8.7 Human Senses

Seeing Is Believing

At first glance, Figure 8.7.1 appears to be just random dots of colour, but hidden within it is the three-dimensional shape of a bee. Can you see it among the dots? This figure is an example of a stereogram, which is a two-dimensional picture that, when viewed correctly, reveals a three-dimensional object. If you can’t see the hidden image, it doesn’t mean that there is anything wrong with your eyes. It’s all in how your brain interprets what your eyes are sensing. The eyes are special sensory organs, and vision is one of our special senses.

Special and General Senses

The human body has two basic types of senses, called special senses and general senses. Special senses have specialized sense organs that gather sensory information and change it into nerve impulses. Special senses include vision (for which the eyes are the specialized sense organs), hearing (ears), balance (ears), taste (tongue), and smell (nasal passages). General senses, in contrast, are all associated with the sense of touch. They lack special sense organs. Instead, sensory information about touch is gathered by the skin and other body tissues, all of which have important functions besides gathering sense information. Whether the senses are special or general, however, they all depend on cells called sensory receptors.

Sensory Receptors

A sensory receptor is a specialized nerve cell that responds to a stimulus in the internal or external environment by generating a nerve impulse. The nerve impulse then travels along the sensory (afferent) nerve to the central nervous system for processing and to form a response.

There are several different types of sensory receptors that respond to different kinds of stimuli:

- Mechanoreceptors respond to mechanical forces, such as pressure, roughness, vibration, and stretching. Most mechanoreceptors are found in the skin and are needed for the sense of touch. Mechanoreceptors are also found in the inner ear, where they are needed for the senses of hearing and balance.

- Thermoreceptors respond to variations in temperature. They are found mostly in the skin and detect temperatures that are above or below body temperature.

- Nociceptors respond to potentially damaging stimuli, which are generally perceived as pain. They are found in internal organs, as well as on the surface of the body. Different nociceptors are activated depending on the particular stimulus. Some detect damaging heat or cold, others detect excessive pressure, and still others detect painful chemicals (such as very hot spices in food).

- Photoreceptors detect and respond to light. Most photoreceptors are found in the eyes and are needed for the sense of vision.

- Chemoreceptors respond to certain chemicals. They are found mainly in taste buds on the tongue — where they are needed for the sense of taste — and in nasal passages, where they are needed for the sense of smell.

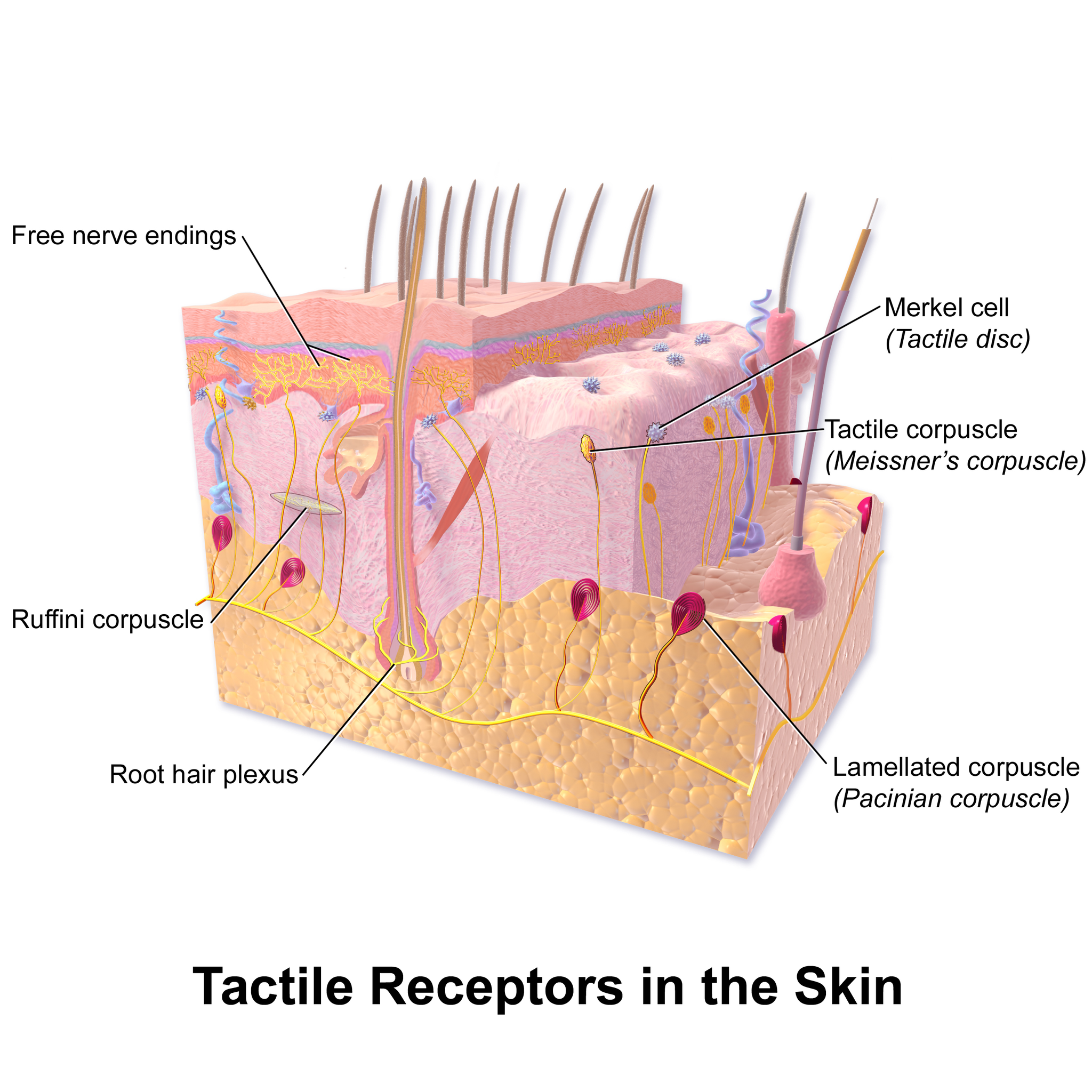

Touch

Touch is the ability to sense pressure, vibration, temperature, pain, and other tactile stimuli. These types of stimuli are detected by mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and nociceptors all over the body, most noticeably in the skin. These receptors are especially concentrated on the tongue, lips, face, palms of the hands, and soles of the feet. Various types of tactile receptors in the skin are shown in Figure 8.7.2.

Vision

Vision (or sight) is the ability to sense light and see. The eye is the special sensory organ that collects and focuses light and forms images. The eye, however, is not sufficient for us to see. The brain also plays a necessary role in vision. Vision is our primary sense and more than 50 per cent of the cerebral cortex is devoted to processing visual information. A person with normal colour vision can differentiate between hundreds of thousands of different colours, hues, and shades.

How the Eye Works

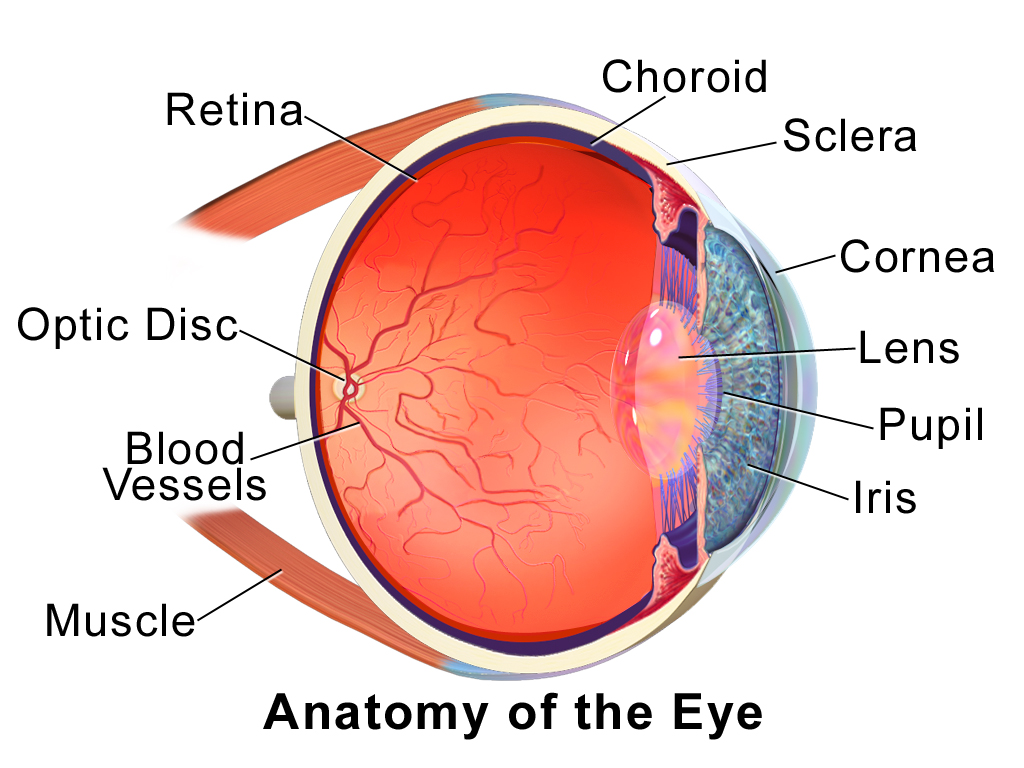

Figure 8.7.4 (below) shows the anatomy of the human eye in cross-section. The eye gathers and focuses light to form an image, and then changes the image to nerve impulses that travel to the brain. The eye’s functions are summarized in the following steps.

- Light passes first through the cornea, which is a clear outer layer that protects the eye and helps to focus the light by refracting (or bending) it.

- Next, light enters the interior of the eye through an opening called the pupil. The size of this opening is controlled by the coloured part of the eye (called the iris), which adjusts the size based on the brightness of the light. The iris causes the pupil to narrow in bright light and widen in dim light. Filling the space between the cornea and the iris is a semi-gelatinous fluid called aqueous humor and functions to maintain the shape of the eye.

- The light then passes through the lens, which refracts the light even more and focuses it on the retina at the back of the eye, as an inverted image. Sitting behind the lens is a gelatinous fluid called vitreous humor, which functions to maintain the shape of the eye.

- The retina contains two types of photoreceptors: rod and cone cells . Rod cells, which are found mainly in all areas of the retina other than the very center, are particularly sensitive to low levels of light. Cone cells, which are found mainly in the center of the retina, are sensitive to light of different colours, and allow colour vision. The rods and cones convert the light that strikes them to nerve impulses.

- The nerve impulses from the rods and cones travel to the optic nerve via the optic disc (also known as the optic nerve), which is a circular area at the back of the eye where the optic nerve connects to the retina.

Colour Vision

Humans have colour vision because we have three types of cone cells: blue, green and red. Each of these types of cone cell detects a specific wavelength of light, for which they are named. The combined stimulus is then perceived as a specific colour, based on the ratio of the amount stimulus coming from each of the three types of cone cells. Do you know what else uses these same three pieces of information to communicate colour? Your computer monitor! When working in a creative program, such as Paint, these three reference points of red (R), green (G), and blue (B), can be used to create any of the million colours the human eye can perceive, as illustrated in Figure 8.7.5. Take a look at each of the numerical values for red, green, and blue and what colour their combined values create:

Figure 8.7.5 RGB colours.

Role of the Brain in Vision

The optic nerves from both eyes meet and cross just below the bottom of the hypothalamus in the brain. The information from both eyes is sent to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe of the cerebrum, which is part of the cerebral cortex. The visual cortex is the largest system in the human brain, and is responsible for processing visual images. It interprets messages from both eyes and “tells” us what we are seeing.

Vision Problems

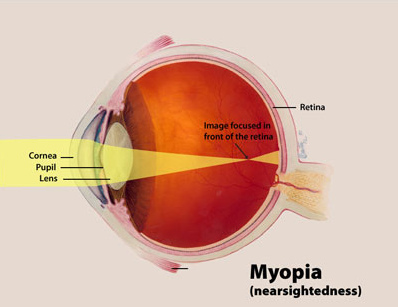

Vision problems are very common. Two of the most common are myopia and hyperopia, and they often start in childhood or adolescence. Another common problem, called presbyopia, occurs in most people, beginning in middle adulthood. In all three conditions, the eyes fail to focus images correctly on the retina, resulting in blurred vision.

Myopia

Myopia (or nearsightedness) occurs when the light that comes into the eye does not directly focus on the retina, but in front of it, as shown in Figure 8.7.7. As a result, distant objects may appear out of focus, but the focus of close objects is not affected. Myopia may occur because the eyeball is elongated from front to back, or because the cornea is too curved. Myopia can be corrected with the use of corrective lenses, either eyeglasses or contact lenses. Myopia can also be corrected by refractive surgery performed with a laser.

Hyperopia

Hyperopia (or farsightedness) happens when the light coming into the eye does not directly focus on the retina but behind it, as shown in Figure 8.7.8. This causes close objects to appear out of focus, but does not affect the focus of distant objects. Hyperopia may occur because the eyeball is too short from front to back, or because the lens is not curved enough. Hyperopia can be corrected through the use of corrective lenses or laser surgery.

Presbyopia

Presbyopia is a vision problem associated with aging, in which the eye gradually loses its ability to focus on close objects. The precise origin of presbyopia is not known for certain, but evidence suggests that the lens may become less elastic with age, causing the muscles that control the lens to lose power as people grow older. The first signs of presbyopia — eyestrain, difficulty seeing in dim light, problems focusing on small objects and fine print — are usually first noticed between the ages of 40 and 50. Most older people with this problem use corrective lenses to focus on close objects, because surgical procedures to correct presbyopia have not been as successful as those for myopia and hyperopia.

Hearing

Hearing is the ability to sense sound waves, and the ear is the organ that senses sound. Sound waves enter the ear through the ear canal and travel to the eardrum (see the diagram of the ear Figure 8.7.9). The sound waves strike the eardrum, and make it vibrate. The vibrations then travel through the three tiny bones (incus, malleus and stapes) of the middle ear, which amplify the vibrations. From the middle ear, the vibrations pass to the cochlea in the inner ear. The cochlea is a coiled tube filled with liquid. The liquid moves in response to the vibrations, causing tiny hair cells(which are mechanoreceptors) lining the cochlea to bend. In response, the hair cells send nerve impulses to the auditory nerve, which carries the impulses to the brain. The brain interprets the impulses and “tells” us what we are hearing.

Balance

The ears are also responsible for the sense of balance. Balance is the ability to sense and maintain an appropriate body position. The semicircular canals inside the ear (see the figure above) contain fluid that moves when the head changes position. Tiny hairs lining the semicircular canals sense movement of the fluid. In response, they send nerve impulses to the vestibular nerve, which carries the impulses to the brain. The brain interprets the impulses and sends messages to the peripheral nervous system, which triggers contractions of skeletal muscles as needed to maintain balance.

Taste and Smell

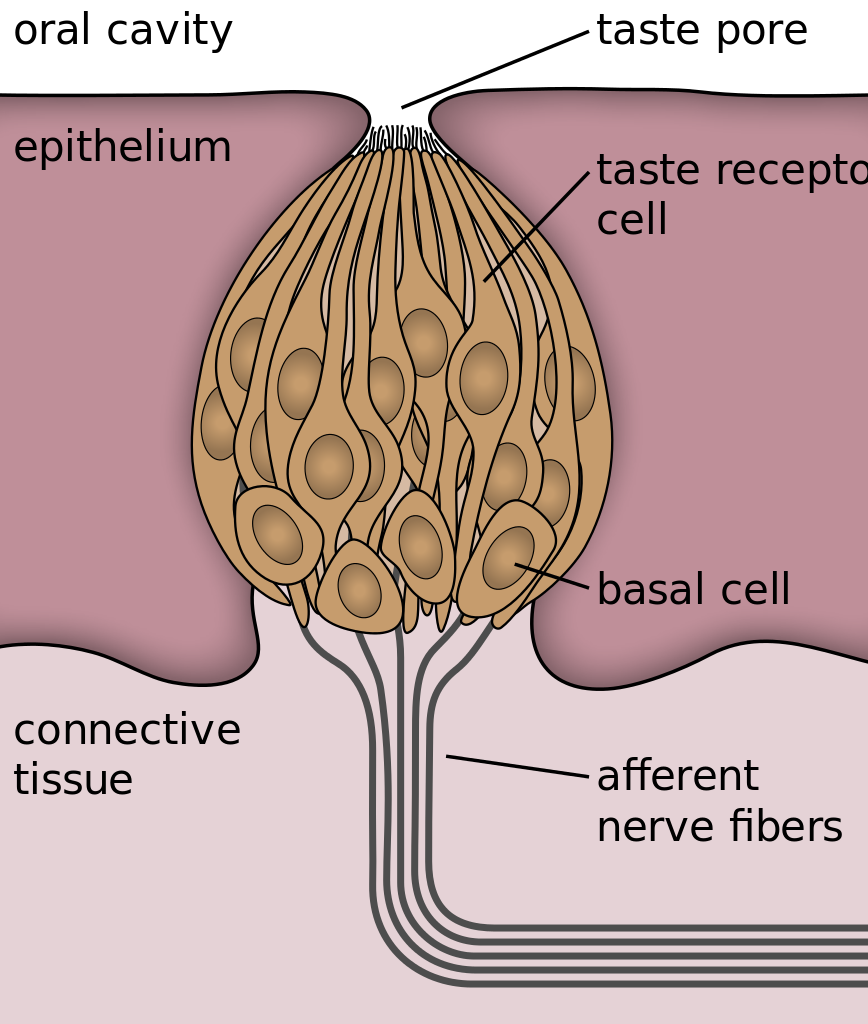

Taste and smell are both abilities to sense chemicals, so both taste and olfactory (odor) receptors are chemoreceptors. Both types of chemoreceptors send nerve impulses to the brain along sensory nerves, and the brain “tells” us what we are tasting or smelling.

Taste receptors are found in tiny bumps on the tongue called taste buds.You can see a diagram of a taste receptor cell and related structures in Figure 8.7.10. Taste receptor cells make contact with chemicals in food through tiny openings called taste pores. When certain chemicals bind with taste receptor cells, it generates nerve impulses that travel through afferent nerves to the CNS. There are separate taste receptors for sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and meaty tastes. The meaty — or savory — taste is called umami.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

The most common cause of blindness in the Western hemisphere is age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Approximately 1.4 million people in Canada have this type of blindness, and 196 million people are affected worldwide and is expected to increase to 288 millions people by the year 2040. At present, there is no cure for AMD. The disease occurs with the death of a layer of cells called retinal pigment epithelium, which normally provides nutrients and other support to the macula of the eye. The macula is an oval-shaped pigmented area near the center of the retina that is specialized for high visual acuity and has the retina’s greatest concentration of cones. When the epithelial cells die and the macula is no longer supported or nourished, the macula also starts to die. Patients experience a black spot in the center of their vision, and as the disease progresses, the black spot grows outward. Patients eventually lose the ability to read and even to recognize familiar faces before developing total blindness.

In 2016, a landmark surgery was performed as a trial on a patient with severe AMD. In the first ever operation of its kind, Dr. Pete Coffey of the University of London implanted a tiny patch of cells behind the retina in each of the patient’s eyes. The cells were retinal pigmented epithelial cells that had been grown in a lab from stem cells, which are undifferentiated cells that can develop into other cell types. Within six months of the operation, the new cells were still surviving, and the doctor was hopeful that the patient’s vision loss would stop and even be reversed. At that point, several other operations had already been planned to test the new procedure. If these cases are a success, Dr. Coffey predicts that the surgery will become as routine as cataract surgery, and that it will prevent millions of patients from losing their vision.

8.7 Summary

- The human body has two major types of senses: special senses and general senses. Special senses have specialized sense organs and include vision (eyes), hearing (ears), balance (ears), taste (tongue), and smell (nasal passages). General senses are all associated with touch and lack special sense organs. Touch receptors are found throughout the body, but particularly in the skin.

- All senses depend on sensory receptor cells to detect sensory stimuli and transform them into nerve impulses. Types of sensory receptors include mechanoreceptors (mechanical forces), thermoreceptors (temperature), nociceptors (pain), photoreceptors (light), and chemoreceptors (chemicals).

- Touch is the ability to sense pressure, vibration, temperature, pain, and other tactile stimuli. The skin includes several different types of touch receptor cells.

- Vision is the ability to sense light and see. The eye is the special sensory organ that collects and focuses light, forms images, and changes them to nerve impulses. Optic nerves send information from the eyes to the brain, which processes the visual information and “tells” us what we are seeing.

- Common vision problems include myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), and presbyopia (age-related decline in close vision). Vision problems can be corrected with lenses (eyeglasses or contacts) or — in many cases — with laser surgery.

- Hearing is the ability to sense sound waves, and the ear is the organ that senses sound. It changes sound waves to vibrations that trigger nerve impulses, which travel to the brain through the auditory nerve. The brain processes the information and “tells” us what we are hearing.

- The ear is also the organ responsible for the sense of balance, which is the ability to sense and maintain an appropriate body position. The ears send impulses about head position to the brain, which sends messages to skeletal muscles via the peripheral nervous system. The muscles respond by contracting to maintain balance.

- Taste and smell are both abilities to sense chemicals. Taste receptors in taste buds on the tongue sense chemicals in food, while olfactory receptors in the nasal passages sense chemicals in the air. Sense of smell contributes significantly to sense of taste.

8.7 Review Questions

-

- Compare and contrast special senses and general senses.

