11.1 Case Study: Your Support System

Case Study: A Pain in the Foot

Sophia loves wearing high heels when she goes out at night, like the stiletto heels shown in Figure 11.1.1. She knows they are not the most practical shoes, but she likes how they look.

Lately, she has been experiencing pain in the balls of her feet — the area just behind the toes. Even when she trades her heels for comfortable sneakers, it still hurts when she stands or walks.

What could be going on? She searches online to try to find some answers. She finds a reputable source for foot pain information — a website from a professional organization of physicians that peer reviews the content by experts in the field. There, she reads about a condition called metatarsalgia, which produces pain in the ball of the foot that sounds very similar to what she is experiencing.

She learns that a common cause of metatarsalgia is the wearing of high heels. Shoes like this push the foot into an abnormal position, resulting in excessive pressure being placed on the ball of the foot. Looking at the photograph above (Figure 11.1.1), you can imagine how much of the woman’s body weight is focused on the ball of her foot, because of the shape of her high heels. If she were not wearing high heels, her weight would be more evenly distributed across her foot.

As she reads more about the hazards of high heels, Sophia learns that they can also cause foot deformities, such as hammertoes, bunions, and small cracks in bone called stress fractures. High heels may even contribute to the development of osteoarthritis of the knees at an early age.

These conditions caused by high heels are all problems of the skeletal system, which includes bones and connective tissues that hold bones together and cushion them at joints (such as the knee). The skeletal system supports the body’s weight and protects internal organs, but as you will learn as you read this chapter, it also carries out a variety of other important physiological functions.

At the end of the chapter, you will find out why high heels can cause these skeletal system problems, as well as the steps Sophia takes to recover from her foot pain and prevent long-term injury.

Chapter 11 Overview: Skeletal System

In this chapter, you will learn about the structure, functions, growth, repair, and disorders of the skeletal system. Specifically you will learn about:

- The components of the skeletal system, which includes bones, ligaments, and cartilage.

- The functions of the skeletal system, including supporting and giving shape to the body; protecting internal organs; facilitating movement; producing blood cells; helping maintain homeostasis; and producing endocrine hormones.

- The organization and functions of the two main divisions of the skeletal system: the axial skeletal system (which includes the skull, spine, and rib cage), and the appendicular skeletal system (which includes the limbs and girdles that attach the limbs to the axial skeleton).

- The tissues and cells that make up bones, along with their specific functions, which include making new bone, breaking down bone, producing blood cells, and regulating mineral homeostasis.

- The different types of bones in the skeletal system, based on shape and location.

- How bones grow, remodel, and repair themselves.

- The different types of joints between bones, where they are located, and the ways in which they allow different types of movement, depending on their structure.

- The causes, risk factors, and treatments for the two most common disorders of the skeletal system — osteoporosis and osteoarthritis.

As you read this chapter, think about the following questions:

- Sophia suspects she has a condition called metatarsalgia. This term is related to the term “metatarsals.” What are metatarsals, where are they located, and how do you think they are related to metatarsalgia?

- High heels can cause stress fractures, which are small cracks in bone that usually appear after repeated mechanical stress, instead of after a significant acute injury. What other condition described in this chapter involves a similar process?

- What are bunions and osteoarthritis of the knee? Why do you think they can be caused by wearing high heels?

Attribution

Figure 11.1.1

Heels by apostolos-vamvouras-_pdbqMcNWus [photo] by Apostolos Vamvouras on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Reference

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.p.). Metatarsalgia [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/metatarsalgia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354790

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Bacteria Attack!

The colourful image in Figure 4.3.1 shows a bacterial cell (in green) attacking human red blood cells. The bacterium causes a disease called relapsing fever. The bacterial and human cells look very different in size and shape. Although all living cells have certain things in common — such as a plasma membrane and cytoplasm — different types of cells, even within the same organism, may have their own unique structures and functions. Cells with different functions generally have different shapes that suit them for their particular job. Cells vary not only in shape, but also in size, as this example shows. In most organisms, however, even the largest cells are no bigger than the period at the end of this sentence. Why are cells so small?

Explaining Cell Size

Most organisms, even very large ones, have microscopic cells. Why don't cells get bigger instead of remaining tiny and multiplying? Why aren't you one giant cell rolling around school? What limits cell size?

Once you know how a cell functions, the answers to these questions are clear. To carry out life processes, a cell must be able to quickly pass substances in and out of the cell. For example, it must be able to pass nutrients and oxygen into the cell and waste products out of the cell. Anything that enters or leaves a cell must cross its outer surface. The size of a cell is limited by its need to pass substances across that outer surface.

