8 1.8 Media Literacy

Learning Objectives

- Define media literacy.

- Describe the role of individual responsibility and accountability when responding to pop culture.

- List the five key considerations about any media message.

In Gutenberg’s age and the subsequent modern era, literacy—the ability to read and write—was a concern not only of educators, but also of politicians, social reformers, and philosophers. A literate population, many reasoned, would be able to seek out information, stay informed about the news of the day, communicate effectively, and make informed decisions in many spheres of life. Because of this, literate people made better citizens, parents, and workers. Several centuries later, as global literacy rates continued to grow, there was a new sense that merely being able to read and write was not enough. In a media-saturated world, individuals needed to be able to sort through and analyze the information they were bombarded with every day. In the second half of the 20th century, the skill of being able to decode and process the messages and symbols transmitted via media was named media literacy. According to the nonprofit National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE), a person who is media literate can access, analyze, evaluate, and communicate information. Put another way by John Culkin, a pioneering advocate for media literacy education, “The new mass media—film, radio, TV—are new languages, their grammar as yet unknown (Moody, 1993).” Media literacy seeks to give media consumers the ability to understand this new language. The following are questions asked by those that are media literate:

- Who created the message?

- What are the author’s credentials?

- Why was the message created?

- Is the message trying to get me to act or think in a certain way?

- Is someone making money for creating this message?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How do I know this information is accurate?

Why Be Media Literate?

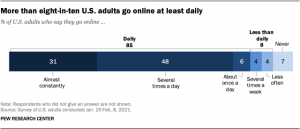

Culkin called the pervasiveness of media “the unnoticed fact of our present,” noting that media information was as omnipresent and easy to overlook as the air we breathe (and, he noted, “some would add that it is just as polluted”) (Moody, 1993). While parents are often worried about how much screen time is healthy for children and teens are criticized for spending too much time on screens, excessive screen time is a serious problem for people of all ages living in America. The COVID pandemic, with lockdowns and health concerns causing people to stay home and stay connected online, has caused these concerns to intensify. According to a Pew Research Center survey published in March 2021, 31% of U.S. adults now report that they go online “almost constantly,” up from 21% in 2015.

Of course, the numbers also shift depending on demographics of class, race, income, education level, and more.

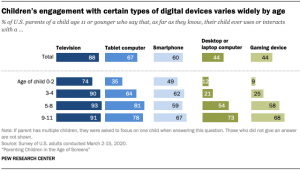

The Pew Research Center also looked into the different types of media young children are consuming, along with the time amount.

For teens, COVID also caused an increase in screen time. In a study published in November 2021 from JAMA, a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal published by the American Medical Association, the pandemic caused an increase of four hours per day in screen time for teens for a total of eight hours a day.

Media literacy isn’t merely a skill for young people, however. Today’s Americans get much of their information from various media sources—but not all that information is created equal. One crucial role of media literacy education is to enable us to skeptically examine the often-conflicting media messages we receive every day.

Advertising

Many of the hours people spend with media are with commercial-sponsored content. Advertising has evolved and expanded just as much as any other mass media subfield. Advertising went from a huge revenue source for newspapers and magazines in the 1800s and early 1900s, then added radio and TV sponsorships and commercials, as well as billboards and ads in public spaces. Today, advertisements remain in those venues, but also have expanded online and now companies’ advertising dollars are fueling tech giants like Google and Facebook. According to PPC Connect, a company that helps advertisers maximize their ads, “although there are no official figures, the average person is now estimated to encounter between 6,000 to 10,000 ads every single day.”

In the past, with fewer channels to communicate through, it was easier to measure ad exposure. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimated that each child aged 2 to 11 saw, on average, 25,629 television commercials in 2004 alone, or more than 10,700 minutes of ads. Each adult saw, on average, 52,469 ads, or about 15.5 days’ worth of television advertising (Holt, 2007). Children (and adults) are bombarded with contradictory messages—newspaper articles about the obesity epidemic run side by side with ads touting soda, candy, and fast food. The American Academy of Pediatrics maintains that advertising directed to children under 8 is “inherently deceptive” and exploitative because young children can’t tell the difference between programs and commercials (Shifrin, 2005). This crisis has only been amplified by YouTube’s young audiences and money-makers.

Advertising often uses techniques of psychological pressure to influence decision making. Ads may appeal to vanity, insecurity, prejudice, fear, or the desire for adventure. This is not always done to sell a product—antismoking public service announcements may rely on disgusting images of blackened lungs to shock viewers. Nonetheless, media literacy involves teaching people to be guarded consumers and to evaluate claims with a critical eye.

