12.2 Introduction to the Muscular System

Marvelous Muscles

Does the word muscle make you think of the well-developed muscles of a weightlifter, like the woman in Figure 12.2.1? Her name is Natalia Zabolotnaya, and she’s a Russian Olympian. The muscles that are used to lift weights are easy to feel and see, but they aren’t the only muscles in the human body. Many muscles are deep within the body, where they form the walls of internal organs and other structures. You can flex your biceps at will, but you can’t control internal muscles like these. It’s a good thing that these internal muscles work without any conscious effort on your part, because movement of these muscles is essential for survival. Muscles are the organs of the muscular system.

What Is the Muscular System?

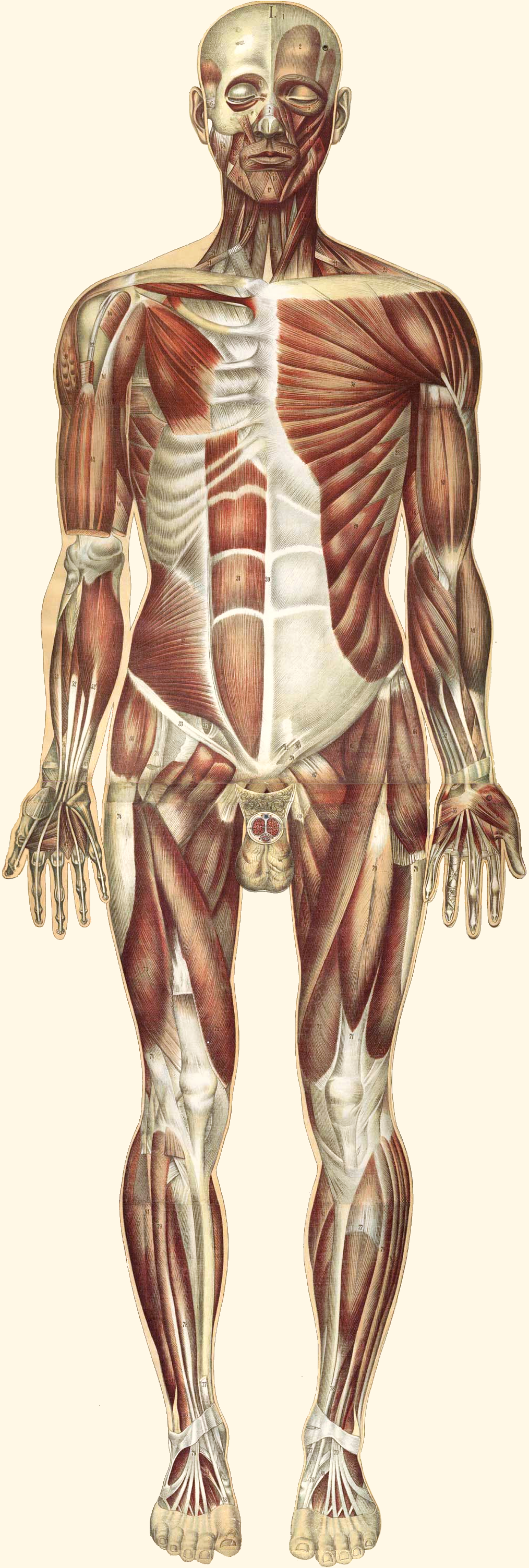

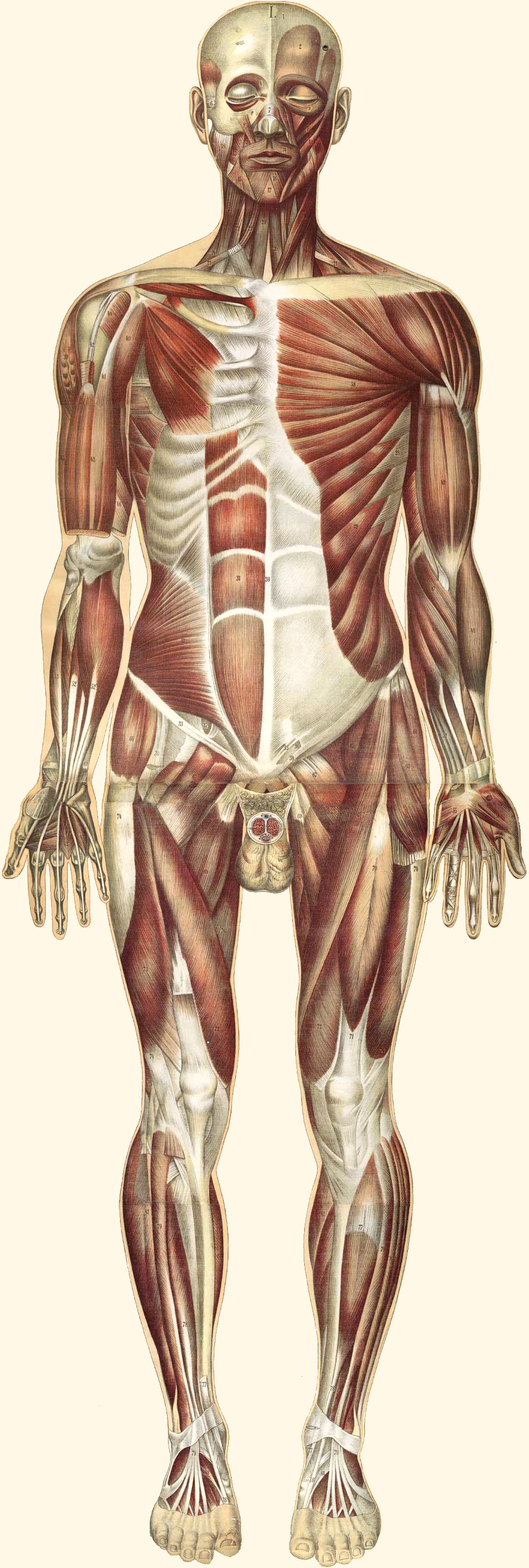

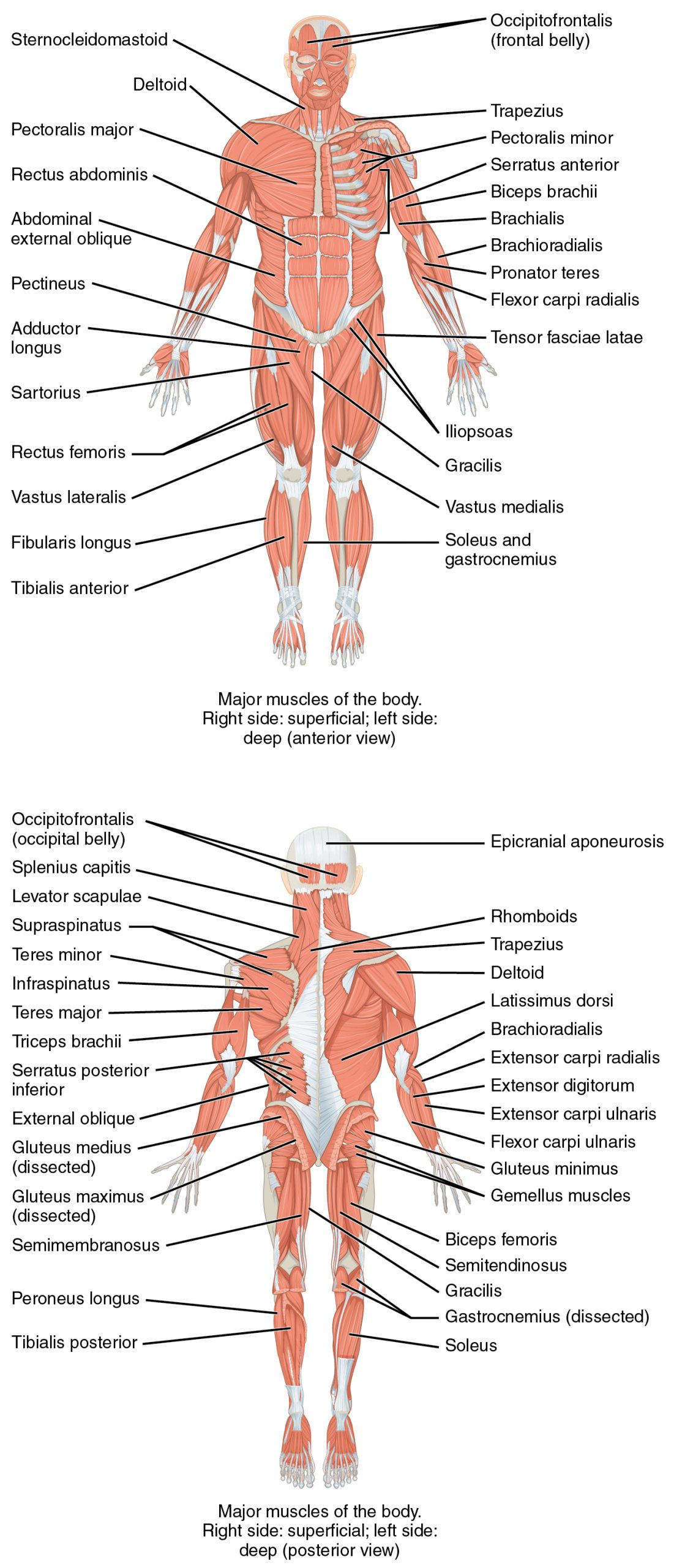

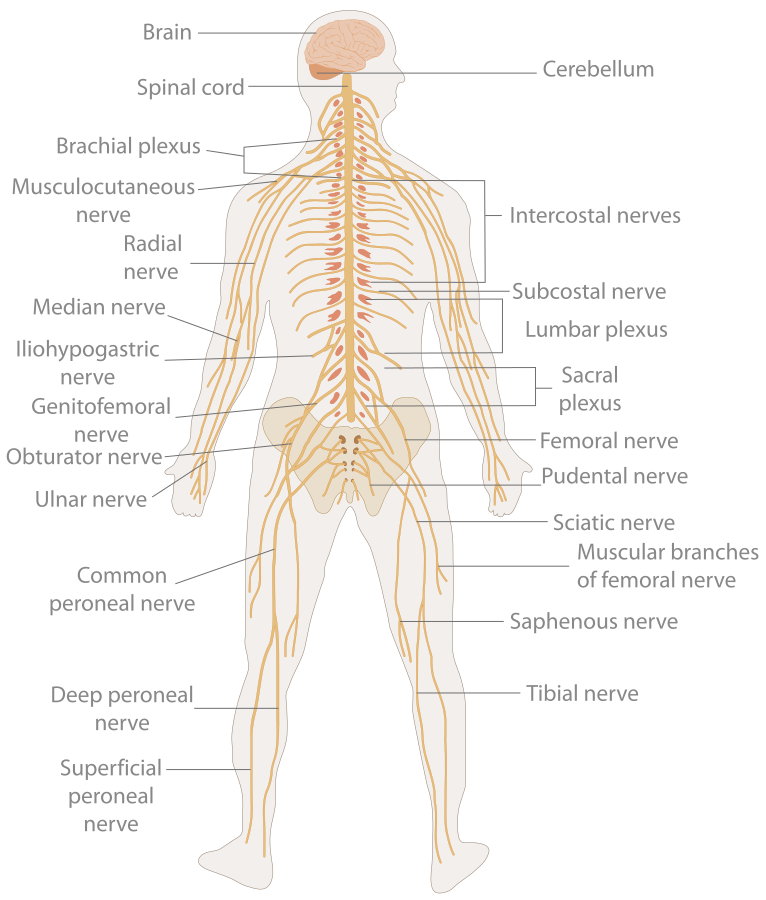

The muscular system consists of all the muscles of the body. The largest percentage of muscles in the muscular system consists of skeletal muscles, which are attached to bones and enable voluntary body movements (shown in Figure 12.2.2). There are almost 650 skeletal muscles in the human body, many of them shown in Figure 12.2.2. Besides skeletal muscles, the muscular system also includes cardiac muscle, which makes up the walls of the heart, and smooth muscles, which control movement in other internal organs and structures.

Muscle Structure and Function

Muscles are organs composed mainly of muscle cells, which are also called muscle fibres (mainly in skeletal and cardiac muscle) or myocytes (mainly in smooth muscle). Muscle cells are long, thin cells that are specialized for the function of contracting. They contain protein filaments that slide over one another using energy in ATP. The sliding filaments increase the tension in — or shorten the length of — muscle cells, causing a contraction. Muscle contractions are responsible for virtually all the movements of the body, both inside and out.

Skeletal muscles are attached to bones of the skeleton. When these muscles contract, they move the body. They allow us to use our limbs in a variety of ways, from walking to turning cartwheels. Skeletal muscles also maintain posture and help us to keep balance.

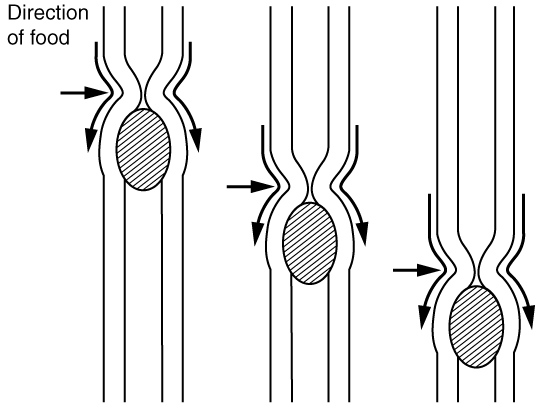

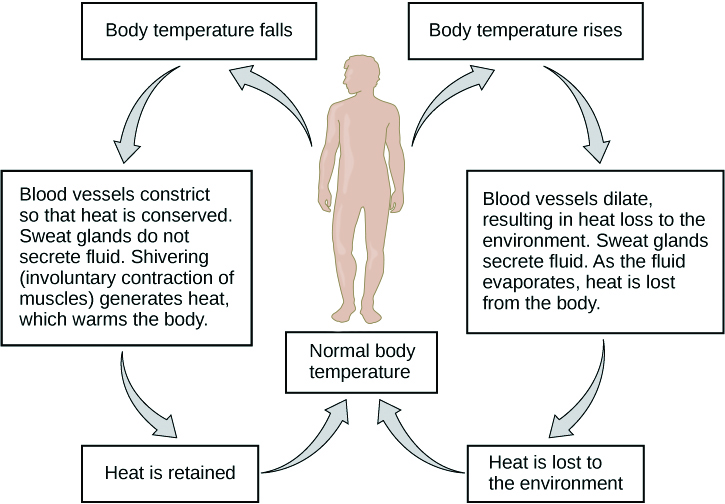

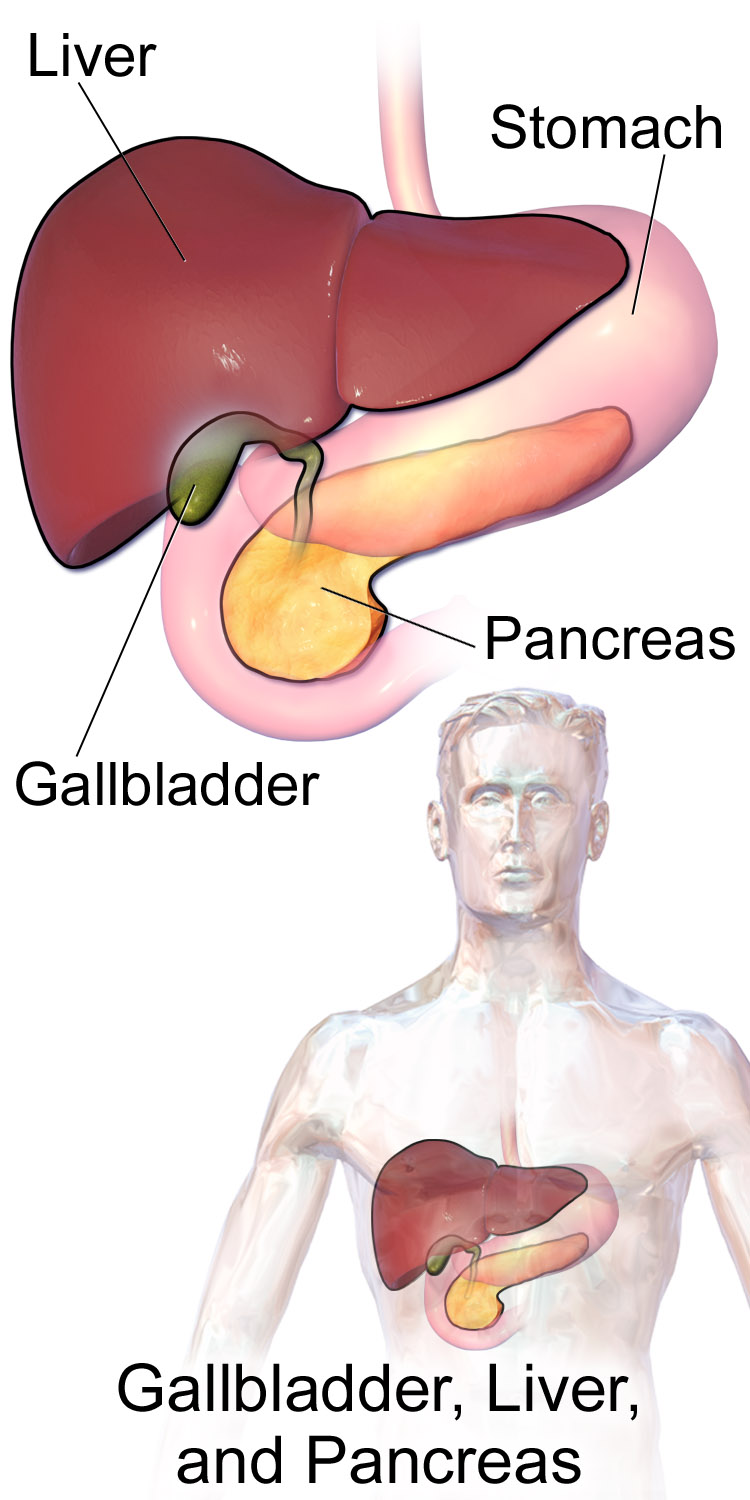

Smooth muscles in the walls of blood vessels contract to cause vasoconstriction, which may help conserve body heat. Relaxation of these muscles causes vasodilation, which may help the body lose heat. In the organs of the digestive system, smooth muscles squeeze food through the gastrointestinal tract by contracting in sequence to form a wave of muscle contractions called peristalsis. Think of squirting toothpaste through a tube by applying pressure in sequence from the bottom of the tube to the top, and you have a good idea of how food is moved by muscles through the digestive system. Peristalsis of smooth muscles also moves urine through the urinary tract.

