ of excretion, its main function is to eliminate solid wastes that remain after the digestion of food and the extraction of water from indigestible matter in food waste. The large intestine also collects wastes from throughout the body. Bile secreted into the gastrointestinal tract, for example, contains the waste product bilirubin from the liver. Bilirubin is a brown pigment that gives human feces its characteristic brown colour.

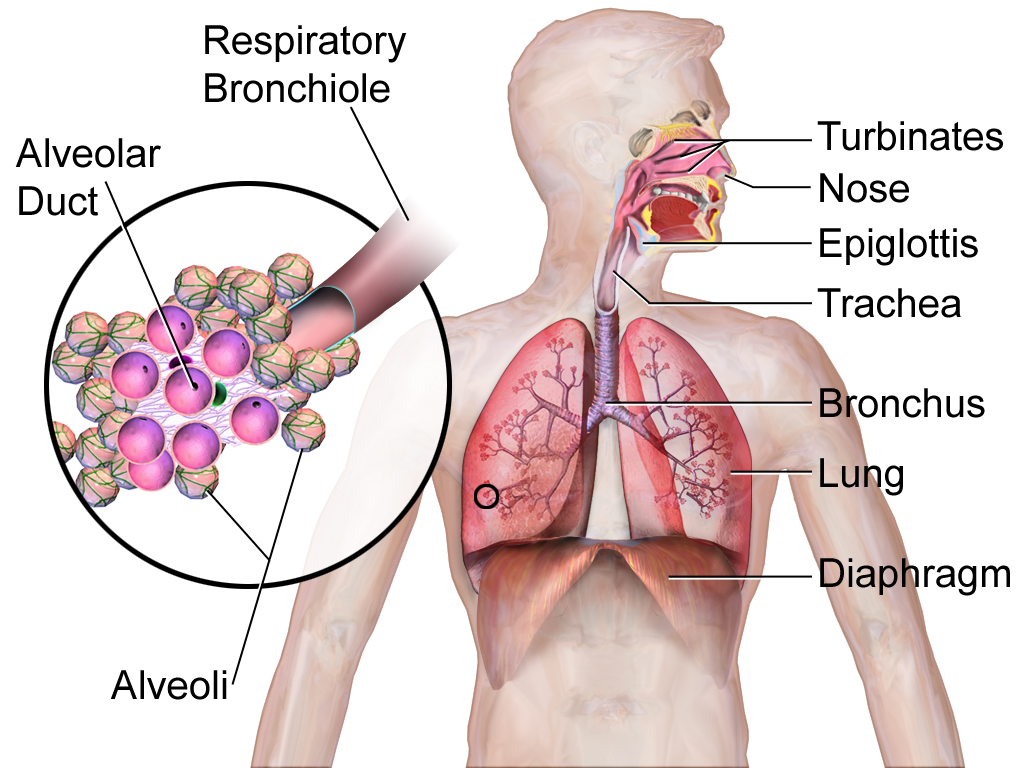

Lungs

The lungs are part of the respiratory system (shown in Figure 16.2.5), but they are also important organs of excretion. They are responsible for the excretion of gaseous wastes from the body. The main waste gas excreted by the lungs is carbon dioxide, which is a waste product of cellular respiration in cells throughout the body. Carbon dioxide is diffused from the blood into the air in the tiny air sacs called alveoli in the lungs (shown in the inset diagram). By expelling carbon dioxide from the blood, the lungs help maintain acid-base homeostasis. In fact, it is the pH of blood that controls the rate of breathing. Water vapor is also picked up from the lungs and other organs of the respiratory tract as the exhaled air passes over their moist linings, and the water vapor is excreted along with the carbon dioxide. Trace levels of some other waste gases are exhaled, as well.

Kidneys

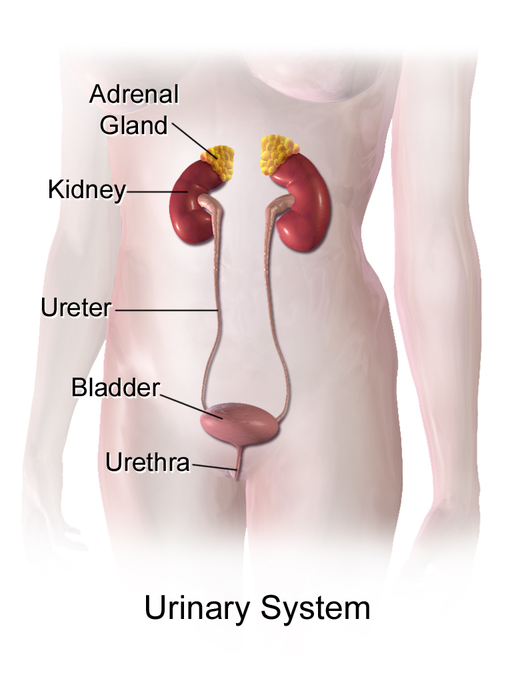

The paired kidneys are often considered the main organs of excretion. The primary function of the kidneys is the elimination of excess water and wastes from the bloodstream by the production of the liquid waste known as urine. The main structural and functional units of the kidneys are tiny structures called nephrons. Nephrons filter materials out of the blood, return to the blood what is needed, and excrete the rest as urine. As shown in Figure 16.2.6, the kidneys are organs of the urinary system, which also includes the ureters, bladder, and urethra — organs that transport, store, and eliminate urine, respectively.

By producing and excreting urine, the kidneys play vital roles in body-wide homeostasis. They maintain the correct volume of extracellular fluid, which is all the fluid in the body outside of cells, including the blood and lymph. The kidneys also maintain the correct balance of salts and pH in extracellular fluid. In addition, the kidneys function as endocrine glands, secreting hormones into the blood that control other body processes. You can read much more about the kidneys in section 16.4 Kidneys.

16.2 Summary

- Excretion is the process of removing wastes and excess water from the body. It is an essential process in all living things and a major way the human body maintains homeostasis.

- Organs of excretion include the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys. All of them excrete wastes, and together they make up the excretory system.

- The skin plays a role in excretion through the production of sweat by sweat glands. Sweating eliminates excess water and salts, as well as a small amount of urea, a byproduct of protein catabolism.

- The liver is a very important organ of excretion. The liver breaks down many substances in the blood, including toxins. The liver also excretes bilirubin — a waste product of hemoglobin catabolism — in bile. Bile then travels to the small intestine, and is eventually excreted in feces by the large intestine.

- The main excretory function of the large intestine is to eliminate solid waste that remains after food is digested and water is extracted from the indigestible matter. The large intestine also collects and excretes wastes from throughout the body, including bilirubin in bile.

- The lungs are responsible for the excretion of gaseous wastes, primarily carbon dioxide from cellular respiration in cells throughout the body. Exhaled air also contains water vapor and trace levels of some other waste gases.

- The paired kidneys are often considered the main organs of excretion. Their primary function is the elimination of excess water and wastes from the bloodstream by the production of urine. The kidneys contain tiny structures called nephrons that filter materials out of the blood, return to the blood what is needed, and excrete the rest as urine. The kidneys are part of the urinary system, which also includes the ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra.

16.2 Review Questions

- What is excretion, and what is its significance?

-

- Describe the excretory functions of the liver.

- What are the main excretory functions of the large intestine?

- List organs of the urinary system.

- Describe the physical states in which the wastes from the human body are excreted.

- Give one example of why ridding the body of excess water is important.

- What gives feces its brown colour? Why is that substance produced?

16.2 Explore More

Why Can We Regrow A Liver (But Not A Limb)? MITK12Videos, 2015.

Are Sports Drinks Good For You? | Fit or Fiction, POPSUGAR Fitness, 2014.

Why do we sweat? – John Murnan, TED-Ed, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 16.2.1

Chimneys/ Kingston upon Hull, England [photo] by Angela Baker on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 16.2.2

- Sweat or rain? by Kullez on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/).

- Kidney front – white from www.medicalgraphics.de is used under a CC BY-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/) license.

- File:Liver Cirrhosis.png by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

- File:Human lungs.png by Sharanyaudupa on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

- Tags: Offal Marking Medical Intestine Liver by Elionas2 on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay license (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.2.3

gym_room_fitness_equipment_cardiovascular_exercise_elliptical_bike_cardio_training_sports_equipment_bodybuilding-825364 from Pxhere is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

Figure 16.2.4

Tags: Liver Organ Anatomy by zachvanstone8 on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.2.5

Lung_and_diaphragm by Terese Winslow/ National Cancer Institute on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.2.6

512px-Urinary_System_(Female) by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

MITK12Videos. (2015, June 4). Why can we regrow a liver (but not a limb)? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erMCADOJcHk&feature=youtu.be

POPSUGAR Fitness. (2014, February 7). Are sports drinks good for you? | Fit or Fiction. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SeK0zFB9yHg&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, May 15). Why do we sweat? – John Murnan. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fctH_1NuqCQ&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a diagram of loose fibrous connective tissue. There are a few, widely spaced cells called fibroblasts. There are large collagen fibers and thin elastin fibers running through the tissue in a widely spaced disorganized manner.

The ability of an organism to maintain constant internal conditions despite external changes.

The chemical processes that occur in a living organism to sustain life.

A set of metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert biochemical energy from nutrients into adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

Image shows a diagram of dense fibrous connective tissue. There are many tightly packed layers of collagen fibers with embedded fibroblasts.

Image shows a microscopic view of dense fibrous connective tissue. The parallel strands of collagen show up as pink horizontal fibers. The fibroblasts sit in between fibers and are stained a dark purple.

Image shows both a diagram and microscopic view of each of the three types of cartilage: Hyaline cartilage, which contains chondrocytes in paired lacunae and a smooth-looking matrix; Fibrocartilage with looks marbled due to many layers of collagen, and elastic cartilage which irregular, containing both collagen and elastin fibers.

visible part of a nail that is external to the skin

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Doing the ‘Fly

The swimmer in the Figure 13.3.1 photo is doing the butterfly stroke, a swimming style that requires the swimmer to carefully control his breathing so it is coordinated with his swimming movements. Breathing is the process of moving air into and out of the lungs, which are the organs in which gas exchange takes place between the atmosphere and the body. Breathing is also called ventilation, and it is one of two parts of the life-sustaining process of respiration. The other part is gas exchange. Before you can understand how breathing is controlled, you need to know how breathing occurs.

How Breathing Occurs

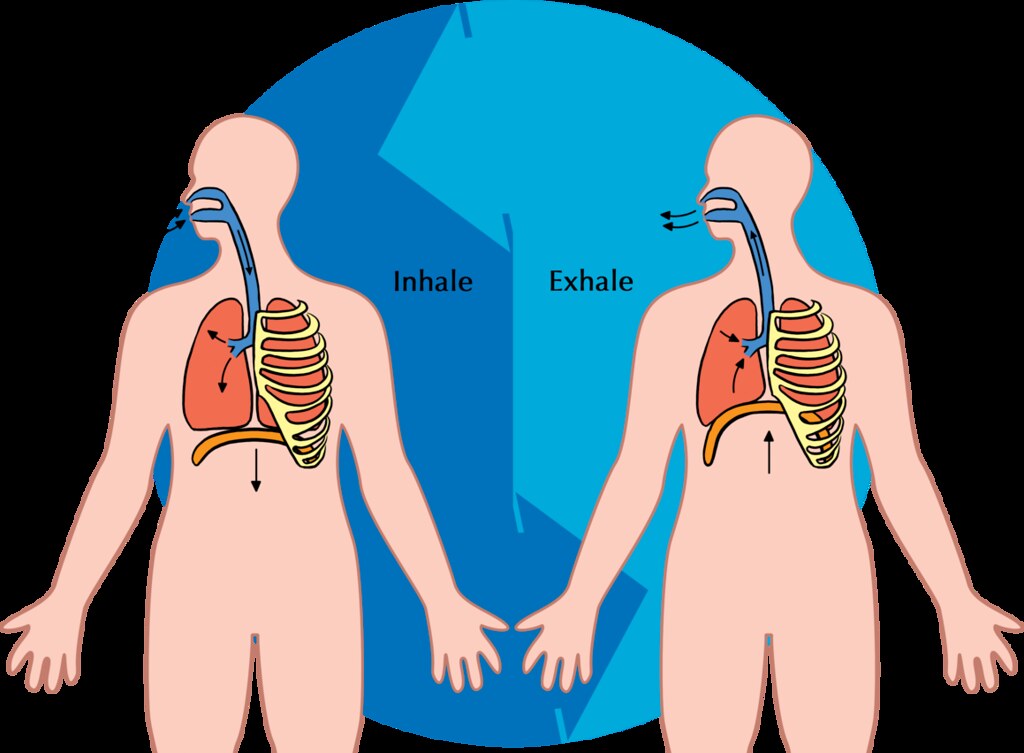

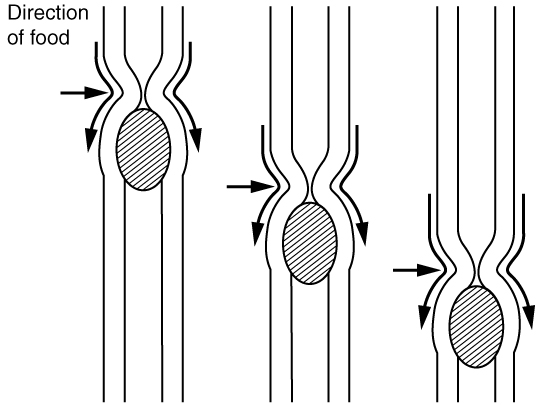

Breathing is a two-step process that includes drawing air into the lungs, or inhaling, and letting air out of the lungs, or exhaling. Both processes are illustrated in Figure 13.3.2.

Inhaling

Inhaling is an active process that results mainly from contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm, shown in Figure 13.3.2. The diaphragm is a large, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs that separates the thoracic (chest) and abdominal cavities. When the diaphragm contracts it moves down causing the thoracic cavity to expand, and the contents of the abdomen to be pushed downward. Other muscles — such as intercostal muscles between the ribs — also contribute to the process of inhalation, especially when inhalation is forced, as when taking a deep breath. These muscles help increase thoracic volume by expanding the ribs outward. The increase in thoracic volume creates a decrease in thoracic air pressure. With the chest expanded, there is lower air pressure inside the lungs than outside the body, so outside air flows into the lungs via the respiratory tract according the the pressure gradient (high pressure flows to lower pressure).

Exhaling

Exhaling involves the opposite series of events. The diaphragm relaxes, so it moves upward and decreases the volume of the thorax. Air pressure inside the lungs increases, so it is higher than the air pressure outside the lungs. Exhalation, unlike inhalation, is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs. With the change in air pressure, the lungs contract to their pre-inflated size, forcing out the air they contain in the process. Air flows out of the lungs, similar to the way air rushes out of a balloon when it is released. If exhalation is forced, internal intercostal and abdominal muscles may help move the air out of the lungs.

Control of Breathing

Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously, as well as unconsciously. Think about using your breath to blow up a balloon. You take a long, deep breath, and then you exhale the air as forcibly as you can into the balloon. Both the inhalation and exhalation are consciously controlled.

Conscious Control of Breathing

You can control your breathing by holding your breath, slowing your breathing, or hyperventilating, which is breathing more quickly and shallowly than necessary. You can also exhale or inhale more forcefully or deeply than usual. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities besides blowing up balloons, including swimming, speech training, singing, playing many different musical instruments (Figure 13.3.3), and doing yoga, to name just a few.

There are limits on the conscious control of breathing. For example, it is not possible for a healthy person to voluntarily stop breathing indefinitely. Before long, there is an irrepressible urge to breathe. If you were able to stop breathing for a long enough time, you would lose consciousness. The same thing would happen if you were to hyperventilate for too long. Once you lose consciousness so you can no longer exert conscious control over your breathing, involuntary control of breathing takes over.

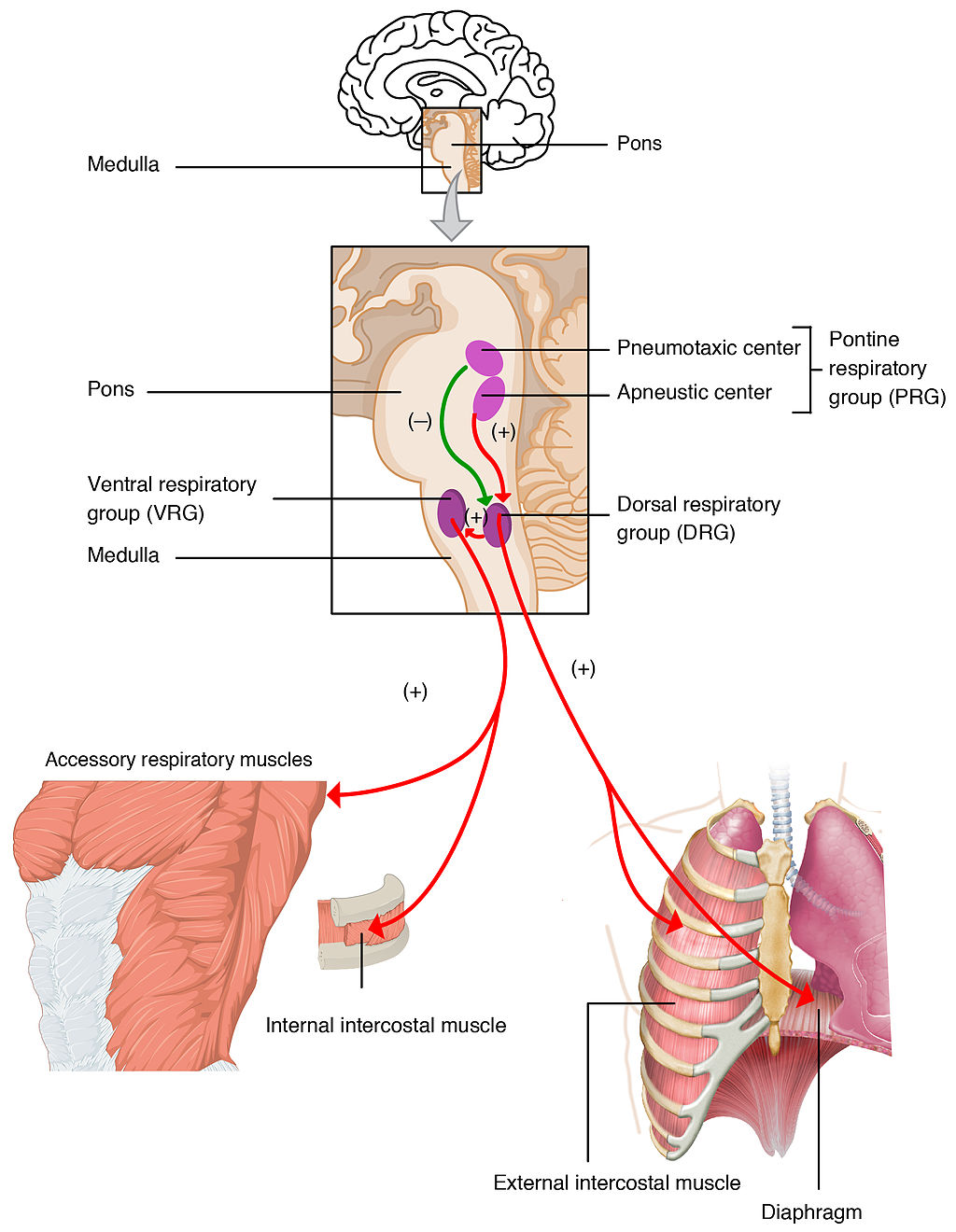

Unconscious Control of Breathing

Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem (see Figure 13.3.4). The respiratory centers automatically and continuously regulate the rate of breathing based on the body’s needs. These are determined mainly by blood acidity, or pH. When you exercise, for example, carbon dioxide levels increase in the blood, because of increased cellular respiration by muscle cells. The carbon dioxide reacts with water in the blood to produce carbonic acid, making the blood more acidic, so pH falls. The drop in pH is detected by chemoreceptors in the medulla. Blood levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide, in addition to pH, are also detected by chemoreceptors in major arteries, which send the “data” to the respiratory centers. The latter respond by sending nerve impulses to the diaphragm, “telling” it to contract more quickly so the rate of breathing speeds up. With faster breathing, more carbon dioxide is released into the air from the blood, and blood pH returns to the normal range.

