12.1 Case Study: Muscles and Movement

Case Study: Needing to Relax

This dog (Figure 12.1.1) is expressing his interest in something — perhaps a piece of food — by using the neck muscles to tilt its head in an adorable fashion. Humans also sometimes tilt their heads to express interest. But imagine how disturbing and painful it would be if your neck tilted involuntarily, without you being able to control it! Forty-three year old Edward unfortunately knows just how debilitating this can be.

Edward has a rare condition called cervical dystonia, which is also called spasmodic torticollis. In this condition, the muscles in the neck contract involuntarily, often causing the person’s head to twist to one side. Figure 12.1.2 shows one type of abnormal head positioning that can be caused by cervical dystonia. The muscles may contract in a sustained fashion, holding the head and neck in one position, or they may spasm repeatedly, causing jerky movements of the head and neck.

Cervical dystonia is painful and can significantly interfere with a person’s ability to carry out their usual daily activities. In Edward’s case, he can no longer drive a car, because his uncontrollable head and neck movements and abnormal head positioning prevent him from navigating the road safely. He also has severe neck and shoulder pain much of the time.

Although it can be caused by an injury, there is no known cause of cervical dystonia — and there is also no cure. Fortunately for Edward, and others who suffer from cervical dystonia, there is a treatment that can significantly reduce symptoms in many people. You may be surprised to learn that this treatment is the same substance which, when injected into the face, is used for cosmetic purposes to reduce wrinkles!

The substance is botulinum toxin, one preparation of which may be familiar to you by its brand name — Botox. It is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, and can cause a life-threatening illness called botulism. However, when injected in very small amounts by a skilled medical professional, botulinum toxins have some safe and effective uses. In addition to cervical dystonia, botulinum toxins can be used to treat other disorders involving the muscular system, such as strabismus (misalignment of the eyes); eye twitches; excessive muscle contraction due to neurological conditions like cerebral palsy; and even overactive bladder.

Botulinum toxin has its effect on the muscular system by inhibiting muscle contractions. When used to treat wrinkles, it relaxes the muscles of the face, lessening the appearance of wrinkles. When used to treat cervical dystonia and other disorders involving excessive muscle contraction, it reduces the abnormal contractions.

In this chapter, you will learn about the muscles of the body, how they contract to produce movements and carry out their functions, and some disorders that affect the muscular system. At the end of the chapter, you will find out if botulinum toxin helped relieve Edward’s cervical dystonia, and how this toxin works to inhibit muscle contraction.

Chapter Overview: Muscular System

In this chapter, you will learn about the muscular system, which carries out both voluntary body movements and involuntary contractions of internal organs and structures. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The different types of muscle tissue — skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle — and their different characteristics and functions.

- How muscle cells are specialized to contract and cause voluntary and involuntary movements.

- The ways in which muscle contraction is controlled.

- How skeletal muscles can grow or shrink, causing changes in strength.

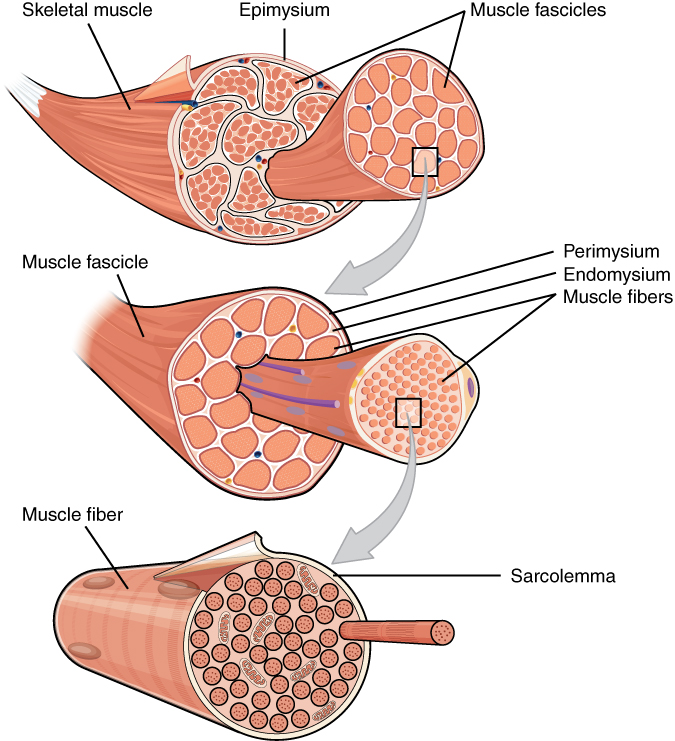

- The structure and organization of skeletal muscles, including the different types of muscle fibres, and how actin and myosin filaments move across each other — according to the sliding filament theory — to cause muscle contraction.

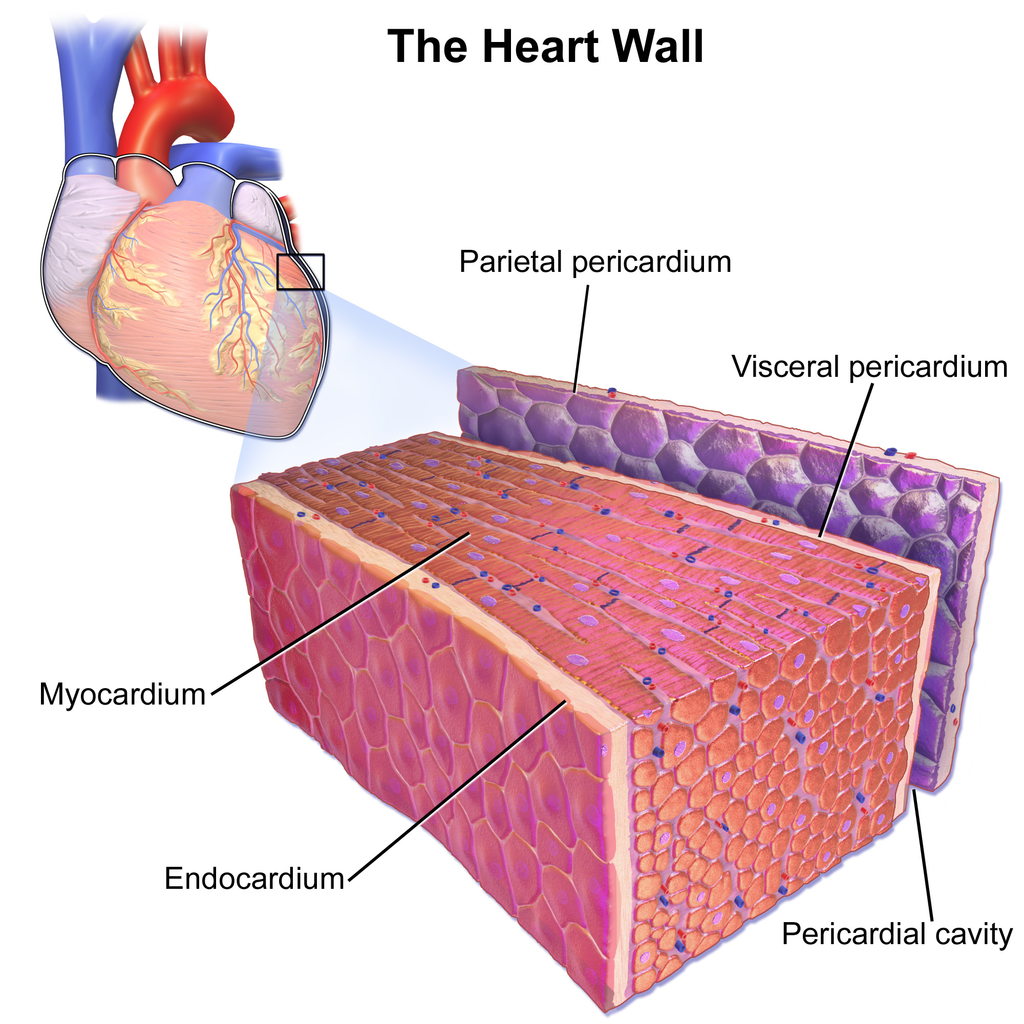

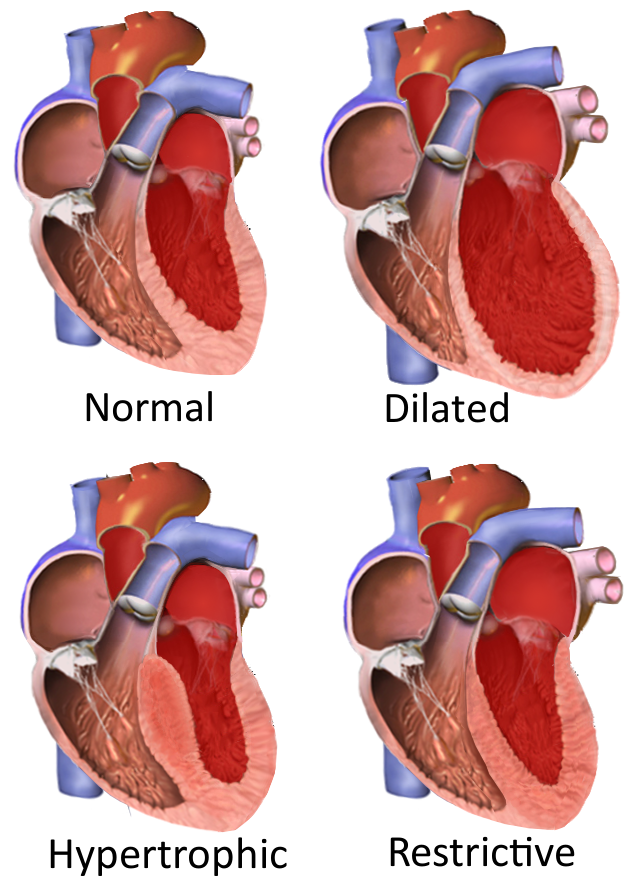

- Cardiac muscle tissue in the heart that contracts to pump blood through the body.

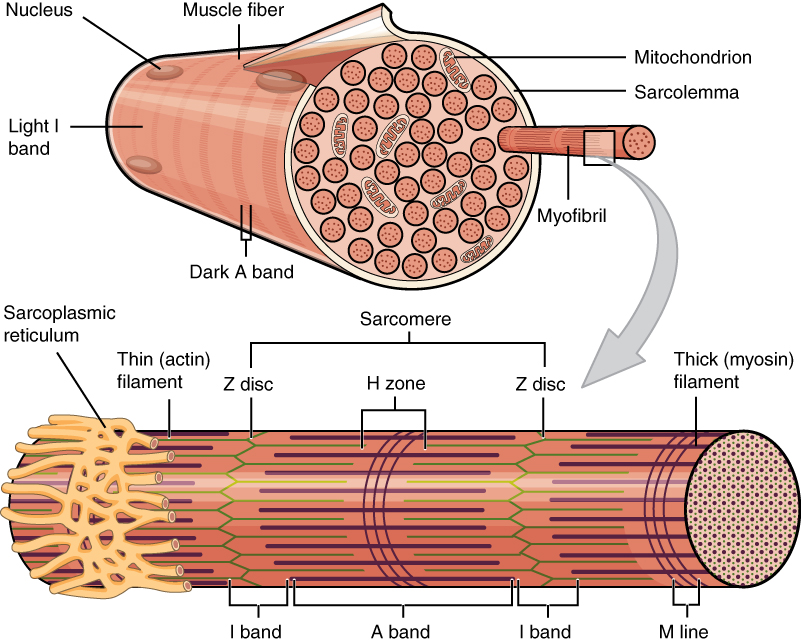

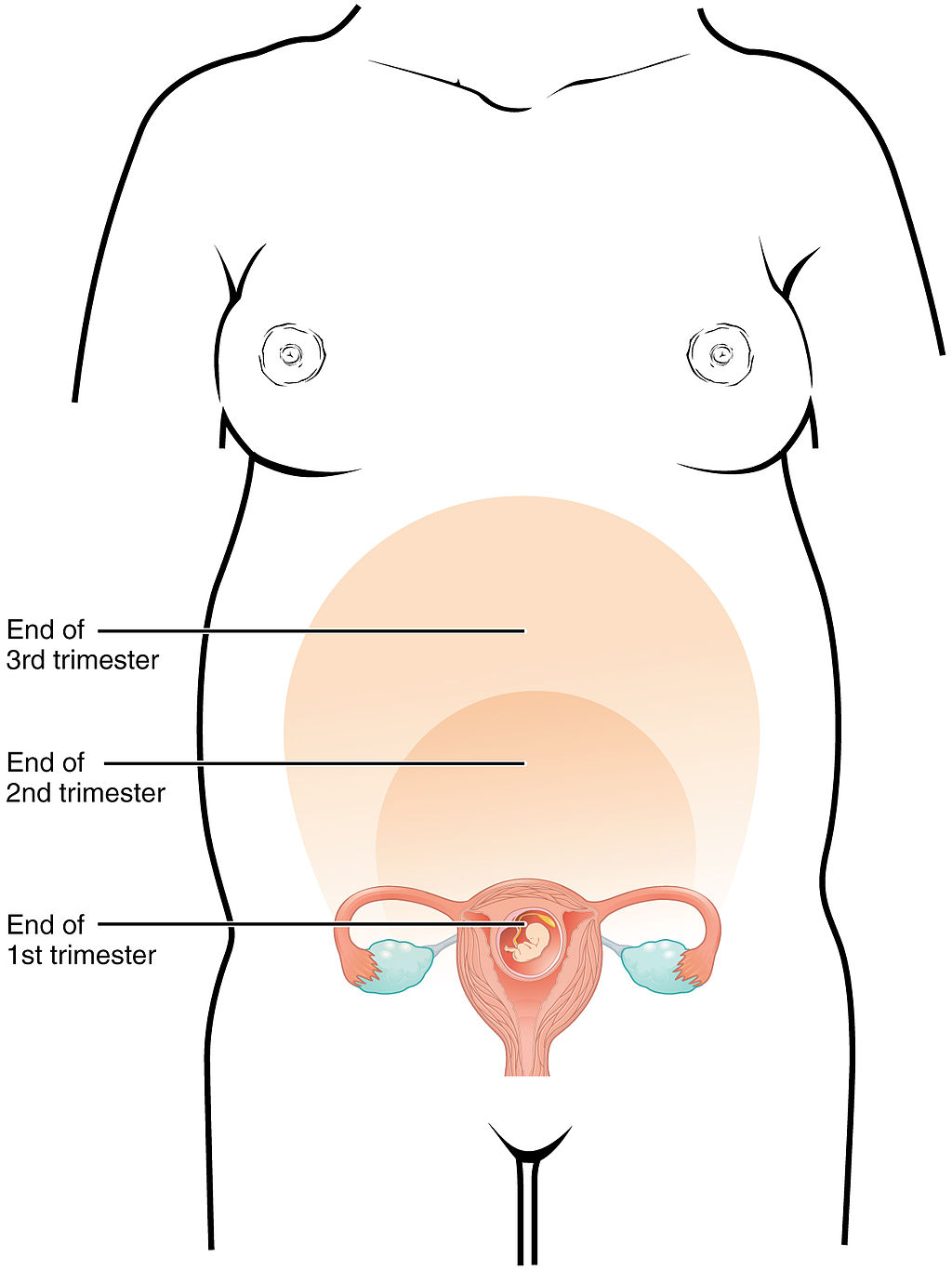

- Smooth muscle tissue that makes up internal organs and structures, such as the digestive system, blood vessels, and uterus.