- What are sensory receptors?

-

- Describe the range of tactile stimuli detected in the sense of touch.

- Explain how the eye collects and focuses light to form an image, and how it converts it to nerve impulses.

- Identify two common vision problems,along with their causes and their effects on vision.

-

- Explain how structures of the ear collect and amplify sound waves and transform them to nerve impulses.

- What role does the ear play in balance? Which structures of the ear are involved in balance?

- Describe two ways that the body senses chemicals. What are the special sense organs involved in these senses?

- Explain why your skin can detect different types of stimuli, such as pressure and temperature.

- Is sensory information sent to the central nervous system via efferent or afferent nerves?

- Identify a mechanoreceptor used in two different human senses. Describe the type of mechanical stimuli that each detects.

- If a person is blind, but their retina is functioning properly, where do you think the damage might be? Explain your answer.

- When you see colours, what receptor cells are activated? Where are these receptors located? What lobe of the brain is primarily used to process visual information?

- The auditory nerve carries _______________.

-

-

- smell information

- taste information

- balance information

- sound information

-

8.7 Explore More

What color is Tuesday? Exploring synesthesia – Richard E. Cytowic, TED-Ed, 2013.

What Is Vertigo & Why Do We Get It?, Seeker, 2016.

How do animals see in the dark? – Anna Stöckl, TED-Ed, 2016.

What are those floaty things in your eye? – Michael Mauser, TED-Ed, 2014.

Attributions

Figure 8.7.1

Bee Stereogram by Be Mosaic on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/) license.

Figure 8.7.2

Skin_TactileReceptors by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 8.7.3

Macro shot photograph of someone’s right eye [photo] by Jordan Whitfield on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 8.7.4

EyeAnatomy_01 by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 8.7.5

RGB colours [screenshots] from Microsoft Paint.

Figure 8.7.6

Through the reading glasses [photo] by Dmitry Ratushny on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 8.7.7

Myopia_Diagram by National Eye Institute/ National Institutes of Health on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 8.7.8

Hyperopia by National Institute of Health/NIH on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.7.9

AnatomyHumanEar by unknown author from Occupational Safety & Health Administration on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.7.10

Taste_bud_2_eng.svg by Jonas Töle on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/deed.en).

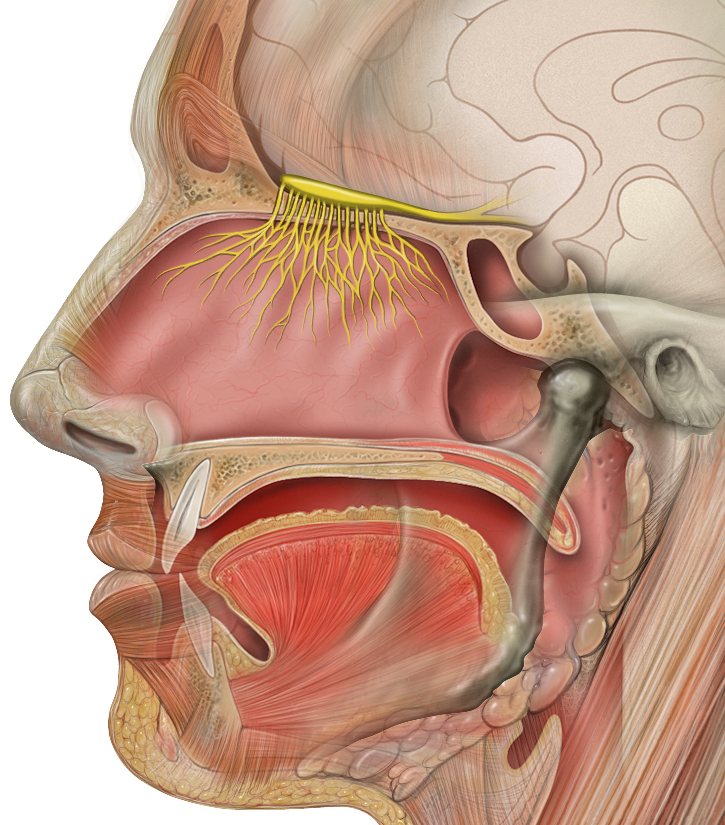

Figure 8.7.11

Head_olfactory_nerve by Patrick.lynch, medical illustrator on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en) license.

References

Age-Related Macular Degeneration. (n.d.). WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/eye-health/macular-degeneration/age-related-macular-degeneration-overview#3 (Reviewed by Alan Kozarsky, MD on October 26, 2019)

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

da Cruz, L., Fynes, K., Georgiadis, O. et al. (2018, March 19). Phase 1 clinical study of an embryonic stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelium patch in age-related macular degeneration. Natural Biotechnology, 36, 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4114

File:Eye Diagram without text.gif. (2018, February 9). Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Eye_Diagram_without_text.gif&oldid=286008241 (original image from National Eye Institute – modified by User:Nordelch) [public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)]

Occupational Health and Safety Administration. (n.d.). Figure 7. Anatomy of the human ear [diagram]. In OSHA Technical Manual (Section III, Chapter 5 – Noise). United States Department of Labour [online]. https://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/new_noise/

Seeker. (2016, March 18). What is vertigo & why do we get it? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UL8YSLhqa5U&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2013, June 10). What color is Tuesday? Exploring synesthesia – Richard E. Cytowic. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkRbebvoYqI&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2014, December 1). What are those floaty things in your eye? – Michael Mauser. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y6e_m9iq-4Q&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2016, August 25). How do animals see in the dark? – Anna Stöckl. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3CjTU7TaNA&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Getting Rid of Wastes

The many chimneys on these houses are one way that the inhabitants of the home get rid of the wastes they produce. The chimneys expel waste gases that are created when they burn fuel in their furnace or fireplace. Think about the other wastes that people create in their homes and how we dispose of them. Solid trash and recyclables may go to the curb in a trash can, or in a recycling bin for pick up and transport to a landfill or recycling centre. Wastewater from sinks, showers, toilets, and the washing machine goes into a main sewer pipe and out of the house to join the community’s sanitary sewer system.

Like a busy home, your body also produces a lot of wastes that must be eliminated. Like a home, the way your body gets rid of wastes depends on the nature of the waste products. Some human body wastes are gases, some are solids, and some are in a liquid state. Getting rid of body wastes is called excretion, and there are a number of different organs of excretion in the human body.

Excretion

Excretion is the process of removing wastes and excess water from the body. It is an essential process in all living things, and it is one of the major ways the human body maintains homeostasis. It also helps prevent damage to the body. Wastes include by-products of metabolism — some of which are toxic — and other non-useful materials, such as used up and broken down components. Some of the specific waste products that must be excreted from the body include carbon dioxide from cellular respiration, ammonia and urea from protein catabolism, and uric acid from nucleic acid catabolism.

Excretory Organs

Organs of excretion include the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys (see Figure 16.2.2). Together, these organs make up the excretory system. They all excrete wastes, but they don’t work together in the same way that organs do in most other body systems. Each of the excretory organs “does its own thing” more-or-less independently of the others, but all are necessary to successfully excrete the full range of wastes from the human body.

Figure 16.2.2 Internal organs of excretion are identified in this illustration. They include the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys.

Skin

The skin is part of the integumentary system, but it also plays a role in excretion through the production of sweat by sweat glands in the dermis. Although the main role of sweat production is to cool the body and maintain temperature homeostasis, sweating also eliminates excess water and salts, as well as a small amount of urea. When sweating is copious, as in Figure 16.2.3, ingestion of salts and water may be helpful to maintain homeostasis in the body.

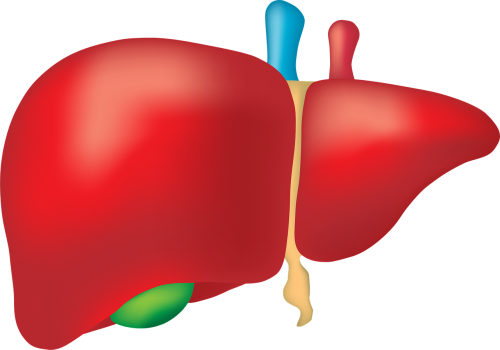

Liver

The liver (shown in Figure 16.2.4) has numerous major functions, including secreting bile for digestion of lipids, synthesizing many proteins and other compounds, storing glycogen and other substances, and secreting endocrine hormones. In addition to all of these functions, the liver is a very important organ of excretion. The liver breaks down many substances in the blood, including toxins. For example, the liver transforms ammonia — a poisonous by-product of protein catabolism — into urea, which is filtered from the blood by the kidneys and excreted in urine. The liver also excretes in its bile the protein bilirubin, a byproduct of hemoglobin catabolism that forms when red blood cells die. Bile travels to the small intestine and is then excreted in feces by the large intestine.

Large Intestine

The large intestine is an important part of the digestive system and the final organ in the gastrointestinal tract. As an organ of excretion, its main function is to eliminate solid wastes that remain after the digestion of food and the extraction of water from indigestible matter in food waste. The large intestine also collects wastes from throughout the body. Bile secreted into the gastrointestinal tract, for example, contains the waste product bilirubin from the liver. Bilirubin is a brown pigment that gives human feces its characteristic brown colour.

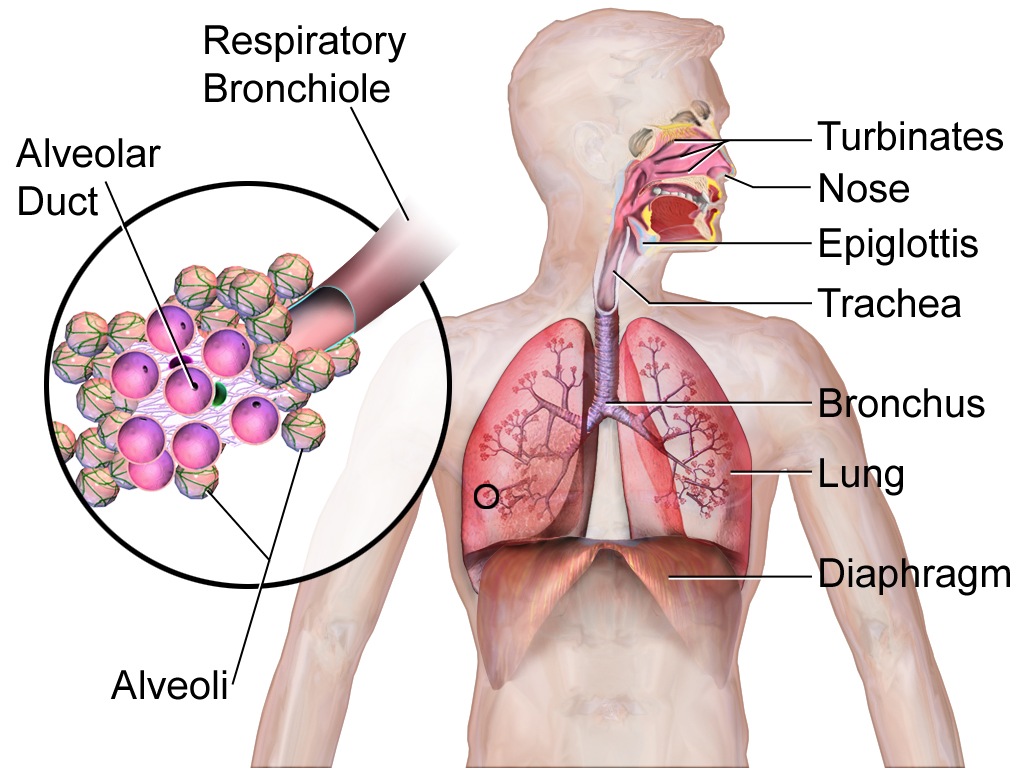

Lungs

The lungs are part of the respiratory system (shown in Figure 16.2.5), but they are also important organs of excretion. They are responsible for the excretion of gaseous wastes from the body. The main waste gas excreted by the lungs is carbon dioxide, which is a waste product of cellular respiration in cells throughout the body. Carbon dioxide is diffused from the blood into the air in the tiny air sacs called alveoli in the lungs (shown in the inset diagram). By expelling carbon dioxide from the blood, the lungs help maintain acid-base homeostasis. In fact, it is the pH of blood that controls the rate of breathing. Water vapor is also picked up from the lungs and other organs of the respiratory tract as the exhaled air passes over their moist linings, and the water vapor is excreted along with the carbon dioxide. Trace levels of some other waste gases are exhaled, as well.

Kidneys

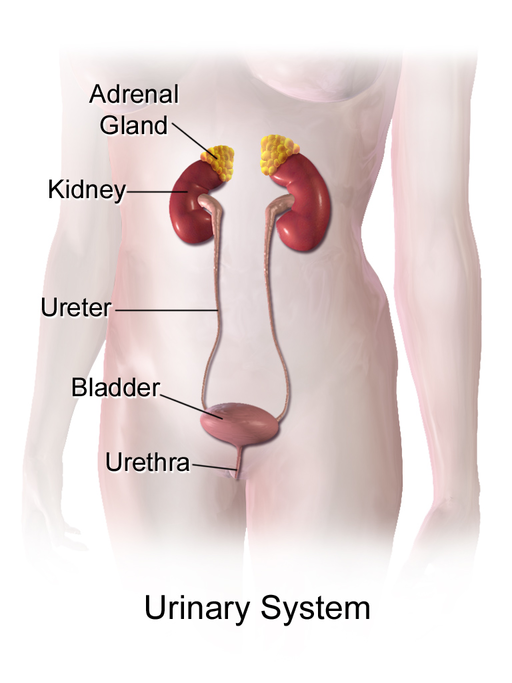

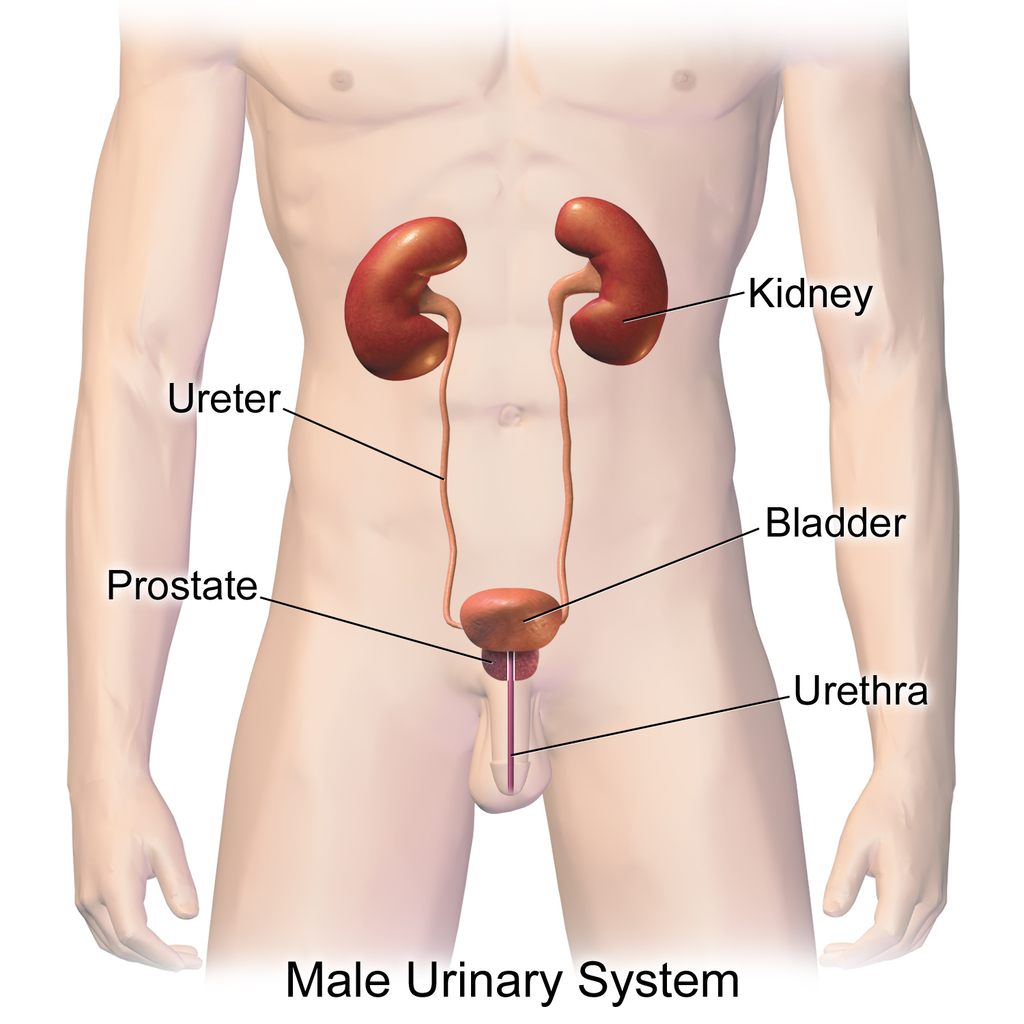

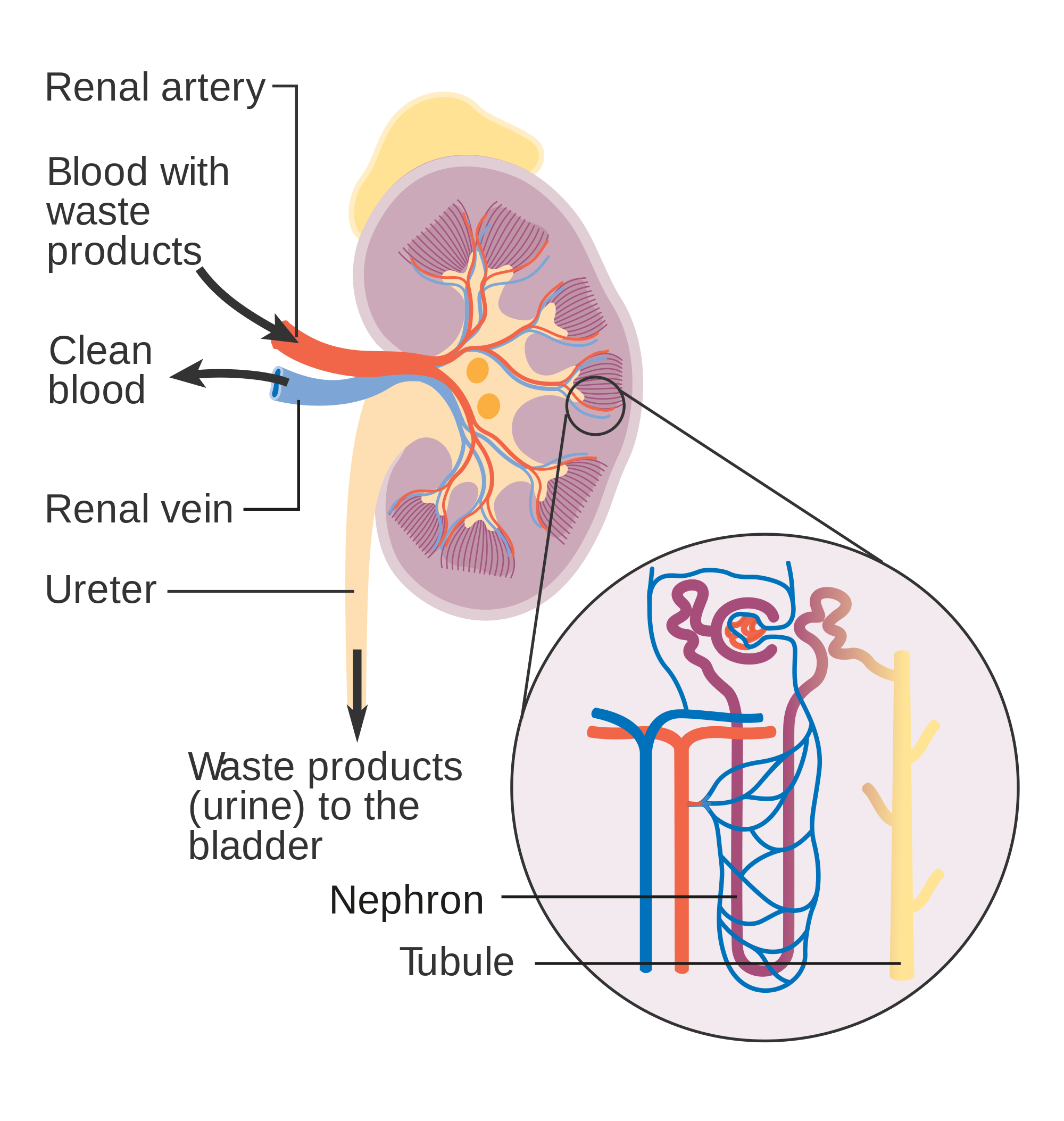

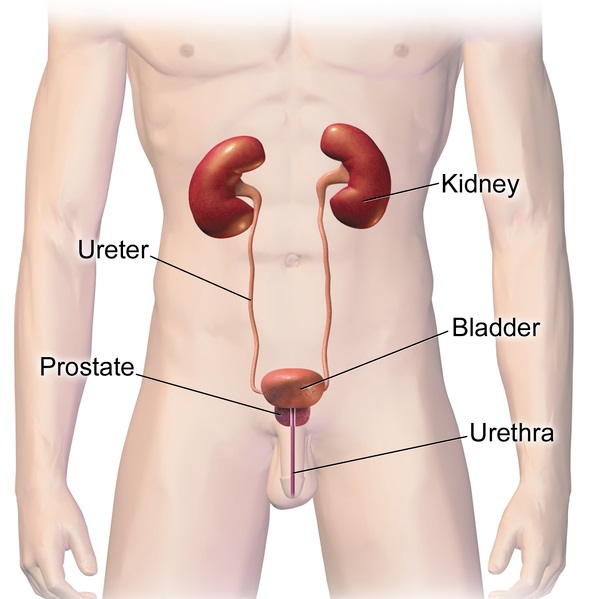

The paired kidneys are often considered the main organs of excretion. The primary function of the kidneys is the elimination of excess water and wastes from the bloodstream by the production of the liquid waste known as urine. The main structural and functional units of the kidneys are tiny structures called nephrons. Nephrons filter materials out of the blood, return to the blood what is needed, and excrete the rest as urine. As shown in Figure 16.2.6, the kidneys are organs of the urinary system, which also includes the ureters, bladder, and urethra — organs that transport, store, and eliminate urine, respectively.