The opposite events occur when the level of carbon dioxide in the blood becomes too low and blood pH rises. This may occur with involuntary hyperventilation, which can happen in panic attacks, episodes of severe pain, asthma attacks, and many other situations. When you hyperventilate, you blow off a lot of carbon dioxide, leading to a drop in blood levels of carbon dioxide. The blood becomes more basic (alkaline), causing its pH to rise.

Nasal vs. Mouth Breathing

Nasal breathing is breathing through the nose rather than the mouth, and it is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing. The hair-lined nasal passages do a better job of filtering particles out of the air before it moves deeper into the respiratory tract. The nasal passages are also better at warming and moistening the air, so nasal breathing is especially advantageous in the winter when the air is cold and dry. In addition, the smaller diameter of the nasal passages creates greater pressure in the lungs during exhalation. This slows the emptying of the lungs, giving them more time to extract oxygen from the air.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Drowning is defined as respiratory impairment from being in or under a liquid. It is further classified according to its outcome into: death, ongoing health problems, or no ongoing health problems (full recovery). Four hundred Canadians die annually from drowning, and drowning is one of the leading causes of death in children under the age of five. There are some potentially dangerous myths about drowning, and knowing what they are might save your life or the life of a loved one, especially a child.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| "People drown when they aspirate water into their lungs." | Generally, in the early stages of drowning, very little water enters the lungs. A small amount of water entering the trachea causes a muscular spasm in the larynx that seals the airway and prevents the passage of water into the lungs. This spasm is likely to last until unconsciousness occurs. |

| "You can tell when someone is drowning because they will shout for help and wave their arms to attract attention." | The muscular spasm that seals the airway prevents the passage of air, as well as water, so a person who is drowning is unable to shout or call for help. In addition, instinctive reactions that occur in the final minute or so before a drowning person sinks under the water may look similar to calm, safe behavior. The head is likely to be low in the water, tilted back, with the mouth open. The person may have uncontrolled movements of the arms and legs, but they are unlikely to be visible above the water. |

| "It is too late to save a person who is unconscious in the water." | An unconscious person rescued with an airway still sealed from the muscular spasm of the larynx stands a good chance of full recovery if they start receiving CPR within minutes. Without water in the lungs, CPR is much more effective. Even if cardiac arrest has occurred so the heart is no longer beating, there is still a chance of recovery. The longer the brain goes without oxygen, however, the more likely brain cells are to die. Brain death is likely after about six minutes without oxygen, except in exceptional circumstances, such as young people drowning in very cold water. There are examples of children surviving, apparently without lasting ill effects, for as long as an hour in cold water. Rescuers retrieving a child from cold water should attempt resuscitation even after a protracted period of immersion. |

| "If someone is drowning, you should start administering CPR immediately, even before you try to get the person out of the water." | Removing a drowning person from the water is the first priority, because CPR is ineffective in the water. The goal should be to bring the person to stable ground as quickly as possible and then to start CPR. |

| "You are unlikely to drown unless you are in water over your head." | Depending on circumstances, people have drowned in as little as 30 mm (about 1 ½ in.) of water. Inebriated people or those under the influence of drugs, for example, have been known to have drowned in puddles. Hundreds of children have drowned in the water in toilets, bathtubs, basins, showers, pails, and buckets (see Figure 13.3.5). |

13.3 Summary

- Breathing, or ventilation, is the two-step process of drawing air into the lungs (inhaling) and letting air out of the lungs (exhaling). Inhalation is an active process that results mainly from contraction of a muscle called the diaphragm. Exhalation is typically a passive process that occurs mainly due to the elasticity of the lungs when the diaphragm relaxes.

- Breathing is one of the few vital bodily functions that can be controlled consciously, as well as unconsciously. Conscious control of breathing is common in many activities, including swimming and singing. There are limits on the conscious control of breathing, however. If you try to hold your breath, for example, you will soon have an irrepressible urge to breathe.

- Unconscious breathing is controlled by respiratory centers in the medulla and pons of the brainstem. They respond to variations in blood pH by either increasing or decreasing the rate of breathing as needed to return the pH level to the normal range.

- Nasal breathing is generally considered to be superior to mouth breathing because it does a better job of filtering, warming, and moistening incoming air. It also results in slower emptying of the lungs, which allows more oxygen to be extracted from the air.

- Drowning is a major cause of death in Canada, in particular in children under the age of five. It is important to supervise small children when they are playing in, around, or with water.

13.3 Review Questions

- Define breathing.

-

- Give examples of activities in which breathing is consciously controlled.

- Explain how unconscious breathing is controlled.

- Young children sometimes threaten to hold their breath until they get something they want. Why is this an idle threat?

- Why is nasal breathing generally considered superior to mouth breathing?

- Give one example of a situation that would cause blood pH to rise excessively. Explain why this occurs.

13.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl4cU9sG_08

How breathing works - Nirvair Kaur, TED-Ed, 2012.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDtKBXOEsoM

How do ventilators work? - Alex Gendler, TED-Ed, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFnGhrC_3Gs&feature=emb_logo

How I held my breath for 17 minutes | David Blaine, TED, 2010.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vca6DyFqt4c&feature=emb_logo

The Ultimate Relaxation Technique: How To Practice Diaphragmatic Breathing For Beginners, Kai Simon, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 13.3.1

US_Marines_butterfly_stroke by Cpl. Jasper Schwartz from U.S. Marine Corps on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.3.2

Inhale Exhale/Breathing cycle by Siyavula Education on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 13.3.3

Trumpet/ Frenchmen Street [photo] by Morgan Petroski on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 13.3.4

Respiratory_Centers_of_the_Brain by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 13.3.5

Lily & Ava in the Kiddie Pool by mob mob on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.20 Respiratory centers of the brain [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-3-the-process-of-breathing

Kai Simon. (2015, January 11). The ultimate relaxation technique: How to practice diaphragmatic breathing for beginners. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vca6DyFqt4c&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2010, January 19). How I held my breath for 17 minutes | David Blaine. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XFnGhrC_3Gs&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2012, October 4). How breathing works - Nirvair Kaur. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kl4cU9sG_08&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, May 21). How do ventilators work? - Alex Gendler. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yDtKBXOEsoM&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a table with illustrations showing the variation that exists within pea plans. The peas can either be smooth or wrinkled. The peas can either be green or yellow. The flowers could either be white or purple. The pods could either be smooth or constricted. The pods could either be yellow or green. The plants could either be short or tall. The plants could either end with flowers or end with foliage.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Oxygen Bar

Belly up to the bar and get your favorite... oxygen? That’s right — in some cities, you can get a shot of pure oxygen, with or without your choice of added flavors. Bar patrons inhale oxygen through a plastic tube inserted into their nostrils, paying up to a dollar per minute to inhale the pure gas. Proponents of the practice claim that breathing in extra oxygen will remove toxins from the body, strengthen the immune system, enhance concentration and alertness, increase energy, and even cure cancer! These claims, however, have not been substantiated by controlled scientific studies. Normally, blood leaving the lungs is almost completely saturated with oxygen, even without the use of extra oxygen, so it’s unlikely that a higher concentration of oxygen in air inside the lungs would lead to significantly greater oxygenation of the blood. Oxygen enters the blood in the lungs as part of the process of gas exchange.

What is Gas Exchange?

Gas exchange is the biological process through which gases are transferred across cell membranes to either enter or leave the blood. Oxygen is constantly needed by cells for aerobic cellular respiration, and the same process continually produces carbon dioxide as a waste product. Gas exchange takes place between the blood and cells throughout the body, with oxygen leaving the blood and entering the cells, and carbon dioxide leaving the cells and entering the blood. Gas exchange also takes place between the blood and the air in the lungs, with oxygen entering the blood from the inhaled air inside the lungs, and carbon dioxide leaving the blood and entering the air to be exhaled from the lungs.