- The physical and mental health benefits of aerobic and anaerobic exercise, such as running and weight lifting.

- How individuals vary in their response to exercise.

- Disorders of the muscular system, including musculoskeletal disorders (such as strains and carpal tunnel syndrome) and neuromuscular disorders (such as muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, and Parkinson’s disease).

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- How is the contraction of skeletal muscles controlled?

- Botulinum toxin works on the cellular and molecular level to inhibit muscle contraction. Based on what you learn about how muscle contraction works, can you think of some ways it could potentially be inhibited?

- What is one disorder involving a lack of sufficient muscle contraction? Why does it occur?

Attributions

Figure 12.1.1

Whiskey’s 2nd Birthday by Kelly Hunter on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 12.1.2

1024px-Dystonia2010 by James Heilman, MD on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

References

Botulism [online article]. (2018, January 10). World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/botulism

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.) Cervical dystonia [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cervical-dystonia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354123

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study Conclusion: Cancer in the Family

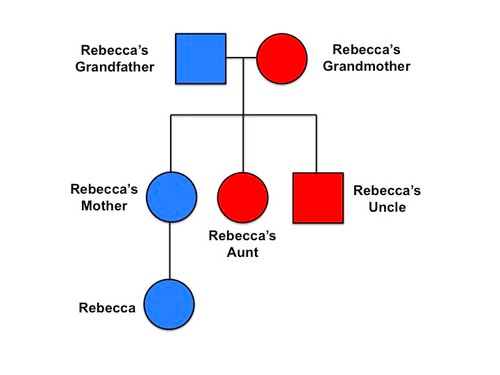

Rebecca’s family tree, as illustrated in the pedigree above (Figure 5.18.1), shows a high incidence of cancer among close relatives. But are genes the cause of cancer in this family? Only genetic testing, which is the sequencing of specific genes in an individual, can reveal whether a cancer-causing gene is being inherited in this family.

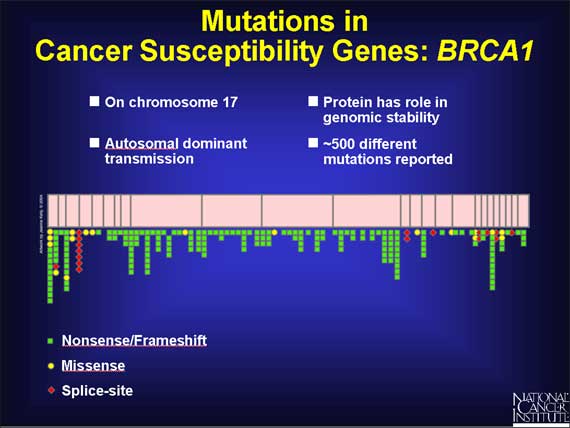

Fortunately for Rebecca, the results of her genetic testing show that she does not have the mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that most commonly increase a person’s risk of getting cancer. This doesn't mean, however, that she doesn’t have other mutations in these genes that could increase her risk of getting cancer. There are many other mutations in BRCA genes whose effect on cancer risk is still not known — and there may be many more yet to be discovered. Figure 5.18.2 from the National Cancer Institute illustrates many of the different types of known mutations in the BRCA1 gene. It is important to continue to study the variations in genes such as BRCA in different people to better assess their possible contribution to the development of disease. As you now know from this chapter, many mutations are harmless, while others can cause significant health effects, depending on the specific mutation and the gene involved.

Mutations in BRCA genes are particularly likely to cause cancer because these genes encode for tumor-suppressor proteins that normally repair damaged DNA and control cell division. If these genes are mutated in a way that causes the proteins to not function properly, other mutations can accumulate and cell division can run out of control, which can cause cancer.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are on chromosomes 17 and 13, respectively, which are autosomes. As Rebecca’s genetic counselor mentioned, mutations in these genes have a dominant inheritance pattern. Now that you know the pattern of inheritance of autosomal dominant genes, if Rebecca’s grandmother did have one copy of a mutated BRCA gene, what are the chances that Rebecca’s mother also has this mutation? Because it is dominant, only one copy of the gene is needed to increase the risk of cancer, and because it is on autosomes instead of sex chromosomes, the sex of the parent or offspring does not matter in the inheritance pattern. In this situation, Rebecca’s grandmother’s eggs would have had a 50 per cent chance of having a BRCA gene mutation (Mendel’s law of segregation). Therefore, Rebecca’s mother would have had a 50 per cent chance of inheriting this gene. Even though Rebecca does not have the most common BRCA mutations that increase the risk of cancer, it does not mean that her mother does not, because there would also only be a 50 per cent chance that she would pass it on to Rebecca. Rebecca’s mother, therefore, should consider getting tested for mutations in the BRCA genes, as well. Ideally, the individuals with cancer in a family should be tested first when a genetic cause is suspected, so that if there is a specific mutation being inherited, it can be identified, and the other family members can be tested for that same mutation.

Mutations in both BRCA1 and BRCA2 are often found in Ashkenazi Jewish families. However, these genes are not linked in the chromosomal sense, because they are on different chromosomes and are therefore inherited independently, in accordance with Mendel’s law of independent assortment. Why would certain gene mutations be prevalent in particular ethnic groups? If people within an ethnic group tend to produce offspring with each other, their genes will remain prevalent within the group. These may be genes for harmless variations such as skin, hair, or eye colour, or harmful variations such as the mutations in the BRCA genes. Other genetically based diseases and disorders are sometimes more commonly found in particular ethnic groups, such as cystic fibrosis in people of European descent, and sickle cell anemia in people of African descent. You will learn more about the prevalence of certain genes and traits in particular ethnic groups and populations in the chapter on Human Variation.

As you learned in this chapter, genetics is not the sole determinant of phenotype. The environment can also influence many traits, including adult height and skin colour. The environment plays a major role in the development of cancer, too. Ninety to 95 per cent of all cancers do not have an identified genetic cause, and are often caused by mutagens in the environment, such as UV radiation from the sun or toxic chemicals in cigarette smoke. But for families like Rebecca’s, knowing their family health history and genetic makeup may help them better prevent or treat diseases that are caused by their genetic inheritance. If a person knows they have a gene that can increase their risk of cancer, they can make lifestyle changes and have early and more frequent cancer screenings. They may even choose to have preventative surgeries that can help reduce their risk of getting cancer and increase their odds of long-term survival if cancer does occur. The next time you go to the doctor and they ask whether any members of your family have had cancer, you will have a deeper understanding why this information is so important to your health.

Chapter 5 Summary

In this chapter you learned about genetics — the science of heredity. Specifically you learned that:

- Chromosomes are structures made of DNA and proteins that are encoded with genetic instructions for making RNA and proteins. The instructions are organized into units called genes, which are segments of DNA that code for particular pieces of RNA. The RNA molecules can then act as a blueprint for proteins, or directly help regulate various cellular processes.

- Humans normally have 23 pairs of chromosomes. Of these, 22 pairs are autosomes, which contain genes for characteristics unrelated to sex. The other pair consists of sex chromosomes (XX in females, XY in males). Only the Y chromosome contains genes that determine sex.

- Humans have an estimated 20 thousand to 22 thousand genes. The majority of human genes have two or more possible versions, called alleles.

- Genes that are located on the same chromosome are called linked genes. Linkage explains why certain characteristics are frequently inherited together.

- Determining that DNA is the genetic material was an important milestone in biology.

-

- In the 1920s, Griffith showed that something in virulent bacteria could be transferred to nonvirulent bacteria, making them virulent, as well.

- In the 1940s, Avery and colleagues showed that the "something" Griffith found was DNA and not protein. This result was confirmed by Hershey and Chase, who demonstrated that viruses insert DNA into bacterial cells.

- In the 1950s, Chargaff showed that in DNA, the concentration of adenine is always the same as the concentration of thymine, and the concentration of guanine is always the same as the concentration of cytosine. These observations came to be known as Chargaff's rules.

- In the 1950s, James Watson and Francis Crick, building on the prior X-ray research of Rosalind Franklin and others, discovered the double helix structure of the DNA molecule.

- Knowledge of DNA's structure helped scientists understand how DNA replicates, which must occur before cell division. DNA replication is semi-conservative because each daughter molecule contains one strand from the parent molecule and one new strand that is complementary to it.

- The central dogma of molecular biology can be summed up as: DNA → RNA → Protein. This means that the genetic instructions encoded in DNA are transcribed to RNA. From RNA, they are translated into a protein.

- RNA is a nucleic acid. Unlike DNA, RNA consists of just one polynucleotide chain instead of two, contains the base uracil instead of thymine, and contains the sugar ribose instead of deoxyribose.

- The main function of RNA is to help make proteins. There are three main types of RNA: messenger RNA (mRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and transfer RNA (tRNA).

- According to the RNA world hypothesis, RNA was the first type of biochemical molecule to evolve, predating both DNA and proteins.

- The genetic code was cracked in the 1960s by Marshall Nirenberg. It consists of the sequence of nitrogen bases in a polynucleotide chain of DNA or RNA. The four bases make up the "letters" of the code. The letters are combined in groups of three to form code "words," or codons, each of which encodes for one amino acid or a start or stop signal.

-

- AUG is the start codon, and it establishes the reading frame of the code. After the start codon, the next three bases are read as the second codon, and so on until a stop codon is reached.

- The genetic code is universal, unambiguous, and redundant.

- Protein synthesis is the process in which cells make proteins. It occurs in two stages: transcription and translation.

-

- Transcription is the transfer of genetic instructions in DNA to mRNA in the nucleus. It includes the steps of initiation, elongation, and termination. After the mRNA is processed, it carries the instructions to a ribosome in the cytoplasm.

- Translation occurs at the ribosome, which consists of rRNA and proteins. In translation, the instructions in mRNA are read, and tRNA brings the correct sequence of amino acids to the ribosome. Then rRNA helps bonds form between the amino acids, producing a polypeptide chain.

- After a polypeptide chain is synthesized, it may undergo additional processing to form the finished protein.

- Mutations are random changes in the sequence of bases in DNA or RNA. They are the ultimate source of all new genetic variation in any species.

-

- Mutations may happen spontaneously during DNA replication or transcription. Other mutations are caused by environmental factors called mutagens.

- Germline mutations occur in gametes and may be passed on to offspring. Somatic mutations occur in cells other than gametes and cannot be passed on to offspring.

- Chromosomal alterations are mutations that change chromosome structure and usually affect the organism in multiple ways. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1 is an example of a chromosomal alteration.

- Point mutations are changes in a single nucleotide. The effects of point mutations depend on how they change the genetic code, and may range from no effects to very serious effects.

- Frameshift mutations change the reading frame of the genetic code and are likely to have a drastic effect on the encoded protein.

- Many mutations are neutral and have no effects on the organism in which they occur. Some mutations are beneficial and improve fitness, while others are harmful and decrease fitness.

- Using a gene to make a protein is called gene expression. Gene expression is regulated to ensure that the correct proteins are made when and where they are needed. Regulation may occur at any stage of protein synthesis or processing.

-

- The regulation of transcription is controlled by regulatory proteins that bind to regions of DNA called regulatory elements, which are usually located near promoters. Most regulatory proteins are either activators that promote transcription or repressors that impede transcription.

- A regulatory element common to almost all eukaryotic genes is the TATA box. A number of regulatory proteins must bind to the TATA box in the promoter before transcription can proceed.

- The regulation of gene expression is extremely important during the early development of an organism. Homeobox genes, which encode for chains of amino acids called homeodomains, are important genes that regulate development.

- Some types of cancer occur because of mutations in genes that control the cell cycle. Cancer-causing mutations most often occur in two types of regulatory genes, called tumor-suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes.

- Mendel experimented with the inheritance of traits in pea plants, which have two different forms of several visible characteristics. Mendel crossed pea plants with different forms of traits.

-

- In Mendel's first set of experiments, he crossed plants that only differed in one characteristic. The results led to Mendel's first law of inheritance, called the law of segregation. This law states that there are two factors controlling a given characteristic, one of which dominates the other, and these factors separate and go to different gametes when a parent reproduces.

- In Mendel's second set of experiments, he experimented with two characteristics at a time. The results led to Mendel's second law of inheritance, called the law of independent assortment. This law states that the factors controlling different characteristics are inherited independently of each other.

- Mendel's laws of inheritance, now expressed in terms of genes, form the basis of genetics, the science of heredity. Mendel is often called the father of genetics.

- The position of a gene on a chromosome is its locus. A given gene may have different versions called alleles. Paired chromosomes of the same type are called homologous chromosomes and they have the same genes at the same loci.

- The alleles an individual inherits for a given gene make up the individual's genotype. An organism with two of the same alleles is called a homozygote, and an individual with two different alleles is called a heterozygote.

- The expression of an organism's genotype is referred to as its phenotype. A dominant allele is always expressed in the phenotype, even when just one dominant allele has been inherited. A recessive allele is expressed in the phenotype only when two recessive alleles have been inherited.

