10 2.2 Media Studies Theories

Learning Objectives

- Recognizing the need for critical thinking and academic analysis of media.

- Understanding the media’s ability to shape thinking, reality, and perceptions.

- Grasping basic overviews of different approaches like Marxist, symbolic interactions, agenda-setting theory, gatekeeper theory, framing theory, and limited capacity processing model.

bell hooks at a speaking engagement, from hooks’ own Flickr page. Public domain.

“Understanding knowledge as an essential element of love is vital because we are bombarded daily with messages that tell us love is about mystery, about that which cannot be known. We see movies in which people are represented as being in love who never talk with one another, who fall into bed without ever discussing their bodies, their sexual needs, their likes and dislikes. Indeed, the message is received from the mass media is that knowledge makes love less compelling; that it is ignorance that gives love its erotic and transgressive edge. These messages are brought to us by profiteering producers who have no clue about the art of loving, who substitute their mystified visions because they do not really know how to genuinely portray loving interaction.” — bell hooks from her book All About Love: New Visions

The Academic Approach to Studying the Mass Media

Even early into this course, you are probably already aware of the powerful role the mass media play in society, but you may not yet question whether society benefits from this arrangement. In general, the mass media could do a better job of representing all sorts of groups and group cultures. The mass media could also represent abstract concepts like love, trust and greed in more meaningful ways. This is not to say that the mass media have failed in this regard, but there is much room for improvement.

As active audience members, as hybrid producer-users or “produsers” (to use a term coined by Axel Bruns), you must not only be selective but also critical of what you consume. Whether you become media professionals or not, it will ultimately be your job as media consumers to remake the mass media in ways that better represent the depth of human experience.

Whether your interest is a religion, a fandom, or an abstract concept like love (one of the greatest of abstractions), you have the power to participate in the media production redefining how others understand it.

No, this is not a book about love. Yes, love and related concepts are commodified in the mass media; however, the disruption that has echoed in political spheres and often in the ways family and cultural group members speak to one another about politics also opens up space for critical thinking. That is, the same disruption described in Chapter 2 that allows for social upheaval also allows for a time of reflection and critical thinking about how society and its media function.

This chapter gives you some tools developed by mass communication scholars to develop your critical eye when viewing messages as products in the mass media. If massive numbers of “produsers” can reshape the media landscape, we have to re-think the role of mass media professionals. Assisting people in the process of meaning-making — that is, making mass media with audiences instead of for them, and aiding them in their own communication efforts — could open up a new purpose and new industries for those who are mentally prepared and daring enough to take the lead.

This chapter defines “media literacy” and touches on some key mass communication theories that are absolutely not meant to be left to molder in the digital cloud where this text”book” lives. Take these theories out, apply them and see how they work. Find out how useful they can be and what their limitations are.

This text presents an image of entire societies and cultures swimming in a sea of media. Consider these concepts your first set of snorkel and swim-fins.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is media literacy put into action. Besides contributing to the creation of meaning by making your own mass media messages (perhaps in collaboration with professionals), you can ask who owns major mass media corporations. Scholars have found that more than half of the mass media channels available to mass audiences in America are owned by only five corporations or firms.

One author’s research, conducted with two research partners in graduate school, has shown that just by making people aware of the nature of media ownership, you can encourage them to be skeptical of mass media content.

This text has already established that mass communication is what makes society in the physical world work. Information, often in the form of messages in the mass media, permeates institutional interactions and passes between all of us in our homes and schools and businesses. The information conveyed in the mass media gets interpreted in organizational, group and interpersonal communication contexts. These systems influence each other, but mass media messages tend to envelop and permeate other forms of communication. Thus, if you learn to be skeptical of the information you receive in the mass media, you learn how to critique the whole global social system.

Critique this Book

Reading closely, you will have undoubtedly found value judgments in this text already. You may be inclined to assign political values to this text in our hyper-partisan cultural environment. You are welcome to do this. You are encouraged to do this. You must think critically about the cultural values expressed not only in this text but also in your other textbooks and in the history and literature you read.

