1.8: WHAT IS MEDICAL ANTHROPOLOGY?

Health and a preoccupation with maintaining it permeates all aspects of human culture. Health is a concern to humans everywhere. There is no end to the variety of ways cultures across history have treated health, healing, and medicine. Human health and well-being sit at the intersection of biology and culture. Both physical and social environments shape well-being and health outcomes. Medical anthropology is a holistic specialty that draws on all four fields of anthropology but primarily builds on cultural anthropology and biological anthropology to understand the health implications of a culture’s impact on human physiology and well-being.

Key Takeaways

- How do you define health?

- How do you maintain your health?

- What factors do you think contribute to health and illness?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define health, illness, sickness, and the sick role.

- Describe early research and methods in medical anthropology.

- Explain Franz Boas’s influence in establishing the foundations of medical anthropology.

- Describe how medical anthropology has developed since World War II.

Social Construction of Health

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization 2020). Health is affected by multiple social, biological, and environmental factors. Disease is strictly biological—an abnormality that affects an individual’s physical structure, chemistry, or function. Going back to the time of the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, doctors have regarded disease as the result of both a person’s lifestyle habits and the social environment in which they live. Illness, by comparison, is the individual’s sociocultural experience of a disruption to their physical or mental well-being. An individual’s perception of their own illness is shaped by how that illness is viewed, discussed, and explained by the society they live in. The social perception of another person’s sickness affects that person’s social well-being and how they are viewed and treated by others. Sick roles are the social expectations for a sick person’s behaviors based on their particular sickness—how they should act, how they should treat the sickness, and how others should treat them. Malady is the term anthropologists use to encompass disease, illness, and sickness.

- Health is your state of well-being.

- Disease is a biological abnormality.

- Illness is your sociocultural experience of health.

- Sickness is a social perception of ill health.

- Malady is a broad term for everything above.

Table 1. Key Terms Used in Medical Anthropology

| Term | Definition | Example |

| Health | State of well-being | Wellness prior to infection |

| Disease | A biological abnormality | Viral infection |

| Illness | A patient’s sociocultural experience of disrupted health | Fever, sore throat, cough, worry about missing class, disappointment of missing an outing with friends |

| Sickness | A social perception of ill health | Expectations such as: stay home and rest if you have a fever; do not attend class or go out with friends; see a doctor if it lasts longer than 48 hours |

| Malady | A broad term for everything above | Disruption of health caused by a viral infection with fever, sore throat, cough; worry about missing work/class; and the social expectation you will stay home and rest |

Foundational to medical anthropology is an understanding of health and malady that includes social experiences and cultural definitions. Medical anthropology studies how societies construct understandings of health and illness, including medical treatments for all types of maladies. Culture affects how we perceive everything, including health. Culture shapes how people think and believe and the values they hold. It shapes everything people have and do. Many cultures approach health and illness in completely different ways from one another, often informed by a number of societal factors. Medical anthropology provides a framework for common study and comparison between cultures, highlighting systems and illustrating how culture determines how health is perceived.

History of Medical Anthropology

While medical anthropology is a relatively new subfield, it has deep roots within four-field American anthropology, with a strong connection to early European anthropologists’ study of religion. The holistic approach of Franz Boas was also key to the development of medical anthropology. One focus of Boas’s research was analysis of the “race theory” common in the 19th and early 20th centuries in the United States. According to this theory, one’s assigned racial category and ethnic background determined certain physical features as well as behavioral characteristics. Boas challenged this assumption through studies of the health and physiology of immigrant families in New York City in 1912. Boas found that there was a great deal of flexibility in human biological characteristics within an ethnic group, with social factors such as nutrition and child-rearing practices playing a key role in determining human development and health. He noted that cultural changes to nutrition and child-rearing practices, changes that are commonly a part of the immigrant experience, were linked to generational changes in biology. Boas provided empirical data from his own primary sources that refuted theories of biological inheritance as the source of social behaviors and revealed the impact of local environments (natural, modified, and social) in structuring cultural and physical outcomes. This foundation was starkly opposed to the inherent racism of social evolutionism, which was the dominant anthropological theory of his time.

Boas’s students, such as Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Edward Sapir, all continued aspects of his work, taking their research in unique directions that affect medical anthropology to this day. Benedict’s cultural personality studies, Mead’s work on child-rearing practices and adolescence, and Sapir’s work on psychology and language laid the foundations of psychological anthropology. Their foray into psychological anthropology was preceded by the work of British psychiatrist and anthropologist W. H. R. Rivers (1901), who studied the inheritance of sensory capabilities and disabilities among Melanesian populations while participating in the Torres Strait island expedition in 1898. He developed a great respect for his Melanesian research participants and utilized his research findings to denounce the “noble savage” fallacy. By demonstrating that a shared biological mechanism of inheritance and environmental influences shaped the Melanesian senses in the same way as it did the British, he illustrated that their mental capacity was the same as Europeans.

Medical anthropology also has roots in the anthropology of religion, a subfield of anthropology that shines a lens on many aspects of health. The anthropology of religion looks at how humans develop and enact spiritual beliefs in their daily lives and at how these beliefs are utilized as a form of social control. A number of commonly studied key frameworks of the anthropology of religion—rituals of healing, taboos of health, shamanic healing, health beliefs, cultural symbolism, and stigma, among them—focus on health and health outcomes. A number of notable early religious anthropologists, including E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Victor and Edith Turner, and Mary Douglas, did work on subjects such as healing rituals, misfortune and harm, pollution, and taboo. Evans-Pritchard’s work among the Azande people of North Central Africa continues to be foundational to medical anthropology. Especially important is the chapter “The Notion of Witchcraft Explains Unfortunate Events” from the book Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande, which introduces the domain of causation and its many cross-cultural forms. This chapter directly impacted the concept of explanatory models, which we will cover in depth later in this chapter. The work of Victor and Edith Turner focused on ritual healing, pilgrimage, and socially enforced morality. Mary Douglas’s Purity and Danger ([1966] 2002) examined the concepts of pollution and taboo as well as rituals designed to restore purity. Her work continues to be influential, particularly for medical anthropologists focused on sickness-related stigma and its impact on patients’ illness experiences.

World War II brought about a profound change in the way anthropologists did their work. A number of Boas’s students helped the British and United States governments during the war, a trend that continued after the war. Focusing on both public and private health initiatives, anthropologists increasingly worked to help people improve their health outcomes in the post-war era. These public health efforts were directly connected with the founding of the United Nations and the World Health Organization (WHO). In this period, well-being and health care were included in the declaration of human rights, and biomedical thinking became focused on “conquering” infectious disease.

The formal founding of the discipline of medical anthropology can be traced to the late 1970s. One landmark is the publication of George Foster and Barbara Anderson’s (1978) medical anthropology textbook. However, many applied anthropologists and researchers in allied health fields, such as social epidemiology and public health, had been conducting cross-cultural health studies since the conclusion of World War II. These include Edward Wellin, Benjamin Paul, Erwin Ackerknecht, and John Cassell. Many of these early figures were themselves medical doctors who saw the limitations of a strictly biomechanical approach to health and disease.

PROFILES IN ANTHROPOLOGY

Paul Farmer, 1959–present, Jim Yong Kim, 1959–present

Personal Histories: Paul Farmer is a medical anthropologist and physician who first visited Haiti in 1983 as a volunteer. Inspired by this experience, Farmer set out to find a way to bring necessary treatments to parts of the world seemingly forgotten by modern medicine. When Harvard Medical School began offering a dual PhD/MD program, Farmer was among the first enrolled, and he soon founded Partners in Health (PIH) with his colleagues. Since then, he has championed affordable health care around the world. He is currently a professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, while still being actively involved in Partners in Health. Farmer has written extensively on the AIDS epidemic, infectious diseases, and health equity. In 2003, Farmer was the subject of Tracy Kidder’s book Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World, which is an accessible account of Farmer’s work with Partners in Health. Farmer is married to Didi Bertrand Farmer, a Haitian medical anthropologist. They have three children.

