8.6 Peripheral Nervous System

One Piano, Four Hands

Did you ever see two people play the same piano? How do they coordinate all the movements of their own fingers — let alone synchronize them with those of their partner? The peripheral nervous system plays an important part in this challenge.

What Is the Peripheral Nervous System?

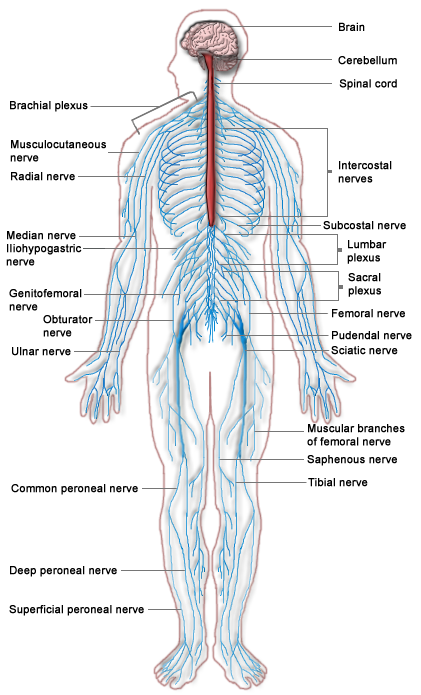

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside of the central nervous system (CNS). The main function of the PNS is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism. It serves as a communication relay, going back and forth between the CNS and muscles, organs, and glands throughout the body.

Tissues of the Peripheral Nervous System

The PNS is mostly made up of cable-like bundles of axons called nerves, as well as clusters of neuronal cell bodies called ganglia (singular, ganglion). Nerves are generally classified as sensory, motor, or mixed nerves based on the direction in which they carry nerve impulses.

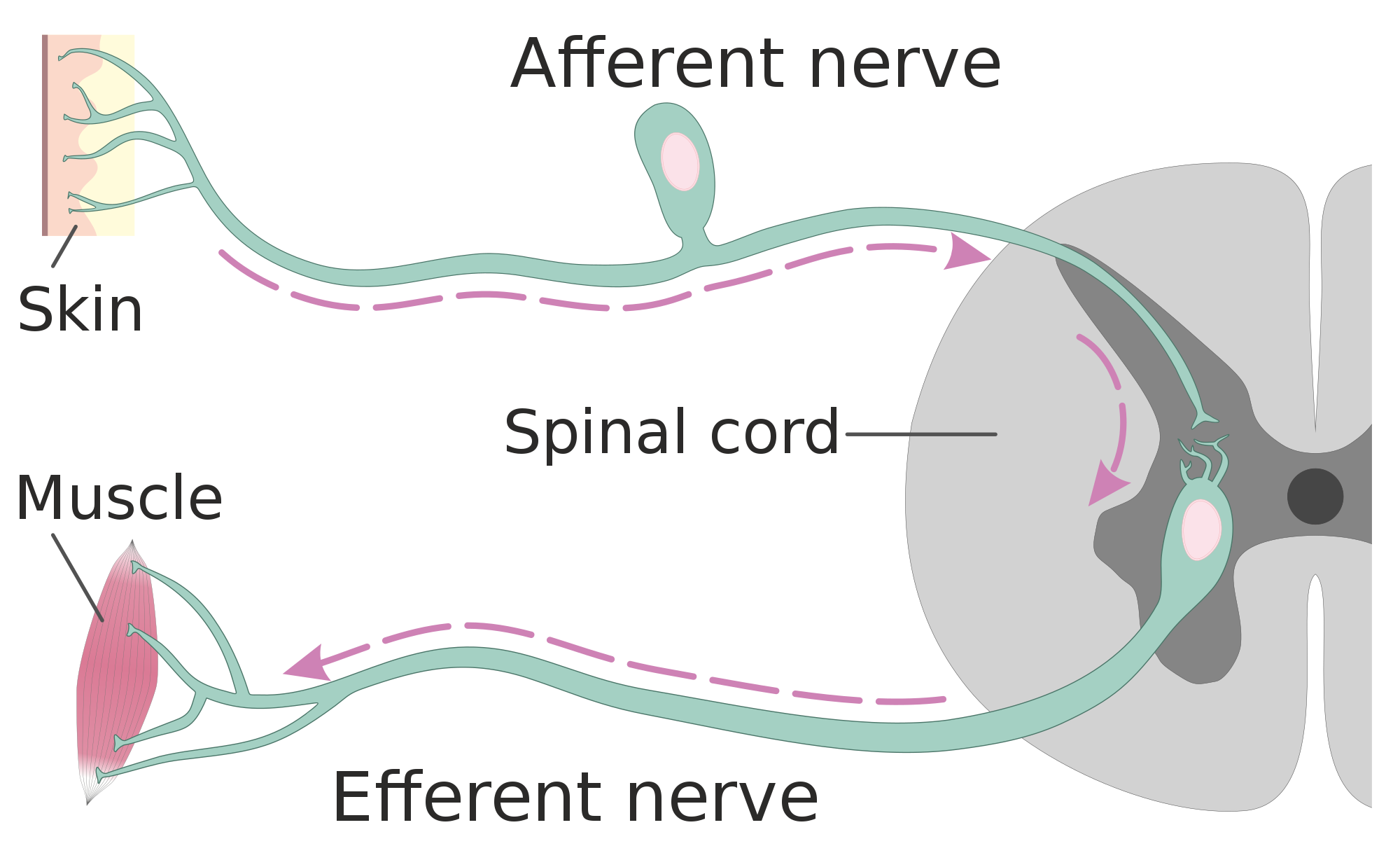

- Sensory nerves transmit information from sensory receptors in the body to the CNS. Sensory nerves are also called afferent nerves. You can see an example in the figure below.

- Motor nerves transmit information from the CNS to muscles, organs, and glands. Motor nerves are also called efferent nerves. You can see one in the figure below.

- Mixed nerves contain both sensory and motor neurons, so they can transmit information in both directions. They have both afferent and efferent functions.

Divisions of the Peripheral Nervous System

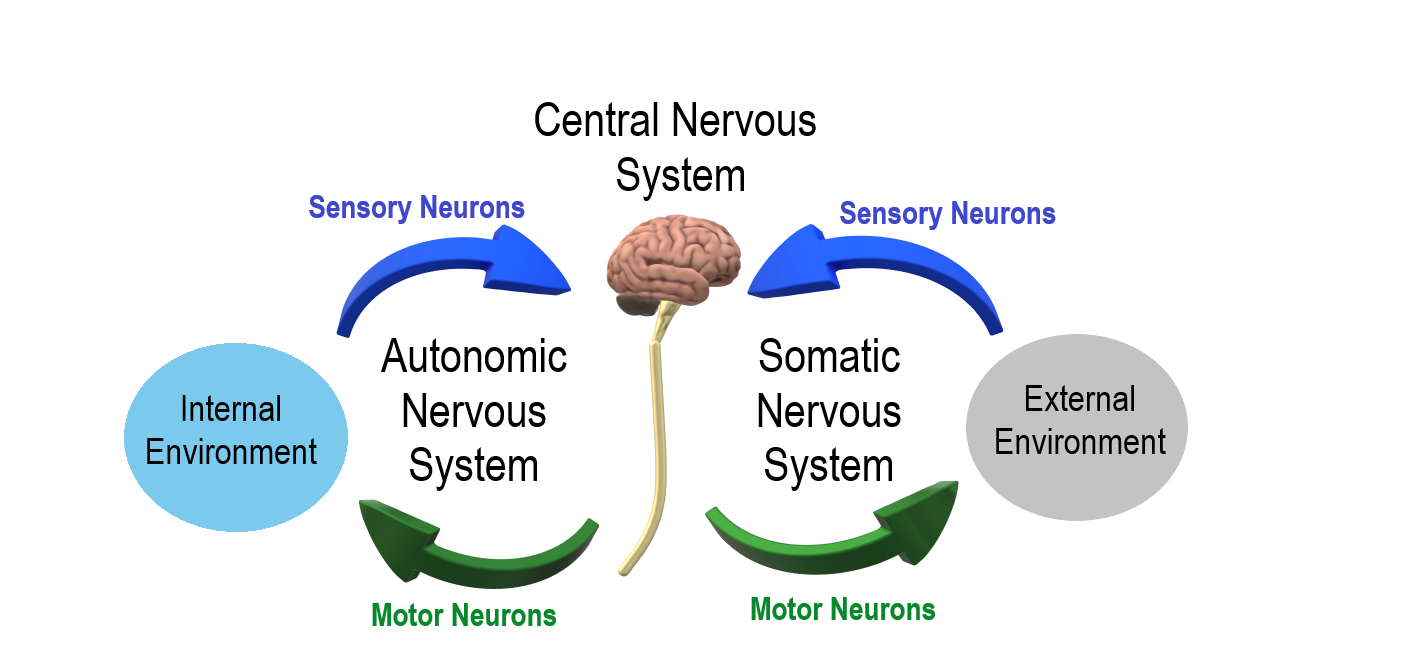

The PNS is divided into two major systems, called the autonomic nervous system and the somatic nervous system. In the diagram below, the autonomic system is shown on the left, and the somatic system on the right. Both systems of the PNS interact with the CNS and include sensory and motor neurons, but they use different circuits of nerves and ganglia.

Somatic Nervous System

The somatic nervous system primarily senses the external environment and controls voluntary activities about which decisions and commands come from the cerebral cortex of the brain. When you feel too warm, for example, you decide to turn on the air conditioner. As you walk across the room to the thermostat, you are using your somatic nervous system. In general, the somatic nervous system is responsible for all of your conscious perceptions of the outside world, as well as all of the voluntary motor activities you perform in response. Whether it’s playing a piano, driving a car, or playing basketball, you can thank your somatic nervous system for making it possible.

Somatic sensory and motor information is transmitted through 12 pairs of cranial nerves and 31 pairs of spinal nerves. Cranial nerves are in the head and neck and connect directly to the brain. Sensory components of cranial nerves transmit information about smells, tastes, light, sounds, and body position. Motor components of cranial nerves control skeletal muscles of the face, tongue, eyeballs, throat, head, and shoulders. Motor components of cranial nerves also control the salivary glands and swallowing. Four of the 12 cranial nerves participate in both sensory and motor functions as mixed nerves, having both sensory and motor neurons.

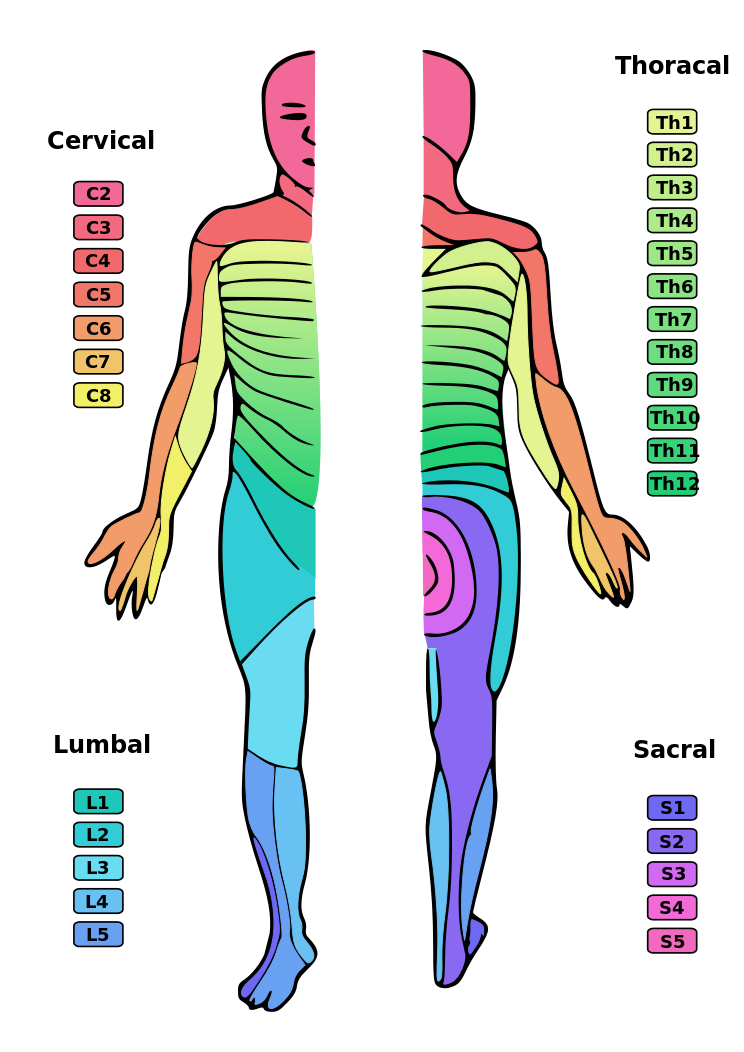

Spinal nerves emanate from the spinal column between vertebrae. All of the spinal nerves are mixed nerves, containing both sensory and motor neurons. The areas of skin innervated by the 31 pairs of spinal nerves are shown in the figure below. These include sensory nerves in the skin that sense pressure, temperature, vibrations, and pain. Other sensory nerves are in the muscles, and they sense stretching and tension. Spinal nerves also include motor nerves that stimulate skeletal muscles to contract, allowing for voluntary body movements.

Autonomic Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system primarily senses the internal environment and controls involuntary activities. It is responsible for monitoring conditions in the internal environment and bringing about appropriate changes in them. In general, the autonomic nervous system is responsible for all the activities that go on inside your body without your conscious awareness or voluntary participation.

Structurally, the autonomic nervous system consists of sensory and motor nerves that run between the CNS (especially the hypothalamus in the brain), internal organs (such as the heart, lungs, and digestive organs), and glands (such as the pancreas and sweat glands). Sensory neurons in the autonomic system detect internal body conditions and send messages to the brain. Motor nerves in the autonomic system affect appropriate responses by controlling contractions of smooth or cardiac muscle, or glandular tissue. For example, when sensory nerves of the autonomic system detect a rise in body temperature, motor nerves signal smooth muscles in blood vessels near the body surface to undergo vasodilation, and the sweat glands in the skin to secrete more sweat to cool the body.

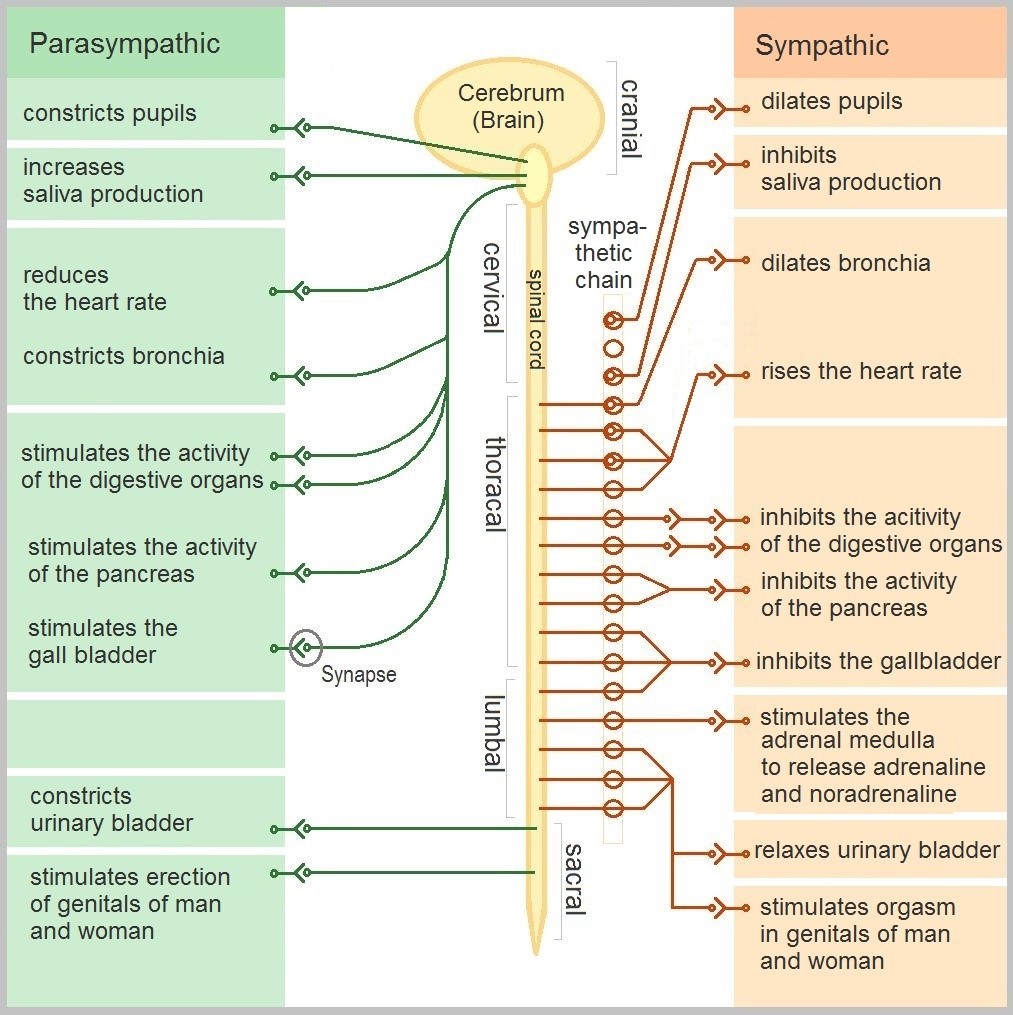

The autonomic nervous system, in turn, has three subdivisions: the sympathetic division, parasympathetic division, and enteric division. The first two subdivisions of the autonomic system are summarized in the figure below. Both affect the same organs and glands, but they generally do so in opposite ways.

