9.2 Introduction to the Endocrine System

Your body the chemist

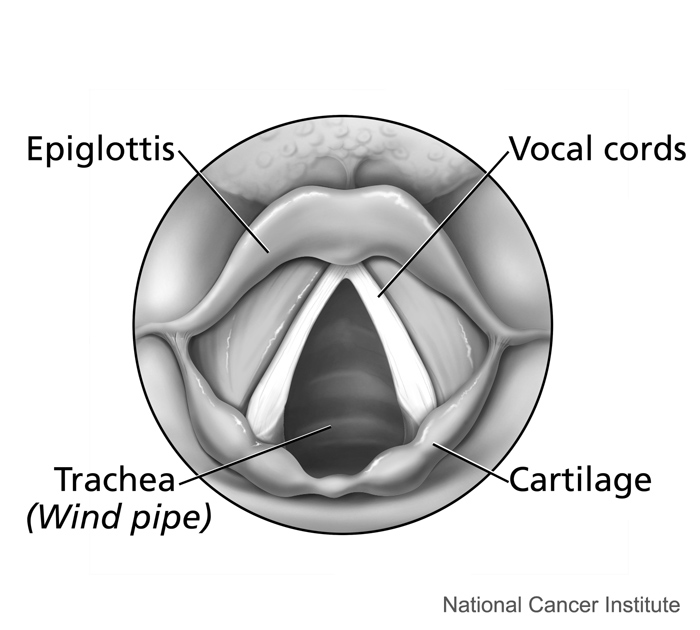

Your endocrine system is constantly making hormones that will regulate every body system that makes up you! The endocrine system is an adept chemist; by making a chain of modifications to the steroid cortisol, your body can make a whole host of other hormones at a moment’s notice.

Overview of the Endocrine System

The endocrine system is a system of glands called endocrine glands that release chemical messenger molecules into the bloodstream. The messenger molecules of the endocrine system are called endocrine hormones. Other glands of the body, including sweat glands and salivary glands, also secrete substances, but not into the bloodstream. Instead, they secrete them through ducts that carry them to nearby body surfaces. These other glands are not part of the endocrine system. Instead, they are called exocrine glands.

Endocrine hormones act slowly compared with the rapid transmission of electrical messages in the nervous system. Endocrine hormones must travel through the bloodstream to the cells they affect, and this takes time. On the other hand, because endocrine hormones are released into the bloodstream, they travel throughout the body wherever blood flows. As a result, endocrine hormones may affect many cells and have body-wide effects. The effects of endocrine hormones are also longer lasting than the effects of nervous system messages. Endocrine hormones may cause effects that last for days, weeks, or even months.

Glands of the Endocrine System

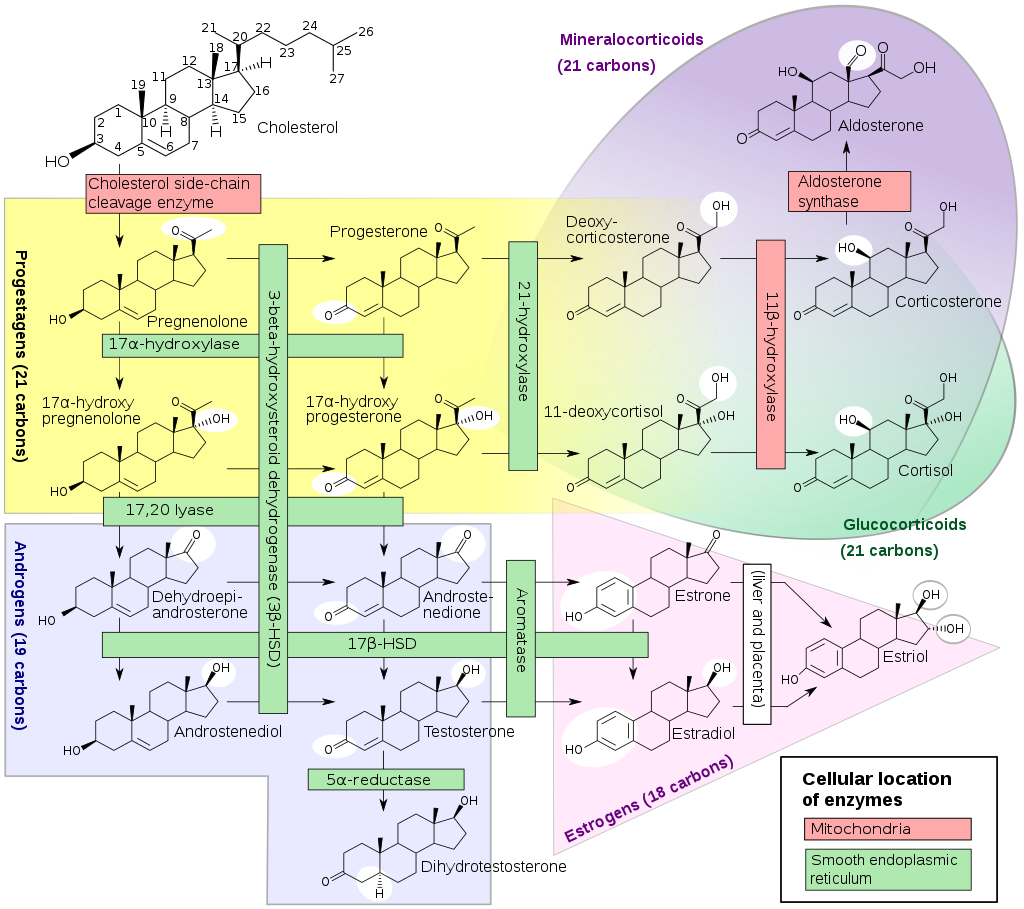

The major glands of the endocrine system are shown in Figure 9.2.2. The glands in the figure are described briefly in the rest of this section. Refer to the figure as you read about the glands in the following text.

All of the glands labelled in Figure 9.2.2 are part of the endocrine system. Note that the ovary and testis are the only endocrine glands that differ in males and females.

Pituitary Gland

The pituitary gland is located at the base of the brain. It is controlled by the nervous system via the brain structure called the hypothalamus, to which it is connected by a thin stalk. The pituitary gland consists of two lobes, called the anterior (front) lobe and posterior (back) lobe. The posterior lobe stores and secretes hormones synthesized by the hypothalamus. The anterior lobe synthesizes and secretes its own endocrine hormones, also under the influence of the hypothalamus. One endocrine hormone secreted by the pituitary gland is growth hormone, which stimulates cells throughout the body to synthesize proteins and divide. Most of the other endocrine hormones secreted by the pituitary gland control other endocrine glands. Generally, these hormones direct the other glands to secrete either more or less of their hormones, which is why the pituitary gland is often referred to as the “master gland” of the endocrine system.

Remaining Glands of the Endocrine System

Each of the other glands of the endocrine system is summarized below. Several of these endocrine glands are also discussed in greater detail in other concepts in this chapter.

- The thyroid gland is a large gland in the neck. Thyroid hormones (such as thyroxine) increase the rate of metabolism in cells throughout the body. They control how quickly cells use energy and make proteins.

- The four parathyroid glands are located in the neck behind the thyroid gland. Parathyroid hormone helps keep the level of calcium in the blood within a narrow range. It stimulates bone cells to dissolve calcium and release it into the blood.

- The pineal gland is a tiny gland located near the center of the brain. It secretes the hormone melatonin, which controls the sleep-wake cycle and several other processes. The production of melatonin is stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light. Cells in the retina of the eye detect light and send signals to a structure in the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). Nerve fibres carry the signals from the SCN to the pineal gland via the autonomic nervous system.

- The pancreas is located near the stomach. Its endocrine hormones include insulin and glucagon, which work together to control the level of glucose in the blood. The pancreas also secretes digestive enzymes into the small intestine.

- The two adrenal glands are located above the kidneys. Adrenal glands secrete several different endocrine hormones, including the hormone adrenaline, which is involved in the fight-or-flight response. Other endocrine hormones secreted by the adrenal glands have a variety of functions. The hormone aldosterone, for example, helps regulate the balance of minerals in the body. The hormone cortisol is also an adrenal gland hormone.

- The gonads include the ovaries in females and the testes in males. They secrete sex hormones, including testosterone (in males) and estrogen and progesterone (in females). These hormones control sexual maturation during puberty and the production of gametes (sperm or egg cells) by the gonads after sexual maturation.

- The thymus gland is located in front of the heart. It is the site where immune system cells, called T cells, mature. T cells are critical to the adaptive immune system, in which the body adapts to specific pathogens.

Endocrine System Disorders

Diseases of the endocrine system are relatively common. An endocrine system disease usually involves the secretion of too much or not enough of a hormone. When too much hormone is secreted, the condition is called hypersecretion. When not enough hormone is secreted, the condition is called hyposecretion.

Hypersecretion and Hyposecretion

Hypersecretion by an endocrine gland is often caused by a tumor. A tumor of the pituitary gland, for example, can cause hypersecretion of growth hormone. If this occurs during childhood and goes untreated, it results in very long arms and legs, and an abnormally tall stature by adulthood (see Figure 9.2.3). This condition is commonly known as gigantism.

Hyposecretion by an endocrine gland is often caused by destruction of the hormone-secreting cells of the gland. As a result, not enough of the hormone is secreted. An example of this is type 1 diabetes, in which the body’s own immune system attacks and destroys cells of the pancreas that secrete insulin. This type of diabetes is generally treated with frequent injections of insulin.

Hormone Resistance

In some cases, an endocrine gland secretes a normal amount of hormone, but target cells do not respond normally to it. This may occur because target cells have become resistant to the hormone. An example of this type of endocrine disorder is type 2 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, body cells do not respond to normal amounts of insulin. As a result, cells do not take up glucose from the blood, leading to high blood glucose levels. Insulin may or may not be needed to treat type 2 diabetes. Instead, it may be treated with lifestyle changes and non-insulin medications.

9.2 Summary

- The endocrine system is a system of glands that release chemical messenger molecules called hormones into the bloodstream. Other glands, called exocrine glands, release substances onto nearby body surfaces through ducts. Endocrine hormones travel more slowly than nerve impulses, which are the body’s other way of sending messages. The effects of endocrine hormones, however, may be much longer lasting.

- The pituitary gland is the master gland of the endocrine system. Most of the hormones it produces control other endocrine glands. These glands include the thyroid gland, parathyroid glands, pineal gland, pancreas, adrenal glands, gonads (testes and ovaries), and thymus gland.

- Diseases of the endocrine system are relatively common. An endocrine disease usually involves hypersecretion or hyposecretion of a hormone. Hypersecretion is frequently caused by a tumor. Hyposecretion is often caused by destruction of hormone-secreting cells by the body’s own immune system.

9.2 Review Questions

- What is the endocrine system? What is its general function?

-

-

- Describe the role of the pituitary gland in the endocrine system.

- List three endocrine glands other than the pituitary gland. Identify their functions.

- Which endocrine gland has an important function in the immune system? What is that function?

- Name an endocrine disorder in which too much of a hormone is produced.

- What are two reasons people with diabetes might have signs and symptoms of inadequate insulin?

- Besides location, what is the main difference between the anterior lobe of the pituitary and the posterior lobe of the pituitary?

9.2 Explore More

How do your hormones work? – Emma Bryce, TED-Ed, 2018.

What is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), Bijniervereniging NVACP, 2014.

Cynthia Kenyon: Experiments that hint of longer lives, TED, 2011.

Attributions

Figure 9.2.1

Steroidogenesis.svg by David Richfield (User:Slashme) and Mikael Häggström on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) [Derived from previous version by Hoffmeier and Settersr]

Figure 9.2.2

1801_The_Endocrine_System by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 9.2.3

MartinVanBurenBates by unknown on Wikimedia Commons is believed to be in the public domain.

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 17.2 Endocrine system [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 17.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/17-1-an-overview-of-the-endocrine-system

Bijniervereniging NVACP. (2014, October 11). What is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH)? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-gNj5KoWLhE&feature=youtu.be

Häggström M, Richfield D (2014). Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (1). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 20024436 [Derived from previous version by Hoffmeier and Settersr]

TED. (2011, November 17). Cynthia Kenyon: Experiments that hint of longer lives. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V48M5j-6zdE&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, June 21). How do your hormones work? – Emma Bryce. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SPRPkLoKp8&feature=youtu.be

The body system which acts as a chemical messenger system comprising feedback loops of the hormones released by internal glands of an organism directly into the circulatory system, regulating distant target organs. In humans, the major endocrine glands are the thyroid gland and the adrenal glands.

Gland such as a sweat gland, salivary gland, or mammary gland that secretes a substance into a duct that carries the secretion to the outside of the body.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Giving the Gift of Life

Did you ever donate blood? If you did, then you probably know that your blood type is an important factor in blood transfusions. People vary in the type of blood they inherit, and this determines which type(s) of blood they can safely receive in a transfusion. Do you know your blood type?

