Cognitive Development in Early Childhood

Jennifer Paris; Antoinette Ricardo; Dawn Rymond; and Jean Zaar

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Compare and contrast Piaget and Vygotsky’s beliefs about cognitive development.

- Explain the role of information processing in cognitive development.

- Discuss how preschool-aged children understand their worlds.

- Put cognitive and language milestones into the order in which they appear in typically developing children.

Introduction

Early childhood is a time of pretending, blending fact and fiction, and learning to think of the world using language. As young children move away from needing to touch, feel, and hear about the world toward learning some basic principles about how the world works, they hold some pretty interesting initial ideas. For example, while adults have no concerns with taking a bath, a child of three might genuinely worry about being sucked down the drain.1

Figure 8.1 – A child in a bathtub.2

A child might protest if told that something will happen “tomorrow” but be willing to accept an explanation that an event will occur “today after we sleep.” Or the young child may ask, “How long are we staying? From here to here?” while pointing to two points on a table. Concepts such as tomorrow, time, size and distance are not easy to grasp at this young age. Understanding size, time, distance, fact and fiction are all tasks that are part of cognitive development in the preschool years.3

Piaget’s Preoperational Intelligence

Piaget’s stage that coincides with early childhood is the preoperational stage. The word operational means logical, so these children were thought to be illogical. However, they were learning to use language or to think of the world symbolically. Let’s examine some of Piaget’s assertions about children’s cognitive abilities at this age.

Pretend Play

Pretending is a favorite activity at this time. A toy has qualities beyond the way it was designed to function and can now be used to stand for a character or object unlike anything originally intended. A teddy bear, for example, can be a baby or the queen of a faraway land!

Figure 8.2 – A child pretending to buy items at a toy grocery store.4

According to Piaget, children’s pretend play helps them solidify new schemes they were developing cognitively. This play, then, reflects changes in their conceptions or thoughts. However, children also learn as they pretend and experiment. Their play does not simply represent what they have learned (Berk, 2007).

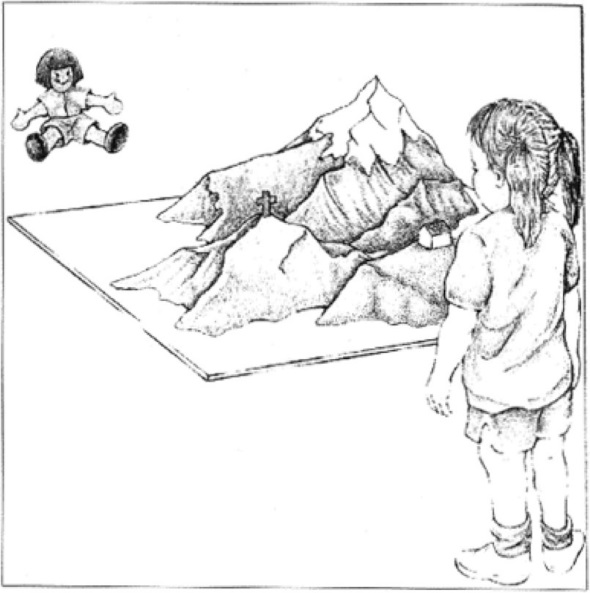

Egocentrism

Egocentrism in early childhood refers to the tendency of young children to think that everyone sees things in the same way as the child. Piaget’s classic experiment on egocentrism involved showing children a 3-dimensional model of a mountain and asking them to describe what a doll that is looking at the mountain from a different angle might see. Children tend to choose a picture that represents their own view, rather than that of the doll. However, children tend to use different sentence structures and vocabulary when addressing a younger child or an older adult. This indicates some awareness of the views of others.

Figure 8.3 – Piaget’s egocentrism experiment.5

Syncretism

Syncretism refers to a tendency to think that if two events occur simultaneously, one caused the other. An example of this is a child putting on their bathing suit to turn it to summertime.

Animism

Attributing lifelike qualities to objects is referred to as animism. The cup is alive, the chair that falls down and hits the child’s ankle is mean, and the toys need to stay home because they are tired. Cartoons frequently show objects that appear alive and take on lifelike qualities. Young children do seem to think that objects that move may be alive but after age 3, they seldom refer to objects as being alive (Berk, 2007).