- The sympathetic division controls the fight-or-flight response. Changes occur in organs and glands throughout the body that prepare the body to fight or flee in response to a perceived danger. For example, the heart rate speeds up, air passages in the lungs become wider, more blood flows to the skeletal muscles, and the digestive system temporarily shuts down.

- The parasympathetic division returns the body to normal after the fight-or-flight response has occurred. For example, it slows down the heart rate, narrows air passages in the lungs, reduces blood flow to the skeletal muscles, and stimulates the digestive system to start working again. The parasympathetic division also maintains internal homeostasis of the body at other times.

- The enteric division is made up of nerve fibres that supply the organs of the digestive system. This division allows for the local control of many digestive functions.

Disorders of the Peripheral Nervous System

Unlike the CNS — which is protected by bones, meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid — the PNS has no such protections. The PNS also has no blood-brain barrier to protect it from toxins and pathogens in the blood. Therefore, the PNS is more subject to injury and disease than is the CNS. Causes of nerve injury include diabetes, infectious diseases (such as shingles), and poisoning by toxins (such as heavy metals). PNS disorders often have symptoms like loss of feeling, tingling, burning sensations, or muscle weakness. If a traumatic injury results in a nerve being transected (cut all the way through), it may regenerate, but this is a very slow process and may take many months.

Two other diseases of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

- Guillain-Barre syndrome is a rare disease in which the immune system attacks nerves of the PNS, leading to muscle weakness and even paralysis. The exact cause of Guillain-Barre syndrome is unknown, but it often occurs after a viral or bacterial infection. There is no known cure for the syndrome, but most people eventually make a full recovery. Recovery can be slow, however, lasting anywhere from several weeks to several years.

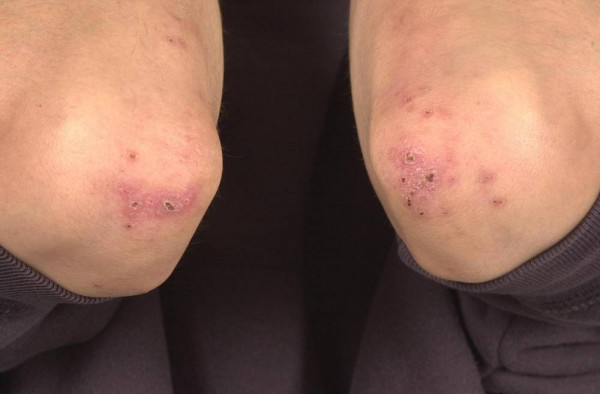

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is a hereditary disorder of the nerves, and one of the most common inherited neurological disorders. It affects predominantly the nerves in the feet and legs, and often in the hands and arms, as well. The disease is characterized by loss of muscle tissue and sense of touch. It is presently incurable.

Feature: My Human Body

The autonomic nervous system is considered to be involuntary because it doesn’t require conscious input. However, it is possible to exert some voluntary control over it. People who practice yoga or other so-called mind-body techniques, for example, can reduce their heart rate and certain other autonomic functions. Slowing down these otherwise involuntary responses is a good way to relieve stress and reduce the wear-and-tear that stress can place on the body. Such techniques may also be useful for controlling post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Three types of integrative practices for these purposes are breathing exercises, body-based tension modulation exercises, and mindfulness techniques.

Breathing exercises can help control the rapid, shallow breathing that often occurs when you are anxious or under stress. These exercises can be learned quickly, and they provide immediate feelings of relief. Specific breathing exercises include paced breath, diaphragmatic breathing, and Breathe2Relax or Chill Zone on MindShift™ CBT, which are downloadable breathing practice mobile applications, or “Apps”. Try syncing your breathing with Eric Klassen’s “Triangle breathing, 1 minute” video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9Q8D6n-3qw

Triangle breathing, 1 minute, Erin Klassen, 2015.

Body-based tension modulation exercises include yoga postures (also known as “asanas”) and tension manipulation exercises. The latter include the Trauma/Tension Release Exercise (TRE) and the Trauma Resiliency Model (TRM). Watch this video for a brief — but informative — introduction to the TRE program:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67R974D8swM&feature=youtu.be

TRE® : Tension and Trauma Releasing Exercises, an Introduction with Jessica Schaffer, Jessica Schaffer Nervous System RESET, 2015.

Mindfulness techniques have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression, as well as those of anxiety and stress. They have also been shown to be useful for pain management and performance enhancement. Specific mindfulness programs include Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness Mind-Fitness Training (MMFT). You can learn more about MBSR by watching the video below.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness), Palouse Mindfulness, 2017.

8.6 Summary

- The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all the nervous tissue that lies outside the central nervous system (CNS). Its main function is to connect the CNS to the rest of the organism.

- The PNS is made up of nerves and ganglia. Nerves are bundles of axons, and ganglia are groups of cell bodies. Nerves are classified as sensory, motor, or a mix of the two.

- The PNS is divided into the somatic and autonomic nervous systems. The somatic system controls voluntary activities, whereas the autonomic system controls involuntary activities.

- The autonomic nervous system is further divided into sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric divisions. The sympathetic division controls fight-or-flight responses during emergencies, the parasympathetic system controls routine body functions the rest of the time, and the enteric division provides local control over the digestive system.

- The PNS is not as well protected physically or chemically as the CNS, so it is more prone to injury and disease. PNS problems include injury from diabetes, shingles, and heavy metal poisoning. Two disorders of the PNS are Guillain-Barre syndrome and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

8.6 Review Questions

- Describe the general structure of the peripheral nervous system. State its primary function.

- What are ganglia?

- Identify three types of nerves based on the direction in which they carry nerve impulses.

- Outline all of the divisions of the peripheral nervous system.

- Compare and contrast the somatic and autonomic nervous systems.

- When and how does the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system affect the body?

- What is the function of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system? Specifically, how does it affect the body?

- Name and describe two peripheral nervous system disorders.

- Give one example of how the CNS interacts with the PNS to control a function in the body.

- For each of the following types of information, identify whether the neuron carrying it is sensory or motor, and whether it is most likely in the somatic or autonomic nervous system:

- Visual information

- Blood pressure information

- Information that causes muscle contraction in digestive organs after eating

- Information that causes muscle contraction in skeletal muscles based on the person’s decision to make a movement

-

8.6 Explore More

Phantom Limbs Explained, Plethrons, 2015.

Why Do Hot Peppers Cause Pain? Reactions, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 8.6.1

Kid’s piant duet by PJMixer on Flickr is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/) license.

Figure 8.6.2

Nervous_system_diagram by ¤~Persian Poet Gal on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.6.3

Afferent_and_efferent_neurons_en.svg by Helixitta on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 8.6.4

Autonomic and Somatic Nervous System by Christinelmiller on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 8.6.5

Dermatoms.svg by Ralf Stephan (mailto:ralf@ark.in-berlin.de) on Wikimedia Commons is released into the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 8.6.6

The_Autonomic_Nervous_System by Geo-Science-International on Wikimedia Commons is used and adapted by Christine Miller under a CC0 1.0 Universal

Public Domain Dedication license (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/).

References

Erin Klassen. (2015, December 15). Triangle breathing, 1 minute. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u9Q8D6n-3qw&feature=youtu.be

Jessica Schaffer Nervous System RESET. (2015, January 15). TRE® : Tension and trauma releasing exercises, an Introduction with Jessica Schaffer. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67R974D8swM&feature=youtu.be

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/charcot-marie-tooth-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350517

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Diabetes [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20371444

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Guillain-Barre syndrome [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/guillain-barre-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20362793

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Shingles [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/shingles/symptoms-causes/syc-20353054

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Stroke [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/stroke/symptoms-causes/syc-20350113

Palouse Mindfulness. (2017, March 25). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (UMass Medical School, Center for Mindfulness), YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TA7P-iCCcY&feature=youtu.be

Plethrons, (2015, March 23). Phantom limbs explained. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySIDMU2cy0Y&feature=youtu.be

Reactions. (2015, December 1). Why do hot peppers cause pain? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=73yo5nJne6c&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Figure 16.3.1 The surprising uses of pee.

Surprising Uses

What do gun powder, leather, fabric dyes and laundry service have in common? This may be surprising, but they all historically involved urine. One of the main components in gun powder, potassium nitrate, was difficult to come by pre-1900s, so ingenious gun-owners would evaporate urine to concentrate the nitrates it contains. The ammonium in urine was excellent in breaking down tissues, making it a prime candidate for softening leathers and removing stains in laundry. Ammonia in urine also helps dyes penetrate fabrics, so it was used to make colours stay brighter for longer.

What is the Urinary System?

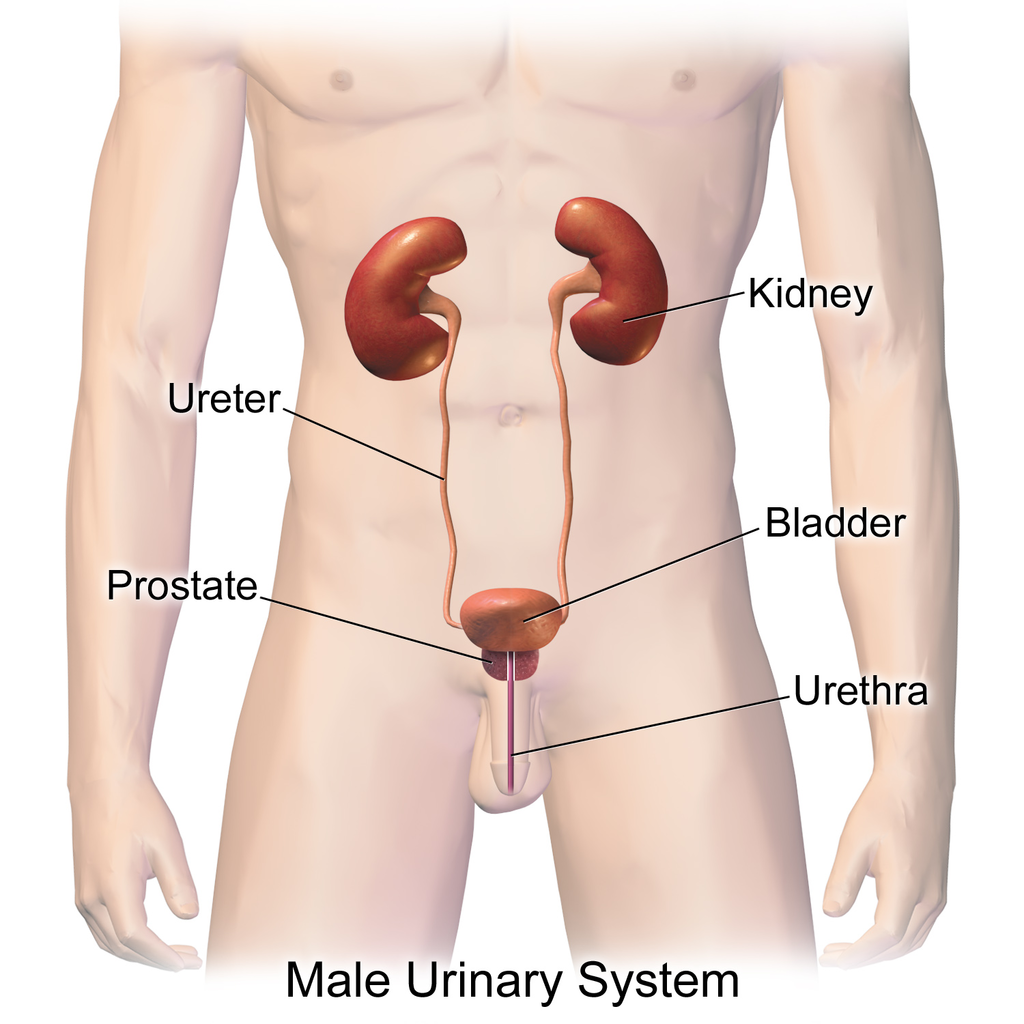

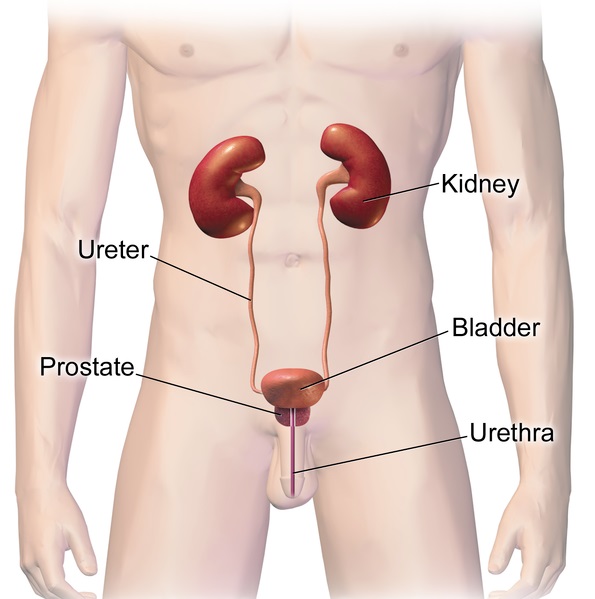

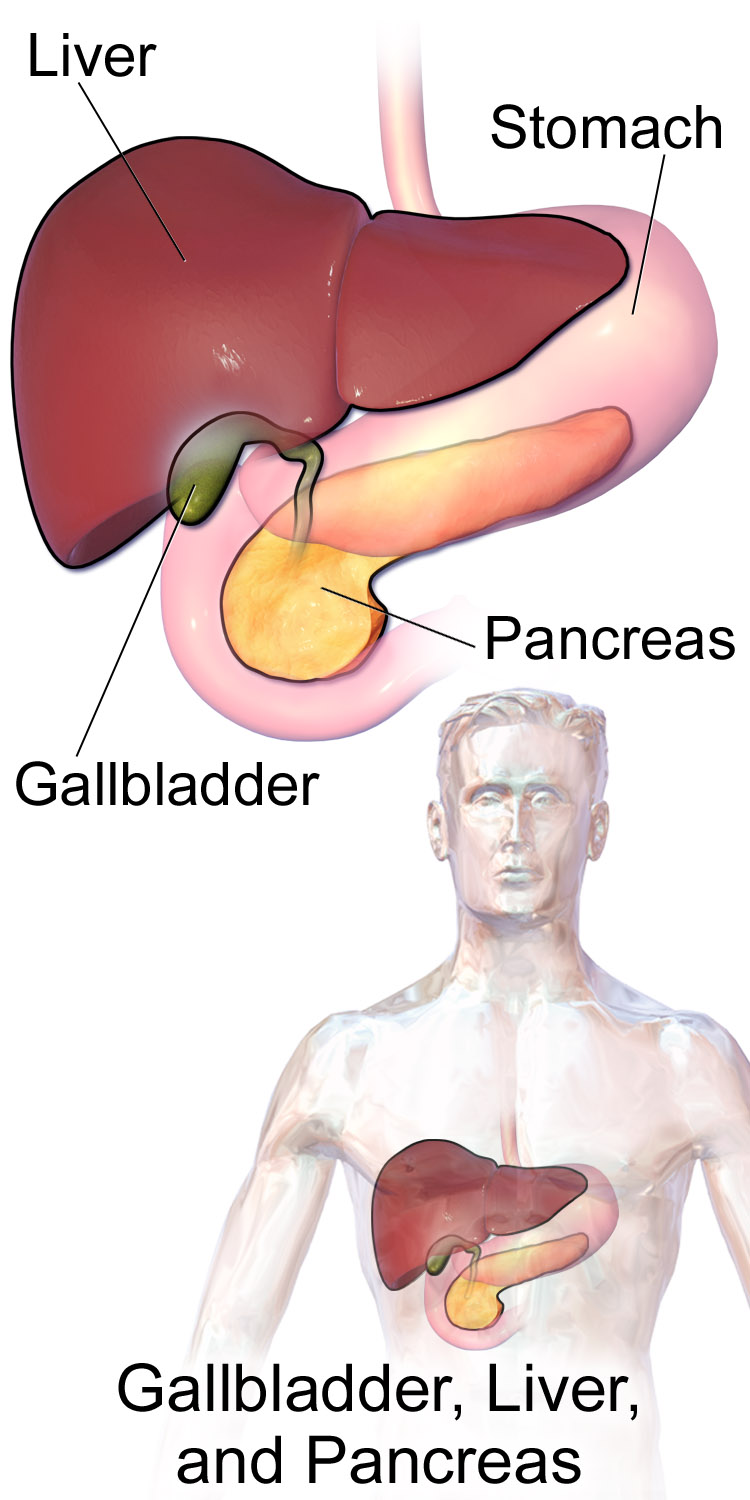

The actual human urinary system, also known as the renal system, is shown in Figure 16.3.2. The system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The main function of the urinary system is to eliminate the waste products of metabolism from the body by forming and excreting urine. Typically, between one and two litres of urine are produced every day in a healthy individual.

Organs of the Urinary System

The urinary system is all about urine. It includes organs that form urine, and also those that transport, store, or excrete urine.