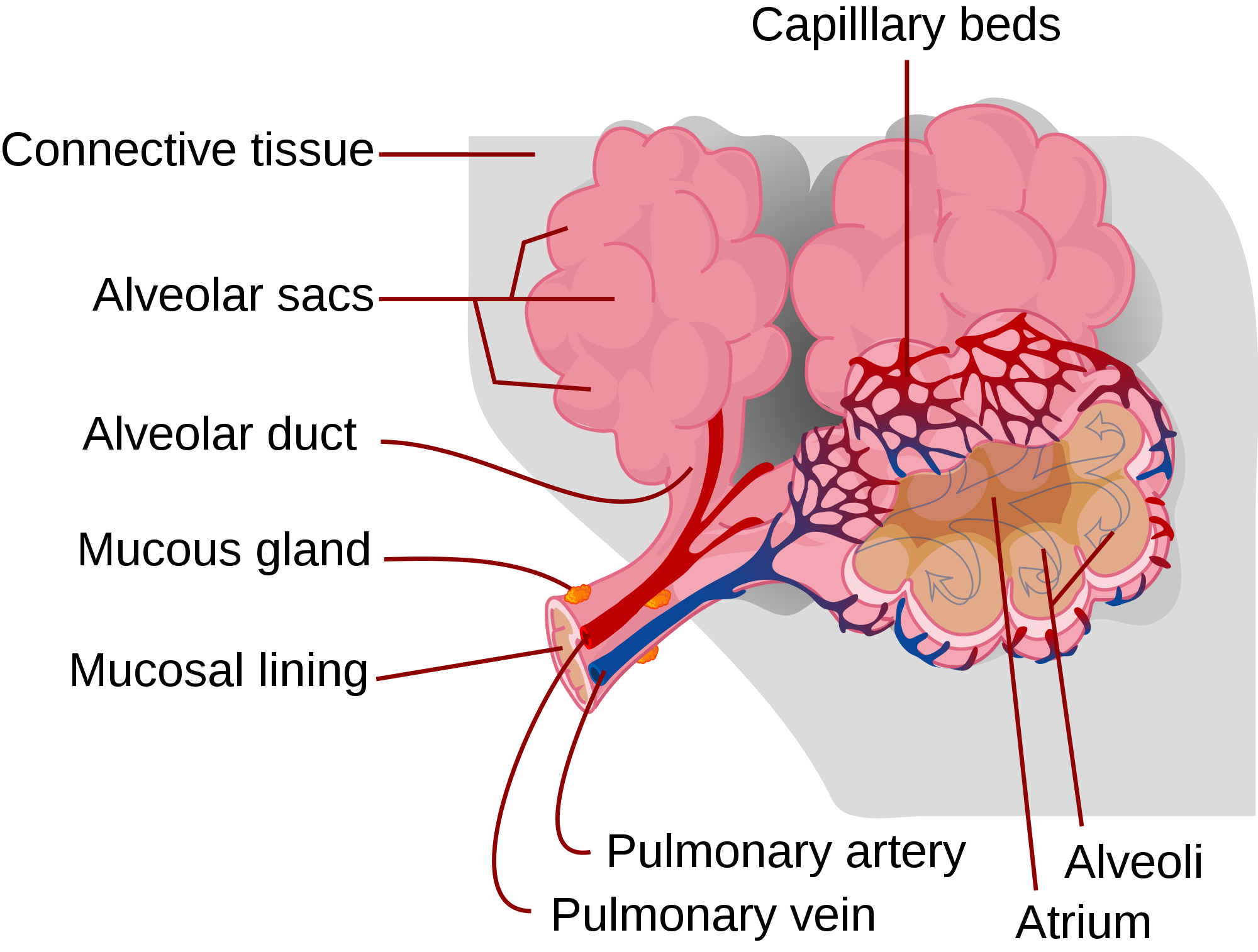

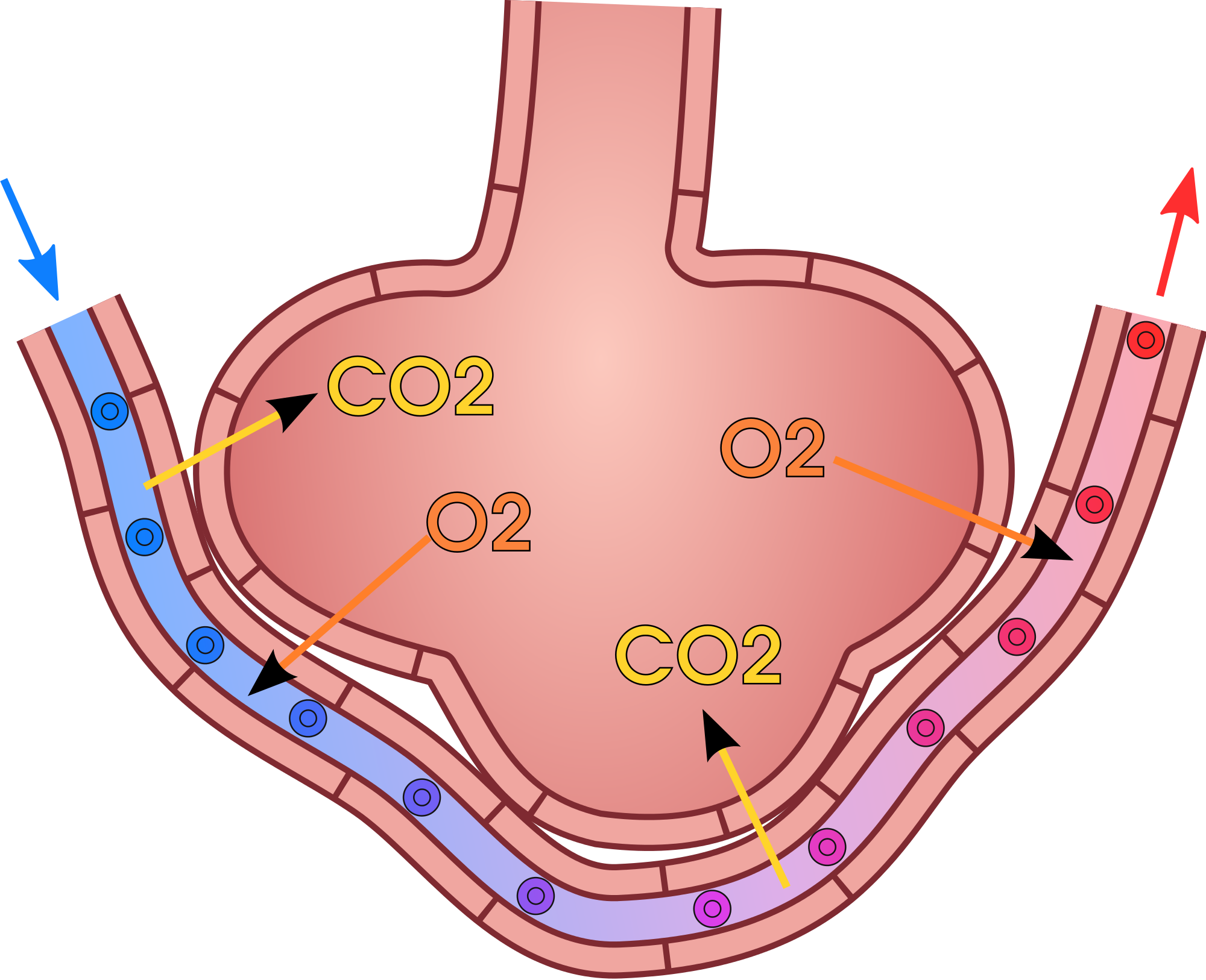

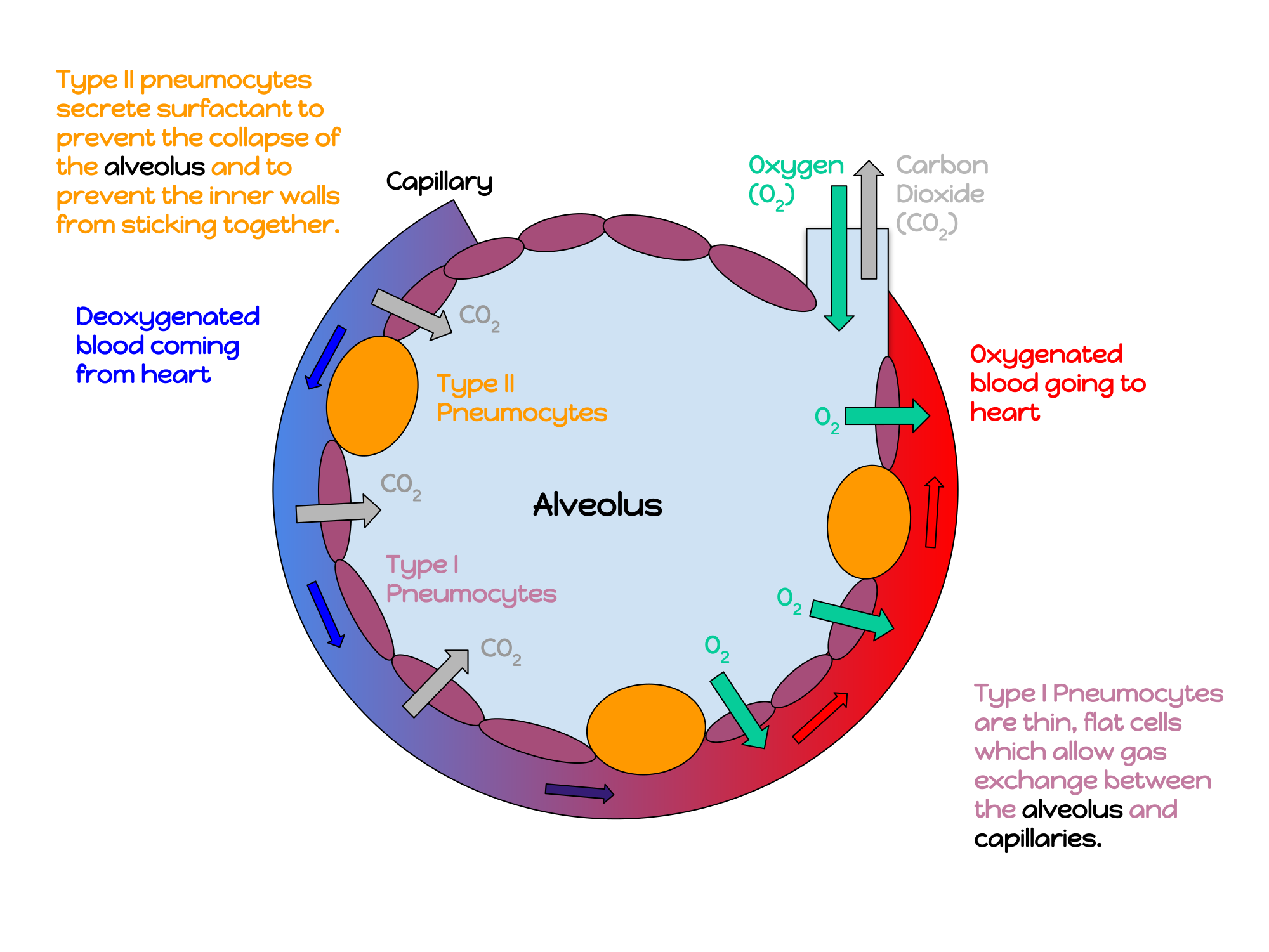

Gas Exchange in the Lungs

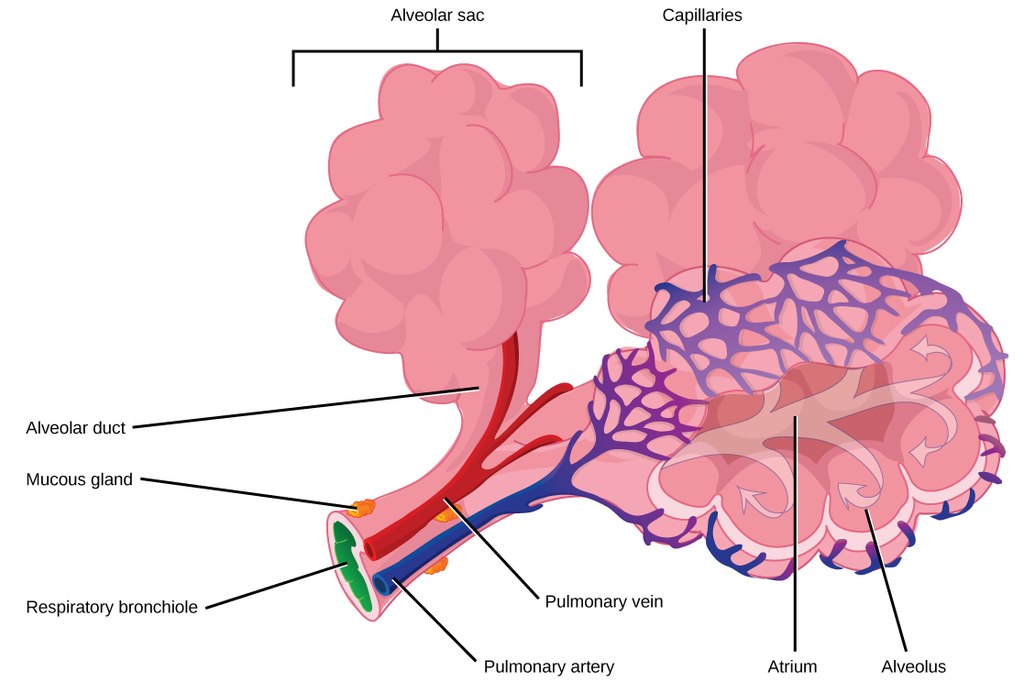

Alveoli are the basic functional units of the lungs where gas exchange takes place between the air and the blood. Alveoli (singular, alveolus) are tiny air sacs that consist of connective and epithelial tissues. The connective tissue includes elastic fibres that allow alveoli to stretch and expand as they fill with air during inhalation. During exhalation, the fibres allow the alveoli to spring back and expel the air. Special cells in the walls of the alveoli secrete a film of fatty substances called surfactant. This substance prevents the alveolar walls from collapsing and sticking together when air is expelled. Other cells in alveoli include macrophages, which are mobile scavengers that engulf and destroy foreign particles that manage to reach the lungs in inhaled air.

As shown in Figure 13.4.2, alveoli are arranged in groups like clusters of grapes. Each alveolus is covered with epithelium that is just one cell thick. It is surrounded by a bed of pulmonary capillaries, each of which has a wall of epithelium just one cell thick. As a result, gases must cross through only two cells to pass between an alveolus and its surrounding capillaries.

The pulmonary artery (also shown in Figure 13.4.2) carries deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs. Then, the blood travels through the pulmonary capillary beds, where it picks up oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. The oxygenated blood then leaves the lungs and travels back to the heart through pulmonary veins. There are four pulmonary veins (two for each lung), and all four carry oxygenated blood to the heart. From the heart, the oxygenated blood is then pumped to cells throughout the body.

Mechanism of Gas Exchange

Gas exchange occurs by diffusion across cell membranes. Gas molecules naturally move down a concentration gradient from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. This is a passive process that requires no energy. To diffuse across cell membranes, gases must first be dissolved in a liquid. Oxygen and carbon dioxide are transported around the body dissolved in blood. Both gases bind to the protein hemoglobin in red blood cells, although oxygen does so more effectively than carbon dioxide. Some carbon dioxide also dissolves in blood plasma.

As shown in Figure 13.4.3, oxygen in inhaled air diffuses into a pulmonary capillary from the alveolus. Carbon dioxide in the blood diffuses in the opposite direction. The carbon dioxide can then be exhaled from the body.

Gas exchange by diffusion depends on having a large surface area through which gases can pass. Although each alveolus is tiny, there are hundreds of millions of them in the lungs of a healthy adult, so the total surface area for gas exchange is huge. It is estimated that this surface area may be as great as 100 m2 (or approximately 1,076 ft²). Often we think of lungs as balloons, but this type of structure would have very limited surface area and there wouldn't be enough space for blood to interface with the air in the alveoli. The structure alveoli take in the lungs is more like a giant mass of soap bubbles — millions of tiny little chambers making up one large mass — this is what increases surface area giving blood lots of space to come into close enough contact to exchange gases by diffusion.

Gas exchange by diffusion also depends on maintaining a steep concentration gradient for oxygen and carbon dioxide. Continuous blood flow in the capillaries and constant breathing maintain this gradient.

- Each time you inhale, there is a greater concentration of oxygen in the air in the alveoli than there is in the blood in the pulmonary capillaries. As a result, oxygen diffuses from the air inside the alveoli into the blood in the capillaries. Carbon dioxide, in contrast, is more concentrated in the blood in the pulmonary capillaries than it is in the air inside the alveoli. As a result, carbon dioxide diffuses in the opposite direction.

- The cells of the body have a much lower concentration of oxygen than does the oxygenated blood that reaches them in peripheral capillaries, which are the capillaries that supply tissues throughout the body. As a result, oxygen diffuses from the peripheral capillaries into body cells. The opposite is true of carbon dioxide. It has a much higher concentration in body cells than it does in the blood of the peripheral capillaries. Thus, carbon dioxide diffuses from body cells into the peripheral capillaries.

13.4 Summary

- Gas exchange is the biological process through which gases are transferred across cell membranes to either enter or leave the blood. Gas exchange takes place continuously between the blood and cells throughout the body, and also between the blood and the air inside the lungs.

- Gas exchange in the lungs takes place in alveoli, which are tiny air sacs surrounded by networks of capillaries. The pulmonary artery carries deoxygenated blood from the heart to the lungs, where it travels through pulmonary capillaries, picking up oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. The oxygenated blood then leaves the lungs through pulmonary veins.

- Gas exchange occurs by diffusion across cell membranes. Gas molecules naturally move down a concentration gradient from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. This is a passive process that requires no energy.

- Gas exchange by diffusion depends on the large surface area provided by the hundreds of millions of alveoli in the lungs. It also depends on a steep concentration gradient for oxygen and carbon dioxide. This gradient is maintained by continuous blood flow and constant breathing.

13.4 Review Questions

- What is gas exchange?

- Summarize the flow of blood into and out of the lungs for gas exchange.

-

- Describe the mechanism by which gas exchange takes place.

- Identify the two main factors upon which gas exchange by diffusion depends.

- If the concentration of oxygen were higher inside of a cell than outside of it, which way would the oxygen flow? Explain your answer.

- Why is it important that the walls of the alveoli are only one cell thick?

13.4 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRpwdwm06Ic&feature=emb_logo

Oxygen movement from alveoli to capillaries | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy, khanacademymedicine, 2013.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmgIqVwytwA&feature=emb_logo

About Carbon Monoxide and Carbon Monoxide Poisoning, EMDPrepare, 2009.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GVU_zANtroE

Oxygen’s surprisingly complex journey through your body - Enda Butler, TED-Ed, 2017.

Attributions

Figure 13.4.1

Oxygen Bar by Farrukh on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

Figure 13.4.2

Alveolus_diagram.svg by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.4.3

Gas_exchange_in_the_aveolus.svg by domdomegg on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

References

EMDPrepare. (2009, December 21). About carbon monoxide and carbon monoxide poisoning. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmgIqVwytwA&feature=youtu.be

khanacademymedicine. (2013, February 25). Oxygen movement from alveoli to capillaries | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRpwdwm06Ic&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2017, April 13). Oxygen’s surprisingly complex journey through your body - Enda Butler. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GVU_zANtroE&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Seeing Your Breath

Why can you “see your breath” on a cold day? The air you exhale through your nose and mouth is warm like the inside of your body. Exhaled air also contains a lot of water vapor, because it passes over moist surfaces from the lungs to the nose or mouth. The water vapor in your breath cools suddenly when it reaches the much colder outside air. This causes the water vapor to condense into a fog of tiny droplets of liquid water. You release water vapor and other gases from your body through the process of respiration.

What is Respiration?

Respiration is the life-sustaining process in which gases are exchanged between the body and the outside atmosphere. Specifically, oxygen moves from the outside air into the body; and water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other waste gases move from inside the body to the outside air. Respiration is carried out mainly by the respiratory system. It is important to note that respiration by the respiratory system is not the same process as cellular respiration —which occurs inside cells — although the two processes are closely connected. Cellular respiration is the metabolic process in which cells obtain energy, usually by “burning” glucose in the presence of oxygen. When cellular respiration is aerobic, it uses oxygen and releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. Respiration by the respiratory system supplies the oxygen needed by cells for aerobic cellular respiration, and removes the carbon dioxide produced by cells during cellular respiration.

Respiration by the respiratory system actually involves two subsidiary processes. One process is ventilation, or breathing. Ventilation is the physical process of conducting air to and from the lungs. The other process is gas exchange. This is the biochemical process in which oxygen diffuses out of the air and into the blood, while carbon dioxide and other waste gases diffuse out of the blood and into the air. All of the organs of the respiratory system are involved in breathing, but only the lungs are involved in gas exchange.

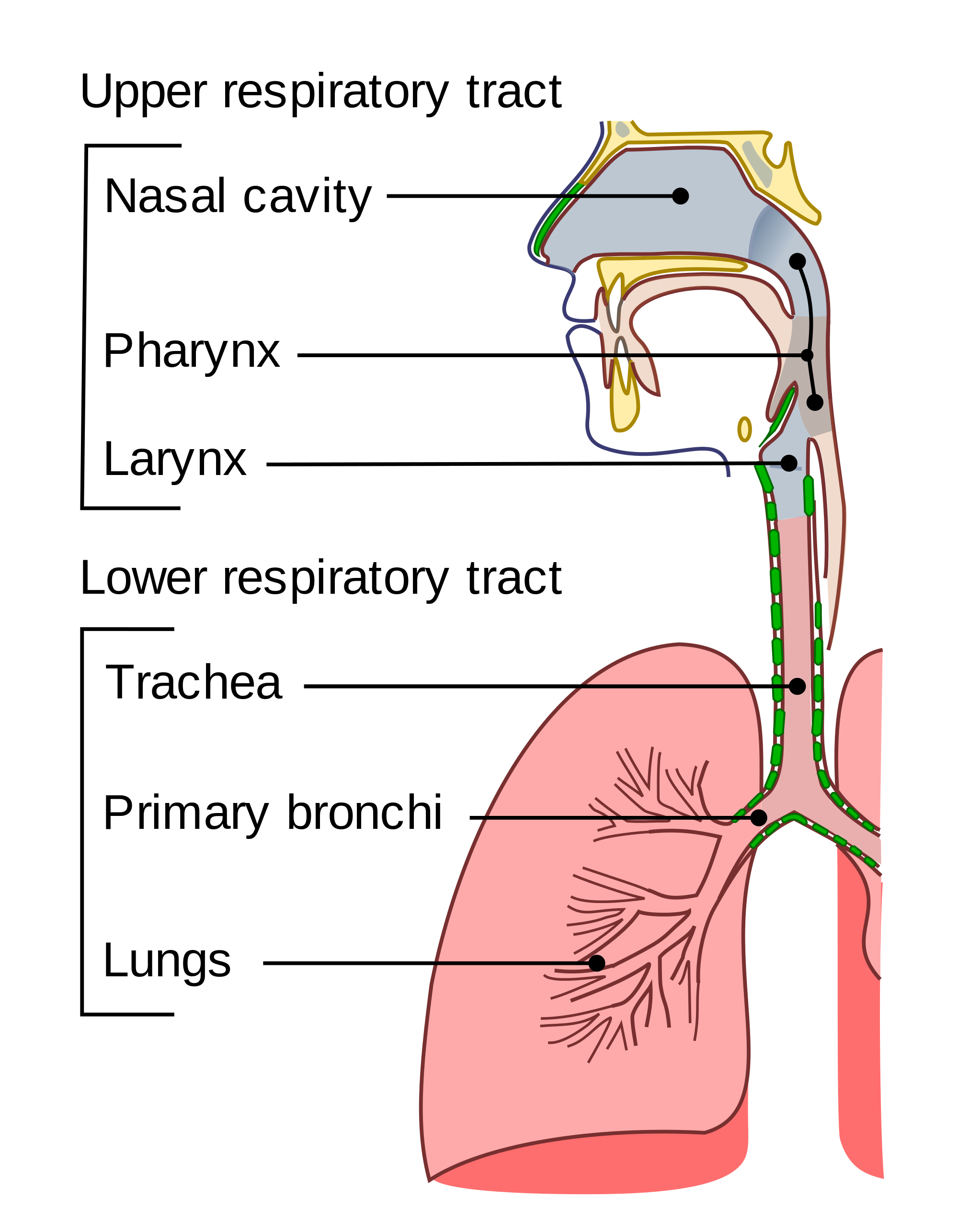

Respiratory Organs

The organs of the respiratory system form a continuous system of passages, called the respiratory tract, through which air flows into and out of the body. The respiratory tract has two major divisions: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The organs in each division are shown in Figure 13.2.2. In addition to these organs, certain muscles of the thorax (body cavity that fills the chest) are also involved in respiration by enabling breathing. Most important is a large muscle called the diaphragm, which lies below the lungs and separates the thorax from the abdomen. Smaller muscles between the ribs also play a role in breathing.

Upper Respiratory Tract

All of the organs and other structures of the upper respiratory tract are involved in conduction, or the movement of air into and out of the body. Upper respiratory tract organs provide a route for air to move between the outside atmosphere and the lungs. They also clean, humidify, and warm the incoming air. No gas exchange occurs in these organs.

Nasal Cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space in the skull above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. It is a continuation of the two nostrils. As inhaled air flows through the nasal cavity, it is warmed and humidified by blood vessels very close to the surface of this epithelial tissue . Hairs in the nose and mucous produced by mucous membranes help trap larger foreign particles in the air before they go deeper into the respiratory tract. In addition to its respiratory functions, the nasal cavity also contains chemoreceptors needed for sense of smell, and contribution to the sense of taste.

Pharynx

The pharynx is a tube-like structure that connects the nasal cavity and the back of the mouth to other structures lower in the throat, including the larynx. The pharynx has dual functions — both air and food (or other swallowed substances) pass through it, so it is part of both the respiratory and the digestive systems. Air passes from the nasal cavity through the pharynx to the larynx (as well as in the opposite direction). Food passes from the mouth through the pharynx to the esophagus.

