3.2: ETHNO-ETIOLOGY

Ethnomedicine is the comparative study of cultural ideas about wellness, illness, and healing. For the majority of our existence, human beings have depended on the resources of the natural environment and on health and healing techniques closely associated with spiritual beliefs. Many such practices, including some herbal remedies and techniques like acupuncture, have been studied scientifically and found to be effective.[13] Others have not necessarily been proven medically effective by external scientific evidence, but continue to be embraced by communities that perceive them to be useful. When considering cultural ideas about health, an important place to start is with ethno-etiology: cultural explanations about the underlying causes of health problems.

In the United States the dominant approach to thinking about health is biomedical. Illnesses are thought to be the result of specific, identifiable agents. This can include pathogens (viruses or bacteria), malfunction of the body’s biochemical processes (conditions such as cancer), or physiological disorders (such as organ failure). In biomedicine as it is practiced in the United States (Western biomedicine), health is defined as the absence of disease or dysfunction, a perspective that notably excludes consideration of social or spiritual well-being. In non-Western contexts biomedical explanations are often viewed as unsatisfactory. In his analysis of ideas about health and illness in non-Western cultures, George Foster (1976) concluded that these ideas could be categorizes into two main types of ethno-etiology: personalistic and naturalistic.[14]

Ethno-Etiologies: Personalistic and Naturalistic

Personalistic ethno-etiologies view disease as the result of the “active, purposeful intervention of an agent, who may be human (a witch or sorcerer), nonhuman (a ghost, an ancestor, an evil spirit), or supernatural (a deity or other very powerful being).”[15] Illness in this kind of ethno-etiology is viewed as the result of aggression or punishment directed purposefully toward an individual; there is no accident or random chance involved. Practitioners who are consulted to provide treatment are interested in discovering who is responsible for the illness—a ghost, an ancestor? No one is particularly interested in discovering how the medical condition arose in terms of the anatomy or biology involved. This is because treating the illness will require neutralizing or satisfying a person, or a supernatural entity, and correctly identifying the being who is the root cause of the problem is essential for achieving a cure.

The Heiban Nuba people of southern Sudan provide an interesting example of a personalistic etiology. As described by, S.F. Nadel in the 1940s, the members of this society had a strong belief that illness and other misfortune was the result of witchcraft.

A certain magic, mysteriously appearing in individuals, causes the death or illness of anyone who eats their grain or spills their beer. Even spectacular success, wealth too quickly won, is suspect; for it is the work of a spirit-double, who steals grain or livestock for his human twin. This universe full of malignant forces is reflected in a bewildering array of rituals, fixed and occasional, which mark almost every activity of tribal life.[16]

Because sickness is thought to be caused by spiritual attacks from others in the community, people who become sick seek supernatural solutions. The person consulted is often a shaman, a person who specializes in contacting the world of the spirits.

In Heiban Nuba culture, as well as in other societies where shamans exist, the shaman is believed to be capable of entering a trance-like state in order to cross between the ordinary and supernatural realms. While in this state, the shaman can identify the individual responsible for causing the illness and sometimes the spirits can be convinced to cure the disease itself. Shamans are common all around the world and despite the proverbial saying that “prostitution is the oldest profession,” shamanism probably is! Shamans are religious and medical practitioners who play important social roles in their communities as healers with a transcendent ability to navigate the spirit world for answers. In addition, the often have a comprehensive knowledge of the local ecology and how to use plants medicinally. They can address illnesses using both natural and supernatural tools.