What Are Blood Types?

Blood is composed of cells suspended in a liquid called plasma. There are three types of cells in blood: red blood cells, which carry oxygen; white blood cells, which fight infections and other threats; and platelets, which are cell fragments that help blood clot. Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of certain molecules, called antigens, on the surface of red blood cells. These molecules may help maintain the integrity of the cell membrane, act as receptors, or have other biological functions. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens. Human blood group systems include the well-known ABO and Rhesus (Rh) systems, as well as at least 33 others that are less well known.

Antigens and Antibodies

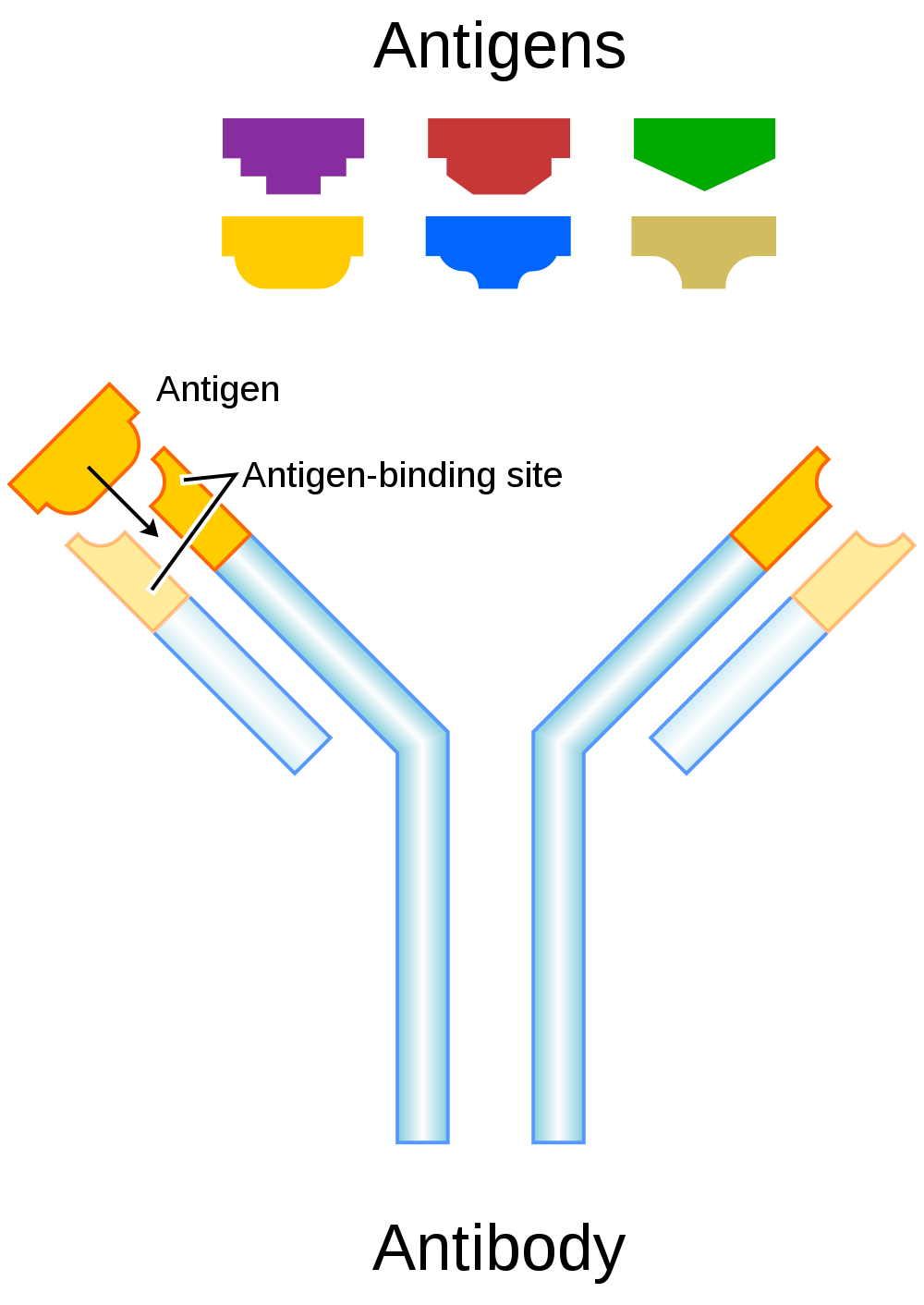

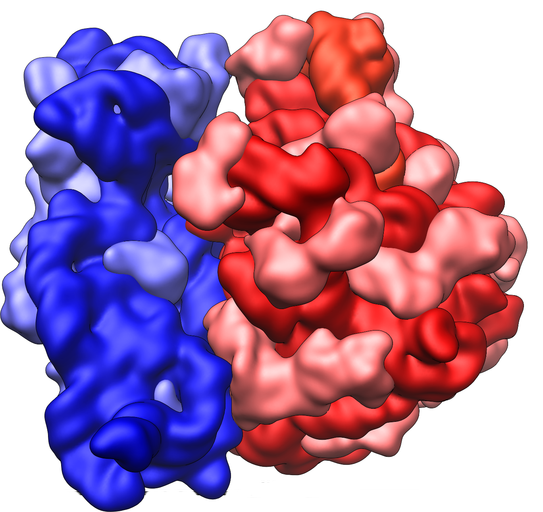

Antigens — such as those on the red blood cells — are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self (produced by your own body) or non-self (not produced by your own body). Blood group antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycoproteins (proteins attached to chains of sugars), or glycolipids (lipids attached to chains of sugars), depending on the particular blood group system. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens. Antibodies are large, Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system that recognize and bind to non-self antigens. The analogy of a lock and key is often used to represent how an antibody and antigen fit together, as shown in the illustration below (Figure 6.5.2). When antibodies bind to antigens, it marks them for destruction by other immune system cells. Non-self antigens may enter your body on pathogens (such as bacteria or viruses), on foods, or on red blood cells in a blood transfusion from someone with a different blood type than your own. The last way is virtually impossible nowadays because of effective blood typing and screening protocols.

Genetics of Blood Type

An individual’s blood type depends on which alleles for a blood group system were inherited from their parents. Generally, blood type is controlled by alleles for a single gene, or for two or more very closely linked genes. Closely linked genes are almost always inherited together, because there is little or no recombination between them. Like other genetic traits, a person’s blood type is generally fixed for life, but there are rare instances in which blood type can change. This could happen, for example, if an individual receives a bone marrow transplant to treat a disease, such as leukemia. If the bone marrow comes from a donor who has a different blood type, the patient’s blood type may eventually convert to the donor’s blood type, because red blood cells are produced in bone marrow.

ABO Blood Group System

The ABO blood group system is the best known human blood group system. Antigens in this system are glycoproteins. These antigens are shown in the list below. There are four common blood types for the ABO system:

- Type A, in which only the A antigen is present.

- Type B, in which only the B antigen is present.

- Type AB, in which both the A and B antigens are present.

- Type O, in which neither the A nor the B antigen is present.

Genetics of the ABO System

The ABO blood group system is controlled by a single gene on chromosome 9. There are three common alleles for the gene, often represented by the letters A , B , and O. With three alleles, there are six possible genotypes for ABO blood group. Alleles A and B, however, are both dominant to allele O and codominant to each other. This results in just four possible phenotypes (blood types) for the ABO system. These genotypes and phenotypes are shown in Table 6.5.1.

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes

| ABO Blood Group System | |

| Genotype | Phenotype (Blood Type, or Group) |

| AA | A |

| AO | A |

| BB | B |

| BO | B |

| OO | O |

| AB | AB |

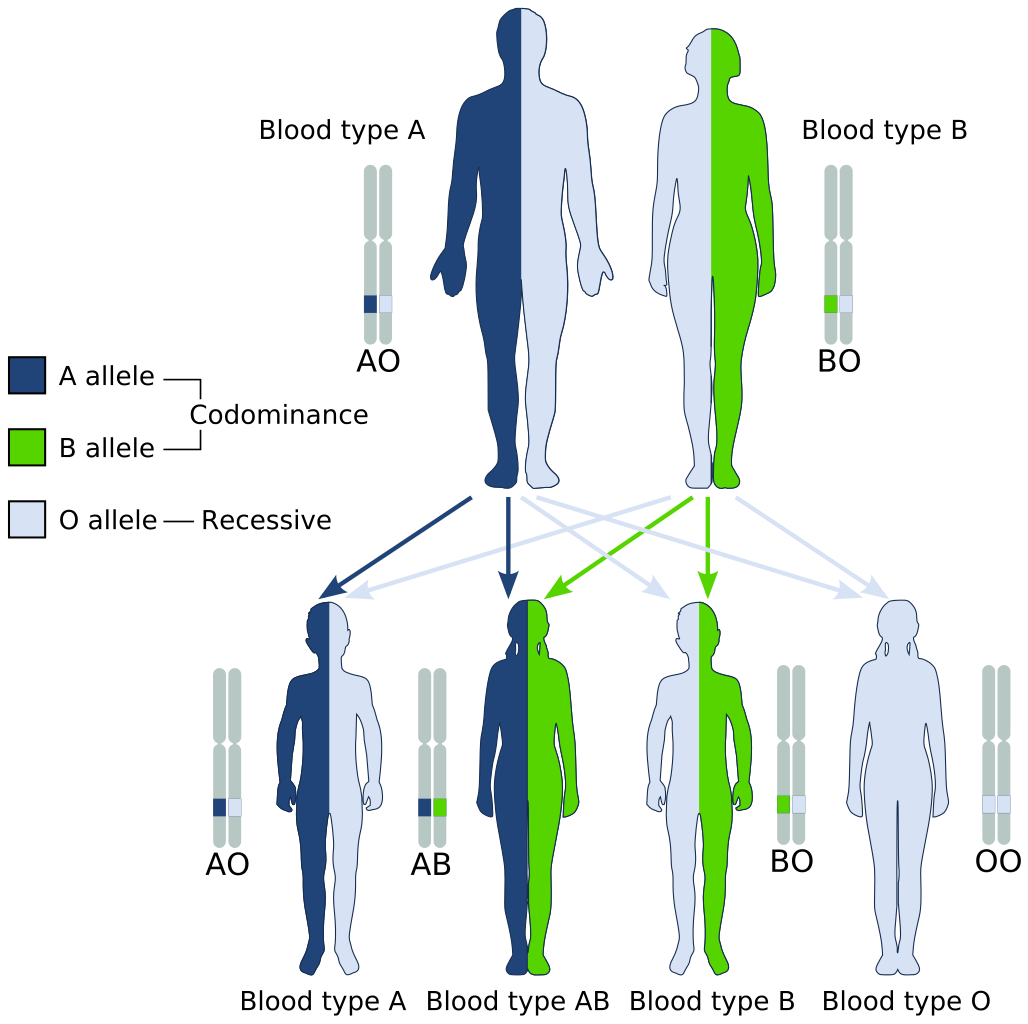

The diagram below (Figure 6.5.3) shows an example of how ABO blood type is inherited. In this particular example, the father has blood type A (genotype AO) and the mother has blood type B (genotype BO). This mating type can produce children with each of the four possible ABO phenotypes, although in any given family, not all phenotypes may be present in the children.

Medical Significance of ABO Blood Type

The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. If red blood cells containing a particular ABO antigen are transfused into a person who lacks that antigen, the person’s immune system will recognize the antigen on the red blood cells as non-self. Antibodies specific to that antigen will attack the red blood cells, causing them to agglutinate (or clump) and break apart. If a unit of incompatible blood were to be accidentally transfused into a patient, a severe reaction (called acute hemolytic transfusion reaction) is likely to occur, in which many red blood cells are destroyed. This may result in kidney failure, shock, and even death. Fortunately, such medical accidents virtually never occur today.