But you also must think critically about your preferred media outlets. Where do they get their information from? Who owns them? No single revelation about the mass media will tell you everything you need to know. You have to begin to see nuance and to think for yourself what aspects of the mass media matter most to you, what things you think should change, how you might change them, and what you can live with.

It is part of the responsibility of citizens now to critique messages that come to us via mass media, as well as messages from leaders who bypass mass media gatekeepers and fact checkers. It is also a sound career strategy for those who go into the mass communication field to learn to be able to critique messages, messengers and owners in the corporate mass media field of work and play. To know where the mass media industry is headed, you must be able to think critically about where it comes from.

Much of the rest of this book breaks down different mass media channels and looks briefly at the history of how each came to be, what and whom each channel serves, and how convergence in a digitally networked society might affect the future of each medium. This text also returns several times to “big picture” questions about the dynamic relationship between media and society as seen from the perspective of the various mass communication channels and platforms.

The Dichotomy Between the Media and the “Real World”

For nearly the dozenth time in this text already, your author has referenced a “dynamic.” The mass media reflect our social norms and expectations and, dynamically, they shape our norms and expectations.

To the extent they are shaped by mass media, our perceptions of reality are very much artificial — but not entirely so. How artificial is too artificial? Different individuals and different cultures differ in the amount of nonsense they can tolerate.

The real challenge to us as young media professionals and scholars is to try to determine what is artificial in the vast array of messages delivered to us at all times by the mass media. One of the best ways to do this is to get off of social media platforms and talk to people in person. We should also dig a bit into the information we consume and ask, “How do they know?” Whenever a message comes to us from a mass media outlet or from a friend’s social media post, the media literate individual seeks to know what underlies each claim.

The question is not whether you believe it. The question is: On what grounds is a message in the mass media or in social media believable?

Now that people are constantly using technology and even wearing it, it is becoming more difficult to separate messages mediated by professionals, who pledge ethically to adhere to disseminating factual information (such as most journalists), from poorly-supported, opinion-only content or outright misinformation, which may be spread far and wide by friends and family.

We are living in a media age where we may not trust our own family members’ social media posts. Things they think are important might not only be unimportant to us, they might be distasteful or even wrong. There are real-world consequences to sharing misinformation on social media platforms. Question the sources’ sources. Talk to people in tangible spaces apart from social media platforms, and you can learn to see what is supported by fact in the physical world and its digital networks.

The Bad Dynamic

Your media choices matter. In the network society, when mass media content is ubiquitous on mobile phones and is often projected into public spaces, it can be difficult to differentiate between your independent preferences and the opinions you are encouraged to carry by advertisers who constantly bombard you.

Without human interaction outside of the deluge of electronic information, it can be nearly impossible to figure out for yourself if what you like is a response to the quality of the media content or if you are responding to carefully targeted marketing campaigns.

The system of checks and balances in which you can compare your real life experiences to what you see and hear in the mass media may break down. A pessimistic view is that we may enter a constant state of depression on a social level because we are cognitively incapable of comprehending all of the information presented to us and we lack ways of taking regular “reality checks.”

Feelings of isolation and inadequacy coupled with cognitive overload create the potential for a host of social issues. Additionally, the images we see in ads and the perfected versions of themselves people present on social media usually do not reflect applied critical thinking.

The “bad dynamic” that comes into play is one where glossy identities are carefully constructed and protected while our real identities rapidly disintegrate. We may establish a society where many people have identity issues, and those issues are constantly worsening. It may seem at times as though we are headed for a massive collective mental breakdown.

What good is media literacy? Thinking critically about the mass media and content spread on social media helps us critique constructed images and accept our own shortcomings. If we look for ways to relate to one another besides our overlapping common culture interests, we may find deeper connections are possible. We can share imperfections and tackle doubts, but only if we acknowledge them in our media world first.

What follows are a set of mass communication theories arrived at through the analysis of facts and data by thousands of scholars over the course of nearly 100 years. As an academic field, mass communication is young, but there are several theories, or guiding abstractions, that can help us to see how our society is structured and what roles the mass media play in society at all levels.

Early media studies focused on the use of mass media in propaganda and persuasion. However, journalists and researchers soon looked to behavioral sciences to help figure out the effect of mass media and communications on society. Scholars have developed many different approaches and theories to figure this out. You can refer to these theories as you research and consider the media’s effect on culture.

