4.3: SPECIAL TOPIC: DIABETES

Diabetes Mellitus is an endocrine disorder characterized by excessively high blood glucose levels (Martini et al. 2013). According to a report released by the World Health Organization, the number of people living with diabetes is growing in all regions of the world. Rates of diabetes have nearly doubled in the past three decades, largely due to increases in obesity and sugary diets (WHO 2016). One in 11 people around the world, 435 million people, now have diabetes, including over 30 million Americans. In the United States, the disease is rising fastest among millennials (those ages 20-40) (BCBSA 2017), and one in every two adults with diabetes is undiagnosed (IDF 2018). Obesity and diabetes are linked: that is, obesity causes a diet-related disease (diabetes) because of humans’ evolved metabolic homeostasis mechanism, which is mismatched to contemporary energy environments (Lucock et al. 2014).

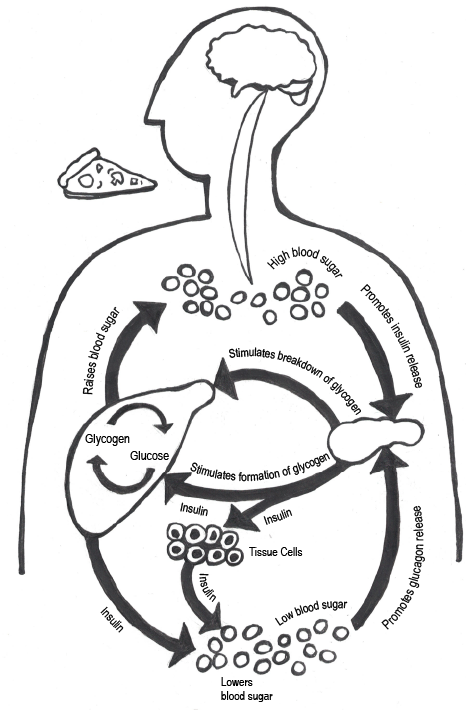

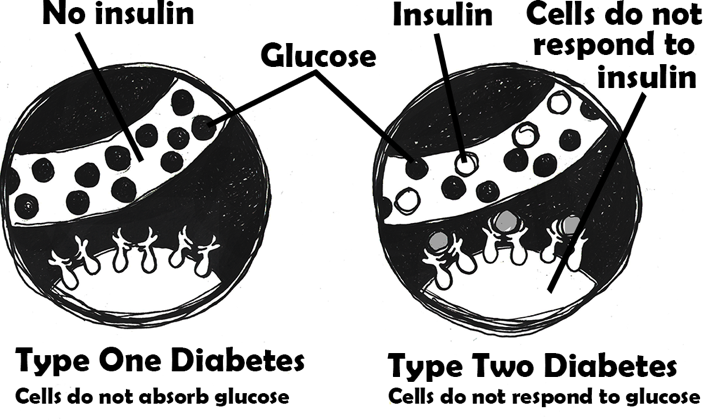

To function properly, cells need a steady fuel supply. Blood sugar is the primary fuel for most cells in the body, and the body produces the hormone insulin to help move energy into cells that need it. Insulin functions like a key, turning on insulin receptors located on the surface of the cell. The receptor then activates glucose transporters (GLUTs) that do the work of hauling glucose (blood sugar) out of your bloodstream and into your cells (McKee and McKee 2015; see Figure 16.7). Foods that most readily supply glucose to your bloodstream are carbohydrates, especially starchy foods like potatoes or sweet, sugary foods like candy and soda. The body can also convert other types of foods, including protein-rich foods (e.g., lean meats) and fatty foods (e.g., vegetable oils and butter), into blood sugar in the liver via gluconeogenesis. Insulin’s main job is to tell your cells when to take up glucose. The cell also has to listen to the signal and mobilize the glucose transporters. This not only allows your cells to get the energy they need, but it also keeps blood sugar from building up to dangerously high levels when you are at rest. Muscles can use glucose without insulin when you are exercising; it does not matter if you are insulin resistant or if you do not make enough insulin. When you exercise, your muscles get the glucose they need, and, in turn, your blood glucose level goes down. If you are insulin resistant, resistance goes down when you exercise and your cells use glucose more effectively (Leontis n.d.).

This system is efficient, but there are limits. Keep in mind that, like the rest of our biology, it evolved during several million years when sugar was hard to come by and carbohydrates took the form of fresh foods with a low glycemic index (GI). Our ancestors were also active throughout the day, taking pressure off of the endocrine system. Now, sedentary lifestyles and processed-food diets cause many of us to take in more calories—and especially more carbohydrates—than our bodies can handle. The fact is, there is only so much blood sugar your cells can absorb. As soaring rates of diabetes show, many modern populations are taxing those limits. After years of being asked by insulin to take in more glucose than they can use, cells eventually stop responding (McKee and McKee 2015). This is called Type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance, which accounts for 90–95% of diabetes cases in the United States. People with Type 1 diabetes do not produce insulin (O’Keefe Osborn 2017; see Figure 16.8).

Type 2 diabetes is a progressive metabolic condition that occurs over time when our evolved biological mechanism that turns food into energy is derailed by the obesogenic environments in which we live. This is compounded by a sedentary lifestyle. Think about how living in a college environment contributes to the development of diabetes. How much time do you spend sitting each day? How many sugary—and often cheap—carbohydrates are within easy reach? Making simple changes now can head off health complications later. Carrying an apple or orange in your backpack instead of a candy bar and walking or biking instead of driving can make a big difference.