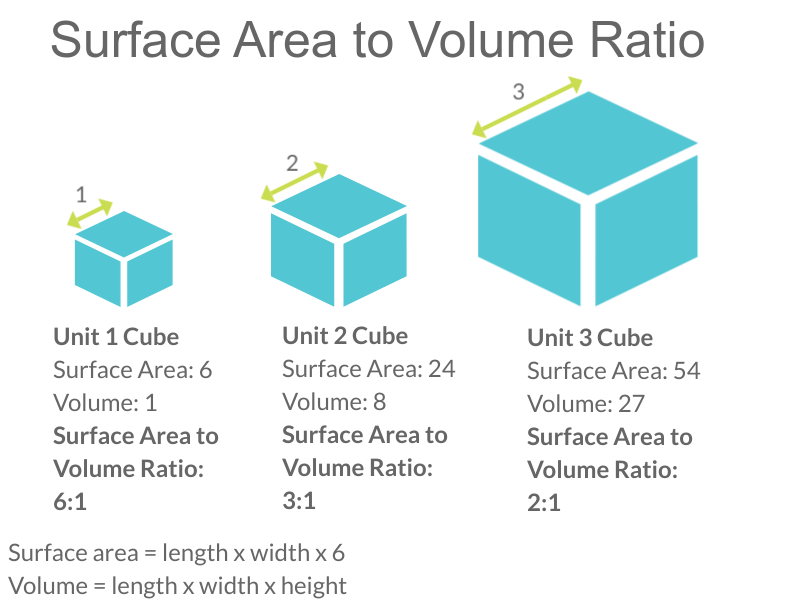

Look at the three cubes in Figure 4.3.2. A larger cube has less surface area relative to its volume than a smaller cube. This relationship also applies to cells — a larger cell has less surface area relative to its volume than a smaller cell. A cell with a larger volume also needs more nutrients and oxygen, and produces more waste. Because all of these substances must pass through the surface of the cell, a cell with a large volume will not have enough surface area to allow it to meet its needs. The larger the cell is, the smaller its ratio of surface area to volume, and the more difficult it will be for the cell to get rid of its waste and take in necessary substances. This is what limits the size of the cell.

Cell Form and Function

Cells with different functions often have varying shapes. The cells pictured below (Figure 4.3.3) are just a few examples of the many different shapes that human cells may have. Each type of cell has characteristics that help it do its job. The job of the nerve cell, for example, is to carry messages to other cells. The nerve cell has many long extensions that reach out in all directions, allowing it to pass messages to many other cells at once. Do you see the tail of each tiny sperm cell? Its tail helps a sperm cell "swim" through fluids in the female reproductive tract in order to reach an egg cell. The white blood cell has the job of destroying bacteria and other pathogens. It is a large cell that can engulf foreign invaders.

Figure 4.3.3 Human cells may have many different shapes that help them to do their jobs.

Cells With and Without a Nucleus

The nucleus is a basic cell structure present in many — but not all — living cells. The nucleus of a cell is a structure in the cytoplasm that is surrounded by a membrane (the nuclear membrane) and contains DNA. Based on whether or not they have a nucleus, there are two basic types of cells: prokaryotic cells and eukaryotic cells.