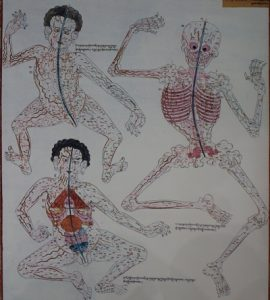

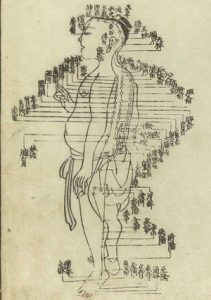

In naturalistic ethno-etiologies, diseases are thought to be the result of natural forces such as “cold, heat, winds, dampness, and above all, by an upset in the balance of the basic body elements.”[17] The ancient Greek idea that health results from a balance between the four humors is an example of a naturalistic explanation. The concept of the yin and yang, which represent opposite but complementary energies, is a similar idea from traditional Chinese medicine. Achieving balance or harmony between these two forces is viewed as essential to physical and emotional health. Unlike personalistic explanations, practitioners who treat illness in societies with naturalistic ethno-etiologies are interested in understanding how the medical condition arose so that they can choose therapeutic remedies viewed as most appropriate.

Emotional difficulties can be viewed as the cause of illness in a naturalistic ethno-etiology (an emotionalistic explanation). One example of a medical problem associated with emotion is susto, an illness recognized by the Mixe, an indigenous group who live in Oaxaca, Mexico, as well as others throughout central America. The symptoms of susto include difficulty sleeping, lack of energy, loss of appetite and sometimes nausea/vomiting and fever. The condition is believed to be a result of a “fright” or shock and, in some cases at least, it is believed to begin with a shock so strong that it disengages the soul from the body.[18] The condition is usually treated with herbal remedies and barrida (sweeping) ceremonies designed to repair the harm caused by the shock itself.[19] Although physicians operating within a biomedical ethno-etiology have suggested that susto is a psychiatric illness that in other cultural contexts could be labeled anxiety or depression, in fact susto is does not fit easily into any one Western biomedical category. Those suffering from susto see their condition as a malady that is emotional, spiritual, and physical.[20]

In practice, people assess medical problems using a variety of explanations and in any given society personalistic, naturalistic, or even biomedical explanations may all apply in different situations. It is also important to keep in mind that the line between a medical concern and other kinds of life challenges can be blurry. An illness may be viewed as just one more instance of general misfortune such as crop failure or disappointment in love. Among the Azande in Central Africa, witchcraft is thought to be responsible for almost all misfortune, including illness. E.E. Evans-Pritchard, an anthropologist who studied the Azande of north-central Africa in the 1930s, famously described this logic be describing a situation in which a granary, a building used to store grain collapsed.

In Zandeland sometimes an old granary collapses. There is nothing remarkable in this. Every Zande knows that termites eat the supports in course of time and that even the hardest woods decay after years of service. Now a granary is the summerhouse of a Zande homestead and people sit beneath it in the heat of the day and chat or play the African hole-game or work at some craft. Consequently it may happen that there are people sitting beneath the granary when it collapses and they are injured…Now why should these particular people have been sitting under this particular granary at the particular moment when it collapsed? That it should collapse is easily intelligible, but why should it have collapsed at the particular moment when these particular people were sitting beneath it…The Zande knows that the supports were undermined by termites and that people were sitting beneath the granary in order to escape the heat of the sun. But he knows besides why these two events occurred at a precisely similar moment in time and space. It was due to the action of witchcraft. If there had been no witchcraft people would have been sitting under the granary and it would not have fallen on them, or it would have collapsed but the people would not have been sheltering under it at the time. Witchcraft explains the coincidence of these two happenings.[21]

According to this logic, an illness of the body is ultimately caused by the same force as the collapse of the granary: witchcraft. In this case, an appropriate treatment may not even be focused on the body itself. Ideas about health are often inseparable from religious beliefs and general cultural assumptions about misfortune.[22]

Is Western Biomedicine An Ethno-Etiology?

The biomedical approach to health strikes many people, particularly residents of the United States, as the best or at least the most “fact based” approach to medicine. This is largely because Western biomedicine is based on the application of insights from science, particularly biology and chemistry, to the diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions. The effectiveness of biomedical treatments is assessed through rigorous testing using the scientific method and indeed Western biomedicine has produced successful treatments for many dangerous and complex conditions: everything from antibiotics and cures for cancer to organ transplantation.

