45 8.4 Issues and Trends in Film

Learning Objectives

- Recognize the role the major Hollywood studios have in shaping the movie industry today.

- Identify the major economic concerns involved in the production and distribution of films.

- Describe the effects of piracy on the movie industry.

Filmmaking is both a commercial and artistic venture. The current economic situation in the film industry, with increased production and marketing costs and lower audience turnouts in theaters, often sets the standard for the films big studios are willing to invest in. If you wonder why theaters have released so many remakes and sequels in recent years, this section may help you to understand the motivating factors behind those decisions.

The Influence of Hollywood

In the movie industry today, publicity and product are two sides of the same coin. Even films that get a lousy critical reception can do extremely well in ticket sales if their marketing campaigns manage to create enough hype. Similarly, two comparable films can produce very different results at the box office if they have been given different levels of publicity. This explains why the film What Women Want, starring Mel Gibson, brought in $33.6 million in its opening weekend in 2000, while a few months later, The Million Dollar Hotel, also starring Gibson, only brought in $29,483 during its opening weekend (Nash Information Services, 2000; Nash Information Services, 2001). Unlike in the days of the Hollywood studio system, no longer do the actors alone draw audiences to a movie. The owners of the nation’s major movie theater chains are keenly aware that a film’s success at the box office has everything to do with studio-generated marketing and publicity. What Women Want was produced by Paramount, one of the film industry’s six leading studios, and widely released (on 3,000 screens) after an extensive marketing effort, while The Million Dollar Hotel was produced by Lionsgate, an independent studio without the necessary marketing budget to fill enough seats for a wide release on opening weekend (Epstein, 2005).

The Hollywood “dream factory,” as Hortense Powdermaker labeled it in her 1950 book on the movie industry (Powdermaker), manufactures an experience that is part art and part commercial product (James, 1989). While the studios of today are less factory-like than they were in the vertically integrated studio system era, the coordinated efforts of a film’s production team can still be likened to a machine calibrated for mass production. The films the studios churn out are the result of a capitalist enterprise that ultimately looks to the “bottom line” to guide most major decisions. Hollywood is an industry, and as in any other industry in a mass market, its success relies on control of production resources and “raw materials” and on its access to mass distribution and marketing strategies to maximize the product’s reach and minimize competition (Belton). In this way, Hollywood has an enormous influence on the films to which the public has access.

Ever since the rise of the studio system in the 1930s, the majority of films have originated with the leading Hollywood studios. Today, the six big studios control 95 percent of the film business (Dick). In the early years, audiences were familiar with the major studios, their collections of actors and directors, and the types of films that each studio was likely to release. All of that changed with the decline of the studio system; screenwriters, directors, scripts, and cinematographers no longer worked exclusively with one studio, so these days, while moviegoers are likely to know the name of a film’s director and major actors, it’s unusual for them to identify a film with the studio that distributes it. However, studios are no less influential. The previews of coming attractions that play before a movie begins are controlled by the studios (Busis, 2010). Online marketing, TV commercials, and advertising partnerships with other industries—the name of an upcoming film, for instance, appearing on some Coke cans—are available tools for the big-budget studios that have the resources to commit millions to prerelease advertising. Even though studios no longer own the country’s movie theater chains, the films produced by the big six studios are the ones the multiplexes invariably show. Unlike films by independents, it’s a safe bet that big studio movies are the ones that will sell tickets.

The Blockbuster Standard

While it may seem like the major studios are making heavy profits, moviemaking today is a much riskier, less profitable enterprise than it was in the studio system era. The massive budgets required for the global marketing of a film are huge financial gambles. In fact, most movies cost the studios much more to market and produce—upward of $100 million—than their box-office returns ever generate. With such high stakes, studios have come to rely on the handful of blockbuster films that keep them afloat (New World Encyclopedia), movies like Titanic, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Avatar (New World Encyclopedia). The blockbuster film becomes a touchstone, not only for production values and story lines, but also for moviegoers’ expectations. Because studios know they can rely on certain predictable elements to draw audiences, they tend to invest the majority of their budgets on movies that fit the blockbuster mold. Remakes, movies with sequel setups, or films based on best-selling novels or comic books are safer bets than original screenplays or movies with experimental or edgy themes.