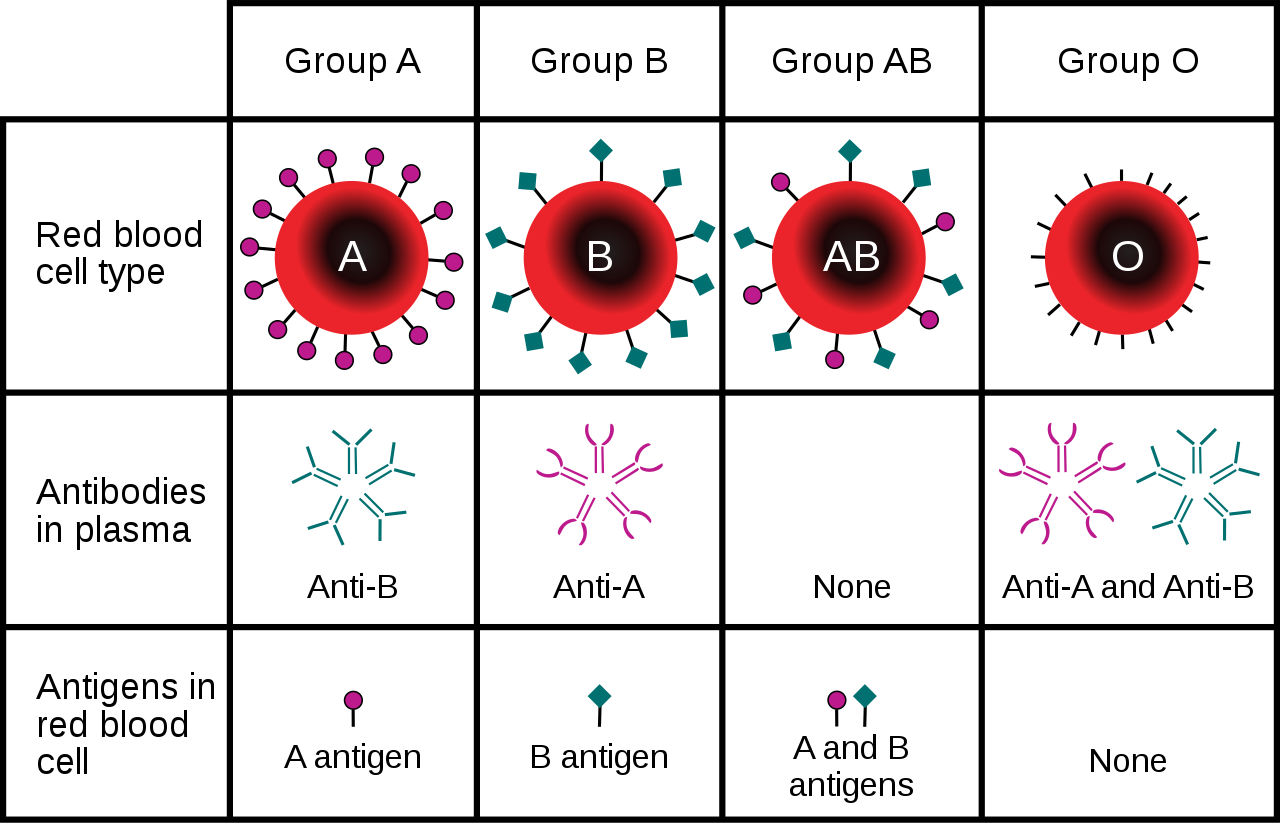

These antibodies are often spontaneously produced in the first years of life, after exposure to common microorganisms in the environment that have antigens similar to blood antigens. Specifically, a person with type A blood will produce anti-B antibodies, while a person with type B blood will produce anti-A antibodies. A person with type AB blood does not produce either antibody, while a person with type O blood produces both anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Once the antibodies have been produced, they circulate in the plasma. The relationship between ABO red blood cell antigens and plasma antibodies is shown in Figure 6.5.4.

The antibodies that circulate in the plasma are for different antigens than those on red blood cells, which are recognized as self antigens.

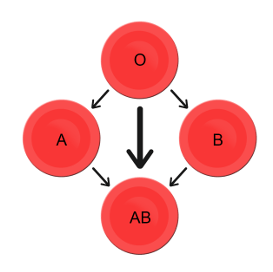

Which blood types are compatible and which are not? Type O blood contains both anti-A and anti-B antibodies, so people with type O blood can only receive type O blood. However, they can donate blood to people of any ABO blood type, which is why individuals with type O blood are called universal donors. Type AB blood contains neither anti-A nor anti-B antibodies, so people with type AB blood can receive blood from people of any ABO blood type. That’s why individuals with type AB blood are called universal recipients. They can donate blood, however, only to people who also have type AB blood. These and other relationships between blood types of donors and recipients are summarized in the simple diagram to the right.

Geographic Distribution of ABO Blood Groups

The frequencies of blood groups for the ABO system vary around the world. You can see how the A and B alleles and the blood group O are distributed geographically on the maps in Figure 6.5.6.

- Worldwide, B is the rarest ABO allele, so type B blood is the least common ABO blood type. Only about 16 per cent of all people have the B allele. Its highest frequency is in Asia. Its lowest frequency is among the indigenous people of Australia and the Americas.

- The A allele is somewhat more common around the world than the B allele, so type A blood is also more common than type B blood. The highest frequencies of the A allele are in Australian Aborigines, the Lapps (Sami) of Northern Scandinavia, and Blackfoot Native Americans in North America. The allele is nearly absent among Native Americans in Central and South America.

- The O allele is the most common ABO allele around the world, and type O blood is the most common ABO blood type. Almost two-thirds of people have at least one copy of the O allele. It is especially common in Native Americans in Central and South America, where it reaches frequencies close to 100 per cent. It also has relatively high frequencies in Australian Aborigines and Western Europeans. Its frequencies are lowest in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Figure 6.5.6 Maps of populations that have the A, B and O alleles.

Evolution of the ABO Blood Group System

The geographic distribution of ABO blood type alleles provides indirect evidence for the evolutionary history of these alleles. Evolutionary biologists hypothesize that the allele for blood type A evolved first, followed by the allele for blood type O, and then by the allele for blood type B. This chronology accounts for the percentages of people worldwide with each blood group, and is also consistent with known patterns of early population movements.

The evolutionary forces of founder effect and genetic drift have no doubt played a significant role in the current distribution of ABO blood types worldwide. Geographic variation in ABO blood groups is also likely to be influenced by natural selection, because different blood types are thought to vary in their susceptibility to certain diseases. For example:

- People with type O blood may be more susceptible to cholera and plague. They are also more likely to develop gastrointestinal ulcers.

- People with type A blood may be more susceptible to smallpox and more likely to develop certain cancers.

- People with types A, B, and AB blood appear to be less likely to form blood clots that can cause strokes. However, early in our history, the ability of blood to form clots — which appears greater in people with type O blood — may have been a survival advantage.

- Perhaps the greatest natural selective force associated with ABO blood types is malaria. There is considerable evidence to suggest that people with type O blood are somewhat resistant to malaria, giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

Rhesus Blood Group System

Another well-known blood group system is the Rhesus (Rh) blood group system. The Rhesus system has dozens of different antigens, but only five main antigens (called D, C, c, E, and e). The major Rhesus antigen is the D antigen. People with the D antigen are called Rh positive (Rh+), and people who lack the D antigen are called Rh negative (Rh-). Rhesus antigens are thought to play a role in transporting ions across cell membranes by acting as channel proteins.

The Rhesus blood group system is controlled by two linked genes on chromosome 1. One gene, called RHD, produces a single antigen, antigen D. The other gene, called RHCE, produces the other four relatively common Rhesus antigens (C, c, E, and e), depending on which alleles for this gene are inherited.

Rhesus Blood Group and Transfusions

After the ABO system, the Rhesus system is the second most important blood group system in blood transfusions. The D antigen is the one most likely to provoke an immune response in people who lack the antigen. People who have the D antigen (Rh+) can be safely transfused with either Rh+ or Rh- blood, whereas people who lack the D antigen (Rh-) can be safely transfused only with Rh- blood.

Unlike anti-A and anti-B antibodies to ABO antigens, anti-D antibodies for the Rhesus system are not usually produced by sensitization to environmental substances. People who lack the D antigen (Rh-), however, may produce anti-D antibodies if exposed to Rh+ blood. This may happen accidentally in a blood transfusion, although this is extremely unlikely today. It may also happen during pregnancy with an Rh+ fetus if some of the fetal blood cells pass into the mother’s blood circulation.

Hemolytic Disease of the Newborn

If a woman who is Rh- is carrying an Rh+ fetus, the fetus may be at risk. This is especially likely if the mother has formed anti-D antibodies during a prior pregnancy because of a mixing of maternal and fetal blood during childbirth. Unlike antibodies against ABO antigens, antibodies against the Rhesus D antigen can cross the placenta and enter the blood of the fetus. This may cause hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN), also called erythroblastosis fetalis, an illness in which fetal red blood cells are destroyed by maternal antibodies, causing anemia. This illness may range from mild to severe. If it is severe, it may cause brain damage and is sometimes fatal for the fetus or newborn. Fortunately, HDN can be prevented by preventing the formation of anti-D antibodies in the Rh- mother. This is achieved by injecting the mother with a medication called Rho(D) immune globulin.

Geographic Distribution of Rhesus Blood Types

The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system, as there is with the ABO system. The aboriginal inhabitants of the Americas and Australia originally had very close to 100 per cent Rh+ blood. The frequency of the Rh+ blood type is also very high in African populations, at about 97 to 99 per cent. In East Asia, the frequency of Rh+ is slightly lower, at about 93 to 99 per cent. Europeans have the lowest frequency of the Rh+ blood type at about 83 to 85 per cent.

What explains the population variation in Rhesus blood types? Prior to the advent of modern medicine, Rh+ positive children conceived by Rh- women were at risk of fetal or newborn death or impairment from HDN. This was an enigma, because presumably, natural selection would work to remove the rarer phenotype (Rh-) from populations. However, the frequency of this phenotype is relatively high in many populations.

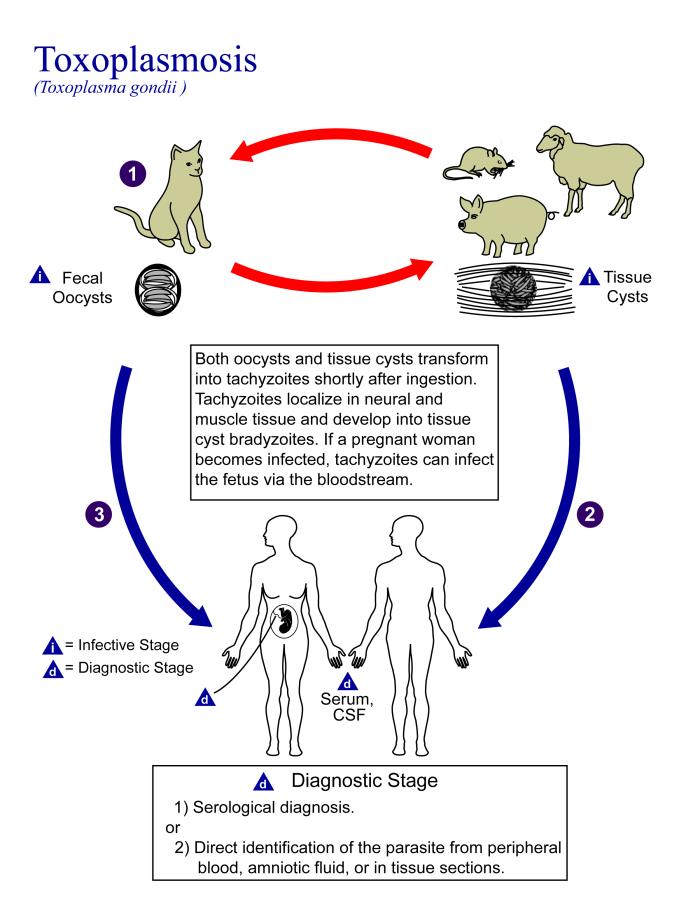

Recent studies have found evidence that natural selection may actually favor heterozygotes for the Rhesus D antigen. The selective agent in this case is thought to be toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan Toxoplasma gondii, which is very common worldwide. You can see a life cycle diagram of the parasite in Figure 6.5.7. Infection by this parasite often causes no symptoms at all, or it may cause flu-like symptoms for a few days or weeks. Exposure to the parasite has been linked, however, to increased risk of mental disorders (such as schizophrenia), neurological disorders (such as Alzheimer’s), and other neurological problems, including delayed reaction times. One study found that people who tested positive for antibodies to the parasite were more than twice as likely to be involved in traffic accidents.

People who are heterozygous for the D antigen appear less likely to develop the negative neurological and mental effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection. This could help explain why both phenotypes (Rh+ and Rh-) are maintained in most populations. There are also striking geographic differences in the prevalence of toxoplasmosis worldwide, ranging from zero to 95 per cent in different regions. This could explain geographic variation in the D antigen worldwide, because its strength as a selective agent would vary with its prevalence.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Myth |

Reality |

| "Your nutritional needs can be determined by your ABO blood type. Knowing your blood type allows you to choose the appropriate foods that will help you lose weight, increase your energy, and live a longer, healthier life." | This idea was proposed in 1996 in a New York Times bestseller Eat Right for Your Type, by Peter D’Adamo, a naturopath. Naturopathy is a method of treating disorders that involves the use of herbs, sunlight, fresh air, and other natural substances. Some medical doctors consider naturopathy a pseudoscience. A major scientific review of the blood type diet could find no evidence to support it. In one study, adults eating the diet designed for blood type A showed improved health — but this occurred in everyone, regardless of their blood type. Because the blood type diet is based solely on blood type, it fails to account for other factors that might require dietary adjustments or restrictions. For example, people with diabetes — but different blood types — would follow different diets, and one or both of the diets might conflict with standard diabetes dietary recommendations and be dangerous. |

| "ABO blood type is associated with certain personality traits. People with blood type A, for example, are patient and responsible, but may also be stubborn and tense, whereas people with blood type B are energetic and creative, but may also be irresponsible and unforgiving. In selecting a spouse, both your own and your potential mate’s blood type should be taken into account to ensure compatibility of your personalities." | The belief that blood type is correlated with personality is widely held in Japan and other East Asian countries. The idea was originally introduced in the 1920s in a study commissioned by the Japanese government, but it was later shown to have no scientific support. The idea was revived in the 1970s by a Japanese broadcaster, who wrote popular books about it. There is no scientific basis for the idea, and it is generally dismissed as pseudoscience by the scientific community. Nonetheless, it remains popular in East Asian countries, just as astrology is popular in many other countries. |

6.5 Summary

- Blood type (or blood group) is a genetic characteristic associated with the presence or absence of antigens on the surface of red blood cells. A blood group system refers to all of the gene(s), alleles, and possible genotypes and phenotypes that exist for a particular set of blood type antigens.