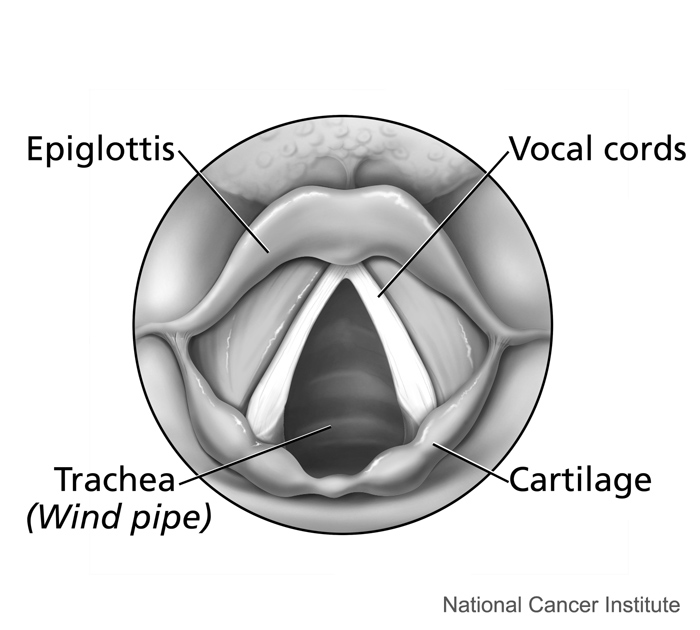

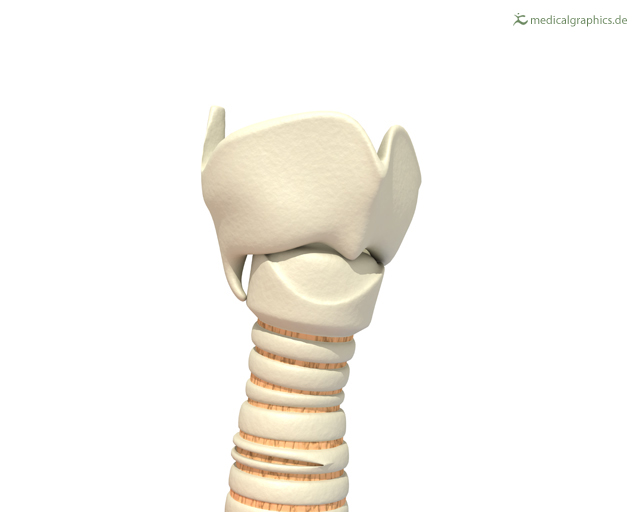

Larynx

The larynx connects the pharynx and trachea, and helps to conduct air through the respiratory tract. The larynx is also called the voice box, because it contains the vocal cords, which vibrate when air flows over them, thereby producing sound. You can see the vocal cords in the larynx in Figures 13.2.3 and 13.2.4. Certain muscles in the larynx move the vocal cords apart to allow breathing. Other muscles in the larynx move the vocal cords together to allow the production of vocal sounds. The latter muscles also control the pitch of sounds and help control their volume.

|

Figure 13.2.4 The larynx as viewed from the top. |

A very important function of the larynx is protecting the trachea from aspirated food. When swallowing occurs, the backward motion of the tongue forces a flap called the epiglottis to close over the entrance to the larynx. (You can see the epiglottis in both Figure 13.2.3 and 13.2.4.) This prevents swallowed material from entering the larynx and moving deeper into the respiratory tract. If swallowed material does start to enter the larynx, it irritates the larynx and stimulates a strong cough reflex. This generally expels the material out of the larynx, and into the throat.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BsyB88mq5rQ

Larynx Model - Respiratory System, Dr. Lotz, 2018.

Lower Respiratory Tract

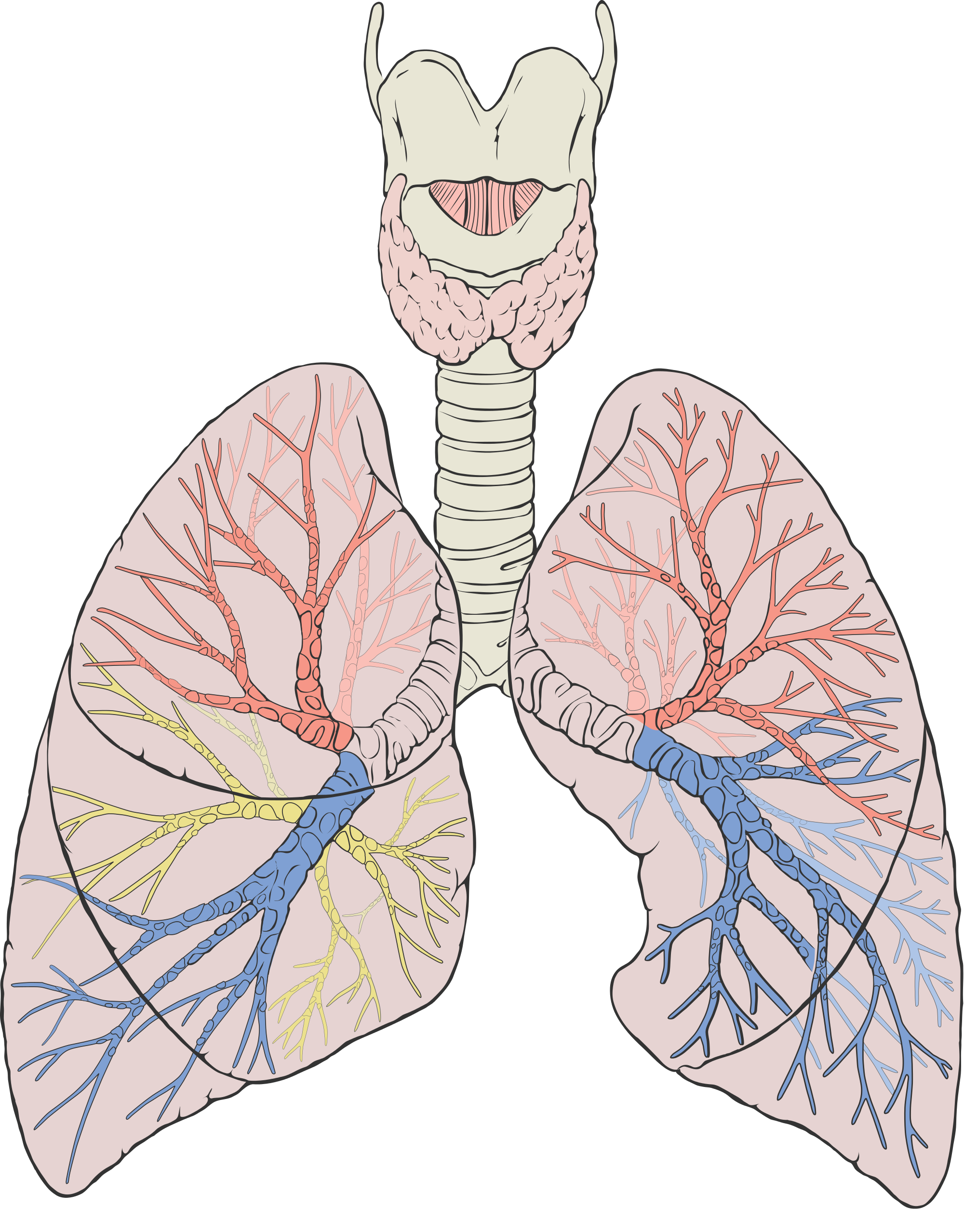

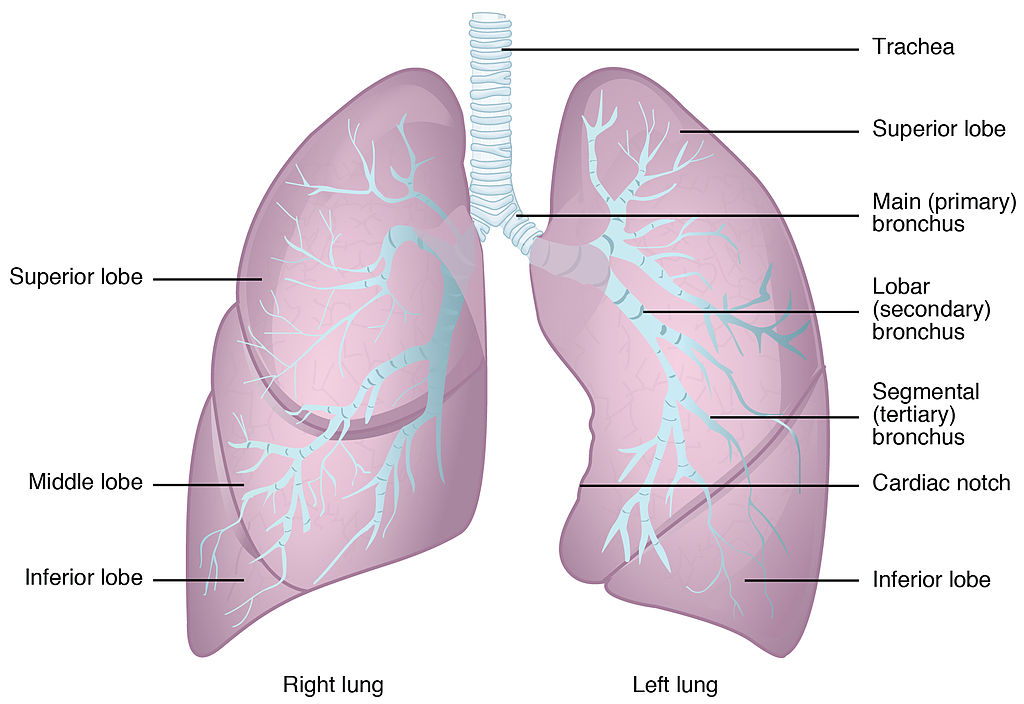

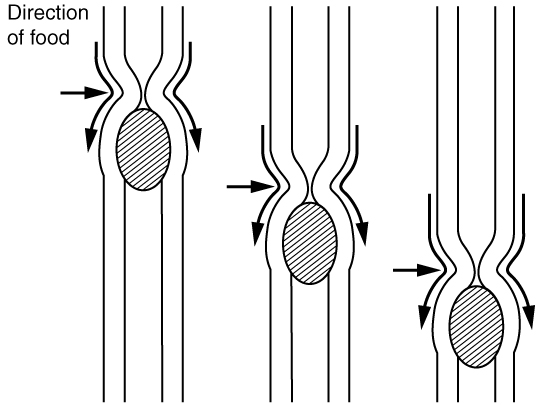

The trachea and other passages of the lower respiratory tract conduct air between the upper respiratory tract and the lungs. These passages form an inverted tree-like shape (Figure 13.2.5), with repeated branching as they move deeper into the lungs. All told, there are an astonishing 2,414 kilometres (1,500 miles) of airways conducting air through the human respiratory tract! It is only in the lungs, however, that gas exchange occurs between the air and the bloodstream.

Trachea

The trachea, or windpipe, is the widest passageway in the respiratory tract. It is about 2.5 cm wide and 10-15 cm long (approximately 1 inch wide and 4–6 inches long). It is formed by rings of cartilage, which make it relatively strong and resilient. The trachea connects the larynx to the lungs for the passage of air through the respiratory tract. The trachea branches at the bottom to form two bronchial tubes.

Bronchi and Bronchioles

There are two main bronchial tubes, or bronchi (singular, bronchus), called the right and left bronchi. The bronchi carry air between the trachea and lungs. Each bronchus branches into smaller, secondary bronchi; and secondary bronchi branch into still smaller tertiary bronchi. The smallest bronchi branch into very small tubules called bronchioles. The tiniest bronchioles end in alveolar ducts, which terminate in clusters of minuscule air sacs, called alveoli (singular, alveolus), in the lungs.

Lungs

The lungs are the largest organs of the respiratory tract. They are suspended within the pleural cavity of the thorax. The lungs are surrounded by two thin membranes called pleura, which secrete fluid that allows the lungs to move freely within the pleural cavity. This is necessary so the lungs can expand and contract during breathing. In Figure 13.2.6, you can see that each of the two lungs is divided into sections. These are called lobes, and they are separated from each other by connective tissues. The right lung is larger and contains three lobes. The left lung is smaller and contains only two lobes. The smaller left lung allows room for the heart, which is just left of the center of the chest.

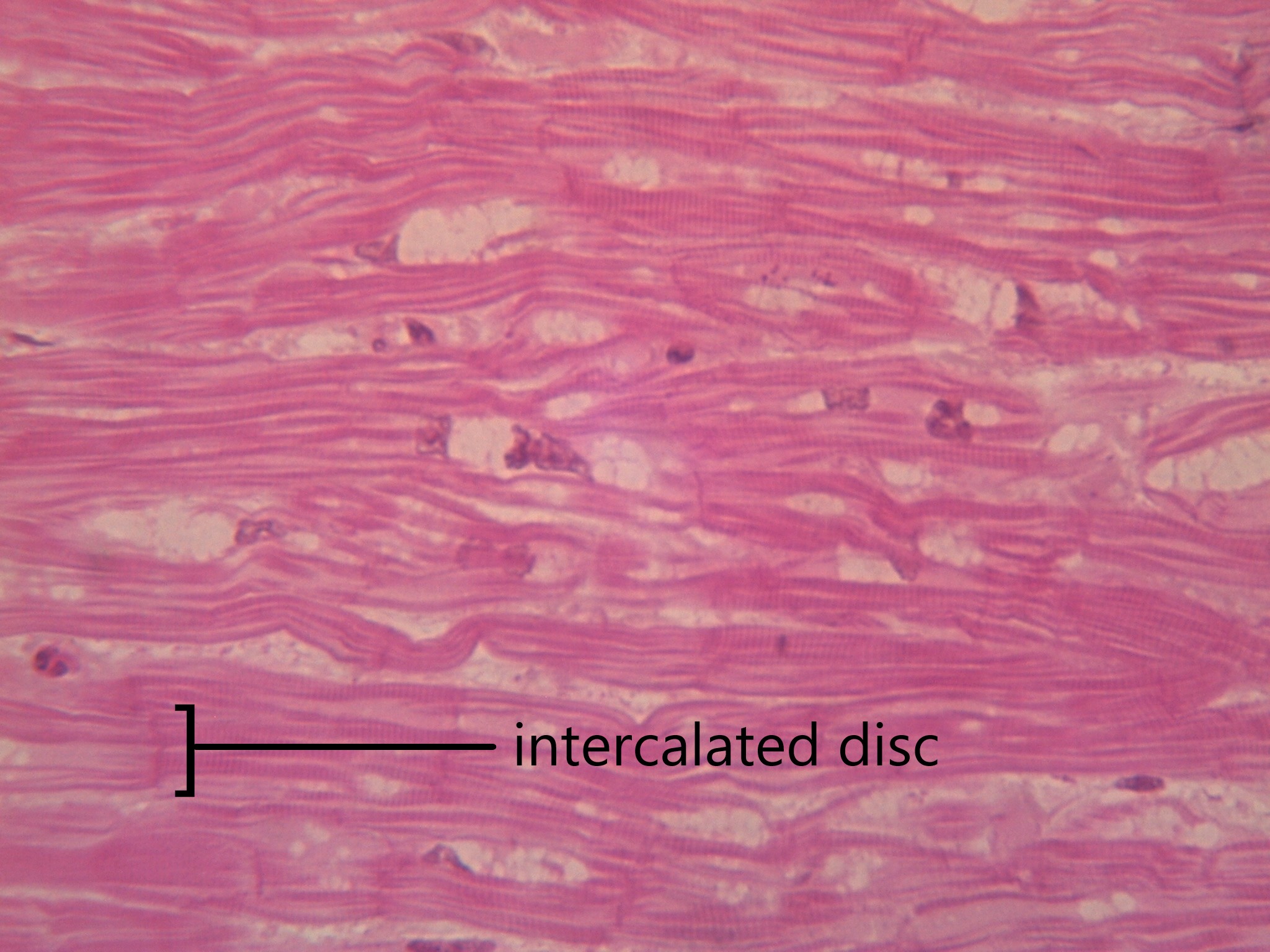

As mentioned previously, the bronchi terminate in bronchioles which feed air into alveoli, tiny sacs of simple squamous epithelial tissue which make up the bulk of the lung. The cross-section of lung tissue in the diagram below (Figure 13.2.7) shows the alveoli, in which gas exchange takes place with the capillary network that surrounds them.

|

|

Lung tissue consists mainly of alveoli (see Figures 13.2.7 and 13.2.8). These tiny air sacs are the functional units of the lungs where gas exchange takes place. The two lungs may contain as many as 700 million alveoli, providing a huge total surface area for gas exchange to take place. In fact, alveoli in the two lungs provide as much surface area as half a tennis court! Each time you breathe in, the alveoli fill with air, making the lungs expand. Oxygen in the air inside the alveoli is absorbed by the blood via diffusion in the mesh-like network of tiny capillaries that surrounds each alveolus. The blood in these capillaries also releases carbon dioxide (also by diffusion) into the air inside the alveoli. Each time you breathe out, air leaves the alveoli and rushes into the outside atmosphere, carrying waste gases with it.

The lungs receive blood from two major sources. They receive deoxygenated blood from the right side of the heart. This blood absorbs oxygen in the lungs and carries it back to the left side heart to be pumped to cells throughout the body. The lungs also receive oxygenated blood from the heart that provides oxygen to the cells of the lungs for cellular respiration.

Protecting the Respiratory System

You may be able to survive for weeks without food and for days without water, but you can survive without oxygen for only a matter of minutes — except under exceptional circumstances — so protecting the respiratory system is vital. Ensuring that a patient has an open airway is the first step in treating many medical emergencies. Fortunately, the respiratory system is well protected by the ribcage of the skeletal system. The extensive surface area of the respiratory system, however, is directly exposed to the outside world and all its potential dangers in inhaled air. It should come as no surprise that the respiratory system has a variety of ways to protect itself from harmful substances, such as dust and pathogens in the air.

The main way the respiratory system protects itself is called the mucociliary escalator. From the nose through the bronchi, the respiratory tract is covered in epithelium that contains mucus-secreting goblet cells. The mucus traps particles and pathogens in the incoming air. The epithelium of the respiratory tract is also covered with tiny cell projections called cilia (singular, cilium), as shown in the animation. The cilia constantly move in a sweeping motion upward toward the throat, moving the mucus and trapped particles and pathogens away from the lungs and toward the outside of the body. The upward sweeping motion of cilia lining the respiratory tract helps keep it free from dust, pathogens, and other harmful substances.

Watch "Mucociliary clearance" by I-Hsun Wu to learn more:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMB6flEaZwI

Mucociliary clearance, I-Hsun Wu, 2015.

Sneezing is a similar involuntary response that occurs when nerves lining the nasal passage are irritated. It results in forceful expulsion of air from the mouth, which sprays millions of tiny droplets of mucus and other debris out of the mouth and into the air, as shown in Figure 13.2.9. This explains why it is so important to sneeze into a tissue (rather than the air) if we are to prevent the transmission of respiratory pathogens.

How the Respiratory System Works with Other Organ Systems

The amount of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood must be maintained within a limited range for survival of the organism. Cells cannot survive for long without oxygen, and if there is too much carbon dioxide in the blood, the blood becomes dangerously acidic (pH is too low). Conversely, if there is too little carbon dioxide in the blood, the blood becomes too basic (pH is too high). The respiratory system works hand-in-hand with the nervous and cardiovascular systems to maintain homeostasis in blood gases and pH.

It is the level of carbon dioxide — rather than the level of oxygen — that is most closely monitored to maintain blood gas and pH homeostasis. The level of carbon dioxide in the blood is detected by cells in the brain, which speed up or slow down the rate of breathing through the autonomic nervous system as needed to bring the carbon dioxide level within the normal range. Faster breathing lowers the carbon dioxide level (and raises the oxygen level and pH), while slower breathing has the opposite effects. In this way, the levels of carbon dioxide, oxygen, and pH are maintained within normal limits.

The respiratory system also works closely with the cardiovascular system to maintain homeostasis. The respiratory system exchanges gases with the outside air, but it needs the cardiovascular system to carry them to and from body cells. Oxygen is absorbed by the blood in the lungs and then transported through a vast network of blood vessels to cells throughout the body, where it is needed for aerobic cellular respiration. The same system absorbs carbon dioxide from cells and carries it to the respiratory system for removal from the body.