James Cameron’s Titanic (1997), the second highest grossing movie of all time, saw such success largely because it was based on a well-known story, contained predictable plot elements, and was designed to appeal to the widest possible range of audience demographics with romance, action, expensive special effects, and an epic scope—meeting the blockbuster standard on several levels. The film’s astronomical $200 million production cost was a gamble indeed, requiring the backing of two studios, Paramount and 20th Century Fox (Hansen & Garcia-Meyers). However, the rash of high-budget, and high-grossing, films that have appeared since—Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and its sequels (2002–2011), Avatar (2009), Alice in Wonderland (2010), The Lord of the Rings films (2001–2003), The Dark Knight (2008), and others—are an indication that, for the time being, the blockbuster standard will drive Hollywood production.

The Role of Independent Films

While the blockbuster still drives the industry, the formulaic nature of most Hollywood films of the 1980s, 1990s, and into the 2000s has opened a door for independent films to make their mark on the industry. Audiences have welcomed movies like Fight Club (1999), Lost in Translation (2003), and Juno (2007) as a change from standard Hollywood blockbusters. Few independent films reached the mainstream audience during the 1980s, but a number of developments in that decade paved the way for their increased popularity in the coming years. The Sundance Film Festival (originally the U.S. Film Festival) began in Park City, Utah, in 1980 as a way for independent filmmakers to showcase their work. Since then, the festival has grown to garner more public attention, and now often represents an opportunity for independents to find market backing by larger studios. In 1989, Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape, released by Miramax, was the first independent to break out of the art-house circuit and find its way into the multiplexes.

In the 1990s and 2000s, independent directors like the Coen brothers, Wes Anderson, Sofia Coppola, and Quentin Tarantino made significant contributions to contemporary cinema. Tarantino’s 1994 film, Pulp Fiction, garnered attention for its experimental narrative structure, witty dialogue, and nonchalant approach to violence. It was the first independent film to break $100 million at the box office, proving that there is still room in the market for movies produced outside of the big six studios (Bergan, 2006).

The Role of Foreign Films

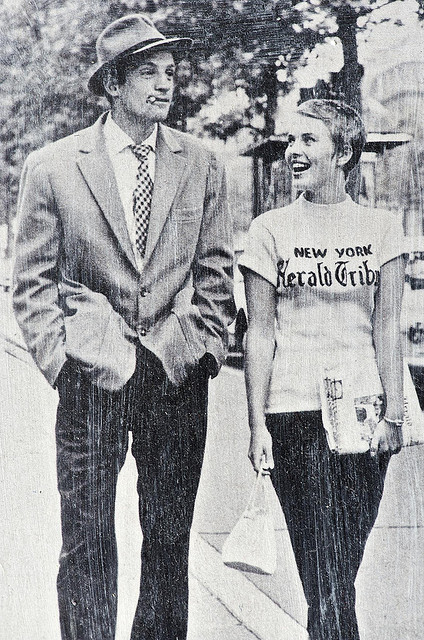

English-born Michael Apted, former president of the Director’s Guild of America, once said, “Europeans gave me the inspiration to make movies…but it was the Americans who showed me how to do it (Apted, 2007).” Major Hollywood studio films have dominated the movie industry worldwide since Hollywood’s golden age, yet American films have always been in a relationship of mutual influence with films from foreign markets. From the 1940s through the 1960s, for example, American filmmakers admired and were influenced by the work of overseas auteurs—directors like Ingmar Bergman (Sweden), Federico Fellini (Italy), François Truffaut (France), and Akira Kurosawa (Japan), whose personal, creative visions were reflected in their work (Pells, 2006). The concept of the auteur was particularly important in France in the late 1950s and early 1960s when French filmmaking underwent a rebirth in the form of the New Wave movement. The French New Wave was characterized by an independent production style that showcased the personal authorship of its young directors (Bergan). The influence of the New Wave was, and continues to be, felt in the United States. The generation of young, film school-educated directors that became prominent in American cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s owe a good deal of their stylistic techniques to the work of French New Wave directors.