Cardiac muscle tissue is found only in the walls of the heart. When cardiac muscle contracts, it makes the heart beat. The pumping action of the beating heart keeps blood flowing through the cardiovascular system.

Muscle Hypertrophy and Atrophy

Muscles can grow larger, or hypertrophy. This generally occurs through increased use, although hormonal or other influences can also play a role. The increase in testosterone that occurs in males during puberty, for example, causes a significant increase in muscle size. Physical exercise that involves weight bearing or resistance training can increase the size of skeletal muscles in virtually everyone. Exercises (such as running) that increase the heart rate may also increase the size and strength of cardiac muscle. The size of muscle, in turn, is the main determinant of muscle strength, which may be measured by the amount of force a muscle can exert.

Muscles can also grow smaller, or atrophy, which can occur through lack of physical activity or from starvation. People who are immobilized for any length of time — for example, because of a broken bone or surgery — lose muscle mass relatively quickly. People in concentration or famine camps may be so malnourished that they lose much of their muscle mass, becoming almost literally just “skin and bones.” Astronauts on the International Space Station may also lose significant muscle mass because of weightlessness in space (see Figure 12.2.3).

Many diseases, including cancer and AIDS, are often associated with muscle atrophy. Atrophy of muscles also happens with age. As people grow older, there is a gradual decrease in the ability to maintain skeletal muscle mass, known as sarcopenia. The exact cause of sarcopenia is not known, but one possible cause is a decrease in sensitivity to growth factors that are needed to maintain muscle mass. Because muscle size determines strength, muscle atrophy causes a corresponding decline in muscle strength.

In both hypertrophy and atrophy, the number of muscle fibres does not change. What changes is the size of the muscle fibres. When muscles hypertrophy, the individual fibres become wider. When muscles atrophy, the fibres become narrower.

Interactions with Other Body Systems

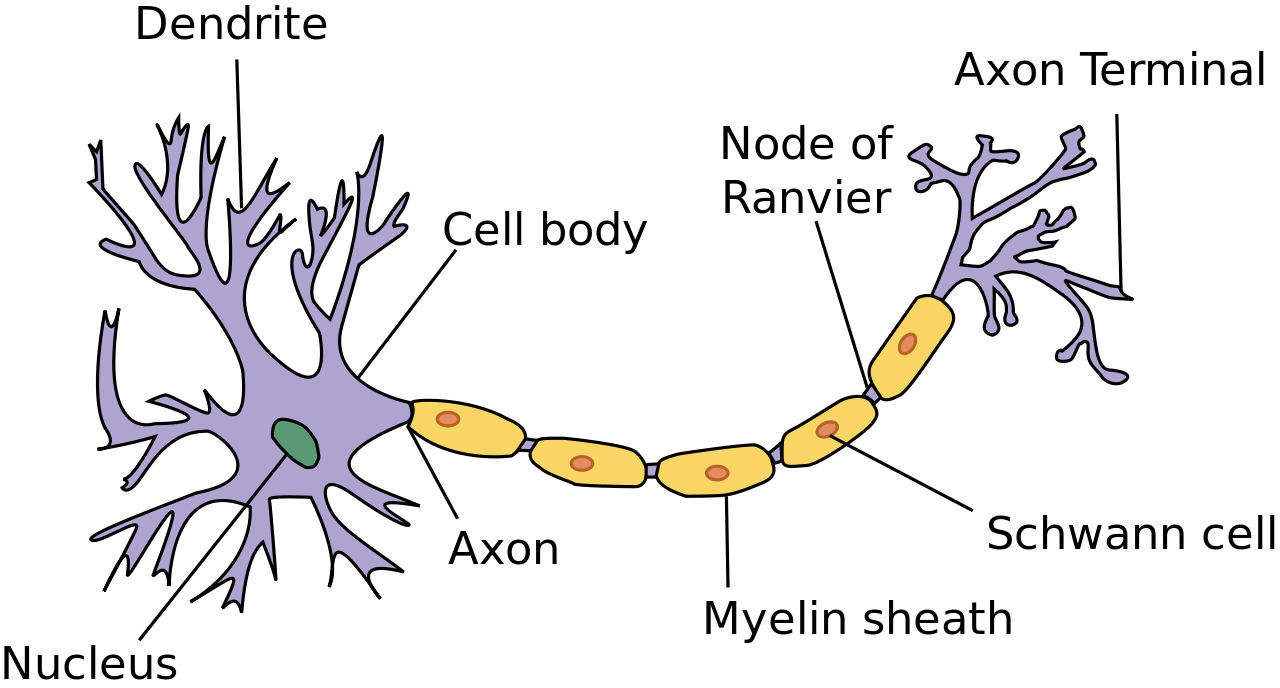

Muscles cannot contract on their own. Skeletal muscles need stimulation from motor neurons in order to contract. The point where a motor neuron attaches to a muscle is called a neuromuscular junction. Let’s say you decide to raise your hand in class. Your brain sends electrical messages through motor neurons to your arm and shoulder. The motor neurons, in turn, stimulate muscle fibres in your arm and shoulder to contract, causing your arm to rise.

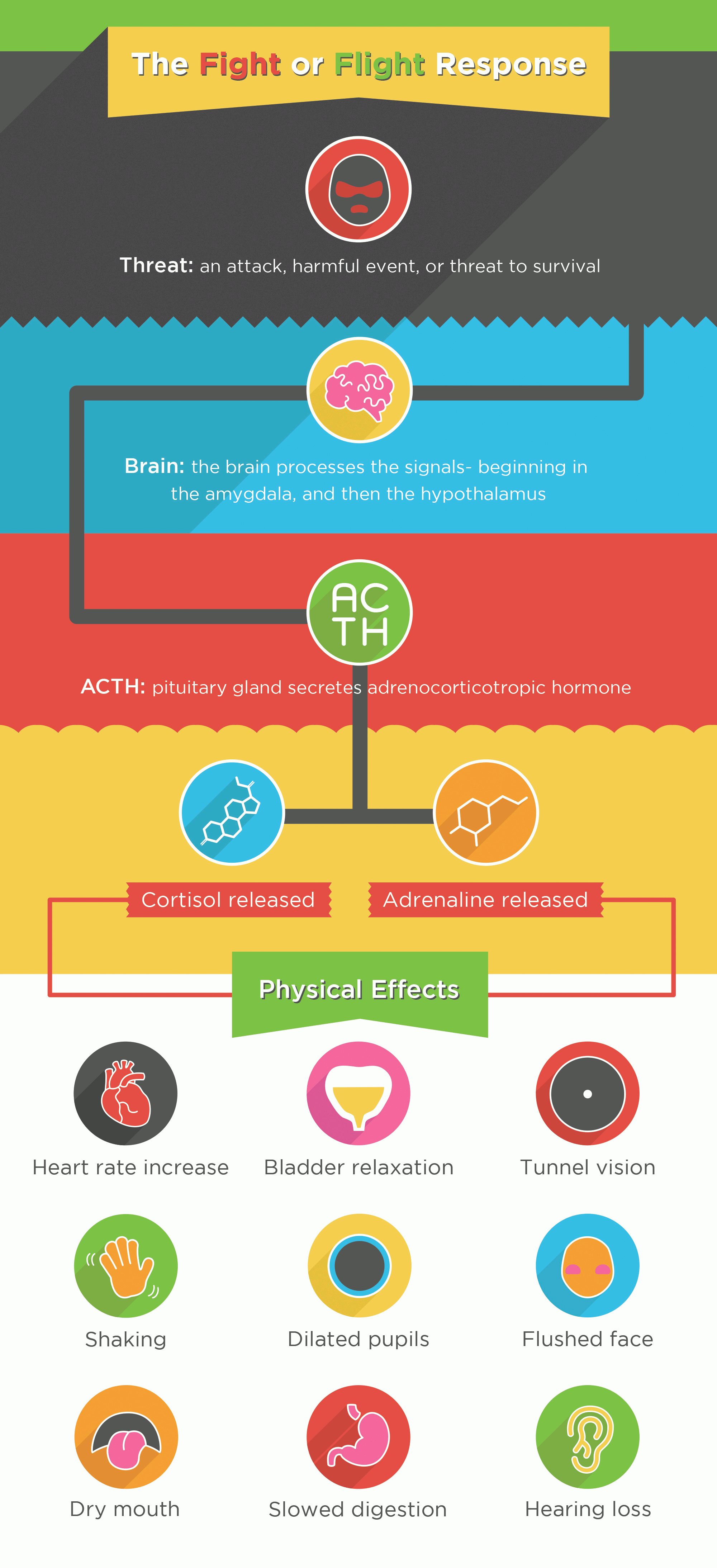

Involuntary contractions of smooth and cardiac muscles are also controlled by electrical impulses, but in the case of these muscles, the impulses come from the autonomic nervous system (smooth muscle) or specialized cells in the heart (cardiac muscle). Hormones and some other factors also influence involuntary contractions of cardiac and smooth muscles. For example, the fight-or-flight hormone adrenaline increases the rate at which cardiac muscle contracts, thereby speeding up the heartbeat.

Muscles cannot move the body on their own. They need the skeletal system to act upon. The two systems together are often referred to as the musculoskeletal system. Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton by tough connective tissues called tendons. Many skeletal muscles are attached to the ends of bones that meet at a joint. The muscles span the joint and connect the bones. When the muscles contract, they pull on the bones, causing them to move. The skeletal system provides a system of levers that allow body movement. The muscular system provides the force that moves the levers.

12.2 Summary

- The muscular system consists of all the muscles of the body. There are three types of muscle: skeletal muscle (which is attached to bones and enables voluntary body movements), cardiac muscle (which makes up the walls of the heart and makes it beat), and smooth muscle (which is found in the walls of internal organs and other internal structures and controls their movements).

- Muscles are organs composed mainly of muscle cells, which may also be called muscle fibres or myocytes. Muscle cells are specialized for the function of contracting, which occurs when protein filaments inside the cells slide over one another using energy in ATP.

- Muscles can grow larger, or hypertrophy. This generally occurs through increased use (physical exercise), although hormonal or other influences can also play a role. Muscles can also grow smaller, or atrophy. This may occur through lack of use, starvation, certain diseases, or aging. In both hypertrophy and atrophy, the size — but not the number — of muscle fibres changes. The size of muscles is the main determinant of muscle strength.

- Skeletal muscles need the stimulus of motor neurons to contract, and to move the body, they need the skeletal system to act upon. Involuntary contractions of cardiac and smooth muscles are controlled by special cells in the heart, nerves of the autonomic nervous system, hormones, or other factors.

12.2 Review Questions

- What is the muscular system?

- Describe muscle cells and their function.

- Identify three types of muscle tissue and where each type is found.

- Define muscle hypertrophy and muscle atrophy.

- What are some possible causes of muscle hypertrophy?

- Give three reasons that muscle atrophy may occur.

- How do muscles change when they increase or decrease in size?

- How do changes in muscle size affect strength?

- Explain why astronauts can easily lose muscle mass in space.

- Describe how the terms muscle cells, muscle fibres, and myocytes relate to each other.

-

- Name two systems in the body that work together with the muscular system to carry out movements.

- Describe one way in which the muscular system is involved in regulating body temperature.

12.2 Explore More

How your muscular system works – Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2017.

3D Medical Animation – Peristalsis in Large Intestine/Bowel || ABP ©, AnimatedBiomedical, 2013.

Muscle matters: Dr Brendan Egan at TEDxUCD, TEDx Talks, 2014.

Attributions

Figure 12.2.1

Natalia_Zabolotnaya_2012b by Simon Q on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 12.2.2

Bougle_whole2_retouched by Bouglé, Julien from the National LIbrary of Medicine (NLM) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 12.2.3

Daniel_Tani_iss016e027910 by NASA/ International Space Station Imagery on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

AnimatedBiomedical. (2013, January 30). 3D Medical animation – Peristalsis in large intestine/bowel || ABP ©. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ujr0UAbyPS4&feature=youtu.be

Bouglé, J. (1899). Le corps humain en grandeur naturelle : planches coloriées et superposées, avec texte explicatif. J. B. Baillière et fils. In Historical Anatomies on the Web. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/bougle_home.html

TED-Ed. (2017, October 26). How your muscular system works – Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVL-8zr2hk4&feature=youtu.be

TEDx Talks. (2014, June 27). Muscle matters: Dr Brendan Egan at TEDxUCD. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkXwfTsqQgQ&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 15). Natalya Zabolotnaya. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Natalya_Zabolotnaya&oldid=962630409

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

A Bag Full of Jell-O

The simple cut-away model of an animal cell (Figure 4.4.1) shows that a cell resembles a plastic bag full of Jell-O. Its basic structure is a plasma membrane filled with cytoplasm. Like Jell-O containing mixed fruit (Figure 4.4.2), the cytoplasm of the cell also contains various structures, including a nucleus and other organelles. Your body is composed of trillions of cells, but all of them perform the same basic life functions. They all obtain and use energy, respond to the environment, and reproduce. How do your cells carry out these basic functions and keep themselves — and you — alive? To answer these questions, you need to know more about the structures that make up cells, starting with the plasma membrane.

What is the Plasma Membrane?

The plasma membrane is a structure that forms a barrier between the cytoplasm inside the cell and the environment outside the cell. Without the plasma membrane, there would be no cell. Although it is very thin and flexible, the plasma membrane protects and supports the cell by controlling everything that enters and leaves it. It allows only certain substances to pass through, while keeping others in or out. To understand how the plasma membrane controls what passes into or out of the cell, you need to know its basic structure.

Phospholipid Bilayer

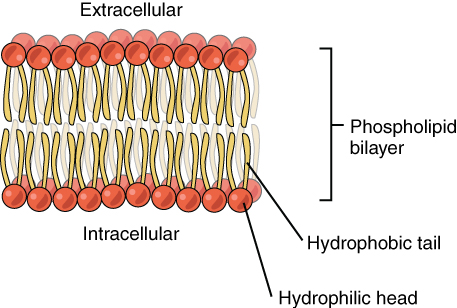

The plasma membrane is composed mainly of phospholipids, which consist of fatty acids and alcohol. The phospholipids in the plasma membrane are arranged in two layers, called a phospholipid bilayer. As shown in the simplified diagram in Figure 4.4.3, each individual phospholipid molecule has a phosphate group head (in red) and two fatty acid tails (in yellow). The head “loves” water (hydrophilic) and the tails “hate” water (hydrophobic). The water-hating tails are on the interior of the membrane, whereas the water-loving heads point outward, toward either the cytoplasm (intracellular) or the fluid that surrounds the cell (extracellular).

Hydrophobic molecules can easily pass through the plasma membrane if they are small enough, because they are water-hating like the interior of the membrane. Hydrophilic molecules, on the other hand, cannot pass through the plasma membrane — at least not without help — because they are water-loving like the exterior of the membrane.

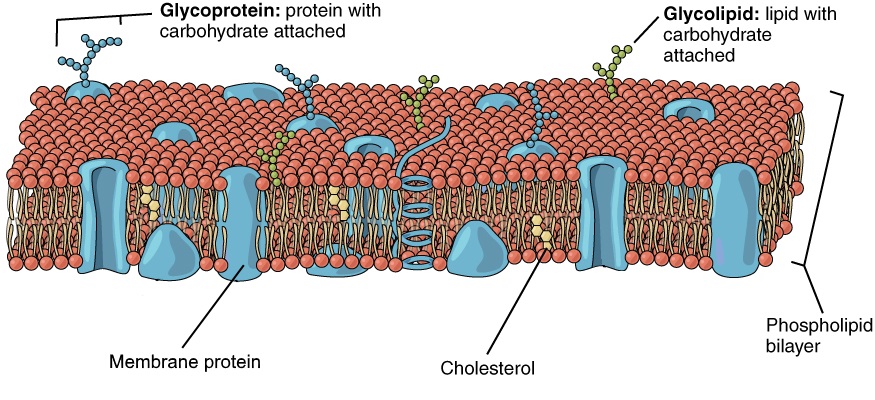

Other Molecules in the Plasma Membrane

The plasma membrane also contains other molecules, primarily other lipids and proteins. The yellow molecules in the diagram here, for example, are the lipid cholesterol. Molecules of the steroid lipid cholesterol help the plasma membrane keep its shape. Proteins in the plasma membrane (shown blue in Figure 4.4.4) include: transport proteins that assist other substances in crossing the cell membrane, receptors that allow the cell to respond to chemical signals in its environment, and cell-identity markers that indicate what type of cell it is and whether it belongs in the body.