Widespread fear that mass-media messages could outweigh other stabilizing cultural influences, such as family and community, led to what is known as the direct effects model of media studies. This model assumed that audiences passively accepted media messages and would exhibit predictable reactions in response to those messages. For example, following the radio broadcast of War of the Worlds in 1938 (which was a fictional news report of an alien invasion), some people panicked and believed the story to be true.

The Direct Effects Theory and Subsequent Challenges

Early media studies focused on the use of mass media in propaganda and persuasion. However, journalists and researchers soon looked to behavioral sciences to help figure out the effect of mass media and communications on society. Scholars have developed many different approaches and theories to figure this out. You can refer to these theories as you research and consider the media’s effect on culture.

Widespread fear that mass-media messages could outweigh other stabilizing cultural influences, such as family and community, led to what is known as the direct effects model of media studies. This model assumed that audiences passively accepted media messages and would exhibit predictable reactions in response to those messages. For example, following the radio broadcast of War of the Worlds in 1938 (which was a fictional news report of an alien invasion), some people panicked and believed the story to be true

The results of the People’s Choice Study challenged this model. Conducted in 1940, the study attempted to gauge the effects of political campaigns on voter choice. Researchers found that voters who consumed the most media had generally already decided for which candidate to vote, while undecided voters generally turned to family and community members to help them decide. The study thus discredited the direct effects model and influenced a host of other media theories (Hanson, 2009). These theories do not necessarily give an all-encompassing picture of media effects but rather work to illuminate a particular aspect of media influence.

Marshall McLuhan’s Influence on Media Studies

During the early 1960s, English professor Marshall McLuhan wrote two books that had an enormous effect on the history of media studies. Published in 1962 and 1964, respectively, the Gutenberg Galaxy and Understanding Media both traced the history of media technology and illustrated the ways these innovations had changed both individual behavior and the wider culture. Understanding Media introduced a phrase that McLuhan has become known for: “The medium is the message.” This notion represented a novel take on attitudes toward media—that the media themselves are instrumental in shaping human and cultural experience.

His bold statements about media gained McLuhan a great deal of attention as both his supporters and critics responded to his utopian views about the ways media could transform 20th-century life. McLuhan spoke of a media-inspired “global village” at a time when Cold War paranoia was at its peak and the Vietnam War was a hotly debated subject. Although 1960s-era utopians received these statements positively, social realists found them cause for scorn. Despite—or perhaps because of—these controversies, McLuhan became a pop culture icon, mentioned frequently in the television sketch-comedy program Laugh-In and appearing as himself in Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall.

The Internet and its accompanying cultural revolution have made McLuhan’s bold utopian visions seem like prophecies. Indeed, his work has received a great deal of attention in recent years. Analysis of McLuhan’s work has, interestingly, not changed very much since his works were published. His supporters point to the hopes and achievements of digital technology and the utopian state that such innovations promise. The current critique of McLuhan, however, is a bit more revealing of the state of modern media studies. Media scholars are much more numerous now than they were during the 1960s, and many of these scholars criticize McLuhan’s lack of methodology and theoretical framework.

Despite his lack of scholarly diligence, McLuhan had a great deal of influence on media studies. Professors at Fordham University have formed an association of McLuhan-influenced scholars. McLuhan’s other great achievement is the popularization of the concept of media studies. His work brought the idea of media effects into the public arena and created a new way for the public to consider the influence of media on culture (Stille, 2000).

Critical Media Theory

There are many critical theorists among mass communication scholars. They work to develop better analytical theories that teach us how to analyze messages in media systems and the mass media and help us to discuss with clarity what is beneficial and what is harmful to society.

Academic work is about digging deep. Scholars will often analyze one medium at one period in time to explain how certain groups or ideologies are depicted.

Marxist critical theory questions the hierarchical organization of society — who controls the means of production and whether that control benefits society or only small groups of people. Every society has and needs leaders, and one of the most important functions of society is to manage a functioning economy. At question in Marxist critical thought is how the rules of each economy, including the global economy, are set up. Do they benefit most people? Do they allow for merit to be rewarded? Do they create a system of fair competition? Are they set up for collaboration and mutual benefit?