By producing and excreting urine, the kidneys play vital roles in body-wide homeostasis. They maintain the correct volume of extracellular fluid, which is all the fluid in the body outside of cells, including the blood and lymph. The kidneys also maintain the correct balance of salts and pH in extracellular fluid. In addition, the kidneys function as endocrine glands, secreting hormones into the blood that control other body processes. You can read much more about the kidneys in section 16.4 Kidneys.

16.2 Summary

- Excretion is the process of removing wastes and excess water from the body. It is an essential process in all living things and a major way the human body maintains homeostasis.

- Organs of excretion include the skin, liver, large intestine, lungs, and kidneys. All of them excrete wastes, and together they make up the excretory system.

- The skin plays a role in excretion through the production of sweat by sweat glands. Sweating eliminates excess water and salts, as well as a small amount of urea, a byproduct of protein catabolism.

- The liver is a very important organ of excretion. The liver breaks down many substances in the blood, including toxins. The liver also excretes bilirubin — a waste product of hemoglobin catabolism — in bile. Bile then travels to the small intestine, and is eventually excreted in feces by the large intestine.

- The main excretory function of the large intestine is to eliminate solid waste that remains after food is digested and water is extracted from the indigestible matter. The large intestine also collects and excretes wastes from throughout the body, including bilirubin in bile.

- The lungs are responsible for the excretion of gaseous wastes, primarily carbon dioxide from cellular respiration in cells throughout the body. Exhaled air also contains water vapor and trace levels of some other waste gases.

- The paired kidneys are often considered the main organs of excretion. Their primary function is the elimination of excess water and wastes from the bloodstream by the production of urine. The kidneys contain tiny structures called nephrons that filter materials out of the blood, return to the blood what is needed, and excrete the rest as urine. The kidneys are part of the urinary system, which also includes the ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra.

16.2 Review Questions

- What is excretion, and what is its significance?

-

- Describe the excretory functions of the liver.

- What are the main excretory functions of the large intestine?

- List organs of the urinary system.

- Describe the physical states in which the wastes from the human body are excreted.

- Give one example of why ridding the body of excess water is important.

- What gives feces its brown colour? Why is that substance produced?

16.2 Explore More

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erMCADOJcHk&feature=youtu.be

Why Can We Regrow A Liver (But Not A Limb)? MITK12Videos, 2015.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SeK0zFB9yHg&feature=youtu.be

Are Sports Drinks Good For You? | Fit or Fiction, POPSUGAR Fitness, 2014.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fctH_1NuqCQ&feature=youtu.be

Why do we sweat? - John Murnan, TED-Ed, 2018.

Attributions

Figure 16.2.1

Chimneys/ Kingston upon Hull, England [photo] by Angela Baker on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 16.2.2

- Sweat or rain? by Kullez on Flickr is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/).

- Kidney front - white from www.medicalgraphics.de is used under a CC BY-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/) license.

- File:Liver Cirrhosis.png by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

- File:Human lungs.png by Sharanyaudupa on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en) license.

- Tags: Offal Marking Medical Intestine Liver by Elionas2 on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay license (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.2.3

gym_room_fitness_equipment_cardiovascular_exercise_elliptical_bike_cardio_training_sports_equipment_bodybuilding-825364 from Pxhere is used under a CC0 1.0 Universal public domain dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

Figure 16.2.4

Tags: Liver Organ Anatomy by zachvanstone8 on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.2.5

Lung_and_diaphragm by Terese Winslow/ National Cancer Institute on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.2.6

512px-Urinary_System_(Female) by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

MITK12Videos. (2015, June 4). Why can we regrow a liver (but not a limb)? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erMCADOJcHk&feature=youtu.be

POPSUGAR Fitness. (2014, February 7). Are sports drinks good for you? | Fit or Fiction. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SeK0zFB9yHg&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2018, May 15). Why do we sweat? - John Murnan. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fctH_1NuqCQ&feature=youtu.be

As per caption

Image shows a detailed labelled diagram of a kidney. There is a tough outer layer called the capsule. The cortex contains blood vessels and the medulla contains nephrons. The renal artery brings blood from the heart to the kidney, and this blood is returned to the heart via the renal vein.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Vampires

From Bram Stoker’s famous novel about Count Dracula, to films such as Van Helsing and the Twilight Saga, fantasies featuring vampires (like the one in Figure 14.5.1) have been popular for decades. Vampires, in fact, are found in centuries-old myths from many cultures. In such myths, vampires are generally described as creatures that drink blood — preferably of the human variety — for sustenance. Dracula, for example, is based on Eastern European folklore about a human who attains immortality (and eternal damnation) by drinking the blood of others.

What Is Blood?

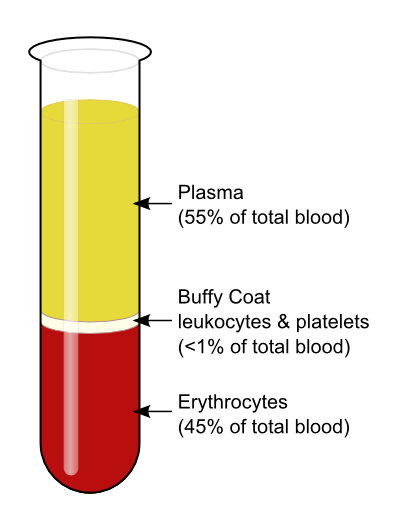

The average adult body contains between 4.7 and 5.7 litres of blood. More than half of that amount is fluid. Most of the rest of that amount consists of blood cells. The relative amounts of the various components in blood are illustrated in Figure 14.5.2. The components are also described in detail below.

Blood is a fluid connective tissue that circulates throughout the body through blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. What makes blood so special that it features in widespread myths? Although blood accounts for less than 10% of human body weight, it is quite literally the elixir of life. As blood travels through the vessels of the cardiovascular system, it delivers vital substances (such as nutrients and oxygen) to all of the cells, and carries away their metabolic wastes. It is no exaggeration to say that without blood, cells could not survive. Indeed, without the oxygen carried in blood, cells of the brain start to die within a matter of minutes.

Functions of Blood

Blood performs many important functions in the body. Major functions of blood include:

- Supplying tissues with oxygen, which is needed by all cells for aerobic cellular respiration.

- Supplying cells with nutrients, including glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids.

- Removing metabolic wastes from cells, including carbon dioxide, urea, and lactic acid.

- Helping to defend the body from pathogens and other foreign substances.

- Forming clots to seal broken blood vessels and stop bleeding.

- Transporting hormones and other messenger molecules.

- Regulating the pH of the body, which must be kept within a narrow range (7.35 to 7.45).

- Helping regulate body temperature (through vasoconstriction and vasodilation).

Blood Plasma

Plasma is the liquid component of human blood. It makes up about 55% of blood by volume. It is about 92% water, and contains many dissolved substances. Most of these substances are proteins, but plasma also contains trace amounts of glucose, mineral ions, hormones, carbon dioxide, and other substances. In addition, plasma contains blood cells. When the cells are removed from plasma, as in Figure 14.5.2 above, the remaining liquid is clear but yellow in colour.

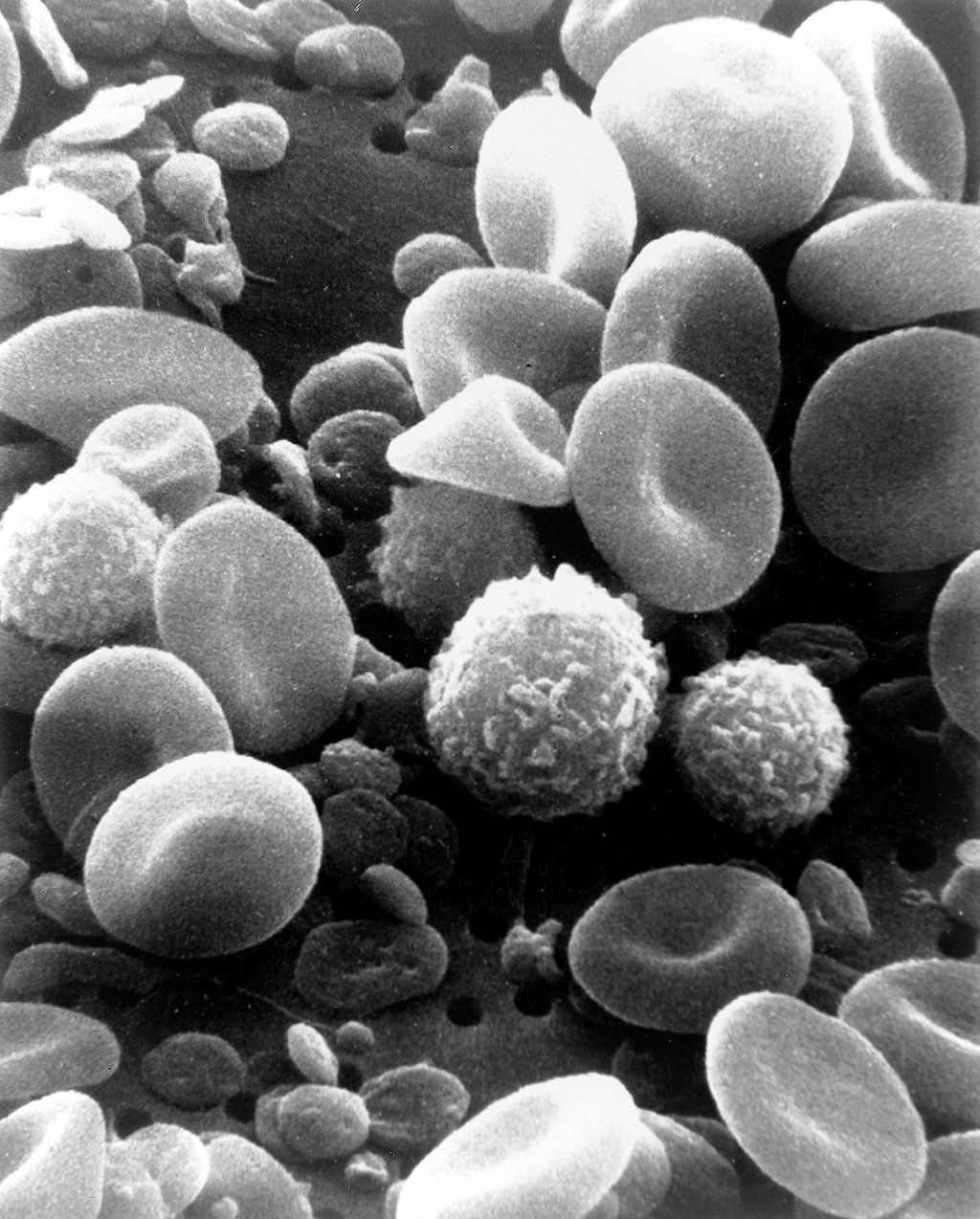

Blood Cells

The cells in blood include erythrocytes, leukocytes, and thrombocytes. These different types of blood cells are shown in the photomicrograph (Figure 14.5.3) and described in the sections that follow.

Erythrocytes

The most numerous cells in blood are red blood cells, also called erythrocytes. One microlitre of blood contains between 4.2 and 6.1 million red blood cells, and red blood cells make up about 25% of all the cells in the human body. The cytoplasm of a mature erythrocyte is almost completely filled with hemoglobin, the iron-containing protein that binds with oxygen and gives the cell its red colour. In order to provide maximum space for hemoglobin, mature erythrocytes lack a cell nucleus and most organelles. They are little more than sacks of hemoglobin.

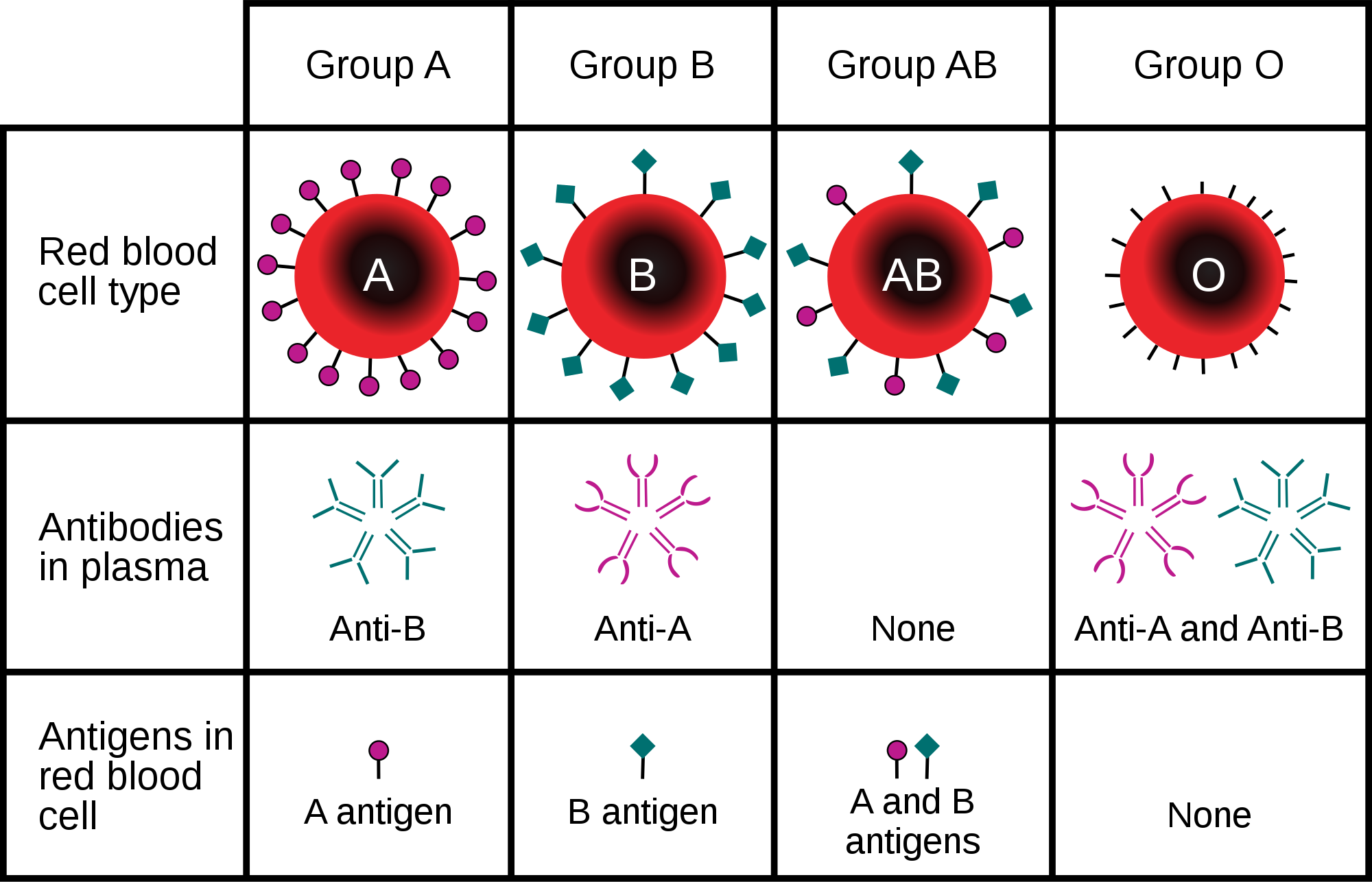

Erythrocytes also carry proteins called antigens that determine blood type. Blood type is a genetic characteristic. The best known human blood type systems are the ABO and Rhesus systems.

- In the ABO system, there are two common antigens, called antigen A and antigen B. There are four ABO blood types, A (only A antigen), B (only B antigen), AB (both A and B antigens), and O (neither A nor B antigen). The ABO antigens are illustrated in Figure 14.5.4.

- In the Rhesus system, there is just one common antigen. A person may either have the antigen (Rh+) or lack the antigen (Rh-).

Blood type is important for medical reasons. A person who needs a blood transfusion must receive blood of a compatible type. Blood that is compatible lacks antigens that the patient's own blood also lacks. For example, for a person with type A blood (no B antigen), compatible types include any type of blood that lacks the B antigen. This would include type A blood or type O blood, but not type AB or type B blood. If incompatible blood is transfused, it may cause a potentially life-threatening reaction in the patient’s blood.

Leukocytes

Leukocytes (also called white blood cells) are cells in blood that defend the body against invading microorganisms and other threats. There are far fewer leukocytes than red blood cells in blood. There are normally only about 1,000 to 11,000 white blood cells per microlitre of blood. Unlike erythrocytes, leukocytes have a nucleus. White blood cells are part of the body’s immune system. They destroy and remove old or abnormal cells and cellular debris, as well as attack pathogens and foreign substances. There are five main types of white blood cells, which are described in Table 14.5.1: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. The five types differ in their specific immune functions.

| Type of Leukocyte | Per cent of All Leukocytes | Main Function(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil | 62% | Phagocytize (engulf and destroy) bacteria and fungi in blood. |

| Eosinophil | 2% | Attack and kill large parasites; carry out allergic responses. |

| Basophil | less than 1% | Release histamines in inflammatory responses. |

| Lymphocyte | 30% | Attack and destroy virus-infected and tumor cells; create lasting immunity to specific pathogens. |

| Monocyte | 5% | Phagocytize pathogens and debris in tissues. |

Thrombocytes

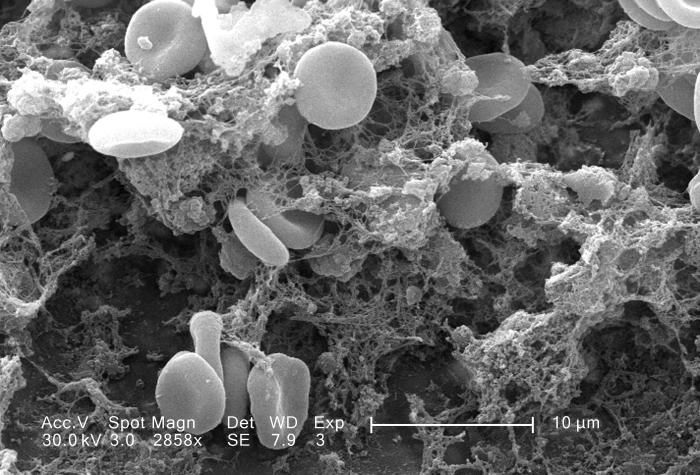

Thrombocytes, also called platelets, are actually cell fragments. Like erythrocytes, they lack a nucleus and are more numerous than white blood cells. There are about 150 thousand to 400 thousand thrombocytes per microlitre of blood.

The main function of thrombocytes is blood clotting, or coagulation. This is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a plug in a damaged blood vessel. If blood clotting is successful, it results in hemostasis, which is the cessation of blood loss from the damaged vessel. A blood clot consists of both platelets and proteins, especially the protein fibrin. You can see a scanning electron microscope photomicrograph of a blood clot in Figure 14.5.5.