Feature: My Human Body

Choking due to a foreign object becoming lodged in the airway results in nearly 5 thousand deaths in Canada each year. In addition, choking accounts for almost 40% of unintentional injuries in infants under the age of one. For the sake of your own human body, as well as those of loved ones, you should be aware of choking risks, signs, and treatments.

Choking is the mechanical obstruction of the flow of air from the atmosphere into the lungs. It prevents breathing, and may be partial or complete. Partial choking allows some — though inadequate — air flow into the lungs. Prolonged or complete choking results in asphyxia, or suffocation, which is potentially fatal.

Obstruction of the airway typically occurs in the pharynx or trachea. Young children are more prone to choking than are older people, in part because they often put small objects in their mouth and do not understand the risk of choking that they pose. Young children may choke on small toys or parts of toys, or on household objects, in addition to food. Foods that are round (hotdogs, carrots, grapes) or can adapt their shape to that of the pharynx (bananas, marshmallows), are especially dangerous, and may cause choking in adults, as well as children.

How can you tell if a loved one is choking? The person cannot speak or cry out, or has great difficulty doing so. Breathing, if possible, is laboured, producing gasping or wheezing. The person may desperately clutch at his or her throat or mouth. If breathing is not soon restored, the person’s face will start to turn blue from lack of oxygen. This will be followed by unconsciousness, brain damage, and possibly death if oxygen deprivation continues beyond a few minutes.

If an infant is choking, turning the baby upside down and slapping him on the back may dislodge the obstructing object. To help an older person who is choking, first encourage the person to cough. Give them a few hard back slaps to help force the lodged object out of the airway. If these steps fail, perform the Heimlich maneuver on the person. See the series of videos below, from ProCPR, which demonstrate several ways to help someone who is choking based on age and consciousness.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOTbjDGZ7wg&t=46s

Conscious Adult Choking, ProCPR, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5kmsKNvKAvU

Unconscious Adult Choking, ProCPR, 2011.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjmbD7aIaf0

Conscious Child Choking, ProCPR, 2009.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sba0T2XGIn4

Unconscious Child Choking, ProCPR, 2009.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axqIju9CLKA

Conscious Infant Choking, ProCPR, 2011.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_K7Dwy6b2wQ

Unconscious Infant Choking, ProCPR, 2011.

13.2 Summary

- Respiration is the process in which oxygen moves from the outside air into the body, and in which carbon dioxide and other waste gases move from inside the body into the outside air. It involves two subsidiary processes: ventilation and gas exchange. Respiration is carried out mainly by the respiratory system.

- The organs of the respiratory system form a continuous system of passages, called the respiratory tract. It has two major divisions: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract.

- The upper respiratory tract includes the nasal cavity, pharynx, and larynx. All of these organs are involved in conduction, or the movement of air into and out of the body. Incoming air is also cleaned, humidified, and warmed as it passes through the upper respiratory tract. The larynx is called the voice box, because it contains the vocal cords, which are needed to produce vocal sounds.

- The lower respiratory tract includes the trachea, bronchi and bronchioles, and the lungs. The trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles are involved in conduction. Gas exchange takes place only in the lungs, which are the largest organs of the respiratory tract. Lung tissue consists mainly of tiny air sacs called alveoli, which is where gas exchange takes place between air in the alveoli and the blood in capillaries surrounding them.

- The respiratory system protects itself from potentially harmful substances in the air by the mucociliary escalator. This includes mucus-producing cells, which trap particles and pathogens in incoming air. It also includes tiny hair-like cilia that continually move to sweep the mucus and trapped debris away from the lungs and toward the outside of the body.

- The level of carbon dioxide in the blood is monitored by cells in the brain. If the level becomes too high, it triggers a faster rate of breathing, which lowers the level to the normal range. The opposite occurs if the level becomes too low. The respiratory system exchanges gases with the outside air, but it needs the cardiovascular system to carry the gases to and from cells throughout the body.

13.2 Review Questions

-

- What is respiration, as carried out by the respiratory system? Name the two subsidiary processes it involves.

- Describe the respiratory tract.

- Identify the organs of the upper respiratory tract. What are their functions?

- List the organs of the lower respiratory tract. Which organs are involved only in conduction?

- Where does gas exchange take place?

- How does the respiratory system protect itself from potentially harmful substances in the air?

- Explain how the rate of breathing is controlled.

- Why does the respiratory system need the cardiovascular system to help it perform its main function of gas exchange?

- Describe two ways in which the body prevents food from entering the lungs.

- What is the relationship between respiration and cellular respiration?

13.2 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8NUxvJS-_0k

How do lungs work? - Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=6iFPs6JlSzY&feature=emb_logo

Why Do Men Have Deeper Voices? BrainStuff - HowStuffWorks, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjibeBSnpJ0

Why does your voice change as you get older? - Shaylin A. Schundler, TED-Ed, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 13.2.1

Exhale by pavel-lozovikov-HYovA7yPPvI [photo] by Pavel Lozovikov on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 13.2.2

Illu_conducting_passages.svg by Lord Akryl, Jmarchn from SEER Training Modules/ National Cancer Institute on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.2.3

Larynx by www.medicalgraphics.de is used under a CC BY-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/) license.

Figure 13.2.4

Larynx top view by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) for National Cancer Institute is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 13.2.5

2000px-Lungs_diagram_detailed.svg by Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5) license. (Derivative work of Fruchtwasserembolie.png.)

Figure 13.2.6

Gross_Anatomy_of_the_Lungs by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 13.2.7

Alveoli Structure by CNX OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 13.2.8

annotated_diagram_of_an_alveolus.svg by Katherinebutler1331 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 13.2.9

Sneeze by James Gathany at CDC Public Health Imagery Library (PHIL) #11162 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.2 Major respiratory structures [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-1-organs-and-structures-of-the-respiratory-system [CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)].

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 22.13 Gross anatomy of the lungs [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 22.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/22-2-the-lungs

BrainStuff - HowStuffWorks. (2015, December 1). Why do men have deeper voices? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iFPs6JlSzY&feature=youtu.be

Dr. Lotz. (2018, January 25). Larynx model - Respiratory system. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BsyB88mq5rQ&feature=youtu.be

I-Hsun Wu. (2015, March 31). Mucociliary clearance. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMB6flEaZwI&feature=youtu.be

OpenStax. (2016, May 27). Figure 9 Terminal bronchioles are connected by respiratory bronchioles to alveolar ducts and alveolar sacs [digital image]. In OpenStax, Biology (Section 39.1). OpenStax CNX. https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.53:35-R0biq@11/Systems-of-Gas-Exchange

ProCPR. (2009, November 24). Conscious child choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjmbD7aIaf0&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2009, November 24).Unconscious child choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sba0T2XGIn4&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2011, February 1). Conscious infant choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axqIju9CLKA&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2011, February 1). Unconscious adult choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5kmsKNvKAvU&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2011, February 1). Unconscious infant choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_K7Dwy6b2wQ&feature=youtu.be

ProCPR. (2016, April 8). Conscious adult choking. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOTbjDGZ7wg&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2014, November 24). How do lungs work? - Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8NUxvJS-_0k&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, August 2). Why does your voice change as you get older? - Shaylin A. Schundler. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rjibeBSnpJ0&feature=youtu.be

The body system responsible for the elimination of wastes produced by homeostasis. There are several parts of the body that are involved in this process, such as sweat glands, the liver, the lungs and the kidney system. ... From there, urine is expelled through the urethra and out of the body.

Image shows a microscopic view of the structure of spongy bone. It is an irregular lattice of bone and open space, which typically houses bone marrow and blood vessels.

Image shows a photo of a young child exhibiting Polydactyly- a condition in which a person is born with extra fingers or toes. In this photo, the child has an extra pinky finger on each hand.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Cancer in the Family

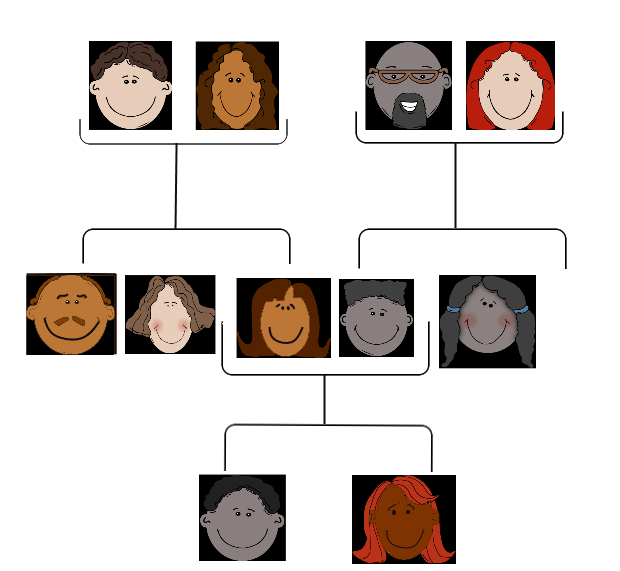

People tend to carry similar traits to their biological parents, as illustrated by the family tree. Beyond just appearance, you can also inherit traits from your parents that you can’t see.

Rebecca becomes very aware of this fact when she visits her new doctor for a physical exam. Her doctor asks several questions about her family medical history, including whether Rebecca has or had relatives with cancer. Rebecca tells her that her grandmother, aunt, and uncle — who have all passed away — had cancer. They all had breast cancer, including her uncle, and her aunt also had ovarian cancer. Her doctor asks how old they were when they were diagnosed with cancer. Rebecca is not sure exactly, but she knows that her grandmother was fairly young at the time, probably in her forties.

Rebecca’s doctor explains that while the vast majority of cancers are not due to inherited factors, a cluster of cancers within a family may indicate that there are mutations in certain genes that increase the risk of getting certain types of cancer, particularly breast and ovarian cancer. Some signs that cancers may be due to these genetic factors are present in Rebecca’s family, such as cancer with an early age of onset (e.g., breast cancer before age 50), breast cancer in men, and breast cancer and ovarian cancer within the same person or family.

Based on her family medical history, Rebecca’s doctor recommends that she see a genetic counselor, because these professionals can help determine whether the high incidence of cancers in her family could be due to inherited mutations in their genes. If so, they can test Rebecca to find out whether she has the particular variations of these genes that would increase her risk of getting cancer.

When Rebecca sees the genetic counselor, he asks how her grandmother, aunt, and uncle with cancer are related to her. She says that these relatives are all on her mother’s side — they are her mother’s mother and siblings. The genetic counselor records this information in the form of a specific type of family tree, called a pedigree, indicating which relatives had which type of cancer, and how they are related to each other and to Rebecca.

He also asks her ethnicity. Rebecca says that her family on both sides are Ashkenazi Jews (Jews whose ancestors came from central and eastern Europe). “But what does that have to do with anything?” she asks. The counselor tells Rebecca that mutations in two tumor-suppressor genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2, located on chromosome 17 and 13, respectively, are particularly prevalent in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and greatly increase the risk of getting cancer. About one in 40 Ashkenazi Jewish people have one of these mutations, compared to about one in 800 in the general population. Her ethnicity, along with the types of cancer, age of onset, and the specific relationships between her family members who had cancer, indicate to the counselor that she is a good candidate for genetic testing for the presence of these mutations.

Rebecca says that her 72-year-old mother never had cancer, nor had many other relatives on that side of the family. How could the cancers be genetic? The genetic counselor explains that the mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, while dominant, are not inherited by everyone in a family. Also, even people with mutations in these genes do not necessarily get cancer — the mutations simply increase their risk of getting cancer. For instance, 55 to 65 per cent of women with a harmful mutation in the BRCA1 gene will get breast cancer before age 70, compared to 12 per cent of women in the general population who will get breast cancer sometime over the course of their lives.

Rebecca is not sure she wants to know whether she has a higher risk of cancer. The genetic counselor understands her apprehension, but explains that if she knows that she has harmful mutations in either of these genes, her doctor will screen her for cancer more often and at earlier ages. Therefore, any cancers she may develop are likely to be caught earlier when they are often much more treatable. Rebecca decides to go through with the testing, which involves taking a blood sample, and nervously waits for her results.

Chapter Overview: Genetics

At the end of this chapter, you will find out Rebecca’s test results. By then, you will have learned how traits are inherited from parents to offspring through genes, and how mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 can be passed down and cause disease. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The structure of DNA.

- How DNA replication occurs.

- How DNA was found to be the inherited genetic material.

- How genes and their different alleles are located on chromosomes.

- The 23 pairs of human chromosomes, which include autosomal and sex chromosomes.

- How genes code for proteins using codons made of the sequence of nitrogen bases within RNA and DNA.

- The central dogma of molecular biology, which describes how DNA is transcribed into RNA, and then translated into proteins.

- The structure, functions, and possible evolutionary history of RNA.

- How proteins are synthesized through the transcription of RNA from DNA and the translation of protein from RNA, including how RNA and proteins can be modified, and the roles of the different types of RNA.

- What mutations are, what causes them, different specific types of mutations, and the importance of mutations in evolution and to human health.

- How the expression of genes into proteins is regulated and why problems in this process can cause diseases, such as cancer.

- How Gregor Mendel discovered the laws of inheritance for certain types of traits.

- The science of heredity, known as genetics, and the relationship between genes and traits.

- How gametes, such as eggs and sperm, are produced through meiosis.

- How sexual reproduction works on the cellular level and how it increases genetic variation.

- Simple Mendelian and more complex non-Mendelian inheritance of some human traits.

- Human genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome, hemophilia A, and disorders involving sex chromosomes.

- How biotechnology — which is the use of technology to alter the genetic makeup of organisms — is used in medicine and agriculture, how it works, and some of the ethical issues it may raise.

- The human genome, how it was sequenced, and how it is contributing to discoveries in science and medicine.

As you read this chapter, keep Rebecca’s situation in mind and think about the following questions:

- BCRA1 and BCRA2 are also called Breast cancer type 1 and 2 susceptibility proteins. What do the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes normally do? How can they cause cancer?

- Are BRCA1 and BRCA2 linked genes? Are they on autosomal or sex chromosomes?

- After learning more about pedigrees, draw the pedigree for cancer in Rebecca’s family. Use the pedigree to help you think about why it is possible that her mother does not have one of the BRCA gene mutations, even if her grandmother, aunt, and uncle did have it.

- Why do you think certain gene mutations are prevalent in certain ethnic groups?

Attributions

Figure 5.1.1

Family Tree [all individual face images] from Clker.com used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC0 1.0 public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

Figure 5.1.2

Rebecca by Kyle Broad on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

References

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 27). Ashkenazi Jews. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ashkenazi_Jews&oldid=964691647

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 22). BRCA1. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BRCA1&oldid=963868423

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 25). BRCA2. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BRCA2&oldid=958722957

The breakdown of larger molecules into smaller ones.

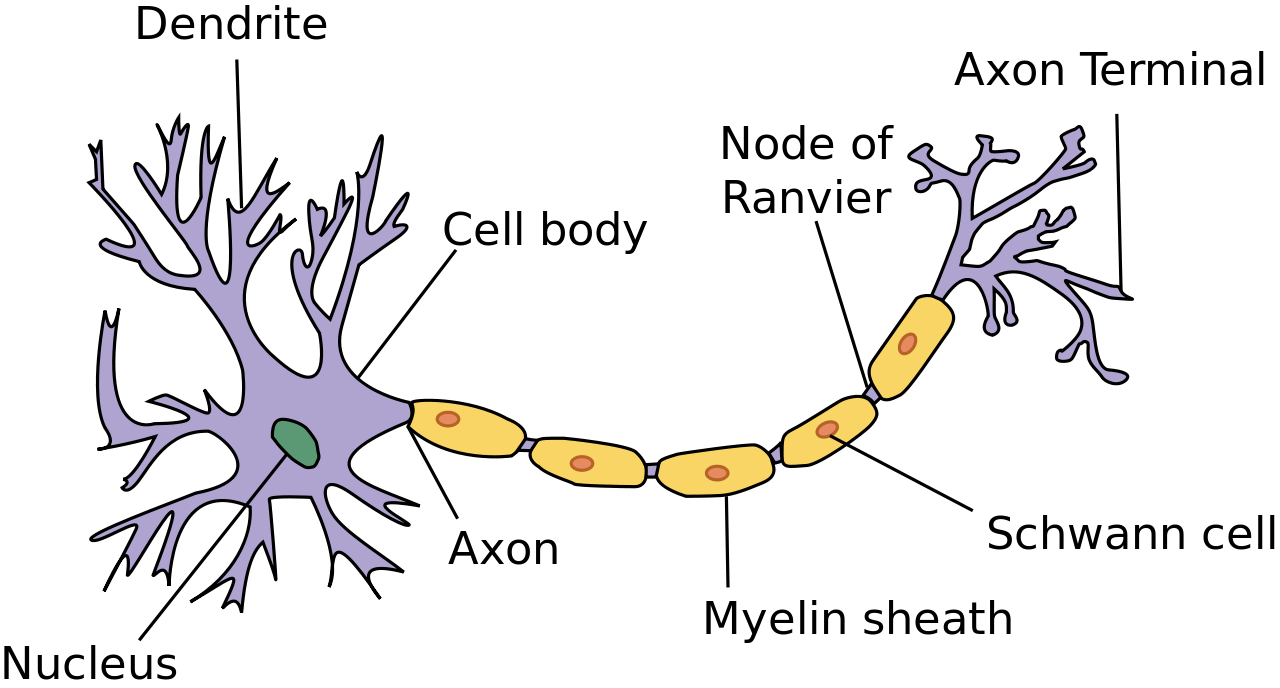

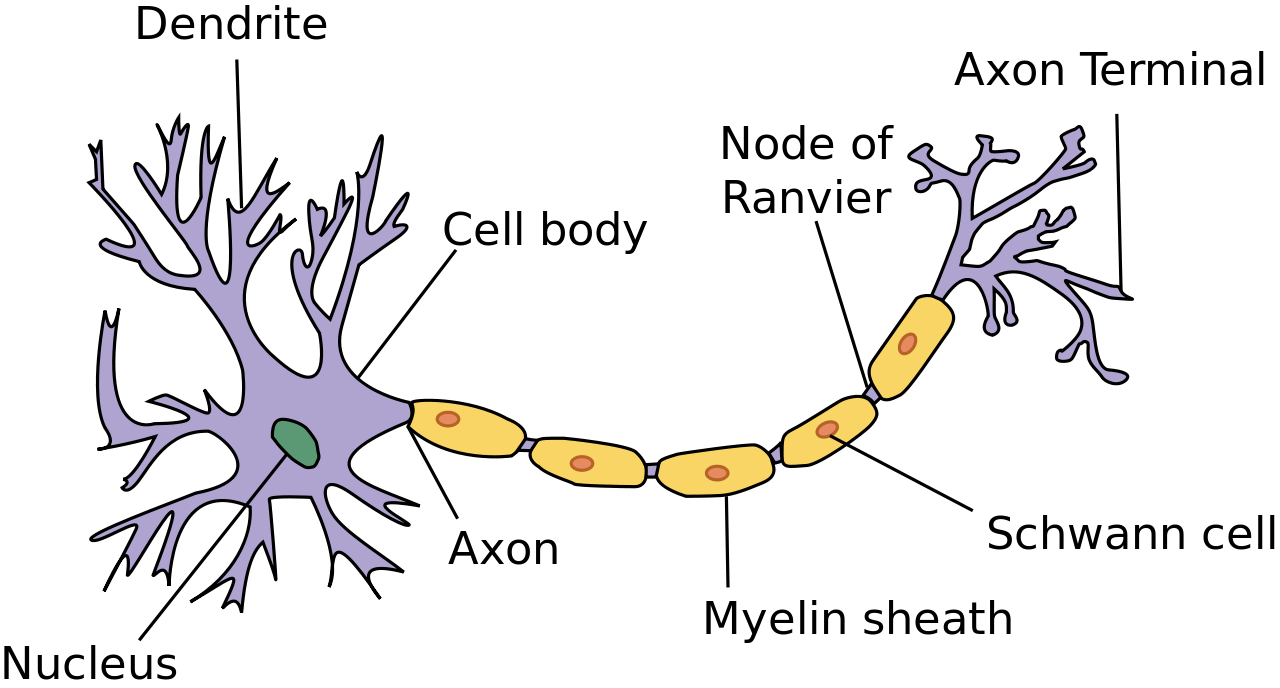

Image shows a labelled diagram of a neuron, with the structures in the list above.