However, it is important to remember that the biomedical approach is itself embedded in a distinct cultural tradition, just like other ethno-etiologies. Biomedicine, and the scientific disciplines on which it is based, are products of Western history. The earliest Greek physicians Hippocrates (c. 406-370 BC) and Galen (c. 129-c. 200 AD) shaped the development of the biomedical perspective by providing early insights into anatomy, physiology, and the relationship between environment and health. From its origins in ancient Greece and Rome, the knowledge base that matured into contemporary Western biomedicine developed as part of the Scientific Revolution in Europe, slowly maturing into the medical profession recognized today. While the scientific method used in Western biomedicine represents a distinct and powerful “way of knowing” compared to other etiologies, the methods, procedures, and forms of reasoning used in biomedicine are products of Western culture. [23]

In matters of health, as in other aspects of life, ethnocentrism predisposes people to believe that their own culture’s traditions are the most effective. People from non-Western cultures do not necessarily agree that Western biomedicine is superior to their own ethno-etiologies. Western culture does not even have a monopoly on the concept of “science.” Other cultures recognize their own forms of science separate from the Western tradition and these sciences have histories dating back hundreds or even thousands of years. One example is Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), a set of practices developed over more than 2,500 years to address physical complaints holistically through acupuncture, exercise, and herbal remedies. The tenets of Traditional Chinese Medicine are not based on science as it is defined in Western culture, but millions of people, including a growing number of people in the United States and Europe, regard TCM as credible and effective.

Ultimately, all ethno-etiologies are rooted in shared cultural perceptions about the way the world works. Western biomedicine practitioners would correctly observe that the strength of Western biomedicine is derived from use of a scientific method that emphasizes objective observable facts. However, this this would not be particularly persuasive to someone whose culture uses a different ethno-etiology or whose understanding of the world derives from a different tradition of “science.” From a comparative perspective, Western biomedicine may be viewed as one ethno-etiology in a world of many alternatives.

CONCLUSION

As the global population becomes larger, it is increasingly challenging to address the health needs of the world’s population. Today, 1 in 8 people in the world do not have access to adequate nutrition, the most basic element of good health.[61] More than half the human population lives in an urban environment where infectious diseases can spread rapidly, sparking pandemics. Many of these cities include dense concentrations of poverty and healthcare systems that are not adequate to meet demand. [62] Globalization, a process that connects cultures through trade, tourism, and migration, contributes to the spread of pathogens that negatively affect human health and exacerbates political and economic inequalities that make the provision of healthcare more difficult.

Human health is complex and these are daunting challenges, but medical anthropologists have a unique perspective to contribute to finding solutions. Medical anthropology offers a holistic perspective on human evolutionary and biocultural adaptations as well as insights into the relationship between health and culture. As anthropologists study the ways people think about health and illness and the socioeconomic and cultural dynamics that affect the provision of health services, there is a potential to develop new methods for improving the health and quality of life for people all over the world.

KEY TERMS

Adaptive: Traits that increase the capacity of individuals to survive and reproduce.

Biocultural evolution: Describes the interactions between biology and culture that have influenced human evolution.

Biomedical: An approach to medicine that is based on the application of insights from science, particularly biology and chemistry.

Communal healing: An approach to healing that directs the combined efforts of the community toward treating illness.

Culture-bound syndrome: An illness recognized only within a specific culture.

Emotionalistic explanation: Suggests that illnesses are caused by strong emotions such as fright, anger, or grief; this is an example of a naturalistic ethno-etiology.

Epidemiological transition: The sharp drop in mortality rates, particularly among children, that occurs in a society as a result of improved sanitation and access to healthcare.

Ethno-etiology: Cultural explanations about the underlying causes of health problems.

Ethnomedicine: The comparative study of cultural ideas about wellness, illness, and healing.