Most scholars who apply critical theoretical models would hesitate to call themselves Marxists. Marx was both a scholar and a revolutionary, a term which academics rarely self-apply. Most Marxist critical thinkers suggest changes that society could make to be more inclusive and fair for a greater number of people, but what is fair will always be debated. There is no single line of Marxist thought. There is a small number who demand complete change in the global economic system, and there are thousands of critical theorists calling for more narrow or specific changes based on their observations in their areas of expertise — not just mass media analysis but all kinds of social analysis.

Historically, Marxist thought has been employed by dictators, often using mass media channels, to take power and often to wield it in horrendous ways. Marxist thought also guides the reasoning of some mainstream economists who help manage social democracies, which historically garner more good will than dictatorships. Scholars working with the critical theoretical point of view often note broad ways for society to improve as well as practical solutions that might help (although getting leaders to listen is another matter). Making cogent arguments and convincing people to hear them are very different things.

That said, ideas about questioning hierarchies and asking for whom social systems really work are still central to modern critical theory. This is what Marxist critique in media studies is all about: looking at symbols and underlying messages in all forms of media and discerning what purposes they serve, and asking whether they represent exploitation, corruption or any other social ill often found in closed hierarchies.

Agenda-Setting Theory

In contrast to the extreme views of the direct effects model, the agenda-setting theory of media stated that mass media determine the issues that concern the public rather than the public’s views. Under this theory, the issues that receive the most attention from media become the issues that the public discusses, debates, and demands action on. This means that the media is determining what issues and stories the public thinks about. Therefore, when the media fails to address a particular issue, it becomes marginalized in the minds of the public (Hanson).

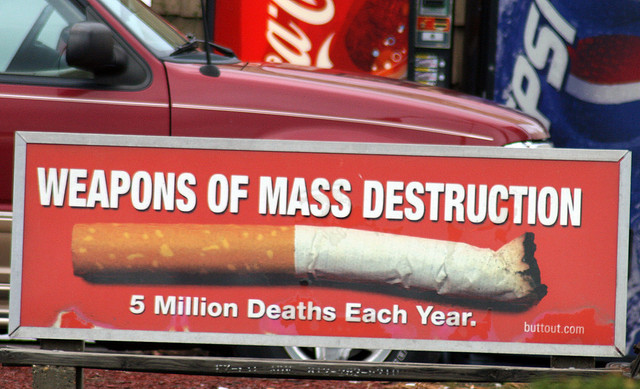

When critics claim that a particular media outlet has an agenda, they are drawing on this theory. Agendas can range from a perceived liberal bias in the news media to the propagation of cutthroat capitalist ethics in films. For example, the agenda-setting theory explains such phenomena as the rise of public opinion against smoking. Before the mass media began taking an antismoking stance, smoking was considered a personal health issue. By promoting antismoking sentiments through advertisements, public relations campaigns, and a variety of media outlets, the mass media moved smoking into the public arena, making it a public health issue rather than a personal health issue (Dearing & Rogers, 1996). More recently, coverage of natural disasters has been prominent in the news. However, as news coverage wanes, so does the general public’s interest.

Figure 2.7

Through a variety of antismoking campaigns, the health risks of smoking became a public agenda.

Quinn Dombrowski – Weapons of mass destruction – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Media scholars who specialize in agenda-setting research study the salience, or relative importance, of an issue and then attempt to understand what causes it to be important. The relative salience of an issue determines its place within the public agenda, which in turn influences public policy creation. Agenda-setting research traces public policy from its roots as an agenda through its promotion in the mass media and finally to its final form as a law or policy (Dearing & Rogers, 1996).

Uses and Gratifications Theory

Practitioners of the uses and gratifications theory study the ways the public consumes media. This theory states that consumers use the media to satisfy specific needs or desires. For example, you may enjoy watching a show like Dancing With the Stars while simultaneously tweeting about it on Twitter with your friends. Many people use the Internet to seek out entertainment, to find information, to communicate with like-minded individuals, or to pursue self-expression. Each of these uses gratifies a particular need, and the needs determine the way in which media is used. By examining factors of different groups’ media choices, researchers can determine the motivations behind media use (Papacharissi, 2009).