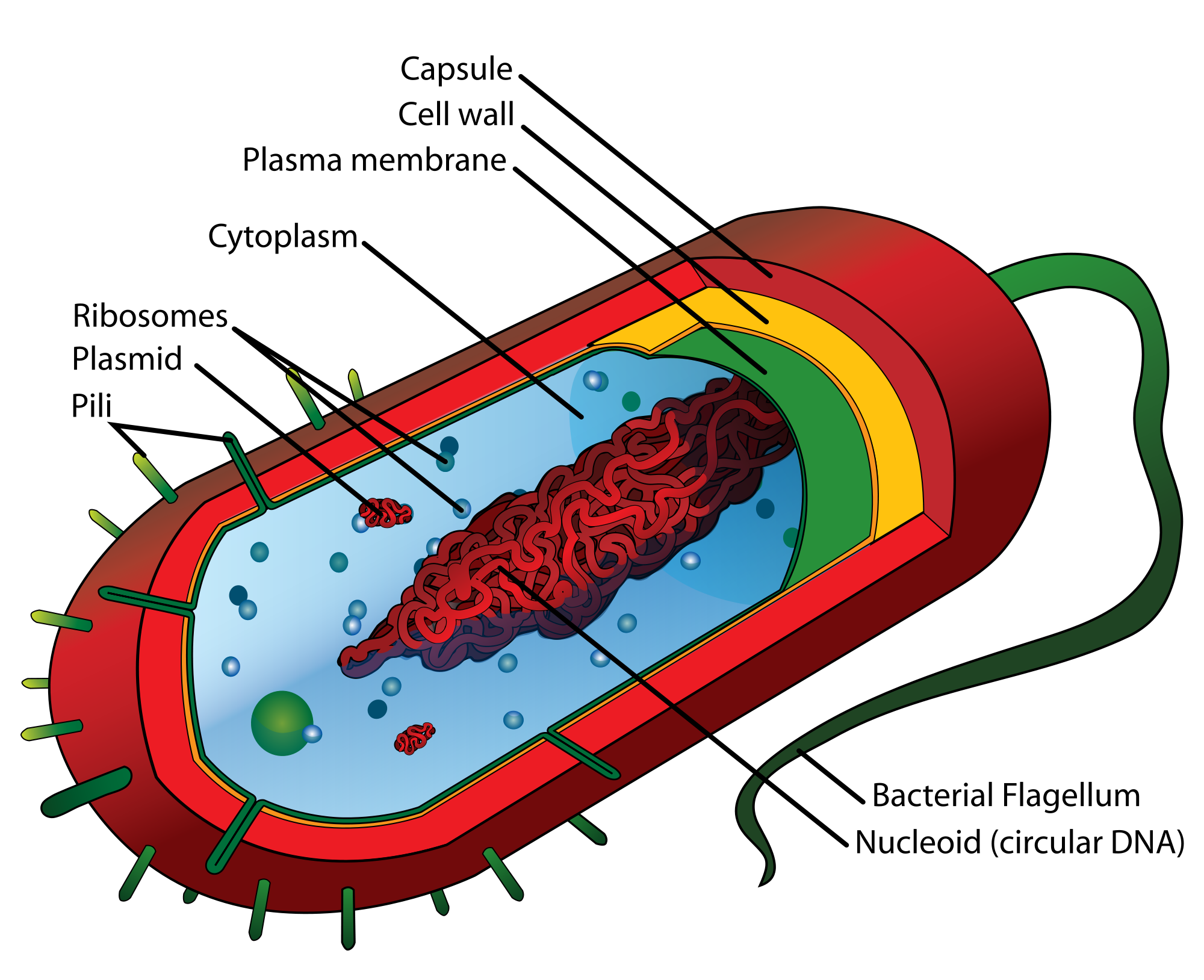

Prokaryotic Cells

Prokaryotic cells are cells without a nucleus. The DNA in prokaryotic cells is in the cytoplasm, rather than enclosed within a nuclear membrane. In addition, these cells are typically smaller than eukaryotic cells and contain fewer organelles. Prokaryotic cells are found in single-celled organisms, such as the bacterium represented by the model in Figure 4.3.3. Organisms with prokaryotic cells are called prokaryotes. They were the first type of organisms to evolve, and they are still the most common organisms today.

Eukaryotic Cells

Eukaryotic cells are cells that contain a nucleus. A typical eukaryotic cell is represented by the model in Figure 4.3.4. Eukaryotic cells are usually larger than prokaryotic cells. They are found in some single-celled and all multicellular organisms. Organisms with eukaryotic cells are called eukaryotes, and they range from fungi to humans.

Besides a nucleus, eukaryotic cells also contain other organelles. An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm that performs a specific job in the cell. Organelles called mitochondria, for example, provide energy to the cell, and organelles called vesicles store substances in the cell. Organelles allow eukaryotic cells to carry out more functions than prokaryotic cells can.

Interestingly, scientists think that mitochondria were once free-living prokaryotes that infected (or were engulfed by) larger cells. The two organisms developed a symbiotic relationship that was beneficial to both of them, resulting in the smaller prokaryote becoming an organelle within the larger cell. This is called endosymbiotic theory, and it is supported by a lot of evidence, including the fact that mitochondria have their own DNA separate from the DNA in the nucleus of the eukaryotic cell. Endosymbiotic theory will be described in more detail in later sections, and it's also discussed in the video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FGnS-Xk0ZqU

Endosymbiotic Theory, Amoeba Sisters, 2017.

4.3 Summary

- Cells must be very small so they have a large enough surface area-to-volume ratio to maintain normal cell processes.

- Cells with different functions often have different shapes.

- Prokaryotic cells do not have a nucleus. Eukaryotic cells do have a nucleus, along with other organelles.

4.3 Review Questions

- Explain why most cells are very small.

- Discuss variations in the form and function of cells.

-

-

- Do human cells have organelles? Explain your answer.

- Which are usually larger – prokaryotic or eukaryotic cells? What do you think this means for their relative ability to take in needed substances and release wastes? Discuss your answer.

- DNA in eukaryotes is enclosed within the _______ ________.

- Name three different types of cells in humans.

- Which organelle provides energy in eukaryotic cells?

- What is a function of a vesicle in a cell?

4.3 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=9i7kAt97XYU&feature=emb_logo

How we think complex cells evolved - Adam Jacobson, TED-Ed, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pxujitlv8wc

Prokaryotic vs. Eukaryotic Cells (updated), Amoeba Sisters, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 4.3.1

Borrelia_hermsii_Bacteria_(13758011613) by NAID on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.3.2

Cell Size by Christine Miller is released into the Public Domain (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/).