Like Farmer, Jim Yong Kim was one of the first to enroll in Harvard Medical dual medical anthropology PhD/MD program. He was a cofounder of Partners in Health while still in medical school, at a time when he was spending his summers in Haiti treating patients with limited access to health care. He championed the initial expansion of PIH into other countries, beginning with Peru. In 2003 Kim left Partners in Health to join the World Health Organization, becoming director of HIV/AIDs treatments and research in 2004. Under Kim, the WHO has fast-tracked a number of new treatments to help those affected by AIDS in Africa. Kim was the president of Dartmouth College from 2009 until 2012, when he became president of the World Bank. He held this position until 2019, when he left to join Global Infrastructure Partners.

Area of Anthropology: medical anthropology, applied anthropology

Accomplishments in the Field: Partners in Health was founded in 1987 by a group including Farmer and Kim, with the goal of setting up a clinic in Haiti to combat the devastation of the AIDS epidemic. Made up of volunteers, philanthropists, and medical students trained in anthropological methodology, the organization sought to combat the AIDS epidemic at a time when governments refused to adequately fund efforts to combat what was then perceived as a “gay disease.” By the mid-1990s, PIH was offering patients in Haiti treatments that cost hundreds of dollars, as opposed to the tens of thousands of dollars they would have cost in the United States. They have since duplicated this work in other settings, and their methods have been used by countless nonprofits around the world to offer life-saving treatments to impoverished communities.

Importance of Their Work: Partners in Health works today in 11 countries, with a staff of over 18,000 spread across the globe. They build hospitals, health clinics, and research labs aimed at improving medical treatment and creating a more equitable global health care system. Their model has been replicated by countless organizations around the world to bring down the cost of healthcare and increase the quality of the care given.

Since the 1980s, medical anthropologists have diversified the field through interdisciplinary applications of anthropology and the applied use of medical anthropology in health care and government policy. The role of the anthropologist in this work often varies but is typically focused on translating cultural nuance and biomedical knowledge into policy and human-centered care. Today, the field of medical anthropology includes applied anthropologists working in medical settings, nonprofits, and government entities such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the WHO. Academic medical anthropologists are problem-oriented researchers who study the complex relationship between human culture and health. As can be seen in the lives and careers of the medical anthropologists highlighted in this chapter’s profiles, medical anthropologists frequently occupy both academic and applied roles throughout their career as they seek to apply insights from their research to effect positive change in the lives of those they study.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define ethnomedicine, traditional environmental knowledge, and biomedicine.

- Provide examples of cultural and societal systems that use religion and faith to heal.

- Define medical pluralism.

Ethnomedicine is a society’s cultural knowledge about the management of health and treatments for illness, sickness, and disease. This includes the culturally appropriate process for seeking health care and the culturally defined signs and symptoms of illness that raise a health concern. Ethnomedical systems are frequently closely related to belief systems and religious practices. Healing can include rituals and natural treatments drawn from the local environment. Healing specialists in an ethnomedical system are knowledgeable individuals who undergo training or apprenticeship. Some examples of ethnomedical healers are midwives, doulas, herbalists, bonesetters, surgeons, and shamans, whose ethnomedicine existed in cultural traditions around the world prior to biomedicine. Anthropologists frequently note that ethnomedicinal healers possess knowledge of both how to heal and how to inflict harm by physical and sometimes metaphysical means. Ethnomedicine does not focus on “traditional” medicine, but instead allows for cross-cultural comparison of medical systems.

Some forms of healing rely upon spiritual knowledge as a form of medicine. Within shamanism, people deliberately enter the spirit world to treat ailments, with the culture’s shaman acting as an emissary. The goal may be to eliminate the illness or to at least identify its source. Similarly, faith healing relies upon a shared understanding of faith and local beliefs, with spirituality pervading the healing process. Exorcising individuals of possession by negative spirits is a common form of faith healing that occurs within Christian, Islamic, Buddhist, and shamanic frameworks. In many cases, cultures that utilize biomedicine also utilize some forms of faith healing.

Ethnopharmacology utilizes herbs, foods, and other natural substances to treat or heal illness. Traditional ethnopharmacological treatments are currently of great interest to pharmaceutical companies looking for new biomedical cures. Many common medicines have roots in ethnopharmacological traditions. Used in Chinese medicine, indigenous American healing, and traditional European medicine, willow bark is a widespread cure for headaches. In 1897, the chemist Dr. Felix Hoffmann, working for the Bayer corporation, isolated acetylsalicylic acid as the active pain-reducing ingredient in willow bark, giving the world Bayer aspirin.

The concept of traditional ecological knowledge, or TEK, refers to medical knowledge of different herbs, animals, and resources in an environment that provides a basis for ethnomedicine. Many cultures have been able to translate detailed awareness of their environments, such as where water is and where and when certain herbs grow, into complex and effective ethnomedical systems (Houde 2007). In 2006, Victoria Reyes-Garcia, working with others, conducted a comprehensive study of Amazonian TEK. Victoria and her colleagues collected information regarding plants useful for food and medicine from 650 research participants from villages along the Maniqui River in the Amazon River basin.

China’s traditional medicine system is another excellent example of an ethnomedical system that relies heavily on TEK and ethnopharmacology. While many in China do rely upon biomedicine to treat specific health problems, they also keep themselves in balance using traditional Chinese medicine. The decision of which health system to consult is often left to the patient, but at times doctors will suggest a patient visit a traditional apothecary and vice versa, creating a complementary medical system that makes use of both approaches. While bound by geography prior to the 19th century, in today’s globalized world a traditional Chinese doctor can use resources from anywhere around the world, whether it is dried body parts of a tiger or herbs found in another part of China. Chinese traditional medicine, as an ethnomedical system, is heavily influenced by culture and context. It focuses on balancing the body, utilizing a number of forces from the natural world. Traditional Chinese medicine makes use of substances as diverse as cicada shells, tiger livers, dinosaur bones, and ginseng to create medicine. Healers in this system are often in a role similar to Western pharmacists, concocting medicine in a variety of forms such as pills, tonics, and balms. The differences between a traditional Chinese medication healer and biomedical pharmacist include both the tools and ingredients used and the foundational assumptions about the cause of and treatments for various ailments. Around the world, traditional environmental knowledge is used both in place of biomedicine and alongside it.

Biomedicine is an ethnomedical system deeply shaped by European and North American history and rooted in the cultural system of Western science. It draws heavily from biology and biochemistry. Biomedicine treats disease and injuries with scientifically tested cures. Biomedical health care professionals base their assessment of the validity of a treatment on the results of clinical trials, conducted following the principles of the scientific method. It should be noted that as each health care professional is not conducting their own research, but instead relying on the work of others, this assessment still requires faith. Biomedicine places its faith in the scientific method, where other ethnomedical systems place their faith in a deity, the healer’s power, or time-tested treatments passed down in traditional ecological knowledge. Biomedicine is not free from culture; it is an ethnomedical system shaped by Western cultural values and history. Biomedicine falls short of its ideal of scientific objectivity. Medical anthropologists have extensively documented the way systemic prejudices such as racism, classism, and sexism permeate biomedicine, impacting its effectiveness and perpetuating health inequalities. Still, in the Western world, biomedicine is often utilized as a point of comparison for other ethnomedical systems.