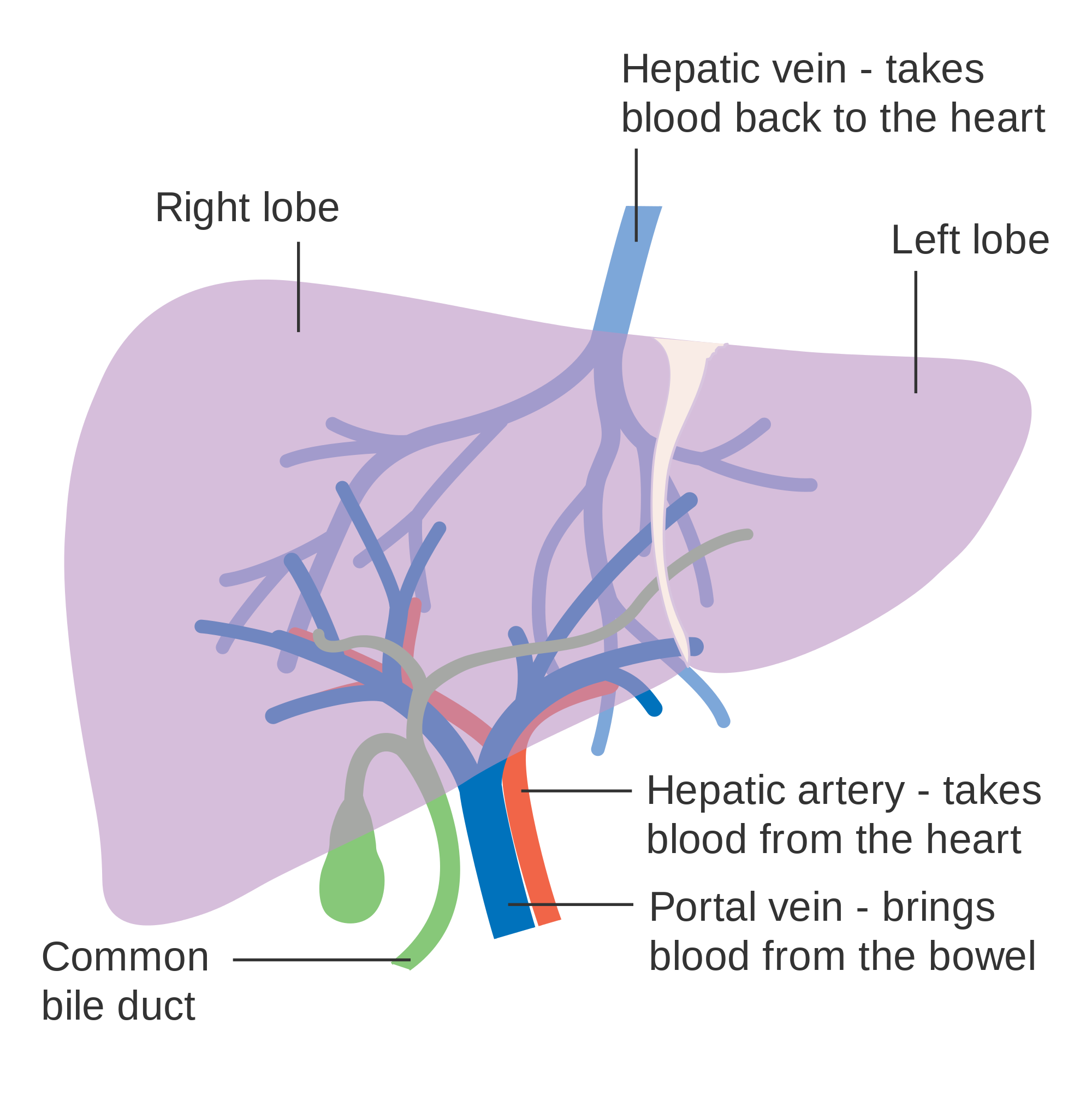

Kidneys

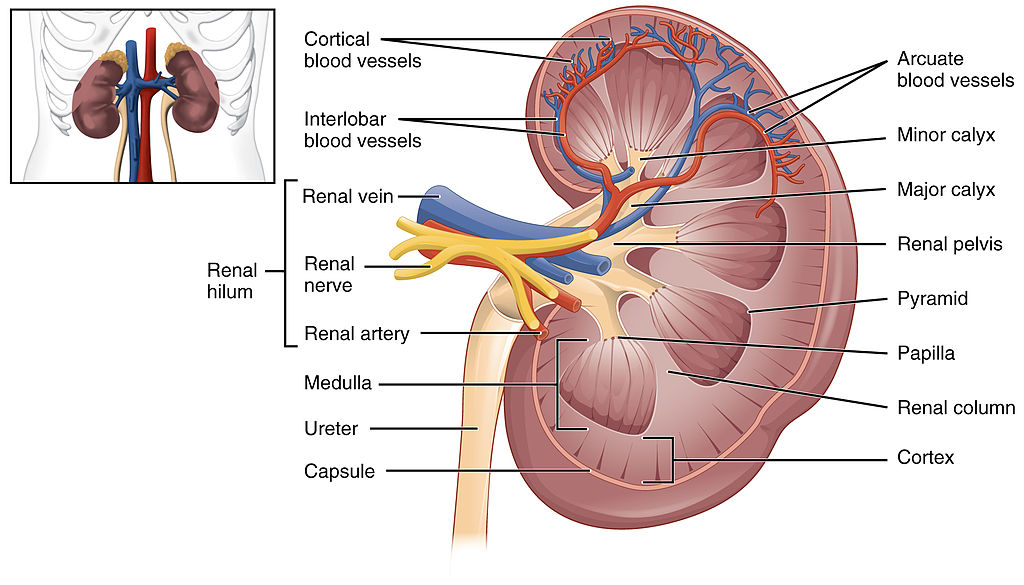

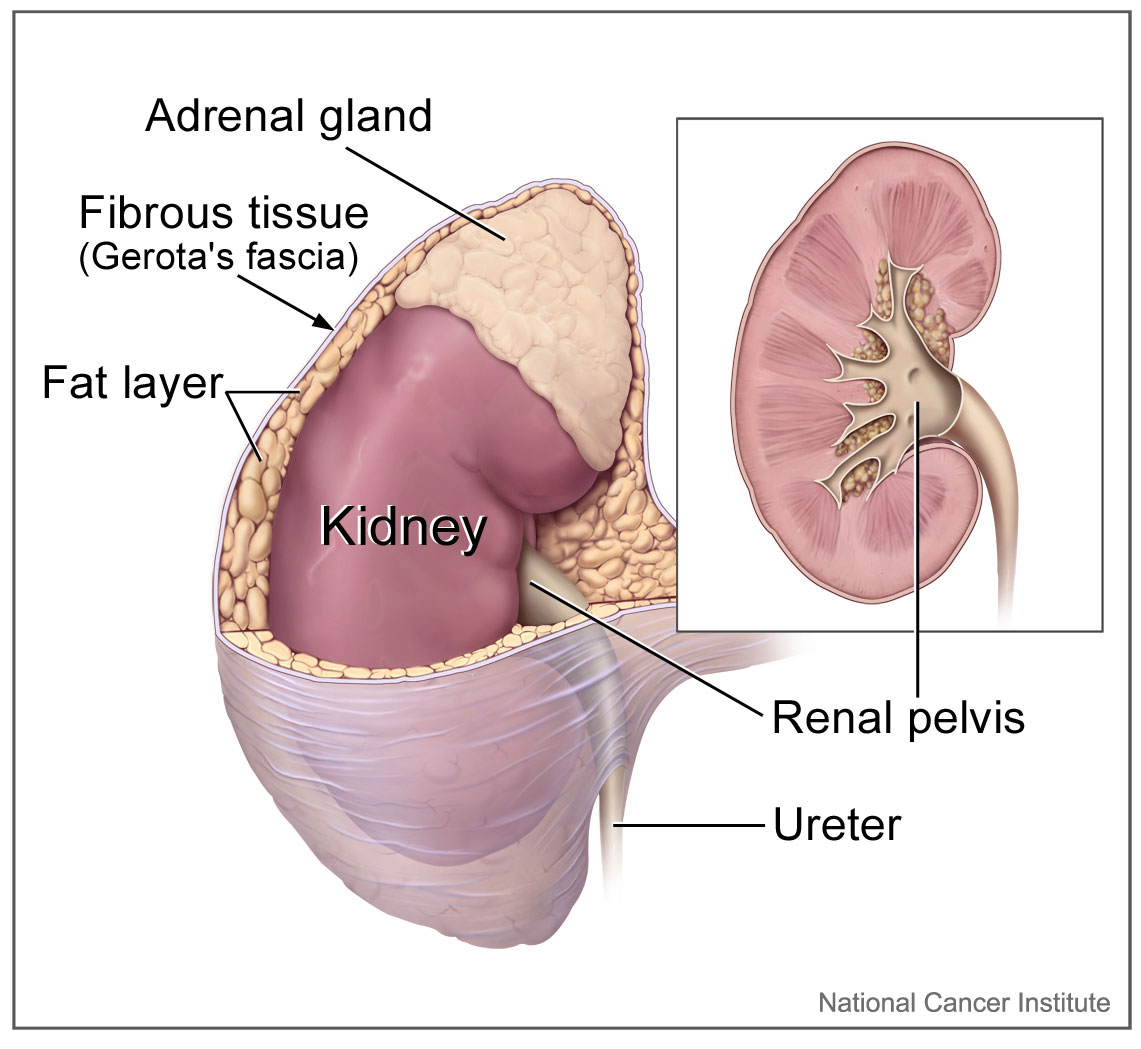

Urine is formed by the kidneys, which filter many substances out of the blood, allow the blood to reabsorb needed materials, and use the remaining materials to form urine. The human body normally has two paired kidneys, although it is possible to get by quite well with just one. As you can see in Figure 16.3.3, each kidney is well supplied with blood vessels by a major artery and vein. Blood to be filtered enters the kidney through the renal artery, and the filtered blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein. The kidney itself is wrapped in a fibrous capsule, and consists of a thin outer layer called the cortex, and a thicker inner layer called the medulla.

Blood is filtered and urine is formed by tiny filtering units called nephrons. Each kidney contains at least a million nephrons, and each nephron spans the cortex and medulla layers of the kidney. After urine forms in the nephrons, it flows through a system of converging collecting ducts. The collecting ducts join together to form minor calyces (or chambers) that join together to form major calyces (see Figure 16.3.3 above). Ultimately, the major calyces join the renal pelvis, which is the funnel-like end of the ureter where it enters the kidney.

Ureters, Bladder, Urethra

After urine forms in the kidneys, it is transported through the ureters (one per kidney) via peristalsis to the sac-like urinary bladder, which stores the urine until urination. During urination, the urine is released from the bladder and transported by the urethra to be excreted outside the body through the external urethral opening.

Functions of the Urinary System

Waste products removed from the body with the formation and elimination of urine include many water-soluble metabolic products. The main waste products are urea — a by-product of protein catabolism — and uric acid, a by-product of nucleic acid catabolism. Excess water and mineral ions are also eliminated in urine.

Besides the elimination of waste products such as these, the urinary system has several other vital functions. These include:

- Maintaining homeostasis of mineral ions in extracellular fluid: These ions are either excreted in urine or returned to the blood as needed to maintain the proper balance.

- Maintaining homeostasis of blood pH: When pH is too low (blood is too acidic), for example, the kidneys excrete less bicarbonate (which is basic) in urine. When pH is too high (blood is too basic), the opposite occurs, and more bicarbonate is excreted in urine.

- Maintaining homeostasis of extracellular fluids, including the blood volume, which helps maintain blood pressure: The kidneys control fluid volume and blood pressure by excreting more or less salt and water in urine.

Control of the Urinary System

The formation of urine must be closely regulated to maintain body-wide homeostasis. Several endocrine hormones help control this function of the urinary system, including antidiuretic hormone, parathyroid hormone, and aldosterone.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also called vasopressin, is secreted by the posterior pituitary gland. One of its main roles is conserving body water. It is released when the body is dehydrated, and it causes the kidneys to excrete less water in urine.

- Parathyroid hormone is secreted by the parathyroid glands. It works to regulate the balance of mineral ions in the body via its effects on several organs, including the kidneys. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the kidneys to excrete less calcium and more phosphorus in urine.

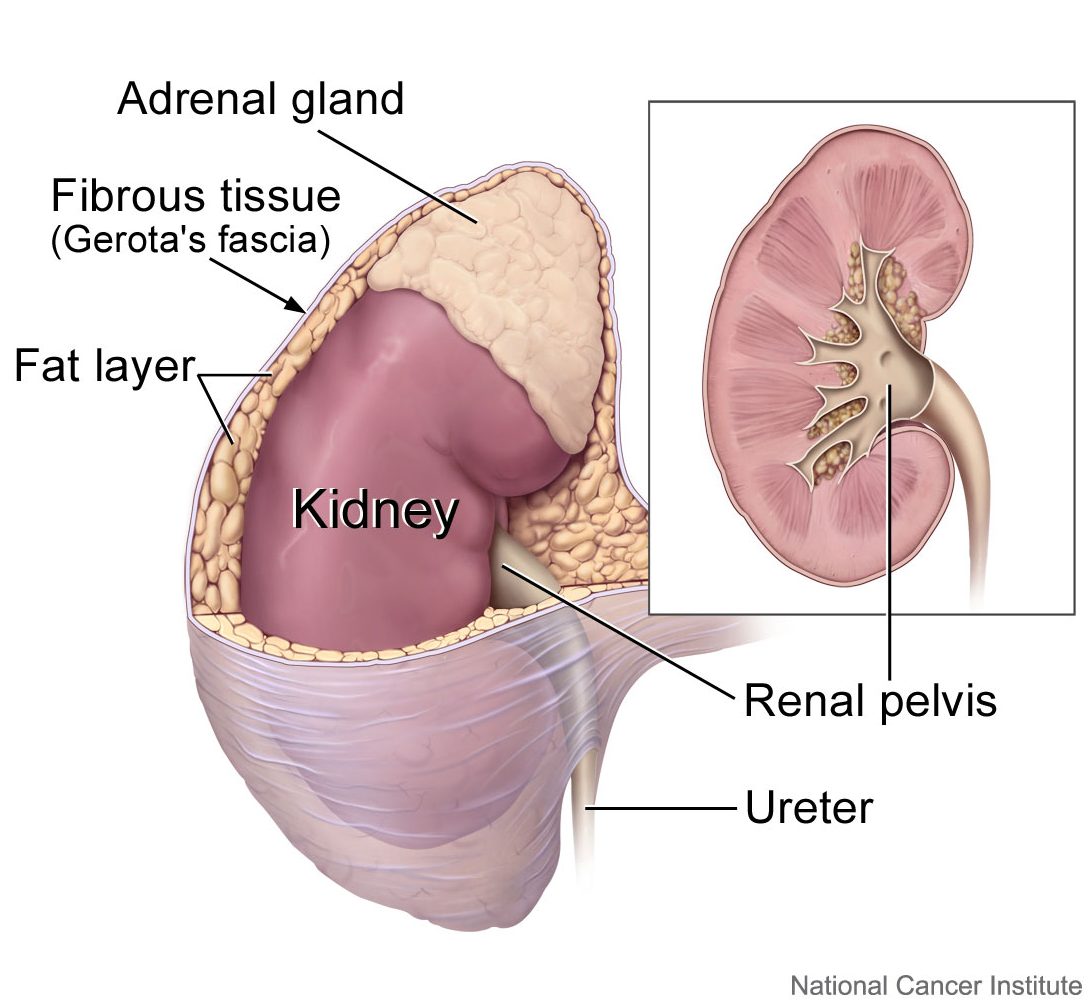

- Aldosterone is secreted by the cortex of the adrenal glands, which rest atop the kidneys, as shown in Figure 16.3.4. Through its effect on the kidneys, it plays a central role in regulating blood pressure. It causes the kidneys to excrete less sodium and water in urine.

