Reading: The Labor Market

How many workers should a firm hire? Too few production will be less than profit maximizing output rate. Too many and productions could slow down as they bump into each other.

The labor market, like all markets, has a demand and a supply. Why do firms demand labor? Why is an employer willing to pay you for your labor? It’s not because the employer likes you or is socially conscious. Rather, it’s because your labor is worth something to the employer–your work brings in revenues to the firm. How much is an employer willing to pay? That depends on the skills and experience you bring to the firm.

If a firm wants to maximize profits, it will never pay more (in terms of wages and benefits) for a worker than the value of his or her marginal productivity to the firm. We call this the first rule of labor markets.

Suppose a worker can produce two widgets per hour and the firm can sell each widget for $4 each. Then the worker is generating $8 per hour in revenues to the firm, and a profit-maximizing employer will pay the worker up to, but no more than, $8 per hour, because that is what the worker is worth to the firm.

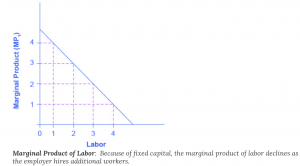

Recall the definition of marginal product. Marginal product is the additional output a firm can produce by adding one more worker to the production process. Since employers often hire labor by the hour, we’ll define marginal product as the additional output the firm produces by adding one more worker hour to the production process. In this chapter, we assume that workers are homogeneous—they have the same background, experience and skills and they put in the same amount of effort. Thus, marginal product depends on the capital and technology with which workers have to work.

A typist can type more pages per hour with an electric typewriter than a manual typewriter, and he or she can type even more pages per hour with a personal computer and word processing software. A ditch digger can dig more cubic feet of dirt in an hour with a backhoe than with at shovel.

Thus, we can define the demand for labor as the marginal product of labor times the value of that output to the firm.

| # of Workers (L) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Marginal Product of Labor | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

On what does the value of each worker’s marginal product depend? If we assume that the employer sells its output in a perfectly competitive market, the value of each worker’s output will be the market price of the product. Thus,

Demand for Labor = MPL x P = Marginal Revenue Product of Labor (MRP)

We show this in (Figure), which is an expanded version of (Figure)

| # of Workers (L) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Marginal Product of Labor | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Price of Output | $4 | $4 | $4 | $4 |

| Marginal Revenue Product | $16 | $12 | $8 | $4 |

The question for any firm is how much labor to hire.

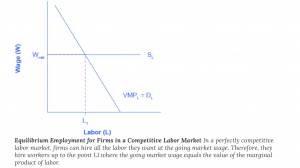

We can define a Perfectly Competitive Labor Market as one where firms can hire all the labor they wish at the going market wage. Think about secretaries in a large city. Employers who need secretaries can probably hire as many as they need if they pay the going wage rate.

Graphically, this means that firms face a horizontal supply curve for labor, at the Market Wage Rate

Given the market wage, profit maximizing firms hire workers up to the point where: Wmkt = MRP of Labor

where VMP of labor is the Marginal Revenue Product of Labor

where VMP of labor is the Marginal Revenue Product of Labor