Biomedicine has been critiqued by medical anthropologists for assuming predominance over other forms of healing and cultural knowledge. In many contexts, biomedicine is presumed to be superior because it is clinical and based on scientific knowledge. Yet this presumed superiority requires that a patient trusts and believes in science and the biomedical system. If a person mistrusts biomedicine, whether because of a bad experience with the biomedical model or a preference for another ethnomedical approach, their health outcomes will suffer if they are forced to rely on the biomedical system. Biomedicine can also disrupt and threaten culturally established treatments and cures. For example, in a culture that treats schizophrenia by granting a person spiritual power and treating them as part of the community, labeling that individual as mentally ill according to biomedical terms takes away their power and removes their agency. In most cases, a hybrid model, in which biomedicine does not assume supremacy but instead works alongside and supports ethnomedicine, is the most effective approach. A hybrid model accords the ill the ability to choose those treatments that they think will best help.

Medical pluralism occurs when competing ethnomedical traditions coexist and form distinct health subcultures with unique beliefs, practices, and organizations. In many contemporary societies, ethnomedical systems coexist with and frequently incorporate biomedicine. Biomedicine is privileged as the dominant health care system in the United States, but in many metropolitan areas, people can also consult practitioners of Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, homeopathic medicine, chiropractic medicine, and other ethnomedicinal systems from around the world. Examples of medical pluralism are fairly common in contemporary Western society: yoga as a treatment for stress and as a form of physical and mental therapy, essential oils derived from traditional medicine to enhance health, and countless others. Contemporary cultures often fuse biomedicine and ethnomedicine rather than just choosing one or the other. However, the privilege and medical authority of biomedicine does not always afford people the right to choose, or may give them only a limited capacity to do so. Anne Fadiman’s (1998) The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, which explores the conflicts between a small hospital in California and the parents of a Hmong child with epilepsy over the child’s care, is a classic example of the cultural conflicts that can occur in medically pluralistic societies.

In many parts of the world, biomedicine has accompanied colonialization, and indigenous health practices have been suppressed in favor of biomedicine. Juliet McMullin’s (2010) Healthy Ancestor: Embodied Inequality and the Revitalization of Native Hawaiian Health discusses the suppression of Hawaii’s indigenous ethnomedical system as a long-lasting legacy of its colonial history. The book includes the efforts of contemporary Hawaiians to regain the healthy lifestyle of their precolonial ancestors. McMullin concludes that while contemporary biomedical health care professionals are more open to Hawaii’s ethnomedical practices than their predecessors were, there is still work to be done.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Discuss the importance of cross-cultural comparison and cultural relativism in study of human health.

- Explain why both objectivity and subjectivity are needed in the study of health.

- Discuss ethnographic research methods and their specific applications to the study of human health.

- Summarize the theoretical frameworks that guide medical anthropologists.

The Importance of Cultural Context

Culture is at the center of all human perspectives and shapes all that humans do. Cultural relativism is crucial to medical anthropology. There is a great degree of variety in the symptoms and conditions that cultures note as significant indicators of diminished health. How the sick are treated varies between cultures as well, including the types of treatments prescribed for a particular sickness. Cultural context matters, and health outcomes determined by culture are informed by that culture’s many parts. The United States, for example, relies heavily on biomedicine, treating symptoms of mental and physical illness with medication. This prevalence is not merely an economic, social, or scientific consideration, but all three. A cultural group’s political-economic context and its cultural beliefs, traditions, and values all create the broader context in which a health system exists and all impact individuals on a psychosocial level. Behaviors such as dietary choices and preferences, substance use, and activity level—frequently labeled as lifestyle risk factors—are all heavily influenced by culture and political-economic forces.

While Western cultures rely upon biomedicine, others favor ethnopharmacology and/or ritual healing. Medical anthropologists must attempt to observe and evaluate ethnomedical systems without a bias toward biomedicine. Medical anthropologists must be cautious of tendencies toward ethnocentrism. Ethnocentrism in medical anthropology takes the form of using the health system of one’s own culture as a point of comparison, giving it preference when analyzing and evaluating other systems. An American anthropologist who studies ethnomedicine in the Amazon River basin must be careful to limit their bias toward a biomedical approach as much as they can. That is not to say that subjective experience and opinion need be discarded entirely, merely that bias should be acknowledged and where necessary limited. Admitting bias is the first step in combating it. Being aware of one’s own ethnocentrism allows an anthropologist to analyze culture and medicine more truthfully.

Methods of Medical Anthropology

Medical anthropology is a highly intersectional subfield of anthropology. The field addresses both the biological and social dimensions of maladies and their treatments. Medical anthropologists must thus become comfortable with a wide-ranging tool kit, as diverse as health itself. Like all anthropologists, medical anthropologists rely on qualitative methods, such as ethnographic fieldwork, but they also must be able to appropriately use quantitative methods such as biometrics (including blood pressure, glucose levels, nutritional deficiencies, hormone levels, etc.) and medical statistics (such as rates of comorbidities, birth rates, mortality rates, and hospital readmission rates). Medical anthropologists can be found working in a myriad of endeavors: aiding public health initiatives, working in clinical settings, influencing health care policy, tracking the spread of a disease, or working for companies that develop medical technologies. The theories and methods of medical anthropology are invaluable to such endeavors.

Qualitative Methods

Within medical anthropology, a number of qualitative research methods are invaluable tools. Qualitative methods are hands-on, first-person approaches to research. An anthropologist in the room or on the ground writing down field notes based on what they see and recording events as they happen creates valuable data for themselves and for others.

Participant observation is a methodology in which the anthropologist makes first-person observations while participating in a culture. In medical anthropology, participant observation can take many forms. Anthropologists observe and participate in clinical interactions, shamanic rituals, public health initiatives, and faith healing. A form of participant observation, clinical observations allow the anthropologist to see a culture’s healing practices at work. Whether a doctor is treating COVID-19 or a shaman is treating a case of soul loss, the anthropologist observes the dynamics of the treatment and in some cases actually participates as a patient or healer’s apprentice. This extremely hands-on method gives the anthropologist in-depth firsthand experience with a culture’s health system but also poses a risk of inviting personal bias.

Anthropologists observe a myriad of topics, from clinical interactions to shamanic rituals, public health initiatives to faith healing. They carry these firsthand observations with them into their interviews, where they inform the questions they ask. In medical anthropology, interviews can take many forms, from informal chats to highly structured conversations. An example of a highly structured interview is an illness narrative interview. Illness narrative interviews are discussions of a person’s illness that are recorded by anthropologists. These interviews can be remarkably diverse: they can involve formal interviews or informal questioning and can be recorded, written down, or take place electronically via telephone or video conference call. The social construction of sickness and its impact on an individual’s illness experience is deeply personal. Illness narratives almost always focus on the person who is ill but can at times involve their caregivers, family, and immediate network as well.

Another method commonly used in medical anthropology, health decision-making analysis, looks at the choices and considerations that go into deciding how to treat health issues. The anthropologist interviews the decision makers and creates a treatment decision tree, allowing for analysis of the decisions that determine what actions to take. These decisions can come from both the patient and the person providing the treatment. What religious or spiritual choices might make a person opt out of a procedure? What economic issues might they face at different parts of their illness or sickness? Health decision-making analysis is a useful tool for looking at how cultures treat sickness and health, and it highlights a culture’s economic hierarchies, spiritual beliefs, material realities, and social considerations such as caste and gender.

Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods produce numeric data that can be counted, correlated, and evaluated for statistical significance. Anthropologists utilize census data, medical research data, and social statistics. They conduct quantitative surveys, social network analysis that quantifies social relationships, and analysis of biomarkers. Analysis of census data is an easy way for medical anthropologists to understand the demographics of the population they are studying, including birth and death rates. Census data can be broken down to analyze culturally specific demographics, such as ethnicity, religion, and other qualifiers as recorded by the census takers. At times, an anthropologist may have to record this data themselves if the available data is absent or insufficient. This type of analysis is often done as a kind of background research on the group being studying, creating a broader context for more specific analysis to follow.