Classification Errors

Preoperational children have difficulty understanding that an object can be classified in more than one way. For example, if shown three white buttons and four black buttons and asked whether there are more black buttons or buttons, the child is likely to respond that there are more black buttons. As the child’s vocabulary improves and more schemes are developed, the ability to classify objects improves.6

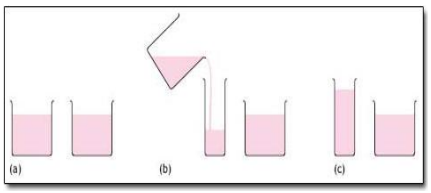

Conservation Errors

Conservation refers to the ability to recognize that moving or rearranging matter does not change the quantity. Let’s look at an example. A father gave a slice of pizza to 10-year-old Keiko and another slice to 3-year-old Kenny. Kenny’s pizza slice was cut into five pieces, so Kenny told his sister that he got more pizza than she did. Kenny did not understand that cutting the pizza into smaller pieces did not increase the overall amount. This was because Kenny exhibited Centration, or focused on only one characteristic of an object to the exclusion of others.

Kenny focused on the five pieces of pizza to his sister’s one piece even though the total amount was the same. Keiko was able to consider several characteristics of an object than just one. Because children have not developed this understanding of conservation, they cannot perform mental operations.

The classic Piagetian experiment associated with conservation involves liquid (Crain, 2005). As seen below, the child is shown two glasses (as shown in a) which are filled to the same level and asked if they have the same amount. Usually the child agrees they have the same amount. The researcher then pours the liquid from one glass to a taller and thinner glass (as shown in b). The child is again asked if the two glasses have the same amount of liquid. The preoperational child will typically say the taller glass now has more liquid because it is taller. The child has concentrated on the height of the glass and fails to conserve.7

Figure 8.4 – Piagetian liquid conservation experiments.8

Cognitive Schemas

As introduced in the first chapter, Piaget believed that in a quest for cognitive equilibrium, we use schemas (categories of knowledge) to make sense of the world. And when new experiences fit into existing schemas, we use assimilation to add that new knowledge to the schema. But when new experiences do not match an existing schema, we use accommodation to add a new schema. During early childhood, children use accommodation often as they build their understanding of the world around them.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development

As introduced in Chapter 1, Lev Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist who argued that culture has a major impact on a child’s cognitive development. He believed that the social interactions with adults and more knowledgeable peers can facilitate a child’s potential for learning. Without this interpersonal instruction, he believed children’s minds would not advance very far as their knowledge would be based only on their own discoveries. Let’s review some of Vygotsky’s key concepts.

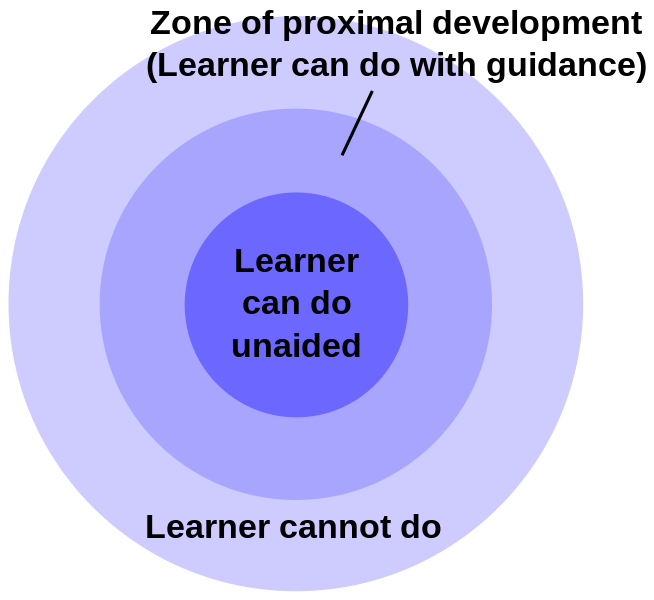

Zone of Proximal Development and Scaffolding

Vygotsky’s best known concept is the zone of proximal development (ZPD). Vygotsky stated that children should be taught in the ZPD, which occurs when they can perform a task with assistance, but not quite yet on their own. With the right kind of teaching, however, they can accomplish it successfully. A good teacher identifies a child’s ZPD and helps the child stretch beyond it. Then the adult (teacher) gradually withdraws support until the child can then perform the task unaided. Researchers have applied the metaphor of scaffolds (the temporary platforms on which construction workers stand) to this way of teaching. Scaffolding is the temporary support that parents or teachers give a child to do a task.