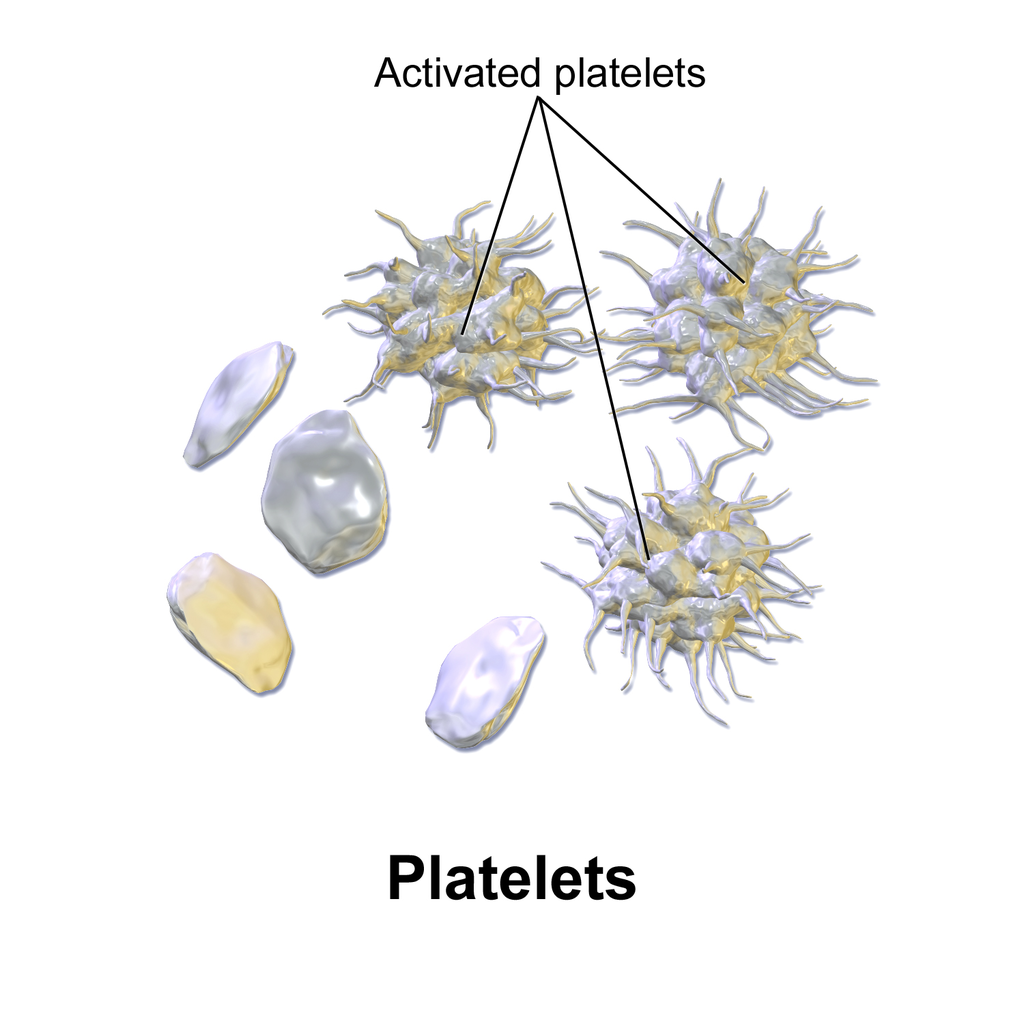

Coagulation begins almost instantly after an injury occurs to the endothelium of a blood vessel. Thrombocytes become activated and change their shape from spherical to star-shaped, as shown in Figure 14.5.6. This helps them aggregate with one another (stick together) at the site of injury to start forming a plug in the vessel wall. Activated thrombocytes also release substances into the blood that activate additional thrombocytes and start a sequence of reactions leading to fibrin formation. Strands of fibrin crisscross the platelet plug and strengthen it, much as rebar strengthens concrete.

Formation and Degradation of Blood Cells

Blood is considered a connective tissue, because blood cells form inside bones. All three types of blood cells are made in red marrow within the medullary cavity of bones in a process called hematopoiesis. Formation of blood cells occurs by the proliferation of stem cells in the marrow. These stem cells are self-renewing — when they divide, some of the daughter cells remain stem cells, so the pool of stem cells is not used up. Other daughter cells follow various pathways to differentiate into the variety of blood cell types. Once the cells have differentiated, they cannot divide to form copies of themselves.

Eventually, blood cells die and must be replaced through the formation of new blood cells from proliferating stem cells. After blood cells die, the dead cells are phagocytized (engulfed and destroyed) by white blood cells, and removed from the circulation. This process most often takes place in the spleen and liver.

Blood Disorders

Many human disorders primarily affect the blood. They include cancers, genetic disorders, poisoning by toxins, infections, and nutritional deficiencies.

- Leukemia is a group of cancers of the blood-forming tissues in the bone marrow. It is the most common type of cancer in children, although most cases occur in adults. Leukemia is generally characterized by large numbers of abnormal leukocytes. Symptoms may include excessive bleeding and bruising, fatigue, fever, and an increased risk of infections. Leukemia is thought to be caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- Hemophilia refers to any of several genetic disorders that cause dysfunction in the blood clotting process. People with hemophilia are prone to potentially uncontrollable bleeding, even with otherwise inconsequential injuries. They also commonly suffer bleeding into the spaces between joints, which can cause crippling.

- Carbon monoxide poisoning occurs when inhaled carbon monoxide (in fumes from a faulty home furnace or car exhaust, for example) binds irreversibly to the hemoglobin in erythrocytes. As a result, oxygen cannot bind to the red blood cells for transport throughout the body, and this can quickly lead to suffocation. Carbon monoxide is extremely dangerous, because it is colourless and odorless, so it cannot be detected in the air by human senses.

- HIV is a virus that infects certain types of leukocytes and interferes with the body’s ability to defend itself from pathogens and other causes of illness. HIV infection may eventually lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). AIDS is characterized by rare infections and cancers that people with a healthy immune system almost never acquire.

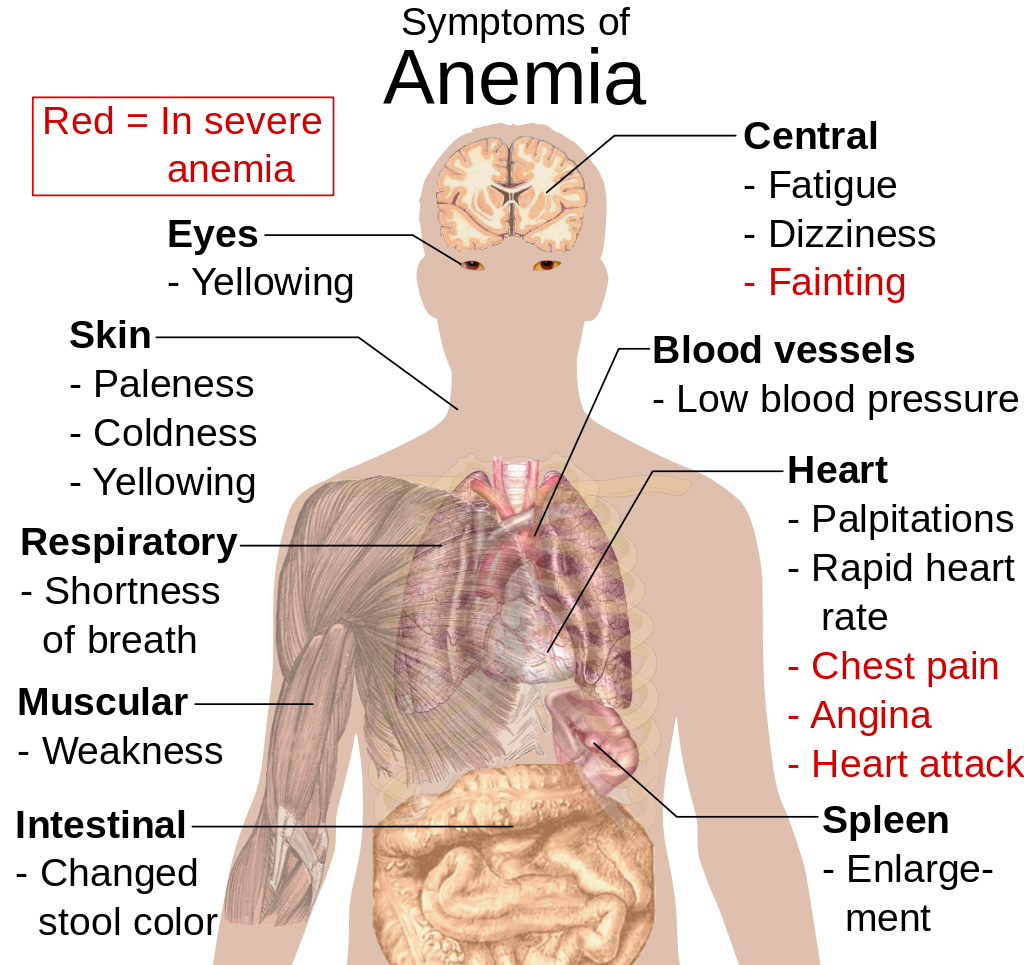

- Anemia is a disorder in which the blood has an inadequate volume of erythrocytes, reducing the amount of oxygen that the blood can carry, and potentially causing weakness and fatigue. These and other signs and symptoms of anemia are shown in Figure 14.5.8. Anemia has many possible causes, including excessive bleeding, inherited disorders (such as sickle cell hemoglobin), or nutritional deficiencies (iron, folate, or B12). Severe anemia may require transfusions of donated blood.

Feature: Myth vs. Reality

Donating blood saves lives. In fact, with each blood donation, as many as three lives may be saved. According to Government Canada, up to 52% of Canadians have reported that they or a family member have needed blood or blood products at some point in their lifetime. Many donors agree that the feeling that comes from knowing you have saved lives is well worth the short amount of time it takes to make a blood donation. Nonetheless, only a minority of potential donors actually donate blood. There are many myths about blood donation that may help explain the small percentage of donors. Knowing the facts may reaffirm your decision to donate if you are already a donor — and if you aren’t a donor already, getting the facts may help you decide to become one.

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| "Your blood might become contaminated with an infection during the donation." | There is no risk of contamination because only single-use, disposable catheters, tubing, and other equipment are used to collect blood for a donation. |

| "You are too old (or too young) to donate blood." | There is no upper age limit on donating blood, as long as you are healthy. The minimum age is 16 years. |

| "You can’t donate blood if you have high blood pressure." | As long as your blood pressure is below 180/100 at the time of donation, you can give blood. Even if you take blood pressure medication to keep your blood pressure below this level, you can donate. |

| "You can’t give blood if you have high cholesterol." | Having high cholesterol does not affect your ability to donate blood. Taking cholesterol-lowering medication also does not disqualify you. |

| "You can’t donate blood if you have had a flu shot." | Having a flu shot has no effect on your ability to donate blood. You can even donate on the same day that you receive a flu shot. |

| "You can’t donate blood if you take medication." | As long as you are healthy, in most cases, taking medication does not preclude you from donating blood. |

| "Your blood isn’t needed if it’s a common blood type." | All types of blood are in constant demand. |

14.5 Summary

- Blood is a fluid connective tissue that circulates throughout the body in the cardiovascular system. Blood supplies tissues with oxygen and nutrients and removes their metabolic wastes. Blood helps defend the body from pathogens and other threats, transports hormones and other substances, and helps keep the body’s pH and temperature in homeostasis.

- Plasma is the liquid component of blood, and it makes up more than half of blood by volume. It consists of water and many dissolved substances. It also contains blood cells, including erythrocytes, leukocytes and thrombocytes.

- Erythrocytes, (also known as red blood cells) are the most numerous cells in blood. They consist mostly of hemoglobin, which carries oxygen. Erythrocytes also carry antigens that determine blood type.

- Leukocytes (also referred to as white blood cells) are less numerous than erythrocytes and are part of the body’s immune system. There are several different types of leukocytes that differ in their specific immune functions. They protect the body from abnormal cells, microorganisms, and other harmful substances.

- Thrombocytes (also called platelets) are cell fragments that play important roles in blood clotting, or coagulation. They stick together at breaks in blood vessels to form a clot and stimulate the production of fibrin, which strengthens the clot.

- All blood cells form by proliferation of stem cells in red bone marrow in a process called hematopoiesis. When blood cells die, they are phagocytized by leukocytes and removed from the circulation.

- Disorders of the blood include leukemia, which is cancer of the bone-forming cells; hemophilia, which is any of several genetic blood-clotting disorders; carbon monoxide poisoning, which prevents erythrocytes from binding with oxygen and causes suffocation; HIV infection, which destroys certain types of leukocytes and can cause AIDS; and anemia, in which there are not enough erythrocytes to carry adequate oxygen to body tissues.

14.5 Review Questions

- What is blood? Why is blood considered a connective tissue?

- Identify four physiological roles of blood in the body.

- Describe plasma and its components.

-

14.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/e-5wqwp64MM

Joe Landolina: This gel can make you stop bleeding instantly, TED, 2014.

https://youtu.be/hgp8LtwFSBA

Can Synthetic Blood Help The World's Blood Shortage? Science Plus, 2016.

https://youtu.be/1Qfmkd6C8u8

How bones make blood - Melody Smith, TED-Ed, 2020.

Attributions

Figure 14.5.1

vampire_PNG32 from pngimg.com is used under a CC BY-NC 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) license.

Figure 14.5.2

Blood-centrifugation-scheme by KnuteKnudsen at English Wikipedia on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.5.3

SEM_blood_cells by Bruce Wetzel and Harry Schaefer (Photographers)/ NCI AV-8202-3656 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Public_domain).

Figure 14.5.4

ABO_blood_type.svg by InvictaHOG on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Public_domain).

Figure 14.5.5

Blood_clot_in_scanning_electron_microscopy by Janice Carr from CDC/ Public Health Image LIbrary (PHIL) ID #7308 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Public_domain).

Figure 14.5.6

Blausen_0740_Platelets by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 14.5.7

Platelet_Party_900x by Awkward Yeti (used with permission of the author) © All Rights Reserved

Figure 14.5.8

Symptoms_of_anemia.svg by Mikael Häggström on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:public_domain).

References

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436.

Blood, organ and tissue donation. (2020, April 28). Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/healthy-living/blood-organ-tissue-donation.html#a3

Canadian Blood Services. (n.d.). There is an immediate need for blood as demand is rising. https://www.blood.ca

Science Plus. (2016, March 2). Can synthetic blood help the world's blood shortage? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hgp8LtwFSBA&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2014, November 20). Joe Landolina: This gel can make you stop bleeding instantly. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-5wqwp64MM&feature=youtu.be

TED-Ed. (2020, January 27). How bones make blood - Melody Smith. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Qfmkd6C8u8&feature=youtu.be

As per caption

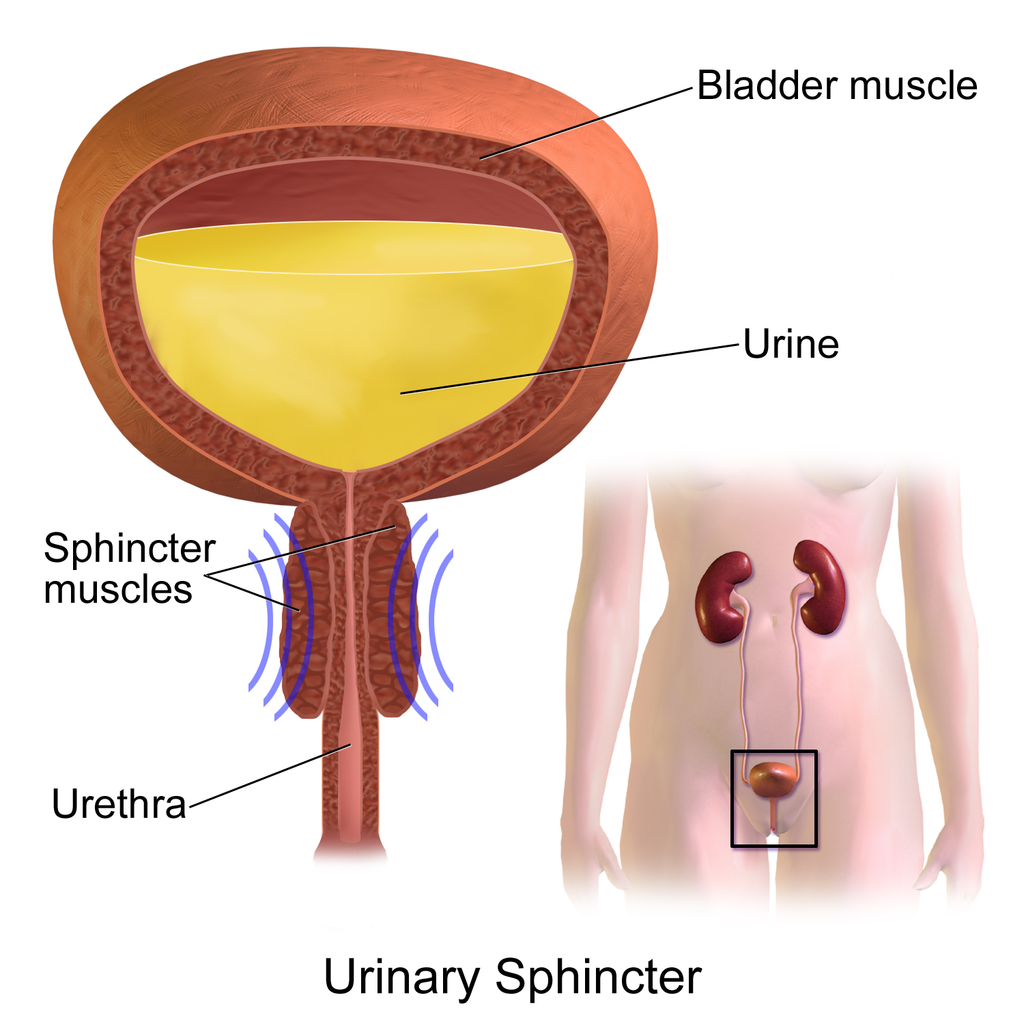

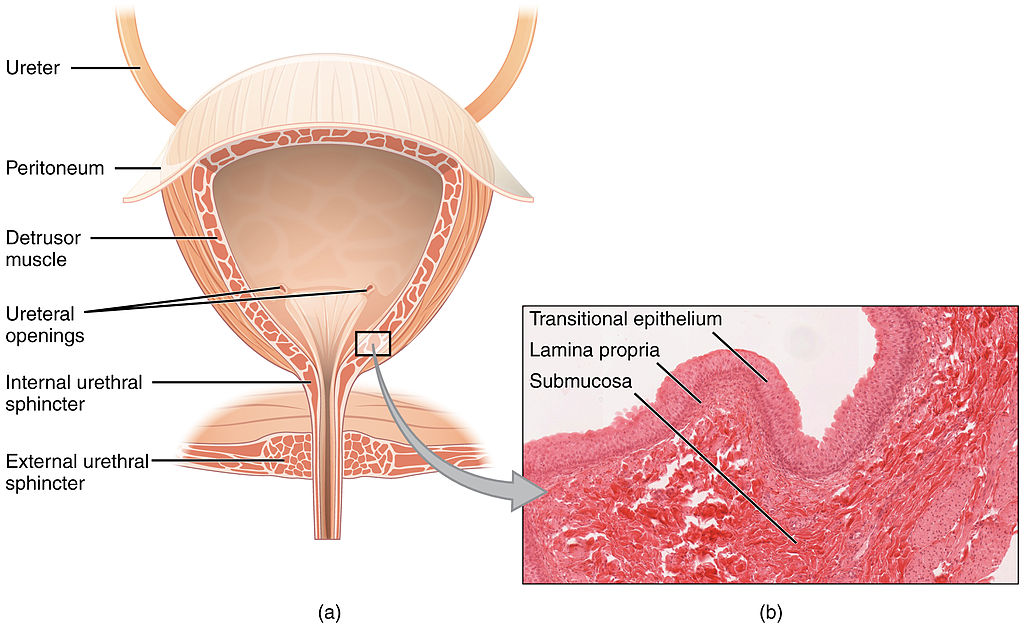

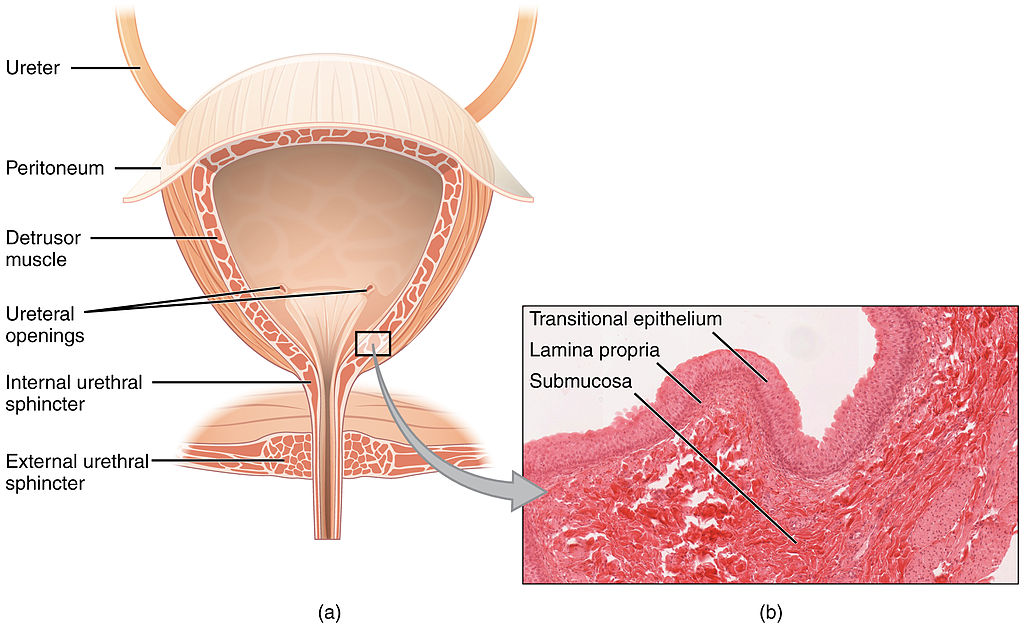

Image shows a diagram of the bladder. There is smooth muscle in the bladder walls which are under involuntary control. There is a sphincter between the bladder and the urethra which can inhibit urination.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Figure 16.3.1 The surprising uses of pee.

Surprising Uses

What do gun powder, leather, fabric dyes and laundry service have in common? This may be surprising, but they all historically involved urine. One of the main components in gun powder, potassium nitrate, was difficult to come by pre-1900s, so ingenious gun-owners would evaporate urine to concentrate the nitrates it contains. The ammonium in urine was excellent in breaking down tissues, making it a prime candidate for softening leathers and removing stains in laundry. Ammonia in urine also helps dyes penetrate fabrics, so it was used to make colours stay brighter for longer.

What is the Urinary System?