In the current era of globalization, the influence of foreign films remains strong. The rapid growth of the entertainment industry in Asia, for instance, has led to an exchange of style and influence with U.S. cinema. Remakes of a number of popular Japanese horror films, including The Ring (2005), Dark Water (2005), and The Grudge (2004), have fared well in the United States, as have Chinese martial arts films like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Hero (2002), and House of Flying Daggers (2004). At the same time, U.S. studios have recently tried to expand into the growing Asian market by purchasing the rights to films from South Korea, Japan, and Hong Kong for remakes with Hollywood actors (Lee, 2005).

Cultural Imperialism or Globalization?

With the growth of Internet technology worldwide and the expansion of markets in rapidly developing countries, American films are increasingly finding their way into movie theaters and home DVD players around the world. In the eyes of many people, the problem is not the export of a U.S. product to outside markets, but the export of American culture that comes with that product. Just as films of the 1920s helped to shape a standardized, mass culture as moviegoers learned to imitate the dress and behavior of their favorite celebrities, contemporary film is now helping to form a mass culture on the global scale, as the youth of foreign nations acquire the American speech, tastes, and attitudes reflected in film (Gienow-Hecht, 2006).

Staunch critics, feeling helpless to stop the erosion of their national cultures, accuse the United States of cultural imperialism through flashy Hollywood movies and commercialism—that is, deliberate conquest of one culture by another to spread capitalism. At the same time, others argue that the worldwide impact of Hollywood films is an inevitable part of globalization, a process that erodes national borders, opening the way for a free flow of ideas between cultures (Gienow-Hecht, 2006).

The Economics of Movies

With control of over 95 percent of U.S. film production, the big six Hollywood studios—Warner Bros., Paramount, 20th Century Fox, Universal, Columbia, and Disney—are at the forefront of the American film industry, setting the standards for distribution, release, marketing, and production values. However, the high costs of moviemaking today are such that even successful studios must find moneymaking potential in crossover media—computer games, network TV rights, spin-off TV series, DVD and releases on Blu-ray Disc format, toys and other merchandise, books, and other after-market products—to help recoup their losses. The drive for aftermarket marketability in turn dictates the kinds of films studios are willing to invest in (Hansen & Garcia-Meyers).

Rising Costs and Big Budget Movies

In the days of the vertically integrated studio system, filmmaking was a streamlined process, neither as risky nor as expensive as it is today. When producers, directors, screenwriters, art directors, actors, cinematographers, and other technical staff were all under contract with one studio, turnaround time for the casting and production of a film was often as little as 3 to 4 months. Beginning in the 1970s, after the decline of the studio system, the production costs for films increased dramatically, forcing the studios to invest more of their budgets in marketing efforts that could generate presales—that is, sales of distribution rights for a film in different sectors before the movie’s release (Hansen & Garcia-Meyers). This is still true of filmmaking today. With contracts that must be negotiated with actors, directors, and screenwriters, and with extended production times, costs are exponentially higher than they were in the 1930s—when a film could be made for around $300,000 (Schaefer, 1999). By contrast, today’s average production budget, not including marketing expenses, is close to $65 million today (Nash Information Services).