Additional Functions of the Plasma Membrane

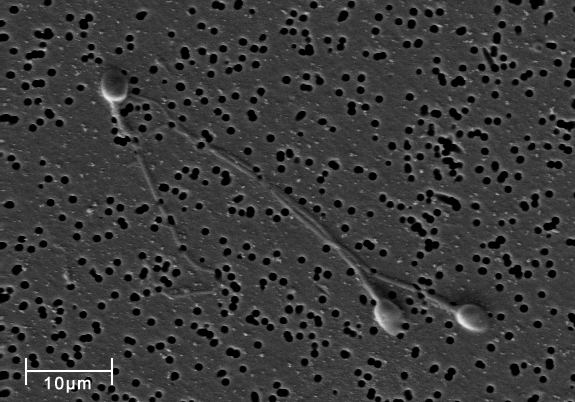

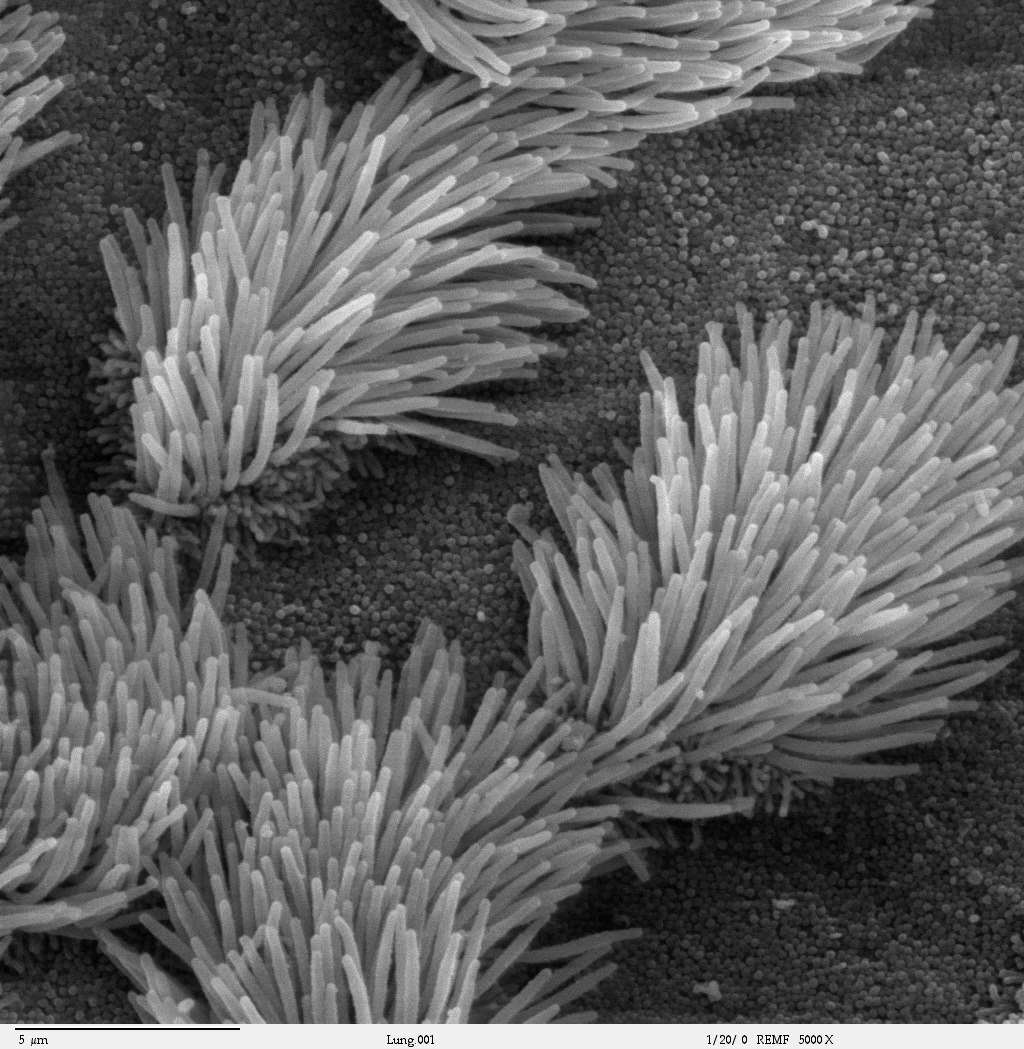

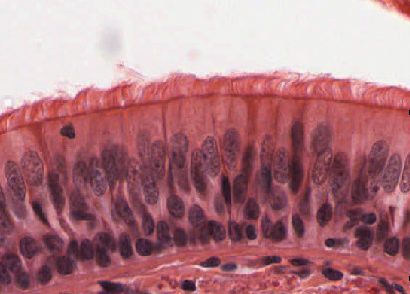

The plasma membrane may have extensions, such as whip-like flagella (singular flagellum) or brush-like cilia (singular cilium), shown below (Figure 4.4.5), that give it other functions. In single-celled organisms, these membrane extensions may help the organisms move. In multicellular organisms, the extensions have different functions. For example, the cilia on human lung cells sweep foreign particles and mucus toward the mouth and nose, while the flagellum on a human sperm cell allows it to swim.

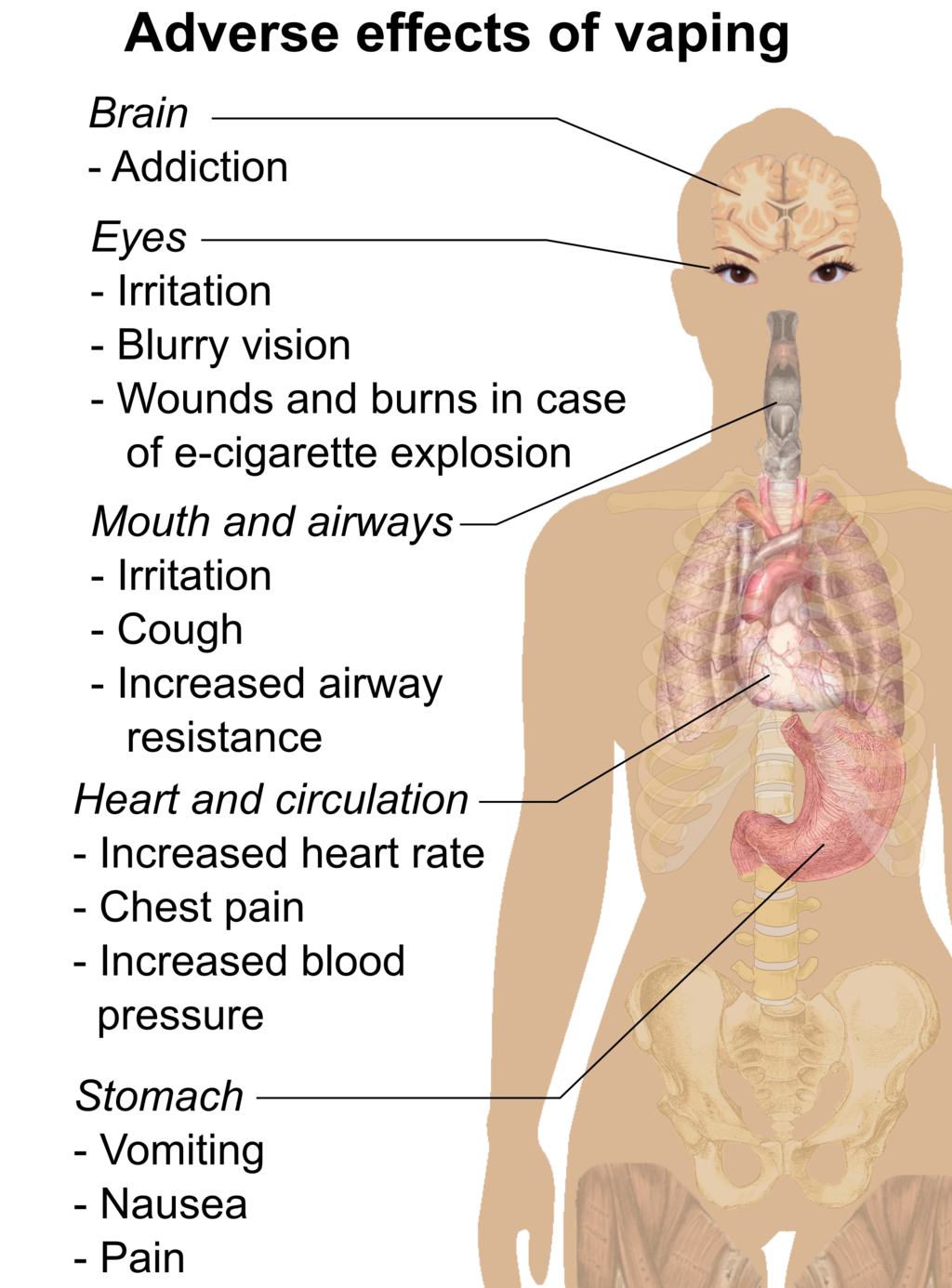

Feature: My Human Body

If you smoke or use e-cigarettes (vaping) and need another reason to quit, here's a good one. We usually think of lung cancer as the major disease caused by smoking. But smoking and vaping can have devastating effects on the body's ability to protect itself from repeated, serious respiratory infections, such as bronchitis and pneumonia.

Cilia are microscopic, hair-like projects on cells that line the respiratory, reproductive, and digestive systems. Cilia in the respiratory system line most of your airways, where they have the job of trapping and removing dust, germs, and other foreign particles before they can make you sick. Cilia secrete mucus that traps particles, and they move in a continuous wave-like motion that sweeps the mucus and particles upward toward the throat, where they can be expelled from the body. When you are sick and cough up phlegm, that's what you are doing.

Smoking prevents cilia from performing these important functions. Chemicals in tobacco smoke paralyze the cilia so they can't sweep mucus out of the airways. Those chemicals also inhibit the cilia from producing mucus. Fortunately, these effects start to wear off soon after the most recent exposure to tobacco smoke. If you stop smoking, your cilia will return to normal. Even if prolonged smoking has destroyed cilia, they will regrow and resume functioning in a matter of months after you stop smoking.

4.4 Summary

- The plasma membrane is a structure that forms a barrier between the cytoplasm inside the cell and the environment outside the cell. It allows only certain substances to pass in or out of the cell.

- The plasma membrane is composed mainly of a bilayer of phospholipid molecules. It also contains other molecules, such as the steroid cholesterol, which helps the membrane keep its shape, and transport proteins, which help substances pass through the membrane.

- The plasma membranes of some cells have extensions that have other functions, like flagella to help sperm move, or cilia to help keep our airways clear.

4.4 Review Questions

- What are the general functions of the plasma membrane?

- Describe the phospholipid bilayer of the plasma membrane.

- Identify other molecules in the plasma membrane. State their functions.

- Why do some cells have plasma membrane extensions, like flagella and cilia?

- Explain why hydrophilic molecules cannot easily pass through the cell membrane. What type of molecule in the cell membrane might help hydrophilic molecules pass through it?

- Which part of a phospholipid molecule in the plasma membrane is made of fatty acid chains? Is this part hydrophobic or hydrophilic?

- The two layers of phospholipids in the plasma membrane are called a phospholipid ____________.

-

- Steroid hormones can pass directly through cell membranes. Why do you think this is the case?

- Some antibiotics work by making holes in the plasma membrane of bacterial cells. How do you think this kills the cells?

- What is the name of the long, whip-like extensions of the plasma membrane that helps some single-celled organisms move?

4.4 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAXnYcUjn5k&feature=emb_logo

Insights into cell membranes via dish detergent - Ethan Perlstein, TED-Ed, 2013.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBCVVszQQNs

Inside the cell membrane, by The Amoeba Sisters, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 4.4.1

Animal Cell Unannotated, by Kelvin Song on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en) public domain dedication license.

Figure 4.4.2

Jello mold at the mexican bakery photo by Aimée Knight on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 4.4.3

Phospholipid_Bilayer by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 4.4.4

Lipid bilayer by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 4.4.5

Spermatozoa-human-3140x by No specific author on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.4.6

Cilia/ Bronchiolar epithelium 3 - SEM by Charles Daghlian on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.4.7

Adverse effects of vaping (raster) by Mikael Häggström on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2018, February 27). Inside the cell membrane. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qBCVVszQQNs&feature=youtu.be

Betts, J.G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E.. Womble, M., DeSaix. P. (2013, April 25). Figure 3.3 Phospolipid Bilayer [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/3-1-the-cell-membrane

Betts, J.G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E.. Womble, M., DeSaix. P. (2013, April 25). Figure 3.4 Cell Membrane [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/3-1-the-cell-membrane

Ghosh, A., Coakley, R. C., Mascenik, T., Rowell, T. R., Davis, E. S., Rogers, K., Webster, M. J., Dang, H., Herring, L. E., Sassano, M. F., Livraghi-Butrico, A., Van Buren, S. K., Graves, L. M., Herman, M. A., Randell, S. H., Alexis, N. E., & Tarran, R. (n.d.). Chronic E-Cigarette Exposure Alters the Human Bronchial Epithelial Proteome. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical /Care Medicine, 198(1), 67–76. https://doi-org.ezproxy.tru.ca/10.1164/rccm.201710-2033OC

TED-Ed. (2013, February 26). Insights into cell membranes via dish detergent - Ethan Perlstein. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yAXnYcUjn5k&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Marvelous Muscles

Does the word muscle make you think of the well-developed muscles of a weightlifter, like the woman in Figure 12.2.1? Her name is Natalia Zabolotnaya, and she’s a Russian Olympian. The muscles that are used to lift weights are easy to feel and see, but they aren’t the only muscles in the human body. Many muscles are deep within the body, where they form the walls of internal organs and other structures. You can flex your biceps at will, but you can’t control internal muscles like these. It’s a good thing that these internal muscles work without any conscious effort on your part, because movement of these muscles is essential for survival. Muscles are the organs of the muscular system.

What Is the Muscular System?

The muscular system consists of all the muscles of the body. The largest percentage of muscles in the muscular system consists of skeletal muscles, which are attached to bones and enable voluntary body movements (shown in Figure 12.2.2). There are almost 650 skeletal muscles in the human body, many of them shown in Figure 12.2.2. Besides skeletal muscles, the muscular system also includes cardiac muscle, which makes up the walls of the heart, and smooth muscles, which control movement in other internal organs and structures.

Muscle Structure and Function

Muscles are organs composed mainly of muscle cells, which are also called muscle fibres (mainly in skeletal and cardiac muscle) or myocytes (mainly in smooth muscle). Muscle cells are long, thin cells that are specialized for the function of contracting. They contain protein filaments that slide over one another using energy in ATP. The sliding filaments increase the tension in — or shorten the length of — muscle cells, causing a contraction. Muscle contractions are responsible for virtually all the movements of the body, both inside and out.

Skeletal muscles are attached to bones of the skeleton. When these muscles contract, they move the body. They allow us to use our limbs in a variety of ways, from walking to turning cartwheels. Skeletal muscles also maintain posture and help us to keep balance.

Smooth muscles in the walls of blood vessels contract to cause vasoconstriction, which may help conserve body heat. Relaxation of these muscles causes vasodilation, which may help the body lose heat. In the organs of the digestive system, smooth muscles squeeze food through the gastrointestinal tract by contracting in sequence to form a wave of muscle contractions called peristalsis. Think of squirting toothpaste through a tube by applying pressure in sequence from the bottom of the tube to the top, and you have a good idea of how food is moved by muscles through the digestive system. Peristalsis of smooth muscles also moves urine through the urinary tract.

Cardiac muscle tissue is found only in the walls of the heart. When cardiac muscle contracts, it makes the heart beat. The pumping action of the beating heart keeps blood flowing through the cardiovascular system.

Muscle Hypertrophy and Atrophy

Muscles can grow larger, or hypertrophy. This generally occurs through increased use, although hormonal or other influences can also play a role. The increase in testosterone that occurs in males during puberty, for example, causes a significant increase in muscle size. Physical exercise that involves weight bearing or resistance training can increase the size of skeletal muscles in virtually everyone. Exercises (such as running) that increase the heart rate may also increase the size and strength of cardiac muscle. The size of muscle, in turn, is the main determinant of muscle strength, which may be measured by the amount of force a muscle can exert.

Muscles can also grow smaller, or atrophy, which can occur through lack of physical activity or from starvation. People who are immobilized for any length of time — for example, because of a broken bone or surgery — lose muscle mass relatively quickly. People in concentration or famine camps may be so malnourished that they lose much of their muscle mass, becoming almost literally just “skin and bones.” Astronauts on the International Space Station may also lose significant muscle mass because of weightlessness in space (see Figure 12.2.3).

Many diseases, including cancer and AIDS, are often associated with muscle atrophy. Atrophy of muscles also happens with age. As people grow older, there is a gradual decrease in the ability to maintain skeletal muscle mass, known as sarcopenia. The exact cause of sarcopenia is not known, but one possible cause is a decrease in sensitivity to growth factors that are needed to maintain muscle mass. Because muscle size determines strength, muscle atrophy causes a corresponding decline in muscle strength.

In both hypertrophy and atrophy, the number of muscle fibres does not change. What changes is the size of the muscle fibres. When muscles hypertrophy, the individual fibres become wider. When muscles atrophy, the fibres become narrower.