A typical uses and gratifications study explores the motives for media consumption and the consequences associated with use of that media. In the case of Dancing With the Stars and Twitter, you are using the Internet as a way to be entertained and to connect with your friends. Researchers have identified a number of common motives for media consumption. These include relaxation, social interaction, entertainment, arousal, escape, and a host of interpersonal and social needs. By examining the motives behind the consumption of a particular form of media, researchers can better understand both the reasons for that medium’s popularity and the roles that the medium fills in society. A study of the motives behind a given user’s interaction with Facebook, for example, could explain the role Facebook takes in society and the reasons for its appeal.

Uses and gratifications theories of media are often applied to contemporary media issues. The analysis of the relationship between media and violence that you read about in preceding sections exemplifies this. Researchers employed the uses and gratifications theory in this case to reveal a nuanced set of circumstances surrounding violent media consumption, as individuals with aggressive tendencies were drawn to violent media (Papacharissi, 2009).

Symbolic Interactionism

Another critical theoretical perspective is symbolic interactionism. The general idea comes from George Herbert Mead and suggests that people assign symbolic meaning to all sorts of phenomena around them. Our behavior is guided and influenced by our perceptions of reality and the symbols around us.

This means the way you act toward someone or something is based on the meaning you have for a person or thing. To effectively communicate, people use symbols with shared cultural meanings. Symbols can be constructed from just about anything, including material goods, education, or even the way people talk. Consequentially, these symbols are instrumental in the development of the self.

This theory helps media researchers better understand the field because of the important role the media plays in creating and propagating shared symbols. Because of the media’s power, it can construct symbols on its own. By using symbolic interactionist theory, researchers can look at the ways media affects a society’s shared symbols and, in turn, the influence of those symbols on the individual (Jansson-Boyd, 2010).

You are encouraged to think critically about the symbols you see and ask whether they are meant to manipulate you. We will not stop using symbols in communication; however, if you ask, “Why am I being shown this symbol at this time,” you can take a practical step in critically analyzing media.

One of the ways the media creates and uses cultural symbols to affect an individual’s sense of self is advertising. Advertisers work to give certain products a shared cultural meaning to make them desirable. For example, when you see someone driving a BMW, what do you think about that person? You may assume the person is successful or powerful because of the car he or she is driving. Ownership of luxury automobiles signifies membership in a certain socioeconomic class. Equally, technology company Apple has used advertising and public relations to attempt to become a symbol of innovation and nonconformity. Use of an Apple product, therefore, may have a symbolic meaning and may send a particular message about the product’s owner.

When asked to come up with an advertising campaign, college students often select a familiar category of beverage: energy drinks. RedBull uses the symbol of wings to show that an energy drink can pick you up and help you to move more quickly through your work. You can fly where you had stumbled. But that is not the only reason associate wings with Red Bull. Wings are a symbol of angels, saviors, and other powerful beings. If an individual has reservations about consuming something that may be unhealthy, moral symbolism and images of power are designed to subconscious guilt or misgivings.

Media also propagate other noncommercial symbols. National and state flags, religious images, and celebrities gain shared symbolic meanings through their representation in the media. It is up to you to critique images in the mass media as you see fit, but you should develop the skill and practice applying it.

Spiral of Silence

The spiral of silence theory, which states that those who hold a minority opinion silence themselves to prevent social isolation, explains the role of mass media in the formation and maintenance of dominant opinions. As minority opinions are silenced, the illusion of consensus grows, and so does social pressure to adopt the dominant position. This creates a self-propagating loop in which minority voices are reduced to a minimum and perceived popular opinion sides wholly with the majority opinion. For example, prior to and during World War II, many Germans opposed Adolf Hitler and his policies; however, they kept their opposition silent out of fear of isolation and stigma.

Because the media is one of the most important gauges of public opinion, this theory is often used to explain the interaction between media and public opinion. According to the spiral of silence theory, if the media propagates a particular opinion, then that opinion will effectively silence opposing opinions through an illusion of consensus. This theory relates especially to public polling and its use in the media (Papacharissi).