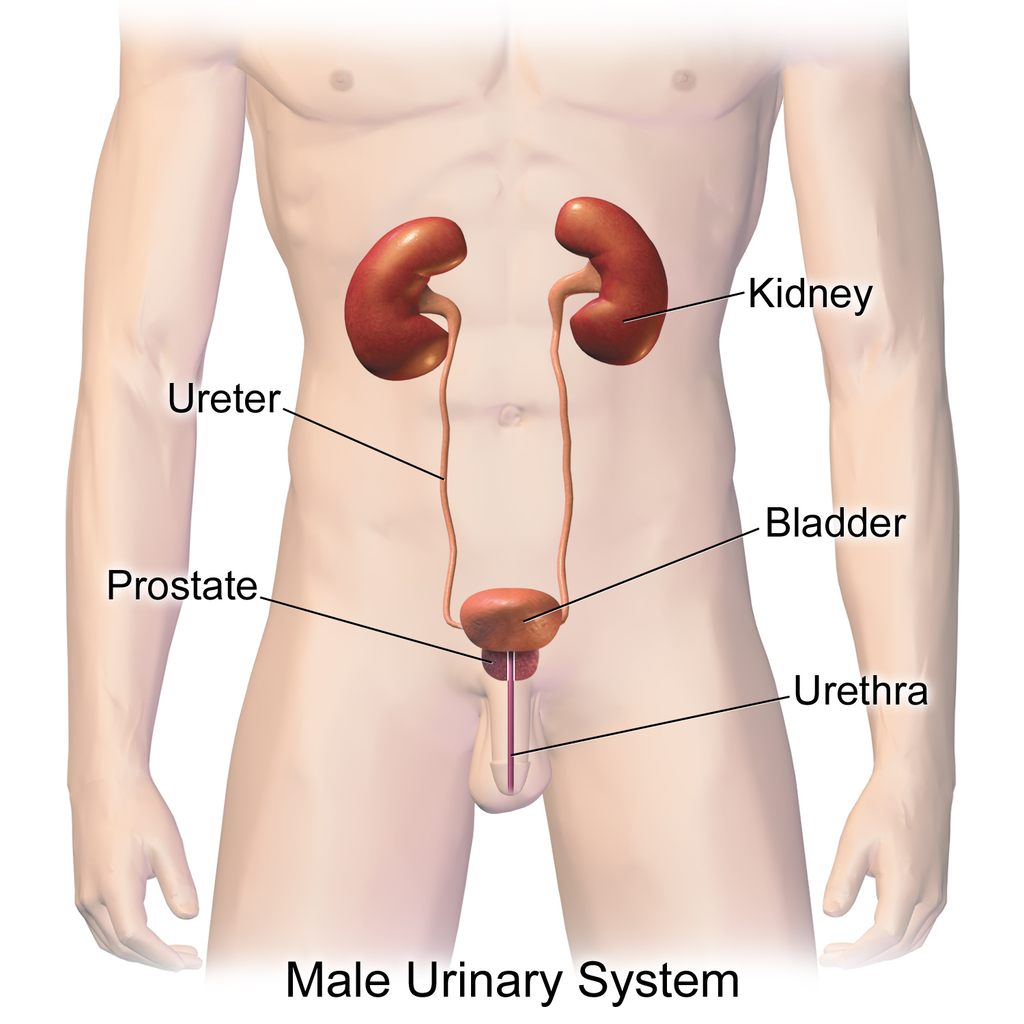

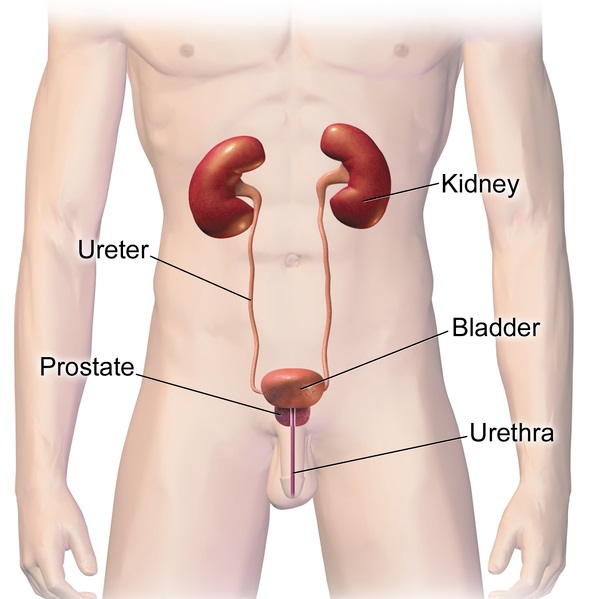

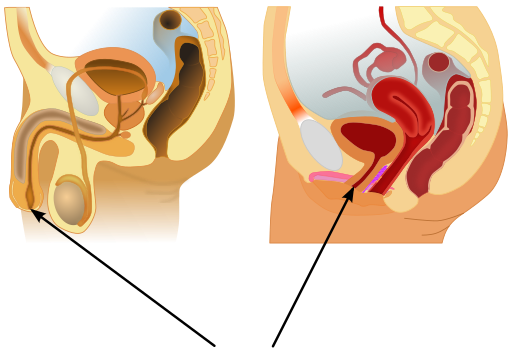

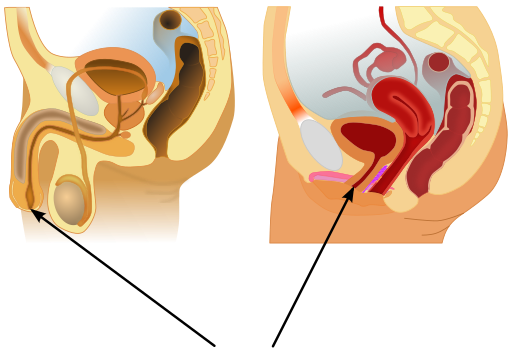

The actual human urinary system, also known as the renal system, is shown in Figure 16.3.2. The system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The main function of the urinary system is to eliminate the waste products of metabolism from the body by forming and excreting urine. Typically, between one and two litres of urine are produced every day in a healthy individual.

Organs of the Urinary System

The urinary system is all about urine. It includes organs that form urine, and also those that transport, store, or excrete urine.