Interactions with Other Body Systems

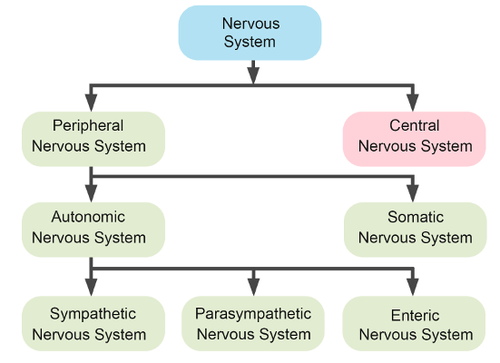

Muscles cannot contract on their own. Skeletal muscles need stimulation from motor neurons in order to contract. The point where a motor neuron attaches to a muscle is called a neuromuscular junction. Let’s say you decide to raise your hand in class. Your brain sends electrical messages through motor neurons to your arm and shoulder. The motor neurons, in turn, stimulate muscle fibres in your arm and shoulder to contract, causing your arm to rise.

Involuntary contractions of smooth and cardiac muscles are also controlled by electrical impulses, but in the case of these muscles, the impulses come from the autonomic nervous system (smooth muscle) or specialized cells in the heart (cardiac muscle). Hormones and some other factors also influence involuntary contractions of cardiac and smooth muscles. For example, the fight-or-flight hormone adrenaline increases the rate at which cardiac muscle contracts, thereby speeding up the heartbeat.

Muscles cannot move the body on their own. They need the skeletal system to act upon. The two systems together are often referred to as the musculoskeletal system. Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton by tough connective tissues called tendons. Many skeletal muscles are attached to the ends of bones that meet at a joint. The muscles span the joint and connect the bones. When the muscles contract, they pull on the bones, causing them to move. The skeletal system provides a system of levers that allow body movement. The muscular system provides the force that moves the levers.

12.2 Summary

- The muscular system consists of all the muscles of the body. There are three types of muscle: skeletal muscle (which is attached to bones and enables voluntary body movements), cardiac muscle (which makes up the walls of the heart and makes it beat), and smooth muscle (which is found in the walls of internal organs and other internal structures and controls their movements).

- Muscles are organs composed mainly of muscle cells, which may also be called muscle fibres or myocytes. Muscle cells are specialized for the function of contracting, which occurs when protein filaments inside the cells slide over one another using energy in ATP.

- Muscles can grow larger, or hypertrophy. This generally occurs through increased use (physical exercise), although hormonal or other influences can also play a role. Muscles can also grow smaller, or atrophy. This may occur through lack of use, starvation, certain diseases, or aging. In both hypertrophy and atrophy, the size — but not the number — of muscle fibres changes. The size of muscles is the main determinant of muscle strength.

- Skeletal muscles need the stimulus of motor neurons to contract, and to move the body, they need the skeletal system to act upon. Involuntary contractions of cardiac and smooth muscles are controlled by special cells in the heart, nerves of the autonomic nervous system, hormones, or other factors.

12.2 Review Questions

- What is the muscular system?

- Describe muscle cells and their function.

- Identify three types of muscle tissue and where each type is found.

- Define muscle hypertrophy and muscle atrophy.

- What are some possible causes of muscle hypertrophy?

- Give three reasons that muscle atrophy may occur.

- How do muscles change when they increase or decrease in size?

- How do changes in muscle size affect strength?

- Explain why astronauts can easily lose muscle mass in space.

- Describe how the terms muscle cells, muscle fibres, and myocytes relate to each other.

-

- Name two systems in the body that work together with the muscular system to carry out movements.

- Describe one way in which the muscular system is involved in regulating body temperature.

12.2 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVL-8zr2hk4

How your muscular system works - Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ujr0UAbyPS4&feature=emb_logo

3D Medical Animation - Peristalsis in Large Intestine/Bowel || ABP ©, AnimatedBiomedical, 2013.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkXwfTsqQgQ&feature=emb_logo

Muscle matters: Dr Brendan Egan at TEDxUCD, TEDx Talks, 2014.

Attributions

Figure 12.2.1

Natalia_Zabolotnaya_2012b by Simon Q on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 12.2.2

Bougle_whole2_retouched by Bouglé, Julien from the National LIbrary of Medicine (NLM) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 12.2.3

Daniel_Tani_iss016e027910 by NASA/ International Space Station Imagery on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

AnimatedBiomedical. (2013, January 30). 3D Medical animation - Peristalsis in large intestine/bowel || ABP ©. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ujr0UAbyPS4&feature=youtu.be

Bouglé, J. (1899). Le corps humain en grandeur naturelle : planches coloriées et superposées, avec texte explicatif. J. B. Baillière et fils. In Historical Anatomies on the Web. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/bougle_home.html

TED-Ed. (2017, October 26). How your muscular system works - Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VVL-8zr2hk4&feature=youtu.be

TEDx Talks. (2014, June 27). Muscle matters: Dr Brendan Egan at TEDxUCD. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkXwfTsqQgQ&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 15). Natalya Zabolotnaya. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Natalya_Zabolotnaya&oldid=962630409

Involuntary, striated muscle found only in the walls of the heart; also called myocardium.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Work Those Eye Muscles!

Imagine the man in Figure 12.3.1 turns his eyes in your direction. This is a very small movement, considering the conspicuously large and strong external eye muscles that control eyeball movements. These muscles have been called the strongest muscles in the human body relative to the work they do. However, the external eye muscles actually do a surprising amount of work. Eye movements occur almost constantly during waking hours, especially when we are scanning faces or reading. Eye muscles are also exercised nightly during the phase of sleep called rapid eye movement sleep. External eye muscles can move the eyes because they are made mainly of muscle tissue.

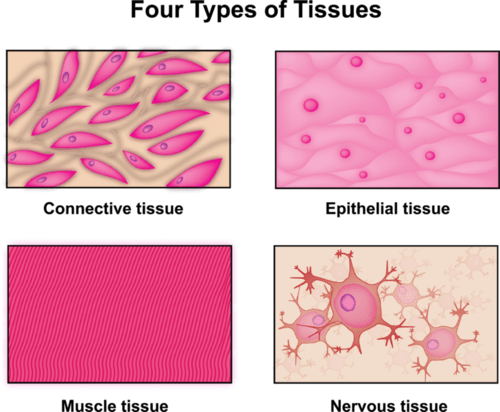

What is Muscle Tissue?

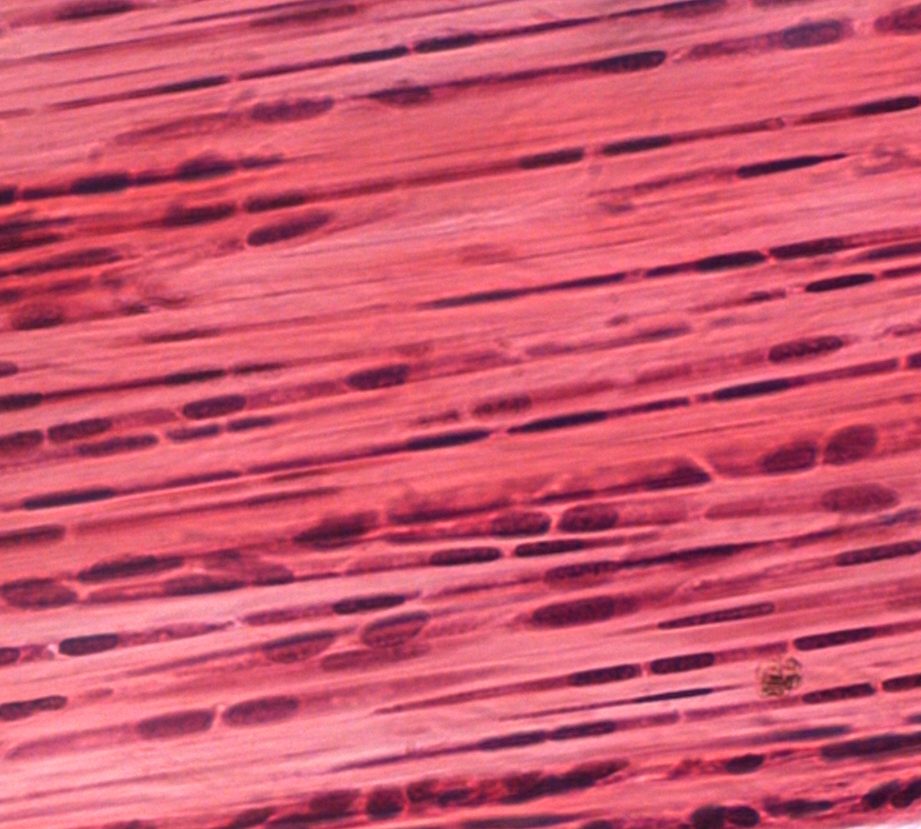

Muscle tissue is a soft tissue that makes up most of the tissues in the muscles of the human muscular system. Other tissues in muscles are connective tissues, such as tendons that attach skeletal muscles to bones and sheaths of connective tissues that cover or line muscle tissues. Only muscle tissue per se, has cells with the ability to contract.