Figure 4.3.3

- Chondrocyte. BioTek-Wikipedia-Image by BioTek Instruments, Inc. on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license.

- Neutrophil with anthrax copy by Volker Brinkmann from PLOS Pathogens on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en) license.

- PLoSBiol4.e126.Fig6fNeuron by Lee, et al. from PLOS Biology on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en) license.

- Sperm (265 33) human by Doc. RNDr. Josef Reischig, CSc. on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 4.3.4

Model of a prokaryotic cell: bacterium by Mariana Ruiz Villarreal [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.3.5

Animal Cell adapted by Christine Miller is used under a CC0 1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en) public domain dedication license. (Original image, Animal Cell Unannotated, is by Kelvin Song on Wikimedia Commons.)

References

Amoeba Sisters. (2017, May 3). Endosymbiotic theory. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FGnS-Xk0ZqU&feature=youtu.be

Amoeba Sisters. (2018, July 30). Prokaryotic vs. eukaryotic cells (updated). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pxujitlv8wc&feature=youtu.be

Brinkmann, V. (November 2005). Neutrophil engulfing Bacillus anthracis. PLoS Pathogens 1 (3): Cover page [digital image]. DOI:10.1371. https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/issue?id=10.1371/issue.ppat.v01.i03

Lee, W.C.A., Huang, H., Feng, G., Sanes, J.R., Brown, E.N., et al. (2005, December 27) Figure 6f, slightly altered (plus scalebar, minus letter "f".) [digital image]. Dynamic Remodeling of Dendritic Arbors in GABAergic Interneurons of Adult Visual Cortex. PLoS Biology, 4(2), e29. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040029. https://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.0040029

TED-Ed. (2015, February 17). How we think complex cells evolved - Adam Jacobson. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9i7kAt97XYU&feature=youtu.be

A rigid organ that constitutes part of the vertebrate skeleton in animals.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Goose Bumps

No doubt you’ve experienced the tiny, hair-raising skin bumps called goose bumps, like those you see in Figure 10.4.1. They happen when you feel chilly. Do you know what causes goose bumps, or why they pop up when you are cold? The answers to these questions involve the layer of skin known as the dermis.

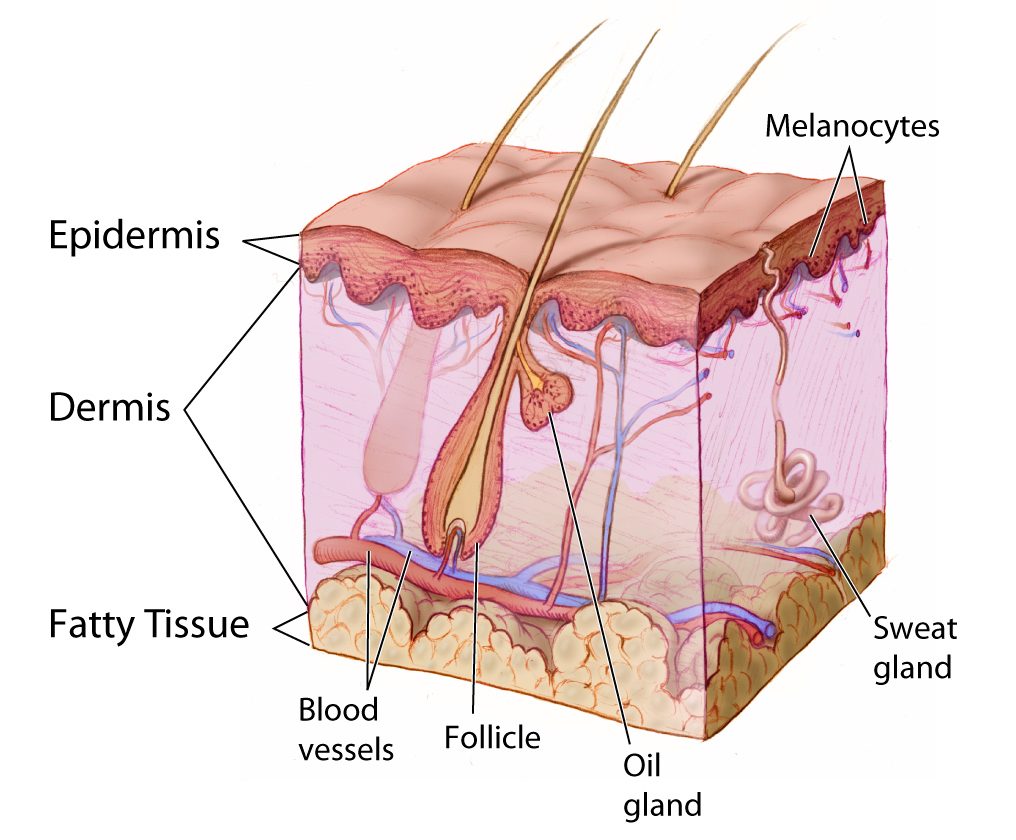

What is the Dermis?