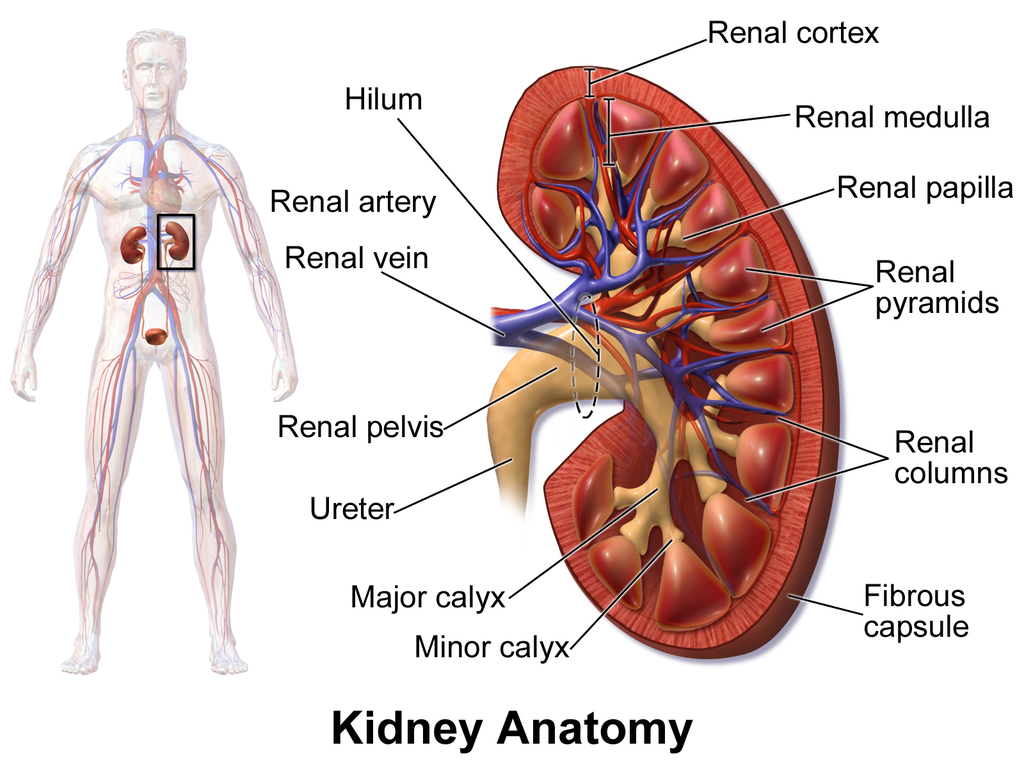

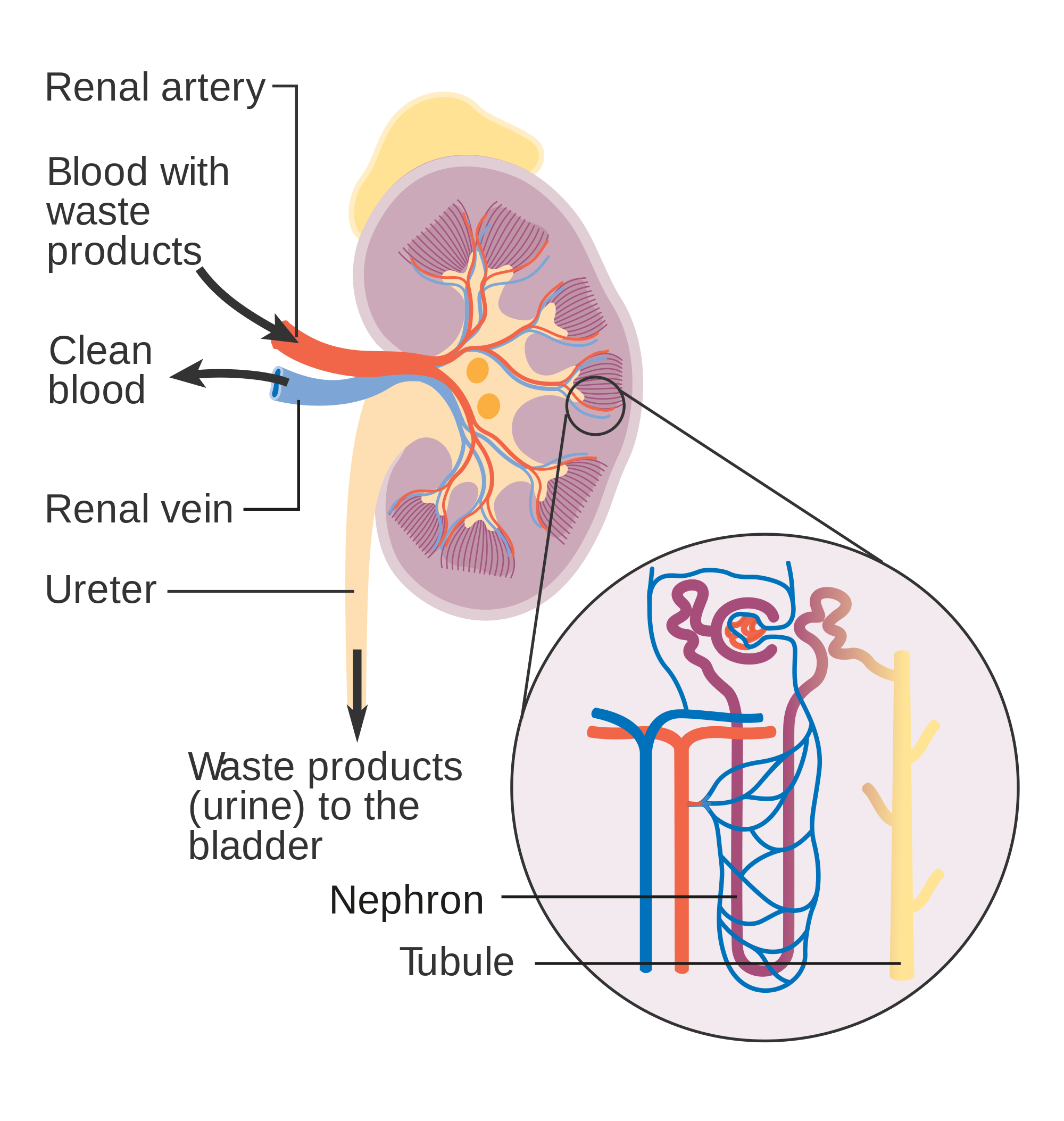

Kidneys

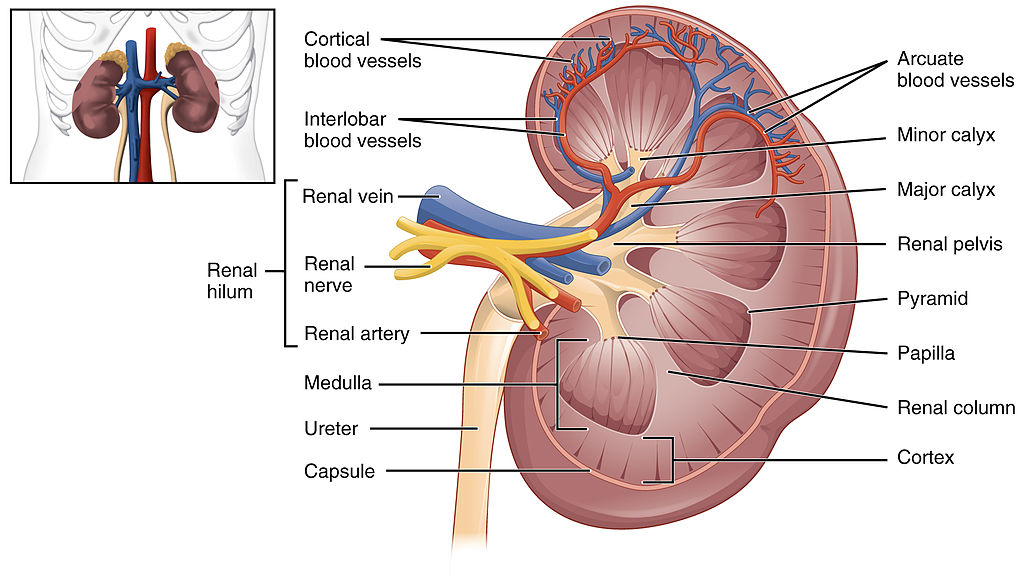

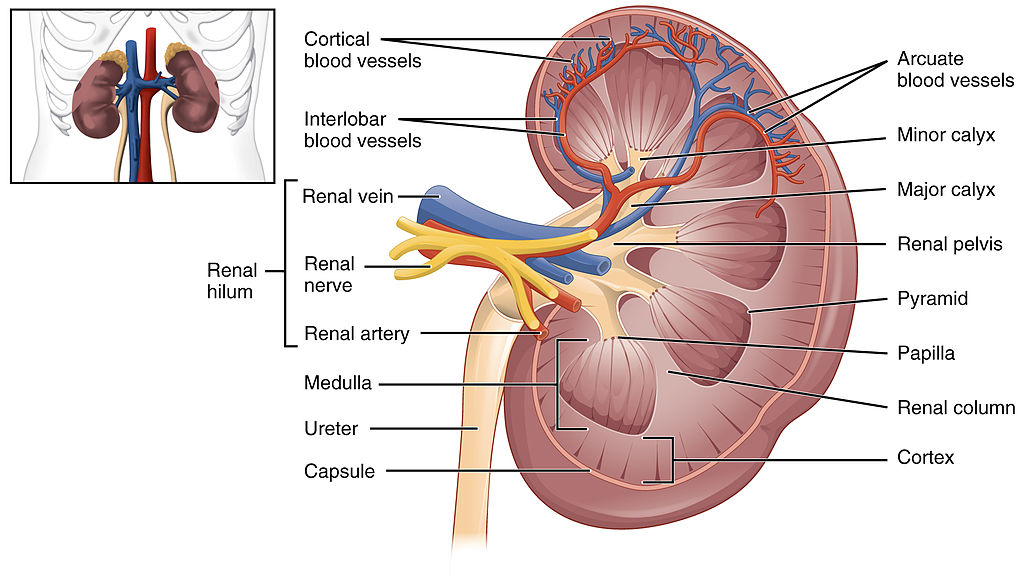

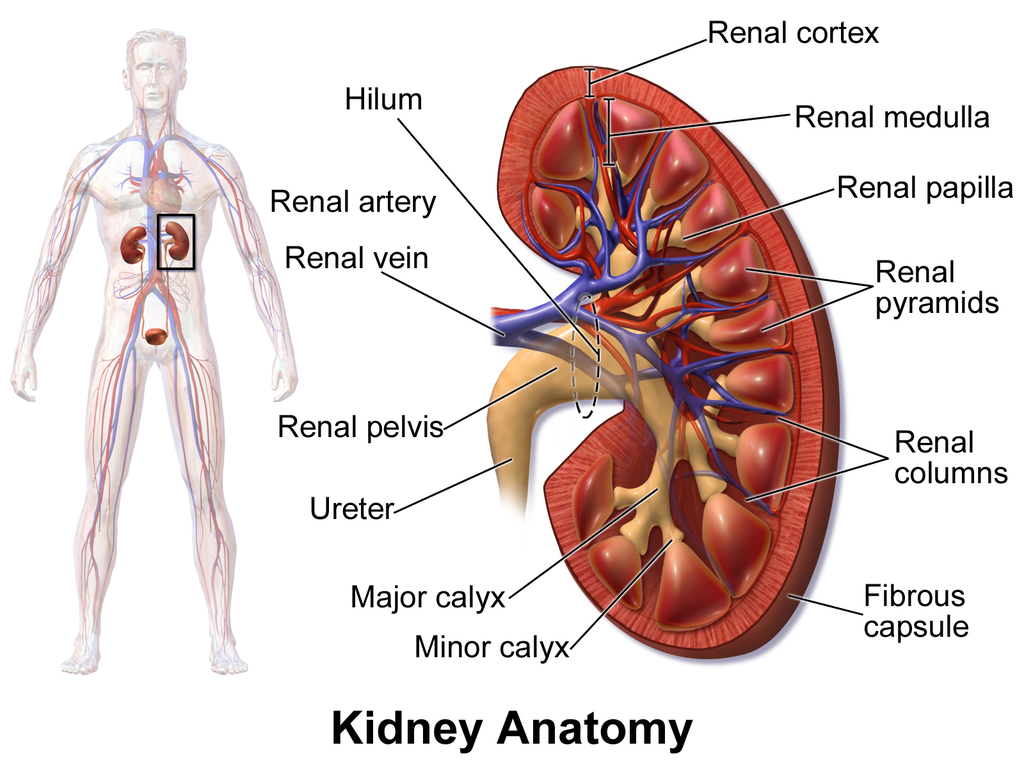

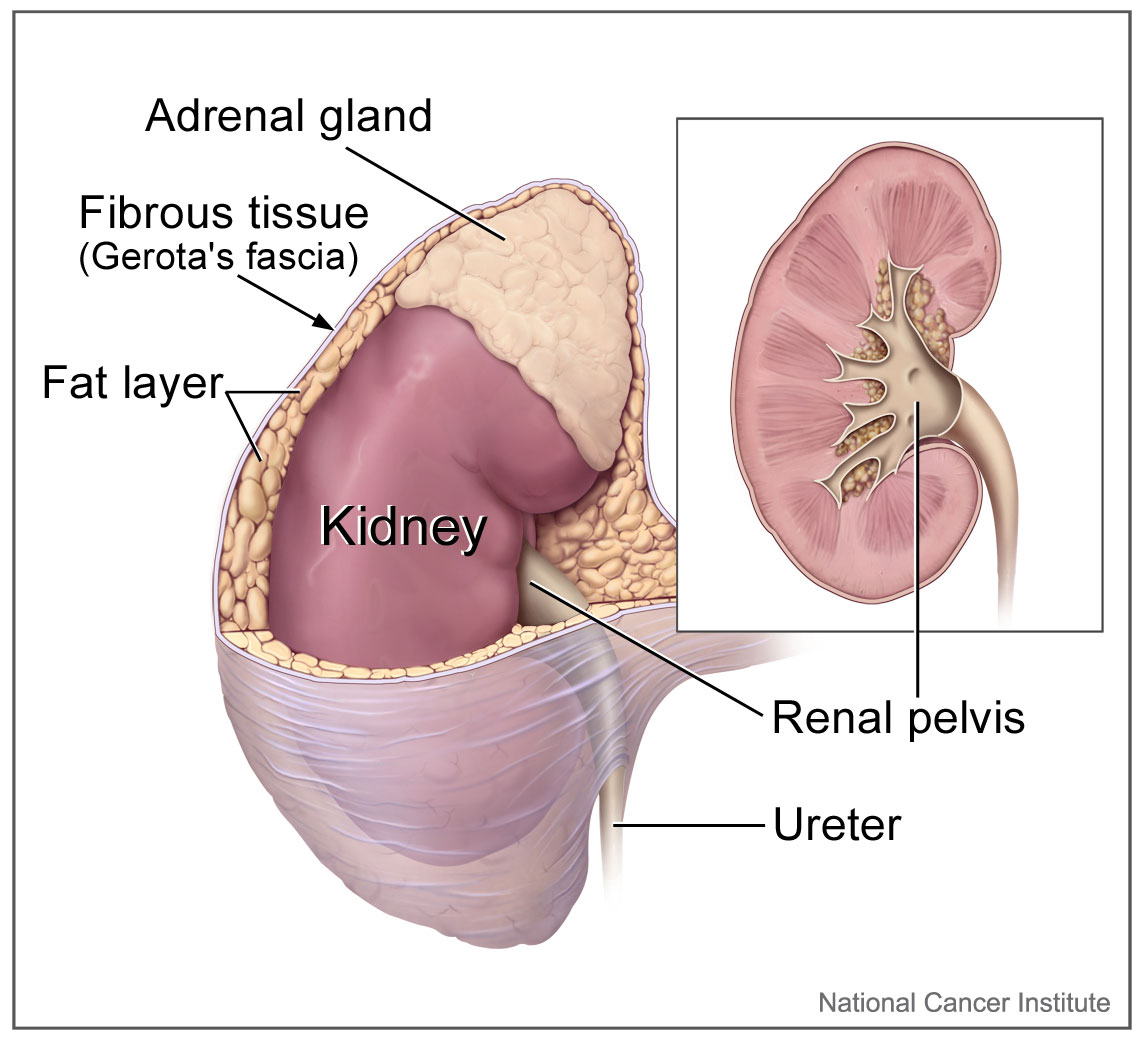

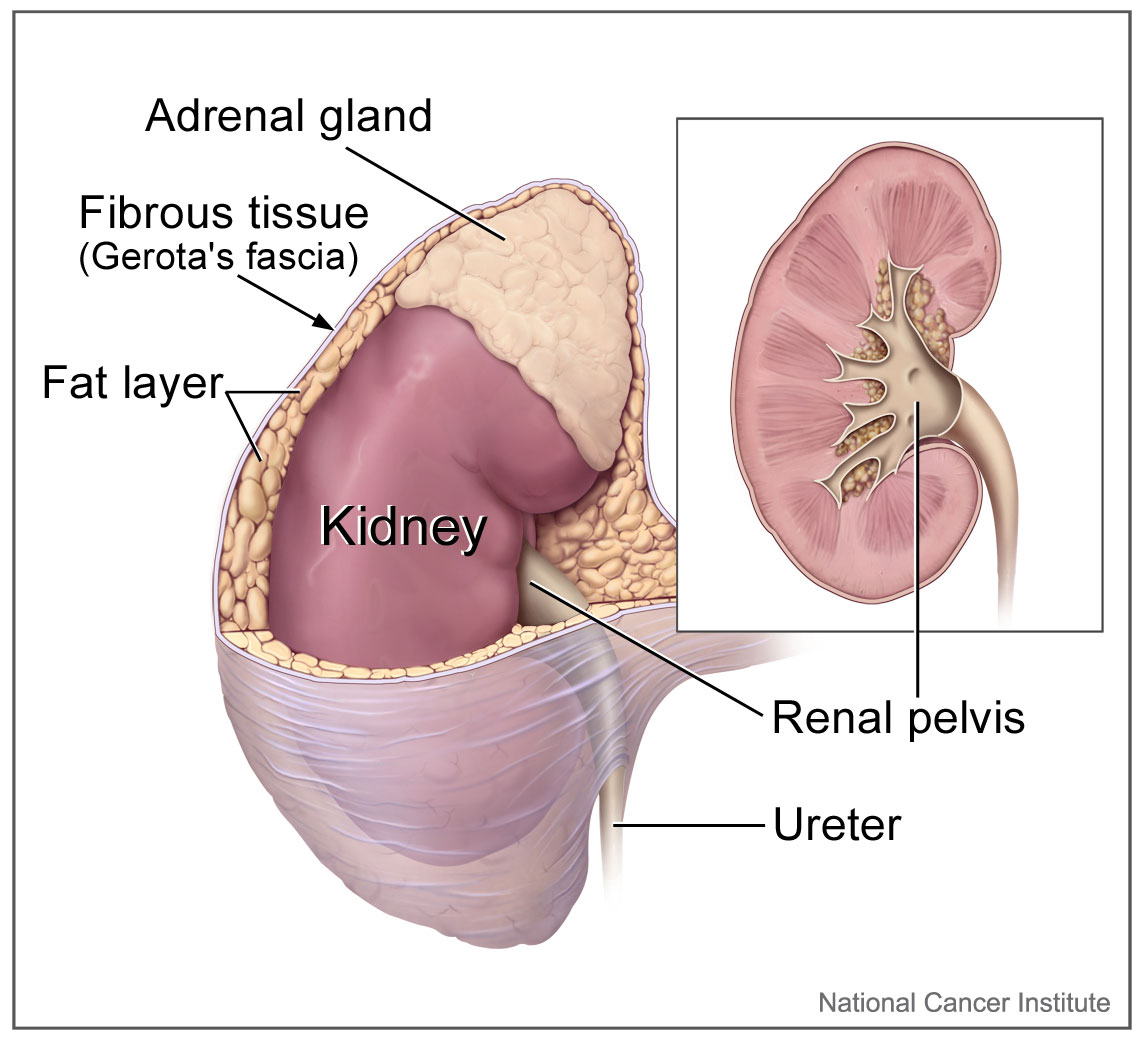

Urine is formed by the kidneys, which filter many substances out of the blood, allow the blood to reabsorb needed materials, and use the remaining materials to form urine. The human body normally has two paired kidneys, although it is possible to get by quite well with just one. As you can see in Figure 16.3.3, each kidney is well supplied with blood vessels by a major artery and vein. Blood to be filtered enters the kidney through the renal artery, and the filtered blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein. The kidney itself is wrapped in a fibrous capsule, and consists of a thin outer layer called the cortex, and a thicker inner layer called the medulla.

Blood is filtered and urine is formed by tiny filtering units called nephrons. Each kidney contains at least a million nephrons, and each nephron spans the cortex and medulla layers of the kidney. After urine forms in the nephrons, it flows through a system of converging collecting ducts. The collecting ducts join together to form minor calyces (or chambers) that join together to form major calyces (see Figure 16.3.3 above). Ultimately, the major calyces join the renal pelvis, which is the funnel-like end of the ureter where it enters the kidney.

Ureters, Bladder, Urethra

After urine forms in the kidneys, it is transported through the ureters (one per kidney) via peristalsis to the sac-like urinary bladder, which stores the urine until urination. During urination, the urine is released from the bladder and transported by the urethra to be excreted outside the body through the external urethral opening.

Functions of the Urinary System

Waste products removed from the body with the formation and elimination of urine include many water-soluble metabolic products. The main waste products are urea — a by-product of protein catabolism — and uric acid, a by-product of nucleic acid catabolism. Excess water and mineral ions are also eliminated in urine.

Besides the elimination of waste products such as these, the urinary system has several other vital functions. These include:

- Maintaining homeostasis of mineral ions in extracellular fluid: These ions are either excreted in urine or returned to the blood as needed to maintain the proper balance.

- Maintaining homeostasis of blood pH: When pH is too low (blood is too acidic), for example, the kidneys excrete less bicarbonate (which is basic) in urine. When pH is too high (blood is too basic), the opposite occurs, and more bicarbonate is excreted in urine.

- Maintaining homeostasis of extracellular fluids, including the blood volume, which helps maintain blood pressure: The kidneys control fluid volume and blood pressure by excreting more or less salt and water in urine.

Control of the Urinary System

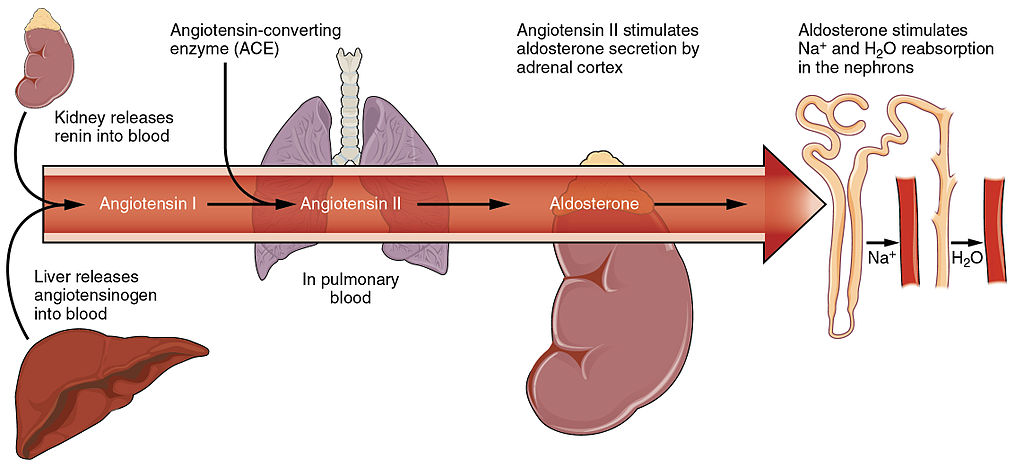

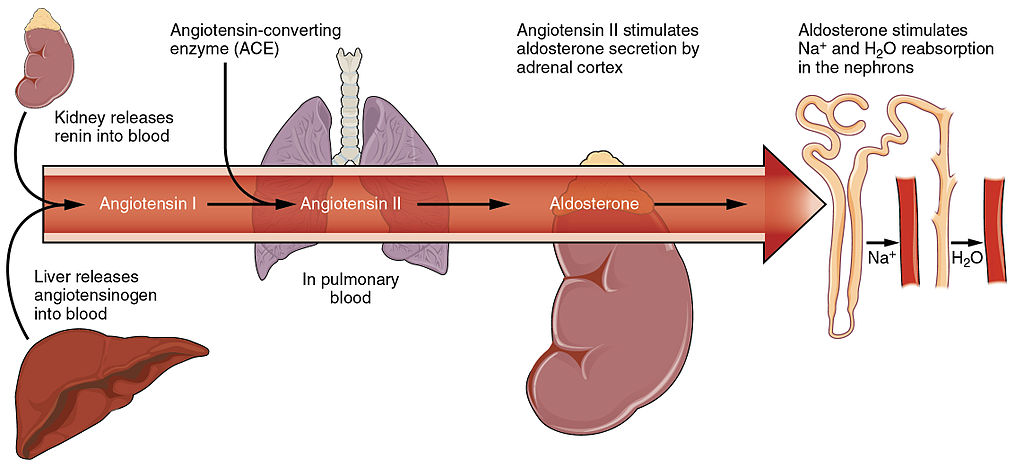

The formation of urine must be closely regulated to maintain body-wide homeostasis. Several endocrine hormones help control this function of the urinary system, including antidiuretic hormone, parathyroid hormone, and aldosterone.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also called vasopressin, is secreted by the posterior pituitary gland. One of its main roles is conserving body water. It is released when the body is dehydrated, and it causes the kidneys to excrete less water in urine.

- Parathyroid hormone is secreted by the parathyroid glands. It works to regulate the balance of mineral ions in the body via its effects on several organs, including the kidneys. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the kidneys to excrete less calcium and more phosphorus in urine.

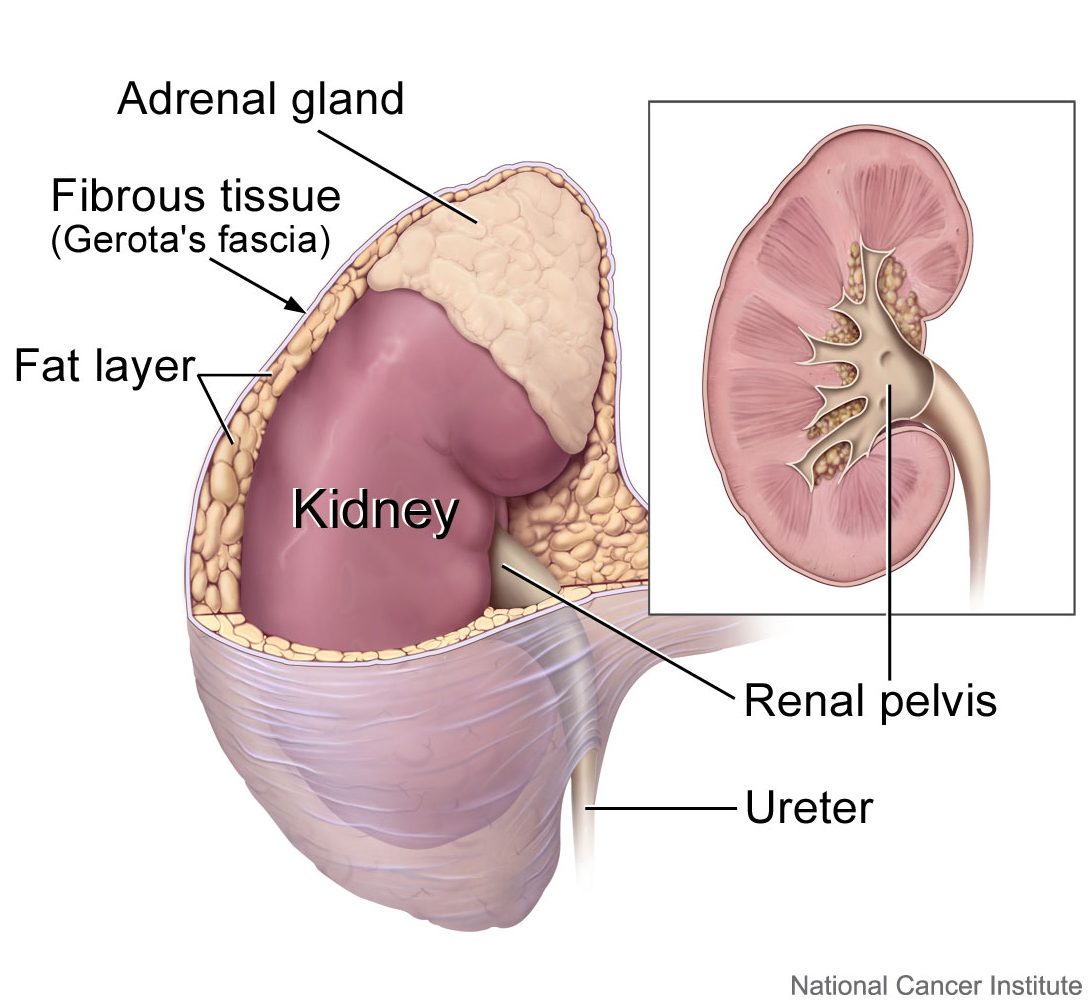

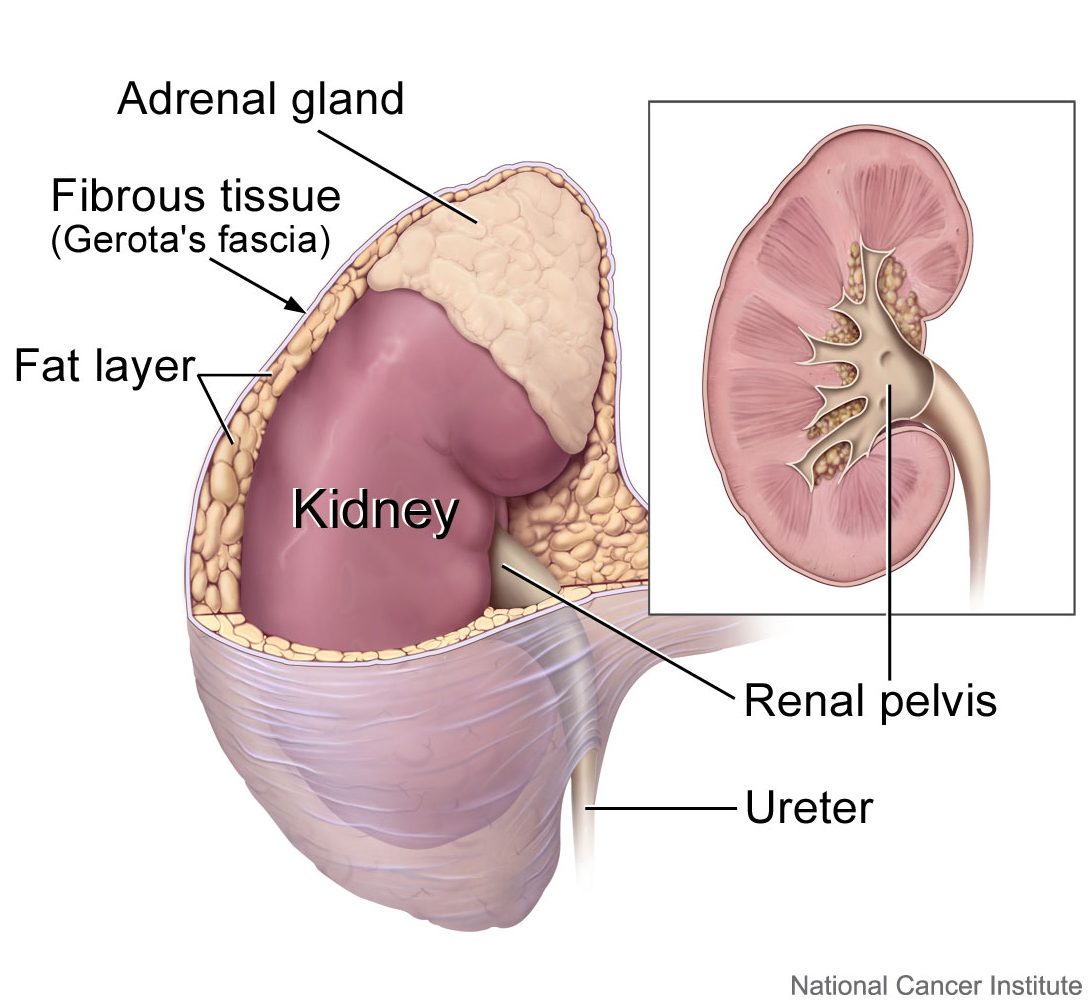

- Aldosterone is secreted by the cortex of the adrenal glands, which rest atop the kidneys, as shown in Figure 16.3.4. Through its effect on the kidneys, it plays a central role in regulating blood pressure. It causes the kidneys to excrete less sodium and water in urine.

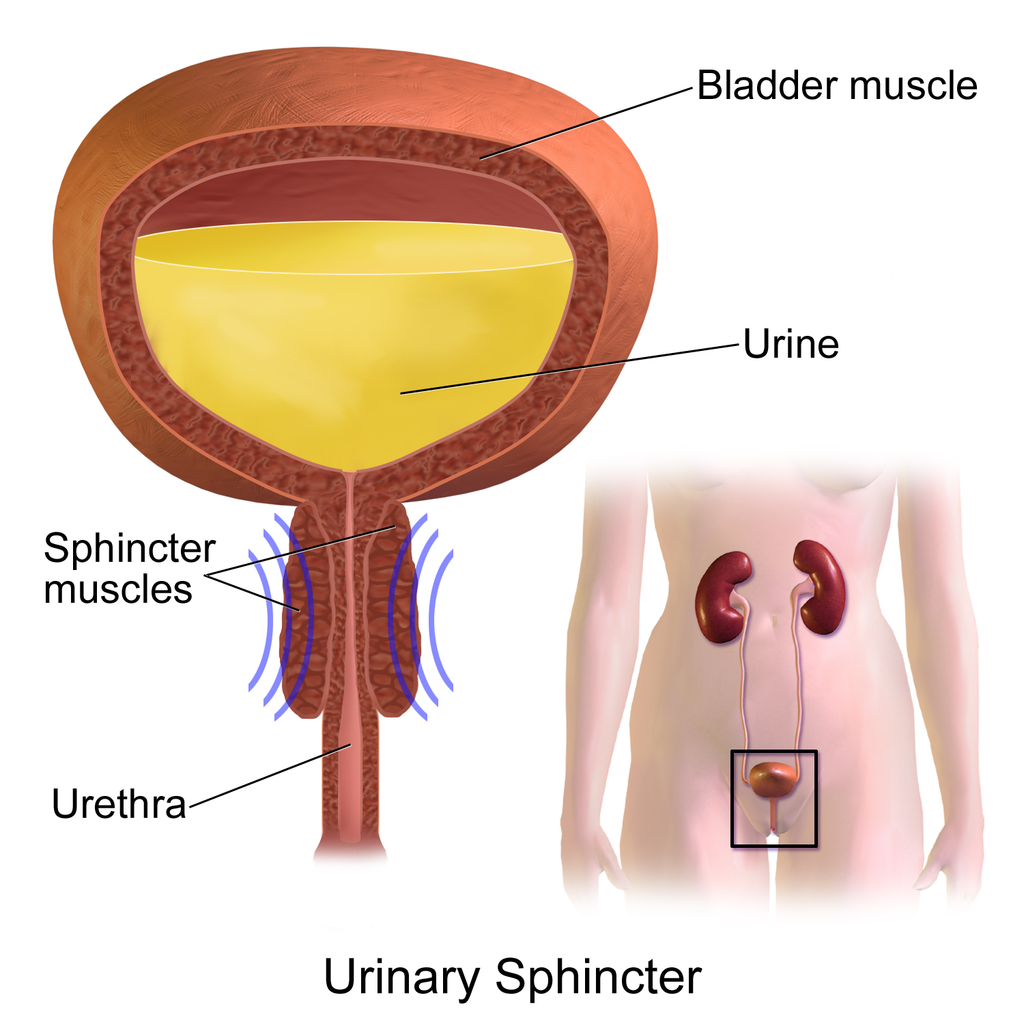

Once urine forms, it is excreted from the body in the process of urination, also sometimes referred to as micturition. This process is controlled by both the autonomic and the somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills with urine, it causes the autonomic nervous system to signal smooth muscle in the bladder wall to contract (as shown in Figure 16.3.5), and the sphincter between the bladder and urethra to relax and open. This forces urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Another sphincter at the distal end of the urethra is under voluntary control. When it relaxes under the influence of the somatic nervous system, it allows urine to leave the body through the external urethral opening.