The way in which scientists and researchers use a systematic approach to answer questions about the world around us.

Figure 7.4.1 Construction — It's important to have the right materials for the job.

The Right Material for the Job

Building a house is a big job and one that requires a lot of different materials for specific purposes. As you can see in Figure 7.4.1, many different types of materials are used to build a complete house, but each type of material fulfills certain functions. You wouldn't use insulation to cover your roof, and you wouldn't use lumber to wire your home. Just as a builder chooses the appropriate materials to build each aspect of a home (wires for electrical, lumber for framing, shingles for roofing), your body uses the right cells for each type of role. When many cells work together to perform a specific function, this is termed a tissue.

Tissues

Groups of connected cells form tissues. The cells in a tissue may all be the same type, or they may be of multiple types. In either case, the cells in the tissue work together to carry out a specific function, and they are always specialized to be able to carry out that function better than any other type of tissue. There are four main types of human tissues: connective, epithelial, muscle, and nervous tissues. We use tissues to build organs and organ systems. The 200 types of cells that the body can produce based on our single set of DNA can create all the types of tissue in the body.

Epithelial Tissue

Epithelial tissue is made up of cells that line inner and outer body surfaces, such as the skin and the inner surface of the digestive tract. Epithelial tissue that lines inner body surfaces and body openings is called mucous membrane. This type of epithelial tissue produces mucus, a slimy substance that coats mucous membranes and traps pathogens, particles, and debris. Epithelial tissue protects the body and its internal organs, secretes substances (such as hormones) in addition to mucus, and absorbs substances (such as nutrients).

The key identifying feature of epithelial tissue is that it contains a free surface and a basement membrane. The free surface is not attached to any other cells and is either open to the outside of the body, or is open to the inside of a hollow organ or body tube. The basement membrane anchors the epithelial tissue to underlying cells.

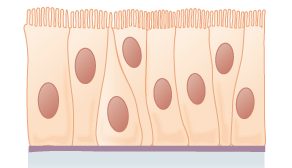

Epithelial tissue is identified and named by shape and layering. Epithelial cells exist in three main shapes: squamous, cuboidal, and columnar. These specifically shaped cells can, depending on function, be layered several different ways: simple, stratified, pseudostratified, and transitional.

Epithelial tissue forms coverings and linings and is responsible for a range of functions including diffusion, absorption, secretion and protection. The shape of an epithelial cell can maximize its ability to perform a certain function. The thinner an epithelial cell is, the easier it is for substances to move through it to carry out diffusion and/or absorption. The larger an epithelial cell is, the more room it has in its cytoplasm to be able to make products for secretion, and the more protection it can provide for underlying tissues. Their are three main shapes of epithelial cells: squamous (which is shaped like a pancake- flat and oval), cuboidal (cube shaped), and columnar (tall and rectangular).

Figure 7.4.2 The shape of epithelial tissues is important.

Epithelial tissue will also organize into different layerings depending on their function. For example, multiple layers of cells provide excellent protection, but would no longer be efficient for diffusion, whereas a single layer would work very well for diffusion, but no longer be as protective; a special type of layering called transitional is needed for organs that stretch, like your bladder. Your tissues exhibit the layering that makes them most efficient for the function they are supposed to perform. There are four main layerings found in epithelial tissue: simple (one layer of cells), stratified (many layers of cells), pseudostratified (appears stratified, but upon closer inspection is actually simple), and transitional (can stretch, going from many layers to fewer layers).

Figure 7.4.3 The layerings found in epithelial tissues is important.

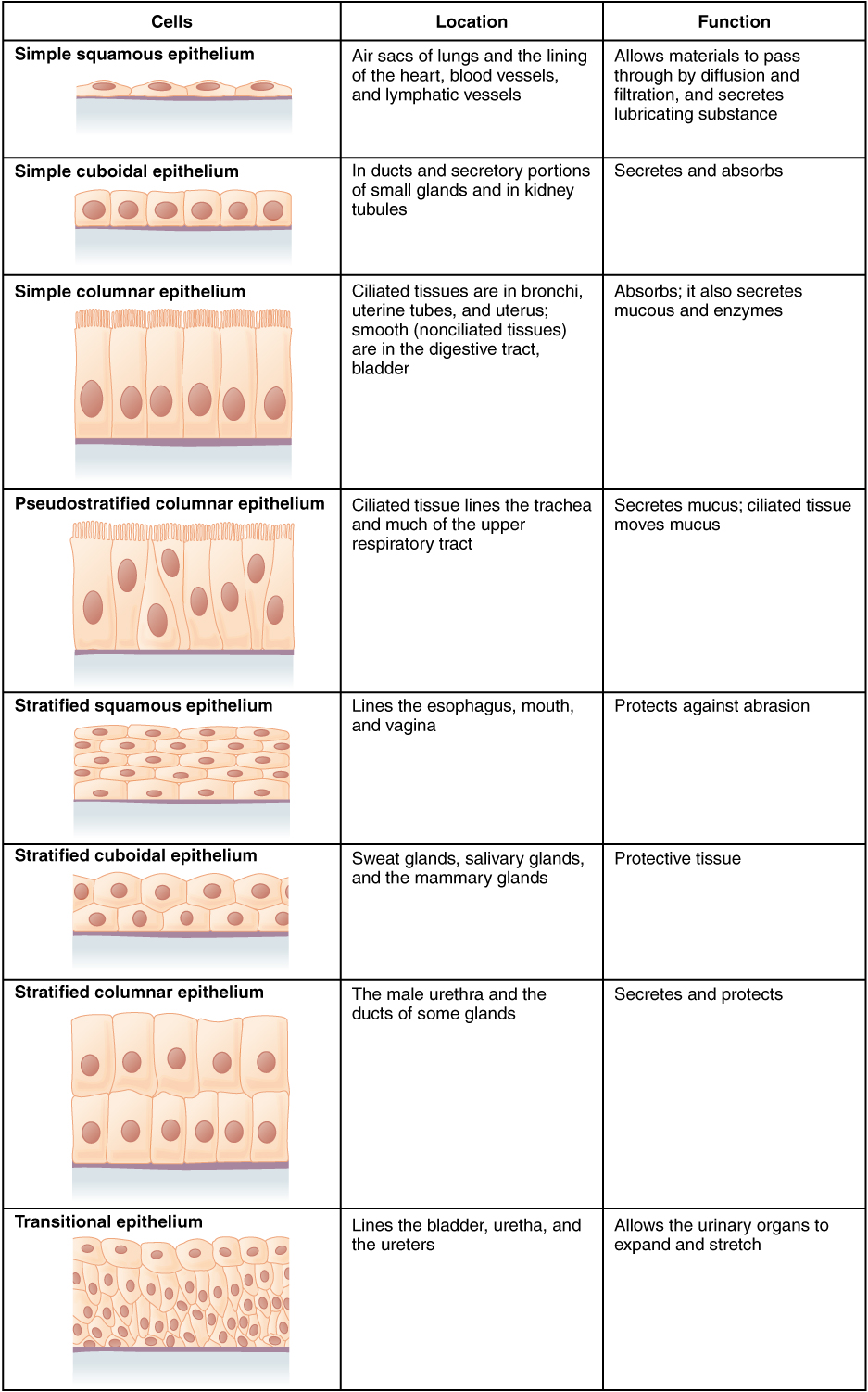

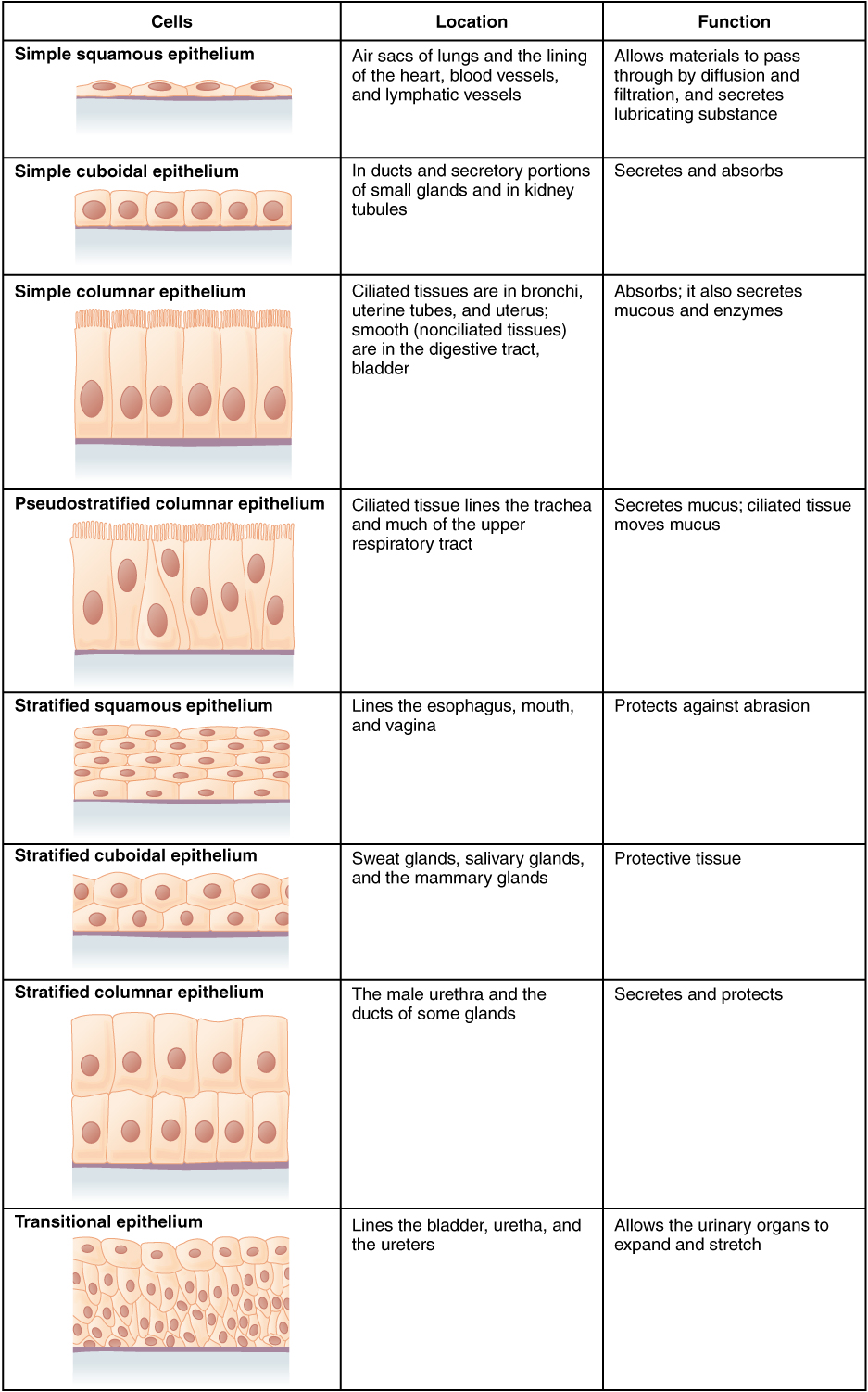

See Table 7.4.1 for a summary of the different layering types and shapes epithelial cells can form and their related functions and locations.

Table 7.4.1

Summary of Epithelial Tissue Cells

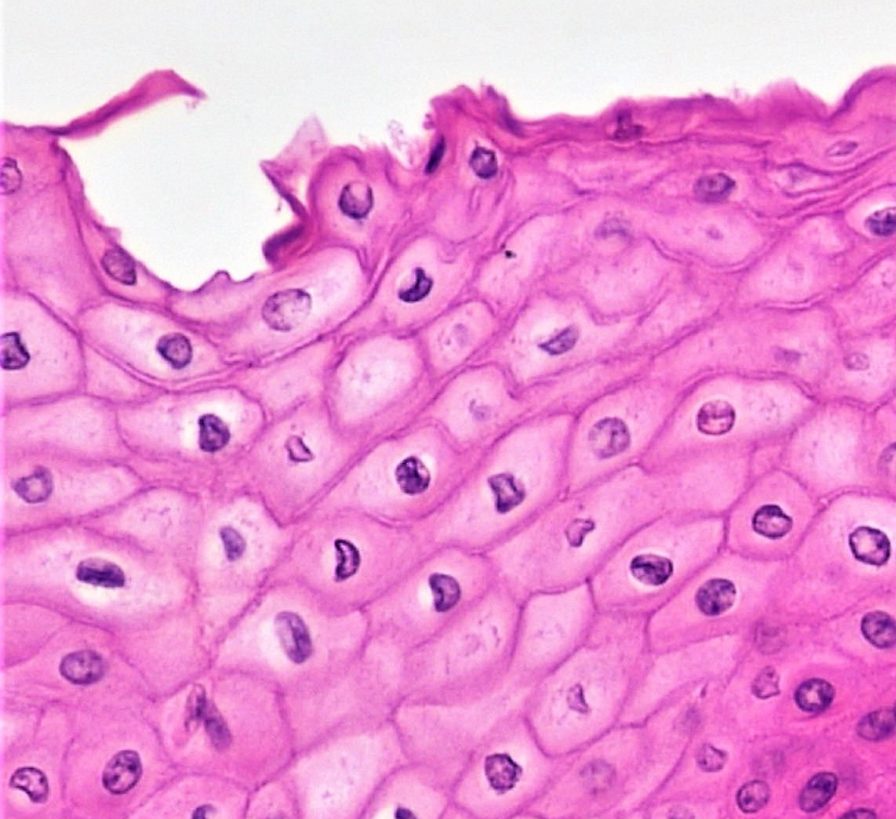

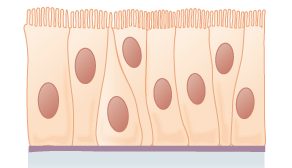

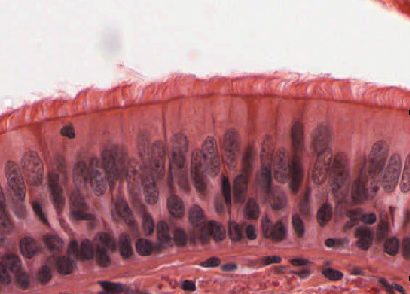

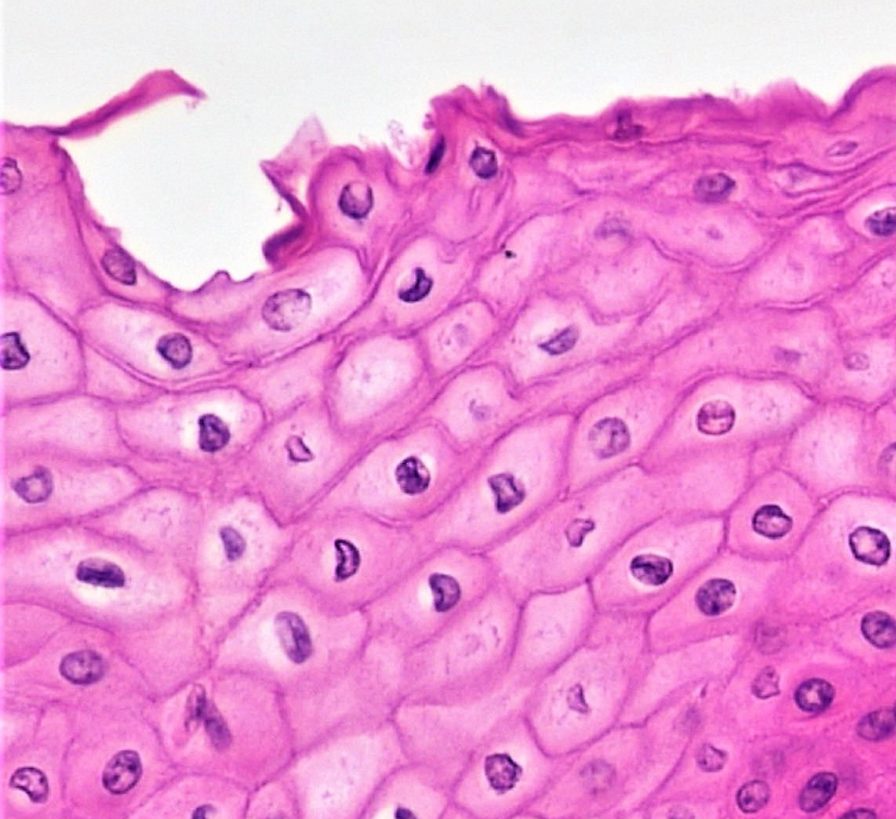

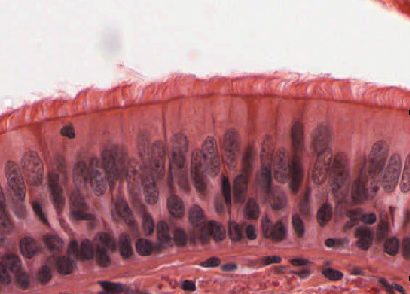

So far, we have identified epithelial tissue based on shape and layering. The representative diagrams we have seen so far are helpful for visualizing the tissue structures, but it is important to look at real examples of these cells. Since cells are too tiny to see with the naked eye, we rely on microscopes to help us study them. Histology is the study of the microscopic anatomy and cells and tissues. See Table 7.4.2 to see some examples of slides of epithelial tissues prepared for the purpose of histology.