Consider James Cameron’s Avatar, released in 2009, which cost close to $340 million, making it one of the most expensive films of all time. Where does such an astronomical budget go? When weighing the total costs of producing and releasing a film, about half of the money goes to advertising. In the case of Avatar, the film cost $190 million to make and around $150 million to market (Sherkat-Massoom, 2010; Keegan, 2009). Of that $190 million production budget, part goes toward above-the-line costs, those that are negotiated before filming begins, and part to below-the-line costs, those that are generally fixed. Above-the-line costs include screenplay rights; salaries for the writer, producer, director, and leading actors; and salaries for directors’, actors’, and producers’ assistants. Below-the-line costs include the salaries for nonstarring cast members and technical crew, use of technical equipment, travel, locations, studio rental, and catering (Tirelli). For Avatar, the reported $190 million doesn’t include money for research and development of 3-D filming and computer-modeling technologies required to put the film together. If these costs are factored in, the total movie budget may be closer to $500 million (Keegan). Fortunately for 20th Century Fox, Avatar made a profit over these expenses in box-office sales alone, raking in $750 million domestically (to make it the highest-grossing movie of all time) in the first 6 months after its release (Box Office Mojo, 2010). However, one thing you should keep in mind is that Avatar was released in both 2-D and 3-D. Because 3-D ticket prices are more expensive than traditional 2-D theaters, the box-office returns are inflated.

The Big Budget Flop

However, for every expensive film that has made out well at the box office, there are a handful of others that have tanked. Back in 1980, when United Artists (UA) was a major Hollywood studio, its epic western Heaven’s Gate cost nearly six times its original budget: $44 million instead of the proposed $7.6 million. The movie, which bombed at the box office, was the largest failure in film history at the time, losing at least $40 million, and forcing the studio to be bought out by MGM (Hall & Neale, 2010). Since then, Heaven’s Gate has become synonymous with commercial failure in the film industry (Dirks).

More recently, the 2005 movie Sahara lost $78 million, making it one of the biggest financial flops in film history. The film’s initial production budget of $80 million eventually doubled to $160 million, due to complications with filming in Morocco and to numerous problems with the script (Bunting, 2007).

Piracy

Movie piracy used to be perpetrated in two ways: Either someone snuck into a theater with a video camera, turning out blurred, wobbly, off-colored copies of the original film, or somebody close to the film leaked a private copy intended for reviewers. In the digital age, however, crystal-clear bootlegs of movies on DVD and the Internet are increasingly likely to appear illegally, posing a much greater threat to a film’s profitability. Even safeguard techniques like digital watermarks are frequently sidestepped by tech-savvy pirates (France, 2009).

In 2009, an unfinished copy of 20th Century Fox’s X-Men Origins: Wolverine appeared online 1 month before the movie’s release date in theaters. Within a week, more than 1 million people had downloaded the pirated film. Similar situations have occurred in recent years with other major movies, including The Hulk (2003) and Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005) (France, 2009). According to a 2006 study sponsored by the MPAA, Internet piracy and other methods of illegal copying cost major Hollywood studios $6.1 billion in the previous year (Hiestand, 2006). The findings of this report have since been called into question, with investigators claiming that there was no clear methodology for how researchers estimated those figures (Sandoval, 2010). Nonetheless, the ease of theft made possible by the digitization of film and improved file-sharing technologies like BitTorrent software, a peer-to-peer protocol for transferring large quantities of information between users, have put increased financial strain on the movie industry.

Key Takeaways

- A film’s performance at the box office is often directly related to the studio marketing budget that backs it.

- Because of high marketing and production costs, the major studios have increasingly come to rely on blockbuster films to keep themselves profitable.

- Independent films found increased popularity in the 1990s and 2000s, in part because they represented a break from the predictable material often released by studios.

- With the rise of digital filming technology and online movies, movie piracy has become an increasing concern for Hollywood.

Exercises

In Section 8.3 “Issues and Trends in Film”, you learned that blockbuster films rely on certain predictable elements to attract audiences. Think about recent blockbusters like Alice in Wonderland, Avatar, and Pirates of the Caribbean and consider the following:

- What elements do these films have in common? Why do you think these elements help to sell movies?

- How have the big Hollywood studios shaped these elements?

- How do economic concerns, like box-office totals, promote predictable elements?

- Have these movies been affected by piracy? If so, how? If not, why?

References

Apted, Michael. “Film’s New Anxiety of Influence,” Newsweek, December 28, 2007. http://www.newsweek.com/2007/12/27/film-s-new-anxiety-of-influence.html.