- In sexual reproduction, two parents produce gametes that unite in the process of fertilization to form a single-celled zygote. Gametes are haploid cells with only one of each pair of homologous chromosomes, and the zygote is a diploid cell with two of each pair of chromosomes.

- Meiosis is the type of cell division that produces four haploid daughter cells that may become gametes. Meiosis occurs in two stages, called meiosis I and meiosis II, each of which occurs in four phases (prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase).

- Meiosis is followed by gametogenesis, the process in which the haploid daughter cells change into mature gametes. Males produce gametes called sperm through spermatogenesis, and females produce gametes called eggs through oogenesis.

- Sexual reproduction produces offspring that are genetically unique. Crossing-over, independent alignment, and the random union of gametes result in a high degree of genetic variation.

- Mendelian inheritance refers to the inheritance of traits controlled by a single gene with two alleles, one of which may be completely dominant to the other. The pattern of inheritance of Mendelian traits depends on whether the traits are controlled by genes on autosomes or by genes on sex chromosomes.

-

- Examples of human autosomal Mendelian traits include albinism and Huntington's disease. Examples of human X-linked traits include red-green colour blindness and hemophilia.

- Two tools for studying inheritance are pedigrees and Punnett squares. A pedigree is a chart that shows how a trait is passed from generation to generation. A Punnett square is a chart that shows the expected ratios of possible genotypes in the offspring of two parents.

- Non-Mendelian inheritance refers to the inheritance of traits that have a more complex genetic basis than one gene with two alleles and complete dominance.

-

- Multiple allele traits are controlled by a single gene with more than two alleles. An example of a human multiple allele trait is ABO blood type.

- Codominance occurs when two alleles for a gene are expressed equally in the phenotype of heterozygotes. A human example of codominance occurs in the AB blood type, in which the A and B alleles are codominant.

- Incomplete dominance is the case in which the dominant allele for a gene is not completely dominant to a recessive allele, so an intermediate phenotype occurs in heterozygotes who inherit both alleles. A human example of incomplete dominance is Tay Sachs disease, in which heterozygotes produce half as much functional enzyme as normal homozygotes.

- Polygenic traits are controlled by more than one gene, each of which has a minor additive effect on the phenotype. This results in a continuum of phenotypes. Examples of human polygenic traits include skin colour and adult height. Many of these types of traits, as well as others, are affected by the environment, as well as by genes.

- Pleiotropy refers to the situation in which a gene affects more than one phenotypic trait. A human example of pleiotropy occurs with sickle cell anemia, which has multiple effects on the body.

- Epistasis is when one gene affects the expression of other genes. An example of epistasis is albinism, in which the albinism mutation negates the expression of skin colour genes.

- Genetic disorders are diseases, syndromes, or other abnormal conditions that are caused by mutations in one or more genes or by chromosomal alterations.

-

- Examples of genetic disorders caused by single-gene mutations include Marfan syndrome (autosomal dominant), sickle cell anemia (autosomal recessive), vitamin D-resistant rickets (X-linked dominant), and hemophilia A (X-linked recessive). Very few genetic disorders are caused by dominant mutations because these alleles are less likely to be passed on to successive generations.

- Nondisjunction is the failure of replicated chromosomes to separate properly during meiosis. This may result in genetic disorders caused by abnormal numbers of chromosomes. An example is Down syndrome, in which the individual inherits an extra copy of chromosome 21. Most chromosomal disorders involve the X chromosome. An example is Klinefelter's syndrome (XXY, XXXY).

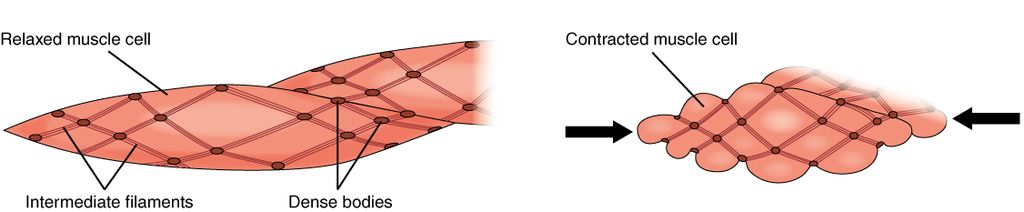

- Prenatal genetic testing (by amniocentesis, for example) can detect chromosomal alterations in utero. The symptoms of some genetic disorders can be treated or prevented. For example, symptoms of phenylketonuria (PKU) can be prevented by following a low-phenylalanine diet throughout life.

- Cures for genetic disorders are still in the early stages of development. One potential cure is gene therapy, in which normal genes are introduced into cells by a vector such as a virus to compensate for mutated genes.

- Genetic engineering is the use of technology to change the genetic makeup of living things for human purposes.

-

- Genetic engineering methods include gene cloning and the polymerase chain reaction. Gene cloning is the process of isolating and making copies of a DNA segment, such as a gene. The polymerase chain reaction makes many copies of a gene or other DNA segment.

- Genetic engineering can be used to transform bacteria so they are able to make human proteins, such as insulin. It can also be used to create transgenic crops, such as crops that yield more food or resist insect pests.

- Genetic engineering has raised a number of ethical, legal, and social issues including health, environmental, and privacy concerns.

- The human genome refers to all of the DNA of the human species. It consists of more than 3.3 billion base pairs divided into 20,500 genes on 23 pairs of chromosomes.

- The Human Genome Project (HGP) was a multi-billion dollar international research project that began in 1990. By 2003, it had sequenced and mapped the location of all of the DNA base pairs in the human genome. It published the results as a human reference genome that is available to anyone on the Internet.

- Sequencing of the human genome is helping researchers better understand cancer and genetic diseases. It is also helping them tailor medications to individual patients, which is the focus of the new field of pharmacogenomics. In addition, it is helping researchers better understand human evolution.

Chapter 5 Review

-

- What are the differences between a sequence of DNA and the sequence of mature mRNA that it produces?

- Scientists sometimes sequence DNA that they “reverse transcribe” from the mRNA in an organism’s cells, which is called complementary DNA (cDNA). Why do you think this technique might be particularly useful for understanding an organism’s proteins versus sequencing the whole genome (i.e. nuclear DNA) of the organism?

- A person has a hypothetical A a genotype. Answer the following questions about this genotype:

- What do A and a represent?

- If the person expresses only the phenotype associated with A, is this an example of complete dominance, codominance, or incomplete dominance? Explain your answer. Also, describe what the observed phenotypes would be if it were either of the two incorrect answers.

- Explain how a mutation that occurs in a parent can result in a genetic disorder in their child. Be sure to include which type of cell or cells in the parent must be affected in order for this to happen.

- What is the term for an allele that is not expressed in a heterozygote?

- What might happen if codons encoded for more than one amino acid?

- Explain why a human gene can be inserted into bacteria and can still produce the correct human protein, despite being in a very different organism.

- What is gene therapy? Why is gene therapy considered a type of biotechnology?

Chapter 5 Attributions and References

Unit 5.18 Image Attributions

- Figure 5.18.1 Rebeccas Pedigree Cancer by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) license.

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under

©CK-12 Foundation Licensed under  • Terms of Use • Attribution

• Terms of Use • Attribution

- Figure 5.18.2 Mutations_on_BRCA1 by National Cancer Institute (NCI) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Reference

Brainard, J/ CK-12 Foundation. (2016). Figure 1 Pedigree for Rebecca's family, as described in the beginning of this chapter, [digital image]. In CK-12 College Human Biology (Section 5.17) [online Flexbook]. CK12.org. https://www.ck12.org/book/ck-12-college-human-biology/section/5.17/

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Nail Art

Painting nails with coloured polish for aesthetic reasons is nothing new. In fact, there is evidence of this practice dating back to at least 3000 BCE. Today, painting and otherwise decorating the nails is big business, with annual revenues in the billions of dollars in North America alone! With all the attention (and money) given to nails as decorative objects, it’s easy to forget that they also have important biological functions.

What Are Nails?

Nails are accessory organs of the skin. They are made of sheets of dead keratinocytes and are found on the far (or distal) ends of the fingers and toes. The keratin in nails makes them hard, but flexible. Nails serve a number of purposes, including protecting the digits, enhancing sensations, and acting as tools.

Nail Anatomy

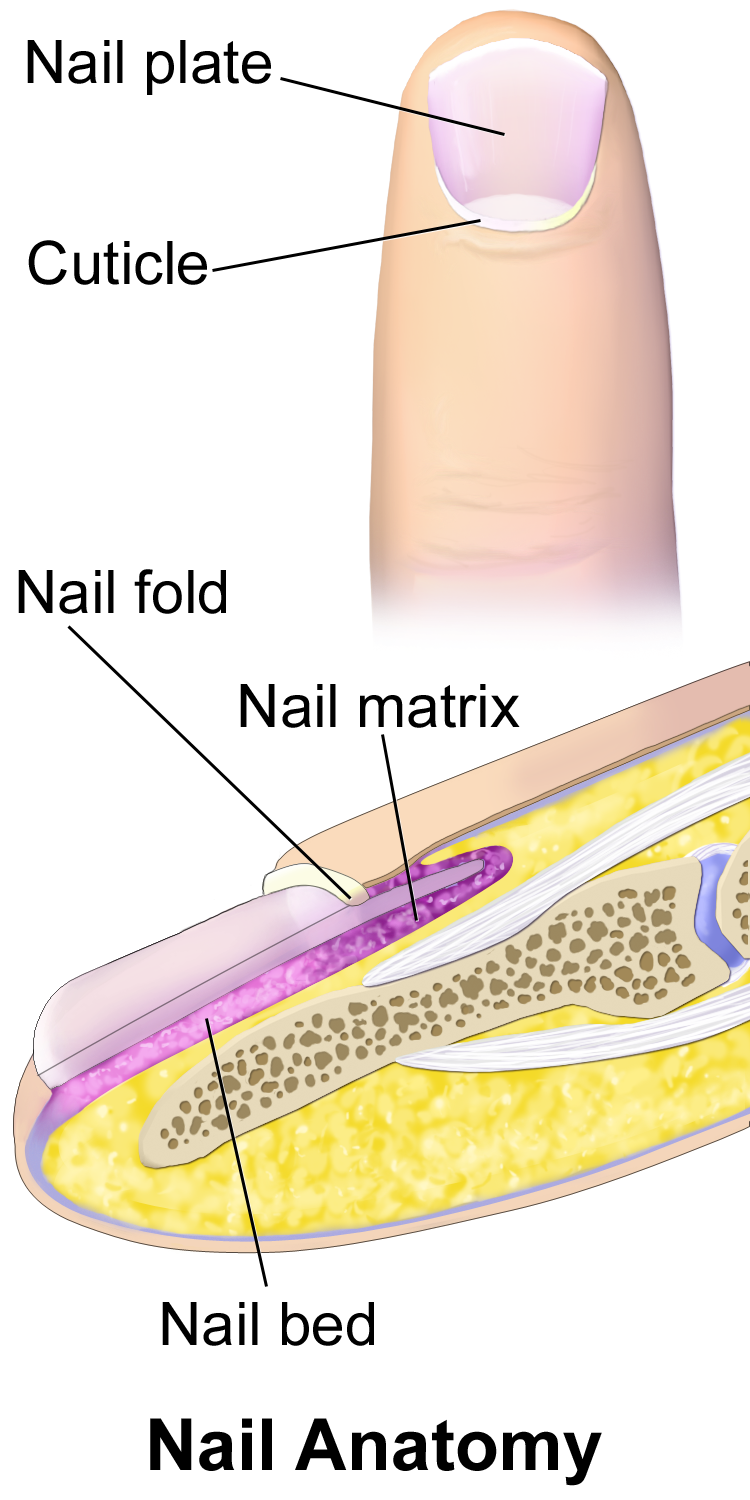

A nail has three main parts: the root, plate, and free margin. Other structures around or under the nail include the nail bed, cuticle, and nail fold. These structures are shown in Figure 10.6.2.

- The nail root is the portion of the nail found under the surface of the skin at the near (or proximal) end of the nail. It is where the nail begins.

- The nail plate (or body) is the portion of the nail that is external to the skin. It is the visible part of the nail.

- The free margin is the portion of the nail that protrudes beyond the distal end of the finger or toe. This is the part that is cut or filed to keep the nail trimmed.

- The nail bed is the area of skin under the nail plate. It is pink in colour, due to the presence of capillaries in the dermis.

- The cuticle is a layer of dead epithelial cells that overlaps and covers the edge of the nail plate. It helps to seal the edges of the nail to prevent infection of the underlying tissues.

- The nail fold is a groove in the skin in which the side edges of the nail plate are embedded.

Nail Growth

Nails grow from a deep layer of living epidermal tissue, known as the nail matrix, at the proximal end of the nail (see the bottom of the diagram in Figure 10.6.2). The nail matrix surrounds the nail root. It contains stem cells that divide to form keratinocytes, which are cells that produce keratin and make up the nail.

Formation of the Nail Root and Nail Plate

The keratinocytes produced by the nail matrix accumulate to form tough, hard, translucent sheets of dead cells filled with keratin. The sheets make up the nail root, which slowly grows out of the skin and becomes the nail plate when it reaches the skin surface. As the nail grows longer, the cells of the nail root and nail plate are pushed toward the distal end of the finger or toe by new cells being formed in the nail matrix. The upper epidermal cells of the nail bed also move along with the nail plate as it grows toward the tip of the digit.

The proximal end of the nail plate near the root has a whitish crescent shape called the lunula. This is where a small amount of the nail matrix is visible through the nail plate. The lunula is most pronounced in the nails of the thumbs, and may not be visible in the nails of the little fingers.

Rate of Nail Growth

Nails grow at an average rate of 3 mm a month. Fingernails, however, grow up to four times as fast as toenails. If a fingernail is lost, it takes between three and six months to regrow completely, whereas a toenail takes between 12 and 18 months to regrow. The actual rate of growth of an individual’s nails depends on many factors, including age, sex, season, diet, exercise level, and genes. If protected from breaking, nails can sometimes grow to be very long. The Chinese doctor in the photo below (Figure 10.6.3) has very long nails on two fingers of his left hand. This picture was taken in 1920 in China, where having long nails was a sign of aristocracy since it implied that one was wealthy enough to not have to do physical labour.