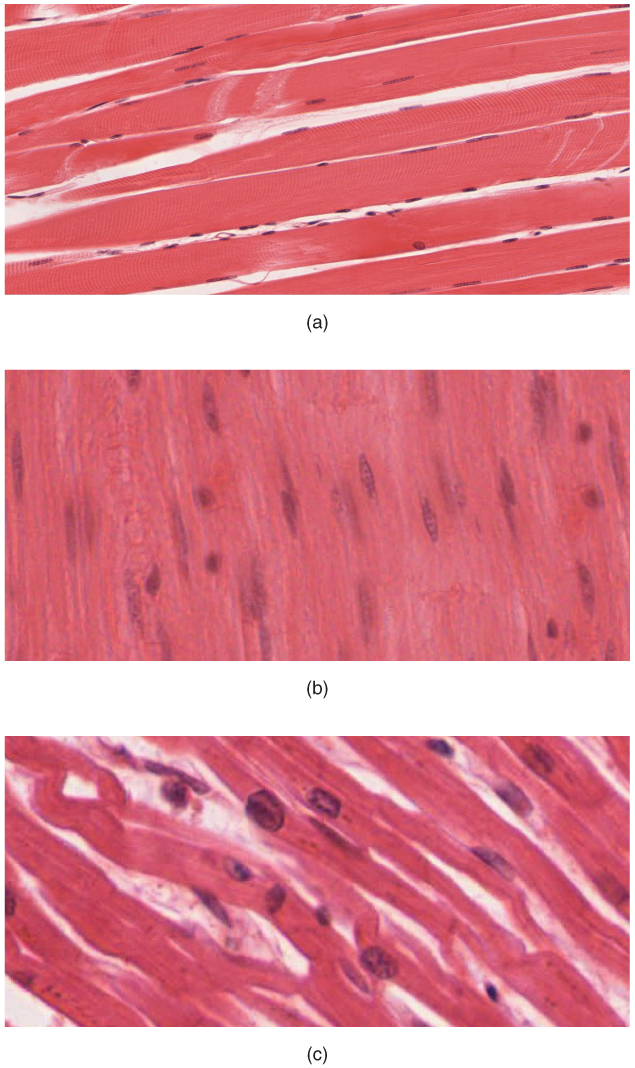

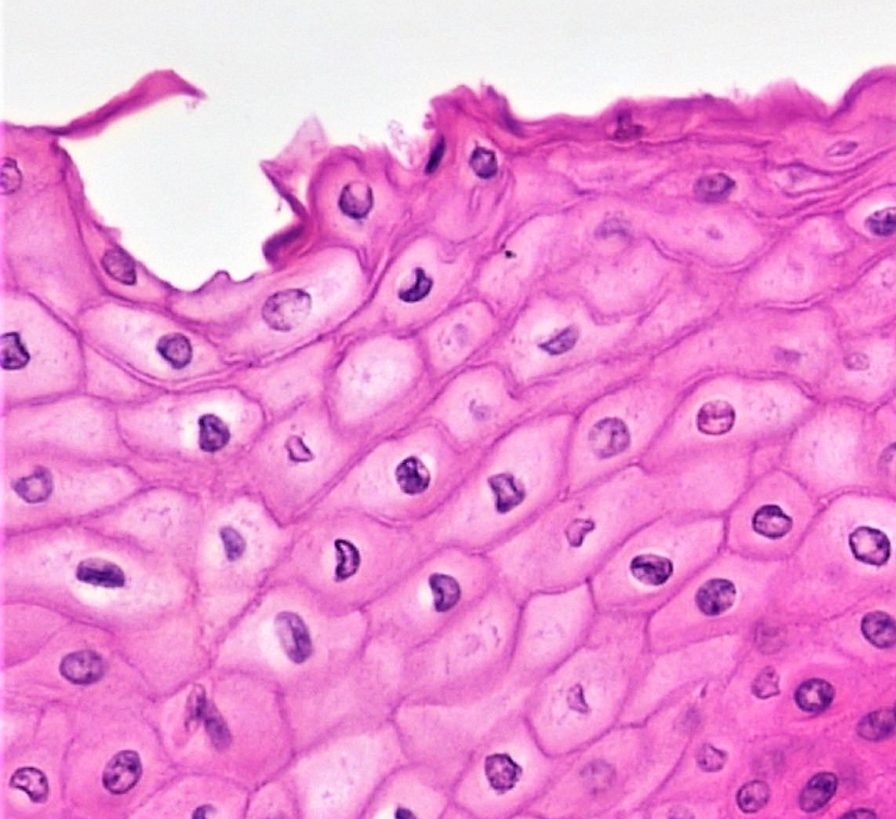

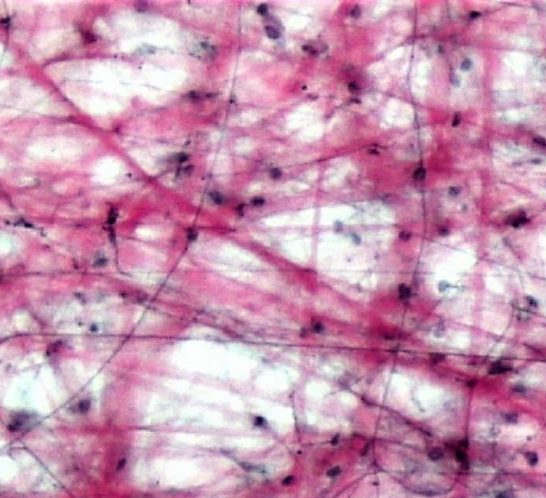

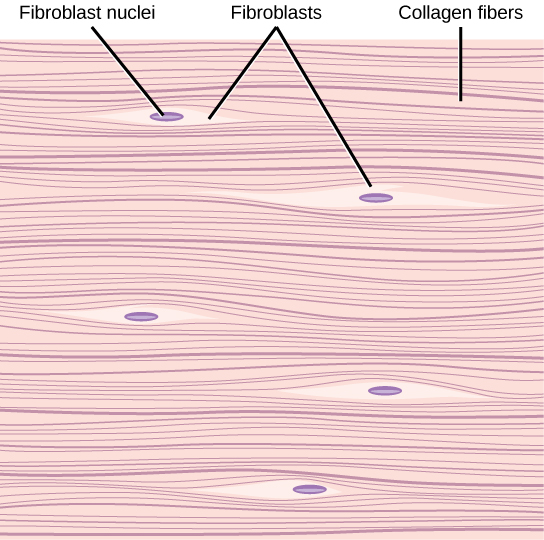

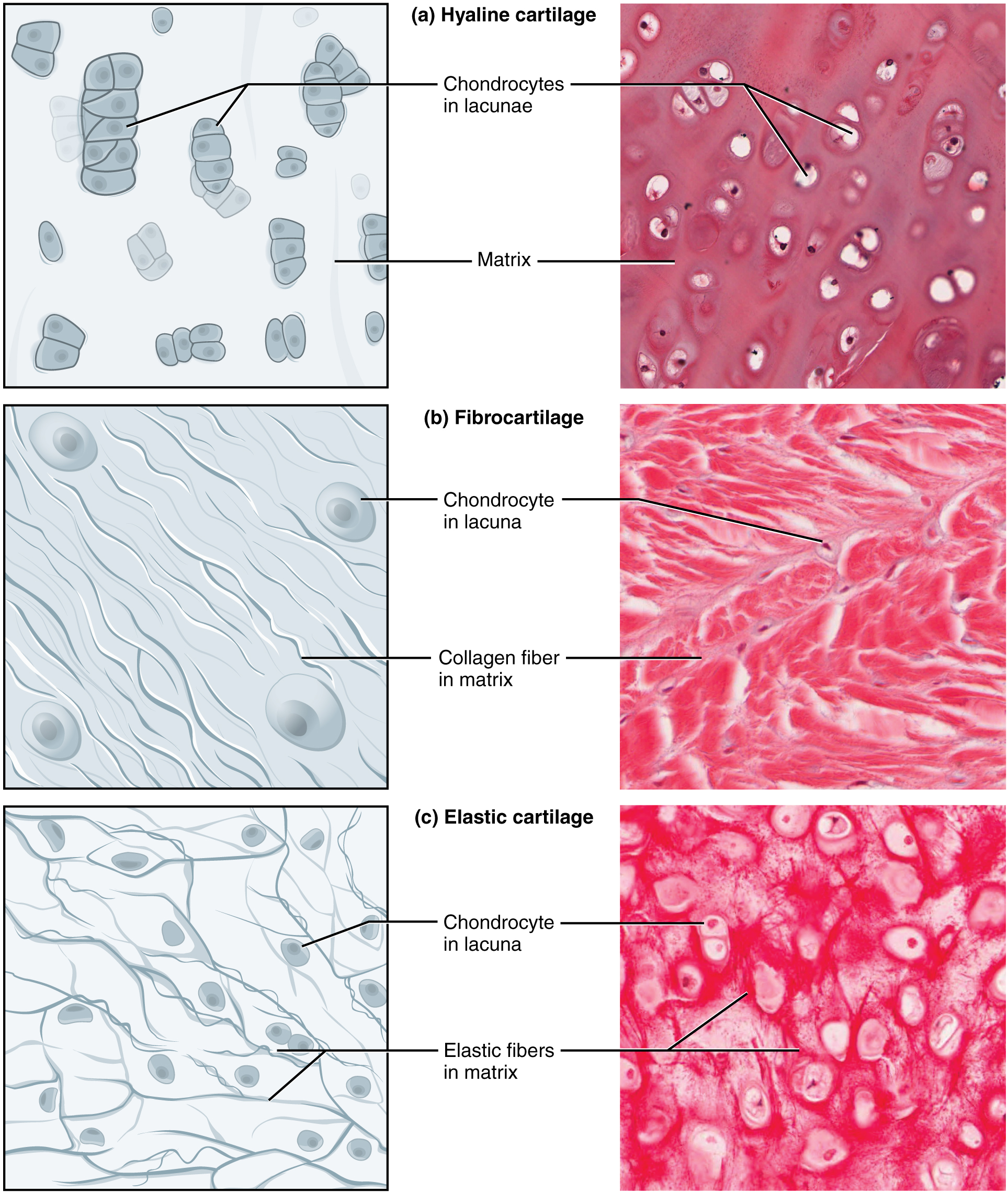

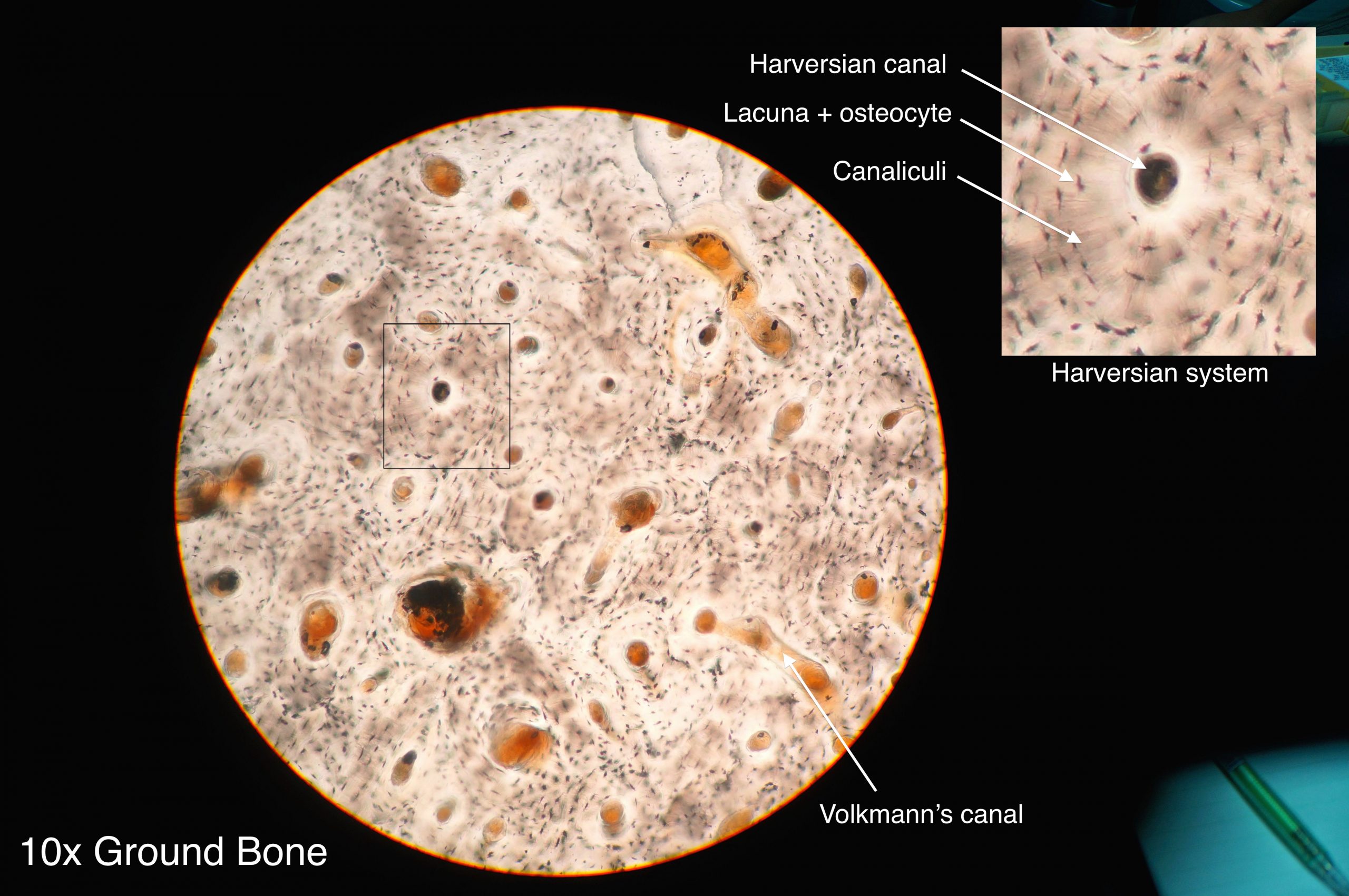

There are three major types of muscle tissues in the human body: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscle tissues. Figure 12.3.2 shows how the three types of muscle tissues appear under magnification. When you read about each type below, you will learn why the three types appear as they do.

Skeletal Muscle Tissue

Skeletal muscle is muscle tissue that is attached to bones by tendons, which are bundles of collagen fibres. Whether you are moving your eyes or running a marathon, you are using skeletal muscles. Contractions of skeletal muscles are voluntary, or under conscious control of the central nervous system via the somatic nervous system. Skeletal muscle tissue is the most common type of muscle tissue in the human body. By weight, an average adult male is about 42% skeletal muscles, and the average adult female is about 36% skeletal muscles. Some of the major skeletal muscles in the human body are labeled in Figure 12.3.3 below.

Skeletal Muscle Pairs

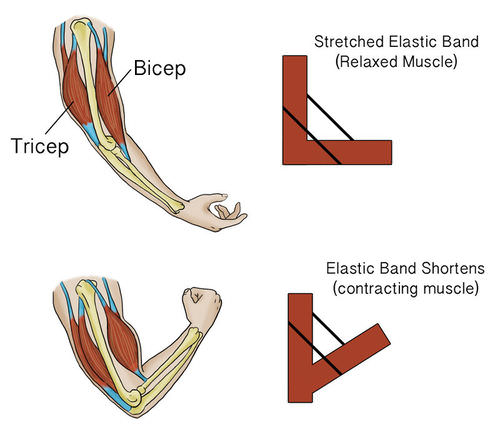

To move bones in opposite directions, skeletal muscles often consist of muscle pairs that work in opposition to one another, also called antagonistic muscle pairs. For example, when the biceps muscle (on the front of the upper arm) contracts, it can cause the elbow joint to flex or bend the arm, as shown in Figure 12.3.4. When the triceps muscle (on the back of the upper arm) contracts, it can cause the elbow to extend or straighten the arm. The biceps and triceps muscles, also shown in Figure 12.3.4, are an example of a muscle pair where the muscles work in opposition to each other.

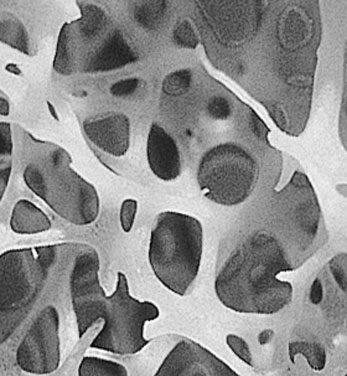

Skeletal Muscle Structure

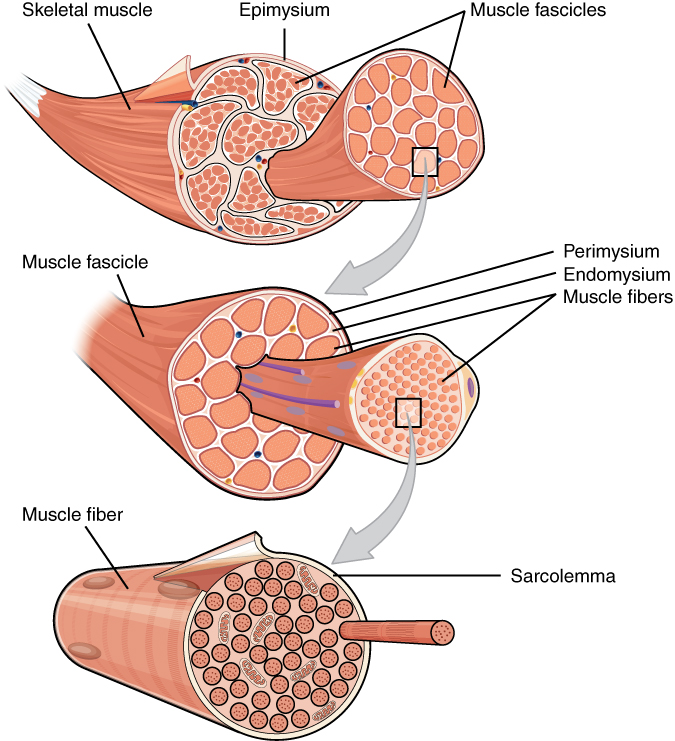

Each skeletal muscle consists of hundreds — or even thousands — of skeletal muscle fibres, which are long, string-like cells. As shown in Figure 12.3.5 below, skeletal muscle fibres are individually wrapped in connective tissue called endomysium. The skeletal muscle fibres are bundled together in units called muscle fascicles, which are surrounded by sheaths of connective tissue called perimysium. Each fascicle contains between ten and 100 (or even more!) skeletal muscle fibres. Fascicles, in turn, are bundled together to form individual skeletal muscles, which are wrapped in connective tissue called epimysium. The connective tissues in skeletal muscles have a variety of functions. They support and protect muscle fibres, allowing them to withstand the forces of contraction by distributing the forces applied to the muscle. They also provide pathways for nerves and blood vessels to reach the muscles. In addition, the epimysium anchors the muscles to tendons.

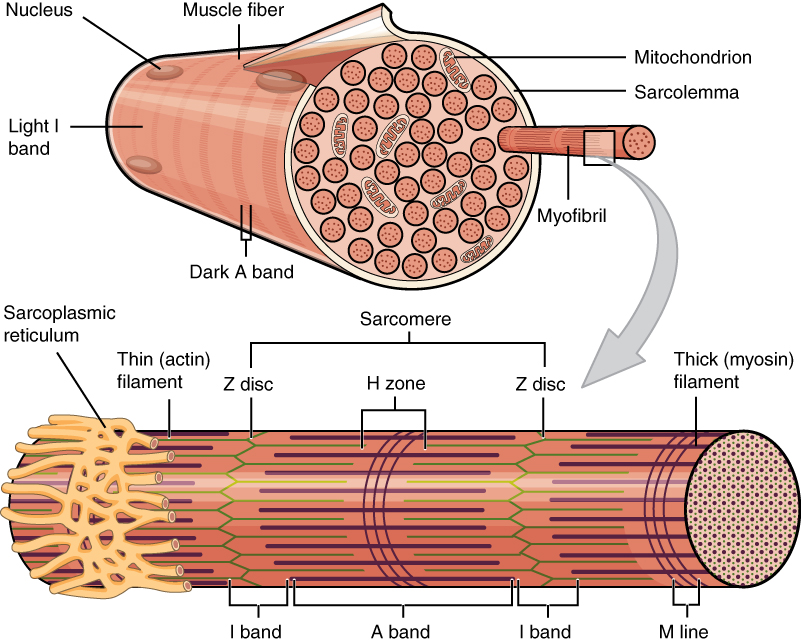

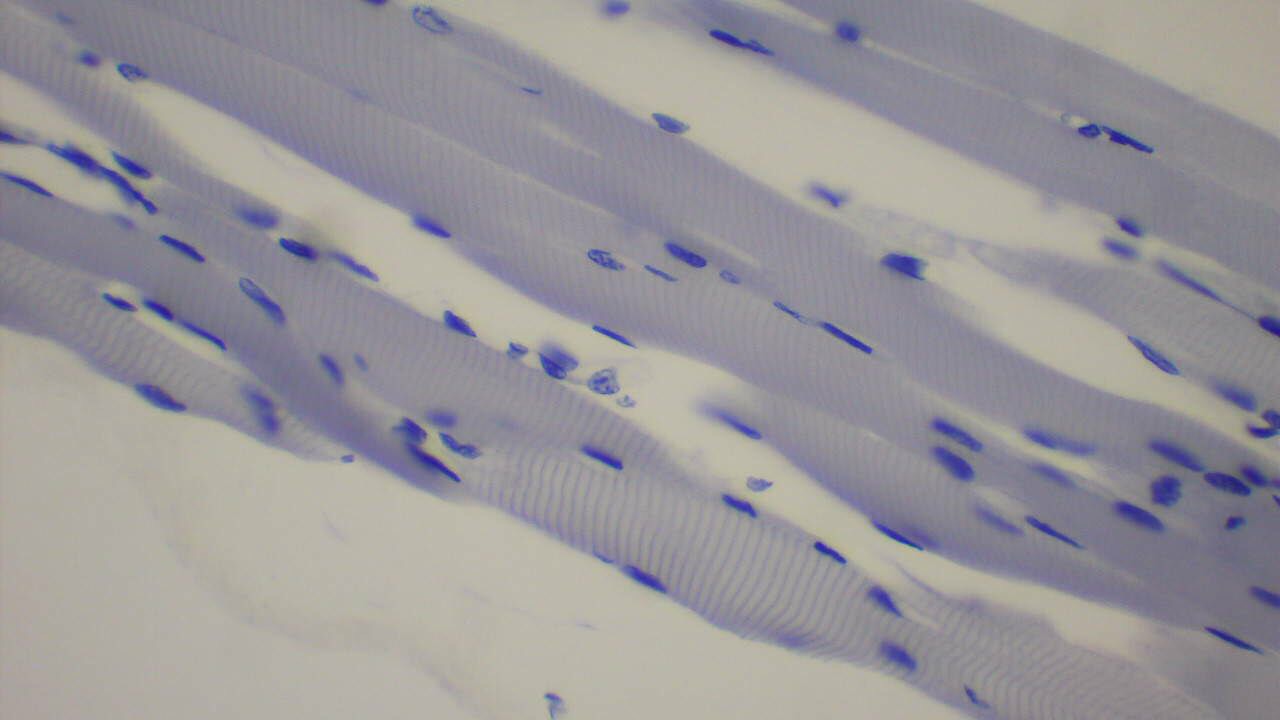

The same bundles-within-bundles structure is replicated within each muscle fibre. As shown in Figure 12.3.6, a muscle fibre consists of a bundle of myofibrils, which are themselves bundles of protein filaments. These protein filaments consist of thin filaments of the protein actin, which are anchored to structures called Z discs, and thick filaments of the protein myosin. The filaments are arranged together within a myofibril in repeating units called sarcomeres, which run from one Z disc to the next. The sarcomere is the basic functional unit of skeletal and cardiac muscles. It contracts as actin and myosin filaments slide over one another. Skeletal muscle tissue is said to be striated, because it appears striped. It has this appearance because of the regular, alternating A (dark) and I (light) bands of filaments arranged in sarcomeres inside the muscle fibres. Other components of a skeletal muscle fibre include multiple nuclei and mitochondria.

Slow- and Fast-Twitch Skeletal Muscle Fibres

Skeletal muscle fibres can be divided into two types, called slow-twitch (or type I) muscle fibres and fast-twitch (or type II) muscle fibres.

- Slow-twitch muscle fibres are dense with capillaries and rich in mitochondria and myoglobin, which is a protein that stores oxygen until needed for muscle activity. Relative to fast-twitch fibres, slow-twitch fibres can carry more oxygen and sustain aerobic (oxygen-using) activity. Slow-twitch fibres can contract for long periods of time, but not with very much force. They are relied upon primarily in endurance events, such as distance running or cycling.

- Fast-twitch muscle fibres contain fewer capillaries and mitochondria and less myoglobin. This type of muscle fibre can contract rapidly and powerfully, but it fatigues very quickly. Fast-twitch fibres can sustain only short, anaerobic (non-oxygen-using) bursts of activity. Relative to slow-twitch fibres, fast-twitch fibres contribute more to muscle strength and have a greater potential for increasing in mass. They are relied upon primarily in short, strenuous events, such as sprinting or weightlifting.

Proportions of fibre types vary considerably from muscle to muscle and from person to person. Individuals may be genetically predisposed to have a larger percentage of one type of muscle fibre than the other. Generally, an individual who has more slow-twitch fibres is better suited for activities requiring endurance, whereas an individual who has more fast-twitch fibres is better suited for activities requiring short bursts of power.

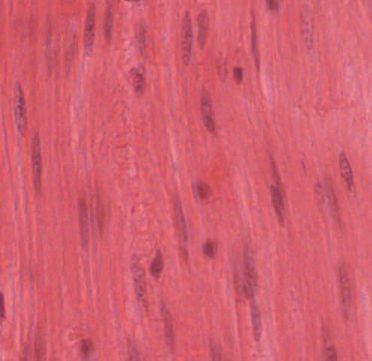

Smooth Muscle

Smooth muscle is muscle tissue in the walls of internal organs and other internal structures such as blood vessels. When smooth muscles contract, they help the organs and vessels carry out their functions. When smooth muscles in the stomach wall contract, for example, they squeeze the food inside the stomach, helping to mix and churn the food and break it into smaller pieces. This is an important part of digestion. Contractions of smooth muscles are involuntary, so they are not under conscious control. Instead, they are controlled by the autonomic nervous system, hormones, neurotransmitters, and other physiological factors.