Bias, Spin, and Misinformation

Advertisements may have the explicit goal of selling a product or idea, but they’re not the only kind of media message with an agenda. A politician may hope to persuade potential voters that he has their best interests at heart. An ostensibly objective journalist may allow her political leanings to subtly slant her articles. Magazine writers might avoid criticizing companies that advertise heavily in their pages. News reporters may sensationalize stories to boost ratings—and advertising rates.

Mass-communication messages are created by individuals, and each individual has his or her own set of values, assumptions, and priorities. Accepting media messages at face value could lead to confusion because of all the contradictory information available. Media literacy involves educating people to look critically at these and other media messages and to sift through various messages and make sense of the conflicting information we face every day.

Media Literacy in a Confusing World

Authors

Disclosure statement: The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Misinformation, disinformation and hoaxes: What’s the difference? from TheConversation.com.

Sorting through the vast amount of information created and shared online is challenging, even for the experts.

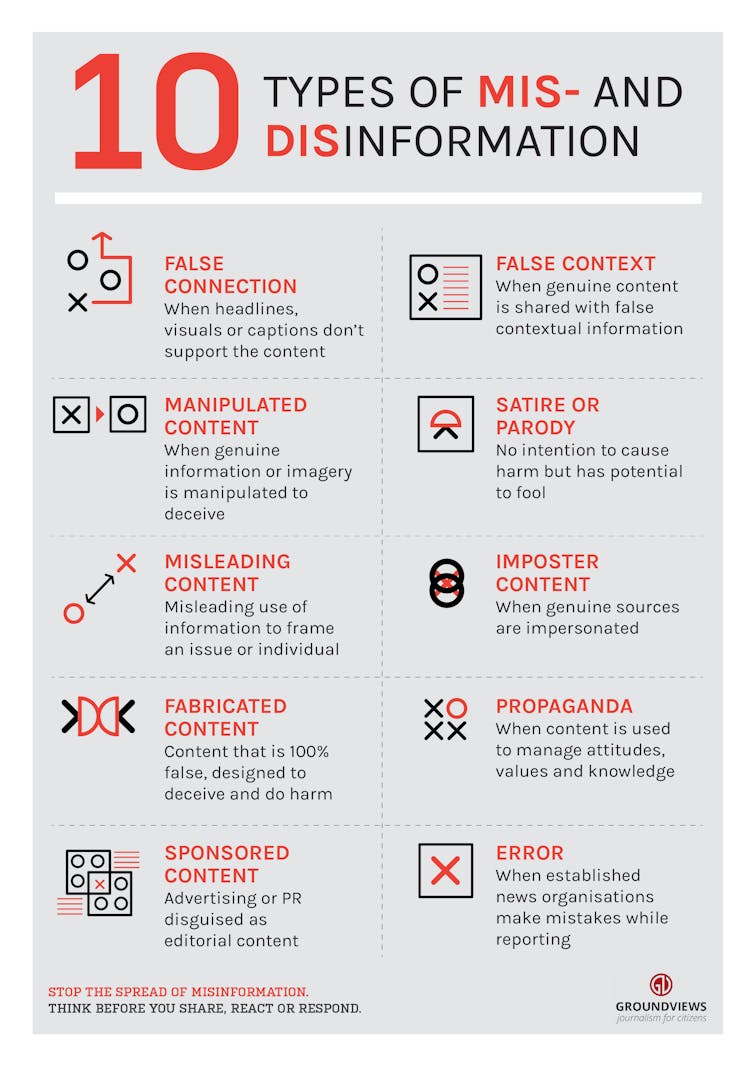

Just talking about this ever-shifting landscape is confusing, with terms like “misinformation,” “disinformation” and “hoax” getting mixed up with buzzwords like “fake news.”

Misinformation is perhaps the most innocent of the terms – it’s misleading information created or shared without the intent to manipulate people. An example would be sharing a rumor that a celebrity died, before finding out it’s false.

Disinformation, by contrast, refers to deliberate attempts to confuse or manipulate people with dishonest information. These campaigns, at times orchestrated by groups outside the U.S., such as the Internet Research Agency, a well-known Russian troll factory, can be coordinated across multiple social media accounts and may also use automated systems, called bots, to post and share information online. Disinformation can turn into misinformation when spread by unwitting readers who believe the material.

Hoaxes, similar to disinformation, are created to persuade people that things that are unsupported by facts are true. For example, the person responsible for the celebrity-death story has created a hoax.