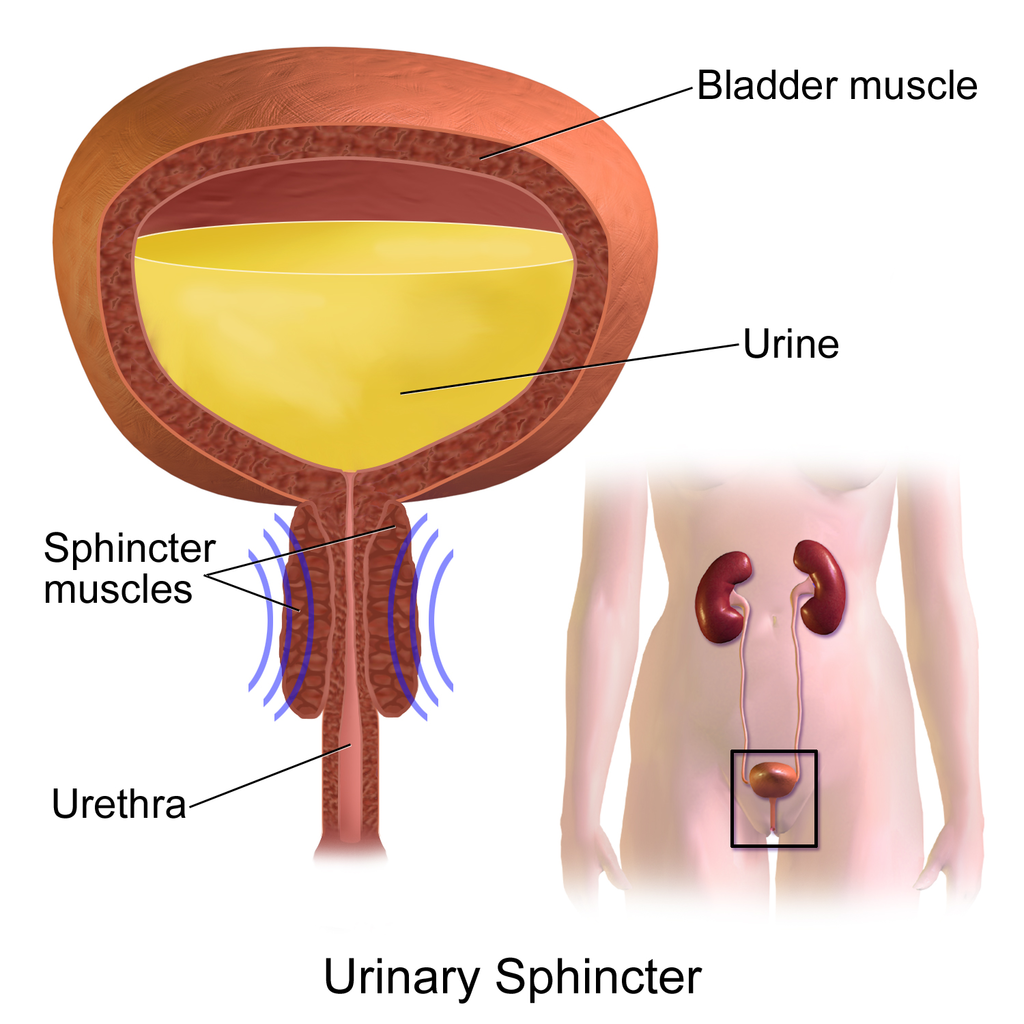

Once urine forms, it is excreted from the body in the process of urination, also sometimes referred to as micturition. This process is controlled by both the autonomic and the somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills with urine, it causes the autonomic nervous system to signal smooth muscle in the bladder wall to contract (as shown in Figure 16.3.5), and the sphincter between the bladder and urethra to relax and open. This forces urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Another sphincter at the distal end of the urethra is under voluntary control. When it relaxes under the influence of the somatic nervous system, it allows urine to leave the body through the external urethral opening.

16.3 Summary

- The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The main function of the urinary system is to eliminate the waste products of metabolism from the body by forming and excreting urine.

- Urine is formed by the kidneys, which filter many substances out of blood, allow the blood to reabsorb needed materials, and use the remaining materials to form urine. Blood to be filtered enters the kidney through the renal artery, and filtered blood leaves the kidney through the renal vein.

- Within each kidney, blood is filtered and urine is formed by tiny filtering units called nephrons, of which there are at least a million in each kidney.

- After urine forms in the kidneys, it is transported through the ureters via peristalsis to the urinary bladder. The bladder stores the urine until urination, when urine is transported by the urethra to be excreted outside the body.

- Besides the elimination of waste products (such as urea, uric acid, excess water, and mineral ions), the urinary system has other vital functions. These include maintaining homeostasis of mineral ions in extracellular fluid, regulating acid-base balance in the blood, regulating the volume of extracellular fluids, and controlling blood pressure.

- The formation of urine must be closely regulated to maintain body-wide homeostasis. Several endocrine hormones help control this function of the urinary system, including antidiuretic hormone from the posterior pituitary gland, parathyroid hormone from the parathyroid glands, and aldosterone from the adrenal glands.

- The process of urination is controlled by both the autonomic and the somatic nervous systems. The autonomic system causes the bladder to empty, but conscious relaxation of the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra allows urine to leave the body.

16.3 Review Questions

-

- State the main function of the urinary system.

- What are nephrons?

- Other than the elimination of waste products, identify functions of the urinary system.

- How is the formation of urine regulated?

- Explain why it is important to have voluntary control over the sphincter at the end of the urethra.

- In terms of how they affect the kidneys, compare aldosterone to antidiuretic hormone.

- If your body needed to retain more calcium, which of the hormones described in this concept is most likely to increase? Explain your reasoning.

16.3 Explore More

https://youtu.be/dxecGD0m0Xc

The Urinary System - An Introduction | Physiology | Biology | FuseSchool, 2017.

https://youtu.be/pyMcTUQYMQw

Maple Syrup Urine Disease, Alexandria Doody, 2016.

https://youtu.be/3z-xjfdJWAI

How Accurate Are Drug Tests? Seeker, 2016.

https://youtu.be/xt1Tj5eeS0k

Three Ways Pee Could Change the World, Gross Science, 2015.

Attributions

Figure 16.3.1

- File:Pyrodex powder ffg.jpg by Hustvedt on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en).

- Brown leather satchel bag by Álvaro Serrano on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Laundry basket by Andy Fitzsimon on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash Licence (https://unsplash.com/license).

- Tags: Wool Skeins Natural Dyed Colorful Himalayan Weavers by on Pixabay is used under the Pixabay License (https://pixabay.com/service/license/).

Figure 16.3.2

Urinary_System_(Male) by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.3.3

2610_The_Kidney by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 16.3.4

Adrenal glands on Kidney by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator)/ NCI Visuals Online is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.3.5

Urinary_Sphincter by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Alexandria Doody. (2016, March 29). Maple syrup urine disease. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pyMcTUQYMQw&feature=youtu.be

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.8 Left kidney [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 25.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-3-gross-anatomy-of-the-kidney

FuseSchool. (2017, June 19). The urinary system - An introduction | Physiology | Biology | FuseSchool. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dxecGD0m0Xc&feature=youtu.be

Gross Science. (2015, September 15). Three ways pee could change the world. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xt1Tj5eeS0k&feature=youtu.be

Seeker. (2016, January 16). How accurate are drug tests? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3z-xjfdJWAI&feature=youtu.be

One of two main divisions of the nervous system that includes the brain and spinal cord.

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Communicating with Urine

Why do dogs pee on fire hydrants? Besides “having to go,” they are marking their territory with chemicals in their urine called pheromones. It’s a form of communication, in which they are “saying” with odors that the yard is theirs and other dogs should stay away. In addition to fire hydrants, dogs may urinate on fence posts, trees, car tires, and many other objects. Urination in dogs, as in people, is usually a voluntary process controlled by the brain. The process of forming urine — which occurs in the kidneys — occurs constantly, and is not under voluntary control. What happens to all the urine that forms in the kidneys? It passes from the kidneys through the other organs of the urinary system, starting with the ureters.

Ureters

As shown in Figure 16.5.2, ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. They are paired structures, with one ureter for each kidney. In adults, ureters are between 25 and 30 cm (about 10–12 in) long and about 3 to 4 mm in diameter.

Each ureter arises in the pelvis of a kidney (the renal pelvis in Figure 16.5.3). It then passes down the side of the kidney, and finally enters the back of the bladder. At the entrance to the bladder, the ureters have sphincters that prevent the backflow of urine.

The walls of the ureters are composed of multiple layers of different types of tissues. The innermost layer is a special type of epithelium, called transitional epithelium. Unlike the epithelium lining most organs, transitional epithelium is capable of stretching and does not produce mucus. It lines much of the urinary system, including the renal pelvis, bladder, and much of the urethra, in addition to the ureters. Transitional epithelium allows these organs to stretch and expand as they fill with urine or allow urine to pass through. The next layer of the ureter walls is made up of loose connective tissue containing elastic fibres, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. After this layer are two layers of smooth muscles, an inner circular layer, and an outer longitudinal layer. The smooth muscle layers can contract in waves of peristalsis to propel urine down the ureters from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The outermost layer of the ureter walls consists of fibrous tissue.

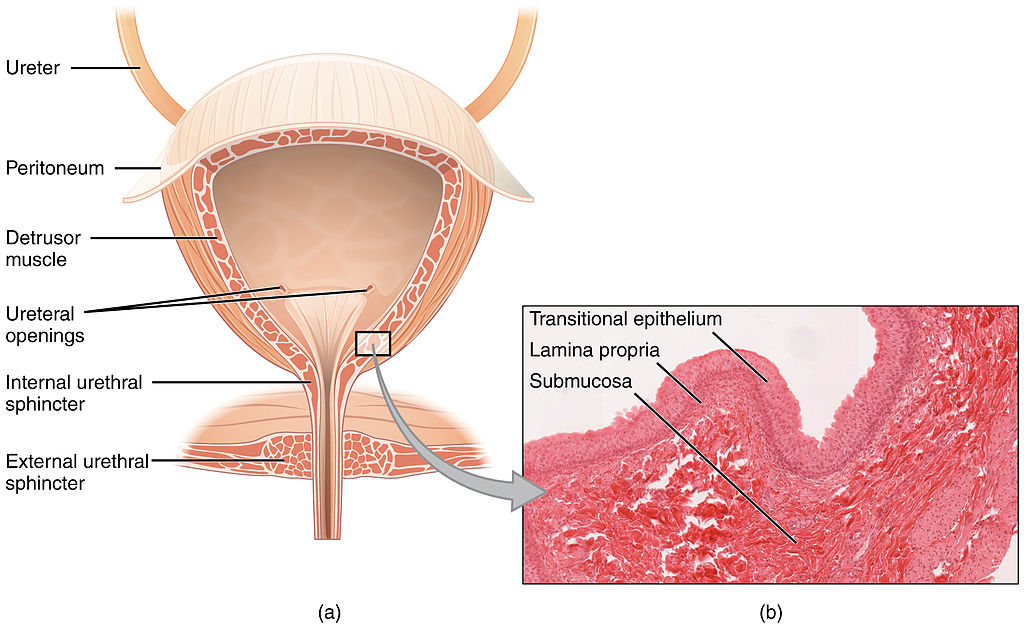

Urinary Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and stretchy organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It collects and stores urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. As shown in Figure 16.5.4, urine enters the urinary bladder from the ureters through two ureteral openings on either side of the back wall of the bladder. Urine leaves the bladder through a sphincter called the internal urethral sphincter. When the sphincter relaxes and opens, it allows urine to flow out of the bladder and into the urethra.

Like the ureters, the bladder is lined with transitional epithelium, which can flatten out and stretch as needed as the bladder fills with urine. The next layer (lamina propria) is a layer of loose connective tissue, nerves, and blood and lymphatic vessels. This is followed by a submucosa layer, which connects the lining of the bladder with the detrusor muscle in the walls of the bladder. The outer covering of the bladder is peritoneum, which is a smooth layer of epithelial cells that lines the abdominal cavity and covers most abdominal organs.

The detrusor muscle in the wall of the bladder is made of smooth muscle fibres controlled by both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems. As the bladder fills, the detrusor muscle automatically relaxes to allow it to hold more urine. When the bladder is about half full, the stretching of the walls triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When the individual is ready to void, conscious nervous signals cause the detrusor muscle to contract, and the internal urethral sphincter to relax and open. As a result, urine is forcefully expelled out of the bladder and into the urethra.

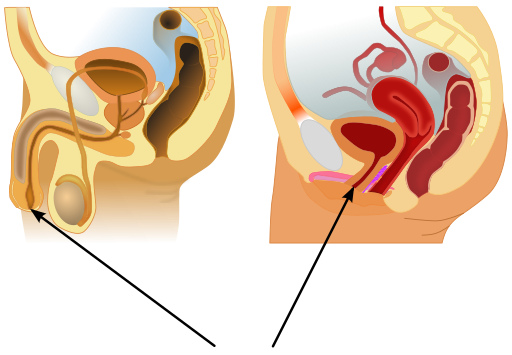

Urethra

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice, which is the opening of the urethra on the surface of the body. As shown in Figure 16.5.5, the urethra in males travels through the penis, so it is much longer than the urethra in females. In males, the urethra averages about 20 cm (about 7.8 in) long, whereas in females, it averages only about 4.8 cm (about 1.9 in) long. In males, the urethra carries semen (as well as urine), but in females, it carries only urine. In addition, in males, the urethra passes through the prostate gland (part of the reproductive system) which is absent in women.

Like the ureters and bladder, the proximal (closer to the bladder) two-thirds of the urethra are lined with transitional epithelium. The distal (farther from the bladder) third of the urethra is lined with mucus-secreting epithelium. The mucus helps protect the epithelium from urine, which is corrosive. Below the epithelium is loose connective tissue, and below that are layers of smooth muscle that are continuous with the muscle layers of the urinary bladder. When the bladder contracts to forcefully expel urine, the smooth muscle of the urethra relaxes to allow the urine to pass through.

In order for urine to leave the body through the external urethral orifice, the external urethral sphincter must relax and open. This sphincter is a striated muscle that is controlled by the somatic nervous system, so it is under conscious, voluntary control in most people (exceptions are infants, some elderly people, and patients with certain injuries or disorders). The muscle can be held in a contracted state and hold in the urine until the person is ready to urinate. Following urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra automatically contracts to re-establish muscle tone, and the individual consciously contracts the external urethral sphincter to close the external urethral opening.

16.5 Summary

- Ureters are tube-like structures that connect the kidneys with the urinary bladder. Each ureter arises at the renal pelvis of a kidney and travels down through the abdomen to the urinary bladder. The walls of the ureter contain smooth muscle that can contract to push urine through the ureter by peristalsis. The walls are lined with transitional epithelium that can expand and stretch.

- The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular organ that rests on the pelvic floor. It is also lined with transitional epithelium. The function of the bladder is to collect and store urine from the kidneys before the urine is eliminated through urination. Filling of the bladder triggers the sensation of needing to urinate. When a conscious decision to urinate is made, the detrusor muscle in the bladder wall contracts and forces urine out of the bladder and into the urethra.

- The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral orifice. Somatic nerves control the sphincter at the distal end of the urethra. This allows the opening of the sphincter for urination to be under voluntary control.

16.5 Review Questions

- What are ureters? Describe the location of the ureters relative to other urinary tract organs.

- Identify layers in the walls of a ureter. How do they contribute to the ureter’s function?

- Describe the urinary bladder. What is the function of the urinary bladder?

-

- How does the nervous system control the urinary bladder?

- What is the urethra?

- How does the nervous system control urination?

- Identify the sphincters that are located along the pathway from the ureters to the external urethral orifice.

- What are two differences between the male and female urethra?

- When the bladder muscle contracts, the smooth muscle in the walls of the urethra _________ .

16.5 Explore More

https://youtu.be/2Brajdazp1o

The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter, TED. 2016.

https://youtu.be/dg4_deyHLvQ

What Happens When You Hold Your Pee? SciShow, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 16.5.1

Cliche by Jackie on Wikimedia Common s is used under a CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0) license.

Figure 16.5.2

Urinary System Male by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 16.5.3

Adrenal glands on Kidney by NCI Public Domain by Alan Hoofring (Illustrator) /National Cancer Institute (photo ID 4355) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 16.5.4

2605_The_Bladder by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license. (Micrograph originally provided by the Regents of the University of Michigan Medical School © 2012.)

Figure 16.5.5

512px-Male_and_female_urethral_openings.svg by andrybak (derivative work) on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) license. (Original: Male anatomy blank.svg: alt.sex FAQ, derivative work: Tsaitgaist Female anatomy with g-spot.svg: Tsaitgaist.)

References

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 25.4 Bladder (a) Anterior cross section of the bladder. (b) The detrusor muscle of the bladder (source: monkey tissue) LM × 448 [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 7.3). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/25-2-gross-anatomy-of-urine-transport

SciShow. (2016, January 22). What happens when you hold your pee? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dg4_deyHLvQ&feature=youtu.be

TED. (2016, September 2). The taboo secret to better health | Molly Winter. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Brajdazp1o&feature=youtu.be

A structure containing neuronal cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system.

Structures containing neuronal cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system.

image shows the signs for mens and women's washroom.

As per caption.

division of the peripheral nervous system that controls involuntary activities

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Worm Attack!

Does the organism in Figure 17.2.1 look like a space alien? A scary creature from a nightmare? In fact, it’s a 1-cm long worm in the genus Schistosoma. It may invade and take up residence in the human body, causing a very serious illness known as schistosomiasis. The worm gains access to the human body while it is in a microscopic life stage. It enters through a hair follicle when the skin comes into contact with contaminated water. The worm then grows and matures inside the human organism, causing disease.

Host vs. Pathogen

The Schistosoma worm has a parasitic relationship with humans. In this type of relationship, one organism, called the parasite, lives on or in another organism, called the host. The parasite always benefits from the relationship, and the host is always harmed. The human host of the Schistosoma worm is clearly harmed by the parasite when it invades the host’s tissues. The urinary tract or intestines may be infected, and signs and symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody stool, or blood in the urine. Those who have been infected for a long time may experience liver damage, kidney failure, infertility, or bladder cancer. In children, Schistosoma infection may cause poor growth and difficulty learning.