The dermis is the inner of the two major layers that make up the skin, the outer layer being the epidermis. The dermis consists mainly of connective tissues. It also contains most skin structures, such as glands and blood vessels. The dermis is anchored to the tissues below it by flexible collagen bundles that permit most areas of the skin to move freely over subcutaneous (“below the skin”) tissues. Functions of the dermis include cushioning subcutaneous tissues, regulating body temperature, sensing the environment, and excreting wastes.

Anatomy of the Dermis

The basic anatomy of the dermis is a matrix, or sort of scaffolding, composed of connective tissues. These tissues include collagen fibres — which provide toughness — and elastin fibres, which provide elasticity. Surrounding these fibres, the matrix also includes a gel-like substance made of proteins. The tissues of the matrix give the dermis both strength and flexibility.

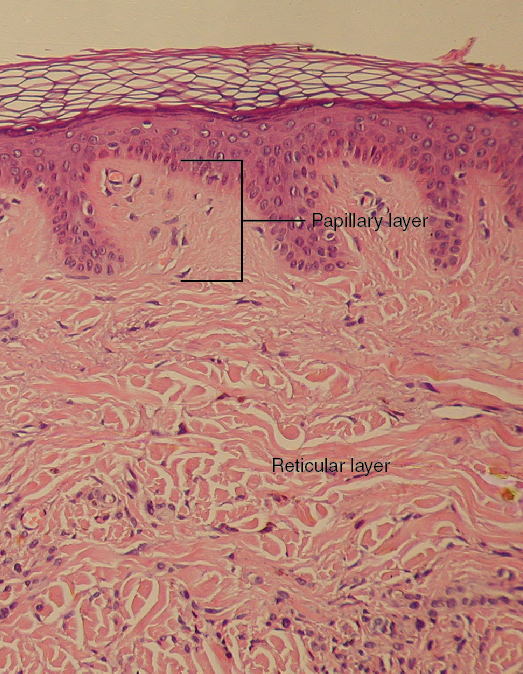

The dermis is divided into two layers: the papillary layer and the reticular layer. Both layers are shown in Figure 10.4.2 below and described in the text that follows.

Papillary Layer

The papillary layer is the upper layer of the dermis, just below the basement membrane that connects the dermis to the epidermis above it. The papillary layer is the thinner of the two dermal layers. It is composed mainly of loosely arranged collagen fibres. The papillary layer is named for its fingerlike projections — or papillae — that extend upward into the epidermis. The papillae contain capillaries and sensory touch receptors.

The papillae give the dermis a bumpy surface that interlocks with the epidermis above it, strengthening the connection between the two layers of skin. On the palms and soles, the papillae create epidermal ridges. Epidermal ridges on the fingers are commonly called fingerprints (see Figure 10.4.3). Fingerprints are genetically determined, so no two people (other than identical twins) have exactly the same fingerprint pattern. Therefore, fingerprints can be used as a means of identification, for example, at crime scenes. Fingerprints were much more commonly used forensically before DNA analysis was introduced for this purpose.

Reticular Layer

The reticular layer is the lower layer of the dermis, located below the papillary layer. It is the thicker of the two dermal layers. It is composed of densely woven collagen and elastin fibres. These protein fibres give the dermis its properties of strength and elasticity. This layer of the dermis cushions subcutaneous tissues of the body from stress and strain. The reticular layer of the dermis also contains most of the structures in the dermis, such as glands and hair follicles.