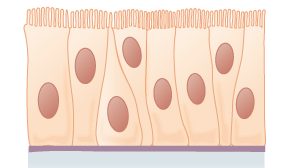

Structure of Smooth Muscle

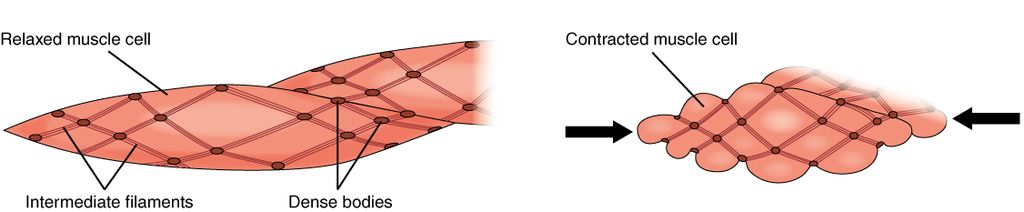

The cells that make up smooth muscle are generally called myocytes. Unlike the muscle fibres of striated muscle tissue, the myocytes of smooth muscle tissue do not have their filaments arranged in sarcomeres. Therefore, smooth tissue is not striated. However, the myocytes of smooth muscle do contain myofibrils, which in turn contain bundles of myosin and actin filaments. The filaments cause contractions when they slide over each other, as shown in Figure 12.3.7.

Functions of Smooth Muscle

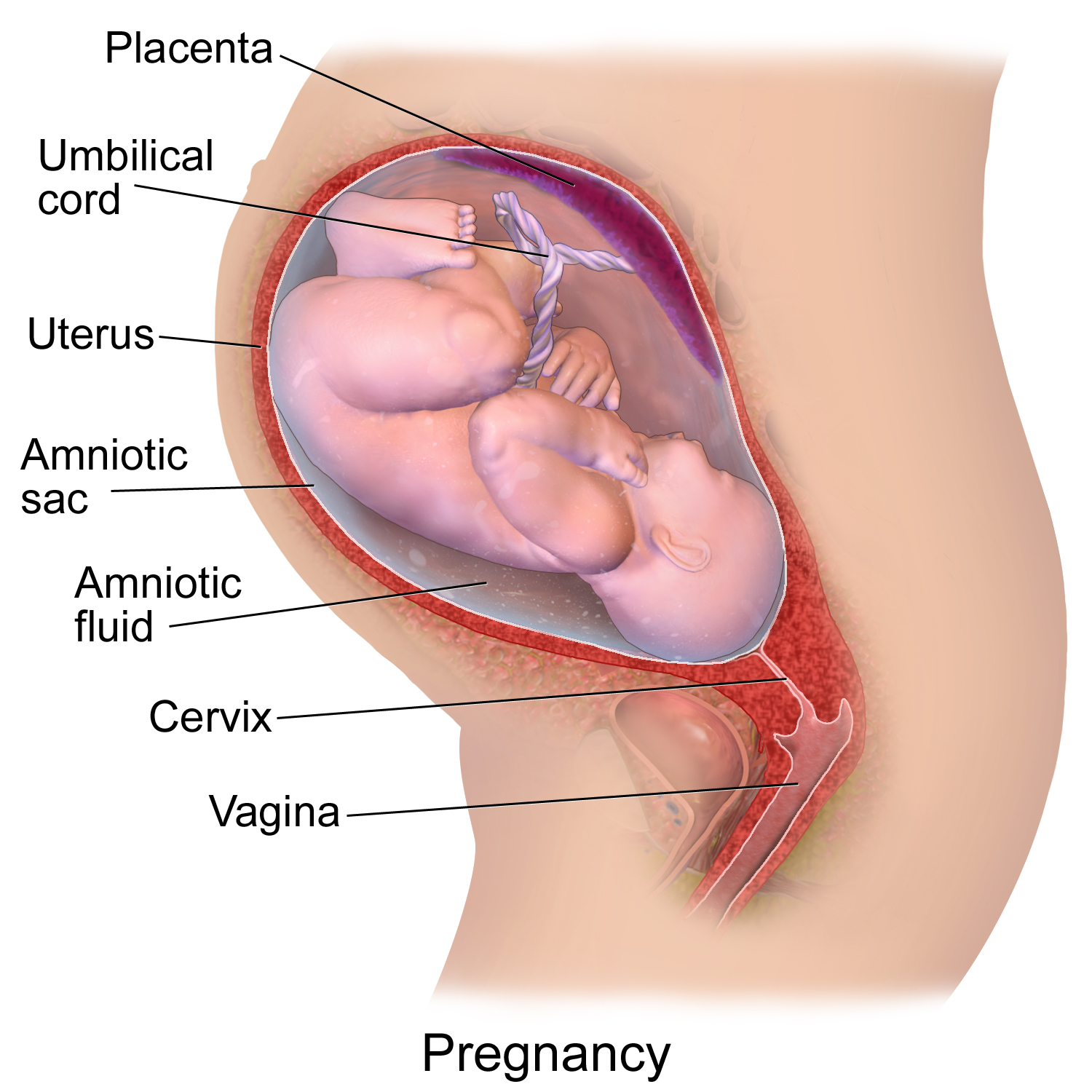

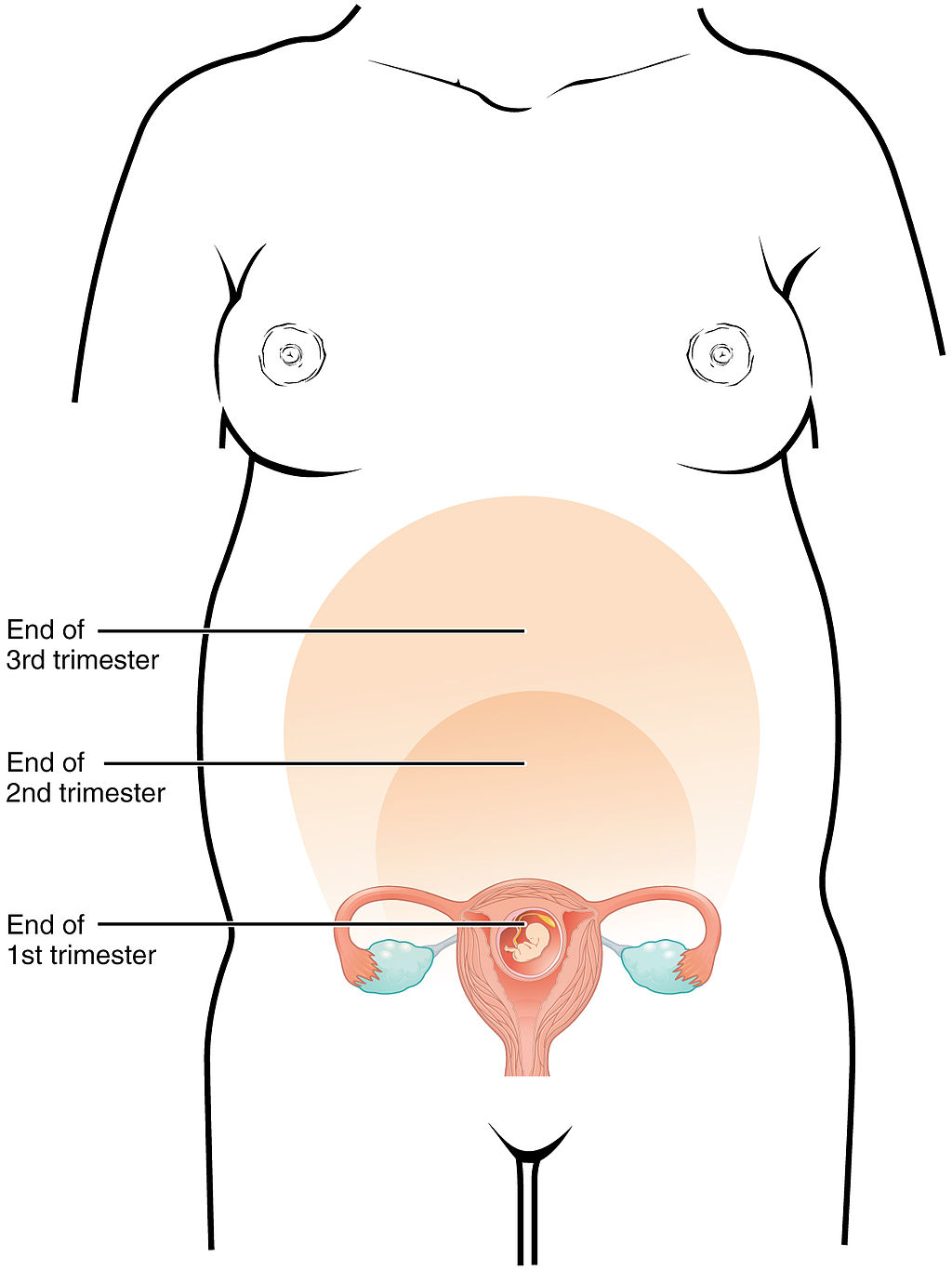

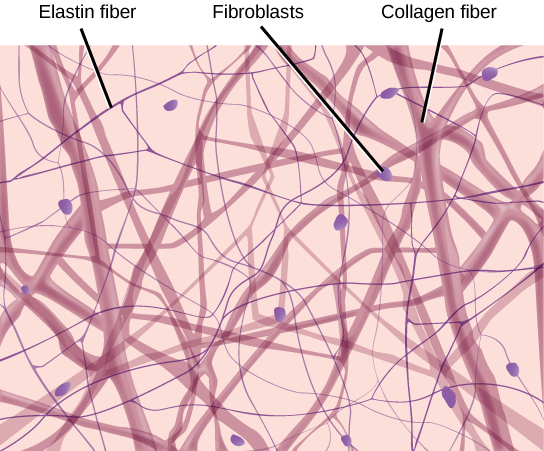

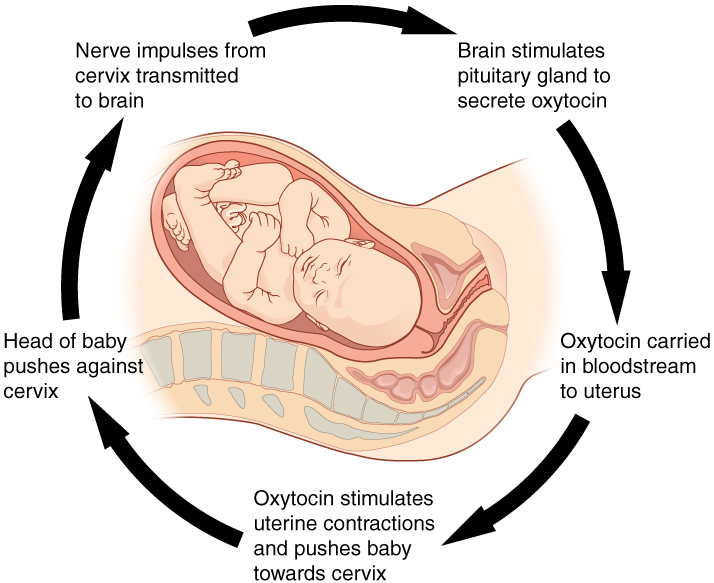

Unlike striated muscle, smooth muscle can sustain very long-term contractions. Smooth muscle can also stretch and still maintain its contractile function, which striated muscle cannot. The elasticity of smooth muscle is enhanced by an extracellular matrix secreted by myocytes. The matrix consists of elastin, collagen, and other stretchy fibres. The ability to stretch and still contract is an important attribute of smooth muscle in organs such as the stomach and uterus (see Figures 12.3.8 and 12.3.9), both of which must stretch considerably as they perform their normal functions.

|

|

The following list indicates where many smooth muscles are found, along with some of their specific functions.

- Walls of organs of the gastrointestinal tract (such as the esophagus, stomach, and intestines), moving food through the tract by peristalsis

- Walls of air passages of the respiratory tract (such as the bronchi), controlling the diameter of the passages and the volume of air that can pass through them

- Walls of organs of the male and female reproductive tracts; in the uterus, for example, pushing a baby out of the uterus and into the birth canal

- Walls of structures of the urinary system, including the urinary bladder, allowing the bladder to expand so it can hold more urine, and then contract as urine is released

- Walls of blood vessels, controlling the diameter of the vessels and thereby affecting blood flow and blood pressure

- Walls of lymphatic vessels, squeezing the fluid called lymph through the vessels

- Iris of the eyes, controlling the size of the pupils and thereby the amount of light entering the eyes