Humoral healing: An approach to healing that seeks to treat medical ailments by achieving a balance between the forces, or elements, of the body.

Maladaptive: Traits that decrease the capacity of individuals to survive and reproduce.

Medical anthropology: A distinct sub-specialty within the discipline of anthropology that investigates human health and health care systems in comparative perspective.

Naturalistic ethno-etiology: Views disease as the result of natural forces such as cold, heat, winds, or an upset in the balance of the basic body elements.

Personalistic ethno-etiology: Views disease as the result of the actions of human or supernatural beings.

Placebo effect: A response to treatment that occurs because the person receiving the treatment believes it will work, not because the treatment itself is effective.

Shaman: A person who specializes in contacting the world of the spirits.

Somatic: Symptoms that are physical manifestations of emotional pain.

Zoonotic: Diseases that have origins in animals and are transmitted to humans.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sashur Henninger-Rener is an anthropologist with research in the fields of comparative religion and psychological anthropology. She received a Master of Arts from Columbia University in the City of New York in Anthropology and has since been researching and teaching. Currently, Sashur is an instructor at Pasadena City College, teaching Cultural and Biological Anthropology. In her free time, Sashur enjoys traveling the world, visiting archaeological and cultural sites along the way. She and her husband are actively involved in animal rescuing, hoping to eventually found their own animal rescue for animals that are waiting to find homes.

CITATION/ATTRIBUTION

Brown, N., McIlwraith, T., & González, L. T. de. (2020). Health and Medicine. Pressbooks.pub. https://pressbooks.pub/perspectives/chapter/health-and-medicine/

REFERENCES

Jermone Gilbert, Humors, Hormones, and Neurosecretions (New York: State University of New York Press, 1962). ↵

World Health Organization, “Health Impact Assessment,” http://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/. ↵

Sally McBrearty and Allison Brooks, “The Revolution That Wasn’t: A New Interpretation of the Origin of Modern Humans,” Journal of Human Evolution 39 (1999), 453-563. ↵

U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, “Adult Obesity Facts,” http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html. ↵

Marjorie G. Whiting, A Cross Cultural Nutrition Survey (Cambridge, MA: Harvard School of Public Health, 1968). ↵

Ian A.M. Prior, “The Price of Civilization,” Nutrition Today 6 no. 4 (1971): 2-11. ↵

Steven Connor, “Deadly malaria may have risen with the spread of agriculture,” National Geographic, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/06/0625_wiresmalaria.html. ↵

Jared Diamond, “The Arrow of Disease,” Discover Magazine, October 1992. http://discovermagazine.com/1992/oct/thearrowofdiseas137. ↵

World Health Organization, “Cholera,” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs107/en/. ↵

George J. Armelagos and John R. Dewey, “Evolutionary Response to Human Infectious Disease,” BioScience, 25(1970): 271-275. ↵

William McNeill, Plagues and People (New York: Doubleday, 1976). ↵

Ian Barnes, Anna Duda, Oliver Pybus, Mark G. Thomas. Ancient Urbanisation Predicts Genetic Resistance To Tuberculosis,” Evolution 65 no. 3 (2011): 842-848. ↵

George T. Lewith, Acupuncture: Its Place in Western Medical Science (United Kingdom: Merlin Press, 1998). ↵

George M. Foster, “Disease Etiologies in Non-Western Medical Systems,”American Anthropologist 78 no 4 (1976): 773-782. ↵

Ibid., 775 ↵

S.F. Nadel, The Nuba: An Anthropological Study of the Hill Tribes in Kordofan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1947), 173. ↵

Foster, “Disease Etiologies in Non-Western Medical Systems,” 775. ↵

A.J. Rubel, “The Epidemiology of a Folk Illness: Susto in Hispanic America,” Ethnology3 (1964): 268-283. ↵

