5.5 The Oedipus Trilogy

The Oedipus Trilogy

One of the major memorable stories from Greek mythology is that of Oedipus. The play Oedipus the King is just one of three plays by Sophocles; the other two, Oedipus at Colonus and Antigone, complete a trilogy’s worth of stories about Oedipus—although, to be fair, the plays themselves were not written as a trilogy. What follows here is a summary of the entire Oedipus cycle, but it doesn’t substitute for reading the myth; it’s one of the great works of ancient literature, and Sophocles’s ability to capture the emotion of the moment even when his whole audience knew the outcome (because the ancient Greeks all already knew the myth of Oedipus) is incredible.

The story starts in the Greek city of Thebes, where King Laios and his wife Queen Iocasta (sometimes called Jocasta) have a child. As was obligatory then, they sought the oracle for a good prediction for the child’s life. The oracle’s response, however, was anything but positive: the oracle declared that the child would grow up to kill his father, marry his mother, and have children with her. Aghast, Laios and Iocasta decide to kill the baby using a common method called exposure. Tying up the infant, they gave him to a servant to take outside of town to the top of a nearby mountain, to place the child at the summit and let nature do the rest to end the boy’s life.

The servant, about to leave the baby at the summit, lost his resolve, and ran into a shepherd on the far side of the mountain. The servant struck a deal with the shepherd, who took the baby and returned to his hometown of Corinth, far away from Thebes. They unbound the baby, but the damage had already been done—the child’s swollen foot made him walk with a limp for the rest of his life. They named him Oedipus, which means “swollen foot.”

In Corinth, the childless king and queen of Corinth adopted Oedipus as their own son, and he grew up in their house. He had no idea who he really was—he’d always assumed he was the biological child of the Corinthian king and queen. At a late-night drinking party one night, another partygoer made fun of Oedipus by accusing him of not knowing who his parents were. This insult stung Oedipus, enough that he set off to see the oracle to learn who he really was.

The oracle had no good news: it announced Oedipus was the one who would kill his father, marry his mother, and have children with her. Distraught, Oedipus went into self-imposed exile, promising never to return to Corinth so as to never kill his father and marry his mother. He sets of northward instead, toward Thebes. Along the way, in the no man’s land of Greece not ruled by any particular city, he encounters a man in a chariot with six servants, and Oedipus gets into an argument with the chariot rider. The argument turns violent, and Oedipus kills him and five of the six servants; the sixth escapes.

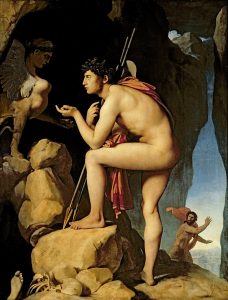

As Oedipus comes toward the gate of Thebes, he finds himself stopped by a mythic beast called a sphinx. The sphinx has decided to eat anyone who cannot answer her riddle and tries to pass through the gates into the city. Oedipus asks the riddle, and the sphinx replies, “What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, and three legs in the evening?” Oedipus says the answer is a man, who walks on four legs as an infant crawling, walks on two legs during the prime of life, and walks with the aid of cane in his twilight years. Oedipus guessed correctly, and the sphinx kills herself.

Upon entering the city, Oedipus is met with a major surprise: recently, the king Laios who ruled the city had been mysteriously murdered. The one servant who escaped the carnage said he had been attacked by multiple men. At the same time, the sphinx descended on the leaderless city, terrorizing it. The brother of Queen Iocasta, a man named Creon, had taken temporary control and tried to solve both the city’s problems with one solution. He decreed that whoever got rid of the sphinx would be married to Iocasta and become the next king and leader of Thebes. Oedipus, having no idea of all this, found himself greeted as king, married to Iocasta, and settled into the royal palace with Creon as an adviser. He and Iocasta, despite her being years older than him, go on to have four children, including the boys Eteocles and Polynices and the daughters Ismene and Antigone. The servant who had escaped from Laios’s killing, seeing Oedipus is now king, quietly found himself a new long-term job in the mountains outside the city.

Years pass, and Thebes prospers. But then, a plague appears. Since plagues are typically sent by the gods, Oedipus sends Creon to the oracle to determine why. The oracle sends Creon back with the explanation that the plague is caused by Laios’s killer having never been found and punished; Oedipus vows to blind and exile the guilty party, and since there is no clear evidence he calls for Teiresias, the famous Greek prophet, to come and shed light on the identity of the killer.

Teiresias enters the scene unwillingly. He refuses to answer Oedipus’s pestering questions until, finally, he states it: Oedipus is the killer. Laios was the chariot rider Oedipus had killed, and the sixth servant who escaped had lied to save his honor. Oedipus is dumbfounded, and the servant is brought in. It turns out that not only is this the servant who had recognized Oedipus as the killer but chose not to tell, it’s the same servant who had taken infant Oedipus to the mountain all those years ago. Despite Iocasta’s pleading for Oedipus to stop asking questions, Oedipus leans in for more. At that moment a messenger appears from Corinth, telling Oedipus that his parents the king and queen of Corinth were now dead and he was being recalled for the kingship. This messenger is none other than the shepherd who had taken the baby Oedipus in all those years ago, from the same servant also present. Oedipus puts the pieces together, even as Iocasta disappears—it turns out she hung herself with her dress in grief. Oedipus, true to his word to punish Laios’s killer: he blinds himself with the brooches that had held Iocasta’s dress in place and he goes into exile, led by his daughters Ismene and Antigone.