Functions of Nails

Both fingernails and toenails protect the soft tissues of the fingers and toes from injury. Fingernails also serve to enhance sensation and precise movements of the fingertips through the counter-pressure exerted on the pulp of the fingers by the nails. In addition, fingernails can function as several different types of tools. For example, they enable a fine precision grip like tweezers, and can also be used for cutting and scraping.

Nails and Health

Healthcare providers, particularly EMTs, often examine the fingernail beds as a quick and easy indicator of oxygen saturation of the blood, or the amount of blood reaching the extremities. If the nail beds are bluish or purple, it is generally a sign of low oxygen saturation. To see if blood flow to the extremities is adequate, a blanch test may be done. In this test, a fingernail is briefly depressed to turn the nail bed white by forcing the blood out of its capillaries. When the pressure is released, the pink colour of the nail bed should return within a second or two if there is normal blood flow. If the return to a pink colour is delayed, then it can be an indicator of low blood volume, due to dehydration or shock.

How the visible portion of the nails appears can be used as an indicator of recent health status. In fact, nails have been used as diagnostic tools for hundreds — if not thousands — of years. Nail abnormalities, such as deep grooves, brittleness, discolouration, or unusually thin or thick nails, may indicate various illnesses, nutrient deficiencies, drug reactions, or other health problems.

Nails — especially toenails — are common sites of fungal infections (shown in Figure 10.6.4), causing nails to become thickened and yellowish in colour. Toenails are more often infected than fingernails because they are often confined in shoes, which creates a dark, warm, moist environment where fungi can thrive. Toes also tend to have less blood flow than fingers, making it harder for the immune system to detect and stop infections in toenails.

Although nails are harder and tougher than skin, they are also more permeable. Harmful substances may be absorbed through the nails and cause health problems. Some of the substances that can pass through the nails include the herbicide Paraquat, fungicidal agents such as miconazole (e.g., Monistat), and sodium hypochlorite, which is an ingredient in common household bleach. Care should be taken to protect the nails from such substances when handling or immersing the hands in them by wearing latex or rubber gloves.

Feature: Reliable Sources

Do you get regular manicures or pedicures from a nail technician? If so, there is a chance that you are putting your health at risk. Nail tools that are not properly disinfected between clients may transmit infections from one person to another. Cutting the cuticles with scissors may create breaks in the skin that let infective agents enter the body. Products such as acrylics, adhesives, and UV gels that are applied to the nails may be harmful, especially if they penetrate the nails and enter the skin.

Use the Internet to find several reliable sources that address the health risks of professional manicures or pedicures. Try to find answers to the following questions:

- What training and certification are required for professional nail technicians?

- What licenses and inspections are required for nail salons?

- What hygienic practices should be followed in nail salons to reduce the risk of infections being transmitted to clients?

- Which professional nail products are potentially harmful to the human body and which are safer?

- How likely is it to have an adverse health consequence when you get a professional manicure or pedicure?

- What steps can you take to ensure that a professional manicure or pedicure is safe?

10.6 Summary

- Nails are accessory organs of the skin, consisting of sheets of dead, keratin-filled keratinocytes. The keratin in nails makes them hard, but flexible.

- A nail has three main parts: the nail root (which is under the epidermis), the nail plate (which is the visible part of the nail), and the free margin (which is the distal edge of the nail). Other structures under or around a nail include the nail bed, cuticle, and nail fold.

- A nail grows from a deep layer of living epidermal tissues — called the nail matrix — at the proximal end of the nail. Stem cells in the nail matrix keep dividing to allow nail growth, forming first the nail root and then the nail plate as the nail continues to grow longer and emerges from the epidermis.

- Fingernails grow faster than toenails. Actual rates of growth depend on many factors, such as age, sex, and season.

- Functions of nails include protecting the digits, enhancing sensations and precise movements of the fingertips, and acting as tools.

- The colour of the nail bed can be used to quickly assess oxygen and blood flow in a patient. How the nail plate grows out can reflect recent health problems, such as illness or nutrient deficiency.

- Nails — and especially toenails — are prone to fungus infections. Nails are more permeable than skin and can absorb several harmful substances, such as herbicides.

10.6 Review Questions

- What are nails?

-

- Explain why most of the nail plate looks pink.

- Describe a lunula.

- Explain how a nail grows.

- Identify three functions of nails.

- Give several examples of how nails are related to health.

- What is the cuticle of the nail composed of? What is the function of the cuticle? Why is it a bad idea to cut the cuticle during a manicure?

- Is the nail plate composed of living or dead cells?

10.6 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G35kPhbUZdg

Longest Fingernails - Guinness World Records 60th Anniversary,

Guinness World Records, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTSVHwzkYI4&feature=emb_logo

5 Things Your Nails Can Say About Your Health, SciShow, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7w2gCBL1MCg

Claws vs. Nails - Matthew Borths, TED-Ed, 2019.

Attributions

Figure 10.6.1

Nails by allison-christine-vPrqHSLdF28 [photo] by allison christine on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 10.6.2

Blausen_0406_FingerNailAnatomy by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 10.6.3

Chinese_doctor_with_long_finger_nails_(an_aristocrat),_ca.1920_(CHS-249) by Pierce, C.C. (Charles C.), 1861-1946 from the USC Digital Library on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 10.6.4

Toenail fungus Nagelpilz-3 by Pepsyrock on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 10.6.5

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA by Stoive at the English language Wikipedia, on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

References

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Guiness World Records. (2014, December 8). Longest fingernails - Guinness World Records 60th Anniversary. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G35kPhbUZdg

SciShow. (2015, September 14). 5 things your nails can say about your health. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aTSVHwzkYI4

TED-Ed. (2019, October 29). Claws vs. nails - Matthew Borths. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7w2gCBL1MCg

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Jaundiced Eyes

Did you ever hear of a person looking at something or someone with a “jaundiced eye”? It means to take a negative view, such as envy, maliciousness, or ill will. The expression may be based on the antiquated idea that liver bile is associated with such negative emotions as these, as well as the fact that excessive liver bile causes jaundice, or yellowing of the eyes and skin. Jaundice is likely a sign of a liver disorder or blockage of the duct that carries bile away from the liver. Bile contains waste products, making the liver an organ of excretion. Bile has an important role in digestion, which makes the liver an accessory organ of digestion, too.

What Are Accessory Organs of Digestion?

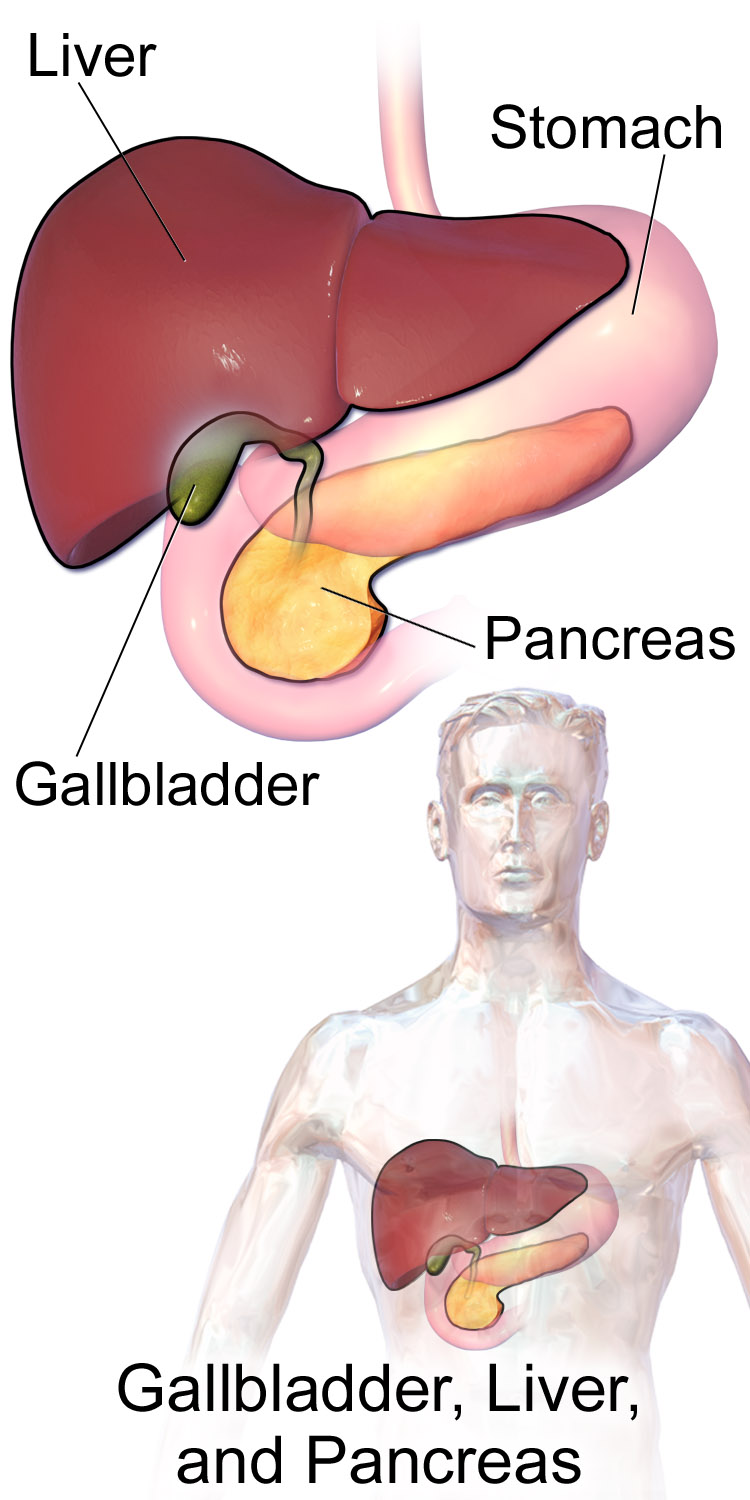

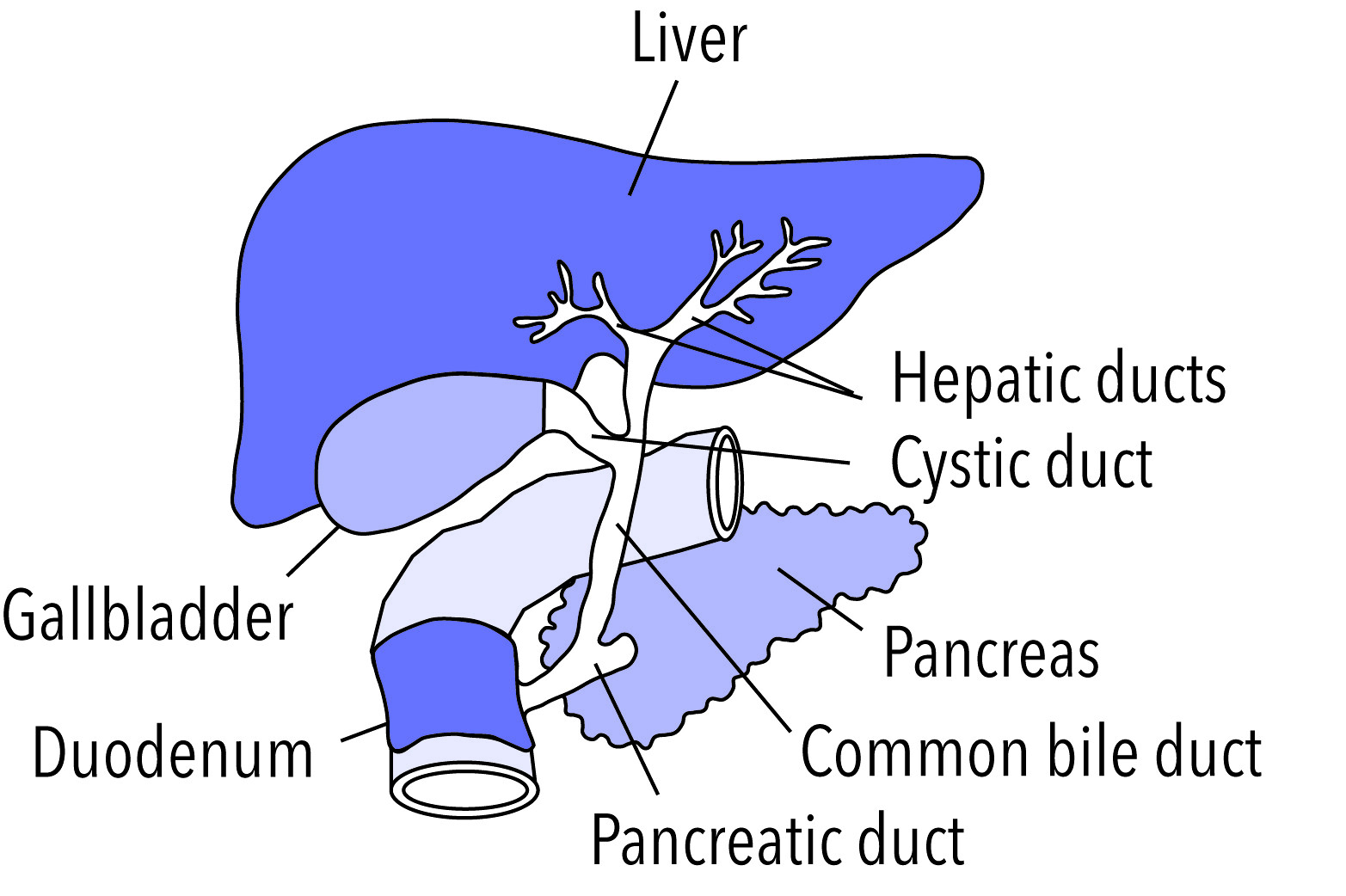

Accessory organs of digestion are organs that secrete substances needed for the chemical digestion of food, but through which food does not actually pass as it is digested. Besides the liver, the major accessory organs of digestion are the gallbladder and pancreas. These organs secrete or store substances that are needed for digestion in the first part of the small intestine — the duodenum — where most chemical digestion takes place. You can see the three organs and their locations in Figure 15.6.2.