Media Logic

The media logic theory states that common media formats and styles serve as a means of perceiving the world. Today, the deep rooting of media in the cultural consciousness means that media consumers need engage for only a few moments with a particular television program to understand that it is a news show, a comedy, or a reality show. The pervasiveness of these formats means that our culture uses the style and content of these shows as ways to interpret reality. For example, think about a TV news program that frequently shows heated debates between opposing sides on public policy issues. This style of debate has become a template for handling disagreement to those who consistently watch this type of program.

Media logic affects institutions as well as individuals. The modern televangelist has evolved from the adoption of television-style promotion by religious figures, while the utilization of television in political campaigns has led candidates to consider their physical image as an important part of a campaign (Altheide & Snow, 1991).

Cultivation Analysis

The cultivation analysis theory states that heavy exposure to media causes individuals to develop an illusory perception of reality based on the most repetitive and consistent messages of a particular medium. This theory most commonly applies to analyses of television because of that medium’s uniquely pervasive, repetitive nature. Under this theory, someone who watches a great deal of television may form a picture of reality that does not correspond to actual life. Televised violent acts, whether those reported on news programs or portrayed on television dramas, for example, greatly outnumber violent acts that most people encounter in their daily lives. Thus, an individual who watches a great deal of television may come to view the world as more violent and dangerous than it actually is.

Cultivation analysis projects involve a number of different areas for research, such as the differences in perception between heavy and light users of media. To apply this theory, the media content that an individual normally watches must be analyzed for various types of messages. Then, researchers must consider the given media consumer’s cultural background of individuals to correctly determine other factors that are involved in his or her perception of reality. For example, the socially stabilizing influences of family and peer groups influence children’s television viewing and the way they process media messages. If an individual’s family or social life plays a major part in her life, the social messages that she receives from these groups may compete with the messages she receives from television.

Key Takeaways

- The now largely discredited direct effects model of media studies assumes that media audiences passively accept media messages and exhibit predictable reactions in response to those messages.

- Credible media theories generally do not give as much power to the media, such as the agenda-setting theory, or give a more active role to the media consumer, such as the uses and gratifications theory.

- Other theories focus on specific aspects of media influence, such as the spiral of silence theory’s focus on the power of the majority opinion or the symbolic interactionism theory’s exploration of shared cultural symbolism.

- Media logic and cultivation analysis theories deal with how media consumers’ perceptions of reality can be influenced by media messages.

Exercises

-

Media theories have a variety of uses and applications. Research one of the following topics and its effect on culture. Examine the topic using at least two of the approaches discussed in this section. Then, write a one-page essay about the topic you’ve selected.

- Media bias

- Internet habits

- Television’s effect on attention span

- Advertising and self-image

- Racial stereotyping in film

- Many of the theories discussed in this section were developed decades ago. Identify how each of these theories can be used today? Do you think these theories are still relevant for modern mass media? Why?

- Media is a huge part of education. What kinds of mass media do you engage with as a student in terms of what your instructors use in class? What kinds of instructional materials you engage with for your homework? What are other ways you use mass media to learn?

- There is a media instructor from England who has created a YouTube Channel called The Media Insider. Check out his page, especially the video titled

A photo of The Media Insider on YouTube.

References

David Altheide and Robert Snow, Media Worlds in the Postjournalism Era (New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1991), 9–11.

Dearing, James and Everett Rogers, Agenda-Setting (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996), 4.

Hanson, Ralph. Mass Communication: Living in a Media World (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2009), 80–81.

Hanson, Ralph. Mass Communication, 92.

Jansson-Boyd, Catherine. Consumer Psychology (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 59–62.

Papacharissi, Zizi. “Uses and Gratifications,” 153–154.

Papacharissi, Zizi. “Uses and Gratifications,” in An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research, ed. Don Stacks and Michael Salwen (New York: Routledge, 2009), 137.

Stille, Alexander. “Marshall McLuhan Is Back From the Dustbin of History; With the Internet, His Ideas Again Seem Ahead of Their Time,” New York Times, October 14, 2000, http://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/14/arts/marshall-mcluhan-back-dustbin-history-with-internet-his-ideas-again-seem-ahead.html.

Feedback/Errata