16.3 Summary

- The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The main function of the urinary system is to eliminate the waste products of metabolism from the body by forming and excreting urine.

- Urine is formed by the kidneys, which filter many substances out of blood, allow the blood to reabsorb needed materials, and use the remaining materials to form urine. Blood to be filtered enters the kidney through the renal artery, and filtered blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein.

- Within each kidney, blood is filtered and urine is formed by tiny filtering units called nephrons, of which there are at least a million in each kidney.

- After urine forms in the kidneys, it is transported through the ureters via peristalsis to the urinary bladder. The bladder stores the urine until urination, when urine is transported by the urethra to be excreted outside the body.

- Besides the elimination of waste products (such as urea, uric acid, excess water, and mineral ions), the urinary system has other vital functions. These include maintaining homeostasis of mineral ions in extracellular fluid, regulating acid-base balance in the blood, regulating the volume of extracellular fluids, and controlling blood pressure.

- The formation of urine must be closely regulated to maintain body-wide homeostasis. Several endocrine hormones help control this function of the urinary system, including antidiuretic hormone from the posterior pituitary gland, parathyroid hormone from the parathyroid glands, and aldosterone from the adrenal glands.

- The process of urination is controlled by both the autonomic and the somatic nervous systems. The autonomic system causes the bladder to empty, but conscious relaxation of the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra allows urine to leave the body.

16.3 Review Questions

-

- State the main function of the urinary system.

- What are nephrons?

- Other than the elimination of waste products, identify functions of the urinary system.

- How is the formation of urine regulated?

- Explain why it is important to have voluntary control over the sphincter at the end of the urethra.

- In terms of how they affect the kidneys, compare aldosterone to antidiuretic hormone.

- If your body needed to retain more calcium, which of the hormones described in this concept is most likely to increase? Explain your reasoning.

16.3 Explore More

https://youtu.be/dxecGD0m0Xc

The Urinary System - An Introduction | Physiology | Biology | FuseSchool, 2017.

https://youtu.be/pyMcTUQYMQw

Maple Syrup Urine Disease, Alexandria Doody, 2016.

https://youtu.be/3z-xjfdJWAI

How Accurate Are Drug Tests? Seeker, 2016.

https://youtu.be/xt1Tj5eeS0k

Three Ways Pee Could Change the World, Gross Science, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 16.3.1

- File:Pyrodex powder ffg.jpg by Hustvedt on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en).

- Brown leather satchel bag by Álvaro Serrano on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Laundry basket by Andy Fitzsimon on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Tags: Wool Skeins Natural Dyed Colorful Himalayan Weavers by on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.3.2

Urinary_System_(Male) by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.3.3

2610_The_Kidney by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 16.3.4

Adrenal glands on Kidney by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator)/ NCI Visuals Online is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.3.5

Urinary_Sphincter by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Alexandria Doody. (2016, March 29). Maple syrup urine disease. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pyMcTUQYMQw&feature=youtu.be

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.8 Left kidney [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 25.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-3-gross-anatomy-of-the-kidney

FuseSchool. (2017, June 19). The urinary system - An introduction | Physiology | Biology | FuseSchool. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxecGD0m0Xc&feature=youtu.be

Gross Science. (2015, September 15). Three ways pee could change the world. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xt1Tj5eeS0k&feature=youtu.be

Seeker. (2016, January 16). How accurate are drug tests? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3z-xjfdJWAI&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Figure 16.3.1 The surprising uses of pee.

Surprising Uses

What do gun powder, leather, fabric dyes and laundry service have in common? This may be surprising, but they all historically involved urine. One of the main components in gun powder, potassium nitrate, was difficult to come by pre-1900s, so ingenious gun-owners would evaporate urine to concentrate the nitrates it contains. The ammonium in urine was excellent in breaking down tissues, making it a prime candidate for softening leathers and removing stains in laundry. Ammonia in urine also helps dyes penetrate fabrics, so it was used to make colours stay brighter for longer.

What is the Urinary System?

The actual human urinary system, also known as the renal system, is shown in Figure 16.3.2. The system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The main function of the urinary system is to eliminate the waste products of metabolism from the body by forming and excreting urine. Typically, between one and two litres of urine are produced every day in a healthy individual.

Organs of the Urinary System

The urinary system is all about urine. It includes organs that form urine, and also those that transport, store, or excrete urine.

Kidneys

Urine is formed by the kidneys, which filter many substances out of the blood, allow the blood to reabsorb needed materials, and use the remaining materials to form urine. The human body normally has two paired kidneys, although it is possible to get by quite well with just one. As you can see in Figure 16.3.3, each kidney is well supplied with blood vessels by a major artery and vein. Blood to be filtered enters the kidney through the renal artery, and the filtered blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein. The kidney itself is wrapped in a fibrous capsule, and consists of a thin outer layer called the cortex, and a thicker inner layer called the medulla.

Blood is filtered and urine is formed by tiny filtering units called nephrons. Each kidney contains at least a million nephrons, and each nephron spans the cortex and medulla layers of the kidney. After urine forms in the nephrons, it flows through a system of converging collecting ducts. The collecting ducts join together to form minor calyces (or chambers) that join together to form major calyces (see Figure 16.3.3 above). Ultimately, the major calyces join the renal pelvis, which is the funnel-like end of the ureter where it enters the kidney.

Ureters, Bladder, Urethra

After urine forms in the kidneys, it is transported through the ureters (one per kidney) via peristalsis to the sac-like urinary bladder, which stores the urine until urination. During urination, the urine is released from the bladder and transported by the urethra to be excreted outside the body through the external urethral opening.

Functions of the Urinary System

Waste products removed from the body with the formation and elimination of urine include many water-soluble metabolic products. The main waste products are urea — a by-product of protein catabolism — and uric acid, a by-product of nucleic acid catabolism. Excess water and mineral ions are also eliminated in urine.

Besides the elimination of waste products such as these, the urinary system has several other vital functions. These include:

- Maintaining homeostasis of mineral ions in extracellular fluid: These ions are either excreted in urine or returned to the blood as needed to maintain the proper balance.

- Maintaining homeostasis of blood pH: When pH is too low (blood is too acidic), for example, the kidneys excrete less bicarbonate (which is basic) in urine. When pH is too high (blood is too basic), the opposite occurs, and more bicarbonate is excreted in urine.

- Maintaining homeostasis of extracellular fluids, including the blood volume, which helps maintain blood pressure: The kidneys control fluid volume and blood pressure by excreting more or less salt and water in urine.

Control of the Urinary System

The formation of urine must be closely regulated to maintain body-wide homeostasis. Several endocrine hormones help control this function of the urinary system, including antidiuretic hormone, parathyroid hormone, and aldosterone.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also called vasopressin, is secreted by the posterior pituitary gland. One of its main roles is conserving body water. It is released when the body is dehydrated, and it causes the kidneys to excrete less water in urine.

- Parathyroid hormone is secreted by the parathyroid glands. It works to regulate the balance of mineral ions in the body via its effects on several organs, including the kidneys. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the kidneys to excrete less calcium and more phosphorus in urine.

- Aldosterone is secreted by the cortex of the adrenal glands, which rest atop the kidneys, as shown in Figure 16.3.4. Through its effect on the kidneys, it plays a central role in regulating blood pressure. It causes the kidneys to excrete less sodium and water in urine.

Once urine forms, it is excreted from the body in the process of urination, also sometimes referred to as micturition. This process is controlled by both the autonomic and the somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills with urine, it causes the autonomic nervous system to signal smooth muscle in the bladder wall to contract (as shown in Figure 16.3.5), and the sphincter between the bladder and urethra to relax and open. This forces urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Another sphincter at the distal end of the urethra is under voluntary control. When it relaxes under the influence of the somatic nervous system, it allows urine to leave the body through the external urethral opening.

16.3 Summary

- The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The main function of the urinary system is to eliminate the waste products of metabolism from the body by forming and excreting urine.

- Urine is formed by the kidneys, which filter many substances out of blood, allow the blood to reabsorb needed materials, and use the remaining materials to form urine. Blood to be filtered enters the kidney through the renal artery, and filtered blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein.

- Within each kidney, blood is filtered and urine is formed by tiny filtering units called nephrons, of which there are at least a million in each kidney.

- After urine forms in the kidneys, it is transported through the ureters via peristalsis to the urinary bladder. The bladder stores the urine until urination, when urine is transported by the urethra to be excreted outside the body.

- Besides the elimination of waste products (such as urea, uric acid, excess water, and mineral ions), the urinary system has other vital functions. These include maintaining homeostasis of mineral ions in extracellular fluid, regulating acid-base balance in the blood, regulating the volume of extracellular fluids, and controlling blood pressure.

- The formation of urine must be closely regulated to maintain body-wide homeostasis. Several endocrine hormones help control this function of the urinary system, including antidiuretic hormone from the posterior pituitary gland, parathyroid hormone from the parathyroid glands, and aldosterone from the adrenal glands.

- The process of urination is controlled by both the autonomic and the somatic nervous systems. The autonomic system causes the bladder to empty, but conscious relaxation of the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra allows urine to leave the body.

16.3 Review Questions

-

- State the main function of the urinary system.

- What are nephrons?

- Other than the elimination of waste products, identify functions of the urinary system.

- How is the formation of urine regulated?

- Explain why it is important to have voluntary control over the sphincter at the end of the urethra.

- In terms of how they affect the kidneys, compare aldosterone to antidiuretic hormone.

- If your body needed to retain more calcium, which of the hormones described in this concept is most likely to increase? Explain your reasoning.

16.3 Explore More

https://youtu.be/dxecGD0m0Xc

The Urinary System - An Introduction | Physiology | Biology | FuseSchool, 2017.

https://youtu.be/pyMcTUQYMQw

Maple Syrup Urine Disease, Alexandria Doody, 2016.

https://youtu.be/3z-xjfdJWAI

How Accurate Are Drug Tests? Seeker, 2016.

https://youtu.be/xt1Tj5eeS0k

Three Ways Pee Could Change the World, Gross Science, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 16.3.1

- File:Pyrodex powder ffg.jpg by Hustvedt on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en).

- Brown leather satchel bag by Álvaro Serrano on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Laundry basket by Andy Fitzsimon on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Tags: Wool Skeins Natural Dyed Colorful Himalayan Weavers by on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.3.2

Urinary_System_(Male) by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.3.3

2610_The_Kidney by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 16.3.4

Adrenal glands on Kidney by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator)/ NCI Visuals Online is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.3.5

Urinary_Sphincter by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Alexandria Doody. (2016, March 29). Maple syrup urine disease. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pyMcTUQYMQw&feature=youtu.be

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.8 Left kidney [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 25.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-3-gross-anatomy-of-the-kidney

FuseSchool. (2017, June 19). The urinary system - An introduction | Physiology | Biology | FuseSchool. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxecGD0m0Xc&feature=youtu.be

Gross Science. (2015, September 15). Three ways pee could change the world. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xt1Tj5eeS0k&feature=youtu.be

Seeker. (2016, January 16). How accurate are drug tests? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3z-xjfdJWAI&feature=youtu.be

Image shows a freshly baked Steak and Kidney Pie.

Image shows a labelled diagram of the posterior (from the back) view of the kidneys. The aorta and renal arteries are clearly visible bringing blood to each kidney. The left kidney sits a bit higher than the right kidney.

The transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber.

Image shows a diagram of a renal tubule and which substances are secreted or absorbed at each location along the tubule. Most secretion happens at the proximal convoluted tubule, although it does take place at all locations on the renal tubule. Reabsorption occurs mainly in the loop of Henle when balancing water and in the distal convoluted tubule when balancing pH.

As per caption

A transparent watery fluid similar to plasma, but containing low protein concentrations. It is secreted from the ciliary epithelium, a structure supporting the lens.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Kidneys on the Menu

Pictured in Figure 16.4.1 is a steak and kidney pie; this savory dish is a British favorite. When kidneys are on a menu, they typically come from sheep, pigs, or cows. In these animals (as in the human animal), kidneys are the main organs of excretion.

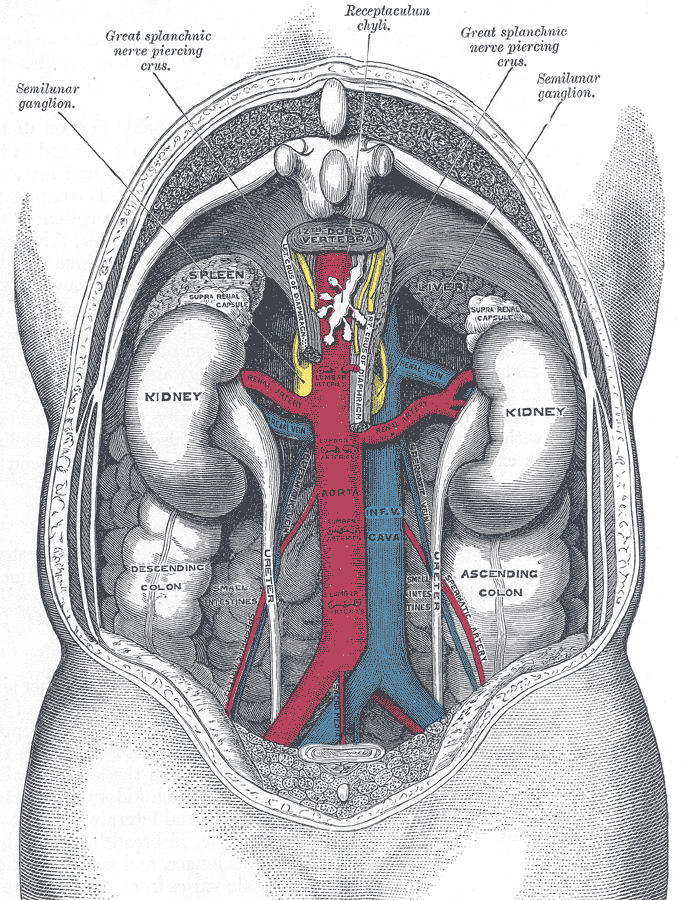

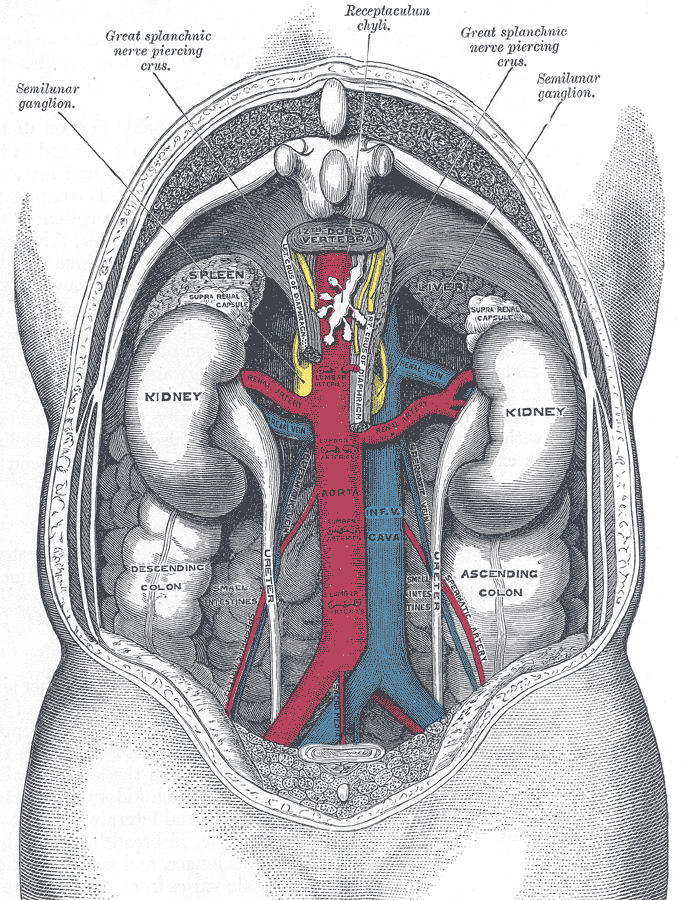

Location of the Kidneys

The two bean-shaped kidneys are located high in the back of the abdominal cavity, one on each side of the spine. Both kidneys sit just below the diaphragm, the large breathing muscle that separates the abdominal and thoracic cavities. As you can see in the following figure, the right kidney is slightly smaller and lower than the left kidney. The right kidney is behind the liver, and the left kidney is behind the spleen. The location of the liver explains why the right kidney is smaller and lower than the left.

Kidney Anatomy

The shape of each kidney gives it a convex side (curving outward) and a concave side (curving inward). You can see this clearly in the detailed diagram of kidney anatomy shown in Figure 16.4.3. The concave side is where the renal artery enters the kidney, as well as where the renal vein and ureter leave the kidney. This area of the kidney is called the hilum. The entire kidney is surrounded by tough fibrous tissue — called the renal capsule — which, in turn, is surrounded by two layers of protective, cushioning fat.

Internally, each kidney is divided into two major layers: the outer renal cortex and the inner renal medulla (see Figure 16.4.3 above). These layers take the shape of many cone-shaped renal lobules, each containing renal cortex surrounding a portion of medulla called a renal pyramid. Within the renal pyramids are the structural and functional units of the kidneys, the tiny nephrons. Between the renal pyramids are projections of cortex called renal columns. The tip, or papilla, of each pyramid empties urine into a minor calyx (chamber). Several minor calyces empty into a major calyx, and the latter empty into the funnel-shaped cavity called the renal pelvis, which becomes the ureter as it leaves the kidney.

Renal Circulation

The renal circulation is an important part of the kidney’s primary function of filtering waste products from the blood. Blood is supplied to the kidneys via the renal arteries. The right renal artery supplies the right kidney, and the left renal artery supplies the left kidney. These two arteries branch directly from the aorta, which is the largest artery in the body. Each kidney is only about 11 cm (4.4 in) long, and has a mass of just 150 grams (5.3 oz), yet it receives about ten per cent of the total output of blood from the heart. Blood is filtered through the kidneys every 3 minutes, 24 hours a day, every day of your life.

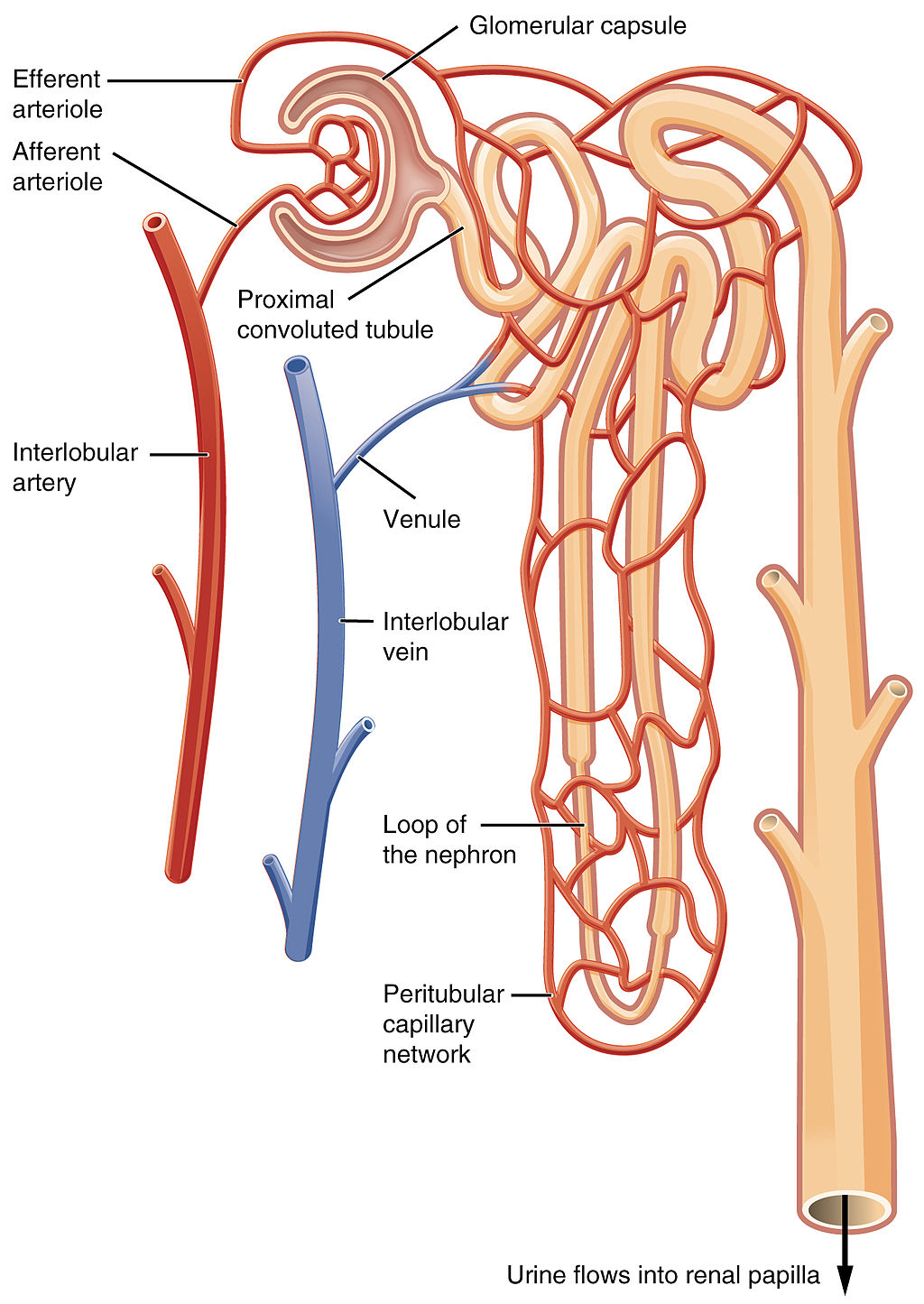

As indicated in Figure 16.4.4, each renal artery carries blood with waste products into the kidney. Within the kidney, the renal artery branches into increasingly smaller arteries that extend through the renal columns between the renal pyramids. These arteries, in turn, branch into arterioles that penetrate the renal pyramids. Blood in the arterioles passes through nephrons, the structures that actually filter the blood. After blood passes through the nephrons and is filtered, the clean blood moves through a network of venules that converge into small veins. Small veins merge into increasingly larger ones, and ultimately into the renal vein, which carries clean blood away from the kidney to the inferior vena cava.