Table 7.4.2

Epithelial Tissues and Histological Samples

| Epithelial Tissue Type | Tissue Diagram | Histological Sample |

| Stratified squamous

(from skin) |

|

|

| Simple cuboidal

(from kidney tubules) |

|

|

| Pseudostratified ciliated columnar

(from trachea) |

|

|

Connective Tissue

Bone and blood are examples of connective tissue. Connective tissue is very diverse. In general, it forms a framework and support structure for body tissues and organs. It's made up of living cells separated by non-living material, called extracellular matrix, which can be solid or liquid. The extracellular matrix of bone, for example, is a rigid mineral framework. The extracellular matrix of blood is liquid plasma.

The key identifying feature of connective tissue is that is is composed of a scattering of cells in a non-cellular matrix. There are three main categories of connective tissue, based on the nature of the matrix. They look very different from one another, which is a reflection of their different functions:

- Fibrous connective tissue: is characterized by a matrix which is flexible and is made of protein fibres including collagen, elastin and possibly reticular fibres. These tissues are found making up tendons, ligaments, and body membranes.

- Supportive connective tissue: is characterized by a solid matrix and is what is used to make bone and cartilage. These tissues are used for support and protection.

- Fluid connective tissue: is characterized by a fluid matrix and includes both blood and lymph.

Fibrous Connective Tissue

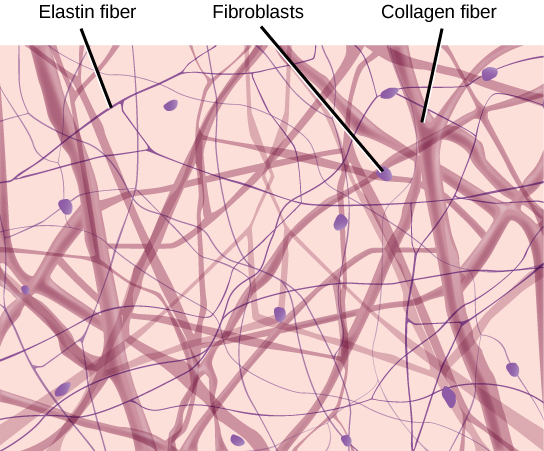

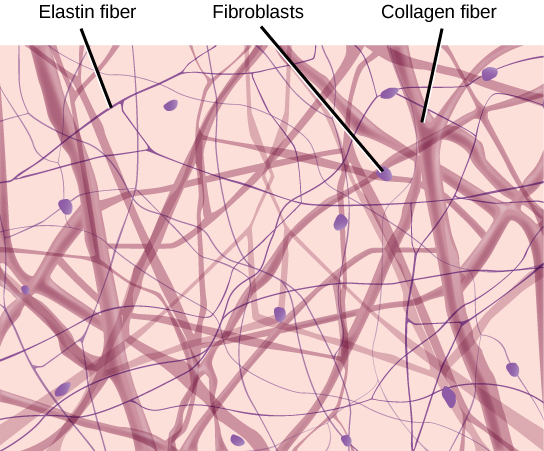

Fibrous connective tissue contains cells called fibroblasts. These cells produce fibres of collagen, elastin, or reticular fibre which makes up the matrix of this type of connective tissue. Based on how tightly packed these fibres are and how they are oriented changes the properties, and therefore the function of the fibrous connective tissue.

- Loose fibrous connective tissue: composed of a loose and disorganized weave of collagen and elastin fibres, creating a tissue that is thin and flexible, yet still tough. This tissue, which is also sometimes referred to as "areolar tissue", is found in membranes and surrounding blood vessels and most body organs. As you can see from the diagram in Figure 7.4.4, loose fibrous connective tissue fulfills the definition of connectives tissue since it is a scattering of cells (fibroblasts) in a non-cellular matrix (a mesh of collagen and elastin fibres). There are two types of specialized loose fibrous connective tissue: reticular and adipose. Adipose tissue stores fat and reticular tissue forms the spleen and lymph nodes.

Figure 7.4.4 Diagram of loose fibrous connective tissue consists of a scattering of fibroblasts in a non-cellular matrix of loosely woven collagen and elastin fibres.

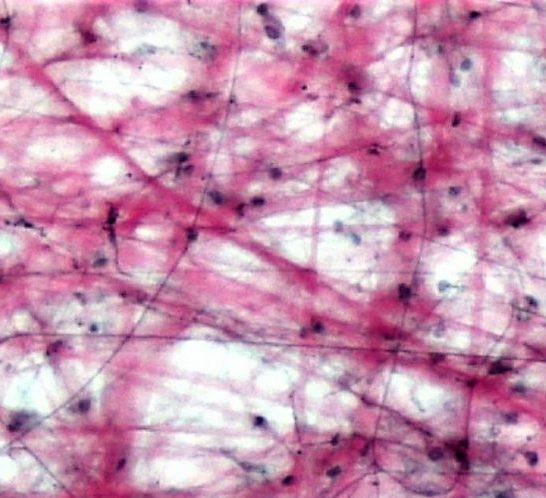

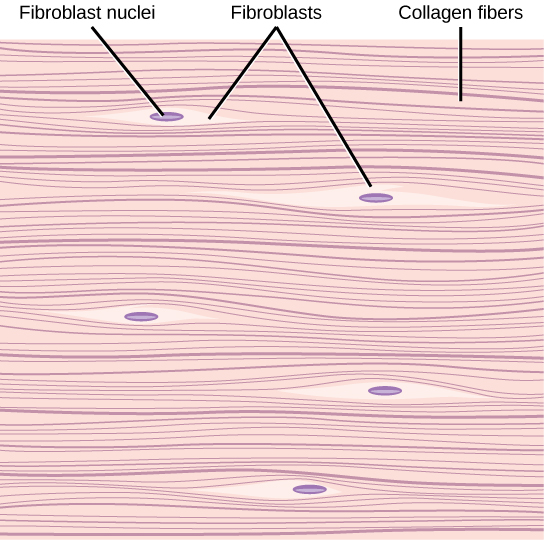

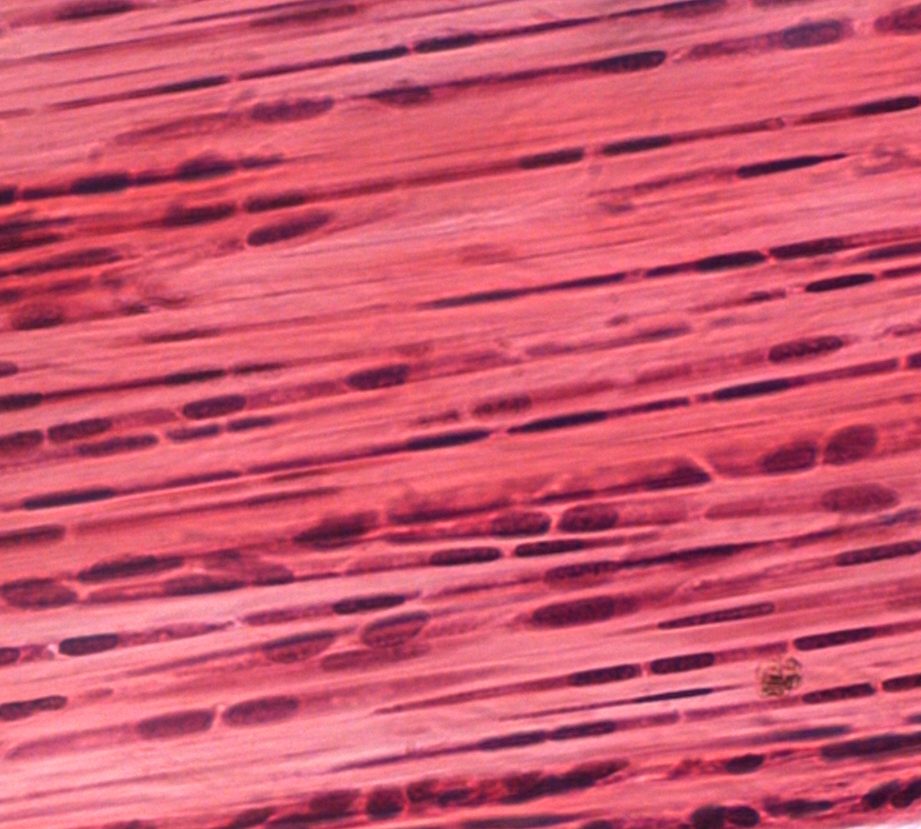

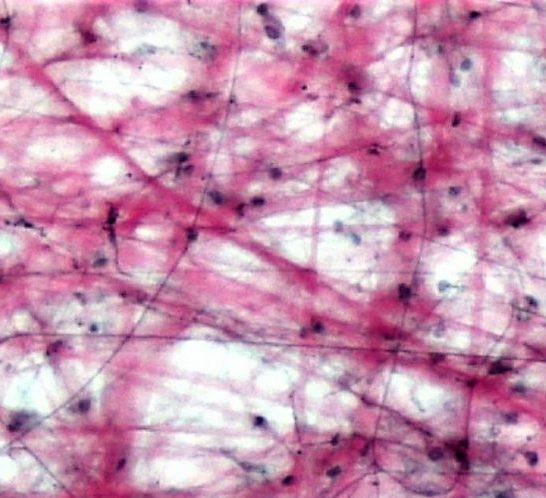

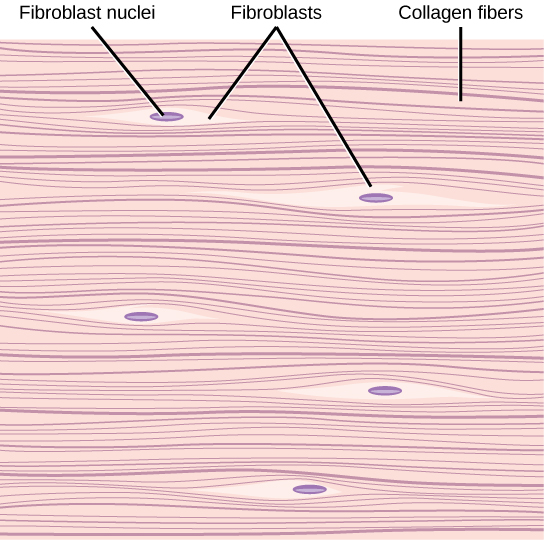

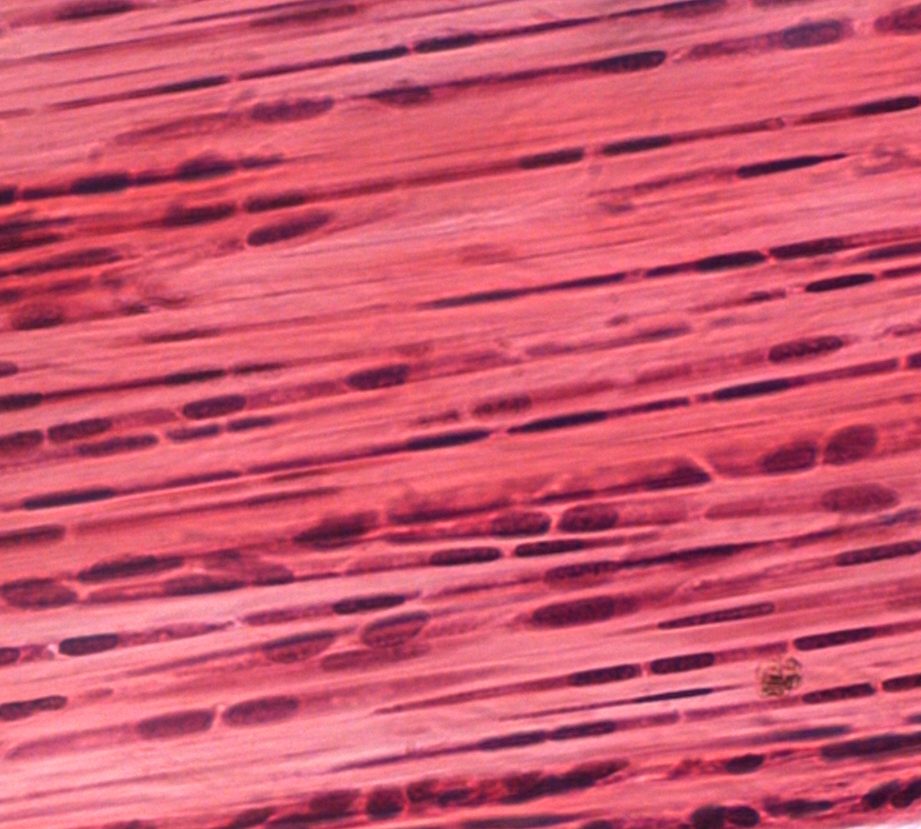

Figure 7.4.5 Microscopic view of loose fibrous connective tissue. - Dense Fibrous Connective Tissue: composed of a dense mat of parallel collagen fibres and a scattering of fibroblasts, creating a tissue that is very strong. Dense fibrous connective tissue forms tendons and ligaments, which connect bones to muscles and/or bones to neighbouring bones.

Figure 7.4.6 Dense fibrous connective tissue is composed of fibroblasts and a dense parallel packing of collagen fibres.

Figure 7.4.7 Microscopic view of dense fibrous connective tissue.

Supportive Connective Tissue

Supportive connective tissue exhibits the defining feature of connective tissue in that it is a scattering of cells in a non-cellular matrix; what sets it apart from other connective tissues is its solid matrix. In this tissue group, the matrix is solid- either bone or cartilage. While fibrous connective tissue contained cells called fibroblasts which produced fibres, supportive connective tissue contains cells that either create bone (osteocytes) or cells that create cartilage (chondrocytes).