- Antigens are molecules that the immune system identifies as either self or non-self. If antigens are identified as non-self, the immune system responds by forming antibodies that are specific to the non-self antigens, leading to the destruction of cells bearing the antigens.

- The ABO blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by a single gene with three common alleles on chromosome 9. There are four possible ABO blood types: A, B, AB, and O. The ABO system is the most important blood group system in blood transfusions. People with type O blood are universal donors, and people with type AB blood are universal recipients.

- The frequencies of ABO blood type alleles and blood groups vary around the world. The allele for the B antigen is least common, and blood type O is the most common. The evolutionary forces of founder effect, genetic drift, and natural selection are responsible for the geographic distribution of ABO alleles and blood types. People with type O blood, for example, may be somewhat resistant to malaria, possibly giving them a selective advantage where malaria is endemic.

- The Rhesus blood group system is a system of red blood cell antigens controlled by two genes with many alleles on chromosome 1. There are five common Rhesus antigens, of which antigen D is most significant. Individuals who have antigen D are called Rh+, and individuals who lack antigen D are called Rh-. Rh- mothers of Rh+ fetuses may produce antibodies against the D antigen in the fetal blood, causing hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN).

- The majority of people worldwide are Rh+, but there is regional variation in this blood group system. This variation may be explained by natural selection that favors heterozygotes for the D antigen, because this genotype seems to be protected against some of the neurological consequences of the common parasitic infection toxoplasmosis.

6.5 Review Questions

- Define blood type and blood group system.

- Explain the relationship between antigens and antibodies.

- Identify the alleles, genotypes, and phenotypes in the ABO blood group system.

- Discuss the medical significance of the ABO blood group system.

- Compare the relative worldwide frequencies of the three ABO alleles.

- Give examples of how different ABO blood types vary in their susceptibility to diseases.

- Describe the Rhesus blood group system.

- Relate Rhesus blood groups to blood transfusions.

- What causes hemolytic disease of the newborn?

- Describe how toxoplasmosis may explain the persistence of the Rh- blood type in human populations.

- A woman is blood type O and Rh-, and her husband is blood type AB and Rh+. Answer the following questions about this couple and their offspring.

- What are the possible genotypes of their offspring in terms of ABO blood group?

- What are the possible phenotypes of their offspring in terms of ABO blood group?

- Can the woman donate blood to her husband? Explain your answer.

- Can the man donate blood to his wife? Explain your answer.

- Type O blood is characterized by the presence of O antigens — explain why this statement is false.

- Explain why newborn hemolytic disease may be more likely to occur in a second pregnancy than in a first.

6.5 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfZhb6lmxjk

Why do blood types matter? - Natalie S. Hodge, TED-Ed, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcZKbjYyOfE

How do blood transfusions work? - Bill Schutt, TED-Ed, 2020.

Attributes

Figure 6.5.1

Following the Blood Donation Trail by EJ Hersom/ USA Department of Defense is in the public domain. [Disclaimer: The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.]

Figure 6.5.2

Antibody by Fvasconcellos on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.3

ABO system codominance.svg, adapted by YassineMrabet (original "Codominant" image from US National Library of Medicine) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.4

ABO_blood_type.svg by InvictaHOG on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 6.5.5

Blood Donor and recipient ABO by CK-12 Foundation is used under a CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) license.

Figure 6.5.6

- Map of Blood Group A by Muntuwandi at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

- Map of Blood Group B by Muntuwandi at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

- Map of Blood Group O by anthro palomar at en.wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) license.

Figure 6.5.7

Toxoplasma_gondii_Life_cycle_PHIL_3421_lores by Alexander J. da Silva, PhD/Melanie Moser, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Public Health Image Library (PHIL#3421) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Table 6.5.1

ABO Blood Group System: Genotypes and Phenotypes was created by Christine Miller.

References

Dean, L. (2005). Chapter 4 Hemolytic disease of the newborn. In Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens [Internet]. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2266/

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Toxoplasmosis [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/toxoplasmosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20356249

MedlinePlus. (2019, January 29). Hemolytic transfusion reaction [online article]. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_9&oldid=946440619

TED-Ed. (2015, June 29). Why do blood types matter? - Natalie S. Hodge. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfZhb6lmxjk&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, February 18). How do blood transfusions work? - Bill Schutt. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcZKbjYyOfE&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, May 10). Chromosome 1. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_1&oldid=955942444

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, March 20). Chromosome 9. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chromosome_9&oldid=946440619

The central nervous system organ inside the skull that is the control center of the nervous system.

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Ribosome Review

The 25-metre long sculpture shown in Figure 4.6.1 is a recognition of the beauty of one of the metabolic functions that takes place in the cells in your body. This artwork brings to life an important structure in living cells: the ribosome, the cell structure where proteins are synthesized. The slender silver strand is the messenger RNA(mRNA) bringing the code for a protein out into the cytoplasm. The purple and green structures are ribosomal subunits (which together form a single ribosome), which can "read" the code on the mRNA and direct the bonding of the correct sequence of amino acids to create a protein. All living cells — whether they are prokaryotic or eukaryotic — contain ribosomes, but only eukaryotic cells also contain a nucleus and several other types of organelles.

What Are Organelles?

An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell that is enclosed within a membrane and performs a specific job. Organelles are involved in many vital cell functions. Organelles in animal cells include the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, vesicles, and vacuoles. Ribosomes are not enclosed within a membrane, but they are still commonly referred to as organelles in eukaryotic cells.

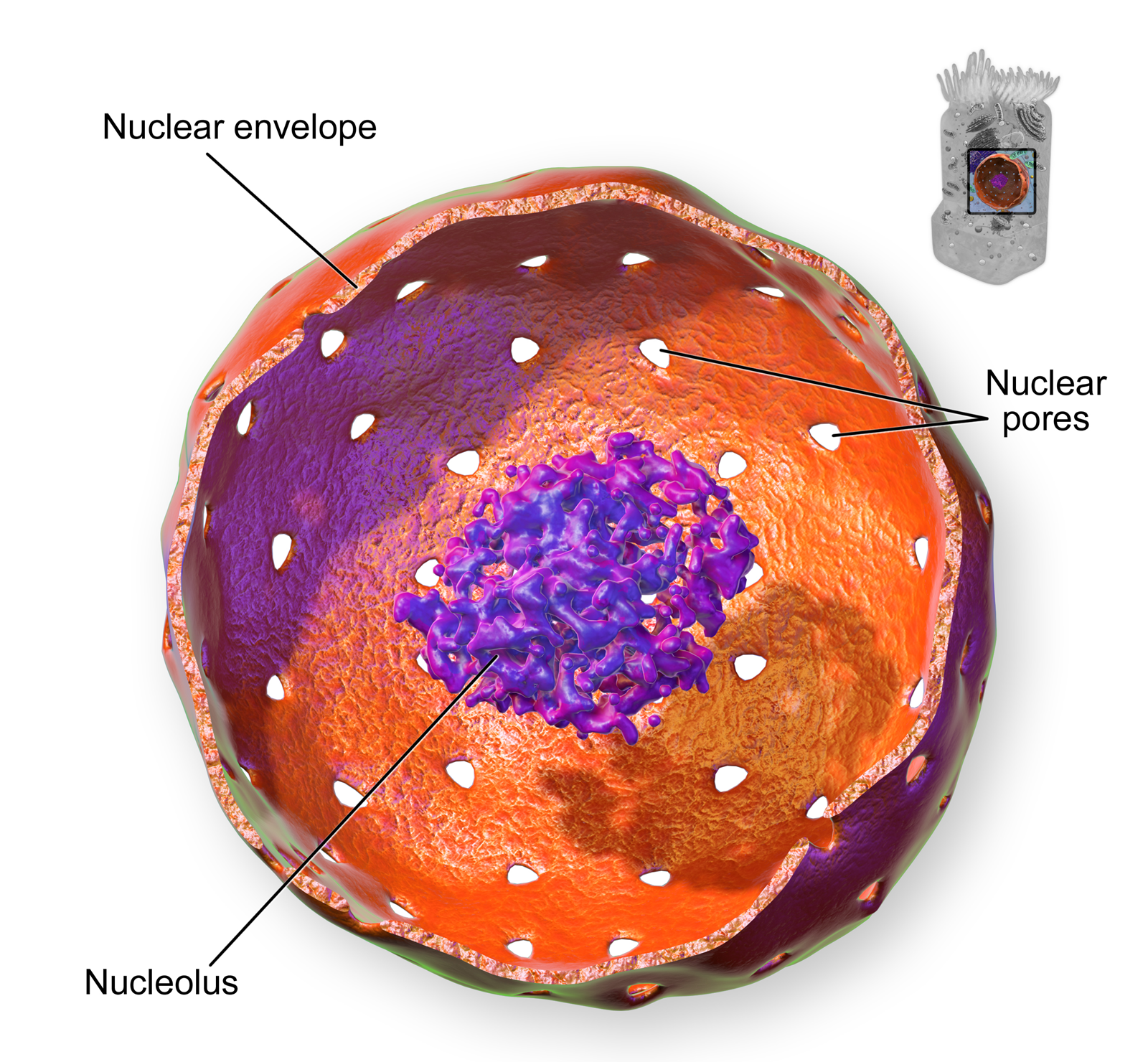

The Nucleus

The nucleus is the largest organelle in a eukaryotic cell, and it's considered the cell’s control center. It contains most of the cell’s DNA(which makes up chromosomes), and it is encoded with the genetic instructions for making proteins. The function of the nucleus is to regulate gene expression, including controlling which proteins the cell makes. In addition to DNA, the nucleus contains a thick liquid called nucleoplasm, which is similar in composition to the cytosol found in the cytoplasm outside the nucleus. Most eukaryotic cells contain just a single nucleus, but some types of cells (such as red blood cells) contain no nucleus and a few other types of cells (such as muscle cells) contain multiple nuclei.

As you can see in the model pictured in Figure 4.6.2, the membrane enclosing the nucleus is called the nuclear envelope. This is actually a double membrane that encloses the entire organelle and isolates its contents from the cellular cytoplasm. Tiny holes called nuclear pores allow large molecules to pass through the nuclear envelope, with the help of special proteins. Large proteins and RNA molecules must be able to pass through the nuclear envelope so proteins can be synthesized in the cytoplasm and the genetic material can be maintained inside the nucleus. The nucleolus shown in the model below is mainly involved in the assembly of ribosomes. After being produced in the nucleolus, ribosomes are exported to the cytoplasm, where they are involved in the synthesis of proteins.