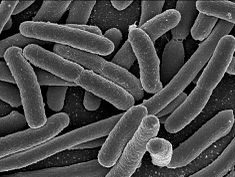

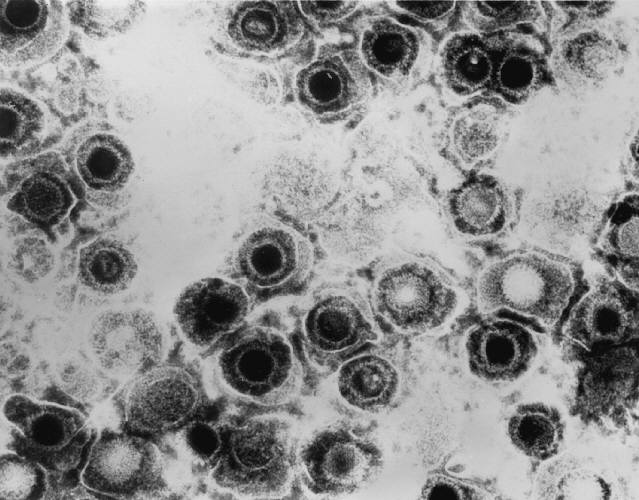

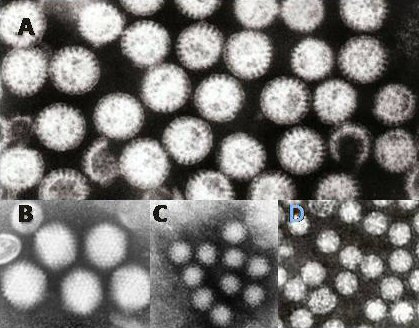

Like the Schistosoma worm, many other organisms can make us sick if they manage to enter our body. Any such agent that can cause disease is called a pathogen. Most pathogens are microorganisms, although some — such as the Schistosoma worm — are much larger. In addition to worms, common types of pathogens of human hosts include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and single-celled organisms called protists. You can see examples of each of these types of pathogens in Table 17.1.1. Fortunately for us, our immune system is able to keep most potential pathogens out of the body, or quickly destroy them if they do manage to get in. When you read this chapter, you’ll learn how your immune system usually keeps you safe from harm — including from scary creatures like the Schistosoma worm!

| Type of Pathogen | Description | Disease Caused | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria:

Example shown: Escherichia coli |

|

Single celled organisms without a nucleus | Strep throat, staph infections, tuberculosis, food poisoning, tetanus, pneumonia, syphillis |

| Viruses:

Example shown: Herpes simplex |

|

Non-living particles that reproduce by taking over living cells | Common cold, flu, genital herpes, cold sores, measles, AIDS, genital warts, chicken pox, small pox |

| Fungi:

Example shown: Death cap mushroom |

|

Simple organisms, including mushrooms and yeast, that grow as single cells or thread-like filaments | Ringworm, athletes foot, tineas, candidias, histoplasmomis, mushroom poisoning |

| Protozoa:

Example shown: Giardia lamblia |

|

Single celled organisms with a nucleus | Malaria, "traveller's diarrhea", giardiasis, typano somiasis ("sleeping sickness") |

What is the Immune System?

The immune system is a host defense system. It comprises many biological structures —ranging from individual leukocytes to entire organs — as well as many complex biological processes. The function of the immune system is to protect the host from pathogens and other causes of disease, such as tumor (cancer) cells. To function properly, the immune system must be able to detect a wide variety of pathogens. It also must be able to distinguish the cells of pathogens from the host’s own cells, and also to distinguish cancerous or damaged host cells from healthy cells. In humans and most other vertebrates, the immune system consists of layered defenses that have increasing specificity for particular pathogens or tumor cells. The layered defenses of the human immune system are usually classified into two subsystems, called the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system.

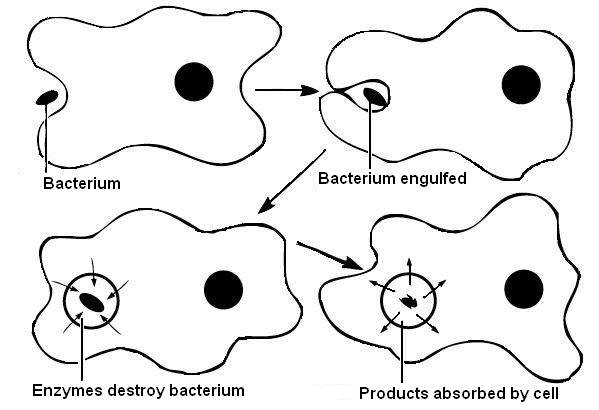

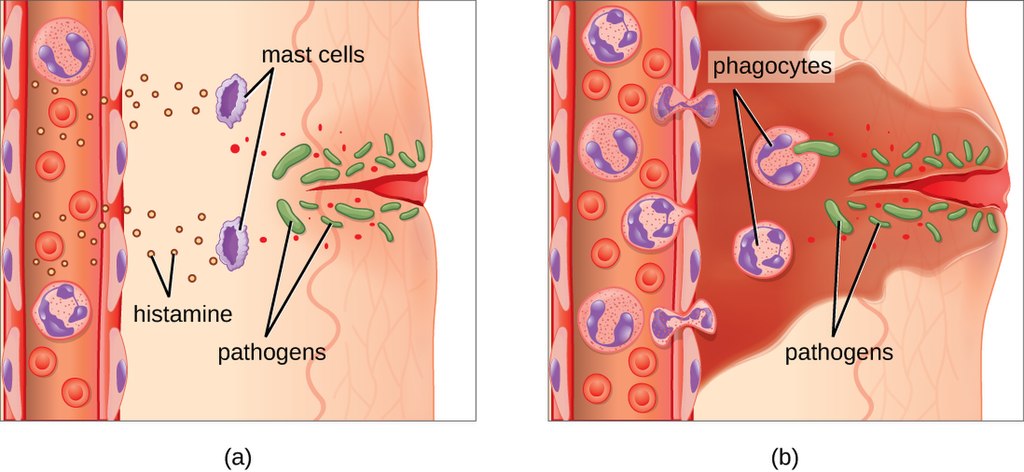

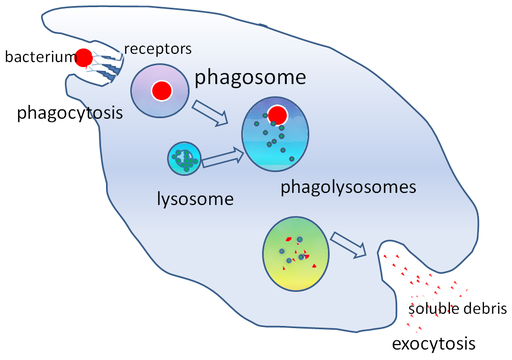

Innate Immune System

The innate immune system (sometimes referred to as "non-specific defense") provides very quick, but non-specific responses to pathogens. It responds the same way regardless of the type of pathogen that is attacking the host. It includes barriers — such as the skin and mucous membranes — that normally keep pathogens out of the body. It also includes general responses to pathogens that manage to breach these barriers, including chemicals and cells that attack the pathogens inside the human host. Certain leukocytes (white blood cells), for example, engulf and destroy pathogens they encounter in the process called phagocytosis, which is illustrated in Figure 17.2.2. Exposure to pathogens leads to an immediate maximal response from the innate immune system.

Watch the video below, "Neutrophil Phagocytosis - White Blood Cells Eats Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteria" by ImmiflexImmuneSystem, to see phagocytosis in action.

https://youtu.be/Z_mXDvZQ6dU

Neutrophil Phagocytosis - White Blood Cell Eats Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteria, ImmiflexImmuneSystem, 2013.

Adaptive Immune System

The adaptive immune system is activated if pathogens successfully enter the body and manage to evade the general defenses of the innate immune system. An adaptive response is specific to the particular type of pathogen that has invaded the body, or to cancerous cells. It takes longer to launch a specific attack, but once it is underway, its specificity makes it very effective. An adaptive response also usually leads to immunity. This is a state of resistance to a specific pathogen, due to the adaptive immune system's ability to “remember” the pathogen and immediately mount a strong attack tailored to that particular pathogen if it invades again in the future.

Self vs. Non-Self

Both innate and adaptive immune responses depend on the immune system's ability to distinguish between self- and non-self molecules. Self molecules are those components of an organism’s body that can be distinguished from foreign substances by the immune system. Virtually all body cells have surface proteins that are part of a complex called major histocompatibility complex (MHC). These proteins are one way the immune system recognizes body cells as self. Non-self proteins, in contrast, are recognized as foreign, because they are different from self proteins.

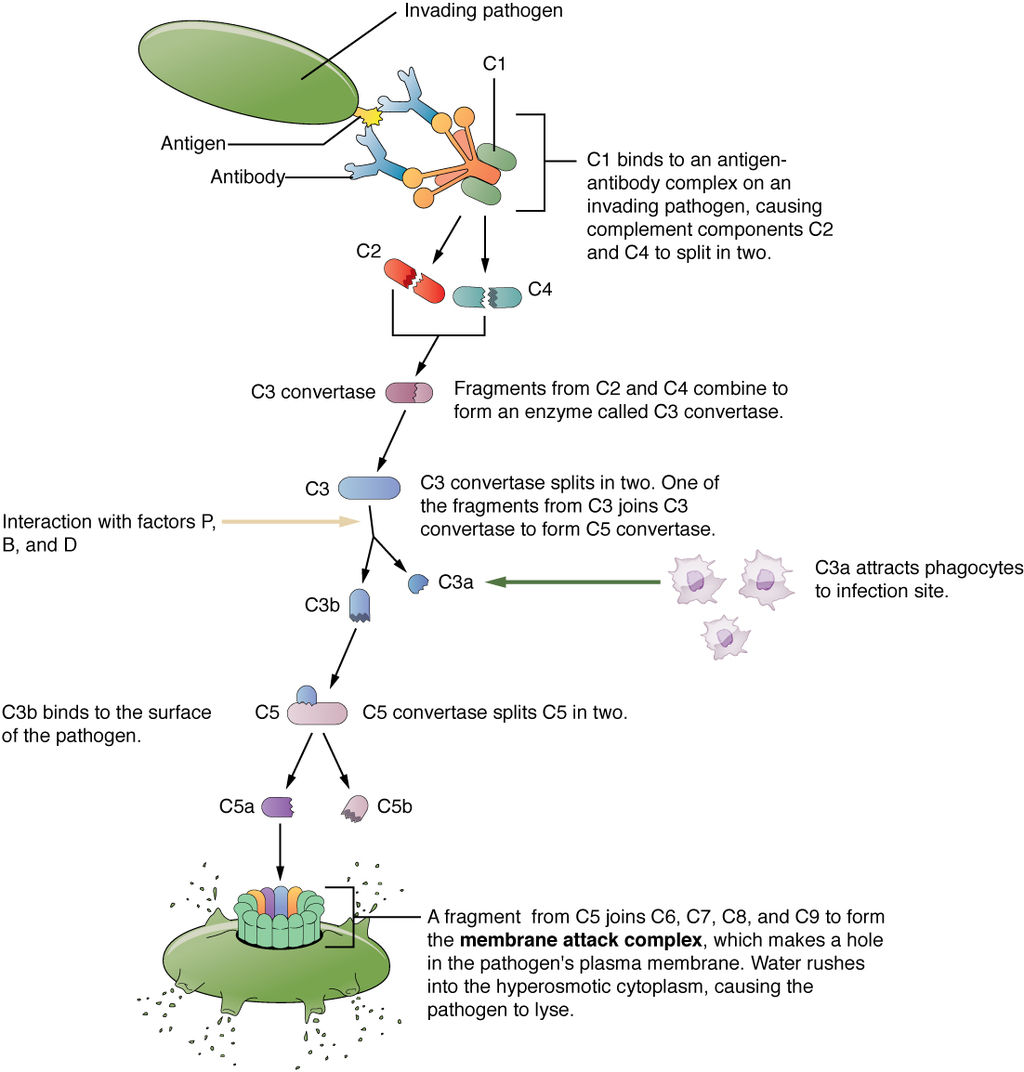

Antigens and Antibodies

Many non-self molecules comprise a class of compounds called antigens. Antigens, which are usually proteins, bind to specific receptors on immune system cells and elicit an adaptive immune response. Some adaptive immune system cells (B cells) respond to foreign antigens by producing antibodies. An antibody is a molecule that precisely matches and binds to a specific antigen. This may target the antigen (and the pathogen displaying it) for destruction by other immune cells.

Antigens on the surface of pathogens are how the adaptive immune system recognizes specific pathogens. Antigen specificity allows for the generation of responses tailored to the specific pathogen. It is also how the adaptive immune system ”remembers” the same pathogen in the future.

Immune Surveillance

Another important role of the immune system is to identify and eliminate tumor cells. This is called immune surveillance. The transformed cells of tumors express antigens that are not found on normal body cells. The main response of the immune system to tumor cells is to destroy them. This is carried out primarily by aptly-named killer T cells of the adaptive immune system.