Robert T. Trotter II, “Susto: The Context of Community Morbidity Patterns,” Ethnology 21 no. 3 (1982): 215-226. ↵

Frank J. Lipp, “The Study of Disease in Relation to Culture: The Susto Complexe Among the Mixe of Oaxaco,” Dialectical Anthropology 12 no. 4 (1987): 435-442. ↵

E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1937), 70. ↵

Leonard B. Glick, “Medicine as an Ethnographic Category: The Gimi of the New Guinea Highlands,” Ethnology 6 (1967): 31-56. ↵

Elliott Mishler, “Viewpoint: Critical Perspectives on the Biomedical Model,” inE. Mishler, L.A. Rhodes, S. Hauser, R. Liem, S. Osherson, and N. Waxler, eds.Social Contexts of Health, Illness, and Patient Care (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press). ↵

Richard Katz, Megan Biesele, and Verna St. Davis, Healing Makes Our Hearts Happy: Spirituality and Cultural Transformation among the Kalahari Ju/ ’hoansi (Rochester VS, Inner Traditions, 1982), 34. ↵

Michael Bliss, William Osler: A Life in Medicine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 276. ↵

William Osler, “The Faith That Heals,” British Medical Journal 1 (1910): 1470-1472. ↵

Cara Feinberg, “The Placebo Phenomenon,” Harvard Magazine http://harvardmagazine.com/2013/01/the-placebo-phenomenon. ↵

Ted J. Kaptchuk, and Franklin G. Miller, “Placebo Effects in Medicine,” New England Journal of Medicine 373 (2015):8-9. ↵

Robert Bud, “Antibiotics: From Germophobia to the Carefree Life and Back Again,” in Medicating Modern America: Prescription Drugs in History, ed. Andrea Tone and Elizabeth Siegel Watkins (New York: New York University Press, 2007). ↵

H. Benson, J.A. Dusek, J.B. Sherwood, P. Lam, C.F. Bethea, and W. Carpenter, “Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP) in Cardiac Bypass Patients: A Multicenter Randomized Trial of Uncertainty and Certainty of Receiving Intercessory Prayer,” American Heart Journal 151 (2006):934–942. ↵

National Cancer Institute, “Acupuncture,” http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/acupuncture/healthprofessional/page5. ↵

Mira Taow, “The Religious and Medicinal Uses of Cannabis in China, India, and Tibet,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 13(1981): 23-24. ↵

Marsella, A. and White, G., eds. Cultural Conceptions of Mental Health and Therapy (Dordrecht, Netherlands: D. Reidel, 1982). ↵

Dominic T.S. Lee, Joan Kleinman, and Arthur Kleinman, “Rethinking Depression: An Ethnographic Study of the Experiences of Depression Among Chinese,” Harvard Review of Psychiatry 15 no 1 (2007):1-8. ↵

Arthur Kleinman, Rethinking Psychiatry: From Cultural Category to Personal Experience (New York: The Free Press, 1988). ↵

Robert Lemelson and L.K. Suryani, “Cultural Formulation of Psychiatric Diagnoses: The Spirits, Penyakit Ngeb and the Social Suppression of Memory: A Complex Clinical Case from Bali,” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 30 no. 3 (2006): 389-413. ↵

For more information about these studies, see J. Leff et al., “The International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia: Five-Year Follow-Up Findings,” Psychological Medicine 22 (1992):131–45; A. Jablensky et al., “Schizophrenia: Manifestations, Incidence and Course in Different Cultures: A World Health Organization Ten-Country Study,” Psychological Medicine Monograph Supplement 20(1992); N. Sartorius et al., “Early Manifestations and First-Contact Incidence of Schizophrenia in Different Cultures,” Psychological Medicine 16 (1986):909–28. ↵