Structures in the Dermis

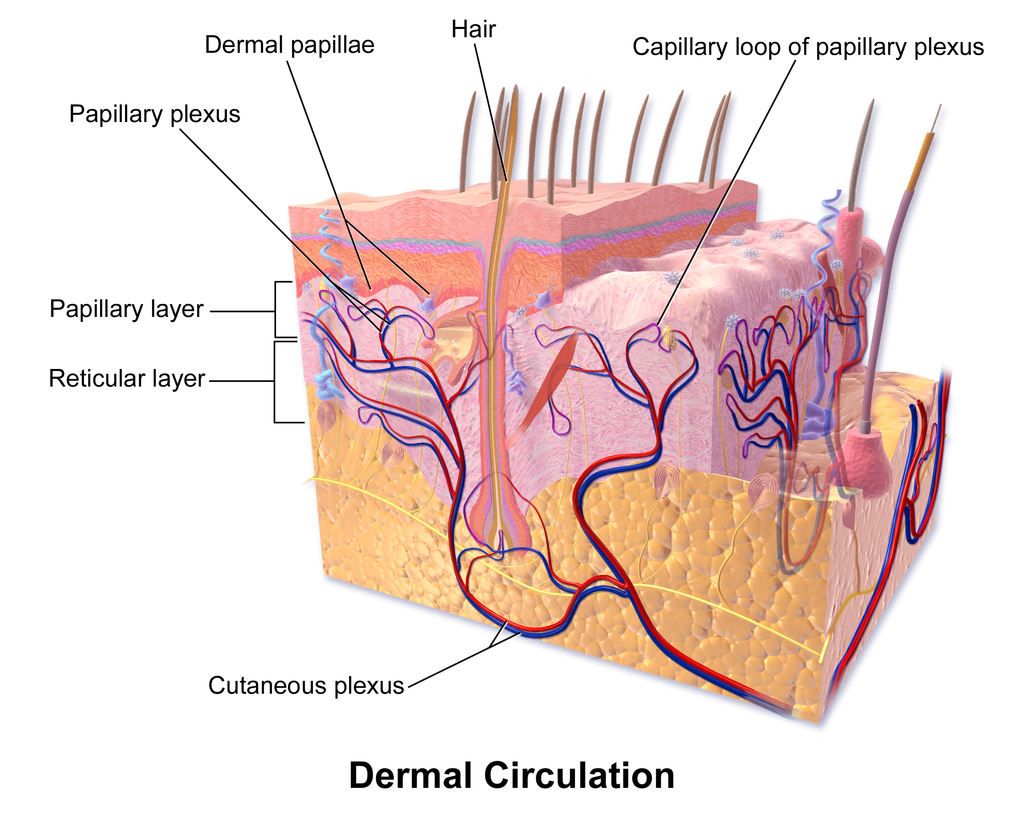

Both papillary and reticular layers of the dermis contain numerous sensory receptors, which make the skin the body’s primary sensory organ for the sense of touch. Both dermal layers also contain blood vessels. They provide nutrients to remove wastes from dermal cells, as well as cells in the lowest layer of the epidermis, the stratum basale. The circulatory components of the dermis are shown in Figure 10.4.4 below.

Glands

Glands in the reticular layer of the dermis include sweat glands and sebaceous (oil) glands. Both are exocrine glands, which are glands that release their secretions through ducts to nearby body surfaces. The diagram in Figure 10.4.5 shows these glands, as well as several other structures in the dermis.

Sweat Glands

Sweat glands produce the fluid called sweat, which contains mainly water and salts. The glands have ducts that carry the sweat to hair follicles, or to the surface of the skin. There are two different types of sweat glands: eccrine glands and apocrine glands.

- Eccrine sweat glands occur in skin all over the body. Their ducts empty through tiny openings called pores onto the skin surface. These sweat glands are involved in temperature regulation.

- Apocrine sweat glands are larger than eccrine glands, and occur only in the skin of the armpits and groin. The ducts of apocrine glands empty into hair follicles, and then the sweat travels along hairs to reach the surface. Apocrine glands are inactive until puberty, at which point they start producing an oily sweat that is consumed by bacteria living on the skin. The digestion of apocrine sweat by bacteria causes body odor.

Sebaceous Glands

Sebaceous glands are exocrine glands that produce a thick, fatty substance called sebum. Sebum is secreted into hair follicles and makes its way to the skin surface along hairs. It waterproofs the hair and skin, and helps prevent them from drying out. Sebum also has antibacterial properties, so it inhibits the growth of microorganisms on the skin. Sebaceous glands are found in every part of the skin — except for the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, where hair does not grow.

Hair Follicles

Hair follicles are the structures where hairs originate (see the diagram above). Hairs grow out of follicles, pass through the epidermis, and exit at the surface of the skin. Associated with each hair follicle is a sebaceous gland, which secretes sebum that coats and waterproofs the hair. Each follicle also has a bed of capillaries, a nerve ending, and a tiny muscle called an arrector pili.

Functions of the Dermis

The main functions of the dermis are regulating body temperature, enabling the sense of touch, and eliminating wastes from the body.

Temperature Regulation

Several structures in the reticular layer of the dermis are involved in regulating body temperature. For example, when body temperature rises, the hypothalamus of the brain sends nerve signals to sweat glands, causing them to release sweat. An adult can sweat up to four litres an hour. As the sweat evaporates from the surface of the body, it uses energy in the form of body heat, thus cooling the body. The hypothalamus also causes dilation of blood vessels in the dermis when body temperature rises. This allows more blood to flow through the skin, bringing body heat to the surface, where it can radiate into the environment.

When the body is too cool, sweat glands stop producing sweat, and blood vessels in the skin constrict, thus conserving body heat. The arrector pili muscles also contract, moving hair follicles and lifting hair shafts. This results in more air being trapped under the hairs to insulate the surface of the skin. These contractions of arrector pili muscles are the cause of goose bumps.