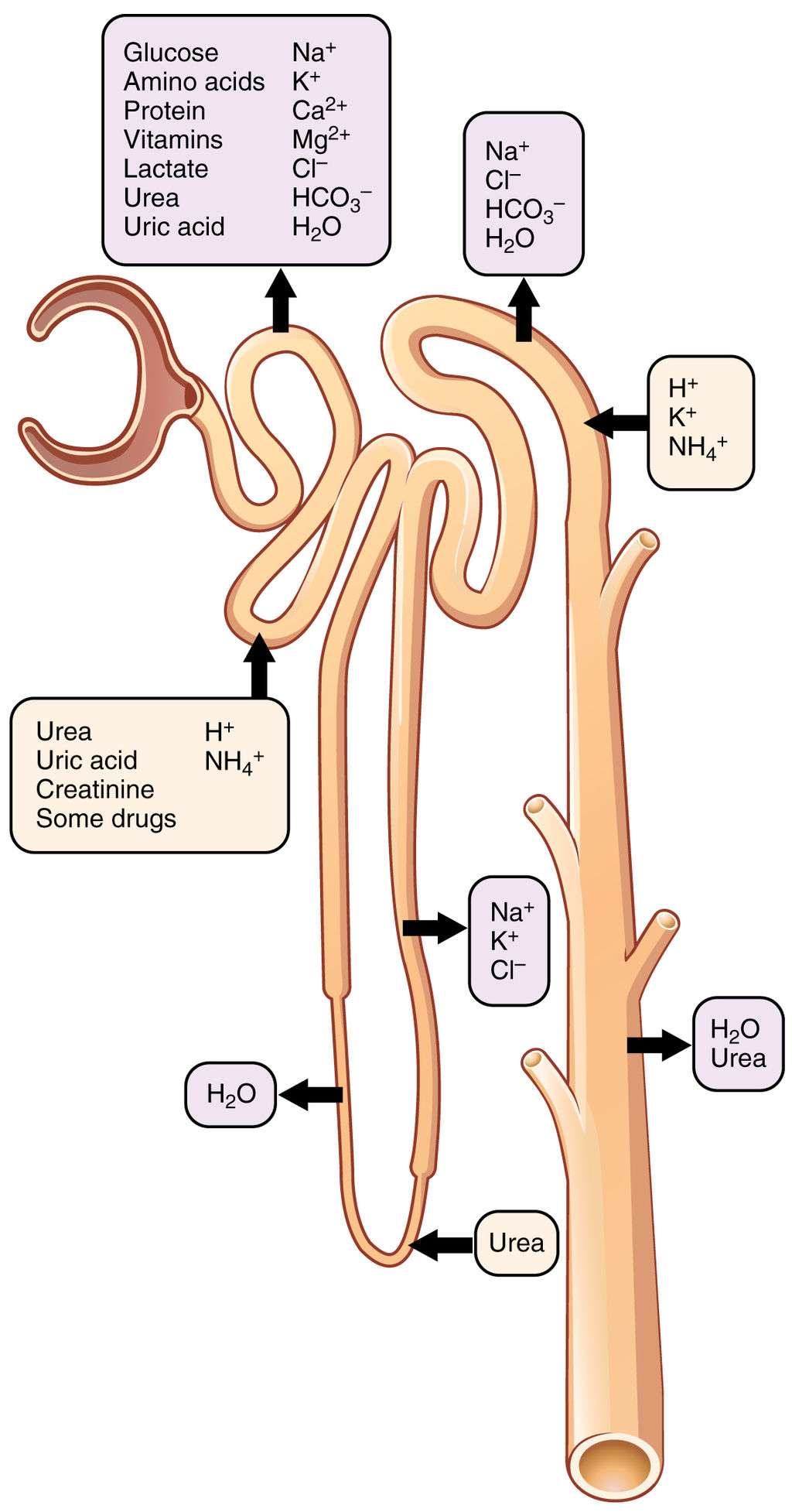

Nephron Structure and Function

Figure 16.4.4 gives an indication of the complex structure of a nephron. The nephron is the basic structural and functional unit of the kidney, and each kidney typically contains at least a million of them. As blood flows through a nephron, many materials are filtered out of the blood, needed materials are returned to the blood, and the remaining materials form urine. Most of the waste products removed from the blood and excreted in urine are byproducts of metabolism. At least half of the waste is urea, a waste product produced by protein catabolism. Another important waste is uric acid, produced in nucleic acid catabolism.

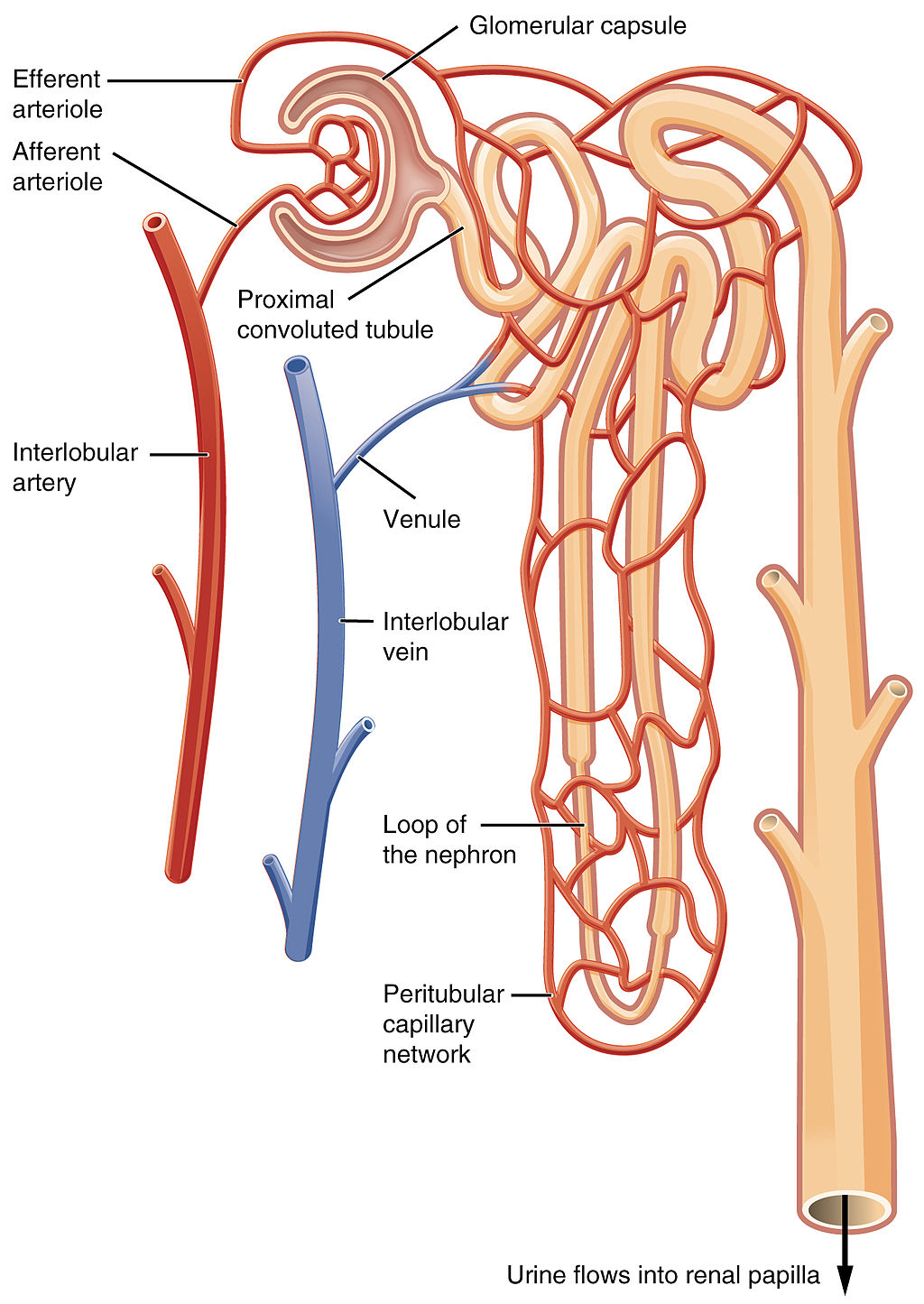

Components of a Nephron

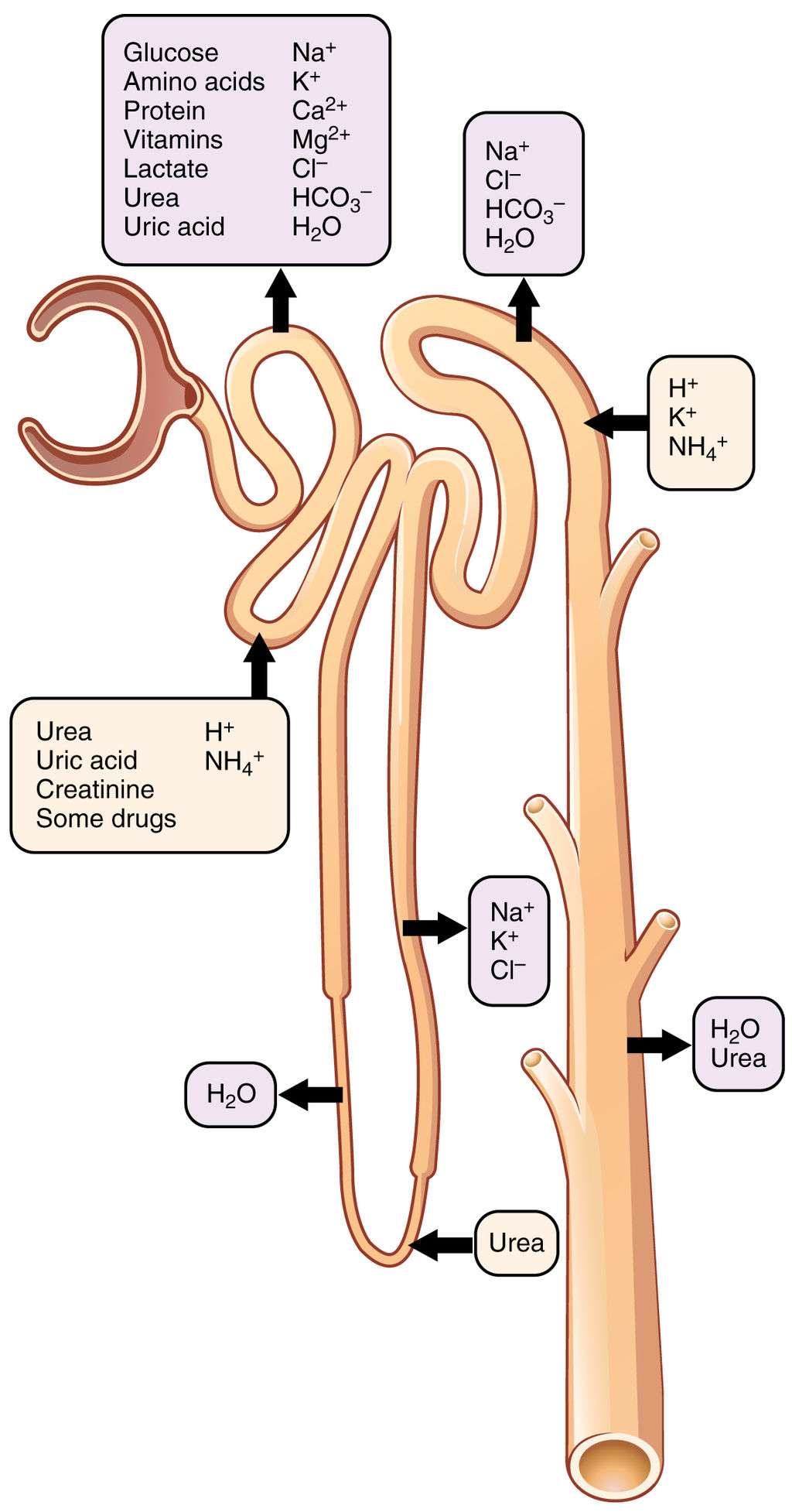

Figure 16.4.5 shows in greater detail the components of a nephron. Each nephron is composed of an initial filtering component that consists of a network of capillaries called the glomerulus (plural, glomeruli), which is surrounded by a space within a structure called glomerular capsule (also known as the Bowman's capsule). Extending from glomerular capsule is the renal tubule. The proximal end (nearest glomerular capsule) of the renal tubule is called the proximal convoluted (coiled) tubule. From here, the renal tubule continues as a loop (known as the loop of Henle) (also known as the loop of the nephron), which in turn becomes the distal convoluted tubule. The latter finally joins with a collecting duct. As you can see in the diagram, arterioles surround the total length of the renal tubule in a mesh called the peritubular capillary network.

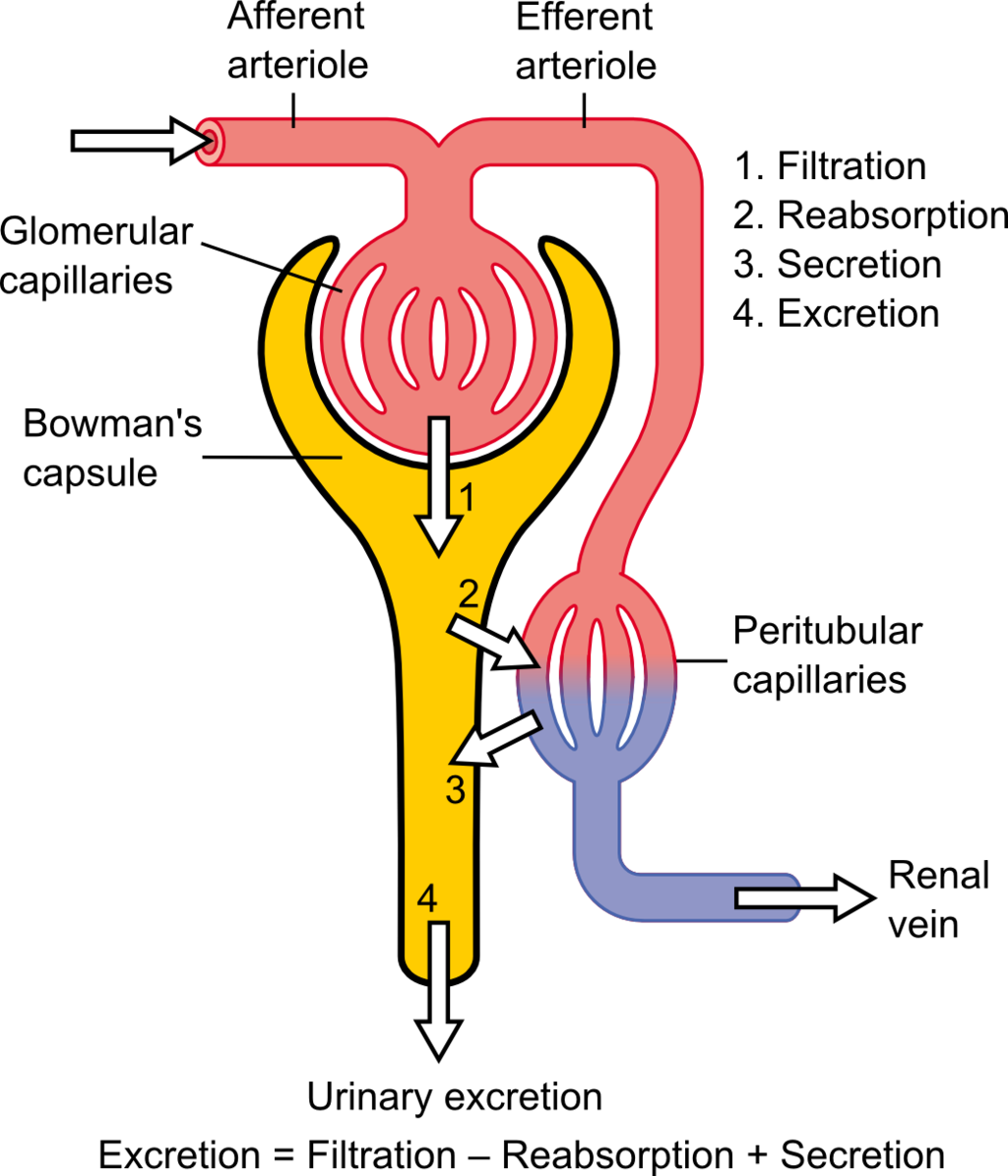

Function of a Nephron

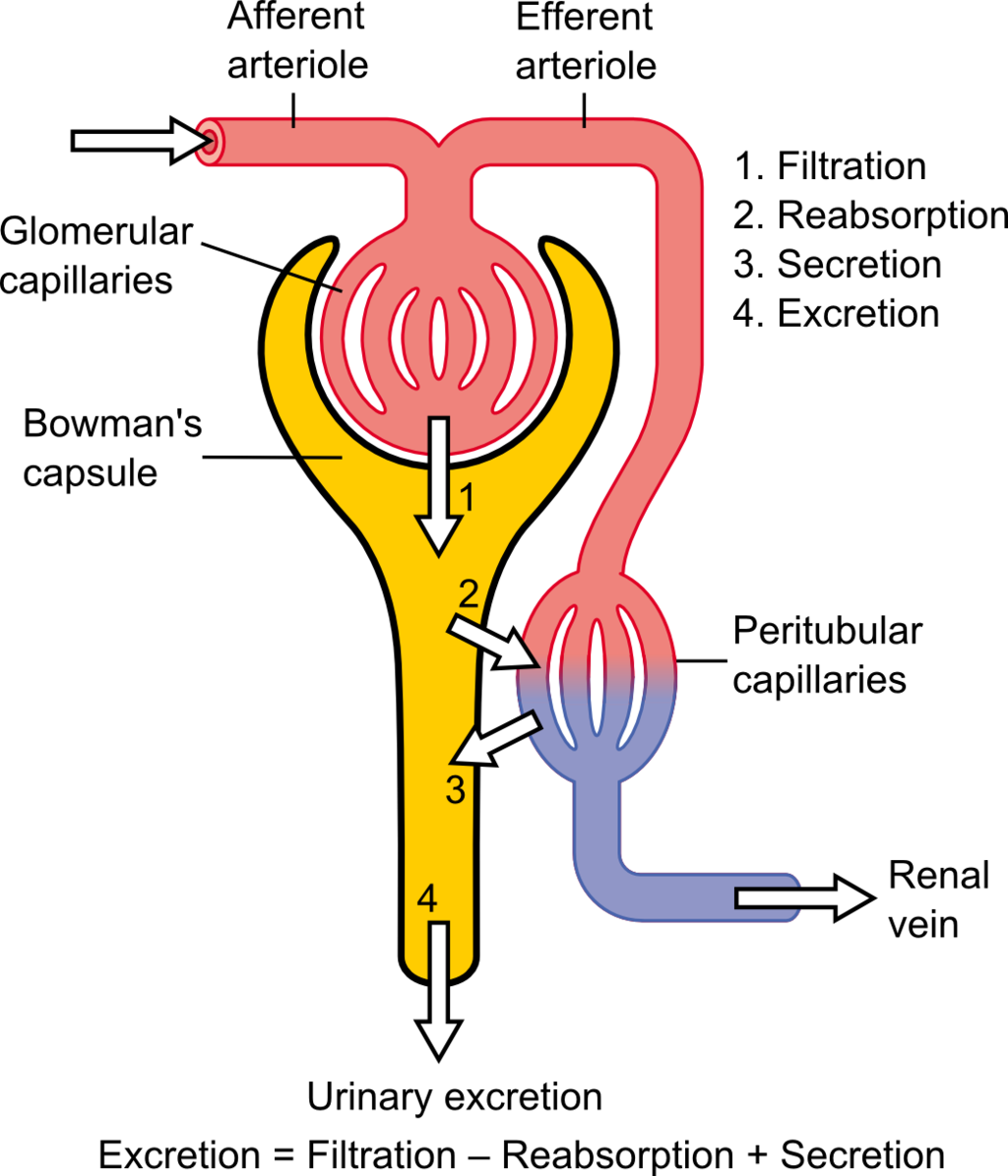

The simplified diagram of a nephron in Figure 16.4.6 shows an overview of how the nephron functions. Blood enters the nephron through an arteriole called the afferent arteriole. Next, some of the blood passes through the capillaries of the glomerulus. Any blood that doesn’t pass through the glomerulus — as well as blood after it passes through the glomerular capillaries — continues on through an arteriole called the efferent arteriole. The efferent arteriole follows the renal tubule of the nephron, where it continues playing a role in nephron functioning.

Filtration