Bernice A. Pescosolido, Jack K. Martin, Sigrun Olafsdottir, J. Scott Long, Karen Kafadar, and Tait R. Medina, “The Theory of Industrial Society and Cultural Schemata: Does the ‘Cultural Myth of Stigma’ Underlie the WHO Schizophrenia Paradox?,” American Journal of Sociology 121 no. 3 (2015): 783-825. ↵

Collean Barry, Victoria Bresscall, Kelly D. Brownell, and Mark Schlesinger, “Obesity Metaphors: How Beliefs about Obesity Affect Support for Public Policy,” The Milbank Quarterly 87 (2009): 7–47. ↵

Peter Conrad and Kristen K. Barker, “The Social Construction of Illness: Key Insights and Policy Implications,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(2010): s57-s79. ↵

Peter Attia, “Is the Obesity Crisis Hiding a Bigger Problem?,” TEDMED Talks April 2013 Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/peter_attia_what_if_we_re_wrong_about_diabetes. ↵

Anish P. Mahajan, Jennifer N. Sayles, Vishal A. Patel, Robert H. Remien, Daniel Ortiz, Greg Szekeres, and Thomas J. Coates, “Stigma in the HIV/AIDS Epidemic: A review of the Literature and Recommendations for the Way Forward,” AIDS 22 supp. 2 (2008): S67-S79. ↵

Elizabeth Pisani, “Sex, Drugs, & HIV: Let’s Get Rational,” TED Talks February 2010. http://www.ted.com/talks/elizabeth_pisani_sex_drugs_and_hiv_let_s_get_rational_1#t-1011824. ↵

United Nations, “Poverty and AIDS: What’s Really Driving the Epidemic?” http://www.unfpa.org/conversations/facts.html. ↵

Maria Makino, Koji Tsuboi, and Lorraine Dennerstein, “Prevalence of Eating Disorders: A Comparison of Western and Non-Western Countries,” Medscape General Medicine 6 no. 3 (2004):49. ↵

Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988). ↵

Anne E. Becker, “Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji: Negotiating Body Image and Identity during Rapid Social Change” Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 28 no. 4 (2004):533-559. ↵

Sing Lee, “Reconsidering the Status of Anorexia Nervosa as a Western Culture-Bound Syndrome,” Social Science & Medicine 42 no. 1 (1996): 21–34. ↵

L.A. Rebhun, “Swallowing Frogs: Anger and Illness in Northeast Brazil,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 8 no. 4 (1994):360-382. ↵

Ibid., 369-371 ↵

Robert Bud, “Antibiotics: From Germophobia to the Carefree Life and Back Again.” ↵

Nancy Scheper Hughes, Death Without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989). ↵

World Health Organization, “Antimicrobial Resistance,” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/. ↵

David Koplow, Smallpox: The Fight to Eradicate a Global Scourge (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ↵

Jeffery K. Taubenberger, David Baltimore, Peter C. Doherty, Howard Markel, David M. Morens, Robert G. Webster, and Ian A. Wilson, “Reconstruction of the 1918 Influenza Virus: Unexpected Rewards from the Past,” mBio 3 no. 5 (2012). ↵

Jeffrey Taubenberger and David Morens, “1918 influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics,” Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12 (2006). ↵

Suzanne Clancy, “Genetics of the Influenza Virus,” Nature Education, 1(2008): 83. ↵

For more about these and other examples, see Carol P. MacCormack, Ethnography of Fertility and Birth (New York: Academic Press, 1982). ↵

Laury Oaks, “The Social Politics of Health Risk Warning: Competing Claims about the Link between Abortion and Breast Cancer,” in Risk, Culture, and Health Inequality: Shifting Perceptions of Danger and Blame, eds. Barbara Herr Harthorn and Laury Oaks (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003). ↵

Marcia C. Inhorn, The New Arab Man: Emergent Masculinities, Technologies, and Islam in the Middle East (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012). ↵

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “The Multiple Dimensions of Food Security,” http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3458e/i3458e.pdf. ↵

World Health Organization, “Urbanization and Health,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(2010): 241-320. ↵