- Arrector pili in the skin, raising hairs in hair follicles in the dermis

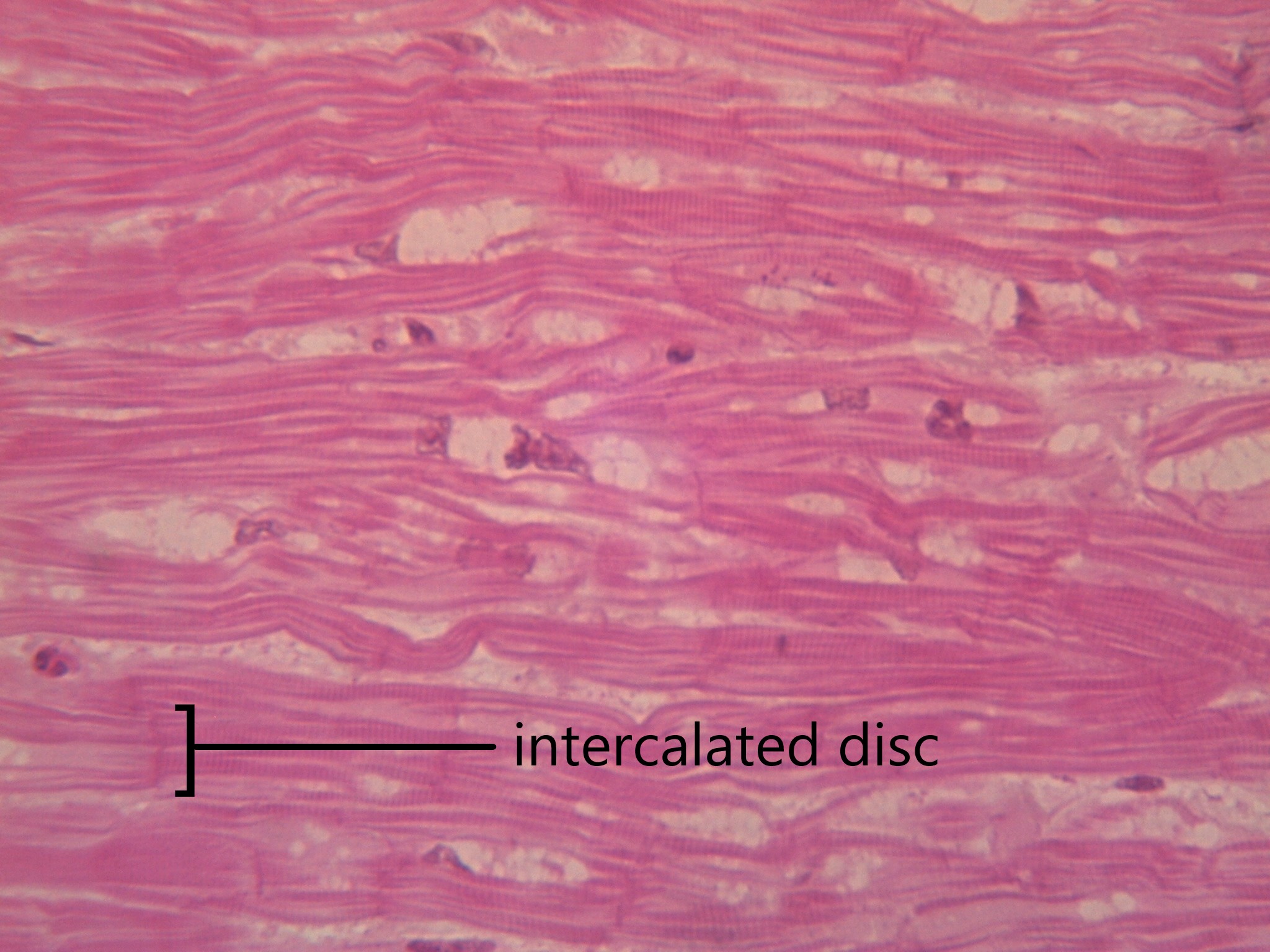

Cardiac Muscle

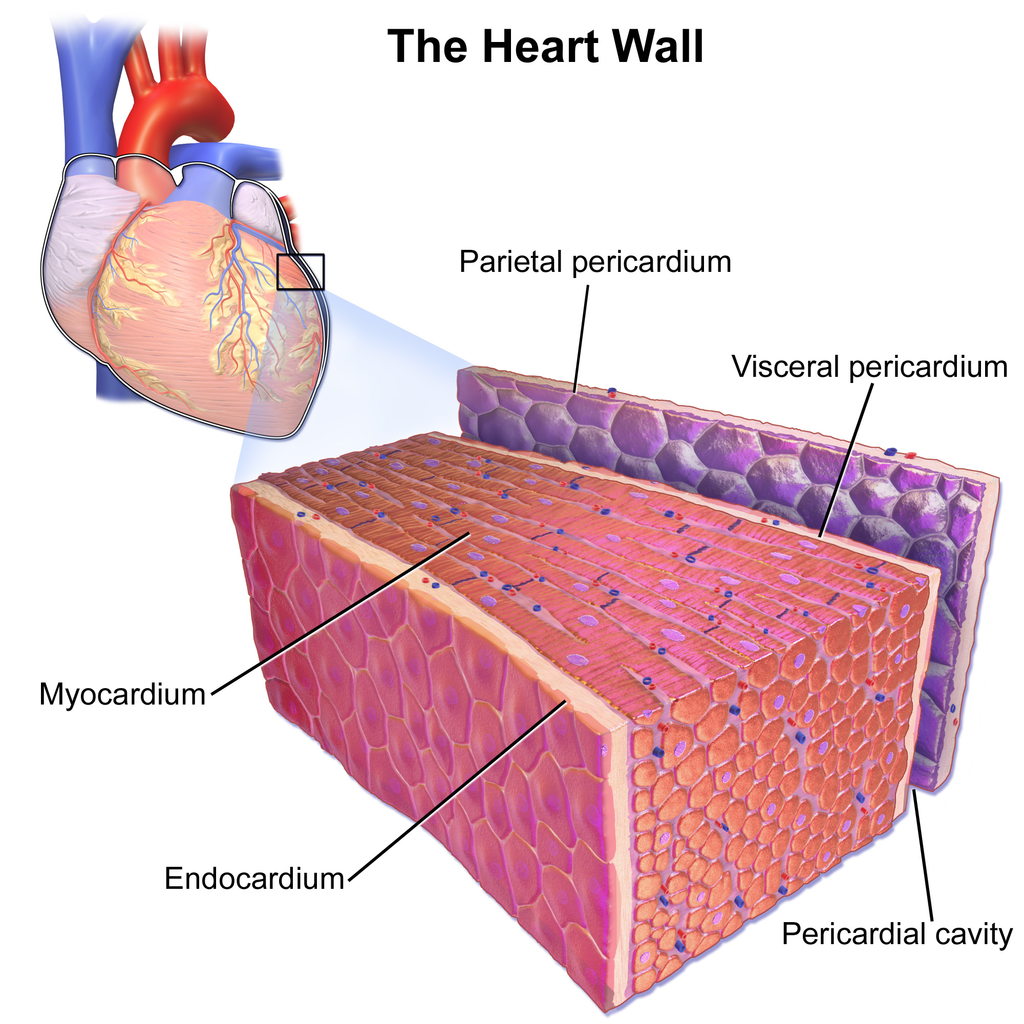

Cardiac muscle is found only in the wall of the heart. It is also called myocardium. As shown in Figure 12.3.10, myocardium is enclosed within connective tissues, including the endocardium on the inside of the heart and pericardium on the outside of the heart. When cardiac muscle contracts, the heart beats and pumps blood. Contractions of cardiac muscle are involuntary, like those of smooth muscles. They are controlled by electrical impulses from specialized cardiac muscle cells in an area of the heart muscle called the sinoatrial node.

Like skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle is striated because its filaments are arranged in sarcomeres inside the muscle fibres. However, in cardiac muscle, the myofibrils are branched at irregular angles rather than arranged in parallel rows (as they are in skeletal muscle). This explains why cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues look different from one another.

The cells of cardiac muscle tissue are arranged in interconnected networks. This arrangement allows rapid transmission of electrical impulses, which stimulate virtually simultaneous contractions of the cells. This enables the cells to coordinate contractions of the heart muscle.

The heart is the muscle that performs the greatest amount of physical work in the course of a lifetime. Although the power output of the heart is much less than the maximum power output of some other muscles in the human body, the heart does its work continuously over an entire lifetime without rest. Cardiac muscle contains a great many mitochondria, which produce ATP for energy and help the heart resist fatigue.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

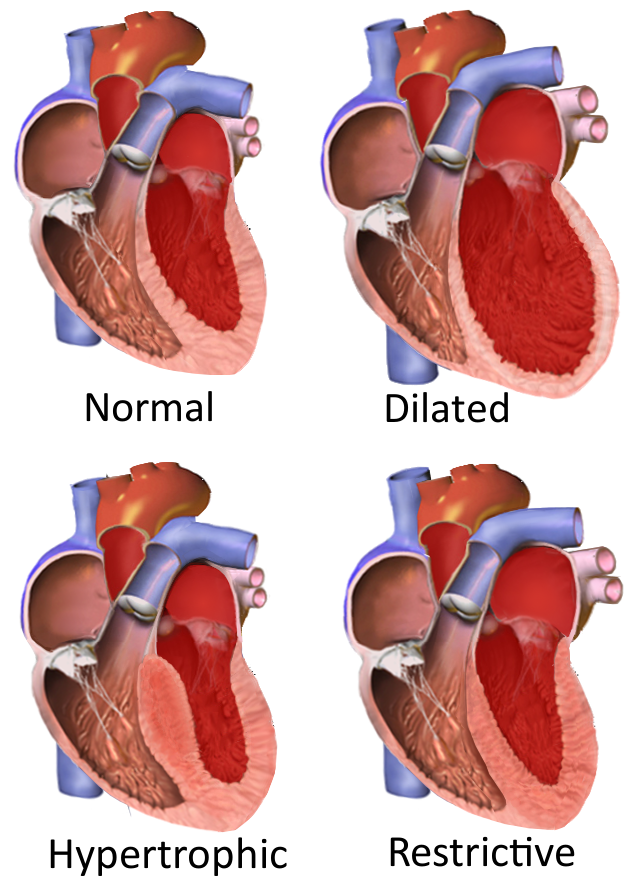

Cardiomyopathy is a disease in which the muscles of the heart are no longer able to effectively pump blood to the body — extreme forms of this disease can lead to heart failure. There are four main types of cardiomyopathy (also illustrated in Figure 12.3.11):

- Dilated (congestive) cardiomyopathy: the left ventricle (the chamber itself) of the heart becomes enlarged and can't pump blood our to the body. This is normally related to coronary artery disease and/or heart attack

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: abnormal thickening of the muscular walls of the left ventricle make the chamber less able to work properly. This condition is more common in patients with a family history of the disease.

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy: the myocardium becomes abnormally rigid and inelastic and is unable to expand in between heartbeats to refill with blood. Restrictive cardiomyopathy typically affects older people.

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: the right ventricular muscle is replaced by adipose or scar tissue, reducing elasticity and interfering with normal heartbeat and rhythm. This disease is often caused by genetic mutations.

Cardiomyopathy is typically diagnosed with a physical exam supplemented by medical and family history, an angiogram, blood tests, chest x-rays and electrocardiograms. In some cases your doctor would also requisition a CT scan and/or genetic testing.

When treating cardiomyopathy, the goal is to reduce symptoms that affect everyday life. Certain medications can help regularize and slow heart rate, decrease chances of blood clots and cause vasodilation in the coronary arteries. If medication is not sufficient to manage symptoms, a pacemaker or even a heart transplant may be the best option. Lifestyle can also help manage the symptoms of cardiomyopathy — people living with this disease are encouraged to avoid drug and alcohol use, control high blood pressure, eat a healthy diet, get ample rest and exercise, as well as reduce stress levels.

12.3 Summary

- Muscle tissue is a soft tissue that makes up most of the tissues in the muscles of the human muscular system. It is the only type of tissue that has cells with the ability to contract.

- Skeletal muscle tissue is attached to bones by tendons. It allows voluntary body movements.

- Skeletal muscle is the most common type of muscle tissue in the human body. To move bones in opposite directions, skeletal muscles often consist of pairs of muscles that work in opposition to one another to move bones in different directions at joints.

- Skeletal muscle fibres are bundled together in units called muscle fascicles, which are bundled together to form individual skeletal muscles. Skeletal muscles also have connective tissue supporting and protecting the muscle tissue.

- Each skeletal muscle fibre consists of a bundle of myofibrils, which are bundles of protein filaments. The filaments are arranged in repeating units called sarcomeres, which are the basic functional units of skeletal muscles. Skeletal muscle tissue is striated because of the pattern of sarcomeres in its fibres.

- Skeletal muscle fibres can be divided into two types, called slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibres. Slow-twitch fibres are used mainly in aerobic endurance activities, such as long-distance running. Fast-twitch fibres are used mainly for non-aerobic, strenuous activities, such as sprinting. Proportions of the two types of fibres vary from muscle to muscle and person to person.

- Smooth muscle tissue is found in the walls of internal organs and vessels. When smooth muscles contract, they help the organs and vessels carry out their functions. Contractions of smooth muscles are involuntary and controlled by the autonomic nervous system, hormones, and other substances.

- Cells of smooth muscle tissue are not striated because they lack sarcomeres, but the cells contract in the same basic way as striated muscle cells. Unlike striated muscle, smooth muscle can sustain very long-term contractions and maintain its contractile function, even when stretched.

- Cardiac muscle tissue is found only in the wall of the heart. When cardiac muscle contracts, the heart beats and pumps blood. Contractions of cardiac muscle are involuntary, like those of smooth muscles. They are controlled by electrical impulses from specialized cardiac cells.

- Like skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle is striated because its filaments are arranged in sarcomeres inside the muscle fibres. However, the myofibrils are branched instead of arranged in parallel rows, making cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues look different from one another.

- The heart is the muscle that performs the greatest amount of physical work in the course of a lifetime. Its cells contain a great many mitochondria to produce ATP for energy and help the heart resist fatigue.

12.3 Review Questions

- What is muscle tissue?

-

-

- Where is skeletal muscle found, and what is its general function?

- Why do many skeletal muscles work in pairs?

- Describe the structure of a skeletal muscle.

- Relate muscle fibre structure to the functional units of muscles.

- Why is skeletal muscle tissue striated?

- Where is smooth muscle found? What controls the contraction of smooth muscle?

- Where is cardiac muscle found? What controls its contractions?

- The heart muscle is smaller and less powerful than some other muscles in the body. Why is the heart the muscle that performs the greatest amount of physical work in the course of a lifetime? How does the heart resist fatigue?

- Give one example of connective tissue that is found in muscles. Describe one of its functions.

12.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_PYnWVoUzM

What happens during a heart attack? - Krishna Sudhir, TED-Ed, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bwOE1MEginA&feature=emb_logo

Three types of muscle | Circulatory system physiology | NCLEX-RN | KhanAcademyMedicine, 2012.

Attributions

Figure 12.3.1

Look by ali-yahya-155huuQwGvA [photo] by Ali Yahya on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 12.3.2

Skeletal_Smooth_Cardiac by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 12.3.3

Anterior_and_Posterior_Views_of_Muscles by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 12.3.4

Antagonistic Muscle Pair by Laura Guerin at CK-12 Foundation on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 12.3.5

Muscle_Fibes_(large) by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 12.3.6

Muscle_Fibers_(small) by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 12.3.7

Smooth_Muscle_Contraction by OpenStax on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 12.3.8

Blausen_0747_Pregnancy by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 12.3.9

Size_of_Uterus_Throughout_Pregnancy-02 by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 12.3.10

1024px-Blausen_0470_HeartWall by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 12.3.11

Tipet_e_kardiomiopative by Npatchett at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. (Work derived from Blausen 0165 Cardiomyopathy Dilated by BruceBlaus)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 4.18 Muscle tissue [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 4.4). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/4-4-muscle-tissue-and-motion

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 28.18 Size of uterus throughout pregnancy [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 28.4). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/28-4-maternal-changes-during-pregnancy-labor-and-birth

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 18). Figure 10.3 The three connective tissue layers [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-2-skeletal-muscle

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 18). Figure 10.4 Muscle fiber [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-2-skeletal-muscle

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 18). Figure 10.24 Muscle contraction [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 10.8). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-8-smooth-muscle

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2016, May 18). Figure 11.5 Overview of the muscular system [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 11.2). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/11-2-naming-skeletal-muscles

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2012). Figure 5 Triceps and biceps muscles in the upper arm are opposing muscles. [digital image]. In CK-12 Biology (Section 21.3) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-biology/section/21.3/ (Last modified August 11, 2017.)

khanacademymedicine. (2012, October 19). Three types of muscle | Circulatory system physiology | NCLEX-RN | Khan Academy. YouTube.

TED-Ed. (2017, February 14). What happens during a heart attack? - Krishna Sudhir. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_PYnWVoUzM&feature=youtu.be

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Figure 6.7.1 Men from Maasai Mara, Kenya.

Built for Heat

These tall, slender men live near the equator in Kenya, East Africa — one of the hottest regions of the world. These and the other people of his tribal group, called the Maasai, are among the tallest, most linear people on the planet. Their body build is thought to be an adaptation to their climate, which is hot year-round.

Climate Extremes

Climate refers to the average weather conditions in a region over a long period of time. One of the main determinants of climate is temperature. Both hot and cold temperatures are serious environmental stresses on the human body.

In the cold, there is risk of hypothermia, which is a dangerous decrease in core body temperature. The normal temperature of the human body is 37 degrees C (98.6 degrees F). Hypothermia sets in when body temperature drops to 34.4 degrees C (94 degrees F). If body temperature falls below 29.4 degrees C (85 degrees F), it starts to cool very rapidly because the body’s temperature regulation mechanism starts to fail.

The opposite problem occurs in the heat, where the risk is hyperthermia, which is a dangerous increase in core body temperature. If human body temperature rises above about 40.6 degrees C (105 degrees F), hyperthermia may become life threatening. If a temperature this high persists more than a few days, it generally damages the brain and other internal organs, leading to death.

Human Adaptation to Heat and Cold

Humans are the most widespread species on the planet, and they have lived in extreme climates for tens of thousands of years. As a result, many human populations have had to cope with extreme temperatures for hundreds of generations, which has forced them to develop genetic adaptations to these climate extremes.

The size and proportions of the human body may play an important role in how well an individual is able to handle hot or cold temperatures. In general, people with a tall, slender build, like the Maasai man pictured in Figure 6.7.1, are well adapted to heat, whereas people with a short, stocky build (like the Indigenous North American Inuit pictured in Figure 6.7.2) are well adapted to cold. These relationships between body build and climate were first noticed in other animal species in the 1800s by biologists Carl Bergmann and Joel Allen. These scientists formulated what are now known as Bergmann’s and Allen’s rules.

Figure 6.7.2 Indigenous North American Inuit.

Bergmann’s Rule

Bergmann's rule states that within a broadly distributed taxonomic group, populations or species of larger size are found in colder environments, whereas populations or species of smaller size are found in warmer environments. Bergmann’s rule has been shown to generally apply to widespread species of mammals and birds, although there are also many exceptions to the rule.

What explains Bergmann’s rule? Larger animals have a lower surface area to volume ratio than smaller animals, which is illustrated in Table 6.7.1 for a simple shape, a cube. From the table, you can see how the surface area to volume ratio of a cube decreases dramatically as the size of the cube increases. Because heat is lost through the surface of the body, an animal with a smaller surface area to volume ratio radiates less body heat per unit of mass. The larger body mass also allows the animal to generate more heat. A larger animal has more cells, so it can produce more body heat as a byproduct of cellular metabolism. Both of these factors allow a larger animal to stay warmer in a cold climate.

Table 6.7.1

Relationship of Surface Area to Volume in Cubes of Different Sizes

| Relationship of Surface Area to Volume in Cubes of Different Sizes | |||

| Side of Cube (cm) | Surface Area of Cube (cm2) | Volume of Cube (cm3) | Surface Area:Volume Ratio |

| 2 | 24 | 8 | 3:1 |

| 4 | 96 | 64 | 3:2 |

| 6 | 216 | 216 | 3:3 |

| 12 | 864 | 1728 | 3:6 |

| 20 | 2400 | 8000 | 3:10 |

Warmer climates impose the opposite problem: body heat generated by metabolism needs to be dissipated quickly rather than stored within the body. Smaller animals have a higher surface area to volume ratio that maximizes heat loss through the surface of the body and helps cool the body. With less mass and fewer cells, smaller animals also generate less heat due to cellular metabolism.

Anthropologists have found that many human populations tend to follow Bergmann’s rule. For example, a study of 100 human populations in the 1950s found a strong negative correlation between mean body mass and average yearly temperature. In other words, higher body mass was generally found in colder places, and lower body mass was generally found in hotter places.

There are also exceptions to the rule, in part because we use cultural responses to temper environmental stresses so we do not need to change genetically or physiologically in order to cope. Humans, for example, use clothing and heated buildings to stay warm in cold climates, which tends to counter the effects of natural selection changing human body shape in cold climates.

Allen’s Rule

Allen’s rule is a corollary of Bergmann’s rule. It states that animals living in hotter climates generally have longer extremities (such as limbs, tails, snouts, and ears) than closely related animals living in colder climates. The explanation for Allen’s rule is similar to the rationale behind Bergmann’s rule. Longer extremities maximize an animal’s surface area, allowing greater heat loss through the surface of the body. Therefore, having long extremities is adaptive in hot climates where the main challenge is dissipating body heat.

Anthropologists have noted that, in populations that have lived in tropical regions for long periods of time, the limbs of people tend to be longer in proportion to overall body height. The Maasai man pictured in Figure 6.7.1 is a clear example. His exceptionally long limbs — like those of other members of his population — are optimally proportioned for the hot climate in Kenya. The shorter-limbed body proportions of the Inuit people (Figure 6.7.2) suit them well for their cold climate. Marked differences in limb length have also been observed in related populations that have lived for long periods of time at different altitudes. High altitudes have colder climates than lower altitudes and — consistent with Allen's rule —people tend to have shorter limbs at higher altitudes.