Also important to medical anthropologists are analyses of medical statistics. The study of medical records helps researchers understand who is getting treated for what sickness, determine the efficacy of specific treatments, and observe complications that arise with statistical significance, among other considerations. Analysis of census data combined with medical statistics allows doctors and other health providers, as well as medical anthropologists, to study a population and apply that data toward policy solutions. Famous examples include the World Health Organization’s work on health crises such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and COVID-19.

Questionnaires are more personal to the anthropologist, allowing them to ask pointed questions pertinent to their particular research. Surveys make it possible for anthropologists to gather a large quantity of data that can then be used to inform the questions they ask using qualitative methods. Distribution methods for surveys vary and including means such as personally asking the questions, releasing the survey through a healthcare provider, or offering online surveys that participants choose to answer.

These are the most common methods used by medical anthropologists. Different theories are influential in determining which of the methods a particular research might favor. These theories inform how an anthropologist might interpret their data, how they might compose a study from beginning to end, and how they interact with the people they study. Combined with more general anthropological theory, each anthropologist must craft a composite of theory and method to create their own personalized study of the world of human health.

Theoretical Approaches to Medical Anthropology

Social Health

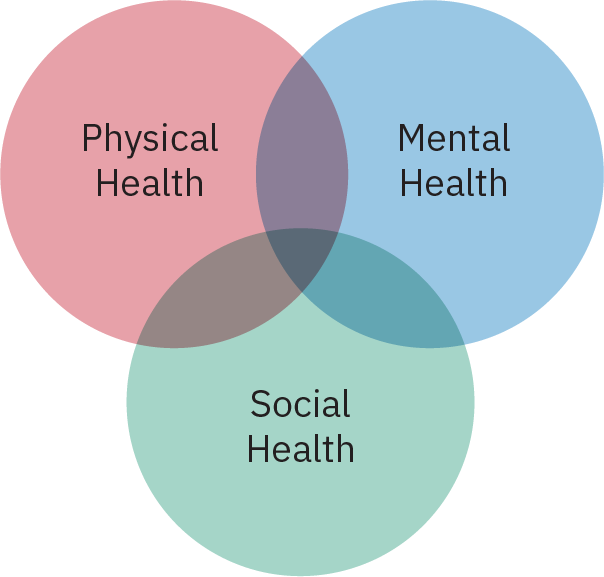

Biomedicine, the science-based ethnomedical system practiced in the United States, recognizes the impact physical health and mental health have on one another: when one falters, the other does as well. There is an increasing awareness in biomedicine of a third type of health, social health, which has long been recognized by many ethnomedical systems around the world. Each of the theoretical approaches to medical anthropology demonstrates that to develop a holistic understanding of human well-being, it is necessary to include mental, physical, and social health. Social health is driven by a complex set of sociocultural factors that impact an individual or community’s wellness. At a macro level, it includes the cultural and political-economic forces shaping the health of individuals and communities. An individual’s social health also includes the support a person receives from their extended social network, as well as the social pressures or stigma a person may face and the meaning that they ascribe to their experiences. Just as mental and physical health strongly influence one another, when a person’s social health falters, their physical and/or mental health declines as well.

Physical environments—whether they are natural, constructed, or modified environments—shape cultural adaptations and behaviors. People living on islands and people living in deserts inhabit very different environments that inform their cultures and affect their biology. On the other hand, culture often affects how humans interact with their environments. People who work in offices in Los Angeles and hunter-gatherers in the Amazon River basin interact with their environments differently, relying upon very different subsistence patterns and sets of material culture. Culture also informs human biology. Eating a lot of spicy foods changes a person’s biophysiology and health outcomes, as do dietary taboos such as refusing to eat pork. These dietary choices inform biology over generations as well as within a single lifetime.

The Biocultural Approach

The biocultural approach to anthropology acknowledges the links between culture and biology. Biology has informed human development and evolution, including the adaptations that have made culture, language, and social living possible. Culture, in turn, informs choices that can affect our biology. The biocultural approach analyzes the interaction between culture, biology, and health. It focuses on how the environment affects us, and the connections between biological adaptations and sociocultural ones. The biocultural approach draws on biometric and ethnographic data to understand how culture impacts health. The effects of environment on biology and culture are apparent in the treatment of survivors of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident that occurred in 2011 in Japan. Studies regarding the genetic health of survivors focus on the combination of environmental damage and social stigma in Japan due to their potential exposure to radiation.

Symbolic Approach

Other theoretical approaches ask different types of questions. What does it mean to be a patient? What are the social expectations for the behaviors of a person diagnosed as suffering from a particular sickness? Why is it symbolically meaningful for a treatment to be prescribed by a medical doctor? These are questions typically asked by those utilizing a symbolic approach to medical anthropology. The symbolic approach focuses on the symbolic thinking and beliefs of a culture and how those beliefs affect social and especially health outcomes.

A person’s beliefs affect how they perceive treatments and how they experience illness. The most obvious example of the symbolic approach at work is the placebo effect. If a person believes that a treatment will be effective, this belief will affect their health outcome. Often in medical trials, people who believe they are receiving a treatment but are in fact receiving a placebo, such as a sugar pill, will demonstrate physiological responses similar to those receiving an active substance. Accounting for the placebo effect is an important consideration for all medical studies. The opposite of the placebo effect, the nocebo effect, occurs when a person believes they are not receiving an effective medicine or that a treatment is harmful. Common to both phenomena is the importance of meaning-centered responses to health outcomes. One of the most potent examples of this is voodoo death, when psychosomatic effects—that is, physical effects created by social, cultural, and behavioral factors—such as fear brought on by culture and environment cause sudden death. Related to the symbolic approach of medical anthropology is the symbolic interaction approach to health utilized by medical sociologists. Both approaches recognize that health and illness are socially constructed concepts. The symbolic interaction approach to health focuses on the roles of the patient, caregiver, and health care provider and the interactions that take place between people occupying these roles.

Medical Ecology

Another major medical anthropology theory is medical ecology. Pioneered by Paul Baker and based on his work in the Andes and American Samoa in the 1960s and 1970s, medical ecology is a multidisciplinary approach that studies the effects of environment on health outcomes. Examples of these environmental influences include food sources, environmental disasters and damage, and how environmentally informed lifestyles affect health. Whereas the biocultural approach looks at the intersection of biology and culture, medical ecology focuses instead on how environment informs both health and the culture surrounding it.

A popular example of these connections can be observed in what are termed Blue Zones, certain locations around the world where a significant number of people regularly live exceptionally long lives, many over a century. These communities can be found in the United States, Japan, Columbia, Italy, and Greece. Common links between people who live in these places include a high-vegetable, low-animal-product diet (eggs and fish are the exception), a lively social life and regular activity, and a strong sense of cultural identity.

A negative example of the links between environment and health can be viewed in the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. In this case, pollution of the city water system negatively affected health outcomes due to high exposure to lead and Legionnaires’ disease. Studies, including a long-term study by the National Institutes of Health, confirm that the water, central to the larger environment of Flint, negatively affected citizens of all ages, with particular harm caused to children and the elderly.

Cultural Systems Model

Culture is a chief consideration in another theory, the cultural systems model. Cross-cultural comparison is a core methodology for anthropology at large, and the cultural systems model is ideal for cross-cultural comparison of health systems and health outcomes. Cultures are made of various systems, which are informed by sociocultural, political-economic, and historical considerations. These systems can include health care systems, religious institutions and spiritual entities, economic organizations, and political and cultural groupings, among many others. Different cultures prioritize different systems and place greater or less value on different aspects of their culture and society. The cultural systems model analyzes the ways in which different cultures give preference to certain types of medical knowledge over others. And, using the cultural systems model, different cultures can be compared to one another.