Sensing the Environment

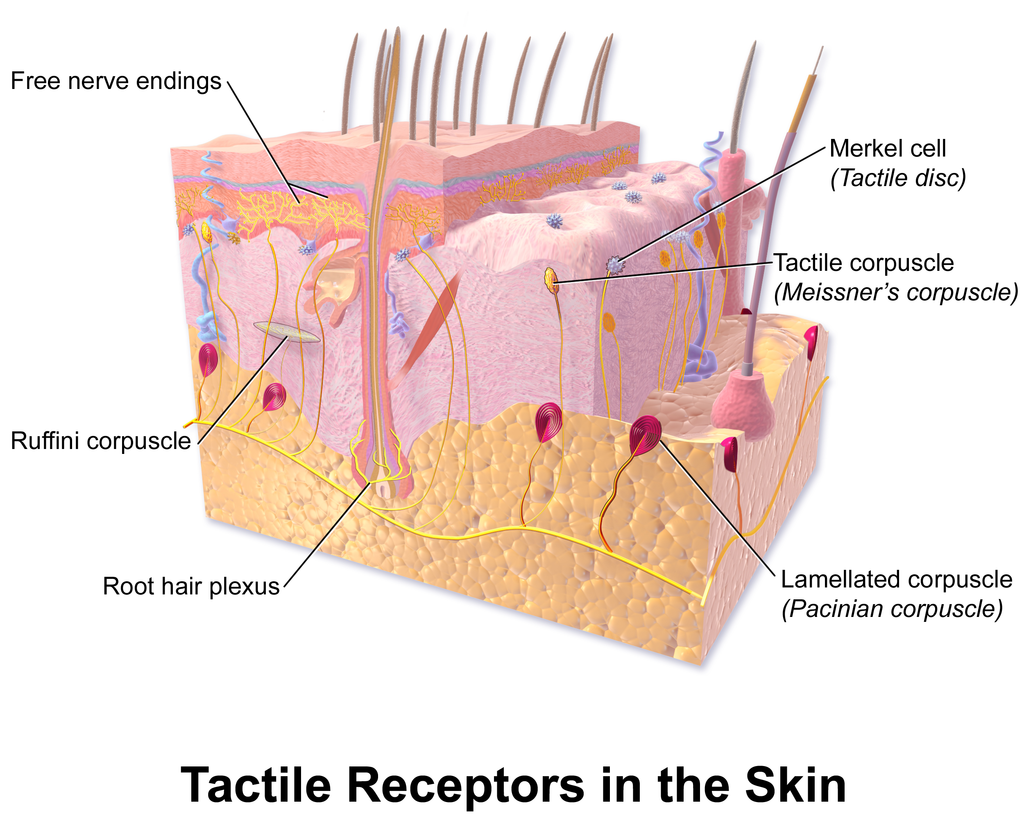

Sensory receptors in the dermis are mainly responsible for the body’s tactile senses. The receptors detect such tactile stimuli as warm or cold temperature, shape, texture, pressure, vibration, and pain. They send nerve impulses to the brain, which interprets and responds to the sensory information. Sensory receptors in the dermis can be classified on the basis of the type of touch stimulus they sense. Mechanoreceptors sense mechanical forces such as pressure, roughness, vibration, and stretching. Thermoreceptors sense variations in temperature that are above or below body temperature. Nociceptors sense painful stimuli. Figure 10.4.6 shows several specific kinds of tactile receptors in the dermis. Each kind of receptor senses one or more types of touch stimuli.

- Free nerve endings sense pain and temperature variations.

- Merkel cells sense light touch, shapes, and textures.

- Meissner’s corpuscles sense light touch.

- Pacinian corpuscles sense pressure and vibration.

- Ruffini corpuscles sense stretching and sustained pressure.

Excreting Wastes

The sweat released by eccrine sweat glands is one way the body excretes waste products. Sweat contains excess water, salts (electrolytes), and other waste products that the body must get rid of to maintain homeostasis. The most common electrolytes in sweat are sodium and chloride. Potassium, calcium, and magnesium electrolytes may be excreted in sweat, as well. When these electrolytes reach high levels in the blood, more are excreted in sweat. This helps to bring their blood levels back into balance. Besides electrolytes, sweat contains small amounts of waste products from metabolism, including ammonia and urea. Sweat may also contain alcohol in someone who has been drinking alcoholic beverages.

Feature: My Human Body

Acne is the most common skin disorder in the Canada. At least 20% of Canadians have acne at any given time and it affects approximately 90% of adolescents (as in Figure 10.4.7). Although acne occurs most commonly in teens and young adults, but it can occur at any age. Even newborn babies can get acne.

The main sign of acne is the appearance of pimples (pustules) on the skin, like those in the photo above. Other signs of acne may include whiteheads, blackheads, nodules, and other lesions. Besides the face, acne can appear on the back, chest, neck, shoulders, upper arms, and buttocks. Acne can permanently scar the skin, especially if it isn’t treated appropriately. Besides its physical effects on the skin, acne can also lead to low self-esteem and depression.