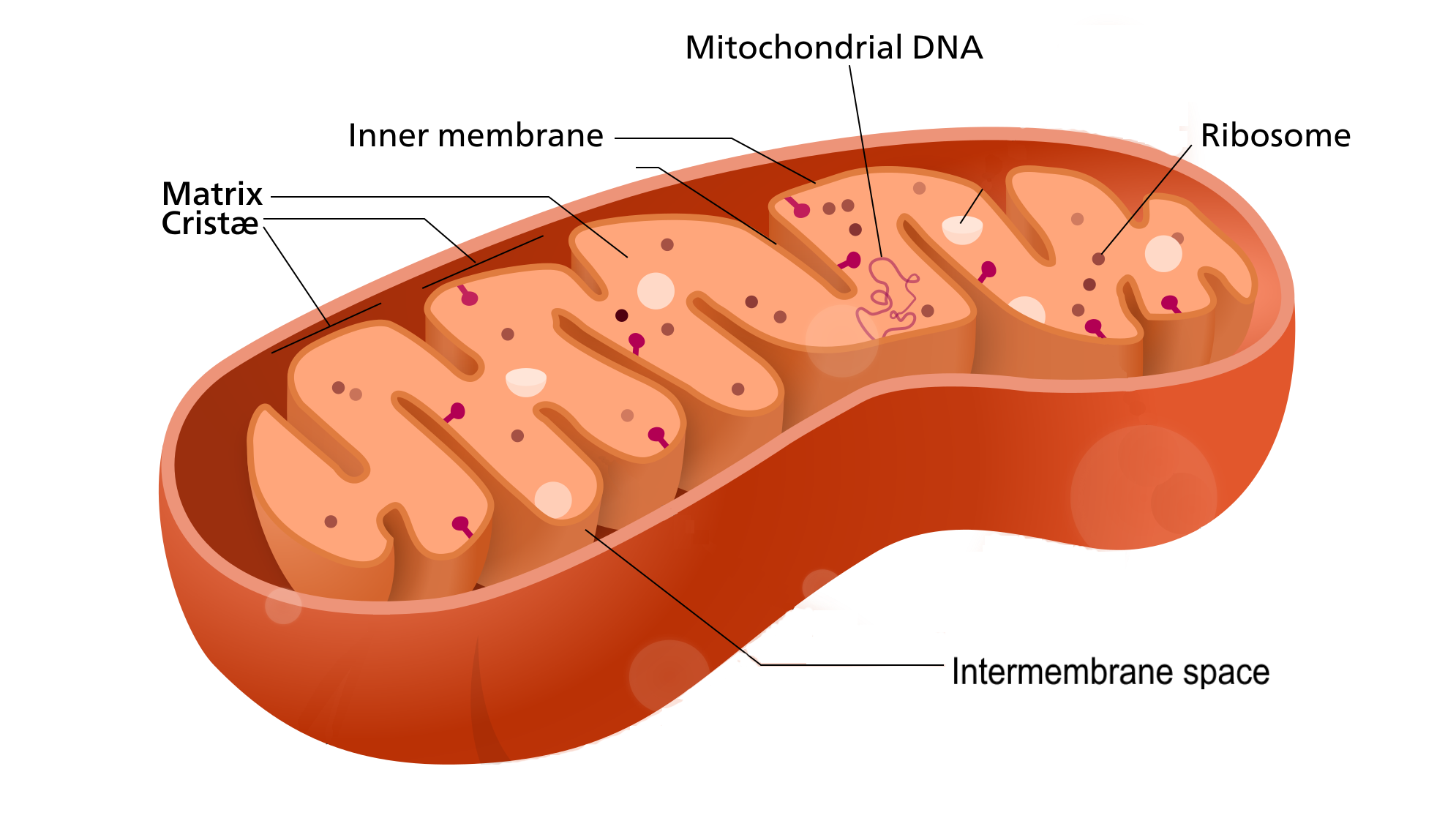

Mitochondria

The mitochondrion (plural, mitochondria) is an organelle that makes energy available to the cell. This is why mitochondria are sometimes referred to as the "power plants of the cell." They use energy from organic compounds (such as glucose) to make molecules of ATP (adenosine triphosphate), an energy-carrying molecule that is used almost universally inside cells for energy.

Mitochondria (as in the Figure 4.6.3 diagram) have a complex structure including an inner and out membrane. In addition, mitochondria have their own DNA, ribosomes, and a version of cytoplasm, called matrix. Does this sound similar to the requirements to be considered a cell? That's because they are!

Scientists think that mitochondria were once free-living organisms because they contain their own DNA. They theorize that ancient prokaryotes infected (or were engulfed by) larger prokaryotic cells, and the two organisms evolved a symbiotic relationship that benefited both of them. The larger cells provided the smaller prokaryotes with a place to live. In return, the larger cells got extra energy from the smaller prokaryotes. Eventually, the smaller prokaryotes became permanent guests of the larger cells, as organelles inside them. This theory is called endosymbiotic theory, and it is widely accepted by biologists today. (See the video in section 4.3 to learn all about endosymbiotic theory.)

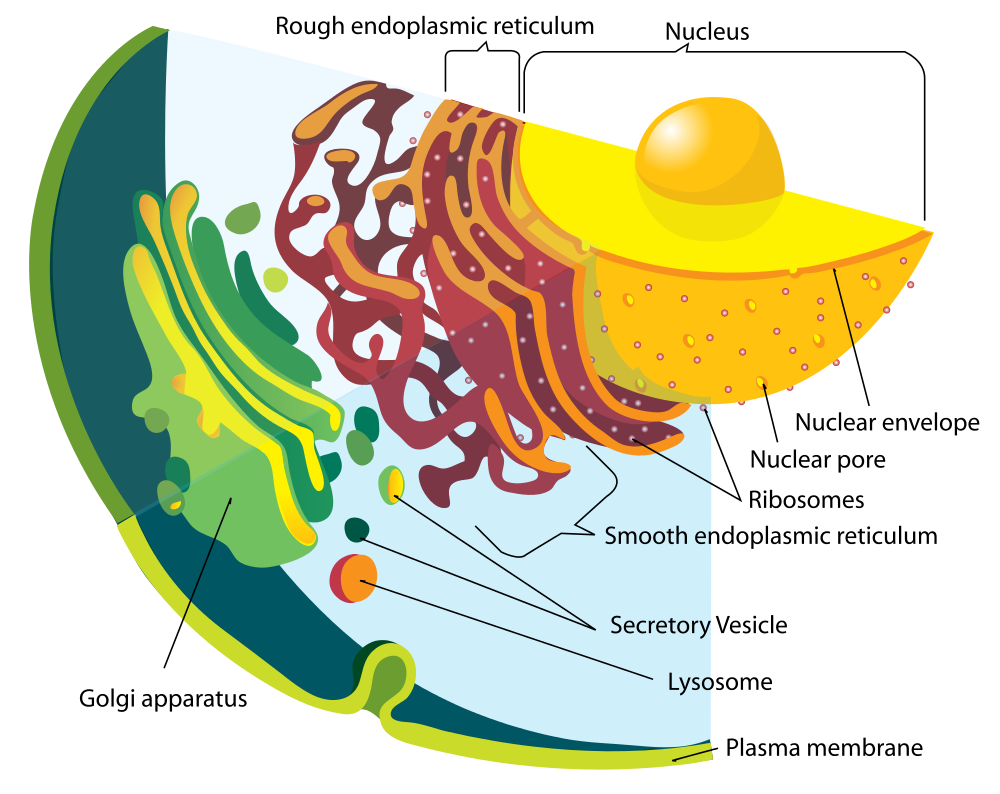

Endoplasmic Reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that helps make and transport proteins and lipids. There are two types of endoplasmic reticulum: rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) and smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER). Both types are shown in Figure 4.6.4.

- rER looks rough because it is studded with ribosomes. It provides a framework for the ribosomes, which make proteins. Bits of its membrane pinch off to form tiny sacs called vesicles, which carry proteins away from the ER.

- sER looks smooth because it does not have ribosomes. sER makes lipids, stores substances, and plays other roles.

The Figure 4.6.4 drawing includes the nucleus, rER, sER, and Golgi apparatus. From the drawing, you can see how all these organelles work together to make and transport proteins.

Golgi Apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (shown in the Figure 4.6.4 diagram) is a large organelle that processes proteins and prepares them for use both inside and outside the cell. You can see the Golgi apparatus in the figure above. The Golgi apparatus is something like a post office. It receives items (proteins from the ER), then packages and labels them before sending them on to their destinations (to different parts of the cell or to the cell membrane for transport out of the cell). The Golgi apparatus is also involved in the transport of lipids around the cell.

Vesicles and Vacuoles

Both vesicles and vacuoles are sac-like organelles made of phospholipid bilayer that store and transport materials in the cell. Vesicles are much smaller than vacuoles and have a variety of functions. The vesicles that pinch off from the membranes of the ER and Golgi apparatus store and transport protein and lipid molecules. You can see an example of this type of transport vesicle in the Figure 4.6.4. Some vesicles are used as chambers for biochemical reactions.

There are some vesicles which are specialized to carry out specific functions. Lysosomes, which use enzymes to break down foreign matter and dead cells, have a double membrane to make sure their contents don't leak into the rest of the cell. Peroxisomes are another type of specialized vesicle with the main function of breaking down fatty acids and some toxins.

Centrioles

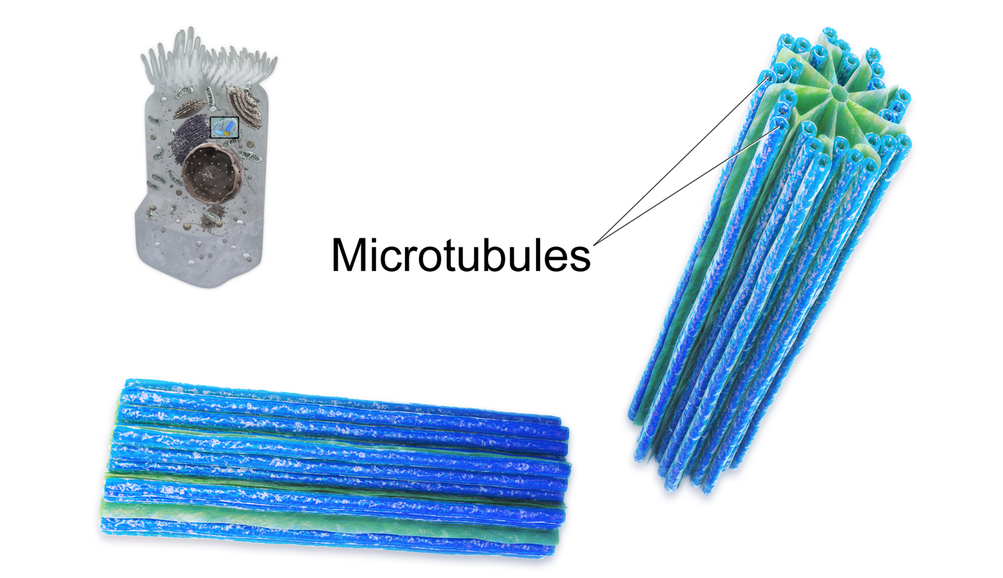

Centrioles are organelles involved in cell division. The function of centrioles is to help organize the chromosomes before cell division occurs so that each daughter cell has the correct number of chromosomes after the cell divides. Centrioles are found only in animal cells, and are located near the nucleus. Each centriole is made mainly of a protein named tubulin. The centriole is cylindrical in shape and consists of many microtubules, as shown in the model pictured in Figure 4.6.5.

Ribosomes

Ribosomes are small structures where proteins are made. Although they are not enclosed within a membrane, they are frequently considered organelles. Each ribosome is formed of two subunits, like the ones pictured at the beginning of this section (Figure 4.6.1) and in Figure 4.6.6. Both subunits consist of proteins and RNA. mRNA from the nucleus carries the genetic code, copied from DNA, which remains in the nucleus. At the ribosome, the genetic code in mRNA is used to assemble and join together amino acids to make proteins. Ribosomes can be found alone or in groups within the cytoplasm, as well as on the rER.

4.6 Summary

- An organelle is a structure within the cytoplasm of a eukaryotic cell that is enclosed within a membrane and performs a specific job. Although ribosomes are not enclosed within a membrane, they are still commonly referred to as organelles in eukaryotic cells.

- The nucleus is the largest organelle in a eukaryotic cell, and it is considered to be the cell's control center. It controls gene expression, including controlling which proteins the cell makes.

- The mitochondrion (plural, mitochondria) is an organelle that makes energy available to the cells. It is like the power plant of the cell. According to the widely accepted endosymbiotic theory, mitochondria evolved from prokaryotic cells that were once free-living organisms that infected or were engulfed by larger prokaryotic cells.

- The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle that helps make and transport proteins and lipids. Rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) is studded with ribosomes. Smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER) has no ribosomes.

- The Golgi apparatus is a large organelle that processes proteins and prepares them for use both inside and outside the cell. It is also involved in the transport of lipids around the cell.

- Both vesicles and vacuoles are sac-like organelles that may be used to store and transport materials in the cell or as chambers for biochemical reactions. Lysosomes and peroxisomes are special types of vesicles that break down foreign matter, dead cells, or poisons.

- Centrioles are organelles located near the nucleus that help organize the chromosomes before cell division so each daughter cell receives the correct number of chromosomes.

- Ribosomes are small structures where proteins are made. They are found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. They may be found alone or in groups within the cytoplasm or on the rER.

4.6 Review Questions

- What is an organelle?

- Describe the structure and function of the nucleus.

- Explain how the nucleus, ribosomes, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus work together to make and transport proteins.

- Why are mitochondria referred to as the "power plants of the cell"?

- What roles are played by vesicles and vacuoles?

- Why do all cells need ribosomes — even prokaryotic cells that lack a nucleus and other cell organelles?

- Explain endosymbiotic theory as it relates to mitochondria. What is one piece of evidence that supports this theory?

-

4.6 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URUJD5NEXC8&t=121s

Biology: Cell Structure I Nucleus Medical Media, Nucleus Medical Media, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Id2rZS59xSE&feature=youtu.be

David Bolinsky: Visualizing the wonder of a living cell, TED, 2007.