An example of the cultural systems model at work is Tsipy Ivry’s Embodying Culture: Pregnancy in Japan and Israel (2009), which examines pregnancy and birth in Israel and Japan. A particular focus is how state-controlled regulation of pregnancy and cultural attitudes about pregnancy affect women differently in each society. Despite both societies having socialized medicine, each prioritizes the treatment of pregnant women and the infant differently.

In the Israeli cultural model for pregnancy, life begins at a child’s first breath, which is when a woman becomes a mother. Ivry describes a cultural model that is deeply impacted by anxiety regarding fetal medical conditions that are deemed outside the mother’s and doctor’s control. As every pregnancy is treated as high risk, personhood and attachment are delayed until birth. The state of Israel is concerned with creating a safe and healthy gene pool and seeks to eliminate genes that may be harmful to offspring; thus, the national health care system pressures women to undergo extensive diagnostic testing and terminate pregnancies that pass on genes that are linked to disorders like Tay-Sachs disease.

Japan, facing decreasing birthrates, pressures women to maximize health outcomes and forgo their own desires for the sake of the national birth rate. The cultural model for pregnancy in Japan emphasizes the importance of the mother’s body as a fetal environment. From conception, it is a mother’s responsibility to create a perfect environment for her child to grow. Mothers closely monitor their bodies, food intake, weight gain, and stressful interactions. In Japan, working during pregnancy is strongly discouraged. Ivry noted that many women even quit work in preparation for becoming pregnant, whereas in Israel mothers work right up to delivery.

The cultural systems model also allows medical anthropologists to study how medical systems evolve when they come into contact with different cultures. An examination of the treatment of mental illness is a good way of highlighting this. While in the United States mental illness is treated with clinical therapy and pharmaceutical drugs, other countries treat mental illness differently. In Thailand, schizophrenia and gender dysmorphia are understood in the framework of culture. Instead of stigmatizing these conditions as illnesses, they are understood as gifts that serve much-needed roles in society. Conversely, in Japan, where psychological diagnoses have become mainstream in the last few decades and pharmaceutical treatment is more prominent than it once was, psychological treatment is stigmatized. Junko Kitanaka’s work on depression in Japan highlights how people with depression are expected to suffer privately and in silence. She links this socially enforced silence to Japan’s high stress rates and high suicide rates (2015). The cultural systems model offers an effective way to evaluate these three approaches toward mental illness, giving a basis of comparison between the United States, Thailand, and Japan. Assigning ethnomedicine the same value as biomedicine rather than giving one primacy over the other, this important comparative model is central to the theoretical outlook of many medical anthropologists.

The cultural systems model encompasses a myriad of cross-disciplinary techniques and theories. In many cultures, certain phrases, actions, or displays, such as clothing or amulets, are recognized as communicating a level of distress to the larger community. Examples include the practices of hanging “the evil eye” in Greece and tying a yellow ribbon around an oak tree during World War II in the United States. These practices are termed idioms of distress, indirect ways of expressing distress within a certain cultural context. A more psychologically driven consideration is the cause of people’s behaviors, known as causal attributions. Causal attributions focus on both personal and situational causes of unexpected behaviors. A causal attribution for unusual behavior such as wandering the streets haplessly could be spirit possession within the context of Haitian Vodou, while in the United States behaviors such as sneezing and blowing one’s nose might be attributed to someone not taking care of themselves.

Causal attributions can be important to one’s own illness. Anthropologist and psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman has concluded that if doctors and caregivers were to ask their patients what they think is wrong with them, these explanations might provide valuable information on treatment decisions. One patient might think that their epilepsy is caused by a spirit possession. Another might suggest that their developing diabetes in inevitable because of their culture and diet. These beliefs and explanations can guide a doctor to develop effective and appropriate treatments. The approach recommended by Kleinman is known as the explanatory model. The explanatory model encourages health care providers to ask probing questions of the patient to better understand their culture, their worldview, and their understanding of their own health.

Political Economic Medical Anthropology

Another medical anthropology approach is critical medical anthropology (CMA), which is sometimes referred to as political economic medical anthropology (PEMA). Critical medical anthropology has a specific interest in the inequalities of health outcomes caused by political and economic hierarchies. Critical medical anthropology advocates for community involvement and health care advocacy as ethical obligations. Defining biomedicine as capitalist medicine, this approach is critical of the social conditions that cause disease and health inequalities and of biomedicine’s role in perpetuating these systemic inequalities. CMA is also interested in the medicalization of social distress, a process that has led to a wide range of social problems and life circumstances being treated as medical problems under the purview of biomedicine.

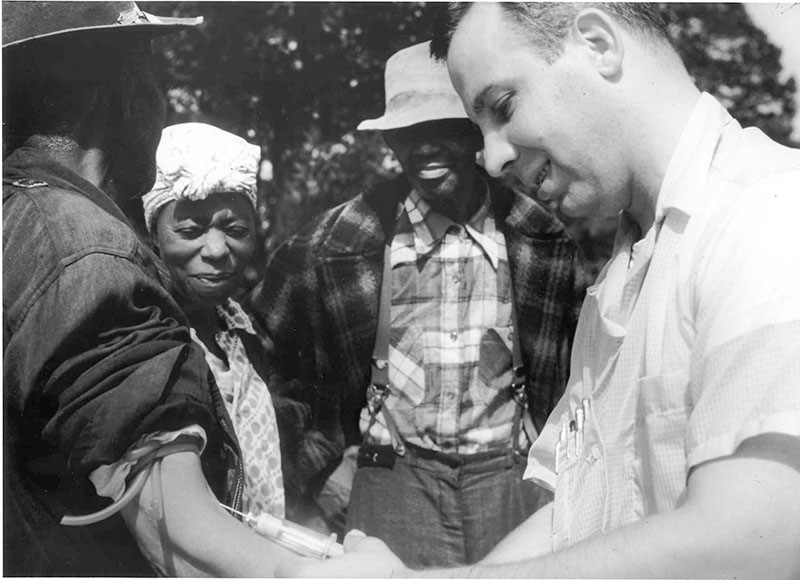

Systemic racism and structural violence create many negative health outcomes. Structural violence refers to the way in which social institutions, intentionally or otherwise, harm members of some groups within the larger society. Structural violence can affect things such as life expectancy, disability, or pregnancy outcomes and can lead to distrust of medical systems. The Tuskegee syphilis study, a decades-long “experiment” that studied the long-term effects of syphilis in Black men under the guise of medical treatment, is a prime example of structural violence at work within the United States medical system. Black men involved in the study were not told they had syphilis and were denied medical treatment for decades, with most dying of the disease. The government’s internal mechanisms for halting unethical studies failed to stop this experiment. It was only when public awareness of what was happening resulted in an outcry against the study that the experiments were stopped.