Acne is caused by clogged, sebum-filled pores that provide a perfect environment for the growth of bacteria. The bacteria cause infection, and the immune system responds with inflammation. Inflammation, in turn, causes swelling and redness, and may be associated with the formation of pus. If the inflammation goes deep into the skin, it may form an acne nodule.

Mild acne often responds well to treatment with over-the-counter (OTC) products containing benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid. Treatment with these products may take a month or two to clear up the acne. Once the skin clears, treatment generally needs to continue for some time to prevent future breakouts.

If acne fails to respond to OTC products, nodules develop, or acne is affecting self-esteem, a visit to a dermatologist is in order. A dermatologist can determine which treatment is best for a given patient. A dermatologist can also prescribe prescription medications (which are likely to be more effective than OTC products) and provide other medical treatments, such as laser light therapies or chemical peels.

What can you do to maintain healthy skin and prevent or reduce acne? Dermatologists recommend the following tips:

- Wash affected or acne-prone skin (such as the face) twice a day, and after sweating.

- Use your fingertips to apply a gentle, non-abrasive cleanser. Avoid scrubbing, which can make acne worse.

- Use only alcohol-free products and avoid any products that irritate the skin, such as harsh astringents or exfoliants.

- Rinse with lukewarm water, and avoid using very hot or cold water.

- Shampoo your hair regularly.

- Do not pick, pop, or squeeze acne. If you do, it will take longer to heal and is more likely to scar.

- Keep your hands off your face. Avoid touching your skin throughout the day.

- Stay out of the sun and tanning beds. Some acne medications make your skin very sensitive to UV light.

10.4 Summary

- The dermis is the inner and thicker of the two major layers that make up the skin. It consists mainly of a matrix of connective tissues that provide strength and stretch. It also contains almost all skin structures, including sensory receptors and blood vessels.

- The dermis has two layers. The upper papillary layer has papillae extending upward into the epidermis and loose connective tissues. The lower reticular layer has denser connective tissues and structures, such as glands and hair follicles. Glands in the dermis include eccrine and apocrine sweat glands and sebaceous glands. Hair follicles are structures where hairs originate.

- Functions of the dermis include cushioning subcutaneous tissues, regulating body temperature, sensing the environment, and excreting wastes. The dense connective tissues of the dermis provide cushioning. The dermis regulates body temperature mainly by sweating and by vasodilation or vasoconstriction. The many tactile sensory receptors in the dermis make it the main organ for the sense of touch. Wastes excreted in sweat include excess water, electrolytes, and certain metabolic wastes.

10.4 Review Questions

- What is the dermis?

- Describe the basic anatomy of the dermis.

- Compare and contrast the papillary and reticular layers of the dermis.

- What causes epidermal ridges, and why can they be used to identify individuals?

- Name the two types of sweat glands in the dermis, and explain how they differ.

- What is the function of sebaceous glands?

- Describe the structures associated with hair follicles.

- Explain how the dermis helps regulate body temperature.

- Identify three specific kinds of tactile receptors in the dermis, along with the type of stimuli they sense.

- How does the dermis excrete wastes? What waste products does it excrete?

- What are subcutaneous tissues? Which layer of the dermis provides cushioning for subcutaneous tissues? Why does this layer provide most of the cushioning, instead of the other layer?

- For each of the functions listed below, describe which structure within the dermis carries it out.

- Brings nutrients to and removes wastes from dermal and lower epidermal cells

- Causes hairs to move

- Detects painful stimuli on the skin

10.4 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FX-FwK0IIrE

How do you get rid of acne? SciShow, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcHQWMAClhQ&feature=emb_logo

When You Can't Scratch Away An Itch, Seeker, 2013.

Attributions

Figure 10.4.1

Goose_bumps by EverJean on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 10.4.2

Layers_of_the_Dermis by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 10.4.3

Fingerprint_detail_on_male_finger_in_Třebíč,_Třebíč_District by Frettie on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 10.4.4

Blausen_0802_Skin_Dermal Circulation by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 10.4.5

Anatomy_The_Skin_-_NCI_Visuals_Online by Don Bliss (artist) / National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health, with the ID 4604) is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 10.4.6

Blausen_0809_Skin_TactileReceptors by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 10.4.7

Akne-jugend by Ellywa on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain). (No machine-readable author provided. Ellywa assumed, based on copyright claims).

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 5.7 Layers of the dermis [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 5.1 Layers of the skin). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-1-layers-of-the-skin

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

SciShow. (2016, October 26). How do you get rid of acne? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FX-FwK0IIrE

Seeker. (2013, October 26). When you can't scratch away an itch. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VcHQWMAClhQ&feature=emb_logo