Figure 8.5 – Zone of proximal development.9

Private Speech

Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something, or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from another’s point of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private speech or inner speech.

Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something. This inner speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962).10

Contrast with Piaget

Piaget was highly critical of teacher-directed instruction, believing that teachers who take control of the child’s learning place the child into a passive role (Crain, 2005). Further, teachers may present abstract ideas without the child’s true understanding, and instead they just repeat back what they heard. Piaget believed children must be given opportunities to discover concepts on their own. As previously stated, Vygotsky did not believe children could reach a higher cognitive level without instruction from more learned individuals. Who is correct? Both theories certainly contribute to our understanding of how children learn.

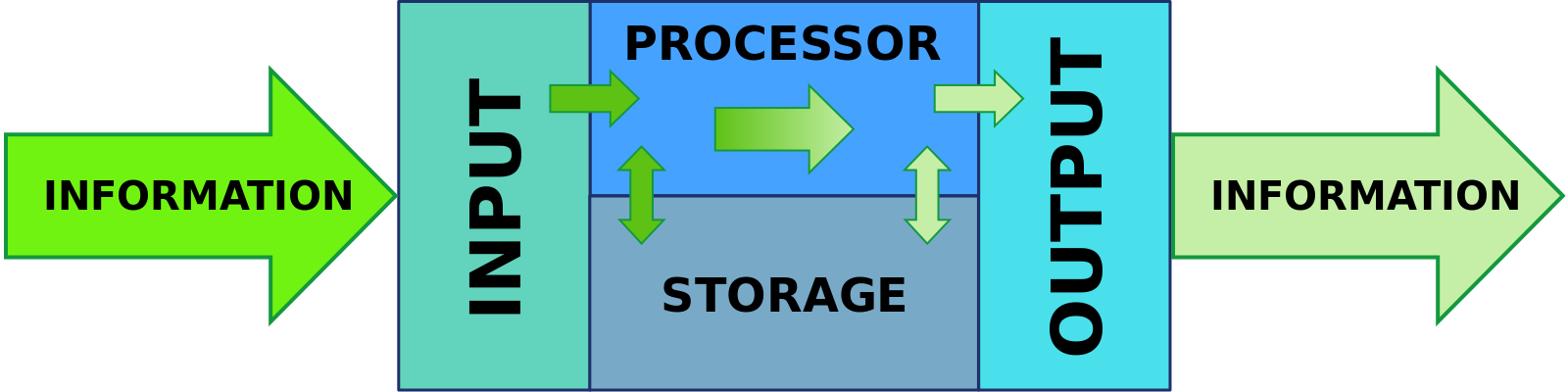

Information Processing

Information processing researchers have focused on several issues in cognitive development for this age group, including improvements in attention skills, changes in the capacity, and the emergence of executive functions in working memory. Additionally, in early childhood memory strategies, memory accuracy, and autobiographical memory emerge. Early childhood is seen by many researchers as a crucial time period in memory development (Posner & Rothbart, 2007).

Figure 8.6 – How information is processed.11

Attention

Changes in attention have been described by many as the key to changes in human memory (Nelson & Fivush, 2004; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). However, attention is not a unified function; it is comprised of sub-processes. The ability to switch our focus between tasks or external stimuli is called divided attention or multitasking. This is separate from our ability to focus on a single task or stimulus, while ignoring distracting information, called selective attention. Different from these is sustained attention, or the ability to stay on task for long periods of time. Moreover, we also have attention processes that influence our behavior and enable us to inhibit a habitual or dominant response, and others that enable us to distract ourselves when upset or frustrated.

Divided Attention

Young children (age 3-4) have considerable difficulties in dividing their attention between two tasks, and often perform at levels equivalent to our closest relative, the chimpanzee, but by age five they have surpassed the chimp (Hermann, Misch, Hernandez-Lloreda & Tomasello, 2015; Hermann & Tomasello, 2015). Despite these improvements, 5-year-olds continue to perform below the level of school-age children, adolescents, and adults.

Selective Attention

Children’s ability with selective attention tasks improve as they age. However, this ability is also greatly influenced by the child’s temperament (Rothbart & Rueda, 2005), the complexity of the stimulus or task (Porporino, Shore, Iarocci & Burack, 2004), and along with whether the stimuli are visual or auditory (Guy, Rogers & Cornish, 2013). Guy et al. (2013) found that children’s ability to selectively attend to visual information outpaced that of auditory stimuli. This may explain why young children are not able to hear the voice of the teacher over the cacophony of sounds in the typical preschool classroom (Jones, Moore & Amitay, 2015). Jones and his colleagues found that 4 to 7 year-olds could not filter out background noise, especially when its frequencies were close in sound to the target sound. In comparison, 8- to 11-year-old children often performed similar to adults.