Other Human Responses to Heat

Humans exhibit several other responses to high temperatures that are generally considered either short-term physiological responses or examples of longer-term acclimatization.

Sweating and Humidity

Because humans are basically tropical animals, we generally have an easier time dealing with excessive heat than excessive cold. Evaporation of sweat is the main way we cool the body. The dancer in Figure 6.7.4 is sweating copiously while working out in a hot environment. Why does sweating cool us? When sweat evaporates from the skin, it requires heat. The heat comes from the surface of the body, resulting in evaporative cooling.

How well we can deal with high air temperatures depends in large part on the humidity of the air. We have a harder time losing excess body heat when the humidity is high because our sweat does not evaporate as well as it does when the humidity is low. Instead, the sweat stays on the skin, making us feel clammy and warmer than we would feel if the humidity were lower. If the air is dry, on the other hand, sweat evaporates readily, and we feel more comfortable. For this reason, we are able to tolerate higher temperatures when the humidity is low. This is the basis of the common aphorism, “It’s not the heat, but the humidity.”

The heat index (HI) is a number that combines air temperature and relative humidity to indicate how hot the air feels due to the humidity. The heat index is also called "apparent temperature.” Figure 6.7.5 shows the heat index at different combinations of air temperature and relative humidity. As you can see, when the humidity is very high, even a 90-degree F (32 degrees C) temperature can be very dangerous.

Acclimatization to Heat

If humidity is low, evaporation of sweat can be an effective way to keep the body from overheating. However, the loss of water and salts in sweat can also be dangerous. In very hot conditions, an adult may lose up to four litres of sweat per hour and up to 14 litres per day. Such water losses may cause severe dehydration if the water is not replaced by drinking much more than usual. The loss of salts may also upset the normal salt balance in the body, which can be dangerous. Becoming acclimatized to heat by gradually increasing the exposure time to high temperatures — particularly while exercising or doing physical work — can reduce the risk of these effects.

It may take up to 14 days to attain maximum heat acclimatization. As the body becomes acclimatized, sweat output increases, and sweating begins sooner. The salt content of the sweat also declines, as does the output of urine. These and other physiological changes help the body lose heat through the evaporation of sweat, while maintaining the proper balance of salts and fluids in the body. There may also be increased blood flow to the body surface through the widening of blood vessels near the skin. This is called vasodilation. This brings more heat from the body core to the skin, and from there it may be radiated out into the environment.

Becoming acclimatized to heat allows one to safely perform more exercise or work in the heat. It also helps prevent heat-related illnesses by reducing strain on the body. Heat-related illnesses — from least to most serious — include heat cramps, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke.

- Heat cramps are muscle spasms caused by loss of water and salts. They often follow prolonged sweating brought on by over-exertion in hot weather.

- Heat exhaustion is a condition in which over-heating of the body causes dizziness, headache, profuse sweating, rapid heartbeat. and other symptoms. Without prompt treatment, heat exhaustion can lead to heat stroke.

- Heat stroke is potentially life threatening and a medical emergency. Heat stroke results from prolonged exposure to high temperatures, usually in combination with dehydration. It leads to failure of the body's temperature control system and is diagnosed when the core body temperature exceeds 105 degrees F (40 degrees C). Symptoms may include nausea, seizures, confusion, disorientation, and coma.

Acclimatization to heat, like other types of acclimatization, is a reversible process. Just as quickly as heat acclimatization occurs, the physiological changes fade away in the absence of heat exposure. The body returns to its baseline state within a week or two of no longer exercising or working at high temperatures.

Other Human Responses to Cold

Besides genetic difference in body build, there are two major ways the human body can respond to the cold. One way is by producing more body heat, and the other way is by conserving more body heat. An immediate response to cooling of the body is shivering. This is an involuntary and simultaneous contraction of many tiny muscles in the body. These muscle contractions generate a small amount of heat. Another early response to cold temperature is a narrowing of blood vessels near the skin. This is called vasoconstriction. This helps to shunt blood away from the body surface so more heat is held at the body core. The skin cools down and radiates less heat into the environment.

Hunting Response

At temperatures below freezing, vasoconstriction can be dangerous if it lasts too long. The extremities become too cold because of lack of blood flow, and cold injury (such as frostbite) may occur. Frostbite is tissue destruction that occurs when tissue freezes. You can see a mild-to-moderate case of frostbite of the fingers in Figure 6.7.7. If frostbite is severe, it may lead to gangrene and amputation of the affected extremities.

The body counters the possibility of cold injury with a reaction called the hunting response. This is a process of alternating vasoconstriction and vasodilation in extremities exposed to cold. About five to ten minutes after the start of cold exposure, the blood vessels in the extremities suddenly dilate, which increases blood flow and subsequently the temperature of the extremities. This is soon followed by another phase of vasoconstriction, and then the process repeats.

The hunting response occurs in most people, but several factors may influence the strength of the response. People who live or work regularly in cold environments show an increased hunting response. Through acclimatization, however, tropical residents can develop an increased response, which is indistinguishable from that of arctic residents. Genetic factors may play a role in the hunting response, but this is uncertain because it is difficult to differentiate between adaptation and acclimatization.

Persistent Vasoconstriction

Where temperatures rarely fall below freezing but are repeatedly very chilly, the hunting response may not occur. Instead, vasoconstriction may persist to keep heat within the body at the expense of cooling the skin. As long as the temperature stays above freezing, cold injury (such as frostbite) will not occur. This type of response has been shown to occur in indigenous desert dwellers in southern Africa and Australia, where the temperature is hot during the day and very cold at night. People in these populations also tend to deposit fat around the organs in their chest and abdomen. The fat serves as insulation, protecting vital structures from the cold.

High-Fat Diet

Besides shivering, another way to increase body heat is to raise the basal metabolic rate. The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the amount of energy that a person needs to keep the body functioning at rest. The higher the BMR, the more heat the body generates, even without exercise or physical labor. The BMR can be increased by consuming large quantities of high-calorie fatty foods. People living in very cold subarctic regions, including the Inuit, traditionally ate whale and seal blubber and other high-fat foods, which helped them maintain a high BMR and stay warm.

Figure 6.7.8 Whale and seal blubber (mainly on abundant ring seals) is an important part of the traditional Inuit diet.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

Too many news stories report young children being seriously injured or dying from heat stroke in hot vehicles. On average, 38 children die in hot vehicles each year from heat-related deaths after being trapped inside. Most often, this happens by accident, when a parent or caregiver unknowingly leaves a sleeping child in a car. In other cases, children get into cars on their own, and then cannot get out again.

A child’s thermoregulatory system is not as efficient as that of an adult, and a child’s body temperature may increase as much as five times faster. This makes children prime candidates for heat stroke. A motor vehicle is also easily heated by direct sun. The windows of the vehicle allow solar radiation to pass through and heat up objects inside. A dark-coloured dashboard or seat may quickly reach a temperature of more than 180 degrees F (82 degrees C)! These hot surfaces can just as quickly heat the adjacent air, rapidly increasing the temperature of the air trapped inside the vehicle.

Here are several simple tips that parents and caregivers can follow to prevent heat stroke tragedies:

- Never leave children alone in or around cars — not even for a minute.

- Always open the back door and check the back seat before leaving your vehicle to be sure no child has been left behind.

- Put something you will need, such as your cell phone or handbag, in the back seat so you will have to open the back door to retrieve it whenever you park the car.

- Keep a large stuffed animal in the child's car seat, and when the child is placed in the car seat, put the stuffed animal in the front passenger seat as a visual reminder that the child is in the back.

- Make sure you have a strict policy in place with everyone involved in the care of your child that you should always be called whenever your child does not show up at daycare or school as scheduled.

- Keep vehicles locked at all times, even in driveways and garages. Ask home visitors, child care providers, and neighbors to do the same.

- Keep car keys and remote vehicle openers out of reach of children.

- If a child is missing, immediately check the inside passenger compartments and trunks of all vehicles in the area. Check vehicles even if they are locked, because a child may lock a vehicle after entering and not be able to unlock it again to get out.

- If you see a child alone in a vehicle, call 911 immediately. If the child seems hot or sick, get them out of the vehicle as quickly as possible.

- Pay for gas at the pump and use drive-throughs at the bank, pharmacy, or wherever else they are available.

6.7 Summary

- Both hot and cold temperatures are serious environmental stresses on the human body. In the cold, there is risk of hypothermia, which is a dangerous decrease in core body temperature. In the heat, there is risk of hyperthermia, which is a dangerous increase in core body temperature.

- According to Bergmann’s rule, body size tends to be negatively correlated with temperature, because larger body size increases heat production and decreases heat loss. The opposite holds true for small body size. Bergmann’s rule applies to many human populations that are hot- or cold-adapted.

- According to Allen’s rule, the length of body extremities is positively correlated with temperature, because longer extremities are better at dissipating excess body heat. The opposite applies to shorter extremities. Allen’s rule applies to relative limb lengths in many human populations that have adapted to heat or cold.

- Sweating is the primary way that humans lose body heat. The evaporation of sweat from the skin cools the body. This only works well when the relative humidity is fairly low. At high relative humidity, sweat does not readily evaporate to cool us down. The heat index (HI) indicates how hot it feels due to the humidity.

- Gradually working longer and harder in the heat can bring about heat acclimatization, in which the body has improved responses to heat stress. For example, sweating starts earlier, sweat contains less salt, and vasodilation brings heat to the surface to help cool the body. Full acclimatization takes up to 14 days and reverses just as quickly when the heat stress is removed.

- The human body can respond to cold by producing more heat (by shivering or increasing the basal metabolic rate) or by conserving heat (by vasoconstriction at the body surface or a layer of fat-insulating internal organs).

- At temperatures below freezing, the hunting response occurs to prevent cold injury, such as frostbite. This is a process of alternating vasoconstriction and vasodilation in extremities that are exposed to dangerous cold. Where temperatures are repeatedly cold but rarely below freezing, the hunting response may not occur, and the skin may remain cold due to vasoconstriction alone.

6.7 Review Questions

- Compare and contrast hypothermia and hyperthermia.

- State Bergmann’s and Allen’s rules.

- How do the Maasai and Inuit match the predictions based on Bergmann’s and Allen’s rules?

- Explain how sweating cools the body.

- What is the heat index?

- Relate the heat index to evaporative cooling of the body.

- Identify three heat-related illnesses, from least to most serious.

- How does heat acclimatization occur?

- State two major ways the human body can respond to the cold, and give an example of each.

- Explain how and why the hunting response occurs.

- Define basal metabolic rate.

- How does a high-fat diet help prevent hypothermia?

- Explain why frostbite most commonly occurs in the extremities, such as the fingers and toes.

6.7 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpHM4DfPZQU

What happens when you get heat stroke? - Douglas J. Casa, TED-Ed, 2014.

https://youtu.be/_Ifq73REJiM

Hailstones' Inupiaq Traditions | Life Below Zero, National Geographic, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1L7EI0vKVuU

How An Igloo Keeps You Warm, It's Okay To Be Smart, 2017.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fctH_1NuqCQ&t=

Why do we sweat? - John Murnan, TED-Ed, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=44&v=j3sY67aGFXY&feature=emb_logo

Wim Hof Method, Wim Hof, 2011.

Attributions

Figure 6.7.1

- Maasai warrior by Ninaras on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en) license.

- Smiling man from Maasai Mara, Kenya by Sneha on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 6.7.2

- Inuit-Kleidung women by Ansgar Walk on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.lv) license.

- Kulusuk, Tunumiit Inuit couple by Arian Zwegers on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

-

Inuit girls by Susan van Gelder on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 6.7.3

Bergmann’s_rule_-_Canis_lupus by Dhaval Vargiya at Yellowstone National Park on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.7.4

Sweating [photo] by Avi Richards on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 6.7.5

Heat_Index by U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.7.6

Thirsty [photo] by Dylan Alcock on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 6.7.7

Frostbitten_hands by Winky from Oxford, UK on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 6.7.8

- Ringed seal preparation by Ansgar Walk on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5/deed.en) license.

- Butchering a narwhal by Spencer & Carole on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

- Inuit children playing while the family is on seal hunt, by GRID-Arendal on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

References

It's Okay To Be Smart. (2017, January 9). How an igloo keeps you warm. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1L7EI0vKVuU&feature=youtu.be

National Geographic. (2014, April 7). Hailstones' Inupiaq traditions | Life below zero. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Ifq73REJiM&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2014, July 21). What happens when you get heat stroke? - Douglas J. Casa. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PpHM4DfPZQU&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, May 15). Why do we sweat? - John Murnan. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fctH_1NuqCQ&feature=youtu.be

Wim Hof. (2011, June 19). Wim Hof Method. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j3sY67aGFXY&feature=youtu.be

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Got Lactase?

Do you remember the American “got milk?” slogan from the 1990s? It was used in advertisements for milk in which celebrities were pictured wearing milk “mustaches.” While the purpose of the “got milk?” ads was to sell more milk, there is no denying that drinking milk can actually be good for one’s health. Milk is naturally high in protein and minerals. It can also be low in fat or even fat-free if treated to remove the lipids that naturally occur in milk. However, before you reach for a tall, cold glass of milk, you might want to ask yourself another question: “got lactase?”

Adaptation to Lactose

Do you drink milk? Or do you avoid drinking milk and consuming milk products because they cause you discomfort? If the latter is the case, then you may have trouble digesting milk.

Milk, Lactose, and Lactase

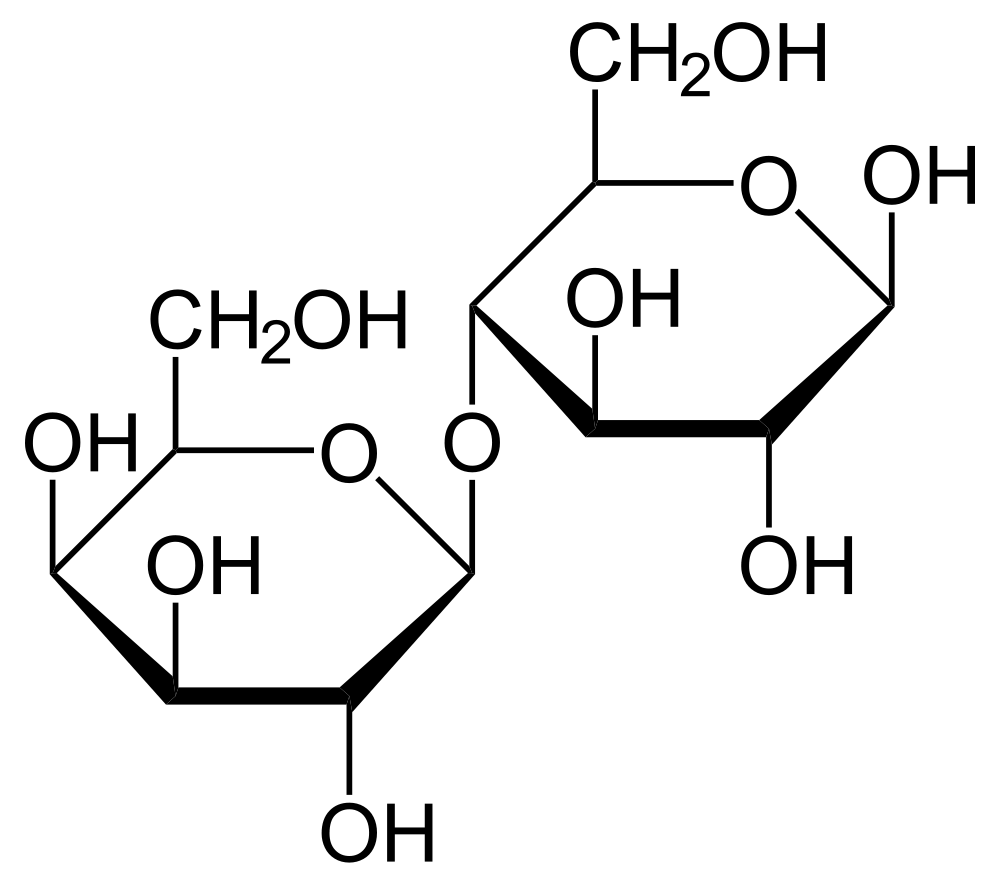

Milk naturally contains more than just proteins and lipids — it also contains carbohydrates. Specifically, milk contains the sugar lactose, which is a disaccharide (two-sugar) compound that consists of one molecule each of galactose and glucose, as shown in the structural formula below (Figure 6.8.2). Lactose makes up between two and eight per cent of milk by weight. The exact amount varies both within and between species.

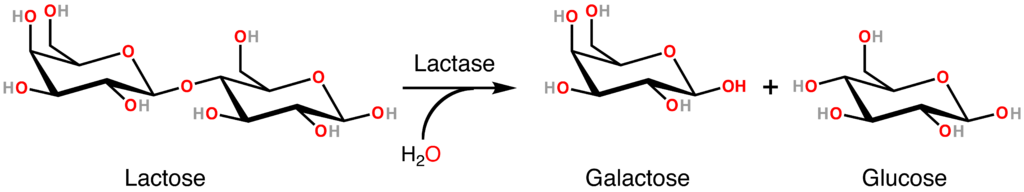

Lactose in milk must be broken down into its two component sugars to be absorbed by the small intestine. The enzyme lactase is needed for this process, as shown in Figure 6.8.3. Human infants are almost always born with the ability to synthesize lactase. This allows them to readily digest the lactose in their mother’s milk (or infant formula). In the majority of children, however, lactase synthesis begins to decline at about two years of age, and less and less lactase is produced throughout childhood.

Lactose Intolerance