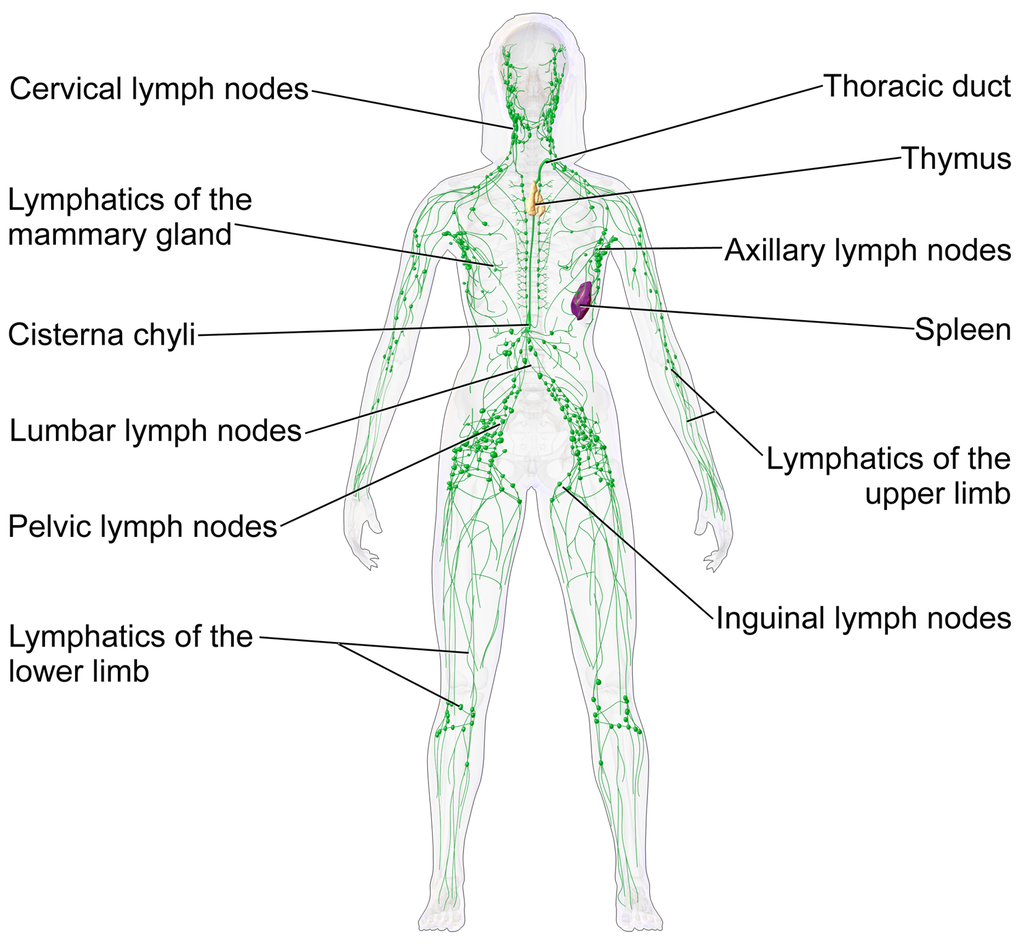

Lymphatic System

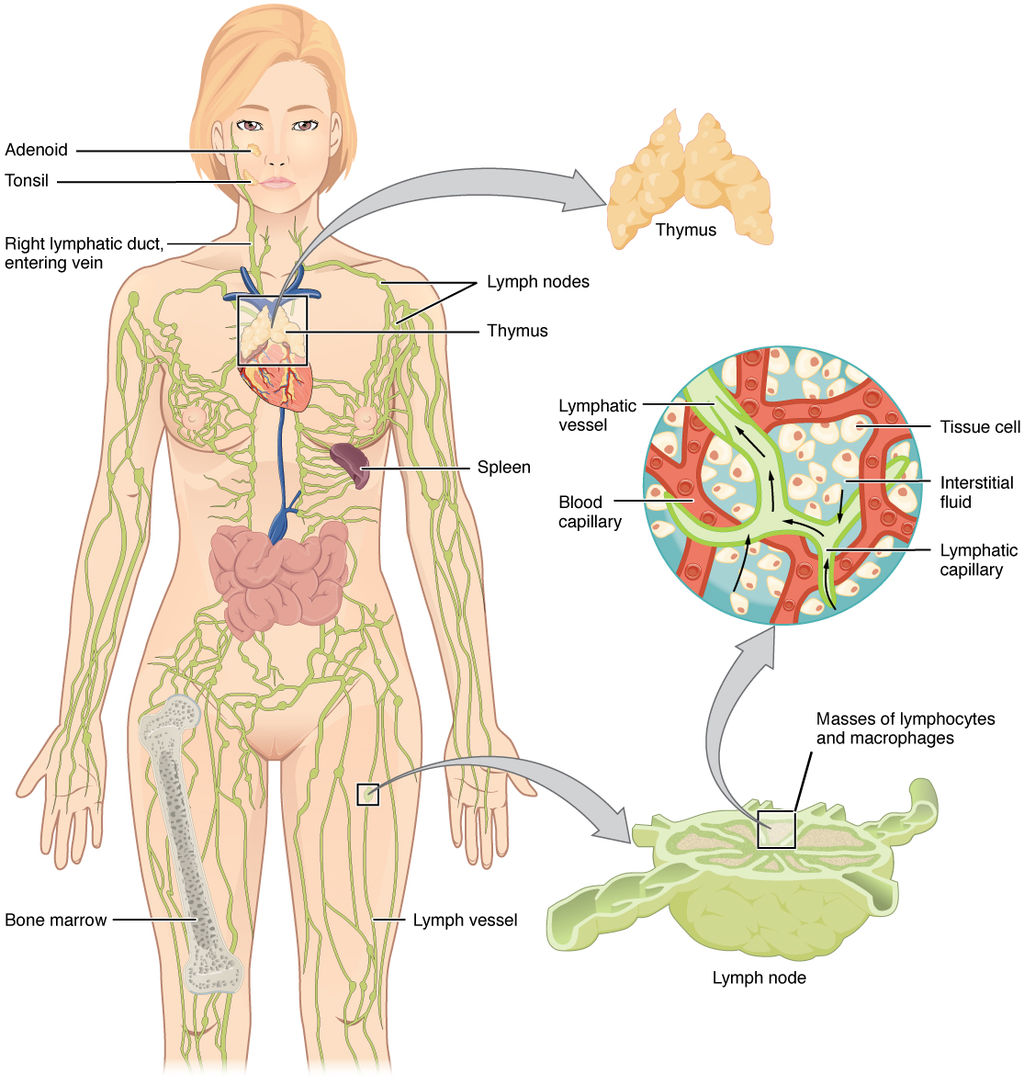

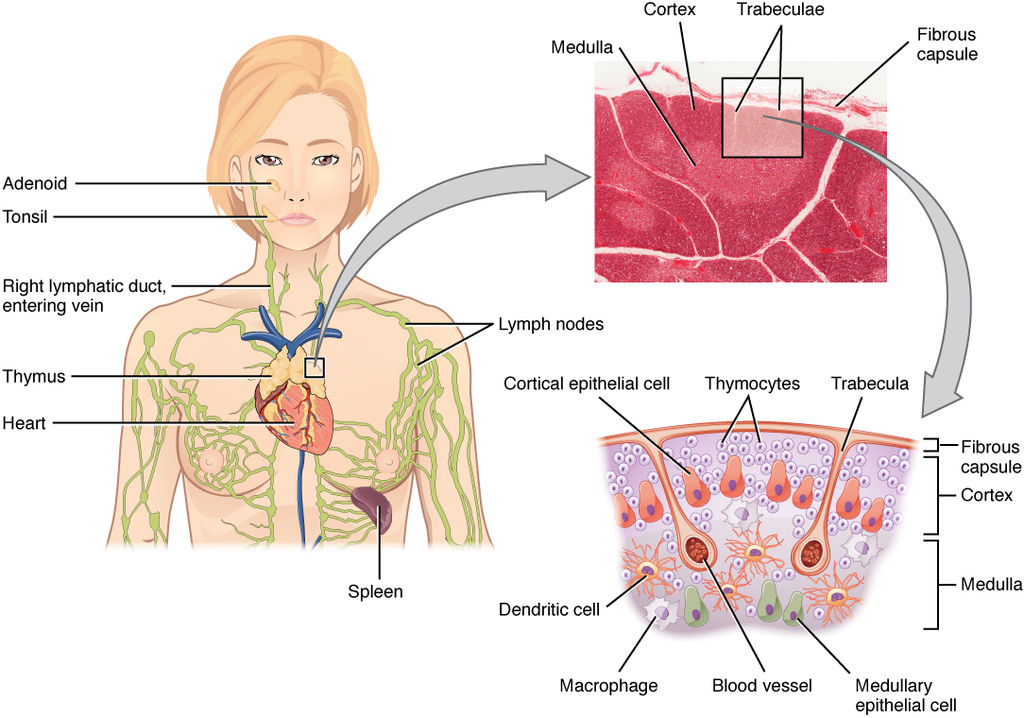

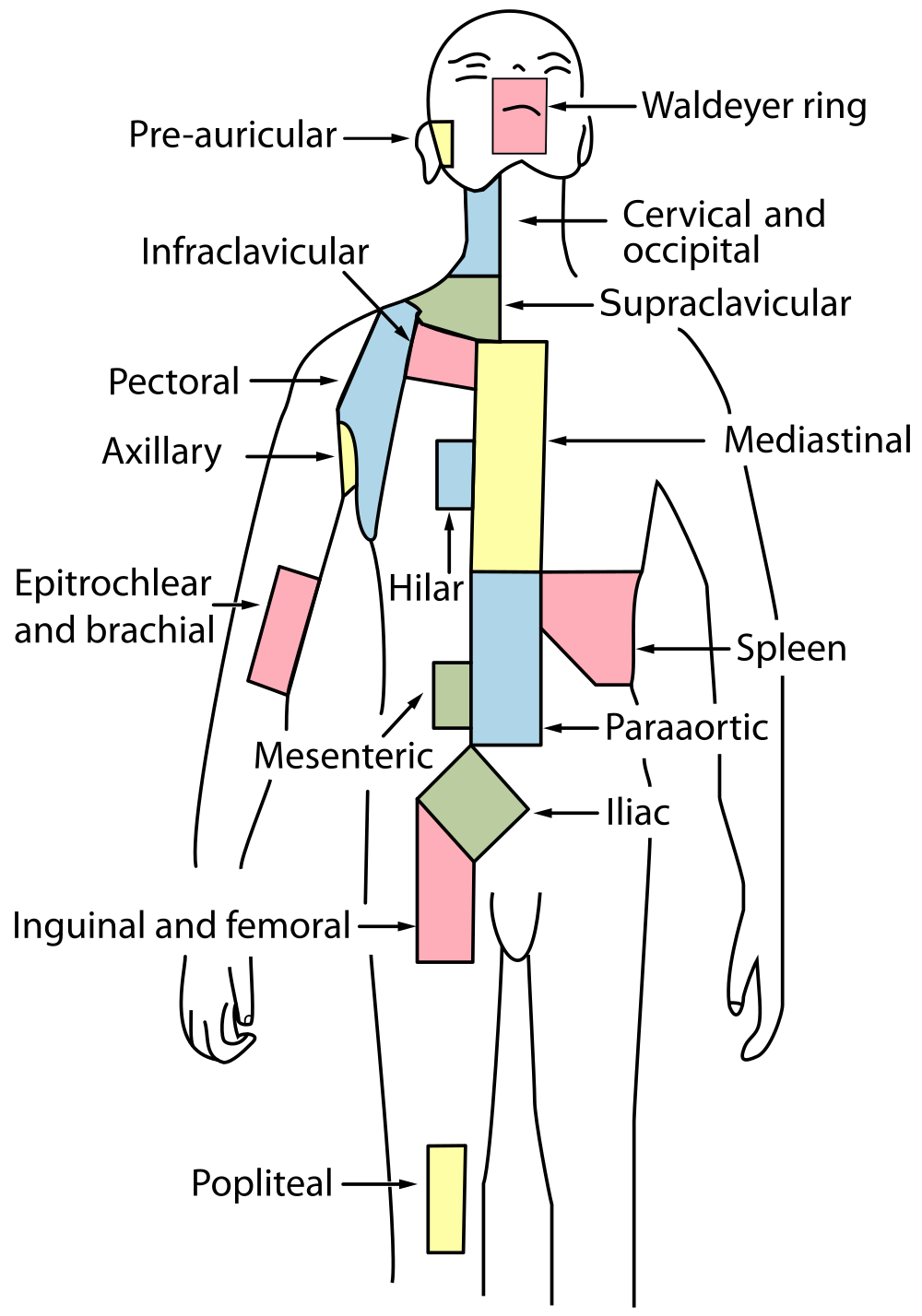

The lymphatic system is a human organ system that is a vital part of the adaptive immune system. It is also part of the cardiovascular system and plays a major role in the digestive system (see section 17.3 Lymphatic System). The major structures of the lymphatic system are shown in Figure 17.2.3 .

The lymphatic system consists of several lymphatic organs and a body-wide network of lymphatic vessels that transport the fluid called lymph. Lymph is essentially blood plasma that has leaked from capillaries into tissue spaces. It includes many leukocytes, especially lymphocytes, which are the major cells of the lymphatic system. Like other leukocytes, lymphocytes defend the body. There are several different types of lymphocytes that fight pathogens or cancer cells as part of the adaptive immune system.

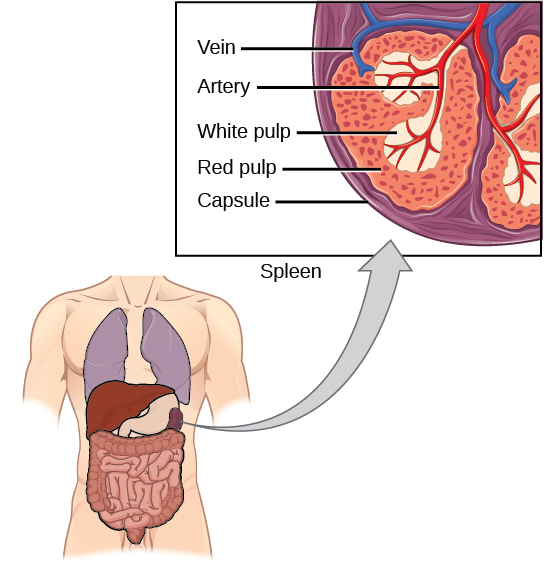

Major lymphatic organs include the thymus and bone marrow. Their function is to form and/or mature lymphocytes. Other lymphatic organs include the spleen, tonsils, and lymph nodes, which are small clumps of lymphoid tissue clustered along lymphatic vessels. These other lymphatic organs harbor mature lymphocytes and filter lymph. They are sites where pathogens collect, and adaptive immune responses generally begin.

Neuroimmune System vs. Peripheral Immune System

The brain and spinal cord are normally protected from pathogens in the blood by the selectively permeable blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers. These barriers are part of the neuroimmune system. The neuroimmune system has traditionally been considered distinct from the rest of the immune system, which is called the peripheral immune system — although that view may be changing. Unlike the peripheral system, in which leukocytes are the main cells, the main cells of the neuroimmune system are thought to be nervous system cells called neuroglia. These cells can recognize and respond to pathogens, debris, and other potential dangers. Types of neuroglia involved in neuroimmune responses include microglial cells and astrocytes.

- Microglial cells are among the most prominent types of neuroglia in the brain. One of their main functions is to phagocytize cellular debris that remains when neurons die. Microglial cells also “prune” obsolete synapses between neurons.

- Astrocytes are neuroglia that have a different immune function. They allow certain immune cells from the peripheral immune system to cross into the brain via the blood-brain barrier to target both pathogens and damaged nervous tissue.

Feature: Human Biology in the News

“They’ll have to rewrite the textbooks!”

That sort of response to a scientific discovery is sure to attract media attention, and it did. It’s what Kevin Lee, a neuroscientist at the University of Virginia, said in 2016 when his colleagues told him they had discovered human anatomical structures that had never before been detected. The structures were tiny lymphatic vessels in the meningeal layers surrounding the brain.

How these lymphatic vessels could have gone unnoticed when all human body systems have been studied so completely is amazing in its own right. The suggested implications of the discovery are equally amazing:

- The presence of these lymphatic vessels means that the brain is directly connected to the peripheral immune system, presumably allowing a close association between the human brain and human pathogens. This suggests an entirely new avenue by which humans and their pathogens may have influenced each other’s evolution. The researchers speculate that our pathogens even may have influenced the evolution of our social behaviors.

- The researchers think there will also be many medical applications of their discovery. For example, the newly discovered lymphatic vessels may play a major role in neurological diseases that have an immune component, such as multiple sclerosis. The discovery might also affect how conditions such as autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia are treated.

17.2 Summary

- Any agent that can cause disease is called a pathogen. Most human pathogens are microorganisms, such as bacteria and viruses. The immune system is the body system that defends the human host from pathogens and cancerous cells.

- The innate immune system is a subset of the immune system that provides very quick, but non-specific responses to pathogens. It includes multiple types of barriers to pathogens, leukocytes that phagocytize pathogens, and several other general responses.

- The adaptive immune system is a subset of the immune system that provides specific responses tailored to particular pathogens. It takes longer to put into effect, but it may lead to immunity to the pathogens.

- Both innate and adaptive immune responses depend on the immune system's ability to distinguish between self and non-self molecules. Most body cells have major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins that identify them as self. Pathogens and tumor cells have non-self antigens that the immune system recognizes as foreign.

- Antigens are proteins that bind to specific receptors on immune system cells and elicit an adaptive immune response. Generally, they are non-self molecules on pathogens or infected cells. Some immune cells (B cells) respond to foreign antigens by producing antibodies that bind with antigens and target pathogens for destruction.

- Tumor surveillance is an important role of the immune system. Killer T cells of the adaptive immune system find and destroy tumor cells, which they can identify from their abnormal antigens.

- The lymphatic system is a human organ system vital to the adaptive immune system. It consists of several organs and a system of vessels that transport lymph. The main immune function of the lymphatic system is to produce, mature, and circulate lymphocytes, which are the main cells in the adaptive immune system.

- The neuroimmune system that protects the central nervous system is thought to be distinct from the peripheral immune system that protects the rest of the human body. The blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers are one type of protection for the neuroimmune system. Neuroglia also play role in this system, for example, by carrying out phagocytosis.

17.2 Review Questions

-

- What is a pathogen?

- State the purpose of the immune system.

- Compare and contrast the innate and adaptive immune systems.

- Explain how the immune system distinguishes self molecules from non-self molecules.

- What are antigens?

- Define tumor surveillance.

- Briefly describe the lymphatic system and its role in immune function.

- Identify the neuroimmune system.

- What does it mean that the immune system is not just composed of organs?

- Why is the immune system considered “layered?”

17.2 Explore More

https://youtu.be/xZbcwi7SfZE

The Antibiotic Apocalypse Explained, Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell, 2016.

https://youtu.be/Nw27_jMWw10

Overview of the Immune System, Handwritten Tutorials, 2011.

https://youtu.be/gVdY9KXF_Sg

The surprising reason you feel awful when you're sick - Marco A. Sotomayor, TED-Ed, 2016.

Attributions

Figure 17.1.1

Schistosome Parasite by Bruce Wetzel and Harry Schaefer (Photographers) from the National Cancer Institute, Visuals online is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

Figure 17.1.2

Phagocytosis by Rlawson at en.wikibooks on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en) license. (Transferred from en.wikibooks to Commons by User:Adrignola.)

Figure 17.1.3

2201_Anatomy_of_the_Lymphatic_System by OpenStax College on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Table 17.1.1

- EscherichiaColi NIAID [photo] by Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

- Herpes simplex virus TEM B82-0474 lores by Dr. Erskine Palmer/ CDC Public Health Image Library (PHIL) on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

- Red death cap mushroom by Rosendahl on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain). (Transferred from Pixnio by Fæ.)

- Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of Giardia lamblia by Janice Haney Carr/ CDC, Public Health Image Library (PHIL) Photo ID# 8698 is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain).

References

Barney, J. (2016, March 21). They’ll have to rewrite the textbooks [online article]. Illimitable - Discovery. UVA Today/ University of Virginia. https://news.virginia.edu/illimitable/discovery/theyll-have-rewrite-textbooks

Betts, J. G., Young, K.A., Wise, J.A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D.H., Korol, O., Johnson, J.E., Womble, M., DeSaix, P. (2013, June 19). Figure 21.2 Anatomy of the lymphatic system [digital image]. In Anatomy and Physiology (Section 21.1). OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems

Handwritten Tutorials. (2011, October 25). Overview of the immune system. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nw27_jMWw10&feature=youtu.be

ImmiflexImmuneSystem. (2013). Neutrophil phagocytosis - White blood cell eats staphylococcus aureus bacteria. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z_mXDvZQ6dU

Kurzgesagt – In a Nutshell. (2016, March 16). The antibiotic apocalypse explained. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xZbcwi7SfZE&feature=youtu.be

Louveau, A., Smirnov, I., Keyes, T. J., Eccles, J. D., Rouhani, S. J., Peske, J. D., Derecki, N. C., Castle, D., Mandell, J. W., Lee, K. S., Harris, T. H., & Kipnis, J. (2015). Structural and functional features of central nervous system lymphatic vessels. Nature, 523(7560), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14432

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Autism spectrum disorder [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/autism-spectrum-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20352928

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Multiple sclerosis [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/multiple-sclerosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350269

Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Schizophrenia [online article]. MayoClinic.org. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/schizophrenia/symptoms-causes/syc-20354443

TED-Ed. (2016, April 19). The surprising reason you feel awful when you're sick - Marco A. Sotomayor. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gVdY9KXF_Sg&feature=youtu.be

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Family Planning Pioneer

Her name was Marie Stopes, and she was a British author and paleobotanist who lived from 1880 to 1958. She is pictured in Figure 18.11.1 in her lab next to her microscope. Stopes made significant contributions to science and was the first woman on the faculty of the University of Manchester in England. Her primary claim to fame was her work as a family planning pioneer.