Attributes

Figure 4.6.1

Ribosomes at Work by Pedrik on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 4.6.2

Nucleus by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.3

Mitochondrion_structure.svg by Kelvinsong; modified by Sowlos on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.4

Endomembrane_system_diagram_en.svg by Mariana Ruiz [LadyofHats] on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 4.6.5

Centrioles by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 4.6.6

Ribosome_shape by Vossman on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license.

References

Blausen.com staff. (2014). Nucleus - Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Medicine/Medical_gallery_of_Blausen_Medical_2014

Blausen.com staff (2014). Centrioles - Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/WikiJournal_of_Medicine/Medical_gallery_of_Blausen_Medical_2014

Nucleus Medical Media. (2015, March 18). Biology: Cell structure I Nucleus Medical Media. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URUJD5NEXC8&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2007, July 24). David Bolinsky: Visualizing the wonder of a living cell. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Id2rZS59xSE&feature=youtu.be

Created by: CK-12/Adapted by Christine Miller

Oh, the Agony!

Wearing braces can be very uncomfortable, but it is usually worth it. Braces and other orthodontic treatments can re-align the teeth and jaws to improve bite and appearance. Braces can change the position of the teeth and the shape of the jaws because the human body is malleable. Many phenotypic traits — even those that have a strong genetic basis — can be molded by the environment. Changing the phenotype in response to the environment is just one of several ways we respond to environmental stress.

Types of Responses to Environmental Stress

There are four different types of responses that humans may make to cope with environmental stress:

- Adaptation

- Developmental adjustment

- Acclimatization

- Cultural responses

The first three types of responses are biological in nature, and the fourth type is cultural. Only adaptation involves genetic change and occurs at the level of the population or species. The other three responses do not require genetic change, and they occur at the individual level.

Adaptation

An adaptation is a genetically-based trait that has evolved because it helps living things survive and reproduce in a given environment. Adaptations generally evolve in a population over many generations in response to stresses that last for a long period of time. Adaptations come about through natural selection. Those individuals who inherit a trait that confers an advantage in coping with an environmental stress are likely to live longer and reproduce more. As a result, more of their genes pass on to the next generation. Over many generations, the genes and the trait they control become more frequent in the population.

A Classic Example: Hemoglobin S and Malaria

Probably the most frequently-cited example of a genetic adaptation to an environmental stress is sickle cell trait. As you read in the previous section, people with sickle cell trait have one abnormal allele (S) and one normal allele (A) for hemoglobin, the red blood cell protein that carries oxygen in the blood. Sickle cell trait is an adaptation to the environmental stress of malaria, because people with the trait have resistance to this parasitic disease. In areas where malaria is endemic (present year-round), the sickle cell trait and its allele have evolved to relatively high frequencies. It is a classic example of natural selection favoring heterozygotes for a gene with two alleles. This type of selection keeps both alleles at relatively high frequencies in a population.

To Taste or Not to Taste

Another example of an adaptation in humans is the ability to taste bitter compounds. Plants produce a variety of toxic compounds in order to protect themselves from being eaten, and these toxic compounds often have a bitter taste. The ability to taste bitter compounds is thought to have evolved as an adaptation, because it prevented people from eating poisonous plants. Humans have many different genes that code for bitter taste receptors, allowing us to taste a wide variety of bitter compounds.

A harmless bitter compound called phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) is not found naturally in plants, but it is similar to toxic bitter compounds that are found in plants. Humans' ability to taste this harmless substance has been tested in many different populations. In virtually every population studied, there are some people who can taste PTC (called tasters), and some people who cannot taste PTC, (called nontasters). The ratio of tasters to non-tasters varies among populations, but on average, 75 per cent of people can taste PTC and 25 per cent cannot.

Like many scientific discoveries, human variation in PTC-taster status was discovered by chance. Around 1930, a chemist named Arthur Fox was working with powdered PTC in his lab. Some of the powder accidentally blew into the air. Another lab worker noticed that the powdered PTC tasted bitter, but Fox couldn't detect any taste at all. Fox wondered how to explain this difference in PTC-tasting ability. Geneticists soon determined that PTC-taster status is controlled by a single gene with two common alleles, usually represented by the letters T and t. The T allele encodes a chemical receptor protein (found in taste buds on the tongue, as illustrated in Figure 6.4.2) that can strongly bind to PTC. The other allele, t, encodes a version of the receptor protein that cannot bind as strongly to PTC. The particular combination of these two alleles that a person inherits determines whether the person finds PTC to taste very bitter (TT), somewhat bitter (Tt), or not bitter at all (tt).

If the ability to taste bitter compounds is advantageous, why does every human population studied contain a significant percentage of people who are nontasters? Why has the nontasting allele been preserved in human populations at all? Some scientists hypothesize that the nontaster allele actually confers the ability to taste some other, yet-to-be identified, bitter compound in plants. People who inherit both alleles would presumably be able to taste a wider range of bitter compounds, so they would have the greatest ability to avoid plant toxins. In other words, the heterozygote genotype for the taster gene would be the most fit and favored by natural selection.

Most people no longer have to worry whether the plants they eat contain toxins. The produce you grow in your garden or buy at the supermarket consists of known varieties that are safe to eat. However, natural selection may still be at work in human populations for the PTC-taster gene, because PTC tasters may be more sensitive than nontasters to bitter compounds in tobacco and vegetables in the cabbage family (that is, cruciferous vegetables, such as the broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage pictured in Figure 6.4.3).

- People who find PTC to taste very bitter are less likely to smoke tobacco, presumably because tobacco smoke has a stronger bitter taste to these individuals. In this case, selection would favor taster genotypes, because tasters would be more likely to avoid smoking and its serious health risks.

- Strong tasters find cruciferous vegetables to taste bitter. As a result, they may avoid eating these vegetables (and perhaps other foods, as well), presumably resulting in a diet that is less varied and nutritious. In this scenario, natural selection might work against taster genotypes.

Figure 6.4.3 Cruciferous vegetables.

Developmental Adjustment

It takes a relatively long time for genetic change in response to environmental stress to produce a population with adaptations. Fortunately, we can adjust to some environmental stresses more quickly by changing in nongenetic ways. One type of nongenetic response to stress is developmental adjustment. This refers to phenotypic change that occurs during development in infancy or childhood, and that may persist into adulthood. This type of change may be irreversible by adulthood.

Phenotypic Plasticity

Developmental adjustment is possible because humans have a high degree of phenotypic plasticity, which is the ability to alter the phenotype in response to changes in the environment. Phenotypic plasticity allows us to respond to changes that occur within our lifetime, and it is particularly important for species (like our own) that have a long generation time. With long generations, evolution of genetic adaptations may occur too slowly to keep up with changing environmental stresses.

Developmental Adjustment and Cultural Practices

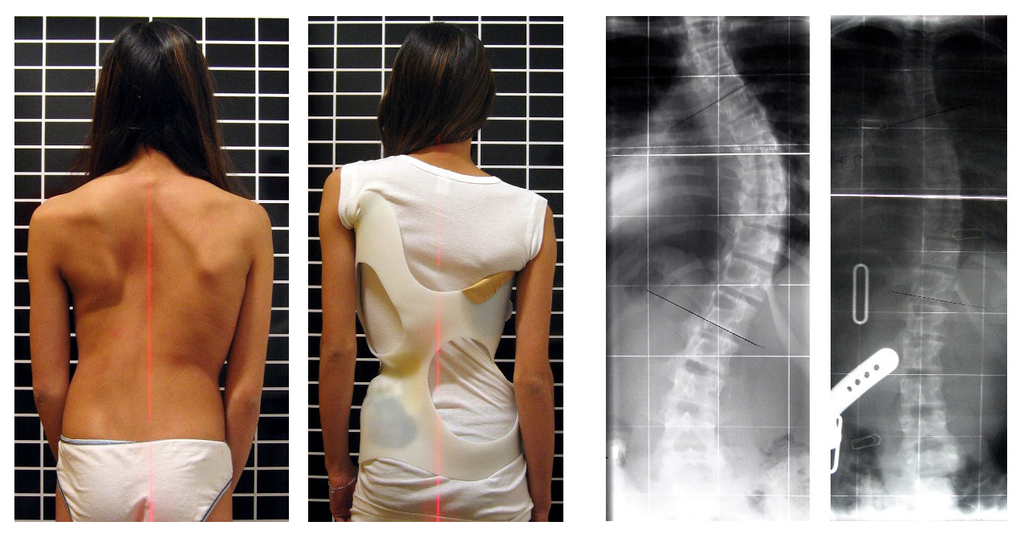

Developmental adjustment may be the result of naturally occurring environmental stresses or cultural practices, including medical or dental treatments. Like our example at the beginning of this section, using braces to change the shape of the jaw and the position of the teeth is an example of a dental practice that brings about a developmental adjustment. Another example of developmental adjustment is the use of a back brace to treat scoliosis (see images in Figure 6.4.4). Scoliosis is an abnormal curvature from side to side in the spine. If the problem is not too severe, a brace, if worn correctly, should prevent the curvature from worsening as a child grows, although it cannot straighten a curve that is already present. Surgery may be required to do that.

Developmental Adjustment and Nutritional Stress

An important example of developmental adjustment that results from a naturally occurring environmental stress is the cessation of physical growth that occurs in children who are under nutritional stress. Children who lack adequate food to fuel both growth and basic metabolic processes are likely to slow down in their growth rate — or even to stop growing entirely. Shunting all available calories and nutrients into essential life functions may keep the child alive at the expense of increasing body size.

Table 6.4.1 shows the effects of inadequate diet on children's' growth in several countries worldwide. For each country, the table gives the prevalence of stunting in children under the age of five. Children are considered stunted if their height is at least two standard deviations below the median height for their age in an international reference population.

Table 6.4.1

Percentage of Stunting in Young Children in Selected Countries (2011-2015)

| Percentage of Stunting in Young Children in Selected Countries (2011-2015) | |

| Country | Per cent of Children Under Age 5 with Stunting |

| United States | 2.1 |

| Turkey | 9.5 |

| Mexico | 13.6 |

| Thailand | 16.3 |

| Iraq | 22.6 |

| Philippines | 33.6 |

| Pakistan | 45.0 |

| Papua New Guinea | 49.5 |

After a growth slow-down occurs and if adequate food becomes available, a child may be able to make up the loss of growth. If food is plentiful, the child may grow more rapidly than normal until the original, genetically-determined growth trajectory is reached. If the inadequate diet persists, however, the failure of growth may become chronic, and the child may never reach his or her full potential adult size.

Phenotypic plasticity of body size in response to dietary change has been observed in successive generations within populations. For example, children in Japan were taller, on average, in each successive generation after the end of World War II. Boys aged 14-15 years old in 1986 were an average of about 18 cm (7 in.) taller than boys of the same age in 1959, a generation earlier. This is a highly significant difference, and it occurred too quickly to be accounted for by genetic change. Instead, the increase in height is a developmental adjustment, thought to be largely attributable to changes in the Japanese diet since World War II. During this period, there was an increase in the amount of animal protein and fat, as well as in the total calories consumed.

Acclimatization

Other responses to environmental stress are reversible and not permanent, whether they occur in childhood or adulthood. The development of reversible changes to environmental stress is called acclimatization. Acclimatization generally develops over a relatively short period of time. It may take just a few days or weeks to attain a maximum response to a stress. When the stress is no longer present, the acclimatized state declines, and the body returns to its normal baseline state. Generally, the shorter the time for acclimatization to occur, the more quickly the condition is reversed when the environmental stress is removed.

Acclimatization to UV Light

A common example of acclimatization is tanning of the skin (see Figure 6.4.5). This occurs in many people in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Special pigment cells in the skin, called melanocytes, produce more of the brown pigment melanin when exposed to sunlight. The melanin collects near the surface of the skin where it absorbs UV radiation so it cannot penetrate and potentially damage deeper skin structures. Tanning is a reversible change in the phenotype that helps the body deal temporarily with the environmental stress of high levels of UV radiation. When the skin is no longer exposed to the sun’s rays, the tan fades, generally over a period of a few weeks or months.

Figure 6.4.5 Tanning of the skin occurs in many people in response to exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun.

Acclimatization to Heat

Another common example of acclimatization occurs in response to heat. Changes that occur with heat acclimatization include increased sweat output and earlier onset of sweat production, which helps the body stay cool because evaporation of sweat takes heat from the body’s surface in a process called evaporative cooling. It generally takes a couple of weeks for maximum heat acclimatization to come about by gradually working out harder and longer at high air temperatures. The changes that occur with acclimatization just as quickly subside when the body is no longer exposed to excessive heat.