Figure 8.7 – A group of children making crafts.12

Sustained Attention

Most measures of sustained attention typically ask children to spend several minutes focusing on one task, while waiting for an infrequent event, while there are multiple distractors for several minutes. Berwid, Curko-Kera, Marks & Halperin (2005) asked children between the ages of 3 and 7 to push a button whenever a “target” image was displayed, but they had to refrain from pushing the button when a non-target image was shown. The younger the child, the more difficulty he or she had maintaining their attention.

Figure 8.8 – A child playing a game that measures her sustained attention.13

Memory

Based on studies of adults, people with amnesia, and neurological research on memory, researchers have proposed several “types” of memory (see Figure 4.14). Sensory memory (also called the sensory register) is the first stage of the memory system, and it stores sensory input in its raw form for a very brief duration; essentially long enough for the brain to register and start processing the information. Studies of auditory sensory memory show that it lasts about one second in 2 year-olds, two seconds in 3-year-olds, more than two seconds in 4-year-olds, and three to five seconds in 6-year-olds (Glass, Sachse, & von Suchodoletz, 2008). Other researchers have also found that young children hold sounds for a shorter duration than do older children and adults, and that this deficit is not due to attentional differences between these age groups, but reflects differences in the performance of the sensory memory system (Gomes et al., 1999). The second stage of the memory system is called short-term or working memory. Working memory is the component of memory in which current conscious mental activity occurs.

Working memory often requires conscious effort and adequate use of attention to function effectively. As you read earlier, children in this age group struggle with many aspects of attention and this greatly diminishes their ability to consciously juggle several pieces of information in memory. The capacity of working memory, that is the amount of information someone can hold in consciousness, is smaller in young children than in older children and adults. The typical adult and teenager can hold a 7 digit number active in their short-term memory. The typical 5-year-old can hold only a 4 digit number active. This means that the more complex a mental task is, the less efficient a younger child will be in paying attention to, and actively processing, information in order to complete the task.

Figure 8.8 – A child thinking.14

Changes in attention and the working memory system also involve changes in executive function. Executive function (EF) refers to self-regulatory processes, such as the ability to inhibit a behavior or cognitive flexibility, that enable adaptive responses to new situations or to reach a specific goal. Executive function skills gradually emerge during early childhood and continue to develop throughout childhood and adolescence. Like many cognitive changes, brain maturation, especially the prefrontal cortex, along with experience influence the development of executive function skills.

A child shows higher executive functioning skills when the parents are more warm and responsive, use scaffolding when the child is trying to solve a problem, and provide cognitively stimulating environments for the child (Fay-Stammbach, Hawes & Meredith, 2014). For instance, scaffolding was positively correlated with greater cognitive flexibility at age two and inhibitory control at age four (Bibok, Carpendale & Müller, 2009). In Schneider, Kron-Sperl and Hunnerkopf’s (2009) longitudinal study of 102 kindergarten children, the majority of children used no strategy to remember information, a finding that was consistent with previous research. As a result, their memory performance was poor when compared to their abilities as they aged and started to use more effective memory strategies.

The third component in memory is long-term memory, which is also known as permanent memory. A basic division of long-term memory is between declarative and non-declarative memory.

- Declarative memories, sometimes referred to as explicit memories, are memories for facts or events that we can consciously recollect. Declarative memory is further divided into semantic and episodic memory.

- Semantic memories are memories for facts and knowledge that are not tied to a timeline,

- Episodic memories are tied to specific events in time.

- Non- declarative memories, sometimes referred to as implicit memories, are typically automated skills that do not require conscious recollection.

Autobiographical memory is our personal narrative. Adults rarely remember events from the first few years of life. In other words, we lack autobiographical memories from our experiences as an infant, toddler and very young preschooler. Several factors contribute to the emergence of autobiographical memory including brain maturation, improvements in language, opportunities to talk about experiences with parents and others, the development of theory of mind, and a representation of “self” (Nelson & Fivush, 2004). Two-year-olds do remember fragments of personal experiences, but these are rarely coherent accounts of past events (Nelson & Ross, 1980). Between 2 and 2 1⁄2 years of age children can provide more information about past experiences. However, these recollections require considerable prodding by adults (Nelson & Fivush, 2004). Over the next few years children will form more detailed autobiographical memories and engage in more reflection of the past.