Liver

The liver is a vital organ located in the upper right part of the abdomen. It lies just below the diaphragm, to the right of the stomach. The liver plays an important role in digestion by secreting bile, but the liver has a wide range of additional functions unrelated to digestion. In fact, some estimates put the number of functions of the liver at about 500! A few of them are described below.

Structure of the Liver

The liver is a reddish brown, wedge-shaped structure. In adults, the liver normally weighs about 1.5 kg (about 3.3 lb). It is both the heaviest internal organ and the largest gland in the human body. The liver is divided into four lobes of unequal size and shape. Each lobe, in turn, is made up of lobules, which are the functional units of the liver. Each lobule consists of millions of liver cells, called hepatic cells (or hepatocytes). They are the basic metabolic cells that carry out the various functions of the liver.

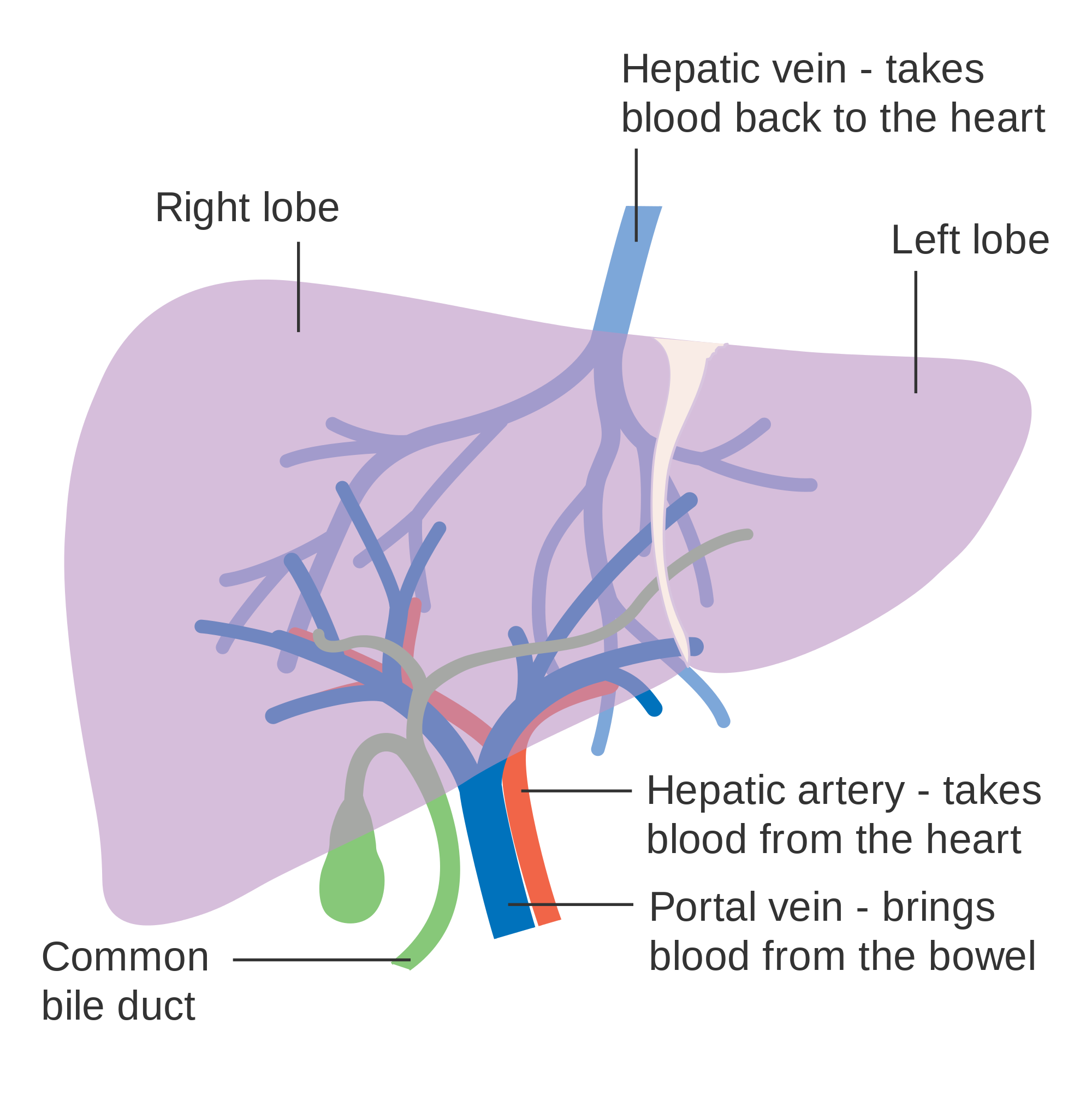

As shown in Figure 15.6.3, the liver is connected to two large blood vessels: the hepatic artery and the portal vein. The hepatic artery carries oxygen-rich blood from the aorta, whereas the portal vein carries blood that is rich in digested nutrients from the GI tract and wastes filtered from the blood by the spleen. The blood vessels subdivide into smaller arteries and capillaries, which lead into the liver lobules. The nutrients from the GI tract are used to build many vital biochemical compounds, and the wastes from the spleen are degraded and excreted.

Functions of the Liver

The main digestive function of the liver is the production of bile. Bile is a yellowish alkaline liquid that consists of water, electrolytes, bile salts, and cholesterol, among other substances, many of which are waste products. Some of the components of bile are synthesized by hepatocytes. The rest are extracted from the blood.

As shown in Figure 15.6.4, bile is secreted into small ducts that join together to form larger ducts, with just one large duct carrying bile out of the liver. If bile is needed to digest a meal, it goes directly to the duodenum through the common bile duct. In the duodenum, the bile neutralizes acidic chyme from the stomach and emulsifies fat globules into smaller particles (called micelles) that are easier to digest chemically by the enzyme lipase. Bile also aids with the absorption of vitamin K. Bile that is secreted when digestion is not taking place goes to the gallbladder for storage until the next meal. In either case, the bile enters the duodenum through the common bile duct.

Besides its roles in digestion, the liver has many other vital functions:

- The liver synthesizes glycogen from glucose and stores the glycogen as required to help regulate blood sugar levels. It also breaks down the stored glycogen to glucose and releases it back into the blood as needed.

- The liver stores many substances in addition to glycogen, including vitamins A, D, B12, and K. It also stores the minerals iron and copper.

- The liver synthesizes numerous proteins and many of the amino acids needed to make them. These proteins have a wide range of functions. They include fibrinogen, which is needed for blood clotting; insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), which is important for childhood growth; and albumen, which is the most abundant protein in blood serum and functions to transport fatty acids and steroid hormones in the blood.

- The liver synthesizes many important lipids, including cholesterol, triglycerides, and lipoproteins.

- The liver is responsible for the breakdown of many waste products and toxic substances. The wastes are excreted in bile or travel to the kidneys, which excrete them in urine.

The liver is clearly a vital organ that supports almost every other organ in the body. Because of its strategic location and diversity of functions, the liver is also prone to many diseases, some of which cause loss of liver function. There is currently no way to compensate for the absence of liver function in the long term, although liver dialysis techniques can be used in the short term. An artificial liver has not yet been developed, so liver transplantation may be the only option for people with liver failure.

Gallbladder

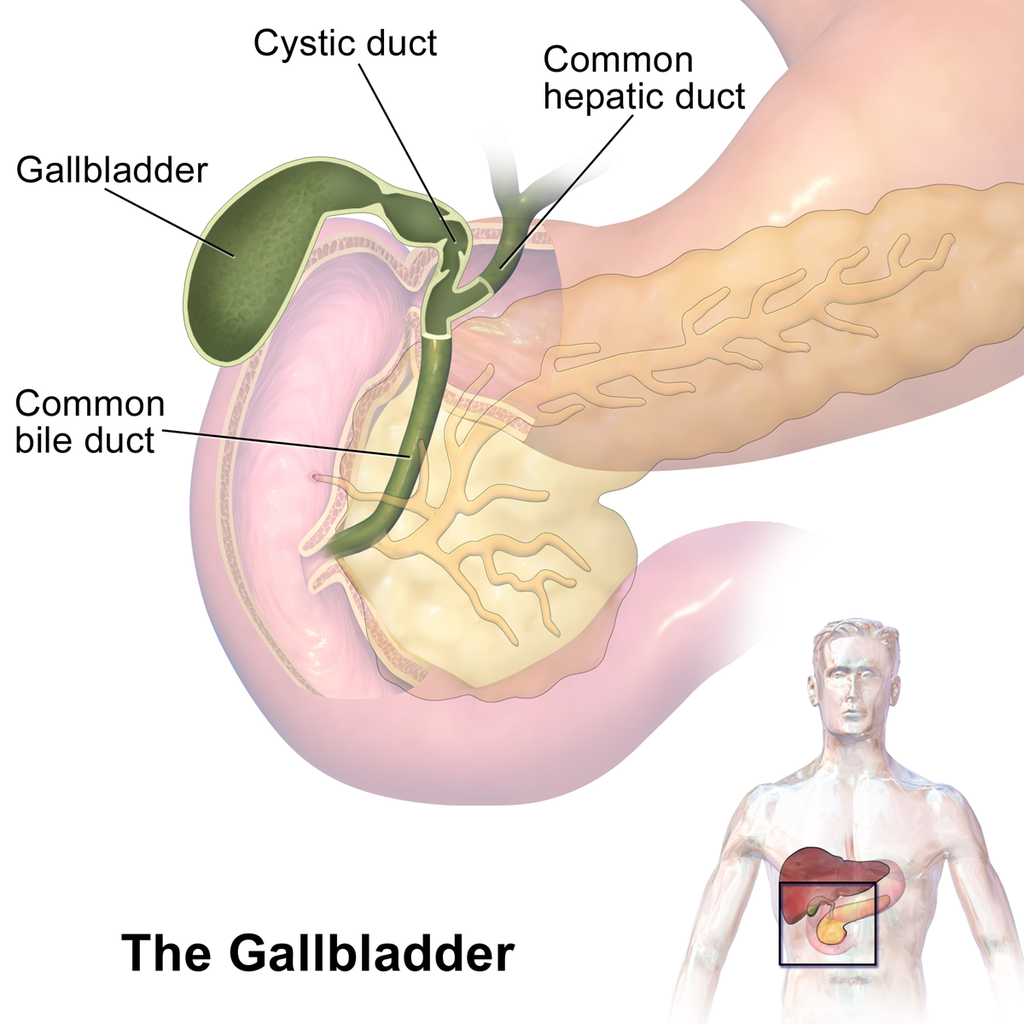

The gallbladder is a small, hollow, pouch-like organ that lies just under the right side of the liver (see Figure 15.6.5). It is about 8 cm (about 3 in) long and shaped like a tapered sac, with the open end continuous with the cystic duct. The gallbladder stores and concentrates bile from the liver until it is needed in the duodenum to help digest lipids. After the bile leaves the liver, it reaches the gallbladder through the cystic duct. At any given time, the gallbladder may store between 30 to 60 mL (1 to 2 oz) of bile. A hormone stimulated by the presence of fat in the duodenum signals the gallbladder to contract and force its contents back through the cystic duct and into the common bile duct to drain into the duodenum.

Pancreas

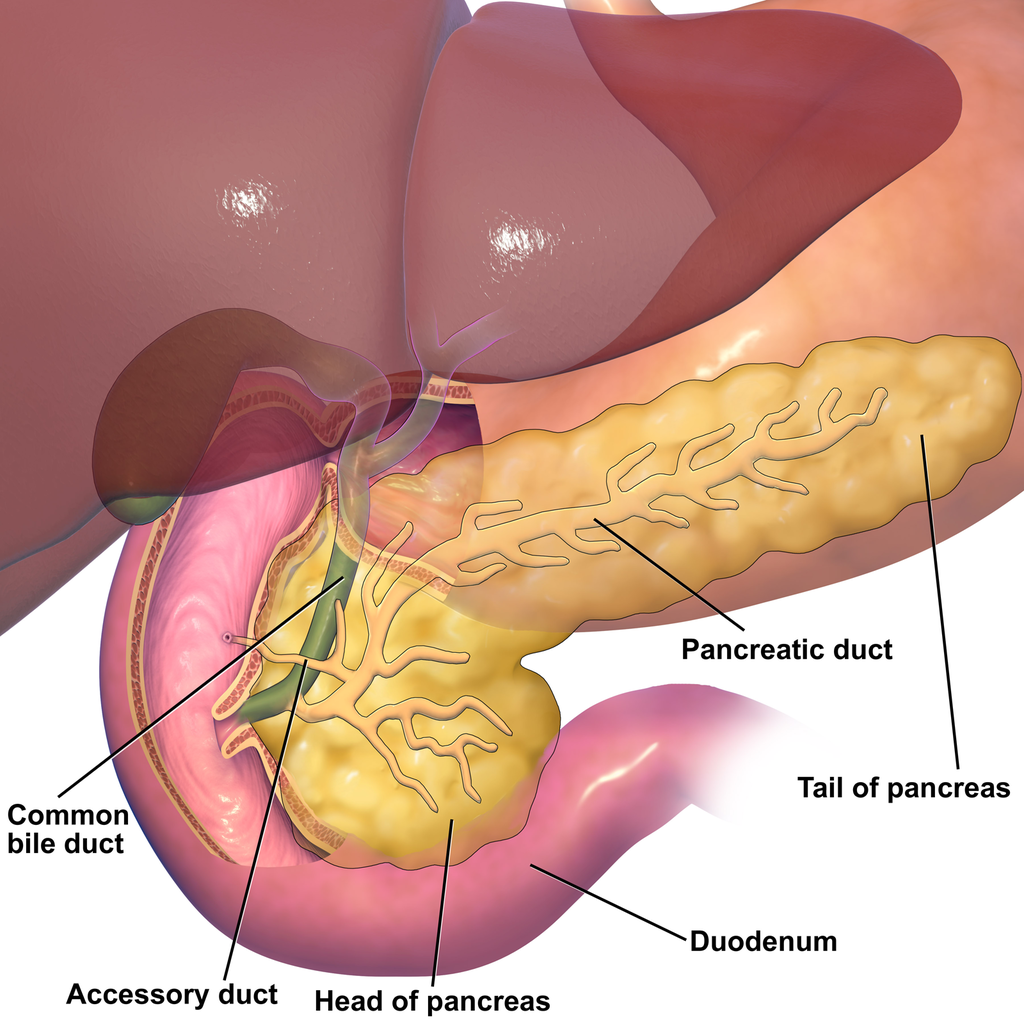

The pancreas is a glandular organ that is part of both the digestive system and the endocrine system. As shown in Figure 15.6.6, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach, with the head of the pancreas surrounded by the duodenum of the small intestine. The pancreas is about 15 cm (almost 6 in) long, and it has two major ducts: the main pancreatic duct and the accessory pancreatic duct. Both of these ducts drain into the duodenum.