Acclimatization to High Altitude

Short term acclimatization to high altitude occurs as a response to low levels of oxygen in the blood. This reduced level of oxygen is detected by carotid bodies, which will trigger in increase in breathing and heart rate. Over a period of weeks the body will compensate by increasing red blood cell production, thereby improving the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. This is why mountaineers wishing to climb to the peak of Mount Everest must complete the full climb in portions; it is recommended that climbers spend 2-3 days acclimatizing for every 600 metres of elevation increase. In addition, the higher to altitude, the longer it make take to acclimatize; climbers are advised to spend 4-5 days acclimatizing at base camp (whether the base camp in Nepal or China) before completing the final leg of the climb to the peak. The concentration of red blood cells gradually decreases to normal levels once a climber returns to their normal elevation.

Cultural Responses

More than any other species, humans respond to environmental stresses with learned behaviors and technology. These cultural responses allow us to change our environments to control stresses, rather than changing our bodies genetically or physiologically to cope with the stresses. Even archaic humans responded to some environmental stresses in this way. For example, Neanderthals used shelters, fires, and animal hides as clothing to stay warm in the cold climate in Europe during the last ice age. Today, we use more sophisticated technologies to stay warm in cold climates while retaining our essentially tropical-animal anatomy and physiology. We also use technology (such as furnaces and air conditioners) to avoid temperature stress and stay comfortable in hot or cold climates.

6.4 Summary

- Humans may respond to environmental stress in four different ways: adaptation, developmental adjustment, acclimatization, and cultural responses.

- An adaptation is a genetically based trait that has evolved because it helps living things survive and reproduce in a given environment. Adaptations evolve by natural selection in populations over a relatively long period to time. Examples of adaptations include sickle cell trait as an adaptation to the stress of endemic malaria and the ability to taste bitter compounds as an adaptation to the stress of bitter-tasting toxins in plants.

- A developmental adjustment is a non-genetic response to stress that occurs during infancy or childhood, and that may persist into adulthood. This type of change may be irreversible. Developmental adjustment is possible because humans have a high degree of phenotypic plasticity. It may be the result of environmental stresses (such as inadequate food), which may stunt growth, or cultural practices (such as orthodontic treatments), which re-align the teeth and jaws.

- Acclimatization is the development of reversible changes to environmental stress that develop over a relatively short period of time. The changes revert to the normal baseline state after the stress is removed. Examples of acclimatization include tanning of the skin and physiological changes (such as increased sweating) that occur with heat acclimatization.

- More than any other species, humans respond to environmental stress with learned behaviors and technology, which are cultural responses. These responses allow us to change our environment to control stress, rather than changing our bodies genetically or physiologically to cope with stress. Examples include using shelter, fire, and clothing to cope with a cold climate.

6.4 Review Questions

- List four different types of responses that humans may make to cope with environmental stress.

- Define adaptation.

-

- Explain how natural selection may have resulted in most human populations having people who can and people who cannot taste PTC.

- What is a developmental adjustment?

- Define phenotypic plasticity.

- Explain why phenotypic plasticity may be particularly important in a species with a long generation time.

- Why may stunting of growth occur in children who have an inadequate diet? Why is stunting preferable to the alternative?

- What is acclimatization?

- How does acclimatization to heat come about, and what are two physiological changes that occur in heat acclimatization?

- Give an example of a cultural response to heat stress.

- Which is more likely to be reversible — a change due to acclimatization, or a change due to developmental adjustment? Explain your answer.

6.4 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upp9-w6GPhU

Could we survive prolonged space travel? - Lisa Nip, TED-Ed, 2016.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRnrIpUMyZQ&t=182s

How this disease changes the shape of your cells - Amber M. Yates, TED-Ed, 2019.

Attributions

Figure 6.4.1

Free_Awesome_Girl_With_Braces_Close_Up by D. Sharon Pruitt from Hill Air Force Base, Utah, USA on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 6.4.2

Tongue by Mahdiabbasinv on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

Figure 6.4.3

- White cauliflower on brown wooden chopping board by Louis Hansel @shotsoflouis on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Broccoli on wooden chopping board by Louis Hansel @shotsoflouis on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Green cabbage close up by Craig Dimmick on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Cabbage hybrid/ brussel sprouts by Solstice Hannan on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Kale by Laura Johnston on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Tiny bok choy at the Asian market by Jodie Morgan on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 6.4.4

Scoliosis_patient_in_cheneau_brace_correcting_from_56_to_27_deg by Weiss H.R. from Scoliosis Journal/BioMed Central Ltd. on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 6.4.5

- Tan Lines by k.steudel on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

- Twin tan lines (all sizes) by Quinn Dombrowski on Flickr is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/) license.

- Wedding ring tan line by Quinn Dombrowski on Flickr is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/) license.

- Tan by Evil Erin on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/) license.

Figure 6.4.6

Nepalese base camp by Mark Horrell on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

References

TED-Ed. (2016, October 4). Could we survive prolonged space travel? - Lisa Nip. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=upp9-w6GPhU&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2019, May 6). How this disease changes the shape of your cells - Amber M. Yates. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hRnrIpUMyZQ&feature=youtu.be

Weiss, H. (2007). Is there a body of evidence for the treatment of patients with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS)? [Figure 2 - digital photograph], Scoliosis, 2(19). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-7161-2-19

The front lobe of the pituitary gland that synthesizes and secretes pituitary hormones.

A membrane protein involved in the movement of ions, small molecules, or macromolecules, such as another protein, across a biological membrane.

A hormone is a signaling molecule produced by glands in multicellular organisms that target distant organs to regulate physiology and behavior.

Image shows a diagram of Thrombocytes in their normal state and activated.

Thrombocytes (platelets) are typically ovoid during normal circulation, but when activated become super fibrous. The not activated platelets look like very smooth and the activated platelets look like sea anemones- lots of little projects sticking out of their surface.

A membrane protein involved in the movement of ions, small molecules, or macromolecules, such as another protein, across a biological membrane.

Structures containing neuronal cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system.

accessory organ of the skin made of sheets of dead keratinocytes at the distal ends of the fingers and toes

accessory organ of the skin made of sheets of dead keratinocytes at the distal ends of the fingers and toes

Image shows a diagram of Killer T Cell funtion. An infected cell displays a pathogen antigen on an MHC. The Killer T Cell interacts with the MHC and in response produces perforin ( a protein that pokes holes in cell membranes) and granzymes (proteins that instruct a cell to carry out programmed cell death). The infected cell dies from the combination of these substances, and as it dies, so does the pathogen inside the infected cell. The Killer T Cell is free to move on and find and destroy other infected cells.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Case Study: Flight Risk

Nineteen-year-old Malcolm is about to take his first plane flight. Shortly after he boards the plane and sits down, a man in his late sixties sits next to him in the aisle seat. About half an hour after the plane takes off, the pilot announces that she is turning the seat belt light off, and that it is safe to move around the cabin.

The man in the aisle seat — who has introduced himself to Malcolm as Willie — immediately unbuckles his seat belt and paces up and down the aisle a few times before returning to his seat. After about 45 minutes, Willie gets up again, walks some more, then sits back down and does some foot and leg exercises. After the third time Willie gets up and paces the aisles, Malcolm asks him whether he is walking so much to accumulate steps on a pedometer or fitness tracking device. Willie laughs and says no. He is actually trying to do something even more important for his health — prevent a blood clot from forming in his legs.

Willie explains that he has a chronic condition: heart failure. Although it sounds scary, his condition is currently well-managed, and he is able to lead a relatively normal lifestyle. However, it does put him at risk of developing other serious health conditions, such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which is when a blood clot occurs in the deep veins, usually in the legs. Air travel — and other situations where a person has to sit for a long period of time — increases the risk of DVT. Willie’s doctor said that he is healthy enough to fly, but that he should walk frequently and do leg exercises to help avoid a blood clot.

As you read this chapter, you will learn about the heart, blood vessels, and blood that make up the cardiovascular system, as well as disorders of the cardiovascular system, such as heart failure. At the end of the chapter you will learn more about why DVT occurs, why Willie has to take extra precautions when he flies, and what can be done to lower the risk of DVT and its potentially deadly consequences.

Chapter Overview: Cardiovascular System

In this chapter, you will learn about the cardiovascular system, which transports substances throughout the body. Specifically, you will learn about:

- The major components of the cardiovascular system: the heart, blood vessels, and blood.

- The functions of the cardiovascular system, including transporting needed substances (such as oxygen and nutrients) to the cells of the body, and picking up waste products.

- How blood is oxygenated through the pulmonary circulation, which transports blood between the heart and lungs.

- How blood is circulated throughout the body through the systemic circulation.

- The components of blood — including plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets — and their specific functions.

- Types of blood vessels — including arteries, veins, and capillaries — and their functions, similarities, and differences.

- The structure of the heart, how it pumps blood, and how contractions of the heart are controlled.

- What blood pressure is and how it is regulated.

- Blood disorders, including anemia, HIV, and leukemia.

- Cardiovascular diseases (including heart attack, stroke, and angina), and the risk factors and precursors — such as high blood pressure and atherosclerosis — that contribute to them.

As you read the chapter, think about the following questions:

- What is heart failure?Why do you think it increases the risk of DVT?

- What is a blood clot? What are possible health consequences of blood clots?

- Why do you think sitting for long periods of time increases the risk of DVT? Why does walking and exercising the legs help reduce this risk?

Attribution

Figure 14.1.1

aircraft-1583871_1920 [photo] by olivier89 from Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/de/service/license/).

A peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas. It works to raise the concentration of glucose and fatty acids in the bloodstream, and is considered to be the main catabolic hormone of the body. It is also used as a medication to treat a number of health conditions.

Glucose (also called dextrose) is a simple sugar with the molecular formula C6H12O6. Glucose is the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using energy from sunlight.

Biological molecules that lower amount the energy required for a reaction to occur.

one of a pair of glands located on top of the kidneys that secretes hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Seeing Your Breath

Why can you “see your breath” on a cold day? The air you exhale through your nose and mouth is warm like the inside of your body. Exhaled air also contains a lot of water vapor, because it passes over moist surfaces from the lungs to the nose or mouth. The water vapor in your breath cools suddenly when it reaches the much colder outside air. This causes the water vapor to condense into a fog of tiny droplets of liquid water. You release water vapor and other gases from your body through the process of respiration.

What is Respiration?

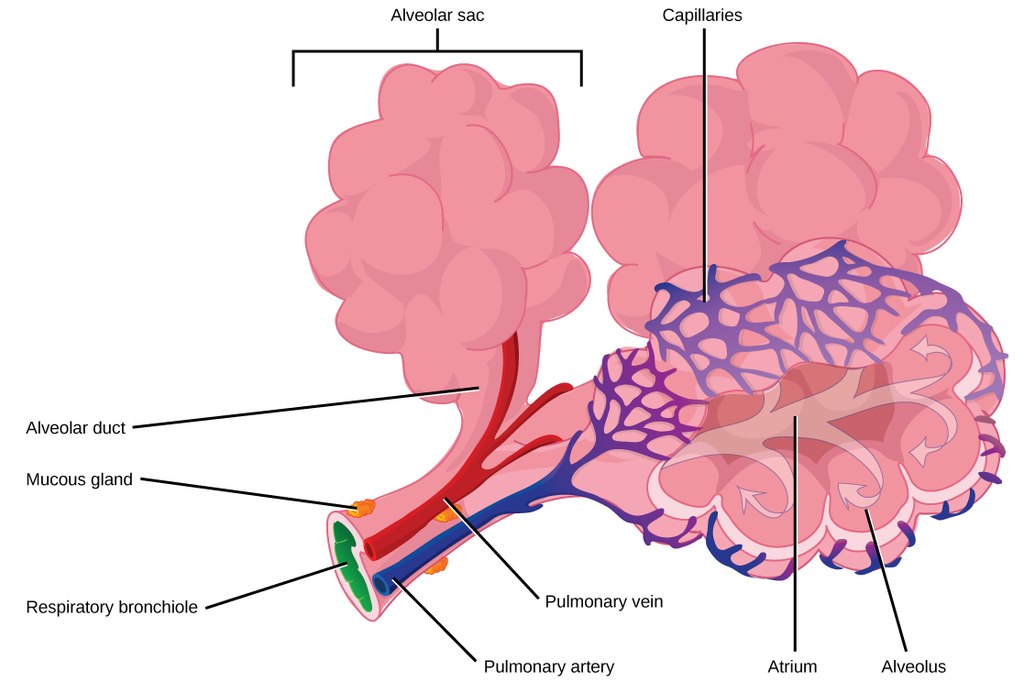

Respiration is the life-sustaining process in which gases are exchanged between the body and the outside atmosphere. Specifically, oxygen moves from the outside air into the body; and water vapor, carbon dioxide, and other waste gases move from inside the body to the outside air. Respiration is carried out mainly by the respiratory system. It is important to note that respiration by the respiratory system is not the same process as cellular respiration —which occurs inside cells — although the two processes are closely connected. Cellular respiration is the metabolic process in which cells obtain energy, usually by “burning” glucose in the presence of oxygen. When cellular respiration is aerobic, it uses oxygen and releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. Respiration by the respiratory system supplies the oxygen needed by cells for aerobic cellular respiration, and removes the carbon dioxide produced by cells during cellular respiration.