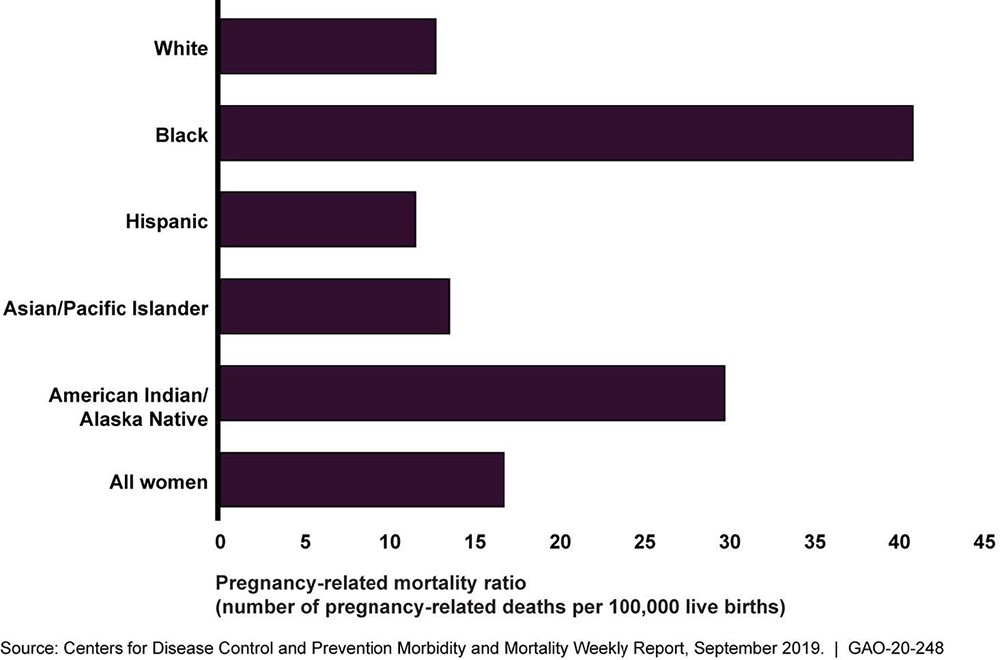

Another area of interest to medical anthropologists working with a CMA approach is how medical systems might be inherently biased toward or against certain segments of society. The research of anthropologist Leith Mullings demonstrated a lifelong focus on structures of inequality and resistance. Her work in Ghana examined traditional medicine and religious practice through a postcolonial lens, which was critical of the colonial legacy of structural inequality she observed. Her work in the United States also focused on health inequalities, with a special interest in the intersection of race, class, and gender for Black women in urban areas. It has been documented that some doctors in the United States regularly ignore the pain of women, and this is especially true in cases where the doctor displays racial bias. This tendency has been cited in several studies, including a study in The New England Journal of Medicine that found that women are more likely to be misdiagnosed for coronary heart disease based on the symptoms they give and pain levels reported (Nubel 2000). Another study in the Journal of Pain found that women on average reported pain 20 percent more of the time than men and at a higher intensity (Ruau et al. 2012). Another example of research that takes a CMA approach is Khiara Bridges’s 2011 Reproducing Race, which brings a critical lens to pregnancy as a site of racialization through her ethnography of a large New York City hospital. This medical racism contributes to the higher rates of African American infant and maternal mortality.

Merrill Singer has done work on the role of social inequalities in drug addiction and in cycles of violence. This work has led to his development of the concept of sydnemics, the social intersection of health comorbidities, or two health conditions that often occur together. For example, Japan’s hibakusha, or atomic bomb survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, do not live as long as Japan’s normally long-lived population and are more likely to develop multiple types of cancer and other diseases tied to their exposure to nuclear radiation. In addition to these health risks, they face heavy discrimination from the larger Japanese population due to misinformation regarding nuclear radiation and radiation contamination. This discrimination carries over to the descendants of hibakusha, who have a higher rate of cancer than the average Japanese population despite having no detectable genetic damage from the atomic bombings. Studies are ongoing as to the cultural, economic, and genetic causes of this cancer. Syndemics is highlighted in the near-century-long struggle for numerous conditions caused by the atomic bombings to be recognized as related to the atomic bombings and thus treated by the Japanese government.

Critical theories of health are an applied method, analyzing medical systems and applying critical theory, often with the goal of improving the system or improving policy. Recommendations for improvements often come out of research but may also be the starting point of a research project, as part of a data-finding mission to highlight disparity in health outcomes. Whether it is systemic racism in biomedical treatment or power discrepancies in ethnomedical rituals, critical theories of health are a key part of exploring medicine in action and understanding real medical consequences. From birth to the grave, social inequalities shape health outcomes, life expectancy, and unnecessary human suffering. Critical medical anthropology scholarship demonstrates the social forces shaping disease and health, from drug addiction to the impacts of climate change. This work becomes a self-evident call of action. It is medical anthropology in action.

PROFILES IN ANTHROPOLOGY

Angela Garcia 1971-

Personal History: Angela Garcia comes from a small town along the Mexican border with New Mexico. She credits her background and upbringing with inspiring much of her later work in anthropology. Her early experiences have led her to focus on places where political and cultural spheres combine, resulting in inequality and violence. Within this framework, she has focused on medicine, postcolonial theory, and feminism. She first attended the University of California, Berkeley, and then earned a PhD from Harvard University in 2007, shortly thereafter publishing her first book, The Pastoral Clinic: Addiction and Dispossession along the Rio Grande.

Area of Anthropology: medical anthropology, feminist anthropology

Accomplishments in the Field: The Pastoral Clinic analyzes heroin addiction among Hispanic populations in New Mexico’s Rio Grande region. Garcia’s work focuses on the political and social realities that contribute to addiction and treatment, with dispossession as a central theme. The degradation of the surrounding environment and the economic decline of the Great Recession have been important factors in determining people’s life choices. Also influential has been a political reality that denies many participation or power. Garcia describes addiction as a recurring reality in the lives of many, leading them in and out of rehab in an endless cycle. Garcia also describes the damaging effects of addiction on relationships within families and communities.

Garcia joined the Department of Anthropology at Stanford University in 2016. Her work has shifted to Mexico City, where she studies coercive rehabilitation centers run by the poor. She is particularly interested in political and criminal violence and in how informal centers like these exemplify the political and social climate within the larger Mexican nation. As much as these centers embody these realities, they also try to shift power away from pathways that lead to and encourage violence. In addition to this work, Garcia has also started examining addiction and mental illness in both Mexico and the United States Latinx (Latina/o) population.

Importance of Their Work: Garcia publishes and presents frequently in preparation for books she is currently writing. Her work is crucial to understanding dispossession and power dynamics within the United States and Mexico, including how immigration and migration affect access to health care and shape identity.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Briefly explain how the biological processes of evolution and genetics impact human health and wellness.

- Describe how human migration, social behavior, and cultural values impact gene flow, genetic drift, sexual selection, and human reproduction.

- Define neuroanthropology.

- Provide two examples of culture-bound syndromes.

- Describe various ways in which political and economic forces impact health outcomes.

- Explain how globalization has increased the flow of pathogens and introduced new diseases and viruses.

Anthropology is an adaptable field of study. Its principles, theories, and methods can easily be applied to real-world problem-solving in diverse settings. Medical anthropology is designed to be applied to the critical study and improved practice of medicine. Medical anthropology has been employed in corporate settings, has been used by doctors who want to reduce ethnocentrism or apply a holistic approach to medical research and medical education, and has informed the work of academics who want to effect policy changes. The following are but a few examples of applied medical anthropologists working to create change in the real world.

Evolutionary Medicine and Health

A final theoretical approach to medical anthropology, emerging from biological anthropology, is evolutionary medicine. Evolutionary medicine sits at the intersection of evolutionary biology and human health, using the framework of evolution and evolutionary theory to understand human health. Evolutionary medicine asks why human health evolved the way it did, how environments affect health, and how we continue to affect our health through a number of factors including migration, nutrition, and epigenetics.

The story of human evolution is the story of gene flow and human migration. Each individual human carries specific gene combinations, and each human population carries with it a common set of genes. When people migrate, they bring those genes with them. If they have children, they pass those genes on in new combinations. Culture impacts population genetics in two ways: migration patterns and culturally defined rules of sexual selection impact the frequency of gene alleles, and thus genetic variation, in a human population. These genes often affect health outcomes, such as the likelihood of developing certain types of cancer or immunity to specific pathogens through exposure. The more frequently a human population interacts with other populations through migration, trade, and other forms of cultural exchange, the more likely it is that genetic material from one population will be introduced to the other. The current level of globalization makes it possible for genes to flow from one corner of the globe to another.

Moving into a new culture, whether forced or voluntary, requires adaptation. Adapting one’s culture to new rules, new norms, and new expectations, as well as adapting one’s identity to being a minority or facing oppression or prejudice, can affect the health of the migration population. An obvious example of this is the effects of slavery on Africans brought to the Americas. This impact is shown not just on their genetics, discussed elsewhere in this chapter, but also in their cultures. Syncretized religions like Haitian Vodou, Candomblé, and other African-inspired religions show the ways in which African populations adapted their beliefs to survive contact with oppression and cruelty, evolving and sanitizing certain elements while embracing others.