Though many people are just paying attention to these problems now, they are not new – and they even date back to ancient Rome. Around 31 B.C., Octavian, a Roman military official, launched a smear campaign against his political enemy, Mark Antony. This effort used, as one writer put it, “short, sharp slogans written on coins in the style of archaic Tweets.” His campaign was built around the point that Antony was a soldier gone awry: a philanderer, a womanizer and a drunk not fit to hold office. It worked. Octavian, not Antony, became the first Roman emperor, taking the name Augustus Caesar.

The University of Missouri example

In the 21st century, new technology makes manipulation and fabrication of information simple. Social networks make it easy for uncritical readers to dramatically amplify falsehoods peddled by governments, populist politicians and dishonest businesses.

Our research focuses specifically on how certain types of disinformation can turn what might otherwise be normal developments in society into major disruptions.

One sobering example we’ve reviewed in detail is a situation you might remember: racial tensions at the University of Missouri in 2015, in the wake of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri. One of us, Michael O’Brien, was dean of the university’s College of Arts and Science at the time and saw firsthand the protests and their aftermath.

Black students at the university, just over 100 miles to the west of Ferguson, raised concerns about their safety, civil rights and racial equity in society and on campus. Unhappy with the university’s responses, they began to protest.

The incident that got the most national attention involved a white professor in the communication department pushing student journalists away from an area where Black students had congregated in the center of campus, yelling, “I need some muscle over here!” in an effort to keep reporters at bay.

Other events didn’t get as much national coverage, including a hunger strike by a Black student and the resignations of university leaders. But there was enough publicity about racial tensions for Russian information warriors to take notice.

Soon, the hashtag #PrayforMizzou, created by Russian hackers using the university’s nickname, began trending on Twitter, warning residents that the Ku Klux Klan was in town and had joined the local police to hunt down Black students. A photo surfaced on Facebook purporting to show a large white cross burning on the lawn of the university’s library.

A Twitter user claimed the police were marching with the KKK, tweeting: “They beat up my little brother! Watch out!” and a picture of a black child with a severely bruised face. This user was later found to be a Russian troll who went on to spread rumors about Syrian refugees.

These were a rich mix of different types of false information. The photos of the burning cross and the bruised child were hoaxes – the photos were legitimate, but their context was fabricated. A Google search for “bruised black child,” for example, revealed that it was a year-old picture from a disturbance in Ohio.

The rumor about the KKK on campus started as disinformation by Russian hackers and then spread as misinformation, even ensnaring the student-body president, a young Black man who posted a warning on Facebook. When it became clear the information was false, he deleted the post.

The fallout

Undoubtedly, not all of the fallout from the Mizzou protests was the direct result of disinformation and hoaxes. But the disruptions were factors in big changes in student numbers.

In the two years following the protests, the university saw a 35% drop in freshman enrollment and an overall enrollment drop of 14%. That caused campus university officials to cut about 12% – or US$55 million – from the university’s budget, including significant layoffs of faculty and staff. Even today, the campus is not yet back to what it was before the protests, financially, socially or politically.

The take-home message is clear: the world is a dangerous place, made all the more so by malevolent intent, especially in the online age. Learning to recognize misinformation, disinformation and hoaxes helps people stay better informed about what’s really happening.

Key Takeaways

- Media literacy, or the ability to decode and process media messages, is especially important in today’s media-saturated society. Media surrounds contemporary Americans to an unprecedented degree and from an early age. Because media messages are constructed with particular aims in mind, a media-literate individual will interpret them with a critical eye. Advertisements, bias, spin, and misinformation are all things to look for.

- Individual responsibility is crucial for media literacy because, while media messages may be produced by individuals, companies, governments, or organizations, they are always received and decoded by individuals.

- When analyzing media messages, consider the message’s author, format, audience, content, and purpose.

Exercises

List the considerations for evaluating media messages and then search the Internet for information on a current event. Choose one blog post, news article, or video about the topic and identify the author, format, audience, content, and purpose of your chosen subject. Then, respond to the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- How did your impression of the information change after answering the five questions? Do you think other questions need to be asked?

- Is it difficult or easy to practice media literacy on the Internet? What are a few ways you can practice media literacy for television or radio shows?

- Do you think the public has a responsibility to be media literate? Why or why not?

End-of-Chapter Assessment

Review Questions

-

Section 1

- What is the difference between mass communication and mass media?

- What are some ways that culture affects media?

- What are some ways that media affect culture?

-

Section 2

- List four roles that media plays in society.

- Identify historical events that have shaped the adoption of various mass-communication platforms.

- How have technological shifts affected the media over time?

-

Section 3

- What is convergence, and what are some examples of it in daily life?