As an endocrine gland, the pancreas secretes several hormones, including insulin and glucagon, which circulate in the blood. The endocrine hormones are secreted by clusters of cells called pancreatic islets (or islets of Langerhans). As a digestive organ, the pancreas secretes many digestive enzymes and also bicarbonate, which helps neutralize acidic chyme after it enters the duodenum. The pancreas is stimulated to secrete its digestive substances when food in the stomach and duodenum triggers the release of endocrine hormones into the blood that reach the pancreas via the bloodstream. The pancreatic digestive enzymes are secreted by clusters of cells called acini, and they travel through the pancreatic ducts to the duodenum. In the duodenum, they help to chemically break down carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids in chyme. The pancreatic digestive enzymes include:

- Amylase, which helps digest starch and other carbohydrates.

- Trypsin and chymotrypsin, which help digest proteins.

- Lipase, which helps digest lipids.

- Deoxyribonucleases and ribonucleases, which help digest nucleic acids.

15.6 Summary

- Accessory organs of digestion are organs that secrete substances needed for the chemical digestion of food, but through which food does not actually pass as it is digested. The accessory organs include the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. These organs secrete or store substances that are carried to the duodenum of the small intestine as needed for digestion.

- The liver is a large organ in the abdomen that is divided into lobes and smaller lobules, which consist of metabolic cells called hepatic cells, or hepatocytes. The liver receives oxygen in blood from the aorta through the hepatic artery. It receives nutrients in blood from the GI tract and wastes in blood from the spleen through the portal vein.

- The main digestive function of the liver is the production of the alkaline liquid called bile. Bile is carried directly to the duodenum by the common bile duct or to the gallbladder first for storage. Bile neutralizes acidic chyme that enters the duodenum from the stomach, and also emulsifies fat globules into smaller particles (micelles) that are easier to digest chemically.

- Other vital functions of the liver include regulating blood sugar levels by storing excess sugar as glycogen, storing many vitamins and minerals, synthesizing numerous proteins and lipids, and breaking down waste products and toxic substances.

- The gallbladder is a small pouch-like organ near the liver. It stores and concentrates bile from the liver until it is needed in the duodenum to neutralize chyme and help digest lipids.

- The pancreas is a glandular organ that secretes both endocrine hormones and digestive enzymes. As an endocrine gland, the pancreas secretes insulin and glucagon to regulate blood sugar. As a digestive organ, the pancreas secretes digestive enzymes into the duodenum through ducts. Pancreatic digestive enzymes include amylase (starches) trypsin and chymotrypsin (proteins), lipase (lipids), and ribonucleases and deoxyribonucleases (RNA and DNA).

15.6 Review Questions

- Name three accessory organs of digestion. How do these organs differ from digestive organs that are part of the GI tract?

-

- Describe the liver and its blood supply.

- Explain the main digestive function of the liver and describe the components of bile and it's importance in the digestive process.

- What type of secretions does the pancreas release as part of each body system?

- List pancreatic enzymes that work in the duodenum, along with the substances they help digest.

- What are two substances produced by accessory organs of digestion that help neutralize chyme in the small intestine? Where are they produced?

- People who have their gallbladder removed sometimes have digestive problems after eating high-fat meals. Why do you think this happens?

- Which accessory organ of digestion synthesizes cholesterol?

15.6 Explore More

https://youtu.be/8dgoeYPoE-0

What does the pancreas do? - Emma Bryce, TED-Ed. 2015.

https://youtu.be/wbh3SjzydnQ

What does the liver do? - Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2014.

https://youtu.be/a0d1yvGcfzQ

Scar wars: Repairing the liver, nature video, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 15.6.1

Scleral_Icterus by Sheila J. Toro on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0) license.

Figure 15.6.2

Blausen_0428_Gallbladder-Liver-Pancreas_Location by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 15.6.3

Diagram_showing_the_two_lobes_of_the_liver_and_its_blood_supply_CRUK_376.svg by Cancer Research UK on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 15.6.4

Gallbladder by NIH Image Gallery on Flickr is used CC BY-NC 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/) license.

Figure 15.6.5

Gallbladder_(organ) (1) by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license. (See a full animation of this medical topic at blausen.com.)

Figure 15.6.6

Blausen_0698_PancreasAnatomy by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

References

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

nature video. (2018, December 19). Scar wars: Repairing the liver. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a0d1yvGcfzQ&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2014, November 25). What does the liver do? - Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbh3SjzydnQ&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2015, February 19). What does the pancreas do? - Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8dgoeYPoE-0&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Crohn’s Rash

If you had a skin rash like the one shown in Figure 15.7.1, you probably wouldn’t assume that it was caused by a digestive system disease. However, that’s exactly why the individual in the picture has a rash. He has a gastrointestinal (GI) tract disorder called Crohn’s disease. This disease is one of a group of GI tract disorders that are known collectively as inflammatory bowel disease. Unlike other inflammatory bowel diseases, signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease may not be confined to the GI tract.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a collection of inflammatory conditions primarily affecting the intestines. The two principal inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Unlike Crohn’s disease — which may affect any part of the GI tract and the joints, as well as the skin — ulcerative colitis mainly affects just the colon and rectum. Both diseases occur when the body’s own immune system attacks the digestive system. Both diseases typically first appear in the late teens or early twenties, and occur equally in males and females. Approximately 270,000 Canadians are currently living with IBD, 7,000 of which are children. The annual cost of caring for these Canadians is estimated at $1.28 billion. The number of cases of IBD has been steadily increasing and it is expected that by 2030 the number of Canadians suffering from IBD will grow to 400,000.

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that may affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, among other body tissues. The most commonly affected region is the ileum, which is the final part of the small intestine. Signs and symptoms of Crohn’s disease typically include abdominal pain, diarrhea (with or without blood), fever, and weight loss. Malnutrition because of faulty absorption of nutrients may also occur. Potential complications of Crohn’s disease include obstructions and abscesses of the bowel. People with Crohn’s disease are also at slightly greater risk than the general population of developing bowel cancer. Although there is a slight reduction in life expectancy in people with Crohn’s disease, if the disease is well-managed, affected people can live full and productive lives. Approximately 135,000 Canadians are living with Crohn's disease.

Crohn’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors that lead to impairment of the generalized immune response (called innate immunity). The chronic inflammation of Crohn’s disease is thought to be the result of the immune system “trying” to compensate for the impairment. Dozens of genes are likely to be involved, only a few of which have been identified. Because of the genetic component, close relatives such as siblings of people with Crohn’s disease are many times more likely to develop the disease than people in the general population. Environmental factors that appear to increase the risk of the disease include smoking tobacco and eating a diet high in animal proteins. Crohn’s disease is typically diagnosed on the basis of a colonoscopy, which provides a direct visual examination of the inside of the colon and the ileum of the small intestine.

People with Crohn’s disease typically experience recurring periods of flare-ups followed by remission. There are no medications or surgical procedures that can cure Crohn’s disease, although medications such as anti-inflammatory or immune-suppressing drugs may alleviate symptoms during flare-ups and help maintain remission. Lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and smoking cessation, may also help control symptoms and reduce the likelihood of flare-ups. Surgery may be needed to resolve bowel obstructions, abscesses, or other complications of the disease.

Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease that causes inflammation and ulcers (sores) in the colon and rectum. Unlike Crohn’s disease, other parts of the GI tract are rarely affected in ulcerative colitis. The primary symptoms of the disease are lower abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. Weight loss, fever, and anemia may also be present. Symptoms typically occur intermittently with periods of no symptoms between flare-ups. People with ulcerative colitis have a considerably increased risk of colon cancer and should be screened for colon cancer more frequently than the general population. Ulcerative colitis, however, seems to primarily reduce the quality of life, and not the lifespan.

The exact cause of ulcerative colitis is not known. Theories about its cause involve immune system dysfunction, genetics, changes in normal gut bacteria, and lifestyle factors, such as a diet high in animal protein and the consumption of alcoholic beverages. Genetic involvement is suspected in part because ulcerative colitis tens to “run” in families. It is likely that multiple genes are involved. Diagnosis is typically made on the basis of colonoscopy and tissue biopsies.

Lifestyle changes, such as reducing the consumption of animal protein and alcohol, may improve symptoms of ulcerative colitis. A number of medications are also available to treat symptoms and help prolong remission. These include anti-inflammatory drugs and drugs that suppress the immune system. In cases of severe disease, removal of the colon and rectum may be required and can cure the disease.

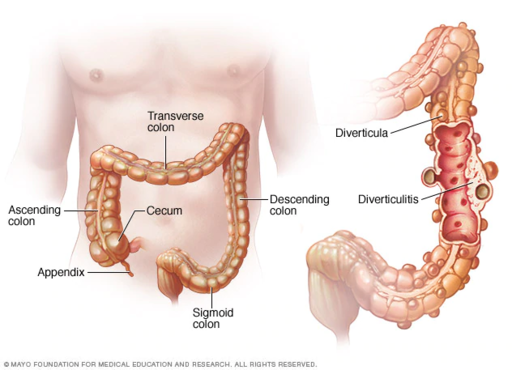

Diverticulitis

Diverticulitis is a digestive disease in which tiny pouches in the wall of the large intestine become infected and inflamed. Symptoms typically include lower abdominal pain of sudden onset. There may also be fever, nausea, diarrhea or constipation, and blood in the stool. Having large intestine pouches called diverticula (see Figure 15.7.2) that are not inflamed is called diverticulosis. Diverticulosis is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, and is more common in people who are obese. Infection and inflammation of the pouches (diverticulitis) occurs in about 10–25% of people with diverticulosis, and is more common at older ages. The infection is generally caused by bacteria.

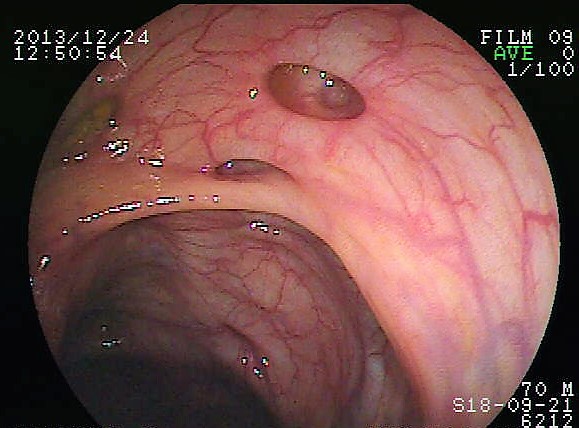

Diverticulitis can usually be diagnosed with a CT scan and can be monitored with a colonoscopy (as seen in Figure 15.7.3). Mild diverticulitis may be treated with oral antibiotics and a short-term liquid diet. For severe cases, intravenous antibiotics, hospitalization, and complete bowel rest (no nourishment via the mouth) may be recommended. Complications such as abscess formation or perforation of the colon require surgery.

Peptic Ulcer

A peptic ulcer is a sore in the lining of the stomach or the duodenum (first part of the small intestine). If the ulcer occurs in the stomach, it is called a gastric ulcer. If it occurs in the duodenum, it is called a duodenal ulcer. The most common symptoms of peptic ulcers are upper abdominal pain that often occurs in the night and improves with eating. Other symptoms may include belching, vomiting, weight loss, and poor appetite. Many people with peptic ulcers, particularly older people, have no symptoms. Peptic ulcers are relatively common, with about ten per cent of people developing a peptic ulcer at some point in their life.

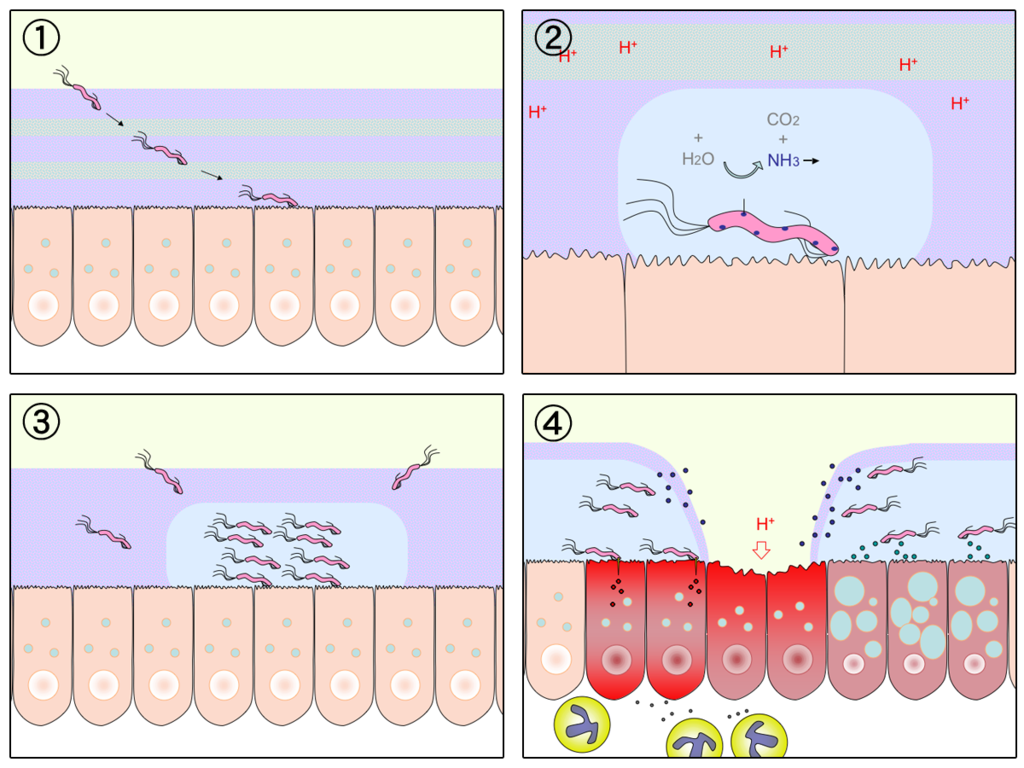

The most common cause of peptic ulcers is infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which may be transmitted by food, contaminated water, or human saliva (for example, by kissing or sharing eating utensils). Surprisingly, the bacterial cause of peptic ulcers was not discovered until the 1980s. The scientists who made the discovery are Australians Robin Warren and Barry J. Marshall. Although the two scientists eventually won a Nobel Prize for their discovery, their hypothesis was poorly received at first. To demonstrate the validity of their discovery, Marshall used himself in an experiment. He drank a culture of bacteria from a peptic ulcer patient and developed symptoms of peptic ulcer in a matter of days. His symptoms resolved on their own within a couple of weeks, but, at his wife's urging, he took antibiotics to kill any remaining bacteria. Marshall’s self-experiment was published in the Australian Medical Journal, and is among the most cited articles ever published in the journal. Figure 15.7.4 shows how H. pylori cause peptic ulcers.