Populations that are physically isolated for long periods of time might experience negative effects from genetic drift as the frequency of rare alleles increases over time. Similarly, cultural groups that practice strict endogamy can experience negative effects from genetic drift. In isolation, populations can sometimes see a rise in the frequency of maladaptive gene variants, as in the case of Tay-Sachs disease found in ethnic minority populations that practice endogamy, such as Ashkenazi Jews or French Canadians. Among these populations, which have been relatively isolated from the populations around them, the genes that cause Tay-Sachs have become more common than in other populations. This suggests that isolation and segregation can result in unhealthy changes in a population’s gene pool.

Another example of evolutionary medicine is the study of the effects of the development of agriculture and the growth of urbanization on human health. The development of agriculture caused human health to change in many ways. Food became more regularly available, but diet became less varied and the amount of work required to procure the food increased. The regular movement associated with a gathering and hunting lifestyle resulted in robust overall fitness, but people were also at a greater danger of succumbing to a fatal accident before reaching the age at which they successfully reproduced. Our current lifestyle, in which many sit behind a desk for eight hours a day, five days a week, damages our spines and overall health. While food availability in Western nations is second to none, people living in those societies struggle with health problems related to being overweight and underactive. Each lifestyle has its trade-offs, and evolution has, over the past ten thousand years, affected both modern and neolithic humans differently. Through evolutionary health, we can track these changes and their adaptations.

With human migration and the concentration of human populations in urban areas, disease has grown exponentially. Pathogens can now spread like wildfire across the world. In the past, disease has had a devastating effect on human populations. As just one example, the Black Death killed over a third of Europe’s population, spreading via Silk Road merchants and the conquests of the Mongol Empire. Today we see yearly flare-ups of influenza and Ebola and are still dealing with the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that caused nations to close borders and people within nations to limit social contact with one another. Globalization not only makes it possible for pathogens and pandemics to spread, but also allows nations to cooperatively distribute vaccines and coordinate methods to contain viruses. Nations can now share medical data to help develop treatments and help one another in efforts to isolate and quarantine the sick and infected. On the other hand, international cooperation can hamper local response and prevent cities, provinces, states, and nations from acting in their own best interest.

At the heart of each of these areas of study is epigenetics, or the change of the expression of a gene during a single human lifetime. Often prompted by environmental exposure and mutations over a lifetime, epigenetic shifts are heritable changes in a person’s DNA that are phenotypical, meaning that they are linked to outwardly expressed traits. For example, studies show that people exposed to smoking in childhood tend to be shorter in adulthood. Similarly, trauma can stunt growth or increase the likelihood of developing specific maladaptations. The development of sickle cell anemia in the African American community has been linked to epigenetic adaptation to slavery in the United States, according to a 2016 study by Juliana Lindenau et al. This and other studies suggest that trauma can be inherited and can last generations. Epigenetics show evolution at work in real time, affecting both individuals and future generations.

Culture and the Brain

The human brain is a fascinating research topic, both medically and culturally. Different cultures conceptualize the brain, its functions, and its health differently. Biomedicine and ethnomedicine systems view human physiology in distinct ways, and these two systems typically have very different explanatory models for understanding the brain and its role in psychology and neurology. Anthropologists are interested in both of these explanatory models and the ways they influence treatment. Some topics of particular interest to medical anthropologists include how psychology affects biology and health, the stigma of mental health across cultures, addiction, culture-bound syndromes, and experiences and illnesses related to stress. Daniel Lende and Greg Downey brought together these topics under the heading of neuroanthropology, an emerging specialty that examines the relationship between culture and the brain.

As highlighted during the discussion of the cultural systems model, the acceptance of psychology is highly variable by culture. Societies that rely upon biomedicine are more apt to embrace psychological approaches to mental health problems. Encouraging other cultures to apply psychology and psychiatry sometimes requires an anthropologist’s touch. One challenge for a medical anthropologist is convincing people who do not believe in mental health challenges that acknowledging and treating mental health issues is a better approach than ignoring them. India’s slow but eventual acceptance of psychology is described by Rebecca Clay in a 2002 article. In this case, psychology was gradually normalized and accepted through a combination of Indian medical theory and psychological treatments and diagnosis. This culturally based path toward normalization indicates the need for cultural understanding and a nuanced approach by medical anthropologists.

Culturally specific nuance is especially important in understanding what anthropologists call culture-bound syndromes. Culture-bound syndromes refer to unique ways in which a particular culture conceptualizes the manifestations of mental illness, whether as physical and/or social symptoms. The condition is a “cultural syndrome” in that it is not a biologically based disease identified among other populations.

A prominent example is susto, a syndrome in Latino societies of the Americas. First documented by Rubel, O’Nell, and Collado-Ardon (1991), susto is stress, panic, or fear caused by bearing witness to traumatic experiences happening to other people around you. Originating with Indigenous groups in the Americas, this panic attack–like illness was seen as a spiritual attack on people and has a number of symptoms ranging from nervousness and depression to anorexia and fever. Cultural syndromes are not limited to non-Western societies, however. According to anthropologist Caroline Giles Banks (1992), anorexia nervosa, an eating disorder where the person does not eat in order to stay thin in accordance with the beauty standards in the United States and Europe, is a prime example of a culture-bound syndrome. Only in these cultures, with specific pressures on weight and beauty applied to women and men, does anorexia nervosa appear. But as these beauty standards spread with globalization and the spread of media from these cultures, so does the disease. Cultural syndromes are not restricted to cultures that prefer biomedicine or ethnomedicine: they are as diverse as human culture itself.

A related concept gaining ground in psychology is known as cultural concepts of distress, or CCD. These concepts, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 5, “refer to ways that cultural groups experience, understand, and communicate suffering, behavioral problems, or troubling thoughts and emotions” (American Psychiatric Association 2013). In sum, CCD is used to describe how a culture explains and conceptualizes the unique manifestation of mental illness as physical and/or social symptoms.

The psychobiological dynamic of health—the measurable effect of human psychology on physical health—is a primary tool used by medical anthropologists to study health. The psychobiological dynamic of health helps anthropologists evaluate the efficacy of health-related treatments that may not accord with those used in their home culture. For example, ritual healing has real measurable effects on people, both the patient and those in attendance during the ritual, as long as they believe that the ritual has healing power. Similarly, for those who share a cultural belief in the power of such practices, being prayed over by a priest or blessed with holy water can offer effective healing power. Psychological belief grants healing efficacy. The same principle applies to biomedicine, as illustrated by the placebo/nocebo effect. Of course, belief alone cannot entirely negate the harmful or helpful effects of medicine or any other substance.

Another area in which psychology and health intersect is the experience and effects of stress, a human universal. Indeed, it is well established that mental stress can make someone physically sick. The work of anthropologist Robert Sapolsky (2004) analyzes the evolution of the human body to adapt to, use, and heal from stress. His analysis suggests that stress pushes humans to both physical and mental limits, that these limits differ in different humans, and that being pushed up against limits due to stress can result in growth. The human ability to adapt to stress is a difference from other primate species, and it likely developed over millions of years of evolution. While human bodies have evolved with stress and have sometimes grown as a result of stress, we were not evolved to withstand chronic stress over extended periods of time. Chronic stress induces a high rate of stress-related diseases, such as heart disease, indicating the limits of even evolution to adapt to long-term stressors.