Belton, American Cinema/American Culture, 61–62.

Bergan, Film, 60.

Bergan, Ronald. Film (New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2006), 84.

Box Office Mojo, “Avatar,” May 31, 2010, http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=avatar.htm.

Bunting, Glenn F. “$78 Million of Red Ink?” Los Angeles Times, April 15, 2007, http://articles.latimes.com/2007/apr/15/business/fi-movie15/4.

Busis, Hillary. “How Do Movie Theaters Decide Which Trailers to Show?” Slate, April 15, 2010, http://www.slate.com/id/2246166/.

Dick, Kirby. interview, Fresh Air.

Dirks, “The History of Film: the 1980s.”

Epstein, Edward Jay. “Neither the Power nor the Glory: Why Hollywood Leaves Originality to the Indies,” Slate, October 17, 2005, http://www.slate.com/id/2128200.

France, Lisa Respers. “In Digital Age, Can Movie Piracy Be Stopped?” CNN, May 2, 2009, http://www.cnn.com/2009/TECH/05/01/wolverine.movie.piracy/.

Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E. “A European Considers the Influence of American Culture,” eJournal USA, February 1, 2006, http://www.america.gov/st/econenglish/2008/June/20080608094132xjyrreP0.2717859.html.

Hall, Sheldon and Stephen Neale, “Super Blockbusters: 1976–1985,” in Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History (Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press, 2010), 231.

Hansen and Garcia-Meyers, “Blockbusters,” 283.

Hiestand, Jesse. “MPAA Study: ’05 Piracy Cost $6.1 Bil.,” Hollywood Reporter, May 3, 2006. http://business.highbeam.com/2012/article-1G1-146544812/mpaa-study-05-piracy-cost-61-bil.

James, Caryn. “Critic’s Notebook: Romanticizing Hollywood’s Dream Factory,” New York Times, November 7, 1989, http://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/07/movies/critic-s-notebook-romanticizing-hollywood-s-dream-factory.html.

Keegan, “How Much Did Avatar Really Cost?”

Keegan, Rebecca. “How Much Did Avatar Really Cost?” Vanity Fair, December 2009, http://www.vanityfair.com/online/oscars/2009/12/how-much-did-avatar-really-cost.html.

Lee, Diana. “Hollywood’s Interest in Asian Films Leads to Globalization,” UniOrb.com, December 1, 2005, http://uniorb.com/ATREND/movie.htm.

Nash Information Services, “Glossary of Movie Business Terms,” The Numbers, http://www.the-numbers.com/glossary.php.

Nash Information Services, “The Million Dollar Hotel,” The Numbers: Box Office Data, Movie Stars, Idle Speculation, http://www.the-numbers.com/2001/BHOTL.php.

Nash Information Services, “What Women Want,” The Numbers: Box Office Data, Movie Stars, Idle Speculation, http://www.the-numbers.com/2000/WWWNT.php.

New World Encyclopedia, s.v. “Film Industry,” www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hollywood.

Pells, Richard. “Is American Culture ‘American’?” eJournal USA, February 1, 2006, http://www.america.gov/st/econ-english/2008/June/20080608102136xjyrreP0.3622858.html.

Powdermaker, Hortense. “Hollywood, the Dream Factory,” http://astro.temple.edu/~ruby/wava/powder/intro.html.

Sandoval, Greg. “Feds Hampered by Incomplete MPAA Piracy Data,” CNET News, April 19, 2010, http://news.cnet.com/8301-31001_3-20002837-261.html.

Schaefer, Eric. “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!”: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999), 50.

Sherkat-Massoom, Mojgan. “10 Most Expensive Movies Ever Made,” Access Hollywood, 2010, http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/34368822/ns/entertainment-access_hollywood/?pg=2#ENT_AH_MostExpensiveMovies.

Tirelli, Aldo-Vincenzo “Production Budget Breakdown: The Scoop on Film Financing,” Helium, http://www.helium.com/items/936661-production-budget-breakdown-the-scoop-on-film-financing.

Feedback/Errata