Respiration by the respiratory system actually involves two subsidiary processes. One process is ventilation, or breathing. Ventilation is the physical process of conducting air to and from the lungs. The other process is gas exchange. This is the biochemical process in which oxygen diffuses out of the air and into the blood, while carbon dioxide and other waste gases diffuse out of the blood and into the air. All of the organs of the respiratory system are involved in breathing, but only the lungs are involved in gas exchange.

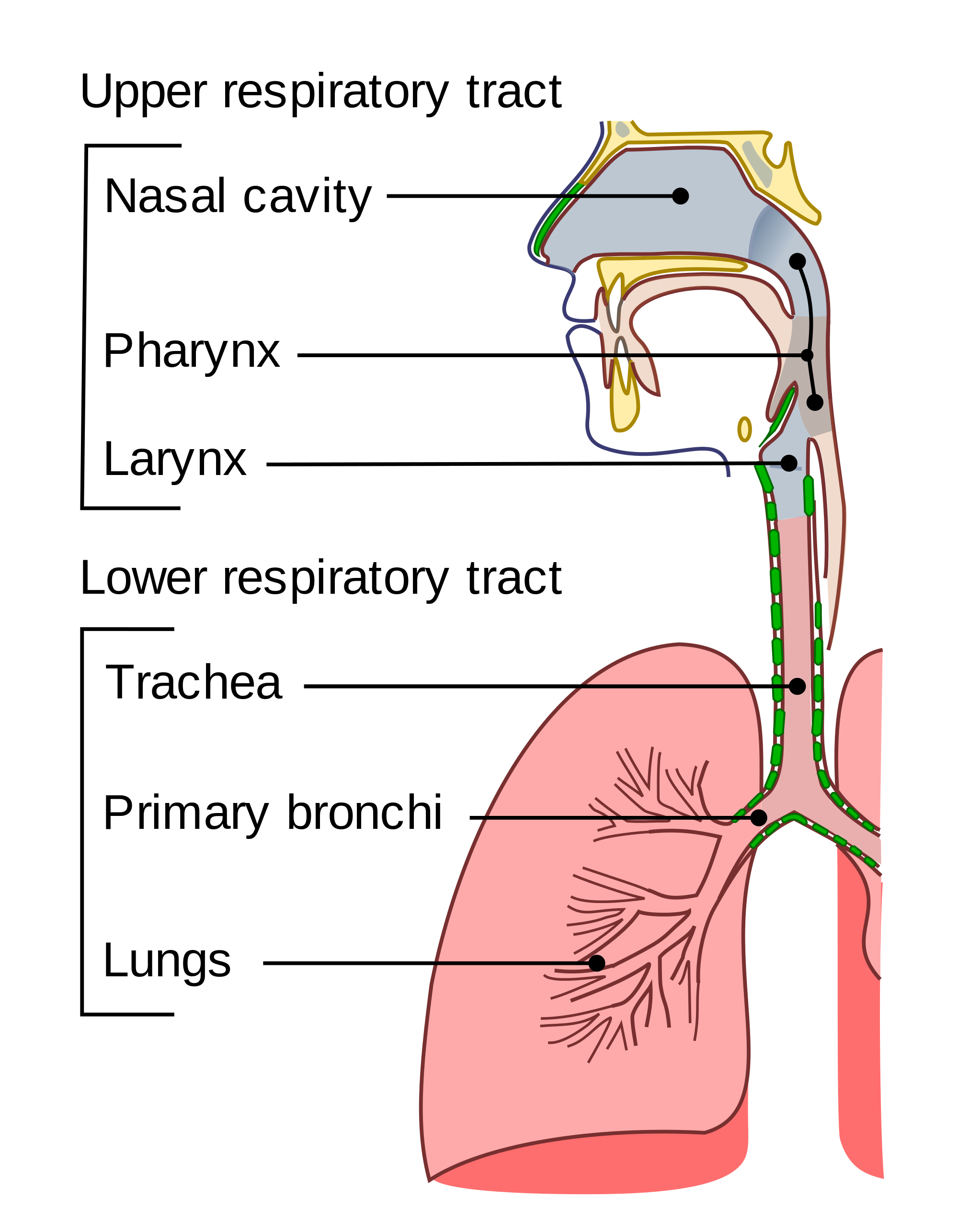

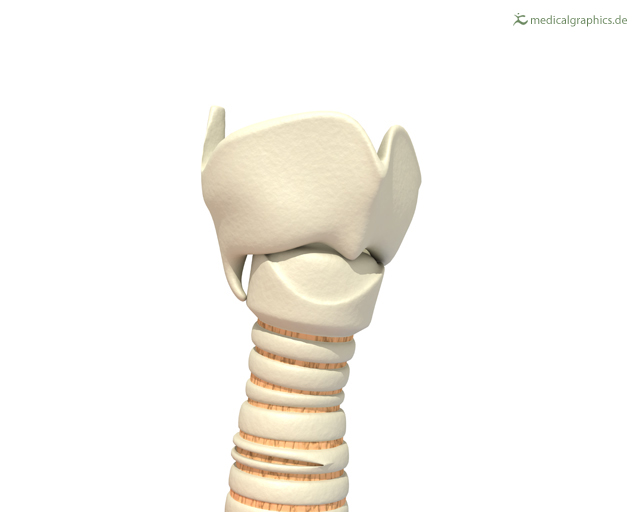

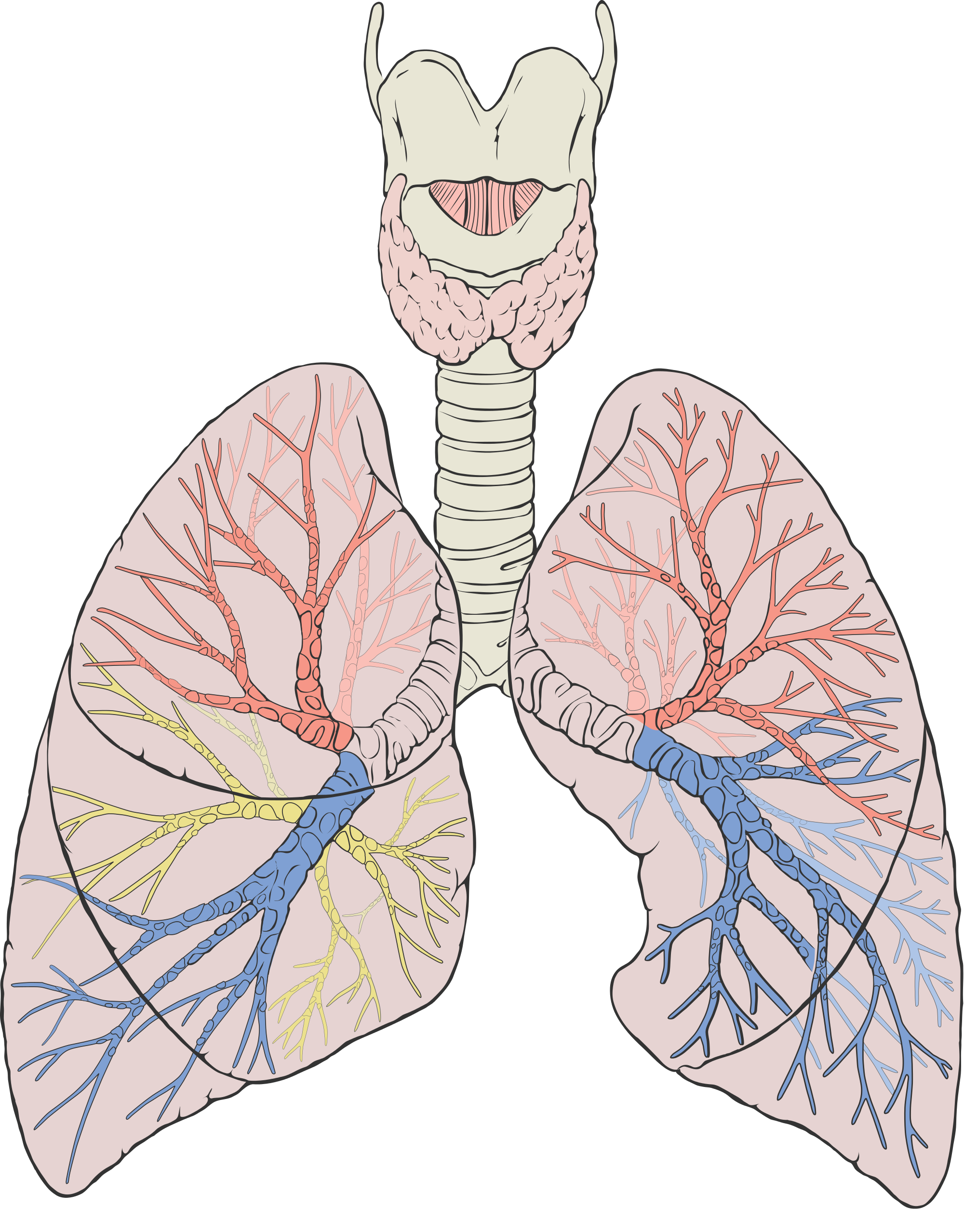

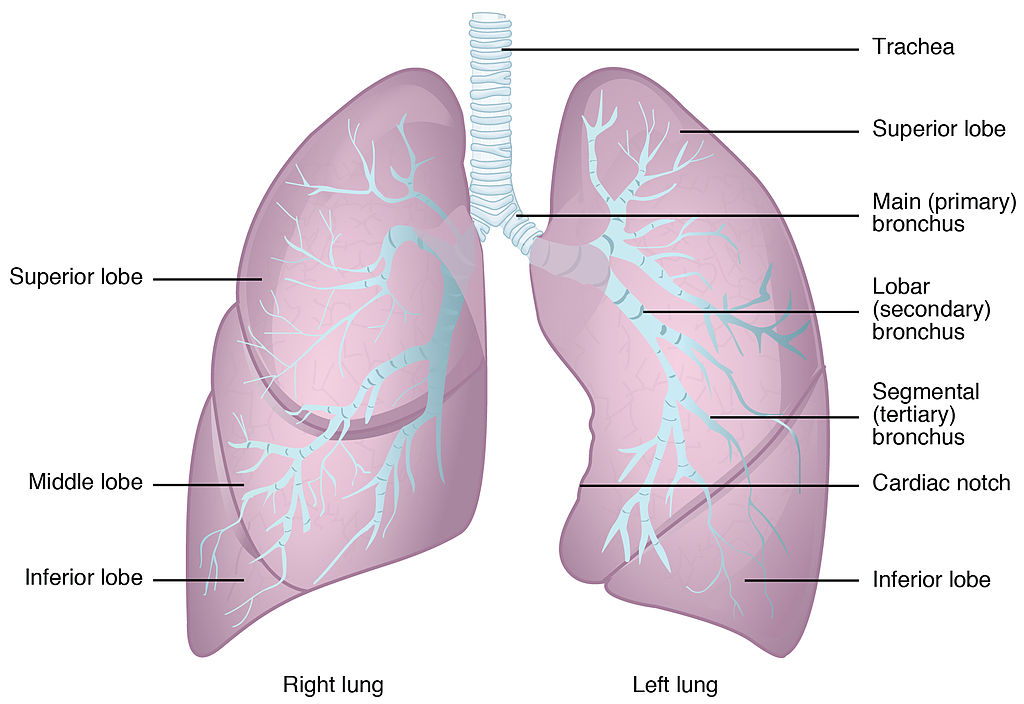

Respiratory Organs

The organs of the respiratory system form a continuous system of passages, called the respiratory tract, through which air flows into and out of the body. The respiratory tract has two major divisions: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The organs in each division are shown in Figure 13.2.2. In addition to these organs, certain muscles of the thorax (body cavity that fills the chest) are also involved in respiration by enabling breathing. Most important is a large muscle called the diaphragm, which lies below the lungs and separates the thorax from the abdomen. Smaller muscles between the ribs also play a role in breathing.

Upper Respiratory Tract

All of the organs and other structures of the upper respiratory tract are involved in conduction, or the movement of air into and out of the body. Upper respiratory tract organs provide a route for air to move between the outside atmosphere and the lungs. They also clean, humidify, and warm the incoming air. No gas exchange occurs in these organs.

Nasal Cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space in the skull above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. It is a continuation of the two nostrils. As inhaled air flows through the nasal cavity, it is warmed and humidified by blood vessels very close to the surface of this epithelial tissue . Hairs in the nose and mucous produced by mucous membranes help trap larger foreign particles in the air before they go deeper into the respiratory tract. In addition to its respiratory functions, the nasal cavity also contains chemoreceptors needed for sense of smell, and contribution to the sense of taste.

Pharynx