And this is the first play!

Years later, Oedipus is in the twilight of his life. He and his daughters have wandered into the tree grove at Colonus, near the city of Athens. Back in Thebes, Eteocles and Polynices have come of age to rule, but have a three-way dispute with Creon about which of the three men ought to be king. They consult the oracle, who declares that whoever has Oedipus in their custody will be king. They each start seeking Oedipus in a race to find him first. Eteocles is the first to find Oedipus, but Oedipus knows why he has come. Cursing his son and banishing him from his presence, Eteocles goes away empty-handed. Next comes Polynices, who receives the same treatment and also departs empty-handed. One brother, in conversation with Ismene and Antigone as he leaves, shared that he has a bad feeling about what will happen next. He extracts a vow from the sisters that they will be sure to bury him properly if he dies, and the sisters vow to do so. Making vows like this were considered unbreakable.

It then became the third contender’s turn. Creon, learning from his rivals’ mistakes, kidnaps Oedipus’s daughters Ismene and Antigone, and holds them hostage. Their ransom? Oedipus must go with Creon. Begrudgingly, Oedipus agrees and is about to leave Colonus with Creon when a deus ex machina appears—this is a character who drops into a story to resolve a conflict almost instantaneously. This particular deus ex machina is Theseus, slayer of the Minotaur and the current king of Athens. He commands Creon to release the daughters, and prevents the ransom from happening. He walks Oedipus into the distance, where Oedipus dies of old age and is buried in an unknown location. Now even his bones cannot be in the sons’ or Creon’s custody.

Eteocles, Polynices, and Creon all return to Athens; Ismene and Antigone return too, now that their father is dead. The three rivals for the throne strike a deal: each will rule for one year. When the first year is up, the son ruling Thebes will not give up the throne to his brother. They assemble their henchmen and have a fight outside the city gates, while Creon sits back to watch, and they kill each other in combat. Now Creon has the throne to himself, and Ismene and Antigone are members of his household. Creon’s wife, Eurydice, is queen, and his son, Haemon, is crown prince. To further cement his claim to the throne, Creon makes two decrees. First, he and Eurydice arrange for Haemon to be engaged to Antigone; cousins marrying was normal in ancient Greece. Second, Creon decrees that no one is allowed to bury Eteocles’s and Polynices’s corpses. This bears a bit of explaining.

In ancient Greece, it was widely believed that at death the soul entered Hades, the underworld. Since Hades was an actual place below the ground, their soul journeyed there across the river Styx, which had exactly one ferryman to bear souls across, called Charon. Charon always demanded a fee for his crossing: two gold coins. The burial custom, then, was to place these two gold coins on the eyes of the deceased, whose soul would use them to pay Charon. Not burying the body, or placing the coins, meant the worst possible outcome for a dead soul—the spirit would be stuck on earth as a ghost, wandering forever, never able to find his home in the underworld.

Creon decreed that no one was allowed to bury Eteocles and Polynices because he wanted to make a point: there had been enough violence, and it was going to stop. Anyone who didn’t stop the violence would end up just like the two very visible examples of the princes at the city gate. But his decision also caused a moral calamity for Ismene and Antigone, who were obligated by their vows to bury their brothers and ensure them safe passage to the underworld. On top of this, Creon vows a terrible punishment: whoever dares defy his orders will be buried alive in the royal family mausoleum. Ismene, faced with her death if she kept her vow, breaks her vow and exits the story in dishonor. Only Antigone remains of Oedipus’s children. Night falls.

In the morning, an alarm sounds—someone sprinkled enough dust over the bodies of both brothers to count as a burial, with coins on their eyes to boot. Creon is furious, and it takes only a short investigation to confirm that it was Antigone who buried her brothers. Against his wife Eurydice’s and son’s Haemon’s protests, Creon seals Antigone in the mausoleum.

Not long after, Eurydice as well as Creon’s own misgivings finally catch up to him. He goes to the mausoleum to release and forgive Antigone, only to find a horrid sight: the mausoleum was open. Peering inside, he saw the body of Antigone hanging—she had opted not to wait for starvation or lack of air to end her life. At his feet lay the body of Haemon his son, who had broken into the mausoleum to save his fiancée but arrived too late, and had killed himself in grief. Word spread while Creon stood there taking it all in, and a messenger arrives to tell Creon that his wife Eurydice, in grief over her son’s death, had also killed herself. The saga ends with Creon discussing the meaningless of life.

This summary has been adapted from Avery, Catherine B., editor. The New Century Classical Handbook. New York: Appleton-Century Crofts, 1962.