Along with her husband, Stopes founded the first birth control clinic in Britain. She also edited a newsletter called Birth Control News, which gave explicit practical advice on how to avoid unwanted pregnancies. In 1918, she published a sex manual titled Married Love. The book was controversial and influential, bringing the subject of contraception into wide public discourse for the first time.

What Is Contraception?

About a century after Married Love, more than half of all fertile married couples worldwide use some form of contraception. Contraception, also known as birth control, is any method or device used to prevent pregnancy. Birth control methods have been used for centuries, but safe and effective methods only became available in the 20th century, in part because of the work of people like Marie Stopes.

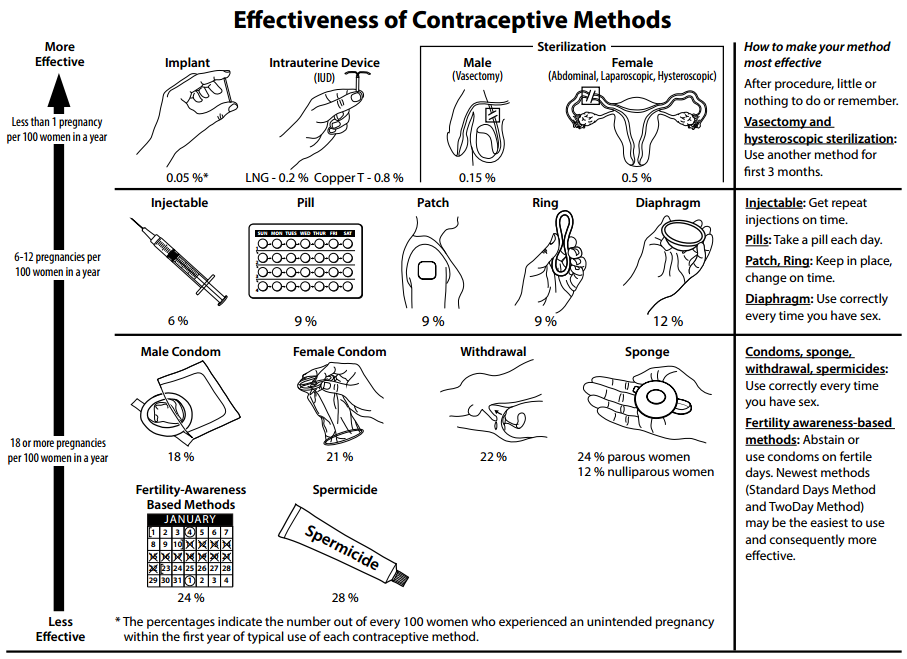

Many different birth control methods are currently available, but they differ considerably in their effectiveness at preventing pregnancy. The effectiveness of contraception is generally expressed as the failure rate, which is the percentage of women who become pregnant using a given method during the first year of use. Virtually no one uses any method of birth control perfectly, so the failure rate with typical use is almost always higher — and often much higher — than the failure rate with perfect use. For example, with perfect use, a birth control method might have a failure rate of just 1%, whereas with typical use, the failure rate might be 25%. For comparison, there is an average one-year pregnancy rate of 85% if no contraception is used.

All methods of birth control have potential adverse effects, but their health risks are less than the health risks associated with pregnancy. Using contraception to space the children in a family is also good for the children’s health and development, as well as for the health of the mother.

Types of Contraception and Their Effectiveness

Types of birth control methods include barrier methods, hormonal methods, intrauterine devices, behavioural methods, and sterilization. With the exception of sterilization, all of these methods are reversible. Examples of each type of birth control method and their failure rates with typical use are described below. Much of the information is also summarized in Figure 18.11.2.

Barrier Methods

Barrier methods are devices that are used to physically block sperm from entering the uterus. They include condoms and diaphragms.

Condoms

Condoms are the most commonly used method of birth control globally. There are condoms for females and males, but male condoms are more widely used, less expensive, and more readily available. Both types of condoms are pictured in Figures 18.11.3 and 18.11.4. A male condom is placed on a man’s erect penis, and a female condom is placed inside a woman’s vagina. Whichever type of condom is used, it must be put in place before sexual intercourse occurs. Condoms work by physically blocking ejaculated sperm from entering the vagina of the sexual partner. With typical use, male condoms have an 18% failure rate, and female condoms have a 21% failure rate. Unlike virtually all other birth control methods, condoms also help prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), in addition to helping to prevent pregnancy.

Diaphragms

Diaphragms, like the one pictured in Figure 18.11.5, ideally prevent sperm from passing through the cervical canal and into the uterus. A diaphragm is inserted vaginally before sexual intercourse occurs and must be placed over the cervix to be effective. It is usually recommended that a diaphragm be covered with spermicide before insertion for extra protection. It is also recommended that the diaphragm be left in place for at least six hours after intercourse. The failure rate of diaphragms with typical use is about 12%, which is about half that of condoms. However, diaphragms do not help prevent the spread of STIs, and their use is also associated with an increased frequency of urinary tract infections in females.

Hormonal Methods

Hormonal contraception is the administration of hormones to prevent ovulation. Hormones can be taken orally in birth control pills, implanted under the skin, injected into a muscle, or received transdermally from a skin patch. Hormonal methods are currently available only for women, although hormonal contraceptives for men are being tested in clinical trials.

Birth control pills are the most common form of hormonal contraception. There are two types of pills: the combined pill (which contains both estrogen and progesterone) and the progesterone-only pill. Both types of pills inhibit ovulation and thicken cervical mucus. The failure rate of birth control pills is only about 1% or less, if used perfectly. However, the failure rate rises to about 10% with typical use, because women do not always remember to take the pill at the same time every day. The combined pill is associated with a slightly increased risk of blood clots, but a reduced risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers. The progesterone-only pill does not increase the risk of blood clots, but it may cause irregular menstrual periods. It may take a few weeks or even months for fertility to return to normal after long-term use of birth control pills.

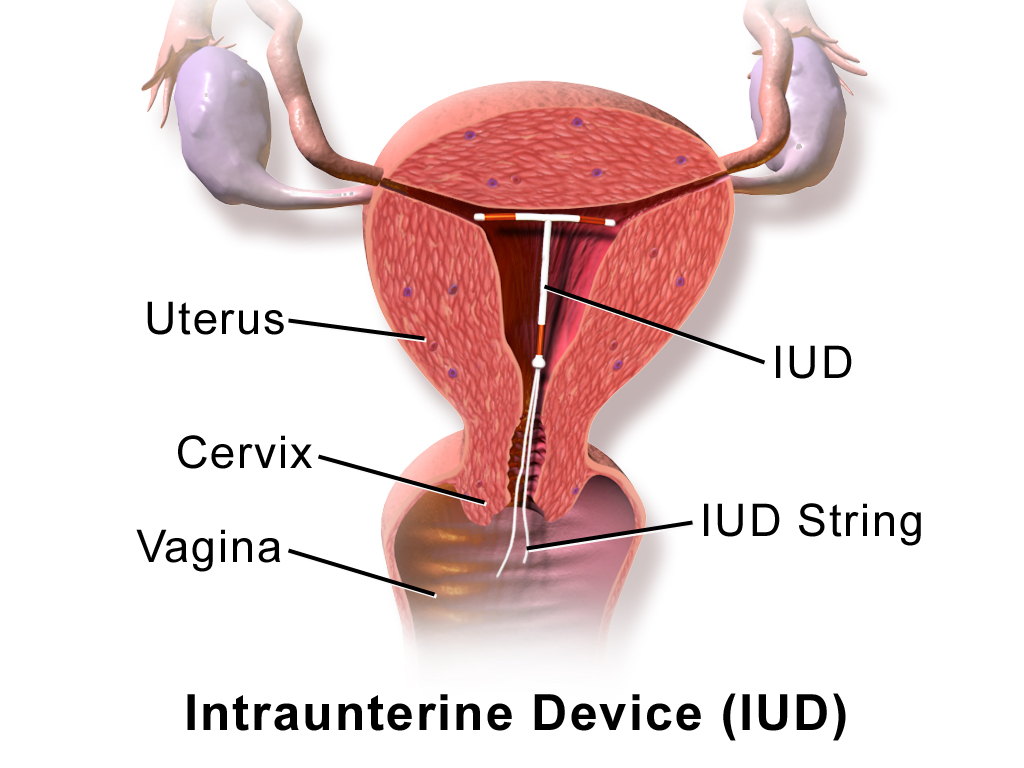

Intrauterine Devices

An intrauterine device (IUD) is a T-shaped or coiled plastic structure that is inserted into the uterus via the vagina and cervix that contains either copper or a hormone. You can see an IUD in the uterus in the drawing of the female reproductive system in Figure 18.11.6. An IUD is inserted by a physician and may be left in place for months or even years. A physician also must remove an IUD, using the strings attached to the device. The copper in copper IUDs prevents pregnancy by interfering with the movement of sperm so they cannot reach and fertilize an egg. The copper may also prevent implantation in the unlikely circumstance of a sperm managing to reach and fertilize an ovum, in which case the blastocyst/zygote would be shed during menstruation. The hormones in hormonal IUDs prevent pregnancy by thickening cervical mucus and trapping sperm. The hormones may also interfere with ovulation, so there is no egg to fertilize.

For both types of IUDs, the failure rates are <1%, and failure rates with typical use are virtually the same as failure rates with perfect use. Their effectiveness is one reason that IUDs are among the most widely used forms of reversible contraception. Once removed, even after long-term use, fertility returns to normal immediately. On the other hand, IUDs do have a risk of complications, including increased menstrual bleeding and more painful menstrual cramps. IUDs are also occasionally expelled from the uterus, and there is a slight risk of perforation of the uterus by the IUD.

Behavioural Methods

The least effective methods of contraception are behavioural methods. They involve regulating the timing or method of intercourse to prevent introduction of sperm into the female reproductive tract, either altogether or when an egg may be present. Behavioural methods include fertility awareness methods and withdrawal. Abstinence from sexual activity, or at least from vaginal intercourse, is sometimes considered a behavioural method, as well — but it is unlikely to be practiced consistently enough by most people to prevent pregnancy. Even teens who receive abstinence-only sex education do not have reduced rates of pregnancy. Abstinence is also ineffective in cases of non-consensual sex.

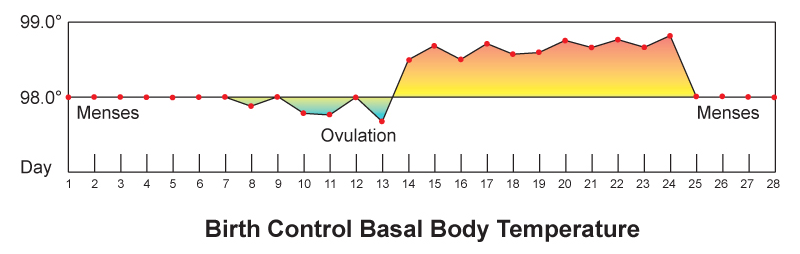

Fertility Awareness Methods

Fertility awareness methods involve estimating the most fertile days of the menstrual cycle and then avoiding unprotected vaginal intercourse on those days. The most fertile days are generally a few days before ovulation occurs, the day of ovulation, and another day or two after that. Unless unprotected sex occurs on those days, pregnancy is unlikely. Techniques for estimating the most fertile days include monitoring and detecting minor changes in basal body temperature or cervical secretions. This requires daily motivation and diligence, so it is not surprising that typical-use failure rates of these methods are at least 20–25%, and for some individuals may be as high as using no contraception at all (85%).

Basal body temperature is the lowest body temperature when the body is at rest (usually during sleep). It is most often estimated by a temperature measurement taken immediately upon awakening in the morning and before any physical activity has occurred. Basal body temperature normally rises after ovulation occurs, as shown in the graph below (Figure 18.11.7). The increase in temperature is small but consistent and may be used to determine when ovulation occurs, around which time unprotected intercourse should be avoided to prevent pregnancy. However, basal body temperature only shows when ovulation has already occurred, and it cannot predict in advance when ovulation will occur. Sperm can live for up to a week in the female reproductive tract, so determining the occurrence of ovulation only after ovulation has already happened is a major drawback of this method.

Monitoring cervical mucus has the potential for being more effective than monitoring basal body temperature, because it can predict ovulation ahead of time. As ovulation approaches, cervical secretions usually increase in amount and become thinner (which helps sperm swim through the cervical canal). By recognizing the changing characteristics of cervical mucus, a woman may be able to predict when she will ovulate. From this information, she can determine when she should avoid unprotected sex to prevent pregnancy.

Withdrawal

Withdrawal (also called coitus interruptus) is the practice of withdrawing the penis from the vagina before ejaculation ensues. The main risk of the withdrawal method is that the man may not perform the maneuver correctly or in a timely manner. Fluid typically released from the penis before ejaculation occurs may also contain some sperm. In addition, if sperm are ejaculated just outside of the vagina, there is a chance they will be able to enter the vagina and travel through the female reproductive tract to fertilize an egg. For all these reasons, the withdrawal method has a relatively high failure rate of about 22% with typical use.

Sterilization

The most effective contraceptive method is sterilization. In both sexes, sterilization generally involves surgical procedures that are considered irreversible. Additional surgery may be able to reverse a sterilization procedure, but there are no guarantees. Male sterilization is generally less invasive and less risky than female sterilization.

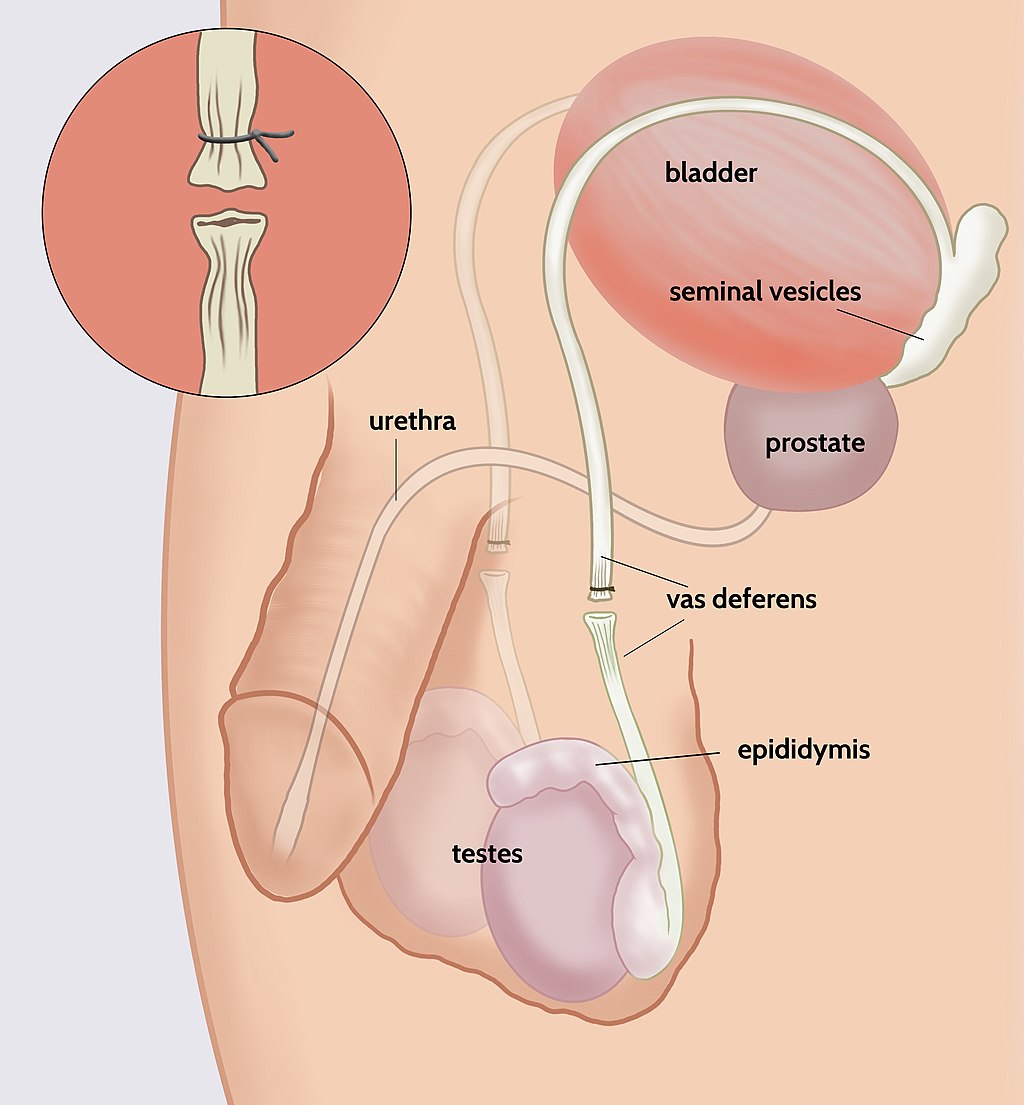

Male Sterilization

Male sterilization is usually achieved with a vasectomy. In this surgery, the vas deferens from each testis is clamped, cut, or otherwise sealed (see Figure 18.11.8). This prevents sperm from traveling from the epididymis to the ejaculatory ducts and being ejaculated from the penis. The same amount of semen will still be ejaculated, but it will not contain any sperm, making fertilization impossible. After a vasectomy, the testes continue to produce sperm, but the sperm are reabsorbed. It usually takes several months after a vasectomy for all remaining sperm to be ejaculated or reabsorbed. In the meantime, another method of birth control should be used.