Another relatively common cause of peptic ulcers is chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Additional contributing factors may include tobacco smoking and stress, although these factors have not been demonstrated conclusively to cause peptic ulcers independent of H. pylori infection. Contrary to popular belief, diet does not appear to play a role in either causing or preventing peptic ulcers. Eating spicy foods and drinking coffee and alcohol were once thought to cause peptic ulcers. These lifestyle choices are no longer thought to have much (if any) of an effect on the development of peptic ulcers.

Peptic ulcers are typically diagnosed on the basis of symptoms or the presence of H. pylori in the GI tract. However, endoscopy (shown in Figure 15.7.5), which allows direct visualization of the stomach and duodenum with a camera, may be required for a definitive diagnosis. Peptic ulcers are usually treated with antibiotics to kill H. pylori, along with medications to temporarily decrease stomach acid and aid in healing. Unfortunately, H. pylori has developed resistance to commonly used antibiotics, so treatment is not always effective. If a peptic ulcer has penetrated so deep into the tissues that it causes a perforation of the wall of the stomach or duodenum, then emergency surgery is needed to repair the damage.

Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea or stomach flu, is an acute and usually self-limiting infection of the GI tract by pathogens. Symptoms typically include some combination of diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of energy, and dehydration may also occur. The illness generally lasts less than two weeks, even without treatment, but in young children it is potentially deadly. Gastroenteritis is very common, especially in poorer nations. Worldwide, up to five billion cases occur each year, resulting in about 1.4 million deaths.

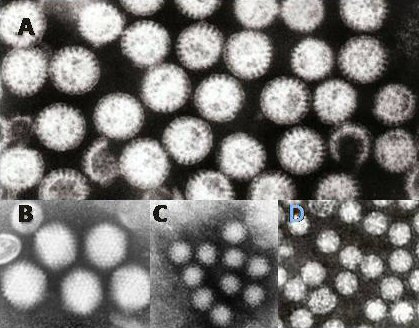

Commonly called “stomach flu,” gastroenteritis is unrelated to the influenza virus, although viruses are the most common cause of the disease (see Figure 15.7.6). In children, rotavirus is most often the cause which is why the British Columbia immunization schedule now includes a rotovirus vaccine. Norovirus is more likely to be the cause of gastroenteritis in adults. Besides viruses, other potential causes of gastroenteritis include fungi, bacteria (most often E. coli or Campylobacter jejuni), and protozoa(including Giardia lamblia, more commonly called Beaver Fever, described below). Transmission of pathogens may occur due to eating improperly prepared foods or foods left to stand at room temperature, drinking contaminated water, or having close contact with an infected individual.

Gastroenteritis is less common in adults than children, partly because adults have acquired immunity after repeated exposure to the most common infectious agents. Adults also tend to have better hygiene than children. If children have frequent repeated incidents of gastroenteritis, they may suffer from malnutrition, stunted growth, and developmental delays. Many cases of gastroenteritis in children can be avoided by giving them a rotavirus vaccine. Frequent and thorough handwashing can cut down on infections caused by other pathogens.

Treatment of gastroenteritis generally involves increasing fluid intake to replace fluids lost in vomiting or diarrhea. Oral rehydration solution, which is a combination of water, salts, and sugar, is often recommended. In severe cases, intravenous fluids may be needed. Antibiotics are not usually prescribed, because they are ineffective against viruses that cause most cases of gastroenteritis.

Giardiasis

Giardiasis, popularly known as beaver fever, is a type of gastroenteritis caused by a GI tract parasite, the single-celled protozoan Giardia lamblia (pictured in Figure 15.7.7). In addition to human beings, the parasite inhabits the digestive tract of a wide variety of domestic and wild animals, including cows, rodents, and sheep, as well as beavers (hence its popular name). Giardiasis is one of the most common parasitic infections in people the world over, with hundreds of millions of people infected worldwide each year.

Transmission of G. lamblia is via a fecal-oral route (as in, you got feces in your food). Those at greatest risk include travelers to countries where giardiasis is common, people who work in child-care settings, backpackers and campers who drink untreated water from lakes or rivers, and people who have close contact with infected people or animals in other settings. In Canada, Giardia is the most commonly identified intestinal parasite and approximately 3,000 Canadians will contract the parasite annually.

Symptoms of giardiasis can vary widely. About one-third third of people with the infection have no symptoms, whereas others have severe diarrhea with poor absorption of nutrients. Problems with absorption occur because the parasites inhibit intestinal digestive enzyme production, cause detrimental changes in microvilli lining the small intestine, and kill off small intestinal epithelial cells. The illness can result in weakness, loss of appetite, stomach cramps, vomiting, and excessive gas. Without treatment, symptoms may continue for several weeks. Treatment with anti-parasitic medications may be needed if symptoms persist longer or are particularly severe.

15.7 Summary

- Inflammatory bowel disease is a collection of inflammatory conditions primarily affecting the intestines. The diseases involve the immune system attacking the GI tract, and they have multiple genetic and environmental causes. Typical symptoms include abdominal pain and diarrhea, which show a pattern of repeated flare-ups interrupted by periods of remission. Lifestyle changes and medications may control flare-ups and extend remission. Surgery is sometimes required.

- The two principal inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Crohn’s disease may affect any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus, among other body tissues. Ulcerative colitis affects the colon and/or rectum.

- Some people have little pouches, called diverticula, in the lining of their large intestine, a condition called diverticulosis. People with diverticulosis may develop diverticulitis, in which one or more of the diverticula become infected and inflamed. Diverticulitis is generally treated with antibiotics and bowel rest. Sometimes, surgery is required.

- A peptic ulcer is a sore in the lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (duodenal ulcer). The most common cause is infection with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. NSAIDs (such as aspirin) can also cause peptic ulcers, and some lifestyle factors may play contributing roles. Antibiotics and acid reducers are typically prescribed, and surgery is not often needed.

- Gastroenteritis, or infectious diarrhea, is an acute and usually self-limiting infection of the GI tract by pathogens, most often viruses. Symptoms typically include diarrhea, vomiting, and/or abdominal pain. Treatment includes replacing lost fluids. Antibiotics are not usually effective.

- Giardiasis is a type of gastroenteritis caused by infection of the GI tract with the protozoa parasite Giardia lamblia. It may cause malnutrition. Generally self-limiting, severe or long-lasting cases may require antibiotics.

15.7 Review Questions

-

-

- Compare and contrast Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

- How are diverticulosis and diverticulitis related?

- Identify the cause of giardiasis. Why may it cause malabsorption?

- Name three disorders of the GI tract that can be caused by bacteria.

- Name one disorder of the GI tract that can be helped by anti-inflammatory medications, and one that can be caused by chronic use of anti-inflammatory medications.

- Describe one reason why it can be dangerous to drink untreated water.

15.7 Explore More

https://youtu.be/H5zin8jKeT0

Who's at risk for colon cancer? - Amit H. Sachdev and Frank G. Gress, TED-Ed, 2018.

https://youtu.be/V_U6czbDHLE

The surprising cause of stomach ulcers - Rusha Modi, TED-Ed, 2017.

Attributions

Figure 15.7.1

BADAS_Crohn by Dayavathi Ashok and Patrick Kiely/ Journal of medical case reports on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 15.7.2

512px-Ds00070_an01934_im00887_divert_s_gif.webp by Lfreeman04 on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 15.7.3

Colon_diverticulum by melvil on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 15.7.4

H_pylori_ulcer_diagram by Y_tambe on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 15.7.5

1024px-Endoscopy_training by Yuya Tamai on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 15.7.6

Gastroenteritis_viruses by Dr. Graham Beards [en:User:Graham Beards] at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 15.7.7

Giardia_lamblia_SEM_8698_lores by Janice Haney Carr from CDC/ Public Health Image Library (PHIL) ID# 8698 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

References

Ashok, D., & Kiely, P. (2007). Bowel associated dermatosis - arthritis syndrome: a case report. Journal of medical case reports, 1, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-1-81

Marshall, B. J., Armstrong, J. A., McGechie, D. B., & Glancy, R. J. (1985). Attempt to fulfil Koch's postulates for pyloric Campylobacter. The Medical Journal of Australia, 142(8), 436–439.

Marshall, B. J., McGechie, D. B., Rogers, P. A., & Glancy, R. J. (1985). Pyloric campylobacter infection and gastroduodenal disease. The Medical Journal of Australia, 142(8), 439–444.

TED-Ed. (2017, September 28). The surprising cause of stomach ulcers - Rusha Modi. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_U6czbDHLE&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, January 4). Who's at risk for colon cancer? - Amit H. Sachdev and Frank G. Gress. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H5zin8jKeT0&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Marvelous Muscles

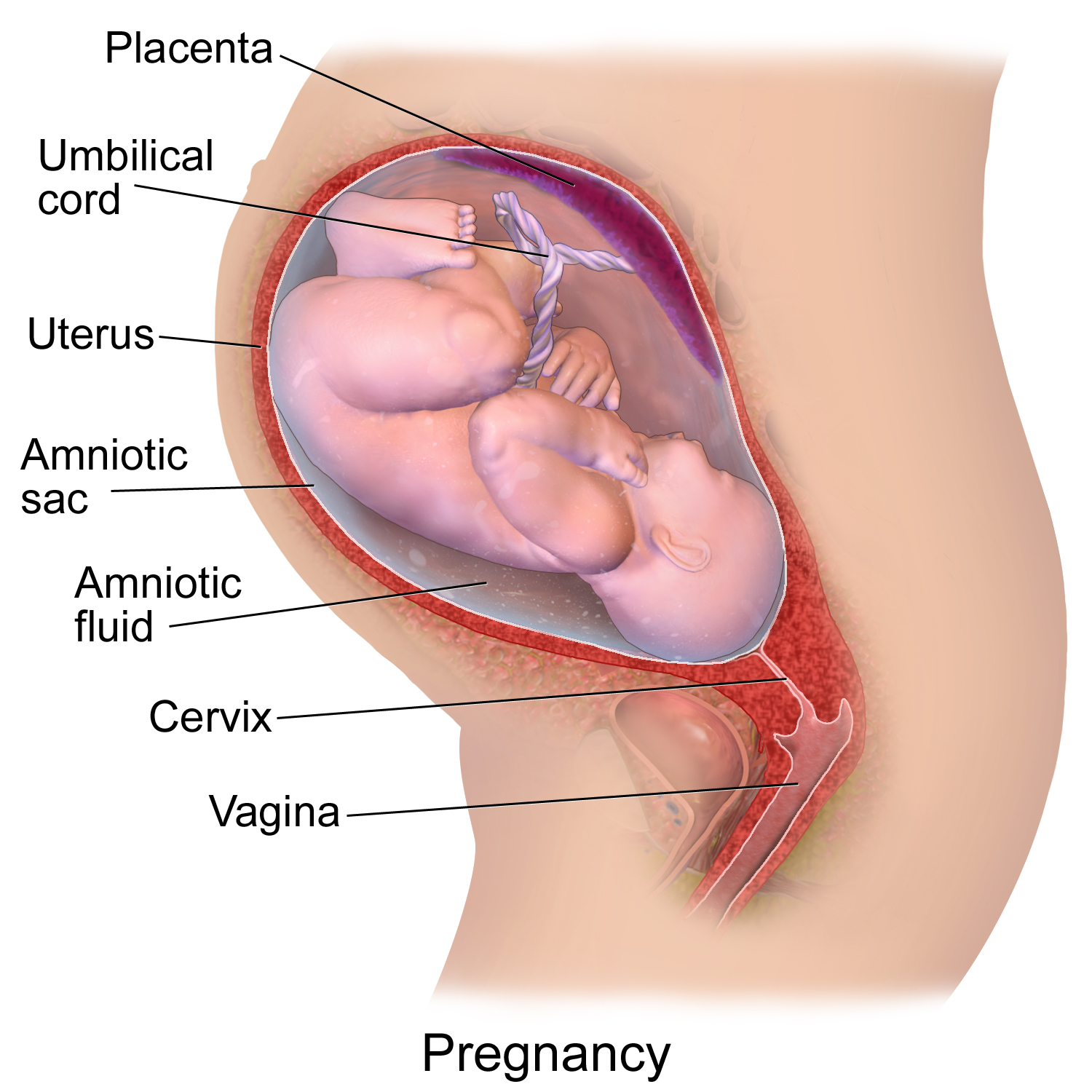

Does the word muscle make you think of the well-developed muscles of a weightlifter, like the woman in Figure 12.2.1? Her name is Natalia Zabolotnaya, and she’s a Russian Olympian. The muscles that are used to lift weights are easy to feel and see, but they aren’t the only muscles in the human body. Many muscles are deep within the body, where they form the walls of internal organs and other structures. You can flex your biceps at will, but you can’t control internal muscles like these. It’s a good thing that these internal muscles work without any conscious effort on your part, because movement of these muscles is essential for survival. Muscles are the organs of the muscular system.