Addiction is another area in which medical anthropologists have done significant work, analyzing how culture and biology contribute to addiction. Addiction comes in many forms and affects multiple measures of health. Medical anthropologist Angela Garcia tackles addiction in her book The Pastoral Clinic: Addiction and Dispossession along the Rio Grande (2010), which explores the intersection of race, class, immigration status, and dispossession with drug addiction and the ability to treat it. Focusing on a small town on the Rio Grande and specifically a clinic within that town meant to treat addiction, she tracks the trajectory of a number of patients and the factors that contributed to their addiction. Her analysis highlights the status of these patient as immigrants, minorities, and outsiders, which prevent reentry into society for many. Similarly, João Biehl’s work Vita: Life in a Zone of Social Abandonment (2103) analyzes the effects of dispossession and homelessness on social health, looking specifically at the role of drugs in the highlighted zone. His exploration of vita, a place where people are “left to die” when their addiction or mental illness becomes too much of a burden, shows the cultural effects of mental health and addiction on Brazilian society and the struggles of the individuals abandoned there. In both works, the role of drugs is highlighted, exploring how cultures symbolically characterize problematic drug use and addiction and attach a stigma to admitting a problem and seeking treatment. The works also explore how drugs are justified and understood, illustrating both how drugs change the biochemistry of the brain and how the human mind characterizes the drugs, each shaping one another.

Reproduction

Reproductive health is another area in which medical anthropologists have made significant contributions by applying their knowledge and methods to real medical practices. Medical anthropologists have studied reproduction in many cultures, analyzing the practices, beliefs, and treatment of those who are pregnant, their children, and their supporting network. Another area of interest has been the ritualization of pregnancy. Robbie Davis Floyd (2004) has done work on birth as a rite of passage and the role of the midwife in modern birth practices around the world, with a focus on medicalized birth in the United States. Her work highlights ways in which the experience of birth is made more complicated by policy. Midwives are shown to decrease the chances of complications in births, yet in many places they are denied a role in the birthing process. Regardless of patient preference and the documented success of midwives, in most settings in the United States doctors and medical professionals are given preference over midwives. Floyd argues that this preference sometimes puts the patient at risk. In the Western biomedical system, doctors are preferred and imbued with authoritative knowledge, which is a sense of legitimacy or perceived authenticity.

The work of Dána-Ain Davis (2019) on medical racism and inequalities in the healthcare system shows structural violence at work. Based on analysis of statistics and vivid ethnographic examples, Davis found that women of color experienced significantly higher rates of complications, including higher death rates for both mothers and infants, than White mothers and babies. Davis concludes that cultural bias and systemic racism are woven into the US healthcare system. These are often unacknowledged biases, unrecognized by those perpetrating them in the medical profession. Davis advocates for better policy to address these inequalities and help mothers maintain control over their bodies and the birthing process.

PROFILES IN ANTHROPOLOGY

Dána-Ain Davis 1958-

Personal History: Born in New York City, Dána-Ain Davis earned her PhD from City University of New York. Her work focuses on poverty, policy, and feminism, with a specific interest in urban areas of the United States. She is currently a professor of anthropology at Queens College (part of the City University of New York system). In addition to her teaching, she promotes change in policy and society through activism and her work in numerous political communities.

Before enrolling in college, Davis worked widely in publishing, broadcasting, and nonprofit work. She has worked for the Village Voice newspaper, the YWCA, the Village Center for Women, and Bronx AIDS Service. This work grounded her deeply in her community and the issues facing women, and in particular Black women in urban communities such as hers. These skills would aid her as she earned her PhD and began publishing her academic work.

She is the editor of Feminist Anthropology, a new journal focused on feminist anthropological work; sits on the editorial boards for Cultural Anthropology and Women’s’ Studies Quarterly; and in the fall of 2021 became the chair of her department.

Area of Anthropology: cultural anthropology, medical anthropology, public anthropology, feminist anthropology, urban anthropology

Accomplishments in the Field: Davis’s first book, Battered Black Women and Welfare Reform: Between a Rock and a Hard Place, was published in 2006 and focuses on the intersection of gender, race, and economic realities. The book also features her work with the theory of political economy, which looks at how economic conditions, law, and policy affect wealth distribution across groups, in this case how economic conditions disadvantage Black women. Davis then worked on two edited volumes focused on feminism and gender, entitled Black Genders and Sexualities (2012) and Feminist Activist Ethnography: Counterpoints to Neoliberalism in North America (2013), before publishing Feminist Ethnography: Thinking through Methodologies, Challenges, and Possibilities (2016) about feminism anthropology and ethnographic work.

Davis’s next work, Reproductive Injustice: Racism, Pregnancy, and Premature Birth (2019) fits more squarely into the realm of medical anthropology. This work examines the numerous issues that face women of color in regard to pregnancy and birth. Like her previous work, her latest book intersects with activism, aiming to improve medical and social justice for mothers and children.

Importance of Their Work: Activism sits at the heart of Davis’s work, which has won numerous awards for promoting justice and change. Her academic and activist work has helped inform new policy changes at the local, state, and national levels. Her work informs continuing work in urban studies, feminist theory and practice, reproductive health for women of color, and welfare reform.

The Inequalities of Health

Attempting to address the inequalities of health care is a primary application of the work of critical medical anthropologists. Inequalities are apparent in relation to COVID-19, the global pandemic that has left no corner of the world untouched. A number of agencies in the United States, including the National Institutes of Health and the American Civil Liberties Union, have determined that Black and Latinx populations have been most negatively affected by the virus, both in health outcomes and overall deaths per capita relative to their portion of the population. Several states have emphasized the need to ignore personal safety for the sake of economic “health,” essentially stating a willingness to sacrifice workers so their economic prospects do not falter. Meanwhile, people working on the front lines faced what is tantamount to class violence, as they could not afford to stay safely at home and social distance; indeed, it can be argued that later this class violence still applied, as the divide between remote working and those forced to work on-site created a stark contrast. The health of “essential workers” is put at risk. Aside from health care professionals, the category frequently falls along class lines, with the majority of “essential workers” employed in the service industry, in factories, or making deliveries. Economic inequalities and lack of access to health care providers both play a role in these trends. Similarly, the World Health Organization has highlighted how poorer countries have had their access to the many forms of COVID-19 treatment and prevention restricted by the demands of richer countries like the United States and Australia.

Another area in which medical anthropologists have documented health-related inequalities in the United States is access to nutritious foods. It has been well established that poor access to foods, particularly highly nutritious, diverse foods, can negatively affect health. People who live in food deserts, which are areas lacking access to good food, are more likely to develop debilitating illnesses and suffer from a basic lack of nutrition in several major fields. Amplifying the effect of food deserts is that these same areas often also lack access to health care services.

AIDS has provided a multigenerational study of the inequalities of health. At the beginning of the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s, the poorly understood disease was stated to be a “gay man’s virus” because it seemed to only affect gay and bisexual men. Medical anthropologists began studying the AIDS virus as early as 1983, with Norman Spencer notably studying cases in San Francisco. As the virus spread to other populations, research became more common and well-funded, receiving state support in some cases. Yet between poor and late funding and the spread of misinformation that took decades to reverse, AIDS devastated populations around the world. Medical anthropologist Brodie Ramin (2007) has applied anthropological knowledge and methods to AIDS treatment in Africa, utilizing cultural understanding to develop more effective methods of medical treatment and enhance public trust in these treatment methods.

Even today, AIDS is highly stigmatized and poorly treated in many places in the world. For over two decades now, Paul Farmer and Jim Yong Kim, both anthropologists and medical doctors, have worked with their organization, Partners in Health, to provide better health outcomes and access to poor, remote parts of the world. Their work has been instrumental in helping treat AIDS and other diseases in places such as Haiti. Jim Yong Kim used his role in the World Bank Group to help create better outcomes as well. Medical anthropology has the power to shape policy at the highest level of global health institutions, but it has much to overcome. Medical anthropologists are well aware of the severity of the problems of structural violence, systemic racism, and massive health inequalities around the world.