Female Sterilization

The procedure undertaken for female sterilization is usually tubal ligation. The oviducts may be tied or cut in a surgical procedure, which permanently blocks the tubes. Alternatively, tiny metal implants may be inserted into the oviducts in a nonsurgical procedure. Over time, scar tissue grows around the implants and permanently blocks the tubes. Either method stops eggs from traveling from the ovaries through the oviducts, where fertilization usually takes place.

Emergency Contraception

Emergency contraception is any form of contraception that is used after unprotected vaginal intercourse. One method is the so-called “morning-after” pill. This is essentially a high-dose birth control pill that helps prevent pregnancy by temporarily preventing ovulation. It works only if ovulation has not already occurred, and when taken within five days after unprotected sex. The sooner the pill is taken, the more likely it is to work. Another method of emergency contraception is the IUD. An IUD that is inserted up to five days after unprotected sex can prevent nearly 100% of pregnancies. It keeps sperm from reaching and fertilizing an egg, or inhibits implantation if an ovum has already been fertilized. The IUD can then be left in place to prevent future pregnancies.

18.11 Summary

- More than half of all fertile couples worldwide use contraception (birth control), which is any method or device used to prevent pregnancy. Different methods of contraception vary in their effectiveness, typically expressed as the failure rate, or the percentage of women who become pregnant using a given method during the first year of use. For most methods, the failure rate with typical use is much higher than the failure rate with perfect use.

- Types of birth control methods include barrier methods, hormonal methods, intrauterine devices, behavioural methods, and sterilization. Except for sterilization, all of the methods are reversible. All of the methods have health risks, but they are less than the risks of pregnancy.

- Barrier methods are devices that block sperm from entering the uterus. They include condoms and diaphragms. Of all birth control methods, only condoms can prevent the spread of sexually transmitted infections in addition to pregnancy.

- Hormonal methods involve the administration of hormones to prevent ovulation. Hormones can be administered in various ways, such as in an injection, through a skin patch, or — most commonly — in birth control pills. There are two types of birth control pills: those that contain estrogen and progesterone, and those that contain only progesterone. Both types are equally effective, but they have different potential side effects.

- An intrauterine device (IUD) is a small T-shaped plastic structure containing copper or a hormone that is inserted into the uterus by a physician and left in place for months or even years. It is highly effective even with typical use, but it does have some risks, such as increased menstrual bleeding and, rarely, perforation of the uterus.

- Behavioural methods involve regulating the timing or method of intercourse to prevent introduction of sperm into the female reproductive tract, either altogether or when an egg may be present. In fertility awareness methods, unprotected intercourse is avoided during the most fertile days of the cycle, as estimated by basal body temperature or the characteristics of cervical mucus. In withdrawal (coitus interruptus), the penis is withdrawn from the vagina before ejaculation occurs. Behavioural methods are the least effective methods of contraception.

- Sterilization is the most effective contraceptive method, but it requires a surgical procedure and may be irreversible. Male sterility is usually achieved with a vasectomy, in which the vas deferens are clamped or cut to prevent sperm from being ejaculated in semen. Female sterility is usually achieved with a tubal ligation, in which the oviducts are clamped or cut to prevent sperm from reaching and fertilizing eggs.

- Emergency contraception is any form of contraception used after unprotected vaginal intercourse. One method is the “morning after” pill, which is a high-dose birth control pill that can be taken up to five days after unprotected sex. Another method is an IUD, which can be inserted up to five days after unprotected sex.

18.11 Review Questions

-

- How is the effectiveness of contraceptive methods typically measured?

- What is an IUD?

- Discuss sterilization as a birth control method. Compare sterilization in males and females.

- What is emergency contraception? When is it used? What are two forms of emergency contraception?

- How does the thickness of cervical mucus relate to fertility? How do two methods of contraception take advantage of this relationship?

- If a newly developed method of contraception had a 35% failure rate, would you consider this to be an effective method? Explain your answer.

18.11 Explore More

https://youtu.be/Zx8zbTMTncs

How do contraceptives work? - NWHunter, TED-Ed, 2016.

https://youtu.be/jdr1yDO7MoY

The History Of Birth Control | TIME, 2015.

https://youtu.be/vIaL5QiKbWI

Finally, A Male Pill? SciShow, 2012.

Attributions

Figure 18.11.1

512px-Marie_Stopes [cropped] by AdamBMorgan on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain). (Original by Unknown author: File:Marie Stopes in her laboratory, 1904.jpg).

Figure 18.11.2

Effectivenessofcontraceptives by Center for Disease Control and Prevention on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 18.11.3

Condom by Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition on Unsplash is used under the Unsplash License (https://unsplash.com/license).

Figure 18.11.4

Female condom by Ceridwen on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 FR (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/fr/deed.en) license.

Figure 18.11.5

Contraceptive_diaphragm by Axefan2 on Wikimedia Commons is in the public domain (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/public_domain).

Figure 18.11.6

1024px-Blausen_0585_IUD by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) license.

Figure 18.11.7

Basal_Body_Temperature by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

Figure 18.11.8

1024px-Open_Vasectomy_ by Timdwilliamson on Wikimedia Commons is used under a CC BY SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) license.

References

Blausen.com Staff. (2014). Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436

SciShow. (2012, August 16). Finally, a male pill? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vIaL5QiKbWI&feature=youtu.be

Stopes, M. (1918). Married love. Wikisource. https://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=Married_Love&oldid=6230157 (Originally published with Preface and Notes by William J. Robinson, by The Critic and Guide Company. This book was banned in the United States until 1933.)

TED-Ed. (2016, September). How do contraceptives work? - NWHunter. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zx8zbTMTncs&feature=youtu.be

Time. (2015, January 30). The history of birth control | TIME. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdr1yDO7MoY&feature=youtu.be

Wikipedia contributors. (2020, August 9). Marie Stopes. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Marie_Stopes&oldid=972063381

Created by CK-12 Foundation/Adapted by Christine Miller

Tonsillitis

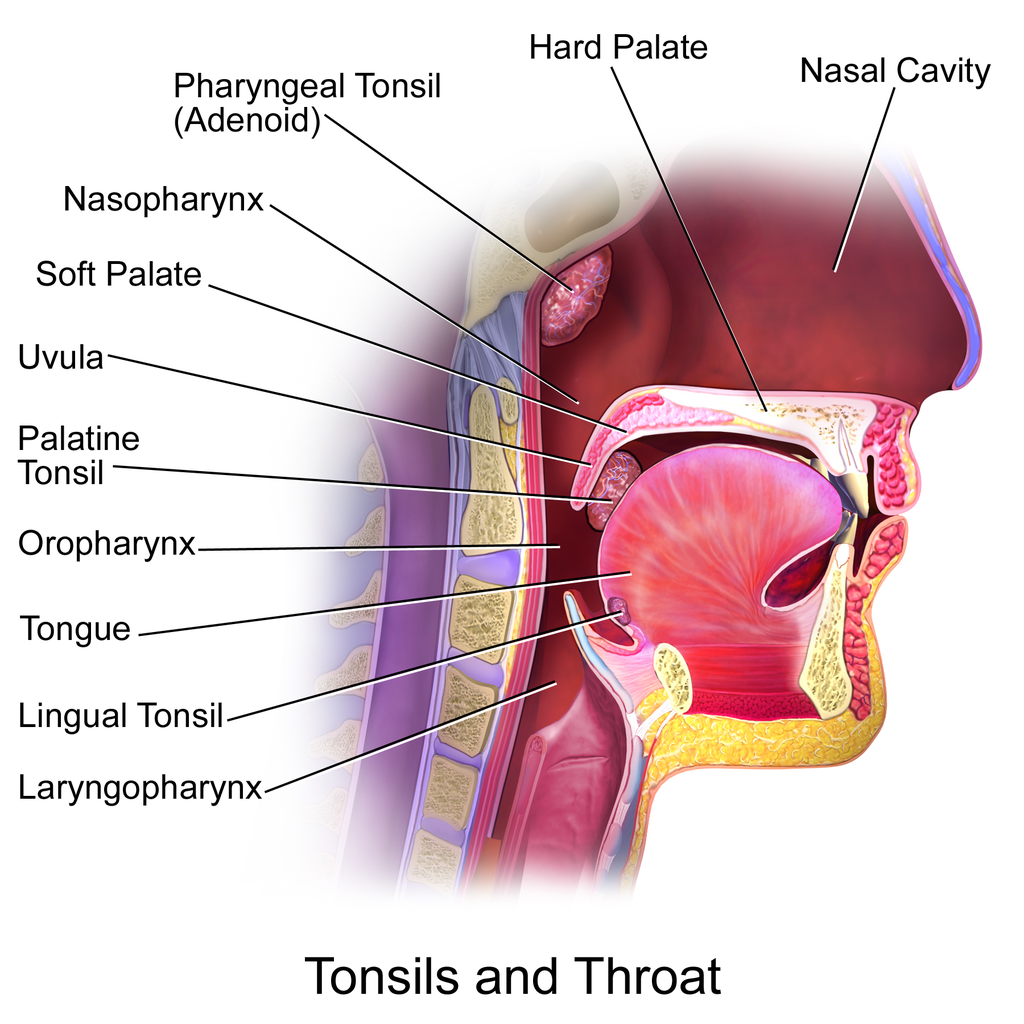

The white patches on either side of the throat in Figure 17.3.1 are signs of tonsillitis. The tonsils are small structures in the throat that are very common sites of infection. The white spots on the tonsils pictured here are evidence of infection. The patches consist of large amounts of dead bacteria, cellular debris, and white blood cells — in a word: pus. Children with recurrent tonsillitis may have their tonsils removed surgically to eliminate this type of infection. The tonsils are organs of the lymphatic system.

What Is the Lymphatic System?

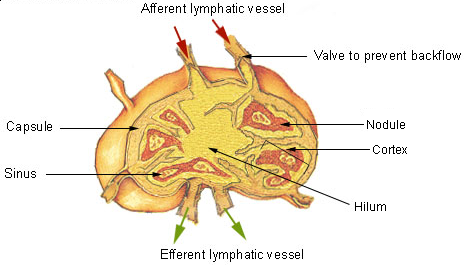

The lymphatic system is a collection of organs involved in the production, maturation, and harboring of white blood cells called lymphocytes. It also includes a network of vessels that transport or filter the fluid known as lymph in which lymphocytes circulate. Figure 17.3.2 shows major lymphatic vessels and other structures that make up the lymphatic system. Besides the tonsils, organs of the lymphatic system include the thymus, the spleen, and hundreds of lymph nodes distributed along the lymphatic vessels.

The lymphatic vessels form a transportation network similar in many respects to the blood vessels of the cardiovascular system. However, unlike the cardiovascular system, the lymphatic system is not a closed system. Instead, lymphatic vessels carry lymph in a single direction — always toward the upper chest, where the lymph empties from lymphatic vessels into blood vessels.

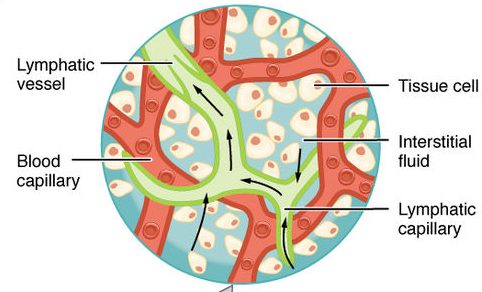

Cardiovascular Function of the Lymphatic System

The return of lymph to the bloodstream is one of the major functions of the lymphatic system. When blood travels through capillaries of the cardiovascular system, it is under pressure, which forces some of the components of blood (such as water, oxygen, and nutrients) through the walls of the capillaries and into the tissue spaces between cells, forming tissue fluid, also called interstitial fluid (see Figure 17.3.3). Interstitial fluid bathes and nourishes cells, and also absorbs their waste products. Much of the water from interstitial fluid is reabsorbed into the capillary blood by osmosis. Most of the remaining fluid is absorbed by tiny lymphatic vessels called lymph capillaries. Once interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic vessels, it is called lymph. Lymph is very similar in composition to blood plasma. Besides water, lymph may contain proteins, waste products, cellular debris, and pathogens. It also contains numerous white blood cells, especially the subset of white blood cells known as lymphocytes. In fact, lymphocytes are the main cellular components of lymph.

The lymph that enters lymph capillaries in tissues is transported through the lymphatic vessel network to two large lymphatic ducts in the upper chest. From there, the lymph flows into two major veins (called subclavian veins) of the cardiovascular system. Unlike blood, lymph is not pumped through its network of vessels. Instead, lymph moves through lymphatic vessels via a combination of contractions of the vessels themselves and the forces applied to the vessels externally by skeletal muscles, similarly to how blood moves through veins. Lymphatic vessels also contain numerous valves that keep lymph flowing in just one direction, thereby preventing backflow.

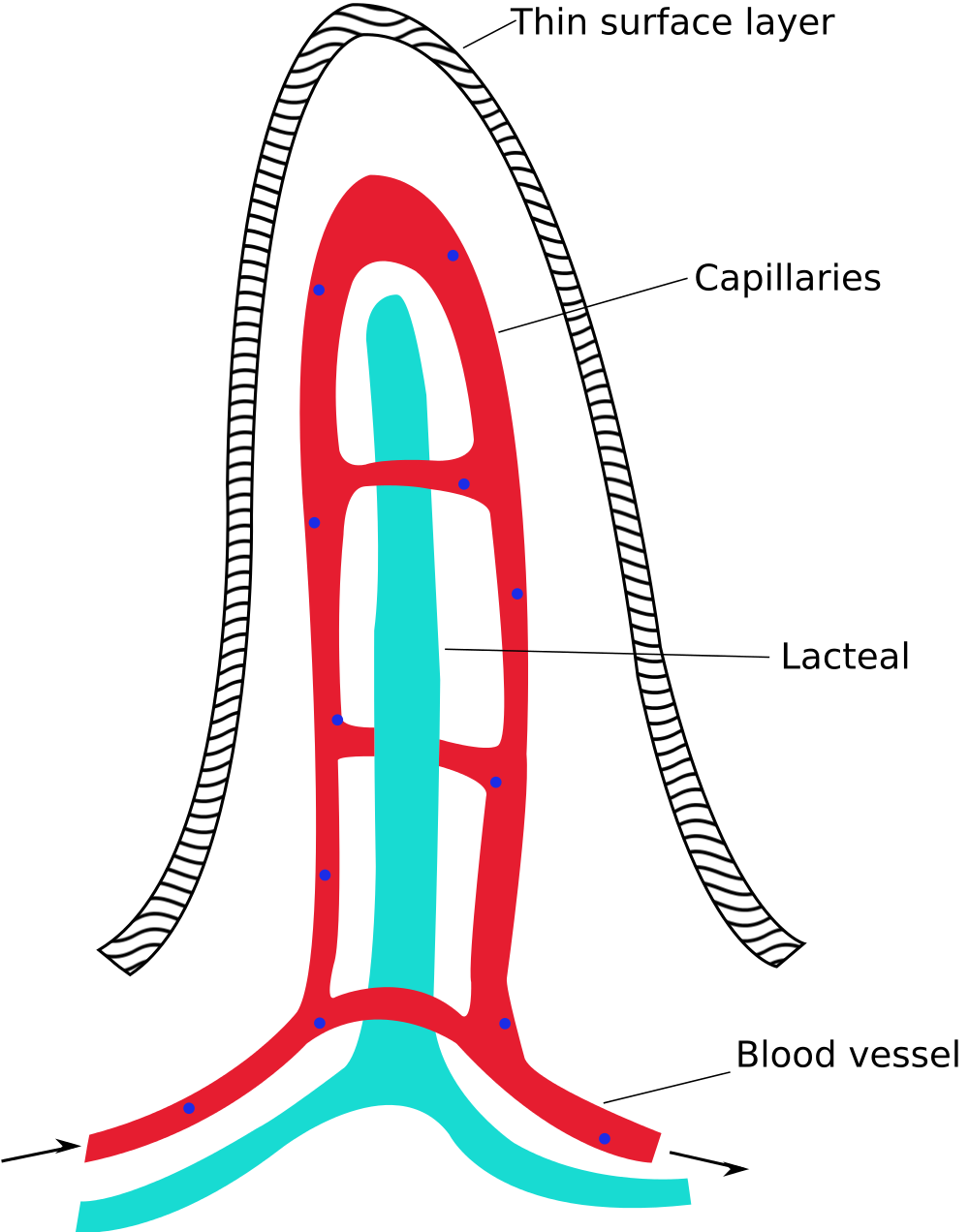

Digestive Function of the Lymphatic System

Lymphatic vessels called lacteals (see Figure 17.3.4) are present in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, mainly in the small intestine. Each tiny villus in the lining of the small intestine has an internal bed of capillaries and lacteals. The capillaries absorb most nutrients from the digestion of food into the blood. The lacteals absorb mainly fatty acids from lipid digestion into the lymph, forming a fatty-acid-enriched fluid called chyle. Vessels of the lymphatic network then transport chyle from the small intestine to the main lymphatic ducts in the chest, from which it drains into the blood circulation. The nutrients in chyle then circulate in the blood to the liver, where they are processed along with the other nutrients that reach the liver directly via the bloodstream.

Immune Function of the Lymphatic System