- What were the five types of convergence identified by Jenkins?

- How are different kinds of convergence shaping the digital age on both an individual and a social level?

-

Section 4

- How does the value of free speech affect American culture and media?

- What are some of the limits placed on free speech, and how do they reflect social values?

- What is propaganda, and how does it reflect and/or impact social values?

- Who are gatekeepers, and how do they influence the media landscape?

-

Section 5

- What is a cultural period?

- How did events, technological advances, political changes, and philosophies help shape the Modern Era?

- What are some of the major differences between the modern and postmodern eras?

-

Section 6

- What is media literacy, and why is it relevant in today’s world?

- What is the role of the individual in interpreting media messages?

- What are the five considerations for evaluating media messages?

Critical Thinking Questions

- What does the history of media technology have to teach us about present-day America? How might current and emerging technologies change our cultural landscape in the near future?

- Are gatekeepers and tastemakers necessary for mass media? How is the Internet helping us to reimagine these roles?

- The idea of cultural periods presumes that changes in society and technology lead to dramatic shifts in the way people see the world. How have digital technology and the Internet changed how people interact with their environment and with each other? Are we changing to a new cultural period, or is contemporary life still a continuation of the Postmodern Age?

- U.S. law regulates free speech through laws on obscenity, copyright infringement, and other things. Why are some forms of expression protected while others aren’t? How do you think cultural values will change U.S. media law in the near future?

- Does media literacy education belong in U.S. schools? Why or why not? What might a media literacy curriculum look like?

Career Connection

In a media-saturated world, companies use consultants to help analyze and manage the interaction between their organizations and the media. Independent consultants develop projects, keep abreast of media trends, and provide advice based on industry reports. Or, as writer, speaker, and media consultant Merlin Mann put it, the “primary job is to stay curious about everything, identify the points where two forces might clash, then enthusiastically share what that might mean, as well as why you might care (Mann).”

Read the blog post “So what do consultants do?” at http://www.consulting-business.com/so-what-do-consultants-do.html.

Now, explore writer and editor Merlin Mann’s website (http://www.merlinmann.com). Be sure to take a look at the “Bio” and “FAQs” sections. These two pages will help you answer the following questions:

- Merlin Mann provides some work for free and charges a significant amount for other projects. What are some of the indications he gives in his biography about what he values? How do you think this impacts his fees?

- Check out Merlin Mann’s projects. What are some of the projects Merlin is or has been involved with? Now look at the “Speaking” page. Can you see a link between his projects and his role as a prominent writer, speaker, and consultant?

- Check out Merlin’s FAQ section. What is his attitude about social networking sites? What about public relations? Why do you think he holds these opinions?

- Think about niches in the Internet industry where a consultant might be helpful. Do you have expertise, theories, or reasonable advice that might make you a useful asset for a business or organization? Find an example of an organization or group with some media presence. If you were this group’s consultant, how would you recommend they better reach their goals?

References

Byers, Meredith “Controversy Over Use of Wikipedia in Academic Papers Arrives at Smith,” Smith College Sophian, News section, March 8, 2007.

Center for Media Literacy, “Five Key Questions Form Foundation for Media Inquiry,” http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/five-key-questions-form-foundation-media-inquiry.

Colbert, Stephen. “The Word: Wikiality,” The Colbert Report, July 31, 2006.

Fildes, Jonathan. “Wikipedia ‘Shows CIA Page Edits,’” BBC News, Science and Technology section, August 15, 2007.

Holt, Debra. and others, Children’s Exposure to TV Advertising in 1977 and 2004, Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Economics staff report, June 1, 2007.

Lewin. “If Your Kids Are Awake.”

Mann, Merlin. http://www.merlinmann.com/projects/.

Moody, Kate. “John Culkin, SJ: The Man Who Invented Media Literacy: 1928–1993,” Center for Media Literacy, http://www.medialit.org/reading_room/article408.html.

Robertson, Lori and Eugene Kiely, “Mudslinging in New Mexico: Gubernatorial Candidates Launch Willie Horton-Style Ads, Each Accusing the Other of Enabling Sex Offenders to Strike Again,” FactCheck.org, June 24, 2010, http://factcheck.org/2010/06/mudslinging-in-new-mexico/.

Shaw, David. “A Plea for Media Literacy in our Nation’s Schools,” Los Angeles Times, November 30, 2003.

Shifrin, Donald. “Perspectives on Marketing, Self-Regulation and Childhood Obesity” (remarks, Federal Trade Commission Workshop, Washington, DC, July 14–15, 2005).

Feedback/Errata