What Is the Muscular System?

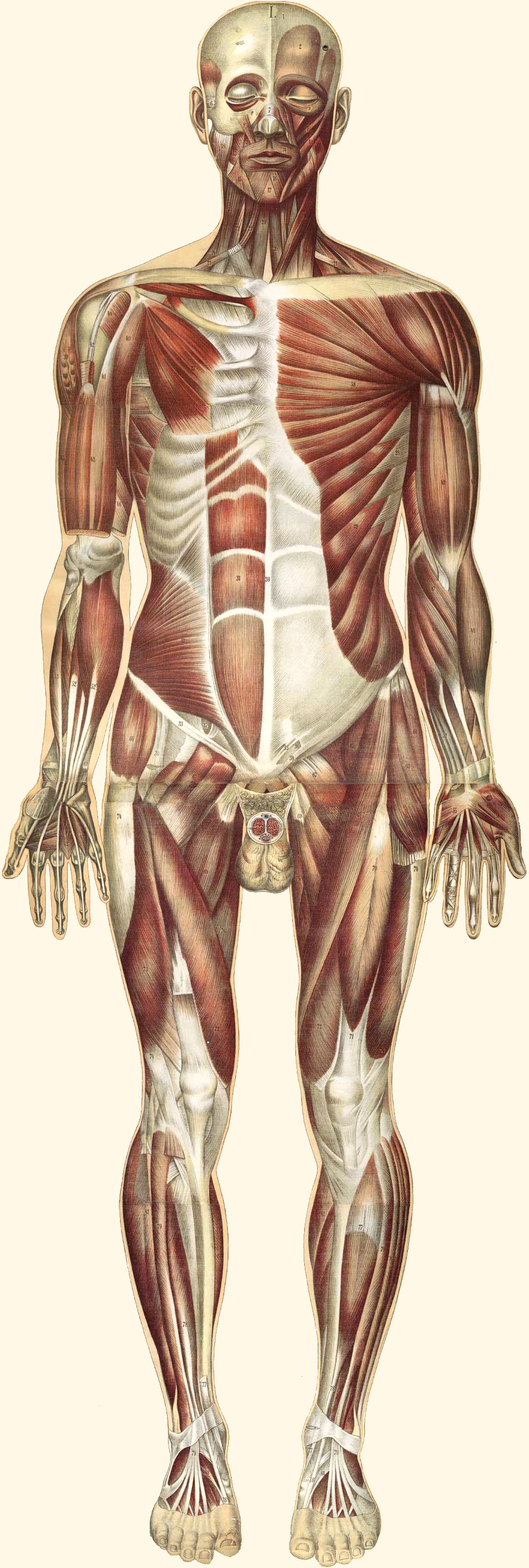

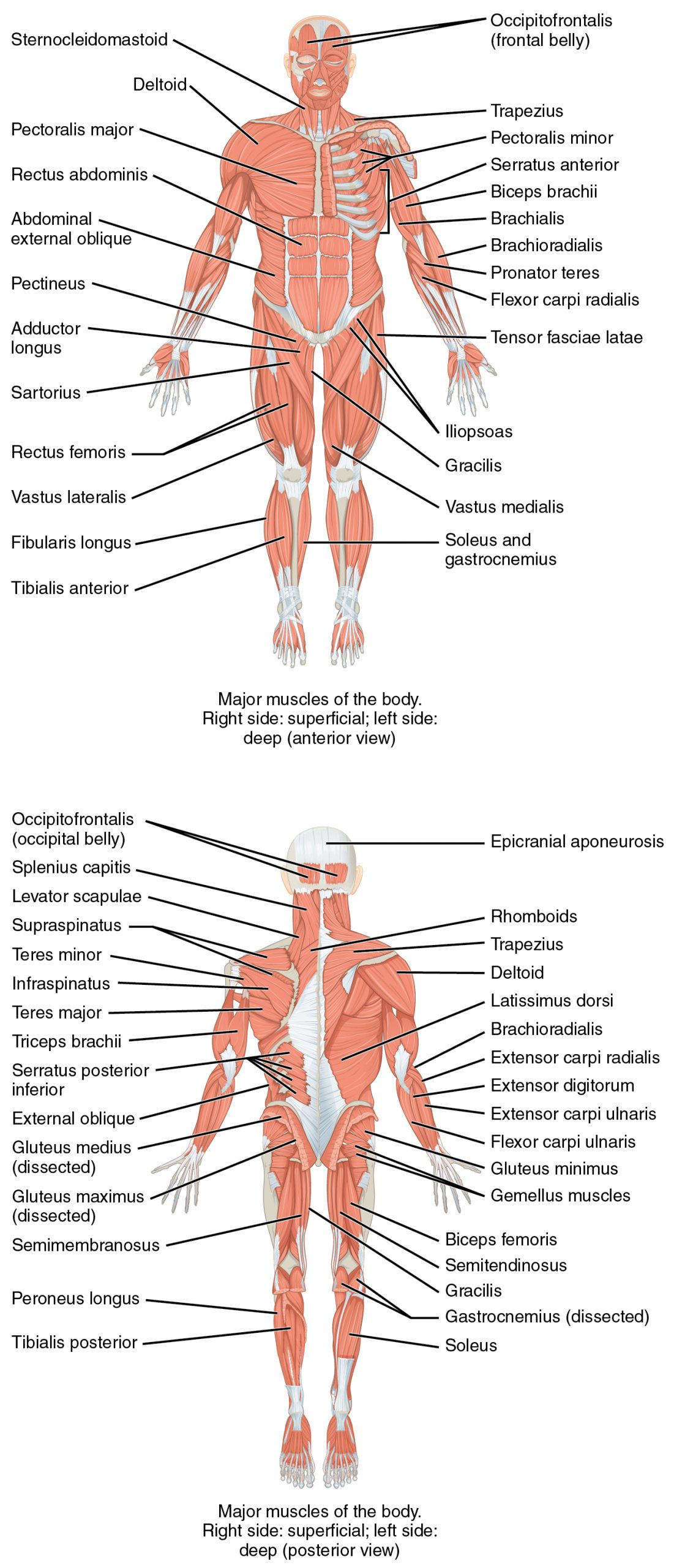

The muscular system consists of all the muscles of the body. The largest percentage of muscles in the muscular system consists of skeletal muscles, which are attached to bones and enable voluntary body movements (shown in Figure 12.2.2). There are almost 650 skeletal muscles in the human body, many of them shown in Figure 12.2.2. Besides skeletal muscles, the muscular system also includes cardiac muscle, which makes up the walls of the heart, and smooth muscles, which control movement in other internal organs and structures.

Muscle Structure and Function

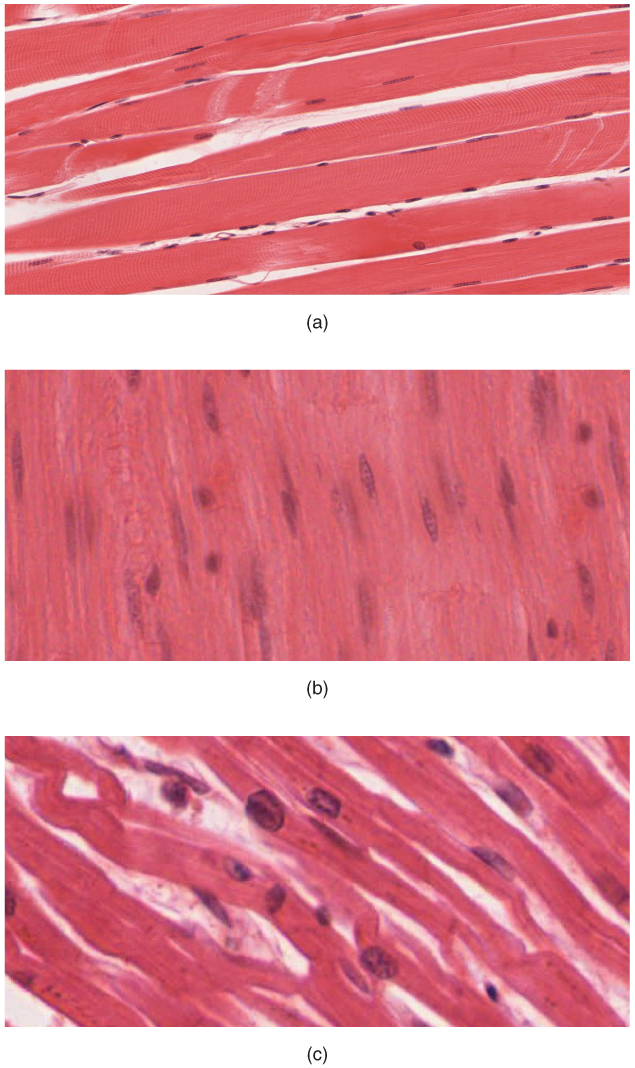

Muscles are organs composed mainly of muscle cells, which are also called muscle fibres (mainly in skeletal and cardiac muscle) or myocytes (mainly in smooth muscle). Muscle cells are long, thin cells that are specialized for the function of contracting. They contain protein filaments that slide over one another using energy in ATP. The sliding filaments increase the tension in — or shorten the length of — muscle cells, causing a contraction. Muscle contractions are responsible for virtually all the movements of the body, both inside and out.

Skeletal muscles are attached to bones of the skeleton. When these muscles contract, they move the body. They allow us to use our limbs in a variety of ways, from walking to turning cartwheels. Skeletal muscles also maintain posture and help us to keep balance.

Smooth muscles in the walls of blood vessels contract to cause vasoconstriction, which may help conserve body heat. Relaxation of these muscles causes vasodilation, which may help the body lose heat. In the organs of the digestive system, smooth muscles squeeze food through the gastrointestinal tract by contracting in sequence to form a wave of muscle contractions called peristalsis. Think of squirting toothpaste through a tube by applying pressure in sequence from the bottom of the tube to the top, and you have a good idea of how food is moved by muscles through the digestive system. Peristalsis of smooth muscles also moves urine through the urinary tract.

Cardiac muscle tissue is found only in the walls of the heart. When cardiac muscle contracts, it makes the heart beat. The pumping action of the beating heart keeps blood flowing through the cardiovascular system.

Muscle Hypertrophy and Atrophy

Muscles can grow larger, or hypertrophy. This generally occurs through increased use, although hormonal or other influences can also play a role. The increase in testosterone that occurs in males during puberty, for example, causes a significant increase in muscle size. Physical exercise that involves weight bearing or resistance training can increase the size of skeletal muscles in virtually everyone. Exercises (such as running) that increase the heart rate may also increase the size and strength of cardiac muscle. The size of muscle, in turn, is the main determinant of muscle strength, which may be measured by the amount of force a muscle can exert.

Muscles can also grow smaller, or atrophy, which can occur through lack of physical activity or from starvation. People who are immobilized for any length of time — for example, because of a broken bone or surgery — lose muscle mass relatively quickly. People in concentration or famine camps may be so malnourished that they lose much of their muscle mass, becoming almost literally just “skin and bones.” Astronauts on the International Space Station may also lose significant muscle mass because of weightlessness in space (see Figure 12.2.3).

Many diseases, including cancer and AIDS, are often associated with muscle atrophy. Atrophy of muscles also happens with age. As people grow older, there is a gradual decrease in the ability to maintain skeletal muscle mass, known as sarcopenia. The exact cause of sarcopenia is not known, but one possible cause is a decrease in sensitivity to growth factors that are needed to maintain muscle mass. Because muscle size determines strength, muscle atrophy causes a corresponding decline in muscle strength.

In both hypertrophy and atrophy, the number of muscle fibres does not change. What changes is the size of the muscle fibres. When muscles hypertrophy, the individual fibres become wider. When muscles atrophy, the fibres become narrower.

Interactions with Other Body Systems

Muscles cannot contract on their own. Skeletal muscles need stimulation from motor neurons in order to contract. The point where a motor neuron attaches to a muscle is called a neuromuscular junction. Let’s say you decide to raise your hand in class. Your brain sends electrical messages through motor neurons to your arm and shoulder. The motor neurons, in turn, stimulate muscle fibres in your arm and shoulder to contract, causing your arm to rise.

Involuntary contractions of smooth and cardiac muscles are also controlled by electrical impulses, but in the case of these muscles, the impulses come from the autonomic nervous system (smooth muscle) or specialized cells in the heart (cardiac muscle). Hormones and some other factors also influence involuntary contractions of cardiac and smooth muscles. For example, the fight-or-flight hormone adrenaline increases the rate at which cardiac muscle contracts, thereby speeding up the heartbeat.

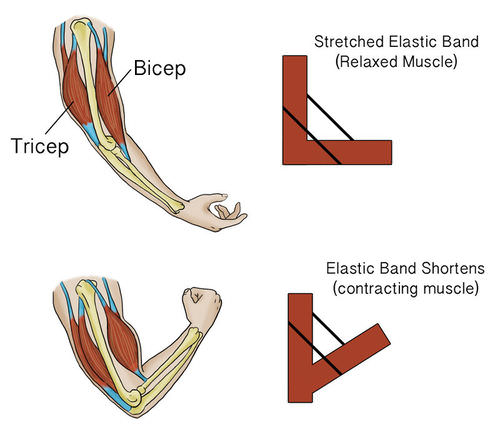

Muscles cannot move the body on their own. They need the skeletal system to act upon. The two systems together are often referred to as the musculoskeletal system. Skeletal muscles are attached to the skeleton by tough connective tissues called tendons. Many skeletal muscles are attached to the ends of bones that meet at a joint. The muscles span the joint and connect the bones. When the muscles contract, they pull on the bones, causing them to move. The skeletal system provides a system of levers that allow body movement. The muscular system provides the force that moves the levers.

12.2 Summary

- The muscular system consists of all the muscles of the body. There are three types of muscle: skeletal muscle (which is attached to bones and enables voluntary body movements), cardiac muscle (which makes up the walls of the heart and makes it beat), and smooth muscle (which is found in the walls of internal organs and other internal structures and controls their movements).

- Muscles are organs composed mainly of muscle cells, which may also be called muscle fibres or myocytes. Muscle cells are specialized for the function of contracting, which occurs when protein filaments inside the cells slide over one another using energy in ATP.