Neo-Piagetians

As previously discussed, Piaget’s theory has been criticized on many fronts, and updates to reflect more current research have been provided by the Neo-Piagetians, or those theorists who provide “new” interpretations of Piaget’s theory. Morra, Gobbo, Marini and Sheese (2008) reviewed Neo-Piagetian theories, which were first presented in the 1970s, and identified how these “new” theories combined Piagetian concepts with those found in Information Processing. Similar to Piaget’s theory, Neo-Piagetian theories believe in constructivism, assume cognitive development can be separated into different stages with qualitatively different characteristics, and advocate that children’s thinking becomes more complex in advanced stages. Unlike Piaget, Neo-Piagetians believe that aspects of information processing change the complexity of each stage, not logic as determined by Piaget.

Neo-Piagetians propose that working memory capacity is affected by biological maturation, and therefore restricts young children’s ability to acquire complex thinking and reasoning skills. Increases in working memory performance and cognitive skills development coincide with the timing of several neurodevelopmental processes. These include myelination, axonal and synaptic pruning, changes in cerebral metabolism, and changes in brain activity (Morra et al., 2008).

Myelination especially occurs in waves between birth and adolescence, and the degree of myelination in particular areas explains the increasing efficiency of certain skills. Therefore, brain maturation, which occurs in spurts, affects how and when cognitive skills develop. Additionally, all Neo-Piagetian theories support that experience and learning interact with biological maturation in shaping cognitive development.15

Children’s Understanding of the World

Both Piaget and Vygotsky believed that children actively try to understand the world around them. More recently developmentalists have added to this understanding by examining how children organize information and develop their own theories about the world.

Theory-Theory

The tendency of children to generate theories to explain everything they encounter is called theory-theory. This concept implies that humans are naturally inclined to find reasons and generate explanations for why things occur. Children frequently ask question about what they see or hear around them. When the answers provided do not satisfy their curiosity or are too complicated for them to understand, they generate their own theories. In much the same way that scientists construct and revise their theories, children do the same with their intuitions about the world as they encounter new experiences (Gopnik & Wellman, 2012). One of the theories they start to generate in early childhood centers on the mental states; both their own and those of others.

Figure 8.9 – What theories might this boy be creating?16

Theory of Mind

Theory of mind refers to the ability to think about other people’s thoughts. This mental mind reading helps humans to understand and predict the reactions of others, thus playing a crucial role in social development. One common method for determining if a child has reached this mental milestone is the false belief task, described below.

The research began with a clever experiment by Wimmer and Perner (1983), who tested whether children can pass a false-belief test (see Figure 4.17). The child is shown a picture story of Sally, who puts her ball in a basket and leaves the room. While Sally is out of the room, Anne comes along and takes the ball from the basket and puts it inside a box. The child is then asked where Sally thinks the ball is located when she comes back to the room. Is she going to look first in the box or in the basket? The right answer is that she will look in the basket, because that’s where she put it and thinks it is; but we have to infer this false belief against our own better knowledge that the ball is in the box.

|

Figure 8.10 – A ball.17 |

Figure 8.11 – A basket.18 |

Figure 8.12 – A box.19 |

This is very difficult for children before the age of four because of the cognitive effort it takes. Three-year-olds have difficulty distinguishing between what they once thought was true and what they now know to be true. They feel confident that what they know now is what they have always known (Birch & Bloom, 2003). Even adults need to think through this task (Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, 2004).

To be successful at solving this type of task the child must separate what he or she “knows” to be true from what someone else might “think” is true. In Piagetian terms, they must give up a tendency toward egocentrism. The child must also understand that what guides people’s actions and responses are what they “believe” rather than what is reality. In other words, people can mistakenly believe things that are false and will act based on this false knowledge. Consequently, prior to age four children are rarely successful at solving such a task (Wellman, Cross & Watson, 2001).

Researchers examining the development of theory of mind have been concerned by the overemphasis on the mastery of false belief as the primary measure of whether a child has attained theory of mind. Wellman and his colleagues (Wellman, Fang, Liu, Zhu & Liu, 2006) suggest that theory of mind is comprised of a number of components, each with its own developmental timeline (see Table 4.2).