Cartilage

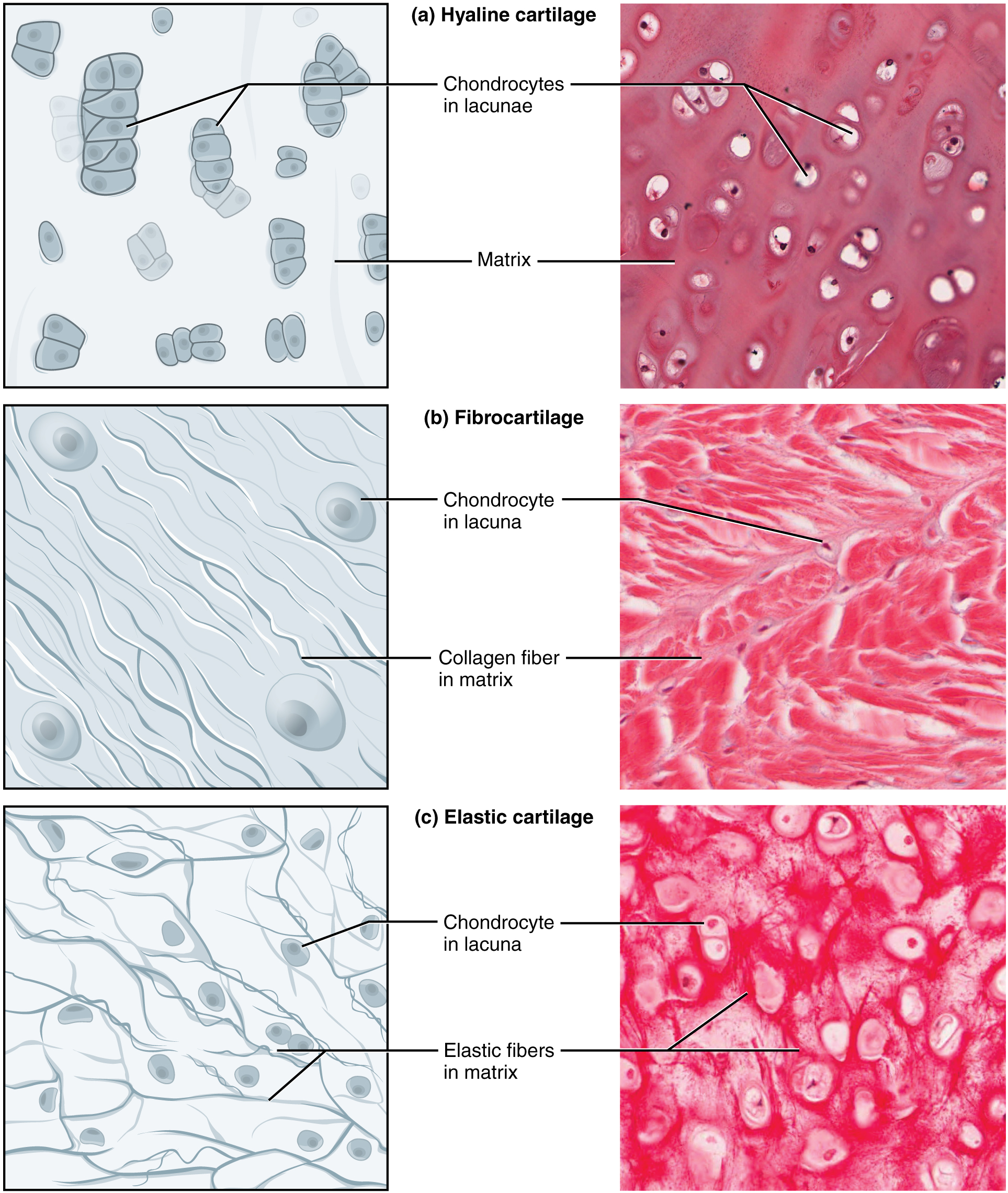

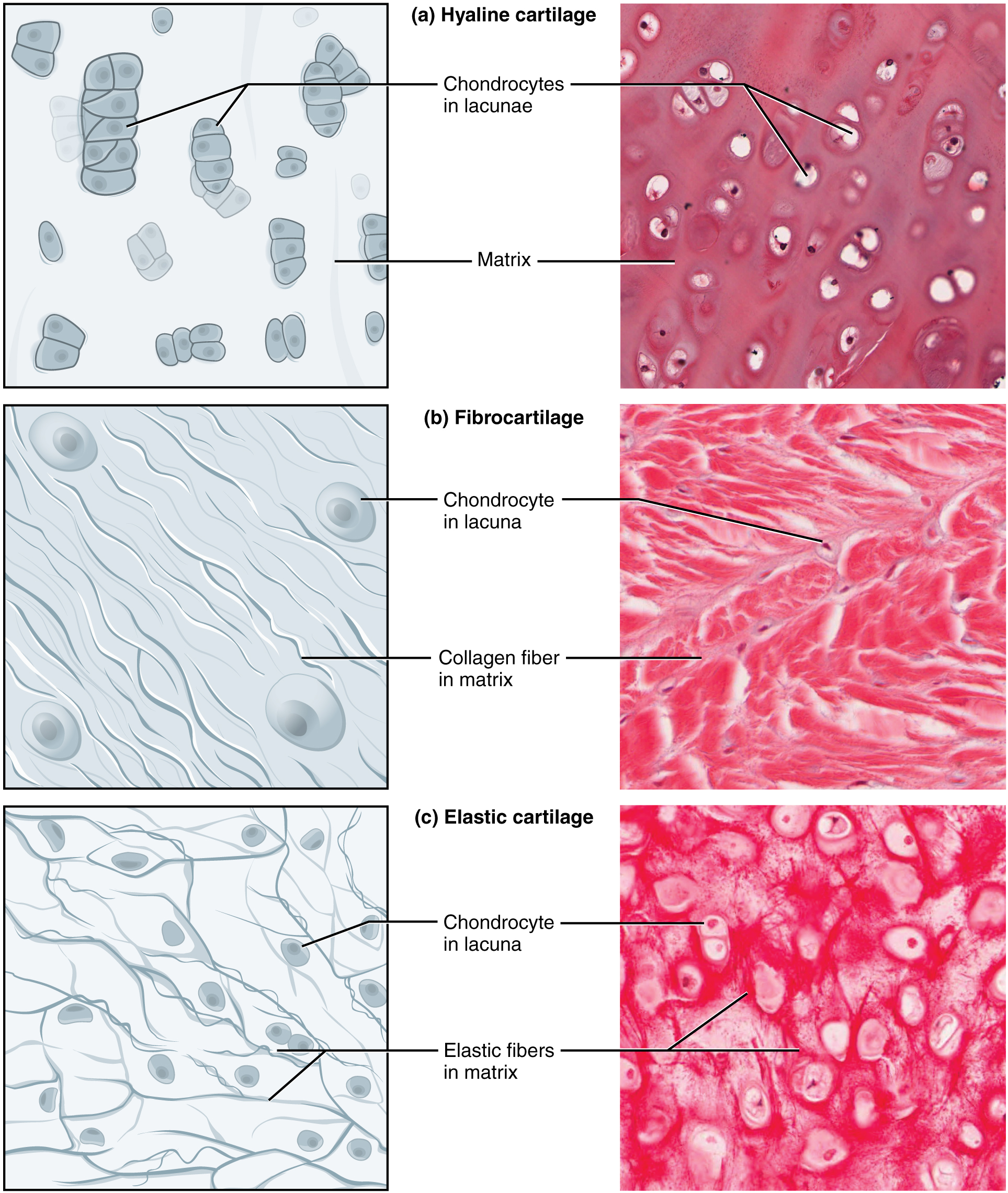

Chondrocytes produce the cartilage matrix in which they reside. Cartilage is made up of protein fibres and chondrocytes in lacunae. This is tissue is strong yet flexible and is used many places in the body for protection and support. Cartilage is one of the few tissues that is not vascular (doesn't have a direct blood supply) meaning it relies on diffusion to obtain nutrients and gases; this is the cause of slow healing rates in injuries involving cartilage. There are three main types of cartilage:

- Hyaline cartilage: a smooth, strong and flexible tissue. Found at the ends of ribs and long bones, in the nose, and comprising the entire fetal skeleton.

- Fibrocartilage: a very strong tissue containing thick bundles of collagen. Found in joints that need cushioning from high impact (knees, jaw).

- Elastic cartilage: contains elastic fibres in addition to collagen, giving support with the benefit of elasticity. Found in earlobes and the epiglottis.

Figure 7.4.8 Three types of cartilage, each with distinct characteristics based on the nature of the matrix.

Bone

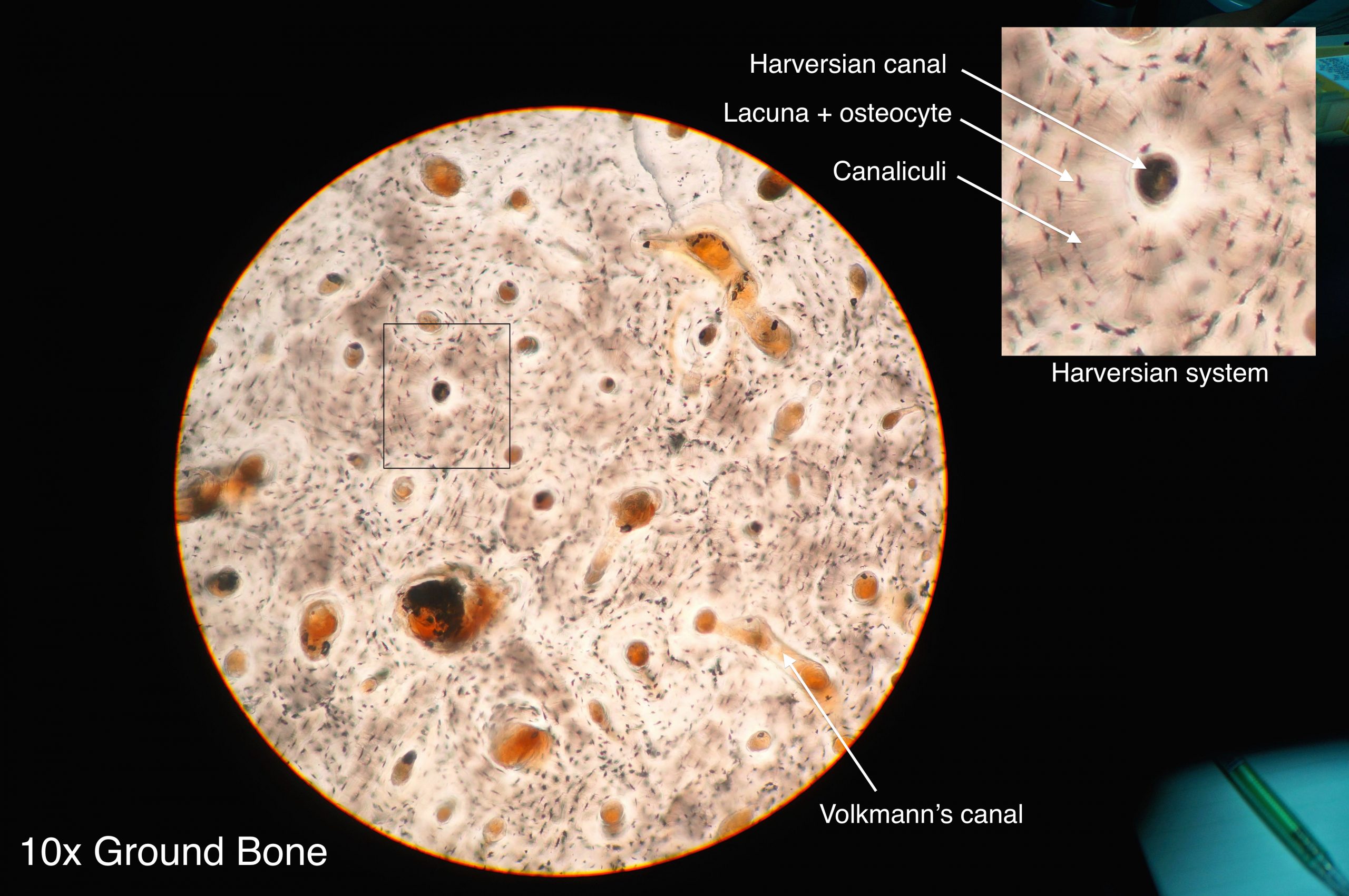

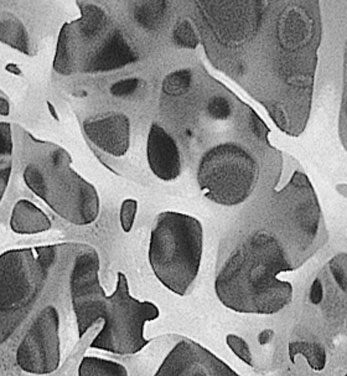

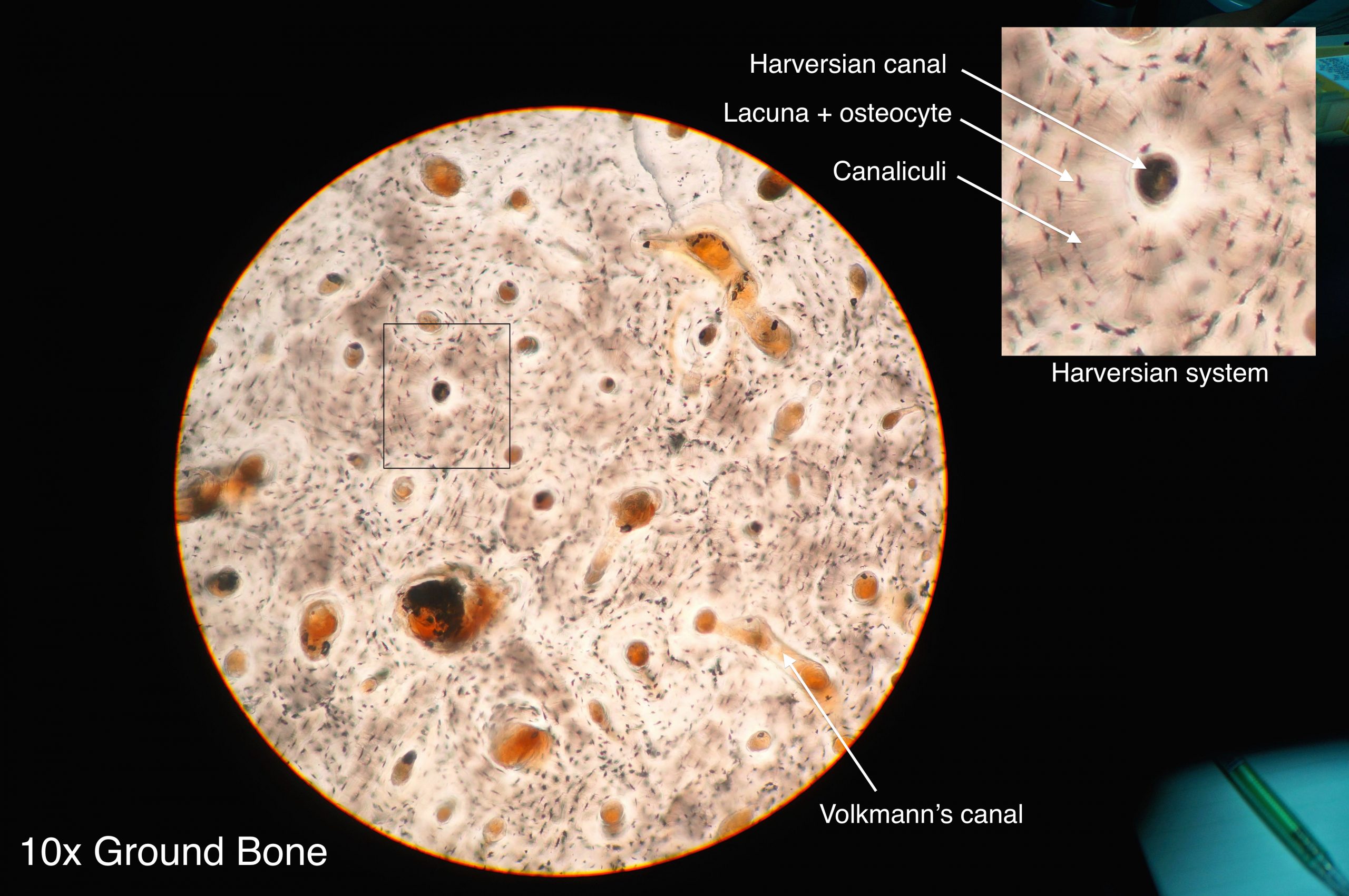

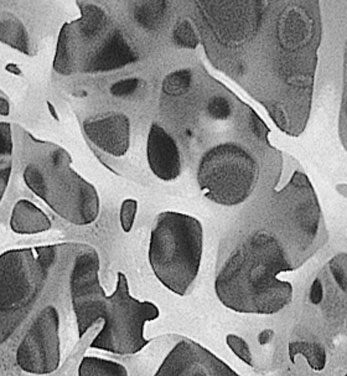

Osteocytes produce the bone matrix in which they reside. Since bone is very solid, these cells reside in small spaces called lacunae. This bone tissue is composed of collagen fibres embedded in calcium phosphate giving it strength without brittleness. There are two types of bone: compact and spongy.

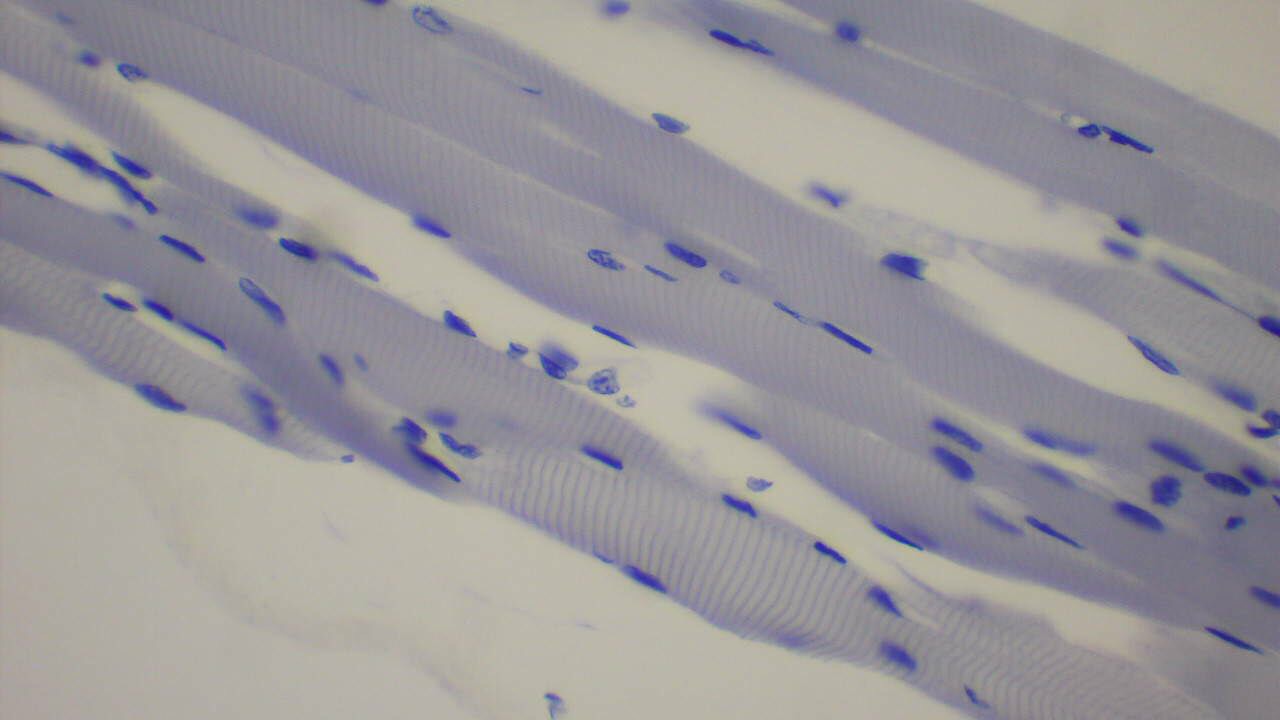

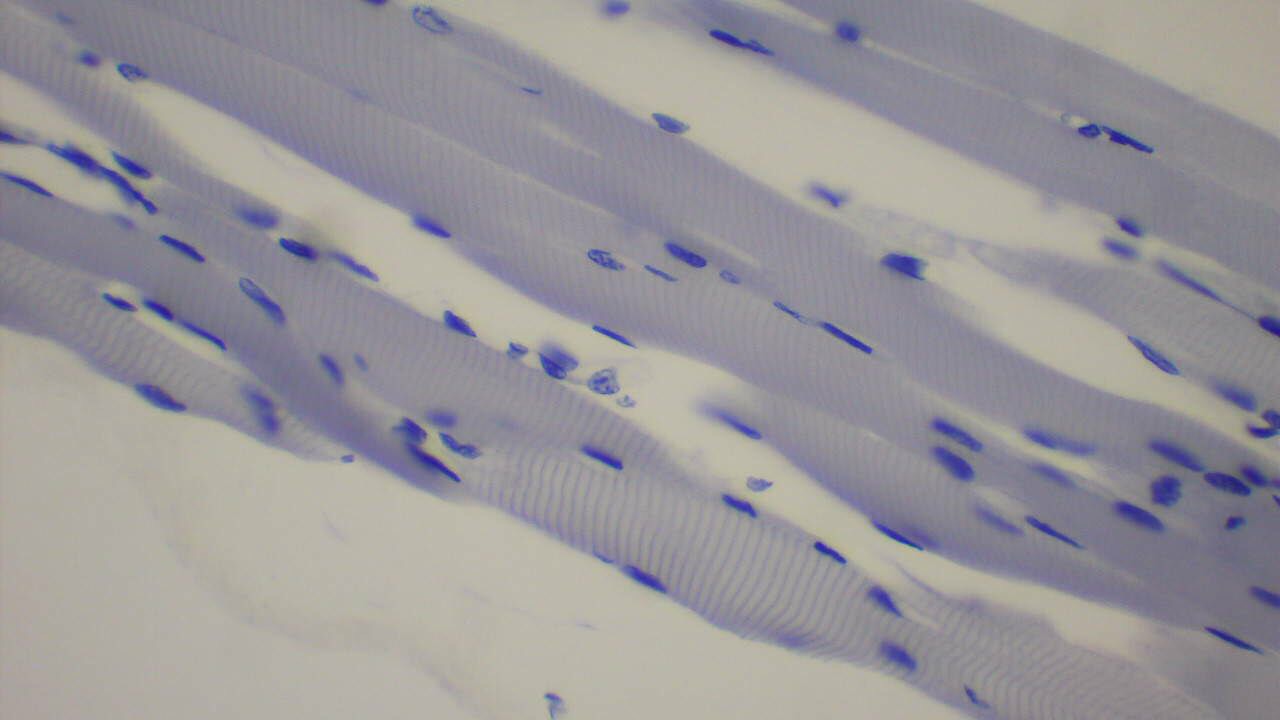

- Compact bone: has a dense matrix organized into cylindrical units called osteons. Each osteon contains a central canal (sometimes called a Harversian Canal) which allows for space for blood vessels and nerves, as well as concentric rings of bone matrix and osteocytes in lacunae, as per the diagram here. Compact bone is found in long bones and forms a shell around spongy bone.