Two-year-olds understand the diversity of desires, yet as noted earlier it is not until age four or five that children grasp false belief, and often not until middle childhood do they understand that people may hide how they really feel. In part, because children in early childhood have difficulty hiding how they really feel.

Cultural Differences in Theory of Mind

Those in early childhood in the US, Australia, and Germany develop theory of mind in the sequence outlined above. Yet, Chinese and Iranian preschoolers acquire knowledge access before diverse beliefs (Shahaeian, Peterson, Slaughter & Wellman, 2011). Shahaeian and colleagues suggested that cultural differences in childrearing may account for this reversal.

Parents in collectivistic cultures, such as China and Iran, emphasize conformity to the family and cultural values, greater respect for elders, and the acquisition of knowledge and academic skills more than they do autonomy and social skills (Frank, Plunkett & Otten, 2010). This could reduce the degree of familial conflict of opinions expressed in the family. In contrast, individualistic cultures encourage children to think for themselves and assert their own opinion, and this could increase the risk of conflict in beliefs being expressed by family members.

Figure 8.13 – A family from a non-Western culture.20

Figure 8.13 – A family from a non-Western culture.20

As a result, children in individualistic cultures would acquire insight into the question of diversity of belief earlier, while children in collectivistic cultures would acquire knowledge access earlier in the sequence. The role of conflict in aiding the development of theory of mind may account for the earlier age of onset of an understanding of false belief in children with siblings, especially older siblings (McAlister & Petersen, 2007; Perner, Ruffman & Leekman, 1994).

This awareness of the existence of theory of mind is part of social intelligence, such as recognizing that others can think differently about situations. It helps us to be self-conscious or aware that others can think of us in different ways and it helps us to be able to be understanding or be empathetic toward others. Moreover, this mind reading ability helps us to anticipate and predict people’s actions. The awareness of the mental states of others is important for communication and social skills.21

Milestones of Cognitive Development

The many theories of cognitive development and the different research that has been done about how children understand the world, has allowed researchers to study the milestones that children who are typically developing experience in early childhood. Here is a table that summarizes those.

Table 8.1 – Cognitive Milestones22

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do by This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Language Development

Vocabulary Growth

A child’s vocabulary expands between the ages of 2 to 6 from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through a process called fast-mapping. Words are easily learned by making connections between new words and concepts already known. The parts of speech that are learned depend on the language and what is emphasized. Children speaking verb-friendly languages such as Chinese and Japanese, tend to learn nouns more readily. But, those learning less verb-friendly languages such as English, seem to need assistance in grammar to master the use of verbs (Imai, et al, 2008).

Figure 8.14 – A woman instructing a girl on vocabulary.23

Literal Meanings

Children can repeat words and phrases after having heard them only once or twice. But they do not always understand the meaning of the words or phrases. This is especially true of expressions or figures of speech which are taken literally. For example, two preschool-aged girls began to laugh loudly while listening to a tape-recording of Disney’s “Sleeping Beauty” when the narrator reports, “Prince Phillip lost his head!” They imagine his head popping off and rolling down the hill as he runs and searches for it. Or a classroom full of preschoolers hears the teacher say, “Wow! That was a piece of cake!” The children began asking “Cake? Where is my cake? I want cake!”

Overregularization

Children learn rules of grammar as they learn language but may apply these rules inappropriately at first. For instance, a child learns to add “ed” to the end of a word to indicate past tense. Then form a sentence such as “I goed there. I doed that.” This is typical at ages 2 and 3. They will soon learn new words such as “went” and “did” to be used in those situations.

The Impact of Training

Remember Vygotsky and the zone of proximal development? Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations and encourage elaboration. The child exclaims, “I goed there!” and the adult responds, “You went there? Say, ‘I went there.’ Where did you go?” Children may be ripe for language as Chomsky suggests, but active participation in helping them learn is important for language development as well. The process of scaffolding is one in which the adult (or more skilled peer) provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned.

Language Milestones

The prior aspects of language development in early childhood can also be summarized into the progression of milestones children typically experience from ages 3 to 5. Here is a table of those.

Table 8.2 – Language Milestones24

|

Typical Age |

What Most Children Do By This Age |

|

3 years |

|

|

4 years |

|

|

5 years |

|

Conclusion

In this chapter we covered,

- Piaget’s preoperational stage.

- Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory.

- Information processing.

- How young children understand the world.

- Typical progression of cognitive and language development (milestones).

In the next chapter, we will finish covering early childhood education by looking at how children understand themselves and interact with the world.